38 El Palacio - El Palacio Magazine

38 El Palacio - El Palacio Magazine

38 El Palacio - El Palacio Magazine

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

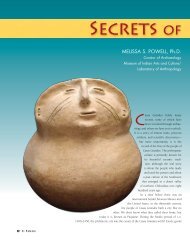

Hornacina, ca. 1870,attributed to H. V. Gonzales.Tin-plate and glass, housingminiature bulto ensemble.31.5 × 14.5 × 13.75 in.Bequest of Charles D. Carroll,Museum of InternationalFolk Art, DCA(A.1971.31.136).Opposite: Detail ofdeer track punch,a unique design motifattributed to H. V. Gonzales.Photos by Blair Clark.<strong>38</strong> <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong>

first visited the collections of the Museum of International Folk Art inthe early 1970s during a spectacular August rainstorm. Of the treasuresbeyond number, one piece in particular laid claim to my psyche and soul.Magnificent and complex, the work is composed of scrap wood, thin sheetsof glass, recycled tin containers, and an assemblage of twelve miniature bultos(sculptures of saints) with accompanying accoutrements.A circa 1870 hornacina (glass-walled niche), thepiece is unique, ambitious, and expertly crafted,an anomalous curiosity in the realm of NewMexican folk art. It has been exhibited severaltimes, initially at the Palace of the Governors inJanuary 1953. Most recently, in 2007– 2008, itwas the focal point of an exhibition, PersonalShrines and Home Altars, curated by Santa Fesantera (saint maker) Marie Romero Cash in the Museum ofInternational Folk Art’s Hispanic Heritage Wing.The tableau of miniature bultos housed within the tin-andglassstructure has for decades intrigued scholars, includingthe esteemed late E. Boyd, the museum’s Spanish Colonialcurator from 1951 to 1974. Of more than twenty tin worksdescribed in her article, “New Mexican TinWork,” in the February 1953 edition of <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong>,Boyd devoted the most space and descriptionto this work, titled <strong>El</strong> Gran Poder de Dios (TheGreat Power of God). Fifty-seven years later,Boyd’s concise summation of the piece remainsinsightful: “Part of the framework of wood is ascrap of a trunk or travelling box with printedpaper lining such as was common 1850–1860. It is probable,because the composition is perfectly fitted to the container,that the entire group was made at the same time.” While thearticle addresses the possible stylistic origins of the bultos,neither Boyd (nor anyone since) has ever positively attributedthem to a recognized santero.39 <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> 39

When Lane Coulter and I prepared our inventory ofmuseum collections for the study that ultimately resulted inNew Mexican Tinwork 1840–1940, we regrettably chose notto include the hornacina in our discussion of nineteenthcenturyNew Mexican tinwork. Since my initial encounterwith the piece, however, I have remained convinced that ithas an interesting tale to tell.Aside from the charming bulto assemblage,the superbly crafted tin-and-glass structurereveals the hand of an artisan highlyskilled in the craft of tin working, onewho possessed a large inventory oftools, as reflected in the assuredassembly and sophisticated stylingof the piece. Regrettably, the hojalatero(tinsmith) carefully avoided using theembossed portions of the recycled tincontainers, whose information wouldhave been useful in dating the folk artmuseum hornacina and other works. Thelarge pieces of glass incorporated into themuseum piece, as noted by Boyd, precludea date earlier than circa 1860. Like Boyd, oneis tempted to read into the decorative patternsembossed onto the tinplate the subtleties of Christianiconography. However, it is the technical aspects of the tinsmith’swork that are of greatest importance when considering thismaster artisan’s vast repertoire.Examination of the structure’s tin-plate surface revealsthe use of six decorative punches or dies. The embeddedimpression of one in particular appears only twice on thehighly ornamental tin-plate components. That one punch,however, is unique and unmistakable in the entire repertoireof nineteenth-century New Mexican tinwork.Simply fabricated from a one-quarter-inch round iron rodwith a notch deeply filed through its center, the newly mintedpunch resulted in two opposing half-moons. In the process offiling the notch, the tinsmith removed more metal from oneportion of the notch than the other, creating a splayed set ofhalf-moons that, when imprinted into the tin-plate’s surface,resembles a cloven hoof; thus the appellation, “Deer Track.” Thisunique imprint is visible on the museum hornacina as a subtleaccent at the tip of each of two opposing elongated hearts thatdecorate the large central crest mounted above the glass door.Mere weeks before New Mexican Tinwork 1840–1940 was to goto print, Coulter and I were apprised of the existence of a signednineteenth-century hornacina. Although interesting, the workwas minimally adorned with punched ornamentation, and morenotable for its signature and accompanying informationthan for its artistry. Still, I felt we were witness tothe work of an important New Mexican artisan.In the book’s brief discussion of this signedwork, we indicated the possibility that theartist might be responsible for many ofthe other unsigned tinwork examplesdiscussed in the book. Today, I believethat the artisan responsible for thesigned work—H. V. Gonzales—alsocrafted the museum hornacina thatcaptured my attention so long ago.iginio Valentín Gonzaleswas a gifted, multitalentedindividualwhose contributions tothe material culture of New MexicoPortrait of H. V. Gonzales, remain largely unknown to thecirca 1895, John Donald academic community and the greaterRobb Collection. Image from public. Gonzales’s artistry went beyondHispanic Folk Music of New tinsmithing. His musical and poeticMexico and the Southwest: artistry was first noted in 1946 byA Self-Portrait of a People, University of New Mexico professorby John Donald Robb.and musicologist John Donald RobbCopyright © 1954 bywhile documenting the disappearingUniversity of Oklahomafolk music of New Mexico and southernPress, Norman. Reprinted byColorado. In Abiquiu, Robb recorded apermission of the publisher.popular nineteenth-century corridoAll rights reserved.Photo by Blair Clark. (ballad) sung by the blind singer JoséGallegos. Subsequent to the recording,Robb learned the name of its composer,H. V. Gonzales. Now recognized as the earliest known NewMexican corrido, “La Muerte de Antonio Mestas” recounts theevents of July 5, 1889, when a young Rio Arriba County ranchhand rode off to tend the livestock of a large international consor-40 <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong>

Nicho with deer trackpunch, ca. 1875,attributed to H. V.Gonzales. Tin-plate andglass. 28 × 21 × 5.5 in.Private collection.Photo by Carolyn Wright.41 <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong><strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> 41

tium, the English Ranch. Thrown from his horse and killed, hisbody was discovered two days later in the remote wilderness ofMogote Mesa. One of the twenty-four stanzas (translated by Robbhere) illustrates Gonzales’s skillful literary styling:6. Mi Diós, que todo lo mira But God who watcheth and knowethy todo pone en acuerdo, The thing that the searchers seek,orillas de una colina Caused a crow who stood onhizo que gorjeara un cuervo the hilltopdiciendo: Aquí está tu siervo These bitter words to speak:entre esos zacatonales, Below me lies your servanthombres, sean razonales, Among the grasses tall;observen lo que yo observo. Observe the thing that I see,It’s here your friend did fall.Subsequent to the documentation of the corrido, Robb recordedor documented nearly a dozen songs and alabados (hymns ofpraise) written by H. V. Gonzales between 1889 and 1911. Theirthemes range from the ravages of malaria (“La Enfermedad de losFríos”) to missing female companions (“La Severiana”) to a plaintivelamentation on the death of his stepdaughter (“Margarita”).Born in Santa Fe in 1842, Gonzales, fondly known as “Ginio,”was the youngest child of the Juan Candelario Gonzales family.The Gonzales home, next door to that of the prominent businessmanand political figure Céran St. Vrain, was near theplaza, the city’s hub of religious, political, and social activity. Itwas an ideal place for a precocious youngster to witness territorialhistory in the making. How Gonzales was educated andby whom is unknown, though he was literate in Spanish andCajita with nameJ. Atilano Suaso(detail below),circa 1881, attributedto H. V. Gonzales.Tin-plate, glass, paper.9 × 12.5 × 6 in.Private collection.Photo byCarolyn Wright.42 <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong>

English, with impeccable penmanship and keen observationskills. By July 5, 1861, when the nineteen-year-old Gonzalesjoined the Union Army as a member of the 2nd New MexicoVolunteers, he was also a trained tinsmith.On February 21, 1862, Gonzales found himself at the bloodyand controversial Battle of Valverde, though he was sparedinjury. His life in the military was punctuated by several accusationsof misconduct. Nonetheless,he rose in rank from privateto sergeant, serving in the armyuntil September 1866. The greaterpart of his military career was spentworking in the US government’sforced removal of Native Americantribes from the plains of easternNew Mexico and West Texas.Upon returning to civilian life,Gonzales, his young wife Maríade los Reyes (Ortega), and theextended Gonzales family tookup residence in the Spanish villageof San Ildefonso in the PojoaqueValley. There he resumed histrade as a “tinner,” probably asan itinerate craftsman travelingthroughout northern and centralNew Mexico, as evidenced by the numerousworks bearing his distinctive stylistic signature.Collection data pertaining to these works is widespreadand corroborated by anecdotal statements by individuals interviewedby Robb in the 1940s, who commented on Gonzales’speripatetic adventures.Following the apparent death of María, sometime between thebirth of their youngest daughter, Abagail (sic), circa 1874 andNovember 1878, Gonzales married a second time. He becamestepfather to six additional children, the oldest of whom marriedin 1881. That wedding probably inspired Gonzales’s creation ofa delightful cajita (notions chest) bearing the stepson’s name,J. Atilano Suaso. Painstakingly crafted, masterfully detailedtinwork forms the supporting armature for the glass-walledchest. Sandwiched between the armature and the glass arepieces of paper bearing intricate floral imagery so expertlydrawn and colored that the casual observer often assumesthem to be scraps of commercial wallpaper.Gonzales’s choice to create his own decorative paper ratherthan rely on readily available wallpaper, as well as the variouspunches he chose to adorn the cajita’s tin structure, can bedirectly linked to a marco (tin frame) with no fewer than ninetysixDeer Track impressions deeply embedded into its tin-platesurface. The frame contains adrawing of a popular NewMexican saint, San Cayetano,whose image and accompanyingattribution are achieved withmeticulously drawn lettering.This drawing, illustrated in NewMexican Tinwork 1840–1940, hasa counterpart in another drawingof a lesser-known saint, SantaEduvigis-Viuda, that bears H. V.Gonzales’s signature and a placeof origin—San Ildefonso. Twoprincipal figures surround thissaint, while in the backgroundtwo diminutive figures peer outfrom behind the bars of a jailcell. The figures in this work, theframed image of San Cayetano,and five other devotional imageson paper by Gonzales are allSt. Eduvigis Viuda, by Hig. V. characterized by startled, wideeyedfacial expressions and dark,Gonzales (signed), ca. 1885.Water-based pigments on paper, heavy eyebrows. In turn, thesenewsprint. 10 × 8 in. Collections characteristics are similar to theof the Spanish Colonial Artsfacial expressions of the carvedSociety, Museum of Spanishfigures housed within the freestandinghornacina at the folkColonial Art, Santa Fe (1970.9).Courtesy Museum of Spanishart museum.Colonial Art. Photo byAccording to notes by Boyd,Blair Clark.the hornacina’s ambiguous title,<strong>El</strong> Gran Poder de Dios, was given to the work by the owner fromwhom the piece was originally purchased. A more accurateinterpretation of the iconography suggests the subject actuallyrepresents the Miraculous Mass of St. Gregory the Great.43 <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> 43

Legend has it that an image of the suffering Christ appearedabove the altar one day while Pope Gregory (AD 590–604) wassinging the Mass. Transubstantiation was a popular subject ofthe Counter-Reformation, and many European artists of the eraoffered various interpretations of the legendary event. As thesubject is an uncommon theme in New Mexican santero art,a nineteenth-century print of a Counter-Reformation paintinglikely inspired the carved and painted ensemble encased in tin.Although roughly carved and loosely painted, the ensemble bearsa sophisticated sense of design and composition with inventiveflair, setting it apart from other contemporaneous santero works,a quality noted nearly thirty years ago by Marie Romero Cash.“This magnificent piece, which combines the use of tin andwood, has fascinated me for years because it represents the finestexample of the early santero pushing the envelope and creatingsomething that went beyond the norm,” Romero Cash said. “Itvalidated my own work as a santera, giving me courage to creatework that moves beyond simple creativity.”The most curious yet charming aspect of the ensemble is theseated figure possibly representing God. Scantily clad and seatedin a relaxed position with legs crossed and arms outstretched,the figure does not conform to more common images of theall-powerful deity. Six hovering angels contribute to the sublimescenario, while the diminutive figure of Nuestra Señora de losDolores (Our Lady of Sorrows) suspended in the darkness aboveadds a touch of pathos. Except for a few discrepancies, the piececlosely conforms to the iconography of fifteenth- and sixteenthcenturyEuropean paintings: a pair of tall tapers, the open missal,the cross above the altar (in this instance, a complete crucifix),and the tonsured figures of Pope Gregory and his attendantpriests attired in chasubles. The three figures are presently facingaway from the altar, contrary to standard iconography. This maybe a result of their having been stolen during the 1953 exhibitionat the Palace of the Governors; when returned, they were erroneouslypositioned in reverse order. At the time of the theft, theHost, previously held by the central figure of the Pope, was lost.The seated figure is a representation of the suffering Christsuspended by angels as he descends to present himself at theconsecration of the Mass. The bloodied rib cage, the raw, scuffedknees, and the beard are similar to that of the crucified figurepositioned atop the altar. The figure of Christ, with welcomingoutstretched arms, and the presence of the sorrowing Virgin haveprecedence in several renditions of the subject. Perhaps the artist’sdecision to represent Christ with legs crossed was in the interestof modesty and only appears charming to the modern viewer.Finally, the four “totemic” columns of cherubs, as noted by Boyd,display a distinct Renaissance character. Also noted by Boyd is thepredominance of earth-red and yellow-ocher pigments, a colorpalette repeatedly used to decorate the surfaces of numerous tinworks by H. V. Gonzales.While the stimulus for the piece’s creation is unknown, thehornacina is an important contribution to the inventory of greatnineteenth-century New Mexican artistry. Was H. V. Gonzales, thetinsmith, also the santero responsible for the carved-and-paintedensemble? Without a signature, the answer is not forthcoming.Romero Cash, who is perhaps most intimately familiar with thework, is certain the ensemble was carved circa 1820–1830, whileBoyd noted the influence of the Laguna Santero (who was active inNew Mexico between 1776 and 1815). Ultimately, a concentratedscholarly study is required to determine if the tableau was crafted bythe same remarkable hand that made its tin-and-glass exterior.*onzales was a busy man. Not content to be a mastertinsmith and composer of song and verse, he wasalso a schoolteacher, teaching New Mexico youthfrom Pojoaque to Las Vegas, and concluding thiscareer in Canjilón. His personality and methods of teaching musthave been impressive; several individuals interviewed by Robbin the 1940s vividly recalled their childhood under the tutelageof maestro (teacher) Gonzales.Gonzales’s literary contribution to the intellectual heritage ofthe territory’s Spanish-speaking population lay in the copiousoutpouring of poetry he composed and published between thelate 1800s and his death. Among other places, he publishedin the Las Vegas, New Mexico, Spanish language newspaper,La Voz del Pueblo, where he served as asistente (assistant) to thesecretaria de redacción (literary editor) from September 1897 toSeptember 1898. No subject was too prosaic or too grand forGonzales. He wrote of a serious drought afflicting the land andthe people in 1899. He was unflinching in his commentary onthe ethnic tensions between the native Spanish population (“LosMejicanos”) and the interlopers (“Los Americanos”). Numerousdevotional poems of profound solemnity were followed bysecular poetry reflecting a recurring personal theme: the female44 <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong>

mystique. At the same time, as in the sixth stanza of the poem“Oremus,” he proudly waved the banner of nationalism, composingtimely poetry relating to the entry of the United States intoWorld War I.OREMUSLET US PRAYPaciente . . . el Tío Samuel, Patiently . . . Uncle Sam,Sobrellevaba el conflicto; Waited out the conflict;Y obligado pegó el gritoBut when forced to do soDe guerra contra el infiel; Gave out a battle cryY al Kaiser tiranoAgainst the infidel;<strong>El</strong> Norte AmericanoAnd thus, around the throatLe ajustará la correa.–Of the tyrannical Kaiser,The North AmericanWill tighten the noose.June 10, 1918, <strong>El</strong> Nuevo Estado, Tierra Amarilla(Translation by Alejandro López)Higinio V. Gonzales died on August 12, 1921. By the 1940s onlya few individuals remembered his contributions to New Mexico’svibrant Spanish culture of the 1800s. In an article in 1973, Robbplaintively noted the need to recognize this nineteenth-centuryartistic titan:“In his day, a man of influence among his people in the Española,New Mexico, area, he recorded in his poems and songs, as even thisfragmentary record shows, the pre-occupations and emotions of thedaily life of his people during the approximate period when NewMexico broke away from first Spanish and later Mexican dominationto become first a territory and later a state. His memory endures inhis writings which are worthy of more than this limited essay.”In this, the cuartocentenario (400-year anniversary) of thefounding of Santa Fe, it is fitting that Gonzales’s mastery berecognized at last. The vast amount of tinwork that Gonzalesproduced is an unprecedented and irreplaceable contribution toNew Mexico’s material culture. For this, as well as his vast literaryachievements, Gonzales should be accorded his rightful place inthe pantheon of New Mexico’s most notable citizens. nMaurice M. Dixon Jr., BFA, MFA, is coauthor with Lane Coulter of New Mexican Tinwork:1840–1940 and an accomplished tinsmith. He is currently at work on a book about thelife and art of Higinio V. Gonzales. To see sources and more H. V. Gonzales poetry, andto read E. Boyd’s 1953 article, “New Mexican Tin Work,” visit elpalacio.org.45 <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong>Tin works (frame and nicho) attributedto H. V. Gonzales. Top: Santa FeFederal/Neoclassical Frame,ca. 1865 – 85. Tin-plate, glass. 26 × 20in. Print: Currier and Ives image of St.Louis not original to frame. Collectionsof the Spanish Colonial Arts Society,Museum of Spanish Colonial Art,Santa Fe (61-66).Bottom: Rio Arriba Painted Nicho,ca. 1865 – 85. Tin-plate, glass. 21.5 ×20 × 5 in. Bequest of Alan and AnnVedder. Bulto of St. John Nepomuk byA.J. Santero. Collections of the SpanishColonial Arts Society, Museum ofSpanish Colonial Art, Santa Fe (90-44).Photos by Jack Parsons, courtesyMuseum of Spanish Colonial Art.<strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> 45

H.V. Gonzales PoetryADIOSBy H.V. GonzalesADIEUAhora solamenete pido,De tu divino poder,Que me quieras conceder<strong>El</strong> que llegue arrepentido:Con mi corazón partido,Llore, llore, sin cesar;Y al pie de tu santo altarHaga buena confesiónY reciba la comuniónAntes de irme a retirar.All that I ask now,From thy divine grace,Which you might concedeIs that I arrive repentant:With my heart rent into,I have wept and wept without end;And at the foot of thy holy altarI might confess thoroughlyAnd receive communionBefore from this world I depart.April 17, 1897, La Voz del Pueblo(Translation by Alejandro López)A LA BELDAD MEJICANABy H.V. GonzalesMEXICAN BEAUTYEn Francia hay damas muy bellasY lindas cual azucenas;Tambien hay muchas morenasCon sus ojos como estrellas;Tuve allí varias querellas,Y trate con las Prusianas;Fueron conmigo tiranas,Varias veces amorosas:Pero aunque sean hermosas,Prefiero a las Mejicanas.In France there are a great many beauties,Each as lovely as the pure white lily;While starry eyed dark beauties also abound.Yet, I have only complaints to air about them;I enjoyed the Prussian women,Tyrannical as they were toward me,At times loving and at times not.And yet, as beautiful as they may be:As for me, I prefer the Mexican women.August 28, 1897, La Voz del Pueblo(Translation by Alejandro López)46 <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong>

SourcesCarmen Espinosa, “Foreword,” New Mexico Tin Craft, Santa Fe: New Mexico Department ofVocational Education, Department of Trades & Industries, June 1937.E. Boyd, “New Mexican Tinwork,” <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong> 60 (February 1953): 61–66.Lane Coulter and Maurice M. Dixon Jr., New Mexican Tinwork 1840–1940, 128–31, Albuquerque:University of New Mexico Press, 1990.John Donald Robb, Hispanic Folk Music of New Mexico and the Southwest: A Self Portrait of a People,52–57, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1954.Robb, Hispanic Folk Music, 320–22, 328–30, 398–99.1850 US Census, City of Santa Fe, New Mexico Territory, enumerated December 12, 1850.Compiled service records of volunteer Union soldiers who served in organizations from theTerritory of New Mexico, US National Archives (microfilm).Notes recorded during field trips prior to the publication of Hispanic Folk Music, John DonaldRobb Archive, Southwest Research Center, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.Coulter and Dixon, New Mexican Tinwork, fig. 5.7, 65.E. Boyd, Accession Record A.71.31-1/209, Museum of International Folk Art, Santa Fe.Accession record A.71.31-1/209, Museum of International Folk Art, Santa Fe..Anselmo F. Arellano, Los Pobladores: Nuevo Mexicanos y su Poesía, 1889–1950, 57–74,Albuquerque: Pajarito Publications, 1976.Robert J. Torrez, “Christmas in Canjilon,” La Herencia 60 (winter 2008).John Donald Robb, “H. V. Gonzales: Folk Poet of New Mexico,” New Mexico Folklore Record 13(1973–74): 1–6.47 <strong>El</strong> <strong>Palacio</strong>