ISSN 1847-2397 godište II broj 1 2009. | volume II number 1 2009

ISSN 1847-2397 godište II broj 1 2009. | volume II number 1 2009

ISSN 1847-2397 godište II broj 1 2009. | volume II number 1 2009

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Uvodna riječsuvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1Uvodna riječČasopis Suvremene teme / ContemporaryIssues ušao je, unatoč utjecaju globalnegospodarske krize na financiranje znanstvenogizdavaštva, u svoju drugu godinu te na taj načinuspio zadržati predviđeni tempo i kontinuitetizlaženja. Nastavno na iskustvo prethodnog <strong>broj</strong>a,uredništvo je za drugi <strong>broj</strong> odabralo radovekoji odražavaju multidisciplinarnu i međunarodnunarav časopisa Suvremene teme / ContemporaryIssues.U prvom dijelu ovoga <strong>broj</strong>a predstavljamovam studiju o televizijskome oglašavanju uPakistanu s naglaskom na ženskoj perspektivi,analizu diskursa o reformi medicinskog sustavau Québecu, kao i raspravu o krizi društvenogpovjerenja u postkomunističkim zemljama naprimjerima Rusije i Bugarske.Drugi dio ovoga <strong>broj</strong>a posvećen je temiu fokusu – Bosni i Hercegovini. Bosna i Hercegovinanalazi se u kritičnoj fazi reforme i konsolidacijedržavnosti, borbe s ratnim naslijeđemte napora oko približavanja Europskoj uniji. Iztog smo razloga odlučili u ovome <strong>broj</strong>u dati višeprostora radovima koji se bave pitanjima ovedržave. Dva rada su djelo autorica iz Bosne iHercegovine, dok jedan članak potpisuje autoriz Hrvatske. Uz to, donosimo i izlaganje smeđunarodnog skupa posvećenog budućnostiBosne i Hercegovine, održanog u Budimpešti, ustudenom <strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong> godine.Naposljetku, ističemo kako Suvremeneteme / Contemporary Issues, premda novičasopis, imaju za cilj postati hrvatski časopisza društvene i humanističke znanosti prepoznatu međunarodnoj akademskoj zajednici. Stogasmo u procesu, odnosno u pripremi, apliciranjaza uvrštenje u relevantne svjetske citatne baze.Uredništvocentar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr4

Jamshed Khattak, Aslam Khan: Understanding Female College Studentssuvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1UDK: 316.66-055.2(549.1)Izvorni znanstveni članakPrimljeno: 1. 6. <strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>Understanding Female College Students’ Mind-set towardsTelevision Advertising in PakistanJAMSHED KHATTAKCollege of Commerce, Islamabad, PakistanASLAM KHANHITEK University, PakistanPurpose: This study examined the consequences and impact thattelevision advertising has upon the general attitude of female college studentstowards television advertising in Pakistan. The data was collected from randomlyselected 299 female college students. Methods: The respondents fromfive metropolitan cities like Peshawar, Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Quetta and Karachiwere asked to answer a self-administered questionnaire. Descriptive,t-statistics, correlation and regression statistical tools were used to analysedata. Results: The results of the study reveal that these students have negativejudgment about the ethical and social consequences of television advertising.However they have positive judgment about the economic impact of televisionadvertising. The students demand more regulation to control the televisionadvertising. The results indicated that there is a significant positive generalattitude of female college students towards the television advertising in Pakistan.The study predicted a positive relationship between the consequences/impact and general attitude of female college students towards the televisionadvertising. Recommendation: The study recommends that marketers andthe regulatory bodies have the responsibility to pay proper attention to therising ethical, social and regulatory concerns of the female college students’about the television advertising. Moreover the study provides a useful benchmarkfor future research studies.Key words: attitudes, television advertising, female students, Pakistan1. IntroductionIt is a fact that television is the major andleading communicator of our era. Television isthe most reachable media in Pakistan. Televisioncoverage in Pakistan is about 87-90 percent(Parveen, <strong>2009</strong>). Advertising is the major earningsource of television and a powerful tool topenetrate into different segments of the society.Regardless of the fact that advertising is a successfultool for business, along with being a vitalelement of the modern age and a fast growingindustry, the public fondness of advertising is stilla matter of great concern (O’Donohoe, 1995). Ithas a great power to influence the consumers’vision about values, ethics and norms. Advertisingis also criticized for presenting misleadinginformation, promoting adverse values, fake claims,depiction of females as “erotic objects” andpersuading people to buy things they no longercentar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr6

Jamshed Khattak, Aslam Khan: Understanding Female College Studentssuvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 17.2. Research ModelIt is apt at this stage to develop a model of the study which is discussed hereunder:Consequences andimpact of televisionadvertisingEthicalEconomicSocialFemale students’general attitudetowards televisionadvertisingRegulatoryThe judgment of students about the consequences and impacts of the television advertising(ethical, economic, social and regulatory) are taken as the independent variables, while the general attitudeof female students towards the television advertising is taken as the dependent variable.8. Research Methodology8.1. SampleThe targeted population was limited tofemale college students, with the aim of understandingthe mind-set of female college studentstowards television advertising. A national investigationwas performed in colleges of the six metropolitans(Karachi, Lahore, Quetta, Peshawar,Rawalpindi and Islamabad). A total of 400 questionnaireswere distributed, out of which 299questionnaires were retrieved. The responserate was 75%.(a) Ethical consequences (deception,puffery, sexual appeals)(b) Social consequences (needlessproducts, clutter, materialisms,undesirable values)(c) Advertising regulations (harmfulproducts, exiting regulations,proliferation)8.2. Measurement of the VariablesBauer and Greyser (1968) adaptedLarkin’s (1977) items to study attitudes towardadvertising. Consequently, several other studies(Anderson et al., 1978; Andrews, 1989; Greyserand Reece, 1971; Haller, 1974; Schutz andCasey, 1981; Triff et al., 1987) used the samescale. The study has considered measures tojudge the following three attitudinal areas usingLarkin’s scale:The General Attitude scale (good,helpful, believable) is selected from Pollay andMittal (1993) to measure the general attitude offemale college students towards television advertising.To measure the response, the five pointLikert Scale from strongly disagree to stronglyagree was devised. The demographic informationlike gender, age and class of the respondentswere also sought through the questionnaire.centar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr10

Jamshed Khattak, Aslam Khan: Understanding Female College Studentssuvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 18.6.1. The Ethical ConsequenceThe results in Table 4 show that the respondentsagreed that most of television advertisingis false/misleading, exaggerated informationand contains sexual appeals. In the realmof ethical consequences the result indicates thatfemale college students have a negative attitudetowards moral consequences of television advertising.8.6.2. The Economic ImpactIn the domain of the economic impactthe figures in Table 4 disclose that female studentsconsider television advertising to be servingto the development of the national economy,raising the standard of living of the community,assuring quality goods and encouraging competition,leading to price cut-backs of merchandiseand services. The result indicates a positiveattitude of students with regard to the economicimpact8.6.3. The Social ConsequenceFemale college students admitted thattelevision advertising is convincing people to buyproducts which they do not really need, thereforeconfusing them and also promoting materialism.The result in Table 4 confirms that female collegestudents acknowledge television advertisingto be a source of promoting obscene valuesamong the youth. The results imply that the attitudeof female college students towards televisionadvertising social consequence is negativeand consider having adverse effects on society.8.6.4. Feelings about Advertising RegulationsThe mean score of the respondents inTable 4 recommends blocking television advertisingof products which have a damaging impacton society. The students have demanded moreregulation for control and proliferation of televisionadvertising. The overall outcome proposesthat female students are not happy with the abilityof existing regulations to control and checktelevision advertising effectively.8.6.5. The General Attitude towards TelevisionAdvertisingWith regard to the general attitude, resultsin Table 4 advocate that respondents areconvinced that television advertising is good andhelpful. However, they oppose on the point thattelevision advertising is believable. The resultsput forward that female college students’ generalattitude is positive towards television advertisingin general.8.7. Correlation Analysis of VariablesTable 5Correlation matrix of variablesGeneralEthical Economic Social RegulatoryattitudeGeneral1attitudeEthical .184 ** 1Economic1.342impact** .050Social .106 * .356 ** .045 1Regulatory .133 * .367 ** .141 * . .386 ** 1** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (1-tailed)* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (1-tailed)centar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr13

Jamshed Khattak, Aslam Khan: Understanding Female College Studentssuvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1The results of the correlation coefficientsin Table 5 show a significant correlation amongall the independent variables and the general attitudeof female college students towards televisionadvertising.The results in Table 5 indicate that thereexists a positive correlation between the ethicalconsequences and the general attitude of femalecollege students towards television advertising.The results also reveal that the more ethicaltelevision advertising is, the more positive isthe attitude of female college students towardsadvertising. Hence it supports the H 6.The correlation coefficient between theeconomic impact of television advertising andthe general attitude of students towards televisionadvertising, as indicated in Table 5, is fairlysignificant. The study draws the inference thatthe more positive the economic impact of televisionadvertising is, the more positive is the attitudeof female students towards advertising. Weagree to H 7.The significant correlation coefficientin Table 5 between the social consequences oftelevision advertising and the general attitude offemale college students towards it conclude thatthe more socially responsible television advertisingis, the more positive is the general attitudeof female college students. The hypothesis H 8isestablished.The result in Table 5 demonstrates asignificant correlation between the mind-setabout television advertising regulations and thegeneral attitude of female college students towardstelevision advertising. We can infer thatthe more government regulations are set to controlthe television advertising, the more positivethe general attitude of the female college studentsis towards advertising. Hence the studyacknowledges H 9.8.8. Regression AnalysisTable 6Model summaryModelStd. error of theR R square Adjusted R squareestimate1 .383 a .146 .135 .57316a. Predictors: (constant), regulatory, economic, ethical, socialTable 7 ANOVAModelSum ofsquaresdf Mean square F Sig.1 Regression 16.577 4 4.144 12.615 .000 aResidual 96.583 294 .329Total 113.159 298a. Predictors: (constant), regulatory, economic, ethical, socialb. Dependent variable: general attitudeThe results in Table 6 and Table 7 indicate that the independent variables significantly explainthe variation in the general attitude of female college students towards television advertising.The results in Table 8 show that the ethical consequences and the economic impact significantlypredict the general attitude of female college students towards television advertising. However the socialconsequences and feelings about the advertising regulation do not significantly predict the generalattitude of female college students towards television advertising.centar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr14

Jamshed Khattak, Aslam Khan: Understanding Female College Studentssuvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1Simpson, P. M., Brown, G., Wilding <strong>II</strong>, R.E. (1998): The Association of Ethical Judgment of Advertisingand Selected Advertising Effectiveness Response Variables, Journal of Business Ethics, 17(2):125-136Singh, R., Sandeep, V. (2007): Socio-Economic and Ethical Implications of Advertising - A PerceptualStudy, International Marketing Conference on Marketing & Society, 8-10, <strong>II</strong>MKTactics’, Advances in Consumer Research, 13: 1-3Wills, J. R., Ryans, J. K. (1982): Attitudes toward Advertising: A Multinational Study, Journal ofInternational Business Studies, 13 (3): 121-129Wolburg, J. M., Pokrywczynski, J. (2001): A Psychographic Analysis of Generation Y Female Collegestudents, Journal of Advertising Research, 41(5) 33-50Wright, P. L. (1986): Schemer Schema: Consumers’ Intuitive Theories about Marketers’ Influence, inLutz, R. (eds): Advances in Consumer Research, Association of Consumer Research, Provo, UT,13:1-3Zhang, P. (2000): The Effect of Animation on Information Seeking Performance on the World: SecuringAttention or Interfering with Primary Tasks?, Journal of the Association for Information Systems(JAIS), 1 (1): 1Razumijevanje stavova studentica prema televizijskom oglašavanjuu PakistanuJAMSHED KHATTAKEkonomski fakultet, Islamabad, PakistanASLAM KHANSveučilište HITEK, PakistanSvrha: Istraživanje se bavi posljedicama i utjecaju koje televizijskooglašavanje ima na opće stavove studentica prema televizijskom oglašavanjuu Pakistanu. Podatci su prikupljeni na temelju slučajnog uzorka od 299 studentica.Metode: Respondentice iz pet glavnih gradova poput Peshawara,Islamabada, Rawalpindi, Quetta and Karachia su odgovorile na upitnik. Zaanalizu podataka korišteni su statistički postupci, poput deskriptivne statistike,T-statistike, korelacija i regresije. Rezultati: Rezultati istraživanja pokazuju dastudentice imaju negativne stavove o etičkim i socijalnim posljedicama televizijskogoglašavanja. S druge strane, imaju pozitivne stavove o ekonomskimučincima televizijskog oglašavanja. Studentice zahtjevaju više zakonske regulativekoja bi kontrolirala televizijsko oglašavanje. Rezultati upućuju na to dapostoji značajan pozitivan opći stav prema televizijskom oglašavanju u Pakistanu.Studija je predvidjela pozitivnu korelaciju između posljedica/ učinakai općeg stava studentica prema televizijskom oglašavanju. Preporuke: Preporukestudije za oglašivače i zakonodavce odnose se na preuzimanje većeodgovornosti u rastućim etičkim, socijalnim i regulatornim pitanjima s kojimase susreću studentice u pogledu televizijskog oglašavanja. Osim toga, studijamože biti korisno polazište za buduća istraživanja i komparacije.Ključne riječi: stavovi, televizijsko oglašavanje, studentice, Pakistancentar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr17

Sabina Stan: The Discourse on the “Crisis of the Health Care System”suvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1UDK: 349:614.2>(71)=111Izvorni znanstveni članakPrimljeno: 14. 5. <strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>The Discourse on the “Crisis of the Health Care System” andthe New Governance Model of Health Care in QuebecSABINA STANDublin City University, IrelandDuring the last decade, public discourse on the “crisis of the healthcare system” in Quebec and Canada soared to the extent that the crisis hascome to be seen by many Quebeckers and Canadians as an enduring featureof their health care sector. Based on analysis of articles from the Quebec writtenmedia, the article shows that the crisis discourse contributes to promote amarket-like governance model of the health care sector and to foster the acceptanceof market-oriented health care policies.Key words: health care, governance, discourse, crisis, neoliberalism1. IntroductionSocial scientists have recently devotedattention to the popular reception of “healthnews stories” (Adelman and Verbrugge, 2000;Brodie et al. 2003; Seale, 2004; King and Watson,2005). But while health policy scored secondamong the health news stories which mostcaptured the interest of the American public, theimportance of media in shaping “public viewsabout the health care system” has only started tobe envisioned (Davin, 2005; Henderson, 2010).This article takes as a case of study the discourseon the “crisis of the health care system” developedin the Quebec francophone print media inthe last two decades and tries to unveil the mannerin which it might have contributed to healthpolicy in Quebec and Canada.The article starts from the premise thatmedia discourse on the “crisis of the health caresystem” offers a privileged perspective for dealingwith matters at the intersection of media discourse,health policy, organisational ensemblesand social problems. Indeed, as this article willshow, the period during which the crisis discoursedeveloped was both preceded and followedby some of the most important reformsthat affected the Quebec health care sectorsince its constitution at the beginning of the 70s.The first was the Rochon reform of 1996-1997,which tried to answer to increased strain on publicfunds with the “ambulatory turn” and the correspondingreduction of total hospital capacity(Bernier and Dallaire, 2001). The second reformstarted in 2003, after the discourse had reachedits peak, and stressed the need to change thehealth care sector along management and marketlines. This article aims to show that, while thecrisis discourse was triggered by reactions to thefirst reform, it also contributed to the lean acceptanceof the marketising stance present in thesecond reform. This article will analyse, in thefirst part, the media discourse on the “crisis ofthe health care system”, and will address, in itssecond part, issues pertaining to its productionand to its ideological effects.centar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr18

Sabina Stan: The Discourse on the “Crisis of the Health Care System”suvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 12. Discourse, Social Problems and PolicyA <strong>number</strong> of social scientists have rejecteda conception of social problems as simply“objective and identifiable societal conditions”.Social problems were seen as “products of aprocess of collective definition” (Hilgartner andBosk, 1988; Spector and Kitsuse, 2006), withdiscourse playing a major role in their construction(Herdman, 2002: 162). Following these approaches,this article sees “the crisis” and “thehealth care system” not as objects existing outthere in a separate material world, but as objectsof political and managerial intervention that areconstructed through discursive practices. 1I envision discourse as a class of relatedtexts that exists “beyond the parts which composeit”, the unity of which is given by their commonproduction in a particular social field (Chalaby,1996: 689, 690). The meaning of a particular discourseis given not only by its component texts,but also by its relationship with other discourses,as well as by the social conditions and structuralcontext of its production (Chalaby, 1996; Fissand Hirsch, 2005). Moreover, as discourse hasa processual (Purvis and Hunt, 1993: 496) andperformative (Kuipers, 1989: 103) character, itsmeaning is also informed by the manner in whichit unfolds in time, by its temporal dynamics.Discourses furnish frameworks for envisioning,and, in fact, systematically shaping not only theproblems that span a certain domain of activity,but also the causes of these problems, their possiblesolutions, and, finally, the object of politicaland managerial intervention (Foucault, 1971:71). From the standpoint of public policies andorganisations, discourses supply the parametersthat fashion the architecture of policy objects, aswell as the frames for thinking of the possibility ofpublic intervention (Bridgman and Barry, 2002).Discourses also take part in the symbolicstruggle for the production of the commonsense and for the “monopoly over legitimate processesof naming” (Bourdieu, 2001: 307). It isthus important to dwell on their dynamics andon the manners in which they are articulated ashegemonic at different moments (Torfing, 1999:101). One of the most current techniques in thisrespect is to render their propositions naturaland taken-for-granted (Purvis and Hunt, 1993:1 A focus on discourse does not mean denying theexistence of real problems in the health care system, but itdoes imply approaching these problems from a perspectivethat takes into account the constructed, situated and conjecturalnature of these problems.478, Bourdieu, 2001: 209). 2In modern societies, state bureaucraciesand their representatives were traditionallyconsidered to be the most important producersof social problems and discourses (Bourdieu,1994: 2). But in contemporary Western societies,states no longer retain the monopoly to influencepublic opinion, policies or discourse. In oursocieties, media acquired a leading role in theproduction of discourses and of social problemssuch as “crises” (Hilgartner and Bosk, 1988).3.MethodologyThe field of discursive production Ihave chosen is the written francophone press inQuebec. The study used as a selection tool thedatabase Biblio Branchée of the media serverEureka.cc. 3 The database includes only threeof the five main francophone dailies in Quebecprovince, namely La Presse, Le Devoir and LeSoleil, leaving outside the two main tabloidsJournal de Montréal and Journal de Québec. Itis due to these limitations in the selection of thejournals that the present study does not claim tobe representative of all print media. Instead, itaims to highlight some, albeit significant, discursivedevelopments taking place in at least part ofthe Quebec written media field. Further researchon the two tabloids would need to be carried outin order to attain representativeness as well asto investigate further the hypothesis advanced inthis article.The limitations present in terms of representativenessare balanced out by some positivegains in terms of significance. Thus, whilethe three chosen dailies are surpassed in termsof circulation by the two tabloids, they constitutenevertheless important authoritative voices indomains of national importance such as health2 By seeing discourse as actual "networks of communication"(Purvis and Hunt, 1993: 485), I dwell on its characteras lived, concrete practice. But I still seek to unveil its"ideological effects" (Purvis and Hunt, 1993: 485) by tacklingthe issue of domination and hegemony. Thus, my approachto discourse departs from Foucaultian ones and nears neo-Gramscian perspectives such as the one advanced by Laclauand Mouffe (see Torfing, 1999). Recognising that discoursesdo not strictly correspond to class divisions, thatthey have diffuse frontiers and that they are indeterminateand produced by a multiplicity of centres, does not preventus from recognising that, in historically situated moments oftime, certain actors and institutions have a hold on the articulationof particular dispersed discourses into a hegemonicone, and, consequently, in negating and repressing alternativemeanings (Bourdieu, 2001, Chalaby, 1996, Torfing,1999).3 See their website at Eureka.cc for more information.centar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr19

Sabina Stan: The Discourse on the “Crisis of the Health Care System”suvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1care. 4 The chosen dailies also reflect variousdivisions inside the Quebec written media field.Thus, while La Presse and Le Devoir are bothpublished in Montreal, Le Soleil is published inQuebec City. And while La Presse and Le Soleilbelong to media empires Power Corporationand Hollinger, and promote more right wing positions,Le Devoir is an independent daily eversince its foundation and is known for left-leaningaffinities.Articles were selected using the “LEAD= crise ET système ET santé “ search of the database.This option searches for articles wherethe first two paragraphs simultaneously containthe words crise, système and santé (crisis, systemand health, respectively). The search givesa good approximation of the evolution of articlesthat include references to the crisis of the healthcare system, while also restricting itself to thosemedia utterances that are most likely to have animpact on readers. The selection was further refinedby dropping articles that were not referringto the crisis of the health care system. 5 The principalbody of data is comprised of 139 articlescovering the period 1988-2003. The analysiswas based on three careful successive readingsof the articles conducted by myself that paid attentionto the articulation of the meanings of “thecrisis”, its causes, its object (“the system”) andits solutions.In addition to this search, I performedseveral other searches that sought to place the“crisis of the health care system” in a wider discursivefield, by looking at discussion on the crisisof other possible related objects or on chaoticevents that affected the system. I thus selectedthe articles that, during the same period, madereferences to the crisis of the health care sector(“crise du secteur de la santé”), the crisis ofhealth care (“crise des soins de santé”), the crisisof health care services (“crise des servicesde santé”), the crisis of the health care network(“crise du réseau de santé”), the emergencyroom crisis (“crise des urgencies”) or “hospital4 As in other countries, in Quebec also the threedailies are seen as being more “intellectual” than the more“popular” tabloids.5 A total of 64 articles were dropped from the initialbody of 203 articles. While Le Soleil sometimes duplicatesarticles from La Presse, the <strong>number</strong> of duplicates in my corpusof data was limited to 5 articles. I chose to keep Le Soleilduplicates in my corpus because, considering the definitionof discourse I am using in this article, they constitute equallyworthy texts that contribute to the constitution of discourse.Whereas from a quantitative point of view they are the samewith the original, and should be dropped, from the qualitativeperspective adopted here, they are different texts and shouldbe counted as separate.closing” (“fermeture d’hôpitaux”). Analysis of theresulting data sought to uncover the <strong>number</strong> ofarticles, per year, that mentioned the respectivephrases.As Graphic 1 shows, the yearly <strong>number</strong>sof articles referring to the crisis of the health caresystem are relatively low up until 1997 (they varybetween zero and five). The incidence increasessignificantly beginning in 1998 (14 articles),reaches a peak in 2000 (39 articles), after whichit decreases while still remaining at significantlevels (12 in 2001; 24 in 2002; and 16 in 2003).The passage from scattered statements to a fullblowncollection of utterances, i.e. a discourse,occurs then only after 1998. 1998 is thus thedate of birth of the crisis discourse.This development is apparent not only inthe swift numerical intensification of utterances,but also in the qualitative change in their textualcontexts. These textual contexts can be dividedbetween, on the one hand, short news texts (actualités),and, on the other hand, editorials andlonger articles that discuss and analyse in lengththe fate of the health care system. For the entireten-year period 1988-1997, our body of data includedonly 14 texts of the second type. By comparison,during the six-year period 1998-2003,the <strong>number</strong> of more consistent texts dedicated tothe health care system multiplies by more thanseven, to reach 102.In the process, a new vision of the problemsaffecting the health care system (“the crisis”)imposes itself in the francophone media.Before 1998, the crisis was seen mainly as apartial and temporary phenomenon. As much ashalf of the articles from the period 1988-1997 referto crises IN the health care system (9 out of18). There are emergency rooms crises (whenpatients overflow emergency rooms’ capacity),personnel crises (when lack of sufficient <strong>number</strong>sof physicians and nurses is considered dramatic)and labour relations crisis (when physiciansor other health care personnel engage instrikes). As they occur in certain precise points ofthe health care system (a hospital, an emergencyroom, a regional health board), these criseshave rather precise organisational boundaries.Moreover, as such, they are viewed as circumscribedand partial.On the other hand, the other half of thearticles from the period 1988-1997 that refer toa crisis OF the health care system construct iteither as a future event or as a temporary situation.At the very beginning of the period, in 1988,several articles refer to the crisis of the healthcare system as a possible future event.centar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr20

Sabina Stan: The Discourse on the “Crisis of the Health Care System”suvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1constitutes itself into “a window to the fragility ofour system”. 11Thus, after 1998, the crisis is conceivedof as a quasi-permanent feature of the system. Ifin the spring 1998, there is a “very profound crisisthat touches the health care system”, 12 at thebeginning of 1999, there is a “perpetual state ofcrisis” 13 that in several months transforms itselfinto “the most profound crisis of the last ten years[assaulting] our health care system”. 14 At the beginningof 2000, the problems of the health caresystem are no longer “conjectural”, 15 and later itis restated that the health care system is in “apermanent state of crisis”. 16 One year later, oneis summoned to take notice of the crisis’ gravityand of “how profound a crisis our health caresystem goes through”. 17Thus, after 1998, a new vision of thecrisis develops, takes hold of media discourseand becomes the dominant way to qualify thesystem as a whole in this field. Indeed, now, discussionon the crisis is conducted in a matterof-factmanner that renders its existence evidentand natural. In the new vision, the crisis of thehealth care system is just there. It is a takenfor-granted,normal phenomenon, the existenceof which does no longer need to be proven, butonly, at most, illustrated. This generalisation andnaturalisation of the idea that the health caresystem is in crisis can be seen as indicative ofits institutionalisation and of its transformationinto a dominant vision of the present state of thehealth care system. 18This vision of the crisis supplies theframework for conceiving of the problems of thehealth care system (“the crisis”) as permanent,general and profound ones. But the crisis discourseoffers not only a framework for envision-11 Le Devoir, April 1, 2000: F412 Le Devoir, April 20, 1998: A113 La Presse, February 24, 1999: B314 Le Devoir, July 13, 1999: A615 Le Devoir, February 5, 2000: A1216 La Presse, March 24, 2000: B3; La Presse, June21, 2002: A1017 La Presse, May 23, 2001: A1618 The dominance of a new vision of the crisis isalso compounded, paradoxically, by the fact that voices thatcontest the existence of the crisis also intensify during theperiod 1998-2003. Marginal as they are (of the total articlesanalysed here, only nine include a negation of the crisis),these voices almost double their strength after 1998. Denialsof the existence of the crisis can be seen not so much as participatingin a powerful counter discourse, but more as merereactions to a powerful vision that imposes itself as the prismthrough which the health care system is read.ing the problems of the health care system; italso comprises visions of the causes of theseproblems.5. Articulations: The Causes of the CrisisIn order to grasp the manner in whichthe crisis discourse envisions the causes of thecrisis, I will make a couple of distinctions. On theone hand, I distinguish between causes externaland internal to the system, that is, betweencauses that lie in the system’s environment andcauses that lie in the functioning of the system.On the other hand, I also distinguish betweencauses that are seen in terms of agency (i.e.originating in the action of real, identifiable actors,such as, in this case, the government,pharmaceutical companies or physicians), andcauses that are seen in terms of abstract processesor entities (such as demographic andeconomic trends or “the structure”). Within thecrisis discourse, few voices seriously considerthe contribution of external factors to the developmentof the crisis. Among external factors,what we could call “external agents” is very marginal.In fact, only two articles explicitly see thecrisis as resulting from the actions of real, concreteagents – namely, the Quebec government,and physicians and pharmaceutical companies,respectively. 19 Among external causes, the pivotalplace is accorded not to identifiable agents,but rather to trends which are seen as inherentin the evolution of our contemporary societies.These are global trends that drive up health caredemand and thus health care costs: the ageingof the population, technological developments inmedicine, the invention of new drugs and newcontagious diseases like SARS (in 2003). It isdue to their sheer amplitude that these trendsimprint themselves on the health care system soas to render it “an abyss without bottom”. 20In this way, the crisis discourse takesa natural and abstract turn, as real agents thatcould be made accountable are discharged in favourof abstract forces for which nobody can beblamed. Thus, the crisis itself is rendered natural,ineluctable, caught in the current, given, orderof the world. As one article states, “the pressuresthat threaten us in the future [ensure that]we are heading for a crisis”. 21As external abstract causes are natu-19 Le Devoir, July 13, 1999: A6, Le Devoir, April 12,2003: B720 La Presse, May 23, 2001: A1621 La Presse, June 5, 2000: B2centar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr22

Sabina Stan: The Discourse on the “Crisis of the Health Care System”suvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1ralised as given, they become a context formore fundamental causes that are related to thespecificity of the health care system in Quebecand Canada. After 1998, it is causes internal tothe system that are seen as the true roots of thecrisis. The debate is thus shifted from externalpressures on the system (diminishing resources,increased demand-induced costs) to the internalfunctioning of the system. As stated in one article,the cause of the crisis rests in “the allocationand the use of resources inside the network. Insum, what causes the problem is less the sumof money than the manner in which the latter isspent”. 22 Vital causes are thus seen to be not“conjectural financial problems”, but “seriousstructural problems” of the system. 23The crisis discourse constructs theseinternal causes by referring once more to abstractnotions, such as “structure”, “organisation”,“management” (gestion), “(governmental)bureaucracy”, “political interference”, or “technocraticapproach”. All of these notions are seen aslaying at the origin of the vicious functioning ofthe system, transforming it into “a vast impersonalstructure” and a “bureaucratic monster”. 24 The“archaic”, “anachronistic”, “lazy and rusted” systemis characterised by the “fundamental vices”which are a “rigid network” and a “blind, insulated”and “superfluous” central bureaucracy. 25 It isa “big steamship difficult to manage”, plagued by“waste, bad choices and, especially, paralysis”. 26In sum, the system has become inefficient, as ischaracterised by “a heavy bureaucracy, a muchcentralised decision mechanism and rigid collectiveconventions”. 27By using an abstract language that doesnot lend itself easily to decoding by outsiders,this vision puts forth causes that cannot be easilyattributable to the concrete action of specific actors.Who, exactly, has a “technocratic approach”,what is “the structure”, and who is and who is notof the “bureaucracy”? A more attentive analysisunearths nevertheless some distinctions. Thereis, thus, on the one hand, the “structure(s)” of thesystem, a rather vague notion that seems to goalong with “bureaucracy” and “organization”, andthat seems to include the administration of hos-22 La Presse, February 24, 1999: B323 La Presse, March 24, 2000: B324 La Presse, June 3, 2000: B2; Le Devoir, 25 June1999: A9.25 La Presse, February 13, 1999: B2; La Presse,March 24, 2000: B3; La Presse, June 7, 2000: B226 La Presse, June 9, 2000: B227 Le Devoir, May 3, 2000: A7pitals, community centres (CLSCs), the Regionaldistrict boards (RRSSS) and the ministry. 28 Onthe other hand, there is “health care” (“les soinsde santé”), a notion that covers rather unambiguously“services offered in the private offices ofphysicians”. 29 Like two opposing poles, the twoare characterised by contrasting qualities. At onepole, there are “heavy” and “rigid” “structures”. Atthe other, there are “lighter and less expensive” 30health care services.Thus, the structure(s), the organizationand the management (i.e. the domain of governmentalreforms and of public interventions) areset in contrast to “programmes and processesof [health] care” (i.e. the domain of physicians’private interventions). 31 The first are bad, thesecond are good. The causes of the crisis of thesystem lie in the first package, which thus getsequated with the system’s deeper essence. Inthe end, the system becomes the equivalent of(the bad) structure, organization and management,or of a badly conceived and badly managedobject of public intervention. 326. Articulations: A New Object of Interventionand New SolutionsThe emphasis on structure, organisationand management serve to construct symbolicallya specific object of public intervention: the system.That the system, as defined above, is thetrue object of the crisis is also proven by the factthat the crisis is much more associated with itthan with other possible objects. Indeed, phraseslike “health care” (“soins de santé”), “healthcare sector” (“secteur de la santé”), “health carenetwork” (“réseau de la santé”) or “health careservices” (“services de santé”) are much lessprone to be seen as an object of the crisis in theQuebec francophone media. A search for associationsbetween each of these phrases and theterm “crisis”, during the same 1988-2003 period,gave <strong>number</strong>s significantly lower than thosefound for the association between “the healthcare system” and the “crisis”. 3328 Le Devoir, November 16, 2002: G5.29 Le Devoir, February 13, 1999: A8.30 Le Devoir, February 13, 1999: A8.31 Le Devoir, August 6, 1999: A932 Thus one can see at work within the crisis discoursediscursive operations (Torfing, 1999: 96-98) of constructingboth relations of difference (between “health care”and “bureaucracy”) and relations of equivalence (betweenbureaucracy, public services and bad management) aroundthe discursive “nodal point” of “the system”.33 Namely, there were 15 articles for "the health carecentar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr23

Sabina Stan: The Discourse on the “Crisis of the Health Care System”suvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1While, within the crisis discourse, otherdomains of public intervention are obscured andignored, the system becomes the focal point towardwhich the problems of the health care sectorconverge. The costs that matter are not “thecosts of health care” (“les coûts des soins de santé”)but “the costs of the public health care system”(“les coûts du système de soins public”). 34Building on organic metaphors so much used insocial sciences (Purvis and Hunt, 1993: 485),the system becomes an organic-like entity that isendowed with an anatomy (“the structure”) and aphysiology (“management”). It becomes even asubjective agent. Indeed, there is a “loss of trustin the health care system” 35 (and not in physiciansor politicians). What needs to be healedare the “evils of our health care system” 36 (andnot of the medical-industrial complex). Finally,when the SARS crisis bursts out in 2003 in Toronto,it is the system that has to deal with thecrisis 37 and that thus makes errors, and it is itwhich is “submerged” and “causes havoc” 38 (andnot health care personnel, hospital administrators,officials or politicians).The symbolic production of a new objectof public and managerial intervention, “the system”,is compounded by the articulation of thenew visions of the crisis and of its causes thatare developed after 1998. Seeing the crisis asgeneral, permanent and intrinsic, as well amenableto internal, structural causes, leads to atotalising vision of the health care network. “Thesystem” becomes an indivisible entity, of whichone can talk as of a singular, identifiable whole.It is seen as homogenous totality and unity, anentity, the functioning and characteristics ofwhich can neither be reduced to its constituent,differentiated, parts, nor emanate from its environment.Instead, they are put into motion by aninternal principle of structuring, organisation andmanagement. As it is contrasted with the privateintervention of physicians or of companies, thisprinciple could be called, even if it is not formulatedas such in the crisis discourse, the publicregulation principle. Underlying the crisis discourseis the idea that public regulation of healthcare services and of public services in general,sector", 54 for "the health care network", 23 for "the healthcare services" and 47 for “health care”. These <strong>number</strong>s wereobtained after subtracting from the initial sums the articlesthat also include the term "system".34 Le Devoir, April 1, 2000: F635 La Presse, June 3, 2000: B236 La Presse, September 13, 2000: B237 Le Soleil, June 1, 2003: A338 Le Soleil, September 22, 2003: A5is bad, and can only lead to the general ills of“bureaucracy” and of “political intervention”.This new vision of the crisis, and of thesystem that bears it, conveys images of a permanentand amplifying crisis that calls for imminentsolutions. Constructing the problems of adomain of public intervention as profound, inherentand permanent, envisioning the object of thisintervention as a totalising system propelled bya functioning principle, and conveying the feelingof the urgency to act, all contribute to the subtleimposition of a certain set of solutions as good,legitimate, and in need of rapid application. Inthis vision, the solution follows obviously andnaturally from the diagnosis. The system has tobe transformed profoundly, and more preciselythrough a change in the principle that rests at itsbasis. “The public” has to give way to “the private”.In line with the diagnosis of “rigid structure”,the call is for “lightening the structures” 39on a model based on private physician cabinets,i.e. by limiting public intervention into the system.In the same vein, the diagnosis of “rigid framing”(read “public” framing) calls for introducing in thesystem “technological and scientific progressesand the new management modes” that form thebasis for the increase in productivity in other sectors.40 Considering that these “new managementmodes” are the ones current in the private, marketsector, what are called for are more “private”and more “market” in the public health care sector.Thus, we can see that the matters atstake in the different symbolic struggles stirredby the crisis discourse are the very foundationalprinciples of the system. The conflicts revolvearound one of the most debated themes inhealth care in Canada and in Quebec, that is,the balance between the private and the publicin the health care system. These conflicts pitchthe promoters of what I will call “marketisation”(i.e. the idea of rendering more market-like thehealth care system) against the defenders of thepublic character of the system. Therefore, I usemarketisation as a short phrase for calls for “givinga stronger place to the private sector”.39 La Presse, February 24, 1999: B340 La Presse, April 27, 1999: B3centar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr24

Sabina Stan: The Discourse on the “Crisis of the Health Care System”suvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1Marketisation constitutes one of themost frequent topics tackled in the articles analysedin this article. More than a third of the articles(48/139) do not restrict themselves to diagnosingthe health care system, but also givesolutions by either proposing or opposing itsradical change through marketisation. Graphic 2shows that, after 1998, in parallel with the rise ofa new vision of the crisis and the system, thereis also a rise of marketisation as one of the mainconcerns of the crisis discourse. 41Moreover, “marketisation” becomes themain solution promoted by the crisis discourse.Of the total <strong>number</strong> of articles explicitly referringto marketisation (48), only a third opposes it(16), whereas the large majority adopts positionsfavourable to it (32 articles).Interestingly, the marketisation debatedoes not neatly follow the right-left divide amongthe chosen dailies. Indeed, if La Presse is themost fervent promoter of marketisation, with 22pro marketisation articles against only 4 countermarketisation articles, Le Soleil shows a morebalanced picture, with a corresponding score of4 vs 4. However, most surprisingly, Le Devoirdoes not oppose marketisation with the samegusto as La Presse promotes it. Indeed, with ascore of 6 vs 8, it engages, considering its leftleaningrenown, only half-heartedly in the attackon marketisation. This indicates that the causeof marketisation has transgressed classical politicalfrontiers, as its progress is facilitated notonly by its strong promotion in right-leaning dailiesbut also by the left-leaning daily’s reluctanceto engage with the topic as well as by its frequentembrace of it.The cutting across of political frontiers ofthe pro-maketisation position is compounded byits discursive fuzziness. Indeed, “marketisation”covers a rather ambiguous discursive place, asarticles do not, contrary to academics and policymakers, dwell on elaborate or even on any definitionat all. As we have seen, in the articles analysedhere, marketisation is reflected in calls for“giving more place to the private sector”. It is becauseof the inherent fuzzy discursive contoursof these calls that they can resonate both withpositions, advocated by some self-alleged leftwingQuebec experts, that defend the introductionof a market-like governance (that would re-41 The only time after 1998 when marketisation wasno longer an issue in the crisis discourse is 2003.At this point, an expectative attitude towards the policies ofthe new govern-ment (Parti libéral, elected in April 2003) andthe quasi-monopolisation of the discoursive domain by theSARS crisis contributed to what can be seen for now a paranthesisin debate.linquish to the private sector only subcontractedauxiliary services that are not seen as “the core”of health care services), and with the positions,advocated by right-leaning experts, that militatefor the outright privatisation of the system by allowingprivate hospitals and clinics and privateinsurance. 42It can thus be said that the discourse onthe crisis of the health care system, as developedin Quebec written media, serves mainly asa vehicle for the promotion of the idea of marketisationof the health care system. Indeed, whilethe crisis discourse was not produced solely byright-leaning privatising voices in media, politicaland expert circles, and left-leaning analystshave not managed to prevent the imposition andfinal dominance of a marketisation stance withinthis discourse and within the larger policy arena.By constructing the system as a public domaindisjointed from private health care provision,and, as such, prone to crisis, the crisis discoursemade space for a neat articulation of marketisationpropositions.Moreover, “marketisation” becomes themain solution promoted by the crisis discourse.Of the total <strong>number</strong> of articles explicitly referringto marketisation (48), only a third opposes it(16), whereas the large majority adopts positionsfavourable to it (32 articles).Interestingly, the marketisation debatedoes not neatly follow the right-left divide amongthe chosen dailies. Indeed, if La Presse is themost fervent promoter of marketisation, with 22pro marketisation articles against only 4 countermarketisation articles, Le Soleil shows a morebalanced picture, with a corresponding score of4 vs 4. However, most surprisingly, Le Devoirdoes not oppose marketisation with the samegusto as La Presse promotes it. Indeed, with ascore of 6 vs 8, it engages, considering its leftleaningrenown, only half-heartedly in the attackon marketisation. This indicates that the causeof marketisation has transgressed classical politicalfrontiers, as its progress is facilitated notonly by its strong promotion in right-leaning dai-42 It could be further argued that the distinctionmany promoters of the new public management make betweenthe “introduction of market mechanisms” (such ascompetition, contracts and outsourcing of auxiliary servicesto the private sector) and outright “privatisation” (which theydefine as the introduction of private hospitals and cabinetsand of private insurance) is in itself a manner of promotingnot only marketisation, but also at least a partial privatisationof the health care system (in the sense that some parts ofthe system are brought under the control of private interests).See, for such an alternative view on the privatisation of thehealth care system, Armstrong and Armstrong (1996, 2008)and Lewis et al. (2001).centar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr25

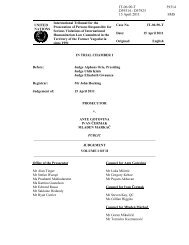

Sabina Stan: The Discourse on the “Crisis of the Health Care System”suvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1Graphic 2Number of articles, per year, defending (M+) or opposing (M-) marketisation in LaPresse, Le Soleil and Le Devoir, between 1988 and 2003Number of articles, per year, defending (M+) or opposing (M-) marketisationin La Presse , Le Soleil and Le Devoir , between 1988 and 2003121086M+M-4201988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003lies but also by the left-leaning daily’s reluctanceto engage with the topic as well as by its frequentembrace of it.The cutting across of political frontiers ofthe pro-maketisation position is compounded byits discursive fuzziness. Indeed, “marketisation”covers a rather ambiguous discursive place, asarticles do not, contrary to academics and policymakers, dwell on elaborate or even on any definitionat all. As we have seen, in the articles analysedhere, marketisation is reflected in calls for“giving more place to the private sector”. It is becauseof the inherent fuzzy discursive contoursof these calls that they can resonate both withpositions, advocated by some self-alleged leftwingQuebec experts, that defend the introductionof a market-like governance (that would relinquishto the private sector only subcontractedauxiliary services that are not seen as “the core”of health care services), and with the positions,advocated by right-leaning experts, that militatefor the outright privatisation of the system by allowingprivate hospitals and clinics and privateinsurance. 4343 It could be further argued that the distinctionmany promoters of the new public management make betweenthe “introduction of market mechanisms” (such ascompetition, contracts and outsourcing of auxiliary servicesto the private sector) and outright “privatisation” (which theydefine as the introduction of private hospitals and cabinetsand of private insurance) is in itself a manner of promotingnot only marketisation, but also at least a partial privatisationof the health care system (in the sense that some parts ofIt can thus be said that the discourse onthe crisis of the health care system, as developedin Quebec written media, serves mainly asa vehicle for the promotion of the idea of marketisationof the health care system. Indeed, whilethe crisis discourse was not produced solely byright-leaning privatising voices in media, politicaland expert circles, and left-leaning analystshave not managed to prevent the imposition andfinal dominance of a marketisation stance withinthis discourse and within the larger policy arena.By constructing the system as a public domaindisjointed from private health care provision,and, as such, prone to crisis, the crisis discoursemade space for a neat articulation of marketisationpropositions.7. Whose Discourse?The notion of a crisis was applied tosocial phenomena ever since analysts tried tomake sense of the political, economic and socialtransformations that shook the Western worldat the end of the 18 th century. Consequent to itssteady success over time, the notion was transformed,in the second half of the 20th century,to an “all-pervasive rhetorical metaphor” (Holton,1987: 502-503) and a “ready-made catchword”the system are brought under the control of private interests).See, for such an alternative view on the privatisation of thehealth care system, Armstrong and Armstrong (1996, 2008)and Lewis et al. (2001).centar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr26

Sabina Stan: The Discourse on the “Crisis of the Health Care System”suvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1(Starn, 1971: 13). But, while the notion of crisisis all pervasive and is used to advance diversepolitical agendas, it has nevertheless been mobilisedwith more success by the right. Indeed,as it was applied with a vengeance in analysesof post oil crisis developments in Western societies,the notion was turned into a major componentof neo-liberal bashing of the welfare state.In this discursive process, the disciplineof management played an important role. Thus,on the one hand, in the struggle over the legitimatedefinition of and scholarship on the notionof crisis, management succeeded in gaining holdon the notion by transforming it into another of itsdomains of expertise. 44 On the other hand, thelate 20 th century also witnessed the introductionof management theories in public administration.The resulting “new public management” broughtinto conjunction both systemic and crisis visionsof public services. This conjunction transformedolder strains of meaning of the notion of crisis.Indeed, older dramaturgical, historical and medicalmeanings construct the crisis as a key buttemporary moment in a developmental cycle(Holton, 1987: 504, Masur, 1975, Starn, 1971).By contrast, in the health care crisis discourseanalysed above, the crisis is seen as a permanentstate and an inherent condition of the system.In a wider perspective, the discourse onthe crisis of the health care system developed inQuebec can be seen as contributing to the widerdiscourse on the crisis of public health care systems,which is itself part of the even wider discourseon the crisis of the welfare state. As withthe latter, the discourse on the crisis of the healthcare system is a global one. Indeed, the last decadewitnessed the development of a transnationalneo-liberal “reforming common sense” inrespect to health care (Serré and Pierru, 2001).Produced by international financial and healthorganisations, this new consensus is based essentiallyon an economic and managerial visionthat obscures and disqualifies political approachesto health issues. Through the production of44 This was specifically done through the "crisismanagement" branch. See, for example, the special <strong>number</strong>of the Journal of Business Administration edited by Smartand Stanbury in 1978, under, significantly for the merger betweenmanagement and public policy, the Institute for Researchon Public Policy. The special <strong>number</strong> was titled Studiesin Crisis Management. Ever since the beginning of the90s, a journal was, specifically dedicated to the topic underthe title Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. Itis interesting to note that management studies’ take-over ofcrisis scholarship and expertise continues the 20 th centurypredominance of classical economy in the handling of thenotion of crisis (Masur, 1978: 590).international data, statistics, classifications andcomparisons, these organizations dramatisethe dysfunctions of existent public health caresystems by diagnosing them with an “efficiencycrisis” having its cause in their bureaucratic organization45 (Serré and Pierru, 2001).This global discourse on crisis provided,to a wide range of actors, a ready repertoire fortalking about problems in the health care sector.Evans noticed, for example, that the decline inhospital use, that followed, in Quebec, the Rochonreforms, has lead to increasing claims, particularlyfrom hospital workers, that “the systemis falling apart”. For him, the declining positionof hospital workers drove them, once “the strongestsupporters of Medicare, 46 into an inadvertentalliance with its traditional enemies” (Evans,2000: 894). These enemies are “powerful interestgroups” that include providers of care (physicians,private insurers and corporate providers),higher-income Canadians, as well as “ideologicalentrepreneurs” that “champion the interestsof the wealthy, cheerleading for the private marketplace”(Evans, 2000: 894-896; also, Evans,2008). Additionally, according to Hutchinsonand his colleagues, crisis statements can alsobe fostered by less ferocious foes of the publicsystem. For example, policy makers keen on effectingchange in the atomised primary care sectoroften have recourse to propositions for radicalchange. For them, crisis statements serve tosecure public and political support to “big bang”approaches (Hutchinson et al., 2001).These diverse statements, claims, andinterests have collided with media campaignsthat have made the Canadian health care crisistheir battle horse. Some analysts saw thus thecrisis discourse as mounted in explicit “disinformationcampaigns” of a “policy warfare” originatingin the neighbouring United States (Evans,2000: 894, 895, Marmor, 1999). The campaignsdeveloped at the beginning of the nineties “as a45 The more so, as some analysts point out, whenmedia's search for sensational revelations weigh the balancetowards the darkest scenario. Thus, for example, whenCanadian media made their selective reading of the 2000WHO report, and chose to downplay a still respectable 7 thplace ranking in terms of goal attainment occupied by theCanadian health care system, for its 30 th rating in terms ofachievement relative to potential. For some analysts, thischoice has contributed to further "promoting an air of crisis"(Lewis et al., 2001: 926).46 In English Canada, “Medicare” is used in referenceto what Quebec terms as “le régime d’assurancemaladie” and sometimes as a synonym for “the health caresystem”. It would be interesting to analyse, in a comparativeperspective, the English media use of “the system” in its discourseon the health care sector.centar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr27

Sabina Stan: The Discourse on the “Crisis of the Health Care System”suvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1side effect to achieve health care reform in theUnited States” and inevitably spilled over intoCanadian media and health services academicand policy literature.But why, for all matters, did the crisis discourseonly enter the Quebec health care arenaonly at the end of the nineties, and why it hastaken this particular form? Of course, the turbulentchanges effected during 90s led the Canadianhealth care system to “an apparent stateof crisis” marked by contradictory measures,services slashing and disorganising restructurings(Lewis et al., 2001: 926). Still, reading theappearance of chaos as a “crisis of the healthcare system” was not the only reading available.Elements of the chaos could still have been readas separate ones, and not necessarily as takingpart in a more total, encompassing crisis of thesystem.For example, one event with importantchaotic consequences for the system, “hospitalclosings” (“fermeture d’hôpitaux”), saw its medianotoriety reach a peak in 1995, 47 but faded awaybefore the take off of the crisis discourse in 1998.By comparison, the more visual events of “emergencyroom crises” (“crises des urgences”) hada media evolution that closely preceded the crisisdiscourse (as it took off in 1998 and reachedits peak in 1999 48 ). It seems that, as media coverageof emergency room crises intensified, it fuelleda more encompassing systemic discourseon the crisis. How did it happen, and why did thecrisis have to be systemic?The particular meaning of the crisisdiscourse stems from larger ideological transformations(i.e. the turn from Keynesianism toneo-liberalism), but also from the conjectural internalstruggles of the social field in which theyare produced (Chalaby, 1996: 691, 694), namelyin this case the francophone journalistic field. InCanada and Quebec, the end of the nineties sawinternal competition inside the field mount in intensity,as francophone and Anglophone mediaalike went through a process of renewed concentration.49 Moreover, the continuous trend of47 The 1995 peak registered more than 160 mentionsof the phenomenon in the three dailies considered here.48 In 1999 there was a peak of 60 articles mentioning“the emergency room crisis” (“la crise des urgences”).49 The dailies analysed here were subject to earlierprocesses of concentration. While Le Devoir always remainedan independent journal, La Presse was bought byQuebec media mogul Paul Desmarais in 1967, and Le Soleilwas purchased by the Hollinger group of Conrad Black in1987 (Gingras, 1999:115, 118). But at the end of the 90s,Canadian media underwent a series of important mergersand buy-outs, leading to "one of the world's highest degreesthe diminishing importance of the written pressvis-à-vis other media (television and internet) putfurther pressure on editors and journalists insidethe written media field.The media’s propensity to offer a moreschematic and dramatic presentation of issueswas compounded with an appearance of chaosin the health care sector, a strengthening of rightwing positions in the Canadian media (Hackettand Gruneau, 2000: 204) and intensified internalcompetition in the journalistic field, to producediscussion of on an encompassing, systemic crisis.By claiming expertise on the health care domain(through powerful statements on the systemiccrisis affecting it), media executives andjournalists not only gave voice to marketisinginterests, but also enhanced their own positionsand established a new symbolic territory (“thehealth care system”) inside a shrinking journalisticfield.Of course, media discourses are not onlythe domain of journalists and editorial boards.One, they are overlapping with and are participatingin larger discourses, such as those developedby governments, experts, or other media.Two, media discourses are not produced solelyby the media, as discourse producers are alwaysmultiple (Chalaby, 1996: 695). In fact, mostof the articles analysed here include (cited orauthored) utterances not only of journalists, butalso of other social actors, such as politicians,officials, experts, representatives or membersof different professional and labour groupings.Journalists are part of a bigger chorus of voices,as they “give form to concerns and problems ofother social worlds, in particular the political andthe administrative ones” (Pierru, 2004: 2).Therefore, we can say that the discourseon the crisis of the health care system in Quebecis produced by a variety of actors and forces: theglobal neo-liberal ideology of welfare state bashing,essays by health care policy makers on advancingmore radical reforms of the health caresector, the intensification of struggles inside thefrancophone journalistic field, as well as contestationsby actors inside the health care field triggeredby health care reforms.of press concentration" (Fleras, 2003: 110). Even if this concentrationaffected less the written Quebec francophonemedia, it certainly affected the manner in which Quebec journalistsperceived their field.centar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr28

Sabina Stan: The Discourse on the “Crisis of the Health Care System”suvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 18. Effects of the Crisis DiscourseThe crisis metaphor not only “gives fullvent to feelings as to the intolerability of thepresent” (Holton, 1987: 504), but also contributesto the cultural construction of this feeling.Moreover, the crisis discourse is not necessarily“suggestive of […] a ‘critical’ standpoint” (Holton,1987: 505), but rather, as the case analysedhere showed, a sign of utopian politics callingfor a radical “dissolution of the public realm”(Clarke, 2004) through the thorough institution ofthe idea of the Market (Carrier, 1997; Newmanand Clarke, <strong>2009</strong>).Appealing to a crisis discourse to qualify“the system” is also a powerful manner to claimknowledge and “truth”. While any discourse embodiesclaims to knowledge (Torfing, 1999, Foucault,1971), the notion of crisis always potentiallyevokes its older meanings of “moment oftruth”, of revelation of the deeper essence of aphenomenon (Starn, 1971: 16). “The crisis of thehealth care system” offers, in this perspective,the revelation of the true nature of the system,construed in this case as being in the same timeevil and bureaucratic (i.e. “public”).The discourse on “the crisis of the healthcare system” contributes to the adoption of policieswith very concrete effects. In Quebec, thecrisis discourse succeeded in radicalising andlimiting policy horizons, by making marketisationseem not only justifiable but also an inevitablecomponent of health care reforms. The ideologicaleffects of the crisis discourse can thus beseen as advancing a more or less hidden marketisationagenda of “powerful interests”. Whilewitnessing a real privatisation of health carethrough the private provision of services not coveredby public funds (Lewis et al., 2001: 927)and discontinuing the historically feeble overtpolitical support for privatisation, the end of the90s saw a powerful current in official, academicand media discourse in Quebec and Canadato giving “more and more prominence to privatesector delivery of health care” (Bernier andDallaire, 2001: 130; Armstrong and Armstrong,2008). Thus, when the Parti libéral took powerin Quebec in April 2003, it committed itself toa marketising and privatising reform the publicacceptance of which was prepared by previousyears of media crisis discourse.Both the Parti libéral commitment to aprivatising stance towards the health care sectorand the public acceptance of this stancewere fully revealed by the July 2005 Chaoulliruling (Crawford, 2006). On this occasion, theSupreme Court of Canada overthrew Quebeclaws banning the purchase of private insurancefor medically necessary services. Seizing theoccasion, the Parti libéral ignored possibilitiesof blocking the ruling and further expanded itseffects by announcing only months later that itwill consider shortly what part the private sectorshould play in health care. At the same time,public reactions to the ruling and to the government’sposition vis-á-vis the ruling have not yetmanaged to consolidate in a powerful movementagainst privatisation. Thus, the crisis discoursemight have realised just this: to trigger maybenot so much deep adhesion to privatisation asindifference and a wait-and-see attitude to thepolicies of a government determined to transformalong market lines the health care sector.Following Mintz, we can distinguish twomeanings of the crisis. On the one hand, the“outside meaning” (Mintz, 1985) of the crisis pertainsto the meanings the crisis has for differentpower holders. Thus, if for government officials,the crisis might constitute a means for legitimisingreform, for private companies, the crisis is ameans for legitimising health care privatization,and, tacitly, profits derived from health care provision.On the other hand, the crisis has also an“inside meaning” (Mintz, 1985), one that pointstowards its meanings for health care workersand patients. In this article I concentrated on thecrisis’ outside meaning, the one related to powerand to powerful actors, to policy shifts and to envisionedgains. Its inside meanings remain yetto be studied and constitute an interesting anglethrough which to approach contemporary healthcare transformations. In fact, the inside meaningof the crisis of the health care system pointsto the novel temporality of the flexible phase ofcapitalism, particularly, in health care, to shiftsin patterns of care away from the hospital andto shorter stays inside the system. Documentingthis temporality of accelerated “people-processing”inside the system and its consequencefor the manner in which the system is lived bythose who are inside it or who are just passingthrough it, constitutes a fruitful agenda for futureresearch.centar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr29

Sabina Stan: The Discourse on the “Crisis of the Health Care System”suvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1ReferencesAdelman, R., Verbrugge, L. (2000): Death Makes the News: The Social Impact of Disease on NewspaperCoverage, Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 41: 347-367Armstrong, P., Armstrong, H. (2008): About Canada: Health Care, Black Point, Nova Scotia: FernwoodPublishingArmstrong, P., Armstrong, H. (1996): Wasting Away: The Undermining of Canadian Health Care. Toronto:Oxford University PressBernier, J., Dallaire, M. (2001): What Price Have Women Paid for Health Care Reform? The Situation inQuebec, in P. Armstrong et al. (eds): Exposing Privatization: Women and Health Care Reform inCanada, Aurora, Ont.: Garamond PressBourdieu, P. (1994): Rethinking the State: Genesis and Structure of the Bureaucratic Field, SociologicalTheory, 12 (1): 1-18Bourdieu, P. (2001): Langage et pouvoir symbolique. Paris: Éditions du SeuilBridgman, T., Barry, D. (2002): Regulation is Evil: An Application of Narrative Policy Analysis to theRegulatory Debate in New Zealand, Policy Sciences, 35: 141-161Brodie, M., Hamel, E., Altman, D., Blendon, R., Benson, J. (2003): Health News and the AmericanPublic, 1996-2002, Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 28 (5): 927-950Carrier, J. (1997): Meanings of the Market: The Free Market in Western Culture, New York: New YorkUniversity PressChalaby, J. K. (1996): Beyond the Prison-House of Language: Discourse as a Sociological Concept,British Journal of Sociology, 47(4): 684-698Clarke, J. (2004): Dissolving the Public Realm? The Logics and Limits of Neo-Liberalism, Journal ofSocial Policy, 33 (1): 27-48Crawford, M. (2006): Interactions: Trade Policy and Healthcare Reform after Chaoulli v. Quebec,Healthcare Policy/Politiques de Santé, 1(2): 90-102Davin, S. (2005): Public Medicine: The Reception of a Medical Drama”, in: King, M., Watson, K. (eds):Representing Health: Discourses of Health and Illness in the Media, New York: Palgrave MacMillanEvans, R. (2008): Reform, Re-form, and Reaction in the Canadian Health Care System, Health LawJournal, 16: 265-286Evans, R. (2000): Canada, Journal of Health Policy, Politics and Law, 25 (5): 889-897Fiss, P., Hirsch, P. (2005): The Discourse of Globalisation: Framing and Sensemaking of an EmergingConcept, American Sociological Review, 70 (1): 29-52Fleras, A. (2003): Mass Media Communication in Canada, Toronto: Harcourt Brace CanadaFoucault, M. (1971): L’ordre du discours: Leçon inaugurale au Collège de France prononcée le 2décembre 1970. Paris: GallimardFrank, T. (2000): One Market under God: Extreme Capitalism, Market Populism, and the End of EconomicDemocracy, New York: Random HouseGingras, A.-M. (1999): Médias et démocratie: Le grand malentendu. Ste-Foy, Qc: PUQHackett, R., Gruneau, R. (2000): The Missing News: Filters and Blind Spots in Canada’s Press. Aurora,Ont.: Garamond PressHenderson, L. (2010): Medical TV Dramas: Health Care Soap Opera, Socialist Register, 46Herdman, E. (2002): Lifelong Investment in Health: The Discursive Construction of Problems in HongKong Health Policy, Health Policy and Planning, 17 (2): 161-166Hilgartner, S., Bosk, C. L. (1988): The Rise and Fall of Social Problems: A Public Arenas Model, AmericanJournal of Sociology, 94 (1): 53-78Holton, R. J. (1987): The Idea of Crisis in Modern Society, The British Journal of Sociology, XXXV<strong>II</strong>I (4):502-520Hutchinson, B., Abelson, J., Lavis, J. (2001): Primary Health Care in Canada: So Much Innovation, SoLittle Change, Health Affairs, 20 (3): 116-131King, M., Watson, K. (eds) (2005): Representing Health: Discourses of Health and Illness in the Media.New York: Palgrave MacMillanKuipers, J. (1989): Medical Discourse’ in Anthropological Context: Views of Language and Power,Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 3 (2): 99-123Lewis, S., Donaldson, C., Mitton, C., Currie, G. (2001): The Future of Health Care in Canada, BritishMedical Journal, 323 (20): 926-9.centar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr30

Sabina Stan: The Discourse on the “Crisis of the Health Care Systemsuvremene TEME, (<strong><strong>2009</strong>.</strong>) God. 2, Br. 1CONTEMPORARY issues, (<strong>2009</strong>) Vol. 2, No. 1Marmor, T. (1999): The Rage for Reform. Sense and Non-sense in Health Policy: Market Limits in HealthReform, in: Drache, D., Sullivan, T. (eds): Public Success, Private Failure, London: RoutledgeMasur, G. (1973): Crisis in History, in: Wiener, I. P. (ed.): Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Studies inSelected Pivotal Ideas Vol. I, New York: Charles Scribner’s SonsMintz, S. (1985): The Sweetness of Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History, New York: VikingNewman, J., Clarke, J. (<strong>2009</strong>): Publics, Politics and Power: Remaking the Public in Public Services,London: SagePierru, F. (2004): La fabrique des palmarès. Genèse d’un secteur d’action publique et renouvellementd’un genre journalistique: les palmarès hospitaliers, in Legavre, J.-B. (ed.): La presse écrite:regards sur un objet délaissé, Paris: L’HarmattanPurvis, T., Hunt, A. (1993): Discourse, Ideology, Discourse, Ideology, Discourse, Ideology..., The BritishJournal of Sociology, 44 (3): 473-499Seale, C. (2004): Health and the Media, Oxford: Wiley-BlackwellSerré, M., Pierru, F. (2001): Les organisations internationales et la production d’un sens communréformateur de la politique de protection maladie, Lien social et politiques, 45: 105-130.Smart, C. F., Stanbury, W. T. (eds) (1978), Studies in Crisis Management: Theme issue of Journal ofBusiness Administration, 9:2Spector, M., Kitsuse, J. (2006): Constructing Social Problems, New Brunswick, N.J.: TransactionPublishersStarn, R. (1971): Historians and ‘Crisis’, Past and Present, 52: 3-22.Torfing, J. (1999): New Theories of Discourse: Laclau, Mouffe and Žižek. Oxford: BlackwellBritishMedical Journal, 323 (20): 926-9.Diskurs o „krizi zdravstvenog sustava” i novi model upravljanjazdravstvenom zaštitom u QuébecuSABINA STANGradsko sveučilište u Dublinu, IrskaTijekom prošlog desetljeća, javni diskurs o „krizi zdravstvenog sustava”u Québecu i Kanadi narastao je do takvih razmjera da je u očima mnogihKvebečana i Kanađana kriza postala trajna značajka sektora zdravstvenezaštite. Na temelju analize članaka iz kvebečkog tiska, članak pokazuje kakodiskurs o krizi pridonosi promicanju tržišno orijentiranog modela upravljanjazdravstvenom zaštitom te potiče prihvaćanje tržišno orijentiranih politika uzdravstvu.Ključne riječi: zdravstvena zaštita, upravljanje, diskurs, kriza, neoliberalizamcentar za politološka istraživanjathe political science research centrewww.cpi.hr31