Cambridge University Botanical Garden - Forestry Journal

Cambridge University Botanical Garden - Forestry Journal

Cambridge University Botanical Garden - Forestry Journal

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

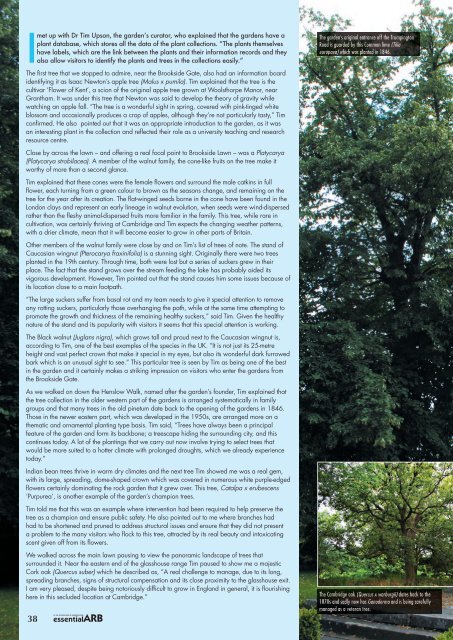

Imet up with Dr Tim Upson, the garden’s curator, who explained that the gardens have aplant database, which stores all the data of the plant collections. “The plants themselveshave labels, which are the link between the plants and their information records and theyalso allow visitors to identify the plants and trees in the collections easily.”The first tree that we stopped to admire, near the Brookside Gate, also had an information boardidentifying it as Isaac Newton’s apple tree (Malus x pumila). Tim explained that the tree is thecultivar ‘Flower of Kent’, a scion of the original apple tree grown at Woolsthorpe Manor, nearGrantham. It was under this tree that Newton was said to develop the theory of gravity whilewatching an apple fall. “The tree is a wonderful sight in spring, covered with pink-tinged whiteblossom and occasionally produces a crop of apples, although they’re not particularly tasty,” Timconfirmed. He also pointed out that it was an appropriate introduction to the garden, as it wasan interesting plant in the collection and reflected their role as a university teaching and researchresource centre.Close by across the lawn – and offering a real focal point to Brookside Lawn – was a Platycarya(Platycarya strobilacea). A member of the walnut family, the cone-like fruits on the tree make itworthy of more than a second glance.Tim explained that these cones were the female flowers and surround the male catkins in fullflower, each turning from a green colour to brown as the seasons change, and remaining on thetree for the year after its creation. The flat-winged seeds borne in the cone have been found in theLondon clays and represent an early lineage in walnut evolution, when seeds were wind-dispersedrather than the fleshy animal-dispersed fruits more familiar in the family. This tree, while rare incultivation, was certainly thriving at <strong>Cambridge</strong> and Tim expects the changing weather patterns,with a drier climate, mean that it will become easier to grow in other parts of Britain.Other members of the walnut family were close by and on Tim’s list of trees of note. The stand ofCaucasian wingnut (Pterocarya fraxinifolia) is a stunning sight. Originally there were two treesplanted in the 19th century. Through time, both were lost but a series of suckers grew in theirplace. The fact that the stand grows over the stream feeding the lake has probably aided itsvigorous development. However, Tim pointed out that the stand causes him some issues because ofits location close to a main footpath.“The large suckers suffer from basal rot and my team needs to give it special attention to removeany rotting suckers, particularly those overhanging the path, while at the same time attempting topromote the growth and thickness of the remaining healthy suckers,” said Tim. Given the healthynature of the stand and its popularity with visitors it seems that this special attention is working.The Black walnut (Juglans nigra), which grows tall and proud next to the Caucasian wingnut is,according to Tim, one of the best examples of the species in the UK. “It is not just its 25-metreheight and vast perfect crown that make it special in my eyes, but also its wonderful dark furrowedbark which is an unusual sight to see.” This particular tree is seen by Tim as being one of the bestin the garden and it certainly makes a striking impression on visitors who enter the gardens fromthe Brookside Gate.As we walked on down the Henslow Walk, named after the garden’s founder, Tim explained thatthe tree collection in the older western part of the gardens is arranged systematically in familygroups and that many trees in the old pinetum date back to the opening of the gardens in 1846.Those in the newer eastern part, which was developed in the 1950s, are arranged more on athematic and ornamental planting type basis. Tim said, “Trees have always been a principalfeature of the garden and form its backbone; a treescape hiding the surrounding city, and thiscontinues today. A lot of the plantings that we carry out now involve trying to select trees thatwould be more suited to a hotter climate with prolonged droughts, which we already experiencetoday.”Indian bean trees thrive in warm dry climates and the next tree Tim showed me was a real gem,with its large, spreading, dome-shaped crown which was covered in numerous white purple-edgedflowers certainly dominating the rock garden that it grew over. This tree, Catalpa x erubescens‘Purpurea’, is another example of the garden’s champion trees.Tim told me that this was an example where intervention had been required to help preserve thetree as a champion and ensure public safety. He also pointed out to me where branches hadhad to be shortened and pruned to address structural issues and ensure that they did not presenta problem to the many visitors who flock to this tree, attracted by its real beauty and intoxicatingscent given off from its flowers.We walked across the main lawn pausing to view the panoramic landscape of trees thatsurrounded it. Near the eastern end of the glasshouse range Tim paused to show me a majesticCork oak (Quercus suber) which he described as, “A real challenge to manage, due to its long,spreading branches, signs of structural compensation and its close proximity to the glasshouse exit.I am very pleased, despite being notoriously difficult to grow in England in general, it is flourishinghere in this secluded location at <strong>Cambridge</strong>.”38The garden’s original entrance off the TrumpingtonRoad is guarded by this Common lime (Tiliaeuropaea) which was planted in 1846.The <strong>Cambridge</strong> oak (Quercus x warburgii) dates back to the1870s and sadly now has Ganoderma and is being carefullymanaged as a veteran tree.

First Class TreesCAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY BOTANIC GARDEN was first opened in 1846; a result of thepassion and vision of Professor John Henslow who, as well as developing gardenswith plant species from around the world, saw trees as being a major part of thewhole project. Today, the gardens which are located less than a mile from <strong>Cambridge</strong>town centre, have over 8,000 plant species, including nine National PlantCollections, and a stunning arboretum which has around 1,500trees covering 1,200 species and varieties.With such an abundance of trees, many of which arechampions or have heritage credentials, James Hendriewent along to find out more.The branches of this Indian Bean (Catalpa x erubescens‘Purpurea’) have had to be shortened to address structural issuesand for public safety reasons.From two Caucasian wingnut (Pterocaryafraxinifolia) trees, both of which have long sincebeen lost, this amazing series of suckers have grownup making this tree one of the most outstanding inthe garden.39

A short distance away grows a champion Gerard’s pine (Pinus gerardiana) with its distinctive scaly bark.It is over 14 metres tall, easily making it the tallest in Britain and Tim confirmed the desire of the gardens tomaintain this tree species at <strong>Cambridge</strong>, with new plants being propagated from it by seed and grafting. Ourtour not only saw us review individual trees but also, in the case of some beech trees, a ‘family’ of them.On the edge of the Cory Lawn Tim paused to show me an interesting example of Henslow’s original plantingsof the 1840s – four different beech trees all growing side by side. “Henslow wanted to illustrate the variationwithin species and show how ‘monstrosities’, as he called them, were produced by random and abruptchanges in the genetic code of the Common beech.”A Common beech (Fagus sylvatica) is surrounded by a Cut-leaved beech (Fagus sylvatica ‘Laciniata’),another type has upward turning tips in its branches – not a specific taxa, just showing variation, and thereis an amazing example of a beech with a more pendulous habit and distinct graft line at about 1.5m (Fagussylvatica ‘Pendula’ – just a more pendulous variant and not this cultivar).Henslow’s thoughts on variation, as demonstrated through these plantings, are important as he was mentorto Charles Darwin and signed the letter recommending him for the Beagle voyage. Darwin’s own theory ofevolution may have its origins with Henslow at <strong>Cambridge</strong>.The garden’s Giant redwood trees (Sequoiadendrongiganteum) are believed to have come as seedlings fromthe famous William Lobb nursery in the 1850s.This Cork oak (Quercus suber) is a challenge tomanage because of its large spreading branches and itsproximity to the glasshouses. Sadly, it is also showingsigns of structural compensation.Tim Upson next to the Wild pear that has become thefocal point of a storybook called ‘The Magic Brick Tree’.No trip to the <strong>Cambridge</strong> Botanic <strong>Garden</strong>s could be completed without taking time to check out the garden’svery own <strong>Cambridge</strong> oak (Quercus x warburgii). Interestingly, this tree is not a champion, despite its near17-metre height and crown of nearly 20 metres! It is, nevertheless, a wonderful example. While its original andexact planting date may be unknown, it is certainly a tree that provides year-round interest to visitors, with itscopper-red spring foliage and golden yellow catkins.It is a tree Tim and his crew are now managing as a veteran. It has Ganoderma and plenty of dead wood inthe canopy, so they have redirected the path away from the canopy. They manage it for its biodiversity valueand new plantings will mark the garden’s two entrances in the future.From a similar period, in terms of plantings, comes the garden’s collection of Giant redwood (Sequoiadendrongiganteum). Two of the trees are located on opposite sides of the main walk near the fountain. It is thought thatthese specimens may have been planted out in 1855, having been grown from original Veitch’s Nursery seeds.It was further up the path though that Tim took me to see a 31-metre high example of the redwood, the tallesttree in the gardens.As we approached the end of our tour Tim had certainly saved some of the best trees to the last for me to see.The Dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides), which grows gracefully on the south-western edge of thelake, is the first of its kind to have been grown in Britain. The species was discovered in China in 1946, havingonly previously been known to man through 100-million-year-old fossilised remains. Seed reached <strong>Cambridge</strong>via the British Consulate and Professor of Botany before any garden in the UK and it was the first to be planted.It was recognised in 2002 as being one of the fifty Great British trees commemorating the Queen’s GoldenJubilee.“This type of tree is one that favours damp conditions and the planting of it near to the lake has certainlyhelped its development. It is fast growing and while it is now a common sight throughout Britain and some haveovertaken ours in height, others do not have the rugged, fluted trunk that ours does and can’t claim to be thefirst grown,” Tim told me.The garden’s original entrance gate on the Trumpington Road is where the then Vice Chancellor of theuniversity, the Reverend Ralph Tatham, planted a simple Common lime (Tilia europaea) in 1846, still growingproudly in this location today. While the main visitor entrance has moved, the lime has remained in situ andforms a real focal point to the main walk of the gardens.Located on the south-western edge of the systematic beds, the Osage orange (Maclura pomifera) is one of themost unusual examples of the Mulberry family. Tim told me that the tree took its name from the Missouri Indianswho used it to make bows and clubs. Funnier still though was the fact that its fruit, which resembles a green,knobbly orange, is known by the staff of the gardens as ‘pickled gardener’s brains’.If this was an unusual tree, our final port of call was a very ordinary looking Wild pear (Pyrus communis),whose only point of interest as far as I could see were the tar-filled bricks inside its hollow trunk, a relic of thedays in the 1960s when this method of treatment was thought to help such ailing trees.Tim enlightened me as to the reason this tree was special. A group of young carers from <strong>Cambridge</strong> used it asthe focal point of a storybook they wrote entitled The Magic Brick Tree.The young people wrote about a strange world inside the bricked-up tree and recounted tales of mystery andintrigue in the magical kingdom that the tree was located in. “It was a wonderful experience to be involved inthis project and see just how creative these young carers could be as they gave a very different perspective tothis tree,” Tim told me, as he posed next to this magical tree for a picture.While there are countless many other trees of interest at the gardens it was clear to me that the ones Timselected for my visit were of great interest. Maybe not all were champions, but they all had a story to tell. Acouple of months after my visit Tim contacted me to let me know of another tree causing interest at <strong>Cambridge</strong>.The garden’s Emmenopterys henryi had flowered for the first time in thirty years – and only the fifth time in theUK!40