Aerie InternationaL - Missoula County Public Schools

Aerie InternationaL - Missoula County Public Schools

Aerie InternationaL - Missoula County Public Schools

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Aerie</strong> <strong>InternationaL</strong><br />

Volume 2 2009

<strong>Aerie</strong> International<br />

a literary arts magazine edited<br />

by young writers and artists<br />

for young writers and artists

aer♦ie(âr’ē) noun, 1. The<br />

lofty nest of an eagle or other<br />

predatory bird, built on a cliff<br />

ledge, mountaintop, or high in<br />

a dead snag. 2. An elevated,<br />

often secluded, dwelling,<br />

structure, or position. 3. A<br />

home for exceptional young<br />

writers and artists from around<br />

the globe, providing publishing<br />

opportunities, literary prizes,<br />

and cross-cultural connections.<br />

4. A place where the<br />

distinctions and connections<br />

of culture, language, peoples,<br />

and environment are nurtured.<br />

5. An innovative new journal<br />

edited and published by high<br />

school students for high school<br />

students.

AdvISory boArd<br />

eric abbot<br />

sandra alcosser<br />

coleman barks<br />

dana boussard<br />

david cates<br />

david james duncan<br />

contact us at aerieinternational@gmail.com<br />

www.aerieinternational.com<br />

We InvIte SubmISSIonS of<br />

innovative poetry<br />

short stories and flash fiction<br />

brief non-fiction<br />

lyrical essays<br />

short drama<br />

foreign language poetry and translations<br />

visual art and photography<br />

CongrAtulAtIonS 2009 AWArd WInnerS<br />

rIChArd hugo Poetry AWArd<br />

wynne hungerford, greenville, south carolina<br />

JAmeS WelCh fICtIon AWArd<br />

alexandria kim, allendale, new jersey<br />

normAn mACleAn nonfICtIon AWArd<br />

emma lucy bay pimentel, jacksonville, florida<br />

rudy AutIo vISuAl ArtS AWArd<br />

austin j. noll, lawrence, kansas<br />

lee nye PhotogrAPhy AWArd<br />

iida lehtinen, suavo, finland<br />

debra magpie earling<br />

carolyn forché<br />

tami haaland<br />

ilya kaminsky<br />

robert lee<br />

naomi shihab nye<br />

caroline patterson<br />

prageeta sharma<br />

m.l. smoker<br />

robert stubblefield<br />

renée taaffe<br />

r. david wilson

edItorIAl boArd 2009<br />

edItor<br />

katie degrandpre<br />

Poetry edItor<br />

kiley munsey<br />

ProSe edItor<br />

jenny godwin<br />

Art And PhotogrAPhy edItor<br />

hannah halland<br />

CorreSPondenCe edItor<br />

caitlyn brendal<br />

WebSIte edItor<br />

ryan casas<br />

hIStorIAn<br />

hanley caras<br />

mAnAgIng edItor<br />

alissa tucker<br />

ASSt. Poetry edItor<br />

dove ashby<br />

ASSt. ProSe edItor<br />

caitlyn brendal<br />

dIgItAl edItor<br />

lori krause<br />

SubSCrIPtIonS edItor<br />

dove Ashby<br />

ASSt. WebSIte edItor<br />

tessa nobles<br />

AdvISor<br />

lorilee evans-lynn<br />

<strong>Aerie</strong> International is published annually by the students of Big Sky High School in<br />

<strong>Missoula</strong>, Montana. Subscriptions are $12 to U.S. subscribers, $15 to friends outside<br />

the U.S. Sample copies are $5. Subscription forms can be found at the back of the<br />

magazine. Exchange subscriptions are encouraged. <strong>Aerie</strong> International is supported<br />

by Big Sky High School, private contributions, and sales of its magazine. <strong>Aerie</strong> International<br />

accepts poetry, fiction, nonfiction, art and photography submissions from<br />

September 1st through February 1st. All work is submitted electronically. Potential<br />

contributors should send no more than five pieces. For full submissions guidelines<br />

and all other correspondence, visit our website or inquire through email.<br />

aerie.international@gmail.com<br />

www.aerieinternational.com<br />

© 2009 <strong>Aerie</strong> International<br />

Rights revert to the author upon publication.<br />

Printed on recycled paper with recyclable ink at Gateway Printing

friends of<br />

<strong>Aerie</strong> International<br />

the following individuals and organizations have made it<br />

possible for the <strong>Aerie</strong> literary magazines to continue and grow.<br />

Thank you!<br />

SPonSorS<br />

Anonymous Donors<br />

Paul Johnson, Big Sky High School<br />

Mike Peissig and Donna Elliott, Gateway Printing<br />

PAtronS<br />

Coffee Cart, Big Sky High School<br />

Dudley Dana, The Dana Gallery<br />

Gerald Fetz and Family John Lynn<br />

Scott and Mary Meacham, Montana Claims Service<br />

Laura Parvey-Connors, Loose Leash Marketing<br />

Renée Taaffe, <strong>Missoula</strong> Art Museum<br />

donorS<br />

Nancy Aitken-Nobles and Buddy Nobles<br />

Lela Autio Phillip and Melodee Belangie Judy Bullis<br />

Clayton Devoe, Hellgate Elks Lodge<br />

Dr. Brian Diggs J. Robert and Dorothy Evans<br />

Paul and Susan Fredericks, Mineral Logic<br />

Bridget Johnson and Henry Ward Nina Johnson<br />

Dr. Mary Kleschen and Thomas Michels Robert Lee<br />

Mike and Ann Munsey Dr. Charles and Kathy Swannack<br />

SuPPorterS<br />

Butterfly Herbs<br />

Dr. Ken Fremont-Smith and Dr. Barbara Wright<br />

Robin Hamilton and Peggy Patrick, The Shack<br />

Steve, Sue and Jim Ledger Candice Mancini<br />

Partners in Home Care Frank and Beverley Sherman<br />

Linda Rayfield Barbara Theroux, Fact and Fiction<br />

Byron Weber Hans and Barb Zuuring<br />

Thank you for your support!<br />

Sponsors $1,000 +<br />

Patrons $500-999<br />

Donors $100-499<br />

Supporters $50-99<br />

Parents, Past & Present: Priceless

Highest Award 2008 National Council of Teachers of English<br />

Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines<br />

Dear Reader,<br />

It seems we have tried to define our mission thousands of times. This<br />

magazine just doesn’t seem to fit in any one category.<br />

For me, <strong>Aerie</strong> International’s meaning changes on a day to day basis. Some<br />

days, it is an object floating up in the clouds somewhere. I know it’s<br />

important, but I can only catch glimpses of it. Some days it’s stacks of<br />

papers, overflowing filing cabinets, and massive digital files that are<br />

never quite organized. Everyday, however, when I walk in our classroom<br />

door, or open up our email, the world feels real again. I am reminded that<br />

there are other people, other lives, and other stories that exist outside<br />

my own immediate surroundings.<br />

I think the beauty of <strong>Aerie</strong> International as an organization with a mission<br />

and a literary magazine, is that it allows students around the world to<br />

share their experiences with others. That in itself is empowering in a<br />

world where it seems that no one is actually listening, despite the many<br />

new technologies which are supposed to help us communicate.<br />

If <strong>Aerie</strong> International were an annual summer camp, this year’s theme<br />

would be sharing stories. All we would ever do is sit around a campfire<br />

with hot chocolate and s’mores listening to each other’s thoughts,<br />

fictional and non-fictional. I believe my experience would be a great deal<br />

less had I never had the opportunity to hear the stories of people like<br />

Emma Pimentel, Romanius Eiman, Alexandria Kim and Jake Ross. Each<br />

submission I looked at and each bio I read made my world bigger as each<br />

person’s ideas, thoughts, and personalities came alive through his or her<br />

art. I feel truly privileged to have been able to work on this magazine.<br />

We have many hopes for the future. We hope to make <strong>Aerie</strong> International<br />

sustainable when elective classes are too often on the chopping block.<br />

We are always looking for new awards and new ways to give a voice to<br />

more students around the world. We also hope to honor the writers and<br />

artists who have come before us. We have learned so much from writers<br />

and artists such as Richard Hugo, Rudy Autio, Norman Maclean, James<br />

Welch and Lee Nye.<br />

We have many people to thank for helping make our dreams with <strong>Aerie</strong><br />

International possible. The first is our international Advisory Board<br />

whom we were fortunate enough to meet with this year. They are our<br />

ultimate support group, inside the classroom and out, who prove to<br />

us that what we are doing is real and good. We so appreciate their

feedback and support. Thank you to our design and print gurus, Laura<br />

Parvey-Connors with Loose Leash Marketing as well as Donna Elliott<br />

and Mike Peissig of Gateway Printing. We learn something every time<br />

we meet and our magazine truly depends on you. Our teacher, Lorilee<br />

Evans-Lynn, and all teachers around the world deserve a standing<br />

ovation followed by a day of rest and ultimate pampering. It is teachers<br />

like these who inspire us to do more, to dream, and to achieve. Thank<br />

you to Dudley Dana and the Dana Gallery for hosting our ridiculously<br />

complicated fund raiser and our Advisory Board members for supporting<br />

us through your readings and your presence. Thank you to Chelsea<br />

Rayfield, who was not only a teacher, but a big sister and a friend to<br />

us. A final thank you to our wonderful parents and Cathy Marshall, our<br />

ultimate <strong>Aerie</strong> Mamma, who comes in and feeds our cranky souls early<br />

on Sunday mornings. All our parents deserve trophies and a multitude of<br />

thanks.<br />

Finally, thank you readers for supporting us, believing in us, and hearing<br />

the stories of all these outstanding people.<br />

Katie DeGrandpre, Editor

To the Reader:<br />

As we neared production of this, our 2 nd issue of <strong>Aerie</strong> International, I<br />

couldn’t help but reflect on our aspirations for this magazine. One was to<br />

establish a legitimate journal for young people, a journal of writing and art<br />

that young people could claim as their own. We wanted it be one of beauty.<br />

We hoped to make connections, not only for our editors and the people we<br />

were fortunate enough to encounter on and off these pages, but also to offer<br />

the means for young people far outside our sphere to meet. Having pen pals<br />

is great, but what if we could give young people the opportunity to share<br />

their art in their own magazine?<br />

It is a usual day for me to enter the classroom and find Katie, our 2009<br />

Editor, sitting cross-legged on a table, reading from a manuscript or waving<br />

one in front of my face (I mean that literally), usually accompanied with the<br />

command: “Lorilee, this is AMAZING. You HAVE to read it.”<br />

She is usually right.<br />

That’s how I first came to hear, “Worker Bee,” a story about what might<br />

be described as a very conventional narrator and his obsession with an<br />

equally unconventional young “antagonist.” Jake Ross manages to take<br />

on environmental issues, high school, middle America, and its fringes.<br />

His characters are whimsical and delicious and irreverent, at once both<br />

fantastical and oddly real.<br />

In her memoir, “Navy Blue,” Emma Pimmental speaks of visiting a<br />

hippotherapy farm in Sudan for children from underfunded hospitals. These<br />

children have been abandoned by war, disease and poverty that is nearly<br />

incomprehensible outside the developing world. Emma walked to Jane-<br />

Ann’s farm twice a week all summer in the Sudanese heat and dust to help.<br />

“I learned more about love and humankind that summer than I ever have<br />

before or since,” Emma writes.<br />

I don’t know that I could have picked two pieces from the magazine less<br />

alike. And yet they are about what the entirety of this journal, all of art,<br />

perhaps, is about—coming to the center of a thing and laying it bare, first<br />

to discover it for oneself, and then, if we are very lucky, to share it. This<br />

magazine is full of those kinds of moments, in image and in word.<br />

Many pieces poke fun at our cultures and who we are. Annie Chang<br />

writes about growing up Asian-American in central Oklahoma, “where just<br />

five minutes from my home are real cattle farms and horse ranches.” She<br />

says she likes to laugh at herself, and in so doing, gives all of us permission<br />

to laugh, not only at her, but at ourselves as well. Her story is part memoir,<br />

part fiction, about shopping trips to Wal-Mart where her mother insists,<br />

over her daughter’s protestations, to buy soymilk for the family “primarily<br />

because Oprah Winfrey tells her to.” Her story is hilarious, a convergence of<br />

cultures and coupons.<br />

Whether visual art, photography or writing, the pieces are about longing<br />

and love, about society, about what we accept and what we do not. In<br />

“Killing Beauty,” photographer Gabriella Otero formally poses two young<br />

girls in party dresses in a field. They are focused like manikins on an<br />

electrical power station in the distance, their backs to the viewer. Austin

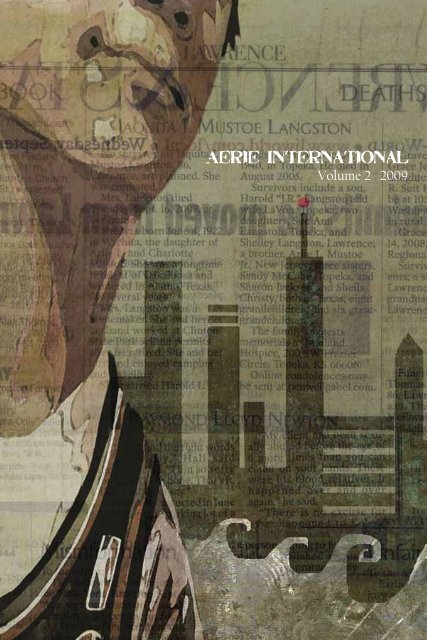

Noll, whose self-portrait wraps the cover of the 2009 <strong>Aerie</strong> International, has<br />

superimposed newspaper articles and obituaries across his very elongated<br />

frame, a cut out cityscape in the background and what might be paper<br />

waves rolling in the space between the city and the figure. The visual artists<br />

and photographers are doing the same thing the writers are, discovering and<br />

sharing their images and comments on the world.<br />

I wrote an article earlier this year about the effect of publishing on<br />

student writing. I asked my own students for their thoughts. Katie brought<br />

home the public nature of art and what it does for all of us: “Getting<br />

published is one of the most empowering things in the world. We all write<br />

secretly in journals at night about our lives and what’s happening, but when<br />

that writing gets published, you just know that someone else out there<br />

understands and believes in what you are feeling or saying or thinking.”<br />

In retrospect, perhaps it is that notion more than any other this journal<br />

hopes to offer. A place where art can explore and affirm who we are and<br />

who we hope to be. When we have the opportunity to share those things,<br />

how can the world grow anything but a little closer?<br />

We have many people to thank, people who have transformed this effort<br />

into helping build a literary and art community among far ranging youth.<br />

First, thank you to everyone in my immediate radius who picks up the<br />

pieces tumbling from my hands as deadlines and fund raisers and readings<br />

approach—that includes my family and friends and my teaching partners,<br />

all of whom are exceedingly generous with their assistance and their<br />

indulgence. Thank you, too, to the families who support the giving of our<br />

awards—we are proud to continue a tradition of such remarkable writers<br />

and artists. We can only hope to pass on some of what they have offered<br />

us. Thank you to our Advisory Board, which convened at school this spring<br />

for our first formal Advisory Board meeting. For the <strong>Aerie</strong> students, these<br />

writers and artists are rock stars. Not only were our editors honored to<br />

be meeting, but the board was incredibly supportive of what the students<br />

have accomplished and equally ready with fantastic ideas for the future.<br />

Thank you as well to all who have supported us financially. The reality is<br />

that money makes it possible to do this sometimes overwhelming, always<br />

inspiring work. Finally, thank you to everyone who has submitted and<br />

everyone who subscribes to <strong>Aerie</strong> International. It is critical that we support<br />

what we believe in with our time and our money. Poetry and art are not<br />

inherently lucrative endeavors. They exist because we deem them essential<br />

and because we support them. Give subscriptions for <strong>Aerie</strong> International to<br />

your nephews and nieces and grandparents. Encourage your high school<br />

and local libraries to subscribe. Pass the word. We want <strong>Aerie</strong> International<br />

not only to be about the students who are published, but about sharing the<br />

art and writing created by young people with as wide an audience as we can<br />

possibly reach. Help us make those connections.<br />

Thank you!<br />

Lorilee Evans-Lynn, Advisor

To the Reader,<br />

<strong>Aerie</strong> International is housed in <strong>Missoula</strong>’s Big Sky High School, across<br />

from and ironically contrasted to nearby Fort <strong>Missoula</strong> which served<br />

as a detention center for Italian nationals and Japanese-Americans held<br />

prisoner during World War II. <strong>Aerie</strong> International represents a peaceful<br />

and celebratory step in building relationships across international<br />

boundaries. It is visionary, communal, and brilliant.<br />

You should see the classroom where it happens. It’s a workroom with<br />

tables layered in images and writing that have come from the United<br />

States, England, Thailand, Turkmenistan, Russia, Japan, Namibia, and<br />

Finland. This is a place where students can sit together, seminar-style,<br />

to converse with each other, with board members, and supporters.<br />

Presiding over it all is their magical teacher, Lorilee Evans-Lynn, the<br />

originator of this vision, the elegant orchestrator, promoter, fund raiser,<br />

supporter, and the encouraging voice that allows <strong>Aerie</strong> International, and<br />

its sister journal, <strong>Aerie</strong> Big Sky, to move systematically from conception to<br />

print. It’s an honor to serve with the other advisory board members on<br />

this amazing journey that is <strong>Aerie</strong> International.<br />

Youth have frequently been leaders in peace efforts, and I believe <strong>Aerie</strong><br />

International contains elements important to a peaceful future. The<br />

editors have the good fortune of communicating with global youth,<br />

and the readers have the good fortune to encounter visual and written<br />

work from many continents. In each issue, <strong>Aerie</strong>’s expert editors conduct<br />

interviews with several contributors which give readers a glimpse of the<br />

many conversations going on behind the scenes.<br />

The work of <strong>Aerie</strong> International is created, selected and published by<br />

young people whose futures and whose memories will be inextricably<br />

tied to this experience. Rather than seeing themselves primarily as<br />

separate, they will be part of a cooperative whole, a group who has been<br />

able to communicate actively and effectively in spite of physical distance<br />

and in celebration of cultural diversity. .<br />

In January, I wrote a note to Lorilee about an Iranian friend whose<br />

husband had been arrested for his participation in human rights<br />

work. The story is similar to many other arrests in various regions,<br />

some well-publicized and many which are not. He was fortunate to be<br />

released after two months of detention, but not everyone is so lucky.<br />

In this context, where people can be arrested for their beliefs and<br />

where information can be easily manipulated and censored, journals<br />

like <strong>Aerie</strong> International are essential. It is my hope that <strong>Aerie</strong> International<br />

will continue to be a fine example of cooperation, artistic vision, and<br />

inclusive thinking for years to come.<br />

Tami Haaland, poet and <strong>Aerie</strong> International Advisory Board member

sumi selvaraj lilburn, georgia, usa<br />

flight of the shadow | digital photography

tAble of ContentS<br />

Chemical Bonding<br />

myrah fisher<br />

Roses<br />

alexaundra swann<br />

A Watermelon Defeat<br />

jennie lee<br />

Home<br />

mercy ndambuki<br />

Kenophobia<br />

kathleen harm<br />

I Am a Street Kid<br />

romanius eiman<br />

For Five Hundred and Forty-Three Days<br />

jennifer giang<br />

Haiku<br />

yuka tsuruyama<br />

Fish-Fry<br />

taylor nicole marlow<br />

Psychology<br />

jonathan o’hair<br />

Worker Bee<br />

jake ross<br />

Interview<br />

jake ross<br />

Imitating Kerouac in the Summertime<br />

allison lazarus<br />

One Day in Future<br />

ayna kuliyeva<br />

The Army<br />

obaid syed<br />

Haida Statues<br />

marquette patterson<br />

Winter<br />

shapovalova victoria<br />

1<br />

2<br />

4<br />

6<br />

8<br />

10<br />

12<br />

16<br />

18<br />

20<br />

22<br />

30<br />

34<br />

36<br />

38<br />

43<br />

44

Coloring You<br />

michele corriston<br />

Fish<br />

alexandria kim<br />

How to Make Kimchi<br />

alexandria kim<br />

The Two Sides of a Name:<br />

Alexandria Song-Hwa Kim<br />

alexandria kim<br />

We Were so Wise<br />

jamie pisciotta<br />

Dubai<br />

nadia qari<br />

He Breaks Another Bottle, I Go For a Walk<br />

deborah gravina<br />

Echoes of Alexandria<br />

maria nelson<br />

Conversations About Love<br />

natasha joyce weidner<br />

Speech<br />

kelsie corriston<br />

Dressed in Navy Blue<br />

emma lucy bay pimentel<br />

Interview<br />

emma lucy bay pimentel<br />

Greenworld # 1<br />

daniel alexander gross<br />

An Immigrant’s Guide to Colorado<br />

melanie brown<br />

Caretaker<br />

wynne hungerford<br />

The Milkman<br />

annie chang<br />

Sky<br />

amelia parenteau<br />

Rudy Autio Visual Arts Award Winner<br />

Cover Art | Self Portrait by Austin J. Noll<br />

46<br />

50<br />

52<br />

53<br />

54<br />

56<br />

58<br />

60<br />

64<br />

68<br />

71<br />

75<br />

82<br />

84<br />

88<br />

90<br />

93

ChemICAl bondIng<br />

The luster of the elements<br />

Has made mountain ranges of your acids<br />

And exponents out of my wings.<br />

The scientific notation expands; the phoenix burns.<br />

I’m wandless and bare-brained<br />

And all operational thinkings have ceased.<br />

You, I can make no thesis,<br />

But your shimmer-swept eyes and<br />

Melting point blush are enough to form a hypothesis.<br />

Maybe we can experiment—you, my constant variable,<br />

And me, the dependent value.<br />

As different as the front and end of a chimera,<br />

But still undeniably one mythical beast.<br />

You’re pulling me into your orbit, an aesthetic satellite,<br />

And soon I’m circling you through light years and solar flares<br />

And you’re keeping me close, stopping me from soaring away.<br />

myrah fisher<br />

jacksonville, florida, usa<br />

But the dragon inside overwhelms,<br />

You eclipse me and I’m abandoned in the vacuum of imaginary numbers.<br />

1

alexaundra swann<br />

roswell, georgia, usa<br />

roSeS<br />

We were laughing.<br />

No one told a joke but<br />

we laughed even harder.<br />

We were kids<br />

barely in seventh grade<br />

taking a night stroll around<br />

the biggest lake I had<br />

ever seen.<br />

We passed<br />

a bright pink Spanish home<br />

we swore one day<br />

would be ours.<br />

We sat on the dock<br />

catching turtles,<br />

examining them<br />

and throwing them back in the water.<br />

We held hands<br />

and prayed that we<br />

would be together<br />

forever.<br />

We passed the home<br />

of an elderly couple<br />

who had a yard full of rose bushes.<br />

The man said, “Would you two like a flower?”<br />

and the hearts of two anxious girls<br />

could not turn him down.<br />

We tucked our roses<br />

behind our ears<br />

and we were happy.<br />

2

samuel j. willger<br />

lawrence, kansas, usa<br />

painted landscape | oil on canvas<br />

3

jennie lee<br />

norman, oklahoma, usa<br />

A WAtermelon defeAt<br />

The dress already lay out in front of the door that morning. I ate a<br />

Korean breakfast, complete with kimchi, rice, and tea, and sat quietly while<br />

Mommy fixed my hair into a ponytail and a bow. I must have been around<br />

four or five, and as I recall there were not many kids who looked like me.<br />

All the other children were pale and big-eyed. My parents worried about<br />

me because when I was younger I always used to follow this Chinese girl<br />

around in preschool. I didn’t know English and attempted to talk to her in<br />

a language foreign to her. I identified with her dark hair and small eyes, but<br />

that feeling was not returned; only now I know she dodged me and thought<br />

me strange. Even at a young age, I detected that I was different.<br />

Being accepted didn’t come to me as naturally as it did for most of my<br />

peers. This coupled with the fact that though I was born in the U.S., I had<br />

only learned Korean and couldn’t communicate well in English, which<br />

heightened my anxiety. I was unaware as to what I should expect in<br />

kindergarten but hand in hand with my mom, I timidly wandered in, my<br />

mother already having fussed over me as any typical parent would do on the<br />

first day for his or her offspring. Adorned in my watermelon dress I noticed<br />

my surroundings: the glaring fluorescent lights, impersonal white walls,<br />

the carpet with a unique, foul odor. The windows of the classrooms were<br />

decorated with tacky plastic things like smiling flowers in an attempt to<br />

seem welcoming. The truth was the school could swallow me whole, and<br />

me, I was helpless.<br />

Doubt hit me in waves and sudden thoughts rushed over me. What if<br />

nobody likes me? What if they think I’m weird? Would I play alone? Would<br />

I be left to try and push myself on the swing? I looked about, searching<br />

for a target; anything to hate to get my mind away from being at school.<br />

Violently, while hunting for the object of abomination, I located a victim:<br />

the red quarter-oval shape speckled with black dots on the neckline of my<br />

A-line dress, complete with thin green and white vertical stripes. Everything<br />

became clear to me; I knew instantly what I should do. I reminded myself<br />

that I had declared to my mother that morning, “The dress is ugly. I don’t<br />

want to wear it.” Her reply: “Look at it. It’s so cute – you’ll be the cutest in<br />

your class if you wear it. Remember, we were at Dillard’s and when I picked<br />

it out for you, you were so happy.”<br />

4

Then, I was content. But now – now things were different. People would<br />

judge me by that dress. I was wearing a watermelon! Mommy deserted<br />

me, leaving me with my teacher and a few boys and girls my age; we were<br />

the early ones. Nobody else was a fruit. I didn’t see any oranges or apples<br />

anywhere. As I defensively observed the environment, I wrung the melon in<br />

my fingers. I twisted it around my neck, wrinkled it underneath my palms<br />

and managed to mangle the stiff fabric momentarily: I did not want it to<br />

surface again. On my first day of school, it was my worst enemy. Though I<br />

saw a girl wearing a dress, it was nothing like mine. I observed the boys: one<br />

was wearing t-shirts and cargo shorts, and another wore jeans. Compared<br />

to the other children’s clothes, mine stuck out like a sore thumb. I did not<br />

even mind my dress if not for the crescent shape on the neckline, but that<br />

neckline was so undismissibly hideous. The watermelon was my problem,<br />

and if only I could hide it from everyone inside my fists, nobody would<br />

know. Nobody would know I was different. Nobody would criticize, “What<br />

is that little squinty-eyed girl wearing? Why does she have a plant around<br />

her neck? Why isn’t she wearing blue jeans like me?” With my little hand I<br />

frantically tried to scrunch my adversary up into something unrecognizable.<br />

Kids started pouring in, and again I didn’t see anybody who looked like me.<br />

When the teacher ordered my class to do activities, I had to admit defeat.<br />

With one last-ditch effort of squeezing my limbs a bit more, I finally opened<br />

my hands, palms up; I could no longer continue strangling my enemy. The<br />

little piece of cloth had beaten me, and dismayed, I participated in the<br />

games, the watermelon wrinkled but vivified again, taunting me out of the<br />

corner of my eyes at every second.<br />

I could not look anyone in the eye. Not only did I forfeit, but I was<br />

wearing a fruit. And not only was I wearing a fruit, but I was wearing<br />

a wrinkled, ugly fruit. The rest of the day commenced and I remained<br />

ill-at-ease and self-conscious.<br />

As I reminisce about that memorable day, I recognize I was too young<br />

to learn that lesson. I did not even know the source of my anxiety. As I<br />

matured, I realized it was not about the clothes I was wearing; it was about<br />

being comfortable in my skin – my skin that has a slight tint distinct from<br />

most.<br />

On one particular trip to the bank, I miraculously spotted a blonde girl<br />

wearing an almost exact replica of the watermelon dress. She donned it with<br />

such nonchalance it would have put my self-conscious, five-year-old self to<br />

shame. Her bearing convinced me to search for my old outfit in the corner of<br />

my closet shelf, and after I lay it on the floor neatly – much like my mom did<br />

for me my first day of kindergarten – I called out a realization to my mother,<br />

“Mom, you were right! I must’ve looked adorable that day.”<br />

5

mercy ndambuki<br />

norman, oklahoma, usa<br />

home<br />

The drops beat fiercely on the tilted window panes<br />

Ripping through the gutters of the roof<br />

They attack the red soil<br />

Soil that bears a few new huts.<br />

It has changed so much.<br />

The rumbling chatter bursts out of the thatched kitchen<br />

With delight, hiding the silence.<br />

Astonished I glide to the source<br />

And watch from a distance the unending folktelling<br />

All of them, grandma and her young granddaughters,<br />

Cornering the scorching flames<br />

With arms stretched out.<br />

6

mackenzie enich<br />

missoula, montana, usa<br />

market in arusha | digital photography<br />

7

kathleen harm<br />

ho-ho-kus, new jersey, usa<br />

KenoPhobIA<br />

My keraunograph records a thunderstorm today.<br />

A stranger walks in with his beat-up kennebecker on his back;<br />

a brown kausia on his head—<br />

he’s beautiful but when I hear his voice, there’s kalon.<br />

He prepares a thick kava from a Polynesian plant;<br />

I keck at the smell coming from the olive-green jug,<br />

but he becomes the kelpie and speaks to me softly,<br />

and suddenly, that scent from the kalpis seduces me.<br />

I take a sip and I’m in kef:<br />

the colors of the room swirl into kente—confusion; euphoria.<br />

But he drops the kedge and the ship rocks.<br />

I hear a clamor through the fabric;<br />

my head hurts from the katzenjammer.<br />

Around his thin waist is a keister;<br />

he takes out a screwdriver and opens my heart.<br />

I try to kep the blood;<br />

it flows until the organ is empty, and no keloid forms to cover the hole,<br />

but I have kenophobia, so only he can fill the void.<br />

Keraunograph: instrument for recording distant thunderstorms<br />

Kennebecker: knapsack<br />

Kausia: Macedonian felt hat with broad brim<br />

Kalon: beauty that is more than skin deep<br />

Kava: narcotic drink<br />

Keck: to retch; to feel disgust<br />

Kelpie: mischievous water spirit<br />

Kalpis: a water jar<br />

Kef: state of dreamy or drug-induced repose<br />

Kente: hand-woven African silk fabric<br />

Kedge: small anchor to keep a ship steady<br />

Katzenjammer: hangover; uproar; clamour<br />

Keister: burglar’s tool kit<br />

Kep: to catch an approaching object or falling liquid<br />

Keloid: hard scar tissue which grows over injured skin<br />

Kenophobia: fear of empty spaces<br />

8

austin j. noll<br />

lawrence, kansas, usa<br />

wrinkly face quartet | digital art<br />

9

eiman romanius<br />

southern africa, namibia, otjiwarongo<br />

Tita ge a!gan/gôa<br />

Ā, mû ta ge ra âitets tasa<br />

/Apoxawaba xu ta ra ‡û // aeb ai<br />

Sa ui-uisa aisa ti !oa<br />

Tsî t’ra // nâu sa uixaba<br />

Sa !oa ta ge / apob hîa / apoxawab !nâ ao‡gāhe hâb khemi ī.<br />

Xawets ‡an tare-i !aroma ta !gangu !nâ ra hâsa?<br />

Tare-i !aromab !ganna ti //khā//khā!nā-omsa?<br />

‡Âi!gâre!<br />

/Khowemâb ai ta ra ûi!kharu, aodo mâ!khaigu tawa !nari-aoga nape, audode//ā.<br />

/Gui// ae ta ge /on-e ūhâ i – ti ‡hunumasa.<br />

Nēsisa da ge tita tsî /hosan tsîda /gui /onsa ūhâ - !gan/gôan.<br />

Ti în tsî / aokhoen xa ta ge //orehe<br />

HIV/Aids xa ta de !guni/gôa tsî huisen//oase !hūbaib !nâ<br />

//nāxūhe.<br />

/Gâb, /khurub, dâu!khūdi, /û/khāhes !ganga !oa //garite.<br />

Ûib /ūsa ‡gās ai xūmâite.<br />

/Hōsana ta !gangu ai ūhâ.<br />

‡Gui xūna da ūhâ /goragu da rana:<br />

!Âs, !aob, hâ!khai-osiba,<br />

/Khai!nâ kartondi !nâ //omma.<br />

//Khore t’ran ge, /gamsa !anu kharob, /gamsa ‡û-i tsî ti ‡hunuma<br />

/ons /namma.<br />

//Khore ta ra in tita /kha âi, âi‡uis ose.<br />

Tari-e !ganga xu nî ū‡uite?<br />

‡Âis !nâ ūhâ re, //aris ‡gae‡gui-ao ta ge.<br />

//Îta, tita ûiba !ganga xu ge //khā//khāsenta.<br />

Tsî nēsi !gan‡an hâta.<br />

10

I Am A Street KId<br />

romanius eiman<br />

otjiwarongo, namibia, southern africa<br />

Yes, I have seen you laughing at me as I ate food from the dust bin.<br />

I have seen your look of disgust and even heard you say yuck.<br />

To you, I am like litter thrown in the dust bin.<br />

But have you thought about why I live on the streets?<br />

Why the street is my classroom?<br />

Think about it.<br />

I survive on begging, waving motorists into parking areas, washing cars.<br />

Once upon a time I had a name, my own one.<br />

Now me and my friends have the same name – street kids.<br />

I was abused by parents and relatives.<br />

HIV/Aids left me an orphan, defenseless against the world.<br />

Poverty, drought, floods, neglect, led me to the streets.<br />

Life has left me nowhere else to go.<br />

I have friends on the streets.<br />

We have lots of things we share:<br />

Hunger, fear, lack of shelter, sleeping in cardboard boxes.<br />

I long for a warm, clean bed, warm food, love of my own name.<br />

I long for you to laugh with me, not at me.<br />

But who will lift me off the streets?<br />

Remember, I am tomorrow’s leader.<br />

I, who have learned about life from the streets,<br />

And having become streetwise.<br />

My poem is written in English and Damara Nama, my mother tongue. Damara Nama<br />

(Khoisan group of languages, also used by the San Bushmen) is a very old language that<br />

involves clicking sounds and is only spoken in parts of southern Africa. In order to write<br />

it down, it involves four different symbols, one each for where the tongue is placed in the<br />

mouth in order to make the correct sound. - romanius<br />

11

jennifer giang<br />

lilburn, georgia, usa<br />

for fIve hundred And forty-three dAyS<br />

I. Photograph<br />

I don’t wait for Mom to stop the engine, just open the door and run<br />

outside, not even bothering to slip on my sandals. The grass is rough against<br />

my feet, and I probably just stepped on an ant pile, but I don’t care. All I<br />

care about is the heat, and smell, and feel of the June sun burning through<br />

my shirt, melting me with its buttery rays. Everything looks the same. The<br />

rusty makeshift watering can is still propped up by the dead stump, and the<br />

wild shrubs are still spreading their arms out, greedily taking in the dusty<br />

concrete.<br />

I nearly trip on the pile of shoes that booby trap the entry as I follow<br />

Jane, my sister, through the doorway. Aunts and uncles crowd around us,<br />

and we grimace as Mom prods us towards them. The ritual begins: an holá,<br />

cómo estás, quick hug, air kiss on both cheeks. We get to my abuelita—<br />

my grandma—and she smiles and envelopes<br />

me awkwardly with her left arm. “Mira qué<br />

hermosas están poniendo.” Look at how pretty you<br />

all are becoming. I kiss her, wishing I could say<br />

something, but the Spanish limits me to this<br />

small greeting.<br />

Soon, everyone begins shuffling towards the kitchen, grabbing plates and<br />

plunking down food onto their dishes. The smell of piquant enchiladas is<br />

just beginning to tickle my nose when Mom calls at me to come eat. I grab<br />

a platter and stand in the corner next to the air vent so the cool air can slap<br />

my legs.<br />

My abuelita laughs from across the room, and her gold tooth glints under<br />

the harsh glare of the light bulb. She reaches over to eat but as she begins to<br />

pick up her fork, her smile fades. The fork doesn’t want to come up and lays<br />

there, stagnant on the table, as if that piece of Dixie plastic were the weight<br />

of a whole sea. Her gold tooth disappears behind her lips now, and she grabs<br />

the fork with her left hand instead. No one notices.<br />

I watch her from my corner, and get dizzy, as if something was pulling me<br />

out of the scene and framing my abuelita’s crippled right hand into a distant<br />

snapshot.<br />

12<br />

The ritual begins:<br />

an holá, cómo estás,<br />

quick hug, air kiss on<br />

both cheeks.

II. Spying<br />

Mom calls it “showing houses.” She drives around for hours, opening lock<br />

boxes and showing people their future homes. She likes having us kids in<br />

tow: Catalina squawking in the baby seat, me and Jane breaking the law by<br />

sitting on the floor near the back. That annoying T-Mobile ringtone sounds<br />

again—probably the tenth time in the last twenty minutes—and she juggles<br />

the clamshell phone between her ear and shoulder, while she pulls up into a<br />

cul-de-sac. She talks—whispers— to an unknown face for fifteen minutes.<br />

The three letter acronym<br />

stands for sitting in an<br />

ugly blue sofa-chair for<br />

one year with nothing<br />

to do but memorize the<br />

shapes of the blemishes on<br />

the wall.<br />

Jane pokes at me to watch a baby getting<br />

burped by her dad in a driveway.<br />

The cell finally snaps shut, and I hear<br />

Mom tossing it to the passenger’s side.<br />

She’s upset, and the phone falls to the<br />

ground. I peek at her through the gap<br />

between the car seats. Her head is resting<br />

on the wheel, nestled in her forearms.<br />

“Abuelita has ALS,” she murmurs into the<br />

leather. Jane and I glance at each other.<br />

ALS. What is that? We wonder what could be giving her a headache. And<br />

making her cry. I see her trembling through my peephole.<br />

III. One Year in a Blue Seat<br />

It takes me a year, but I finally figure out the meaning of ALS. It means<br />

falling straight backwards onto the garage floor and getting stuck in a<br />

wheelchair. It means rolling to a million doctors and losing all sense of<br />

privacy. It means getting hand fed oatmeal for every meal, then switching<br />

over to a stomach tube. It means breaking out into raw red sores. But worst<br />

of all, the three letter acronym stands for sitting in an ugly blue sofa-chair<br />

for one year with nothing to do but memorize the shapes of the blemishes<br />

on the wall. At least, this is what it means to my abuelita.<br />

IV. A Routine<br />

We go to Abuelita’s house almost every day: after school, on the<br />

weekends, always during the holidays. Only the ritual’s changed now.<br />

When we arrive, there are no lively greetings, just a quick hello then off<br />

to work. Before I see my abuelita for the first time, I’m not sure what to<br />

do. Wave? Give her a kiss? A hug? I awkwardly make my way past the<br />

hospital-like-bed and grey portable potty to her chair. She doesn’t look at<br />

me—she can’t, so I stand off to the side and try to smile. Mom’s already<br />

sitting next to her, rubbing her back and hands to make the blood flow. I<br />

feel guilty for holding back a gag, but the room smells like a disinfectant<br />

someone scrubbed a million times to get rid of the smell of chilies. There’s<br />

13

something strong that makes me want to sneeze, too. Probably some<br />

medicine. Mom glances at me and nods her head, so I grab Jane’s hand and<br />

try to situate myself on the large armrest. As I reach down to hug Abuelita,<br />

she starts as if she were going to talk. But I know she won’t, so I burrow my<br />

head into her braid and whisper.<br />

Afterwards, I back away towards the kitchen, the perfect view, and<br />

pretend I’m minding Catalina playing with our cousin on the floor. Mom’s<br />

giving Abuelita a rinse now. She dips the<br />

rough washcloth into a bowl of hot water<br />

and rubs it onto her twisted arms. Mom<br />

laughs, telling Abuelita about the time<br />

Catalina threw a fit at Target because she<br />

saw a girl wearing the feathered tiara she<br />

wanted. Even though I know Mom wants to, she can’t cry. Abuelita will see<br />

her. I walk to the refrigerator, open it, feel the rush of cool fall over me, and<br />

cry for her instead.<br />

V. You Are My Sunshine<br />

I call Mom’s cell frantically, wishing she would pick up her dumb phone.<br />

She’s been gone all night—on New Year’s Eve, too. Jane, Catalina, and I sit<br />

on our knees next to the window and peer through the blinds, watching the<br />

fireworks in an attempt to entertain ourselves.<br />

Catalina hears the rumble of the garage door first, and we all sprint down<br />

the stairs. “Where were y—,” Catalina starts irritably as the door opens, but<br />

I shush her. Mom’s holding a small mountain of tissues in her hands. There<br />

are deep nail marks on her arms, as if she’s been clutching herself, and sticky<br />

tearstains on her cheeks. We follow her quietly to Catalina’s room, and the<br />

bolt clicks when Jane closes the door.<br />

“Did she…?” I falter, before I see Jane’s glare. Mom gives a half-nod and<br />

doesn’t bother wiping the tears that are starting to run down her face again.<br />

Her body gives a massive heave, and she speaks with a halt. “She died crying.<br />

She died crying! Ay, dios mio, oh my God, oh my God.” My vision blurs, and I<br />

lie on the floor, mimicking my mom with soft shudders. Catalina doesn’t<br />

know what is going on, so she pets Mom’s head, her small fingers running<br />

through the stiff knots. I can’t breathe; my tongue feels heavy and there’s a<br />

kink in my throat. “Mommy,” I plead and turn to face her. “Mommy, maybe<br />

it was better for her to go. She was suffering so much and—and, now she<br />

doesn’t have to.” I don’t think she hears me.<br />

VI. A Nap<br />

Everyone around me is praying, fingertips touching their lips, mouthing<br />

Ave Maria in unison. I clasp my hands together, but don’t say anything. I<br />

just listen to the soft Spanish tongue cradling my abuelita as she sleeps.<br />

14<br />

Even though I know Mom<br />

wants to, she can’t cry.<br />

Abuelita will see her.

jessica byrne<br />

carlisle, cumbria, uk<br />

country lane | traditional black and white photography<br />

15

tsuruyama yuka<br />

japan, kumamoto<br />

16

taylor nicole marlow<br />

norman, oklahoma, usa<br />

fISh-fry<br />

Grandfather pulls the white glass plate from the fridge with a swish.<br />

He walks out the back door—through the kitchen and into the<br />

garage pantry hallway.<br />

Atop the massive deep freeze filled with frosty<br />

quail pastries hamburger<br />

he builds his station—<br />

a plate of fluffy flour, corn meal, and crimson spices<br />

a vat filled with already crackling oil<br />

and<br />

the crappie<br />

caught fresh from Uncle Tony’s pond that early morning.<br />

I sit on the step behind him, the heavy concrete floor beneath me.<br />

My hands on my bony seven year-old knees, I lean forward to watch him<br />

dip pat sprinkle<br />

the powder onto each thin filet.<br />

He is quick but skilled as he lays the fish into the<br />

pop and sizzle<br />

with his freckled leather hands.<br />

He<br />

batters fries retrieves<br />

until the stack of golden brown is high enough for eleven hungry mouths.<br />

Behind me, I hear the<br />

chime and twinkle<br />

of glass-wear and silver touching tablecloth.<br />

I hear the<br />

laughter and happiness<br />

flowing from the nine other bodies.<br />

It is almost time as Grandfather turns around to find me<br />

the youngest<br />

watching patiently, my eyes wide and excited.<br />

Hey, baby Taylor, ready to eat?<br />

He chuckles heartily and wraps me up in his bear arms as I stand.<br />

Then, I open the door to the rest of our family.<br />

The rest of Thanksgiving.<br />

18

sophie howell<br />

carlisle, cumbria, uk<br />

sunflower city | acrylic on canvas<br />

19

jonathan o’hair<br />

norman, oklahoma, usa<br />

PSyChology<br />

Everything psychological is simultaneously biological. In our bodies,<br />

there are chemical reactions to literally every single emotion we have.<br />

Pain, frustration, anger, boredom, anticipation, joy, relief, empathy, and<br />

wrath are all triggered by a biological gun. Science can’t tell us all of the<br />

secrets of the mind, but it can shed some light on the mystery that is our<br />

very own emotional balance.<br />

What most people don’t know is that there is a steady truce between<br />

the biological functions of the body and the mental responses of the<br />

mind. Even though I hate scientific explanations as much as the next<br />

guy, I paid close attention to what that balance literally means in<br />

common language. That balance is the main driving force in whether you<br />

are happy or sad. Even though we can’t literally measure those levels of<br />

happiness, science can still pinpoint one of the main outlets of function<br />

starting at the different nervous systems. If you’ve ever played a sport,<br />

been in a car wreck, or even pumped yourself up for a job interview,<br />

you’ve experienced the effects of the sympathetic nervous system. You<br />

know when your heart rate speeds up and your blood pressure rises,<br />

time literally slows down. And if something alarms, challenges, or<br />

threatens you, the sympathetic nervous system is there to allow you to<br />

be at your best physically. Unfortunately, going back to the balance,<br />

there also has to be a physical reckoning for every action our mind takes.<br />

The parasympathetic nervous system is that tired feeling after your<br />

sympathetic stress. The crash at the end of a sugar rush, if you will.<br />

But what does that have to do with our emotions, and our happiness<br />

level. Sadly enough, the basic principal used in the sympathetic and<br />

parasympathetic systems is used in our emotional outlets. With every<br />

single feeling of happiness, there will be a different but proportional<br />

feeling of sadness. So the true culprits behind the frustration at<br />

stoplights, the anxiety in airports and elevators, and the anger at an<br />

insult is not the outside stimulus so much, but rather that our bodies<br />

are compensating for previous emotions. It is the same when you laugh<br />

at something you didn’t think you found that funny or when you enjoy<br />

a movie you know you don’t like. If external conflicts are a fire, then our<br />

biological functions are the match, and the phrase “Don’t let that bother<br />

you” never seemed so impossible.<br />

20

worapan kongtaewtong<br />

bangkok, thailand<br />

retrospective | colored pencil on paper<br />

21

jake ross<br />

greenville, south carolina, usa<br />

WorKer bee<br />

The way River walked made me have to cross my legs sometimes, if<br />

you know what I mean, and I think you do. She wasn’t like most girls,<br />

with dark denim jeans hugging like a second skin and over-exaggerated<br />

mosquito bites pressing out of low-cut polo shirts. River was different;<br />

she was – what’s the word? – unconventionally sexy, like straight out<br />

of the movies, with her flowing skirts and tennis shoes made out of<br />

recycled tires and bouncing,<br />

brick-colored hair that fell<br />

down to where I imagined<br />

the crack of her ass to start.<br />

That may not sound so hot to<br />

you, but I swear it’s the way<br />

she walked that got me going.<br />

That walk, it could kill a guy.<br />

She walked real aggressive, like if you got in her way she’d slam<br />

you against the lockers and verbally assault your character until you<br />

realized you’d been wrong all your life. She was a real hippie, see, but a<br />

smart hippie, up on all the current events and all that. River was fiery,<br />

and she openly hated stupid people. She regularly destroyed dunces<br />

and left them floating in her wake. Once, in history class, Football<br />

Bobby made this comment in favor of the president, but he didn’t have<br />

the facts to back it up, see, so River took him out in front of the whole<br />

class, proverbially tackled him on the fifty-yard line of Debate Stadium,<br />

knocked his helmet off and left him for dead. For the rest of the year,<br />

Bobby was real quiet in history class.<br />

But maybe that was a bad example; maybe a better example would<br />

be Fresh Out of Home-School Susan, who felt the need to give her own<br />

opinion on stem-cell research in the middle of a biology lecture, and even<br />

Professor Whitaker couldn’t quiet River down then; she stood up and<br />

yelled until Susan shrank into her turtleneck like, well, a turtle, a few<br />

wires anxiously escaping her normally perfect brunette bun. After that,<br />

Susan moved from the front row to the back one. She knitted. Sometimes<br />

River would shoot Susan a look, and Susan would start knitting like the<br />

craziest son of a bitch I ever saw. Her face would scrunch up and redden<br />

out of anger and she would start knitting so fast that you could hear her<br />

22<br />

River was different; she<br />

was – what’s the word? –<br />

unconventionally sexy, like<br />

straight out of the movies.

little sticks clanking together from the front of the room. You know,<br />

those little sticks girls use to knit. I don’t know what they’re called.<br />

How can you expect me to know what those stupid things are called?<br />

Anyway, it was the walk, I swear to God it was. My words can’t even<br />

do it justice. That strong, powerful walk in contrast with all those<br />

flowing dresses and that flowing hair, it was just beautiful. All that<br />

contrast, it got me excited. Shut up, you know what I mean. Maybe you<br />

don’t. Whatever.<br />

Me, I’ve never been savvy like River was, but I wanted to be on that<br />

like a duck on a June bug, so I figured maybe I could trick her into<br />

thinking I was smart just long enough to get that flowy skirt up over her<br />

head. I don’t think she really noticed me, see, it’s easy for me to hug the<br />

wallpaper, and our eyes would never meet even if I stared at her for a<br />

whole class period, even if I sent all kinds of vibes her way. I was always<br />

on the lookout for something interesting I could say that would make me<br />

look smart in her eyes, in those fiery green eyes that she batted when she<br />

did that strut. Hot damn, that strut.<br />

I knew I’d found my chance when I called Time and Weather one<br />

morning. Time and Weather is free, you know, or at least it’s free where<br />

I live, and before they tell you the time and the weather they always<br />

play an advertisement, usually for a chiropractor or Meals on Wheels.<br />

It’s in my interest to know the time and the weather, because I’ve got<br />

to ride my bike to school and back, come hell or high water. But when I<br />

called on this particular morning, the ad was for Bill Maloney’s Custom<br />

Honeybee Removal. Hold on, let me think of what it said. Got bees in your<br />

Apparently, because we<br />

pollute the air, the worker<br />

bees can’t smell right anymore,<br />

and they get lost and die in<br />

the woods or whatever.<br />

trees? That was the first part. And<br />

then: When it’s warm, those bees will<br />

swarm! Call today! Real cutesy,<br />

real stupid, but that was my<br />

chance.<br />

All the honeybees are dying,<br />

see. A third of them are already<br />

dead. We studied them in<br />

biology, after the River-Susan Battle Royale. Apparently, because we<br />

pollute the air, the worker bees can’t smell right anymore, and they get<br />

lost and die in the woods or whatever. And because the worker bees die,<br />

the rest of the hive dies, including the queen. This is some kind of big<br />

deal, because honeybees pollinate our food, and if they go extinct we’ll<br />

have to do it ourselves. Some kind of suck job, huh? With my luck and<br />

my grades, that’s probably what I’ll wind up doing – squirting pollen<br />

onto buds, or however the hell that works.<br />

So I called the guy. I felt like a regular secret agent then, and maybe<br />

23

I got a little too excited; you know how I get sometimes. But I was real<br />

good about it; I got control of myself and caught my breath, and when<br />

the guy said, Hello? I said, Is this the bee man? and he said, Yes, and I said,<br />

My granny’s got a bee problem, how do you get those bees down, do you cut down<br />

the hive and then transport them somewhere? and he said, No, we just gas them;<br />

they drop dead within twenty-four hours, guaranteed, and I said, Isn’t that bad<br />

for the environment? and he said,<br />

Son, which do you care about more, the<br />

“environment” or your granny being<br />

stung by a bunch of insects? and when I<br />

didn’t say anything, he said, Where<br />

does your granny live? and then I got<br />

nervous and hung up.<br />

That may sound like a failure<br />

to you, but I’m not James Bond, so<br />

get over it. There are other ways<br />

to find out about honeybees. On<br />

the internet, I found out about<br />

the worker bees. They do all kinds of stuff you wouldn’t guess, using<br />

processes you wonder how they set up without talking to each other,<br />

without signing a constitution. The worker bees are the sexual misfits.<br />

Some of them go on errands, some of them guard against intruders, some<br />

of them tidy up the hive before the queen does room inspection, some of<br />

them carry out the dead and injured. They’re all little humans in little<br />

palaces, and I guess we’re killing them all, and I knew that would set<br />

River ablaze.<br />

I made my move before history class started. I didn’t want to do it<br />

in front of the chemistry teacher; I just knew that crazy Whit would<br />

overhear me and compliment me for being “well versed,” or some crock<br />

like that, make me sound like a geek, a bozo. I knew the history teacher,<br />

a coach who didn’t know the difference between Cleopatra and Reagan.<br />

I knew he wouldn’t give a rat’s tail. He was the kind that went home and<br />

learned from the textbook along with us, and if you asked him a question<br />

he didn’t know, he’d go into a class-long rant about Bonnie and Clyde,<br />

just to avoid answering. He said that when they robbed all those places<br />

during the Great Depression, Bonnie never fired a shot. Did you know<br />

that? During the shoot outs, Clyde fired and Bonnie loaded.<br />

Anywho, that day I took a deep breath and dove in with both feet;<br />

I marched straight up to River and told her about the bees and Bill<br />

Maloney. I could tell this surprised her enough to quell her rage some,<br />

but I realized I needed to have a reason for striking up a conversation, so<br />

I said, Wouldn’t it be funny if we found out where this guy lived and, say, egged his<br />

24<br />

On the internet, I found<br />

out about the worker bees.<br />

They do all kinds of stuff<br />

you wouldn’t guess, using<br />

processes you wonder how<br />

they set up without talking to<br />

each other, without signing a<br />

constitution.

house? and I could tell that was the turning point, where she would either<br />

take the bait or bite my head off, and holy mackerel did she ever take<br />

it. She said, I like your style, and her slender white fingers slithered down<br />

into her blouse and emerged with a slip of paper that had her number on<br />

it, like it had been waiting for me there, since forever. She said, Call me,<br />

we’ll talk.<br />

We talked. Our conversations were pretty one-sided. River would<br />

cram information into my ear about politics and the “E.P.A.” and some<br />

bunch of yahoos that protect animals, “Petta” I think it was, as in “to<br />

Petta dog,” I’m guessing. Sometimes I’d have to think of hitching that<br />

skirt up, just to keep sane. Her pet name for me was Honeybee, which<br />

made sense and wasn’t so bad. It was just her talking non-stop, and<br />

when she’d go hoarse, she’d ask me a question. Once it was, How do you<br />

feel about nature, Honeybee? and I almost groaned out loud. I told her about<br />

the big oak in the forest behind our double wide, how it used to be nice<br />

but now it’s infested with all of these little white bugs that attack you<br />

when you go near it, fly at your eyes and mouth and nose, like little space<br />

ships protecting the Death Star. She didn’t say anything, and I said, I<br />

don’t know, nature is kinda just a backdrop for the rest of life. And she said, No,<br />

you’re such an idiot, life is just the backdrop for nature; humans are just reckless,<br />

unstable weaklings teetering on top of magnificent organic and non-organic processes,<br />

or some crap like that, and then<br />

But now it’s infested with all<br />

of these little white bugs that<br />

attack you when you go near<br />

it, fly at your eyes and mouth<br />

and nose, like little space ships<br />

protecting the Death Star.<br />

she hung up.<br />

I thought that was curtains for<br />

me, but it wasn’t. River called<br />

back and apologized, and a few<br />

weeks later, she invited me over<br />

for dinner with her father. She<br />

picked me up in her white van<br />

and drove me to their cottage<br />

in the mountains. There was<br />

wilderness everywhere, but it wasn’t po-dunk or anything. It was<br />

classy looking, it had electricity and running water, and there was some<br />

expensive furniture inside.<br />

Before going inside, we ran around in the woods, chased after each<br />

other and then collapsed in a random spot. She was panting, and I would<br />

have been panting too, but I was too focused on her heaving chest to<br />

make a sound. There was silence, and I thought, Is this it? Is this the day?<br />

but no, she started talking. She said, You know Honeybee, everyone in the<br />

world is stupid except you and me. Maybe my father, but he’s gone soft. Everyone<br />

else, they’re destroying the world, and it’s not even on accident anymore. I said, I<br />

don’t know, it seems to me that maybe God and the earth are going to do what they’re<br />

25

going to do, and I instantly wanted to catch those words and stuff them<br />

back in. She turned all the way over and I could see her coiling up, about<br />

to strike, but she stopped herself. She smiled and patted my head like<br />

a dog’s. That’s cute, she said, but you trust me that I’m right, don’t you? and I<br />

nodded, of course. I realized that it must be pretty lonely for River, up<br />

here on this mountain where she knows everything and the view looks<br />

down on the people who don’t.<br />

Before dinner River ran up to her room to check her email, and I<br />

followed her upstairs to size up her bed. I noticed that she had to<br />

use a lot of passwords to get on to her computer, which I knew was<br />

weird, because I’d used computers in school before and they weren’t<br />

that complicated, weren’t that secretive. I didn’t say anything about it<br />

because I didn’t want to sound simple. The conversation at dinner was<br />

pleasant; River’s father, Wayne, was a nice guy, even though he was<br />

divorced.<br />

After dinner, we sat in front of the television in the living room and<br />

watched an old episode of Wayne’s TV show, Wayne’s Wonders. It used to<br />

be on public television, apparently, and it was a show about nature, big<br />

surprise. Wayne explained that the show used to focus on local<br />

scenery, but when the show got more funding the crew went on more<br />

exotic trips, like to the Grand Canyon. On the screen, a much younger<br />

Wayne and a woman stood beside a bush and talked. The cameraman<br />

slowly zoomed in on the bush until you could see a praying mantis<br />

perched between the leaves.<br />

River went up to her room again, to check something on her<br />

computer. The tape ran out. I asked Wayne why the show was canceled,<br />

and he said, Aw, people just don’t care about that stuff anymore, and most people<br />

didn’t care even then. His eyes kind of<br />

lost focus then. I’m not a relationship<br />

expert, but I couldn’t help but wonder<br />

if the woman in the show had been<br />

his wife; she struck a keen likeness<br />

to River. Maybe she’d left because<br />

Wayne got too caught up in his work; maybe it’s possible to love nature<br />

too much and a person not enough.<br />

River came back downstairs with an unnatural smile on her face. Pops,<br />

I’m taking Honeybee and we’re heading out, she said, and I mouthed, We are?<br />

and she punched me in the arm. Wayne laughed. Watch out, my River is a<br />

firecracker, he said, and I said, Yessir, how I know it, and we left the cottage.<br />

River walked me to the van, and we got inside and drove for a long time.<br />

I could tell she wasn’t taking me home, or to the movies, or anything<br />

like that, but every time I tried to ask about it she would turn up the<br />

26<br />

Maybe it’s possible to love<br />

nature too much and a<br />

person not enough.

my ngoc to<br />

lilburn, georgia, usa<br />

radio, even<br />

if it was a<br />

mindless<br />

song I<br />

knew she<br />

didn’t like.<br />

After<br />

awhile,<br />

River got<br />

this look<br />

on her face.<br />

She was<br />

squinting<br />

in the dark,<br />

trying to<br />

read the<br />

street<br />

signs, being<br />

real careful<br />

of where<br />

we were<br />

going, like<br />

it was some<br />

secret.<br />

Wouldn’t<br />

it be funny<br />

if we had<br />

wound up<br />

on McBee<br />

Street, or<br />

some crap<br />

like that,<br />

but no, we<br />

were on<br />

transcriptions in time | pencil drawing<br />

Wilkinson<br />

Avenue, on the opposite side of town from where I live, and on the<br />

opposite altitude from River’s cabin. We parked and River killed the<br />

engine and the headlights and everything fell dark, and I thought Holy<br />

mackerel, this is it, this is it. She climbed into the back of the van and I<br />

jumped back there like a bullfrog, and I was kissing her and I grabbed<br />

27

her thigh. But I guess I was biting her lip and maybe I was grabbing<br />

a little too hard, see, you know how excited I get sometimes, and she<br />

pushed me off and wiped her mouth and said, No, Honeybee, that’s not<br />

what we’re doing, and I realized we were sliding around on something<br />

uncomfortable. She lifted up a canvas sheet and lit up a flashlight and<br />

shined it on a bunch of metal canisters.<br />

I said, This doesn’t make much sense to me, and she said, This is the stuff<br />

Maloney uses to kill the bees; his house is<br />

right there, and I said, I don’t follow,<br />

but by then I figure she’d already<br />

left me behind, in her head at least.<br />

She pulled her skirt up over her<br />

head, but not in any way that I liked,<br />

because she was wearing black<br />

sweats underneath. She whipped out<br />

this black knit cap and slid it over<br />

her face, and every bit of that brickcolored<br />

hair disappeared. It wasn’t<br />

two seconds before she had gloves<br />

and a ski mask on me, too. As we walked up to his house, it seemed to<br />

me that it didn’t look like the house of anyone evil. River walked around<br />

and looked in all the windows until she found the bedroom, and she<br />

jimmied the window open real quiet. She walked over to me and handed<br />

me the canisters and said, He’s in there asleep, throw them in, and I said, No, I<br />

can’t… your walk is different, and she said, What are you talking about? and then<br />

she said, Never mind, just throw them in. You want me, don’t you? Throw them in.<br />

Even in the dark, even through the slits in her mask I could see those<br />

green eyes, so I figured there was some hope. I pulled the tabs on the<br />

bombs and started throwing them in, one by one. Those things don’t<br />

explode, you know, they just fog up the place, so we had to stand there<br />

for a long time and wait. I started getting nervous. We have to stop it, I<br />

said, he’s asleep and he’ll just breathe it in until he’s dead. She said, Shut up, and<br />

not much after that the upper half of Bill Maloney exploded out of the<br />

open window, red-faced, drooling, wheezing, sputtering. River grabbed<br />

my arm and said, Let’s go, but I didn’t follow her. I looked straight into<br />

the face of Bill Maloney as he hung there. I don’t know who he reminded<br />

me of, maybe Wayne or my own father, maybe the coach or Professor<br />

Whitaker, but he certainly did not have the dead eyes that a murderer<br />

should. On the contrary, his eyes were teary and wild, like something was<br />

being robbed from him but he couldn’t comprehend what. I walked over<br />

and hauled Bill Maloney safely out of his house, and I had to run all the<br />

way back to my double wide on foot, see, because River was already gone.<br />

28<br />

She whipped out this<br />

black knit cap and slid it<br />

over her face, and every<br />

bit of that brick-colored<br />

hair disappeared. It<br />

wasn’t two seconds before<br />

she had gloves and a ski<br />

mask on me, too.

I guess I blew it on that one.<br />

Maloney didn’t die. I think the police went to his house, but nothing<br />

came of it. He picked up and moved further south, and I felt sorry for any<br />

man who has to move constantly to make a living, one step ahead of the<br />

knowledge that’s trickling down, state to state. River left, and not even<br />

Wayne knows where she went. He hired some geek, some bozo to crack<br />

open her computer and under all those passwords he found out River<br />

had joined some kind of organization, a bunch of<br />

Even if she’s<br />

in disguise, I<br />

can spot that<br />

walk from a<br />

mile away.<br />

environmental freaks with their morals in the wrong<br />

place.<br />

I reckon that’s the most interesting thing that<br />

happened to me all year, what with bombing a guy<br />

and finding the love of my life and all. I don’t have<br />

the money for a car, but every weekend I search a<br />

different area with my bike, like a detective, looking<br />

for River. You can come help me look one day, if you want, but I’m the<br />

only one that can spot her. Even if she’s in disguise, I can spot that walk<br />

from a mile away.<br />

See, I’ve got this feeling she’s in the wilderness.<br />

29

jake ross<br />

greenville, south carolina, usa<br />

IntervIeW mAy 2009<br />

Jake Ross was one of those persons who stuck out right from the beginning.<br />

On our first Sunday workday, we lounged around reading piece after<br />

piece of writing when we happened upon Jake’s story “Worker Bee.” At<br />

first, we didn’t quite know what to make of it. Hesitant giggles escaped<br />

our lips as we tentatively read the first few pages. We decided to call in<br />

reinforcements. Katie, the editor, was outside the room at our computer<br />

lab, so we called her into the classroom. She sat on the table, and as her eyes<br />

scanned the pages, a smile spread across her face. She proceeded to read the<br />

whole story aloud. Belly laughs erupted when Katie got to the parts where<br />

the narrator described River’s walk, the way her hips swayed, the narrator’s<br />

quirky descriptions and the truth of being in love with someone who just<br />

doesn’t love you back. River may not deserve it, but we were all just as<br />

smitten with her as that blindly loyal and sexually frustrated narrator. We<br />

found ourselves quoting it in class daily. We knew we had to meet the man<br />

behind the story. So, without further ado, Jake Ross.<br />

-hannah halland, art editor and ryan casas, website editor<br />

AI: We noticed right off the bat that you had a very particular tone of voice in your<br />

writing. Can you give us a little information about how you developed that voice?<br />

Have you always been set in your style and known that was your voice? Or did it take<br />

time to develop?<br />

JR: Everyone likes to talk as if they understand it, but the concept of<br />

“voice” is pretty elusive. My teacher defines it as “a stew of everything a<br />

writer has read.” I have no idea how to describe my voice, but my advice<br />

to anyone trying to develop one would be this: read a lot, but read what<br />

you know is good. When a famous writer says, “I used to read anything<br />

I could get my hands on,” I don’t believe him for a hot second. What was<br />

he reading? Travel brochures? Dr. Seuss? Twilight? If someone stewed<br />

those together and wrote a novel, I wouldn’t want to read it. Surely, to<br />

develop a respectable voice, you have to focus on quality literature.<br />

Tone, in comparison, is simple. When I start writing something, I<br />

think: Would anyone take this situation seriously? If so, I forget about<br />

punch lines and tell the story. If not, I work in some humor. I switch<br />

back and forth, but I do get a kick out of making someone laugh. Besides,<br />

a good joke can make people pay attention. They want another joke.<br />

Even if you don’t give it to them, even if your story or essay ends on a<br />

serious note, at least they’ve paid attention.<br />

30

AI: What are some techniques you use to develop plots and characters in your short<br />

stories?<br />

JR: I revise constantly as I write, because I’m always asking myself<br />

questions. How would he describe this? How would she react to that?<br />

Whenever possible, I take out something generic and replace it with<br />

something unique. I was almost laughed out of the writing room when<br />

someone looked over my shoulder and read the first line of Worker Bee,<br />

but eventually everyone understood that I was writing the way my narrator<br />

might talk. I imagined this sexually repressed country boy who<br />

was still humble enough to devote his entire life to an undeserving girl.<br />

It was fun. I got to use those weird colloquialisms.<br />

Again with my teacher. He quotes James Joyce: “A writer should<br />

know how much change a character has in his pockets.” I think this is a<br />

little ridiculous – after all, I keep my change in a jar on my desk. And I<br />

firmly believe the penny should be taken out of circulation. The nickel<br />

could be the lowest denomination if we changed the pricing system a<br />