Hatching success in Yellow-wattled Lapwing Vanellus ... - Indian Birds

Hatching success in Yellow-wattled Lapwing Vanellus ... - Indian Birds

Hatching success in Yellow-wattled Lapwing Vanellus ... - Indian Birds

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

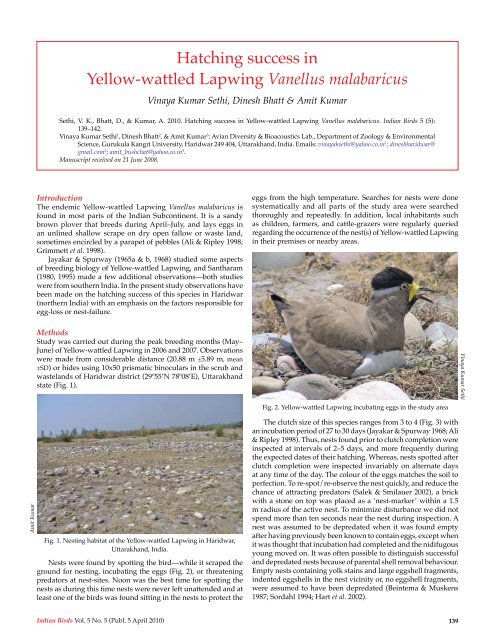

<strong>Hatch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>success</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Vanellus</strong> malabaricusV<strong>in</strong>aya Kumar Sethi, D<strong>in</strong>esh Bhatt & Amit KumarSethi, V. K., Bhatt, D., & Kumar, A. 2010. <strong>Hatch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>success</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Vanellus</strong> malabaricus. <strong>Indian</strong> <strong>Birds</strong> 5 (5):139–142.V<strong>in</strong>aya Kumar Sethi 1 , D<strong>in</strong>esh Bhatt 2 , & Amit Kumar 3 : Avian Diversity & Bioacoustics Lab., Department of Zoology & EnvironmentalScience, Gurukula Kangri University, Haridwar 249 404, Uttarakhand, India. Emails: v<strong>in</strong>ayaksethi@yahoo.co.<strong>in</strong> 1 ; d<strong>in</strong>eshharidwar@gmail.com 2 ; amit_bushchat@yahoo.co.<strong>in</strong> 3 .Manuscript received on 21 June 2008.IntroductionThe endemic <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Vanellus</strong> malabaricus isfound <strong>in</strong> most parts of the <strong>Indian</strong> Subcont<strong>in</strong>ent. It is a sandybrown plover that breeds dur<strong>in</strong>g April–July, and lays eggs <strong>in</strong>an unl<strong>in</strong>ed shallow scrape on dry open fallow or waste land,sometimes encircled by a parapet of pebbles (Ali & Ripley 1998;Grimmett et al. 1998).Jayakar & Spurway (1965a & b, 1968) studied some aspectsof breed<strong>in</strong>g biology of <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g, and Santharam(1980, 1995) made a few additional observations—both studieswere from southern India. In the present study observations havebeen made on the hatch<strong>in</strong>g <strong>success</strong> of this species <strong>in</strong> Haridwar(northern India) with an emphasis on the factors responsible foregg-loss or nest-failure.eggs from the high temperature. Searches for nests were donesystematically and all parts of the study area were searchedthoroughly and repeatedly. In addition, local <strong>in</strong>habitants suchas children, farmers, and cattle-grazers were regularly queriedregard<strong>in</strong>g the occurrence of the nest(s) of <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> their premises or nearby areas.MethodsStudy was carried out dur<strong>in</strong>g the peak breed<strong>in</strong>g months (May–June) of <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> 2006 and 2007. Observationswere made from considerable distance (20.88 m ±5.89 m, mean±SD) or hides us<strong>in</strong>g 10x50 prismatic b<strong>in</strong>oculars <strong>in</strong> the scrub andwastelands of Haridwar district (29º55’N 78º08’E), Uttarakhandstate (Fig. 1).Fig. 2. <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>cubat<strong>in</strong>g eggs <strong>in</strong> the study areaV<strong>in</strong>aya Kumar SethiAmit KumarFig. 1. Nest<strong>in</strong>g habitat of the <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Haridwar,Uttarakhand, India.Nests were found by spott<strong>in</strong>g the bird—while it scraped theground for nest<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>cubat<strong>in</strong>g the eggs (Fig. 2), or threaten<strong>in</strong>gpredators at nest-sites. Noon was the best time for spott<strong>in</strong>g thenests as dur<strong>in</strong>g this time nests were never left unattended and atleast one of the birds was found sitt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the nests to protect theThe clutch size of this species ranges from 3 to 4 (Fig. 3) withan <strong>in</strong>cubation period of 27 to 30 days (Jayakar & Spurway 1968; Ali& Ripley 1998). Thus, nests found prior to clutch completion were<strong>in</strong>spected at <strong>in</strong>tervals of 2–5 days, and more frequently dur<strong>in</strong>gthe expected dates of their hatch<strong>in</strong>g. Whereas, nests spotted afterclutch completion were <strong>in</strong>spected <strong>in</strong>variably on alternate daysat any time of the day. The colour of the eggs matches the soil toperfection. To re-spot/re-observe the nest quickly, and reduce thechance of attract<strong>in</strong>g predators (Salek & Smilauer 2002), a brickwith a stone on top was placed as a ‘nest-marker’ with<strong>in</strong> a 1.5m radius of the active nest. To m<strong>in</strong>imize disturbance we did notspend more than ten seconds near the nest dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>spection. Anest was assumed to be depredated when it was found emptyafter hav<strong>in</strong>g previously been known to conta<strong>in</strong> eggs, except whenit was thought that <strong>in</strong>cubation had completed and the nidifugousyoung moved on. It was often possible to dist<strong>in</strong>guish <strong>success</strong>fuland depredated nests because of parental shell removal behaviour.Empty nests conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g yolk sta<strong>in</strong>s and large eggshell fragments,<strong>in</strong>dented eggshells <strong>in</strong> the nest vic<strong>in</strong>ity or, no eggshell fragments,were assumed to have been depredated (Be<strong>in</strong>tema & Muskens1987; Sordahl 1994; Hart et al. 2002).<strong>Indian</strong> <strong>Birds</strong> Vol. 5 No. 5 (Publ. 5 April 2010) 139

Sethi et al: <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>gV<strong>in</strong>aya Kumar SethiFig. 3. A clutch of the <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the study area.We measured only the net change <strong>in</strong> nests, eggs, and chicksand, therefore, could estimate only the m<strong>in</strong>imum numberproduced <strong>in</strong> each nest (Gore & K<strong>in</strong>nison 1991). In some nestswe also observed asynchronous hatch<strong>in</strong>g (Jayakar & Spurway1968), which took 20–43 hrs for completion. In addition, theyoung started mov<strong>in</strong>g out of nests with<strong>in</strong> a couple of hours afterhatch<strong>in</strong>g and concealed themselves <strong>in</strong> the nearby vegetation.Inspection of such nests, from which some young had left, butwhich still conta<strong>in</strong>ed un-hatched eggs, could bias data. Therefore,such nests were observed either at dawn or noon, when the birdwas clearly observed <strong>in</strong>cubat<strong>in</strong>g / brood<strong>in</strong>g. The exist<strong>in</strong>g groundcover was generally sufficient for chicks to conceal themselves,and so, to reduce any bias <strong>in</strong> detect<strong>in</strong>g chicks, we, along withtwo local <strong>in</strong>habitants, observed <strong>in</strong>dividual nests cont<strong>in</strong>uously, forlonger durations (up to four hours) from a bl<strong>in</strong>d or a vehicle—tospot flee<strong>in</strong>g chicks, and search vegetation for those that werehid<strong>in</strong>g.<strong>Hatch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>success</strong> was def<strong>in</strong>ed as the number of eggs thathatched <strong>success</strong>fully, and was calculated as a percentage on thebasis of the total number of eggs laid. Chicks were summarizedper nest as a proportion. Data were tested statistically us<strong>in</strong>g twotailedt-test (Zar 1984).Observations & resultsA total of 87 hrs was spent <strong>in</strong> the field <strong>in</strong> both years. A total of 16nests of <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g were observed <strong>in</strong> 2006 (N=7)and 2007 (N=9). Three- and four-egg clutches were the onlyclutch sizes recorded dur<strong>in</strong>g the present study. There were twonests with three-egg clutches <strong>in</strong> 2006 and four <strong>in</strong> 2007; while fivenests conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g four-egg clutches were observed both, <strong>in</strong> 2006and 2007. Thus, a larger number of nests (62.5%) had four-eggclutches. Breed<strong>in</strong>g parameters such as mean clutch size, meannumber of eggs hatched, and mean number of eggs lost did notdiffer significantly between years (2006 & 2007), and thus thedata of both the years were pooled for the assessment of hatch<strong>in</strong>g<strong>success</strong> (Table 1).A total of 58 eggs were laid <strong>in</strong> 16 nests of the <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong>Lapw<strong>in</strong>g, out of which 16 hatched <strong>success</strong>fully, lead<strong>in</strong>g to ahatch<strong>in</strong>g <strong>success</strong> of 27.58%. Different factors, namely predation,nest damage, and hatch<strong>in</strong>g failure were responsible for egg loss(Table 2).We observed a fair difference <strong>in</strong> the behaviour of the <strong>in</strong>cubat<strong>in</strong>g<strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>gs, towards us, dur<strong>in</strong>g different phasesof their <strong>in</strong>cubation period, which lasted 27–30 days. When weapproached the nest dur<strong>in</strong>g the early days of <strong>in</strong>cubation, the<strong>in</strong>cubat<strong>in</strong>g bird left the nest silently, without perform<strong>in</strong>g anyagonistic displays (n=62 times for 9 lapw<strong>in</strong>gs). However, <strong>in</strong> laterphase (after about 15 days of clutch completion) both adultsproduced alarm calls (n=128 times for 16 lapw<strong>in</strong>gs) (Fig. 4). The<strong>in</strong>tensity and duration of alarm calls, accompanied by the div<strong>in</strong>gdisplay over us, were at a peak two–three days prior to hatch<strong>in</strong>g(n=57 times for 16 lapw<strong>in</strong>gs). Clutton-Brock (1991) has suggestedthat with the advancement <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>cubation period, the value of clutch<strong>in</strong>creases for parents, and adults become more reluctant to desertnests. Similar alterations <strong>in</strong> the behaviour of <strong>in</strong>cubat<strong>in</strong>g birds havealso been reported <strong>in</strong> V. chilensis (Naranjo 1991) and Recurvirostraavosetta (Cuervo 2004).Fig. 4. Parent <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g emitt<strong>in</strong>g alarm calls to deterpredators <strong>in</strong> the study area.Discussion<strong>Hatch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>success</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g nests was foundlow (27.58%) <strong>in</strong> the present study when compared with theearlier reported hatch<strong>in</strong>g <strong>success</strong> (36.84%) for the same species(Jayakar & Spurway 1968) as well as other ground nest<strong>in</strong>g birds,V<strong>in</strong>aya Kumar SethiTable 1. Average clutch size, number of eggs hatched and lost <strong>in</strong> <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g between study years (2006-07).Clutch size [Mean±SD] No. of eggs hatched [Mean±SD] No. of eggs lost [Mean±SD]2006 2007 2006 2007 2006 20073.71±0.48 (n=7) 3.62±0.52 (n=9) 0.85±0.69 (n=7) 0.87±1.26 (n=9) 2.85±0.69 (n=7) 2.75±1.33 (n=9)t = 0.62, df= 13, P>0.05 t= 0.51, df= 13, P>0.05 t= 0.80, df= 13, P>0.05Table 2. Productivity <strong>in</strong> nests of the <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g dur<strong>in</strong>g 2006-07.Loss of eggs (%) due toNests observed Eggs laid Eggs hatched <strong>Hatch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>success</strong> (%) Eggs lostPredation Nest-damage <strong>Hatch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> failure16 58 16 27.58 42 51.73 17.24 3.45140<strong>Indian</strong> <strong>Birds</strong> Vol. 5 No. 5 (Publ. 5 April 2010)

Sethi et al: <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>gV<strong>in</strong>aya Kumar Sethie.g., Charadrius bic<strong>in</strong>ctus (44%, Bomford 1978), C. montanus (61%,Graul 1975), Anarhynchus frontalis (>70%, Hay 1984), Th<strong>in</strong>ornisnovaeseelandiae (>75%, Davis 1994), Pluvialis apricaria (43%, Pearce-Higg<strong>in</strong>s & Yalden 2003), Recurvirostra avosetta (89%, Cuervo 2004),Himantopus himantopus (94%, Cuervo 2004), etc.It is well known that ground-nest<strong>in</strong>g birds are victims of highrates of predation of their eggs and young (Armstrong 1954;Massey & Fancher 1989; Salek & Smilauer 2002), and that predationhas been reported as a major limit<strong>in</strong>g factor to their productivity(Newton 1994; Pearce-Higg<strong>in</strong>s & Yalden 2003; Cuervo 2004). Inthe present study also, low hatch<strong>in</strong>g <strong>success</strong> of <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong>Lapw<strong>in</strong>g was attributed ma<strong>in</strong>ly to the <strong>in</strong>creased predation rate astheir nests were easily accessible to a large number of predators(Table 2). It was difficult to see the actual predation of eggs, andmost of the conclusions <strong>in</strong> this respect were <strong>in</strong>ferential, based oncircumstantial evidence.Similar to Jayakar & Spurway (1965a, 1968), we too observedaerial (corvids and other large birds) as well as terrestrial (dog, pig,snake, mongoose, etc.) predators that caused considerable damageto the eggs of <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g (Fig. 5). It was not alwayspossible to identify the predator. However, direct observations ofpredators attack<strong>in</strong>g nests revealed that ground predators causedthe loss of complete clutches (n=4), while aerial predators causedpartial losses (n=5). This could be due to the reason that nest<strong>in</strong>gpairs were generally unable to distract the large ground predatorsfrom the nests once they had been located. Aerial predators,however, were attacked more vigorously, and persistently, andparents often did not let them predate on the complete clutch.Fig. 5. Predated (partially-eaten) egg of the <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>the study area.Corvids were the major aerial predators of <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong>Lapw<strong>in</strong>g nests <strong>in</strong> the study area, and maximum <strong>in</strong>stances ofaerial encounters occurred between them and the lapw<strong>in</strong>gs.Corvid predation on ground-nest<strong>in</strong>g birds is well documented(Elliot 1985; Parr 1993; Kis et al. 2000; Hart et al. 2002). We foundparent <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>gs bold enough to distract mostof the aerial predators like House Crow Corvus splendens, JungleCrow C. macrorhynchos, Greater Coucal Centropus s<strong>in</strong>ensis, andBlack Kite Milvus migrans from their nests. However, attacks bya group of crows or a s<strong>in</strong>gle Shikra Accipiter badius were difficultto deal with.Other than such predatory pressures, nests of ground-nest<strong>in</strong>gbirds are prone to be<strong>in</strong>g damaged by graz<strong>in</strong>g animals (Be<strong>in</strong>tema& Muskens 1987, Hart et al. 2002) and human be<strong>in</strong>gs (Pfister et al.1992, Gill et al. 2001, Fletcher et al. 2005).In 2006 we observed a herd of graz<strong>in</strong>g goats and sheeptrampl<strong>in</strong>g three eggs <strong>in</strong> a nest. Also, for a number of times parentswere observed aggressively threaten<strong>in</strong>g the graz<strong>in</strong>g animals withloud alarm calls near their nests. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Shrubb (1990)graz<strong>in</strong>g animals may depress the breed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>success</strong> of birds thatsettle on ground by disturb<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>cubat<strong>in</strong>g adults thereby<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the risk of egg loss by either predation or desertion.It has also been argued that the presence of livestock deterslapw<strong>in</strong>gs from settl<strong>in</strong>g on the ground for nest<strong>in</strong>g (Berg et al. 1992;Elliot 1985). Hart et al. (2002) found that the breed<strong>in</strong>g densities ofLapw<strong>in</strong>g V. vanellus negatively correlated with the presence oflivestock, and they suggested the exclusion of livestock from someareas as a desirable option <strong>in</strong> order to <strong>in</strong>crease nest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>success</strong> ofLapw<strong>in</strong>gs.It has been suggested that human threats to ground-nest<strong>in</strong>gbirds, are either direct i.e., damage to nest contents or young,or <strong>in</strong>direct i.e., habitat destruction (Jayakar & Spurway 1968;Santharam 1995; Fletcher et al. 2005). In one <strong>in</strong>stance, a boy whowas play<strong>in</strong>g cricket <strong>in</strong> the study area, un<strong>in</strong>tentionally, damageda nest of <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g (conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g four eggs). We didnot f<strong>in</strong>d the problem of habitat destruction affect<strong>in</strong>g the nest<strong>in</strong>gbiology of <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> our study area.We observed two <strong>in</strong>stances of hatch<strong>in</strong>g failure <strong>in</strong> <strong>Yellow</strong><strong>wattled</strong>Lapw<strong>in</strong>g. Un-hatched eggs rema<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the nest evenafter the parents had moved from the area. <strong>Hatch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> failure dueto <strong>in</strong>fertility or embryo mortality is a potentially important causeof reduced breed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>success</strong> <strong>in</strong> birds, and as <strong>in</strong> the present case,has also been reported <strong>in</strong> other ground nest<strong>in</strong>g birds (Byrkjedal1987; Davis 1994).AcknowledgementsWe are grateful to the Head, Department of Zoology and EnvironmentalScience, Gurukula Kangri University, Haridwar, Uttarakhand, Indiafor provid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>frastructural facilities to carry out this work. We thankShivchand Arora for his valuable assistance dur<strong>in</strong>g field visits.ReferencesAli, S. & Ripley, S. D. 1998. Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan.Megapodes to Crab Plover. 2 nd ed. Vol. 2. Delhi: (Sponsored by BombayNatural History Society). Oxford University Press (Oxford IndiaPaperbacks).Armstrong, E. A. 1954. The ecology of distraction display. Anim. Behav. 2:121-135.Be<strong>in</strong>tema, A. J. & Muskens, G. J. D. M. 1987. Nest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>success</strong> of birds <strong>in</strong>Dutch agricultural grasslands. J. Appl. Ecol. 24: 743-758.Berg. A., L<strong>in</strong>dberg, T. & Kallebr<strong>in</strong>k, K. G. 1992. <strong>Hatch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>success</strong> of Lapw<strong>in</strong>gson farmland: differences between habitats and colonies of differentsizes. J. Anim. Ecol. 61: 469-476.Bomford, M. 1978. The behaviour of the banded dotterel Charadrius bic<strong>in</strong>ctus.M.Sc. thesis, Department of Zoology, University of Otago, Duned<strong>in</strong>.Byrkjedal, I. 1987. Antipredator behaviour and breed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>success</strong> <strong>in</strong> GreaterPlover and Eurasian Dotterel. Condor 89: 40-47.Clutton-Brock, T. H. 1991. The evolution of parental care. New Jersey: Pr<strong>in</strong>cetonUniversity Press.Cuervo, J. J. 2004. Nest-site selection and characteristics <strong>in</strong> a mixed-speciescolony of Avocets Recurvirostra avosetta and Black-w<strong>in</strong>ged StiltsHimantopus himantopus. Bird Study 51: 20-24.Davis, A. 1994. Breed<strong>in</strong>g biology of the New Zealand Shore Plover Th<strong>in</strong>ornisnovaeseelandiae. Notornis 41: 195-208.Elliot, R. D. 1985. The exclusion of avian predators from aggregations ofnest<strong>in</strong>g Lapw<strong>in</strong>gs (<strong>Vanellus</strong> vanellus). Anim. Behav. 33: 308-314.Fletcher, K., Warren, P. & Ba<strong>in</strong>es, D. 2005. Impact of nest visits by humanobservers on hatch<strong>in</strong>g <strong>success</strong> <strong>in</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>Vanellus</strong> vanellus: a fieldexperiment. Bird Study 52: 221-223.Gill, J. A., Norris, K. & Sutherland, W. J. 2001. The effects of disturbanceon habitat use by Black-tailed Godwits Limosa limosa. J. Appl. Ecol.38: 846-856.Gore, J. A., & K<strong>in</strong>nison, M. J. 1991. <strong>Hatch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>success</strong> <strong>in</strong> roof and groundcolonies of Least Terns. The Condor 93: 759–762.Graul, W. D. 1975. Breed<strong>in</strong>g biology of mounta<strong>in</strong> plover. Wilson Bull. 85:7-31.Grimmett, R., Inskipp, C. & Inskipp, T. 1998. <strong>Birds</strong> of the <strong>Indian</strong> Subcont<strong>in</strong>ent.New Delhi: Oxford University Press.<strong>Indian</strong> <strong>Birds</strong> Vol. 5 No. 5 (Publ. 5 April 2010) 141

Sethi et al: <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>gHart, J. D., Milsom, T. P., Baxter, A., Kelly, P. F. & Park<strong>in</strong>, W. K. 2002. Theimpact of livestock on Lapw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Vanellus</strong> vanellus breed<strong>in</strong>g densitiesand performance on coastal graz<strong>in</strong>g marsh. Bird Study 49: 67-78.Hay, J. R. 1984. The behavioural ecology of the wrybill plover Anarhynchusfrontalis. Ph.D. thesis, Department of Zoology, University of Auckland,New Zealand.Jayakar, S. D. & Spurway, H. 1965a. The <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>Vanellus</strong>malabaricus (Boddaert), a tropical dry-season nester. II. Additional dataon breed<strong>in</strong>g biology. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 62: 1–14.Jayakar, S. D. & Spurway, H. 1965b. The <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g, a tropicaldry-season nester [<strong>Vanellus</strong> malabaricus (Boddaert), Charadriidae]. I.Thelocality, and the <strong>in</strong>cubatory adaptations. Zool. Jahrbuecher 92: 53–72.Jayakar, S. D. & Spurway, H. 1968. The <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong> Lapw<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>Vanellus</strong>malabaricus (Boddaert), a tropical dry-season nester. III. Two furtherseasons’ breed<strong>in</strong>g. J. Bombay Nat. Hist.Soc. 65: 369–383.Kis, J., Liker, A. & Szekely, T. 2000. Nest defence by Lapw<strong>in</strong>gs: observationson natural behaviour and experiment. Ardea 88 :155-163.Massey, B. W. & Fancher, J. M. 1989. Renest<strong>in</strong>g by California Least Terns. J.Field Ornithol. 60: 350-357.Naranjo, L. G. 1991. Notes on reproduction of the Southern Lapw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>Colombia. Ornitol. Neotrop. 2: 95-96.Newton, I. 1994. Experiments on the limitation of bird breed<strong>in</strong>g densities:a review. Ibis 136: 397-411.Parr, R. 1993. Nest predation and numbers of golden plovers Pluvialisapricaria and other moorland waders. Bird Study 40: 223-231.Pearce-Higg<strong>in</strong>s, J. W. & Yalden, D. W. 2003. Golden Plover Pluvialis apricariabreed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>success</strong> on a moor managed for shoot<strong>in</strong>g Red Grouse Lagopuslagopus. Bird Study 50: 170-177.Pfister, C., Harr<strong>in</strong>gton, B. A. & Lav<strong>in</strong>e, M. 1992. The impact of humandisturbance on shorebirds at a migration stag<strong>in</strong>g area. Biol. Conser.60: 115-126.Salek, M. & Smilauer, P. 2002. Predation on Northern Lapw<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Vanellus</strong>vanellus nests: the effect of population density and spatial distributionof nests. Ardea 90: 51-60.Santharam, V. 1980. Some observations on the nests of <strong>Yellow</strong>-<strong>wattled</strong>Lapw<strong>in</strong>g, Stone Curlew, Blackbellied F<strong>in</strong>ch-Lark and Redw<strong>in</strong>gedBush-Lark. Newsletter for Birdwatchers 20 (6-7): 5–12.Santharam, V. 1995. Some observations on the ground nest<strong>in</strong>g birds at theAdyar Estuary, Madras. Newsletter for Birdwatchers 35 (2): 24–25.Shrubb, M. 1990. Effects of agricultural change on nest<strong>in</strong>g Lapw<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>Vanellus</strong>vanellus <strong>in</strong> England and Wales. Bird Study 37: 115-127.Sordahl, T. A. 1994. Eggshell removal behaviour of American Avocets andBlack-necked Stilts. J. Field Ornithol. 65: 461-465.Zar, J. H. 1984. Biostatistical Analysis. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.Brown-breasted Flycatcher Muscicapa muttui:a new record for GujaratJ. K. Tiwari & Maulik VaruTiwari, J. K., & Varu, M., 2010. Brown-breasted Flycatcher Muscicapa muttui: a new record for Gujarat. <strong>Indian</strong> <strong>Birds</strong> 5 (5): 142.J. K. Tiwari, Centre for Desert and Ocean, Village Moti Virani, Nakhtrana taluk, Kachchh 370665, Gujarat, India. Email: ecdo<strong>in</strong>dia@yahoo.comMaulik Varu, C/o, S. N. Varu, Juna Vas, Temple street, Madhapur, Kutch, Gujarat, India.Manuscript received on 6 July 2009.On the <strong>Indian</strong> Subcont<strong>in</strong>ent the Brown-breasted FlycatcherMuscicapa muttui breeds <strong>in</strong> north-eastern India, andw<strong>in</strong>ters <strong>in</strong> south-western India, and Sri Lanka (Grimmettet al. 1998).On 24 October 2007 Hans and Magda Sigg (Swiss birders), andthe first author spotted a Brown-breasted Flycatcher <strong>in</strong> the grovesof P<strong>in</strong>gleshwar temple (23°5’N 68°48’E), located on the southerncoast of Kachchh, Gujarat (India).The flycatcher had a white throat, brown breast-band, fleshcolouredlegs, and yellow lower mandible, as described <strong>in</strong>Kazmierczak (2000). Photographs of the bird were sent to BillHarvey, Uffe Sørensen, and Krys Kazmierczak, who confirmed theidentification (pers. comm., November 2007). There appears to beno record of this species from Gujarat (Rasmussen 2005).Maulik Varu later reported (24 October 2008) this speciesfrom Chaduva reserved forest <strong>in</strong> Kachchh, Gujarat, which is c.60km from P<strong>in</strong>gleshwar; participants of Bombay Natural HistorySociety’s nature camp at Chaduva also spotted one on 19 December2009. These records from Kachchh, besides be<strong>in</strong>g an addition tothe avifauna of Gujarat state, greatly extend westward the knowndistribution of the Brown-breasted Flycatcher. In the absence ofmore and regular sight<strong>in</strong>gs, it would be prudent to suggest thatthe above sight<strong>in</strong>gs are of vagrant birds. However, birdwatchersneed to be alert to the possibility of these birds occurr<strong>in</strong>g towardsthe west of their known migratory route <strong>in</strong> pen<strong>in</strong>sular India.AcknowledgementsJ. K. Tiwari is thankful to Uffe Sørensan, Bill Harvey, and Krys Kazmierczakfor their k<strong>in</strong>d help with identification. Thanks are also due to Hans andMagda Sigg.J. K. TiwariBrown-breasted Flycatcher Muscicapa muttui, P<strong>in</strong>gleshwar, Gujarat.ReferencesGrimmett, R., Inskipp, C., & Inskipp, T., 1998. <strong>Birds</strong> of the <strong>Indian</strong> Subcont<strong>in</strong>ent.1st ed. London; Christopher Helm, A & C Black.Kazmierczak, K., 2000, A field guide to the birds of India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan,Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and the Maldives. New Delhi: Om BookService.Rasmussen, P. C., & Anderton, J. C., 2005, <strong>Birds</strong> of South Asia: the RipleyGuide. 2 vols. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton D.C. & Barcelona: Smithsonian Institution& Lynx Edicions.142<strong>Indian</strong> <strong>Birds</strong> Vol. 5 No. 5 (Publ. 5 April 2010)