12.07.2015

•

Views

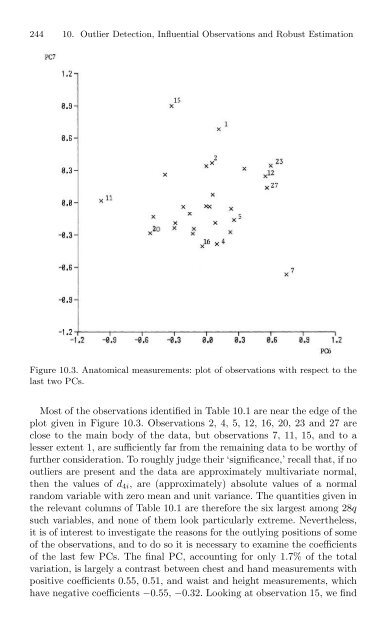

10.1. Detection of Outliers Using Principal Components 243Table 10.1. Anatomical measurements: values of d 2 1i, d 2 2i, d 4i for the most extremeobservations.Number of PCs used, qq =1 q =2d 2 1i Obs. No. d 2 1i Obs. No. d 2 2i Obs. No. d 4i Obs. No.0.81 15 1.00 7 7.71 15 2.64 150.47 1 0.96 11 7.69 7 2.59 110.44 7 0.91 15 6.70 11 2.01 10.16 16 0.48 1 4.11 1 1.97 70.15 4 0.48 23 3.52 23 1.58 230.14 2 0.36 12 2.62 12 1.49 27q =3d 2 1i Obs. No. d 2 2i Obs. No. d 4i Obs. No.1.55 20 9.03 20 2.64 151.37 5 7.82 15 2.59 51.06 11 7.70 5 2.59 111.00 7 7.69 7 2.53 200.96 1 7.23 11 2.01 10.93 15 6.71 1 1.97 7observations on each statistic, where the number of PCs included, q, is1,2or 3. The observations that correspond to the most extreme values of d 2 1i ,d 2 2i and d 4i are identified in Table 10.1, and also on Figure 10.3.Note that when q = 1 the observations have the same ordering for allthree statistics, so only the values of d 2 1i are given in Table 10.1. When qis increased to 2 or 3, the six most extreme observations are the same (ina slightly different order) for both d 2 1i and d2 2i . With the exception of thesixth most extreme observation for q = 2, the same observations are alsoidentified by d 4i . Although the sets of the six most extreme observationsare virtually the same for d 2 1i , d2 2i and d 4i, there are some differences inordering. The most notable example is observation 15 which, for q =3,ismost extreme for d 4i but only sixth most extreme for d 2 1i .Observations 1, 7 and 15 are extreme on all seven statistics given in Table10.1, due to large contributions from the final PC alone for observation15, the last two PCs for observation 7, and the fifth and seventh PCs forobservation 1. Observations 11 and 20, which are not extreme for the finalPC, appear in the columns for q = 2 and 3 because of extreme behaviouron the sixth PC for observation 11, and on both the fifth and sixth PCsfor observation 20. Observation 16, which was discussed earlier as a clearoutlier on the second PC, appears in the list for q = 1, but is not notablyextreme for any of the last three PCs.

244 10. Outlier Detection, Influential Observations and Robust EstimationFigure 10.3. Anatomical measurements: plot of observations with respect to thelast two PCs.Most of the observations identified in Table 10.1 are near the edge of theplot given in Figure 10.3. Observations 2, 4, 5, 12, 16, 20, 23 and 27 areclose to the main body of the data, but observations 7, 11, 15, and to alesser extent 1, are sufficiently far from the remaining data to be worthy offurther consideration. To roughly judge their ‘significance,’ recall that, if nooutliers are present and the data are approximately multivariate normal,then the values of d 4i , are (approximately) absolute values of a normalrandom variable with zero mean and unit variance. The quantities given inthe relevant columns of Table 10.1 are therefore the six largest among 28qsuch variables, and none of them look particularly extreme. Nevertheless,it is of interest to investigate the reasons for the outlying positions of someof the observations, and to do so it is necessary to examine the coefficientsof the last few PCs. The final PC, accounting for only 1.7% of the totalvariation, is largely a contrast between chest and hand measurements withpositive coefficients 0.55, 0.51, and waist and height measurements, whichhave negative coefficients −0.55, −0.32. Looking at observation 15, we find

-

Page 1:

Principal ComponentAnalysis,Second

-

Page 7 and 8:

viPreface to the Second Editionerty

-

Page 9 and 10:

viiiPreface to the Second EditionA

-

Page 11 and 12:

xPreface to the First Editionand in

-

Page 13 and 14:

xiiPreface to the First EditionIn m

-

Page 15 and 16:

This page intentionally left blank

-

Page 17 and 18:

xviAcknowledgmentsthese institution

-

Page 19 and 20:

xviiiContents3.4.1 Example ........

-

Page 21 and 22:

xxContents10 Outlier Detection, Inf

-

Page 23 and 24:

This page intentionally left blank

-

Page 25 and 26:

xxivList of Figures5.2 Artistic qua

-

Page 27 and 28:

This page intentionally left blank

-

Page 29 and 30:

xxviiiList of Tables6.1 First six e

-

Page 31 and 32:

This page intentionally left blank

-

Page 33 and 34:

2 1. IntroductionFigure 1.1. Plot o

-

Page 35:

4 1. IntroductionFigure 1.3. Studen

-

Page 38 and 39:

1.2. A Brief History of Principal C

-

Page 40 and 41:

1.2. A Brief History of Principal C

-

Page 42 and 43:

2.1. Optimal Algebraic Properties o

-

Page 44 and 45:

2.1. Optimal Algebraic Properties o

-

Page 46 and 47:

2.1. Optimal Algebraic Properties o

-

Page 48 and 49:

2.1. Optimal Algebraic Properties o

-

Page 50 and 51:

2.2. Geometric Properties of Popula

-

Page 52 and 53:

2.3. Principal Components Using a C

-

Page 54 and 55:

2.3. Principal Components Using a C

-

Page 56 and 57:

2.3. Principal Components Using a C

-

Page 58 and 59:

2.4. Principal Components with Equa

-

Page 60 and 61:

3Mathematical and StatisticalProper

-

Page 62 and 63:

where3.1. Optimal Algebraic Propert

-

Page 64 and 65:

3.2. Geometric Properties of Sample

-

Page 66 and 67:

3.2. Geometric Properties of Sample

-

Page 68 and 69:

3.2. Geometric Properties of Sample

-

Page 70 and 71:

3.3. Covariance and Correlation Mat

-

Page 72 and 73:

3.3. Covariance and Correlation Mat

-

Page 74 and 75:

3.4. Principal Components with Equa

-

Page 76 and 77:

show that X = ULA ′ .⎡ULA ′ =

-

Page 78 and 79:

3.6. Probability Distributions for

-

Page 80 and 81:

3.7. Inference Based on Sample Prin

-

Page 82 and 83:

3.7.2 Interval Estimation3.7. Infer

-

Page 84 and 85:

3.7. Inference Based on Sample Prin

-

Page 86 and 87:

3.7. Inference Based on Sample Prin

-

Page 88 and 89:

3.8. Patterned Covariance and Corre

-

Page 90 and 91:

3.9. Models for Principal Component

-

Page 92 and 93:

3.9. Models for Principal Component

-

Page 94 and 95:

4Principal Components as a SmallNum

-

Page 96 and 97:

4.1. Anatomical Measurements 65Tabl

-

Page 98 and 99:

4.1. Anatomical Measurements 67spac

-

Page 100 and 101:

4.2. The Elderly at Home 69Table 4.

-

Page 102 and 103:

4.3. Spatial and Temporal Variation

-

Page 104 and 105:

4.3. Spatial and Temporal Variation

-

Page 106 and 107:

4.4. Properties of Chemical Compoun

-

Page 108 and 109:

4.5. Stock Market Prices 77Table 4.

-

Page 110 and 111:

5. Graphical Representation of Data

-

Page 112 and 113:

Anatomical Measurements5.1. Plottin

-

Page 114 and 115:

5.1. Plotting Two or Three Principa

-

Page 116 and 117:

5.2. Principal Coordinate Analysis

-

Page 118 and 119:

5.2. Principal Coordinate Analysis

-

Page 120 and 121:

5.2. Principal Coordinate Analysis

-

Page 122 and 123:

5.3. Biplots 91columns, L is an (r

-

Page 124 and 125:

5.3. Biplots 93ButandSubstituting i

-

Page 126 and 127:

5.3. Biplots 95The vector gi ∗ co

-

Page 128 and 129:

5.3. Biplots 97Figure 5.3. Biplot u

-

Page 130 and 131:

5.3. Biplots 99Table 5.2. First two

-

Page 132 and 133:

5.3. Biplots 101Figure 5.5. Biplot

-

Page 134 and 135:

5.4. Correspondence Analysis 103of

-

Page 136 and 137:

5.4. Correspondence Analysis 105Fig

-

Page 138 and 139:

5.6. Displaying Intrinsically High-

-

Page 140 and 141:

5.6. Displaying Intrinsically High-

-

Page 142 and 143:

6Choosing a Subset of PrincipalComp

-

Page 144 and 145:

6.1. How Many Principal Components?

-

Page 146 and 147:

6.1. How Many Principal Components?

-

Page 148 and 149:

6.1. How Many Principal Components?

-

Page 150 and 151:

6.1. How Many Principal Components?

-

Page 152 and 153:

6.1. How Many Principal Components?

-

Page 154 and 155:

6.1. How Many Principal Components?

-

Page 156 and 157:

6.1. How Many Principal Components?

-

Page 158 and 159:

6.1. How Many Principal Components?

-

Page 160 and 161:

6.1. How Many Principal Components?

-

Page 162 and 163:

6.1. How Many Principal Components?

-

Page 164 and 165:

6.2. Choosing m, the Number of Comp

-

Page 166 and 167:

6.2. Choosing m, the Number of Comp

-

Page 168 and 169:

6.3. Selecting a Subset of Variable

-

Page 170 and 171:

6.3. Selecting a Subset of Variable

-

Page 172 and 173:

6.3. Selecting a Subset of Variable

-

Page 174 and 175:

6.3. Selecting a Subset of Variable

-

Page 176 and 177:

6.4. Examples Illustrating Variable

-

Page 178 and 179:

6.4. Examples Illustrating Variable

-

Page 180 and 181:

6.4. Examples Illustrating Variable

-

Page 182 and 183:

7.1. Models for Factor Analysis 151

-

Page 184 and 185:

7.2. Estimation of the Factor Model

-

Page 186 and 187:

7.2. Estimation of the Factor Model

-

Page 188 and 189:

7.2. Estimation of the Factor Model

-

Page 190 and 191:

7.3. Comparisons Between Factor and

-

Page 192 and 193:

7.4. An Example of Factor Analysis

-

Page 194 and 195:

7.4. An Example of Factor Analysis

-

Page 196 and 197:

7.5. Concluding Remarks 165To illus

-

Page 198 and 199:

8Principal Components in Regression

-

Page 200 and 201:

8.1. Principal Component Regression

-

Page 202 and 203:

8.1. Principal Component Regression

-

Page 204 and 205:

8.2. Selecting Components in Princi

-

Page 206 and 207:

8.2. Selecting Components in Princi

-

Page 208 and 209:

8.3. Connections Between PC Regress

-

Page 210 and 211:

8.4. Variations on Principal Compon

-

Page 212 and 213:

8.4. Variations on Principal Compon

-

Page 214 and 215:

8.4. Variations on Principal Compon

-

Page 216 and 217:

8.5. Variable Selection in Regressi

-

Page 218 and 219:

8.5. Variable Selection in Regressi

-

Page 220 and 221:

8.6. Functional and Structural Rela

-

Page 222 and 223:

8.7. Examples of Principal Componen

-

Page 224 and 225:

Table 8.3. Principal component regr

-

Page 226 and 227:

8.7. Examples of Principal Componen

-

Page 228 and 229:

8.7. Examples of Principal Componen

-

Page 230 and 231:

9Principal Components Used withOthe

-

Page 232 and 233:

9.1. Discriminant Analysis 201on th

-

Page 234 and 235:

9.1. Discriminant Analysis 203Figur

-

Page 236 and 237:

9.1. Discriminant Analysis 205Corbi

-

Page 238 and 239:

9.1. Discriminant Analysis 207that

-

Page 240 and 241:

9.1. Discriminant Analysis 209betwe

-

Page 242 and 243:

9.2. Cluster Analysis 211dimensiona

-

Page 244 and 245:

9.2. Cluster Analysis 213Before loo

-

Page 246 and 247:

9.2. Cluster Analysis 215Figure 9.3

-

Page 248 and 249:

9.2. Cluster Analysis 217demographi

-

Page 250 and 251:

9.2. Cluster Analysis 219county clu

-

Page 252 and 253:

9.2. Cluster Analysis 221choosing a

-

Page 254 and 255:

9.3. Canonical Correlation Analysis

-

Page 256 and 257:

9.3. Canonical Correlation Analysis

-

Page 258 and 259:

9.3. Canonical Correlation Analysis

-

Page 260 and 261:

9.3. Canonical Correlation Analysis

-

Page 262 and 263:

9.3. Canonical Correlation Analysis

-

Page 264 and 265:

10.1. Detection of Outliers Using P

-

Page 266 and 267:

10.1. Detection of Outliers Using P

-

Page 268 and 269:

10.1. Detection of Outliers Using P

-

Page 270 and 271:

10.1. Detection of Outliers Using P

-

Page 272 and 273:

10.1. Detection of Outliers Using P

-

Page 276 and 277:

10.1. Detection of Outliers Using P

-

Page 278 and 279:

10.1. Detection of Outliers Using P

-

Page 280 and 281:

10.2. Influential Observations in a

-

Page 282 and 283:

10.2. Influential Observations in a

-

Page 284 and 285:

10.2. Influential Observations in a

-

Page 286 and 287:

10.2. Influential Observations in a

-

Page 288 and 289:

10.2. Influential Observations in a

-

Page 290 and 291:

10.3. Sensitivity and Stability 259

-

Page 292 and 293:

10.3. Sensitivity and Stability 261

-

Page 294 and 295:

10.4. Robust Estimation of Principa

-

Page 296 and 297:

10.4. Robust Estimation of Principa

-

Page 298 and 299:

10.4. Robust Estimation of Principa

-

Page 300 and 301:

11Rotation and Interpretation ofPri

-

Page 302 and 303:

11.1. Rotation of Principal Compone

-

Page 304 and 305:

oot of the corresponding eigenvalue

-

Page 306 and 307:

11.1. Rotation of Principal Compone

-

Page 308 and 309:

11.1. Rotation of Principal Compone

-

Page 310 and 311:

11.2. Alternatives to Rotation 279w

-

Page 312 and 313:

11.2. Alternatives to Rotation 281F

-

Page 314 and 315:

11.2. Alternatives to Rotation 283F

-

Page 316 and 317:

11.2. Alternatives to Rotation 285T

-

Page 318 and 319:

11.2. Alternatives to Rotation 287T

-

Page 320 and 321:

11.2. Alternatives to Rotation 289A

-

Page 322 and 323:

11.2. Alternatives to Rotation 291

-

Page 324 and 325:

11.3. Simplified Approximations to

-

Page 326 and 327:

11.3. Simplified Approximations to

-

Page 328 and 329:

11.4. Physical Interpretation of Pr

-

Page 330 and 331:

12Principal Component Analysis forT

-

Page 332 and 333:

12.1. Introduction 301series is alm

-

Page 334 and 335:

12.2. PCA and Atmospheric Time Seri

-

Page 336 and 337:

12.2. PCA and Atmospheric Time Seri

-

Page 338 and 339:

and a typical row of the matrix is1

-

Page 340 and 341:

12.2. PCA and Atmospheric Time Seri

-

Page 342 and 343:

12.2. PCA and Atmospheric Time Seri

-

Page 344 and 345:

12.2. PCA and Atmospheric Time Seri

-

Page 346 and 347:

12.2. PCA and Atmospheric Time Seri

-

Page 348 and 349:

12.3. Functional PCA 317A key refer

-

Page 350 and 351:

12.3. Functional PCA 319The sample

-

Page 352 and 353:

12.3. Functional PCA 321speed (mete

-

Page 354 and 355:

12.3. Functional PCA 323of the data

-

Page 356 and 357:

12.3. Functional PCA 325subject to

-

Page 358 and 359:

12.3. Functional PCA 327series than

-

Page 360 and 361:

12.4. PCA and Non-Independent Data

-

Page 362 and 363:

12.4. PCA and Non-Independent Data

-

Page 364 and 365:

12.4. PCA and Non-Independent Data

-

Page 366 and 367:

12.4. PCA and Non-Independent Data

-

Page 368 and 369:

12.4. PCA and Non-Independent Data

-

Page 370 and 371:

13.1. Principal Component Analysis

-

Page 372 and 373:

13.1. Principal Component Analysis

-

Page 374 and 375:

13.2. Analysis of Size and Shape 34

-

Page 376 and 377:

13.2. Analysis of Size and Shape 34

-

Page 378 and 379:

13.3. Principal Component Analysis

-

Page 380 and 381:

13.3. Principal Component Analysis

-

Page 382 and 383:

13.4. Principal Component Analysis

-

Page 384 and 385:

13.4. Principal Component Analysis

-

Page 386 and 387:

13.5. Common Principal Components 3

-

Page 388 and 389:

13.5. Common Principal Components 3

-

Page 390 and 391:

13.5. Common Principal Components 3

-

Page 392 and 393:

13.5. Common Principal Components 3

-

Page 394 and 395:

13.6. Principal Component Analysis

-

Page 396 and 397:

13.6. Principal Component Analysis

-

Page 398 and 399:

13.7. PCA in Statistical Process Co

-

Page 400 and 401:

13.8. Some Other Types of Data 369A

-

Page 402 and 403:

13.8. Some Other Types of Data 371d

-

Page 404 and 405:

14Generalizations and Adaptations o

-

Page 406 and 407:

14.1. Non-Linear Extensions of Prin

-

Page 408 and 409:

14.1. Additive Principal Components

-

Page 410 and 411:

14.1. Additive Principal Components

-

Page 412 and 413:

14.1. Additive Principal Components

-

Page 414 and 415:

14.2. Weights, Metrics, Transformat

-

Page 416 and 417:

14.2. Weights, Metrics, Transformat

-

Page 418 and 419:

14.2. Weights, Metrics, Transformat

-

Page 420 and 421:

14.2. Weights, Metrics, Transformat

-

Page 422 and 423:

14.2. Weights, Metrics, Transformat

-

Page 424 and 425:

14.3. PCs in the Presence of Second

-

Page 426 and 427:

14.4. PCA for Non-Normal Distributi

-

Page 428 and 429:

14.5. Three-Mode, Multiway and Mult

-

Page 430 and 431:

14.5. Three-Mode, Multiway and Mult

-

Page 432 and 433:

14.6. Miscellanea 401• Linear App

-

Page 434 and 435:

14.6. Miscellanea 40314.6.3 Regress

-

Page 436 and 437:

14.7. Concluding Remarks 405space o

-

Page 438 and 439:

Appendix AComputation of Principal

-

Page 440 and 441:

A.1. Numerical Calculation of Princ

-

Page 442 and 443:

A.1. Numerical Calculation of Princ

-

Page 444 and 445:

A.1. Numerical Calculation of Princ

-

Page 446 and 447:

ReferencesAguilera, A.M., Gutiérre

-

Page 448 and 449:

References 417Apley, D.W. and Shi,

-

Page 450 and 451:

References 419Benasseni, J. (1986b)

-

Page 452 and 453:

References 421Boik, R.J. (1986). Te

-

Page 454 and 455:

References 423Castro, P.E., Lawton,

-

Page 456 and 457:

References 425Cook, R.D. (1986). As

-

Page 458 and 459:

References 427Dempster, A.P., Laird

-

Page 460 and 461:

References 429Feeney, G.J. and Hest

-

Page 462 and 463:

References 431in Descriptive Multiv

-

Page 464 and 465:

References 433Gunst, R.F. and Mason

-

Page 466 and 467:

References 435Hocking, R.R., Speed,

-

Page 468 and 469:

References 437Jeffers, J.N.R. (1978

-

Page 470 and 471:

References 439Kazi-Aoual, F., Sabat

-

Page 472 and 473:

References 441Krzanowski, W.J. (200

-

Page 474 and 475:

References 443Mann, M.E. and Park,

-

Page 476 and 477:

References 445Monahan, A.H., Tangan

-

Page 478 and 479:

References 447Pack, P., Jolliffe, I

-

Page 480 and 481:

References 449Richman M.B. (1993).

-

Page 482 and 483:

References 451Soofi, E.S. (1988). P

-

Page 484 and 485:

References 453Tenenbaum, J.B., de S

-

Page 486 and 487:

References 455Vong, R., Geladi, P.,

-

Page 488 and 489:

References 457regularities in multi

-

Page 490 and 491:

Index 459116, 127-130, 133, 270, 27

-

Page 492 and 493:

Index 461computationin (PC) regress

-

Page 494 and 495:

Index 463discriminant principal com

-

Page 496 and 497:

Index 465of correlations between va

-

Page 498 and 499:

Index 467see also hypothesis testin

-

Page 500 and 501:

Index 469PC algorithms with noise 4

-

Page 502 and 503:

Index 471in functional and structur

-

Page 504 and 505:

Index 473variance ellipsoids,S-esti

-

Page 506 and 507:

Index 475spatial correlation/covari

-

Page 508 and 509:

Index 477for covariance matrices 26

-

Page 510 and 511:

Author Index 479Belsley, D.A. 169Be

-

Page 512 and 513:

Author Index 481Fowlkes, E.B. 377Fr

-

Page 514 and 515:

Author Index 483Krzanowski, W.J. 46

-

Page 516 and 517:

Author Index 485Rencher, A.C. 64, 1

-

Page 518:

Author Index 487Yaguchi, H. 371Yana