Landscapes of Hope.pdf - WWF-India

Landscapes of Hope.pdf - WWF-India

Landscapes of Hope.pdf - WWF-India

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005viii

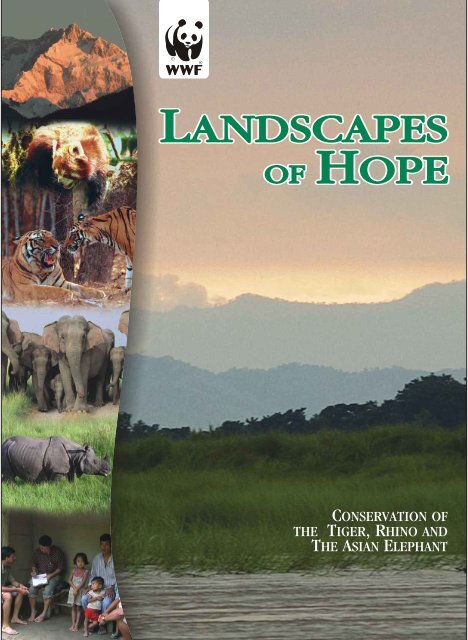

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005LANDSCAPESOF HOPECONSERVATION OF THE TIGER, RHINO ANDTHE ASIAN ELEPHANTA Review <strong>of</strong> <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>’sSpecies Conservation Programme<strong>WWF</strong>-INDIADECEMBER, 2007for a living planeti

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005Species Conservation Programme<strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> SecretariatSujoy BanerjeeTariq AzizDr. Diwakar SharmaRenu AtwalJagdish UpadhyayaField OfficesDr Harish Kumar (Terai Arc Landscape - Pilibhit Office)Dr. Shivaji Chavan (Satpuda Maikal Landscape)Mohan Raj (Nilgiri Eastern Ghats)Dr. Anupam Sarwah (North Bank Landscape)Dr. Anurag Danda (Sundarbans)K. D. Kandpal (Terai Arc Landscape - Ramnagar Office)December 2007This publication has been produced by the Species Conservation Programme, <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> Secretariat,New Delhi. Editorial and Production Consultant : Tapan K Ghosh. Cover Design byGulshan Malik. Printed by Adstrings Advertising Pvt Ltd, New Delhi.Maps used in this publication are not to scale and for illustrative purpose only. Photo Credits: In-houseii

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005CONTENTSForeword by CEO & SGPrefacevviiPart One : Genesis and Development <strong>of</strong> the Programme1. Genesis and Development: the First Five Years 22. Looking at <strong>Landscapes</strong>: a Critical Milestone 6Part Two : <strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong> : from Confrontation to Co-existence3. Terai Arc Landscape 104. Satpuda Maikal Landscape 265. Sundarbans Landscape 326. North Bank Landscape (NBL) 397. Nilgiri Eastern Ghats (NEG) 468. Khanchendzonga Landscape (KL): Sikkim & Adjacent Areas 559. Kaziranga-Karbi Anglong Landscape (KKAL) 61Part Three : Co-existence with Wild Life : Way Forward10. Some Thoughts on the Way Forward 7211. Milestones 76iii

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005This publicationis dedicated to the memory <strong>of</strong>Pankaj SarmahA committed worker <strong>of</strong> the North Bank Landscape Programme,he knew how to follow, he knew how to leadMr Pankaj Sarmah was very well known amongconservationists and researchers working on Asianelephants. In North East <strong>India</strong>, he was among the firstto establish a scientific basis for conservation <strong>of</strong>elephants and was highly respected for it. His workhas been appreciated in <strong>India</strong> and abroad.He joined <strong>WWF</strong> <strong>India</strong> in 21 June 2001 at a time when<strong>WWF</strong> was initiating its work on conservation <strong>of</strong>Asian elephants in North Bank Landscape (NBL) inNE <strong>India</strong>. Information on elephants in NBL at thatpoint <strong>of</strong> time was negligible and at best anecdotal.His initial work on elephants not only generatedscientific data on the state <strong>of</strong> elephants but alsohelped establish NBL as an entity, which has nowbecome a globally recognized name. He worked withmeagre resources <strong>of</strong> the just initiated NBL projectunder very tough field circumstances which includeda deteriorating law and order situation inAssam and hostile forests infested by a host <strong>of</strong>diseases.Pankaj Sarmah’s work, as we see in NBL today, isprimarily responsible for establishing commitmentson elephant conservation from a large body <strong>of</strong>researchers, conservationists and the Government.His pioneering work also created benchmarks onfield based research and conservation for others t<strong>of</strong>ollow in the region.Pankaj was able to give a new vision to <strong>WWF</strong>AREAS NBL project. He proved to be a leader byexample, which helped develop confidence <strong>of</strong> notonly <strong>of</strong> his colleagues, but also the Governmentfunctionaries and communities living in and aroundelephant habitats.Most recently, he was instrumental in formingthe Manas Conservation Alliance, a coalition <strong>of</strong>NGOs and individuals committed to conservingManas National Park. He represented <strong>WWF</strong> inseveral symposia, seminars and workshops with in<strong>India</strong> and abroad.He had a very positive attitude and an exceptionallycheerful nature and a unique ability to reach out topeople at different levels. He chose to be in conservationat very early age in his life and stuck to hisconviction till the end. He was passionate to thecause <strong>of</strong> conservation. His loyalty to theorganisation was unmatched during his life longtenure with <strong>WWF</strong>.Pankaj Sarmah fell prey to cerebral malariawhile in the field and succumbed to it on the3 October 2006. He was born on the 27th February1976, did his masters from Guwhahti University andwas working for a PhD on elephants in Assam.iv

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005FOREWORDA few years ago <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> brought out the Road to Redemption which traced the history <strong>of</strong> ourSpecies Conservation division’s work from its inception in the mid-90s. In 2002, <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>adopted the landscape approach in its overall strategic thinking. This involved a huge shift; fromstrengthening enforcement capacity in select protected areas to working in larger regions with astring <strong>of</strong> protected areas that could be connected to ensure a large safe habitat for wildlife. It meantworking with communities living in and on the fringes <strong>of</strong> forested areas who shared the samehabitat. It meant establishing rapport with them and ensuring alternative livelihoods to reduce theirdependence on forests and the inevitable confrontation with wildlife. It also meant that theelements <strong>of</strong> mitigating human-wildlife conflict be brought in as one <strong>of</strong> the core aspects <strong>of</strong> ourconservation work.The present publication takes up where Road to Redemption ended. As the document amply bringsout, the landscape approach meant a large investment in terms <strong>of</strong> time and resources in establishingfield <strong>of</strong>fices in critical areas to manage the landscape programmes. Acceptance by the localcommunities was not easy considering the socio-cultural diversity which the programme was facing.As the first phase <strong>of</strong> our initiatives have come to an end in June 2006, <strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong> documentsthe travails and challenges <strong>of</strong> our species programme. The last 4 years have taught us invaluablelessons which are being shared through this report. It is hoped this will provide a deeper insight tochallenges in wildlife conservation in the context <strong>of</strong> developing an environment where both humansand wildlife can live in harmony and where india’s natural heritage continues to be secured for thefuture.Still this report only shows some vignettes in the entire canvas. The work <strong>of</strong> <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>’s teamgoes largely unreported: the daily duty <strong>of</strong> field work, the adherence to work plans and conservationimplementation, the constant dialogues planning and working initiatives. For this, the dedication <strong>of</strong>the team needs a special salute.Ravi SinghCEO & SG<strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>v

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005vi

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005PREFACE FROM THE DIRECTORIt is my privilege to be writing this preface for two reasons. The first, that this is the firstopportunity for me to talk about the exciting conservation initiatives being undertaken in thelandscapes, to talk about the achievements <strong>of</strong> these programmes, and to delve upon the issue <strong>of</strong>what went right and what did not. The second, that this is a testimony to the sincere efforts <strong>of</strong> ourfield team, who are dedicated to conservation and draw immense satisfaction in the work they areundertaking.This publication is being released at a time when all’s not well from the conservation point <strong>of</strong> view.The recent presentation on tiger estimation only reiterates the apprehension <strong>of</strong> the conservationcommunity: tiger numbers are precariously low and habitats are under tremendous threat. In case <strong>of</strong>elephants, the recent past has witnessed a pronounced escalation in human-elephant conflict (ormaybe the correct word to be used here is Elephant-Human conflict, for it is the humans who areusurping elephant habitats) resulting in deaths <strong>of</strong> both elephants and humans. There have beenseveral cases <strong>of</strong> rhino poaching also emphasizing the need for escalation <strong>of</strong> protection <strong>of</strong> thesespecies. The same is the case for many other wildlife species as well.But the scenario also demands that help and support should be given for conservation <strong>of</strong> wildlife in<strong>India</strong> from all quarters, and organizations and institutions involved in conservation should make aconcerted effort to help these magnificent wildlife species survive in the wild. It provides us anopportunity to sit back and introspect to make our conservation initiatives more focussed andpointed.The “<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong>”, on which work was initiated during the tenure <strong>of</strong> my predecessor,Mr. P.K. Sen, has been aptly named. It is this message <strong>of</strong> “hope” that we would want to spreadthrough this publication, and we at <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> are confident that a positive change is possible andwe would leave no stone unturned to meet this end.Our donors and partners need a special mention here, without the support <strong>of</strong> whom, the work inthe landscapes would not have been possible. The donors and partners have never lost sight <strong>of</strong> thebroad conservation issues in <strong>India</strong>. They have stood by us through thick and thin, been veryunderstanding and accommodating, and have continuously supported these programmes on a longtermbasis. They deserve credit for successes attained in our landscapes.Sujoy BanerjeeDirector,Species Conservation Programmevii

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005viii

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005LANDSCAPESOF HOPECONSERVATION OF THE TIGER, RHINO ANDTHE ASIAN ELEPHANTA Review <strong>of</strong> <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>’sSpecies Conservation Programme<strong>WWF</strong>-INDIADECEMBER, 2007for a living planeti

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005Species Conservation Programme<strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> SecretariatSujoy BanerjeeTariq AzizDr. Diwakar SharmaRenu AtwalJagdish UpadhyayaField OfficesDr Harish Kumar (Terai Arc Landscape - Pilibhit Office)Dr. Shivaji Chavan (Satpuda Maikal Landscape)Mohan Raj (Nilgiri Eastern Ghats)Dr. Anupam Sarwah (North Bank Landscape)Dr. Anurag Danda (Sundarbans)K. D. Kandpal (Terai Arc Landscape - Ramnagar Office)December 2007This publication has been produced by the Species Conservation Programme, <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> Secretariat,New Delhi. Editorial and Production Consultant : Tapan K Ghosh. Cover Design byGulshan Malik. Printed by Adstrings Advertising Pvt Ltd, New Delhi.Maps used in this publication are not to scale and for illustrative purpose only. Photo Credits: In-houseii

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005CONTENTSForeword by CEO & SGPrefacevviiPart One : Genesis and Development <strong>of</strong> the Programme1. Genesis and Development: the First Five Years 22. Looking at <strong>Landscapes</strong>: a Critical Milestone 6Part Two : <strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong> : from Confrontation to Co-existence3. Terai Arc Landscape 104. Satpuda Maikal Landscape 265. Sundarbans Landscape 326. North Bank Landscape (NBL) 397. Nilgiri Eastern Ghats (NEG) 468. Khanchendzonga Landscape (KL): Sikkim & Adjacent Areas 559. Kaziranga-Karbi Anglong Landscape (KKAL) 61Part Three : Co-existence with Wild Life : Way Forward10. Some Thoughts on the Way Forward 7211. Milestones 76iii

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005This publicationis dedicated to the memory <strong>of</strong>Pankaj SarmahA committed worker <strong>of</strong> the North Bank Landscape Programme,he knew how to follow, he knew how to leadMr Pankaj Sarmah was very well known amongconservationists and researchers working on Asianelephants. In North East <strong>India</strong>, he was among the firstto establish a scientific basis for conservation <strong>of</strong>elephants and was highly respected for it. His workhas been appreciated in <strong>India</strong> and abroad.He joined <strong>WWF</strong> <strong>India</strong> in 21 June 2001 at a time when<strong>WWF</strong> was initiating its work on conservation <strong>of</strong>Asian elephants in North Bank Landscape (NBL) inNE <strong>India</strong>. Information on elephants in NBL at thatpoint <strong>of</strong> time was negligible and at best anecdotal.His initial work on elephants not only generatedscientific data on the state <strong>of</strong> elephants but alsohelped establish NBL as an entity, which has nowbecome a globally recognized name. He worked withmeagre resources <strong>of</strong> the just initiated NBL projectunder very tough field circumstances which includeda deteriorating law and order situation inAssam and hostile forests infested by a host <strong>of</strong>diseases.Pankaj Sarmah’s work, as we see in NBL today, isprimarily responsible for establishing commitmentson elephant conservation from a large body <strong>of</strong>researchers, conservationists and the Government.His pioneering work also created benchmarks onfield based research and conservation for others t<strong>of</strong>ollow in the region.Pankaj was able to give a new vision to <strong>WWF</strong>AREAS NBL project. He proved to be a leader byexample, which helped develop confidence <strong>of</strong> notonly <strong>of</strong> his colleagues, but also the Governmentfunctionaries and communities living in and aroundelephant habitats.Most recently, he was instrumental in formingthe Manas Conservation Alliance, a coalition <strong>of</strong>NGOs and individuals committed to conservingManas National Park. He represented <strong>WWF</strong> inseveral symposia, seminars and workshops with in<strong>India</strong> and abroad.He had a very positive attitude and an exceptionallycheerful nature and a unique ability to reach out topeople at different levels. He chose to be in conservationat very early age in his life and stuck to hisconviction till the end. He was passionate to thecause <strong>of</strong> conservation. His loyalty to theorganisation was unmatched during his life longtenure with <strong>WWF</strong>.Pankaj Sarmah fell prey to cerebral malariawhile in the field and succumbed to it on the3 October 2006. He was born on the 27th February1976, did his masters from Guwhahti University andwas working for a PhD on elephants in Assam.iv

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005FOREWORDA few years ago <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> brought out the Road to Redemption which traced the history <strong>of</strong> ourSpecies Conservation division’s work from its inception in the mid-90s. In 2002, <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>adopted the landscape approach in its overall strategic thinking. This involved a huge shift; fromstrengthening enforcement capacity in select protected areas to working in larger regions with astring <strong>of</strong> protected areas that could be connected to ensure a large safe habitat for wildlife. It meantworking with communities living in and on the fringes <strong>of</strong> forested areas who shared the samehabitat. It meant establishing rapport with them and ensuring alternative livelihoods to reduce theirdependence on forests and the inevitable confrontation with wildlife. It also meant that theelements <strong>of</strong> mitigating human-wildlife conflict be brought in as one <strong>of</strong> the core aspects <strong>of</strong> ourconservation work.The present publication takes up where Road to Redemption ended. As the document amply bringsout, the landscape approach meant a large investment in terms <strong>of</strong> time and resources in establishingfield <strong>of</strong>fices in critical areas to manage the landscape programmes. Acceptance by the localcommunities was not easy considering the socio-cultural diversity which the programme was facing.As the first phase <strong>of</strong> our initiatives have come to an end in June 2006, <strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong> documentsthe travails and challenges <strong>of</strong> our species programme. The last 4 years have taught us invaluablelessons which are being shared through this report. It is hoped this will provide a deeper insight tochallenges in wildlife conservation in the context <strong>of</strong> developing an environment where both humansand wildlife can live in harmony and where india’s natural heritage continues to be secured for thefuture.Still this report only shows some vignettes in the entire canvas. The work <strong>of</strong> <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>’s teamgoes largely unreported: the daily duty <strong>of</strong> field work, the adherence to work plans and conservationimplementation, the constant dialogues planning and working initiatives. For this, the dedication <strong>of</strong>the team needs a special salute.Ravi SinghCEO & SG<strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>v

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005vi

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005PREFACE FROM THE DIRECTORIt is my privilege to be writing this preface for two reasons. The first, that this is the firstopportunity for me to talk about the exciting conservation initiatives being undertaken in thelandscapes, to talk about the achievements <strong>of</strong> these programmes, and to delve upon the issue <strong>of</strong>what went right and what did not. The second, that this is a testimony to the sincere efforts <strong>of</strong> ourfield team, who are dedicated to conservation and draw immense satisfaction in the work they areundertaking.This publication is being released at a time when all’s not well from the conservation point <strong>of</strong> view.The recent presentation on tiger estimation only reiterates the apprehension <strong>of</strong> the conservationcommunity: tiger numbers are precariously low and habitats are under tremendous threat. In case <strong>of</strong>elephants, the recent past has witnessed a pronounced escalation in human-elephant conflict (ormaybe the correct word to be used here is Elephant-Human conflict, for it is the humans who areusurping elephant habitats) resulting in deaths <strong>of</strong> both elephants and humans. There have beenseveral cases <strong>of</strong> rhino poaching also emphasizing the need for escalation <strong>of</strong> protection <strong>of</strong> thesespecies. The same is the case for many other wildlife species as well.But the scenario also demands that help and support should be given for conservation <strong>of</strong> wildlife in<strong>India</strong> from all quarters, and organizations and institutions involved in conservation should make aconcerted effort to help these magnificent wildlife species survive in the wild. It provides us anopportunity to sit back and introspect to make our conservation initiatives more focussed andpointed.The “<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong>”, on which work was initiated during the tenure <strong>of</strong> my predecessor,Mr. P.K. Sen, has been aptly named. It is this message <strong>of</strong> “hope” that we would want to spreadthrough this publication, and we at <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> are confident that a positive change is possible andwe would leave no stone unturned to meet this end.Our donors and partners need a special mention here, without the support <strong>of</strong> whom, the work inthe landscapes would not have been possible. The donors and partners have never lost sight <strong>of</strong> thebroad conservation issues in <strong>India</strong>. They have stood by us through thick and thin, been veryunderstanding and accommodating, and have continuously supported these programmes on a longtermbasis. They deserve credit for successes attained in our landscapes.Sujoy BanerjeeDirector,Species Conservation Programmevii

<strong>WWF</strong> T&WL Activity report 2003-2005viii

Part OneGENESIS ANDDEVELOPMENT OFTHE PROGRAMMEIn the initial years, theemphasis was onstrengthening the enforcementcapacity <strong>of</strong>select protected areasacross the country1

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong>Chapter 1THE FIRST FIVE YEARSThe tiger has always been at the centre <strong>of</strong><strong>WWF</strong>’s wildlife conservation efforts. But whatis today one <strong>of</strong> the largest wildlife conservationprogrammes run by a non government organization,started in mid-1990 in a small way inresponse to the looming tiger crisis and theinternational attention it received. After muchdeliberation, a criteria was formulated, toidentify and focus on certain protected areas forimmediate infrastructure support and therebystrengthen their enforcement capabilities.Subsequently, initiatives to recognize andreward good work by enforcement staff, training,education and awareness were commenced.Again in response to the situation on the groundwhich showed a spurt in retaliatory poisoningcases, a very important quick- response scheme– the Cattle Compensation Scheme (CCS) wasbegun to supplement the government’s compensatorymechanism for people who lost theircattle to predating tigers.Over the next five years, the tiger conservationprogramme (TCP) as it was now known,matured and evolved into one <strong>of</strong> the largest nongovernmentalintervention to save the tiger andits habitat. Site specific campaigns (like AkhandShikar), legal redressal workshops, monitoringand wildlife trade related workshops, regionalcooperation workshops and a tiger emergencyfund (an emergency funding mechanism) a rapidresponce mechanism were some componentsthat were incorporated into the programme.The mainstay <strong>of</strong> the programme continued to bedirect infrastructure support to Protected Areas(PAs) which included equipment, vehicles,clothing, patrol camps and the like, and by theyear 2000 over 20 PAs across the country werebeneficiaries <strong>of</strong> the programme. Let us look atsome <strong>of</strong> these initiatives in some detail.» Cattle Compensation Scheme: Followingmedia attention on tiger poisoning cases inCorbett and Dudhwa Tiger Reserves, TCPdecided to create a system <strong>of</strong> immediate compensationpayment through a network <strong>of</strong>established local NGOs after necessaryverification <strong>of</strong> cattle kills. The governmentalready had such a scheme in many areas, butthe execution <strong>of</strong> scheme was slow and theamount meagre. By end January 1998, the TCPscheme was functioning in Dudhwa and in acouple <strong>of</strong> months, covered Corbett andKatarniaghat. Subsequently, with some modificationsit was extended to five PAs in AndhraPradesh, Palamau TR in Bihar andRanthambhore TR in Rajasthan. In most casescompensation was received by the owner <strong>of</strong> thelivestock in 48 hours. By December 1999, TCP2

Genesis and Development <strong>of</strong> the Programmehad compensated some 1260 cattle kills at a cost<strong>of</strong> approximately Rs. 12.5 lacs. This initiativehad a positive impact on retaliatory killing <strong>of</strong>tigers by aggrieved villagers, particularly in theCorbett, Dudhwa, Palamau TRs andKaterniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary, as an evaluationby the WII confirmed.» Campaign to curb “Akhand Shikaar”:TCP’s attention was drawn to the ritual huntingknown as Akhand Shikaar, by large tribalgroups, which would peak in April-May everyyear and threaten the tiger’s prey base. Thetribals would also burn down forest areas in anattempt to flush out animals for the ritualistickill. To curb this practice, TCP in associationwith local NGOs built direct rapport with headmen <strong>of</strong> three tribes – Santhal, Munda and Ho –and got their commitment against AkhandShikaar and burning <strong>of</strong> forests. Senior triballeaders employed in anti-poaching camps helpedto influence the youth and alternatives, such asdancing competition were organized during thehunting period. Local NGOs later continuedthe campaign as part <strong>of</strong> their own agenda.tiger conservation: This initiative was undertakeninitially by TCP alone, and later withPATA. This is a scheme to recognize meritoriousservice/contribution by individuals orinstitutions involved in tiger conservation work.Between 1998 and 2000, the awards for meritoriousservice were announced and presentedthrice.» Tiger Emergency Fund (TEF): A quickresponse fund was established to help in emergencysituations at the field level. One <strong>of</strong> thefirst beneficiaries was Kaziranga National Parkwhere devastating floods in 1988 caused havocto wildlife and emergent support from TEFprovided much needed relief measures. Subsequentlythe fund supported fire control inPanna, anti-poaching in Corbett and droughtrelief measures in Sariska and Ranthambore.» Regional cooperation workshops: A transborderworkshop involving Nepal was organizedin February 1999 to orient managers <strong>of</strong> transbordersprotected areas both in <strong>India</strong> and Nepalin an attempt to improve cross in border wildlifeconservation. An action plan emerged fromthis deliberation to counteract poaching andillegal trade across the Indo-Nepal borderthrough improved training, intelligence networkingand funding. Legal addressal workshops: Workshops areheld at different venues to familiarize field staffon legal procedure so as to improve convictionrate and thereby the morale <strong>of</strong> the staff. Monitoring and control <strong>of</strong> wildlife trade:Workshops/Seminars are organized with otheragencies <strong>of</strong> the government involved in monitoringand countering illegal trade in wildlifeand its derivatives; support to set up intelligencenetworks, etc.Awards for exceptional contributions to3

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong>PROTECTEDAREAS AND FOREST DIVISIONSSUPPORTED BY <strong>WWF</strong>-INDIA4

Genesis and Development <strong>of</strong> the ProgrammeExtremely conscious <strong>of</strong> the need to monitor andconstantly revaluate, <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> organized anindependent evaluation <strong>of</strong> the tiger conservationinitiatives in 11 PAs in 1999 itself. The expertsengaged for this task provided overall a positivefeedback with staff morale and efficiencyshowing a definite upward trend. Expectedly,there were occasional reports <strong>of</strong> misuse <strong>of</strong>vehicles, underutilization <strong>of</strong> equipment and needfor further critical assistance. But nonetheless itwas apparent that the programme had made animpact in the field, however small or scattered.Most <strong>of</strong> the PAs supported had managed toimprove their enforcement capacity and several<strong>of</strong> them were able to tide over natural criseswith emergent support from the TEF. One <strong>of</strong>the most encouraging field assessments <strong>of</strong> theprogramme was received in February 2003 fromthe Director, Project Tiger. In a letter to theprogramme director, he said, “Recently, I visitedsome <strong>of</strong> the Tiger Reserves in Central <strong>India</strong> andMaharashtra [(Kanha, Pench (MP) andMaharashtra)], and was really impressed by thesupport provided to these field formations by<strong>WWF</strong>-TCP. In Kanha and Pench the frontlinestaff have benefited from the bicycles providedto them, since they live in remote patrollingcamps away from connecting roads. Likewise,the support given to Pench is also praise-worthy.It goes without saying that such a support wouldgo a long way in complementing the initiativesunder Project Tiger and I wish to place onrecord my deep appreciation <strong>of</strong> your endeavourin this regard”.On balance, it could be concluded that while<strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>’s infrastructure support to PAs didnot show results immediately in quantifiableterms, it allowed the <strong>of</strong>ficial machinery t<strong>of</strong>unction better by filling in crucial gaps andenhancing the morale and efficiency <strong>of</strong> theenforcement staff. Direct support definitelycontributed to curbing poaching in most <strong>of</strong> thePAs which have been beneficiaries.Anti-poaching camps5

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong>Chapter 2:LOOKING AT LANDSCAPES: A CRITICAL MILESTONEEven as the tiger conservation programmecontinued to grow and make its presence felt inthe field, the winds <strong>of</strong> change in terms <strong>of</strong>strategic vision were blowing. The <strong>WWF</strong> globaltiger conservation strategy workshop held inIndonesia in September 2000, was a criticalmilestone in that it formalized a new vision andapproach to the whole issue <strong>of</strong> tiger conservationin the long term. Small populations inisolated protected areas all over the range states,it was agreed, had a limited potential <strong>of</strong> survivalover the long run, mainly due to adverse consequences<strong>of</strong> inbreeding and stifled gene pools.The areas with a certain minimum population<strong>of</strong> breeding tigresses along with a healthycomponent <strong>of</strong> males, sub-adults and cubs, <strong>of</strong>feredthe best possibilities for tiger survival. This wasthe underlying reason for the shift <strong>of</strong> focus fromsupporting scattered PAs to rebuilding andsecuring larger landscapes.The document Conserving Tigers in the Wild:<strong>WWF</strong> Framework and Strategy for Action 2002-2010 defines a tiger conservation landscape as“an area <strong>of</strong> land, regional in scale, that cansupport and maintain, over the long-term, aviable meta-population <strong>of</strong> tigers, linked by safeand suitable habitat, together with an adequatenatural prey base”. Explaining the conceptfurther, the document states: “On the ground, atiger conservation landscape will <strong>of</strong>ten equate toa series <strong>of</strong> well managed core protected areas(national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, etc.) linkedtogether by dedicated corridors <strong>of</strong> suitablehabitat or by land-use that is tiger-friendly in itsstatus and management.”<strong>India</strong> has at least seven tiger landscapes that arecomparable with the best in all the tiger rangeConserving Tigers in the wild: A <strong>WWF</strong>Framework and Strategy for Action 2002– 2010The Vision “Tigers thrive in natural habitats,and people benefit as a result”.The Programme Goal “To conserve viable tigerpopulations, with public support, in the selectedlandscapes, and reduce trade in tiger parts andproducts to a level which is no longer threateningto the survival <strong>of</strong> tigers in the wild”.<strong>WWF</strong> Tiger Action Plan: The TargetsTarget 1 To establish well managed networks<strong>of</strong> core protected areas and connecting tigerfriendly buffer zones and corridors in the focaltiger conservation landscapes selected from acrossthe tiger’s range.Target 2 To reduce (with a view to its elimination)the trade in tiger and products to a levelwhich no longer threatens the survival <strong>of</strong> tigersin the world.states. However, as <strong>WWF</strong> had to make effortsto conserve all the sub species <strong>of</strong> the tiger, itselected seven different landscapes across theworld. Of these, three fall within <strong>India</strong>, eithercompletely or partially. These are the “TeraiArc,” which is shared with Nepal, theSundarban, shared with Bangladesh, and theSatpuda-Maikal range in central <strong>India</strong>. The lastis also fondly referred to as “Kipling country”.The Terai Arc and Kipling’s country are verylarge tracts <strong>of</strong> prime tiger habitat consisting <strong>of</strong> a6

Genesis and Development <strong>of</strong> the Programmeseries <strong>of</strong> protected areas interconncted throughterritorial forest divisions. Protected areas likeRajaji, Corbett, Dudhwa, Katerniaghat,Sohelwa, Suhagi Barua and Valmiki are coverdon the <strong>India</strong>n side under the Terai Arc SuklaPhanta, Bardia, Chitwan and Parsa are on theNepalese side. Kipling’s country comprisesMelght, Satpuda, Pench (Maharashtra), Pench(Madhya Pradesh), Kanha and Achanakmaralong with the connecting forest. TheSundarbans landscape consists <strong>of</strong> the mangroves<strong>of</strong> both <strong>India</strong> and Bangladesh, an area that theconsiderd unique as a tiger habitat.The strategic shift and change in vision meant achange <strong>of</strong> focus in action plans as well. It wasno longer enough to strengthen enforcementcapabilities, contain human-animal conflictwith various mitigation measures and recognizemeritorious work <strong>of</strong> field staff. The vision forthe next 5 to 10 years had to be concretizedwith active cooperation <strong>of</strong> the local people inhabiting the critical landscape areas. Factors liketheir poverty, sources <strong>of</strong> livelihood, and theirthreat perception from wildlife were now to becrucial considerations in any action plan. Peopleliving in forests or in proximity to wildlifehabitats were now to be both partners in, andbeneficiaries <strong>of</strong>, conservation. Stakeholderworkshops were planned and conducted in 2001-02 for the priority landscapes to ensure cooperationand commitment from local communitieswho were to be affected by the new programmethrust. Simultaneously, TCP took on a widermandate as the Tiger and Wildlife Divisionincorporating a special programme for theprotection <strong>of</strong> the <strong>India</strong>n Rhino and the AsianElephant.Asia Rhino and Elephant ActionStrategythat long-term conservation <strong>of</strong> these endangeredspecies is only possible through a landscapebasedapproach that goes beyond isolated protectedareas and includes the surroundinglandscapes and related land-use practices. In factthis was the vision first put across in a <strong>WWF</strong>/TRAFFIC Strategy meeting held in Ho ChiMinh City in 1998. Thirteen priority landscapesaddressing cross-cutting issues like trade, elephantsin domestication and human-wildlifeconflict were identified.<strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> has now a programme on theconservation <strong>of</strong> Asian elephants and <strong>India</strong>n onehornedrhino in four identified priority landscapesin <strong>India</strong>. These are the Nilgiris-EasternGhats (elephants) in South <strong>India</strong>, the NorthBank landscape (elephants), the Kaziranga-KarbiAnglong (rhinos and elephants) in Assam andTerai Arc (rhino and elephant) in UttarPradesh. Notably, these landscapes are refuge tothe largest population <strong>of</strong> Asian elephants and<strong>India</strong>n rhinos.The two landscapes <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> took up in thefirst phase were Nilgiris Eastern Ghats (NEG)and North Bank Landscape (NBL). A briefpr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> these two landscapes would be useful.The Nilgiris Eastern Ghat (NEG) landscape, anarea <strong>of</strong> over 12,000 sq kms, harbours the greatestnumber <strong>of</strong> Asia elephants in the world, estimatedat 6,300 to 10,000, their habitats rangeApart from tigers, <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> expanded itslandscape approach in 2000 to include theconservation <strong>of</strong> mega herbivores, the <strong>India</strong>nRhino and Asian Elephant. The Asian Rhinoand Elephant Action Strategy (AREAS) is a<strong>WWF</strong> initiative in response to the recognition7

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong>from evergreen and dry deciduous forest to thornscrub jungle and grasslands. Other large mammalssuch as gaur, sambar and the tiger alsoabound in the landscape. The landscape comprisesElephant Range No. 7 <strong>of</strong> Project Elephant,a conservation project <strong>of</strong> <strong>India</strong>n government.<strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>’s AREAS programmeinitially is concentrating on securing the riverMoyar elephant corridor, located at the junction<strong>of</strong> Eastern Ghats and Western Ghats in theSouthern part <strong>of</strong> the <strong>India</strong>. It maintains thecontiguity between the Thallamalai plateau inthe east, the Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary inthe west and Bandipur Tiger Reserve in thenorth.Since the landscape comprises three South<strong>India</strong>n States (Karnataka, Kerala andTamilnadu), the issues vary greatly. The impliesthe need to identify and prioritize them. Thestakeholders’ workshop that was held in November2000 was organized with precisely thisagenda. Apart from forest departments <strong>of</strong> thethree States, the workshop was attended byresearch institutions, NGOs and conservationscientists. The participants listed out six majoraction points with the aim <strong>of</strong> reaching thefollowing objective: “A landscape with ahealthy, viable elephant population co-existingwith human development aspirations in thelong term.”The North Bank Landscape (NBL) is one <strong>of</strong> themost important sites for the Asian elephant.The landscape may be home to upto 3000 Asianelephants. The ecological importance <strong>of</strong> thisregion goes far beyond the single species level. Itis a globally recognized biodiversity hotspot andone <strong>of</strong> <strong>WWF</strong>’s Global 200 eco-regions. OverlappingManas-Namdhapa Tiger Conservation unit,it encompasses several <strong>WWF</strong> Tiger ConservationProject sites and is considered one <strong>of</strong> thekey sites for <strong>WWF</strong>’s strategy for eco-regionbased conservation. NBL includes a number <strong>of</strong>protected areas and presents an ideal opportunityfor proactive conservation measures.The North Bank Landscape project aims tosecure the elephant population for the long termby maintaining habitat contiguity, significantlyreducing existing and potential threats, andbuilding pr<strong>of</strong>essional and public support forconservation <strong>of</strong> the elephant population and itshabitat.Other <strong>Landscapes</strong>After <strong>WWF</strong> presence was well established inNBL and NEG two more landscapes were takenup in 2005: the Khanchendzonga landscape inSikkim with a focus on the Red Panda andKaziranga Karbi Aglong (Assam), a haven forthe larger mammals. The programme in effect,became a full-fledged Species ConservationProgramme. Groundwork for both theinitiatives has begun and though it is too earlyto make any assessment <strong>of</strong> future successes orsetbacks, a brief review <strong>of</strong> the progress is givenin part two <strong>of</strong> this document.8

Part TwoLANDSCAPESOF HOPE :Confrontationto Co-existenceThe new strategy now is to look at“an area <strong>of</strong> land, regional in scale,that could support and maintain,over the long-term, a viable metapopulation<strong>of</strong> tigers, linked bysafe and suitable habitat, togetherwith an adequate natural preybase”. This automatically impliesthe conservation <strong>of</strong> other megaspecies under threat and bringingpeople into conservation.9

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong>Chapter 3TERAI ARC LANDSCAPEIntroductionThe Terai Arc Landscape (TAL) is defined as thearea confined between the River Bagmati in theeast and River Yamuna in the west, all along theShiwalik hills in <strong>India</strong> and Churia hills in Nepal. Itcomprises Himalayan foothills, the terai floodplains and Bhabhar tracts. Stretching for over 1500Km TAL straddles across two countries–<strong>India</strong> andNepal and includes 14 Protected Areas (PAs). TheTerai Arc Landscape includes high density tigerareas and is a priority landscape in the <strong>WWF</strong> TigerAction Plan. It is also a priority landscape for the<strong>WWF</strong> Asian Rhino and Elephant ActionStrategy.In <strong>India</strong>, TAL lies in three states <strong>of</strong>Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Itcomprises <strong>of</strong> 7 Protected Areas, mostly TigerReserves. The <strong>India</strong>n part <strong>of</strong> TAL, besides beingrich in its floral diversity, is also key habitat forfour globally threatened species <strong>of</strong> large mammals– the <strong>India</strong>n tiger, Asian elephant, thegreat one horned Rhino and swamp deer.Despite being endowed with rich assemblage <strong>of</strong>wildlife species, TAL faces serious conservationchallenges. On the one hand they threaten the tiger,elephant and other species <strong>of</strong> the region; on theother they also affect the local communities thatdirectly depend on the region’s natural resources.Conservation objectives in this highly populatedzone therefore need to be reinforced by creatingstakes for the local communities thereby reducinghuman-wildlife conflict while allowing sustainableuse <strong>of</strong> and access to natural resources. It is for thisreason that the TAL programme addresses socioeconomicconcerns <strong>of</strong> local people througheconomic opportunities, sustainable use <strong>of</strong> forestand land resources and benefit-sharing fromconservation. The programme includes workingwith the communities in areas such as education,health, alternative energy use, ecotourism,alternative agricultural practices, capacitybuilding, community forest management andmaintaining network with differentstakeholders.The landscape on <strong>India</strong>n side covers an area <strong>of</strong>approximately 49,500 sq km. Considering thesize <strong>of</strong> the landscape, existing capacity andavailable funds for the project, initially twopriority critical corridor complexes were selectedfor intervention. These are:A. Rajaji –Corbett- Ramnagar Forest Division(RFD)10

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong> : Confrontation to Co-existenceB. Chuka-Lagga Bagga-Kishanpur- DudhwaTiger ReserveEstablishing a field presenceThe field <strong>of</strong>fices in the TAL have been functionalfor sometime now and have firmlyestablished the programme’s presence in thefield. The difficulties faced during the initialstages <strong>of</strong> <strong>WWF</strong>’s move to the field have beenovercome and the functioning <strong>of</strong> the field <strong>of</strong>ficesis significantly improved. The capacity <strong>of</strong> theproject is now relatively well established as alsothe credibility <strong>of</strong> <strong>WWF</strong>. In the past four years,<strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> has been engaged in various activitiesranging from scientific studies, strengtheninganti-poaching to community- based interventions.While <strong>WWF</strong> interventions have beenable to check the degradation <strong>of</strong> the forest andcounter some <strong>of</strong> the negative factors faced by thewildlife, it is apparent that it will take several years<strong>of</strong> focused interventions to completely arrest thedownward slide and pave the way for a fullrecovery.A field <strong>of</strong>fice <strong>of</strong> <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> was established atPilibhit in January 2003. <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>’s field<strong>of</strong>fice at Ramnagar started in year 2004 and thisteam has been working in the corridor adjoiningthe Corbett Tiger Reserve (CTR), RFD andTerai West Forest Division. Lansdowne, TeraiCentral, Haldwani and Terai East Divisions.11

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong>The project implementation work at present isbeing carried out in two <strong>of</strong> the priority andfunctional linkages <strong>of</strong> Amdanda-Kunkhetcorridor between CTR and RFD and Kotdwar-Duggada corridor between Rajaji National Parkand CTR. The selection <strong>of</strong> these sites was basedon stakeholder consultations and a study carriedout by the project staff. It was established thatvarious passages for animal movement betweenCTR, RFD and Rajaji-CTR had been restricteddue to human settlements. To prevent furtherchoking in this corridor, an urgent need was feltfor conservation initiatives.The Pilibhit field <strong>of</strong>fice under the TALprogramme is looking after and coordinatingconservation work in the Chuka – Lagga Bagga– Kishanpur and Kishanpur – Dudwa –Katerniaghat linkages that extend from Pilibhit,Lakhimpur Kheri and Baharaich districts. Thetotal forest area <strong>of</strong> the linkage forests is approximately3000 square km as against the total20000 square km geographical area <strong>of</strong> the threedistricts. There are three protected areas -Dudwa National Park (DNP), KishanpurWildlife Sanctuary, Katerniaghat WildlifeSanctuary (KWS) and three territorial divisionsi.e. Pilibhit Forest Division (PFD), North Kheri(NKFD) and South Kheri Forest Division(SKFD).The PFD extends from Chuka to Lagga Bagga,Kishanpur and South Kheri Forests. The forestsare contiguous with Shuklaphanta Wildlife Reserveat Lagga Bagga area <strong>of</strong> PFD. The forests <strong>of</strong> KWSalso adjoin Shuklaphanta Reserve. Rhino,elephants and other ungulates are seasonalmigrants to Lagga Bagga area and KWS fromShuklaphanta and Bardia National Park. RiverSharda is the major catchment <strong>of</strong> the area. Anumber <strong>of</strong> tributaries drain into river Shardawhich ultimately forms the catchment <strong>of</strong> riverGanges.Analysis <strong>of</strong> the earlier eco-developmentinitiativesField surveys were conducted in the area toassess eco-development initiatives undertaken bydifferent government and non-governmentalorganizations working in the area for livelihoodgeneration. Information was collected fromvarious Government Departments, micro-plansprepared by the Forest Department and ForestDevelopment Agency (FDA). It was found thatan eco-development committee was formed inmany villages and the activities were undertakenthrough village level institutions.An assessment <strong>of</strong> earlier initiatives revealed thestrengths and weakness <strong>of</strong> the eco-developmentinitiatives. Special care was taken while initiatingthe livelihood activities. Baseline informationwas collected and prioritization <strong>of</strong> activitieswas done in consultation with the local communities.Only activities which were acceptableand had the sense <strong>of</strong> ownership with the localcommunities are planned and taken up. Transparencyand constant dialogue with the localstakeholders is always maintained and needbasedactivities are initiated by providing microcredits to individual beneficiaries with a reciprocalcommitment for conserving their environment.Conservation education and awarenessIn order to motivate and steer people towardsconservation efforts, several meetings wereSharing information: empowering villagers12

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong> : Confrontation to Co-existenceorganized with the villagers.Educational awareness programmes wereorganized through puppet shows and villagerswere made aware <strong>of</strong> the benefits <strong>of</strong> conservingforest resources, preventing forest fires and theimportance <strong>of</strong> wild animals and natural resourcesin their area. Special awarenessprogrammes are organized at the World EnvironmentDay, Wildlife Week (1-7 October) incollaboration with the Forest department andlocal NGOs.The awareness programmes served as a platformfor participation <strong>of</strong> various partners in conservation.The huge participation <strong>of</strong> the villagers,school children and local NGOs enumerates thesuccess <strong>of</strong> such programmes. The message <strong>of</strong>wildlife conservation was effectively disseminatedby these different events. The forestdepartment, the local NGOs and the peoplewere brought on a common platform for wildlifeconservation and local communities’ sustenancethrough various activities.In return the villagers extended their support infighting forest fires and protection <strong>of</strong> wildlife.The cases <strong>of</strong> human-wildlife conflict werereported from areas where the interim reliefscheme is not presently implemented and resentmenttowards the mechanism <strong>of</strong> the governmentrunscheme was observed.Assessment <strong>of</strong> existing institutionsSamiti- were assessed for their capacity to workfor conservation. One important finding wasthat the Panchayat in the villages were notaware enough <strong>of</strong> the importance <strong>of</strong> conservationand had different priorities. The involvement <strong>of</strong>the Block Development Agency required a lot<strong>of</strong> effort as their presence on the ground wasminimal.The activity has helped in identifying strengthsand specializations <strong>of</strong> local NGOs which play arole in implementation <strong>of</strong> the TAL programme.For example, the TWCS is ably conductingawareness campaigns within the village withhuge participation <strong>of</strong> villagers, student, andteachers. The major strength <strong>of</strong> KWS lies in itsleadership abilities and is effectively spreadingthe message <strong>of</strong> conservation among the villagers.PVSS is looking after the alternative livelihoodoptions for the people living in the corridor. Itfocuses on workshops which provide trainingwomen in knitting and sewing. TCF has beenthe partner <strong>of</strong> <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> in implementinginterim relief scheme to mitigate humanwildlifeconflict in TAL.These local organizations have been tapped andare being strengthened through proper trainingand guidance to enhance their strengths. ManyDifferent village-level institutions including GramPanchayat, Eco-development Committees andVillage-development Committees, Block andseveral NGOs were assessed for functioning andproper implementation <strong>of</strong> conflict-mitigationschemes. The strengths and weakness <strong>of</strong> localNGOs, namely, The Corbett Foundation (TCF),Rainbow Friends for Nature and Environment andSwarnim Social Welfare Samiti, KaterniaghatWelfare Society (KWS), Turquoise Wildlife ConservationSociety (TWCS), Parkiti Vanyajeev SamajSudhar Sansthan (PVSSS), Terai Arc ConservationSociety (TACS) and Corbett Gram Vikaas13

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong><strong>of</strong> the local organization are roped in especiallyfor awareness and community-related workTraining sessions were conducted for the localNGOs which are now working in close associationwith the TAL Pilibhit field <strong>of</strong>fice. A threeday training programme was organized by thePilhibit field <strong>of</strong>fice where all the local levelNGOs (TWCS, KWS, TNCS and PVSS)working with field <strong>of</strong>fice participated, andtraining was given on conducting studies oncrop damage by wild ungulates, estimation <strong>of</strong>fuelwood extraction from the forest, and assessment<strong>of</strong> grazing by livestock. This programmewas followed by another training camp foranalyzing raw data obtained from the study.Socio-economic and ecological studiesA study was conducted to assess fuelwoodcollection in Pilibit FD and CTR. Four ranges<strong>of</strong> Pilibit Forest Division (PFD) namely Mah<strong>of</strong>,Mala, Barahi and Haripur, and two ranges inKWS (Katerniaghat range and Nishangararange).Based on a well established methods, each <strong>of</strong> theranges areas were prioritized as High Pressure Area(HPA), Medium Pressure Area (MPA) and LowPressure Area (LPA) depending on the intensity <strong>of</strong>fuelwood collection in headloads and cycle loads byconsulting with the Forest Department and thelocal people. It was estimated that respectiveweights <strong>of</strong> headloads and cycle loads are 18–22 kgand 60–80 kg.Villagers making compost heap at Kunkhet and Carpetweaving training at ChukumThe above study showed that maximum collection<strong>of</strong> fuelwood in PFD took place in Mah<strong>of</strong>range followed by Haripur range, Barahi rangeand Mala range.About 50% <strong>of</strong> the people carrying head loadswere doing so for their domestic use. Thebicycles carried fuelwood to the local markets <strong>of</strong>Pilibhit, Nueria, Madhotanda, Sherpur Kalanand the Purnpur. In KWS, maximum fuelwoodcollection took place in Nishangara rangefollowed by Katerniaghat range.The above study not only quantified the amount<strong>of</strong> fuelwood collected from the forest in PFD andKWS, it also identified village-wise pressure fromfuelwood collection. This has helped to specifymanagement intervention to reduce the pressure<strong>of</strong> fuelwood collection in the forest. Variousactivities based on the findings <strong>of</strong> the study havebeen designed and a dialogue with the local authoritiesand communities to reduce the fuelwoodpressure has been initiated. The study has helpedthe Forest department to take effective actionagainst illegal collectors.In six villages around Corbett Tiger Reserve, it wasfound that frequency <strong>of</strong> visits made to the forest ismore during winter season and reduces in rainyseason. Winter forms the peak season <strong>of</strong> fuelwoodcollection as most <strong>of</strong> the families collect fuelwoodin advance for rainy season and hot summermonths ahead. One head load (approx. 25 Kg) canbe finished in less than one day to almost threedays depending on the family size. Approximately5,835 Kg per day fuelwood is extracted from thestudy, area and out <strong>of</strong> seven entry points selectedfor the study, the maximum biotic pressure wasidentified at Dhapla gate, which leads to ChotiHaldwani township.Survey for baseline informationA socio-economic survey was conducted by theTAL Pilibhit field <strong>of</strong>fice in 22 villages adjacentto Chuka-Lagga Bagga-Kishanpur linkage inorder to establish baseline information onstructure, demography, landholding, education,14

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong> : Confrontation to Co-existenceannual income, cattle, resource-dependency andcrop depredation. A similar study was conductedin Ramnagar and Kotdwar sectors. The studywas mainly focused on villages falling on criticalcorridors: Amdanda-Kumeriya corridor,Bailparow-Kotabagh corridor, Boar river corridorand Nihal corridor.Based on the information <strong>of</strong> the above surveyssome specific activities were undertaken by theTAL-Pilibhit <strong>of</strong>fice and TAL-Ramnagar field<strong>of</strong>fice.Some <strong>of</strong> these are highlighted below :In order to reduce pressure <strong>of</strong> fuelwood, LPG(Liquified Petroleum Gas) connections weredistributed to the villagers. An economicassessment was done to find out the purchasingcapacity <strong>of</strong> the villagers to purchase LPG. LPGconnection was given after taking 50% contributionfrom the villagers. This contributiondevelops a sense <strong>of</strong> ownership and responsibilityamong the villagers while making it economicalfor the project. About 90 families in Naujaliyavillage, 50 families in Gaba Sarai village and 56families in Ramnagra village have been providedwith LPG connections. This has obviouslyresulted in a large reduction in fuelwood requirementby the local people.In order to find out how many people wereactually using LPG an assessment was carriedout in the critical sites. Ninety seven percent <strong>of</strong>the respondents to whom this facility wasprovided responded that there was reduction <strong>of</strong>fuelwood consumption, which had dropped 20 –30% according to their estimates. It was alsoestimated that 20% <strong>of</strong> the beneficiaries wererefilling the cylinder before one month whereas20% every month, and 34% every two months. So74% <strong>of</strong> the beneficiaries were refilling thecylinder within two months. The remaningpeople refill cylinder between two and sixmonths. The delay in refilling is also caused dueto non availability <strong>of</strong> LPG. This can then becalculated as a reduction <strong>of</strong> 10 tons <strong>of</strong> fuelwoodused per year. The villagers are now accustomedto the use <strong>of</strong> this method. This successful modelcan be replicated in other villages.Institution buildingAs mentioned earlier, <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> through itsTAL programme has been working inRamnagar sector now for the last three years.Initially Kunkhet village in Amdanda-Kumeriyacorridor was identified for intervention andgradually the work was extended to othervillages (Mohan & Chukum) lying on the samecorridor. During second year <strong>of</strong> the programmevillages Choti-Haldwani near Baur corridor andMankanthpur lying on Kotabagh-Belpraow corridorwere selected after assessing the importance <strong>of</strong>Awareness activity with school childrenUnderstanding the dynamics <strong>of</strong> human-wildlife conflict : A programmeduring Wildlife Week, October 200515

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong>the surrounding forests for elephant movement.Baseline information on these villages werecollected and compiled and through variousPRA (Participatory Rural Appraisal) tools theexisting institutions in the villages were analyzed.After assessing the potential <strong>of</strong> formation<strong>of</strong> new institutions and working with theexisting institutions steps were taken to identifytarget groups and bring them on one platform.Initially, a village level institution was formedin Kunkhet village with a person from eachhouse hold as its member. An initial grant wasgiven to the institution for creation <strong>of</strong> a communityasset. This model didn’t work and collapsedsoon after due to social and politicalissues. Learning from the experience the strategywas changed and instead <strong>of</strong> forming singlemacro institution small homogeneous self-helpgroups were established.These self help groups were provided inputs interms <strong>of</strong> facilitation, training and linkages to makethem self sustainable. The groups at Kunkhetvillage were supported for activities like stitchingand selling litter bags to the Dhangarhi gate <strong>of</strong>CTR, and poultry. SHGs <strong>of</strong> Mohan village werelinked with <strong>India</strong>n Medical Pharmaceutical CorporationLimited (IMPCL) for employmentopportunities. Similarly, the groups at Choti-Haldwani were supported for Tie and Dye;packaging <strong>of</strong> locally grown pulses and spices andpoultry. For promoting organic farming andwomen SHG at village Mankanthpur, TAL-Ramnagar promoted Durga SHG and theassociated groups as trainer organizations.Mitigation <strong>of</strong> Human-Wildlife ConflictCrop damageIn the Ramnagar corridor complex, Mohancluster <strong>of</strong> villages and Githala were selected for asystematic assessment, on the basis <strong>of</strong> potentialand priority linkages preferred by wild animals,especially elephants. The villages in Mohancluster are Mohan, Amarpur, Chuklam andKunkhet where there is high incidence <strong>of</strong>human wildlife conflict and high dependency onforest for fuel, fodder and other Non TimberForest Produce (NTFP) leading to greateranthropogenic pressure on key wildlife habitat.Detailed demographic and socio-economic datawere collected in the above villages. The data onresource dependence were collected throughhousehold survey, Focused Group Discussionand Participatory Rural Appraisal with thevillagers. Field visits were undertaken to carryout meetings and informal exchanges with thecommunity members and leaders. Individualinterview were conducted to gather informationon awareness level, health status and skills <strong>of</strong>community members and to understand existinglivelihood options in the villages. Animalmovement was recorded through directsightings, data collection by transect methodand through secondary information.The assessment helped in recording the number<strong>of</strong> cases <strong>of</strong> cattle kills, crop raiding in terms <strong>of</strong>scale and seasonality in the villages. Informationwas also gathered on the socio-economic condition<strong>of</strong> the villagers, fodder and fuelwooddependency <strong>of</strong> the villagers and other problemsfaced by the people. An important finding <strong>of</strong> thisassessment was that cattle kills were moreMeeting with hunter-gatherer community16

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong> : Confrontation to Co-existencefrequent in the rainy season; crop raiding due toelephants, wild boar and spotted deer took placein the cropping seasons during the months <strong>of</strong>August–September and December to March.Necessary interventions have to be plannedaccordingly.In the Pilibhit corrridor complex, a study wasconducted to assess crop loss due to wild animalsin four ranges <strong>of</strong> Pilibhit Forest Division(Mah<strong>of</strong>, Mala, Barahi and Haripur), two rangesin KWS (Katerniaghat range and Nishangararange), four ranges <strong>of</strong> Dudwa Tiger Reserve(Belreiyan, Sathiana, Kishanpur and Mailaniranges), four ranges <strong>of</strong> NKFD (North Nighasanrange, South Nighasan range, Majgahi range andSampurna Nagar range), and two ranges <strong>of</strong>SKFD (Bhira and Mailani ranges). The studywas conducted in the winter season.In each range, areas were categorized as HighPressure Area, Medium Pressure Area and LowPressure Area depending on the infestation <strong>of</strong>wild animals to crops by consulting with theforest department and local people.The assessments showed that the crops loss wasmore in six villages <strong>of</strong> the PFD. Meetings wereheld in the villages <strong>of</strong> high pressure- area andpeople were consulted on the situation and theeffectiveness <strong>of</strong> various mitigatory measures.Villagers identified electric fencing as an effectivemeasure for crop protection for which theyneeded support from government and nongovernmentorganizations/agencies and inreturn pledged to protect wildlife. Based on theassessments Kesarpur – Basantapur Nauner–Barahi cluster <strong>of</strong> 9.15 km. and Githala wereselected for erecting fences. This initiative gottremendous support from the villagers andhelped to mitigate human-wildlife conflict. Themovement <strong>of</strong> elephant, spotted deer and bluebull into farms has been stopped by the fence.Even though electric fences have been erectedby <strong>WWF</strong>- <strong>India</strong> in other parts <strong>of</strong> the country,these are cases where the villagers contributedboth financially and in-kind for erecting theelectric fence. The Kesarpur-Barahe length <strong>of</strong>solar fence is unique as this is an example <strong>of</strong> thelongest working solar fence in <strong>India</strong> beingmaintained by the local community.Loss <strong>of</strong> Human Lives and LivestockThe loss <strong>of</strong> lives in the villages was assessedwith information collected from secondarysources followed by spot verification in some <strong>of</strong>the incidences. The incidence <strong>of</strong> tiger andelephant attacks in these areas is not a new one.A study in 2001 reported that 90 persons losttheir lives from March 1978 to December 1981in Kheri district whereas three persons werekilled in Pilibhit.In PFD after a gap <strong>of</strong> almost 23 years, the tigerkilled 10 people from December 2001 to March2004. All the 10 kills happened during fuelwoodcollection or thatch grass cutting by the people.The assessment <strong>of</strong> human wildlife conflict revealedthat if prompt actions are taken to reduce grievances<strong>of</strong> the local communities a retaliatorysituation can be avoided. An ex-gratia payment wasprovided to the affected family immediately. As aresult, despite 33 human casualties (till June 2006)there was no retaliatory killing <strong>of</strong> the animal.Electric fencing as protection17

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong>The human killing sites were immediatelyvisited by the Forest Department and <strong>WWF</strong>staff after the incidents. Details <strong>of</strong> the killingsite, habitat type and indirect signs <strong>of</strong> theanimal were studied. In all the cases the issueswere discussed between the forest <strong>of</strong>ficials, thevictims’ families and local communities. Sometimessuch incidences created resentment andanger among the villagers.Tiger and elephant attacks on humans haveoccurred since humans and wildlife lived side byside, one <strong>of</strong>ten straying into the other’s territory.While payment <strong>of</strong> small sums <strong>of</strong> moneyeases some tension in the aftermath <strong>of</strong> an attack, itwas found that efforts should be instituted toregulate the movement <strong>of</strong> people into the forestsfor thatch and fuelwood collection. Alternativesources <strong>of</strong> such resources or other livelihoodoptions could help reduce incidents <strong>of</strong> suchconflict.Assessment <strong>of</strong> effectiveness <strong>of</strong> existingcompensation schemes<strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> under its Tiger ConservationProgramme initiated small interim financialassistance to the owner <strong>of</strong> the cattle killed by tigeror leopard in the buffer zone <strong>of</strong> Corbett TigerReserve (CTR) in 1998 which is still beingcarried out and continued under the TALProgramme. The Cattle Compensation Schemewas started with the objective <strong>of</strong> reducinghuman–wildlife confrontation. The scheme nowknown as Interim Relief Scheme is runningsuccessfully in partnership with The CorbettFoundation, a local NGO and has proved to besuccessful in eliminating retaliatory killing <strong>of</strong> bigcats.In the mid 90s, cases <strong>of</strong> villagers resorting torevenge killing <strong>of</strong> the tiger by poisoning <strong>of</strong> cattlecarcasses came to light. After the implementation<strong>of</strong> Interim Relief Scheme by <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>,there has been no cases <strong>of</strong> tiger being killed inretaliation ssreported in last few years.Field inspection <strong>of</strong> cattle killed by big catInformation was collected on the number <strong>of</strong>incidences, during 2004-06 cattle lifting tigerwithin the area <strong>of</strong> Dudwa Tiger Reserve.Secondary information was collected from the<strong>of</strong>fice <strong>of</strong> the Deputy Director, Dudwa TigerReserve. The number <strong>of</strong> incidences filed in the<strong>of</strong>fice was taken as the source. Within this timeperiod a total <strong>of</strong> 24 incidents <strong>of</strong> cattle-lifting havebeen filed. The above figure shows that thenumber <strong>of</strong> cattle killed by the tiger per year is verylow in this area. Still, the forest <strong>of</strong>ficials have askedto continue the schemes by the TAL <strong>of</strong>fice becausethere are delays in payments <strong>of</strong> compensation bythe park authorities due to lengthy procedures.In contrast, human killing by tigers is relativelyhigh in this sector <strong>of</strong> the landscape. Ex-gratiapayment for human killing by wild animals wasA new batch <strong>of</strong> police personnel trained in wildlifeprotection matters18

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong> : Confrontation to Co-existencecarried out by the TAL Pilibhit field <strong>of</strong>fice.Payments <strong>of</strong> Rs.5000 each were made to theaffected families after a joint inspection by theTAL <strong>of</strong>fice and the Forest Department within24 hours <strong>of</strong> the incident. From November 2003to June 2006, 33 cases <strong>of</strong> human killings wereobserved in PFD, DTR and NKFD. Ex-gratiapayments were made in all cases. This has beenuseful in preventing retaliatory killing <strong>of</strong> tigersby angry villagers.The existing interim relief scheme and the exgratiascheme were found to be beneficial forreducing human - wildlife conflict. The antagonismamong the villagers due to human killingsby tiger or leopard was largely controlled due topromptness <strong>of</strong> the ex-gratia scheme conducted bythe TAL <strong>of</strong>fice. This is reflected in the absence<strong>of</strong> retaliatory killing <strong>of</strong> wild animals by thevillagers despite 33 people getting killed in theyears 2003 to 2006.It is expected that both Forest Department and<strong>WWF</strong> <strong>India</strong> should join hands to compensatethe victims, which will increase the coverage <strong>of</strong>compensation for the victim. It was found thatunless a better mechanism or a trust fund couldbe established, the present scheme was the bestoption available.Trans-boundary conservationborder to poach or smuggle wildlife/timber andescape across the border as it is easier for themto cross the border than the enforcementgovernment agencies due to government proceduresfor crossing international boundaries.Siltation <strong>of</strong> rivers downstream in <strong>India</strong> is largelydue to the denudation <strong>of</strong> the hills upstreamacross the border. A huge area <strong>of</strong> sal forest driedand changed into syzygium forest and primeareas <strong>of</strong> Sathaina grasslands were replaced bycoarse unpalatable grasses. In order to mitigatethis conflict both the national governments aretrying to find solutions through periodic transboundarymeetings. Through the TALProgramme some remedial measures have beentaken but much has to be done at a preventivelevel to address the root cause <strong>of</strong> conflict.Field level trans-boundary meetings were held:one from 1-3 July 2004 at Lagga Bagga andanother one on 18 April 2005 at Dodhara wherethe above issues were discussed both by <strong>India</strong>nand Nepali <strong>of</strong>ficials. A field level meeting washeld on 28 April, 2006 at Rampurva FRH,Nishangaraha Range, Katerniaghat WLS inApril 2006. In the meetings, the DFOKaterniaghat and Assistant Forest Officer KhataNepal with several community members, Anti-The trans-boundary conservation issue gainssignificance in TAL as it is spread across different<strong>India</strong>n states and two countries.The Chuka-Lagga Bagga–Kishanur and theKishanpur–Dudwa-Katerniaghat Linkage forestsare contiguous with the Indo-Nepal border allalong from Lagga Bagga, Tatrganj, Basahi,Kaima Gauri, Gauriphanta, Belapersua andKaterniaghat areas.The documentation process <strong>of</strong> trans-boundaryconflict revealed that the grazing pressure wasboth inward and outward as the cattle movedfreely across the borders from either side. Withregard to poaching and illicit felling, it wasfound that poachers and smugglers cross theParticipants at a transborder workshop19

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong>Seizures due to information network developed by TAL (Ramnagar <strong>of</strong>fice)S.No Year Seizure Number <strong>of</strong> ForestArrest Division1 2004 Tiger Skin-1 3 Terai West2 Leopard Skin-2 1 Terai WestPython-1Sambar Antler-1Tortoise bones3 2004 Meat <strong>of</strong> Hog deer 2 Terai West4 2004 Elephant Tusk-28Kg 2 CTR5 2005 Common Coots 2 Terai West6 2005 Medicinal plants (worth 2 lac) 7 Ramnagar7 2006 Leopard skin 1 Terai West8 2006 Timber 4 Terai West9 2006 Leopard skin-1Anteler 2 Terai WestOther Seizures (Pillibhit sector)Sl No. Date Seizures Location1 18.2.05 17-18 kg <strong>of</strong> tiger bone Bichhia Raliway Station, KWS2 19.2.05 One tiger skin seized Bichhia Raliway Station, KWS3 13.9.04 Swamp deer poaching Chandia Hazara village <strong>of</strong> HaripurRange <strong>of</strong> PFD4 10.8.04 Wild boar poaching PFDSl No. Date Seizures Location1 23-07-2005 3.7 (kg)Tiger Bone Gabia Sahrai Pilibhit2 12-10-2005 3 Leopard, 1Tiger Skin Sampurnagar, Lakhimpur Kheri3 27-11-2005 1 Leopard Skin Gauriphanta, Lakhimpur kheri4 08-06-2006 8 Kg. Tiger Bones Nurea Railway Station, Pilibhit5 15-06-2006 1 Tiger and 1Lleopard Skin Tulsipur, Balrampur6 10-07-2006 5 Otter Skins Ramnagra, Pilibhitpoaching Unit and village devolvement committeemembers were present. The locals NGOscommunity members and anti-poaching unit <strong>of</strong>both the countries agreed to share informationand cooperate in trans-boundary wildlife conservation.A series <strong>of</strong> meetings were held with forest<strong>of</strong>ficials <strong>of</strong> Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh. Asa result a mechanism for developing informernetwork and sharing information was develop.Bijnore Forest Division has taken up jointpatrolling with CTR. Bijnore FD is on theboundary <strong>of</strong> the states <strong>of</strong> Uttar Pradesh andUttarakhand.The Lansdowne Forest Division is a criticalforest area due to the several other forest divi-20

<strong>Landscapes</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hope</strong> : Confrontation to Co-existencesions bordering it. Kalagarh Forest Division istowards the east and south eastern boundary,Bijnaur Forest division is towards the southernboundary and Rajaji National Park towards thewest. The bordering with several divisions andtwo important protected areas leads to frequentmovement <strong>of</strong> wild animals through this division.The movement <strong>of</strong> wild animals in andacross the division makes this division sensitiveto poaching and wild life killing. Due to thesensitivity <strong>of</strong> the area, Forest Department and<strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>’s TAL programme decided toconduct monthly joint surveys in the villagesbordering Lansdowne division with Kalagarhand Bijnaur divisions. The team for the jointpatrolling included the DFO, Lansdowne FD,<strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> TAL team and forest departmentsfield staff. During the joint patrolling exercise atemporary gujjar dera (camp) was found inDabina beat <strong>of</strong> Duggada range. The gujjars wereinvestigated and were asked to vacate the areaimmediately.Uttarakhand state borders both Tibet andNepal: this is the main trade route for wild lifeproducts. Due to the sensitivity <strong>of</strong> the area,<strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong> TAL Programme initiated theformation <strong>of</strong> an informer network. In the pastthree years cases <strong>of</strong> poaching and trade havebeen exposed with the help <strong>of</strong> the informernetwork developed by <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>.Support to forest departmentforests from the villages within the country andalso across the border, from Nepal. To strengthenthe Forest Department’s infrastructure incommunication, mobility and law enforcement,infrastructure support has been provided to thedifferent FD divisions <strong>of</strong> the linkage forests forbetter wildlife protection work. The NorthKheri and South Kheri Forest Divisions arebeing provided with infrastructure support forthe first time under the Terai Arc LandscapeProject.Wildlife survey training for field-level staff <strong>of</strong>Katerniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary was givenunder this activity. The field staff were trainedto collect information and analyze data onungulate censuses. Similar training programmesfor ungulate and tiger census were also given inthe Pilibhit Forest Division. Thrust is given oninformation collection and analysis. A trainingprogramme was also conducted on wildlifehealth and diseases with the help <strong>of</strong> localveterinarians in the area.Legal training workshops were organized for thefield staff <strong>of</strong> the Forest Department such as the.Ramnagar Forest Division and LansdowneForest Divisions in year 2004 and 2005 respectively.After seeing the positive outputs <strong>of</strong> theselegal training by <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>, Forest Departmentwanted to hold such training programmesAn informer network <strong>of</strong> the Forest Departmentwas supported and strengthened in the linkageforest areas i.e. Pilibhit, Dudwa National Park,Kishanpur Wildlife Sanctuary and KaterniaghatWildlife Sanctuary. Pilibit field <strong>of</strong>fice played akey role by providing financial support to thisinformer network. With enhanced support andcapacity this network produced major resultsthereafter.The Chuka-Lagga Bagga-Kishanpur and Kishanpurlinkages are the two critical corridors for wildlifeconservation <strong>of</strong> the area. The linkage forests aremostly along the international border i.e. theIndo-Nepal border. There is pressure on theseA watch tower constructed with <strong>WWF</strong>-<strong>India</strong>’s support21