Home Affairs Committee - Parliament

Home Affairs Committee - Parliament

Home Affairs Committee - Parliament

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

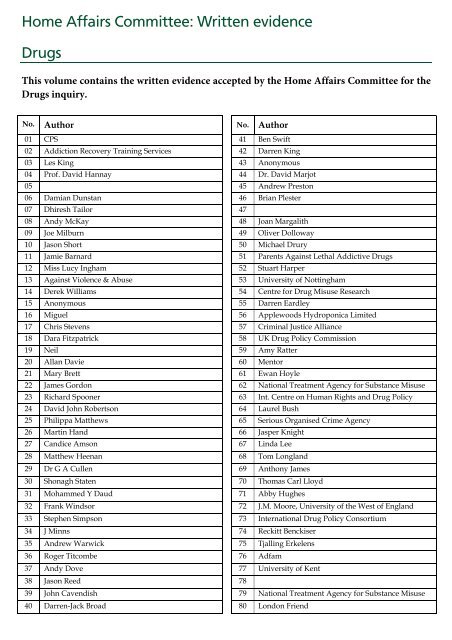

<strong>Home</strong> <strong>Affairs</strong> <strong>Committee</strong>: Written evidenceDrugsThis volume contains the written evidence accepted by the <strong>Home</strong> <strong>Affairs</strong> <strong>Committee</strong> for theDrugs inquiry.No. Author No. Author01 CPS 41 Ben Swift02 Addiction Recovery Training Services 42 Darren King03 Les King 43 Anonymous04 Prof. David Hannay 44 Dr. David Marjot05 45 Andrew Preston06 Damian Dunstan 46 Brian Plester07 Dhiresh Tailor 4708 Andy McKay 48 Joan Margalith09 Joe Milburn 49 Oliver Dolloway10 Jason Short 50 Michael Drury11 Jamie Barnard 51 Parents Against Lethal Addictive Drugs12 Miss Lucy Ingham 52 Stuart Harper13 Against Violence & Abuse 53 University of Nottingham14 Derek Williams 54 Centre for Drug Misuse Research15 Anonymous 55 Darren Eardley16 Miguel 56 Applewoods Hydroponica Limited17 Chris Stevens 57 Criminal Justice Alliance18 Dara Fitzpatrick 58 UK Drug Policy Commission19 Neil 59 Amy Ratter20 Allan Davie 60 Mentor21 Mary Brett 61 Ewan Hoyle22 James Gordon 62 National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse23 Richard Spooner 63 Int. Centre on Human Rights and Drug Policy24 David John Robertson 64 Laurel Bush25 Philippa Matthews 65 Serious Organised Crime Agency26 Martin Hand 66 Jasper Knight27 Candice Amson 67 Linda Lee28 Matthew Heenan 68 Tom Longland29 Dr G A Cullen 69 Anthony James30 Shonagh Staten 70 Thomas Carl Lloyd31 Mohammed Y Daud 71 Abby Hughes32 Frank Windsor 72 J.M. Moore, University of the West of England33 Stephen Simpson 73 International Drug Policy Consortium34 J Minns 74 Reckitt Benckiser35 Andrew Warwick 75 Tjalling Erkelens36 Roger Titcombe 76 Adfam37 Andy Dove 77 University of Kent38 Jason Reed 7839 John Cavendish 79 National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse40 Darren-Jack Broad 80 London Friend

81 National Users’ Network 129 Anonymous82 Release 130 Drug Equality Alliance83 Robert Young 131 All-Party Parlmnt Group for Drug Policy Reform84 Independent Scientific <strong>Committee</strong> on Drugs 132 National Drug Prevention Alliance85 The Alliance 133 Law Enforcement Against Prohibition86 Adam Corlett 134 Adam Langer87 Alastair Crawford 135 London Drug and Alcohol Policy Forum88 Angelus Foundation 136 Jake Chapman89 Grant Finlay 137 Addiction Recovery Foundation90 Anonymous 138 Anonymous91 Indigo Hawk 139 Sheila M. Bird92 Duncan Reid 140 Health Poverty Action93 Carl Nolan 141 RehabGrads94 Pheon Management Services UK 142 The Beckley Foundation95 Fraser Ross 14396 The Royal College of Psychiatrists 144 John Blackburn97 P.R.Sax 145 Richard98 Harm Reduction International 14699 Liam Barden 147 Keith Scott100 Crime Reduction Initiatives 148 Kevin Sabet101 Christopher Bovey 149 Joel Dalais102 University of Leeds 150 Medical Research Council103 Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons 151 Malcolm Kyle104 British Veterinary Association 152 Jack Brown105 Association of Directors of Public Health 153 Andy Lynette106 Students for Sensible Drug Policy UK 154 Jeffrey Ditchfield107 DrugScope 155 Peter Hitchens108 Dave Harris 156 Charlie Lloyd and Neil Hunt109 Kate Francis 157 <strong>Home</strong> Office110 Cannabis Law Reform (CLEAR) 158 World Federation Against Drugs111 Colin Fisher 159112 Joseph Burnham 160 Anonymous113 Sir Keith Morris 161 Mick Humphreys114 Chris W. Hurd 162 Association of Chief Police Officers115 Elizabeth Wallace 163 Simon Lent116 Centre for Policy Studies 164 Jeremy Collingwood117 Daniel Stamp 165 James Taylor118 Gavin Ferguson 166 Maranatha Community119 Jonathan Ford 167 Sarah Graham Solutions120 Constantine Geroulakos 168 Deborah Judge121 Europe Against Drugs 169 Hope Humphreys122 Berkshire Cannabis Community 170 Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs123 Mike Williams 171 User Voice124 Re:Vision Drug Policy Network 172125 James McGuigan 173 Caroline Lucas126 Substance Misuse Management in General Practice 174 Mat Southwell127 Transform Drug Policy Foundation 175 Julian Pursell128 Dan O'Donnell 176 Cam Lawson

177 UK Cannabis Social Club178 Stuart Warwick179 Fade Vilkos180 R P Jones181 Russell Brand182 Nik Morris183 Alliance Boots184 Michael Mac185 Ministry of Justice186 Anonymous187 Anonymous188 Eric Mann189 Mark Cruickshank190191192193194195196As at 13 March 2012

Written evidence submitted by the Centre for Policy Studies [DP001]I am writing to you about your prospective <strong>Home</strong> <strong>Affairs</strong> Select <strong>Committee</strong> enquiry into drugs policy.I am concerned that the <strong>Committee</strong>'s line of enquiry is being predetermined by the GlobalCommission on Drug Policy's recommendations and that its independence has been compromised. Ienclose a copy of the blog I posted on the Centre for Policy Studies website yesterday in response to<strong>Home</strong> <strong>Affairs</strong> Select <strong>Committee</strong>'s published call for evidence 'in line with the recent recommendationof the Global Commission on Drug Policy'.What you may not be aware of is that the Global Commission is not a neutral body or an independentthink tank. It is financed amongst others by Richard Branson and the billionaire George Soros. It isclear from its website that is has a professionally coordinated public relations strategy, the goal ofwhich is the legalisation and decriminalisation of drugs.I enclose a Fact Sheet published by the CPS recently on the Global Commission's Misleading andIrresponsible Drug Prevalence Statistics.I would be happy to explain these and other frequently misrepresented statistics to you in person.September 2011The <strong>Home</strong> <strong>Affairs</strong> Select <strong>Committee</strong> risks undermining democracy by Kathy GyngellThe <strong>Home</strong> <strong>Affairs</strong> Select <strong>Committee</strong> (HASC) is fast becoming our new public moral arbiter. With itsurbane and intelligent chair, Keith Vaz MP, it has increasingly taken centre stage, dissecting in turn,responsibility for the riots, phone hacking and border control.Their launch this morning, of a comprehensive review into drug policy is though, worrying. It is notthat it is unreasonable to re examine drug policy, one of the big social issues of our time; it is, afterall, eight or nine years since they last did so. Last time, I note the <strong>Committee</strong> incorporated a youngDavid Cameron, who has since recanted some of the 2002 <strong>Committee</strong>'s wilder conclusions (TheGovernment's Drugs Policy: Is It Working?, HC 318, 2001-02) and specifically those on the harms ofcannabis.My concern this time, is their apparent uncritical adoption, lock stock and barrel, of the self-styled"Global Commission on Drug Policy" agenda, as set out in the call for evidence yesterday.It is surely reasonable to expect all such select committee enquiries to start with a blank sheet ofpaper, without any pre-conceptions or prejudice within their terms of reference, least of all, for such a<strong>Committee</strong> of the House of Commons, to be a tool for a lobby group. If they do not do this, what,frankly, is the point? But it is striking, in the case of this new HASC enquiry, the extent to which thisis not the case.By marked contrast with the specific factual questions of previous enquiries HASC's call for writtenevidence on drugs policy avoids requests for factual information. Instead it frames its enquiry in thecurious terms of: "The extent to which the Government's 2010 drug strategy is a 'fiscally responsiblepolicy with strategies grounded in science, health, security and human rights' in line with the recentrecommendation by the Global Commission on Drug Policy."A list of fudged 'areas' for investigation follows—for example, "Whether the UK is supporting itsglobal partners effectively" and "The extent to which public health considerations should play aleading role in developing drugs policy". Why HASC has not posed these as straightforward questionsis not clear. For surely one of the questions we need the answer to is: to what extent have publichealth considerations played in the development of drugs policy (particularly in view of that seminal1

advice from the ACMD in 1988 that Aids was a bigger threat to the public than drug misuse) andwhat impact have the subsequent mass 'public health' interventions of needle exchange and opiatesubstitution had on the drug problem? Not a question perhaps that the Global Commission wants tohear the answer to.To use the Global Drug Policy Commission's recommendations as their starting point makes it almostinevitable that a 'skewed' report will result. But worse, HASC's stated 'alliance' with this group begsthe question of whether their terms of reference have been 'planted' on them (and manipulated) toconfer authority on what is a well financed, self appointed pro-legalisation lobby group? It also begsthe question of whether indeed, behind the scenes, this body is already providing the committee withtheir research 'expertise', either directly or covertly?Putting aside for one moment consideration of HASC's new 'fiscal responsibility policy test'—not oneI believe applied previously to their recent inquiries into the riots, border control or policing—it lookssuspiciously like the <strong>Home</strong> <strong>Affairs</strong> Select <strong>Committee</strong> Administration has indeed been handed thisagenda (possibly by inhabitants of "the other place") and has uncritically and unquestioningly,regurgitated it.It is understandable how and why this could have happened. In recent months the <strong>Committee</strong>'s remithas been huge and inevitably beyond the capacity of the staff and the research it has at hand. Staff too,may be naive about the subtleties of high level lobbying and perhaps in some awe of those providingthem with this unsolicited but apparently helpful advice, no doubt dressed up as dispassionate.So I would ask the <strong>Committee</strong>'s Chair, Keith Vaz, to review the terms of reference urgently. Thediscrimination he needs to make between preferential 'advice' and evidence submission should beclear to him.• Yes, it is reasonable to expect his committee to recognise and hear from legalisation or anyother lobby groups, powerfully funded or otherwise.• Certainly they should be taking evidence from such groups.• But when they do so, their concern should also be with asking them searching and probingquestions about what lies behind their advice—their funding, their support and their possiblefuture commercial interest—and the philosophy of drug use within those groups.• But NO, it is not reasonable for HASC to align itself with one participant in the field whethercovertly or manifestly.For the Global Commission's media and public relations strategists must be congratulating themselveson this 'coup'—a priceless one in financial, media and most of all, in political terms. It is one that willreverberate around the world and, uncorrected, it will do just this before the review has even got outof the starting blocks.So if the committee is not to become a lap-dog and if this inquiry is to be treated with the respect itdeserves, the terms of reference cannot be framed exclusively by the agenda of any lobby, whateverthe profile of the 'names' attached to that lobby or the massive finance behind it. Nor should it, bynaming that lobby, be giving it prior authority over the terms of the debate—not least when its dearthof objectivity, in the misleading and irresponsible statistics it contrived to make its case, has alreadybeen exposed.The call for evidence must be framed as questions. The date for written submissions must be extendedfrom the ridiculously short notice of 10 January 2012.If HASC goes ahead without rectifying this, then the (ab?)use of a Select <strong>Committee</strong> by such a lobbygroup must be a case for referral to the House of Commons Standards and Privileges <strong>Committee</strong>.2

Misleading and irresponsible drug prevalence statisticsThe Global Commission on Drug Policy's provocative claims of non-existent rises do not furtherrational drug policy debate.The Liberal Party Conference (2011) policy motion 24, Protecting Individuals and Communities fromDrug Harms, emphasised the need for evidence-based policy making on drugs in support of their callsto liberalise drug use through a variety of legalising and decriminalising proposals.It cited the recent Report of the Global Commission on Drug Policy—a newly emerged body whosemembers include former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, former heads of state of Colombia,Mexico, Brazil and Switzerland, the current Prime Minister of Greece and a former US Secretary ofState—as a source of such evidence.The central assertion of this report is that international drugs control policy has failed to curtailconsumption. The key 'evidence' to back this claim is set out in a table at the start of the report (page 4of the 24 pages) titled "United Nations Estimates of Annual Drug Consumption, 1998-2008." It showsdramatically rising global drug consumption (opiates, cocaine and cannabis), specifically in thedecade 1998-2008. The inference from the title is that these are 'official' figures. However, no specificsource is given. Nor is the basis on how they were arrived at, or calculated, provided anywhere in thesubsequent text. A subsequent textual reference could lead the informed reader to suppose their sourceto be the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) (2008) 2008 World Drug Report:Vienna, United Nations.The Global Commission's argument supported by it dramatic figures and its influential backers hasbeen widely reported in the media, The United Nations source of this evidence has been accepted asreliable and, indeed given prominence, adding to their apparent authority. Indeed they continue to bewidely quoted even following complaints to the Press Complaints Commission.But searches back through UNODC World Drug Report statistical tables for 2008—and all otheryears—singularly fail to elicit the evidence for the Global Commission's claimed rises of 34.5% foropiates, 27% for cocaine and 8.5% for cannabis.Data defined by reference to other documents and sources, that the majority of the reading andlistening audience, including the media, are not expected to have read, can be data to be beware of.This is a case in point. Following a request for clarification from the UNODC, our worst fears as tothe provenance and reliability of the Global Commission's figures have been confirmed.We now have the UNODC's own detailed analysis of the figures that the Global Commissionmisleadingly attributed to the United Nations. Their investigation into how the Global Commissiongenerated the figures shows that global drug consumption, in terms of drugs consumption prevalence,far from rising between 1998 and 2008, remained stable. Their best estimates of the number ofcocaine and opiate users show prevalence rates for annual opiate use remaining stable at around0.35% and for annual cocaine at 0.36 %, in the population age range 15-64, between 1998 and 2008.The Global Commission's statistics are not just over-blown, they are contrived and misleadinglyattributed.The UNODC's polite explanation for the disparity they found is that the Global Commissioncalculated their figures 'on the basis of a flawed methodology'.The UNODC analysis and explanation is set out verbatim below (their 'bold' has been kept):Clarifications regarding the estimates of drug use presented in the Report of the GlobalCommission on Drug Policy and attributed to UNODC3

The Global Commission's report presented the following numbers on the evolution of drug use tosupport its claim of rising drug use:Opiates Cocaine Cannabis1998 12.9 million 13.4 million 147.4 million2008 17.35 million 17 million 160 million% increase 34.5% 27% 8.5%According to these numbers the increase would have been particularly strong for opiates and cocaine.The paper did not give precise references, but attributed these numbers to UNODG. After someresearch, it appears that the source for the 1998 figures were UNODC 2002 Global Illicit DrugTrends 1 (which gave numbers for the period 1998-2001, rather than for 1998 only, as presented bythe authors of the commission's report).As for the 2008 figures used in the paper, they appear to have been calculated by the authors of thepaper, as mid-point of the statistical ranges presented in UNODC 2010 World Drug Report. It is notcorrect to assume that the mid-point of statistical range necessarily represents the best point estimate.As a matter of fact, in the same issue of the World Drug Report, UNODC did present best estimatesfor cocaine and opiate use, with 15.42 million users for cocaine 2 (as opposed to 17.35 million in thecommission's report), and to 15.9 million for opiate users 3 (as opposed to 17.2 million in thecommission's report).Based on UNODC published best estimates of the number of cocaine and opiate users, the numberof annual users for opiates increased, between 1998 and 2008, by 19.6% (as opposed to 34.5% aspresented in the Global Commission's report) and by 18.7% for cocaine (as opposed to 27% aspresented in the Global Commission's report).UNODC 1998-2001 bestestimate (Global IllicitDrug Trends 2002) inmillions of peopleUNODC range of annualusers in2008 (World Drug Report2010) in millions ofpeopleMid-points calculatedby the GlobalCommission for 2008in millions of peopleIncrease 1998-2008 in %UNODC best estimatefor 2008 (World DrugReport 2010) in millionsof peopleIncrease 1998-2008 in %Increase in worldpopulation age 15-Opiates Cocaine Cannabis12.9 13.4 147.412.84 - 21.88 15.07 - 19.38 128.9 - 190.7517.3534.5%15.4219.6%1727%15.918.7%18.5 %1608.5 %(not calculated)1 UNODC, Global Illicit Drug Trends, 2002, p.2132 UNODC, World Drug Report, 2010, p.713 UNODC, World Drug Report, 2010, p.40 (11,314,000 for heroin users, and 4,119,500 for opium users)4

64 from 1998-2008 in %Moreover, the extent of drug use is not measured and tracked through absolute numbers only. Theprevalence rate expresses drug use as a proportion of the population (the age group 15-64 years oldis normally used). During the period 1998-2008, the world population aged 15-64 grew by 685million people, or + 18.5 %. Even if the prevalence of drug use remains the same, the increase inpopulation would mean that the absolute number of users would increase proportionally. Thisimportant fact was not taken into account by the authors of the Global Commission's paper.Based on UNODC published best estimates of the number of cocaine and opiate users, theprevalence rates for annual use in the population age 15-64 remained stable at around 0.35% foropiates and 0.36 %for cocaine between 1998 and 2008.UNODC did not present a best estimate for the number of cannabis users, but one can note that theincrease calculated in the Global Commission paper (+8.5%) is actually below the 18-64 age grouppopulation increase (+18.5 %) which would translate in a decline of the prevalence rate of use forcannabis.5

Written evidence submitted by the Addiction Recovery Training Services [DP002]Executive SummaryDetailed consideration should be given to alternative ways of tackling drug rehabilitation. The principle“treatment” policies of the last 60 years have failed to halt expanding addiction, but the Coalition’s 2010strategy appears destined to succeed because at its core is demand reduction derived from bringing theexisting addicts who create demand to lasting abstinence.With “training” in 45 year proven self-help recovery techniques, “lasting abstinence/demand reduction”can be achieved at a tiny fraction of the cost to taxpayers of status quo psycho-pharm “treatments”, andcan start to be implemented two years earlier than completion of the ongoing Payment by Results “pilots”.Submitted byThe writer is a retired UK Magistrate, trained in addiction recovery techniques in Sweden, who foundedAddiction Recovery Training Services in 1975 “to inform UK officials & public about those registeredcharities which, by providing training in effective do-it-for-yourself recovery methods, help a majority ofindividual addicts to achieve for themselves a lasting return to the natural non-criminal state of relaxedabstinence into which 99% of the population is born.”it became obvious that the “training” in other countries of alcoholics and drug addicts was not onlyachieving abstinence results far in excess of those attained by “treatment”, but also in the UK such trainingwas being attacked, marginalised, ridiculed, denigrated and systematically blackened by the vested interestproviders of basically ineffective treatments and counselling.It is therefore our mission to inform local community officials and national decision-makers of the vastlysuperior results obtained from training addicts in do-it-for-yourself addiction recovery techniques,especially as, under the Coalition government’s new drugs strategy, such training delivers—better thanany other system—the results the government now requires.SubmissionWhilst the Government’s 2010 Drugs Strategy is a very appropriate subject for the H.A.S.C., attemptswithin the next two years to examine that strategy’s effectiveness will be just about as worthwhile astrying to examine the effectiveness of a new form of flying machine which has yet to be built andoperated.This is because the 2010 drugs strategy will not be fully ready for launching until the start of 2014.Consequently, examinations undertaken prior to that will inevitably be a re-inspection of the still ongoingbut failed strategies of the last 60 years—which the Coalition in its 2010 policy statement announced arenow to be abandoned.Unfortunately, seeking to change a policy originated in the 1950s on psycho-pharmaceutical treatment“advice” (and now entrenched in the society for 60 years) is like trying to stop and change the direction ofa gigantic oil-tanker. Inertia alone renders this a massive time and effort consuming manoeuvre, and,when also covertly resisted by senior members of the tanker’s crew for their own financial reasons,provides a near mutinous situation for the Captain.The four year delay on the full launch of the 2010 drugs strategy has been imposed:a) by the resistance (of the NHS’s so-called “scientific” but nevertheless failed “experts” at theNational Treatment Agency (NTA) to the new government’s plans for the NTA’s totallydeserved closure, and,b) by a concurrent plea from the NTA’s psycho-pharmaceutical supporters for time: “to ‘pilot’the fiscal and operational effects on the solvency of rehabilitation providers of ‘Payment byResults’ (PbR)”.6

All of which is proving to be no more than an excuse for the treatment providers of the last decade to buytime to try and develop a psycho-pharm based addiction recovery system which can actually deliver the2010 strategy goal of lasting abstinence.If they do find a way, the question must be asked as to why they never earlier even attempted to seek acure for addiction but preferred instead the daily turnover and profit obtained from supplying “treatment”based on methadone and buprenorphine, naloxone and disulfiram, etc., plus regular sessions of psychiatric“counselling”, all supplied by psycho-pharm vested interests.But all this pretended need for “piloting” PbR or any new form of “treatment” is an unnecessary costlydelay, because there is already available in 49 countries an addiction recovery training programme whichfor up to 75% of dependents using most addictive substances delivers the lasting abstinence results thegovernment seeks.But the above mentioned programme, which has been delivered internationally for 45 years is notacceptable to psycho-medico-pharmaceutical interests because it is not “treatment” and so does not requirethe services of psychiatrists or daily supplies of pharmaceutical drugs paid for by the taxpayer.The reason for the failure of the “treatments” of the last 6 decades (“treatments” which will be with usuntil at least 2014) is because substance addiction is provenly not a treatable condition.Addiction is not a disease or something you catch by infection or from contagious contact. Addictionarises from a decision or agreement made by an individual to ingest a substance in the belief that thatsubstance will help him to solve what he considers a problem in his life.This is the same reason individuals have for taking any drug.Aspirin for headaches, a sleeping pill for insomnia, another pill for sea-sickness, a glass of spirits toreduce tension, or a dose of Valium to handle a worrying loss, etc.Addictive substances are used as “solutions” to situations perceived by the individual to be a problem, andbecause they are each individual’s own solution he will resist removal of “his solution” by any treatment,however well meant, which attempts to “do” things “to” or “for” him.This is because, although the drug initially appears to help his problem solving, he soon learns thatquitting is not easy, and begins to find his life controlled, not by his own decisions, but by theunconfrontable effects of cold-turkey withdrawal, by the increasing desire for the drug itself, and by thosewho supply it.“Treatment” involves more control by others, who are trying to take away from the addict what heconsidered a valuable solution. So which side of the fence is he subconsciously on in any “treatment”scenario which is imposing more control on his actions and decisions? The evidence of the last 60 yearsshows that attacking an addict’s solutions does not cure him, and can build resistance to treatment.The recommendations of the manipulated and biased Global Commission on Drug Policy, which appear tohave prompted this select committee inquiry, are manifestly based on the same failures of national policiesexperienced by practically all countries during the last 6 decades.Because “treatments” cannot cure addiction, nearly all national policies derived from “advice” given bycommercially orientated psychiatric and pharmaceutical “experts” are based on their false claim thatsubstance addiction is “incurable”. This is because for the psycho-pharms an addicted client is a goosewhich daily lays golden eggs in profit terms, and so they want addicts regarded as a species to be protectedfrom being cured by anyone.Under the 2010 government drug policies the efficacy of those polices is measured by the number ofaddicts which recover to lasting abstinence, and consequently improve their health and wellbeing,abandon usage of supporting acquisitive crime, take up employment and increase concern for theirfamilies.7

Unlike earlier successive UK governments, which have taken dubious so-called “expert advice”exclusively from the psycho-pharmaceutical sector, it is clear from the 2010 drugs strategy that theCoalition have been prepared to seek and examine recovery results achieved abroad for many decades, andso one expects they will be helping to expand and promote the Anonymous 12 Steps system, which for 75years has been providing lasting abstinence results ten times more often than methadone prescription“treatment”.The quality and sort of advice given by any drug producer is never independent, and often 180 degreesopposite to that from providers with a long record of successfully bringing addicts to lasting abstinence,and in fact training addicts in do-it-for-yourself recovery techniques has for 45 years proved by far themost consistent addiction cure system.When recovered, an addict is self-sufficient. He is not cured if he needs a doctor or policeman to watchhim for the rest of his life—a continuing burden on other taxpayers. So training in self-help addictionrecovery techniques provides tools which the former addict can continue to apply to himself—for life.Psycho-pharm “in-treatment service users” inevitably burden the government and other electors withmassive costs. The government’s National Audit Office reported that the costs of keeping an addict onmethadone “habit management treatment” did not just involve the costs of the methadone doses, butincluded some 30 other continuing expenditures inflicted on the exchequer and the public alike by thelifestyles of service users.In addition to the psycho-pharmaceutical and other medical costs involved in provision of the dailyprescription doses, one has to consider such users’ claiming of a full range of benefits, their continuingcriminality and imposition on the police, the courts, the probation system, the costs of various insurances,their higher than normal health costs and the costs of their higher accident rates, creating overall a cost tothe community for each average prescription methadone user of £54,000 every year for the life of thatuser—usually some 40 years, so that one addict’s total lifetime cost is some £2,160,000, and governmentreports some 330,000 problematic addicts, most of them “in treatment”.If the government’s demand for addiction recovery procedures which deliver lasting abstinence is not met,this is a potential cost to our economy of nearly £18 billion each year for the next 40 years!On the other hand, addicts can be residentially trained to bring themselves to lasting abstinence for a onceonly cost of £19,500, and will achieve that result in 55 to 70+% of cases.If there is no demand for a product, no one will bother to supply it. By far the greatest demand foraddictive substances comes from existing drug users, but when interviewed one finds that 70 to 75% ofthem:a) have tried to stop on numerous occasions, butb) in spite of their failure to quit, they still want to stop.The other 25 to 30% of “resistive cases” have no desire or intention whatsoever to quit for three mainreasons:i) for some their drug is “their whole life”,ii) others have failed to quit so often that they absolutely“know” they are incurable, and then there areiii) those who are self-medicating for some psychosis orparanoia and refuse to again confront their terrors.But 55 of the 70 to 75 in every 100 existing addicts who have tried, failed but still want to stop, can do sofirst time through a 26 week residential self-help addiction recovery training programme, and another 15or more can also usually achieve lasting abstinence during a shorter second training period.8

So the way to reduce interest in supplying drugs—whether illegal, licensed or prescription—is to slash thedemand, and this is done by reducing the existing number of addicts who generate the demand for bothlegal as well as illegal drugs.This is the way to conduct the so-called war on drugs—which has not been lost—because it has neverbeen properly waged via reduction of demand for drugs of all types. And the reason has been and still is,that there are powerful interests who don’t want their clients/patients taken from them by letting them becured.It will be seen that when it comes to examining the extent to which the Government’s 2010 drug strategyis a “fiscally responsible policy”, one has only to compare the cost to our peoples and our economy ofsupplying and maintaining methadone service users for life at £2,160,000 per addict, with the once onlycost of bringing an addict to lasting abstinence by training him in self-sufficiency for only £19,500.Obviously there can be no greater proof of cost-effectiveness than is portrayed by the very provablefigures quoted in the preceding paragraph.Because by moving addicts into lasting abstinence, reduced demand will reduce attempts to supply, andbecause there will be lower numbers of addicts and pushers to attract police, medical, court, probationattention and prison incarceration, then drug-related expenditure and costs of policing, etc., will clearlydecrease in line with budgets.In fact the very essence of the strategy of insisting on high levels of lasting abstinence is demandreduction, because it is reduced demand which reduces so many other related problems and expenditures.Furthermore lower numbers of addicts help the overall productivity of any country.It is said that one volunteer is worth two pressed men, and that a religious convert is usually more devoutthan someone born into his religion. History also demonstrates that men or women who have rescuedthemselves from addiction, most often make a better life for themselves and their families than those whohave not looked into the jaws of addiction.The Department of Health has little to do with recovery from addiction, as it is that Department (via theNHS and the NTA) which has presided over the last 60 years of failure to reduce demand for drugs. Eachindustry has its own problems and, for the same reasons that one finds that alcohol dispensing publicans,barmaids and cellar-men have the highest levels of alcoholism, we find that physicians, nursing staff andthose employed in pharmaceutical factories and dispensaries have the highest levels of drug addictionwhen compared to other industries. Familiarity breeds contempt!“Physician heal thyself” is an activity seldom attempted by the DoH, which has for decades merelycommissioned others to provide addiction “rehabilitation” and, because training in self-help addictionrecovery techniques is the 45 year proven method of attaining lasting abstinence and demand reduction,the appropriate Ministry is the Department for Education. Transfer of the NTA’s abortive “treatment”functions to Public Health England is totally inappropriate as “treatment” per se is manifestly not theanswer.Several more points which the <strong>Committee</strong> is scheduled to consider are: the supply and demand of illicitdrugs; the availability of “legal highs” and the legal framework for dealing with them; the links betweendrugs, organised crime and terrorism; and the spiralling availability of both generic and brandedpharmaceutical drugs without prescription.However, all of these are far less important than the vital task of reducing the demand which drives alldrug usage problems—the very task which the Coalition’s 2010 strategy can accomplish.This demand reduction has never been directly tackled by the psycho-pharm recommended “treatments”of the last 60 years. Today however, the Coalition is demanding and supporting lasting abstinence, andthe knowledge that it can succeed (on a programme already proven abroad and at a cost which matches theCoalition’s requirements) handles other concerns.December 20119

Written evidence submitted by Dr Leslie King [DP003]Further to the call for written evidence, as set out in the notice of 29 November 2011 on the<strong>Parliament</strong> website, I attach a memorandum addressing the topic "The availability of ‘legalhighs’ and the challenges associated with adapting the legal framework to deal with newsubstances".None of this material is confidential.1. Executive summary• Almost 200 new psychoactive substances (‘legal highs’) have been notified to theEuropean Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) since 1997.Their rate of appearance is increasing; 41 were notified in 2010, and 2011 is expectedto be another record year. The UK has notified more substances than any otherMember State.• New substances are widely available, yet official statistics (e.g. British Crime Survey,law enforcement seizures, number of offenders and mortality data) provide onlylimited information.• The harmful properties of new substances are largely unknown, yet conventional drugcontrol requires that harm to individuals or society should be demonstrated beforescheduling.• In the absence of basic research on the pharmacology and toxicology of newsubstances, ‘Temporary Class Drug Orders’ may only provide a temporary solution.• The impact of import bans is unknown.• Analogue legislation suffers from many weaknesses.• It is unclear what priority law enforcement agencies give to new substances,particularly at a time of decreasing budgets, and with a trade that often relies on retailinternet sites.• Many countries are exploring and enacting distinct legislation to deal with newsubstances. A common theme is to use or modify consumer protection legislation ormedicines legislation such that the focus is on producers and suppliers, but not onindividual users.• A number of recommendations are listed.2. IntroductionI am now retired. My working life was concerned with drugs analysis, pharmacology,toxicology, epidemiology and policy. I spent 8 years in the pharmaceutical industry andalmost 30 years in the Forensic Science Service, the last ten of which were as Head of DrugsIntelligence. I was a co-opted member of the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs(ACMD) from 1994 to 2007. From early 2008 until late 2009, I was the chemist member ofACMD. From 1997 to mid-2011, I was an advisor to the European Monitoring Centre forDrugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) and responsible to the UK Focal Point on Drugs(since 2003 in the Department of Health) for co-ordinating a United Kingdom network that110

collected and analysed information on new substances. I have published over 100 articles asauthor and co-author in the scientific literature, many book chapters and two books. 1Recent publications include:King, L.A. (2012). Legal classification of novel psychoactive substances: an internationalcomparison, In: Novel Psychoactive Substances: Classification, Pharmacology andToxicology, (Eds. Dargan, P. and Wood, D.), Elsevier, in pressKing, L.A., and Kicman, A.T. (2011). A brief history of 'new psychoactive substances', DrugTesting and Analysis, 3(7-8), 401-403Sainsbury, P.D., Kicman, A.T., Archer, R.P., King, L.A., and Braithwaite, R. (2011).Aminoindanes – the next wave of “legal highs”? Drug Testing and Analysis, 3(7-8), 479-482Nutt D.J., King, L.A., and Phillips, L.D. (2010). Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteriadecision analysis, Lancet, 376, 1558-65King, L.A., and Corkery, J.M. (2010). An index of fatal toxicity for drugs of misuse, Hum.Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exptl., 25, 162-166King, L.A. (2009). Forensic Chemistry of Substance Misuse: A Guide to Drug Control, RoyalSociety of Chemistry, LondonKing, L.A., and Elliott, S. (2009). Review of the pharmacotoxicological data on 1-benzylpiperazine (BZP), In: Report on the risk assessment of BZP in the framework of theCouncil Decision on new psychoactive substances, EMCDDA 2King, L.A., McDermott, S.D., Jickells, S., and Negrusz, A. (2008). Drugs of Abuse, In:Clarke's Analytical Toxicology, First Edition, (Eds. S. Jickells and A. Negrusz),Pharmaceutical Press, LondonKing, L.A., and Sedefov, R. (2007). Early-Warning System on New Psychoactive Substances:Operating Guidelines, EMCDDA, Lisbon 33. ‘Legal highs’3.1 European Union (EU)—Early Warning SystemAn Early Warning System on new psychoactive substances (‘legal highs’) has operated in theEU since 1997 (1, 2). New substances are appearing at an increasing rate; almost 200 havebeen reported to the EMCDDA since 1997. In 2010, there were 41 substances (3), a figurewhich is likely to be exceeded in 2011. The UK has notified more substances than any otherMember State.3.2 Availability in the UKMost new substances can be purchased from retail internet sites. However, apart fromoccasional ad hoc surveys, there is only limited official data on prevalence. The most recentissue of the British Crime Survey: Drug Misuse Declared (4) did include usage of a few of thebetter-known substances (e.g. mephedrone, BZP), but law enforcement seizures of newsubstances were not itemised in the most recent <strong>Home</strong> Office bulletin (5). Mortality datapublished by the Office for National Statistics (6) included data on mephedrone, GBL and1 A full list of published work is at: www.zen140250.zen.co.uk/2 www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/risk-assessments/bzp3 www.emcdda.europa.eu/html.cfm/index52448EN.html211

BZP/TFMPP, but no other new substances. I am unaware of any recent publications detailingthe number of persons prosecuted for offences involving ‘legal highs’.3.3 Unknown harmsMany ‘legal highs’ were originally investigated as potential therapeutic agents by academiclaboratories and the pharmaceutical industry, but never succeeded to market authorisation.Alongside these ‘failed pharmaceuticals’ are true designer drugs, namely the products ofclandestine laboratories (7). Whatever their origin, it is a common feature of new substancesthat almost nothing has been published on their pharmacology; and their harmful propertiesand potential for abuse are unknown.3.4 Scheduling of substancesIt is a general principle of drugs legislation, be that the United Nations (UN) DrugConventions or national laws, that substances should only be scheduled when their harmfulproperties can be demonstrated. In the UK, the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 provides someflexibility in that it is sufficient to demonstrate potential if not actual harm. But in the absenceof published scientific information, risk-assessments can have only limited value. Recourse tothe precautionary principle in drug control is not an ideal solution (8, 9).3.5 Temporary Class Drug OrdersThe recently-introduced Temporary Class Drug Orders (TCDOs) (10) are welcomed as ameans of avoiding a repeat of the unfortunate circumstances that occurred in early 2010 whenthe hasty decision to control mephedrone and related compounds was widely criticised (e.g.11). However, TCDOs will only achieve their full potential provided that, during the period oftemporary control, information is collected on the harmful properties of the substance inquestion. It is likely that such information could only be obtained by conducting originalresearch, at an uncertain cost, on the pharmacology and toxicology of that substance.3.6 Importation controlIn 2010, the substance desoxypipradrol was subject to an importation ban (12) by variation ofthe ‘Open General Import License’. In 2011, the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs(ACMD) recommended that there should be a similar ban for phenazepam (13),diphenylprolinol and diphenylmethylpyrrolidine (14). While this may provide a means ofrestricting the supply of new substances, many of which are manufactured in the Far East, noevidence has been published to show the effectiveness of such bans.3.7 Analogue controlAnalogue legislation was introduced into the United States (US) by the Controlled SubstancesAnalogue Enforcement Act 1986. A recent report from the ACMD (15) recommended thatthis approach should be considered as a means of controlling new substances. The ACMDsuggested that a statutory agency could decide which new substances were “substantiallysimilar” to existing controlled drugs as a means of avoiding some of the recognised problemswith this legislation. However, experience in the US shows that the concept of “substantiallysimilar” relies essentially on individual opinions and is not strictly amenable to scientificevaluation. If the decisions of such an agency were to be challenged in a criminal trial thennothing would be gained, and the defendant could face the prospect of being convicted onwhat might be seen as law that is either retrospective or uncertain.3.8 UK law enforcementIt is not clear what priority is given by Police and the UK Border Agency to seizing newsubstances, particularly at a time of reduced budgets (16). Nor is it obvious that thoseagencies could disrupt a trade that is largely conducted via retail internet sites, some of whichare based beyond the jurisdiction.3.9 International initiatives312

Despite the early lead taken in drug control by the World Health Organisation (WHO) andUN agencies, the current world-wide concern with new substances has not been reflected bythese international bodies. The last, and thirty-forth, meeting of the WHO Expert <strong>Committee</strong>on Drug Dependence took place in 2006. Meanwhile, a number of countries have takenunilateral action to review their arrangements for restricting the availability of newsubstances, and some have enacted specific legislation for this purpose. Some examples areset out below:3.9.1 IrelandThe Criminal Justice (Psychoactive Substances) Act 2010 was designed specifically todeal with the problem caused by novel substances (17), and stands as a piece of legislationquite separate from the existing Misuse of Drugs Act 1977. It makes it a criminal offence,to advertise, sell or supply, for human consumption, psychoactive substances notspecifically controlled under existing legislation. The Act excludes medicinal and foodproducts, animal remedies, alcohol and tobacco. There is no personal possession offence.3.9.2 New Zealand—currentUntil 2008, BZP was listed as a ‘Restricted Substance’ within the Misuse of Drugs Act1975. Substances in this category, informally known as Class D (18), attracted no penaltyfor possession, but were regulated through control of manufacture, advertising and sale,rather than prohibition.3.9.3 New Zealand—proposedIn 2011, the New Zealand Law Commission (19) concluded that a new way was requiredfor regulating new drugs. It proposed a form of consumer protection with elements of the“Restricted Substances” regime. There should be restrictions on the sale of novelsubstances to persons under the age of 18, restrictions on advertising and where they couldbe sold. An independent regulator would determine applications from suppliers.3.9.4 PolandIn 2010, the Polish Government adapted the Act on Counteracting Drug Addiction toeliminate the open sale of psychoactive substances not controlled under existing drug laws(20). The new law prohibits the manufacture, advertising and introduction of ‘substitutedrugs’ into circulation, but does not penalise users.3.9.5 JapanJapan has also experienced a wide availability of new substances. Because of theirunknown harms, it has likewise been unable to incorporate them into the Narcotics andPsychotropics Control Law. These novelties are referred to as ‘non-authorisedpharmaceuticals’ (21). In June 2006, the Pharmaceuticals <strong>Affairs</strong> Law was modified tointroduce the category of ‘designated substances’, where there is a general prohibition onimportation, manufacture and distribution.3.9.6 SwedenIn Sweden, the Ordinance on Prohibition of Certain Goods Dangerous to Health (22) listsdrugs that are not otherwise classified as narcotics. As part of general health and safetylegislation, it includes a number of new substances.3.9.7 AustriaIn January 2009, the Austrian Government used a decree under the Pharmaceutical Law todeclare that “smoking mixes” containing synthetic cannabinoid agonists are prohibitedfrom being manufactured or imported (23).3.9.8 European Union413

The European Commission has begun a process to deal with the deficiencies of theexisting Council Decision (2005/387/JHA) on new psychoactive substances (24).4 Recommendations4.1 The Government should consider new legislation, separate from the Misuse of Drugs Act,to control the supply and manufacture of ‘legal highs’, but not penalise possession. Theexperience in other countries of restricting novel substances may provide a way forward.4.2 Analogue legislation is not considered to be an appropriate method of controlling newsubstances. The concept of a substance being “substantially similar” to a controlled drugrelies essentially on individual opinions and is not strictly amenable to scientific evaluation.4.3 Current official statistics (e.g. household surveys, seizures, offenders, mortality) areinsufficiently comprehensive to assess the prevalence of new substances.4.4 The impact of import bans, if not drug legislation in general, should be measured todetermine “what works”.4.5 The Government should consider funding basic research into the pharmacology andtoxicology of selected new substances. This would support Temporary Class Drug Orders,and might form an extension of the Government’s existing ‘Forensic Early Warning System’.5. References1. European Commission (2005). Council Decision 2005/387/JHA on the informationexchange, risk-assessment and control of new psychoactive substances. Official Journal of theEuropean Union, L 127/32 42. King, L.A., and Sedefov, R. (2007). Early-Warning System on New PsychoactiveSubstances: Operating Guidelines, EMCDDA, Lisbon 53. EMCDDA (2011). EMCDDA-Europol 2010 Annual Report on the implementation ofCouncil Decision 2005/387/JHA 64. Smith, K. and Flatley, J. (2011). Drug Misuse Declared: Findings from the 2010/11 BritishCrime Survey, England and Wales. <strong>Home</strong> Office 75. Coleman, K. (2011). Seizures of drugs in England and Wales, <strong>Home</strong> Office StatisticalBulletin, (HOSB 17/11) 86. Office for National Statistics (2011). Deaths related to drug poisoning in England andWales, 2010 97. King, L.A., and Kicman, A.T. (2011). A brief history of 'new psychoactive substances’.Drug Testing and Analysis, 3(7-8), 401-4038. Nutt, D. (2010). Precaution or perversion: eight harms of the precautionary principle. 104 www.emcdda.europa.eu/html.cfm/index5173EN.html?pluginMethod=eldd.showlegaltextdetail&id=3301&lang=en&T=25 www.emcdda.europa.eu/html.cfm/index52448EN.html6 www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/searchresults?action=list&type=PUBLICATIONS&SERIES_PUB=a1047 www.homeoffice.gov.uk/publications/science-research-statistics/research-statistics/crimeresearch/hosb1211/hosb1211?view=Binary8 www.homeoffice.gov.uk/publications/science-research-statistics/research-statistics/policeresearch/hosb1711/hosb1711?view=Binary9www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/subnational-health3/deaths-related-to-drug-poisoning/2010/stb-deaths-related-to-drug-poisoning-2010.html514

9. European Commission (2000). Communication from the Commission of 2 February 2000on the precautionary principle. 1110. United Kingdom Government (2011). The Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act2011 (Commencement No. 1) Order 2011. 1211. Editorial, (2010). A collapse in integrity of scientific advice in the UK.Lancet, 375, 131912. United Kingdom Government (2010). Import ban of Ivory Wave drug 2-DPMPintroduced. 1313. United Kingdom Government (2011). Phenazepam. 1414. Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (2011). Further advice on Diphenylprolinol(D2PM) and Diphenylmethylpyrrolidine. 1515. Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (2011). Consideration of the NovelPsychoactive Substances (‘Legal Highs’). 1616. Beck, H. (2011). Drug enforcement in an age of austerity: Key findings from a survey ofpolice forces in England. UK Drug Policy Commission, London. 1717. Government of Ireland (2010). Criminal Justice (Psychoactive Substances) Act. 1818. Bassindale, T. (2011). Benzylpiperazine: The New Zealand legal perspective. DrugTesting and Analysis 3(7-8), 42819. New Zealand Law Commission (2011). Controlling and regulating drugs: A review of theMisuse of Drugs Act 1975, Report 122. Wellington, New Zealand. 1920. Hughes, B., and Malczewski, A. (2011). Poland passes new law to control ‘head shops’and ‘legal highs’. Drugnet Europe online 73, EMCDDA 2021. Kikura-Hanajiri, R. (2011). Drug Control in Japan – Designated Substances – Update.Presented at the First International Multidisciplinary Forum on New Drugs, EMCDDA,Lisbon, May 201122. Reitox National Focal Point, Sweden (2010). National report (2009 data) to theEMCDDA; New Development, Trends and in-depth information on selected issues 2123. Hughes, B. (2011). Legal Responses to New Psychoactive Substances in EU: Theory andpractice—typologies, characteristics and speed. Presented at the First InternationalMultidisciplinary Forum on New Drugs, EMCDDA, Lisbon, May 201110 http://profdavidnutt.wordpress.com/2010/06/11 http://europa.eu/legislation_summaries/consumers/consumer_safety/l32042_en.htm12 www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2011/2515/contents/made13 www.homeoffice.gov.uk/media-centre/press-releases/ivory-wave14 www.homeoffice.gov.uk/drugs/drug-law/phenazepam/15 www.homeoffice.gov.uk/publications/agencies-public-bodies/acmd1/acmd-d2pm?view=Binary16 www.homeoffice.gov.uk/publications/agencies-public-bodies/acmd1/acmdnps2011?view=Binary17 www.ukdpc.org.uk/resources/Drug_related_enforcement.pdf18 www.irishstatutebook.ie/2010/en/act/pub/0022/index.html19 www.lawcom.govt.nz/sites/default/files/publications/2011/05/part_1_report_-_controlling_and_regulating_drugs.pdf20 www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/drugnet/online/2011/73/article1221 www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_142550_EN_SE-NR2010.pdf615

24. European Commission (2011). European Commission seeks stronger EU response to fightdangerous new synthetic drugs. Press release, 25 October. 22December 201122 http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=IP/11/1236&type=HTML716

Written evidence submitted by Professor David Hannay [DP004]Attached is a memorandum I wrote in 2007 for circulation to all political parties at the time of anelection.I am a retired GP who qualified in London, worked for 16 years in Glasgow, then 10 years inSheffield as Professor of General Practice, before returning to South West Scotland as a rural GP.The figures in the memorandum are out of date, but the situation is if anything worse and thearguments for a change in policy remain.The Heroin Holocaust—A Drug Disaster(The need to medicalize heroin addiction)BackgroundIntroductionThe word drug is used for substances that alter mood, of which some are legal such as alcoholand tobacco, whereas others are illegal such as heroin, cocaine and cannabis. Amongst illegaldrugs some like heroin are called hard drugs because they cause high dependence, and others likecannabis are considered as soft drugs because they are less addictive. As well as the extent towhich they cause dependence, the harm which drugs cause may be short term or long term.Legal DrugsWhether drugs are legal or not, depends as much on social and cultural norms as on the amount ofharm they cause. For instance, cigarette smoking causes little dose related harm in the short termbeyond the irritation of tobacco smoke, but the long term cumulative effects are devastating. Ithas taken a generation for us to realize that cigarette smoking kills thousands of people a yearthrough lung cancer, respiratory disease and heart attacks. But nicotine is addictive and in spite ofprice rises and health warnings, many find it difficult to stop smoking.The other legalized drug of alcohol has a different profile of harm. Unlike nicotine the short termeffects of excess alcohol are dramatic behavioural change with loss of control and drunkenness,which in turn leads to violent crime and road deaths. Unlike cigarettes, the long term effects ofalcohol in moderation may be beneficial to health, but a minority will develop a compulsivedependence causing long term social and physical harm such as liver cirrhosis, which isincreasing.Because of their harmful effects, there are controls on legal drugs, such as prohibition on sellingto children, licensing laws, and the recent ban on smoking in public places. But huge industrieshave grown up for the production, supply, and retail of the legalized drugs of tobacco andalcohol.Illegal drugsThe same considerations of harm and dependency apply to other mood altering substances whichhave been deemed illegal and are controlled by the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. This classifiesillegal drugs into three classes with a graduation of penalties for their supply and possession.Those viewed as the most dangerous and harmful are in Class A (eg. Heroin and Cocaine); inclass B those seen as less serious (eg. Amphetamine and Codeine) and the remainder in Class Cas the least harmful (eg. Benzodiazapines and Cannabis). The act makes it unlawful to posses orsupply these drugs unless prescribed by a doctor, and makes provision for the notification ofaddicts and the establishment of special clinics.17

Of these drugs Cannabis was reclassified from Class B to Class C in 2002, which caused the then"Drugs Tsar" to resign in protest. The medical use of cannabis has also been contentious. But it isClass A drugs which cause the most harm. The use of Cocaine has grown dramatically withincreasing seizures and a lowering of price. In 2000 there were 4 deaths in Scotland due toCocaine but in 2005 this had grown to 44, approximately 15% of all drug deaths. However, by farthe greatest harm done to individuals and society is caused by heroin and society's reactions to it.Results of the holocaustPrevalenceThe proportion of addicts reporting heroin use has grown annually since 1975 with increasingnumbers injecting. Heroin costs one third of the price ten years ago. Every day in Scotland, 100people are caught in possession of illegal substances, a 7% increase on the previous year. In theUK there are now about 350,000 registered heroin addicts of whom 60,000 are in Scotland, whichis twice the proportion south of the border. In addition, it is estimated that 50,000 children inScotland have one or more parents addicted to heroin. However, the number of registered addictsconsiderably underestimates the true prevalence. Nor is this just a problem of inner cities. One ofthe most affected areas is Dumfries and Galloway, where heroin addiction started to rise in the1980s and it is estimated that 7% of 15-25 year olds are now addicted, with 1,000 users inDumfries alone. This is in spite of the success of the local police force in seizing supplies andjailing dealers. The number of people seeking help in the region is 14% above the nationalaverage with 89% new users being teenagers. But there is a three-month waiting list for the localNHS clinic.DeathsThe number of deaths due to heroin in Scotland rose from 84 in 1996 to 225 in 2004. InEdinburgh alone there were 40 more deaths from heroin than the previous year. In Dumfries &Galloway the average age of death from heroin addiction is 29 with a range from 17-42 years. Aswell as having twice the rate of heroin addiction, Scotland has twice the suicide rate of England,with many suicides being drug related.CrimeOver the past five years there has been a steady rise in drug related crime. Over the same period,violent crime in woman has risen by 50%, mainly due to stealing and prostitution caused by druguse. It costs on average £40 a day to maintain a heroin habit or £280 a week. Of this £80 maycome from state benefits leaving £200 a week or £10,000 a year to be found mainly from stealing,low level dealing, and prostitution. In the UK retailers lose £2.1 billion from shoplifting, much ofit drug related. It has been estimated that 90% of prostitutes do so to afford their heroin addiction.Most of the prostitutes recently killed in Glasgow and Ipswich were heroin addicts, many onmethadone.As a result, Scottish jails are awash with heroin and have been called drugs supermarkets. Thereare now 7,200 in Scottish jails of which 70% suffer from drug addiction, which is not surprisingas it is drug related crime that has led to their imprisonment. The prisons are overcrowded and wewill soon need 1,000 extra places with a new prison costing £160 million. 45% of prisoners arere-convicted within 2 years, about half for drug offences.CostsThe annual cost to the state of one young heroin addict is estimated to be £26,000. As the averagelength of addiction is 13 years, this comes to a staggering £325,000 per addict. The annual cost18

does not take into account the value of stolen goods and is made up as follows: Prison 4months—£12,000; State benefits 8 months—£3,000; Housing benefit—£3,000; Probation/Socialwork—£2,000; Methadone—£2,000; Legal aid, Court costs, Police costs, Council tax benefits—£1,000 each.Reactions to the holocaustControl and TreatmentThe emphasis of society's response has been to try to control heroin addiction and to care foraddicts with a combination of legal penalties and treatment. The mainstay of treatment ismethadone, usually prescribed in special clinics. It is highly addictive, but can be taken by mouthonce a day, instead of heroin which has a shorter half life. There are 20,000 addicts in Scotlandon methadone which costs £2,000 a year, or a total of £40 million a year and the number ofprescriptions are rising. There is evidence that methadone reduces mortality and criminality, butit also de-motivates and only 3% come off the programme.Methadone is also a method of control with supervised consumption in pharmacies and urine testsfor other illegal substances which may lead to suspension from clinics. To this humiliation is theadded fact that often the dose of methadone is insufficient to prevent the additional use of illegaldrugs. It may also take three to eight months to get an appointment. The debate continuesbetween harm reduction and withdrawal to abstinence, for which other drugs such asdihydrocodeine and naltrexane have been used and even low level electric stimulation.There have been recent attempts to improve treatment facilities with £60million voted by theScottish <strong>Parliament</strong> last year to increase rehabilitation facilities. At the same time, othersadvocate more controls such as contraception prescribed with methadone and on the spot fines forpossession. The former suggestion ignores human rights and the latter would only increase crimeto pay for the fines.Some politicians advocate drug free prisons with mandatory drug testing, but the majority ofprisoners are there as a result of addiction mainly to heroin. Even on-the-spot fines have beenopposed on the basis that anyone possessing heroin should be prosecuted through the courts. Amore constructive approach has been to replace prison sentences with Drug Treatment andTesting Orders, which have been shown to cut reconviction rates.However, none of these approaches addresses the fundamental problem which is that the presentlegal basis of criminalizing possession of a highly addictive drug such as heroin inevitably createsa flourishing black market, so that users are driven to criminal activity in order to fund theircraving. And yet all the official responses have ignored this fundamental fact and concentrated oncontrol, with the language of conflict such as "a war on drugs" and the appointment of "drugtsars".In 1999 the Scottish Drug Enforcement Agency was launched, followed in 2001 by the ScottishExecutive's Effective Intervention Unit with guidance on shared care arrangements, all essentiallyabout control. In the same year Dumfries & Galloway published a glossy multi-agency Alcoholand Drugs Strategy with an emphasis on harm reduction, which now involves multiple stakeholders such as the Police, Social Work, Health Professionals, and the Voluntary Sector.At the same time the Royal College of General Practitioners were promoting a "Certificate in theManagement of Drug Misuse", again with the emphasis on control. Last year's annual report fromthe Scottish Drug Forum, which co-ordinates policy and information for the voluntary sector,19

described policy developments and initiatives in training, support and research. But nowhere werequestions raised about the legal basis of our current response to heroin addiction.New DirectionsFortunately there have been voices in authority speaking out against the present situation.Scotland's drug tsar, Tom Wood, has stated that the war on drugs is being lost. "The currentsystem has a limited impact on reducing the massive crime, health and social harm caused". Twoyears ago Lord McCluskey, a former high court judge, called for the legalization or rathermedicalization of heroin which the previous year had accounted for two thirds of the 56 drugrelated deaths with methadone involved in one fifth. In the 1970s there were no such deaths butthe figure is now more than one a day.Other countries have adopted new approaches to the problem of heroin addiction, and movedaway from reliance on methadone alone. In Australia and Canada they have started supervisedinjection clinics. In Holland the co-prescription of heroin with methadone has been found to becost effective compared to methadone alone for chronic heroin addicts. Unlike the UK, the Dutchspend more on services and less on enforcement. In Switzerland they have medicalized heroin byproviding it on prescription, which has resulted in a 60% reduction in drug related crime, and adrop of 70% in the prison population. However, a referendum showed that the majority wereagainst legalizing the drug as opposed to medicalizing it.Last year the <strong>Parliament</strong>ary Science and Technology <strong>Committee</strong> criticized the Advisory Councilon the Misuse of Drugs, and called for a major overhaul of the present system of classifyingdrugs, so that alcohol and tobacco would be included to reflect the harm they cause compared toillegal drugs. Alcohol is half as expensive as it was 25 years ago during which time drink relateddeaths have more than trebled. The maternal use of tobacco results in a greater reduction in birthweight than heroin. Together alcohol and tobacco cause about 40 times the total number of deathsthan all illegal drugs combined.The recent multidisciplinary report from the Royal Society of Arts, recommended that the Misuseof drugs Act 1971, should be replaced by a new Misuse of Substances Act which ranked alldrugs, both legal and illegal, according to the harm they caused. On this scale alcohol and tobaccowere more dangerous than cannabis, but the most harmful of all was heroinConclusionsThe problemA holocaust is defined as wholesale sacrifice and destruction. As a society we are sacrificing liveson the altar of our prejudices at enormous cost to the state, and in the process destroying the lifechances of thousands of mainly young people. The problem with criminalizing a highly addictivedrug like heroin is that inevitably a black market is created so that users are driven to crime,prostitution or low level dealing to fund their craving. Indeed, it is difficult to think of a betterway of encouraging crime or creating pyramid selling.The problem is not so much illegal drugs as illegal drug money. This is not to say that suppliersshould not be pursued with the full force of the law and their assets seized, but there would belittle need for dealers, if heroin was available for those who needed it. This need arises becauseusers soon become mentally and physically distressed if they can not get the drug. Given this factit is extraordinary that we still use the language of confrontation and control to table theproblems. On the one hand we stigmatize addicts as criminals, and on the other hand provideclinics, mainly based on methadone which may be as addictive as heroin but can conveniently be20

taken orally once a day. Such clinics are often difficult to access and tend to be highlycontrolling.SolutionsThere are no easy solutions, but it is clear the present policies are a failure by any standard, letalone harm reduction. In the early 1970s when the Misuse of drugs Act was passed there wereless than 500 known heroin users. Four decades later there are something like 500,000 addictsand an estimated £10billion a year going into the pockets of criminals. This is madness on amassive scale. Disastrous failures require drastic remedies.Firstly, the possession and use of heroin should cease to be a criminal offence. Decriminalizingpossession would remove large numbers of offenders from the courts and prison.Secondly, heroin should be prescribed on the NHS for those who want it. This would require theestablishment of injecting clinics in each locality, with help for those who wanted to come offheroin which most addicts do. Such facilities would destroy the need for a black market.These two measures alone would transform the situation, but would require a sea change inattitudes for the law, police and the medical and caring professions. As drug policy in Scotland isreserved to Westminster, the change in law would have to be UK wide, quite apart from the factthat decriminalizing possession in only one part of the UK would tend to attract users from otherparts.The prescription of heroin on the NHS would require a change in the medical approach, so that itbecame more caring and less controlling. If heroin addiction were considered a disease then itwould not be acceptable to suspend patients from clinics for taking other drugs tested in urine,any more than it would be acceptable to stop treating diseases caused by smoking if patientscontinued to smoke. The new general practice contract has given doctors more free time and morepay, which should make it feasible to base such clinics in primary care.Recently some addicts met farmers from Afghanistan from where 80% of heroin in the UKoriginates. If this were purchased by the government for prescription by the NHS, then one sourceof funding for terrorism in Afghanistan would also be undermined.It is important to emphasize that it is not suggested that heroin should be legalized which wouldstart an unstoppable industry as has happened with tobacco. Nor is it suggested that illegalsuppliers should not be rigorously pursued and prosecuted. Rather this is a plea that heroinpossession and use should be medicalized rather than criminalized. Such a change in law wouldgreatly reduce crime and pressures on the police and prison services. It would also require doctorsto treat addicts as patients with an illness, rather than as deviants who need to be controlled.April 200721

Written evidence submitted by Daniel Haynes [DP006]The law on drugs must be based on science and evidence.Cannabis and other drugs must be regulated and taxed.Give police more time, give regulated clean healthier drugs, remove drug gangs and dealers, give theGovernment control of the drug industry also give billions of pounds in taxes.Please stop being out of touch with the modern world and wake up.Thank you for reading my personal opinion also I’m sure millions of other people's opinion inEngland.December 201122

Written evidence submitted by Dhiresh Tailor [DP007]Hello, my name is Dhiresh Tailor and I am writing as a well knowledged cannabis user, outraged bythe ignorant drug laws today (on cannabis).How can someone who doesn't know the correct facts about cannabis or who has never taken it,comment on its full dangers; because that is the level of sophistication shown by the UK governmentand other governments all around the world. It is time for us to all wake up, take in the real facts andbe adults about it.The least we can do is compare it to alcohol and cigarettes, both taxed drugs.These two drugs are some of the biggest leaders of death, but they are a choice which people take ifthey wish.This is exactly the same way we need to look at cannabis. Also keep in mind that no one has ever dieddirectly from cannabis use or cannabis overdose (which is impossible, because you would have tosmoked around £200,000 of cannabis in one hour to die—which we all can say is pretty impossible).It is a safe therapeutic drug, I have used large amounts and have functioned well—never to findmyself with side effects the next morning.You find people from all parts of today's society—mothers, fathers, uncles, aunties and evengrandparents smoking or eating cannabis today. Cannabis does not segregate, people from all aroundthe world have used it. It dates back 4,000 years ago, and if that is not culturally significant then whyshould alcohol be legal?Safer ways to consume it have been made, with the best being 'vaporizers' which only extract a thinvapour of Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and leave behind all carcinogens (possible cancer causingagents).There are two reasons to why cannabis is still illegal in my opinion.The first is the simple fact that it is very hard for the government to go back on itself after decades ofmaking a harmless drug illegal. They simply don't have the courage to admit that a mistake has beenmade. The easy way is to keep it illegal and spread rumours about 'brain damage', 'potential forcancer'—where scientific research has found the exact opposite, where 'brain growth' has beenattributed to cannabis use and cancer treatment/curing.The second is that there are too many companies and corporations which are making money fromcannabis being illegal ($'s and £'s are clearly more important than the truth).Do you think 1,000s of pharmaceutical drugs would be useless when cannabis could be used to treatailments—safely. This is billions of pounds of loss for a pharmaceutical company.There are even more examples I can give if needed.I ask whoever reading this just to do one thing. Read the real facts and inform your higher order.Please at least show some sympathy for the people in jail for having a joint.Thank you for your time.December 201123

Written evidence submitted by Andy McKay [DP008]I write to you today from outside the Westminster bubble, and aside from the pressures ofpolitical office to warn you that prohibition has inevitably failed. Many millions up and downthe country do drugs every week, some with relatively harmless outcomes, others withoutcomes disastrous to local communities full of ordinary people.It would be stupid to pretend that the decriminalisation of some or all drugs would result insome unachievable haven of zero usage. Humans are and have always been experimentalcreatures and drugs will be smoked, injected, swallowed and whatever else regardless of law.In fact, many of your colleagues in parliament are proof of this having dabbled in their youthwith cannabis. However, what decriminalisation can do is reduce drug related crime, reducethe instance of drug related health issue and reduce hard drug usage.Drug related crime is a huge issue. Every year billions is needlessly poured into cartels whouse it to fund their other endeavours. It has been estimated in the past that as much as£6billion is spent each year by British citizens on cannabis alone. All of this goes in thepockets of gangs to fund gun crime and trafficking among other offences damaging the UKas a whole financially and morally. This rips apart communities as gangs compete for supplyroutes and trade. This financial cost does not even include the hundreds of millions a yearspent tackling drugs supply in the UK. To decriminalise drugs such a cannabis would givethose who wish to experiment (as people inevitably always do) a non-pressured way topurchase cannabis which does not contribute to funds which support countless misery tomany people around the world. It would also be in a relaxed environment where no pressureis felt by dealers who want to push harder drugs. If cannabis was legalised it could be taxedand the money used to actually solve the problem of hard drug usage. Countries like theNetherlands where a more relaxed approach to soft drugs like cannabis has been takenexperience a much lower rate of problematic and hard drug usage than comparable countries.Crime by those individuals addicted to harder drugs such as heroin is also a massive issue.However, more relaxed supply clinic trials in the past have led to a massive reduction incrime within areas in which the trials have taken place as well as a reduction in heroin usagewhich can only be a good thing for the individual and the community.Health issues are also a problem, especially where needles are in usage leading to the spreadof HIV among other conditions. Also, as the industry is unregulated and run by those whoonly have their eye on their margins and not on their ‘customers’ welfare, many drugs are cutwith other much more damaging substances leading to larger problems than taking theoriginal drug would have led to in the first place.In the past, governments have ignored the advice of experts, even going as far as to sack one(Professor David Nutt) for speaking from his expert view. I urge you this time to look at theevidence from a neutral standing point to come up with a policy which does not lead tohigher rates of hard drug usage and the funding of criminal gangs.We both want the same thing. We both want the lowest incidence possible of problematicdrug usage from alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, heroin, cocaine and any other drug going. Butprohibition only aggravates the problem and the state of the UK relationship with drugs isonly evidence to this. When it is easier for a young person to buy cannabis than it is topurchase tobacco or alcohol, it is evident that something is very wrong. A new direction is24

needed if a solution is wanted. To avoid the correct, but brave decision would be to sentencethe problem to further escalation. Do not be afraid of the knee-jerk reaction and make arecommendation that is right for the UK and it’s communities in the long term.December 201125

Written evidence submitted by Joe Milburn [DP009]In my opinion the UK's drugs policy is fatally flawed in many ways and does much more harm thangood. This harm is not only felt in the drug consuming community but in society as a whole. As aconsumer of Cannabis I am constantly facing threats from all sides, threats of persecution at the handsof an uneducated society, threats of prosecution from a police force who are enforcing a pointless lawand most unnerving, I face threats from the suppliers of my Cannabis. I can deal with the first two, ifsomebody wants to victimize me for my choice they can but I am not forced to care. If I get caught inpossession of Cannabis, I can deal with it, just take the wrap and face the consequences, but I cannotdo anything about the suppliers. The people I entrust to manufacture and distribute my drugs are forthe most part very dangerous and most certainly the kind who are unlikely to have a customercomplaints division.I am talking about the gangs who are forever chasing a profit that is so easy for them to make as aresult of prohibition. This pursuit of profit has no boundaries, no regulations and no conscience. Onmany occasions I have bought Cannabis that has been laced with contaminants such as glass, grit,road paint and many other despicable chemicals to boost the appearance and weight of the specimen.Why should a plant that has been proven harmless on many occasions be entrusted to a group ofpeople with no regard for the health of its consumers? For the sake of abandoning party politics thiscountry could prevent a lot of unnecessary suffering and also profit greatly from taxation of aregulated market and the reduced expenditure of having to deal with this unnecessary laws.Like many other users of Cannabis in particular I am forced to keep lining the pockets of thesemobsters for low quality and potentially dangerous products. In many of the more serious cases thismoney goes straight towards funding horrific acts such as human trafficking, protection rackets, childlabour, gun crime and in some extreme cases terrorism. Wouldn't my £20 a week be better in thepockets of the government who could very much do with the money right now? Regulation is provento be a much better and productive strategy than prohibition which has been proven time and timeagain to be harmful to society so it begs the question, why are we still enacting prohibition?Give people a choice, let them choose the healthier option and let it actually be healthy. As a user ofcannabis only I cannot testify the effects of prohibition on other drug markets but contamination andimpurity is an issue across the board. Many substances are only made unhealthy as a result ofprohibition.December 201126