California Quick Reference Chart and Notes - ILRC

California Quick Reference Chart and Notes - ILRC

California Quick Reference Chart and Notes - ILRC

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

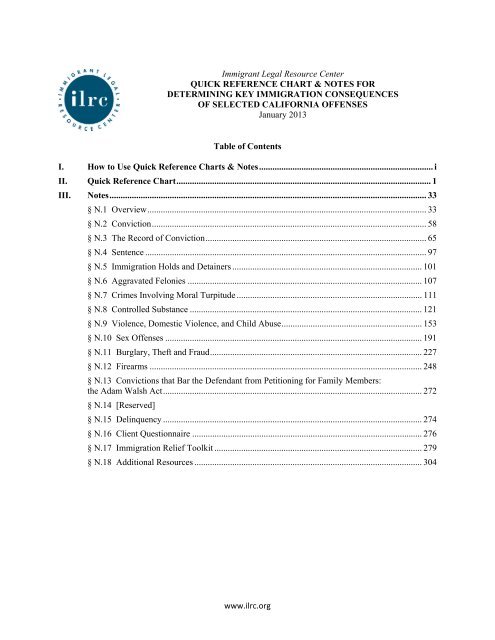

Immigrant Legal Resource CenterQUICK REFERENCE CHART & NOTES FORDETERMINING KEY IMMIGRATION CONSEQUENCESOF SELECTED CALIFORNIA OFFENSESJanuary 2013Table of ContentsI. How to Use <strong>Quick</strong> <strong>Reference</strong> <strong>Chart</strong>s & <strong>Notes</strong> .............................................................................. iII. <strong>Quick</strong> <strong>Reference</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> .................................................................................................................. 1III. <strong>Notes</strong> .............................................................................................................................................. 33§ N.1 Overview ............................................................................................................................. 33§ N.2 Conviction ........................................................................................................................... 58§ N.3 The Record of Conviction ................................................................................................... 65§ N.4 Sentence .............................................................................................................................. 97§ N.5 Immigration Holds <strong>and</strong> Detainers ..................................................................................... 101§ N.6 Aggravated Felonies ......................................................................................................... 107§ N.7 Crimes Involving Moral Turpitude ................................................................................... 111§ N.8 Controlled Substance ........................................................................................................ 121§ N.9 Violence, Domestic Violence, <strong>and</strong> Child Abuse ............................................................... 153§ N.10 Sex Offenses ................................................................................................................... 191§ N.11 Burglary, Theft <strong>and</strong> Fraud ............................................................................................... 227§ N.12 Firearms .......................................................................................................................... 248§ N.13 Convictions that Bar the Defendant from Petitioning for Family Members:the Adam Walsh Act .................................................................................................................... 272§ N.14 [Reserved]§ N.15 Delinquency .................................................................................................................... 274§ N.16 Client Questionnaire ....................................................................................................... 276§ N.17 Immigration Relief Toolkit ............................................................................................. 279§ N.18 Additional Resources ...................................................................................................... 304www.ilrc.org

How to Use the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Notes</strong>January 2013, www.ilrc.orgHow to Use the<strong>Quick</strong> <strong>Reference</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> for Determining Selected ImmigrationConsequences of Selected <strong>California</strong> Offenses, <strong>and</strong> the<strong>California</strong> <strong>Notes</strong>Katherine BradyImmigrant Legal Resource CenterThe <strong>Chart</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Notes</strong>. The <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> analyzes some key adverse immigrationconsequences (deportability, inadmissibility, <strong>and</strong> aggravated felon status) that flow fromconviction of over 150 <strong>California</strong> offenses. The Advice column on the right suggestshow to avoid these consequences by working with the record or seeking an alternate plea.The <strong>California</strong> <strong>Notes</strong> are a series of articles for criminal defenders that are organized bytopic, e.g. how to plead to drug charges or theft charges, or what to do in response to animmigration hold. See Table of Contents at the end of this document. The <strong>Notes</strong> providemore detailed plea instructions, as well as basic information on applicable crim/imm law.Most <strong>Notes</strong> are followed by Appendices, which are defender aids specifically geared tothe topic of the Note. Check them out! They may include:Topic-specific charts <strong>and</strong> checklists. Some <strong>Notes</strong> provide a chart or checklist aboutthe Note’s topic, which is more detailed than the main <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong>. It maysummarize information <strong>and</strong> plea instructions from the Note in a quick-access format.For example §N.9 Domestic Violence, Child Abuse has as an Appendix a detailedchart on dealing with charges that may flow from a domestic violence incident.Legal Summaries for the Defendant. Because the great majority of noncitizens areunrepresented in removal proceedings, <strong>and</strong> because many immigration judges are notintimately familiar with crim/imm issues, we face the risk that your good work willgo to waste because no one in immigration court will recognize the defense you havecreated. For this reason, many <strong>Notes</strong> include an Appendix that sets out legalsummaries of the defenses described in the Note. We ask you to identify the relevantsummary (easy to do) <strong>and</strong> literally print the page, cut out the summary, <strong>and</strong> h<strong>and</strong> it toyour client. Tell the person to give it to his or her immigration attorney if any, or elsedirectly to the immigration judge. Further, because immigration detention centerauthorities often confiscate detainees’ documents, if your client will be detained weask you to mail or give a second copy to a friend or relative of the client. See eachAppendix for further information <strong>and</strong> instructions.Navigating the <strong>Chart</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Notes</strong>. Two tools will help you to get around this largedocument. First, on the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> you will see directions to certain <strong>Notes</strong> printedin red, e.g. “See Note: Drugs.” These are hyperlinks; click on them to go to the Note.i

How to Use the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Notes</strong>January 2013, www.ilrc.orgSecond, if you download the chart in PDF form you will see that there are booknote <strong>and</strong>table of contents functions that will take you around the document.To send comments or suggestions about the <strong>Chart</strong> or <strong>Notes</strong>, write chart@ilrc.org.Need for Individual Analysis. The <strong>Chart</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Notes</strong> can be consulted on-line or printedout <strong>and</strong> carried to courtrooms <strong>and</strong> client meetings for quick reference. However,competent defense advice requires an individual analysis of a defendant’s immigrationsituation. For example, the defense goals for representing a permanent resident aredifferent from those for an undocumented person; even within these categories, the goalswill change based on the individual’s priors <strong>and</strong>/or possible relief. See §N.1 Overview.To capture the needed information, an attorney or paralegal should complete the form at§N.16 Immigration Questionnaire for each noncitizen defendant. (For a “write-on” PDFversion of the form, go to www.ilrc.org/crimes.) See also §N.17 Relief Toolkit.Disclaimer, Additional Resources. Using this guide <strong>and</strong> other works cited in §N.18Resources will help defenders to give noncitizen defendants a greater chance to preserveor obtain lawful status in the United States – for many defendants, a goal that is evenmore important than avoiding criminal penalties. However, these are quick-referenceresources with real limits. While federal courts have specifically affirmed the analysispresented for some offenses, in other cases these materials represent only the authors’opinion as to how courts are likely to rule. In addition, this area of the law is volatile.Each month new decisions come out that may change immigration consequences. And in2013, with immigration reform on the table, it is possible that Congress will put inadditional crim/imm provisions <strong>and</strong> apply the change retroactively to past pleas.Defender offices should check accuracy of pleas <strong>and</strong> obtain up-to-date information. Tellthe defendant that while you will provide the best advice possible now, you cannotguarantee what may happen in the future. The best option is to use the <strong>Chart</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Notes</strong> inconsultation with an immigration expert, or if that is not possible with in-depth resourceworks such as Brady et al., Defending Immigrants in the Ninth Circuit (www.ilrc.org) orTooby, Criminal Defense of Immigrants (<strong>and</strong> other works, see www.nortontooby.com).See especially www.defendingimmigrants.org for defender resources, <strong>and</strong> seeinformation on other books, websites, trainings, <strong>and</strong> consultation at §N.18 Resources.Be sure that your defender office has a representative on the free Cal-DIP listserve, bywhich we circulate updates <strong>and</strong> announcements. Contact suyon@ilrc.org for information.Important Note to Immigration Attorneys. While these materials may provide a usefulshortcut to current information, it is crucial to note that they are written for criminaldefense counsel, not immigration counsel. They represent a conservative view of thelaw, meant to guide criminal defense counsel away from potentially dangerous options<strong>and</strong> toward safer ones. Thus immigration counsel should not rely on the chart in decidingii

How to Use the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Notes</strong>January 2013, www.ilrc.orgwhether to pursue defense against removal. An offense may be listed as an aggravatedfelony or other adverse category here even if there are very strong arguments (or in somecases even precedent) to the contrary that ought to prevail in immigration proceedings.Immigration attorneys should see Defending Immigrants in the Ninth Circuit(www.ilrc.org, 2013). This provides a detailed analysis of defense strategies <strong>and</strong>arguments for immigration proceedings. See also other <strong>ILRC</strong> publications there, <strong>and</strong> seeresources at www.nortontooby.com <strong>and</strong> at §N.17 Resources.Acknowledgements. Katherine Brady of the Immigrant Legal Resource Center (SanFrancisco) is the principal author of the <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Notes</strong>. Many thanks to SuYon Yi <strong>and</strong> Angie Junck of the <strong>ILRC</strong>, 2013 Update Editors, <strong>and</strong> to Ann Benson, HollyCooper, Raha Jorjani, Kara Hartzler, Dan Kesselbrenner, Chris Gauger, GracielaMartinez, Michael Mehr, Jonathan Moore, Norton Tooby, <strong>and</strong> other defenders <strong>and</strong>advisors of the <strong>California</strong> Defending Immigrants Partnership for their many significantcontributions to this research, <strong>and</strong> the staff at the Immigrant Legal Resource Center fortheir support. We are grateful to our colleagues in the national Defending ImmigrantsPartnership, <strong>and</strong> to the Gideon Project of the Open Society Foundation, the FordFoundation, <strong>and</strong> the former JEHT Foundation for funding this national project.Copyright 2013 Immigrant Legal Resource Center. Permission to reproduce is granted tocriminal <strong>and</strong> immigration defense attorneys only. If you use these materials in a training,please let us know at chart@ilrc.org.<strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Notes</strong>: Table of Contents<strong>California</strong> <strong>Quick</strong> <strong>Reference</strong> <strong>Chart</strong>-<strong>Notes</strong>:1. Overview2. Conviction3. Record of Conviction4. Sentences5. Immigration Holds <strong>and</strong> Detainers6. Aggravated Felonies7. Crimes Involving Moral Turpitude8. Drug Offenses9. Violence, Domestic Violence, Child Abuse10. Sex Crimes11. Burglary, Theft <strong>and</strong> Fraud12. Firearms Offenses13. Adam Walsh Act: Offenses that Prevent Citizens <strong>and</strong> Residents from Immigrating FamilyMembers14. [Reserved]15. Juvenile Delinquency16. Client Immigration Questionnaire17. Immigration Relief Toolkit18. Resourcesiii

Immigrant Legal Resource CenterQUICK REFERENCE CHARTFor Determining Key Immigration ConsequencesOf Selected <strong>California</strong> Offenses 1January 2013CALIF.CODESECTIONOFFENSEAGGRAVATEDFELONYCRIMESINVOLVINGMORALTURPITUDEOTHERDEPORTABLE,INADMISSIBLEGROUNDSADVICE AND COMMENTS(“CIMT”)Business& Prof C§4324Forgery ofprescription,possessionof any drugsMight be AF as:-Analogue to 21USC 843(a)(3)-Forgery, if 1 yr.Avoid 1 yrimposed on anysingle count. SeeNote: Sentence.See AdviceMight bedivisible:forgery isCIMT butposs of thedrug mightnot be.Deportable for CSconviction if theROC ID’s aspecific CS.Inadmissible <strong>and</strong>barred from relieffor CS convictionregardless ofwhether ROC ID’sspecific CS.AF: To avoid CS AF, <strong>and</strong>deportability & inadmissibility underCS ground, plead to straightforgery, false personation, PC 32,or other non-CS alternative. Toavoid AF, plead to straight possplus straight forgery.Deportable, Inadmissible CS: Seeother strategies in Note: Drugs.Business& Prof C§25658(a)Selling,giving liquorto a minorNot AF.Shd not beCIMT.No.If obtainable, great alternate toproviding drugs to a minor. KeepROC clear of mention of drugsBusiness& Prof C§25662Possession,purchase, orconsumptionof liquor by aminorNot AF. Not CIMT No, except seeAdvice reinadmissible foralcoholismMultiple convictions might beevidence of alcoholism, which is aninadmissibility grnd <strong>and</strong> a bar to"good moral character."Health &Safety C§ 11173(a)Prescriptionfor CS byfraudSee B&P C§4324CIMT, exceptmaybe (b)falsestatement, ifnot materialSee B&P C §4324 See B&P C §43241

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013H&S C§11350(a),(b)Possessionof controlledsubstancePoss (with nodrug prior) is notAF unless it’sflunitrazepam.Poss of over 5grams of crack,no longer is AF,regardless ofdate ofconviction.If D has priordrug conviction,avoid AF by notletting prior bepled or provedfor recidivism. 2Instead take thetime on anotheroffense or pleadto 11365 or11550, which cantake a recidivistsentence withoutbeing an aggfelony.See Advicecolumn foradditionaldefensestrategiesNot CIMT.Not deportable if aspecific CS is notID’d on ROC.See Note: Drugs.But stillinadmissible <strong>and</strong>barred from reliefeven with nospecified CS.See Advice re:effect of DEJ,1203.4, etc. on aFIRST simpleposs. forconviction prior to7/15/2011.If this is first CS offense, <strong>and</strong> clientcould get lawful status, doeverything possible to plead to anon-CS offense. This is highestpriority. See Note: Drugs forfurther discussion of all strategies.If you must plead to this, then:1. If a specific CS is not identifiedin the ROC (poss of a “controlledsubstance” rather than cocaine)there is no deportable CSconviction, 3 i.e. an LPR who is nototherwise deportable won’tbecome deportable. (H&S 11377might be a better option for thisstrategy). But conviction isinadmissible CS <strong>and</strong> bar to reliefas CS even with no specified CS.If D will have to apply for lawfulstatus or relief, use a differentstrategy.2. Older plea <strong>and</strong> Lujan benefit: Ifplea to a first conviction for simpleposs, or poss of paraphernalia,occurred before 7/15/2011,conviction can be eliminated forimmigration purposes bywithdrawal of plea under DEJ, Prop36, or PC 1203.4, as long as therewas no (a) probation violation or(b) prior grant of pre-plea diversion.(Those two bars may not apply to aperson who was under 21 duringthese events.) For convictionsentered on or after 7/15/2011,withdrawing plea per DEJ, Prop 36<strong>and</strong> 1203.4 will not work for immpurposes 4 (except see DEJ withsuspended fine, below). This Lujanbenefit does not work in immproceedings outside the NinthCircuit.3. DEJ with suspended fine. NinthCircuit held that where fine wasunconditionally suspended,withdrawal of plea under DEJ is nota conviction for imm purposes. 54. Consider other dispo that is nota conviction, e.g. formal or informaldeferred plea. See Note: Drugs2

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013H&S C§11351Possessionfor saleYes AF as CStrafficking; 11352is much betteroption.See Advice forother options.Yes CIMT,like any CStraffickingoffense,regardless ofwhetherspecific CS isidentified onROC.Not deportable forCS conviction orCS AF if nospecific CS is ID'don ROC. This wdbenefit an LPRwho is not alreadydeportable.Yes inadmissible<strong>and</strong> bar to reliefeven if ROC doesnot ID a specificCS. See Advicefor 11350.To avoid AF try to plead down tosimple poss (see H&S 11350), orH&S 11365, 11550; or plead up totransportation for personal use oroffer to sell (see H&S 11352). Orplead to PC 32 with less than 1 yror any other non-drug offense.If the ROC does not specify theCS, it is not a deportable AF or CSconviction, but is a bar to reliefTo avoid CS conviction, see 11350Advice.See Note: Drugs for further advice.H&S C§11351.5Possessionfor sale ofcocainebaseYes AF Yes CIMT Deportable,inadmissible forCS convictionSee Advice on H&S 11351 <strong>and</strong>Note: Drugs. 11351.5 is worsethan 11351 in that a specific CS isID’d. Far better to plead up to11352.H&S C§11352(a)-TransportCS forpersonaluse,-Sell,-Distribute,-Offer to doany of aboveDivisible as AF:-Not AF:transport forpersonal use or,in 9 th Cir only,offer to commitany 11352offense-Yes AF: Sell,distribute, butsee AdviceSale is CIMT.Transport forpersonal use,distribute,probably arenot.Yes, deportable<strong>and</strong> inadmissibleCS, except seeAdvice onunspecified CS.See Note: Drugs.Not deportable AF or CS offense ifspecific CS is not ID’d on the ROC,i.e. an LPR who is not alreadydeportable will not be.This dispo still will be AF <strong>and</strong> CSconviction as a bar to relief <strong>and</strong>inadmissible offense, however.See 11350 Advice.H&S C§11357(a)Marijuana,possessionNot AF (unless aprior possessionpled or proved.)Not CIMTDeportable for CSconviction, unlessa 1 st poss. 30 gmsor less mj or hash.See next box.Inadmissible forCS in all cases,but 212(h) waivermight be availablefor 1 st poss 30 gmor less mj or hash.If no drug priorsbargain hard fornon-drug offense,e.g. PC 32. SeeAdvice.If D is an LPR who is not alreadydeportable, a single conviction for11357(b), or for (a) where therecord indicates 30 gms or less,will not create deportability. But ifpossible plead to non-drug offense,in case D violates again.Any plea to 11357 is inadmissibleoffense (unless 11357(b) is heldnot a conviction; see below). If firstdrug conviction <strong>and</strong> ROC shows 30gms or less, some D’s can try forhighly discretionary 212(h) waiver– but this is risky.Where no drug priors, try to avoidthis plea! Plead to non-CS offenseor get a dispo that is not aconviction. See 11350, supra, <strong>and</strong>Note: Drugs.3

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013H&S C§11357(b)Marijuana,possessionof 28.5 gmsor less(Infraction)Not AF. Not CIMT An 11357(b)conviction with nodrug priorsautomatically getsthe 30 gms mjbenefits discussedin 11357(a).Further, infractionmay not be aconviction at all;see Advice.See 11350 Advice for pre-7.11.15pleas, <strong>and</strong> dispos that are not aconviction. Also, there is a strongargument that a Cal. infraction isnot a “conviction” for immpurposes. See Note: Drugs. If thisis not a conviction, 11357 will haveno immigration effect.Still, due to various risks, where nodrug priors try to avoid any CS plea<strong>and</strong> get a non-drug conviction.H&S C§11358Marijuana,CultivateYes, controlledsubstance AF.This is a badplea; see Advicefor other options.CIMT if ROCshows, or IJfindsevidence of,intent to sell.If intent is forpersonal use,not CIMT.Yes, deportable<strong>and</strong> inadmissiblefor CS conviction.With or without aconviction, warn Dshe may beinadmissible for“reason to believe”trafficking if thereis strong evidenceof intent to sell.To avoid AF: Plead down to simplepossession (see 11350, 11377); upto transportation or offer to sell(see 11352(a), 11360(a) or (b),11379(a)); or best option, a nondrugoffense, including PC 32 w/less than 1 yr imposed. If thiswould be 30 gms or less mj, tryhard to get 11357; otherwise, statesmall amount in ROC.See Note: Drugs.H&S C§11359Possessionfor salemarijuanaYes, controlledsubstance AF.This is a badplea; see Advicefor other options.Yes CIMT. See 11359 Avoid this plea. Plead down or upper 11351, 11358 instructions.See Note: Drugs.H&S C§11360Marijuana –(a) sell,transport,give away,offer to;(b) same for28.5 gms orlessDivisible as AF:-Not AF:transport forpersonal use or,in 9 th Cir only,offer to commitan 11360 offense- Not AF if ROCshows give asmall amount ofmj away for free. 6See Advice-Yes AF: Sell, ordistribute morethan a “smallamount”Yes CIMT asCS traffickingoffense,excepttransport forpersonal use<strong>and</strong> givingaway.Yes, deportable &inadmissible CS.A pre -7/15/2011plea to givingaway smallamount of mj mayqualify for Lujanbenefit if pleawithdrawn. See11350, supra, <strong>and</strong>Note: Drugs.Sale, offer to sellwill make Dinadmissible for"reason tobelieve" traffickingSee Note: DrugsBest options: try to plead to-Non-drug offense-11357 if no drug priors-Transportation for personal use(not an AF)-Give away under (b) (not an AF)-Give away specified small amount(if possible, 30 grams) under (a)(very likely not AF)- Offer to do any 11360 (not AF in9 th Cir)H&S C§11364Possessionof drugparaphernaliaNot AF.(Sale of drugparaphernaliamay be AF,however.)Not CIMTYes deportable,inadmissible asCS conviction,even if specific CSis not ID’d in theROC. But seeAdvice re use withmarijuana.If no drug priors, <strong>and</strong> ROC showsparaph. was for use with 30 gms orless of mj, conviction is notdeportable, is inadmissible,<strong>and</strong>212(h) waiver might beavailable. 7 See H&S 11357.Any poss paraph plea before7/15/2011 eligible for Lujan benefit;see 11350. See Note: Drugs.4

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013H&S C§11365Presencewhere CS isusedNot AF Not CIMT Assumedeportable,inadmissible forCS convictioneven if specific CSis not ID’d onROC. SeeAdvice.See Advice on H&S 11364 <strong>and</strong>11350, <strong>and</strong> Note: Drugs.Plea from before 7/15/11, with nodrug priors, may be eligible forLujan benefit; see 11350, supra.Plea to presence where 30 gms orless of mj used might get thosebenefits; see 11357H&S C§11366.5Maintainplace wheredrugs aresoldYes AF Yes CIMT Assumedeportable <strong>and</strong>inadmissible forCS convictioneven if ROC doesnot ID specific CSAvoid this plea. See H&S 11379,public nuisance offenses. SeeNote: DrugsH&S C§11368Forgedprescriptionto obtainnarcotic drugYes AF potential,see H&S 11173.Yes CIMTexcept mightnot be ifspecific pleato no fraud.intent.See H&S 11173 See Advice for H&S 11173.H&S C§11377Possessionof controlledsubstanceDivisible; seeH&S 11350Not CIMTDivisible; see11350See 11350 <strong>and</strong> see Note: DrugsH&S C§11378Possessionfor sale CSYes AF, but seeAdvice re unspecifiedCS,<strong>and</strong> see H&S11351Yes CIMTYes CS, but seeAdvice reunspecified CS<strong>and</strong> see H&S11351This is a bad plea; better to pleadup to 11379. Unspecified CS givessome help to LPRs who are notalready deportable. See 11351Advice <strong>and</strong> see Note: Drugs.H&S C§11379(a)Sale, give,transport,offer to, CSDivisible: seeH&S 11352 <strong>and</strong>Advice.Divisible, seeH&S 11352Divisible; see H&S11352.See 11350, 11352 Advice <strong>and</strong> seeNote: DrugsH&S C§11550Under theinfluencecontrolledsubstance(CS)Not AF, except:Felony 11550(e)'with firearm'might be chargedas COV, so avoid1 yr on any oncount, or plead tomisdemeanor.Not CIMTDeportable,inadmissible asCS; See Advicefor unspecified CSH&S 11550(e)also deportable forfirearms offense.See Note: Drugs. 11550(a)-(c) isnot AF even with a drug prior. NoLujan benefit even if pled prior to7/15/2011. 8 Shd not be deportableCS if specific CS is not ID'd inROC, 9 but gov't might oppose this.Unspecified CS will not preventoffense from being bar to relief.P.C. §31 Aid <strong>and</strong> abet Yes AF ifunderlyingoffense is.Yes CIMT ifunderlyingoffense isYes if underlyingoffense isNo immigration benefit beyondprincipal offense. However seeaccessory after the fact, PC 32.P.C. §32Accessoryafter the factYes AF if 1 yrimposed on anyone count (asobstruction ofjustice). 10Yes CIMT if Good plea: PC 32principal does not take onoffense is, no character ofCIMT if not. 11 principal offense,e.g. CS, violenceExcellent plea to avoid e.g. CS,violence, firearms conviction ifavoid 1 yr imposed on any singlecount. See Note: Drugs <strong>and</strong> Note:Sentence5

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013P.C. §69Resisting anexecutiveofficerYes AF as COVif 1 yr imposedon any onecount, unlessplea to offensivetouching. 12Not CIMT ifplead tooffensivetouchingNo.Plead specifically to de minimusviolence (“offensive touching”) inorder to avoid COV <strong>and</strong> CIMT.See Note: Violence, Child Abuse.Avoid AF by avoiding 1 yr imposed;see Note: SentenceP.C. §92 Bribery Yes AF if 1-yr onany one count.Yes CIMT. No. Avoid AF by avoiding 1 yr imposed;see Note: Sentence.P.C. §118 Perjury Yes AF if 1-yr onany one count.Yes CIMT No. Avoid AF by avoiding 1 yr imposed;see Note: Sentence.P.C.§136.1(b)(1)Nonviolentlytry topersuade awitness notto file policereport,complaintShd not be AF asobstruction ofjustice, 13 but tryhard to get lessthan 1 yr on anysingle count.Not COV, butplead to nothreat, force.Shd not beCIMT; lacksknowing,maliciousconduct 14 orspecific intentIf possibleplead to goodintent towardV or WitnessDeportable DVcrime if it is COV<strong>and</strong> ROC showsDV-type victim.Possibledeportable crimeof child abuse ifminor V.May be a good substitute plea withno imm consequences. Felony is astrike w/ high exposure; cansubstitute for more seriouscharges. While AF shd not beobstruction of justice, since there isno precedent decision try hard toavoid 1 yr on any single count. Seealso PC 32, 236, 243(e), not astrike.P.C. §140ThreatagainstwitnessYes assume AFif 1-yr sentenceimposed, asCOVYes CIMTDeportable crimeof child abuse ifROC shows minorV. Deportable DVcrime if it is COV<strong>and</strong> ROC showsDV-type victim.To avoid AF avoid 1-yr sentencefor any one count; see Note:Sentence. To avoid AF <strong>and</strong> DVdeportability ground see PC136.1(b)(1), 236, 241(a).P.C. §148ResistingarrestDivisible as COV:148(a)(1) is not,but felony 148(b)-(d) might be.To avoid AFavoid 1-yr on anysingle count.Consider PC 69148(a)(1) isnot CIMT,148(b)-(c) areat leastdivisible("reasonablyshould haveknown"police)Sections involvingremoval of firearmfrom officer mayincur deportabilityunder firearmsground. SeeNote: FirearmsAF: Plead to 148(a)(1). If plea to(b)-(d), avoid possible AF as acrime of violence by obtainingsentence less than 1 yr; see Note:"Sentence or plead to misdo (b) or(d) with the record sanitized offorce. 15P.C.§148.9False ID topeace officerNot AFNot CIMT, butsee Advice.No.CIMT. 9th Cir. held 148.9 notCIMT because no intent to getbenefit. 16 Even if BIA disagreed, afirst conviction of 6 mo CIMT hasno effect. See Note: CMT.P.C.§166(a)(1)– (4)(Note: 166(b)-(c) is abad plea)Violation ofcourt orderShd not be AF,but get sentenceof less than oneyr <strong>and</strong>/or keepany mention ofthreat or violenceout of ROC.UnclearCIMT: (1)-(3)has no intentbut court mayfind CIMT. (4)may dependon violativeconduct.Deportable if courtfinds vio is ofsection of DVprotective orderthat prohibits useor threat of force,or repeat harass.See Advice.Good alternative to 273.6 to avoidDV deport ground. Do not letrecord show even minor vio of DVstay away order. Keep recordvague, or plead to vio related tocustody, support, etc. See furtherdiscussion in Note: Violence, ChildAbuse.6

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013P.C. §182 Conspiracy Yes AF ifprincipal offenseis AF.CIMT ifprincipaloffense isCIMTConspiracy takeson character ofprincipal offense,e.g. CS, firearm.Exception mightbe DV ground.See AdviceImm counsel can argue that the DVdeport ground does not includeconspiracy to commit a misd COV,or child abuse, because neither 18USC 16(a) nor the deportationground (8 USC 1227(a)(2)(E)(i))include attempt or conspiracy.P.C.§186.22(a)GangmemberNot AFAssume willbe chargedas CIMT, butsee Advice.Not a basis fordeportability orinadmissibility butCongress mightadd it in future.Gang conviction is a basis to denydiscretionary relief, release onbond. Shd not be CIMT but noguarantees.P.C.§186.22(b)Gang benefitenhancementAssume will becharged as AF ifunderlyingconduct is AF(e.g., a COV with1 yr imposed)See above.Deportable DV ifunderlyingconduct is COV<strong>and</strong> DV-typevictim. Deportablechild abuse ifminor V.See Advice above. Try to avoidthis by instead pleading tounderlying conduct, 136.1, etc.P.C. §187Murder (firstor seconddegree)Yes AF Yes CIMT Potentialdeportable crimeof DV or crime ofchild abuseSee manslaughter.P.C.§192(a)Manslaughter,VoluntaryYes AF as COV,only if 1-yr ormore imposed onsingle count.Yes CIMTDeportable crimeof DV if committedagainst a victimprotected understate DV laws.Deportable crimeof child abuse ifROC shows Vunder age 18To avoid AF, avoid 1-yr sentenceimposed; see Note: Sentence. Toavoid CIMT see PC 192(b).P.C.§192(b),(c)(1), (2)Manslaughter,Involuntaryor vehicularNot COV althoas always, ifpossible avoid of1 yr on anysingle count.Not CIMT. 17Deportable crimeof child abuse ifROC shows Vunder age 18Not a COV because can becommitted by recklessness 18<strong>and</strong>/or non-violent conduct.P.C. §203 Mayhem Yes AF as COVif 1-yr or moresentenceimposed.To avoid an AFas a COV, avoid1-yr sentence onany single count.See Note:Sentence.Yes CIMTDeportable crimeof DV is a COVcommitted againsta V protectedunder state DVlaws. (Assumelaw may changeto let evidencefrom outside theROC show thisrelationship.) SeeAdvice for furtherinformation.Deportable crimeof child abuse ifROC shows avictim under 18.To try to avoid COV <strong>and</strong>deportable crime of DV, see PC69, 136.1(b), 236, 243(a), (d), (e),misd 243.4. Some of theseoffenses might be able to take asentence of a year or more. SeeNote: Violence, Child Abuse formore on violent crimes.To avoid deportable crime of DVwhere there is or may be a COV:don’t let ROC show the domesticrelationship. Best is to plead tospecific non-DV-type victim (e.g.,new boyfriend, neighbor, policeofficer); less secure is to keep theROC clear of a victim who wouldbe protected under state DV laws.7

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013If victim is under 18, this may blocka citizen or LPR’s ability toimmigrate family members in thefuture. See Note: Adam Walsh Act.P.C. §207 Kidnapping Yes AF as COVif 1-yr or moreimposed on anyone count.Ninth Circuitsays divisibleCIMT; it’spossible BIAwill disagree.See AdviceSee PC 203 redeportable crimeof domesticviolence or childabuseCIMT: Plea to moving the personwith good intentions is not CIMT,says Ninth Circuit. 19 Plead to thisspecifically if other plea is notavailable, but warn client the lawmight change at some point.P.C. §211Robbery bymeans offorce or fearYes AF as COVor Theft if 1-yr ormore imposed onany one countYes CIMTSee PC 203 redeportable crimeof DV or childabuseSee Advice for PC 203.P.C. §220Assault, withintent tocommit rape,mayhem,etc.Yes AF as COVif 1-yr or more onany one countSee Advice reintent to rapeYes CIMTSee PC 203 redeportable crimeof domesticviolence or childabuseSee Advice for PC 203Note that assault to commit rapemay be treated as attempted rape,which is an AF regardless ofsentence.P.C. §236,237(a)Falseimprisonment(felony)Divisible: Toavoid a COV,plead specificallyto fraud or deceit,not threat orforce. Eventhen, as alwaystry to avoid 1 yron any onecount.Yes CIMT,exceptpossibly ifcommitted bydeceit.See PC 203.In addition, a pleato fraud or deceitshd prevent aCOV <strong>and</strong>therefore a crimeof DV.See Advice for PC 203ROC showing deceit/fraud shd notbe a COV. A vague ROC willprevent a COV for deportabilitypurposes only: it will protect anLPR who is not already deportablefrom becoming deportable underthe DV <strong>and</strong> AF grounds, but willnot preserve eligibility for relief.Re CIMT: See misdo PC 236, ore.g. 243.P.C. §236,237(a)Falseimprisonment(misdo)Not an AF, butavoid 1 yrsentence <strong>and</strong>sanitize ROC ofinfo re intent touse force orthreatShd not beCIMT, 20 butsanitize ROCof info reintent toharm,defraud, etc.Not a COV (butsanitize therecord), thereforenot a domesticviolence offense.Might charge asdeportable childabuse if ROCshowed minor V.This is a good substitute plea toavoid crime of violence in DVcasesIf victim is under 18, convictionmay block a citizen or LPR’s abilityto immigrate family members, evenif no violence. See Note: AdamWalsh Act.P.C.§241(a)AssaultNot an AF asCOV because no1-year sentenceCIMTdivisible: Toavoid CIMT,plead toattemptedoffensivetouching.See Advice re243.To avoid COV <strong>and</strong>crime of DV, pleadto offenseinvolving offensivetouching. SeeAdvice re 243.Deportable crimeof child abuse ifROC proves thatV is a minor.This is a good alternate plea, butbecause there is clear case law onit in immigration context, a betterplea may be to battery orattempted battery, with an ROCthat shows de minimus touching.See 243 <strong>and</strong> Note: Violence, ChildAbuse.If V is under 18, see PC 203 reAdam Walsh Act.8

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013P.C.§243(a)Battery,SimpleNot an AFbecause no 1-year sentenceShd not beCIMT, butensure this w/specific pleato offensivetouching - orimmigrationjudge mayhold hrg onfactsTo avoid COV <strong>and</strong>crime of DV, pleadoffensivetouching. SeeAdvice re vagueROC.Deportable crimeof child abuse ifROC proves thatV is a minor.Good plea for immigration.A vague ROC will prevent a COVfor deportability purposes only: itwill protect an LPR who is notalready deportable from becomingdeportable under the DV grounds,but will not protect applicant fornon-LPR cancellation. See Note:Violence, Child Abuse.If V is under 18, see PC 203 reAdam Walsh Act.P.C.§243(b),(c)Battery on apeaceofficer,fireman etc.Can avoid AF.To surely avoidAF as COV,avoid 1 yr ormore on any onecount, <strong>and</strong>/orplead to misdo(b) with offensivetouching. SeeAdvice.243(b) notCIMT ifspecific pleato offensivetouching.See Advicefor 243(c)No.Possible that 243(c) (injury) wd be(wrongly) charged as COV, CIMTdespite offensive touching plea.See 243(d) <strong>and</strong> its endnotes.Plea to misdo might help.P.C.§243(d)Battery withseriousbodily injuryShd not be COVif specific plea tooffensivetouching – atleast if offense ismisdo. Moresecure: avoid 1yr or more onany single count.Note: Sentence.Generally, seeNote: Violence,Child AbuseShd not beCIMT if pleato offensivetouching. 21But if ROC isvague, immjudge mayhold hearingon underlyingfacts todetermineCIMT.If V has domrelationship, toavoid COV <strong>and</strong>crime of DV pleadto offensivetouching <strong>and</strong> try todesignate misdo.See PC 203.Deportable crimeof child abuse ifROC proves thatV is a minor.This may be a good substitute pleafor a more dangerous offense.A vague ROC (not ID’ing offensivetouching) may prevent offensefrom being a COV as an AF orcrime of DV for deportabilitypurposes, <strong>and</strong> so protect an LPRwho is not already deportable. Itwill not prevent the conviction fromserving as a bar to relief, however.See also PC 236, 243(a), (e). If Vis under 18, see PC 203 re AdamWalsh Act.P.C.§243(e)(1)BatteryagainstspouseTo avoid AF asCOV:-Plead tooffensivetouching, <strong>and</strong>/or-Avoid 1 yr onany single count.See Note:Sentence.Generally, seeNote: Violence,Child AbuseTo avoidCIMT, pleadto offensivetouching.With vagueROC, immjudge will lookintounderlyingfacts.To avoid COV <strong>and</strong>crime of DV pleadto offensivetouching. SeeAdvice re vagueROC.Deportable crimeof child abuse ifROC proves thatV is a minor.Excellent immigration plea, ifspecifically to offensive touching!A vague ROC may prevent offensefrom being a COV as an AF orcrime of DV for deportabilitypurposes, <strong>and</strong> so protect an LPRwho is not already deportable. Itwill not prevent the conviction fromserving as an AF or crime of DV asa bar to relief, however.If V is under 18, see PC 203 reAdam Walsh Act.9

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013P.C.§243.4SexualbatteryFelony is AF asCOV if 1-yrimposed on anyone count.Misdo is divisibleas COV; avoid 1yr <strong>and</strong>/or plead torestraint not byuse of force orthreat. 22 SeeAdvice.If ROC showspenetration,might be held AFas raperegardless ofsentenceYes CIMTSee PC 203 redeportable crimeof domesticviolence or childabuseSee Note: Sex Offenses. This isgood substitute plea to avoid AFssexual abuse of a minor or rape, ordeportable child abuse, but seebetter alternatives listed at 261.5.Misdo is not COV with plea torestraint “not by use of force orthreat.” A vague ROC may preventit from being a COV as an AF orcrime of DV for deportabilitypurposes, to prevent an LPR whois not otherwise deportable frombecoming deportable. It will notprevent the conviction from servingas an AF or crime of DV as a bar torelief. See Note: Record ofConviction. See also PC 243(d),(e), 136.1(b)(1), 236. 261.5.If V is under 18, see PC 203 reAdam Walsh ActP.C.§245(a)(1)-(4)(Jan 1,2012)Assault witha deadlyweapon(firearms orother) orwith forcelikely toproducegreat bodilyharmYes AF as COVif 1-yr or more onany one count.Yes CIMT,unlessperhaps ifROC states Dintoxicated orotherwisementallyincapacitated,with no intentto harm. 23See PC 203 redeportable crimeof domesticviolence or of childabuseSection 245(a)(2)<strong>and</strong> (3) aredeportablefirearms offenses.To avoid firearms grnd, keep ROCof conviction clear of evidence thatoffense was 245(a)(2); see also PC17500, 236, 243(d) <strong>and</strong> 136.1(b)(1)<strong>and</strong> Note: Firearms <strong>and</strong> seeNote: Violence, Child Abuse.If V is under 18, see PC 203 reAdam Walsh Act.P.C. § 246Willfullydischargefirearm atinhabitedbuilding, etcw/ recklessdisregardNever shd beCOV, but to besafe plead torecklessdisregard 24 <strong>and</strong>better, avoid 1 yror more on anysingle count. Tryto get misdo.See Advice.Yes CIMT. 25Deportable firearmoffense.See PC 203 redeportable crimeof domesticviolence or of childabuse, althoughnot clear that 246has “victims”.COV: Keep ROC clear of anymention of threat or intent to harm.To surely avoid an AF, get 364 orless on any single count. SeeNote: Sentence. Reduction tomisdo may help further, b/c morelimited definition of COV applies.P.C.§246.3(a),(b)Willfullydischargefirearm orBB devicewith grossnegligenceNot AF asCOV, 26 but seeAdvice re PC §246Shd not beCIMTbecause ofgrossnegligence,but may be sochargedDivisible asfirearm offense.See Advice.See PC 203 redeportable crimeof domesticviolence or of childabuse.To avoid firearm offense, plead to(b) (BB device). Or vague ROCwith plea to “firearm or BB device”or to 246.3 in entirety will preventoffense serving as deportationground, but will not prevent it fromserving as bar to non-LPRcancellation. See Note: Firearms.P.C. §§261, 262RapeYes AF,regardless ofsentence.Yes CIMTSee PC 203 redeportable DV orchild abuse crime.See PC 243(d), 243.4, 236,136.1(b)(1). See Note: Violence<strong>and</strong> Note: Sex Crimes.P.C.Sex with aminor underNot AF as sexualabuse of a minorAssume it is aCIMT, unlessIt will be chargedas deportableSee Note (<strong>and</strong> <strong>Chart</strong>): Sex Crimes.10

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013§261.5(c)age 18 <strong>and</strong>three yearsyoungerthanDefendant(SAM) in the 9 thCircuit, whether§261.5(c) or (d),if ROC showsminor was atleast age 15 27(or possibly age14, but avoid thisif at all possible).More secure is aplea to an ageneutraloffensesuch as 236,243, 314, 647, orfor 14 or 15-yroldspecific nonexplicitconductin 288(c), or647.6. SeeAdvice.Not COV if D isat least 14, butstill try to avoid 1yr, in case D istransferred to aCircuit where thatis a COV. 28ROC shows crime of childthat D abuse. If minorreasonably was an older teen,believed the imm counsel haveminor was at arguments againstleast age 16 this, but no(or perhaps guarantee of18). 29 winning.To avoid SAM under 9 th Cir law, 30 aplea to minor age 16-17 is betterthan age 15. If plea is to age 15,try not to let ROC show D is 4years older (9 th Cir has held this isnot SAM, but still good to avoid), orelse see 288a(b)(1).Note that if U.S. Supreme Courtdecides as expected in Descampsv. U.S. (expected before June2013), no conviction under261.5(c) or (d) shd held be SAM inNinth Circuit states, because aprior conviction will be judged by itsleast adjudicated elements. If thiswd greatly help the D, considerdelaying plea hrg for some time, toget closer to Court’s decision.If D will be removed <strong>and</strong> is likely toreturn illegally, <strong>and</strong> minor is age15, do the following to preventcreating a prior that would be asevere sentence enhancement:get any 261.5 misdo, or 261.5(c)where the ROC does not specifyage of minor. If that is not possible,see felony 288a(b)(1) or (2). 31P.C.§261.5(d)Sex whereminor underage 16, D atleast age 21See §261.5(c) See §261.5(c) See §261.5(c). See 261.5(c). See Note (<strong>and</strong><strong>Chart</strong>): Sex Crimes.P.C. §266Pimping <strong>and</strong>p<strong>and</strong>eringTo prevent AF,see AdviceYes CIMTDeportable childabuse if prostituteunder age 18.AF: To prevent AF, plead toactivity with persons age 18 orover, <strong>and</strong> to offering lewd conduct,not intercourse, for a fee. 32P.C. §270Failure toprovide forchildNot AF.Not CIMT, atleast if ROCstates childnot destituteor harmed.Appears not crimeof child abuse, atleast if child notdestitute, harmed.See AdviceThis conduct does not appear tocome within child abuse/neglectground as defined by BIA. Try toinclude in ROC that child was notat risk of being harmed/deprived.P.C. §272Contributingto thedelinquencyof a minorNot AF as SAM,but keep ROCfree of lewd actDivisible: maybe CIMT iflewdness, tryto plead tospecific,innocuousfactsMight be chargedunder DV groundfor child abuse,especially if lewdact.Deportable child abuse. Currentlyimm authorities are broadlycharging child abuse. However,272 requires only a possible, mildharm. See Advice 273a(b). Try tospecify extremely low risk of harm,or seek age-neutral plea.11

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013P.C.§273a(a),(b)Child injury,endangermentTo avoid COV,plead specificallyto negligentlyplacing childwhere may beendangered, asopposed toinflicting pain.To surely avoidAF, avoid 1 yr ormore on anysingle count. SeeNote: Sentence.DivisibleCIMT:Assume (a) isCIMT. For(b), pleadspecifically tonegligentlyrisking child'shealth, asopposed toinflictingpain 33§ 273a(a) isdeportable crimeof child abuse.Conservativelyassume (b) is aswell, altho pleathat specifiesexposure to mildrisk may well notbe. 34 See Advice.See Note: Violence, Child AbuseTo avoid CIMT <strong>and</strong>/or deportablechild abuse, plead to age-neutraloffense, e.g. 243(a) where ROCdoes not specify minor age. If thisarose from traffic situation (lack ofseatbelts, child unattended etc.),seek traffic offense <strong>and</strong> takecounseling <strong>and</strong> other requirementsas probation condition.COV: This plea will likely make anLPR deportable for child abuse.To keep the LPR eligible for relief,avoid AF by specific plea to notviolent conduct, <strong>and</strong>/or avoid 1 yror more on any single count.P.C.§273dChild,CorporalPunishmentYes AF as COVif 1-yr sentenceimposed. SeeNote: Sentence.Yes CIMTDeportable underchild abuse. SeeAdviceTo avoid child abuse, get ageneutralplea with no minor age inthe ROC: 243, 245, 136.1(b)(1),etc. (with less than 1 yr as needed)P.C.§273.5SpousalInjuryYes, AF as aCOV if 1-yr ormore sentenceimposed.Yes CIMT,unless pleadto minor injury+ attenuatedrelationshiplike pastcohabitant. 35Deportable crimeof DV.If ROC shows V isa minor,deportable crimeof child abuse.See Note: Violence, Child Abuse.To avoid COV, DV <strong>and</strong> CIMT seePC 243(d), (e), 236, 136.1(b)(1);can accept batterer's programprobation conditions on these.P.C.§273.6Violation ofprotectiveorderNot AF, but get364 days <strong>and</strong>/orkeep violence outof ROC.CIMT unclear;might dependupon thenature of theviolativeconductDeportable as aviolation of a DVprotection order,at least if pursuantto Cal Fam C6320, 6389. 36 SeeAdviceSee Note: Violence, Child Abuse.DV: Automatic deportable DV,unless pursuant to statute otherthan FC 6320, 6389. Instead,plead to new offense that is not DV(e.g., 243(e), 653m) or see 166.P.C. §281 Bigamy Not AF Yes CIMT No Case law added element of guiltyknowledge so it is a CIMTP.C. §§286(b),288a(b),289(h), (i)Sexualconduct witha minorSee 261.5(c), (d) See 261.5 See 261.5 See 261.5. If D will be removed,felony 288a(b) with 15-yr-old isbetter than the same on 261.5.P.C.§288(a)Lewd actwith minorunder 14Yes AF as sexualabuse of a minorregardless ofsentenceimposedYes CIMTunless IJfinds Dreasonablybelieved Vwas age 16 orperhaps 18;see 261.5(c)Deportable forcrime of childabuse. To avoid,plead to ageneutraloffensewhere ROC doesnot show minor V.See Note: Sex Offenses. Very badplea. See age-neutral offensessuch as 32, 136.1(b), 236, 243,243.4, 245, 314, 647, or else see288(c), 647.6, or even 261.5, 288a-- with no reference to specific ageunder 15.12

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013P.C.§288(c)Lewd actwith minorage 14-15<strong>and</strong> 10 yrsyoungerthan DDivisible as AFas sexual abuseof a minor(SAM). 37 Pleadto innocuousbehavior. While15 is better than14, 14 shd besafe. See Advice.Yes CIMT if IJfinds D knewor had reasonto know Vwas underage 16; see261.5(c)Will be charged asdeportable crimeof child abuse, butcreate best recordpossible. Thisarguably does notfit the definitionbecause caninvolve no harm orrisk of harm <strong>and</strong>no explicitbehavior.SAM: Good alternative to moreexplicit sexual charge. 288includes "innocuous" touching,"innocently <strong>and</strong> warmly received";child need not be aware of lewdintent. 38 But warn D this couldbecome AF as SAM in future, or ifD is taken outside 9th Cir. Tryinstead for age-neutral offense, PC32, 236, 243, 243.4, 136.1(b), 314,647, etc. where ROC sanitized ofV’s age. See Note: Sex OffensesP.C. §290Failure toregister as asex offenderNot AFMay becharged asCIMT, but thisappearsincorrect <strong>and</strong>might change.See AdviceCan be chargedwith a new federaloffense, 18 USC2250, for stateconviction forfailing to register;2250 conviction isbasis for removal.Avoid if possible. Deportable ifconvicted in federal court of 18USC §2250 for failure to register asa sex offender under state law. 39Re CIMT: there is a conflictbetween the Ninth Circuit, otherCircuits (not CIMT) <strong>and</strong> BIA (CIMT)published opinions 40 . Ninth Circuitmight refuse to defer.P.C.§311.11(a)ChildPornographyYes, AF 41 Yes CIMT. 42 No. Avoid this plea if at all possible.Plea to generic porn is not an AF. 43P.C.§313.1Distributingobscenematerials tominorsNot AF, unlessconceivably ifROC showsyoung child.Perhapsdivisible asCIMT, seeAdvice.Might be chargedas deportablecrime of childabuse, if ROCshows given toyoung child?To avoid CIMT, plead to failure toexercise reasonable care toascertain the minor’s true age. Ifminor is older, put age in the ROC.Mild conduct such as giving amagazine to an older teen shd notbe CMT, but no guarantees.P.C.§314(1)IndecentexposureNot AF even ifminor’s age inROC, 44 but asalways keep ageout if possible.Yes CIMT,with possibleexception ofplea to eroticact for willingaudience. 45Keep anyreference to minorV out of ROC toavoid charge ofdeportable crimeof child abuseGood alternative to sexual abuseof a minor AF charges such as288(a). To avoid CIMT, see disturbpeace, trespass, loiterP.C. §315Keeping orliving in aplace ofprostitutionor lewdnessDivisible as theAF of owning orcontrolling aprostitutionbusiness. 46Specific plea toresiding in placeof prostitution (orlewdness), orkeeping a placeof lewdness, shdnot be AF. SeeAdvice.AssumeCIMT, exceptspecific pleato just living<strong>and</strong> payingrent in a placeof prostitutionor lewdnessought not tobe. 47Deportable aschild abuse ifminor involved.Importingnoncitizens forprostitution orimmoral purposeis deportableconviction.See Advice forprostitutioninadmissibilityProstitution is defined as offeringsexual intercourse for a fee, notlewd act for a fee. Thus a specificplea to lewd act will prevent theprostitution AF <strong>and</strong> inadmissibilityground. 48 Lewd act is sufficient forCIMT, deportable child abuse, ordeportable for importing noncitizenprostitutes, however.Inadmissible for prostitution ifengaged in or received proceedsfrom prostitution; no convictionrequired.P.C.§368(b),(c)Elder abuse:Injure,EndangerTo avoid COV,See Advice.To surely avoidAF, avoid 1 yr onCIMTdivisible;specific pleato negligentacts shd notNoTo avoid AF as COV: Pleadspecifically to negligent, reckless,or non-violent endangerment orinfliction of injury. (Or, get lessthan 1 year on any single count)13

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013any single count.be CIMT.P.C. §368(d)Elder abuse:Theft, Fraud,ForgeryYes AF danger:see Advice.Generally seeNote: Burglary,Theft, FraudYes CIMT No To avoid AF: Plead to fraud whereloss to victim does not exceed$10,000; can take a sentence ofover a year. Plead to theft, forgerywhere loss to victim exceeds$10,000; need to avoid 1 yr on anyone count. See Note.P.C. §403Disturbanceof publicassemblyNot AF.Not CIMT;see AdviceNo.This does not have CIMTelements, but keep ROC free ofvery bad conduct or violence.P.C. §415Disturbingthe peaceNot AF.Probably notCIMTNo.P.C. §416Failure todisperseNot AF Not CIMT No.P.C.§417(a)(1)(2)Br<strong>and</strong>ishingdeadlyweapon(firearm <strong>and</strong>other)Not COV, but tobe safe get 364or less <strong>and</strong> pleadto “rude.”See Advice, <strong>and</strong>see Note:FirearmsNot CIMT. 49Deportablefirearms offense if417(a)(2).See Advice if V isa minor or hasdomesticrelationshipTo make sure not COV, <strong>and</strong> thusnot DV offense if DV-type victim,plead to rude not threateningconductTo make sure not deportable crimeof child abuse, keep record free ofminor victim.P.C. §422Criminalthreats(formerlyterroristthreats)Yes AF as COVif 1-yr sentenceimposed. 50 SeeNote: Sentence.See Advice.Yes CIMT 51Deportable crimeof child abuse ifROC shows minorvictim.Deportable DVcrime if DV-typevictim.If conviction is formultiple threats,deportable forstalking.To try to avoid COV <strong>and</strong> thereforeavoid a deportable crime of DV,see PC 69, 136.1(b), 236, 243(a),(d), (e), misd 243.4. Some of theseoffenses might take a sentence ofa year or more. See Note:Violence, Child Abuse for more onviolent crimes.If victim is under 18, this may blocka citizen or LPR’s ability toimmigrate family members in thefuture. See Note: Adam Walsh Act.P.C. §§451, 452Arson,Burning:Malicious orRecklessAssume both 451<strong>and</strong> 452 are AF’sregardless ofsentence. 52 SeeAdvice.Yes, assumeCIMTNo.To maybe avoid AF, plead to PC453 with less than 1 yr on any onecount. If that is not possible, immcounsel at least will investigategrounds to argue that PC 452 w/364 days is not AF.P.C. §453Possessflammablematerial withintent toburnSpecific plea to“flammablematerial,” withless than 1 yr orrecklessness,may avoid AF;see Advice.Yes CIMT No AF: Good alternative to 451, 452,if possession or disposal offlammable materials is notanalogous to relevant federaloffenses. 53 To avoid AF as COV,avoid 1 yr on any one count <strong>and</strong>/orplead to reckless. See Note:Sentence.14

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013P.C.§460(a)Burglary,ResidentialYes, as COV if 1yr imposed forany single count.See Advice <strong>and</strong>Note: Burglaryfor furtherinstructions.Yes CIMT –unless pleadspecifically topermissiveentry & intentto commit anon-CIMT.No (unlessconceivablycharged as a DVoffense if it is thehome of personprotected understate DV laws)To avoid AF: (1) Avoid 1 yr or moreon any one count (see Note:Sentence) <strong>and</strong> (2) Do not let ROCshow admission of entry with intentto commit an offense that is an AFregardless of sentence (e.g., drugtrafficking) <strong>and</strong> a substantial steptoward commission, which couldbe an AF as “attempted” drugtrafficking. 54 See Note.P.C.§460(b)Burglary,nonresidentialAvoid AF byavoidingsentence of 1 yror more on anyone count <strong>and</strong>/orby carefullycrafting plea.See Advice <strong>and</strong>see Note:Burglary.Yes CIMT –unless pleadto intent tocommit aspecificoffense that isnot a CIMT.No.To avoid AF: if you have 1 yrimposed on a single burglarycount, avoid pleading to any of thefollowing: unlicensed entry intobuilding or structure; entry byviolent force; or intent to commitlarceny (or other agg felony),where ROC shows substantialstep. 55 See also Advice for 460(a)regarding intent to commit anoffense that is an AF regardless ofsentence.P.C. §466Poss burglartools, intentto enterNot AF (lacks theelements, <strong>and</strong> 6mo max misd).May not beCMT. B&Ealone is not.See AdviceNo.Shd avoid CIMT with specific pleato “Poss of a ____ with intent tobreak <strong>and</strong> enter ___ , but withoutintent to commit further crime.”P.C. §470 Forgery Yes AF asforgery orcounterfeiting. 56To avoid AF,avoid 1 yr ormore on any onecount. See Note:Sentence. Or,see § 529(3).See Advice if thisalso is fraud withloss to victim/s ofover $10,000Yes CIMT.See 529(3) totry to avoidCIMT.No.AF: A fraud/deceit offense is an AFif loss to victim/s exceeds $10k. 57Plead to one count with loss under$10k, in which case can pay morethan $10k restitution; if possibleadd Harvey waiver. See Note:Burglary, Theft, Fraud.If must plead to both fraud <strong>and</strong>forgery, counterfeit, or theft, thenmake sure no fraud plea exceeds$10k loss, <strong>and</strong> no forgery etc. pleatakes 1 yr or more on a singlecount.P.C.§476(a)Bad checkwith intent todefraudYes AF if loss tothe victim/s was$10,000 or more.Yes AF if forgery,counterfeit with 1yr imposed.Yes CIMT.See 529(3) totry to avoidCIMT.NoSee Note: Burglary, Theft, FraudTo avoid an AF, see Advice for§470P.C. §§484 etseq., 487Theft (pettyor gr<strong>and</strong>)To avoid AF astheft: avoid 1 yron any one countof property theft(taking withoutconsent), or theftof labor, even if 1yr or more, orembezzlement orfraud (taking withYes CIMT, allof § 484.See AdviceNoTo avoid CIMT, <strong>and</strong> if 1-yrsentence is not imposed on anysingle count, see PC 496(a) or VC10851, with intent to temporarilydeprive.If plea is to §484 <strong>and</strong> this is a firstCIMT conviction: Can qualify forpetty offense exception toinadmissibility grnd, with 1 yrmaximum possible sentence15

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013deceit) with lessthan $10,000loss to victim/s. 58See Note:Burglary, Theft,Fraud(wobbler misdo qualifies) <strong>and</strong> 6 moor less imposed. To avoid beingdeportable for one CIMTcommitted within 5 yrs ofadmission, get a 6 month possiblemax: either petty theft or attemptedmisd gr<strong>and</strong> theft; this also avoid abar to non-LPR cancellation. SeeNote: CIMT.P.C.§490.1Petty theft(infraction)Not AF.Yes CIMT,but infractionmight not bea conviction.See Note:Definition ofConviction.No.CIMT: Even if a conviction, if this isfirst CIMT then D will not beinadmissible or deportable forCIMT because of 6 month max.See Note: CIMT. Or t o avoid aCIMT, see PC 496, VC 10851P.C. §§496, 496dReceivingstolenproperty, orreceivingstolenvehicleYes AF if 1-yr onany single count.If must take 1 yrconsider a fraudoffense. SeeNote: Burglary,TheftTo avoidCIMT: pleadspecifically tointent totemporarilydeprive. SeeAdvice.No.CIMT: Ninth Cir held 496(a)includes intent to deprive ownertemporarily, which is not a CIMT. 59See Note: CIMTTo avoid 1 yr sentence on anysingle count <strong>and</strong> thus avoid AF,see Note: Sentence.P.C. §§499, 499bJoyriding;Joyridingwith PriorsYes AF as theft if1 yr-sentenceimposed on anysingle count. SeeNote: Sentence.Not CIMT(becausetemporaryintent)No.Note that the AF “theft” includesintent to temporarily deprive, whileCIMT does not. If 1 yr will beimposed, see suggestions to avoidAF at Note: Burglary, Theft.P.C.§528.5Impersonateby electronicmeans, toharm,intimidate,defraudAF as fraud ifloss exceeds$10k. See Note:Burglary, TheftFraud.Possible COV ifROC showsviolent threat; ifso, avoid 1 yr onany one count.Divisible asCIMT. “Harm”may not beCIMT <strong>and</strong>need not beby unlawfulact (see530.5). SeeAdviceIf a COV could bea DV offense if Vis protected understate laws. IfROC shows minorV, perhapscharged childabuse.Substitute for ID theft or other, insympathetic case?CIMT: Plead to specific mild harm,e.g. can be committed by, e.g.,impersonating a blogger, orsending an email purporting to befrom another, to theirembarrassment. 60 Does notrequire the person to haveobtained a password or otherprivate information.P.C.§529(3)FalsepersonationAF depends.-If conductinvolved forgery,counterfeit, avoid1 yr for anysingle count.-If it involveddeceit with lossto victim/sexceeding$10,000, seeAdvice.-Otherwise, notan agg felony.Divisible asCIMT.See Advice.No.CIMT. A plea to impersonationspecifically without intent to gain abenefit or cause liability shdprevent a CIMT. 61 If that is notpossible, in the future it might bethat no conviction under 529(3) willcause deportability for CIMT, althoit cd cause inadmissibility or bar torelief. 62 See Note: CIMT.If $10k loss, see Advice for § 470<strong>and</strong> see Note: Burglary, Fraud.Forgery or counterfeit with 1 yrimposed on a single count is anagg felony. Plead to specificconduct that is not forgery16

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013P.C.§532a(1)FalsefinancialstatementsYes AF if fraud ofmore than $10k;Yes AF if forgerywith 1 yr on anyone countYes CIMTbecausefraudulentintent.See 529(3)No. If $10k loss, see Advice for § 470<strong>and</strong> see Note: Burglary, Fraud.Forgery, counterfeit with 1 yr is anAF. Plead to specific conduct thatis not forgery or get less than 1 yrP.C.§550(a)InsurancefraudSee §532a(1) See §532a(1) No. See §532a(1)P.C. §591Tamperingw/ phonelines,maliciousNot AF: NotCOV. (But saferalways to get 364or less on anyone count <strong>and</strong>keep ROC clearof any violentthreat)Shd not beCIMT. Pleadto specificmild offense.See AdviceNot deportable DVoffense, but keepROC clear of anyviolence, threats.Keep ROC clearof V under age 18.Good DV alternative because notCOV, not stalkingCIMT. “Obstruct” includes e.g.leaving phone off the hook toprevent incoming calls. 63 Maliciousincludes intent to annoy. Specificplea to mild behavior with intent toannoy shd avoid CIMT.P.C.§591.5Tamper w/cell phone topreventcontact w/lawenforcementNot AF: Not COV<strong>and</strong> has 6 monthmax. sentenceAssumeCIMT,althoughunclear. SeeAdvice.Not deportable DVoffense b/c notCOV, but to besafe keep ROCclear of violenceor threats.Keep ROC clearof minor age of V.Good DV alternative because notCOV, not stalkingCIMT: If this is first CIMT it willhave no immigration effectbecause 6 month max. If this isnot a first CIMT, consider carefulplea to 591; has a higher potentialsentence but may not be CIMTP.C. §594 V<strong>and</strong>alism Possible AF asCOV if violenceemployed <strong>and</strong> 1yr imposed onany single count.See Note:SentenceDivisible asCIMT? NinthCircuit heldnot CIMT, atleast wheredamage notcostly. 64See Advice.No. Even if aCOV, deportableDV groundrequires violencetoward person notproperty.Re DV. Good DV alternativebecause not COV to person.Re CIMT. Plead specifically tocausing less than $400 damage,even if greater amount inrestitution, or paid before plea, orseparate civil agreement. Plead tointent to annoy.P.C. §602Trespass(6 mo)Not AF (for onething, 6 mo maxsentence)Shd not beCIMTSee Advice.See PC 594.(l)(4) is deportablefirearm offense.See PC 602.5, below. Somemalicious destruction of propoffenses might be CIMT; see casesin Advice to PC 594.P.C.§602.5Trespass(residence)(1 yr)Not AF, but avoidconceivableburglary chargeby avoiding 1 yr.Not CIMT, butsee AdviceNo.CIMT. Avoid admitting intent tocommit other crime upon entry; ifpossible plead to, e.g., intent toshelter, sleep; or incapacitated.P.C.§646.9StalkingAvoid AF asCOV by avoiding1 yr on any onecount. If can’tavoid 1 yr, seeAdvice.AssumeCIMT, <strong>and</strong>look to 236,240, 243,136.1(b)(1)Always deportableunder DV groundas "stalking." Seepleas suggestedin CIMT column.To avoid a COV, plead toharassment from long-distance orjail, or to recklessness. See casecited in endnote. But outside 9 thCir, § 646.9 is always COV. 6517

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013P.C.§647(a)Disorderly:lewd ordissoluteconduct inpublicNot AF even ifROC showsminor involved 66(but still, don't letROC show this)Yes heldCIMT, althoimm counselwill argueagainst this.See Advice.To avoid possibledeportable childabuse charge,don’t let ROCshow minorinvolved.AF: Good alternative to sexualconduct near/with minorCIMT Older BIA decisions findingCIMT were based on anti-gay bias<strong>and</strong> shd be discredited, 67 so at riskfor CIMT. See 647(c), (e), (h).P.C.§647(b)Disorderly:ProstitutionNot AF.Yes CIMT,whetherprostitute orcustomer,lewd act orintercourse. 68Prostitutioninadmissibilitygrnd requires offerof intercourse fora fee; plead tooffer of specificlewd act for a fee.Does not includejohns. See Advice.Inadmissibility for engaging in prostcan be proved by conduct <strong>and</strong>does not require a conviction, butthe specific plea describedprovides some protection. Johnincluded in CIMT offense, but notprostitution inadmissibility ground.See 647(c), (e) <strong>and</strong> (h). See Note:Sex OffensesP.C.§647(c),(e), (h)Disorderly:Begging,loiteringNot AF. Not CIMT. No. Good alternate plea. Do notinclude extraneous admissions re,e.g., minors, prostitution, furtherintended crime, firearms, etc.P.C.§647(f)Disorderly:Under theinfluence ofdrug, alcoholNot AF. Not CIMT. Possible CSoffense; seeAdvicePlead specifically to alcohol toavoid possible drug charge.P.C.§647(i)Disorderly:"PeepingTom"Not AF but keepROC clear ofminor targetCIMT danger,see AdviceMight be chargedas child abuse if Vis minor; keep ageout of ROCCIMT: Offense requires no intent tocommit a crime; it is completed bypeeking. 69 However, imm judgemight make broad inquiry to see ifany lewd intent for CIMT purposes.Specific plea to “peeking withoutlewd intent”?P.C.§647.6(a)Annoy,molest childDivisible as SAM(sexual abuse ofa minor). Pleadto specific lessonerous conduct;see examples atthis endnote. 70See Advice, <strong>and</strong>See Note: SexOffensesDivisible asCIMT. SeeAdvice <strong>and</strong>prior endnote.Assume chargedas deportablecrime of childabuse, altho someconduct shd notbe. ID in the ROCnon-sexual, nonharmfulconduct,or keep ROCvague.See AdviceCIMT. If ROC states D’sreasonable belief that minor wasage 18 or perhaps 16, not CIMT.Perhaps same result if ROCspecifically ID's non-egregiousbehavior <strong>and</strong> intent regardless ofbelief re age.AF <strong>and</strong> deportable Child Abuse:The sure way to avoid SAM <strong>and</strong>child abuse is a plea to age-neutraloffense like 243, 236, 314, 647 etc.with ROC clear of minor victim. Agood Supreme Court decision inDescamps (due by June 2013) 71wd mean that no conviction under647.6(a) would be SAM in 9 th Cir.If you cannot create a goodspecific plea, consider delayingplea hearing; consult with imm atty.P.C.§653f(a),(c)Solicitationto commitvariety ofoffensesDivisible: 653f(a)<strong>and</strong> (c) are AF asCOV's if oneyearsentence isimposed;Solicitingviolence is aCIMT.653f(a) <strong>and</strong> (c) areCOV's, <strong>and</strong>therefore DV ifDV-type victim.653f(a) <strong>and</strong> (c) are COV. 7218

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013P.C.§653f(d)Solicitationto commitdrug offenseSolicitation topossess a drug isnot AF as drugtrafficking. (Inthe Ninth Circuitonly, evensolicitation to sellis not an AF.)Not CIMT if Dis buyer forpersonal use,yes CIMT if Dis otherwiseparticipatingin distributionor sale.Ninth Cir. stated indicta this is not adeportable CSoffense because itis genericsolicitation.Statute. 73 SeeAdvice.Deportable/Inadmissible. This maybe a better plea than possession,in that there is dicta <strong>and</strong> a strongargument that this is not adeportable/inadmissible CSoffense in the Ninth Cir.P.C.§653k(repealed)Possessionof illegalknifeNot AF Not CIMT Not deportableoffenseGood pleaP.C.§653m(a),(b)Electroniccontact with(a) obscenityor threats ofinjury withintent toannoy; or (b)repeatedannoying orharassingcalls.Not AF. (While(a) using threatsof injury might becharged as COV,it has 6 monthmax sentence.)To avoidCIMT plead to(a) anobscene callwith intent toannoy, or (b)two calls withintent toannoyDeportable childabuse: To avoidpossible charge,do not let ROCshow victim was aminor.See Advice forhow to avoid otherDV deportationgrounds.For more info ingeneral, seeNote: Violence,Child Abuse.Good plea in a DV or other context.Deportable DV crime: If DV-typevictim, plead under (a) to obscenecall with intent to annoy, or (b) twophone calls intent to annoy. Stateon the record that calls did notinvolve any threat of injury. Or ifpossible plead to other victim, e.g.repeat calls to the new boyfriend,(no threats, intent to annoy).Deportable violation of DVprotective order. Do not admit toviolating a stay-away order in thisor any other manner; or see § 166.Try to plead to new 653m offenserather than vio of an order.Deportable stalking: Stalkingrequires a threat, altho does notrequire a DV relationship. Plead toconduct described above.See also PC 591P.C. §666Petty theftwith a priorAF as theftunless (a) avoid1 yr on any onecount <strong>and</strong>/or (b)ROC shows theftof laborYes CIMT.With the prior,this makes adangeroustwo CIMTs.See Note:CIMT.No.See Note: Burglary, Theft, Fraud.CIMT: Receipt stolen property496(a) is divisible for CIMT (but isan AF w/ 1 yr imposed); plead totemporary intent. This cd preventsecond CIMT.P.C.§1320(a)Failure toappear formisdemeanorNot AF asobstructionbecause thatrequires 1 yrsentenceUnclear;Might becharged asCIMT. 74 No AF:19

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013P.C. §§1320(b),1320.5Failure toappear for afelonyDangerous plea;seek a differentoffense. Can beAF regardless ofsentenceimposed; seeAdviceAlways is AF if a1-yr is imposed,as obstruction ofjustice. 75 See 1320(a) No. 1320(b), 1320.5 are AF asobstruction of justice, if a sentenceof 1 yr or more is imposed. Seeendnote for 1320(a), supra.Even without a 1 yr sentence, theymay be the AF "Failure to Appear."FTA to answer a felony charge witha potential 2-year sentence, or toserve a sentence if the offense ispunishable by 5 years or more, isan AF regardless of the sentenceimposed for the FTA itself. 76FormerP.C.§12020(pre-Jan.1, 2012)Possession,manufacture,sale ofprohibitedweapons;carryingconcealeddaggerTrafficking infirearms orexplosives is AFregardless ofsentence;; seeAdviceWeaponpossession isnot CIMT. 77Sale shd notbe CIMT butnot secure.Offenses relatingto firearms causedeportability underthat grnd unlessROC specifiesantique firearm(see PC 25400).Plead to otherweapons, e.g.brass knucklesdaggerWith careful ROC, this was goodalternate plea to avoid deportableor agg felony conviction relating tofirearms <strong>and</strong> destructive devices(explosives).P.C.§12021(a),(b)(Repealed1/1/12)Possessionof firearm bydrug addictor felonDivisible asFirearms AF:Felon in poss is,but poss bymisdemeanant isnot, <strong>and</strong> felonwho owns ammoor firearm shdnot be AF.Probably notCIMT.Deportable underthe firearmsground, except foroffenses relatingto ammo, e.g.felon owningammoSee discussion at PC §§ 29800,30305.Can be a firearms AF as analogueto federal “felon in possession”offense. There is authority thatowning firearm is different frompossessing one such that owningis no AF. Felon who owns ammois even better.P.C.§12022(a) (1),(b)(1)Use firearmor otherweaponduringattempt orcommissionof a felonyYes AF as COV(unless there issome unusualfact scenario thatcould escapebeing a COV).See Advice.Likely to beheld CIMTunlessunderlyingfelony is not.Deportable underthe firearmsground if (a), butnot if (b) <strong>and</strong>record does notshow firearm.Exception forantique firearms(see PC 25400).Avoid AF: This enhancementcreates a single COV count w/ 1 yr.Instead try to plead to poss or useof a firearm or weapon plus theother felony, in multiple counts,<strong>and</strong> spread time among counts.See Note: Sentence.P.C.§§12025(a)112031(a)1(Repealed1/1/12)CarryingfirearmNot AF. Not CIMT. Deportable underthe firearmsground unlessROC specifiesantique (see PC25400).To avoid deportable for firearms,see PC 12020 <strong>and</strong> Note: Firearms.20

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013P.C.§17500Possessionof weaponwith intent toassaultNot AF (6 monthmax sentence,plus arguably notCOV)For furtherdiscussion of thisoffense, seeNote: FirearmsTo probablyavoid CIMT,plead to intentto commitoffensivetouching, <strong>and</strong>to possessionbut not use orthreaten witha dangerousweapon.If that is notpossible,plead tostatutorylanguage <strong>and</strong>see Advice reDescampsTo avoiddeportable crimeof child abuse:keep minor age ofvictim out of ROC.See Advice reother deportationgrounds.Good alternative plea; may haveno consequences:Deportable firearms: Plead to anon-firearms weapon or antiquefirearm, or if deportability is all thatis at stake (as opposed to eligibilityfor non-LPR cancellation), an ROCvague as to weapon will suffice. 78Deportable crime of DV: Arguablynot a COV with a plea to offensivetouching, but to avoid DV plead tospecific non-DV-type victim or keepdomestic relationship out of ROC;see PC 203.Effect of Descamps: In spring2013 S.Ct. may hold that a priorconviction can be evaluated onlyby its least adjudicated elements.In that case §17500 would not be adeportable firearms offense or aCOV regardless of the plea, althoabsent the “offensive touching” itmight be a CIMT.P.C. §§21310,22210,21710,etc.Possessionof weapon(not firearm),e.g. dagger,blackjack.Not COV 79 or AFBut just to besafe, sanitize theROC of anythreat, violence.Not CIMT.No. (Notdeportablefirearms offense)Good alternate plea to firearmscharge, if D had an additionalweapon or could plead to one.P.C. §§25400(a),26350Possessionof concealedor unloadedfirearmNot an AF, but asalways try toavoid 1 yr on anyone count.Not CIMT.Yes deportablefirearm offense –unless the ROCspecifies anantique firearm, inwhich case it isnot a “firearm” forany immigrationpurpose.See Advice.Antique firearm exception: Antiquefirearms are excluded from thefederal definition of firearms usedin imm law. 18 USC 921(a)(3). Anantique is defined as a firearmmanufactured before 1899, orcertain replicas of such antiques.18USC 921(a)(16). Immigrant mustprove the firearm was an antique,so need specific plea to this.P.C.§27500Sell, supply,deliver, givepossessionof firearm toprohibitedpersonSale is AF (firearmstrafficking),but give shouldnot be AF astrafficking.Unclear onCIMT. SeeAdviceYes, deportablefirearm offense,unless ROCspecifies antique(see PC 25400).CIMT: Don’t know. Might not beCIMT if mere “reason to know”person was in prohibited class, or ifgive rather than sell - or not.P.C.§29800Possession,ownership offirearm byfelon, drugaddict, etc.AF as a federalanalogue unlesscareful pleading.To avoid AF,plead topossession bymisdemeanant.(See also 29805,29815(a), 29825)Or plead to felonor drug addictwho owns ratherShd not beCIMT but noguarantee.Owning mightbe better thanpossessingYes deportablefirearms offenseunless ROCspecifies antique(see PC 25400).To avoid firearmsdeportationground, plead tooffense involvingammunition suchas PC 30305, oroffense involving aAvoid AF: Felon in possession of afirearm is an AF. 80 Very strongsupport, altho no guarantee, that afelon who owns firearm is distinctfrom felon who possesses, suchthat the offense is not an AF. 81Plead specifically to ownership <strong>and</strong>sanitize the ROC of facts showingcontrol, access or possession. Pleacd be, e.g., “On December 12,2012 I knowingly owned a firearmafter a prior conviction for a felony,21

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013than possesses afirearm. SeeAdvice <strong>and</strong> seeNote: Firearms.weapon other thana firearm. SeeAdvice.to wit: __.”A better plea is PC 30305, felonwho owns ammunition, for personwho also need to avoid adeportable firearms offense.P.C.§30305Possession,ownership ofammunitionby personsdescribed in29800See 29800,supra. SeeAdviceSee 29800No. Firearmsdeport grounddoes not includeammunition. 82Note that being anaddict can bedeportable,inadmissible. SeeNote: DrugsTo avoid AF, see Advice for 29800.Why ammo? Felon owning ammomay avoid an AF like 29800, <strong>and</strong>avoid the firearms deport grnd.See Note: FirearmsP.C.§33215Possess,give, lend,keep for saleshortbarreledshotgun orrifleSale is an AF astrafficking.Avoid 1 yr on anyone felony count.See Note:Sentence <strong>and</strong>see Advice.Possession isnot a CIMT.Sale mightbe, givingwould not be.Yes, deportablefirearms offenseunless ROCshows antique(see PC 25400).Older decisions held felonypossession of these weapons is aCOV. While arguably thesedecisions were overturned by theSupreme Court, 83 try hard to avoid1 yr on any one count. Try to avoidthis conviction regardless ofsentence imposed.P.C. §§32625,33410Possessionof silencer;possessionor sale ofmachinegunSee 33215 See 33215 See 33215. See 33215Veh. C.Code §20Falsestatement toDMVNot AFShd not beCIMT. SeeAdviceNo.To avoid CIMT plead to specificfalse fact (if possible, one that isnot material), not to gain a benefit.Veh. C.§31False info toofficerNot AF See VC § 20 No. See VC § 20Veh. C.§2800.1Flight frompeace officerNot AFProbably notCIMTNo.Veh. C.§2800.2Flight frompeace officerwith wantondisregard forsafetyShd not be COV,but because ofbad oldercaselaw, avoid 1yr on any singlecount or seeAdvice.Divisible asCIMT: 3 priorviolations notnecessarilyCIMT, butother wantondisregard isCIMT. 84 No. Avoid AF: 1) Wanton by plea to 3prior violations is not per se COV. 852) Wanton/reckless disregard alsois not COV because recklessnessis not COV. There is older caselawto the contrary but it shd beconsidered overruled. 86 Mostsecure is to avoid 1 yr on anysingle count, <strong>and</strong>/or plead orreduce to a misdemeanor.Veh. C.§4462.5Displayimproper regw/ intent toavoid vehicleregistrationNo. No. No.22

Immigrant Legal Resource Center, www.ilrc.org <strong>California</strong> <strong>Chart</strong> 2013Veh. C.§10801-10803OperateChop Shop;Traffic invehicles withaltered VINs,To avoid AF,avoid 1 yr on anysingle count.Otherwise,divisible as atheft AF <strong>and</strong> avehicle withaltered numberoffense AF. SeeAdvice.Yes CIMT No. AF: 10801 is divisible for theftbecause it can involve fraud ratherthan theft. 87 If must take a 1-yrsentence on a single count, butloss to victim/s less than $10k,plead to fraud.10801 appears divisible for VINbecause activity is not limited toVIN. If must take a 1-yr sentenceon a single count, plead to 10801leaving open possibility that carobtained by fraud <strong>and</strong> that alteringVIN was not the chop shop activity.10802, 10803 may not be divisiblefor VIN; avoid 1 yr sentence.Veh. C.§10851Vehicletaking,temporary orpermanentTo avoid AF,avoid 1 yr on anysingle count. 88See Note:Sentence.Divisible asCIMT. SeeAdvice.No.CIMT: CIMT if permanent intent,not CIMT if temporary intent. 89Plead specifically to temporaryintent, or else imm judge may holdfact-finding hrg on actual intent.Veh. C.§10852Tamperingwith avehicleNot AF but seeAdvice.Appears notCIMT.No.To avoid possible AF charge, don'tlet ROC show that tamperinginvolved altering VIN.Veh. C.§10853Maliciousmischief to avehicleNot AF(misdo with 6monthsmaximum)May bedivisible asCIMT. SeeAdviceNo.CIMT: To avoid possible CIMT,plead to intent to commit specificnon-CIMT, e.g., intent to trespass,temporarily deprive owner, commitsmall non-costly v<strong>and</strong>alismVeh. C.§12500DrivingwithoutlicenseNot AF. Not CIMT. No.Veh. C.14601.114601.214601.5Driving onsuspendedlicense withknowledgeNot AF Not CIMT -but seeAdvice if DUIinvolved <strong>and</strong>warn client itis conceivablethat a CIMTwould becharged.NoCMT: Neither DUI nor driving on asuspended license separately is aCIMT, but a single offense thatcontains both of those elementshas been held a CIMT. 90 No singleCal offense combines DUI <strong>and</strong>driving on a suspended license,<strong>and</strong> the gov’t may not combine twooffenses to try to make a CIMT. 91However to avoid any confusion,where possible do not plead toboth DUI <strong>and</strong> driving on suspendedlicense at same time, or if onemust, keep the factual basis forboth offenses separate. 92Veh. C.§15620Leavingchild invehicleNo. No. Caution: May becharged asdeportable crimeof child abuse.See AdviceChild abuse: Arguably an infractionis not a “conviction” for immpurposes. See Note: Definition ofConviction. If a conviction, it maybe charged as deportable offense.23