in vitro free radical scavenging activity of raw pepino fruit (solanum ...

in vitro free radical scavenging activity of raw pepino fruit (solanum ...

in vitro free radical scavenging activity of raw pepino fruit (solanum ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

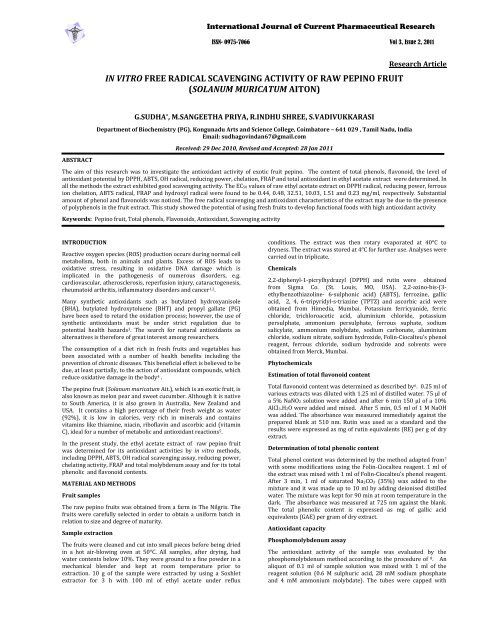

Sudha et al.Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 3, Issue 2, 137140silver foil and <strong>in</strong>cubated at 95°C for 90 m<strong>in</strong>. The tubes were cooledto room temperature and the absorbance <strong>of</strong> aqueous solution wasmeasured at 695 nm aga<strong>in</strong>st a blank. Ascorbic acid were used as astandard. Total antioxidant capacity was expressed nM gallic acidequivalents (GAE) per gram <strong>of</strong> dry extract.DPPH <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong>The scaveng<strong>in</strong>g effect <strong>of</strong> <strong>fruit</strong> extracts on DPPH <strong>radical</strong>s wasdeterm<strong>in</strong>ed accord<strong>in</strong>g to the method <strong>of</strong> 9 . Various concentrations <strong>of</strong>sample (4 ml) were mixed with 1 ml <strong>of</strong> methanolic solutionconta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g DPPH <strong>radical</strong>s, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>al concentration <strong>of</strong>DPPH be<strong>in</strong>g 0.2 mM. The mixture was shaken vigorously and left tostand for 30 m<strong>in</strong>, and the absorbance was measured at 517 nm. Thepercentage <strong>in</strong>hibition was calculated accord<strong>in</strong>g to the formula: (A0‐A1)/A0]×100, where A0 was the absorbance <strong>of</strong> the control and A1 wasthe absorbance <strong>of</strong> the sample.Determ<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> reduc<strong>in</strong>g powerThe reduc<strong>in</strong>g power <strong>of</strong> <strong>fruit</strong> extracts was determ<strong>in</strong>ed accord<strong>in</strong>g tothe method <strong>of</strong> 10 . 2.5 ml <strong>of</strong> various concentrations <strong>of</strong> the extract, 2.5ml phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 6.6) and 2.5 ml and 2.5 ml <strong>of</strong> 1%potassium ferricyanide were mixed and <strong>in</strong>cubated at 50°C for 20m<strong>in</strong> and centrifuged for 10 m<strong>in</strong> at 5000 g after addition <strong>of</strong> 2.5 ml <strong>of</strong>10% trichloroacetic acid. 2.5 ml aliquot <strong>of</strong> supernatant was mixedwith 2.5 ml <strong>of</strong> deionised water and 0.5 ml <strong>of</strong> 0.1% ferric chloride.After 10 m<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>cubation, the absorbance was measured at 700 nmaga<strong>in</strong>st a blank.Chelat<strong>in</strong>g effects on ferrous ionsThe ability <strong>of</strong> the <strong>fruit</strong> extracts to chelate ferrous ions was estimatedby the method <strong>of</strong> 11 . Briefly, 2 ml <strong>of</strong> various concentrations <strong>of</strong> theextracts <strong>in</strong> methanol were added to a solution <strong>of</strong> 2 mM FeCl2 (0.05ml). The reaction was <strong>in</strong>itiated by the addition <strong>of</strong> 5 mM ferroz<strong>in</strong>e(0.2 ml). The mixture was then shaken vigorously and left at roomtemperature for 10 m<strong>in</strong>. The absorbance <strong>of</strong> the solution wasmeasured spectrophotometrically at 562 nm. The percentage<strong>in</strong>hibition <strong>of</strong> ferroz<strong>in</strong>e‐Fe 2+ complex formation was calculated as[(A0‐A1)/A0]×100, where A0 was the absorbance <strong>of</strong> the control, andA1 <strong>of</strong> the mixture conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the extract or the absorbance <strong>of</strong> astandard solution.ABTS <strong>radical</strong> cation scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong>The ABTS <strong>radical</strong> cation scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong> was performed withslight modifications described by 12 . The ABTS ‐+ cation <strong>radical</strong>s wereproduced by the reaction between 7 mM ABTS <strong>in</strong> water and 2.45mM potassium persulfate, stored <strong>in</strong> the dark at room temperaturefor 12 h. Prior to use, the solution was diluted with ethanol to get anabsorbance <strong>of</strong> 0.700 ± 0.025 at 734 nm. Free <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g<strong>activity</strong> was assessed by mix<strong>in</strong>g 10 µl <strong>of</strong> test sample with 1.0 ml <strong>of</strong>ABTS work<strong>in</strong>g standard <strong>in</strong> a microcuvette. The decrease <strong>in</strong>absorbance was measured exactly after 6 m<strong>in</strong>. The percentage<strong>in</strong>hibition was calculated accord<strong>in</strong>g to the formula : [(A0‐A1)/A0]×100, where A0 was the absorbance <strong>of</strong> the control, and A1was the absorbance <strong>of</strong> the sample.Ferric reduc<strong>in</strong>g antioxidant power (FRAP) assayThe FRAP assay was used to estimate the reduc<strong>in</strong>g capacity <strong>of</strong> <strong>fruit</strong>extracts, accord<strong>in</strong>g to the method <strong>of</strong> 13 . The FRAP reagent conta<strong>in</strong>ed2.5 ml <strong>of</strong> a 10 mM TPTZ solution <strong>in</strong> 40 mM HCl, 2.5 ml <strong>of</strong> 20 mMFeCl3.6H2O and 25 ml <strong>of</strong> 300 mM acetate buffer (pH 3.6). It wasfreshly prepared and warmed at 37°C. 900 µl FRAP reagent wasmixed with 90 µl water and 30 µl <strong>of</strong> the extract. The reactionmixture was <strong>in</strong>cubated at 37°C for 30 m<strong>in</strong>utes and the absorbancewas measured at 593 nm.Hydroxyl <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g assayHydroxyl <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>fruit</strong> extracts was assayed bythe method <strong>of</strong> 14 . The reaction mixture 3.0 ml conta<strong>in</strong>ed 1.0 ml <strong>of</strong> 1.5mM FeSO4, 0.7 ml <strong>of</strong> 6 mM hydrogen peroxide, 0.3 ml <strong>of</strong> 20 mMsodium salicylate and varied concentrations <strong>of</strong> the extracts. After<strong>in</strong>cubation for 1 hour at 37°C, the absorbance <strong>of</strong> the hydroxylatedsalicylate complex was measured at 562 nm. The scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong><strong>of</strong> hydroxyl <strong>radical</strong> effect was calculated as follows : [1‐(A1‐A2) / A0]x 100, where A0 is absorbance <strong>of</strong> the control (without extract) and A1is the absorbance <strong>in</strong> the presence <strong>of</strong> the extract, A2 is the absorbancewithout sodium salicylate.Statistical analysisAll assays were carried out <strong>in</strong> triplicates and results are expressedas mean ± SD. The data were subjected to one way analysis <strong>of</strong>variance (ANOVA) and the difference between variousconcentrations were determ<strong>in</strong>ed by DMRT test us<strong>in</strong>g SPSS s<strong>of</strong>tware.The P values <strong>of</strong> < 0.05 were considered significant.RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONThe extraction yield, total phenolic content, total flavonoid contentand total antioxidant <strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> ripe pep<strong>in</strong>o <strong>fruit</strong> extract is presented<strong>in</strong> Table 1. Percent yield <strong>of</strong> ripe ethyl acetate extract <strong>of</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o <strong>fruit</strong>was found to be 13.48%.It was known that plant phenolic compounds are responsible foreffective <strong>free</strong> <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g and antioxidant activities 15 . Thetotal phenol and flavonoid content <strong>of</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o extract were found tobe 24.68 mg GAE/g dry weight, 53.60 mg RE/g dry weightrespectively.The phosphomolybdenum method is based on the reduction <strong>of</strong>molybdenum by the antioxidants and the formation <strong>of</strong> a greenmolybdenum (V) complex, which has an absorption at 695 nm. Thetotal antioxidant capacity observed <strong>in</strong> the ripe ethyl acetate extract<strong>of</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o <strong>fruit</strong> was 303.23 nM GAE/g respectively (Table 1).Table 1: Extraction yield, total phenols, flavonoid contents and phosphomolybdenum assay <strong>of</strong> <strong>raw</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o <strong>fruit</strong> extract #Pep<strong>in</strong>o Extraction yield (%) Total phenols(mg GAE/g) ATotal flavonoids(mg RE/g) BPhosphomolybdenum assay(nM GAE/g) ARaw 13.48 ± 0.39 24.68 ± 0.71 53.60 ± 1.50 303.23 ± 8.79# Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n =3); A GAE ‐ Gallic acid equivalents; B RE‐ Rut<strong>in</strong> equivalentsThe antioxidant properties <strong>of</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o <strong>fruit</strong> were evaluated bydifferent <strong>in</strong> <strong>vitro</strong> antioxidant assays such as reduc<strong>in</strong>g power, DPPH /OH / ABTS <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong>, FRAP and chelation <strong>activity</strong>.DPPH <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong>Be<strong>in</strong>g a stable <strong>free</strong> <strong>radical</strong>, DPPH . is frequently used to determ<strong>in</strong>e<strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> natural compounds. In its <strong>radical</strong> form,DPPH absorbs at 517 nm, but upon reduction with an antioxidant, itsabsorption decreases due to the formation <strong>of</strong> its non‐<strong>radical</strong> form,DPPH–H 16 . Thus, the <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong> <strong>in</strong> the presence <strong>of</strong> ahydrogen donat<strong>in</strong>g antioxidant can be monitored as a decrease <strong>in</strong>absorbance <strong>of</strong> DPPH solution. Figure 1 shows <strong>free</strong> <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g<strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> the <strong>raw</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o extract at different concentrations. The<strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o extract <strong>in</strong>creased with<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g concentrations, with 12.00%, 43.68%, 67.61%, 90.54%and 91.53% scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong> for 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0 mg/mlextract, respectively (Figure 1). The IC50 values was found to be 0.44mg/ml. These results <strong>in</strong>dicated that pep<strong>in</strong>o extract exhibited theability to quench the DPPH <strong>radical</strong>, which <strong>in</strong>dicated that extract wasgood antioxidant with <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong>.Reduc<strong>in</strong>g powerThe reduc<strong>in</strong>g power <strong>of</strong> a compound is related to its electron transferability and may serve as a significant <strong>in</strong>dicator <strong>of</strong> its potential138

Sudha et al.Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 3, Issue 2, 137140antioxidant <strong>activity</strong>. In this assay, the yellow color <strong>of</strong> the testsolution changes to green and blue depend<strong>in</strong>g on the reduc<strong>in</strong>gpower <strong>of</strong> test specimen. Greater absorbance at 700 nm <strong>in</strong>dicatedgreater reduc<strong>in</strong>g power. Figure 2 presents the reductive capabilities<strong>of</strong> the ethyl acetate extract <strong>of</strong> <strong>raw</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o <strong>fruit</strong>. In the concentrationrange <strong>in</strong>vestigated, all the extracts demonstrated reduc<strong>in</strong>g powerthat <strong>in</strong>creased l<strong>in</strong>early with concentration. At 0.4, 0.8, 1.2, 1.6, 2.0mg/ml, reduc<strong>in</strong>g power <strong>of</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o extract were found to be 0.433,0.788, 1.124, 1.161, 1.820 respectively. The IC50 values was found tobe 0.48 mg/ml. The reduc<strong>in</strong>g power <strong>of</strong> the extract might be due totheir hydrogen‐donat<strong>in</strong>g ability. Possibly, pep<strong>in</strong>o <strong>fruit</strong> conta<strong>in</strong> highamounts <strong>of</strong> reductone, which could react with <strong>radical</strong>s to stabilizeand term<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>radical</strong> cha<strong>in</strong> reactions.% <strong>in</strong>hibition <strong>of</strong> DPPH <strong>radical</strong>100806040201243.6867.6190.54 91.5300.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1Sam ple (mg/ml)Fig. 1: DPPH <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> ethyl acetate extract<strong>of</strong> <strong>raw</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o <strong>fruit</strong>Absorbance at 700 nm21.510.500.4430.7881.12 4 1.16 10.4 0.8 1.2 1.6 2Sam ple (mg/ml)Fig. 2: Reduc<strong>in</strong>g power <strong>of</strong> ethyl acetate extract <strong>of</strong> <strong>raw</strong> pep<strong>in</strong><strong>of</strong>ruitMetal chelat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong>Metal ion chelat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> an antioxidant molecule preventsoxy<strong>radical</strong> generation and the consequent oxidative damage. Metalion chelat<strong>in</strong>g capacity plays a significant role <strong>in</strong> antioxidantmechanisms, s<strong>in</strong>ce it reduces the concentration <strong>of</strong> the catalys<strong>in</strong>gtransition metal <strong>in</strong> LPO 17 . The chelat<strong>in</strong>g effects <strong>of</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o extract onferrous ions <strong>in</strong>creased with <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g concentrations (Figure 3). Atconcentrations <strong>of</strong> 10 and 50 mg/ml, the pep<strong>in</strong>o extract exhibitedchelat<strong>in</strong>g effects <strong>of</strong> 19.00% and 69.68%, respectively (Figure 3). TheIC50 values was found to be 32.50 mg/ml. The results <strong>of</strong> the presentstudy suggest that an ethyl acetate extract <strong>of</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o <strong>fruit</strong> exhibitsgood chelat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong> on ferrous ions.ABTS <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong>ABTS assay is an excellent tool for determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the antioxidant<strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> hydrogen‐donat<strong>in</strong>g antioxidants and <strong>of</strong> cha<strong>in</strong>‐break<strong>in</strong>gantioxidants 18 . The extract efficiently scavenged ABTS <strong>radical</strong>sgenerated by the reaction between 2,2’‐az<strong>in</strong>obis (3‐ethylbenzothiazol<strong>in</strong>‐6‐sulphonic acid) (ABTS) and ammoniumpersulfate (Figure 4). The <strong>activity</strong> was found to be <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong> adose‐dependent manner from 50.00% to 98.03% at a concentration1.8 2<strong>of</strong> 10‐50 mg/ml. The extract exhibited an IC50 value <strong>of</strong> 10.03 mg/mL.Therefore, the ABTS <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> ethyl acetateextract <strong>of</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o <strong>fruit</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicates its ability to scavenge <strong>free</strong> <strong>radical</strong>s,thereby prevent<strong>in</strong>g lipid oxidation via a cha<strong>in</strong>‐break<strong>in</strong>g reaction.Scaveng<strong>in</strong>g effect (%)100806040201928.8644.9466.3669.68010 20 30 40 50Sam ple (mg/m l)Fig. 3: Chelat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> ethyl acetate extract <strong>of</strong> <strong>raw</strong> pep<strong>in</strong><strong>of</strong>ruit% <strong>in</strong>hibition <strong>of</strong> ABTS <strong>radical</strong>100806040205081.4488.9895.97 98.03010 20 30 40 50Sam ple (mg/ml)Fig. 4: ABTS <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> ethyl acetate extract<strong>of</strong> <strong>raw</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o <strong>fruit</strong>Ferric reduc<strong>in</strong>g antioxidant power (FRAP)FRAP assay is based on the ability <strong>of</strong> an antioxidant to reduce Fe 3+ toFe 2+ <strong>in</strong> the presence <strong>of</strong> TPTZ, form<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>tense blue Fe 2+ –TPTZcomplex with an absorption maximum at 593 nm. The absorbancedecrease is proportional to the antioxidant content 13 . The trend forferric ions reduc<strong>in</strong>g activities <strong>of</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o extract at differentconcentrations are shown <strong>in</strong> Figure 5. The IC50 values was found tobe 1.51 mg/ml. Our results showed significant ferric reduc<strong>in</strong>gpower which <strong>in</strong>dicated the hydrogen donat<strong>in</strong>g ability <strong>of</strong> the extract.Absorbance at 700 nm21.510.500.6830.9281.2391.4 121.6292 4 6 8 10Sample (mg/ml)Fig. 5: FRAP assay <strong>of</strong> ethyl acetate extract <strong>of</strong> <strong>raw</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o <strong>fruit</strong>139

Sudha et al.Int J Curr Pharm Res, Vol 3, Issue 2, 137140OH <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong>The hydroxyl <strong>radical</strong> is the most reactive <strong>of</strong> the reactive oxygenspecies, and it <strong>in</strong>duces severe damage <strong>in</strong> adjacent biomolecules 19 .The hydroxyl <strong>radical</strong> can cause oxidative damage to DNA, lipids andprote<strong>in</strong>s 20 . The •OH scaveng<strong>in</strong>g` <strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> mushroom extracts wasassessed by its ability to compete with salicylic acid for •OH <strong>radical</strong>s<strong>in</strong> the •OH generat<strong>in</strong>g/detect<strong>in</strong>g system. In the present study, thehydroxyl <strong>radical</strong>‐scaveng<strong>in</strong>g effect <strong>of</strong> the pep<strong>in</strong>o extract, <strong>in</strong> aconcentration <strong>of</strong> 0.2 mg/ml, was found to be 46.46% and <strong>in</strong> aconcentration <strong>of</strong> 1.0 mg/ml, was found to be 89.63%. The IC50 valuewas found to be 0.23 mg/ml. Hence, the pep<strong>in</strong>o extract can beconsidered as a good scavenger <strong>of</strong> hydroxyl <strong>radical</strong>s.% <strong>in</strong>hibition <strong>of</strong> OH <strong>radical</strong>10080604020046.4672.9282.7788.92 89.630.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1Sample (mg/ml)Fig. 6: Hydroxy <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> ethyl acetateextract <strong>of</strong> <strong>raw</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o <strong>fruit</strong>CONCLUSIONIn present study, antioxidant activities <strong>of</strong> the ethyl acetate extractobta<strong>in</strong>ed from <strong>raw</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o were <strong>in</strong>vestigated. The extracts werefound to possess <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g and antioxidant activities, asdeterm<strong>in</strong>ed by scaveng<strong>in</strong>g effect on the DPPH, ABTS, OH <strong>radical</strong>,reduc<strong>in</strong>g power, chelat<strong>in</strong>g effect on ferrous ions, FRAP and totalantioxidant <strong>activity</strong>. Generally, EC50 values <strong>of</strong> lower than 10 mg/ml<strong>in</strong>dicated that the extracts were effective <strong>in</strong> antioxidant properties.In the present study it is found that the ethyl extract <strong>of</strong> pep<strong>in</strong>o <strong>fruit</strong>conta<strong>in</strong>s substantial amount <strong>of</strong> phenolics and flavonoids and it is theextent <strong>of</strong> phenolics present <strong>in</strong> this extract be<strong>in</strong>g responsible for itsmarked antioxidant <strong>activity</strong> as assayed through various <strong>in</strong> <strong>vitro</strong>models. Thus, it can be concluded that ethyl acetate extract <strong>of</strong> pep<strong>in</strong><strong>of</strong>ruit can be used as an accessible source <strong>of</strong> natural antioxidants withconsequent health benefits.REFERENCES1. Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free <strong>radical</strong>s <strong>in</strong> biology andmedic<strong>in</strong>e (3 rd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. 19992. Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cron<strong>in</strong> MT, Mazur M, Telser J.Free <strong>radical</strong>s and antioxidants <strong>in</strong> normal physiologicalfunctions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007; 39:44‐84.3. Park PJ, Jung WK, Nam KD, Shahidi F, Kim SK. Purification andcharacterization <strong>of</strong> antioxidative peptides from prote<strong>in</strong>hydrolysate <strong>of</strong> lecith<strong>in</strong> <strong>free</strong> egg yolk. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2001;78: 651‐656.4. Lana MM, Tijskens LMM.. Effect <strong>of</strong> cutt<strong>in</strong>g and maturity onantioxidant <strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> fresh‐cut tomatoes. Food Chem 2006;97: 203‐211.5. Diaz L. Industrialización y aprovechamiento de productos y subproductosderivados de materias primas agropecuarias de laregión de Coquimbo (1st Edition). Santiago: LOM edicionesLtda. 2006.6. Jia Z, Tang M, Wu J. The determ<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> flavonoid contents <strong>in</strong>mulberry and their scaveng<strong>in</strong>g effects on superoxides <strong>radical</strong>s.Food Chem 1998; 64: 555‐559.7. S<strong>in</strong>gleton VL, Rossi JA. Colorimetry <strong>of</strong> total phenolics withphosphotungstic acid reagents. Am J Enol Vitic 1965; 16:144‐158.8. Prieto P, P<strong>in</strong>eda M, Aguilar M. Spectrophotometric quantitation<strong>of</strong> antioxidant capacity through the formation <strong>of</strong> aphosphomolybdenum complex: specific application to thedeterm<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> vitam<strong>in</strong> E. Anal Biochem 1999; 269: 337‐341.9. Shimada K, Fujikawa K, Yahara K, Nakamura T. Antioxidativeproperties <strong>of</strong> xanthan on the autioxidation <strong>of</strong> soybean oil <strong>in</strong>cyclodextr<strong>in</strong> emulsion. J Agric Food Chem 1992; 40: 945‐948.10. Oyaizu M. Studies on products <strong>of</strong> brown<strong>in</strong>g reactions:antioxidative activities <strong>of</strong> products <strong>of</strong> brown<strong>in</strong>g reactionprepared from glucosam<strong>in</strong>e. Jpn J Nutr 1996;44: 307‐315.11. D<strong>in</strong>is TCP, Madeira VMC, Almeida LM. Action <strong>of</strong> phenolicderivatives (acetam<strong>in</strong>ophen, salicylate, and 5‐am<strong>in</strong>o salicylate)as <strong>in</strong>hibitors <strong>of</strong> membrane lipid peroxidation and as peroxyl<strong>radical</strong> scavengers. Arch Biochem Biophys 1994; 315: 161‐169.12. Re R, Pellegr<strong>in</strong>i N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M, and Rice‐Evans C. Antioxidant <strong>activity</strong> apply<strong>in</strong>g an improved ABTS<strong>radical</strong> cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol Med999; 26: 231‐1237.13. Benzie IFF, Stra<strong>in</strong> JJ. The ferric reduc<strong>in</strong>g ability <strong>of</strong> plasma(FRAP) as a measure <strong>of</strong> “Antioxidant power” The FRAP assay.Anal Biochem. 1996; 239: 70‐76.14. Smirn<strong>of</strong>f N, Cumbes QJ. Hydroxyl <strong>radical</strong> scaveng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong>compatible solutes. Phytochem. 1989; 28: 1057‐1060.15. Velioglu YS, Mazza G, Gao L, Oomah BD. Antioxidant <strong>activity</strong> andtotal phenolics <strong>in</strong> selected <strong>fruit</strong>s, vegetables and gra<strong>in</strong> products.J Agric Food Chem 1998; 46: 4113‐4117.16. Blois MS. Antioxidant determ<strong>in</strong>ations by the use <strong>of</strong> a stable <strong>free</strong><strong>radical</strong>. Nature 1958; 181: 1199‐1201.17. Duh PD, Tu YY, Yen GC. Antioxidant <strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> water extract <strong>of</strong>Harng Jyur (Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat). LWT 1999;32: 269‐277.18. Leong LP, Shui G. An <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>of</strong> antioxidant capacity <strong>of</strong><strong>fruit</strong>s <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>gapore markets. Food Chem, 2002; 76: 69‐75.19. Gutteridge MC. Re<strong>activity</strong> <strong>of</strong> hydroxyl and hydroxyl‐like <strong>radical</strong>sdiscrim<strong>in</strong>ated by release <strong>of</strong> thiobarbituric acid reactivematerial from deoxy sugars, nucleosides and benzoate.Biochem J 1984; 224: 761−767.20. Spencer JPE, Jenner A, Aruoma OI. Intense oxidative DNAdamage promoted by L‐DOPA and its metabolites, implicationsfor neurodegenerative disease. FEBS Lett 194; 353: 246‐250.140