Qué Pasa, OSU? - go to site

Qué Pasa, OSU? - go to site

Qué Pasa, OSU? - go to site

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

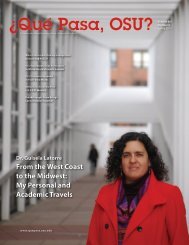

Arroz con LecheAn Interview with Children’s Book Author/Illustra<strong>to</strong>r Lulu DelacreBy Verónica Betancourt, PhD Student, Arts Administration, Education, and PolicyLatino children’s literature has flourishedover the last three decades. In this interviewwith my mother, author/illustra<strong>to</strong>rLulu Delacre, we discuss her work and thefield since the 1980s. Born and raised inPuer<strong>to</strong> Rico, Delacre began publishingbooks inspired by her Latino heritage withArroz con Leche: Popular Songs and Rhymesfrom Latin America. The way she tells it, sheneeded a book <strong>to</strong> use <strong>to</strong> sing me <strong>to</strong> sleep;since that moment in the nursery, her publicationshave spanned from picture books<strong>to</strong> young adult novels and explored thediversity of Latinidad as lived in the U.S. andLatin America.VB: How did you pitch your idea <strong>to</strong> do apicture book focused on Latino children’ssongs and games?LD: Back in 1987 I had already authoredseveral titles with Scholastic, Inc. and had a<strong>go</strong>od relationship with my edi<strong>to</strong>r. Arroz conLeche: Popular Songs and Rhymes from LatinAmerica was the first of a series of books thatcelebrate my mother language and culturalheritage. In defending my proposal over thephone, not only did I speak with passionand conviction about the need for a Latinoequivalent of Mother Goose Rhymes, butI also sang every single song in the collection—addingliteral translations along theway. It was unfair that none of my childhoodrhymes had been published in a picturebook format while hundreds ofillustrated versions of MotherGoose Rhymes were available<strong>to</strong> the mainstream market. It<strong>to</strong>ok a visionary edi<strong>to</strong>r, and ahouse that looked in<strong>to</strong> the percentageof Latino children inthe public schools at the time,<strong>to</strong> publish my title.VB: What was the Latino children’sbook community likewhen you started publishing?LD: There were a few Latinoauthors dispersed throughoutthe States, but no organizationor coalition where I could meetthem. That said, two encouraginginstances stand out in my memory. Thefirst came in the mail. It was an unexpectedpackage from Nicholasa Mohr with words ofpraise for my work. The second happened ata panel of authors at the Virginia Hamil<strong>to</strong>nConference; I was invited <strong>to</strong> participatealong with Arnold Adoff and Ashley Bryan.A bit intimidated by their stature, I realizedthat the best I could do was <strong>to</strong> speak fromthe heart. So I began my talk with a songfrom Arroz con Leche. The reward came atthe end when Ashley Bryan looked at metenderly and whispered, “Keep on singing.”VB: How have you experienced the growthof Latino children’s literature?LD: I think it’s fabulous that we nowhave many more and varied voices. Thisallows room for choice among readers.Government funds for programs throughthe 1988 amendment <strong>to</strong> the BilingualEducation Act, and long awaited recognitionhave increased the interest in this literature,prompting larger houses <strong>to</strong> jointhe efforts of smaller and dedicated multiculturalpublishers like Children’s BookPress and Lee & Low Books. In the 1990sThe Américas Award from the Consortiumof Latin American Studies Program, and theAmerican Library Association Pura BelpréAward were established. For the first time,major awards recognized quality children’sliterature written for/by Latinos.VB: What do you consider when creatingLatino characters?LD: All my characters are first and foremosthuman, behaving according <strong>to</strong> their personalities.What makes them Latino is thattheir cultural upbringing may very well playa role in their reaction <strong>to</strong> a situation. I strive<strong>to</strong> create characters and s<strong>to</strong>ries that dealwith universal themes in childhood whilestill being intrinsically Latino.In recent years I have become interestedin the trials of young Latinos growing upin the United States, in part because ofthe s<strong>to</strong>ries I’ve witnessed and heard fromfriends, acquaintances, and schoolchildren.For example, I set Arrorró mi niño: LatinoLullabies and Gentle Games in the continentalU.S. in part because I wanted <strong>to</strong> dispelthe misconception that all Latinos in theUSA are brown skinned and only work inthe fields. The illustrations show diverseLatinos of many shades and settings likethe public library or art museum.VB: What do you find most encouraging inthe field of Latino children’s literature now?LD: The advent of the internet has openedup channels of communication that did notexist before. Blogs like TheLatinoAuthor.com or Pat Mora’s Bookjoy make Latinotitles accessible <strong>to</strong> parents and educa<strong>to</strong>rsthat can look for them. It is noteworthy thatmany more voices have joined the chorusof Latino authors and illustra<strong>to</strong>rs. Despitethis growth, the efforts by major publishers<strong>to</strong> acquire manuscripts ebb and flow. Bighouses expect very strong sales in the firstyear and this may not be always the casewith Latino literature since it tends <strong>to</strong> takelonger <strong>to</strong> reach its intended audience. Weneed <strong>to</strong> find ways <strong>to</strong> publicize Latino literaturebroadly so it becomes as accessible asmainstream literature. In my view it is ripefor the limelight.For more information on Lulu Delacre andher work please visit www.luludelacre.co24