DescarcÄ revista în format PDF - idea

DescarcÄ revista în format PDF - idea

DescarcÄ revista în format PDF - idea

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

wartæ + societate / arts + society# 25, 2006 20 RON / 11 €, 14 USD

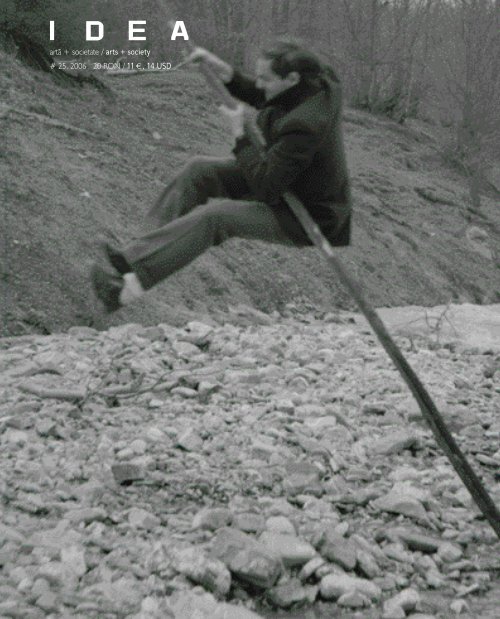

Irwin Corpse of Art, mixed media, 2003, Reconstruction of the Kasimir Malevich in coffin made according, Suetin’s plan as he was exhibited in the House of Artists Union in Leningrad in 1935,photo: Jesko Hirschfeld, courtesy: Gallery Gregor PodnarOn the cover: Ion Grigorescu Træisteni (series of photographies), 1976, credit: the author

Aspirafliile celor care ar vrea sæ izoleze arta de lumea socialæ sînt asemænætoare cu cele ale porumbelului luiKant ce-øi imagina cæ, odatæ scæpat de forfla de frecare a aerului, ar putea zbura cu mult mai liber. Dacæ istoriaultimilor cincizeci de ani ai artei ne învaflæ ceva, atunci cu siguranflæ cæ ea ne spune cæ o artæ detaøatæ delumea socialæ e liberæ sæ meargæ unde vrea, numai cæ nu are unde sæ meargæ. (Victor Burgin)The aspirations of those who would isolate art from the social world are analogous to those of Kant’s dove which dreamed of how muchfreer its flight could be if only were released from the resistance of the air. If we are to learn any lesson from the history of the pastfifty years of art, it is surely that an art unattached to the social world is free to go anywhere but that it has nowhere to go. (Victor Burgin)

arhiva 5 Arta conceptualæ 1962–1969: De la estetica administrærii la critica institufliilorCONCEPTUAL ART 1962–1969: FROM THE AESTHETIC OF ADMINISTRATION TO THE CRITIQUE OF INSTITUTIONSBenjamin H. D. Buchloh23 Replicæ lui Benjamin Buchloh despre arta conceptualæREPLY TO BENJAMIN BUCHLOCH ON CONCEPTUAL ARTJoseph Kosuth & Seth Siegelaub27 Ræspuns lui Joseph Kosuth øi lui Seth SiegelaubREPLIES TO JOSEPH KOSUTH AND SETH SIEGELAUBBenjamin Buchlohgalerie 30 Ion Grigorescu: O versiune a memoriei (ianuarie 2007)A VERSION OF MEMORY (JANUARY 2007)scena 55 ¡Etranjero Ven a Votar!Lucian Maier61 Indirect cu direcflieINDIRECT WITH DIRECTIONJudith Schwarzbart66 Irwin: nimic personal. O discuflie cu Miran Mohar øi Borut VogelnikIRWIN: NOTHING PERSONAL. A CONVERSATION WITH MIRAN MOHAR AND BORUT VOGELNIKAlexandru Polgár80 Fericiflii credincioøi. Un interviu cu Solvej Helweg Ovesen realizat de Henrikke NielsenHAPPY BELIEVERS. AN INTERVIEW WITH SOLVEJ HELWEG OVESEN BY HENRIKKE NIELSEN86 Interviu cu Katharina Schlieben øi Sønke Gau, echipa curatorialæ de la ShedhalleINTERVIEW WITH KATHARINA SCHLIEBEN AND SØNKE GAU, CURATORIAL TEAM OF SHEDHALLEcode flow – Dimitrina Sevova & Alain Kessi94 Wirklich – În mod real. Hans Haacke, lucræri 1959–2006, Akademie der Künste, BerlinWIRKLICH – REALLY. HANS HAACKE, WORKS 1959–2006, AKADEMIE DER KÜNSTE, BERLINVlad Morariu107 Pawel Althamer: istoria unui workshop, din pædurea Plochocinek pînæ la Centrul Georges PompidouPAWEL ALTHAMER: THE HISTORY OF A WORKSHOP. FROM THE FOREST OF PLOCHOCINEK TO THE CENTRE GEORGES POMPIDOUClaire Staeblerinsert 114 Andrea Faciu: Steag de oameniHUMAN FLAG

+ 117 Despre Avertissement: interviu cu Daniel BurenON THE AVERTISSEMENT: INTERVIEW WITH DANIEL BURENMaria Eichhornverso: (in)securitatea vieflii. 138 Vivre dangereusement. Violenfle øi victime în regimurile securitarede la biopoliticæ la politicile securitareVIVRE DANGEREUSEMENT. VIOLENCE AND VICTIMS IN SECURITY REGIMES(in)security of life. Ciprian Mihalifrom biopolitics to security politics149 Ontologia prezentului. Comunitate øi imunitate în epoca globalæONTOLOGY AT PRESENT TENSE. COMMUNITY AND IMMUNITY IN THE GLOBAL TIMESRoberto Esposito156 Un oraø nesigurAN INSECURE CITYJérôme Lèbre166 Politica øi poliflia mondializærii(cîteva remarci asupra nofliunilor de fricæ, insecuritate øi risc în zilele noastre)POLITICS AND POLICE OF GLOBALIZATION(A FEW REMARKS ON THE NOTIONS OF FEAR, INSECURITY AND RISK IN OUR TIMES)Michel Gaillot178 Zone de nondiferenfliere. Lumea în „starea de excepflie“:despre relafliile dintre „populism“, „sferæ publicæ“ øi „terorism“ZONES OF INDIFFERENCE. THE WORLD IN A “STATE OF EXCEPTION”:ON THE RELATIONS OF “POPULISM”, “PUBLIC SPHERE” AND “TERRORISM”Marius Babias185 A fi sau a nu fi: aceasta-i întrebarea?TO BE OR NOT TO BE: IS THIS THE QUESTION?Alex. Cistelecan191 Securitatea individului øi securitatea statului, o relaflie ambivalentæHUMAN SECURITY AND STATE SECURITY, AN AMBIVALENT RELATIONSHIPMarc Crépon203 Existenfla într-un tancEXISTENCE INSIDE A TANKAlexandru Polgár

IDEA artæ + societate / IDEA arts + societyCluj, #25, 2006 / Cluj, Romania, issue #25, 2006Editatæ de / Edited by:IDEA Design & Print Cluj øi Fundaflia IDEAStr. Dorobanflilor, 12, 400117 Cluj-NapocaTel.: 0264–594634; 431661Fax: 0264–431603Redactor-øef / Editor-in-chief: TIMOTEI NÆDÆØANe-mail: <strong>idea</strong>magazine@gmail.comRedactori / Editors:ALEX. CISTELECANCIPRIAN MIHALICIPRIAN MUREØANADRIAN T. SÎRBUANDREI STATEATTILA TORDAI-S.Redactori asociafli / Contributing Editors:MARIUS BABIASAMI BARAKCOSMIN COSTINAØDAN PERJOVSCHIALEXANDRU POLGÁROVIDIU fiICHINDELEANUColaboratori permanenfli / Special Contributors:AUREL CODOBANBOGDAN GHIUG. M. TAMÁSConcepflie graficæ / Graphic design:TIMOTEI NÆDÆØANAsistent design / Assistant designer:LENKE JANITSEKCorector / Proof reading:VIRGIL LEONWeb-site:CIPRIAN MUREØANIDEA artæ + societate este parte a proiectului editorial documenta 12 magazinesIDEA arts + society is a contributor to documenta 12 magazinesTextele publicate în aceastæ revistæ nu reflectæ neapærat punctul de vedere al redacfliei.Preluarea neautorizatæ, færæ acordul scris al editorului, a materialelor publicate în aceastæ revistæ constituieo încælcare a legii copyrightului.Toate articolele a cæror sursæ nu este menflionatæ constituie portofoliul revistei IDEA artæ + societate Cluj.Difuzare / Distribution:NOI Distribuflie, BucureøtiTel./Fax: 021 222 8984021 222 7998Comenzi øi abonamente / Orders and subscriptions:www.<strong>idea</strong>magazine.roTel.: 0264–431603; 0264–4316610264–594634ISSN 1583–8293Tipar / Printing:Idea Design & Print, Cluj

arhivaArta conceptualæ 1962–1969:De la estetica administrærii la critica institufliilor*Benjamin H. D. BuchlohTextul de faflæ este traducerea studiului„Conceptual Art 1962–1969: From theAesthetic of Administration to the Critiqueof Institutions“, din October, vol. 55 (iarna1990), pp. 105–143.© MIT PRESS Journals,Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007Acest monstru numit frumusefle nu-i etern. Øtim cæ suflarea noastræ nu are-nceput øi nu se va opri niciodatæ,însæ, dincolo de toate, ne putem închipui crearea lumii øi sfîrøitul ei. (Apollinaire, Les peintres cubistes)Alergicæ la orice reîntoarcere la magie, arta ia parte la øi e parte a dezvræjirii lumii, pentru a folosi sintagmalui Max Weber. Ea este indisolubil legatæ de raflionalizare. Mijloacele øi metodele productive pe care arta leare la dispoziflie provin în totalitate din acest nexus. (Theodor Adorno)O distanflæ de douæzeci de ani ne desparte de momentul istoric al artei conceptuale. Este o distanflæ care nepermite øi, totodatæ, ne obligæ sæ examinæm istoria acestei miøcæri dintr-o perspectivæ mai cuprinzætoare decîtaceea a concepfliilor desfæøurate de-a lungul decadei în care a apærut øi s-a manifestat (aproximativ din 1965pînæ la dispariflia sa temporaræ, în 1975). Pentru cæ o istoricizare a artei conceptuale reclamæ, înainte de toate,o clarificare a extinsei game de poziflionæri adesea conflictuale øi a tipurilor de cercetare reciproc exclusive generateîn decursul aceastei perioade.Însæ, dincolo de aceasta, existæ probleme mai vaste, care flin de metodæ øi de „interes“. Fiindcæ, în acest punct,orice istoricizare trebuie sæ ia în considerare ce tip anume de întrebare poate pune sau cærei întrebæri poatespera, legitim, sæ-i ræspundæ o abordare istoricæ a artei – bazatæ, de obicei, pe studiul obiectelor vizuale –, încontextul practicilor artistice care au insistat în mod explicit sæ fie tratate în afara parametrilor de producere aobiectelor perceptive, ordonate formal øi, cu siguranflæ, în afara acelora ai istoriei øi criticii de artæ. Øi, în plus,o asemenea istoricizare mai trebuie sæ interogheze øi valabilitatea obiectului istoric, adicæ motivaflia de a redescoperiarta conceptualæ din perspectiva sfîrøitului anilor 1980: dialectica ce leagæ arta conceptualæ, dreptcea mai riguroasæ eliminare a vizualitæflii øi a definifliilor tradiflionale ale reprezentærii, de aceastæ decadæ a uneirestauræri destul de violente a formelor artistice tradiflionale øi a procedurilor de producflie.Se întîmplæ, desigur, în cubism ca, pentru prima datæ în istoria picturii moderniste, elemente ale limbajului sæiasæ programatic la suprafaflæ în interiorul cîmpului vizual, într-un proces care poate fi privit drept o moøtenirea lui Mallarmé. Øi tot aici se instituie o paralelæ între nou-apæruta analizæ structuralistæ a limbajului øi examinareaformalistæ a reprezentærii. Însæ practicile conceptuale au trecut dincolo de o asemenea cartografie a modeluluilingvistic asupra modelului perceptiv, distanflîndu-se de spaflializarea limbajului øi temporalizarea structurii vizuale.Întrucît ceea ce-øi propunea, prin natura sa, arta conceptualæ viza înlocuirea obiectului experienflei spafliale øiperceptive doar printr-o definiflie lingvisticæ (lucrarea ca propoziflie analiticæ), ea a reprezentat astfel atacul celmai plin de consecinfle asupra statutului acestui obiect: vizualitatea sa, statutul sæu de marfæ øi forma sa de distribuflie.Confruntîndu-se, pentru întîia oaræ, cu întregul øir al implicafliilor moøtenirii lui Duchamp, practicile conceptualeau reflectat, în plus, asupra construcfliei øi rolului (sau morflii) autorului la fel de mult pe cît au redefinit condifliilereceptærii øi rolul spectatorului. Astfel, ele au realizat cea mai riguroasæ investigare a convenfliilor reprezentæriipicturale øi sculpturale din perioada postbelicæ, dublatæ de o criticæ a paradigmelor tradiflionale ale vizualitæflii.Încæ de la început, faza istoricæ în care s-a dezvoltat arta conceptualæ cuprindea un asemenea set complex deabordæri care se opuneau unele celorlalte, încît orice încercare de evaluare retrospectivæ trebuie sæ ignore ræsunætoarelevoci (în special cele ale artiøtilor înøiøi) ce pretind respect faflæ de puritatea øi ortodoxia miøcærii. Tocmaidatoritæ acestui set de implicaflii ale artei conceptuale e necesaræ rezistenfla la o construcflie a istoriei saleîn termenii unei omogenizæri stilistice, care ar limita acea istorie la un grup de indivizi øi la un set de practici øi* O versiune timpurie a acestui eseu a fost publicatæ în L’art conceptuel: une perspective, Paris, Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1989.BENJAMIN H. D. BUCHLOH este istoric de artæ, recunoscut internaflional ca unul dintre cei mai importanfli exegefli de astæzi ai artei de dupæ1945.5

intervenflii istorice strict definite (cum ar fi, de exemplu, activitæflile inifliate de Seth Siegelaub la New York, în1968, sau cæutærile autoritare ale ortodoxiei, care au fæcut obiectul practicilor grupului englez Art & Language).Pentru a istoriciza acum arta concept (pentru a folosi termenul aøa cum a fost næscocit, în 1961, de cætre HenryFlynt) 1 , e nevoie, aøadar, mai mult decît de-o simplæ reconstituire a figurilor celor care s-au autoproclamat actoriprincipali ai miøcærii sau de vreo supunere øcolæreascæ faflæ de puritatea intenfliilor øi operafliilor pe care au decretat-o.2 Convingerile lor au fost susflinute cu o (deja adesea hilaræ) autojustificare, prezentæ mereu de-a lungulîntregii tradiflii a pretenfliilor hipertrofiate ridicate de declarafliile avangardei secolului XX. De exemplu, una dinafirmafliile programatice ale lui Joseph Kosuth de la sfîrøitul anilor 1960 spune cæ: „Arta anterioaræ perioadeimoderne este la fel de mult artæ pe cît este omul de Neanderthal om. Din acest motiv am înlocuit peste tot,simultan, termenul «operæ» cu propoziflie artisticæ. Pentru cæ o operæ de artæ conceptualæ în sens tradiflional esteo contradicflie în termeni“. 3E esenflial sæ ne reamintim cæ opozifliile din cadrul formafliunii numite artæ conceptualæ au decurs, în parte, din diferitelelecturæri ale sculpturii minimale (øi ale echivalenflilor sæi picturali din pictura lui Mangold, Ryman øi Stella) øi din consecinflelepe care le-a dedus din aceste lecturæri generaflia de artiøti apærutæ în 1965, tot aøa cum divergenfleleau mai rezultat, de asemenea, din impactul pe care l-au avut diferifli artiøti din cadrul miøcærii minimaliste, înmæsura în care unul sau altul a fost ales de cætre noua generaflie drept figura sa centralæ de referinflæ. De exemplu,Dan Graham pare sæ fi fost implicat mai ales în opera lui Sol LeWitt. În 1965, el a organizat prima expozifliepersonalæ a lui LeWitt (ce a avut loc în galeria sa, numitæ Daniels Gallery); în 1967, a scris eseul „Two Structures:Sol LeWitt“; iar în 1969, el a notat urmætoarele în concluzia introducerii volumului sæu de scrieri, intitulat EndMoments, pe care øi l-a publicat el însuøi: „Ar trebui sæ fie evidentæ însemnætatea pe care a avut-o opera lui SolLeWitt pentru propria mea operæ. În articolul inclus aici (scris, pentru prima datæ, în 1967, rescris în 1969),sper doar ca aprecierea post factum sæ nu fi infiltrat prea mult opera sa seminalæ în categoriile mele“. 4 În schimb,Mel Bochner pare sæ-l fi ales pe Dan Flavin drept principala sa figuræ de referinflæ. El a scris unul dintre primeleeseuri despre Dan Flavin (de fapt, este un text-colaj alcætuit din citate puse laolaltæ, fiecare legate într-un fel saualtul de opera lui Flavin). 5 La scurt timp dupæ aceea, textul-colaj, ca mod de prezentare, va deveni, într-adevær,<strong>format</strong>or în cadrul activitæflilor lui Bochner, pentru cæ în acelaøi an el a organizat ceea ce a fost, probabil,prima expoziflie cu adeværat conceptualæ (atît în ce priveøte materialele expuse, cît øi în privinfla stilului de prezentare).Intitulatæ Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to Be Viewed as Art(la School of Visual Arts, în 1966), expoziflia s-a bucurat de prezenfla majoritæflii artiøtilor minimaliøti øi, totodatæ,de cea a cîtorva artiøti postminimaliøti øi conceptualiøti, care pe-atunci erau încæ necunoscufli. Strîngînd laolaltædesene, crochiuri, documente, tabele øi alte accesorii ale procesului de producflie, expoziflia s-a limitatla prezentarea „originalelor“ în fotocopii dispuse în patru folii de dosar, care au fost instalate pe socluri, în centrulspafliului expoziflional. Deøi nu ar trebui supraestimatæ importanfla unor asemenea articole (dar nici nu artrebui subestimatæ pragmatica unui asemenea stil de prezentare), intervenflia lui Bochner a inifliat în mod evidento transformare atît a <strong>format</strong>ului, cît øi a spafliului expozifliilor. Ca atare, ea indicæ faptul cæ tipul de transformarea spafliului expozifliei øi a dispozitivelor prin care este prezentatæ arta, care a fost dus pînæ la capæt doi animai tîrziu prin expozifliile øi publicafliile lui Seth Siegelaub (de exemplu, The Xerox Book), devenise deja o preocuparecomunæ a generafliei de artiøti postminimaliøti.Al treilea exemplu de strînsæ succesiune generaflionalæ ar fi faptul cæ Joseph Kosuth pare sæ-l fi ales ca figuræemblematicæ pe Donald Judd: cel puflin una din lucrærile-neon tautologice timpurii din seria Proto-Investigationsîi este dedicatæ lui Donald Judd; øi, peste tot în partea a doua a lucrærii „Art after Philosophy“ (publicatæ în noiembrie1969), numele, lucrærile øi scrierile lui Judd sînt invocate cu aceeaøi frecvenflæ ca øi cele ale lui Duchampøi Reinhardt. La sfîrøitul acestui eseu, Kosuth afirmæ explicit: „Totuøi, aø putea adæuga în grabæ la aceasta cæ amfost, cu siguranflæ, mult mai influenflat de Ad Reinhardt, Duchamp via Johns øi Morris, øi de cætre Donald Judd,decît am fost vreodatæ, într-un mod explicit, de cætre LeWitt. [...] Pollock øi Judd sînt, cred, începutul øi sfîrøitulinfluenflei americane în artæ“. 6Structures a lui Sol LeWittS-ar pærea cæ opera protoconceptualæ de la începutul anilor 1960 a lui Sol LeWitt îøi avea originea într-o înflelegerea dilemei fundamentale care a bîntuit producflia artisticæ începînd cu 1913, atunci cînd principalele sale paradigmede opoziflie au fost formulate pentru prima datæ – o dilemæ care ar putea fi descrisæ drept conflictul dintre specificitateastructuralæ øi organizarea aleatorie. Fiindcæ nevoia, pe de-o parte, atît a unei reducflii sistematice, cît øi6

arhivaa unei verificæri empirice a datelor perceptive ale unei structuri vizuale se opune dorinflei, pe de altæ parte, de-aasigna o nouæ „idee“ sau semnificaflie unui obiect ales la întîmplare (în maniera „transpozifliilor“ lui Mallarmé), caøi cum obiectul ar fi un semnificant (lingvistic) gol.Aceasta era dilema descrisæ de Roland Barthes, în 1956, drept „dificultatea vremurilor noastre“, într-unul dinparagrafele concluzive din Mitologii:S-ar pærea cæ avem de a face cu o dificultate specificæ timpului: astæzi, cel puflin pentru moment, nu maiexistæ decît o alegere posibilæ, øi aceastæ alegere nu poate fi fæcutæ decît între douæ metode, ambele la felde excesive: sæ propunem un real în întregime permeabil la istorie øi sæ ideologizæm; sau, dimpotrivæ, sæpropunem un real în cele din urmæ impenetrabil, ireductibil øi, în acest caz, sæ poetizæm. Într-un cuvînt, eunu væd deocamdatæ vreo sintezæ între ideologie øi poezie (prin poezie înfleleg, în mod foarte general, cæutareasensului inalienabil al lucrurilor). 7Cele douæ tipuri de criticæ a practicilor tradiflionale de reprezentare din contextul american postbelic au pærut,într-o primæ instanflæ, reciproc exclusive øi s-au atacat adesea cu ferocitate una pe cealaltæ. De exemplu,forma extremæ de pozitivism perceptiv autocritic a lui Reinhardt mersese prea departe pentru majoritatea artiøtilorde la Øcoala din New York øi, cu siguranflæ, pentru apologeflii modernismului american, în principal Greenbergøi Fried, care construiseræ o paradoxalæ dogmæ a transcendentalismului øi criticii autoreferenfliale. Pe de altæ parte,Reinhardt a fost la fel de zgomotos ca øi ei – dacæ nu øi mai mult – în ofensarea preopinenflilor, altfel spus, atradifliei duchampiene. Acest lucru este evident în remarcile condescendente ale lui Ad Reinhardt atît la adresalui Duchamp – „N-am aprobat øi nu mi-a plæcut niciodatæ nimic la Marcel Duchamp. Trebuie sæ alegi întreDuchamp øi Mondrian“ –, cît øi la adresa moøtenirii sale, aøa cum e ea reprezentatæ de Cage øi Rauschenberg– „Apoi, întregul melanj, øirul de poefli øi muzicieni øi scriitori amestecafli în artæ. Ræu famafli. Cage, Cunningham,Johns, Rauschenberg. Sînt împotriva amestecului tuturor artelor, împotriva amestecului artei cu viafla, øtifli, viaflacotidianæ“. 8Ceea ce s-a strecurat neobservat a fost faptul cæ aceste critici ale reprezentærii au condus ambele la rezultateperfect comparabile structural øi formal (de exemplu, seria de lucræri monocrome din 1951–1953 a luiRauschenberg øi seria de lucræri monocrome, cum e Black Quadruptych din 1955 a lui Reinhardt). Mai mult,chiar aduse dintr-o perspectivæ contraræ, argumentele critice care însofleau asemenea lucræri negau în modsistematic principiile øi funcfliile tradiflionale ale reprezentærii vizuale, construind litanii de negare surprinzætorde asemænætoare. Acest lucru este la fel de evident, de exemplu, în textul pregætit de John Cage pentru expozifliaWhite Paintings, din 1953, a lui Rauschenberg, ca øi în manifestul „Art as Art“, din 1962, al lui Ad Reinhardt.Întîi Cage:Cui i se adreseazæ, Niciun subiect, Nicio imagine, Niciun gust, Niciun obiect, Nicio frumusefle, Niciun talent,Nicio tehnicæ (niciun de ce), Nicio idee, Nicio intenflie, Nicio artæ, Nicio simflire, Niciun negru, Niciunalb niciun (øi). Dupæ o atentæ apreciere, am ajuns la concluzia cæ nu existæ nimic în aceste picturi care sæ nupoatæ fi schimbat, cæ ele pot fi privite în orice luminæ øi cæ nu sînt distruse de acfliunea umbrelor. Aleluia!Orbul poate iaræøi vedea; apa e bunæ. 9Øi apoi manifestul lui Ad Reinhardt pentru propriul sæu principiu „Art as Art“:Nici linii sau fantezii, nici forme sau compoziflii sau reprezentæri, nici viziuni sau senzaflii sau impulsuri, nicisimboluri sau semne sau impastouri, nici ornamente sau coloræri sau desene, nici plæceri sau dureri, niciaccidente sau readymade-uri, nici lucruri, nici idei, nici relaflii, nici atribute, nici calitæfli – nimic din ce nu aparflineesenflei. 10Formalismul american empirist al lui Ad Reinhardt (condensat în formula sa „Arta ca Artæ“) øi critica vizualitæfliia lui Duchamp (exprimatæ, de exemplu, în faimoasa butadæ: „Toatæ opera mea din perioada de dinainte deNud era picturæ vizualæ. Apoi am ajuns la idee. [...]“ 11 ) apar în fuziunea – destul de improbabilæ din punct devedere istoric – realizatæ de încercarea lui Kosuth de a integra cele douæ poziflii, pe la mijlocul anilor 1960, tentativæcare a condus la formula sa, „Arta ca Idee ca Idee“, pe care a utilizat-o începînd cu 1966. Totuøi, ar trebui7

fost, desigur, prefigurat, de asemenea, de practica lui Duchamp. În 1944, el a angajat un notar pentru a legalizao declaraflie de autenticitate în privinfla lucrærii sale din 1919 L.H.O.O.Q.: „[...] pentru a certifica faptul cæ acestaeste «readymade-ul» original L.H.O.O.Q., Paris 1919“. Ceea ce era probabil încæ o manevræ pragmaticæ alui Duchamp (deøi, cu siguranflæ, una din seria celor care-i provocau plæcerea de-a observa estomparea temeiurilorprin care se legitima definiflia operei de artæ doar ca abilitate manualæ øi competenflæ vizualæ) urma sæ devinæcurînd una din træsæturile constitutive ale dezvoltærilor ulterioare ale artei conceptuale. Influenflînd, cu siguranflæ,certificatele eliberate de Piero Manzoni (1960–1961), ce defineau persoane sau pærfli ale persoanelor ca operede artæ, pe o duratæ limitatæ ori pe durata întregii viefli, putem regæsi, în acelaøi timp, aceeaøi træsæturæ øi în certificatelelui Yves Klein, care alocau zone de sensibilitate pictorialæ imaterialæ diferiflilor colecflionari care le achiziflionau.Dar aceastæ esteticæ a convenfliilor lingvistice øi a contractelor juridice nu se limiteazæ la negarea validitæflii atelieruluiestetic tradiflional, ci anuleazæ øi estetica producfliei øi a consumului, care mai guvernau încæ arta pop øiminimalismul.Tot aøa cum critica modernistæ (øi prohibiflia ultimæ) a reprezentærii figurative devenise, în prima decadæ a secoluluiXX, legea – cu un rol dogmatic crescînd – a producfliei picturale, øi arta conceptualæ instaurase acum, caregulæ esteticæ indepasabilæ a sfîrøitului de secol XX, interdicflia oricærei vizibilitæfli. Aøa cum readymade-ul negasenu doar reprezentarea figurativæ, autenticitatea øi auctorialitatea, odatæ cu introducerea repetifliilor øi a seriilor(de exemplu, legea producfliei industriale) pentru a înlocui estetica de atelier a originalului artizanal, arta conceptualæajunge sæ disloce chiar øi acea imagine a obiectului produs în serie øi a formelor sale estetizate din artapop, înlocuind o esteticæ a producfliei øi consumului industrial cu o esteticæ a organizærii administrative øi juridiceøi a validærii instituflionale.Cærflile lui Edward RuschaUn exemplu important al acestor tendinfle – recunoscut atît de Dan Graham ca principalæ sursæ de inspirafliepentru lucrarea sa „Homes for America“, cît øi de Kosuth, a cærui „Art after Philosophy“ îl recomandæ ca artistprotoconceptualist – este lucrarea timpurie sub formæ de carte a lui Edward Ruscha. Printre strategiile-cheieale viitoarei arte conceptuale inifliate de Ruscha în 1963 se numærau urmætoarele: alegerea vernacularului (deexemplu, arhitectura) ca referent; folosirea sistematicæ a fotografiei ca mediu de reprezentare; øi dezvoltareaunei noi forme de distribuflie (de exemplu, cærflile de producflie comercialæ în opoziflie cu livre d’artiste, de obiceimanufacturate).În mod caracteristic, referinfla la arhitecturæ, indiferent în ce formæ, ar fi fost de negîndit în contextul formalismuluide tip american øi al expresionismului abstract (sau, nu mai puflin, în cadrul esteticii europene postbelice),pînæ la începutul anilor 1960. Devotamentul faflæ de o esteticæ privatæ a experienflei contemplative, culipsa ei concomitentæ de orice reflecflie sistematicæ asupra funcfliilor sociale ale producfliei artistice øi asupra publiculuilor real øi potenflial, a împiedicat, de fapt, orice explorare a interdependenflei producfliei arhitecturale øiartistice, fie chiar øi în formele cele mai superficiale øi comune ale decorului arhitectural. 16 S-a întîmplat doarodatæ cu apariflia artei pop, la începutul anilor 1960, în special în lucrærile lui Bernd øi Hilla Becher, Claes Oldenburgøi Edward Ruscha, ca referinflele la sculptura monumentalæ (chiar øi prin negarea sa, bunæoaræ lucrareaAnti-Monument) øi la arhitectura vernacularæ sæ reintroducæ (chiar øi numai indirect) o reflecflie asupra spafliului(arhitectural øi domestic) public, aducînd astfel în prim-plan absenfla unei reflecflii artistice dezvoltate asupra problematiciicontemporane a caracterului public.În ianuarie 1963 (anul primei expoziflii retrospective Duchamp din America, desfæøuratæ la Pasadena ArtMuseum), Ruscha, un artist relativ necunoscut din Los Angeles, a decis sæ publice o carte intitulatæ Twenty-SixGasoline Stations. Pe cît de mult a fost cartea, modestæ ca <strong>format</strong> øi producflie, de îndepærtatæ de tradiflia cærflilorde artiøti, pe atît de mult se opunea iconografia sa fiecærui aspect al artei americane oficiale din anii 1950 øi de laînceputul anilor 1960: moøtenirea expresionismului abstract øi a picturii de cîmp cromatic [Color Field painting].Totuøi, cartea nu era atît de stræinæ de reflecflia artisticæ a generafliei nou-apærute, dacæ ne amintim cæ, în urmæcu un an, un artist necunoscut din New York, pe nume Andy Warhol, expusese la Ferus Gallery un aranjamentîn serie de douæzeci øi douæ de serigrafii, înfæfliøînd cutii de conserve Campbell Soup, aranjate ca niøteobiecte pe raft. Cu toate cæ atît Warhol, cît øi Ruscha au acceptat un concept al experienflei publice inerent,færæ putinflæ de scæpare, condifliilor de consum, ambii artiøti au modificat modul de producflie, precum øi formade distribuflie a operei lor, astfel încît un alt fel de public era, eventual, vizat.10

arhivaIconografia vernacularæ a lui Ruscha s-a dezvoltat, în aceeaøi mæsuræ în care o fæcuse øi cea a lui Warhol, plecîndde la moøtenirea lui Duchamp øi Cage a unei estetici a „indiferenflei“ øi de la angajamentul faflæ de o organizareantiierarhicæ a unei facticitæfli universal valide, operînd ca afirmaflie totalæ. Într-adevær, selecflia la întîmplareøi alegerea aleatorie dintr-un numær infinit de obiecte posibile (Twenty-Six Gasoline Stations a lui Ruscha, ThirteenMost Wanted Men a lui Warhol) urmau curînd sæ devinæ strategii esenfliale ale esteticii artei conceptuale:sæ ne gîndim la The Thousand Longest Rivers a lui Alighiero Boetti, la One Billion Dots a lui Robert Barry, la OneMillion Years a lui On Kawara sau, mai semnificativ în acest context, la proiectul pe viaflæ al lui Doug Huebler,intitulat Variable Piece: 70. Aceastæ lucrare susfline cæ documenteazæ în manieræ fotograficæ „existenfla tuturorpersoanelor în viaflæ, pentru a produce cea mai autenticæ øi mai cuprinzætoare reprezentare a întregii speciiumane, în mæsura în care poate fi ordonatæ în aceastæ manieræ. Ediflii ale acestei lucræri vor fi publicate periodic,într-o varietate de moduri tematice: «100.000 de persoane», «1.000.000 de persoane», «10.000.000de persoane» [...] etc.“ Sau, iaræøi, existæ lucræri de Stanley Brouwn sau Hanne Darboven în care, de fiecaredatæ, un principiu arbitrar, abstract, de puræ cuantificare înlocuieøte principiile tradiflionale ale organizærii picturalesau sculpturale øi/sau ordinea relaflionalæ compoziflionalæ.Aøa cum cærflile lui Ruscha au deplasat organizarea formalæ a reprezentærii, modul de prezentare însuøi s-a trans<strong>format</strong>øi el: în loc sæ detaøeze imagistica fotograficæ (sau tipæritæ) din sursele culturii de masæ øi sæ transformeaceste imagini în picturæ (aøa cum au practicat-o Warhol øi artiøtii pop), Ruscha expunea acum direct fotografia,într-un mediu pictural adecvat. Øi rezultatul a fost un tip de fotografie cît se poate de laconic, unul care se situaexplicit în afara convenfliilor artei fotografice øi, în aceeaøi mæsuræ, în afara celor ale venerabilei tradiflii a fotografieidocumentare, mai puflin în afara tradifliilor fotografiei „angajate“ [„concerned“ photography]. Aceastæ loialitatefaflæ de o abordare inexpresivæ, anonimæ, amatoristicæ a formei fotografice corespunde exact opfliunii iconograficea lui Ruscha pentru banalul arhitectural. Astfel încît, la toate cele trei niveluri – iconografie, formæ reprezentaflionalæ,mod de distribuflie –, formele date ale obiectului artistic nu mai apæreau ca acceptabile atîta timpcît se situau pe pozifliile lor specializate øi privilegiate prin tradiflie. Aøa cum spunea retrospectiv Victor Burgin:„Unul din lucrurile la care næzuia arta conceptualæ era demontarea ierarhiei mediatice, conform cæreia pictura(sculptura urmînd-o îndeaproape) e consideratæ inerent superioaræ – iatæ lucrul cel mai uimitor! – fotografiei“. 17Prin urmare, chiar în anii 1965–1966, în timpul stadiilor timpurii ale practicilor conceptuale, asistæm la aparifliaunor abordæri diametral opuse: Proto-Investigations ale lui Kosuth, pe de o parte (conform autorului, conceputeøi produse în 1965); 18 øi, pe de alta, o lucrare cum e „Homes for America“ a lui Dan Graham. Publicatæîn Arts Magazine în decembrie 1966, ultima dintre ele este o lucrare – necunoscutæ celor mai mulfli øi multævreme nerecunoscutæ – ce accentueazæ în mod programatic contingenfla øi contextualitatea structuralæ, formulîndîntrebæri esenfliale despre prezentare øi distribuflie, despre public øi auctorialitate. În acelaøi timp, lucrarealega estetica minimalistæ ezotericæ øi autoreflexivæ a permutærii de o perspectivæ asupra arhitecturii culturiide masæ (redefinind, prin aceasta, moøtenirea artei pop). Detaøarea minimaliøtilor de orice reprezentare a experienfleisociale contemporane, asupra cæreia a insistat arta pop, chiar dacæ furtiv, a provenit din încercarea lorde a construi modele de semnificaflie øi experienflæ vizualæ care juxtapuneau reducflia formalæ cu un model structuraløi fenomenologic de percepflie.Dimpotrivæ, opera lui Graham pleda pentru o analizæ a semnificafliei (vizuale), care defineøte semnele atît cafiind constituite structural în interiorul relafliilor din sistemul limbajului, cît øi ca avîndu-øi fundamentul în referentulexperienflei sociale øi politice. În plus, concepflia dialecticæ a lui Graham despre reprezentarea vizualæ demolaîntr-o manieræ polemicæ diferenfla dintre spafliile de producflie øi cele de reproducere (ceea ce urma sæ numeascæSeth Siegelaub, în 1969, informaflii primare øi secundare). 19 Anticipînd modurile curente de distribuflie øi dereceptare ale operei din interiorul înseøi structurii sale de producflie, „Homes for America“ a eliminat diferenfladintre constructul artistic øi reproducerea sa (fotograficæ), diferenfla dintre o expoziflie de obiecte de artæ øi imagineafotograficæ a instalærii sale, diferenfla dintre spafliul arhitectural al galeriei øi spafliul catalogului øi al revistei deartæ.Tautologiile lui Joseph KosuthSituîndu-se pe o poziflie contraræ, Kosuth susflinea, în 1969, tocmai continuitatea øi expansiunea moøtenirii pozitivistea modernismului, folosindu-se de ceea ce, la acea vreme, i se pæreau a fi, probabil, cele mai radicale øimai evoluate instrumente ale acelei tradiflii: pozitivismul logic al lui Wittgensten øi filosofia limbajului (el a afirmatinsistent aceastæ continuitate atunci cînd declara, în prima parte din „Art after Philosophy“: „Filosofia11

limbajului poate fi consideratæ cu certitudine moøtenitoarea empirismului [...]“). Astfel, chiar atunci cîndpretindea cæ dislocæ formalismul lui Greenberg øi Fried, el actualiza, de fapt, proiectul modernist al autoreflexivitæflii.Fiindcæ Kosuth a fixat nofliunea de artæ dezinteresatæ øi autosuficientæ supunînd atît modelul wittgensteinian aljocurilor de limbaj, cît øi modelul duchampian al readymade-ului regulilor unui model al semnificafliei care opereazæîn tradiflia modernistæ a acelui paradox pe care Michel Foucault l-a numit gîndire „empirico-transcendentalæ“ amodernitæflii. Altfel spus, producflia artisticæ mai e încæ, pentru Kosuth, în 1969, rezultatul unei intenflii artisticecare se constituie, mai presus de toate, în autoreflecflie (chiar dacæ acum e mai mult discursivæ decît perceptivæ,mai mult epistemologicæ decît esenflialistæ). 20În chiar momentul în care formafliunile complementare ale minimalismului øi ale artei pop au reuøit, pentruprima datæ, sæ critice moøtenirea formalismului de tip american øi prohibifliile sale în privinfla referenflialitæflii, acestproiect este cu atît mai surprinzætor. Privilegierea axei literale în dauna axei referenfliale a limbajului (vizual) –aøa cum o læsase moøtenire estetica formalistæ a lui Greenberg – fusese contratæ în arta pop printr-o consacrareprovocatoare faflæ de iconografia culturii de masæ. Apoi, atît minimalismul, cît øi arta pop au subliniat permanentprezenfla universalæ a mijloacelor de reproducere industrialæ ca un cadru indepasabil ce condiflioneazæmijloacele artistice de producflie sau, altfel spus, au subliniat faptul cæ estetica de atelier fusese înlocuitæ ireversibilde o esteticæ a producfliei øi a consumului. Øi, în sfîrøit, minimalismul øi arta pop au dezgropat istoria reprimatæa lui Duchamp (øi a dadaismului în sens larg), fenomen tot atît de greu de acceptat pentru gîndirea esteticædominantæ de la sfîrøitul anilor 1950 øi începutul anilor ’60. Lectura îngustæ pe care o opereazæ Kosuth asuprareadymade-ului e surprinzætoare pentru încæ un motiv. În 1969, el susflinea explicit cæ intrase pentru primadatæ în contact cu opera lui Duchamp mai curînd prin intermediul lui Johns øi Morris decît printr-un studiu efectival scrierilor øi lucrærilor lui Duchamp.Aøa cum am væzut, primele douæ faze ale receptærii lui Duchamp de cætre artiøtii americani de la începutul anilor1950 (Johns øi Rauschenberg) pînæ la Warhol øi Morris, la începutul anilor 1960, au inaugurat, treptat, o întreagæserie de implicaflii ale readymade-urilor lui Duchamp. 21 De aceea, e cu atît mai deconcertant sæ observi cæ,dupæ 1968 – ceea ce s-ar putea numi începutul celei de-a treia faze a receptærii lui Duchamp –, înflelegereaacestui model de cætre artiøtii conceptualiøti încæ mai aduce în prim-plan declaraflia de intenflie în dauna contextualizærii.Acest lucru ræmîne adeværat nu doar în cazul lucrærii „Art after Philosophy“ a lui Kosuth, ci, în aceeaøimæsuræ, pentru grupul britanic Art & Language, care scria, în introducerea primului numær al revistei, în mai1969:Sæ plasæm un obiect într-un context în care atenflia oricærui spectator sæ fie drenatæ spre expectanfla de-arecunoaøte obiecte de artæ. De exemplu, plasînd ceea ce fusese pînæ atunci un obiect cu caracteristici vizualediferite de cele aøteptate în contextul unei ambianfle artistice sau proclamînd, în calitate de artist, obiectuldrept un obiect de artæ, indiferent dacæ a fost sau nu într-o ambianflæ artisticæ. Prin folosirea acestor tehnici,ceea ce pæreau a fi morfologii cu totul øi cu totul noi continuau sæ reclame statutul de membri ai clasei„obiecte de artæ“.De exemplu, „readymade-urile“ lui Duchamp øi „Portrait of Iris Clert“ de Rauschenberg. 22Cîteva luni mai tîrziu, Kosuth îøi întemeia argumentul în favoarea dezvoltærii artei conceptuale exact pe o astfelde lecturæ restrictivæ a lui Duchamp. Fiindcæ, prin viziunea sa limitatæ asupra istoriei øi tipologiei operei luiDuchamp, argumentul lui Kosuth – asemeni celui al grupului Art & Language – se concentreazæ exclusiv asupra„readymade-urilor brute“. Prin aceasta, teoria conceptualistæ timpurie nu doar cæ lasæ pe dinafaræ opera picturalæa lui Duchamp, ci, în plus, mai øi ignoræ lucræri cu adeværat fundamentale ca Three Standard Stoppages(1913), ca sæ nu mai pomenim de Marea sticlæ (1915–1923) sau de Etant données [Date fiind] (1946–1966),sau Boîte en valise [Cutie-valizæ], realizatæ în 1935–1941. Însæ ceea ce e øi mai grav e cæ lectura readymadeurilorbrute este, în ea însæøi, extrem de îngustæ, reducînd, de fapt, pur øi simplu, modelul readymade-ului lacel al propozifliei analitice. În mod caracteristic, atît Art & Language, cît øi „Art after Philosophy“ a lui Kosuth sereferæ la celebrul exemplu din estetica actelor de vorbire a lui Robert Rauschenberg („Acesta este un portretal lui Iris Clert, dacæ o spun eu“), bazatæ pe o înflelegere mai curînd limitatæ a readymade-ului, ca act al uneideclaraflii artistice voluntare. Aceastæ înflelegere, tipicæ pentru începutul anilor 1950, e preluatæ de faimoasa normælapidaræ a lui Judd (o afirmaflie lipsitæ, evident, de sens), citatæ ceva mai încolo în textul lui Kosuth: „dacæ cinevaspune cæ-i artæ, atunci e artæ. [...]“.12

arhivaÎn 1969, Art & Language øi Kosuth aveau în comun punerea „propozifliei analitice“, intrinsecæ oricærui readymade– adicæ afirmaflia „aceasta e o operæ de artæ“ –, mai presus de toate celelalte aspecte presupuse de modelulreadymade-ului (logica sa structuralæ, træsæturile sale în calitate de obiect de folosire øi de consum produscu mijloace industriale, serialitatea sa øi dependenfla semnificafliei sale de context). Øi, lucrul cel mai important,dupæ Kosuth, aceasta înseamnæ cæ propozifliile artistice se constituie în negarea oricærei referenflialitæfli, fie eacea a contextului istoric al semnului (artistic), fie cea a funcfliei øi utilizærii sale sociale:Operele de artæ sînt propoziflii analitice. Adicæ, privite în contextul-lor-ca-artæ, ele nu furnizeazæ niciun felde informaflie despre nicio stare de fapt. O operæ de artæ este o tautologie prin faptul cæ e o prezentarea intenfliei artistului, adicæ el spune cæ acea operæ de artæ anume este artæ, ceea ce înseamnæ cæ e o definifliea artei. Astfel, ceea ce e artæ e veritabil a priori (ceea ce vrea sæ spunæ Judd atunci cînd afirmæ cæ „dacæ cinevaspune cæ-i artæ, atunci e artæ“). 23Sau, ceva mai tîrziu, în acelaøi an, scria în „The Sixth Investigation 1969 Proposition 14“ (un text care a dispærutîn mod misterios din ediflia scrierilor sale):Dacæ vom considera formele pe care le ia arta ca fiind limbajul artei, ne putem da seama cæ o operæ deartæ e un fel de propoziflie prezentæ în contextul artei ca un comentariu la artæ. O analizæ a tipurilor de propoziflieînfæfliøeazæ „operele“ de artæ ca propoziflii analitice. Operele de artæ care încearcæ sæ ne spunæ cevadespre lume sînt condamnate sæ eøueze. [...] Tocmai absenfla de realitate în artæ este realitatea artei. 24Eforturile programatice ale lui Kosuth de a reinstaura o normæ a autoreflexivitæflii discursive în maniera uneicritici a autoreflexivitæflii vizuale øi formale a lui Greenberg øi a lui Fried sînt cu atît mai surprinzætoare, fiindcæo parte considerabilæ din „Art after Philosophy“ e dedicatæ elaboratei construcflii a unei genealogii a artei conceptuale,în øi prin sine un proiect istoric (de exemplu, „Orice artæ [dupæ Duchamp] e conceptualæ [prin naturaei], pentru cæ arta existæ doar într-o manieræ conceptualæ“). Însæøi aceastæ construcflie a unei filiafliicontextualizeazæ øi istoricizeazæ deja, desigur, prin faptul cæ „ne spune ceva despre lume“ – despre lumea artei,cel puflin; adicæ opereazæ, færæ sæ vrea, ca o propoziflie sinteticæ (chiar dacæ doar în cadrul convenfliilor unui sistemlingvistic particular) øi neagæ, astfel, atît puritatea, cît øi posibilitatea unei producflii artistice autonome caresæ funcflioneze, în interiorul propriului sistem lingvistic al artei, ca o simplæ propoziflie analiticæ.Poate cæ unii vor încerca sæ susflinæ cæ, de fapt, cultul reînnoit al tautologiei pe care îl instituie Kosuth împlineøteproiectul simbolist. S-ar putea spune, de exemplu, cæ aceastæ reînnoire e urmarea logicæ a preocupærii exclusivea simbolismului pentru condifliile øi teoretizærile modurilor de concepere øi lecturare a artei. Un astfel deargument tot n-ar putea împiedica totuøi apariflia unor întrebæri privind cadrul istoric diferit în care un astfel decult trebuie sæ-øi gæseascæ propria determinare. Încæ de la originile sale simboliste, teologia modernistæ a arteifusese dominatæ de o opoziflie polarizantæ. Fiindcæ o venerare religioasæ a formei plastice autoreferenfliale capuræ negaflie a gîndirii raflionaliste øi empiriste poate fi lecturatæ, în acelaøi timp, ca fiind nimic altceva decît înscriereaøi instrumentalizarea acelei ordini anume – chiar øi, sau mai ales, în negaflia sa – în domeniul esteticii înseøi(aplicarea aproape imediatæ øi universalæ a simbolismului la cosmosul producfliei de mærfuri din secolul alXIX-lea e o bunæ dovadæ pentru aceasta).Aceastæ dialecticæ a ajuns sæ-øi cearæ drepturile istorice cu atît mai ræspicat în contextul contemporan postbelic.Pentru cæ, în condifliile unei fuziuni tot mai accelerate a industriei culturale cu ultimele bastioane ale uneisfere autonome a artei înalte, autoreflexivitatea a început tot mai mult (øi inevitabil) sæ se deplaseze de-a lungulgraniflei dintre pozitivismul logic øi campaniile publicitare. Mai departe, drepturile øi rafliunea de a fi ale uneiclase de mijloc postbelice recent consacrate, care øi-a atins deplina maturitate în anii 1960, øi-ar putea asumaidentitatea esteticæ în chiar modelul tautologiei øi în estetica administrafliei care-o însoflesc. Fiindcæ aceastæ identitateesteticæ e structuratæ, în mare mæsuræ, dupæ modelul identitæflii sociale a clasei, cu alte cuvinte, ca unace se ocupæ doar cu administrarea muncii øi producfliei (în loc sæ producæ propriu-zis) øi cu distribuirea mærfurilor.Ajungînd sæ fie stabil instalatæ pe poziflia celei mai obiønuite øi mai puternice clase sociale din societateapostbelicæ, aceastæ clasæ e cea care, dupæ cum scria H. G. Helms în cartea sa despre Max Stirner, „se priveazævoluntar de drepturile de intervenflie în procesul politic decizional, pentru a se adapta mai eficient la condifliilepolitice existente“. 2513

Aceastæ esteticæ a nou-instituitei puteri a administrærii îøi descoperæ prima voce literaræ pe deplin articulatæ într-unfenomen ca le nouveau roman al lui Robbe-Grillet. N-a fost întîmplætor faptul cæ un proiect literar atît deprofund pozitivist avea sæ serveascæ apoi, în America, ca un punct de plecare pentru arta conceptualæ. Însæ,paradoxal, s-a întîmplat în exact acelaøi moment istoric ca funcfliile sociale ale principiului tautologic sæ-øidescopere cea mai lucidæ analizæ într-o examinare criticæ lansatæ în Franfla.În primele scrieri ale lui Roland Barthes gæsim, concomitent cu le nouveau roman, o discuflie despre tautologic:Tautologia. Da, øtiu, cuvîntul nu este frumos. Dar øi lucrul este foarte urît. Tautologia este acel procedeuverbal care constæ în definirea aceluiaøi prin acelaøi („Teatrul este teatru“). [...] ne refugiem în tautologie caîn fricæ, sau în furie, sau în tristefle, cînd nu avem nicio explicaflie. [...] În tautologie existæ o dublæ ucidere:este ucis raflionalul fiindcæ væ rezistæ; este ucis limbajul fiindcæ væ trædeazæ. [...] Tautologia atestæ o profundæneîncredere faflæ de limbaj: îl respingefli fiindcæ væ lipseøte. Însæ orice respingere a limbii este øi o moarte.Tautologia întemeiazæ o lume moartæ, o lume imobilæ. 26Zece ani mai tîrziu, exact atunci cînd Kosuth îl descoperea ca proiect estetic central al epocii sale, fenomenultautologicului a fost deschis din nou examinærii în Franfla. Însæ de astæ datæ, în loc sæ fie discutat ca formæ lingvisticæøi retoricæ, a fost analizat ca efect social general: atît ca reflex comportamental de nedepæøit, cît øi, odatæce exigenflele industriei culturale avansate (adicæ publicitatea øi mass-media) au fost instaurate sub forma culturiispectacolului, ca o condiflie universalæ a experienflei. Ceea ce, desigur, ræmîne deschis discufliilor e mæsuraîn care arta conceptualæ de un anumit tip a împærtæøit aceste condiflii sau chiar le-a promulgat øi le-a implementatîn sfera esteticului – ceea ce ar explica astfel, probabil, prezenfla øi succesul sæu ulterior într-o lume a strategiilorpublicitare – sau, ca alternativæ, mæsura în care s-a înscris doar într-o logicæ inevitabilæ a unei lumiadministrate în întregime, aøa cum o definea termenul celebru al lui Adorno. Astfel scria Guy Debord în 1967:Caracterul fundamental tautologic al spectacolului decurge din simplul fapt cæ mijloacele sale sînt în acelaøitimp scopul sæu. În imperiul pasivitæflii moderne, el este soarele care nu apune niciodatæ. El acoperætoatæ suprafafla pæmîntului, scældîndu-se la nesfîrøit în propria-i glorie. 27O poveste cu multe pætrateFormele vizuale care corespund în cel mai înalt grad formei lingvistice a tautologiei sînt pætratul øi rotaflia sa stereometricæ,cubul. Nu e deci surprinzætor cæ aceste douæ forme au fost cît se poate de ræspîndite în producfliapicturalæ øi sculpturalæ de la începutul øi mijlocul deceniului øapte. Acesta a fost momentul în care o riguroasæautoreflexivitate s-a orientat spre examinarea limitelor tradiflionale ale obiectelor sculpturale moderniste, totaøa cum o reflecflie fenomenologicæ asupra spafliului vizualitæflii insista asupra reîncorporærii parametrilor arhitecturaliîn conceperea picturii øi a sculpturii.Atît de profund au pætruns pætratul øi cubul în vocabularul sculpturii minimaliste, încît, în 1967, Lucy Lipparda publicat un chestionar care examina rolul acestor forme, øi pe care îl fæcuse sæ circule printre numeroøi artiøti.În ræspunsul sæu la chestionar, Donald Judd, într-una din multiplele sale tentative de-a degaja morfologia minimalismuluipornind de la cercetæri similare asupra avangardei istorice din prima parte a secolului XX, a înfæfliøatdimensiunea agresivæ a gîndirii tautologice (deghizatæ în pragmatism, aøa cum se întîmpla, în general, în cazulsæu), contestînd, pur øi simplu, cæ vreo semnificaflie istoricæ ar putea fi inerentæ formelor geometrice sau stereometrice:Nu cred cæ e nimic special la pætrate, pe care nu le utilizez, sau la cuburi. Nu au, cu siguranflæ, nicio semnificaflieintrinsecæ sau vreo superioritate oarecare. Øi totuøi, e ceva: cuburile sînt mult mai uøor de fæcut decît sferele.Calitatea principalæ a formelor geometrice e cæ nu sînt organice, aøa cum e, altminteri, orice artæ. Oformæ care sæ nu fie nici geometricæ, nici organicæ ar fi o mare descoperire. 28Ca formæ centralæ a autoreflexivitæflii vizuale, pætratul desfiinfleazæ parametrii spafliali tradiflionali ai verticalitæflii øiorizontalitæflii, anulînd, astfel, metafizica spafliului øi convenfliile sale de lecturare. Tocmai în acest mod (începîndcu Pætratul negru al lui Malevici, din 1915), pætratul se indicæ færæ încetare pe sine: ca perimetru spaflial, ca plan,ca suprafaflæ øi, simultan, ca suport. Însæ, prin însuøi succesul acestui gest autoreferenflial, determinînd forma14

arhivaca fiind pur pictorialæ, pictura pætratæ asumæ – paradoxal, dar inevitabil – caracterul de relief/obiect situat în spafliureal. Prin aceasta, ea invitæ la o privire/lecturare a contingenflei spafliale øi a inserærii arhitecturale, insistînd asupraiminentei øi ireversibilei tranziflii de la picturæ la sculpturæ.Aceastæ tranziflie s-a efectuat în cadrul artei protoconceptuale de la începutul øi mijlocul anilor 1960 printr-unnumær relativ limitat de operaflii pictoriale specifice. A fost realizatæ, în primul rînd, prin accentuarea opacitæfliipicturii. Statutul de obiect al structurii picturale putea fi subliniat unificîndu-i øi omogenizîndu-i suprafafla prinmonocromie, texturæ serializatæ øi structuræ compoziflionalæ cadrilatæ; sau putea fi scos în evidenflæ obturînd literalmentetransparenfla spaflialæ a unei picturi, prin simpla modificare a suportului sæu material: transpunîndu-lde pe pînzæ pe o flesæturæ nefixatæ pe øasiu sau pe metal. Acest tip de investigare a fost dezvoltat sistematic înpicturile protoconceptuale ale lui Robert Ryman, de pildæ, care a folosit fiecare din aceste posibilitæfli separatsau în diferite combinaflii, de la începutul pînæ la mijlocul anilor 1960; sau, dupæ 1965, în picturile lui RobertBarry, Daniel Buren øi Niele Toroni.În al doilea rînd – printr-o contramiøcare øi inversiune directæ a primeia –, statutul de obiect putea fi atins accentuînd,într-o manieræ literalæ, transparenfla picturii. Acest lucru implica instituirea unei dialectici între suprafaflapicturalæ, cadru øi suport arhitectural, fie printr-o deschidere literalæ a suportului pictural, ca în primele Structuresale lui Sol LeWitt, fie prin inserflia unor suprafefle transparente sau translucide în cadrul convenflional alprivirii, ca în picturile de fibre de sticlæ ale lui Ryman, în primele picturi de nailon ale lui Buren sau în panourilede sticlæ încadrate în metal ale lui Michael Asher øi Gerhard Richter, ambele realizate între 1965 øi 1967. Sauca în opera timpurie a lui Robert Barry (cum ar fi lucrarea sa Painting in Four Parts din 1967, din Colecflia FER),unde obiectele pætrate, monocrome de pînzæ pæreau sæ-øi asume acum rolul unei simple demarcaflii arhitecturale.Funcflionînd ca obiecte picturale descentrate, ele delimiteazæ spafliul arhitectural exterior într-o manieræanalogæ compozifliilor seriale sau centrale din primele lucræri minimaliste, care încæ mai defineau spafliul sculpturalsau pictural intern. Ori ca în pînza pætratæ a lui Barry (1967), care trebuie plasatæ exact la mijlocul pereteluice are o funcflie arhitecturalæ de sprijin, øi în care lucrarea e conceputæ astfel încît sæ deplaseze lectura sade la un obiect pictural centrat, unificat, înspre o experienflæ a contingenflei arhitecturale, încorporînd astfel strategiilesuplimentare øi supradeterminante ale plasærii curatoriale øi ale convenfliilor instalafliei (dezavuate, de obicei,în picturæ øi sculpturæ) în concepflia lucrærii înseøi.Iar în al treilea rînd – øi cel mai adesea –, aceastæ tranziflie e efectuatæ prin „simpla“ rotaflie a pætratului, aøa cumera evident, de la început, în celebra diagramæ din 1937 a lui Naum Gabo, unde un cub volumetric se suprapuneunuia stereometric, cu scopul de a face vizibilæ continuitatea inerentæ dintre formele planare stereometriceøi cele volumetrice. Aceastæ rotaflie a generat structuri cubice de-o diversitate manifestæ în lucræri precumCondensation Cube (1963–1965) a lui Hans Haacke, Four Mirrored Cubes (1965) a lui Robert Morris sau MineralCoated Glass Cubes a lui Larry Bell øi Wall-Flour Piece (Three Squares) a lui Sol LeWitt, lucræri produse simultan,în 1966. Toate acestea (dincolo de împærtæøirea unei evidente morfologii a cubului) s-au angajat într-o dialecticæa opacitæflii øi transparenflei (sau în sinteza acestei dialectici în reflectarea în oglindæ, aøa cum se întîmpla în MirroredCubes a lui Morris sau în variafliile estetizate ale temei executate de Larry Bell). Odatæ angajate în dialecticasuprafeflei øi a cadrului øi în aceea a obiectului øi a recipientului arhitectural, ele au dislocat raporturile tradiflionaledintre figuræ øi fond.Desfæøurarea unora sau a tuturor acestor strategii (sau, în majoritatea cazurilor, a diferitelor lor combinaflii) încontextul artei minimaliste øi postminimaliste, adicæ pictura øi sculptura protoconceptualæ, a avut ca rezultat oserie de obiecte hibride. Acestea nu mai corespundeau niciuneia din categoriile tradiflionale de atelier øi nicinu mai puteau fi identificate ca decoraflii arhitecturale sau în relief – aceøtia fiind termenii de compromis folosiflide obicei pentru a crea o punte între aceste categorii. Astfel, aceste obiecte demarcau un alt spectru al reorientæriiînspre arta conceptualæ. Ele nu se limitau doar la a destabiliza graniflele categoriilor artistice tradiflionale aleproducfliei de atelier, erodîndu-le prin utilizarea unor moduri de producflie industrialæ, aøa cum proceda minimalismul,ci au mers mai departe în revizuirea criticæ a discursului atelierului, ca termen cæruia i se opune discursulproducfliei/consumului. Demontîndu-le pe ambele, finalmente, odatæ cu inerentele lor convenflii alevizualitæflii, ele au instituit o esteticæ a administrærii.La prima vedere, diversitatea acestor obiecte protoconceptuale ar putea sugera cæ manierele lor estetice efectivede operare diferæ atît de profund, încît o lecturæ comparativæ care sæ opereze doar cu organizærile lor formaleøi morfologice aparent analoge – toposul vizual øi pætratul – ar fi ilegitimæ. De exemplu, istoria artei a excluschiar din acest motiv Condensation Cube a lui Haacke de la orice afiliere la minimalism. Cu toate acestea, tofli15

16aceøti artiøti definesc, pe la mijlocul anilor 1960, producflia øi receptarea artisticæ într-un fel care trece dincolode pragul tradiflional al vizualitæflii (atît în termeni de materiale sau de proceduri de producflie specifice atelierului,cît øi în termeni de producflie industrialæ), øi tocmai în virtutea acestei paralele poate fi înfleles faptul cæ lucrærilelor se aflæ într-o strînsæ conexiune, dincolo de o simplæ analogie structuralæ sau morfologicæ. Lucrærile protoconceptualede la mijlocul anilor 1960 redefinesc, într-adevær, experienfla esteticæ ca multiplicitate de modurinespecializate ale experienflei obiectului øi a limbajului. În funcflie de lectura pe care o provoacæ aceste obiecte,experienfla esteticæ – drept o investire individualæ øi socialæ a obiectelor cu semnificaflie – se constituie prin convenfliilingvistice øi, nu mai puflin, prin convenflii speculare, prin determinarea instituflionalæ a statutului obiectuluila fel de mult ca prin capacitatea de-a lectura a spectatorului.În cadrul acestei concepflii împærtæøite de cei mai mulfli, ceea ce distinge obiectele între ele e accentul pe carefiecare îl pune pe diverse aspecte ale acestei deconstrucflii a conceptelor tradiflionale care definesc vizualitatea.De exemplu, Mirrored Cubes a lui Morris (prin încæ o execuflie aproape literalæ a unei sugestii descoperite în GreenBox [Cutie verde, 1934] a lui Duchamp) situeazæ spectatorul pe sutura reflecfliei în oglindæ: interfafla dintre obiectulsculptural øi situl arhitectural, unde niciunul din elemente nu poate cæpæta o poziflie de prioritate sau dominaflieîn triada spectator – obiect sculptural – spafliu arhitectural. Øi, atîta vreme cît lucrarea acflioneazæ pentru a înscrieun model fenomenologic al experienflei într-un model tradiflional al specularitæflii pur vizuale øi, totodatæ, pentrua-l disloca, principalul punct asupra cæruia se concentreazæ ræmîne obiectul sculptural øi apercepflia sa vizualæ.Dimpotrivæ, Condensation Cube al lui Haacke – deøi suferæ, într-o manieræ evidentæ, de un reductivism scientist,aici chiar mai riguros instituit, øi de moøtenirea pozitivismului empiric al modernismului – abandoneazæ orelaflie specularæ cu obiectul în general, stabilind, în schimb, un sistem biofizic ca legæturæ între privitor, obiectsculptural øi sit arhitectural. Dacæ Morris reîntoarce privitorul de la un mod al specularitæflii contemplative la uncerc fenomenologic al miøcærii corporale øi al reflecfliei perceptive, Haacke înlocuieøte cîndva revoluflionarul conceptal „tactilitæflii“ care activeazæ în experienfla privitorului printr-o miøcare de închidere a fenomenologicului încadrul determinismului „sistemului“. Fiindcæ acum opera sa suspendæ „privirea“ tactilæ a lui Morris într-o sintagmæfundamentatæ øtiinflific (în acest caz, aceea a unor procese de condensare øi evaporare în interiorul unui cub,provocate de modificærile de temperaturæ datorate variafliei numærului de spectatori din galerie).Øi, în sfîrøit, trebuie sæ analizæm poate cea mai puflin credibilæ transformare a pætratului, ce-øi face apariflia în punctulculminant al artei conceptuale, în 1968, în douæ lucræri ale lui Lawrence Weiner, intitulate A Square Removalfrom a Rug in Use øi, respectiv, A 36“ X 36“ Removal to the Lathing of Support Wall of Plaster or Wallboard froma Wall (ambele publicate sau „reproduse“ în Statements, 1968), în care modificærile paradigmatice specificeoperate de arta conceptualæ asupra moøtenirii formalismului reductivist sînt cît se poate de vizibile. Ambeleintervenflii – în ciuda faptului cæ îøi pæstreazæ legæturile structurale øi morfologice cu tradiflia formalæ, prin respectareageometriei clasice ca definire a lor la nivel de formæ – se înscriu pe suprafeflele de susflinere ale institufliilorøi/sau ale caselor, pe care tradiflia le-a dezavuat întotdeauna. Covorul (probabil pentru sculpturæ) øi peretele(pentru picturæ), pe care esteticile <strong>idea</strong>liste le declaræ mereu a fi simple „anexe“, sînt aduse în prim-plan aicinu doar ca pærfli ale bazei lor materiale, ci øi ca inevitabilæ viitoare amplasare a lucrærii. În acest fel, structura,amplasarea øi materialele intervenfliei sînt, în însuøi momentul concepfliei, cu totul determinate de viitoarea lordestinaflie. Deøi niciuna din suprafefle nu e precizatæ explicit în funcflie de contextul sæu instituflional, aceastæ ambiguitatea dislocærii dæ naøtere la douæ lecturi opuse, øi totuøi reciproc complementare. Pe de-o parte, ea anihileazæaøteptarea tradiflionalæ de-a întîlni opera de artæ doar într-un loc „specializat“ sau „consacrat“ (atît „peretele“,cît øi „covorul“ ar putea aparfline fie unei case, fie unui muzeu sau, din acelaøi motiv, le-am putea la fel de bineîntîlni în orice alt loc, cum ar fi, de exemplu, un birou). Pe de altæ parte, niciuna din aceste suprafefle n-ar puteafi vreodatæ luatæ în considerare independent de amplasarea ei instituflionalæ, de vreme ce inscripflia fizicæ depe fiecare suprafaflæ genereazæ, inevitabil, lecturi contextuale ce depind de convenfliile instituflionale øi de utilizærilespecifice ale acelor suprafefle în spafliile respective.Trecînd dincolo de precizia literalæ sau perceptivæ cu care Barry øi Ryman fæcuseræ înainte legætura dintre obiectelepicturale øi pereflii folosifli, prin tradiflie, pentru expunere, dorind sæ facæ manifestæ interdependenfla lor fizicæ øiperceptivæ, cele douæ pætrate ale lui Weiner sînt acum integrate fizic atît în aceste suprafefle de susflinere, cîtøi în definirea lor instituflionalæ. Mai mult, fiindcæ inscripflia lucrærii implicæ, paradoxal, dislocarea fizicæ a suprafefleide susflinere, ea genereazæ, de asemenea, o experienflæ a retragerii perceptive. Øi, aøa cum lucrarea neagæ specularitateaobiectului artistic tradiflional printr-o retragere în sens propriu, în locul unui adaos de date vizuale înconstruct, tot astfel acest act de retragere perceptivæ opereazæ, în acelaøi timp, ca o intervenflie fizicæ (øi sim-

arhivabolicæ) asupra puterii instituflionale øi relafliilor de proprietate, subliniind pretinsa neutralitate a „simplelor“ dispozitivede reprezentare. Instalarea øi/sau achiziflia oricæreia dintre aceste lucræri reclamæ ca viitorul posesorsæ accepte o mostræ de suprimare/retragere/întrerupere fizicæ atît la nivelul ordinii instituflionale, cît øi la cel alrelafliei private de posesiune.A fost cît se poate de firesc ca, la prima mare expoziflie de artæ conceptualæ a lui Seth Siegelaub, evenimentulintitulat January 5–31, 1969, Lawrence Weiner sæ prezinte o formulæ care urma sæ opereze ca matrice întemeietoarea tuturor propozifliilor sale ulterioare. Abordînd tocmai relafliile în cadrul cærora se constituie operade artæ ca o formulæ deschisæ, structuralæ, sintagmaticæ, aceastæ declaraflie matricealæ definea parametrii opereide artæ ca fiind aceia ai condifliilor auctorialitæflii øi producfliei øi încadra interdependenfla lor faflæ de condifliile posesiuniiøi utilizærii (øi aceasta, nu în ultimul rînd, la nivel propoziflional) ca definiflie lingvisticæ determinatæ de øi variabilæîn funcflie de tofli aceøti parametri, în constelafliile lor fluctuante øi aflate într-o continuæ transformare.În privinfla diferitelor maniere de utilizare:1. Artistul poate alcætui piesa.2. Piesa poate fi fabricatæ.3. Piesa nu trebuie construitæ.Fiecare element fiind echivalent øi consecvent cu intenflia artistului, decizia în privinfla condifliilor ræmîne pe seamareceptorului, cu ocazia receptærii.Ceea ce începe sæ prindæ formæ aici este, aøadar, o criticæ ce opereazæ la nivelul „institufliei“ estetice. E o recunoaøterea faptului cæ materialele øi procedurile, suprafeflele øi texturile, spafliile øi amplasamentele nu sîntdoar o chestiune picturalæ øi sculpturalæ ce trebuie tratatæ doar în termenii unei fenomenologii a experienfleivizuale øi cognitive sau în termenii unei analize structurale a semnului (aøa cum mai credeau încæ majoritateaartiøtilor minimaliøti øi postminimaliøti), ci sînt întotdeauna deja înscrise în convenfliile limbajului øi, prin aceasta,în puterea instituflionalæ øi în investirea ideologicæ øi economicæ. Iar dacæ totuøi aceastæ recunoaøtere pæreaîncæ a fi într-un stadiu latent în lucrærile lui Weiner øi Barry de la sfîrøitul anilor 1960, ea urma sæ se facæ manifestæcu repeziciune în lucrærile artiøtilor europeni din aceeaøi generaflie, în special în cele ale lui Marcel Broodthaers,Daniel Buren øi Hans Haacke, dupæ 1966. De altfel, critica instituflionalæ a devenit punctul esenflial al atacurilorcelor trei artiøti asupra falsei neutralitæfli a vederii care furnizeazæ premisele rafliunii de-a fi a acestor instituflii.În 1965, asemenea tovaræøilor sæi americani, Buren pleacæ de la o investigaflie criticæ asupra minimalismului.Lectura precedentæ a operelor lui Flavin, Ryman, Stella i-a permis imediat dezvoltarea unor poziflii din perspectivaunei stricte analize picturale, care au condus curînd la o ræsturnare totalæ a conceptelor vizualitæflii desorginte picturalæ/sculpturalæ. Buren s-a angajat, pe de-o parte, într-o evaluare criticæ a moøtenirii picturii modernistetîrzii (øi americane postbelice), iar pe de altæ parte, într-o analizæ a moøtenirii lui Duchamp, pe care o priveaca o negare cu totul inacceptabilæ a picturii. Aceastæ variantæ proprie de lecturæ a lui Duchamp øi a readymadeuluica act de o radicalitate mic-burghezæ anarhistæ, deøi nu necesarmente corectæ øi dusæ pînæ la capæt, i-a permislui Buren sæ construiascæ o criticæ plinæ de succes a ambelor: pictura modernistæ øi readymade-ul lui Duchampca Alter-ul sæu istoric radical. În scrierile øi intervenfliile sale redactate începînd cu 1967, prin critica sa la adresaordinii speculare a picturii øi a cadrului instituflional ce o determinæ, Buren a reuøit performanfla excepflionalæde a disloca ambele paradigme, atît cea a picturii, cît øi cea a readymade-ului (chiar douæzeci de ani mai tîrziu,aceastæ criticæ face sæ paræ cu totul inoportunæ continuarea în manieræ naivæ a producfliei de obiecte dupæ modelulreadymade-ului duchampian).Din perspectiva prezentului, pare mai uøor de observat cæ atacul lui Buren la adresa lui Duchamp, mai ales încrucialul sæu eseu din 1969 intitulat Limites Critiques, era orientat, în primul rînd, împotriva convenfliilor receptæriilui Duchamp, operative øi predominante de-a lungul întregii perioade cuprinse între sfîrøitul anilor 1950øi începutul anilor ’60, mai curînd decît împotriva implicafliilor efective ale însuøi modelului lui Duchamp. Tezacentralæ a lui Buren era cæ eroarea readymade-ului duchampian consta în ocultarea condifliilor ce modeleazæcadrul instituflional øi discursiv, condiflii care i-au permis încæ de la început readymade-ului sæ-øi producæ ræsturnærileîn ce priveøte atribuirea de semnificaflie øi experienfla obiectului. Cu toate acestea, s-ar putea susfline la fel debine cæ – aøa cum o sugereazæ, de altfel, Marcel Broodthaers în catalogul expozifliei The Eagle from the Oligoceneto Today din Düsseldorf – definifliile contextuale øi construcfliile sintagmatice ale operei de artæ fuseseræ evidentinaugurate de modelul readymade-ului lui Duchamp.17

În analiza sa sistematicæ asupra elementelor constitutive ale discursului pictural, Buren a ajuns sæ cerceteze tofliparametrii producfliei øi receptærii artistice (o analizæ accidental similaræ celei a lui Lawrence Weiner care a dusla formula sa „matricealæ“). Plecînd de la minimalista dezmembrare literalæ a picturii (în special de la cea a luiRyman øi Flavin), Buren a trans<strong>format</strong> mai întîi picturalitatea într-un alt model, printre altele, de opacitate øi obiectualitate.(Lucru realizat prin întrepætrunderea fizicæ a figurii øi fundalului pe flesætura de tendæ, fæcînd din „grilajul“dungilor paralele verticale etern repetatul sæu „instrument“ øi aplicînd mecanic – aproape superstiflios øiritualic, s-ar putea spune privind în urmæ – un strat de vopsea albæ pe benzile exterioare grilajului, pentru adistinge obiectul pictural de un readymade.) Odatæ ce pînza a fost scoasæ de pe tradiflionalul øevalet, pentrua deveni un obiect textil înzestrat cu realitate fizicæ (reminiscenflæ a celebrei formule a lui Greenberg: „pînzæcare nu mai e fixatæ pe øasiu [care] existæ deja ca picturæ“), aceastæ strategie a arsenalului lui Buren øi-a gæsitcorespondentul logic în amplasarea pînzelor fixate pe øasiu, atîrnînd ca obiecte, pe un perete de sprijin øi pepodea.Aceastæ transformare a suprafeflelor-suport øi a procedeelor de producflie a avut ca rezultat, în lucrærile lui Buren,o vastæ serie de forme de distribuflie: de la pînze nefixate pe øasiu la coli de hîrtie în dungi, trimise anonim prinpoøtæ; de la pagini în cærfli la panouri publicitare. În aceeaøi manieræ, dislocærile spafliilor destinate tradiflionalintervenfliilor artistice øi lecturilor au produs o multitudine de amplasamente øi de forme de expunere care speculaumereu dialectica interior-exterior, oscilînd, astfel, între contradicfliile sculpturii øi picturii øi aducînd în primplantoate acele dispozitive vizibile sau ascunse care structureazæ ambele tradiflii în cadrul discursului muzeuluiøi al atelierului.Mai mult, adoptînd principiile criticii situaflioniste adresate diviziunii burgheze a creativitæflii conform regulilordiviziunii muncii, Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier øi Niele Toroni au per<strong>format</strong> public (cu diferite ocazii,între 1966 øi 1968) o deconstrucflie a distincfliei tradiflionale dintre artist øi public, fiecare cu rolurile sale corespunzætoare.Nu au pretins doar ca toate idiomurile lor artistice sæ fie considerate absolut echivalente øiinterøanjabile, ci øi ca producflia anonimæ a unor astfel de semne picturale de cætre public sæ fie echivalentæ celeirealizate de artiøtii înøiøi.Cu reproducerile sale fotografice – realizate în fotomate – ale chipurilor celor patru artiøti, posterul celeide-a patra manifestæri a lor la Bienala de la Paris din 1967 face o trimitere neglijentæ la o altæ sursæ majoræ achestionærilor contemporane cærora le e supusæ nofliunea de auctorialitate artisticæ, legatæ de o provocare dea participa lansatæ „publicului“: estetica antinomitæflii, aøa cum e practicatæ în „Factory“ a lui Andy Warhol, øi procedeelesale mecanice (fotografice) de producflie. 29Intervenfliile critice ale celor patru asupra unui mecanism cultural consacrat, însæ învechit (reprezentat de institufliivenerabile øi importante, ca Salon de la Jeune Peinture sau Bienala de la Paris) au scos imediat la ivealæ cel puflinunul din paradoxurile majore ale tuturor practicilor conceptuale (un paradox care, absolut întîmplætor, constituiseunica øi cea mai originalæ contribuflie adusæ de opera lui Yves Klein, cu zece ani în urmæ). Acesta era faptulcæ anihilarea criticæ a convenfliilor culturale ajunge ea însæøi, imediat, la condiflia spectacolului, cæ insistareaasupra caracterului anonim al artisticului øi deconstrucflia auctorialitæflii produc imediat nume de marcæ øi produseidentificabile øi cæ o campanie ce-øi propune sæ critice convenfliile vizualitæflii prin intervenflii textuale, semnepe panouri publicitare, comunicate anonime øi pamflete sfîrøeøte, inevitabil, prin a urma mecanismele prestabiliteale publicitæflii øi ale campaniilor de marketing.Toate lucrærile menflionate coincid totuøi în riguroasa lor redefinire a raporturilor dintre public, obiect øi autor.Øi toate se conjugæ în efortul lor de-a înlocui modelul tradiflional, ierarhic al experienflei privilegiate bazate peabilitæfli auctoriale øi pe o competenflæ de receptare dobînditæ printr-un raport structural al echivalenflelor absolute,care sæ demonteze ambele pærfli ale ecuafliei: poziflia hieraticæ a obiectului artistic unificat øi, în aceeaøi mæsuræ,poziflia privilegiatæ a autorului. Într-un eseu timpuriu (publicat, întîmplætor, în acelaøi numær din 1967 al AspenMagazine – dedicat de editorul sæu, Brian O’Doherty, lui Stéphane Mallarmé – în care a apærut øi prima traducereîn englezæ a textului „Moartea autorului“ al lui Roland Barthes), Sol LeWitt a expus, cu o uimitoare claritate,toate aceste preocupæri pentru o redistribuflie programaticæ a funcfliilor autor/artist, prezentîndu-leprintr-o surprinzætoare metaforæ a performærii unor sarcini birocratice cotidiene:Scopul artistului ar trebui sæ fie acela de-a le oferi informaflii privitorilor. [...] El ar trebui sæ-øi urmæreascæpremisa predeterminatæ pînæ la concluzie, evitînd subiectivitatea. Întîmplarea, gustul sau formele ce revininconøtient în memorie nu trebuie sæ joace niciun rol în configurarea rezultatului. Artistul serial nu18

arhivaurmæreøte producerea unui obiect frumos sau misterios, ci funcflioneazæ ca un simplu funcflionar ce catalogheazærezultatele premiselor sale [sublinierea noastræ]. 30Inevitabil însæ, apare întrebarea: cum se pot reconcilia astfel de definiflii restrictive ale artistului ca funcflionar cecatalogheazæ cu implicafliile subversive øi radicale ale artei conceptuale? Iar aceastæ întrebare trebuie pusæ, totodatæ,chiar în contextul istoric specific în care moøtenirea avangardei istorice – constructivismul øi pozitivismul– a fost doar recent reclamatæ. În ce fel, ne-am putea întreba, pot fi aliniate astfel de practici la producflia istoricæpe care au redescoperit-o artiøti ca Henry Flynt, Sol LeWitt øi George Maciunas, la începutul anilor ’60, în specialdatoritæ The Great Experiment: The Russian Art 1863–1922. 31Natura profund utopicæ (øi astæzi inimaginabil de naivæ) a revendicærilor asociate cu arta conceptualæ la sfîrøitulanilor 1960 iese la ivealæ în felul în care le-a formulat Lucy Lippard în 1969 (împreunæ cu Seth Siegelaub,care era cu siguranflæ cel mai important organizator de expoziflii øi critic al acestei miøcæri):Arta ce se vrea experienflæ puræ nu existæ pînæ cînd cineva o experimenteazæ, sfidînd posesiunea, reproducerea,uniformitatea. Arta intangibilæ poate distruge impunerea artificialæ a „culturii“ øi furniza un publicmai larg pentru o artæ obiectualæ, tangibilæ. Atunci cînd automatismul elibereazæ milioane de ore [ce potfi dedicate] timpului liber, arta ar trebui sæ cîøtige, nu sæ piardæ în importanflæ, pentru cæ, deøi arta nu e doaro destindere [play], ea e contrapunctul muncii. Ar putea sosi ziua în care arta sæ devinæ ocupaflia cotidianæa fiecæruia, deøi nu avem niciun motiv sæ credem cæ aceastæ activitate se va numi artæ. 32Deøi pare evident cæ artiøtii nu pot fi traøi la ræspundere pentru viziunile naive cultural øi politic pe care le proiecteazæasupra lucrærilor lor chiar øi cei mai competenfli, loiali øi entuziaøti critici, astæzi pare a fi la fel de evidentcæ tocmai utopismul primelor miøcæri de avangardæ (genul pe care încearcæ Lippard cu disperare sæ-l reînviecu aceastæ ocazie) a fost cel care a absentat cu desævîrøire din arta conceptualæ de-a lungul întregii sale istorii(în ciuda singurei invocæri a lui Herbert Marcuse de cætre Barry, care a caracterizat galeria comercialæ drept„un loc în care putem veni øi unde, pentru o vreme, «sîntem liberi sæ ne gîndim la ce urmeazæ sæ facem»“).Este oarecum de la sine înfleles, cel puflin din perspectiva anilor 1990, cæ, încæ de la începuturile sale, arta conceptualæs-a distins prin simflul sæu acut al limitærilor discursive øi instituflionale, prin restricfliile autoimpuse, prinlipsa unei viziuni totalizatoare, prin preocuparea sa criticæ pentru condifliile factuale ale producfliei artistice øi receptærii,færæ a aspira la depæøirea simplei facticitæfli a acestor condiflii. Acest lucru a devenit evident pe mæsuræ celucræri ca seriile Visitators’ Profiles ale lui Hans Haacke (1969–1970), cu rigoarea lor birocraticæ øi devotamentullor inexpresiv faflæ de colecfliile statistice de informaflii factuale, au respins orice dimensiune transcendentalæ.Ba mai mult, descoperim astæzi cæ tocmai totala eliberare de vraja narafliunilor politice dominante care au datforflæ majoritæflii artelor de avangardæ din anii ’20 a fost cea care, operînd într-o fuziune proprie cu formele celemai noi øi mai radicale ale reflecfliei artistice critice, dæ seama de contradicfliile aparte care acflioneazæ în arta(proto)conceptualæ din a doua jumætate a anilor 1960. Ea poate sæ explice de ce aceastæ generaflie de la începutulanilor ’60 – în tot mai pronunflatul sæu accent empirist øi în scepticicmul sæu faflæ de orice viziune utopicæ – urmasæ se simtæ atrasæ, de exemplu, de pozitivismul logic al lui Wittgenstein øi sæ îmbine pozitivismul mic-burghezafirmativ al lui Alain Robbe-Grillet cu atopismul radical al lui Samuel Beckett, declarîndu-le pe toate acesteasurse ale sale. Øi poate sæ clarifice cum de aceastæ generaflie s-a simflit la fel de atrasæ de conceptul conservatorde „sfîrøit al ideologiei“ al lui Daniel Bell øi de filosofia freudo-marxistæ a eliberærii a lui Herbert Marcuse.Totuøi, ceea ce-a obflinut mæcar temporar arta conceptualæ a fost supunerea ultimelor reziduuri ale aspiraflieiartistice spre transcendenflæ (manifestatæ prin tradiflionalele abilitæfli de atelier øi prin modalitæflile de experienflæprivilegiatæ) la o ordine riguroasæ øi implacabilæ a jargonului administrærii. Mai mult, a reuøit sæ purifice producfliaartisticæ de aspiraflia la o colaborare afirmativæ cu forflele de producflie øi de consum industrial (ultima dintreexperienflele totalizatoare în care, pentru o ultimæ datæ, s-a înscris mimetic øi plinæ de încredere producflia artisticæ,în contextul artei pop øi al minimalismului).Astfel, în mod paradoxal, s-ar pærea cæ arta conceptualæ a devenit, într-adevær, cea mai semnificativæ schimbareparadigmaticæ a producfliei artistice postbelice, exact atunci cînd mima logica operaflionalæ a capitalismuluitîrziu øi instrumentalitatea sa pozitivistæ, într-un efort de a-øi plasa investigafliile autocritice în serviciul lichidæriipînæ øi a ultimelor ræmæøifle ale experienflei estetice tradiflionale. Prin acest proces, ea a reuøit sæ se purifice înîntregime de experienfla imaginaræ øi corporalæ, de substanfla fizicæ øi de spafliul memoriei, tot aøa cum a øters19