What is Four in Balance? - PDST

What is Four in Balance? - PDST

What is Four in Balance? - PDST

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

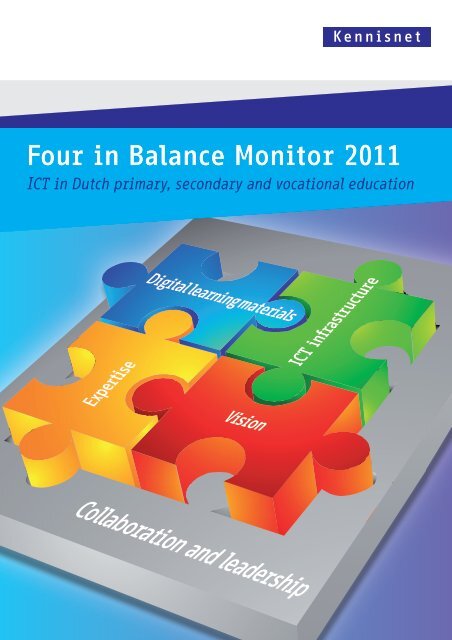

<strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> Monitor 2011ICT <strong>in</strong> Dutch primary, secondary and vocational educationExpert<strong>is</strong>eDigital learn<strong>in</strong>g materialsV<strong>is</strong>ionICT <strong>in</strong>frastructureCollaboration and leadership

<strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> Monitor 2011ICT <strong>in</strong> Dutch primary, secondary and vocational education

ContentsMa<strong>in</strong> topics 61 <strong>What</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong>? 91.1 The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> model 91.2 <strong>What</strong> do we mean by “balance”? 101.3 The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> Monitor 132 Benefits of us<strong>in</strong>g ICT 152.1 Kenn<strong>is</strong>net’s research program 152.2 Classify<strong>in</strong>g ICT applications by pedagogical v<strong>is</strong>ion 172.3 ICT and <strong>in</strong>struction 192.4 Structured practice 212.5 Inquiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>g 252.6 Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn 292.7 Summary 313 ICT <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g 333.1 Teachers at school 333.2 Teachers at home 383.3 Pupils at home 393.4 Summary 434 V<strong>is</strong>ion 444.1 Views on learn<strong>in</strong>g 444.2 Compar<strong>in</strong>g school managers and teachers 464.3 Innovation 474.4 Summary 484

5 Expert<strong>is</strong>e 495.1 Familiarity 495.2 Pedagogical ICT skills 505.3 Summary 526 Digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials 536.1 Computer programs 536.2 Percentage of digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials 556.3 Source 566.4 Summary 577 ICT <strong>in</strong>frastructure 587.1 Computers 597.2 Interactive whiteboards 627.3 Connectivity 647.4 Summary 658 Collaboration and leadership 668.1 Collaboration 668.2 Leadership 688.3 The future 728.4 Summary 739 From ICT use to more effective teach<strong>in</strong>g 749.1 Adapt support to aims 749.2 Use leadership to <strong>in</strong>volve followers 769.3 Formalize professional use 769.4 L<strong>in</strong>k teacher, pupil, and subject matter<strong>in</strong> a digital learn<strong>in</strong>g environment 779.5 Know what works 7810 Bibliography 805

Ma<strong>in</strong> topicsThe <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> Monitor <strong>is</strong> publ<strong>is</strong>hed annually by Kenn<strong>is</strong>net andconcerns the use and benefits of ICT <strong>in</strong> Dutch education. The Monitor<strong>is</strong> based on <strong>in</strong>dependent research and looks at primary, secondaryand vocational education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Below, we summarize thema<strong>in</strong> topics covered <strong>in</strong> the 2011 Monitor.Benefits• ICT can make teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g more efficient, more effective, andmore <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g.• ICT use has become commonplace <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> recent years.Nevertheless, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g ICT use does not necessarily lead to betterresults. The more powerful ICT becomes and the more options it offersfor improv<strong>in</strong>g the quality of education, the more crucial the teacher’srole becomes.• The benefits of ICT depend largely on the presence of a teacher who <strong>is</strong>able to l<strong>in</strong>k the subject matter, the ICT application, and the pupil.Use by teachers• Three quarters of teachers use computers dur<strong>in</strong>g lessons. Th<strong>is</strong> numberhas <strong>in</strong>creased by 2 to 3% <strong>in</strong> recent years.• Teachers spend an average of 8 hours a week us<strong>in</strong>g computers <strong>in</strong> theirlessons, and that figure <strong>is</strong> expected to <strong>in</strong>crease with<strong>in</strong> three years byapproximately 40%, to 11 hours a week. In addition, they spend another7 hours a week on average do<strong>in</strong>g school-related work on their homecomputer.• The ICT applications used most often <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g are the Internet,practice programs, word process<strong>in</strong>g software and electronic learn<strong>in</strong>genvironments. Games and Web 2.0 are used the least.6Use by pupils• Teachers believe that the number of hours that pupils can spendwork<strong>in</strong>g at a computer at school <strong>is</strong> limited to between 1.5 and 3 hoursa day. Teachers believe that pupils can spend a further 7 to 12 hours aweek on computer-based learn<strong>in</strong>g activities outside of school.• It <strong>is</strong> wrongly assumed that youngsters are so skilful with computers

ma<strong>in</strong> topicsthat schools do not need to teach them how to search for and select<strong>in</strong>formation on the Internet. Many pupils have a difficult time us<strong>in</strong>g ICTresponsibly, critically, and creatively as a learn<strong>in</strong>g tool.• The majority of pupils <strong>in</strong> vocational education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g take theirown laptops with them to school. Th<strong>is</strong> happens much less <strong>in</strong> secondaryeducation, and scarcely at all <strong>in</strong> primary school.V<strong>is</strong>ion• Knowledge transfer <strong>is</strong> the most common teach<strong>in</strong>g method today, and willrema<strong>in</strong> so <strong>in</strong> the future. Teachers and school managers expect that ICTwill be used most frequently for purposes of knowledge transfer.• Knowledge construction will become more common <strong>in</strong> education <strong>in</strong> thefuture. Teachers and school managers believe that ICT will support th<strong>is</strong>trend.• Teachers assume that they will cont<strong>in</strong>ue teach<strong>in</strong>g largely without thesupport of ICT. School managers th<strong>in</strong>k otherw<strong>is</strong>e, however; they expectthat with<strong>in</strong> three years’ time, teachers will be us<strong>in</strong>g ICT <strong>in</strong> most of theirlessons.Expert<strong>is</strong>e• Two thirds of teachers feel that they are sufficiently or more thansufficiently familiar with the various options that ICT can offer them <strong>in</strong>their teach<strong>in</strong>g.• School managers say that eight out of ten teachers have sat<strong>is</strong>factorytechnical ICT skills; for example, they can use a word process<strong>in</strong>gprogram and the Internet.• School managers estimate that almost six out of ten teachers havemastered the pedagogical skills they need to use ICT <strong>in</strong> their teach<strong>in</strong>g.Digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials• Teachers ma<strong>in</strong>ly use standard office applications such as wordprocess<strong>in</strong>g programs and e-mail. Slightly more than half of teachers alsoused software associated with a course/coursebook or a subject-specificprogram.• A fourth of all learn<strong>in</strong>g material <strong>is</strong> digital. Teachers expect that th<strong>is</strong>share will <strong>in</strong>crease considerably <strong>in</strong> the years ahead.• Approximately a third of teachers occasionally develop their own digital7

learn<strong>in</strong>g materials. That <strong>is</strong> 10% more than two years ago. In two years’time, more than half of teachers expect to be develop<strong>in</strong>g their owndigital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials.Infrastructure• The ratio of computers to pupils at school <strong>is</strong> the same as last year: onecomputer for every five pupils.• The adoption of <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboards has gone much faster thanschool managers had anticipated <strong>in</strong> previous surveys. Almost everyschool now has one or more <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboards. Expectations arethat nearly every primary school classroom will be equipped with an<strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard before long.• Wireless Internet and optical fiber connections are becom<strong>in</strong>g standardat secondary schools and <strong>in</strong> the vocational education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gsector.Collaboration and leadership• Two thirds of teachers say that ICT use <strong>is</strong> a matter of personalpreference, and that there are no shared (school-wide) goals.• Approximately eight out of ten schools have an ICT policy plan. Abouthalf of these schools are actually implement<strong>in</strong>g th<strong>is</strong> plan.• At the moment, school managers are focus<strong>in</strong>g on purchas<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>frastructure facilities and digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials (materialfactors). In order to ensure that more teachers make better use of ICT,school managers would like to place put greater emphas<strong>is</strong> on teachers’professional development and on develop<strong>in</strong>g a pedagogical v<strong>is</strong>ionconcern<strong>in</strong>g the use of ICT (human factors).8From use to better performance• There are solid foundations for us<strong>in</strong>g ICT <strong>in</strong> every sector of education.Schools can get more out of ICT by:1. adapt<strong>in</strong>g support to aims;2. us<strong>in</strong>g leadership to get followers <strong>in</strong>volved;3. formaliz<strong>in</strong>g professional use;4. l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g teacher, pupil and subject matter <strong>in</strong> a digital learn<strong>in</strong>genvironment;5. know<strong>in</strong>g what works.

for leadership to guide the process and to create the right conditions forcollaboration with other professionals (see Figure 1.1).CollaborationLeadershipV<strong>is</strong>ionExpert<strong>is</strong>eDigital learn<strong>in</strong>gmaterialsICT<strong>in</strong>frastructurePedagogical use of ICT for teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>gImprovement <strong>in</strong> quality of educationFigure 1.1: The basic elements of the <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> model (Ten Brummelhu<strong>is</strong>, 2011)1.2 <strong>What</strong> do we mean by “balance”?In th<strong>is</strong> <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> Monitor we look at each of the basic elements of the<strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> model separately, so that we understand the priorities thatschools set for themselves and the basic conditions <strong>in</strong> which they <strong>in</strong>vest. Thatgives us an idea of how th<strong>in</strong>gs stand across the country. The questions weask <strong>in</strong>clude: <strong>What</strong> <strong>in</strong>frastructure facilities do schools purchase? Do they haveenough digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials at their d<strong>is</strong>posal, or are there bottlenecks?How much effort do schools put <strong>in</strong>to develop<strong>in</strong>g a pedagogical v<strong>is</strong>ionregard<strong>in</strong>g the use of ICT <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g?The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> model <strong>is</strong> not only a useful conceptual framework for anational benchmark, it <strong>is</strong> also an implementation model for the susta<strong>in</strong>ableuse of ICT <strong>in</strong> education. <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> <strong>is</strong> not <strong>in</strong>tended to compel schools touse ICT. It <strong>is</strong> <strong>in</strong>tended to help the schools that w<strong>is</strong>h to use ICT make choicesthat will improve the quality of teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g and achieve the relatedbenefits.10

1 - what <strong>is</strong> four <strong>in</strong> balance?In many cases, schools fail to achieve the benefits that they thought theywould atta<strong>in</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g ICT. For example, a project falters because the teachersare not equipped to use the technology, or because the <strong>in</strong>frastructure thatthe school has chosen does not match the pedagogical approach that teachersfavor. The project then never goes beyond a one-time experiment (Van derNeut, 2010; Van Eck, 2009; 2010). One well-known example was described byZucker <strong>in</strong> an article <strong>in</strong> Science. Zucker looked at the <strong>in</strong>vestment schools <strong>in</strong>the United States had made <strong>in</strong> laptops (Zucker, 2009). Although the schoolshad spent a lot of money on the laptops and related equipment, teachersscarcely changed their lessons and failed to use many of the new options attheir d<strong>is</strong>posal. There was no impact on the way pupils thought or learned.Similar f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs have emerged <strong>in</strong> studies explor<strong>in</strong>g the impact of <strong>in</strong>teractivewhiteboards (DiGregorio, 2010; Bann<strong>is</strong>ter, 2010).The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> model allows schools to avoid such pitfalls by help<strong>in</strong>gthem consider, <strong>in</strong> advance, how to organize teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g and what to<strong>in</strong>vest <strong>in</strong>. Thanks to research, we are com<strong>in</strong>g to learn more and more abouthow best to coord<strong>in</strong>ate the four basic elements. One important f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g<strong>is</strong> that the human factors (v<strong>is</strong>ion and expert<strong>is</strong>e) must be considered first,and only then the material ones (learn<strong>in</strong>g materials and <strong>in</strong>frastructure). Inprevious publications, we referred to th<strong>is</strong> particular coord<strong>in</strong>ation sequenceas “education-driven <strong>in</strong>novation” (Law, 2008; De Koster, 2009). The oppositesequence, which starts with technology or digital learn<strong>in</strong>g materials, <strong>is</strong> knownas “technology-driven” or “material-driven” <strong>in</strong>novation (see Figure 1.2).Education-drivenV<strong>is</strong>ionExpert<strong>is</strong>eDigitallearn<strong>in</strong>gmaterialsICT <strong>in</strong>frastructureTechnology-drivenFigure 1.2: Two coord<strong>in</strong>ation sequences: education-driven (start<strong>in</strong>g from the human factors)and technology-driven (start<strong>in</strong>g from the material factors). Education-driven coord<strong>in</strong>ation hasa better chance of succeed<strong>in</strong>g11

Coord<strong>in</strong>ation that puts technology before pedagogy has only a limited chanceof success (Fullan, 2011; Kozma, 2003; Ten Brummelhu<strong>is</strong>, 2008).Crucial human factors <strong>in</strong>clude the follow<strong>in</strong>g:• The ICT facilities match the teacher’s views on educationIf so, then the teacher will certa<strong>in</strong>ly not be unwill<strong>in</strong>g to use ICT <strong>in</strong> h<strong>is</strong>or her lessons (OECD, 2010b; Van Gennip, 2008; Versluijs, 2011). If anICT application conflicts with the teacher’s pedagogical pr<strong>in</strong>ciples,however, he or she will prefer not to use ICT. Teachers will not easilygive up their pr<strong>in</strong>ciples, because they derive much of their professionalidentity from them (Ertmer, 2005; 2009). We look more closely at th<strong>is</strong> <strong>in</strong>Section 4.3.• The teacher <strong>is</strong> familiar with ICT and <strong>is</strong> capable of us<strong>in</strong>g itIf not, then h<strong>is</strong> or her use will be <strong>in</strong>effective. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>in</strong> fact a key factor(Knezek, 2008; Van Buuren, 2010). Once the teacher <strong>is</strong> familiar with thetechnology, he or she must <strong>in</strong>tegrate it <strong>in</strong>to the subject matter and h<strong>is</strong>or her pedagogical approach. Th<strong>is</strong> type of knowledge <strong>is</strong> referred to asTPACK, that <strong>is</strong>: Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (Voogt,2010a).• The teacher <strong>is</strong> conv<strong>in</strong>ced of the added value of ICTIf not, then he or she will tend to stick to a familiar rout<strong>in</strong>e (Tondeur,2008; Voogt, 2010a). It <strong>is</strong> important for teachers’ professionaldevelopment to understand which ICT-related pedagogical strategieswill lead to better pupil performance (Erstad, 2009; Hattie, 2009;Timperly, 2007).• There <strong>is</strong> leadershipA demonstration of leadership can get teachers <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>novation,motivate them, and allow them to develop a shared v<strong>is</strong>ion (Dexter, 2008;Vanderl<strong>in</strong>de, 2011; Waslander, 2011) – not only the trendsetters, butalso (and more specifically) the more hesitant majority (Fullan, 2011;Schut, 2010). We will look more closely at the <strong>is</strong>sue of “leadership” <strong>in</strong>Chapter 8.12

1 - what <strong>is</strong> four <strong>in</strong> balance?1.3 The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> MonitorBenchmarkThe <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> Monitor provides figures on how Dutch schools<strong>in</strong>tegrate ICT <strong>in</strong>to teach<strong>in</strong>g and the results they achieve by do<strong>in</strong>g so. Thedata reveal trends and offer schools a benchmark for compar<strong>in</strong>g theirown situation with those of other educational <strong>in</strong>stitutions (Chapters 3 to8). The Monitor covers the three sectors <strong>in</strong> which Kenn<strong>is</strong>net <strong>is</strong> <strong>in</strong>terested:primary education, secondary education, and vocational education andtra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. When d<strong>is</strong>cuss<strong>in</strong>g research on primary education that does not<strong>in</strong>clude special education, we refer simply to primary education.In addition to survey<strong>in</strong>g the current state of affairs, the Monitor reviewswhat research has taught us about the benefits of ICT (Chapter 2). The <strong>Four</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> Monitor shows that we are gradually acquir<strong>in</strong>g more knowledgeof the effects of ICT. At the same time, th<strong>is</strong> publication also shows thatthere are still many questions concern<strong>in</strong>g the long-term benefits of ICT<strong>in</strong> education. By systematically generat<strong>in</strong>g new knowledge and provid<strong>in</strong>gthe latest <strong>in</strong>formation about what does and does not work, we aim tohelp schools select the ICT applications that will improve their pupils’performance. Such <strong>in</strong>formation can also help developers, educationalsupport staff, policymakers, and commercial parties meet the supportneeds of schools that utilize ICT.Sources<strong>What</strong> we know about the benefits of ICT <strong>is</strong> based on the results of<strong>in</strong>dependent research. A considerable percentage of that research has beencarried out on behalf of Kenn<strong>is</strong>net by various research <strong>in</strong>stitutions with<strong>in</strong>the context of the “Mak<strong>in</strong>g Knowledge of Value” [Kenn<strong>is</strong> van Waarde Maken]research program. Th<strong>is</strong> program also covers closely related researchprojects, for example “Learn<strong>in</strong>g with more effect” [Leren met meer effect],EXPO and EXMO (see also Chapter 2).To show how the current situation compares with previous years, wepresent comparative data collected <strong>in</strong> previous studies. We also use datataken from other Dutch and <strong>in</strong>ternational studies to help us understand13

the basic elements of the <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> model. Information on thesesources can be found <strong>in</strong> Chapter 10. Virtually all of the sources can also beconsulted via the Kenn<strong>is</strong>net website (onderzoek.kenn<strong>is</strong>net.nl).<strong>What</strong>’s new <strong>in</strong> 2011?The <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong> Monitor comb<strong>in</strong>es all the knowledge we have acquiredso far about the use of ICT <strong>in</strong> education. While the 2011 Monitor followsthe same structure as the 2010 Monitor, we have added new <strong>in</strong>formation.We have reta<strong>in</strong>ed any valid <strong>in</strong>sights ga<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> previous research anddeleted f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs that have become obsolete, especially where stat<strong>is</strong>ticaldata are concerned. We have also updated our survey of the research<strong>in</strong> Chapter 2 and added new <strong>in</strong>formation. Th<strong>is</strong> edition of the Monitortherefore supersedes previous editions.

2 - Benefits of us<strong>in</strong>g ICT2Benefits of us<strong>in</strong>g ICT<strong>What</strong> benefits can be derived from the balanced use of ICT <strong>in</strong>education? Th<strong>is</strong> chapter d<strong>is</strong>cusses the results of our research on thebenefits of ICTTh<strong>is</strong> year’s results confirm what we d<strong>is</strong>covered last year: that ICT makesteach<strong>in</strong>g more effective, efficient, and appeal<strong>in</strong>g. It should be noted,however, that ICT (or more ICT) <strong>is</strong> not always the best alternative. Schoolsand teachers should start by tak<strong>in</strong>g a good look at the circumstances <strong>in</strong>which it <strong>is</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g used. Po<strong>in</strong>ts to consider are the follow<strong>in</strong>g• It <strong>is</strong> better to be real<strong>is</strong>tic and set feasible goals.• The teacher plays a crucial role.• ICT ra<strong>is</strong>es new questions about pupil <strong>in</strong>dependence and the teacher’srole as a coach.• One size does not fit all: be sure to take differences <strong>in</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g styles<strong>in</strong>to account.• Coherence: relate the digital material to other material.After a brief description of the Kenn<strong>is</strong>net study (Section 2.1), wed<strong>is</strong>cuss the results by look<strong>in</strong>g at four learn<strong>in</strong>g strategies that are closelyassociated with pedagogical v<strong>is</strong>ion (Sections 2.2 – 2.6).2.1 Kenn<strong>is</strong>net’s research programTh<strong>is</strong> chapter presents a compilation of the results obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> Mak<strong>in</strong>gKnowledge of Value, Kenn<strong>is</strong>net’s research program. S<strong>in</strong>ce 2007, Kenn<strong>is</strong>nethas encouraged and funded research through th<strong>is</strong> program, specifically bysupport<strong>in</strong>g studies that <strong>in</strong>vestigate which strategies work when us<strong>in</strong>g ICT<strong>in</strong> education and which do not.The program <strong>is</strong> demand-driven and education-driven; <strong>in</strong> other words,the research <strong>is</strong> based on questions that schools themselves are ask<strong>in</strong>gregard<strong>in</strong>g the effectiveness of a pedagogical concept. For example, canan <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard enhance teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a way that helps pupilslearn more? And do pupils collaborate more closely if they make a videotogether? The program essentially welcomes any question concern<strong>in</strong>g thecontribution ICT makes to achiev<strong>in</strong>g educational objectives.15

We can describe research carried out on behalf of Kenn<strong>is</strong>net us<strong>in</strong>g the“knowledge pyramid” (Figure 2.1). The pyramid cons<strong>is</strong>ts of four levels:<strong>in</strong>spiration, ex<strong>is</strong>tence, perception, and evidence. Every <strong>in</strong>novation <strong>in</strong>education beg<strong>in</strong>s with an idea (<strong>in</strong>spiration). Some of these ideas canbe turned <strong>in</strong>to reality (ex<strong>is</strong>tence), and th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> where the <strong>Four</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Balance</strong>conditions play a crucial role. The job of the researcher <strong>is</strong> to clarifywhether ICT will actually help produce the <strong>in</strong>tended benefits, whetherteachers, pupils and parents recognize its added value (perception), andwhether pupils <strong>in</strong> fact really learn more (evidence).In other words, we beg<strong>in</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g knowledge at the bottom of thepyramid, with an <strong>in</strong>spired idea as to how ICT can improve education. Theidea <strong>is</strong> put <strong>in</strong>to practice and research exam<strong>in</strong>es whether it has lived upto expectations. The research results can <strong>in</strong> turn lead to better ideas, andto a new or adapted bottom level, for example by extend<strong>in</strong>g successfulprojects to <strong>in</strong>clude a larger group or try<strong>in</strong>g them out under otherconditions, and by learn<strong>in</strong>g from projects that did not demonstrate theadded value of ICT.Example: Read<strong>in</strong>g with a computer program thatreads texts out loud (Kurzweil)Evidence – confirmed benefitsPupils who learn to read us<strong>in</strong>g the read-aloudsoftware are more motivated and self-confidentPerception – perceived benefitsTeachers and pupils are enthusiastic; pupilsare very motivated and feel more confidentEx<strong>is</strong>tence – implementationPupils <strong>in</strong> groups 4 to 8 use Kurzweil softwarewhen they like, like a pair of read<strong>in</strong>g glassesInspiration – ideaPupils weak <strong>in</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g let the computer readthem texts (compensat<strong>in</strong>g)16Figure 2.1: The knowledge pyramidThe knowledge pyramid <strong>is</strong> made up of four hierarchical levels; each succeed<strong>in</strong>glevel has greater evidentiary value. An example <strong>is</strong> given on the right (Luyten,2011b). Th<strong>is</strong> example concerns a school that uses a text-to-speech program tohelp dyslexic pupils with their read<strong>in</strong>g. The pupils can have the program readtexts out loud to them. In the example, research has confirmed the school’sexpectations. The results may lead to the program be<strong>in</strong>g used more widely.

2 - Benefits of us<strong>in</strong>g ICTIn th<strong>is</strong> chapter, we show the relationship between the basic elementssurveyed <strong>in</strong> our research program, cluster those elements and draw overallconclusions. We beg<strong>in</strong> at the bottom of the pyramid, with the ideas. Wecategorize these accord<strong>in</strong>g to two important approaches to education:knowledge transfer and knowledge construction (expla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> Section 2.2).Th<strong>is</strong> allows us to sort out the prom<strong>is</strong><strong>in</strong>g ideas from the less prom<strong>is</strong><strong>in</strong>gones and map expectations concern<strong>in</strong>g the use of ICT <strong>in</strong> education. Weprovide only a brief description here of the studies on which we havebased our <strong>in</strong>sights. Readers who would like more <strong>in</strong>formation shouldconsult the bibliography at the end of th<strong>is</strong> publication and v<strong>is</strong>itonderzoek.kenn<strong>is</strong>net.nl/onderzoeken-totaal/overzicht. The various studiesare l<strong>is</strong>ted there.2.2 Classify<strong>in</strong>g ICT applications by pedagogical v<strong>is</strong>ionWe can roughly divide our <strong>in</strong>sights <strong>in</strong>to the benefits of ICT <strong>in</strong>to twocategories: ICT that supports knowledge transfer and ICT that supportsknowledge construction (OECD, 2009).Knowledge transfer <strong>is</strong> a pedagogical approach <strong>in</strong> which the teacherconveys knowledge to the pupil <strong>in</strong> small steps, with the emphas<strong>is</strong> be<strong>in</strong>gon repetition and practice. The teacher decides what pupils should learn,and when. An extreme example of knowledge transfer <strong>is</strong> a lecture or a“prepackaged” lesson.In knowledge construction, the teacher facilitates learn<strong>in</strong>g as part ofa process of <strong>in</strong>vestigation. The pupils are given the chance to acquireknowledge actively, <strong>in</strong>dependently and <strong>in</strong> collaboration with others bysearch<strong>in</strong>g for solutions. When assess<strong>in</strong>g pupil performance, the teacherlooks not only at what pupils have learned but also at how they havelearned it (Van Gennip, 2008).17

StructureTim<strong>in</strong>gEp<strong>is</strong>temologyClassroomsituationKnowledge transferOffer<strong>in</strong>g knowledge <strong>in</strong> a clearlydef<strong>in</strong>ed and structured (step-bystep)mannerTeacher (or computer) decideswhat knowledge pupils are givenand whenWell-def<strong>in</strong>ed and solvableproblems, with correct solutionsQuiet and concentration <strong>in</strong>classroom, attention focused onteacherKnowledge constructionFocus<strong>in</strong>g on the end product,facilitat<strong>in</strong>g the pupil’s processof <strong>in</strong>vestigationPupil directs learn<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>is</strong> anactive participant <strong>in</strong> knowledgeacqu<strong>is</strong>itionEncourag<strong>in</strong>g pupils to search fornew solutionsActive work attitude, work<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>dependently and <strong>in</strong> collaboration,not limited to classroomTest<strong>in</strong>g Pupils tested on content Assessment of learn<strong>in</strong>g processLearn<strong>in</strong>g objectiveAcquir<strong>in</strong>g a knowledge of factsand conceptsDevelop<strong>in</strong>g the ability toconceptualize and reasonTable 2.1: Compar<strong>in</strong>g knowledge transfer and knowledge construction (based on OECD, 2009,Chapter 4)Knowledge transfer and knowledge construction should be viewed asabstractions or idealizations (shown <strong>in</strong> Table 2.1). Pure forms seldomoccur <strong>in</strong> reality, however, and <strong>in</strong> the classroom, teachers tend to use both– although Chapter 4 will show that teachers express a certa<strong>in</strong> or even astrong preference for knowledge transfer. It <strong>is</strong> expected, however, thatknowledge construction will ga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> importance.Knowledge transfer and knowledge construction us<strong>in</strong>g ICTThe Kenn<strong>is</strong>net studies can easily be divided <strong>in</strong>to those concern<strong>in</strong>gknowledge transfer and those concern<strong>in</strong>g knowledge construction. It <strong>is</strong>useful to have a clear explanation of the difference between the twocategories. Knowledge transfer <strong>in</strong>cludes such strategies as “<strong>in</strong>struction”and “structured practice”; knowledge construction <strong>in</strong>cludes such strategiesas “<strong>in</strong>quiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>g” and “learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn” (which will beexpla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> detail <strong>in</strong> the sections below). ICT can be deployed <strong>in</strong> eachof these strategies but the objectives will differ and so will the benefits.Table 2.2 l<strong>is</strong>ts the four above-mentioned (ideal) strategies along with atypical example of each one and a typical learn<strong>in</strong>g objective.18

2 - Benefits of us<strong>in</strong>g ICTThe rest of th<strong>is</strong> chapter considers the follow<strong>in</strong>g question: what do we knowabout the added value of ICT for these four teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g strategies?Teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>gstrategyTypical example ofICT useLearn<strong>in</strong>g objectiveSeeTransfer Instruction Enrich<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>struction byus<strong>in</strong>g images on <strong>in</strong>teractivewhiteboardGa<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g newknowledge§ 2.3StructuredpracticeRepetition exerc<strong>is</strong>es ona computerConsolidat<strong>in</strong>gknowledge, mak<strong>in</strong>git automaticallyaccessible§ 2.4ConstructionInquiry-basedlearn<strong>in</strong>gPhysics computersimulationUnderstand<strong>in</strong>gand master<strong>in</strong>gpr<strong>in</strong>ciples§ 2.5Learn<strong>in</strong>g tolearnUs<strong>in</strong>g video and adigital portfolio toencourage reflectionControll<strong>in</strong>g one’sown learn<strong>in</strong>gprocess§ 2.6Table 2.2: <strong>Four</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g strategies and ICT use <strong>in</strong> each case (based on Lemke, 2006)2.3 ICT and <strong>in</strong>structionInstruction <strong>is</strong> the direct transfer of knowledge to a pupil, as it occurs <strong>in</strong>traditional classroom teach<strong>in</strong>g.A reasonably large body of research has confirmed that ICT can helpteachers transfer knowledge more effectively. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> particularly true formethods <strong>in</strong> which ICT adds someth<strong>in</strong>g to a teacher’s ex<strong>is</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g practices butdoes not change those practices fundamentally.Enhanc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>structionICT can help teachers enhance <strong>in</strong>struction by allow<strong>in</strong>g them to use v<strong>is</strong>ualsand audio, thereby <strong>in</strong>tensify<strong>in</strong>g the knowledge transfer process. Oneimportant lesson learned from previous research <strong>is</strong> that knowledge <strong>is</strong>transferred more effectively when v<strong>is</strong>uals and audio are comb<strong>in</strong>ed. Th<strong>is</strong>effect – known as the multimedia pr<strong>in</strong>ciple – has been confirmed byvarious studies (Mayer, 2002; Van G<strong>in</strong>kel, 2009; Bus, 2009).19

The <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard has proved to be an effective medium forenhanc<strong>in</strong>g traditional classroom <strong>in</strong>struction. Teachers who use v<strong>is</strong>uals,audio, and video on the whiteboard to enhance their traditional classroomlessons help pupils remember the material and are more likely to holdpupils’ attention. Another advantage <strong>is</strong> that the teacher can reuse digitallessons and post them <strong>in</strong> the electronic learn<strong>in</strong>g environment (ELE), sothat pupils can review the material later. The impact of an <strong>in</strong>teractivewhiteboard can be boosted by us<strong>in</strong>g vot<strong>in</strong>g panels, for example to checkwhether pupils have actually understood the material and to make lessonsmore <strong>in</strong>teractive (Lemke, 2009).The results of studies on the use of the <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard <strong>in</strong> digital<strong>in</strong>struction are therefore largely positive. Teachers and pupils aregenerally very enthusiastic about the <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard. Providedthey have a skilled teacher who has mastered the subject matter, thepedagogical methods, and the technology, pupils who receive <strong>in</strong>structionon the <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard do perform better (F<strong>is</strong>ser, 2007; Van Ast,2010; Heemskerk, 2010; Somekh, 2007; Marzano, 2009; Oberon, 2010).Texts read out loud by computerOne very different way of us<strong>in</strong>g ICT <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>struction <strong>is</strong> to program acomputer to read out loud. Primary schools <strong>in</strong> the Prov<strong>in</strong>ce of Gelderlandoffered dyslexic pupils a software program that read texts out loud. Th<strong>is</strong>turned out to work very well; it motivated pupils to read and helped buildtheir self-confidence (Luyten, 2011b).E-learn<strong>in</strong>gE-learn<strong>in</strong>g means read<strong>in</strong>g with the help of ICT when the relevantparticipants are not <strong>in</strong> the same location and ICT <strong>is</strong> used to bridge thed<strong>is</strong>tance between them. The lessons can be synchronous (at the same time)or asynchronous (not at the same time).Examples of synchronous learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>clude hav<strong>in</strong>g an expert address a classvia video-conferenc<strong>in</strong>g or d<strong>is</strong>tance teach<strong>in</strong>g for schools <strong>in</strong> regions withdecl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g populations (Van der Neut, 2008; Jonkman, 2008).20

2 - Benefits of us<strong>in</strong>g ICTA good example of asynchronous e-learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>is</strong> the Khan Academy(www.khanacademy.org/), which has more than 2000 <strong>in</strong>structional videosthat pupils can watch whenever it suits them.A more radical form of e-learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>is</strong> the digital tutor, an overall<strong>in</strong>struction program that pupils can work through with m<strong>in</strong>imal teacher<strong>in</strong>tervention. It <strong>is</strong> particularly popular <strong>in</strong> higher education (for examplethe Open University of the Netherlands), but primary schools are alsoexperiment<strong>in</strong>g with it. For example, some Dutch primary schools used adigital tutor for their Engl<strong>is</strong>h lessons (Hovius, 2010). The tutors guided thepupils through a series of topics <strong>in</strong> Engl<strong>is</strong>h on the <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard,address<strong>in</strong>g them <strong>in</strong> native-speaker-quality Engl<strong>is</strong>h. The pupils alsowatched films and carried out assignments. The pupils who had receivedlessons from the digital tutor were just as motivated and performed just aswell as the control group pupils who had been <strong>in</strong>structed by a teacher <strong>in</strong>the traditional manner.There <strong>is</strong> little evidence that such e-learn<strong>in</strong>g methods actually improveteach<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>g, however (Lemke, 2009). <strong>What</strong> <strong>is</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> <strong>is</strong> that theyrequire teachers to have outstand<strong>in</strong>g skills, for example so that they canma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> order <strong>in</strong> onl<strong>in</strong>e classes, check whether pupils understand thematerial, and relate the digital material to the regular material.2.4 Structured practiceThe po<strong>in</strong>t of knowledge transfer <strong>is</strong> to give pupils a solid knowledge base.Knowledge transfer <strong>in</strong>volves convey<strong>in</strong>g new knowledge to pupils (Section2.3), but it <strong>is</strong> also vital for that knowledge to “stick” and for pupils to beable to recall it immediately. The most suitable learn<strong>in</strong>g activity for th<strong>is</strong><strong>is</strong> practice (mak<strong>in</strong>g knowledge automatic). We def<strong>in</strong>e practic<strong>in</strong>g broadlyto mean the rote memorization of facts (such as words), the application oflearned rules (such as grammar rules) and skills exerc<strong>is</strong>es (such as learn<strong>in</strong>gto touch type).Positive results have been achieved with practice software, subject to theright conditions. A well-designed program should allow pupils to practice21

at their own level and should motivate them to review the material<strong>in</strong>formally, even <strong>in</strong> their own time. It should also be easy for teachers touse.Practice at one’s own levelOne advantage of practic<strong>in</strong>g on the computer <strong>is</strong> that the software canadapt the material dynamically to the pupil’s knowledge, skills and needs.A pert<strong>in</strong>ent example <strong>is</strong> the “Clever Cramm<strong>in</strong>g” software program [Slim-Stampen]. It <strong>is</strong> based on research show<strong>in</strong>g that we remember facts best ifwe review them when we have almost forgotten them. The ideal momentdiffers from one person to the next and depends partly on the pupil’sprior knowledge. Software programs are able to identify that moment to afair level of accuracy. “Clever Cramm<strong>in</strong>g” uses a pupil’s reaction speed todecide whether or not an exerc<strong>is</strong>e needs to be repeated. Studies show thatpupils who work with th<strong>is</strong> software do <strong>in</strong> fact remember facts better thanthose who decide for themselves when to study a l<strong>is</strong>t of words (Van Rijn,2009).A computer program <strong>is</strong> also better than a worksheet at provid<strong>in</strong>g pupilswith extra tutor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> areas <strong>in</strong> which they are weak. One example <strong>is</strong> ahomework program <strong>in</strong> language and math [Mu<strong>is</strong>werk] that not only givespupils exerc<strong>is</strong>es to do, but also offers them new material. It gives pupilsdirect feedback and keeps track of which material they have and havenot mastered. Small-scale quasi-experimental research shows that pupilsare capable of work<strong>in</strong>g on such exerc<strong>is</strong>es <strong>in</strong>dependently and complet<strong>in</strong>gspell<strong>in</strong>g and read<strong>in</strong>g comprehension assignments with the help of anass<strong>is</strong>tant teacher (Meijer, 2009).22Informal learn<strong>in</strong>gPrimary schools are mak<strong>in</strong>g grow<strong>in</strong>g use of Smart Boards (a brand of<strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard) or SkoolMates (computers designed especially forchildren), with pupils (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g pre-schoolers) us<strong>in</strong>g them to complete<strong>in</strong>teractive exerc<strong>is</strong>es or play educational games. The pupils do notlearn any better than pupils who do not have access to these tools, butteachers feel that they enhance their lessons and extend their pedagogicalrepertoire (Luyten, 2011; Heemskerk, 2011).

2 - Benefits of us<strong>in</strong>g ICTOne good example of us<strong>in</strong>g ICT for <strong>in</strong>teractive practice <strong>is</strong> an experimentcarried out at De Arabesk primary school <strong>in</strong> Arnhem. Pupils there worked<strong>in</strong> twos to complete math exerc<strong>is</strong>es on the <strong>in</strong>teractive whiteboard. Thesums were designed to get pupils actively <strong>in</strong>volved: they required them todrag parts of the equation from one place to another, take turns writ<strong>in</strong>gon the whiteboard, consult one another and figure th<strong>in</strong>gs out together.They also required pupils to stretch out their arms <strong>in</strong> order to fill <strong>in</strong> ananswer or po<strong>in</strong>t to someth<strong>in</strong>g. The study showed that pupils did <strong>in</strong>deedget actively <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> do<strong>in</strong>g the sums, used <strong>in</strong>quiry-based methods,collaborated a great deal, and enjoyed work<strong>in</strong>g on the assignments. Theyalso performed better (Coetsier, 2009).A grow<strong>in</strong>g number of practice programs now use the same motivationtechniques applied <strong>in</strong> commercial games, for example tension andcompetition. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> prov<strong>in</strong>g to be successful. Children who practice theirsums on a gam<strong>in</strong>g computer are better at math and do sums more quickly(Luyten, 2011b), and the results of the Farmville-like Math Garden gamealso look prom<strong>is</strong><strong>in</strong>g (Heemskerk, 2011). Both games have a competitiveelement and require pupils to work under time pressure (for example tocreate the nicest possible garden <strong>in</strong> the shortest time possible).Ease of usePrimary schools <strong>in</strong> Emmen compared tests given on paper with digitaltests and came to the follow<strong>in</strong>g conclusions: digital tests are a reliablereplacement for tests on paper, save time, and are easy to use (Luyten,2011j).Underly<strong>in</strong>g conditionsTeachers who have their pupils practice at their own level on the computerneed to know when those pupils require extra help or support and whenthey do not. After all, the advantage of computer software <strong>is</strong> that it <strong>is</strong> thecomputer that decides who <strong>is</strong> given what material to practice and when.Not every teacher likes that. Effective use of computers means that theteacher must familiarize him or herself with a new role, but it also meansthat the computer program must live up to expectations.23

2 - Benefits of us<strong>in</strong>g ICTfor example, they must be able to use the words they have learned <strong>in</strong> alanguage-rich context (Suhre, 2008; Corda, 2010).In short, it <strong>is</strong> prec<strong>is</strong>ely when ICT enables pupils to work more<strong>in</strong>dependently, that pupils <strong>in</strong> fact need the teacher’s <strong>in</strong>put more than ever.ICT does not replace the teacher but rather creates new relationships,between the pupil, the subject matter, the ICT application itself, and theteacher. It ra<strong>is</strong>es questions about the balance between pupils work<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>dependently, the amount of control exerc<strong>is</strong>ed by the software, and theamount of control that the teacher has over the learn<strong>in</strong>g process.2.5 Inquiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>gInquiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>g means teach<strong>in</strong>g methods <strong>in</strong> which pupils are moreor less free to look up the answer to a question, search for <strong>in</strong>formationabout a topic, study a concept, or develop skills. The problems they aretold to <strong>in</strong>vestigate are often complex ones that can be answered <strong>in</strong> severalways. The process – that <strong>is</strong>, how the pupil arrives at the solution – <strong>is</strong> oneof the learn<strong>in</strong>g objectives.ICT can offer considerable advantages <strong>in</strong> th<strong>is</strong> respect, but as <strong>in</strong> the caseof practice programs, applications that support <strong>in</strong>quiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>grequire at the very least a prec<strong>is</strong>e, professional, and pedagogicallyrelevant design…as well as the constant attention of the teacher.Computer simulationsComputer simulations enable pupils to experiment <strong>in</strong> an environment –a model – that imitates reality. They give pupils the chance to developpractical skills, for example learn<strong>in</strong>g about dredg<strong>in</strong>g with a dredg<strong>in</strong>gsimulator (Oomens, 2011), or to familiarize themselves with the basicpr<strong>in</strong>ciples of research, such as develop<strong>in</strong>g a hypothes<strong>is</strong> (De Jong, 2009).Games may also be classified as computer simulations. Some games aredeveloped especially for the education sector, but pupils can even learnfrom store-bought games if they have a good teacher (Van Rooij, 2010a;Verheul, 2009; Claessens, 2011a).25

Pupils learn skills and acquire knowledge <strong>in</strong> simulations. The simulationsmust have a properly balanced design, however – not too structuredand not too amorphous. Pupils must have sufficient prior knowledgeto make any headway <strong>in</strong> such an environment, and the simulation itselfmust provide scaffolded <strong>in</strong>struction, i.e. support the pupils and offerthem sufficient guidance (Hagemans, 2008; Van de Schaar, 2009). It takestime to develop a powerful simulation or game. It <strong>is</strong> also expensive andrequires considerable professional expert<strong>is</strong>e, with technicians, designers,pedagogical experts, and subject special<strong>is</strong>ts all work<strong>in</strong>g together (De Jong,2009a).One unusual example of a simulation <strong>is</strong> a four-dimensional globe that canmove backwards and forwards <strong>in</strong> time and accurately represents the world<strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>iature (cities, countries, oceans). Pupils were allowed to use theglobe to learn topography. Th<strong>is</strong> did not work very well, however; pupilsmade better progress study<strong>in</strong>g a textbook, <strong>in</strong> part because the globe wasnot designed for th<strong>is</strong> particular purpose and could not be used efficiently(Luyten, 2011g).Mean<strong>in</strong>gful contextThe best context for <strong>in</strong>quiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>is</strong> one that <strong>is</strong> rich andmean<strong>in</strong>gful. ICT can provide such a context. Pupils at a primary school, forexample, used a digital sensor when study<strong>in</strong>g various subjects to measurelight, sound and temperature (Luyten, 2011a). Other pupils <strong>in</strong> preparatoryvocational education who wanted to specialize <strong>in</strong> ICT were given studymaterial <strong>in</strong> basic subjects (such as Dutch and mathematics) that had been<strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong>to vocational subjects (Claessens, 2011b). In yet anotherexample, a mobile phone was used to bridge the d<strong>is</strong>tance between formallearn<strong>in</strong>g at school and <strong>in</strong>formal learn<strong>in</strong>g outside the classroom (Sandberg,2010). In none of these cases did the use of ICT <strong>in</strong> a mean<strong>in</strong>gful contextproduce additional learn<strong>in</strong>g effects. Additional effects were found,however, when pupils downloaded educational games to their mobilephones. Because they were allowed to take the phones home with them,they cont<strong>in</strong>ued play<strong>in</strong>g the games after school hours and consequently gotbetter marks.26

2 - Benefits of us<strong>in</strong>g ICTSearch<strong>in</strong>g the InternetThe Internet <strong>is</strong> an almost <strong>in</strong>exhaustible source of <strong>in</strong>formation and as such<strong>is</strong> used a great deal <strong>in</strong> education (Figure 2.2).Pupils surf<strong>in</strong>g the Internet% of pupils100858060584340200PRIMSECVETFigure 2.2: Percentage of pupils who teachers say make at least weekly use of the Internetat school for educational purposes (TNS NIPO, 2010)The Internet <strong>is</strong> not always a good learn<strong>in</strong>g environment, however. Pupilsseldom subject Internet sources to a critical evaluation. They ma<strong>in</strong>ly lookat whether the <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>is</strong> available <strong>in</strong> Dutch, whether the site cananswer their question quickly, and whether it looks attractive. Informationskills are <strong>in</strong>d<strong>is</strong>pensable if the po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>is</strong> to ga<strong>in</strong> knowledge from theInternet (Kuiper, 2007; Walraven, 2008; 2011), but so far, schools have notattempted to teach pupils such skills <strong>in</strong> any systematic fashion (see Box).One good way to help pupils acquire the necessary <strong>in</strong>formation skills <strong>is</strong> bymeans of webquests (Droop, 2011).27

The debate concern<strong>in</strong>g the importance of <strong>in</strong>formation skillsand twenty-first century skillsThe examples given <strong>in</strong> Chapter 2 concern ICT applications that supportteach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g, for example a practice program, a digital portfolio, orthe Internet. But to use such applications, pupils must have the necessaryskills, i.e. ICT or <strong>in</strong>formation skills. Information skills are so fundamental,both <strong>in</strong> educational sett<strong>in</strong>gs and <strong>in</strong> society <strong>in</strong> general, that they havebecome the subject of a major <strong>in</strong>ternational debate. <strong>What</strong> skills are wetalk<strong>in</strong>g about, and why are they so important?It <strong>is</strong> not entirely clear which skills are thought to be <strong>in</strong>formation skills. Inthe most general sense, they cons<strong>is</strong>t of all the skills that allow us to use ICTeffectively <strong>in</strong> order to function normally <strong>in</strong> today’s ICT-driven knowledgesociety. Th<strong>is</strong> goes further than basic skills such as read<strong>in</strong>g comprehensionor ICT skills such as the ability to use a computer. Information skills also<strong>in</strong>clude skills that enable us to deal responsibly, critically and creativelywith ICT (Van den Berg, 2010; Boelens, 2010; Maddux, 2009; Van Vliet,2011). Someone who has <strong>in</strong>formation skills <strong>is</strong> aware of security r<strong>is</strong>ks,can evaluate sources, and can produce <strong>in</strong>formation himself. He <strong>is</strong> also,however, aware of the ethical and legal aspects associated with the use ofICT and with <strong>in</strong>formation d<strong>is</strong>sem<strong>in</strong>ated on the Internet and through socialmedia. These wide-rang<strong>in</strong>g skills are sometimes referred to as “twentyfirstcentury skills” (Voogt, 2010b).Information skills are becom<strong>in</strong>g more and more important. It <strong>is</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly clear, both <strong>in</strong> the Netherlands and abroad, that <strong>in</strong>formationskills are set to become the “new literacy” that every person must master(Anderson, 2008; Johnson, 2010). That means that <strong>in</strong>formation skills willsoon be just as vital as read<strong>in</strong>g, writ<strong>in</strong>g, and arithmetic. Anyone who hasnot mastered <strong>in</strong>formation skills will be at r<strong>is</strong>k of becom<strong>in</strong>g marg<strong>in</strong>alized(European Comm<strong>is</strong>sion, 2010; OECD, 2010a; Anderson, 2008; Boelens, 2010;Ten Brummelhu<strong>is</strong>, 2010).28

2 - Benefits of us<strong>in</strong>g ICTThe education sector has not concerned itself with th<strong>is</strong> problem <strong>in</strong> anycons<strong>is</strong>tent manner. It <strong>is</strong> wrongly assumed that youngsters are so handywith computers that schools do not need to teach them how to search forand select <strong>in</strong>formation on the Internet. By way of illustration: a recentstudy has shown that only one out of five primary and secondary schoolteachers gives frequent or very frequent lessons on us<strong>in</strong>g Internet sourcesselectively (Van Gennip, 2011a; 2011b).That means that pupils’ digital literacy currently depends ma<strong>in</strong>ly on thesituation at home and what their school happens to teach them. Unlikemost of the other European Union Member States (Eurydice, 2011), theNetherlands has not def<strong>in</strong>ed learn<strong>in</strong>g objectives for the digital skills thatyoung people need to survive <strong>in</strong> the twenty-first century.Studies are mak<strong>in</strong>g it <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly clear, however, that many pupils are<strong>in</strong>capable of us<strong>in</strong>g the Internet effectively as a learn<strong>in</strong>g resource (OECD,2010a; Walraven, 2011). In other words, we tend to overestimate pupils’computer skills (Kanters, 2009). Although many pupils have mastered anumber of ICT skills, that does not mean that they are capable of us<strong>in</strong>g ICTto learn or of us<strong>in</strong>g it responsibly, critically, and creatively.2.6 Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn“Learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn” covers various teach<strong>in</strong>g methods that focus primarilyon the pupil’s learn<strong>in</strong>g process and h<strong>is</strong> or her awareness of that process.The content <strong>is</strong> subord<strong>in</strong>ate to the process. There <strong>is</strong> some overlap betweenlearn<strong>in</strong>g to learn and <strong>in</strong>quiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>g.We still know too little about the added value of applications that supportth<strong>is</strong> type of learn<strong>in</strong>g. Schools are experiment<strong>in</strong>g with ICT <strong>in</strong> th<strong>is</strong> respect,but the work<strong>in</strong>g methods are still too open-ended to study their effects.29

Competence-based professional environmentsEnvironments that simulate professional sett<strong>in</strong>gs are particularly <strong>in</strong>demand <strong>in</strong> vocational education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g because they allow pupils tocarry out the duties that they will have to perform later <strong>in</strong> their careers(see also Chapter 3). Among the key learn<strong>in</strong>g objectives are the pupil’sability to plan and control h<strong>is</strong> or her own learn<strong>in</strong>g process.One example of such an environment <strong>is</strong> Schonenvaart. In th<strong>is</strong> simulation,pupils take on the role of an account manager and carry out a number ofassignments. The effectiveness of the environment has been shown to belimited. Pupils do not see the relevance of the assignments, those whohave trouble plann<strong>in</strong>g and who do not feel motivated show no improvementon these po<strong>in</strong>ts, and only a small percentage of the assignments are everhanded <strong>in</strong>. In particular, the environment offers pupils who are alreadyhav<strong>in</strong>g trouble at school very few benefits. It puts enormous demands onthe teacher’s time and energy because he or she must cont<strong>in</strong>ue to monitorpupils closely (Coetsier, 2008). We can draw similar conclusions from astudy carried out by Dieleman (2010) <strong>in</strong>to projects concern<strong>in</strong>g “mean<strong>in</strong>gfullearn<strong>in</strong>g” and the real<strong>is</strong>tic learn<strong>in</strong>g environment LINK2 (Coetsier, 2011).Once aga<strong>in</strong>, it was not easy to put the <strong>in</strong>tended teach<strong>in</strong>g method <strong>in</strong>topractice; pupils became demotivated, and the results were d<strong>is</strong>appo<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g.Reflection and ICTWhen teachers apply methods that focus on knowledge construction, it <strong>is</strong>important that their pupils th<strong>in</strong>k about how they themselves learn andacquire general skills. Schools are experiment<strong>in</strong>g with various ICT toolsthat will stimulate such reflection skills.One such tool <strong>is</strong> the digital portfolio. Pupils save their work there, receivefeedback on their assignments, and can see at a glance where they stand.Some schools are extend<strong>in</strong>g such applications by giv<strong>in</strong>g all their pupils alaptop, so that they can access their digital portfolio whenever they like(Weijs, 2010).30Other methods that stimulate reflection <strong>in</strong>volve hav<strong>in</strong>g pupils record theirpresentation on video and d<strong>is</strong>cuss it with their classmates (Verbeij, 2009),or hav<strong>in</strong>g them keep a weblog (see Wopere<strong>is</strong>, 2009).

2 - Benefits of us<strong>in</strong>g ICTThere have been only a few studies <strong>in</strong>to such tools. Because many of theapplications are still <strong>in</strong> the draw<strong>in</strong>g board stage, the po<strong>in</strong>t of the research<strong>is</strong> usually to come up with a work<strong>in</strong>g design. As for research <strong>in</strong>vestigat<strong>in</strong>gthe applications’ benefits, the results have so far been ambiguous. Oneexperiment <strong>in</strong> which pupils used a digital video camera to produce theirown school news program did not demonstrably improve their knowledgeor skills (Luyten, 2011e). Neither did the use of digital portfolios produceany demonstrable benefits (see for example the study <strong>in</strong>to digitalportfolios <strong>in</strong> Meijer, 2009 or the study by Van Gennip, 2009), although thatcould be because the digital portfolios studied were not entirely functionalyet. In addition, the learn<strong>in</strong>g objectives for these applications are notalways clearly def<strong>in</strong>ed, mak<strong>in</strong>g it difficult to assess their effects.Computer-supported collaborative learn<strong>in</strong>gWillemsen asked teachers to consider five situations <strong>in</strong> which pupils wereengaged <strong>in</strong> computer-supported collaborative learn<strong>in</strong>g (CSCL), rang<strong>in</strong>gfrom relatively simple arrangements where pupils sat down together at acomputer to more complex arrangements where pupils collaborated whileeach one was at home work<strong>in</strong>g on h<strong>is</strong> or her own computer. Teachersdoubted whether such applications would be effective; they felt they didnot have enough control over the learn<strong>in</strong>g situation and did not see CSCLas be<strong>in</strong>g of equal value to a normal lesson situation (Willemsen, 2010).2.7 Summary• ICT can make teach<strong>in</strong>g/learn<strong>in</strong>g more efficient, more effective, and more<strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g. Whether it <strong>in</strong> fact does so depends on how well the teacher<strong>is</strong> able to l<strong>in</strong>k the subject matter, the ICT application, and the pupil.• ICT has generally been found to produce greater results when usedfor knowledge transfer (<strong>in</strong>struction, practice) than for knowledgeconstruction (<strong>in</strong>quiry-based learn<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>g to learn). In termsof the knowledge pyramid, many of the applications <strong>in</strong>tended forknowledge construction have not gone beyond the <strong>in</strong>spiration andex<strong>is</strong>tence stages. Applications <strong>in</strong>tended for knowledge transfer are morelikely to reach the perceived benefits and evidence stages. However,the benefits may be easier to perceive because the learn<strong>in</strong>g objectivesassociated with knowledge transfer are more clearly def<strong>in</strong>ed andbecause there are more proven assessment <strong>in</strong>struments available.31

• ICT can be conducive to knowledge transfer, as many examples show.The various applications share a number of features: they do notfundamentally alter teach<strong>in</strong>g, for example, and are relatively lowthreshold. For example, ICT adds someth<strong>in</strong>g (such as v<strong>is</strong>ual material)or replaces part of the lesson (the practice worksheet). Even so, suchapplications often take more time and energy than teachers may atfirst expect, especially if the computer takes over part of the teach<strong>in</strong>gprocess (as <strong>in</strong> the case of a practice program).• In terms of knowledge construction, ICT <strong>is</strong> still largely unexploredterritory and its added value <strong>is</strong> more difficult to demonstrate.Designers are wrestl<strong>in</strong>g with such questions as: how much structureand guidance should an environment give pupils, and how can teacherscontrol a learn<strong>in</strong>g process that takes place on a computer or network?When ICT was first <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong> education, the suggestion was made thatICT might at some po<strong>in</strong>t even replace teachers. Research results <strong>in</strong>dicatethat the opposite <strong>is</strong> true. The more powerful the ICT tool, the more<strong>in</strong>d<strong>is</strong>pensable the teacher. ICT creates a new relationship between pupils,subject matter, and teachers, forc<strong>in</strong>g us to exam<strong>in</strong>e the balance betweenthe work that the pupil does on h<strong>is</strong> own, how much the software controlsthat work, and how much the teacher controls the pupil’s learn<strong>in</strong>g process.The latter makes huge demands on teachers: they must keep a close eyeon the progress of pupils work<strong>in</strong>g on their own, take pupils’ differ<strong>in</strong>glearn<strong>in</strong>g styles <strong>in</strong>to account, and show pupils how the material they arestudy<strong>in</strong>g on the computer relates to other learn<strong>in</strong>g material.32

3 - ICT <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g3ICT <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>gIt <strong>is</strong> no longer possible to imag<strong>in</strong>e teach<strong>in</strong>g without ICT. Althoughcomputer use has not become as widespread as teachers and schoolmanagers had expected, teachers still assume that their use of ICTwill <strong>in</strong>crease exponentially <strong>in</strong> the years ahead, not only at school butalso when do<strong>in</strong>g school-related work at home.Section 3.1 looks at how teachers utilize ICT <strong>in</strong> their teach<strong>in</strong>g. Theyuse the computer for other school-related work as well, which they<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly do at home (Section 3.2). Pupils also use their home computerregularly for school assignments, for example to look up <strong>in</strong>formation(Section 3.3).3.1 Teachers at schoolWe know that many teachers use computers <strong>in</strong> their lessons, but how, andhow often? The Monitor looks at three different <strong>in</strong>dicators:1. Number: how many teachers use computers?2. Frequency: how often do they use computers?3. Variety: what do they use computers for?Teachers’ computer use% of teachers100918072605940200PRIMSECVETFigure 3.1: Percentage of teachers who use computers dur<strong>in</strong>g lessons, accord<strong>in</strong>g to schoolmanagers (TNS NIPO, 2010)33

NumberThree quarters of teachers use computers dur<strong>in</strong>g lessons. Figure 3.1 showsthat more primary school teachers use computers (91%) than teachers atsecondary schools (59%) or vocational schools (72%).The number of teachers us<strong>in</strong>g computers <strong>in</strong> their lessons has <strong>in</strong>creased by2 to 3% <strong>in</strong> the past eight years. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> a much slower rate of growth ( 50%)than school managers had forecast. School managers estimate that the rateof growth will r<strong>is</strong>e to more than 4% <strong>in</strong> the years ahead (Figure 3.2), but eventhen, it will take at least five years before all teachers are mak<strong>in</strong>g use ofcomputers <strong>in</strong> their lessons.Trend <strong>in</strong> teachers’ computer use% of teachersForecast10080604020020032004200520062007200820092010201120122013201456 62 66 66 67 70 72 74 74 88Note: Data for 2003-2007 based on PRIM and SEC. Data from 2008 onward concern PRIM,SEC and VET.Figure 3.2: Trend <strong>in</strong> average percentage of teachers who use computers <strong>in</strong> their lessons,accord<strong>in</strong>g to school managers (TNS NIPO, 2003-2010)34

3 - ICT <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>gFrequencyTeachers use computers <strong>in</strong> their lessons for an average of 8 hours a week.Th<strong>is</strong> figure <strong>is</strong> the same as last year’s. Teachers forecast that the amount ofthe lesson time spent us<strong>in</strong>g computers will <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the next three yearsby approximately 40%, to an average of 11 hours a week (Figure 3.3).Teachers’ computer use, <strong>in</strong> hoursNumber of hours per weekForecast12108642020082009201020112012201320147 7 8 8 11Figure 3.3: Average number of hours a week that teachers <strong>in</strong> primary, secondary andvocational education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g use computers <strong>in</strong> their lessons, and forecast for the nearfuture (TNS NIPO, 2010)35

The number of lesson hours <strong>in</strong> which computers are used differs fromone sector to the next (Figure 3.4). Computers are used most <strong>in</strong> vocationaleducation and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g (10 hours per week), not merely as a pedagogicaltool but also to help pupils prepare for their careers. For example, pupils<strong>in</strong> secretarial school learn to use word process<strong>in</strong>g programs, and pupilstra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to be assembly technicians <strong>in</strong> the metalwork<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dustry learn touse a computer-controlled lathe. Observations of 400 lessons <strong>in</strong> vocationaleducation and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g reveal that 40% of the hours devoted to ICT focuson computer applications used <strong>in</strong> the occupations for which the pupils arebe<strong>in</strong>g tra<strong>in</strong>ed (Plant<strong>in</strong>ga, 2011).Secondary school teachers make the least use of computers, relativelyspeak<strong>in</strong>g (6 hours a week). Primary school teachers use computers for anaverage of 8 hours a week <strong>in</strong> their lessons. As mentioned above, teachers<strong>in</strong> all three sectors expect that they will make much more use of ICT <strong>in</strong> theyears ahead.Teachers’ current and future computer use, <strong>in</strong> hoursNumber of hours per weekNowIn three years’ time14121086812691013420PRIMSECFigure 3.4: Average number of hours a week that teachers use computers <strong>in</strong> their lessons,and forecast for the near future (TNS NIPO, 2010)VET36

3 - ICT <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>gVarietyThe ICT applications used most often <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g are the Internet, practiceprograms, word process<strong>in</strong>g software and electronic learn<strong>in</strong>g environments.On average, teachers use such applications eight times a month. They makethe least use of gam<strong>in</strong>g and Web 2.0 (Figure 3.5) and have an average offive different ICT applications <strong>in</strong> their pedagogical repertoire.ICT applicationsLook up <strong>in</strong>formation on Internet 9Practice program 8Word process<strong>in</strong>g 7ELE 8Cooperation 7Plann<strong>in</strong>g 4Test<strong>in</strong>g 2Portfolio 2Games 2Web 2.0 2353332304756807872670 20 40 60 80 100Number of times a month% of teachersFigure 3.5: Percentage of primary, secondary and vocational school teachers who use ICTapplications once a month or more dur<strong>in</strong>g lessons and average number of times a month thatthey use such applications (TNS NIPO, 2010)37

3.2 Teachers at homeVirtually all teachers use their home computers for school-related work(Figure 3.6), ma<strong>in</strong>ly for adm<strong>in</strong><strong>is</strong>trative tasks and to search for, adapt, ordevelop lesson materials. They also often use their home computer to keep<strong>in</strong> touch with colleagues or pupils.Teachers use their home computers for school-related work an averageof seven hours a week, or one hour less than at school. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>in</strong>formationemphasizes that computers represent more to teachers than only apedagogical tool used <strong>in</strong> their lessons.Teachers’ computer use at school and at homeNumber of hours per week201577 710578 8At homeAt school0200920102011Figure 3.6: Average number of hours a week that primary, secondary and vocational schoolteachers use their home and school computers for school-related work (TNS NIPO, 2010)38

3 - ICT <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g3.3 Pupils at homeLimitsTeachers believe that the amount of time that pupils can learn effectivelyat a school computer <strong>is</strong> limited to a maximum of 8 to 15 hours a week(Figure 3.7). That <strong>is</strong> an average of about 1.5 to 3 hours a day.The number of hours a week that pupils can learn effectively at a home orschool computer varies from 22 to 27 hours a week for secondary schooland vocational education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Teachers expect that primary schoolpupils can learn effectively at a home or school computer for 15 hours aweekMaximum computer time for learn<strong>in</strong>gNumber of hours per weekAt homeAt school3025201215101075812150PRIMSECFigure 3.7: Number of hours a week that pupils can learn effectively at a computer, accord<strong>in</strong>gto teachers (TNS NIPO, 2010)VET39

Actual useHomework assignments that pupils do on their home computers are mostcommon <strong>in</strong> vocational education and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, accord<strong>in</strong>g to teachers. Suchassignments are very rare <strong>in</strong> primary education (Figure 3.8).Homework assignments on computer% of teachers1008060402002008200920102011PRIM 13 14 11 15SEC 39 39 44 38VET 61 65 68 72Figure 3.8: Percentage of teachers who give pupils at least one assignment a week to completeon their home computers (TNS NIPO, 2008-2010)The vast majority of secondary school pupils (80%) say that when theyuse the Internet at home to do schoolwork, they use it ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> the sameway as they do at school, i.e. to search for <strong>in</strong>formation. More than half ofpupils (59%) also say that ICT makes it possible for them to collaboratewith other pupils on school assignments from home.40

3 - ICT <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>gThe biggest change <strong>in</strong> recent years <strong>is</strong> that pupils have begun submitt<strong>in</strong>gtheir homework assignments by e-mail. The number of pupils who do th<strong>is</strong>has r<strong>is</strong>en from 24% to 34%. Pupils are also <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly us<strong>in</strong>g the Internetto f<strong>in</strong>d out what homework has been assigned (via the school’s ELE) (VanRooij, 2010b). The school-related activities that pupils perform from homeon the Internet are l<strong>is</strong>ted <strong>in</strong> Table 3.1.School-related activity % of pupils 2008 2009 2010 2011Search<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>in</strong>formation 73 79 83 80Work<strong>in</strong>g on assignments with other pupils 45 52 60 59Contact with fellow pupils regard<strong>in</strong>gschoolwork37 36 36 32Tak<strong>in</strong>g practice tests 31 25 27 27Submitt<strong>in</strong>g homework by e-mail 20 22 24 34Check<strong>in</strong>g what homework has beenassigned13 19 21 28Ask<strong>in</strong>g the teacher a question by e-mail 11 11 17 20Construct<strong>in</strong>g and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a website 9 9 7 4Ask<strong>in</strong>g an expert a question by e-mail 6 6 6 5F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g ready-made assignments to copy 4 5 6 4Note: Th<strong>is</strong> table <strong>is</strong> based on <strong>in</strong>formation provided by pupils <strong>in</strong> their first and second years ofsecondary school (appr. 12-13 years of age)Table 3.1: School-related activities that pupils have performed from home on the Internet <strong>in</strong>recent months (Van Rooij, 2010b)41

Learn<strong>in</strong>g at school and at homeWe see that teachers have their pupils use ICT <strong>in</strong> various ways outside ofschool. In other words: ICT adds to the time pupils spend learn<strong>in</strong>g becausethey are given more opportunity to learn outside of school hours.Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicates that teachers use ICT to bridge the gap between formallearn<strong>in</strong>g (at school) and <strong>in</strong>formal learn<strong>in</strong>g (outside school). Various studieshave conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>gly demonstrated the value of do<strong>in</strong>g so. Examples aredescribed <strong>in</strong> greater detail <strong>in</strong> Chapter 2; they concern learn<strong>in</strong>g Engl<strong>is</strong>hwith a mobile phone, practic<strong>in</strong>g words <strong>in</strong> a foreign language, and us<strong>in</strong>gcomputers to teach basic math pr<strong>in</strong>ciples and as a vocabulary-build<strong>in</strong>g toolfor young children. Such applications show that ICT makes learn<strong>in</strong>g moreappeal<strong>in</strong>g. Many teachers expect that ICT therefore motivates pupils tostudy harder and longer, ultimately improv<strong>in</strong>g their performance at school(Van den Brande, 2010).

3 - ICT <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g3.4 Summary• Three quarters of teachers use computers dur<strong>in</strong>g lessons. Th<strong>is</strong> numberhas <strong>in</strong>creased by 2 to 3% <strong>in</strong> recent years.• Teachers spend an average of 8 hours a week us<strong>in</strong>g computers <strong>in</strong>their lessons, and expect that figure to <strong>in</strong>crease with<strong>in</strong> three years byapproximately 40%, to 11 hours a week. In addition, teachers spendanother 7 hours a week on average do<strong>in</strong>g school-related work on theirhome computer.• The ICT applications used most often <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g are the Internet,practice programs, word process<strong>in</strong>g software and electronic learn<strong>in</strong>genvironments. Games and Web 2.0 are the least popular applications.• On average, teachers have five different ICT applications <strong>in</strong> theirpedagogical repertoire.• Teachers believe that the number of hours that pupils can spendwork<strong>in</strong>g at a computer at school <strong>is</strong> limited to between 1.5 and 3 hoursa day. Teachers believe that pupils can spend a further 7 to 12 hours aweek on learn<strong>in</strong>g activities outside of school hours.43