TELUGU FOLKLORE - Wiki - National Folklore Support Centre

TELUGU FOLKLORE - Wiki - National Folklore Support Centre

TELUGU FOLKLORE - Wiki - National Folklore Support Centre

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

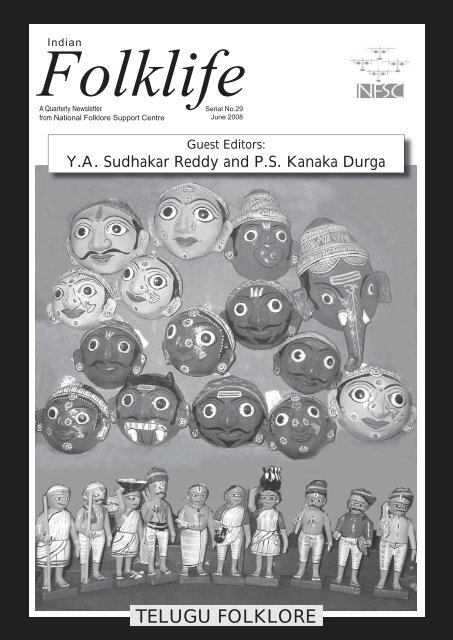

IndianFolklifeA Quarterly Newsletterfrom <strong>National</strong> <strong>Folklore</strong> <strong>Support</strong> <strong>Centre</strong>Serial No.29June 2008Guest Editors:Y.A. Sudhakar Reddy and P.S. Kanaka Durga<strong>TELUGU</strong> <strong>FOLKLORE</strong>

2NATIONAL <strong>FOLKLORE</strong> SUPPORT CENTRE<strong>National</strong> <strong>Folklore</strong> <strong>Support</strong> <strong>Centre</strong> (NFSC) is a non-governmental, non-profit organisation, registeredin Chennai, dedicated to the promotion of Indian folklore research, education, training, networking, andpublications. The aim of the <strong>Centre</strong> is to integrate scholarship with activism, aesthetic appreciation withcommunity development, comparative folklore studies with cultural diversities and identities, disseminationof information with multi-disciplinary dialogues, folklore fieldwork with developmental issues and folklore advocacy withpublic programming events. <strong>Folklore</strong> is a tradition based on any expressive behaviour that brings a group together, createsa convention and commits it to cultural memory. NFSC aims to achieve its goals through cooperative and experimentalactivities at various levels. NFSC is supported by grants from the Ford Foundation and Tata Education Trust.C O N T E N T SNarrative Traditions and Folktales of AndhraPradesh.................................................... 3Narrative Tradition as a Cultural Allegory:Reflections from Telugu <strong>Folklore</strong> .................. 4Folk Tales of Andhra Pradesh –What do they convey? ................................ 8Folk Tales from Andhra Pradesh .................. 11Toy Making: A Popular Craft ....................... 14Leather Puppetry: The Art and Tradition ....... 16Oggukatha ............................................... 17Memoirs of a Folk Performer(Chukka Sattiah: Oggukatha Performer) ........ 18Embossed Sheet Metal Craft ofAndhra Pradesh ........................................ 19Burra Katha: A Unique Narrative Folkart form .................................................. 20Pagativeshalu: A Folk Theatrical Form .......... 21Surabhi Theatre : A Legacy to Continue ........ 22B O A R D O F T R U S T E E SCHAIRMANJyotindra JainProfessor, School of Arts and Aesthetics,Jawaharlal Nehru University, New DelhiTRUSTEESAjay S. MehtaExecutive Director, <strong>National</strong> Foundation for India, India Habitat <strong>Centre</strong>,Zone 4 – A, UG Floor, Lodhi Road, New DelhiAshoke ChatterjeeHonorary Chairman, Crafts Council of India, B 1002, Rushin Tower,Behind Someshwar Complex, Satellite Road, Ahmedabad – 380015N. Bhakthavathsala ReddyRegistrar, Potti Sreeramulu Telugu University, Public Garden, HyderabadDadi D.PudumjeePresident, UNIMA International, Director, Ishara Puppet Theatre,B2/2211 Vasant Kunj, New DelhiDeborah ThiagarajanPresident, Madras Craft Foundation, Besant Nagar, ChennaiMolly KaushalProfessor, Indira Gandhi <strong>National</strong> <strong>Centre</strong> for the Arts,C. V. Mess, Janpath, New DelhiMunira SenDirector, Common Purpose India, Vasanth Nagar, Bangalore - 560 052K. RamadasKaramballi, Via Santosh Nagar, Udipi 576 102Y.A. Sudhakar ReddyProfessor and Head, University of Hyderabad,<strong>Centre</strong> for Folk Culture Studies, S.N. School, HyderabadVeenapani ChawlaTheatre Director, Adishankti Laboratory for Theater Research, PondicherryE X E C U T I V E T R U S T E E A N D D I R E C T O RM.D. MuthukumaraswamySTAFFAssistant Director Archivist and Educational Graphic Research Fellow Research Fellow (Library(Administration) Administrative Secretary Co-ordinator Designer (Publication) and Information Resources)T.R. Sivasubramaniam B. Jishamol A. Sivaraj P. Sivasakthivel Seema .M S. RadhakrishnanProgram Officer Program Officer Research Fellows <strong>Support</strong> Staff(Publications and (Field Work) (Field Work) C. KannanCommunication) K. Muthukumar S. Aruvi A. MohanaJ. Malarvizhi S. Rajasekar M. SenthilnathanINDIAN FOLKLIFE EDITORIAL TEAMEditor Associate Editors Guest Editors Page Layout & DesignM.D. Muthukumaraswamy J. Malarvizhi Y.A. Sudhakar Reddy P. SivasakthivelSeema .MP.S. Kanaka DurgaFor Internet broadcasting and public programmes schedule at Indian School of <strong>Folklore</strong> visit our websiteAll the previous issues of Indian Folklife can be freely downloaded from http://www.indianfolklore.orgINDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

E D I T O R I A L3“NARRATIVE TRADITIONS” AND“FOLKTALES OF ANDHRA PRADESH”Y.A. SUDHAKAR REDDY and P.S. KANAKA DURGAY.A. SUDHAKAR REDDY, Professor and Head,University of Hyderabad, <strong>Centre</strong> for Folk CultureStudies, S.N. School, Hyderabad.P.S. KANAKA DURGA, Reader, <strong>Centre</strong> for FolkCulture Studies, School of Social Sciences,University of HyderabadThe folklore of India in general and AndhraPradesh in particular encompasses variousaspects of expressive behaviour as a dialoguebetween human groups and their physical andsocial environments. These manifold cultural formsare information banks and communication systemsthat explicate the spatio-temporal dynamics ofadaptive processes. <strong>Folklore</strong> studies from the Indianperspective perhaps lies in the amalgamation ofthe hegemonic model based on literacy and themnemonic model grounded in orality. The formerbrings out the linear structural paradigms innatelyrepresented in cultural expressive traditions andthe latter reveals the non-linear and hyper-textualstructural patterns that form the cultural behavioursof the Indian populace.The study of folklore, therefore, is vital forhermeneutic, ideological and philosophicalreasons. Hermeneutically, it combines literacy withorality and analyses Indian culture by juxtaposingwritten records with oral records in hyper-textualformats. Ideologically, it ensures the continuity ofcognizance of Indian culture preventing interferenceof global agencies that try to superimpose universalcultural models over people. Philosophically, itstrengthens cultural practices of non-hegemonicand marginalized communities that have sustainedthe ethos of the country wherever folk cultures arestill alive and have contributed immensely to thenotion of nation.Tale telling is a folk practice that not only revealsthe worldview of the tellers and their stockaudience but also strengthens their bonds as acommunity. The whole process of performanceof tale telling articulates the identity of the folkcommunity. The papers on “Narrative Traditions”and “Folktales of A.P.” included in this issue arean attempt to describe and analyze the verbalexpressive traditions of communities practisingthe folk arts in Andhra Pradesh. The articles onthe different verbal and non-verbal art traditionsof Andhra Pradesh such as Burra Katha, OgguKatha, Pagativesham, toy making and metal craftin this issue attest the fact that these are still livingtraditions of the Telugu speaking people.In the wake of globalization, however, communitiespractising these arts are being marginalized andstruggling to retain their own identity. ‘Givingback to the people what we have taken from themand what rightfully belongs to them’ is the ethicaland moral basis of the study of folklore. This selfconsciousness,if developed, would benefit variousfolk groups that are often stereotyped as illiterateand backward. Already, the forces of modernity asrepresented in the new socio-economic formationsregulated by the global capitalist market have recodifiedexisting language systems and semioticsthrough the electronic media and eclipsed thecommunities that were based on orality. To preventthis, the new generation needs to be sensitizedthrough the publication of such newsletters andother means. Hence, this humble attempt. ❆INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

4NARRATIVE TRADITIONAS A CULTURAL ALLEGORY:Reflections from Telugu <strong>Folklore</strong>Y.A.SUDHAKAR REDDY, Professor, <strong>Centre</strong> for FolkCulture Studies, School of Social Sciences, Universityof HyderabadIn nucleated villages of upland Andhra Pradesh,the monsoon is the primary source of water in theabsence of perennial rivers. The task of peasantrybecame two fold - first, the channeling and augmentingof rainwater flow, and second, streamlining ofcropping pattern (wet and dry) with the flow of water.This situation demands much labour. Fetching labourseasonally could throw productivity and costs out ofsync and causes migration of labour that could adverselyaffect the rural economy. One way of solving such acrisis is restricting the mobility of labour by a ‘moraleconomy’ where reciprocity norms are regulated bysubsistence (Scott 1977). Hence, it is not uncommonto tie the agrarian proletariat to the land (i.e. bondedlabour) in these villages. The ‘bard tradition’ perhapsemerged as a device to enable such restriction. Itis interesting to note that the ‘bard tradition’ existsin the upland cultures more than in other culturessuch as valley or forest cultures.This further complicates the social organization ofthese villages. The identity of patron and bard areconstrued through a process of symbiosis - onesurvives because of the other through a share ineconomic resources given by patrons to minstrels.The latter creates “identity” through the narrativeand reminds them of their roles and social obligationsin a larger social structure.This leads to a social stratification within the castes, theparameter being the level of involvement in agrariantasks. The bard tradition can be seen as a mediatingfactor to sustain peasantry and agrarian proletariatwithin the village space through the recitation ofcaste myth. Anti-structural tendencies are explicitin their oral narratives and rites and rituals, whichwish for role-reversals of castes vis-à-vis the conceptof purity-pollution.In table-1, it is evident that every bard communityhas a narrative to perform to the patron community.The Jambapuranam narrative, the caste myth of theMadiga community, is presented here to postulatedistinct features of the folk narratives found in theform of caste myths of rural India in general andAndhra Pradesh in particular.Y.A. SUDHAKAR REDDYThe oral text in its performative context is collectedfrom a minstrel community of the Madigas namely, theCindu Madigas. Two dimensions of the Jambapuranamare considered here - the story’s causal structure (plot)and the sequence of events as ordered in the narrativeby the narrator (discourse).(1) Plot as Narrative Structure:The plot of Jambapuranam is tri-episodic—the AdiPuranam, Sakti Puranam and Basava Puranam. Themyth being a multi-plot structure, it can be performedindependently or as a whole. Performers manipulateduration of each unit of performance both in verticaland linear temporality by transiting between the realmsof performance text and mental text with the Madiga asan axis. The performers can shift back and forth in thetext in narrating the units of the text.Table-1: Bards and their Caste MythsS.No. Castes Dependent Castes Caste Myth1. Brahmanas Vipravinodis Magic2. Vaisya Viramusti Kanyaka katha3. Visva brahmanaPanasoluRunjalavallu4. Mutrasi Kaki padagalapandavullavaru5. Gauda Gauda jettiEkoti6. Padmasali Sadhana suruluKuna puliRunjaKulapuranamPatam kathaGauda puranamMagic7. Mangali Addanki siggadu Mangali puranam8. Chakali GanjikutiMadelu puranammasayya9. Kummari Pekkari —10. Golla MandecchuOggu pujarluButta bommaluYadava kathalu11. Reddi Picchukakuntlu Reddi puranam12. Madiga ChinduDakkaliBaindlaMastiNulaka chendayyaJambapuranam/YaksaganamPatam kathaRenuka Yallamma puranamAdipuranamPujari, kolupulu/kathaluRitual/recitation13. Mala Gurrapollu Patamkatha/kulapuranam14. Lambada Bhats / Bhatts Banjara kathalu15. Nayakapodu Korrajulu/toti/Pujarlu Patamkatha16. Gondu Pruthan Vamsa katha17. Koya Doli —INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

5The text of Jambapuranam is ritually enacted by theCindu Madigas. The performance of Jambapuranamcommences with the beating of drums. Theprotagonist of the play is taken in a procession tothe place of performance. The other characters suchas the Brahmin and the comic characters prepare theaudience to receive the performance of Jambapuranam.With the entry of Jambavantudu, the protagonist, theperformance commences. Thewhole performance takes adiscourse style between theprotagonist who representsthe pancamavarna and theBrahmin that represents thesystem of caturvarna. Thesetwo characters voice argumentsfor and against the high and lowcastes. The Brahmin questionsthe wisdom of Jambavamuni,the ancestor of the Madigas.Jambavamuni patiently repliesto all the queries of the Brahminand upholds his occupationand his caste role in the societyas one that is embedded inthe dharmic tradition. In theprocess of dialogue both thecharacters bring in issuesrelated to economic changesvis-à-vis social relations. Forinstance, though the leatherbuckets are replaced by pumpA performer of Jambapuranamsets, Jambavamuni still finds the role of Madigas insupplying certain leather material such as washers torun them.The performance runs four to five hours in a dialoguesong-dancematrix. This performance is followed bythe performance of Yellamma vesham, which is a ritualpossession that ends with bloody sacrifice.(2) Narrative performance as Discourse:The performance of the caste myth Jambapuranam is asymbolic system that ties the community of Madigas toeach other and with the rest of the village. To understandthe narrative discourse of the Jambapuranam, it isimperative to know the cultural milieu of the Madigaswho own the narrative.In pre-independence India, the Madigas wereconsidered among the outcastes living outside theframe of the Varna system. They are treated aspanchama varna or ‘untouchables’. The Madigas alongwith the Malas live outside the main village. Their chiefprofession is scavenging, including the disposal of thedead carcasses. They developed occupations relatedto leather–skinning, tanning, and manufacturingleather goods. They performed all the lowest kinds ofservices to the upper castes. They take charge of theox or buffalo as soon as it dies. They remove the skinand tan it and eat the carcasses. Some of the skins areused for covering the crude drums known as Tappetaor Dappu that are largely used in the village festivals.The main duty of Madigas is curing and tanning hidesand making crude leather articles. The Madiga is paidin kind and he has to supply sandals for peasants, beltsfor the bulls, and all the necessities of agriculture.The Madigas also call themselves as Jambavas andclaim to be descended from Jambu or Adi-Jambuvaduwho is perhaps the Jambavantudu of the Ramayana.Edgar Thurston recorded that some Madigas, calledSindhuvallu, act scenes from the Mahabharatha andRamayana or the story of Ankalamma. They also assertthat they fell to their present low position as the resultof a curse and tell the following story.“Kamadhenu, the sacred cow of the puranas, wasyielding plenty of milk, which the Devatas alone used.Vellamanu, a Madiga boy was anxious to taste themilk, but was advised by Adi-Jambuvadu to abstainfrom it. He however secured some by stealth andthought that the flesh would be sweeter still. Learningthis, Kamadhenu died. The Devatas cut its carcass intofour parts, of which they gave one to Adi-Jambavudu.But they wanted the cow brought back to life, and eachbrought his share of it for the purpose of reconstruction.But Vellamanu had cut a bit of the flesh, boiled it, andbreathed on it, so that, when the animal was recalledto life, its chin sank, as the flesh had been defiled. Thisled to the sinking of the Madigas in the social scale.”The following variant of this myth is given in theMysore Census Report, 1891.“At a remote period, sage Jambava Rishi was questionedby Lord Siva about why the former was habitually lateat the Divine Court. The sage replied that he had topersonally attend to the wants of his children every day,which consequently made his attendance late…Siva,pitying the children gave the rishi the cow Kamadhenu,which supplied their every want. Once while Jambavawas absent at Ishvara’s court, another sage namedSankya visited Jambava’s hermitage, where his sonYugamuni hospitably entertained him. The cream thathe served was so savoury that the guest tried to induceJambava’s son Yugamuni to kill the cow and eat herflesh. In spite of the latter’s refusal, Sankya killed theanimal and prevailed upon the others to partake ofthe meat. On his return from court Jambava found theinmates of his hermitage eating the sacred cow’s beefand took both Sankya and Yugamuni over to the courtfor judgement. Instead of entering, the two offendersremained outside, Sankya rishi standing on the rightside and Yugamuni on the left of the doorway. Sivacursed them to become Chandalas or outcastes. Hence,Sankya’s descendants are designated right hand casteor Holayas (or malas); while those who sprang fromYugamuni and his wife Matangi are called left-handcaste or Madigas”. The occupation of the latter is saidto be founded on the belief that by making shoes forINDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

7Foucault, Michel (1978) The History of Sexuality, trans.Robert Hurley, New York: Random House.Freytag, Gustav (rpt.1968) Technique of Drama—AnExposition of Dramatic Composition and Art, (tr).Glassie, Henry (1982) Passing the Time in Ballymenone:Culture and History of an Ulster Community. Philadelphia:University of Pennsylvania Press.___. ‘ATradition’ (1995) in Common Ground: Keywordsfor the Study of Expressive Culture, ed. Burt Feintuch,Journal of American <strong>Folklore</strong> vol. 108, Fall, Number430: 395-412.Herman, David (2002) Story Logic: Problems andPossibilities of Narrative, Lincoln: University of NebraskaPress.Levi-Strauss, Claude (1978) A Harelips and Twins: TheSplitting of a Myth, in Myth and Meaning. New York:Shocken Books, pp.25-33.___. (1971) The Naked Man: An Introduction to a Scienceof Meaning, vol. 4. New York: Harper and Row.___. (1969) The Raw and the Cooked: MythologiquesVolume 1, trans. by John and Doreen Weightman.Chicago: The University of Chicago Press,.___. (1966) (originally published in French 1962) TheSavage Mind. Trans. George Weidenfeld and NicholsonLtd. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.___. (1963) Structural Anthropology, New York: BasicBooks.Lord, Albert B. (1960) The Singer of Tales. Cambridge:Harvard University Press.Lyotard, Jean-François (1984[1979]) The PostmodernCondition: A Report on Knowledge, trans. Geoff Benningtonand Brian Massumi, Minneapolis: University ofMinnesota Press.Oring, Elliott (1986) Folk Groups and <strong>Folklore</strong> Genres: AnIntroduction. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press.Prince, Gerald (2003) A Dictionary of Narratology,Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.Ricoeur, Paul (1984-88) Time and Narrative, 3 vols., trans.Kathleen McLaughlin and Paul Pellauer, Chicago:University of Chicago Press.Ricoeur, Paul (1980) A Narrative Time in On Narrative,ed. W.J.T. Mitchell. Chicago: The University of ChicagoPress, pp.165-186.Ryan, Marie-Laure (2004) ‘Introduction’, in Marie-Laure Ryan (ed.) Narrative Across Media: The Languagesof Storytelling, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.Schaeffer, Jean-Marie (1999) Pourquoi la fiction?, Paris:Seuil.Sturgess, Philip (1992) Narrativity: Theory and Practice,Oxford: Clarendon Press.Sudhakar Reddy, Y.A. (2001) ‘Ritual PerformancesAnd Theoretical Validity to <strong>Folklore</strong>: The Case ofAndhra Pradesh’, in Dravidian Folk and Tribal Lore, (ed.)B. Ramakrishna Reddy, Kuppam. Dravidian University,pp.293-313.White, Hayden (1981) ‘The Value of Narrativityin the Representation of History’, in W.J.T. Mitchell(ed.) On Narrative, Chicago: University of ChicagoPress. ❆Vishnu VishwaroopaCourtesy:http://www.chitrahandicrafts.com/products_white.htmlINDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

9discloses everything to the neighbors and proudlyrefuses to take help from them. He had no respect forfeminine duties and does not bother acknowledgingthe supportive role that a wife plays in successfulfamily life. The wife’s gender-specific behaviour indomestic and public spheres satisfied the norms ofthe dominant society, providing the ‘role model’ foran Indian woman. The teller belongs to the oldergeneration and she expects women to be acquiescentto bring trespassers back into tradition.The two versions of this tale represent not only adialogue, but also a negotiation between genderideology and reality in changing times. They appear toshow the re-fixing of the prefixed gender boundaries towomen and men but the characters and their interactionin different events in storyline emphasize the need forprotecting families from gender anarchy that woulddisrupt the peace of the village.(II) Women’s Folktales: An Art of SubversionFolktales seem an effective medium for women toorganize their fantasies, daydreams, expectations,wishes and memories in the normative world and exalttheir social positioning in the world of imagination.Hence the tales told by women are indices of explicitand implicit cultural realities that they face in patriarchalsociety.Yasodamma (40) belongs to the Balija (inland trading)community. She said that income from the family’sthree acres of dry land and a few cattle is hand-tomouth.Her parents and in-laws are petty vendorswho sell grains, pulses and other food accessories. Shenarrated Komati pilla, Raju katha (Tale of Komati (thetraditional trading community) girl and a King) (Tale IV)to her children and teenage girls in her neighbourhood.It tells of a married woman who rescued her husbandby outwitting another woman who does not come froma family tradition.The tale is made of two stories, the first having animalcharacters and the second human characters. Thelinkage between the two is constructed with the helpof a ‘judgment episode’ in which the female dies withunfulfilled desire to revive her family relations. Thetale ends with the reunion of the wife with husbandwho realized his fault and lives happily with her.The tale depicts two different conceptions of theinstitution of marriage and family by the male andfemale genders. The former view is from the egocentricpatriarchal male chauvinistic perspective, marginalisingthe involvement of the other gender (female) inleading a happy family life. It does not see the femaleas a ‘subject’ who has a pivotal role to play in theperpetuation of traditions in the family and society. Thefemale views the same patriarchy positively as a meansof protection and safety to the institution of family.The female protagonist has understanding of the prosand cons of patriarchy and she uses the same patriarchalinstitution as a strategy to outwit the alternate / counterinstitution of concubinage and brings her husband backto the fold of tradition or family. She took a lead role inreviving her wedded life and proved to be a successfullife partner. The male as a consort in this tale violatedthe bondage of marriage institution strategically toestablish male ascendancy over females through(1) legality, (2) matrimony and (3) concubinage.(1) The male crow exercised its right of patriarchy ofits child and family through legality establishedby madhyastham (mediation), but later violated theduty of a husband, leaving his wife and mercilesslyseparating the child from its mother, causing notonly breakup of the family but also the death of itsconsort.(2) The prince violated the rules of endogamousmarriage and married a girl from the Komati (Vaisya,third in the linear varna system) community.(3) As a part of his revenge, the prince resorted toconcubinage, which is a counter institution tofamily tradition.In the tale, the female protagonist is shown as therestorer of the tradition who used the same patriarchallegality and marriage system as strategies to bring herhusband into the boundaries of family tradition fromconcubinage. The observance of the tradition whichthe male refused to follow is reinforced by the femaleprotagonist. Thus she restituted the ideals of marriagethat were being violated by her husband.In the tale, the female’s winning over the male indisguise shows that men and women are equalpotentates and that their gender roles and duties aresocio-cultural constructs that determine their relationsin family and society. The tale further establishes theambivalent power of tradition that could make andbreak families if not judiciously manipulated accordingto cultural norms. The culturally constructed femininetraits like patience, forbearance and wisdom enhancethe power of the woman to act accordingly and outwitcontenders, even of their own gender, but operating indifferent gender relations.(III) Women and Social Identity in FolktalesThe stories told by women often show a perfect fusionand articulation of self with the tradition and cultureof a society in which they are constructed (Durga2006:87-140). Thus the selves are storied as tales sinceexperiences have little value as long as they are notconnected by narrative. Identity and narrative/storiedaccounts get entwined as the individual reflects, revisesand refines a present and future identity. Women aspirefor identity at personal and social levels through thenarrations of folktales. Stories always imply a temporalINDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

10organization of events, and a plot structure thatmeaningfully relates past, present, and future. At thesame time, stories are organized around actors who, asprotagonist and antagonist, have opposite positions ina real or imaginary space. Both the storyteller and theactors in the stories told are intentional beings who aremotivated to reach particular goals which function asorganizing story themes in their narratives.ReferencesDavid De Leviton, J (1965: 52) The Concept of Identity,New York: Basic Book.Erikson, Eric, H (1968) Identity: Youth and Crisis,New York: Norton.Erison, F (1986) ‘Qualitative Methods in research onTeaching’, in M. Wittrock (ed) Handbook of research onteaching. New York: Macmillian pp. 199-161; Jank W,and Meyer, H (1991), Didaktische Modelle, Frankfurtam Main, Germany: Cornelsen Verlag Scriptor GmbH& co).Flax, Jane (1989) ‘Postmodernism and Gender Relationsin Feminist Theory’, in Micheline, R. Lalson, Jean,F.O. Barr, Sarah Westphal-Wihl and Marry Wyer (eds).Feminist Theory in Practice, London: The University ofChicago Press, pp.51-73 and p.60.Foucault, Michel, (1979) ‘What is an Author?’ in JosueHararri, Textual Strategies: Perspectives in PoststructuralistCriticism, Ithaca, NY: Cornel University Press._____ (1980) Power/ Knowledge: Selected Interviews andOther Writings 1972-1977, New York: Pantheon._____ (1983), ‘The Subject and Power’ in HubertDreyfus and Paul Rainbow (Eds) Michel Foucault, BeyondStructuralism and Hermeneutics, Chicago: University ofChicago Press.Polkinghorne, Donald (1988) Narrative, Knowing andthe Human Sciences. Albany, NY: SUNY Press; White,Hayden (1987) The Content of the Form. Baltimore: JohnsHopkins University Press.Holmberg, Carl, B (1998) Sexualities and PopularCulture, Foundations of Popular Culture, London: SagePublications. 60; pp.59-88.Kanaka Durga, P.S (2006) ‘Transformability of GenderRoles: Converging Identities in Personal and PoeticNarratives’ (eds), Leela Prasad, Ruth, B. Bottingheimer& Lalitha Handoo, Gender and Story in India, Albany,State University of New York Press. pp. 87-140.McCall and Simons (1978) Identities and Interactions,New York: Free Press.Mitchel, W.J.T (1981) (ed) On Narrative, Chicago andLondon: the University of Chicago Press, pp.1-24.Marie-LaureRyan (2003) ‘On Defining NarrativeMedia’, Image & Narrative: Online Magazine of the VisualNarrative-ISSN1780-678 X, Issue 6. Medium Theory,February 2003.Polkinghorne, Donald (1988) Narrative, Knowing and theHuman Sciences. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.Ricoeur (1988 Vol:33) Time and Narrative, trans.K.McLaughlin and Pellauer, Vol.I (Chicago: TheUniversity of Chicago Press, 1984, p.33.____ Oneself as Another, trans. Kathleen Blamey.Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992 (1990)Stets E & Burke P.J. (2000) ‘Identity Theory and SocialIdentity Theory’, Social Psychology Quarterly, 63, pp.224-23.Tajfel & Turner, J.C. (1979) ‘An Integrative Theory ofIntergroup Conflict’, in W.G. Austin & S. Worchel (eds)The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations Monterey,CA: Brooks-Cole. pp.33-47.Tajfel H & Turner J.X. (1986) ‘The Social IdentityTheory of Intergroup Behaviour’, in S. WorchelW.G. Austin (eds) Psychology of Intergroup RelationsChicago, Nelson-Hal, pp7-24.White, Hyden, (1981) ‘The Value of Narrativity inthe Representation of Reality’, in W.J.T. Mitchel, (ed)On Narrative, Chicago and London: the University ofChicago Press, pp.1-24.Widdershoven, A.M (1993) ‘The Story of Life:Hermeneutic Perspectives on the Relationship BetweenNarrative and Life History’, in (ed.) Ruthellen Josselsonand Amia Lieblich, The Narrative Study of Lives, London,Sage Publications, pp.1-20.Wylie, R.C (1968) ‘The Present Status of Self Theory’,in E.F. Gorgotta and E.E. Lambert (eds.) Handbookof Personality Theory and Research, Chicago: Rand,M.C. Valley.____ (1979) The Self-concept. Vol. 2: Theory and researchon selected topics. Lincoln, NB: University of NebraskaPress. ❆INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

12On the other side, the wife arrogantly whipped thebulls on the way to the field. Everyone stared at her.She thought they were jealous of her. The bulls wereunable to bear the whipping, since the farmer neverbeat them while driving. They became angry andscampered around. She was unable to manage them.They finally threw her in mud.With great difficulty, she got up. Some women liftedher from the mud and the men soothed the bulls andtied them to the cart. She told them she could drive.They wondered at her pride. She drove the cart to herfield and reached there by lunchtime. The sun wasoverhead. The bulls were hungry. She tied them toa plough. Two hours later, she found that the fieldwas not ploughed. The men working in the field staredat her, they tried not to laugh. She rudely shoutedat them to mind their business. An elderly man toldher, “ My child, you forgot to fix the gorru (a woodeninstrument with two to six projections of wood oriron, that help effective ploughing) Family life andfarming cannot be successful without man and gorru.”She became irritated and stopped work to eat lunch.Since the food was not seasoned properly, it had beenspoiled. She could not ask anyone else for food sincethey had already finished lunch. She did not know thather husband gave fodder to the bulls and took them todrink water at lunchtime. The bulls were hungry andthirsty and began to make a lot of noise. The otherfarmers took the bulls for fodder and water withouttelling her. By the time the bulls returned, the othershad begun to pack up.The wife tied the bulls to the cart and reached homelate in the evening. All the way home, she cursedher husband and was eager to quarrel with him fornot telling her the about the process of tilling and thetechnique of driving a bullock-cart. Her husband waswaiting at the door. Before she opened her mouth,he slapped her. She gave him a blow with the whip.Everybody in the neighbourhood came out to watch thescene. He remembered all the mockery his neighbourshad directed at him since early morning and hence hedragged his wife on to the floor and beat her.A village head passing by stopped them and enquiredwhat the matter was. They both narrated the entireepisode. Everybody, including the village head,laughed at them. He told them, “One should do theduty prescribed to them by experienced elders andproven tradition. Go and do your duties as usual fromtomorrow and don’t disturb the village.”The couple bent their heads in shame. They went homehappily and neither quarrelled nor attempted again toexchange their roles.Mogudu Pellala Katha(The story of Husband and Wife) (Version 2)The husband wants to reverse roles because hethought that his wife is having an easy time athome. Though his wife tells him of the difficultiesat home, he harasses her to switch roles. Finally,she accepted and decided to teach him a lesson. Thehusband was very happy. The wife went to the fieldand finished all the work to be completed on that daywith the help of fellow farmers. She told them thather husband was not well. She returned home. Butthe husband could not do anything as in the previousversion of the tale. He beat her up badly since she didnot tell him anything about the kitchen. She didn’trespond, finished all the work at home and offeredhim a hot water bath and delicious food. She soothedher child and put her to sleep. Then the husbandrealized his mistake and begged her pardon for notunderstanding the roles determined by elders for menand women in family and society.Komatipilla-Raju Katha(Merchant girl and king’s story)Once there was a pair of crows in a village. Therewas continuous drought and famine for sevenyears. All living things began to perish fromstarvation. The male crow said to the female crow, “Letus go to some place where we can get abundant food”.The female crow refused to go and told him, “Wherecan we go leaving native place and friends behind? Wemay have a good future right here.”The male crow abandoned his family to their fate. Afterthe male crow left the village, there was a big rain, asbig as an ocean. The female crow and her female childfound shelter in a tree in the kitchen garden of a Komaticouple (belonging to trading community). They spentpeaceful days eating the leftover food from the house.Three years later, the male crow returned and askedher to live with him. The female crow refused, saying,“You left us in distress. You did not even bother ifyour wife and child were dead or alive. Now wheneverything is normal, you come back and ask me tostay with you.” The male crow went to madhyastham(mediation) and asked the judge to call his wife fortrial. The male crow asked the judge, “Who owns thechild?” The judge gave the verdict that the father ownsthe child, not the mother. The male crow took thechild and flew away. The female crow took a copy ofthe judgment with her and returned home with grief.She preserved the document in the thatched roof ofher protector’s front hall. The crow pined away in thesorrow of losing her child and finally died. The Komaticouple performed the funeral for the female crow.They did not have children till then. Now the wifeconceived and gave birth to a female child. The girlINDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

13was brought up with affection and good discipline.The girl grew to an age of puberty. On a full moonday, she was sitting under a tree where the crow livedformerly. Looking at the dismantled crow nest, the girlasked her father suddenly, “Father, how many cowsare there in the cattle shed of our king?” The fathertold her, “My dear little girl, there are hundred cowsin the cattle shed of the king.” She told him, “Father,purchase a strong, sturdy and healthy calf.” Her fatherbrought a young male calf. She fed that calf with richfodder- coconut cakes, cottonseeds, and green grass.The calf grew into a handsome and healthy ox. Oneday she put her ox into the king’s herd of cows. Afterthree months, all hundred cows gave birth to hundredyoung calves. One day, the girl sent her servants andbrought all the calves to her cattle shed. All the cowscried for their calves. The king sent word through hisservants, “Hand over our calves to us immediately.Our cows are weeping for their calves. Calves belong tocows.” The girl refused to hand over them and repliedadamantly, “Come for madhyastham (mediation). Letus finalise there”.In ‘madhyastham’, the case was adjudicated. The girlshowed the judgment document given by the sameking while he was dealing with the case of crow andits family. His verdict was, “Father owns the child, notthe mother”. The king could not say anything. Thegirl took away all her calves. Since the cows could notsurvive without their calves, the king sent them alsoto her.The king had a son who felt insulted by the event. Hetold his father, “I will put down her pride by marryingher. I will take revenge on her for the humiliation thatshe inflicted on you.” The king sent his men withmarriage proposal to her parents. The Komati refusedthe proposal. The prince himself went and convincedher father.The girl understood the situation and consented to marryhim since they should not deny the king’s proposal.The girl who had been observing the temperament ofprince from the beginning told her father, “Father, digan underground tunnel from our house to the cattleshed of the king’s palace”.After marriage, the prince did not even look at theface of the girl and ignored her completely. She did allher duties as a daughter-in-law and slept in the cattleshed. She went to her parents through the tunnel, atefood and returned by the time her husband reachedthe palace.One day, the prince was leaving the country for alonger time. The girl went to help him in soaping hisback while he was taking his bath. He ridiculed herand asked, “Who are you to touch me?” She replied, “Iam your wife and you are my husband.”He burst into laughter and told her, “He who eats yourchewed and spitted tambula (made of betel leaves, nutpowder, lime and spices like elachi, cloves, camphor)is your husband, I am not. He who carries your sandalsbehind you, is your husband, I am not. He who walksbehind you on the bed of the thorns of the ‘palleru’plant on twelve ‘kuntas’ (0.3. acres) of land is yourhusband, I am not. Go and search for him.”He left the palace without informing her when he wouldbe back. He travelled a lot. On his way, he found manypeople carrying red soil in pans on their heads to thetank bund under construction. He went to the house ofan old lady and enquired about them. She told him ofa courtesan who earned ninety thousand rupees frommen without allowing them to touch her. She set acondition that those who wanted to enjoy her bodyshould defeat her in dice. She would surrender herselfand her property to the winner. The losers should carryred soil to the tank. She had a cat and placed a burninglamp on its head. The game is played in that light. Ifthe cat moves in the middle of the game, she has beendefeated. If the cat sits still, the customer is defeated.The prince wanted to participate in the game. He wasdefeated and carried soil to the tank bund. Two or threemonths passed. His wife determined to search for him.She put on male attire, rode a horse and left the palacethrough the tunnel in search of her husband.After long travel, she reached the village and found herhusband near the tank bund carrying soil on his head.She found out what the matter was and got back to hervillage. She asked her father to raise a crop of ‘palleru’plants in twelve kuntas of land (0.3 acres) on the wayto their village and spread out the thorny fruit.She bought two rats, removed their teeth and keptthem in her pocket. Then she went to the courtesanand agreed to play her game. When the game was infull swing, the girl removed the rats from her pocketand let them before the cat. The cat jumped after therat and the courtesan was defeated. The girl wentto the tank bund and released the slaves who werecarrying baskets of soil. All left for their homes exceptthe prince.The Komati girl noticed her husband standing withbent head beside her. She enquired about him withoutrevealing her identity. He told her about his nativeplace. She told him, “I have to travel the same way. Letus travel together.” The prince agreed and sat on thehorse behind her. After some time, she ate her foodand gave the remaining to him. He also ate. The girlchewed tambulam and spat it on a stone. Before sheclimbed back on the horse, she told him that she hadforgotten her sandals and asked him to pick them up.He saw the betel nut she had spat and ate it. Then hegave her sandals to her. They travelled together formany days.When they drew near her village she asked him toget down as she had other work to do there. The girldisappeared from his sight before he turned back to seeINDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

14where she was going. He went into the village, walkingover the twelve kuntas land covered with the thorns.The girl reached home and wrote down all experiencesof her life from her wedding till the moment shedropped her husband near the village. The next day,she called her husband for madhyastham (mediation)and showed the paper to the elders.Then she asked her husband before the elders:“Have you not eaten the tambulam I spat out?” Thegirl asked.“Yes”, the prince replied.“Have you not carried my sandals“, the girl asked.“Yes”, the prince replied.“Have you not walked behind me on thorns?”, the girlasked.“Yes”, the prince replied.“Now, are you not my husband?”, the girl questioned.“Yes, I am your husband”, the prince replied.Then both of them went home and lived happilytogether. ❆Toy Making: A Popular CraftARCHANAARCHANA, Department of Archaeology,Deccan College of Post Graduation and ResearchInstitute, PuneThe images of deities and animate and inanimatebeings have been transposed to the children’sworld as toys in Andhra Pradesh. Kondapalli,Nirmal and Etikoppaka toys are the most significantwooden toys made in the state.Kondapalli toys are made in the Kondapalli villagethat is 17 km away from Vijayawada in the Krishnadistrict of Andhra Pradesh. The artisans who makethese toys are known as ‘Aryakshtriya’. It is said thatthese craftsmen migrated from Rajasthan and MadhyaPradesh to Kondapalli around the 16th century. Thetoys are known as ‘koyya bommalu’ meaning woodentoys. The wood used for this purpose is the Ponikiwood which is soft and light in weight and are alsoavailable in the nearby forests.The wood is cut into the required size and dried for 15or 20 days to make the wood light. The pieces are kepton a wire frame over a terracotta bowl with burningsawdust to make it warm and easy to carve. The bodyof the toy is carved and again exposed to heat formoisture to evaporate. The detailing is sculpted after allthe parts are joined to the main body and dried. Earliera vegetable gum made out of a paste of tamarind seedswas used to join the components which has now beenreplaced by Fevicol. The toy is given a smooth finishby filing. Brown paper or newspaper or other fabric isstuck on the cracked areas using maida solution. Afterit dries, it is smoothed with sandpaper.Sudda mitti (white paste) solution that has calciumcarbonate and acacia gum is applied as a first coat.Once dried, the toys are painted, usually by womenusing vegetable colours or enamel colours and brushesmade of goat’s hair. A coat of linseed oil is given totoys painted with vegetable colours to make themwater proof.Every member of the family participates in the processof making Kondapalli toys. The toys can roughly becategorized as those representing scenes from actuallife, those representing deities and others that captureanimal figures. The first type of the toys consists ofscenes which contain more than one figure. Forexample, it is common to find a simple single hut witha woman cooking, man climbing a palm tree, a womanmilking a cow or pounding grain or spinning a wheelor men guarding sheep. The second type of toys areconnected to animal figures both domestic and wild.The third type is usually related to mythological stories.The popular ones are the ten dolls that represent theten incarnation of Lord Vishnu. Representations ofShiva and all other gods of the Hindu pantheon arealso common.Nirmal toys:Nirmal, a village in the Adilabad district ofAndhra Pradesh is famous for its toys andpaintings. Nirmal toys are also carved in lightweightPoniki wood. The wooden blocks are soakedovernight and dried to lighten the colour of wood.Various components of the toys are joined together.Lacquer chips and bamboo are used for parts such asbeaks of birds or stems of fruit. Sandpaper is used tosmooth the surface. Sawdust and paste of tamarindseeds are applied on the toy.INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

15After the product dries, few cracks appear that are filledwith lappam, and then a coat of sudda mitti is appliedon the toy. Sudda mitti is fine clay gathered from theriver bank, used as a base coat before painting. Thetoys are finally dried and painted with vegetable oracrylic colours.The artisans make exact copies of fruits, vegetables,birds and animals. The texture of the fruits and animalsis depicted through finely painted lines. Initiallyvegetable dyes were used, but now water-based coloursare preferred. The craftsmen make their own coloursfrom minerals, gum and herbs. The dominant colourin Nirmal toys is gold, which is produced by boilingjuices of two kinds of plants in linseed oil.Birds are generally shown flying and a flock of threeto five makes a wall plaque. The less ornamented toysare made without application of colour. Glue made oftamarind seeds boiled to the consistency of a paste ismixed with white clay and applied to the surface ofthe toys. Those decorated lavishly are dominated bythe gold colour. Generally, the base colour is black ornatural mud. Colour, variety of designs and moodsmark the toys of Andhra Pradesh.Legend says that during the Nizam’s visit to Nirmal,he was given a grand welcome. All the craftsmenindulged themselves in decorating the venue, whichincluded an intricately designed banana bud whosepetals were coloured gold. This embellishment wassuspended above the Nizam’s seat. It unfurled andshowered golden petals on the Nizam. This impressedthe Nizam and from then on the woodcarvers whobelonged to the sect of Soma Kshatriyas received theroyal patronage from the overwhelmed Nizam.The ‘Nirmal Industry’ has been growing ever since itsinception in 1951 at Hyderabad. It developed Nirmalpaintings and handicrafts commanding an internationalmarket. The Nirmal Toys Industrial Cooperative Societyhousing 60 artisans was established in 1955. This is themain toy making unit while the Hyderabad branchmanufactures furniture and miniature paintings.Toys are also made of other kinds of wood like teakbesides Poniki and are given a natural finish. Solidcolour lacquering is preferred here. The use of chemicaldyes is prevalent. Lacquering is done by hand ormachine-operated lathe. In the lac turney method, thewooden blocks are temporarily fixed on the machineand the lac stick is pressed against the toy. The toykeeps moving and the heat generated makes the lac softand adhere to the product. After drying, the productis given a smooth finish. The craftsman later rubs theproduct with Mogule leaves which impart a brilliantshine. From small toys and tops for children to candleholders, Etikopaka artisans make them in a wide rangeof rich and wonderful colours.Ettikopakka toys depict gods and goddesses as wellas typical Carnatic musical instruments like the veena.They depict scenes like peasant woman working in thefield. Several other household articles like furniture aresold in toy sizes as well.Kondapalli, Nirmal and Etikopaka are the three maintoy-making centers in Andhra Pradesh. These toys aremade for commercial purposes. Other toys include thesawdust dolls and the Tirupati dolls.Sawdust toys are mainly made in Varigonda villagein Nellore district and Vemulavada and Nupuramvillages in East Godavari district. Local artists here makeattractive sawdust toys featuring traditional themes andhistorical figures from Hindu epics. They use adhesivesmade from plants like tumma (a thorny plant).Tirupati toys form an entirely different style of toys.They consist largely of reproductions of the religiousfigures in the classical style as seen in sculptures intemples. The deity figurines are made using a redcoloured wood red that gives the toy a distinctivelook. Red sandal wood (red sanders or raktachandan)is used in the Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh tocarve these dolls. This wood is resistant to white antsand fire. The dancing figures are highly ornamentedand beautifully chiseled, making these dolls unique.ReferencesSambashiva Rao (et al) Etikoppaka—Cultural developmentintervention project, NIFT, Hyderabad, 2005.Garima Kapil (et al) Hastakala—A document on Nirmaltoys, Department of Fashion and Lifestyle Accessories,NIFT, Hyderabad, 2006.Vijay Agarwal (et al) Kondapalli—A craft odyssey,NIFT, Hyderabad, 2003. ❆Etikoppaka toys:Etikoppaka, in the Vishakhapatnam district, is wellknown for traditional lacquered toys. The productsinclude toys, utility items like bowls, jars, andcontainers, and ornaments like bangles and earrings.INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

16Leather Puppetry: The Artand TraditionCH.MALLIKARJUNCH.MALLIKARJUN, M.A. Department of HistoryUniversity of HyderabadLeather puppetry is called ‘tolubommalata’ inTelugu. The word ‘tholu’ means leather and‘bommal-ta’, playing with leather dolls orfigurines. It was once presented by indigenous Telugufolk artistes known as ‘ata gollalu’ (cowherds players)who belong to the Jangama (Saivite mendicants), andBalija castes. Today, most puppet players in Andhralive in some villages of Vishakapatnam, East Godavari,Ananthapur, Cuddapah, Nellore, Nalgonda andGuntur.Puppets are made of deer, goat, calf or buffalo skins.These hides are tanned, made translucent and cutinto various shapes and sizes. The sizes of puppetsrange from one to six feet depending upon the age andnature of the characters. Three skins are needed formaking big figures and two for medium figures. First,the artiste draws an outline with pencil or charcoal,often tracing an old puppet. For jewellery, they punchholes in the skin.Colouring of puppets is an elaborate process. Vegetablecolours were used till the middle of the 20th century, butnow chemical dyes are favoured for being cost-effectiveand easily available. The brightly painted puppets havejoints at the shoulders, elbow and the hip, all securedfor manipulation by a string. The female puppets havejoints at the waist and neck for greater mobility duringdance movements.There are two distinct styles recognizable in the AndhraPradesh puppet theatre tradition. The northern styleis prevalent in the districts of Vishakapatnam, EastGodavari, West Godavari, Krishna and Guntur. Thepuppet’s normal size is five feet and is sometimeshuman size. The southern style exits in the entireRayalaseema region, especially in the districts ofAnanthapur and Kurnool. Here, puppets are smallerand are around four feet. The northern performancestyle is more dramatic, the southern more narrative.PerformanceTraditional shadow theatre has a narrative text, whichis presented in poetic form. Neither the narrator nor thesingers are visible to the audience. Through variations inpitch, the actor gives the puppet its own voice. Andhrapuppeteers have unique modulation and styliseddelivery that sets them apart. Traditional puppeteersleave spoken words to the group leader who deliversall dialogue by changing his voice. Women, too, canlend voice for female characters. Puppet movementshave their own characteristics, like peculiar jerks thatheroic characters show, aimed at making them appearsuperior to human beings. Striking their heads againstthe ground shows intense agony and frustration.Performances begin at 9 p.m. and can conclude at 5a.m. Before the play, performers conduct ritualisticworship to Vinayaka and Saraswathi. The troupe ofshadow puppeteers consists of eight to twelve artistes.The troupe will have at least two women for singingand speaking female roles, two men for male roles,three instrumentalists for playing the harmonium,sruthi, and cymbals and one assistant who is used forquick supply of puppets and maintenance of lamps.They select an open place in the village for the stage,planting four-bamboo sticks to form a rectangle shapewith a white cloth tied to the poles. The commentatoris behind the curtain and there are a row of the lightsthat throw the shadow on the screen.The Themes of the playsThe performance draws from the epics and local legendwith raucous humor and wisecracks about currentevents. For epics, the troupe uses regional versionsof Ramayana and Mahabharata. Very rarely, theywrite new stories. Many traditional troupes are nowperforming plays on social problems like sanitation,healthcare, girl’s education, family planning andenvironment. Such scripts are generally provided byorganizations (or the government) that sponsors theshows.The scripts are usually memorized. Characters intraditional shows are recognized by voice, make-up andcostume, which remain unchanged. Comic charactersare present in all traditional plays. These characterssing and dance humorous songs bordering on theA scene from Tolu Bommalata to educate people about HIV andAids by Song and Drama Division, Government of Indiaobscene. They occasionally participate in the narrativeas secondary characters - servants in the king’s courts,attendants to king or confidantes.INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

17PerformersThere is hardly any formal training for the puppeteersin their art form. Members of the troupe gainexperience through participation in the performances.It is not uncommon for infants and toddlers to bepresent backstage during performances and providingassistance from the age of 4 or 5. Outside shows,seniors help juniors improve their ability to read andmemorize texts, often from handwritten manuscripts.All puppeteers are adept in the folk dances of theirregion, as they often dance with their puppets.Performers are mostly wandering troupes. They wanderfor nine months in a year from village to village givingperformances. The whole family will travel from tovillage to village. The villagers give some money andrice to the puppeteers.Sugrivan and Hanuman puppets on the stagelivelihoods like production of decorative lampshadesand wall hangings of leather. A co-operative puppetmakingcenter in Anantapur district helps to promotethis art form.ReferencesBellington, Michael (1988) Performing Arts: A guide topractice and appreciation, London: Burlington BooksNarayan, Shovana (2004) Indian theatre and Dancetraditions, New Delhi: Haman publishing houseBehind the screen the Puppeteers performingthe puppet show.The art is alive in some parts of the Costal Andhra andRayalaseema districts like Ananthapur (Nimmalakunta).Earlier, joint families used to travel together but todaynuclear families are also performing. Sometimes theytake their relatives or their neighbours with them.There are families that have also opted for alternatePestonji, Cherabad, (1996) et.al, Tolubommalata ofAnanthapur District, Hyderabad: NIFT publicationSaha, Paulami (2003-04) et.al, Leather Puppet show ofNarasharavpet in Guntur District, Hyderabad: NIFTpublicationSharma, Nagabhusana (1985) Tolubommalata: The shadowpuppet theatre of Andhra Pradesh, New Delhi: SangeetNatak Academy ❆OGGU KATHAOggukatha is believed to be first performed by the Kurmas (Yadavas) who devotedthemselves to the singing of ballads in praise of Lord Siva. ‘Oggu Katha’ is so namedbecause of the instrument, the ‘Oggu’, used at the beginning of each story and at themarriage festivals of Mallanna. This is derived from the folk name given to Shiva’s ‘damaruka’- it is also known as ‘jaggu’. The story narrated with the jaggu or oggu is known as OgguKatha.Oggu performers usually narrate the stories of Mallanna and Beerappa and the Shakti balladsof Yellamma. These ballads contain lyrical prose and are recited with great oratorical andrhetorical nuance.The team consists of four to six members. The main narrator wears a chain made of sevenshells, five silver rings, five silver chains, a wrist band, thick silver rings around the neck, athree - layered garland made of sapphire and round silver nooses and a garland with Mallana’sportrait on it.INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

18MEMOIRS OF A FOLK PERFORMER(Chukka Sattiah: Oggu Katha Performer)G. KUMARASWAMYG. KUMARASWAMY, Research Scholar, Department ofTheatre Arts, S.N. School, University of Hyderabad(Chukka Sattiah is a living legend who has transformedthis genre with many innovations. The following areexcerpts from his memoir).Ihave experience of more than 56 years in oggukatha.I was born in the Manikyapuram village, MiryalaGhanpur Mandal, Warangal district, Andhra Pradeshon June 15th 1936. My mother’s name is Sayamma. Myfather Agaiaha died a year and a half after my birth.Some people say that my father performed oggukathaon rare occasions in the village. My mother took care ofus with the help of my uncles. We used to have 30 to35 acres land at that time. My mother and grandmotherconducted the money lending business in the village.I started going to the fields from the age of twelve.My elder brother supervised the cattle and sheepalong with the land with my assistance, besides fourother servants. There were some breaks in my schooleducation and I had not been keen on continuing.Suddenly I desired to study again, and I joined aprivate convent school. There, for the first time I learntthe poems from Narasimha Sathakam (praises of lordNarasimha) which are 100 in number. Even today, Iremember more than 50 poems of them. I also readsome poems of Sumathi Sathakam (moral poems) afterwhich I stopped my studies.At that point, some people were searching for an actorfor the Hanuman character for Chiruthala Ramayana.They liked me and selected me for the role. I practicedit so much that I actually became a Guru (master) andstarted teaching them the drama. After that, I startedwork on Krishna Rayabharam with them but I clashedwith some people and called it off. When I was thirteenyears old, I watched Beerappa Katha (Beerappa isthe ancestor of shepherd community) at my house. Ifound it so attractive that I started practising the songsand dialogue near the well though people yelled atme. I never performed it, though. I was attracted byN.T. Rama Rao in ‘Sarangadhara’ and I practiced theSarangadhara story at night to chase away sleep whiledrawing water in the fields.Once, a performer was unable to tell the Sarangadharastory with proper diction and rhythm. So, one golla(shepherds’ caste) person asked me if I could do it.That was a big beginning - they paid me 3 rupees thatday. I used to get 75 paise for my Chiruthala Ramayanaperformance.The living legend Sri Chukka SattiahMy brother being an elder involved in solving theproblems of the people in panchayats of the villageobjected to my narrative performances. It woulddamage his image if I wear gongali (rugged woolenblankets woven by the shepherds) and perform inthe village like bards, he said. He was very angrywith me. So I did all kinds of agricultural chores andworked hard for my brother’s sake. Simultaneously, Iperformed shows also.One day I was writing and practicing a song named afterKaali Mankali Mayamma, (my mother goddess Kaali).The goddess appeared in front of me around 1 a.m. Ifell from the bed in fear. She reassured me and fed mewith her milk saying that I would be honoured like aking. It was then that I realized that my mouth hadbecome paralyzed. People came running and thoughtthat I had gone mad. From that moment till today, I findthe goddess in front of me whenever I close my eyes.After that, my story telling performances improveda lot. I just remembered everything that I saw in mychildhood. I never learned any story - I performed onstage with the story coming from my memory.Till now, I have performed 13,000 shows. Some days Iperform from morning 7 am to till night 12 pm especiallywhile I am engaged in promoting the governmentschemes and election campaigns.A workshop is going to be held this summer vacationwhere in 120 artists are going to get trained inOggukatha. No one ever taught me all this. I just learntit and practiced it on my own in my back yard.Sometimes I am forced to present Ramayana withinthe duration of half an hour. In Vijayawada, I got firstprize for this half an hour presentation of Ramayana.Nowadays, nobody is learning stories properly. Theyare just performing short versions. But Oggukatha willexist as long as god exists.INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

19For 18 years, I have been employed as tutor in TeluguUniversity and getting a good monthly salary. I startedwith Rs. 2000/- and now I am getting Rs.11, 000/- asI became old. For Oggukatha shows, we charge Rs.4000/- to 8000/- depending on the situation and capacityof the organizer.I spent much money which I got in my life for thebore wells in my land. Up to 35 bores we tried but allof them failed. Not much money is left with me now.I have two sons and one daughter. Unfortunately mydaughter passed away recently.I got honours like Savyasaachi, Kalabrahmma,Makutamleni Maharaju, Kala Samrat and JanapadaKala Murthy. A good Oggukatha narrator can supporthimself and give bread and butter to others also. Thatis what I learnt in my life. ❆EMBOSSED SHEET METAL CRAFT OFANDHRA PRADESHR. LAKSHMI REDDYR. LAKSHMI REDDY, Associate Professor, Department of LifeStyle and Accessory Design, N.I.F.T.Rangasaipet in Warangal district has long been knownfor the superb workmanship of its metal workers, theViswakarmas dating back to the great Kakatiya rulers(11th-13th centuries). These craftsmen were known for theirproficiency in stone and metal sculpture. They made vigrahasand vahanas and other accessories like crowns of the gods andgoddesses of temple and temple ornamentation.During the Nizam’s rule, metal craftsmen acquired strikinglysecular overtones and incorporated Mughal floral motifsand designs. With a decrease in the demand for traditionaland temple articles of adornment, they switched to themanufacture of articles for use in homes. They make flowerpots, vases, lanterns, shields, small stools, Mayur lamps,hanging lampshades, dasavatara shields, panels illustrating theMahabharata and Ramayana and Hindu gods and goddesses.The sheet metal products available currently mostly havereligious themes. Mementoes are the highest selling products.The Process of Metal CraftMetal sheet work involves various processes. Flat ornamentationis the earliest form of sheeting, where the sheet of brass (analloy of copper and zinc) is placed on a warm bed of lac overa wooden plank. Lac is a mixture of bee’s wax, resins castor,mustard oil and brick dust. The edges of the brass sheet arealso covered with lac. The sheet is cleaned with tamarind anddried. The design draft drawn with pencil on a tracing sheet istransferred on the sheet by engraving. The negative side of thedesign is cut away in order to give the see-through effect andthe designs are filed to make it smooth. The sheet is taken outfrom the lac by breaking it. After embossing, the final definitionis given. The sheet it is treated with nitric acid for shine andthen heated and washed. The plates made by this method areoften mounted on wooden frames.Flower pots, lampshades and drum containers are made byhollow sheeting. The sheet has to be given the shape of a hollowcontainer without any converging or diverging molding. Thepattern of the form needs to be cut into pieces and weldedtogether to bring out the form. ❆INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

20BURRA KATHA:A UNIQUE NARRATIVE FOLK ART FORMU.N. SUDHAKARUDUU.N. SUDHAKARUDU, Documentation Officer, <strong>Centre</strong>for Folk Culture Studies, University of HyderabadBurra Katha is among the popular narrative folkforms in Andhra Pradesh used extensively forsocio-political campaigns. The form is namedafter the percussion instrument, burra, that is alsoknown as budige, gummeta or dhakki.Three artistes perform. The lead singer uses thestring instrument known as tambura and the othertwo performers use the percussion instruments. Theperformers wear kurtas with tight pyjamas and turbans.The chief story teller wears hollow brass ringlets knownas andelu on his left thumb, a handkerchief tied to hisleft little finger and anklets on his feet.The Palanati Yuddham, Bobbili Yuddham, AlluriSitaramaraju and Katamraju katha narratives are someof the best known traditional performances by Burrakatha artists. Burra katha can be performed in any openor closed place with a raised platform. Performancesare largely based on written compositions where thepadyam (poem/song) becomes key to the performance.The rendition of the padyam is the marker of theability of the lead performer. The padyams act as theidentifiers of the episodes of the text or the dividersof the text into acts and scenes for the performers.The narration is done in sequential rendition of thetext with vertical formation moving back and forth inrhythmic footsteps.The other artistes are also of equal importance to theperformance. One, attired in multicoloured garb withash marks on his foreheads and seemingly distorteddemeanour, is the hasyagadu (the comedian). He isthe commentator who connects the story event, be ithistorical or mythical, with the present situations tohelp the audience relate them with life experiences.The other, attired in plain coloured kurta and turban,comments on events that are crucial to the progressionof the story. He interprets the text in verse form andconnects the events by narrating in prose.The main purpose of the performance is not only toentertain the masses, but also educate them in politicaland social stances. Burra Katha was banned in Madrasby the British government and in Hyderabad kingdomby Nizam government, because it was the medium toenlighten the people of the current political situation invarious political meetings.It is perhaps the only medium that is so widelyused by both governmental and non-governmentalGosangi- Ancestor of Cindu Madigasorganisations. The performers unlike bards are drawnfrom various castes and religions. Both men andwomen perform. ❆Danching ShivaCourtesy: http://www.chitrahandicrafts.com/products_white.htmlINDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

21PAGATIVESHALU:A FOLK THEATRICAL FORMG. BHARADWAZAG. BHARADWAZA, Lecturer, Department of Educationin Arts and Aesthetics, NCERT, New DelhiPagativeshalu is performed by hereditaryperformers belonging to the Ganayata Jangamacommunity, a sub-sect of the Saivite Jangamas.The name means ‘daytime performances’. The jangamasare divided into Ganayata Jangamas and SthavaraJangams. The Ganayata Jangams are nomadic and liveas mendicants. The Stavara Jangams are settled in oneplace and ritually considered lower than the GanayataJangamas.Though the Ganayata Jangamas are now confined tosome settlements, the performers of pagativeshaluleave their settlements around the month of Ashada(June-July) and cover certain villages and towns,performing different pagativeshalu. After spending sixor seven months as mendicants, they return to theirsettlements in Chaitra (March-April).The performers have no particular patron communityto depend on. All villagers watch the performances,while the performers target the rich landlord as theirmost lucrative audience. After a series of performancesthat could be as many as thirty-two over a month-longperiod in a village, they move on to the next village.After the zamindaries collapsed, the pagativeshalu hasshrunk to sixteen days. Performers are also turningtowards market places as performance locations.The texts of Pagativeshalu are orally transmitted anddiffer among groups with different areas of operation.The performers refer at least thirty-two such texts asPagativesham texts. The texts can be classified accordingto theme into four major types - those narrating originsof castes comprise more than half of all texts. Mythology,religion and texts lampooning Islam form about onethirdof all texts and the remainder connected mostlywith humor and magic.The performances of Pagativeshalu reflect societalgroups and their attitudes in a satirical way, makingthem aware of how each group is relevant to the other.Caste-based themes dominate.Six to nine performers including musicians comprisethe troupe. The pagativeshalu is structured on amonologue or dialogue. Satire and song is usedextensively. Each vesham is performed during theday starting between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m. and endingbetween 4 p.m. and 5 p.m. Stories are structured togive performers scope to extend the performance whilemoving from one house to the other or one street toother. The structure of the tale itself is fragmented asunits and episodically presented at each performancespace during the itinerary.A levy of two rupees per hundred rupees collectedis imposed by the community. It is utilized as acorpus fund of the association for the welfare of thesettlements. Earlier, two more rupees were collectedfrom the revenue and given to old people who used toperform. Another levy is imposed on every household,termed ‘jole pannu’(earning by begging). Collected atthe rate of half rupee to one rupee, it is paid to theMatadhipahthi at Shamshabad when the communitiesof performers visit Srirangapuram in Mahaboobnagardistrict. The Matadhipahthi settles disputes amonghouseholds in the community.ReferencesAbrahams D, Roger (1977) Toward an enactment - centraltheory of folk-lore: Frontiers of <strong>Folklore</strong>, ed. William Bascom,Boulder: Western Press for the AAASBauman, Richard (1977) Verbal Art as Performance, Mass:RowleyDerrida, Jacques (1967 r. pt. 1998) “There is nothingoutside of the text”, Writing and the difference. London:Routldge and Kegan PaulGargi Balwant (1966) Folk Theatre of India. Washington:University of Washington Publication on Asian ArtsRicoeur, Paul (1970) The Model of the Text: Meaningfulaction considered as Text: Social Research, U.S.A.: Rabinowand Sullivan.Sarma, M.N (1995) Folk Arts of Andhra Pradesh,Hyderabad: P.S. Telugu UniversitySundaram, R.V.S (1976) Janapada Sahitya Swaroopam,Bangalore: Janapada Vignana Samithi Publication.Thurston, Edgar and Rangachari, K. (1909 r. pt. 1987)The Castes and Tribes of Southern India, New Delhi: AsianEducational Services. ❆INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

22SURABHI THEATRES:A LEGACY TO CONTINUEJOLY PUTHUSSERYJOLY PUTHUSSERY, Department of Theatre Arts,S. N. School, University of HyderabadSurabhi is the only theatre group hailingfrom a single family. According to oralhistory, the origins of the group aredated to 1860 AD in Maharastra. The ancestorsof the Surabhi family were associated withKing Sivaji’s court. Some families migrated toAndhra. It is said that the family of VanarasaGovinda Rao selected the Sorugu village astheir temporary resort and changed its nameto Surabhi in 1885. Govinda Rao, a leatherpuppeteer, set up a travelling theatre groupand named it after the village. Over more thana century, Surabhi’s unique family traditionlives on.All roles are played by members of the Rao’s familywho belong to the Maharashtrian lineage and share thefour family names Vanarasa, Aveti, Aatok and Sindhe.Govinda Rao’s 13 children and grandchildren formedtheir own troupes. In its heyday around 1972, Surabhihad 2,000 artistes and 46 troupes. Lean times followedas Telugu cinema and television weaned audiencesaway. Today, 200 artistes and four active troupes - SriVenkateswara Natya Mandali, Sharada Vijaya NatyaMandali, Bhanodaya Natya Mandali, Vinayaka NatyaMandali – remain. The mythological forms the staple oftheir repertory, with Lav Kush, Maya Bazaar and BalaNagamma being perennial favorites. Rural audiencesthrong the theatres where Rs. 20 fetches a chair seat andhalf the sum a spot on the floor. Ghatotkacha swallowingladdus that come flying towards him, Ganga springingup from the ground, Narada descending from the skies,arrows flying in the air and lamps lit by the them anda large white key making its way across the stage onits own to reach the lock on the prison door are amongthe special effects that Surabhi’s innumerable theatretechnicians have produced.Behind the proscenium curtain, acts and scenes areset up like a deck of cards. Each scene within an actmaterializes by dropping curtains with distinctivepainted locales that descend vertically or are flowndown from the flies onto the stage. The generalizedbackdrops include forest, garden, street, palace ordurbar, antapura (women’s quarters), perhaps a cavescene (Specially for Surabhi’s enormously popular‘Mayabazaar’), and heaven. Curtains answering tocurrent performances have more parks (for “lovescenes”) and streets with modern buildings inperspective painting. The narrative is grounded by theatmosphere produced by the curtains and, on the otherhand, the world of romance and dream is released,indeed made practicable, only through their presence.For all its attractions, Surabhi was beginning tobore the audiences. There was nothing new in theirrepertoire to offer and, most often, other groups hasextensively hired their technicians and over-used theSurabhi masterpieces in many historical verse anddance dramas in the country.Just when it seemed that Surabhi’s disbanding wasimminent, cultural enthusiasts like GarimmellaRamamurthy and Ramanachari pitched in and triedto find help from different sources. <strong>National</strong> School ofDrama asked acclaimed musician-director B.V. Karanthto invigorate Surabhi with new theatre techniques.Karanth realized the only way to salvage the group’stradition was to put it in sync with contemporary reality,blending the old with the new. In his own words,“Typical characteristics like bright costumes, glitteringINDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008

23crowns and artistic cut-outs will, however,remain.” (Director’s note for Chandi Priya).Unfazed by the tepid response to earlier attempt‘Bhishma’, Karanth next produced Chandi Priyain 1997, dealing with female infanticide. In 1998,third production ‘Basti Devata Yadamma’, anadaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s The Good Womanof Setzuan’, ran to a packed auditorium inHyderabad. It did not do well with the ruralaudiences though. The Surabhi Paparos play onShridi Sai Baba was thriving with many showsand touring extensively across the Teluguspeakingregion.Rising costs threaten the very existence of thetroupes. Government repertory grants andaccommodation at the artist’s colony has notmade the performer’s life smooth. They are paida paltry Rs 1,500 to 2,000 a month. But the playsgo on. The fact that Surabhi has survived for so longspeaks volumes for the resilience of Govinda Rao’ssuccessors. The members of the group hope to regainits former glory and keep that leather puppeteer’slegacy alive. ❆NATIONAL <strong>FOLKLORE</strong> SUPPORT CENTRE’SNEW INITIATIVES1. NFSC’s Portal for Journals:http://indianfolklore.org/journals/The NFSC Portal for Journals in Indian <strong>Folklore</strong> andallied disciplines would give scholars a means ofobtaining peer review and constructive criticism, andpublish articles and journals for the free use and benefitof the community of students, scholars and teachersdevoted to higher education in humanities and socialsciences. Works can be submitted after registration ineach of the journals listed here and the draft markedfor inclusion in the critical peer review process. Withsuccessful passage through this stage, the articlecan then be published in the journal of choice. Thejournals listed and published in the NFSC portal havean editorial board, theme and specific policy guidelinefor accepting articles. This publication system usesOpen Journal Systems where editors can configurerequirements, sections, and the review process. TheSystems enable online submission and managementof all content, subscription with delayed open accessoptions, comprehensive indexing of the content part ofglobal system, email notification and ability to commentfor readers and complete context sensitive online helpsupport.Journals hosted till June 2008Tuluva is a peer reviewed academic journal edited andpublished by the faculty of the Regional Resources<strong>Centre</strong> for Folk Performing Arts, Mahatma GandhiMemorial College Campus, Udupi, Karnataka.Submissions should be addressed to H. Krishna Bhat,Director, Regional <strong>Centre</strong> for Folk Performing Arts,MGM college campus, Udupi, Karnataka-576102Email: mgmcollegeudupi@dataone.inNamma Janapadaru is an academic bilingual journaldevoted to the study of Kannada literature, cultureand folklore. The journal invites articles in English andKannada. Request for online/manuscript submissionsshould be addressed to M.N. Venkatesha, Editorin Chief, Namma Janapadaru, Assistant Professor,Department of <strong>Folklore</strong> and Tribal Studies, DravidianUniversity, Kuppam, Andhra Pradesh.Email: mnvenkatesh2003@rediffmail.comLokaratna is the official journal of the <strong>Folklore</strong>Foundation, located in Bhubaneswar, Orissa.Lokaratna is a peer-reviewed academic journal inOriya and English. Request for online/manuscriptsubmissions should be addressed to Mahendra KumarMishra, Editor in Chief, Lokaratna Managing Trustee,<strong>Folklore</strong> Foundation, A-28, BJB Nagar, Bhubaneswar,Orissa- 751014Email: mkmfolk@gmail.comJournal of the <strong>Folklore</strong> Research Department is a peerreviewedacademic journal edited and published by thefaculty of the <strong>Folklore</strong> Research Department of GauhatiUniversity, Gauhati, Assam, India. Request for online/INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.29 JUNE 2008