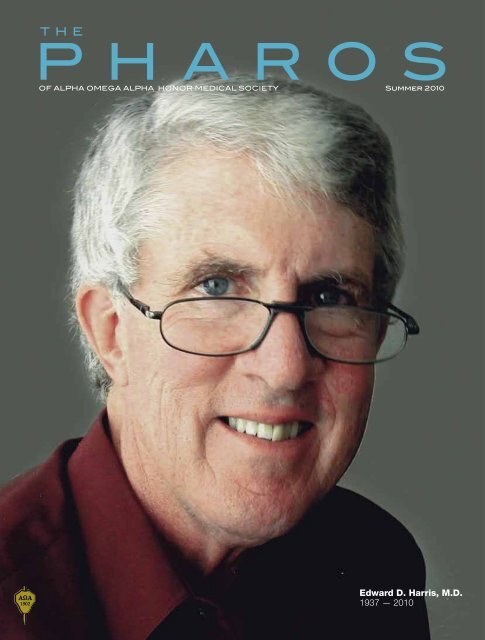

Edward D. Harris, M.D. 1937 â 2010 - Alpha Omega Alpha

Edward D. Harris, M.D. 1937 â 2010 - Alpha Omega Alpha

Edward D. Harris, M.D. 1937 â 2010 - Alpha Omega Alpha

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

!"#$%&'$#!()*$#$%&'$##'!+!,#()-./$%#0!/.)12### 034456#7898<strong>Edward</strong> D. <strong>Harris</strong>, M.D.<strong>1937</strong> — <strong>2010</strong>

!Αξιος "!ωφελε#ιν το$υς "!αλγο#υντας!"#$%&'()*$(&$+#',#$()#$+-..#'/012!"#$%&'()*%$3#/01$4'#45'#6$.&'$7)#$8)5'&9$9)&-:6$3#$(*4#6$6&-3:#;945/((#6$/0$('/4:/5($&-(:/0#6$/0$()#$>50-9#15$C:4)5$5($0&$566/(/&05:$.A1(*0'.B(#.:,:0'(":C!"#">(#>.A1(*0'

Dr. <strong>Edward</strong> D. “Ted”<strong>Harris</strong> , ExecutiveSecretary <strong>Alpha</strong> <strong>Omega</strong><strong>Alpha</strong> and Editor of ThePharos, died on May 21,<strong>2010</strong>. Ted was a distinguishedteacher, outstandingphysician, accomplishedresearcher and remarkableleader. He was an internationallyrecognized rheumatologistand former Chair of Medicine at Stanford andRutgers universities. Through his long battle with a steadilyprogressing head and neck cancer, he remained committed tohis work and the profession he cherished so dearly. He passedaway at his son’s home in Thetford Hill, Vermont.Ted was born in Philadelphia, the only son of <strong>Edward</strong>and Eleanor <strong>Harris</strong>. He excelled in academics and athleticsat the Camp Hill High School and at Dartmouth College. AtDartmouth, an injury curtailed his football career, but his educationalexperiences and English major kindled an interest inreading, writing, and editing that lasted for the rest of his life.Ted attended the two-year Dartmouth Medical School andthen graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1962, cumlaude, as a member of <strong>Alpha</strong> <strong>Omega</strong> <strong>Alpha</strong> and recipient of thedistinguished Maimonides Award. Following internship andresidency at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) andresearch training in the Experimental Therapeutic Branch ofthe National Heart Institute, he returned to Boston as a SeniorResident, Research Fellow, and then Member in the ArthritisUnit at the MGH, working closely there with his beloved mentor,Dr. Stephen Krane.The call soon came for Ted to return to Dartmouth to heada Connective Tissue Disease Section in the Department ofMedicine. His love of the outdoors and northern New Englandmade the call irresistible, so he and his family returned to Hanoverin 1973. There Ted organized a Multipurpose Arthritis Center,soon became Professor of Medicine and was recognized as anexceptional clinician, teacher, researcher, and leader. In 1983he was recruited to be Professor and Chair of the Departmentof Medicine at Rutgers Medical School and then in 1988 to beProfessor and Chair of Medicine at Stanford. Along this pathwayhe maintained his research program focusing on the natural historyand treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, his commitment toteaching, and his engagement with the medical community.Ted was a major contributor to the American College ofRheumatology, serving as President of the College in 1985 through1986. He chaired the Rheumatology Subspecialty Board for theAmerican Board of Internal Medicine from 1986 through 1988.Reflecting his broad commitment to the profession, Ted alsoserved sequentially as Governor of the New Jersey and NorthernCalifornia chapters of the American College of Physicians. Hewas a member of the Association of Professors of Medicine,American Society for Clinical Investigation, Association ofMemorial<strong>Edward</strong> D. <strong>Harris</strong>, Jr., MDJuly 7, <strong>1937</strong>–May 21, <strong>2010</strong>American Physicians, the American Clinical and ClimatologicalSociety, and the Royal College of Physicians, as well as numerousother community and professional organization. He receivedthe Class of 1958 Alumni Award from Dartmouth in 1992. TheAmerican College of Rheumatology awarded him the JosephBunim Medal in 1991 and Presidential Gold Metal in 2007. He iswell known throughout the world as co-editor of the Textbook ofRheumatology.Ted’s friendliness and ease of engagement with others wereamong his exceptional qualities. I recognized this quality whenwe first met during our residency days. Dr. Ruth-Marie Fincher,now Professor of Medicine at the Medical College of Georgiarecently wrote,Ted has been a role model and supporter-from-afar for me since1973, when he taught the musculoskeletal component of ourScientific Basis of Medicine curriculum at Dartmouth MedicalSchool. I remember him as a dashing young professor (assistant,actually) who expected and received respect and undivided attention;he was a marvelous teacher who made collagen andbone come alive. I cherish the opportunities I had throughthe ACP Board of Governors and AΩA Board of Directorsto work with Ted. I remember vividly the evening he walkedup to the cellist of a string quartet that was playing at an ACPBoard of Governors reception. After a brief conversation, thecellist stepped aside and Ted was playing with the quartet. Hishandling of the end of his life seems typical to me of the strong,“in control” way he handled his career.AΩA selected Ted to be Executive Secretary and Editor ofThe Pharos in 1997. He served with distinction, reinvigoratingthe organization through chapter visits, recruitment of newchapter councilors, regional and national meetings for councilors,and in many other ways. He steered The Pharos to a morecreative, attractive, and modern format and wrote colorfullyabout the changing face of American medicine. He selected thearticles for and edited Creative Healers, an anthology of memorablearticles from The Pharos.In tribute to Ted, the Board of Directors of AΩA has renamedthe AΩA Professionalism Award the <strong>Edward</strong> D. <strong>Harris</strong>Professionalism Award. Donations in Ted’s name will be placedin a fund to support this, with a goal of creating an endowmentto support the award.Friends and family were always very important to Ted<strong>Harris</strong>. He is missed by his fiancée Dr. Eileen Moynihan, hissons Ned, Tom, and Chandler, and their wives and children, aswell as by his former wife, Mary Ann Hayward, the many studentshe mentored, and medical colleagues around the globe.Ted gave so much of his life and spirit to medicine. We weredeeply blessed by his many contributions.David C. Dale, MD(AΩA, Harvard Medical School, 1966)President of <strong>Alpha</strong> <strong>Omega</strong> <strong>Alpha</strong>, 1996–2002Professor of Medicine, University of WashingtonThe Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong> 1

In ThisDEPARTMENTSARTICLES1 Memorial<strong>Edward</strong> D. <strong>Harris</strong>, Jr., MDJuly 7, <strong>1937</strong> — May 21, <strong>2010</strong>David C. Dale, MDMedical publishingWill paper live on?Michael D. Lockshin, MD, MACRHealth policy374The inadequacy of legislativeprocedures and the infirmity ofphysician organizationsDan F. Kopen MDDirect-to-consumer advertisingFrancis J. Haddy, MD, PhDAlmost five years laterReviews and reflectionsA Second Opinion: RescuingAmerica’s Health Care: A Planfor Universal Coverage ServingFred A. Lopez, MDPatients Over ProfitReviewed by Robert A. Chase, MD8The Language of Life: DNA andthe Revolution in PersonalizedMedicineReviewed by Thoru Pederson, PhDOne Breath Apart: FacingDissectionReviewed by Robert A. Chase, MDNeedlestickDoctors in Fiction: Lessons fromDavid Muller, MDLiteratureReviewed by Jack Coulehan, MDThe physician at the movies45 12Peter E. Dans, MDAmeliaNight at the Museum: The Battleof the SmithsonianPage 4Julie and JuliaThe Young Victoria50 Letters Page 840Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans healthcare, and the Louisiana State UniversityHealth Sciences Center

Issue On the coverSee page 1Page 12Love songMichael Nissenblatt, MD14SemmelweisMagyar warriorDean D. Richards III, MD16The winning photos from the WebSite Photography Contest22Page 145254547The3536394453INSIDEBACK54 COVERBACKCOVER54AΩA NEWS<strong>2010</strong> Helen H. GlaserStudent Essay Awards<strong>2010</strong> Pharos PoetryCompetition winners<strong>2010</strong> Carolyn L. KuckeinStudent ResearchFellowshipsNational and chapter newsMemorial donationsInterim editorPOETRYAtheist Faces DeathMyron F. Weiner, MDEndings Are BeginningsEric Pfeiffer, MDWhen I Gets BigAlan Blum, MDOde to a Jaundiced EyePaul L. Wolf, MDWhat Would Heifetz Do?Emanuel E. Garcia, MDThe CandidateHerbert T. Abelson, MDThe GazeBlair P. Grubb, MDSpring of My DyingRaymond C. Roy, MD, PhDPage 22

!"#$%&'()*+'$,-$./(Michael D. Lockshin, MD, MACRThe author (AΩA, Cornell University, 1979)is the professor of Medicine and Obstetrics-Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medical College,the editor of Arthritis & Rheumatism, and amember of the editorial board of The Pharos.For more than 150 years medical professionalshave published new scientific data,in paper journals, for an audience of professionalpeers. Since 1938 <strong>Alpha</strong> <strong>Omega</strong> <strong>Alpha</strong>,for an audience of medical leaders, has publishedin The Pharos articles on medically- related history,literature, art, ethics, economics, healthpolicy, personal profiles, nonfiction, poetry,photography, and personal essays.The Internet has changed paper publishingfor medical journals and may do so forThe Pharos. On the Internet, medical andscientific journals can now offer instant publication(even before or without peer review),hyperlinks, and interactive files. The audienceof medical journals is no longer just cognoscentibut is now, potentially,Illustration Erica Aitken

Will paper live on?the world. Because of the Internet, editors andpublishers of medical journals must re-ask oldquestions: Why do we publish? Why do we dopeer review? Should we edit manuscripts? Isa paper publication better than a digital one?Who are our readers? Who pays the costs? Isthere a need for a society- sponsored journal?Will paper journals die?ways to do this as well. Instead, a journal functionsin academia as a means to provide qualityvalidation for both reader and writer. Because ofpeer- review validation, faculty promotion andgrant application review committees use journalpublications to judge candidates. The openInternet, lacking peer review, cannot similarlyWhy do we publish?Anticipating protests to my assertion, I averthat: the purpose of a journal is not to solicit critiqueby one’s peers, since personal contacts andresearch results placed directly online can anddo accomplish the same goal. Nor is the purposeof publication solely to disseminate information,since the Internet and public press offer many

Medical publishingvalidate science. Another of a journal’s purposes is to be afilter. While a Google or PubMed search on a topic may yieldthousands of citations, a journal offers a narrow, more usable,list of papers relevant to the reader. A journal’s “brand name”guarantees the reader a predictable quality and content, whilethe Internet does not.Why do we do peer review?Some argue that peer review is unnecessary, that readerscan judge a manuscript themselves, and that manuscripts canbe placed online without peer review. The counterargumentis that peer review assumes that at least some readers may beunable to make informed judgments on difficult topics and thatthey do wish an expert’s guidance. All journals offer editorialsto explain complex issues or to set context—a fact that supportsthis view.As an editor, most recently of Arthritis and Rheumatism, Istrongly favor peer review: reviewers identify errors and omissionsin the original research, suggest better experiments, offeralternative explanations, and explain technical obscurities andpriorities. Even for the nontechnical articles published in ThePharos, reviewers often suggest better ways of expression orbetter ways to make an argument, and they suggest prioritiesfor publication as well. Peer review sets a timeline for decision,giving a published paper an address in time and space, whileongoing blogs on the Internet do not. Formal peer review isvalid because editors know the skill of the reviewers. In peerreview, arbitration is available to resolve disputes, reviewers(and publishers) demand a standardized presentation style,and post- publication comment is possible through a definedprocess. Public blog review lacks these attributes.Although peer review is expensive and cumbersome, thehypothesis that open, voluntary criticism results in a betterfinal product than does peer review remains unproved.Conventional peer review is alive and well; there is not a compellingreason to seek an alternative.Should we edit manuscripts?Once accepted, scientific manuscripts undergo editing forstyle, format, fact checking, internal contradiction checking,verification of permissions, and evaluation for legibility (bothfigures and language)—expensive and time consuming work.Copy editors change the original manuscript to1. Clarify meaning and to make the manuscript harmoniouswith the journal’s style2. Identify inconsistencies between table and text andwithin the text3. Restructure text to place methods in the methods sectionand results and conclusions in their respective correctpositions4. Note frank errors, such as pointing out that a figure doesnot show what its caption claims.Similar editing improves The Pharos as well.Is a paper publication better than a digital one?Advantages of Internet-based publication are that datacan be updated, corrected, and manipulated by authors orreaders, and that communications can be posted as soon asthey are received. A disadvantage is that constant updating ofmanuscripts results in public availability of several versions,depending on when and how it is accessed. Without arguingthe point in detail, the ability to provide an archival paperversion of a paper is an important advantage of paper publication.The Internet has not yet proved that it can achieve equalpermanence. Electronic publishing also has a risk: today’s technologiesmay become outdated or non- usable. Who now usesBasic- or DOS-based programs, or 5.25-inch floppy disks? Butwe can still read the Dead Sea Scrolls.Print journals format pages, figures, fonts, and other aspectsof their brands, place content in sequence, and group articlesby theme. These features are less reliably part of Internet publication.Whether they add significant value to the former ordetract from the latter will be for the future to judge.Who are our readers?From ancient times to the present, audiences of medicaljournals have been other specialists—not nonspecialists, andnot the general public. Results of scientific research reach thepublic through the lay press. The Pharos aims for an audienceof thinkers and leaders in the philosophy and intellect ofmedicine.No one argues that the world at large—a broader audiencethan The Pharos and conventional medical journals target—wants to read basic, clinical, or philosophical science unfilteredby interlocutors. It is appropriate for journals to focus on anarrow group of readers. Scientific journals need not dumbdown or popularize their articles to accommodate the wideraudience, nor should The Pharos change its style to attract anaudience it cannot define.Who pays the costs?Today’s medical journals are financed by sponsors, such asspecialty societies including AΩA, by subscriptions, and byadvertisements—the user-pays fiscal model. The Public Libraryof Science charges authors large submission and publicationfees. This author-pays model embodies an inherent danger ofbecoming a vanity press that will favor articles by those withthe ability to pay.The question of who should pay for publication—the producersor the consumers—is open to debate. Publishers ofprint journals are aware that Internet users expect free accessand that user costs may cause publishers to lose market share.What is not subject to debate is that manuscript receipt,review, editing, formatting, and distribution are costly andthat someone must pay. (The actual paper costs of a journalare a small portion of the total cost; mailing costs, however,are high.) While some highly- funded scientists may shrug theirshoulders and happily pay author fees through their grants,many clinical papers, and the papers in The Pharos, will notthrive in an author-pays world. On-line advertising, societysponsorship, and full or partial access fees will be necessary tosupport journals whose authors cannot pay publication costs.6 The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong>

Is there a need for a society-sponsored journal?Society- sponsored subspecialty journals focus topics andprioritize papers to their readers’ interests; give identity to theirsponsoring societies; give brand name recognition to authors,papers, and readers; and publish papers that are not sponsoredby government and industry. Whether society- sponsored journalswill survive in an era in which articles can be easily foundby topic search on the Internet is an open question, but if thespecial interest journals that assemble these articles disappear,the papers that would have been published only in the journalsthat are now gone will not be found in Google. Subspecialtysocieties, including AΩA, provide venues for writers for andreaders in special audiences.The technology of how journals do their work—whether onpaper or electronically—is a relatively small question, a fiscalone, not central to a journal’s mission. Journals and magazinesshould constantly reconsider what they do—what they shouldpublish, to whom should they address their content—but toalter their basic missions or to change their target audiencesbecause of opportunities or threats caused by online publishingis wrong.Will paper journals die?Everyone I know now reads the New York Times online.My family and I buy our books on Kindle and on the iPhone.Medical students read textbooks on computers, even “dissect”anatomy specimens digitally. Many journals offer podcastversions of their papers. Medical residents and young facultymembers download papers to iPods or personal data assistants,upload to desktops and/or print if necessary, and dispense withpaper copies of journals altogether. Older readers who favorpaper journals point out that printed pages can be torn outand filed, that journals and magazines can be stacked on a deskuntil read, or carried on an airplane, and that paper journalsoffer browsing serendipities. But electronic papers can alsobe downloaded, filed, or carried. Electronic browsing is easy,although qualitatively different from paper browsing; offeringhypertext links, it can be more powerful. Paper publicationoffers permanence as an advantage over electronic publicationand convenience in open libraries, but technology will presumablyfind a way to store readable electrons in perpetuity, if innovativetechnologies can constantly update disused electroniclanguages and machines. On the other hand, electronic publicationallows interactive data and graphics, motion and sound,accessible links (including conversation between author andreader), worldwide access, and worldwide communication atany hour. Electronic publication must supplant paper. The firstquestion is when. The second is how (not if) contemporaryjournals will adapt.!"#$%&"#'(&$)*+#($,#*&"My moleculesConquered by entropyWill mixWith those of parentsAnd unknown parents past.I am readyfor infinityFor nothingnessFor sleep eternalAbsent awareness,pleasure and painI know the wisdom of WilderIn Our Town; inThe turning and looseningof the dead from living.For their sakeThe living bid me farewell.But I will fare neither illNor well becauseI will not be.Myron F. Weiner, MDDr. Weiner (AΩA, Tulane University School ofMedicine, ) is clinical professor of Psychiatryand Neurology at the University of TexasSouthwestern Medical Center in Dallas. Hisaddress is: Still Forest Drive, Dallas, Texas. E-mail: myronweiner@tx.rr.com.The author’s address is:Hospital for Special Surgery535 E. 70th StreetNew York, New York 10021E-mail: lockshinm@hss.eduErica AitkenThe Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong> 7

!"#$%&'()*+',+-Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans health care, and the LouisianaState University Health Sciences CenterFred A. Lopez, MD8 The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong>

Team members Phil Hoang, Bill Leefe,Rusty Rodriguez, Fred Lopez andMelissa McKay.All photos courtesy of the author.The author (AΩA, Louisiana State University, 1991) is assistantdean for Student Affairs, the Richard Vial Professor andVice Chair of the Department of Medicine at the LouisianaState University Health Sciences Center, and the secretarytreasurer of the AΩA chapter at LSU..%'"-&+.Introductory notesDr. Lopez’s original account of his experiences in CharityHospital during Hurricane Katrina was published in theWinter 2006 issue (“In the Eye of the Storm: Charity Hospitaland Hurricane Katrina,” pp. 4–10, and available on our website). The last sentences of his essay still resonate today, “It istime to launch a new Charity. We owe this to our patients.”Dr. Lopez recounted the phased return of the LSU Schoolof Medicine to New Orleans in the Summer 2007 issue (“Inthe Wake of Katrina: An Update on the Louisiana StateUniversity School of Medicine in New Orleans,” pp. 22–23,and available on our web site) and outlined the steps forwardfor LSU and the health care delivery system in Louisiana.In this latest account of the series, Dr. Lopez describes theprogress made in the five years since Katrina in rebuilding thehealth care delivery system in New Orleans. Charity Hospital,for now, remains closed.<strong>Edward</strong> D. <strong>Harris</strong>, Jr., MD, editorArecent report in the New York Times about the eventssurrounding Hurricane Katrina and possible euthanasiaat Memorial Medical Center in uptown NewOrleans, where forty-five deaths occurred in late August 2005,served to highlight the importance of disaster preparedness. 1The article received national attention for the questions itThe Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong> 9

Almost five years laterraises about physician responsibilities during dire situationsin which rationing of resources, comfort care, personalsafety, physician accountability, and the unpredictability oflife converge to create medico- ethical- legal conundrumsof which even the most creative writer could not conceive.Conversations centering on such questions are long overdue,and already legal reform to protect health care providers inthese situations is being implemented in Louisiana. The rekindlingof interest in these ramifications of Hurricane Katrinashould also serve as reminders of other significant legaciescreated in the wake of this disaster.The 2006 return of the LSU School of Medicine to NewOrleans and the reopening of one of its downtown teachingpublic hospitals (previously known as University Hospital),with state-of-the-art trauma center and intensive care unitservices, heralded the recovery of the medical school andhealth sciences center. Subsequent positive changes includethe reopening of a 20,000-square-foot student learningcenter with both small-group and large- conference facilitiesand patient- simulation teaching capabilities; the initialconstruction of a new 175,000-square-foot cancer researchcenter in collaboration with Tulane University Health SciencesCenter and Xavier University; replenishment of LSU’s basicscience and clinical faculty; and the successful recruitmentof residents pursuing medical specialty training. The latteris particularly important for an institution that trains morethan seventy percent of the active primary care physicians inLouisiana.Amidst this momentum, particular attention is being paidto how to best care for a New Orleans population with anuninsured rate significantly greater than the national average,while jumpstarting a downtown medical district renaissancethat could provide the economic vitality and an infrastructureto retain our best students, trainees, and faculty, and attracthigh- quality candidates from elsewhere. 2 Historically, thedowntown public medical complex (known as the MedicalCenter of Louisiana at New Orleans—MCLNO—and comprisedof University and Charity Hospitals) was a major teachinginstitution for both the LSU and Tulane Health SciencesCenters, as well as the health care safety net for the underinsuredin both outpatient and inpatient settings. In the yearbefore Katrina struck, MCLNO had more than 260,000outpatient visits, 23,000 admissions, and 119,000 emergencydepartment visits. 3Decentralization of ambulatory services into communitysettings is one strategy for the improvement of patient care inCharity Hospital has remained closed since September 2005.

The former University Hospital now has 275 regularly staffed beds and is the regional Level 1 Trauma Center.the post-Katrina era. Community-based primary care clinicsnot only enhance access to preventive care but also allow forexposure of our young trainees to other models of care.Another area of intense attention is Charity Hospital,an icon of indigent care in Louisiana since 1736, which hasbeen closed since its post-Katrina evacuation on September2, 2005. Charity’s future lies in either restoring the currentstructure or building a new hospital in a nearby location,proximal to a new VA Hospital. The discussion aboutCharity has been lengthy and often vitriolic, engenderingstrong emotions from stakeholders in the residential,medical, business, and preservationist communities. A replacementhospital moved closer to realization when a memorandumof understanding regarding the governance of thisnew university academic medical center was announced inlate August 2009. And in January <strong>2010</strong> a federal arbitrationpanel awarded the state of Louisiana $474.7 million to coverdamages to and the replacement cost of Charity, providinga strong boost to the financing plan for the new teachinghospital. For many of us, it cannot happen soon enough.The future strength of the health sciences center, the state’ssupply of physicians, and the health care of so many in ourregion depend on it.References1. Fink S. Strained by Katrina, a hospital faced deadlychoices. New York Times Magazine 2009 Aug 30. www.nytimes.com/2009/08/30/magazine/30doctors.html.2. Rowland D. Health Care in New Orleans: Progress and RemainingChallenges. Testimony before the U.S. House of RepresentativesCommittee on Oversight and Government Reform hearing: Post-Katrina Recovery: Restoring Health Care in the New Orleans Region.2009 Dec 3. oversight.house.gov/images/stories/Hearings/Committee_on_Oversight/120309_Katrina/TESTIMONY-Rowland.pdf.3. Townsend R. Outline of Testimony before the U.S. Houseof Representatives Committee on Oversight and GovernmentReform hearing: Post-Katrina Recovery: Restoring Health Carein the New Orleans Region. 2009 Dec 3. oversight.house.gov/images/stories/Hearings/Committee_on_Oversight/120309_Katrina/TESTIMONY-Townsend.pdf: 1, 4.The author’s address is:LSU Health Sciences Center2020 Gravier StreetRoom 707New Orleans, Louisiana 70112E-mail: alopez1@lsuhsc.eduThe Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong> 11

The author (AΩA, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, 1995)is dean for Medical Education at the Mount Sinai School ofMedicine.As I slid the butterfly into the nearly-filled sharps box,the delicate tubing curled back on itself as if refusingto enter, and the business end plunged deep into myungloved thumb. Stunned, I quickly pulled away and pulledthe needle out. I wasn’t bleeding, but there had definitely beenblood in the needle from the blood gas I had just performedon my patient with DKA. In the ensuing moments I had anout-of- body experience. The Bellevue ER sights, sounds, andsmells faded into the distance and all that existed was mythrobbing thumb, the guilty sharps box, and my mortality.In 1990 the beds in Bellevue hospital were filled with HIVinfected, IV-drug- abusing, frequently homeless men andwomen. They came in with PCP and Kaposi’s sarcoma, butthey also came in with fevers of unknown origin (“shooter witha fever”) and lots of bread and butter medicine.In 1990, as a third-year clerk at Bellevue, mypockets were filled with the paraphernalia of everydaymedical ward work. While students atsome other schools carried pocket guides of differentialdiagnosis, Glasgow coma scales, and Snelleneye charts, at Bellevue you carried equipment andlsupplies or you didn’t survive. The words “ancillaryservices” didn’t exist in our vocabulary. We drew allthe bloods, put in all the IVs, collected and measuredurine and stool, transported patients, checkedNeedlest ckfingersticks, you name it.And gloves? They just got in the way. Wealways wore them for procedures that didn’trequire fine manual dexterity: a central line orlumbar puncture. But try to find a flutteringradial artery or a tiny vein on the dorsum of anDavid Muller, MDaddict’s foot with a gloved hand. Perfectly executed“scut” was indispensable if you wanted honors, and noone was going to jeopardize that by wearing gloves for everylittle thing.The drawback to Bellevue was that I spent hours every daydoing scut instead of learning. My day revolved around thedaily labs that had to be drawn and my week revolved arounda schedule of every-third-day IV changes for all my patients.The benefit (far outweighing the drawback) was that Ibecame expert at scut. I could draw blood from a stone, produceclear spinal fluid (the “champagne tap”) from the mostcombative patient, get a Foley past the biggest prostate. Evenmore important, the scut put me in constant contact withmy patients. I spent more time with them, got to know them,cajoled, pleaded, and threatened them on a daily basis for thesake of yet another CBC or a new IV.How else would I have discovered that “Doc” was my newpatient’s street moniker? He came in with fever and not muchelse, which to him meant a safe, clean bed and three squaremeals a day, at least until his blood cultures came back negative.12 The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong>

He was calm and cooperative during my admission H&P,letting me attempt the requisite three sets of blood cultures.But this time my painstakingly honed skills actually failed me.I tried the dorsum of his hands, his wrists, his antecubitalveins, forearms, feet, and groin. He was scarred down froma lifetime of injecting and skin- popping drugs. I was about totry an arterial stick when he said good- naturedly, “Can I trybefore you really hurt me?” When I looked at him in disbeliefhe explained that on the street he was known as Doc becauseof his ability to find a vein in even the most hardened addicts.Every clinical and social instinct I had was telling me notto, but I found myself handing him my butterfly needle andblood culture bottles. He looked at the butterfly and said,“Don’t you have a real needle”? When I produced a handfulof 10 cc syringes with inch-and-a-half-long 20-gauge needles,he smiled and pointed to a patch of skin midway up his innerright thigh. Not a vein in sight, but I dutifully appliedthe betadine and prepped the area. He uncapped the needleand without hesitating plunged it deep into his thigh. Pullingback on the syringe he easily filled it, earning him my undyinggratitude and admiration.I was called away to my next admission, a young womanwith Type 1 diabetes and DKA. This was what I had beenwaiting for—a chance to impress my resident and attending,review my pathophysiology, and monitor her acid-base statusby performing lots of ABGs (the way things were done in the“days of the giants”). I gloated to everyone within earshotabout my new admission but, because I was so excited, didnot notice the grins and knowing glances I was getting fromthe senior residents.The patient was perfect—sick enough to require carefulmetabolic monitoring but not so sick that she’d keep me up allnight. She was young, attractive, intelligent, and gave a goodhistory. She had been symptomatic for several days, wasn’tsure why she slipped into DKA, and was more than happy tocomply with any test or procedure I wanted to perform.We spent some quality time together over the next sixhours while waiting for a bed to open up on the ward, shegradually improving while I reviewed urinalyses and bloodgases. When a passing ER attending greeted her with unusualfamiliarity I realized I might get some valuable past historyfrom him. But when I asked he looked at me in disbelief,amazed that I had no idea who I was treating.She was apparently known to every intern and resident inthe hospital. Despite routinely maintaining excellent control ofher diabetes as an outpatient, she managed toget herself admitted almost monthly for DKA.This was because her only source of incomewas prostitution, and turning tricks in thehospital was safer and cleaner than doing it inthe streets. All it took was a few missed dosesof insulin to land her in one of those covetedsafe, clean beds. I learned from the attendingthat she was a model patient on admission,but later would rarely be found in her ownbed during her hospital stay. She was typically working otherpatients’ rooms and counted the prison-ward guards amongher clientele.I was stunned. Now I understood all the knowing looks Ihad gotten from the housestaff.The very next blood gas was the one that ended up in mythumb, with subsequent visions of HIV and non-A, non-Bhepatitis floating in my head. She had reported being HIVnegative when I had taken her initial history, but had also deniedany major risk factors for contracting HIV or hepatitis. Ididn’t know what to believe.Was I really at risk? Was I supposed to tell someone whathappened? And was I willing to risk looking sloppy and uninformed,possibly even incurring the wrath of my resident for(1) not wearing gloves, (2) overstuffing a sharps box, and (3)slowing us down on an on-call night?In 1990 we didn’t talk about needlesticks and tried not tothink too much about contracting anything serious from ourpatients. This was especially ironic at Bellevue, where practicallyevery patient we cared for either had AIDS or was at highrisk for contracting it.So I told no one except my wife, who accepted it with thequiet fortitude that got us through medical school and residency,and I did nothing except check my patient’s blood forHIV and hepatitis. She was negative for both but somehowthat did not provide much solace in the ensuing months.My first needlestick was, happily, my only one. It helped medevelop a newfound respect for sharps boxes and a more deliberateapproach to procedures. Since then I have taught hundredsof students and residents how to do procedures, alwaysinsisting that wearing gloves must be their first priority. But Istill struggle with the need to wear gloves all the time. Physicalcontact with patients, not to mentionthe quest for those tiny arteries,still seems too important tosacrifice to a layer of latex.The author’s address is:Mount Sinai School of MedicineBox 1255One Gustave L. Levy PlaceNew York, New York 10029E-mail: david.muller@mssm.eduThe Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong> 13

Michael Nissenblatt, MDThe author (AΩA, ColumbiaUniversity, 1972) is associate directorof Oncology at the Robert WoodJohnson University of Medicine andDentistry.John, a former patient of mine, wasa retired television announcer whohad worked with a national telecommunicationsfirm for nearly fortyyears.John was well groomed and attractive.Appearances were critical to hissuccess. The blend of his oversized,luminous, baritone voice with hisgleaming opal eyes was visually overshadowedby his incongruently long,color- enhanced, roan hair and his flawlessskin, purified and renovated by the,admitted, nightly application of emollientsand creams designed to providethe youth enhancing qualities essentialfor his career. And they hid well thepassage oftime.But Johncould nothide his agingmind. Overthe years he waslosing it—hismemory. Hisknowledgeof the world,his once- vividrecollection ofepisodes of hislife and family, hisworldliness . . . wasgone. But never didhe lose the musicality hehad acquired during yearsof professional training in theperforming arts and in preparation forlive stage performances.John developed prostate cancer inlate 2006. The disease was hidden bythe absence of pain and by John’s inabilityto sense, or report, changes inhis body. But it finally surfaced whena blockage to both kidneys causedflank swelling and fever. For years,he needed tubes for drainage and tocontrol infection. And for years helonged to escape definitive treatmentfor the disease because that mightalter his image. Ultimately treatmentbegan and was modified to allow himto maintain his appearance. For threeyears we were able to avoid rash andhair loss and lower the risk for infectionwhile still being able to shrink thetumor and restore his quality of life.During that period, John needed onlybrief hospitalizations for stents, slightlylonger hospitalizations for infections,but no hospitalization for problemsrelated to treatment itself. Treatmentwas selected to avoid what could bea disorienting discrepancy betweenwhat his eyes might see and what hisdementia might expect after decadesof image enhancing cosmetics. Such adisconnect would only be further disorienting.He was lovingly cared for byhis wife of forty years.During one of John’s last hospitalizations,I witnessed a curious event.John was singing. He was singing lovesongs. He sang complete songs fromstart to flourishing finish with properphrasing, beautiful intonation, andremarkable expression and emotion.“Moon River,” “Black Magic,” “Crazyfor You,” “Always on My Mind” pouredforth perfectly, filled with the eloquenceand baritone quality one mightexpect from a performer. But John didnot know the names of any of thesesongs. John did not even know wherehe was when his rendition of thesesongs was prompted by a request. Itwas like pushing a button on a jukebox:out came a song. No cognizanceexisted beforehand, and none followed.But while singing John seemed to befilled with a great sense of accomplishment,happiness, and joy. He camealive and was at peace. There wassalvation.A few weeks before he died, Johncame to my office. He was preoccupiedand seemed in deep thought. I hadnever seen him like this before. He wasslightly dysphoric and not the leastdespondent. His eyes were thoughtful.His disposition was introspective.His body language was less open thanusual, as his shoulders shrugged andhis head weighed heavily upon his neckas though bearing down on him. Helooked up. I asked him what he wasthinking. He said, “Doc, it is coming,I know it is coming, I can feel it, andI just want to tell you thank you formaking my life a joy. Thank you forgiving me happiness. Thank you forloving Sonya, and for guiding her.” Hisarms then lifted from his knees andembraced my shoulders, hugging metightly, and ending with a soft, gentlekiss on my left cheek. He seemed atease. He relaxed.Only a few days later, I received acall from Sonya. John had been singing.He had been singing a love song.And in the midst of an aria of love,14 The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong>

devotionally bequeathed to his wifeand children, he died. The words oflove were on his lips when, in full voiceon that night, the grandeur of loveswept him away.The author’s address is:Central Jersey Oncology Center205 Easton AvenueNew Brunswick, New Jersey 08901E-mail: mjnmotor@aol.comThe Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong> 15

!"#$%&''&'($)"*+*,$$-.*/$+"#$$0#1$2&+#$$3"*+*(.4)"5$6*'+#,+The winning photographs from our web sitephotography contest began appearing onour web site on April 1, <strong>2010</strong>. The purpose ofthe contest: To encourage photography that illustratesA A’s motto: “Be Worthy to Serve theSuffering.” The winning photos are profiled on thefollowing pages.22 The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong>

April <strong>2010</strong>—Charles Timothy Floyd, MDAn injured Iraqi boy is examined at a U.S. Army ForwardSurgical Hospital near Baghdad, April 2003.Dr. Floyd’s e-mail address is: timfloydmd@mac.com.The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong> 23

Web site photography contestMay <strong>2010</strong>—Heather MichaelI recently volunteered with a mobile clinic in Kenya. We journeyed far and wide toreach patients who would otherwise have no access to medical care. I don’t knowwhich part of our work was more difficult: the process of getting to our patients, orour medical duties. No matter where fate took us, the paths were ridden with obstacles.From flat tires to washed-out roads, we encountered daily road blocks. Yetour determination always prevailed. Neither mud nor engine failure could thwartour efforts to reach our patients. Our resilient clinic brought new meaning to theword “mobile.”Ms. Michael’s e-mail address is: heather.c.michael@gmail.com.24 The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong>

July <strong>2010</strong>—James D. VanHoose, MDYoung Haitian refugee Effie Pierre is greeted by her new foster mother SandyTucker as she arrives in Lexington, Kentucky, for medical treatment. Mrs. Tuckerand her husband have taken in more than one hundred disadvantaged andmedically-needy children into their home in Casey County, Kentucky, over the lasttwenty-five years. More information about their mission at: www.galileanhome.org.Dr. VanHoose’s e-mail address is: jdvhmd@yahoo.com.The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong> 25

Web site photography contestAugust <strong>2010</strong>—Ebby Elahi, MDWhile visiting one of the villages in Western Burundi on a medical mission in2008, I came across a little shack where this little girl lived with her parents, fourother siblings, and their livestock. eir mother had been called a witch and hadfled from another village in fear for her life. e family clearly had no income andate only occasionally. I found the little girl’s expression very telling of the traumashe had suffered during her short life. Sadly, her case was far more the norm thanthe exception.Dr. Elahi’s e-mail address is: ebbyelahi@gmail.com.26 The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong>

September <strong>2010</strong>—Sarah AbdullaDuring a stop on a train in ailand, I looked to my right and saw that the windowperfectly framed a striking tree. At the base of the tree were bright pink flowers.e strong tree and beautiful flowers contrast with the seemingly helpless women.e bright light of the window contrasts with the darkness inside the train. Capturingthe picture was also a symbol of chance: if the train had stopped only acouple of feet ahead or a couple of feet behind, the picture would not have beenpossible.Ms. Abdulla’s e-mail address is: sarah1abdulla@gmail.com.The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong> 27

Web site photography contestOctober <strong>2010</strong>—Felicia JinwalaI composed this photo using a double exposure method, in which one roll of filmwas shot twice, each time at half the exposure. e primary image captures a solitaryman walking his dog, confronted by a “fork in the road” at the local park. eoverlapping image, randomly imposed on the first, is a close up of blossomingdaffodils, their search for the sun conveying a sense of hope. In medicine, individualsare often challenged with making difficult choices, but I think there is aguiding principle of patience, worthiness, and knowledge that shapes the path oftreatment.Ms. Jinwala’s e-mail address is: jinwalfn@umdnj.edu.28 The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong>

November <strong>2010</strong>—Kavya ReddyIn loving memory of my grandfather“Be Worthy to Serve the Suffering”Lend a hand,A hand to heal,To heal those who suffer,Who suffer every day,Everyday . . . somewhere.Somewhere,There is someoneWith endless compassion for humanity,Who strives to be worthy,Worthy of serving,Serving those in need,In need of a hand,A hand that can heal.Ms. Reddy’s e-mail address is: kreddy815@gmail.com.

Web site photography contestDecember <strong>2010</strong>—Brittany SolarCabaret, Haiti, summer of 2009: Located in the side of a mountain, Grace House ishome to ailing Haitians and children of sick mothers and fathers. e woman onthe left is screaming with abdominal pain while the man works to comfort her. echildren are eating fresh mangos from the market, the first food they have eatenin days. Scenes like this are reminders that health care takes on many faces andsometimes the only medicine available is nutrition and comfort.Ms. Solar’s e-mail is brittany.k.solar@uth.tmc.edu.30 The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong>

January <strong>2010</strong>—Alison FreemanI took this photo while working in a refugee camp in eastern Kenya. Walkingthrough the “blocks” one day, I turned around to find a dozen kids following mearound; they would giggle and scatter, only to start following me again when Iturned my back. is is my favorite photo of that day. e smiles on their facesseem to exemplify the very innocence and happiness of childhood, even those thatgrow up in such poverty. I find it very hopeful and it reminds me why I continue topursue a career in international medicine.Ms. Freeman’s e-mail address is: freeman.alison@gmail.com.The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong> 31

Web site photography contestFebruary 2011—Warren “Jay” Huber III, PhDEven in the most dire circumstances, a mother’s love is unconditional. Her handsof comfort work in concert with the light of life and modern medicine to supportthe will to live. My daughter, Maryn Alice Huber, was born April 14, 2009,at twenty-six weeks and four days gestation. Weighing only one pound thirteenounces, and at twelve inches in length, Maryn endured countless nights of uncertainty.is photograph was taken during her second night in the NeonatalIntensive Care Unit. roughout the eighty days in the NICU, Maryn was treatedby a number of selfless nurses and one physician in particular who portrayed acomforting level of passion and empathy.Dr. Huber’s e-mail address is: whuber@lsuhsc.edu.32 The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong>

March 2011—Justin PalmoreI fervently believe that everyone is “worthy to serve the suffering.” It is not a matterof worth, it is a matter of heart, a matter of passion, and as this picture so candidlyportrays, a matter of willingness to progress—to progress in a way that best servesthe human condition, in every aspect. erefore, “worthy” is not the word, “willingness”is.Mr. Palmore’s e-mail address is: justinpalmore@gmail.com.The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong> 33

Web site photography contestApril 2011—Ajai SambasivanAn elderly man carrying his grandson on his back through a market in Xian, China.e child’s expression captured my attention for many minutes that day, andcontinues to draw me in months later.Mr. Sambasivan’s e-mail address is: ajaisambasivan@gmail.com.34 The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong>

EndingsAreBeginningsToday I saw my final patient.Fifty years ago I saw my first.What did I feel? Triumph?Sorrow? Emptiness?Only this: One door closes,one door opens.Endings are beginnings.I begin again:A whole generation left to live,failure ruled out by definition,all possibilities are open,nothing more to prove.I get in my car and drive home.Rain is starting to fall.Today I saw my final patient.My dog welcomes me just the same.Eric Pfeiffer, MDDr. Pfeiffer (AΩA, Washington University in St. Louis, ) is a member of the editorial board of The Pharos. His address is: W. Hawthorne Road, Tampa,The Florida Pharos/Spring . E-mail: epfeiffe@health.usf.edu.<strong>2010</strong> 1Illustration by Erica Aitken

When I gets bigand my mama gets little,I’m gonna put herin that car seatso tightshe can’t moveFrom Ladies in Waiting by Alan Blum, MDDr. Alan Blum (A A, Emory University, ) is the Gerald Leon Wallace MD Endowed Chair in Family Medicine at the University of Alabama. He has captured thousandsof patients’ stories in notes and drawings. This sketch is from his self-published collection, Ladies in Waiting, which is available by writing to Dr. Blum at:Pinehurst Drive, Tuscaloosa, Alabama - . E-mail: ablum@cchs.ua.edu36 The Pharos/Spring <strong>2010</strong>

Health policyThe editors invite original articles and letters to theeditor for the Health Policy section, length 1500 wordsor fewer for articles, 250 words or fewer for letters.Please send your essays toinfo@alphaomegaalpha.org or to our regular mailingaddress: 525 Middlefield Road, Suite 130, Menlo Park,CA 94025. E-mail submissions preferred. All essaysare subject to review and editing by the editorialboard of The Pharos.The inadequacy of legislativeprocedures and the infirmity of physicianorganizationsDan F. Kopen, MDThe author (AΩA, Pennsylvania State University, 2000)practices general surgery in Forty Fort, Pennsylvania.The United States has just commenced another ina century-long sporadic series of national healthcare initiatives with passage of the 2009 Senate Billincluded in H.R. 4872, The Health Care and EducationAffordability Reconciliation Act of <strong>2010</strong>. This legislation representsthe product of a highly turbulent politicized processdriven by special interests. It is both expansive and expensiveand will result in increased governmental and special interestcontrol over approximately seventeen percent of our GDP at acost of nearly a trillion dollars.For the people of our nation the results will be mixed.The bill consists of well over two thousand pages of legislativelanguage containing hundreds of line item issues addressingan impressive array of health and education related concerns.Some mandates will take effect immediately, others intermittentlyover the next several years extending through 2018.Presently no one can accurately predict the ultimate outcomeof this reform effort, but there are two critical yet-to-beaddressedissues that bear directly upon the likelihood thatincreased government oversight will be successful in improvingaccess to quality care for the public.Legislative procedural inadequacyWhile difficult for many in Washington toopenly admit, it has become increasinglyapparent that our national political processesare not up to the task of effectivelydealing with the complexrealities presented across our nation’s health care landscape.Legislation driven by special interests is not capable of advocatingfor the overarching and ethically proper goal ofuniversal access to quality care for our nation’s inhabitants.What has emerged is a mishmash of legislative resolutionstargeted at individual concerns. While almost all of the issuesare legitimate, each section has been drafted againsta backdrop of special interest agendas. The result is thatmany persons will gain access to care, others will see accessmore difficult to maintain or attain, and many will remainwithout access. The actual quality of the care accessed atthe provider- patient interface has in large part been disregarded.Financial considerations have dominated the legislativeproduct. Quality of care issues have been relegated tosecondary status.The more complex the issues addressed by our politicalmachinery, the greater the opportunities for the agendasof special interests to trump the public good. Our politicalprocesses are inadequate in advocating for the public goodwhen asked to effectively address the complexities of ourhealth care economy. The emergence of calls for revision andrepeal represent a predictable consequence of the proceduralprocesses embraced by our political leaders in forging the legislativeproduct. In the long run, major change in our politicalmachinery will be a necessary element of effective advocacyfor universal access to quality care. This will include replacingthe business-as- usual deal- making by special interests, typicallyconducted behind closed doors, with open and transparentdrafting of legislation guided by those who possessan understanding of the broad spectrum of issues that needto be addressed. The leaders of our nation’s academic healthThe Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong> 37

Health policycenters must be involved to effectively address the need forreform in the public interest.Physician organizational infirmityMore participation by physicians is the second critical issueupon which ultimate success of health care reform depends.By education, training, experience, and professional missionour nation’s physicians and physician associations representthe special interest that is best positioned to advocate forpublic access to quality care. Sadly, this cohort was neitherafforded a seat at the table of reform, nor did it actively seeksuch a role. Indirect participation both as testifiers beforecommittees and letter writers to those in positions of politicalleadership was not effective in realizing the goals advocatedby physicians throughout the reform process leading up to theenacted legislative product.The influence of our nation’s physicians and the manygeneral and specialty societies has been stifled as drivers ofhealth care policy over the past half century. Because of themassive infusion of taxpayer dollars and increasing influenceof state and federal governments generated by the Medicareand Medicaid programs introduced in 1965, potent specialinterests now dominate control of the national health careagenda.In 1998 the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula wasintroduced to further control the reimbursement of physiciansfor services provided. As a result of the gradual increaseto the currently proposed draconian twenty-one percentacross-the-board cut in physician Medicare reimbursements,physicians have been further silenced by a top-down selfimposedpolicy of reticence regarding health care issues.Private payers use the Medicare reimbursement schedulesas a base to determine how much they will pay for physicianservices. From the solo practitioner to the largest academichealth centers, leaders of physicians and physician societieshave become supplicants in health care discussions. The hugefinancial axe wielded by Congress threatens physicians whowould otherwise openly and outspokenly advocate for thepublic good.The powers, both governmental and special interest, thatcontrol these purse strings are not going to permanentlyloosen the manacles that bind physicians in servitude to theagendas of special interests. The increasingly burdensomeoverlay of financial considerations has decreased the influenceof physicians, extending from bedside care of individualpatients to national legislative agendas. The result is that thespecial interest best positioned to advocate for universal accessto quality care has been muted.ConclusionIf we as a nation are to achieve meaningful and effectivehealth care reform, we must overhaul legislative proceduralmachinery and increase the ability of physicians to advocate toprovide better access to quality care. Special interests have fortoo long trumped the common good. Absent the willingnessto confront these two issues, the current legislative attempt toreform the health care landscape will be marginally effectiveat best, and will result in unintended adverse consequences.We remain a nation of tremendous potential and a professionwith a great mission of service to the public good. If wewillingly commit to an open- minded and vigorous approachto these two issues, we can successfully achieve better healthcare for our nation.Received 2/22/10, accepted 3/22/10.The author’s address is190 Welles StreetForty Fort, Pennsylvania 18704E-mail: qm2c6sigma@aol.comDirect-to-consumer advertisingFrancis J. Haddy, MD, PhDThe author is a member of the Mayo Graduate Faculty,Department of Physiology and Biomedical Engineering,Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minnesota.Most of us in the United States are familiar withdirect-to- consumer advertising (DTCA), in whichpharmaceutical firms encourage patients to asktheir doctors to write a prescription for their brands of drugs.This is accomplished by repeated enthusiastic television messagesbeamed directly into the living rooms of consumers. Thetechnique is effective. Prescription drug sales grew sixty-eightpercent from 1994 to 2004, 1 even though the U.S. populationgrew only twelve percent in that time. Similar growth has beenoccurring since 1985, when the Food and Drug Administration(FDA) relaxed DTCA regulations. 2 While only the UnitedStates and New Zealand allow DTCA now, it is possible thatthe practice will spread to Canada and European nations. 3,4The practice is harmful in several ways. Opponents of itargue that the ads mislead consumers and prompt requestsfor products that are not needed and are more expensive than38 The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong>

equally effective drugs or nonpharmacologic treatment. Manyphysicians are opposed to DTCA because they feel it leads toinappropriate use of expensive brand name drugs. 1,5 In onestudy, seventy-one percent of physicians reported inappropriatepressure from patients to prescribe unneeded drugs.Physicians should not be influenced by patient pressureto prescribe certain drugs, but in the real world they clearlyare. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention has notedthat “tens of millions” of antibiotics are prescribed annuallyfor viral infections, 5 and that physicians cite patient demandas one of the primary reasons. 5 Hope motivates sick people tobelieve that there is a “pill for every ill” and to overlook potentialside effects or increases in bacterial resistance. CertainlyDTCA has contributed to growth of prescription drug use andconsequently to costs and side effects. 6We need to reconsider the distinction between selling soapor other consumer products and selling prescription drugs. 5Poor judgment among soap brands may have few health consequences.The influence of DTCA on drug preferences is amuch more substantial concern.The enforcement of current and future laws rests with theFDA. At present, FDA regulatory action typically occurs longafter an ad has begun airing on television. This should beremedied. DTCA is not in the best interest of physicians andpatients. We should return to the regulations in force prior to1985. Organized medicine and the public should make theirfeelings known with resolutions from groups and individualsto the FDA and the Congress.Received 1/4/10, accepted 3/23/10.References1. Law MR, Soumerai SB, Adams AS, Majumdar SR. Costs andconsequences of direct-to-consumer advertising for clopidogrel inMedicaid. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169: 1969–74.2. Food and Drug Administration. Direct-to-consumer advertisingof prescription drugs: withdrawal of moratorium. FederalRegister 1985 Sept 9; 50: 36677–78.3. Cassels A. Canada may be forced to allow direct to consumeradvertising. BMJ 2006; 332: 1469.4. Meek C. Europe reconsidering DTCA. CMAJ 2007; 176: 1405.5. Frosch DL, Krueger FM, Hornick RC, Cronholm PF, Borg FK.Creating demand for prescription drugs: a content analysis of televisiondirect-to-consumer advertising. Ann Fam Med 2007; 5: 6–13.6. Kessler DA, Rose JL, Temple RJ, Schapiro R, Griffin JP. Therapeutic-classwars—drug promotion in a competitive marketplace.N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 1350–53.The author’s address is:211 Second Street NW #1607Rochester, Minnesota 55901-2896E-mail: tbhaddy@aol.comOde to aJaundiced EyeClinicians and Pathologists are most benevolent,At a clinical pathologic conference are at timesmalevolent,The conference Pathologist practiced one-upsmanshipThrough the medium of unilateral jaundiced-eyemanship.The Clinician diagnosed the cause of a single yellow eye,The knowledgeable Clinician had an eye for a yellow eye.Paul L. Wolf, MDDr. Wolf is professor of Clinical Pathology at the University of California SanDiego Medical Center. His address is: Department of Pathology, University ofCalifornia Medical Center, West Arbor Drive, San Diego, California .E-mail: paul.wolf@med.va.gov.The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong> 39

Reviews and reflectionsDavid A. Bennahum, MD, and Jack Coulehan, MD, Book Review EditorsA Second Opinion: RescuingAmerica’s Health Care: A Planfor Universal Coverage ServingPatients Over ProfitArnold S. RelmanPublicAffairs Books, New York, 2007Reviewed by Robert A. Chase, MD(AΩA, Yale University, 1947)Doctor Arnold Relman has publishedextensively on the healthcare crisis in the United States. Togetherwith Marcia Angell, he is credited withlucid, insightful, and reasoned approachesto the present crisis. This reviewjoins many others that complimentRelman for this excellent summary ofthe ever- changing U.S. health care systemover the last six decades. He haspacked his review of the system withpersonal experiences from his own careerin health care as clinician, researchinvestigator, teacher, author, and critic.In general, his expressed feelings aboutthe sequential changes in health careorganization over his sixty yearsof experience match my own.Disturbed by the commercializationof medicine, Dr.Relman points out that,as an industry, profitdominates patientcare needs and physicians have becometradespeople, which has resulted in theloss of their professional status. Markettheory has prevailed in the economicdefinition of “managed care.” The adventof Medicare and Medicaid has createda major incentive for developmentof private and industrial-based healthinsurance. The positive and negative effectsare clearly expressed by the authorwith staunch personal determination.Courts have applied antitrust laws tomedicine, making health care organizationsvery cautious about setting ethicalstandards. Physicians themselves havebecome investors in and purveyors ofproducts and services for profit underthe influence of manufacturers of suchproducts and pharmaceuticals. All ofthis with little or no attention to thesocial and health effects of this growthof investor influence and profit orientation.These changes and more representthe gestation for the birth of today’s“Medical Industrial Complex.” Relmanpoints out that such commercializationhas not occurred in nations with universalpublicly- supported health insurancesystems. He expresses the opinionthat our business- oriented health caremodel is substantially responsible forits current high cost, more than fifteenpercent of the gross national product.His opinion is that health care improvementhas not been worth the inflatedcost. Inequity of access to care is onemore result of medical commercialism.This appears to be a clear basis for thecurrent revolt of those responsible forpayments for health care, be it industryor individual.In this book, Relman proposes radicalmajor reform as the best solution tothe multiplicity of problems in our currenthealth care crisis. He agrees withthe notion of a single- payer national insurancesystem, but feels that to controlcosts while simultaneously improvingthe quality of care there must be reformof the way physicians are organized inpractice. Properly organized reformscould solve many of the present problemsat no increase or even a decreasein the overall cost of health care. Theextra cost of management and shareholderprofits in commercialized medicineshould be going to care of patients.To achieve this, Relman favors prepaidmedical groups with physicians on salary.Salaries could be supplementedwith reasonable bonuses defined bymultispecialty group management. Withsuch a system, the enormous overheadcost of billing and possible billing fraudwould be eliminated.In this period of serious discussionof U.S. health care change it is of greatvalue to have a crisp, detailed evaluationfrom one of the nation’s healthcare experts. Physicians should involvethemselves in the ongoing debate andthus they should read and understandthis excellent Second Opinion.Dr. Chase is the Emile Holman Professorof Surgery/Anatomy Emeritus at StanfordUniversity School of Medicine, and a memberof the editorial board of The Pharos.His address is:Stanford University School of MedicineAnatomy, CCSR Building, Room 135269 Campus DriveStanford, California 94305-5140E-mail: rchase6880@aol.comThe Language of Life: DNA andthe Revolution in PersonalizedMedicineFrancis S. CollinsHarperCollins, New York, <strong>2010</strong>.Reviewed by Thoru Pederson, PhDFrancis Collins was an icon in pediatricmedicine, notably in the treatmentof cystic fibrosis, long before his40 The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong>

name became known in the genomicsfield. Getting big things done requiresexceptional people and Collins was amajor force in getting something verybig done, the Human Genome project—not as a scientist making a key breakthroughà la Watson and Crick, but asa passionate physician- scientist withthe position and innate gifts to rise as aneeded leader. He and a great opportunityfound each other, in time and space.This book is aimed at two audiencesat the same time: on the one hand aneducated lay readership, especially patientsand their families, and on theother those who work on genes, geneproducts, and cells. The author chartsout the territory with a clear didacticstyle. To engage both audiences simultaneouslyis not easy, but is somethingthat true masters of their subjects cando (indeed, this is as good a definitionof a master as I know). One of the mostriveting impressions that comes acrossis that Collins has never stopped being aphysician, but has also not ever stoppedbeing a basic scientist. He clearly loveshis patients first, but the lab is a veryclose second.Collins covers the basics of geneexpression and genome sequencing,then moves into the various aspects ofhow genomics can be used to detect oranticipate disease. He addresses thesechallenging frontiers as they apply tocancer in a particularly insightful andcircumspect way. In contrast, in thearena of single gene-based pathology heuses his expertise in cystic fibrosis as acase in point: the number of mutationsis large and carrier detection is generallysuccessful but misses some.His exposition of the gene therapyfield is expert and wise, as expected. It isnow twenty-six years since a four-yearoldgirl, Ashanti DeSilva, had her whiteblood cells transfected ex vivo with thegene for adenosine deaminase at theU.S. National Institutes of Health—sheis prospering today, proving that it canbe done. The subsequent era, involvingretroviral insertion of hopefullycorrective genes directly into patients,has been checkered by less impressiveoutcomes and tragedy, and Collins isobjective in weighing these against thepromise of success, now at hand giventhe safer adeno- associated viral vectorsand some impressive clinical achievementsrecently.A particularly poignant vignetteCollins presents concerns progeria, apremature aging syndrome caused bymutations in a protein called lamin Athat surrounds the nuclear genome.The discovery by Collins’s lab of thegene underlying one form of progeriais a spectacular example of how humangenetics and basic cell biology cancome together in wonderfully catalyticways. Within weeks after this discovery,Collins and his team became aware of arecently developed foundation of incisivework on this protein by cell biologistswho had not been thinking aboutdisease but were just trying to figureout how the cell nucleus is built. This isan especially engaging part of the book,providing a case for the support of bothbasic and clinical research, and the perilof ever steering funds into either at theexpense of the other. In closing sectionsCollins looks forward to the time whenat least single gene-based diseases willbe recognized and genetically definedat the first onset of symptoms, or evenearlier in carrier detection. As a majortheme of the book, he develops a strongcase for the advent of “personalized genomics,”when very subtle zephyrs lurkingin a patient’s DNA will be part of thediagnostic tree and treatment.In its clarity of exposition, sobriety ofpromise, and engaging vision, this is abook that should be read by every physicianwhose practice interfaces with thegenetics of disease, or whose broaderintellectual fabric seeks to gain a senseof what is to come.Interviewing a hopeful MD/PhD applicantto my medical school recently,I mentioned to her that she might, asa third-year student on the wards, seea chart with the entire genome of thepatient. She replied, “I think that is areal possibility.” I wrote down “Good answer.”Then I added to my notes “Sendher a copy of Francis Collins’s bookwhen it comes out in January.”Dr. Pederson is the Vitold Arnett Professorin the Department of Biochemistry andMolecular Pharmacology at the Universityof Massachusetts Medical School inWorcester, Massachusetts. His address is:University of Massachusetts MedicalSchoolDepartment of Biochemistry andMolecular Pharmacology377 Plantation StreetWorcester, Massachusetts 01605E-mail: thoru.pederson@umassmed.eduOne Breath Apart: FacingDissectionSandra L. BertmanBaywood Publishing Company,Amityville, New York, 2009Reviewed by Robert A. Chase, MD(AΩA, Yale University, 1947)In this book, Sandra Bertman showsand discusses the changes in teachingand learning of human anatomy byhuman cadaver dissection. She commentson the history of human dissection,from pre-Roman, medieval, andRenaissance, to modern times, includingits benefits to great artists as well asmedical practitioners. The remarkablechanges in the teaching and learning ofhuman anatomy in the last half centuryare described in detail.The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong> 41

Reviews and reflectionsPsychological preparation of studentsanticipating laboratory dissectionof a dead human being has becomea standard for anatomy departmentsaround the world. Support and opendiscussion of the effect upon studentsduring the laboratory experience is nowan important part of the process ofpreparing students to learn to care forliving patients. During the entire periodof concentrated study of human anatomy,psychological support, includingdiscussion among students and facultycontinues. The whole process has animportant dimension beyond learninggross human structure, anatomical relationships,and the language of medicine.It introduces students to an understandingof death and dying, as well as anunderstanding of professional relationshipswith colleagues in medicine.Through letters from donors andtheir families, students understand thedesire of donors to help them becometruly competent and caring professionals.This book outlines and effectivelydisplays one technique for introductionof students to human dissection,initiated by a thoughtful faculty at theUniversity of Massachusetts School ofMedicine at Worcester. Appropriately,the author has dedicated the book toone such teaching innovator, Dr. SandyMarks, who before his untimely deathwas well known to the worldwide communityof teaching anatomists.At the University of Massachusetts,students are invited to draw on a blanksheet of paper an image that depictsthe student’s own feeling as he or shefaced the prospect of dissecting a deadhuman being. They were also to writea short explanation of the feelings thathelped them to generate the image.Selections from this thirty-year traditionare illustrated in One Breath Apart,including both the images and explanationsshowing the wide range of feelingsof students anticipating the openingand exporing of a dead human being,a process that has been referred to asa “rite of passage” into the fraternity ofmedicine. The drawings are interestingand often revealing, and many of theexplanations are poetic and touching.There are bits of humor, evidence ofconcern and fear, expressions of gratitude,thoughts of understanding of therelevance to patient care, and the developmentof a relationship to each student’sown cadaver. The juxtapositionof religious beliefs and emotions relatedto dissection come through in several ofthe examples shown.During the period of dissection itself,students describe the variety of emotionsthey feel when first uncoveringthe face or observing fingernail polish,details that remind the dissectors thatthey are working with someone whowas human like themselves.At the end of the anatomy course atthe University of Massachusetts, andnow in many of the world’s medicalschools, a memorial service is held tohonor and express thanks to the bodydonors. Student- produced music, poems,and thoughtful reflections are presentedto a wide audience includingstudents, donor families, and the publicat large. Letters of appreciation fromattendees, including donor families, arequoted in the book.As students reach graduation yearslater, they regularly receive a note fromthe Anatomy faculty, including some ofthe drawings and comments made earlier,to congratulate the graduates and towish them well.This book will appeal to studentsabout to embark on the study of medicineor any medically- related disciplinein which human dissection is a requisiteelement and opportunity.Dr. Chase is the Emile Holman Professorof Surgery/Anatomy Emeritus at StanfordUniversity School of Medicine, and a memberof the editorial board of The Pharos.His address is:Stanford University School of MedicineAnatomy, CCSR Building, Room 135269 Campus DriveStanford, California 94305-5140E-mail: rchase6880@aol.comDoctors in Fiction: Lessonsfrom LiteratureBorys Surawicz and Beverly JacobsonRadcliffe Publishing, New York, 2009Reviewed by Jack Coulehan, MD(AΩA, University of Pittsburgh, 1969)Doctors in Fiction: Lessons fromLiterature is a fascinating collectionof short essays about fictional physiciansby Borys Surawicz and BeverlyJohnson. The authors, one a cardiologistand the other a freelance writer,discuss a wide variety of doctors drawnfrom novels, short stories, and drama,and representing a fictional time framefrom the late twelfth century to the earlytwenty-first. In each chapter the authorspresent one or more of these physiciansin context, briefly introducing the work,the writer, and a précis of the socialcontext.Surawicz and Johnson intend thisbook to be read by physicians, medicalstudents, and other health professionals42 The Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong>

who don’t have “much time to read fiction,except perhaps on vacation.” pix Byintroducing literary works that explorethe great themes of medicine, Doctorsin Fiction may “hook” these individualsinto further reading. The authors begineach chapter by listing several themessuggested by the works and characterscovered in that chapter and, in manycases, discuss these themes as they relateto contemporary medical practice,thus making the book a potential adjunctto teaching literature in medicine.As a high school student, the firstfictional doctors I encountered wereAndrew Manson in A. J. Cronin’sThe Citadel and Martin Arrowsmithin Sinclair Lewis’ eponymous novel.These two were ideal role models foran aspiring physician in that they committedthemselves to excellence in patientcare and research. Sure enough,they appear prominently in Doctors inFiction as examples of highly ethicalphysicians; other such examples of truly“good” doctors include Tertius Lydgate(Middlemarch), Bernard Rieux (ThePlague), and Thomas Stockman (TheEnemy of the People).At the other end of the spectrum arefailures and burnt-out cases, like psychiatristDick Diver, the protagonist in F.Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night, whosuccumbs to weakness and alcoholism,and the debauched abortionist Dr. HarryWilbourne in The Wild Palms by WilliamFaulkner. Some of the best examples of“fallen” doctors appear in the two chaptersthat deal with characters in AntonChekhov’s stories and plays. Chekhov, apracticing physician himself, had an insidetrack in understanding the triumphs andtragedies of the medical experience.One chapter focuses on Dr. AndreiRagin, the dispirited medical director ofChekhov’s “Ward #6.” Ragin has withdrawnfrom his provincial hospital andsits at home all day reading and drinkingbeer, while his assistant takes care ofthe patients. Ragin justifies his anomiebecause he believes the hospital systemis so corrupt that any effort on his partwould be futile. During an unexpectedvisit to the psych ward, Ragin becomesfascinated with an articulate patientwho challenges his self- justification byclaiming that Ragin has never suffered,so he can’t empathize with his patients’suffering. Ragin becomes obsessed withgaining the ability to suffer, an obsessionthat eventually leads to his ownincarceration on Ward #6. Surawiczand Jacobson characterize this doctoras an essentially good man, but I tend toview him as a nonreflective, narcissisticperson who never developed a matureprofessional identity. In either case hisstory is depressing.The authors also touch briefly on severalother doctors in Chekhov’s fiction:Dymov, an idealistic physician who diesas a result of the diphtheria he contractedfrom a patient (“The Grasshopper”);Korolyov, a young doctor who developsan empathic bond with a woman whosuffers from chronic anxiety (“A Doctor’sVisit”); Startsev, a practitioner who growsto love money more than his patients’welfare (“Ionitch”); and Astrov, the dedicatedproto- environmentalist physicianin Uncle Vanya.Two of the most striking figures inDoctors in Fiction arise from contemporarypopular novels, although theirfictional lives take place in an earliertime. Dr. Adelia Aguilar, the protagonistof several mysteries by Ariana Franklin,serves as a forensic consultant to KingHenry II of England in the 1170s. Anorphan, Adelia was raised by a Jewishphysician from Salerno, where she latergraduated from that city’s cosmopolitanmedical school. In the first book,Mistress of the Art of Death, Adeliaresponds to Henry’s call for a doctor toinvestigate a series of child murders inCambridge. She subsequently settles inEngland and continues to solve murdersby using her medical and forensic skills.While the figure of a female physicianin the twelfth century seems unhistorical,Surawicz and Jacobson explainthat, in fact, women did study medicineat the ethnically diverse and tolerantUniversity of Salerno.The other striking character is Dr.Stephen Maturin, well known to millionsof readers as the particular friendof Captain Jack Aubrey in PatrickO’Brian’s series of novels about theBritish navy during the NapoleonicWars. Maturin is a famous physicianand naturalist, as well as an undercoverintelligence agent. He is small, dark,and secretive; Aubrey is large, jolly, andhearty. O’Brian’s novels explore thesetwo complex characters and their yearsof friendship in the context of a series ofgreat adventure stories. In almost everynovel, Maturin demonstrates his medicalskills. He often shows his gift for surgeryas well, as when he courageouslyperforms a cystotomy or trephines asailor’s skull on the ship’s deck.Adelia Aguilar and Stephen Maturinare compelling characters from contemporarypopular fiction, but Surawicz andJacobson also draw their doctors fromrecent works of a more literary bent,like the novels of Robertson Davies, IanMcEwan, and A. B. Yehoshua. All inall, Doctors in Fiction reacquainted mewith some old favorites and introducedme to several works with which I wasunfamiliar. The book is by no meansa comprehensive survey of physiciansin literature—witness the absence ofMadame Bovary, The Magic Mountainand, of course, Sherlock Holmes’ friend,Dr. Watson—nor is it a deep analysis ofthe works included. Rather, Doctors inFiction is just what the authors intendedit to be: a generous selection of physiciansthat illustrates “how the medicalprofession is viewed by prominent writersand how their writings may affectthe judgment of the medical professionby readers.” pixDr. Coulehan is a Book Review Editor forThe Pharos and a member of the journal’seditorial board. His address is:Center for Medical Humanities,Compassionate Care, and BioethicsHSC L3-080State University of New York at StonyBrookStony Brook, New York 11794-8335E-mail: jcoulehan@notes.cc.sunysb.eduThe Pharos/Summer <strong>2010</strong> 43