The Challenge of Low-Carbon Development - World Bank Internet ...

The Challenge of Low-Carbon Development - World Bank Internet ... The Challenge of Low-Carbon Development - World Bank Internet ...

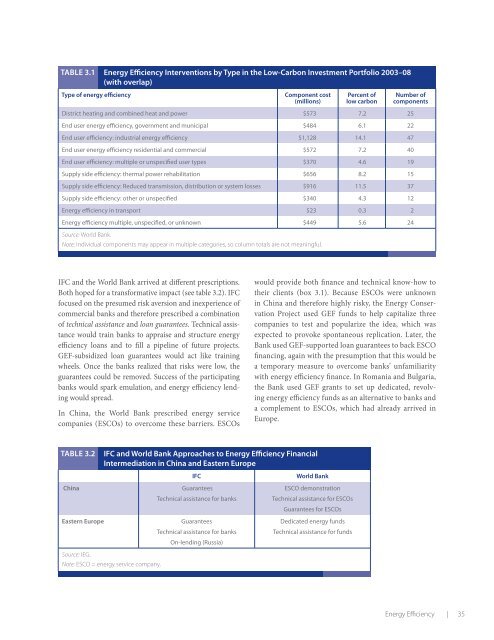

Energy EfficiencyThe first phase in this evaluation series (IEG 2009) assessed projects related todemand-side efficiency policy and to energy pricing. It highlighted the importanceof removing poorly targeted energy subsidies as a win-win policy that can promoteenergy efficiency, poverty reduction, fiscal balance, and GHG reductions.Since then, the Bank has codirected a G20 study to examinepolicies to reduce energy subsidies (IEA and others 2010).The previous evaluation also urged increased attention forthe intersection between efficiency investments and pricingreform. Such attention is now evident in the VietnamPower Sector Development Policy Operation (2010).Energy Efficiency in the First PhaseEvaluationDistrict heating was one area of World Bank activity reviewedin the Phase I report. Concentrated mostly inEastern Europe, this has been a large area of energy efficiencyemphasis. Over the period 1991–2008, there were41 projects with $2.1 billion in commitments. Of the 25closed projects, about three-quarters had outcomes thatIEG rated moderately satisfactory or better. To a largeextent these were “engineering” projects focusing on supply-sideefficiency improvements. However, some includedpolicy elements such as tariff reform. Some ongoingChinese projects are combining supply-side interventionswith promotion of far-reaching reforms that provide consumerswith the means and incentive to reduce excessiveenergy use.In its review, IEG found 34 projects initiated over 1996–2007 that had policy content that related (under a broaddefinition) to end-user efficiency. These included nine thatsupported the creation of appliance or building standards.Although the projects were successful in supporting adoptionof codes, there was been less attention over this periodto sustained support for implementation and enforcement,and very little monitoring and evaluation of impacts. Therewere about a dozen projects that supported demand-sidemanagement, usually through a utility.Complementing the earlier volume, this chapter reviewsseveral energy efficiency business lines that are large involume or have potential for scale-up: transmission anddistribution (T&D) loss reduction, financial intermediaries,direct IFC investments in industrial energy efficiency,and promotion of efficient light bulbs (table 3.1 puts this inthe context of all low-carbon investments from 2003–08).Using Financial Intermediaries to OvercomeBarriers to Energy Efficiency InvestmentsIn China, Eastern Europe, and Russia, a history of commandeconomies and low energy prices had fosteredindustries and housing that were wasteful of energy. Startingin the 1990s, the World Bank and IFC moved in parallelto equip financial intermediaries to promote energyefficiency in these regions. These efforts were mostly supportedby GEF and had GHG reduction as a goal. This sectionreviews 11 such projects (table C.4, which includesall but two of the energy efficiency financial intermediaryprojects initiated by 2005). 1Diagnosis of barriersThe projects had similar diagnoses of energy efficiencybarriers:• Banks do not understand energy efficiency financing. Inthis view, banks either did not understand that the savingsflow from energy efficiency improvements couldback a loan or did not know how to appraise that flowor the exaggerated the risk of these loans.• End users—factory or housing owners—do not understandtheir energy efficiency savings potential or howto realize it.Although the World Bank and IFC hadsimilar diagnoses of barriers to energyefficiency, they arrived at differentprescriptions.34 | Climate Change and the World Bank Group

Table 3.1 Energy Efficiency Interventions by Type in the Low-Carbon Investment Portfolio 2003–08(with overlap)Type of energy efficiencyComponent cost(millions)Percent oflow carbonNumber ofcomponentsDistrict heating and combined heat and power $573 7.2 25End user energy efficiency, government and municipal $484 6.1 22End user efficiency: industrial energy efficiency $1,128 14.1 47End user energy efficiency residential and commercial $572 7.2 40End user efficiency: multiple or unspecified user types $370 4.6 19Supply side efficiency: thermal power rehabilitation $656 8.2 15Supply side efficiency: Reduced transmission, distribution or system losses $916 11.5 37Supply side efficiency: other or unspecified $340 4.3 12Energy efficiency in transport $23 0.3 2Energy efficiency multiple, unspecified, or unknown $449 5.6 24Source: World Bank.Note: Individual components may appear in multiple categories, so column totals are not meaningful.IFC and the World Bank arrived at different prescriptions.Both hoped for a transformative impact (see table 3.2). IFCfocused on the presumed risk aversion and inexperience ofcommercial banks and therefore prescribed a combinationof technical assistance and loan guarantees. Technical assistancewould train banks to appraise and structure energyefficiency loans and to fill a pipeline of future projects.GEF-subsidized loan guarantees would act like trainingwheels. Once the banks realized that risks were low, theguarantees could be removed. Success of the participatingbanks would spark emulation, and energy efficiency lendingwould spread.In China, the World Bank prescribed energy servicecompanies (ESCOs) to overcome these barriers. ESCOswould provide both finance and technical know-how totheir clients (box 3.1). Because ESCOs were unknownin China and therefore highly risky, the Energy ConservationProject used GEF funds to help capitalize threecompanies to test and popularize the idea, which wasexpected to provoke spontaneous replication. Later, theBank used GEF- supported loan guarantees to back ESCOfinancing, again with the presumption that this would bea temporary measure to overcome banks’ unfamiliaritywith energy efficiency finance. In Romania and Bulgaria,the Bank used GEF grants to set up dedicated, revolvingenergy efficiency funds as an alternative to banks anda complement to ESCOs, which had already arrived inEurope.Table 3.2IFC and World Bank Approaches to Energy Efficiency FinancialIntermediation in China and Eastern EuropeIFCWorld BankChina GuaranteesTechnical assistance for banksESCO demonstrationTechnical assistance for ESCOsGuarantees for ESCOsEastern EuropeGuaranteesTechnical assistance for banksOn-lending (Russia)Dedicated energy fundsTechnical assistance for fundsSource: IEG.Note: ESCO = energy service company.Energy Efficiency | 35

- Page 19 and 20: should have been strengthened in th

- Page 21 and 22: Major monitorable IEGrecommendation

- Page 23 and 24: Major monitorable IEGrecommendation

- Page 25 and 26: Chairman’s Summary: Committee onD

- Page 27 and 28: most places. Before we get there, w

- Page 29 and 30: non-Annex I countries. The World Ba

- Page 31 and 32: attention. In a couple of decades,

- Page 33 and 34: GlossaryAdditionalityBankabilityBas

- Page 35 and 36: Joint ImplementationA mechanism und

- Page 37 and 38: Chapter 1evALuAtiOn HiGHLiGHts• T

- Page 39 and 40: of interventions, from technical as

- Page 41 and 42: would allow industrialized countrie

- Page 43 and 44: growth, poverty reduction (includin

- Page 45 and 46: Table 1.1 Map of the EvaluationSect

- Page 47 and 48: Chapter 2eValuaTION HIGHlIGHTS• W

- Page 49 and 50: Table 2.2Evaluated World Bank Renew

- Page 51 and 52: Figure 2.2Breakdown of 2003-08 Low-

- Page 53 and 54: Table 2.4 Commitments to Grid-Conne

- Page 55 and 56: Box 2.1The Economics of Grid-Connec

- Page 57 and 58: on average (Iyadomi 2010). (Reducti

- Page 59 and 60: and industrial policy. An increasin

- Page 61 and 62: Table 2.6Hydropower Investments by

- Page 63 and 64: costs for remaining unelectrified a

- Page 65 and 66: World Bank experienceTwo factors ac

- Page 67: Box 2.5On-Grid and Off-Grid Renewab

- Page 72 and 73: Box 3.1ESCOs and Energy Performance

- Page 74 and 75: have had limited causal impact on t

- Page 76 and 77: measurement of achieved economic re

- Page 78 and 79: Since the early 1990s, public entit

- Page 80 and 81: part with a $198 million IDA credit

- Page 83 and 84: Chapter 4eVAluATioN HigHligHTS• B

- Page 85 and 86: The WBG urban transport portfolio (

- Page 87 and 88: y conventional transport systems, i

- Page 89 and 90: include the forest carbon projects

- Page 91 and 92: for Costa Rica for the period 2000-

- Page 93 and 94: After 20 years of effort, systemati

- Page 95 and 96: orrowers have demonstrated the abil

- Page 97 and 98: Chapter 5EVALuATioN HigHLigHTS• O

- Page 99 and 100: Consequently, the efficiency with w

- Page 101 and 102: technologies could accelerate diffu

- Page 103 and 104: A second issue, inherent to any adv

- Page 105 and 106: goal of promoting wind turbine impr

- Page 107 and 108: ConclusionsThe WBG’s efforts to p

- Page 109 and 110: Table 5.1Carbon Funds at the World

- Page 111 and 112: demonstration initiative. The Commu

- Page 113 and 114: Impacts on technology transferThe 2

- Page 115 and 116: Chapter 6Photo by Martin Wright/Ash

- Page 117 and 118: Figure 6.1800Economic and Carbon Re

- Page 119 and 120: Specifically, the WBG could:• Pla

Table 3.1 Energy Efficiency Interventions by Type in the <strong>Low</strong>-<strong>Carbon</strong> Investment Portfolio 2003–08(with overlap)Type <strong>of</strong> energy efficiencyComponent cost(millions)Percent <strong>of</strong>low carbonNumber <strong>of</strong>componentsDistrict heating and combined heat and power $573 7.2 25End user energy efficiency, government and municipal $484 6.1 22End user efficiency: industrial energy efficiency $1,128 14.1 47End user energy efficiency residential and commercial $572 7.2 40End user efficiency: multiple or unspecified user types $370 4.6 19Supply side efficiency: thermal power rehabilitation $656 8.2 15Supply side efficiency: Reduced transmission, distribution or system losses $916 11.5 37Supply side efficiency: other or unspecified $340 4.3 12Energy efficiency in transport $23 0.3 2Energy efficiency multiple, unspecified, or unknown $449 5.6 24Source: <strong>World</strong> <strong>Bank</strong>.Note: Individual components may appear in multiple categories, so column totals are not meaningful.IFC and the <strong>World</strong> <strong>Bank</strong> arrived at different prescriptions.Both hoped for a transformative impact (see table 3.2). IFCfocused on the presumed risk aversion and inexperience <strong>of</strong>commercial banks and therefore prescribed a combination<strong>of</strong> technical assistance and loan guarantees. Technical assistancewould train banks to appraise and structure energyefficiency loans and to fill a pipeline <strong>of</strong> future projects.GEF-subsidized loan guarantees would act like trainingwheels. Once the banks realized that risks were low, theguarantees could be removed. Success <strong>of</strong> the participatingbanks would spark emulation, and energy efficiency lendingwould spread.In China, the <strong>World</strong> <strong>Bank</strong> prescribed energy servicecompanies (ESCOs) to overcome these barriers. ESCOswould provide both finance and technical know-how totheir clients (box 3.1). Because ESCOs were unknownin China and therefore highly risky, the Energy ConservationProject used GEF funds to help capitalize threecompanies to test and popularize the idea, which wasexpected to provoke spontaneous replication. Later, the<strong>Bank</strong> used GEF- supported loan guarantees to back ESCOfinancing, again with the presumption that this would bea temporary measure to overcome banks’ unfamiliaritywith energy efficiency finance. In Romania and Bulgaria,the <strong>Bank</strong> used GEF grants to set up dedicated, revolvingenergy efficiency funds as an alternative to banks anda complement to ESCOs, which had already arrived inEurope.Table 3.2IFC and <strong>World</strong> <strong>Bank</strong> Approaches to Energy Efficiency FinancialIntermediation in China and Eastern EuropeIFC<strong>World</strong> <strong>Bank</strong>China GuaranteesTechnical assistance for banksESCO demonstrationTechnical assistance for ESCOsGuarantees for ESCOsEastern EuropeGuaranteesTechnical assistance for banksOn-lending (Russia)Dedicated energy fundsTechnical assistance for fundsSource: IEG.Note: ESCO = energy service company.Energy Efficiency | 35