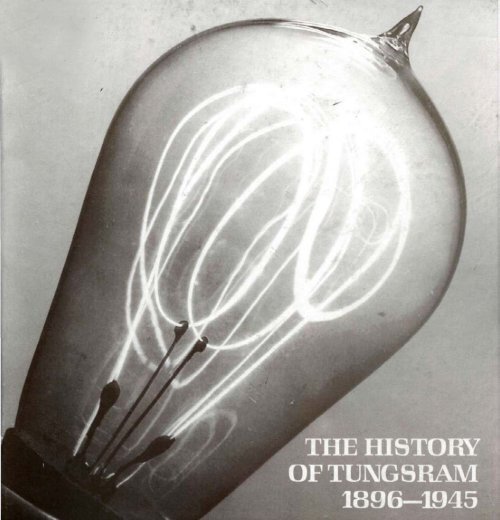

THE HISTORY OF TUNGSRAM 1896-1945 - MEK

THE HISTORY OF TUNGSRAM 1896-1945 - MEK

THE HISTORY OF TUNGSRAM 1896-1945 - MEK

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

X'H-^v•c•-,-x.>W.,r•»••.- "^ »•.,..,^^"V-T*'' >--. V*- - . . ^ _ . , . • • » ' . • - '

<strong>THE</strong> <strong>HISTORY</strong><strong>OF</strong> <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong><strong>1896</strong>-<strong>1945</strong>) ' •1990

. * • . • • * - "BASED ON <strong>THE</strong> HUNGARIAN ISSUE WRITTEN BY..^KarolyJenev^ (parti, <strong>1896</strong>-1919)Ferenc Caspar (part 2,1919-<strong>1945</strong>)'-'v.'•',•-. r^- •.•;.< ^ . ^ 'V/. •/,Commissioned by:History Committee ofTUNSRAM Co. LimitedG^ZA KADLECOVITS•"(*•.\Edited by:DR. ISTVAN HARKAYEnglish translation:ERWINDUNAYv-^KOHYV^jJARB2.-•*'•Printing: Printed in Gutenberg Printing House, Hungary (90/166).Manager: Laszio OvariLimited Edition not for sale, for private circulation only• -"4-

^...^History Committee of <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> Co. Ltd., feeling its responsibility in exploring,conserving and fostering the Company's past traditions, decided to publish theCompany's history.The present Volume embraces events since early days until the end of World War II.Of course, no completeness can be aimed at as no comprehensive authentic social,historical and industrial background can be represented; this would go well beyondour scope.A preliminary remark seems to be inevitable on the Company's name. For sake ofsimplicity, we call us <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>, although it was in those times merely theCompany's well-known main trade mark, registered in the year 1909 and assumed asstyle but as late as the 1st January 1989.Our intention is to enable all those to appreciate our achievements, who havewitnessed and shared the Company's efforts and successes and continue tocollaborate.Our firm conviction is, that the present is better understood and the establishment ofthe future is confirmed by the revelation of our past..V:, '••-•• , TV .--.• • • • -r • • >History Committee of <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> Co. Ltd.... • V-

• . ; . ^ •>(•'' % •^ i-^J-:

<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong><strong>THE</strong> ROLE <strong>OF</strong> <strong>THE</strong> EGGER FAMILY IN ESTABLISHING<strong>THE</strong> ELECTRICAL INDUSTRY IN HUNGARYOn 1 August, <strong>1896</strong> the United Incandescent Lamps andElectrical Co. (Egyesult Izzolampa es Villamossagi Rt.)was established as a joint venture of the HungarianCommercial Bank of Pest (Pesti Magyar KereskedelmiBank) and the Egger brothers. For decades the companywas known home and abroad by and large by thisname with some irrelevant — and temporary — modificationsmeaning nothing for readers. Therefore wehave chosen from the variation in question the use ofthe present new and short name of the company, the"<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>", this initial letter coinage, otherwisethe trademark of the company since 1909. This is theexcuse of the transfer of this name into the past, andalso the title of this study: The History of <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>.In effect, the United Incandescent... or according tothe above the <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> secured the financial backingof the bankers for the industry in which membersof the Egger family had been actively involved forseveral decades through various enterprises aimed atfounding and developing the electrical industry inHungary.We know very little of the Eggers' background. Itseems certain that they were of Hungarian stock. Thereis evidence showing that Bernat Bela Egger, who wasthe first in the family to get involved in the electricalindustry, had been born in Gyongyos, although othersources suggest Obuda. In any case, he must havebeen still very young when he founded the factory inVienna, known as "Telegraphen-Bauanstalt", producingtelegraph equipment as early as 1862. (1)In 1872 Bernat Egger, encouraged both by the successof his Viennese firm and the spreading use of telegraphsin Hungary, decided to set up a workshop inBudapest specialized in repairing telegraph equipment.The workshop that was located at 9 DorottyaStreet, 5th District, employed eight workers at first. (2)The enterprise immediately proved prosperous, andwithin a few years its work-force multiplied.On 31 December, 1874 Bernat Egger, "Viennese industrialistproducing telegraph equipment", was givenpermission from the 5th District to set up his ownbusiness, (3) and subsequently, on 4September, 1876,he had his branch of telegraph equipment workshoplisted in the trade registry of Budapest. (4) On 1January, 1882 Telegraphen-Bauansalt of Vienna wastransformed into a public company under the newname Austro-Hungarian Electrical Lighting and PowerTransmission Factory, with the engineer Janos Kremenetzky,Bernat Egger, Jakab Egger, Henrik EggerVienna-, and David Egger Budapest residents asfounding members. Within a year Janos Krementzkyleft the firm and went on to found his own electricalcompany. (5)The Viennese public company gave continuous supportto its Budapest branch that, beside carrying outtelegraph repair work, also made pneumatic bells,telegraph equipment, electrical indicators, and had theexclusive right to produce the Berliner-type microphone.The first telephone manufactured in the Budapestworkshop came out in 1884. (6)In 1883 the company signed on Jozsef Pinter astechnical director, who later proved to be a great assetwhen first the Egger factories and then the<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> were on their way to become largecorporations.In 1895 the company, that was known for short asEgger B. esTarsa (B. Egger& Co.), had great success inthe national trade exhibition of Budapest with itspavilon showing electrical appliances.Egger B. & Co. together with "Ganz" (another factory

<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>in Budapest, producing electrical appliances) providedthe street lights all over the exhibition area, as well asinside the buildings and along Stefania Street andNagykorond. The Eggers' company delivered 18 arclamps, each with a luminous intensity of 800 candela,and 100 electrical light bulbs, all produced in theViennese factory. (7) The jury awarded the Budapestbranch with a medal for "new invention, good qualityand progress". (8)Shortly the workshop in Dorottya Street proved to betoo small and stood in the way of progress. The^ management of the company began to look for a newlocation. In 1887 they purchased the industrial estateof 7 Huszar Street, 7th District from Hungarian GeneralCredit Bank for 56,000 Forint. At the same time, theauthorities gave permission to the four Egger brothersand David Egger's son, Gyula to establish an electricalcompany, provided that the running of the firm wasleft to the technical director, Jozsef Pinter. (9)Production in the new factory began on 1 October,1887. The total cost of the equipment amounted to40,000 Forints. The introduction of the technology toproduce incandescent lamps was an importantmilestone in the history of the company. In the beginningboth the Mechanical and the Lamp ManufacturingDepartments were located in the same building. In thefront section of the L-shaped one-storey block were theoffices, the drafting- and showrooms, the warehouseand the Mechanical Department, while the LampManufacturing Department was in the back. The machinerywas powered by an 18-20 h.p. horizontallymounted steam-engine with a Mayer-type drivingwheel. The Lamp Manufacturing Department occupieda considerably larger area than the MechanicalDepartment did. The first phase of the incandescentlamp production was the glass-blowing.The glass-blowers manufactured the bulbs from Thuringianglass tubes. They were also the ones whosoldered on the carbon filaments. There were fourblowing benches for this purpose. From here thelamps were taken to the pump chamber where 22mercury pumps were working. The lamps were testedin a separate room. The carbon filaments were also-.*.-.vproduced by the factory. In order to extract its saltcontent, the organic fibre was first soaked in water andthen heated in vacuum. After the evaporation of waterthe residue, being rich in carbon, could conduct electricity.The measurement room completed the Lamp ManufacturingDepartment. (10) The shape of the carbonfilament lamps resembled a pear; their luminousefficiency did not reach 1/6th of that of today's averageincandescent lamps or 1/1^h of the Im/W of thedischarge lamps.In the production of incandescent lamps the Eggers'company came before Switzerland, France and England.As far as Austria was concerned, Janos Kremenetzky'sViennese factory started producing incandescentlamps using carbon filament in 1884.In 1888 there were 80-100 incandescent lamps manufactureddaily in the Huszar Street. In spite of the lowproductivity and the primitive production methods,the factory soon operated with a satisfactory profitmargin,thanks to the high prices thatthe incandescentlamps fetched in those days, as the company faced nocompetition in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. (12)Egger B. & Co., mechanical and electrical factory wasrun by the technical director Jozsef Pinter. Anotherdirector, Gyula Egger was in charge of marketing. Inaddition, the company employed six clerks in technical,commercial and administrative functions. Thetotal work-force was 41 workers, including six Germanglass-blowers. To secure the continuous supply ofskilled workers, the company also employed fiveapprentices.Again, the facilities in the Huszar Street factory soonproved restrictive. For this reason, on 7 January, 1889the company bought the neighbouring houses at 12-16Munkas Street.Concurrently, the owners of the company decided towiden the foundations of the incandescent lamp productionby purchasing the patents of the Berlin factoryAllgemeine Elektrizitatsgesellschaft. (General ElectricCo. Berlin)From similar considerations, on 1 February, 1889 thecompany converted its Lamp Manufacturing Depart-

TUNGSRANment into a separate company called Electrical IncandescentLannps Co. Ltd. (with an initial equity of400.000 Forint). For the time being, the separation ofthe Lamp Manufacturing Departmentwasonlyformal.The shareholders of the new company came from theinsiders of the First-Austro-Hungarian Electric Lightingand Power Transmitting Factory. Bela Egger, GyulaEgger, Antal Deutsch and Hans Roeder were on theboard of directors.The Eggers wanted to continue with the incandescentlamp production on a different location, and for thispurpose they purchased a separate property to thenorth of the former confines of Budapest, in the vicinityof the outer Vaci Road of the present district IV. of thecapital. However, they had to abandon their plans tobuild up the factory there, because water was notavailable in the necessary quantity on the property.The Incandescent Lamp factory, after reaching anagreement with the Capital Waterworks in the matterof water supply, stayed in the Huszar Street, whichwent through important alterations and extension.(13) The Incandescent Lamp factory was housed in aone-, and a two-storey building. Jozsef Pinter andGyula Egger continued to manage the factories. Thefactory employed one engineer in the position ofproduction supervisor, one accountant, one warehousemanager, one trainee, one supervisor womanfor the two unskilled female labourers and one Germanglass-blower foreman.The total work-force came to 50 labourers: 12 peopleoperating the mercury pumps, 8 glass-blowers and 30unskilled workers. Skilled workers were well-paid ingeneral. The glass-blowers and the foreman earnedthe same as the production supervisor: 1,200 Forintsper annum, while an unskilled labourer took home 240Forints a year. The working hours were between 7 and12 a.m. and 1:30 and 6:30 p.m. (14)The company was soon given government subsidy tohelp the industry settle in Hungary.On 12 March, 1889 the Ministry of Agriculture, Industryand Commerce — while reserving its right for individualassessment, awarded The Electric Incandescent LampFactory Ltd. with provisional government privileges.After much experimentation and substantial investmentthecompany succeeded in producing carbon-filamentincandescent lamps which stood up to thecompetition on the foreign market, and also, one thatshowed an appropriate luminous efficiency as well asan acceptable useful life. The home market was stillvery small, therefore export had a high priority on thecompany's marketing policy, although the high customduties and the costs of transportation had anunfavourable effect. The Eggers worked very hard toappear on the international market. In 1889 theyexported 21,420 electric incandescent lamps 70,210lamps were exported in 1890; 190,972 lamps in1891; 220,608 lamps in 1892 and 401,318 lamps in1893.The company even had business interests as far asAsia, America and Australia. It set up warehouses inMelbourne and Montreal with commissioned goods.(16) However, newer and newer competitors appearedon the international market, and the price of incandescentlamps kept falling.While in the first year of the company's life theincandescent lamps fetched 1 Forint and 5 krajcars, in1894 the market price already fluctuated between 36and 38 krajcars. In order to facilitate the home consumption,the company asked the Ministry of Commerceto instruct the commercial and industrial chambersto advertise the factory's products among theowners of factories and industrial estates. (17) Theminister, however, refused to comply with the request,although he admitted that only the Eggers were producingincandescent lamps in Hungary. But he alsopointed out that the firm was selling generators manufacturedin Vienna, even though a Hungarian company,Ganz also produced them. The Minister notifiedthe company that he regarded the Austrian import ofgenerators, needed for the use of incandescent lamps,damaging — not only to Ganz, but to the whole ofHungarian industry. (18) Since the home consumptionof incandescent lamps could only be boosted marginally,the company was forced to increase its exportwith a simultaneous increase in the volume of production,so that the falling prices could be offset with a

<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>•.V8reduction in the production costs. This strategy on thepart of the Electric Incandescent Lamp Ltd. can beillustrated with the following business figures: (19):^:fiscalyearno. oflampsproduced(lamps)dailyproduction(lamps)production.costs(krajcar)*lampmarketprice(krajcar)lamp1889/901890/911891/921892/931893/941894/951895/96<strong>1896</strong>/97120,000166,000309,000350,000520,000752,000882,0001163,0003003501000115017002500300040001167560443628262410562684438383634.5*100 krajcar was = 1 koronaWhile the annual volume of production grew almosttenfold in eight years, the work-force only tripledduring the same time. The number of skilled workershardly changed, but the female work-force increasedfrom 30 to 140. The total work-force in 1894-1895 was200. (20)The First-Austo-Hungarian Electric Lighting and PowerTransmitting Factory continued to produce weak-currentelectrical appliances parallel with the Electricincandescent Lamp Factory Ltd. within a narrowerrange. The Mechanical Department employed 30—50workers on a regular basis. Postal and TelegraphOffice (P.T.O) was one of their regular customers. In1895 the Department specialized in manufacturingmultiplex relay boxes. The P.T.O had previously orderedsuch machinery from Antwerp.The Mechanical Department built a multiplex relaysystem handling 600 customers on the occasion of theMilleneum Exhibition. (21)

<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong><strong>THE</strong> FLOATING<strong>OF</strong> <strong>THE</strong> UNITED INCANDESCENT LAMPAND ELECTRICAL CO. LTD AND <strong>THE</strong> FINANCIALBACKING <strong>OF</strong> <strong>THE</strong> BANKSIn 1895 the capital resources of the public companyEgger B. & Co. already proved insufficient for maintainingand increasing the standard of production. Whenthe managing director, Gyula Egger described thecompany's financial problems to the director of the"Hungarian Commercial Bank" of Pest he also pointedout that "they could not respond to several businessproposals, exactly because they had to ensure that theabsolute mobility of their capital is preserved". (22)The Egger brothers understood that the only way toremain competitive in the electrical business was tohave sufficient working capital at their disposal, and tobe able to further invest continuously. For this reasonthey drew up an agreement with The HungarianCommercial Bank of Pest in July <strong>1896</strong> that they wouldmerge the Budapest and the Viennese factories of theFirst Austro-HungarianElectric Lighting and PowerTransmitting Factory to form a public company. Theydid not choose Commercial Bank by chance; they hadbeen using the services of the Commercial Bank inconnection with every financial transaction of thepublic company.It was always this bank which put up the necessary bailon behalf of Egger B. & Co. all the transport tenderstowards Postal and Telegraph Office and MAV (HungarianNational Railways). (23)The United Incandescent Lamp and Electric Co. Ltd.held its statutory meeting in the conference chamberof The Commercial Bank on 1 August, <strong>1896</strong>. Egger B. &Co. contributed to the funds of the public companywith their Viennese and Budapest factories, buildings,machinery, goods, raw materials, debits and claims.The Electrical Incandescent Factory Ltd. retained itsindependence for the time being. For the above assets,estimated to be worth 600,000 Forints, the Eggerfamily received 6,000 shares in 100 Forint denominations.The total equity came to 1,400,000 Forints, and theCommercial Bank bought up 33 percent of the shares.They were syndicated by the Egger brothers and byCommercial Bank. The bank was represented by threedirectors on the board, and the Eggers delegated five.The new company was effectually controlled by theCommercial Bank, whose representatives had theright to veto any decision. The company was obligedto have all the planned investments costing more than10,000 Forints and all the business deals worth over60,000 Forints countersigned by the bank, whoseagreement was also needed for the employment ofany new executive with an annual salary over 6,000Forints.On the statutory meeting Jeno Szabo, member of theHungarian Upper House, Ferenc E. Vas, deputy directorof the Commercial Bank, Peter Maishirn, retiredrailway superintendent. Dr. Izidor Deutsch, lawyer,Bela Egger, David Egger, Gyula Egger and Jakab Eggerwere elected to the board of directors. (24)In accordance with the agreement drawn up with theCommercial Bank, the new public company decided torespect the five-year contracts signed with Bela Egger,

<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> 10Erno Egger, David Egger and Moric Deutsch. BetaEgger received from the Viennese factory an annualsalary of 12,000 Forints, plus a company flat withelectricity and heating paid for. David Egger drew anannual sum of 7,000 Forints from the Budapest factory.The engineer Erno Egger continued to be employed bythe Viennese factory. (25)Pressed by the rising shortage of capital, on 30 June,<strong>1896</strong> the Electric Incandescent Lamp Factory Ltd.merged into the United Electric Ltd. In connection withthe fusion the equity of the company was raised to1,650,000 Forints. The transaction was, again, conductedby Commercial Bank, whose interests this wayreached 37 and a half percent. (26)The backing of the banks made it possible for thecompany to upgrade all its branches, first of all, itsLamp Manufacturing Department. The demand forincandescent lamps continuously grew with thespreading use of electric light. The profitability of itsproduction also increased, although the competitiondrove the prices further down every day.The company counteracted this phenomenon by increasingthe volume of production: it manufactured5,000 lamps a day in the fiscal year 1897/98; in 1898/99its daily output already reached 7500. (27)Since the turnover of the Huszar Street plant went upby 30 percent on average every year, the structure ofthe Lamp Manufacturing Department needed thoroughchanges in order to facilitate the continuousupgrading of production. The spreading use of electriclighting suggested a continuously growing demand.At the same time, the prices of incandescent lampskept falling, so that the incandescent lamp industrywould only yield a profit, if mass-production wasachieved. Those factories that were unable to increasetheir output constantly, could not keep up with theircompetitors. The demand was primarily met by thecompetitive producers, who found their market growing.In spiteof all this, new incandescent lamp factorieshardly emerged. The fact that the training of theworkers required a lot of time, patience and money,must have contributed to this.By the turn of the century the existing conditions in theUnited Incandescent Lamp and Electrical Co. that isfrom here <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> did not really allow any furtherincrease in the volume of production. By squeezing upthe work stations — in the opinion of the technicaldirector Jozsef Pinter — daily production could havebeen pushed up to about 10,000 bulbs. This, however,would have probably resulted in the slackening ofquality control, and in rising production costs andbreakage.The useful area of the Lamp Manufacturing Departmentdid not exceed 3,100 m^, and the daily productionof 10,000 lamps would have required at least5,300m^. Every argument suggested that the upgradingof the Lamp Manufacturing Department wouldhave to be realized on a new location. (28)The company also faced difficulties of technologicalnature, since the carbon-filament bulbs did not standup very well to transportation. The technical managementwas relentlessly working on improving the qualityof the incandescent lamps, perfecting productiontechnology and economization.The lack of space affected the Mechanical Department,too. It could just about fulfil the orders of telegraphequipment and telephones, but there was not muchscope for improving the Department as a whole. Thiscaused some concern in the management, since theweak point of the Mechanical Department was preciselythat it very much relied on government orders.(29)Beside manufacturing incandescent lamps TUNGSRAM could boost with considerable success in producingtelephones and installing telephone exchanges.The license agreement, which was drawn up between<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> and Western Electric Company of Chicagoin 1899, played an important part in this. On thebasis of the licence agreement, the world-famousAmerican company — a leading force in the telephonebusiness — made its licenced products available to theBudapest public. (30)The "common battery"-type telephone equipmentfound favour with the Hungarian experts, too.In 1900, when Postal and Telegraph Office put out totender the producing and installing of the equipment

11 <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>of its telephone exchange in the Nagymezo Street(Budapest), on the basisof the jury's recommendationand out of seven applicants, the job was given to thejoint entry of <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>, and Western Electric Company.That was, in fact, the first instance that Hungarianindustry took an active part in the construction ofthe telephone exchange system in or outside Budapest.Western Electric Company vouched for the workof its Hungarian partner Central Telephone Exhange"Terez" Budapest, one of Europe's first commonbatterytype telephone exchange, was built as part ofthis order. (31)In 1899 a new section was added to the MechanicDepartment which specialized in producing securitysystems for the railway. Again, this work was hinderedby the lack of space, so production, for the time being,began in the near-by 6voda Street, neighbouring theHuszar Street plant. When MAV (Hungarian State Railway)decided to change its remote-controlled semaphores,the company was given the lion's share of the work.The new section working of the Mechanical Departmentfirst of all enhanced the company's reputation bybuilding power-plants. At the turn of the century itdelivered and installed power-stations in Szatmar,Sopron, Kapronca, Budafok and Losonc.The power generators in Budafok and Losonc werebuilt on behalf of Budafoki Villamossagi Rt. (BudafokElectric Co. Ltd.) and Losonci Klara Villamossagi Rt.(Klara Losonci Electric Co. Ltd.); in both cases,however, the majority of the shares was in the hands of<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>.The Budafok Power Plant was put into operation on1 May, 1898. By then Budafok, near Budapest with its 30large and more than 200 smaller wine producers wasconsidered the centre of the Hungarian wine industry.The power plant first of all served to deliver electricalenergy to the wine companies. The drawing of wine,previously done with manpower now was carried outusing electrical energy. (32)The Losonc power plant began to operate on 6 December,1899. Both electrical companies were bringingconsiderable profit for <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> for several years.(33)The heavy-current goods section started to producegenerators and electrical engines in 1899, as the TradeMinistry promised to grant the company with specialprivileges pending on this. Although electrical engineproduction also served to alleviate the strain on theViennese factory, the company could only managethat with a great deal of difficulty, since the chosenlocation automatically excluded the possibility of astep-by-step upgrading later.The Budapest and the Viennese factories of TUNGSRAM played a leading part in the electrical industry ofthe Austro-Hungarian Empire at the turn of the century.The favourable reception of its products on the MilleneumExhibition, where the company had a separatepavilion showing telegraph and telephone equipmentand incandescent lamps, further enhanced the company'sreputation. (34) <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> was representedon the World Fair of Paris in 1900, too, but hereconsiderable business deals did not follow theprofessional recognition of the industry. (35)Nevertheless, the company's exports grew significantlyin this period. On his business trips, the chiefexecutive officer of the company, Gyula Egger establishedsales agencies in London and Paris. He primarilymanaged to find market for the light-current productsthis way. The company increased the export of itsincandescent lamps year after year, as evidenced bythe dispatch notes: the gross weight of the exportedincandescent lamps was 70 tons in 1897, 88.5 tons in1898 and 117.7 tons in 1899. The growing export, byimplication, also suggested the good quality of theproducts. The 35 tons of incandescent lamps importedannualy to Hungary gave, however, less cause forrejoicing. (36) ^ .The work-force of the Huszar Street plant grew parallelwith the development of the Departments. Accordingto the report of the District Industry Superintendent ofBudapest, made on 13 April, 1899, the total work-forceof 593 broke down as follows:*/*"^'->

<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>•>,^12marketing staff male 18 female 10technical staff male 12other staff male 6 female 22foremen male 10errand boys • male 5adultworkers male214 female255day-workers male 6apprentices on contract male 36By early 1900 the number of female staff employed inthe incandescent lamp production already reached350. (37) The workers were all members of the HealthInsurance Scheme. The company insured all its workersagainst accidents with (Nemzeti BalesetbiztositoTarsasag) National Insurance Company, nevertheless,it did not have its own doctor or surgery. The companydid not provide accommodation to its workers, either;on the other hand, staff with long time of servicereceived bonuses every year.Not that the company couldn't afford to put somemoney aside for the workers' welfare, either: theBudapest factory closed the fiscal year of <strong>1896</strong>/97 witha net profit of 155,293 Forints; that grew to 202,622Forints in 1897/98, 198,493 Forints in 1898/99, 413,490Koronas in 1899/1900 and dropped back to 326,379Koronas in 1900/1901. The shareholders received1.074,000 Koronas. The company did not even have topay taxes after its net profits, either, since the governmentsspecial privileges exempted it from texation fora long time. (38)On 1 June, 1899 the Egger family, on the initiative of itsViennese members and assisted by Commercial Bankand Niederosterreichische Escompte-Gesellschaft, agreedto form the Viennese factory into a separatepublic company under the new name of VereinigteElektrizitats-AG, (United Electricity Ltd.), with an equityof 2.000.000 Forints.The new company, VEAG handed over shares worth1,000,000 Forints to <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> Rt. in return for theViennese factory. The engineer Erno Egger acted aschief executive officer of the Viennese factory. (39)<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> and VEAG continued to maintain a closeassociation: they signed a contract mutually agreeingto exchange new inventions and patents, to make useof each others' stocks in their material acquisitions asmuch as possible, and to set up joint sales agencies.They also agreed that the Viennese factory wouldproduce heavy-current goods, heavy-power-currentgenerators, electric engines, transformers, elevators,machine-tools, electric automobiles and railway securitysystems —, while the Budapest plant would concentrateon electric light bulbs, telegraph and telephoneequipment, telephone exchanges, railway securitysystems, light-current generators and parts forelectrical appliances. Both companies promised thatthey would advise each other on any large businessdeals and speculations. (40) To facilitate the smoothcooperation, top officials of the Commercial Bank wereappointed to the board of directors of the Austriancompany, the same way as top executives of NiederosterreichischeEscompte-Gesellschaft were made directorsof <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>. The Austrian bank's interestswere represented in Budapest by Moric Birkenau andMiksa Krassny, as directors. Kereskedelmi Bank receiveda bonus of 259,000 Koronas for restructuring theViennese factory into a public company. (41). r-»*•• . • If •Kv>«

13 <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong><strong>THE</strong> BUILDING<strong>OF</strong> <strong>THE</strong> UJPEST PLANT AND <strong>THE</strong> FIRSTFEW YEARS <strong>THE</strong>REAs we have already pointed out, the Huszar Streetplant did not allowthe expansion of the Mechanical orthe Lamp Manufacturing Department. For this reason,in the spring of 1899 the company's managementdecided to build a new factory. They first notified theTrade Ministry in July 1899, giving their reasons in that<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> could only complete against the unlimitedresources of the German telephone and incandescentlamp industry, if the company increased thevolume of its production. (42) To be able to do that theywould definitely need to build a new plant with threetimes the capacity of the present one. Naturally, thehuge investment would bring about a temporarydecline in the company's performance, especially,since in the beginning production would take place ontwo separate locations. The management asked theMinister to continue with the special governmentprivileges given to facilitate the production of telephonesand electric incandescent lamps until the end ofthe term laid down in legislation, and to exempt thecompany from taxation for 15 years.In answering the company's application, the TradeMinistry suggested that the new factory be built in theoutskirts of Budapest, rather than inside its boundaries,and in that case the government privilegeswould be forthcoming for the maximum time period(43)Before making its final decision, the managementcalled on Richard Englander, lecturer of the VienneseTechnical College, to make a careful assessment of theHuszar Street plant from the viewpoint of fire hazard,together with a feasibility study on its enlargement.Mr. Englander completed this task and after surveyingthe site he came to the conclusion that the factorycould not stay in Huszar Street. "In the interest of theeconomy of production, the building of a new plant isadvised." On 11 October, 1899 — on the basis ofEnglander's expert opinion — the board of directorsauthorized the executive committee to purchase a siteof about 8—10,000 square-fathoms (1' fathom' == 38.32 square foot). (44)In order to purchase a site, the executive committeefirst looked around within the boundaries of Budapest.The liquor producer Vilmos Leipziger offered a plot ofland for sale in Obuda, right on the banks of the RiverDanube, which seemed suitable for the purpose. Aftercareful consideration, however, the managing directorsdecided against purchasing the land, because theamount of necessary groundwork would have significantlyadded to the price. (45)In the meantime, the Trade Ministry's response to thecompany's application arrived: <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> would begiven special government privileges for 15 yearsbeginning on the first day of production, if it was tobuild a new plant for producing incandescent lampsand weak-current products in or around Budapest. Theoffer was made, however, on the condition that thecompany would abolish the old plant, invest 600,000Forints in the new factory, provide work for 1,200workers from the first day of production, and wouldmake arrangements for the production of 25,000 incandescentlamps a day.Moreover, the Ministry obliged the company to producecarbon electrodes and set the deadline for thestart of production by the end of 1900. (46)After hearing the Trade Ministry's favourable decision.

<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> 14the board of directors dismissed the idea of buying asite inside Budapest, and on 28 January, 1900 theypurchased a 13,500 'fathom' (that is: 13.5X13.500square foot) property in Ujpest from the land magnateDr. Sandor Karolyi. Of the 182,250 Korona price<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> paid out 82,250 Koronas at the time ofexchanging the contract, and they were given threeyears to pay the remaining 100,000 Koronas. (47)At the turn of the century Ujpest, with its 41,858inhabitants, its handicrafts prospering and its industryshaping up, was considered the most thriving suburbof Budapest.When in early 1900 <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> bought its presentsite, the property was surrounded by the Karolyifamily's entailed estate of Fot, only interrupted atplaces by the sites of the Capital Waterworks. The firstHungarian railway line connecting Budapest and Vachad been crossing the estate since 1846. Since 1869there had been a horse-driven omnibus service betweenMegyer (a part of Ujpest) and Calvin Square (inthe centre of Budapest). (48)On 3 February, 1900 the management of the companynotified the town officials of Ujpest of the company'sintention to build an electrical factory in the area withan investment of 2,000,000 Koronas, provided thatadequate conditions could be guaranteed. By movingto Ujpest from the country's industrial and tradecentre, the company would take on considerableamount of difficulties.In return, the management asked the civic authoritiesto extend the sewage system, the waterworks, thebitumen pavement and the street-lights all the way tothe plant, and to deliver, free of charge, the amount ofearth and sand needed to complete the groundwork.Simultaneously, the management announced that, forthe time being, the company did no intend to buildhouses for its employees, hence giving a boost to thelocal house market. On the procurement of the Ujpestleather manufacturer Tivadar Wolfner — who was oneof the most enthusiastic supporters and initiators ofthe idea to build an electrical factory in Ujpest — thetown officials agreed tocomply with the request of themanagement. They even topped this by waiving thecompany's property taxes and other duties for thesame period that the government privileges ran. (49)When the board of directors met on 10 February 1900,they instructed the executive committee to have theplans of the factory ready by the middle of March. Thechief executive officer Gyula Egger, Peter Maishirn,member of the board, and the technical director JozsefPinter were delegated to make the necessary arrangementsfor the construction work and to coordinata thewhole project. As experts the chief executive officer ofthe Viennese factory VEAG, Erno Egger, and ProfessorRichard Englander were invited. (50)The plans were discussed by the construction committeeon a meeting held in Vienna on 10 April, 1900. Onthis occasion the board members Ferenc E. Vas andMiksa Krassny wanted to know the reasons behind theproposed increases in capacity, aiming at 25,000 incandescentlamps a day, or, in the case of the MechanicalDepartment, at doubling the performance.The technical director, Jozsef Pinter quoted past years'business figures to illustrate the reality of a productionboom: the company received orders for 582,000 incandescentlamps in the fiscal year 1894/1893. Thisnumber grew to 1,224,000 lamps in 1898/1898, to1,600,000 lamps in 1898/1899, and to 2,300,000 in .^-1899/1900. From the constantly growing demand itcould be rightly anticipated that for the fiscal year1902/1903 there would be orders for 6,000,000 incandescentlamps, which, in turn, would require theproduction of 22,000 lamps a day. Mr. Pinter alsopointed out that, while in 1899/1900 the production ofa single incandescent lamp cost 16 krajcars, manufacturing25,000 lamps a day would reduce this figure to13,5 krajcars. It became apparent that the drop in theprice of the lamps could only be offset by the continuousincrease of the volume of production. Bela Eggerwas against the plans that had been put forward.Professor Englander adopted them. Finally, the constructioncommittee accepted the proposed plans. (51)Since purchasing the land as well as completing andaccepting the plans took longer than expected, theTrade Ministry extended the previously set deadlinefor completion of the Ujpest plant until the end of 1900,

15 <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>while the date set for the start of production waspostponed until the spring of 1901. The Ministry,lobbied by the company's influential supporters, alsoagreed to nnodify its initial conditions, and to give timeto the company until the third year of operation beforereaching the originally fixed works-force. (52)After receiving the building permitted on 30 June,1900, the board of appointed directors signed a dealwith the building contractors Sandor and Gyula Wellisch.The executive committee instructed GyulaEgger, Jozsef Pinter and Richard Englander to orderthe necessary machinery and sign the relevant agreements.(53)By late September, 1900 the construction work advancedto the point that first cost analysis could bedrawn.On an extraordinary general meeting held on 5 October,1900 the shareholders raised the company'sequity from 2,000,000 to 3,000,000 Koronas to coverthe building and equipment costs of the new factory.(54)In the course of the construction work several alterationswere necessitated on the plans, and even somenew requirements emerged. Hence, it was decidedfollowing the request of Postal- and Telegraph Office,that there would be a post and telegraph office withinthe area of the new factory, and that the post masterwould get free accommodation in the building. (55)The Mechanical Department received an additionalwing which had not been in the original plan, in orderto be able to build telephone exchange systems accordingto schedule. By the way, the anticipatedincrease in the export of weak-current goods alsonecessitated the enlargement of the building. (56)The construction work on the new factory was finishedin the Summer of 1901. By mid-July the installation ofthe machinery advanced to such a stage that LangMachine Works, which delivered the machinery forthepower plant, was able to hold its first trial runs. Thequestion of water supply was also resolved favourable:no pressure drops were registered at the wells.The gasworks were put into operation by the end ofAugust, and the incandescent lamp production couldcommence. A few weeks later the Mechanical Departmentmoved into its new premises. (57) The buildingand equipment costs exceeded the planned sum byhalf a million Koronas and the total amount reached2,563,719 Koronas. The building contractors received1,006,480 Koronas. The mechanical machinery costed141,000 Koronas, the electric equipment 97,000 thevacuum device 23,000 the boiler 60,000 the gasworks74,000, the pavement 16,000 and the various fittings174,000 Koronas. (58)By the end of 1901 the new factory was working withfull capacity and the board of directors, therefore,missed the deadline set by the Ministry of Trade onlyby one year. The start of production of the carbonelectrodes necessary for the arc lamps ran into problems,and the company asked the Ministry to extendthe deadline. The Ministry agreed to put off thedeadline until the end of 1902. The board of directors,however, wanted to rid themselves of this obligationaltogether, and finally achieved that the Trade Ministry,lobbied by the directors of Kereskedelmi Bank,changed the terms of the previous agreement. Insteadof carbon electrodes, now the company was committedto produce railway security systems. (59) -The Mechanical and the Lamp Manufacturing Departmentwere separeted very definitely in the Ujpestplant. Structurally the Mechanical Department consistedof a production hall, a production office, atelephone construction hall, a railway security systemconstruction hall, a warehouse, an accounting office, astatistical office and a marketing office. The LampManufacturing Department was made up of a glassblowing section, a photometric section, a vacuumsection, a fitting room, a sealing section (where thestems were inserted into the bulbs), a warehouse anda marketing office. Seven engineers, six draughtsmenand nine supervisors constituted the technical staff ofthe Mechanical Department, while the Lamp ManufacturingDepartment was managed by one productionmanager, one chemist and ten supervisors. (60) Themanagerial talent of Lipot Aschner was beginning toshow itself in the new factory. He was the chief clerk ofthe Lamp Manufacturing Department first, and deputy

<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>:k-^16director from 1 July, 1904. The annual salary of thechief executive officer, Gyula Egger was, 16,800Koronas then; Jozsef Pinter, technical director received15,000 Koronas and Lipot Aschner, 8,000Koronas.Jozsef Pinter's assessment proved correct when at thetime of planning the LJjpest plant he predicted that thedemand for electric light bulbs would dramaticallyincrease. It soon turned out that the Huszar Street plantcould not have possibly satisfied the rapidly growingdemand. On the other hand, the increased capacity ofthe new Lamp Manufacturing Department permittedthe marketing of 3,896,538 incandescent lamps in thefiscal year of 1902/1903, and 4,519,257 lamps in thefiscalyearof 1903/1904. (62)The market price of electric light bulbs very markedlydropped as a result of the strong competition in thefiscal year of 1902/1903. This moved the factory ownersto set up a cartel in order to end the further fall inthe prices. One of its organizers, Philipp Westphalnotified <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> in April, 1903: "The continuousdrop in the price of electric light bulbs brought aboutthe possibility of the leading European light bulbfactories coming to an agreement". (63) The incandescentlamp cartel was founded as a limited companywith an equity of 1,000,000 German Marks under thename of Verkaufsstelle der Vereinigten Gluhlampenfabriker(Central Sales Office of United IncandescentLamp Factories) in Berlin on 16 September, 1903. Thecartel members contributed to the equity according tothe quotas allocated to them which, in turn, wasdetermined on the basis of a turnover of 27.7 millionMarks. AEG and Siemens und Halske AG. received22.633 percent each, while <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> was given11.316 percent and Philips received 11.307 percent.The remaining 29.761 percent was shared between theother eight companies. The Limited Company wasrepresented by a board of seven directors, elected bythe cartel members.According to the cartel agreement, the marketing ofincandescent lamps was the responsibility of thecartel, although in the countries where no cartel memberswere operating <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> had the right to selllight bulbs up to eighty percent of its quota, eitherdirectly to users or to retailers.The incandescent lamp cartel founded in Berlin undoubtedlyeased the marketing problems of the<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>. It took over the goods up to the amountcorresponding to the company's quota for the pricefixed in the cartel agreement, marked it, and then paidout the profit. Not having to worry about marketinggave a boost to the company and allowed the radicalreorganization of its Lamp Manufacturing Department.This, in turn, led to considerable savings in theproduction costs and the establishing of new workmethods. (64)Joining the electric light bulb cartel made some of thecompany's sale offices redundant. Since the salesrepresentatives had proved their excellence in theprofession, the management continued to rely on theirservices in the interest of the other manufacturingbranches. The planned expansion in the production ofthe weak-current goods justified to keep them on thepay-roll. (65)While the question of the profitable marketing of thecarbon-filament incandescent lamps had been resolved,the quality, the luminous efficiency and thelife-time of the lamps remained to be a burningproblem.Wide-ranging research began that was aimed at raisingthe temperature of the filament. In the course ofthese researches, the lamp designed by the NobelPrize winner chemist, Walter Nertz, generated someinterest. He designed a mixture of metal-oxides to beused as filament.While he managed to raise the temperature of thefilament up to 2,350 C, the luminous intensity of thelamp exceeded that of an ordinary carbonfilamentlight bulb only by 50 percent. (66)Nertz's light bulb immediately aroused the attention of<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>'S technical staff. Af their suggestion thecompany, jointly with Ganz es Tarsa (Ganz and Associate),bought the license for the production of suchlamps within Austria-Hungary. (67) The company, withthe license in its possession, immediately ran someexperiments. In the course of these experiments it

17 <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>soon turned out that the Nertz-lamp would not renderobsolete the carbon-filament lamps, instead, the prospectsof its application seemed promising in specialareas, in respect of the relation between incandescentlamps and arc-lamps. Nevertheless, the technical expertsof <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> and Ganz & Co. continued to runexperiments on the license. (68) When in the spring of1901 the Berlin factory of AEG brought out the Nerztlamp,the license holders in Austria-Hungary decidedthat they would start the production of Nertz-lampspending on the success of AEG, even though theirresearch showed that these lamps had no commercialvalue. (69)Responding to a request from AEG, the two Hungariancompanies permitted the Berlin factory to sell itsspecially marked Nertz-lamps within the Monarchy inreturn of a ten percent license fee.This, however, did not mean that <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> or Ganz& Co. would forsake the right to produce Nertz-lamps.(70) And indeed, the two companies started producingand marketing such lamps in a limited quantity in1903; their mass-production, however, was neverrealized — partly for lack of interest, and partly forsuccesses scored in other type of experiments thatgave a different direction to the future developments.(71)The application of tungsten-filaments opened a newchapter in the evolution of incandescent lamps. Thefirst people ever to produce incandescent lamps usingtungsten filament were Dr. Sandor Just and FerencHanaman, both lecturers at the Technical College ofVienna. Their lamp had a luminous efficiency of 7.85ImAA/, which hardly dropped during its useful life of800 hours. (72) Just and Hanaman registered theirinvention on 13 December, 1904. The implications ofthe invention were unfathomable. Although in thedescription carbon filaments were still needed for theproduction of tungsten filaments, at the end the filamentwas tungsten entirely free of carbon. (73)It was probably Professor Englander, also lecturing atthe Technical College of Vienna and once acting astechnical expert in the construction of the Ujpest plant,who drew the attention of the management of<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> to the new invention. The company'smanaging directors quickly wrapped up the deal onthe priceless licence. They drew up an agreement withDr. Sandor Just and Ferenc Hanaman on 13 December,1904, according to which the inventors sold the soleright to <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> to produce and sell tungsten-filamentlamps within Hungary and Austria. The agreedlicense fee was ten percent of the billed sales.<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> accepted a ten percent interest in thefurther marketing of the license and also, committeditself to the mass-production of the tungsten-filamentlamps. (74)Several-year-long experimentation preceded themassproduction of tungsten-filament lamps. The carbon-filamentlight bulbs preserved their hegemonyduring these years: the volume of production reached25—30,000 pieces a day in the fiscal year of 1905/1906.The capacity of the Mechanical Department was alsosignificantly expanded in the new factory. The spaciouswork halls allowed the company to complete theinstallation work on the new telephone exchangesystem of Budapest by the end of 1903. The newtelephone exchange system was put into operation inJanuary, 1904. They managed to connect the morethan 6,000 existing lines to the centre in NagymezoStreet (:in the centre of Budapest:) by 15 April, and sothe former telephone exchanges in Baross Street andSzerecsen Street could be closed down. Since bymid-August, 1904 all the cross-bar lines had beenconnected to this centre, the whole telephone serviceof Budapest was concentrated in one exchange. Between1904 and 1906 the company received ordersfrom a whole list of provincial telephone exchanges toexpand their systems. They completed the telephoneexchange of Zagreb (:today Yugoslavia:) and handedit over to Postal and Telegraph Office in 1905. (75)Beside the good business done by the telephone andtelegraph section on the home front, the export of thelight-current products also increased significantly.The section manufacturing railway security systemsshowed an even more impressie expansion in capacity.The management bought up a whole list of patentsin order to secure its prospering and to be able to stay

<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> 18competitive. The patents of the Kolban-type electricrailway block system, the heavy-current railway securitysystems and the security equipment of theSouthern Railway Company of Vienna were among•; these licenses. The latter was especially important,since this way the company did not have to facecompetition from Southern Railway in doing businesswith MAV (Hung. State Railway). (76)The Hungarian factories manufacturing railway securitysystems set up a cartel in 1905 and dividedbetween themselves the production quotas. Ganz and'^ Co. received 37 percent, Roessemann and Kiihne, 33percent and United Electric Co., 30 percent. LaterTelephone Factory Ltd. also joined the cartel, whichnecessitated the revision of the quotas. According tothe new cartel agreement, Ganz and Co. was given28.49 percent, Roessemann and Kuhne, 25.41 percent. <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>, 23.1 percent and Telephone Factory Ltd.23 percent share of the market. (77)The company management paid great attention toevery patents and inventions in the electrical industry.Their interest was especially aroused by the Pollak-Virag type of telegraph, so much so that they boughtthe licence already at the turn of the century. Theinventors further improved the telegraph and added aperforator to it. This maschine differed from the ordinarytelegraphs in that it punched letters into thepaper-roll and this way the message appeared on thereceiving end as a written text. All that the telegraphistshad to do was to put the telegraph into an envelopand mail it. (78) The company spent 8,000 Koronas onthe design of the improved machine and founded apublic company with an equity of 500.000 Koronas tomarket the licence in 1903. The first successful test ofthe new telegraphic equipment was between Budapestand Fiume, and also, between Berlin and Cologne.Prolonged negotiations took place about the introductionof the Pollak-Virag-type telegraph in England,France and the United States, although this machinefailed, at the end, to live up to the expectations, sinceother, more sophisticated telegraph systems weredeveloped in the meantime. (79) The company, engrossedin the problems of developing a new incandescentlamp and enlarging its circle of weak-currentproducts, could not pay as much attention to itspower-current machinery production. On 25 November,1902 <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> managed to draw up an agreementwith its Viennese sister-company, according towhich the whole power-current industry section of theOjpest plant, complete with its stocks and orders, wastransferred to VEAG. The transaction, however, onlymeant a partial solution to the problem, since thepower current industry section continued to be operatedwithin the Ujpest factory. VEAG created a branchin Budapest factory, although it was solely operated bythe Viennese, for the Viennese. In effect, the powercurrent industry section was run on behalf of theUjpest plant, but on the risk of VEAG; <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>wanted to share neither the profits, nor the losses. (80)The Ojpest factory paid out 100,000 Koronas to VEAGfor the honouring of the existing deals, as well as forthe commercial services done abroad in the interest ofthe company.The half-measures aiming to solve the problems of thepower industry section were closely linked to thequestion of government privileges. The factory wascommitted to the production of generators and electricmotors by a deal made with the Trade Ministry. VEAG,however, bought the parts for these goods in Vienna.A sacked employee filed a report and the Ministrylaunched an inquiry in October, 1904. After the inquirythe Ministry notified the company that if the conditionswere violated, they would take retaliatory measures byreconsidering both the government privileges and thegovernment orders. On the meeting of the executivecommittee held on 31 October, 1904 the chief executiveofficer, Gyula Egger and the technical director,Jozsef Pinter strongly urged the Viennese sister companyto establish a branch for the production ofpower-current machinery in Budapest, since neitherthe work space nor the work force were available in theUjpest plant. (81) Opposing the view held by the Ojpestmanagement, the chief executive officer of the Viennesefactory, Erno Egger insisted that <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>should not change its previous practice. Since thelatter view was endorsed by the Viennese board of

19 <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>directors, the executive committee postponed thedecision. (82)As VEAG continued to ignore the development of thepower current industry section, the executive committeeput the question bacl< on the agenda in its meetingheld on 29 March, 1905. The power current industrysection could not be simply closed down, since thatwould have meant the loss of considerable governmentprivileges and orders. (The company wasexempt from taxes until the 1st November, 1916, andin 1915 it received orders from the government worthmore than 1 million Koronas which amounted to 60percent of the total business done by the MechanicalDepartment in that year.) The abandoning of thepower current industry market also threatened withthe possibility that the company's biggest clientswould go elsewhere even to buy incandescent lampsand light-current products. (83)After taking all this into consideration, Erno Eggerinformed the executive committee that VEAG wouldbuild a current industry factory within the Ujpest plantby the end of 1905, and the manufacturing of generatorsand electrical motors should begin there by the end ofJune, 1906, at the latest.The new factory had, indeed, been completed by early1906, and by the end of April it had been put intoservice. (84)The company's direct involvement in selling incandescentlamps did not come to a close with the setting upof the cartel, as it had the right, in certain countries, tomarket the carbon-filament lamps produced over itsquota. Primarily, <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> could build up its exportmarket in Russia, Spain, Japan, Canada and SouthAmerica. The company established sales offices in thecities of Yokohama, Kobe, St. Petersburg, Moscow,Madrid, Montreal and Buenos Aires. Lipot Aschnerorganized the Russian market. (85) In 1905 the companyalso set up permanent sales agencies in Paris andVienna. The running of the agency in Paris was entrustedwith the office manager Rudolf Loranti, whileIgnac Salzmann was put in charge of the Vienneseoffice. (86) The British market received the lamps andthe light-current goods of the<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> through thesales organization set up jointly with the Schwechatcompany Schiff & Co.(87)^Naturally, the construction of the current machinesection, the relocation and the gradual realization offull production all had an unfavourable effect on thecompany's business figures between 1901 and 1903.In spite of the initial difficulties of the new section, thecompany closed the year with a net profit of 145,000Koronas. Of course, this was not enough to pay outdividends. The profit grew to 269,000 Koronas between1903 and 1905, and in the fiscal year of 1905/1906it exceeded 488,000 Koronas. There was such a boomin the electrical industry that from time to time thecompany could only fulfil its orders by working overtime.The shareholders received a dividend of 540,000Koronas in the three years beginning with the fiscalyear of 1903/1904. The company's financial state becamestable: in the fiscal year of 1905/1906 the Ojpestplant and its machinery was evaluated to be worth 3.3million Koronas, and its stocks held finished goodsand raw material worth 1,6 million Koronas. Againstthe company's entire debt of 1.5 million Koronas itsclaims totalled 1.6 million Koronas. (88)In 1901 the work-force did not exceed 700; therefore,during the previous two years it only grew with abouta 100 employees. As the Trade Ministry had grantedthe factory's tax-free status on the condition that by 1November, 1904 it would employ 1,200 workers, andsince the management was unable to comply with thiscondition, it fell on Jeno Szabo, president of the board,to procure the repeal of this particular point. (89)In order to achieve a gradual reduction in the productioncosts and thus increase the profits, the managementprimarily tried to employ cheap femalelabour. At the same time, and as a result of theconstant widening of the production profile, it also hadto increase its skilled work-force. The majority of thefemale workers came from the districts around Ojpest.They still did not have any connections with the tradeunion movement for a long time to come. Most of theskilled workers, however, were already union members.The first stoppage in the Ujpest plant took place in

<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>.4-. »fe-"201905. The technical director Jozsef Pinter told theexecutive committee on 4 March, 1905 that the carpentershad threatened with strikes in case the following oftheir demands were not met.1. The company should employ a foreman, who iscompetent enough to run the carpentry workshopindependently.2. The piecework system should be abolished.3. The bottom hourly wage for carpenters, machineworkers and turners should be fixed in 40 fillers, and in24 fillers for female workers.4. Male and female workers should both receive a 25percent bonus every fortnight.5 Overtime work should be abolished. The hourlywage in case of overtime work called in exceptionalcircumstances should be raised by 50 percent if it iswithin the factory, and by 100 percent if it is outside thefactory.6. Wage penalties should be abolished.7. It is desirable that the mutual respect betweenworkers and foremen be observed.8. The company should recognize the workers' electedshop steward. , -' "•" -.9. Workers participating in a wage dispute can only belaid off in the next 6 months, if it can be proved thatthey did not report for work on their own accord.10. The labour exchange should take place throughemployment agencies.11. The work instructions should be given out by theforeman. -12. The work regulations should be displayed in theworkshop in an accessible spot. (90)The technical director, Jozsef Pinter told the workers'delegates that the management would discuss andremedy their complaints. The answer, however, didnot placate the workers. They called a meeting thatnight and decided that the 65 carpentry journeymenwould lay down the tools next morning, on 5 March.The strike ended on 17 April.The management conceded to the workers on severalpoints, and so the stoppage was not without anyresults:1. Although the piecework system stayed, the pieceratewas raised.2. The minimal hourly wage was fixed in 34 fillers.3. The management made a promise that it would pay25 percent overtime bonus in case the work endsbefore 8 o'clock p.m. in case of overtime work afterthistime, the management promised to pay a 50 percentbonus both to those working in piecework and to theday-workers.4. The management recognized the shop-stewardsystem.'.-*'•J"^\-i^

21 <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong><strong>THE</strong> INTRODUCTION <strong>OF</strong> TUNGSTEN TECHNOLOGYIN <strong>THE</strong> PRODUCTION <strong>OF</strong> INCANDESCENT LAMPS<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>'S TRANSFORMATIONINTO A LARGE CORPORATION (1906-1914)On the extraordinary general meeting held on 23 May,1906 the official designation of the Ujpest factory wasmodified to EgyesiJlt Izzolampa es Villamossagi Rt."United Incandescent Lamp and Electric Company".This is the original registered style together with itsantecedents were named, "abbreviated" for simplicity,<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>. After buying up the patent of Justand Hanaman's invention, the company spent morethan a year trying to perfect the production technologyof tungsten lamps. (91) The two inventors themselvesparticipated in the experiments, in the course of whichseveral problems arose. In essence, tungsten wasextracted in glowing gas from tungsten-hexachlorideonto the surface of a carbon filament. The carbon wasthen removed by heating the filament in moist hydrogengas. Unfortunately, the resulting tungsten filamentproved to be very fragile. The company wishedto rectify this problem by employing special-purposesupport wires. (92)In March, 1906 the succes of the experiments alreadysuggested that the mass-production of tungstenlamps could soon commence. To be able to do that,however, the company would have had to investsubstantial sums which it did not have. On short notice<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> could have sold its power plants inLosonc and Budafok or its factory in the Huszar Streetonly at a great loss. The only course of action seemedto be the raising of the company's equity, to which thegeneral meeting eventually gave its consent on 23March, 1906. The shares issued in the nominal value of1 million Koronas were bought up by the CommercialBank and Niederosterreichische Escompte Gesellschaftat a rate of 115 percent. (93)The hopes of an early start in the mass-production oftungsten lamps, however, proved a little too optimistic.Steady work and perseverance was needed toovercome the difficulties. Nevertheless, the companyswiftly made the necessary preparations for production:in September, 1906 it put its new (second)power plant into operation and by then it has alsocompleted the work sites. (94)By late September the difficulties of mass-productionhad been largely overcome and hence the preparationsfor a trial run producing 600 lamps a day couldcommence. The company made the start of massproductionpending on the results of this test. (95)Since at the beginning of the trial run certain disagreementsemerged between the inventors and the managerof the Lamp Manufacturing Department, theexecutive committee decided that:- the trial run currently being performed as well asthe mass-production under preparation must, withoutfail, involve the participation of Dr. Sandor Just andFerenc Hanaman;- as soon as mass-production replaces the trial run,the inventors must be given laboratory where they cancontinue with their research aimed at further developingthe tungsten lamp;-the executive committee must invest the necessaryamount for mass-production as soon as possible;-V-^>

<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>•>-^:.V22-the production of tungsten lamps must beevaluated every fortnight. (96)In late November, 1906 the trial run started on fourproduction lines, producing 700 light bulbs a day.Initially there were many faulty bulbs due to the highbreakage by the inexperienced female work-force whohad been recruited from the vicinity of Ojpest. Moreworrying than was the fact that the filament of thelamps did not stand up very well to transportation.While the cargo to St. Petersburg, Madrid and Milanarrived relatively safety, the tungsten lamps exported^ to Vienna and Prague, despite the careful packaging,often ended up broken.The tungsten lamps generated such a great interestthat in 1907, after seeing the promising results of thetrial runs, the start of mass-production could no longerbe delayed. The company management invested986,000 Koronas in this project. (98) Since the managerof the Lamp Manufacturing Department was entirelyengrossed in the problems of tungsten lamp production,Simon Just, who had earlier been working forFluorescent Light Company of Berlin and Bergmann' • Electrical Company, was called in to act as deputy., manager. That was also the time when the chemist Dr.Ferenc Salzer signed his contract. Later he became themanager of the Lamp Manufacturing Department. (99)By early 1908 the production volume reached 2,500pieces a day, while the capacity approached 3.500pieces a day. In order to strengthen the technical staffof the Tungsten Lamp Unit, in April 1908 the managementsigned another two-year contract with FerencHanaman. In this contract Hanaman committed himselfto participating in the work of the Tungsten LampUnit as technical expert and staff member until 31December, 1909. To secure his cooperation, TUNGSRAM doubled the salary which had been determined inhis first contract signed in 1906. On top of that, hewould have been given the annual sum of 1,200Koronas to cover his accommodation expenses, hadhe been willing to move to Ujpest. (100) In spite of allthis, Hanaman did not take part in the work of theTungsten Lamp Unit for long. Without seeking themanagement's approval, he left for the United Statesin January 1909.As Hanaman had failed to return by 1910, the<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> terminated his contract as of 1 September,1910. In any case, he had not received hissalary for the previous two years. The managementnotified Hanaman that his cooperation would only berequired in the future, if he submitted himself to thecompany's disciplinary procedures. Simultaneously,Dr. Just's contract of employment was also terminated,as he-allegedly-had spent all his time lately onthe legal aspects of patents (101), instead of leaving itto the official in charge of the matter. Dr. Just'sdismissal, however, could be traced back to his insistenceon certain licence fees. The departure of twosuch eminent scientists meant serious losses to thetungsten lamp manufacturing of <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>.The mass-production of tungsten lamps required furtherand further investments. As the factory's GasSupply Unit could not meet the ever-increasing demandsof the Tungsten Lamp Unit, and since theproblem of storage could not be resolved, either, in1908 the Gas Supply Unit was expanded. (102) In thefollowing year the work area and the storage space ofthe Tungsten Lamp Unit was enlarged and a newbuilding was added. The Gas Supply Unit, where thenecessary hydrogen was produced, also received furtherinstallations. (103)Beside the latest investments and the developing ofnew support wires for the tungsten filament, themanaging directors were concerned with other problemsof light bulb manufacturing. In this respectseveral of their projects were crowned with success.For example, from AEG of Berlin they bought thelicence for producing vitrit glass and from 1907 onwardsvitrit glass replaced the porcelain insert of thelamp base. (104) In 1908 the company produced ametal lead-in wire which was a great deal less expensivethan the platinum wire used earlier in incandescentlamps. (105) At the same time, the companybought the license for producing a kind of chromiumplatedmetal wire suitable for supporting the tungstenfilament. (106)After overcoming the numerous obstacles, the daily

23 <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>output of the Tungsten Lamp Unit grew to 5,000 piecesin 1909. On the initiative of the technical manager,Jozsef Pinter, the company introduced the productionof paste in the manufacturing of tungsten filamentsstill in the same year. For this purpose Pinter alsoasked permission to enlarge the building; however,the executive committee did not agree to any additionalconstruction work, as the investment intungsten lamp production had already totalled over1.4 million Koronas. As a temporary solution, theexecutive committee suggested the introduction ofnight shift. (107)The company, the inventors and two Viennese investorsfounded the International Tungsten Co. Ltd. formarketing the patent of Dr. Just and Hanaman on 19November, 1906. (108) The company, which hencebecame the sole proprietor of the patent, licensed it inthirteen different countries. Gyula Egger was namedas the chairman of the public company, Ferenc Hanamanwas his deputy and Dr. Sandor Just became thechief executive. The board of directors of the InternationalTungsten Co. Ltd. unanimously endorsed thecontracts which <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> had signed with Dr.Sandor Just and Ferenc Hanaman in Ujpest on 15February, 1905 in the matter of the two inventors'employment. (109) <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> had sold the licenceto produce tungsten lamps in Germany for 800,000German Marks even before International Tungsten Co.Ltd. was formed; in England the license was marketedin 1907. The deal concluded with General Electric Co.was worth $75,000. (110)The intense competition in the export market and therecurring drops in the price of tungsten lamps urgedthe company to further investments and greater production.In order to remain competitive, the executivecommittee issued the directive to make arrangementsfor the production of 10,000 lamps a day. Immediatelyafter the resolution preparationswere made to enlargethe factory. Three wings were given second floors andthe construction and fitting of the new work hallsbegan. In the spring of 1910 further two wings receivedsecond floors. The useful area of the Tungsten LampUnit grew to 8,250 m' from 4,100 m' within one year.The cost of investment totalled 1,845,000 Koronas.(Ill)In spite of all this, the company was only able to meet60 percent of the existing demands in the countrieswhere it held the license, which amounted to 5 milliontungsten lamps. There was a real danger of newcompetitors' emergering. The continuing reduction inthe price of the light bulbs further pressed the companyin the direction of greater production. In 1910AEG of Berlin reduced the price of tungsten lamps by33 percent and, of course, <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> had to followsuit. The forecast further fall in the prices could onlypartially be balanced by the reduction of productioncosts, hence leaving no alternative for the companybut to increase the volume of production intensely inorder to eliminate the competition and prevent thefurther shrinking of its profit margin. (112)Bythe end of 1910 the technical manager, Jozsef Pinteralready recommended to make preparations for theproduction of 22,000 lamps a day.Without the slightest hesitation, the executive committeeauthorized the managing directors to expand theTungsten Lamp Unit, investing further 1.5 millionKoronas. The construction work and establishing wascompleted by the end of 1911. The work halls of theLamp Manufacturing Department were not yet availablefor the Tungsten Lamp Unit, as the former department,with its business waning, could still bring in anannual profit of over 200,000 Koronas. (113)With the expansion of the Tungsten Lamp Unit anincrease could be anticipated in the factory's hydrogenconsumption. This caused serious problems, since theGas Supply Unit was, in many respects, objectionable:first of all, it was not safe from explosion and, secondly,the customers buying the oxygen (the by-productsold to reduce production costs) often complainedabout the purity of the gas. For this reason, in thespring of 1911, Linde Company founded a factoryproducing hydrogen on the premises in accordancewith an agreement drawn up between the parties. TheMunich company paid 8 Koronas for every squarefathomof the land its business took up. The hydrogenproduced here was led into the main container of

<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>.^.•:-i-'24<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> through a pipe system. <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong>even handed its own Gas Supply Unit over to LindeCompany. The transaction did not require any investmentand guaranteed the factory's hydrogen demandat a fabourable price. (114)While the management of <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> was constantlyoccupied with the upgrading of its Tungsten LampUnit, a revolutionary invention was developed in theresearch laboratories of General Electric Co. in theUnited States. In 1908 William D. Coolidge discoveredthat tungsten powder sintered and pressed into rods ata temperature of 1,500 C became so ductile that therods were suitable for wire-drawing. The Coolidgeprocedure became the basis of economical tungstenlamp production very soon and, after Siemens andHalske of Berlin had bought the patent in 1911, theprocedure also became widely used in Europe.In the autumn of 1911 <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> suffered a setbackin the competition against the German tungsten lampmanufacturers. In six months it was only able to sellone and a quarter million tungsten lamps on theforeign market, because the Coolidge technology enabledits competitors to flood the market with cheaperand better-quality tungsten lamps. For this reason, theboard of directors of <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> ordered the managementto employ experts for developing the wiredrawingprocedure immediately. (116) Beside thetechnical problems, however, difficulties concerningthe patent rights also emerged. Hence, in May, 1912,<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> decided to contact Auer Company, theGerman licence holder of the American patent, andproposed to set up a body representing joint interests.The Berlin company wanted the Lamp ManufacturingDepartment of <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> to from a separate publiccompany and hand the majority of the shares over toAuer Company. Although this was thecompany whichmanufactured and distributed the Osram lamp, thebest coil lamp at the time, the transaction did not takeplace, because handing overthe majority of the shareswould have meant the foregoing of the company'sindependence. (117)After this unsuccessful attempt the management renewedits efforts to lay hands on the productionlicense. In autumn, 1912 it began negotiations with theGerman license holders of General Electric Co.'s patent,Siemens und Halske and Auer A.G. Initially theBerlin manufacturers asked for 8 percent of the sellingprice of the lamps as the license fee. Basing thecalculations on the marketing of 5 million lamps in oneyear, this would have meant for <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> anexpenditure of 400,000 Koronas. (118) After prolongednegotiations the licence agreement was finally concludedon 1 December, 1912. According to this<strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> had the right to manufacture tungstenlamps with the Coolidge technology; in return it was topay 3 percent license fee after the first 6 million lamps,and 15 percent afterthe lamps produced on top of this.In addition, <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> undertook not to sell lampsproduced with the Coolidge procedure in England andFrance. The agreement prohibited the Austrian licenseholders of the Coolidge technology from setting uptungsten lamp factories in Hungary. This, however, didnot stop the Viennese lamp manufacturer Janos Kremenetzkyfrom founding a factory producing tungstenlamps in Budapest in 1913, even though the Hungarianmarket was inundated with tungsten lamps. Thisaction prompted the management of <strong>TUNGSRAM</strong> tocall upon the Berlin lamp manufacturers and ask themto start patent law proceedings against Janos Kremenetzkyfor breaching the agreement. (119)By 1913 the Tungsten Lamp Unit was entirely convertedto the application of the modern Coolidgetechnology in its production of tungsten lamps. Thesewere already marketed with the Tungsram trade-markmentioned before registered in 1909. (120) In the LampManufacturing Department, the company continuouslyinvested in the up-to-date technology after 1908,this way securing the profitability of production on thelong run. The machine lines would have allowed themanufacturing of 22,000 lamps a day, even thoughproduction was increased only by 45 percent, as all theefforts to boost the production volume were frustratedby the extremely large fluctuations in the labourforce.Every spring and autunm twenty-five percent of theworkers left the company and undertook agriculturalwork. At the same time, the training of new workers• * .