ISSN 1847-2397 godište II broj 1 2009. | volume II number 1 2009

ISSN 1847-2397 godište II broj 1 2009. | volume II number 1 2009

ISSN 1847-2397 godište II broj 1 2009. | volume II number 1 2009

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

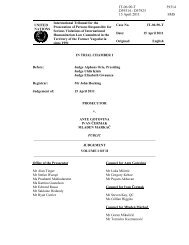

Plamena Pehlivanova: The Decline of Trust in Post-Communist Societiessuvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1distrust of these societies. Nevertheless, we observemore ingroup trust, more bonding ratherthan bridging and more time spent with familyand close friends rather than at any civic associations.In The New Political Culture, a followingmodel is proposed (Clark, Hoffmann-Martinot,1998: 27):Having a slimmer family and more educationcontributes towards the increase in individualand group tolerance. These factors alsofacilitate the rise of the New Political Culture.However, having a slimmer family and the possessionof individualistic values is not embeddedin the Bulgarian and Russian history. Instead thecultural forms of the two countries have developedaround the nuclear and extended familystructures, which Maria Todorova has studied asfar as during the Ottoman rule of Bulgaria. The“cult of the family” can be explained through theevolution of the family model in the Balkan history.In her Balkan Family Structure and the EuropeanPattern: Demographic Developments inOttoman Bulgaria, Maria Todorova emphasizesthe Balkan tendency to predominate in nuclearSlimmer Family: decline in extendedfamily; weakening of family linksMore tolerance of individual andgroup toleranceMore Education: more media accessfamily households since 1863 (Todorova, 2006:25). Changes within the family structure have occurreddue to variety of factors – social structureand social values, economy and environmentalconstraints. Nuclear family dominated during theOttoman rule and the extended family expandedduring the Soviet period. Following the Sovietera, observations show an increase of extendedhouseholds during the 1990s. Second, it appearslikely that some reversal occurred over the firstquarter of the 20th century due to the substantialincrease in the share of solitaries. For the longSoviet period, however, the relative order of thecategories remains roughly the same. The largestgroup is simple family households, accountingfor 41% and 55%. The second and thirdlargest categories are solitaries and extended/multiple households with 18–22 and 15–24%.Finally, there is a more or less stable 10–15%one-parent households. During pre-soviet andSoviet period, it was the norm for newly marriedcouples to co-reside with the parents of oneof the two spouses. “For the years up to 1970they yield an expected bandwidth variation of extendedhouseholds of between 30 and 45%, i.e.well above the actual percentage of extensionfound in the population census data for theseyears.” (Afontsev et al., 2008: 177). Accordingto the logic of the model, Afontsev argues thatthis would mean that not even all ‘available’ widowsjoined their married children’s household atold age, and she strongly suggest that nuclearfamily formation was the norm. Starting from the1970s, however, the calculations yield an expectedshare of extended households of around20%, which approaches the ‘real’ values enoughto hint at the possible existence of an extendedfamily system during the later Soviet period.Similar to the Bulgarian model, the Russianfamily structure also portrays a traditionalpattern of nuclear and extended family structures.In looking at the history of the family structure,we must also take under consideration thestructure and availability of housing as a factorthat influences patterns of household formation.As Sergey Afontsev et al. mention in their studyurban housing in Russia was in very short supplythroughout most of the 20th century, with theexception of the years of actual de-urbanizationduring the Civil War. (Afontsev et al., 2008: 190).In the table above, it is seen that the share ofsolitaries among urban households was lowestduring the 1930s to 1950s, when housing wasmost scarce due to the combination of high ratesof rural–urban migration and low investment incivil construction. The shortage of housing thusobviously became an important factor behind theformation of extended and multiple households,and influenced the cultural preferences that favoredsuch households. Newly married couplesoften could not obtain separate apartments untiltheir 30s and so, like the Bulgarian families,centar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr43