NCTE Principles of Adolescent Literacy Reform - National Council of ...

NCTE Principles of Adolescent Literacy Reform - National Council of ...

NCTE Principles of Adolescent Literacy Reform - National Council of ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

1<strong>NCTE</strong> <strong>Principles</strong><strong>of</strong><strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong> <strong>Reform</strong>A Policy Research BriefProduced byThe <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> EnglishApril 2006The James R. Squire Office for Policy ResearchThe <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English

2PREFACEOver 8 million students in grades 4–12read below grade level, and 3,000students with limited literacy skillsdrop out <strong>of</strong> high school every school day. Whilethe No Child Left Behind Act <strong>of</strong> 2001 triggeredhighly publicized reports on low levels <strong>of</strong>reading achievement in America’s elementaryschools, middle and high school students facedifferent but no less important literacy challenges.Economic, social, moral, and political forcesall point to the critical role literacy plays in ournational culture and economy. Schools representthe most powerful and pervasive means <strong>of</strong>introducing the next generation into a culture<strong>of</strong> literacy. Traditionally, educators have focusedon the development <strong>of</strong> literacy in the earlygrades, assuming that older students did not needspecial instruction. Recently, however, it hasbecome clear that many middle and high schoolstudents are increasingly under-literate, lackingthe complex literacy skills they will need to besuccessful in an information-driven economy. Arecent report by ACT shows that only about half<strong>of</strong> our nation’s high school students are able toread complex texts. Defined in terms <strong>of</strong> subtle,involved, or deeply embedded ideas, highly sophisticatedinformation, elaborate or unconventionalstructure, intricate style, context-dependentvocabulary, and implicit purposes, complextexts appear frequently in college and the workplace(ACT, 2006). The challenges posed bysignificant numbers <strong>of</strong> under-literate middle andhigh school students who lack the skills necessaryto function successfully in today’s world areas daunting as they are significant.The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English(<strong>NCTE</strong>), the pr<strong>of</strong>essional association representingover 50,000 English/language arts teachers,brings valuable insights and resources to thisimportant issue. With its rich store <strong>of</strong> researchbasedmaterials and its capacity to provide rigorousand systematic pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentand literacy coaching for middle and high schoolteachers, <strong>NCTE</strong> is uniquely positioned to takea leadership role in a national effort to improvethe literacy capacities <strong>of</strong> adolescents. Thisdocument delineates the problems <strong>of</strong> adolescentliteracy and outlines reforms <strong>NCTE</strong> has identifiedas necessary to address them.The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English

3TABLE OF CONTENTSSection IOverview <strong>of</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong> 4Introduction: A Growing Under-Literate Class 4What is <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong>? 5What Strategies Foster <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong>? 6Meeting the Challenge 7Section IIPr<strong>of</strong>essional Development:The Route to <strong>Reform</strong> 8The Importance <strong>of</strong> Teacher Quality 8Centrality <strong>of</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Development 8High Quality Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Development 9Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Development and Student Achievement 11Section IIIPr<strong>of</strong>essional Development to Improve<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong> 12Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Communities in Secondary Schools 12Interdisciplinary Collaboration 13<strong>Literacy</strong> Coaching 14Conclusion 16Works Cited 17The James R. Squire Office for Policy Research

4SECTION IOVERVIEW OF ADOLESCENT LITERACYIntroduction:A Growing Under-Literate ClassThe problems <strong>of</strong> adolescent literacy echo throughseveral recent reports.• The American Institutes for Research (AIR)reports that only 13% <strong>of</strong> American adults arecapable <strong>of</strong> performing complex literacy tasks.• The <strong>National</strong> Assessment <strong>of</strong> EducationalProgress (NAEP) shows that secondaryschool students are reading significantly belowexpected levels.• The <strong>National</strong> Assessment <strong>of</strong> Adult <strong>Literacy</strong>(NAAL) finds that literacy scores <strong>of</strong> highschool graduates have dropped between 1992and 2003.• The <strong>National</strong> Center for Educational Statistics(NCES) reports a continuing and significantreading achievement gap between certainracial/ethnic/SES groups.• The Alliance for Excellent Education (AEE)points to 8.7 million secondary school students—thatis one in four—who are unableto read and comprehend the material in theirtextbooks.• The 2005 ACT College Readiness Benchmarkfor Reading found that only about half thestudents tested were ready for college-levelreading, and the 2005 scores were the lowestin a decade.Meanwhile, our knowledge-based societyand information-driven economy increasinglydemand a more highly literate population. Inthe 21st century United States, it is not enoughto be able to read and write—the literacy demands<strong>of</strong> the global marketplace have grownmore complicated. The U.S. economy dependsupon developing new generations <strong>of</strong> workerswho are competent and confident practitioners<strong>of</strong> complex and varied forms <strong>of</strong> literacy. Readingcomplex texts requires ability to discern deeplyembedded ideas, comprehend highly sophisticatedinformation, negotiate elaborate structuresand intricate style, understand context-dependentvocabulary, and recognize implicit purposes.Both higher education and the workplace presentreaders with complex texts. Without a highlyliterate pool <strong>of</strong> job applicants, employers areforced to look <strong>of</strong>f-shore for well-trained andhighly literate workers from other countries. Inother words, our nation cannot afford an underliterateworkforce.Our nationcannot afford anunder-literateworkforce.At a time when the United States is fosteringdemocracy in other parts <strong>of</strong> the world, thousands<strong>of</strong> American students are unable to use writteninformation to make informed decisions. Whenthese under-literate students leave school, theyare not prepared to participate effectively in ademocratic society. The powerful growth <strong>of</strong>the Internet and increased reliance on electroniccommunication—where complex literacy skillsare essential—requires enhanced capacities <strong>of</strong>all who seek social and intellectual resources.The moral imperatives that led the United Statesto establish public schools during the early daysThe <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English

5<strong>of</strong> nationhood remain: schooling must producecitizens sufficiently skilled in literacy to helpfoster the greater good within our nation and inthe world beyond.What is <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong>?For adolescents, literacy is more than readingand writing. It involves purposeful social andcognitive processes. It helps individuals discoverideas and make meaning. It enables functionssuch as analysis, synthesis, organization, andevaluation. It fosters the expression <strong>of</strong> ideas andopinions and extends to understanding how textsare created and how meanings are conveyed byvarious media, brought together in productiveways. This complex view <strong>of</strong> literacy builds uponbut extends beyond definitions <strong>of</strong> literacy thatfocus on features like phonemic awareness andword recognition.<strong>Literacy</strong> skills come into play in many waysfor all adolescents and adults, encompassing abroad range <strong>of</strong> domains. These include:• analyzing arguments• comparing editorial viewpoints• decoding nutrition information on foodpackaging• assembling furniture• taking doses <strong>of</strong> medicine correctly• determining whether to vote for a stateamendment• interpreting medical tables• identifying locations on a map• finding information online<strong>Literacy</strong> enables learning in a variety <strong>of</strong> disciplinesin complex and important ways. Researchshows, for example, that a media-literacycurriculum can lead students to read with higher<strong>Literacy</strong> is not a technicalskill acquired onceand for all in theprimary grades.comprehension scores, write longer paragraphs,and identify more features <strong>of</strong> purpose and audiencein reading selections ( Hobbs & Frost,2003). Moreover, literacy is not a technical skillacquired once and for all in the primary grades.Rather, students develop it over many years, andthat development continues well into adolescenceand beyond.<strong>Adolescent</strong>s bring many literacy resourcesto middle school and high school, but they faceseveral challenges. The academic discoursesand disciplinary concepts in such fields as science,mathematics, and the social studies entailnew forms, purposes, and processing demandsthat pose difficulties for some adolescents. Theyneed teachers to show them how literacy operateswithin academic disciplines. In particular,adolescents need instruction that integratesliteracy skills into each school discipline so theycan learn from the texts they read. <strong>Adolescent</strong>salso need instruction that links their personalexperiences and their texts, making connectionsbetween students’ existing literacy resourcesand the ones necessary for various disciplines(Alvermann & Moore, 1991). When instructiondoes not address adolescents’ literacy needs,motivation and engagement are diminished.Motivation is the factor that leads students toread or not, and engagement means choosingto read when faced with other options (Guthrieand Wigfield, 2000). Without a curriculum thatfosters qualities <strong>of</strong> motivation and engagement,adolescents risk becoming under-literate.The James R. Squire Office for Policy Research

6What Strategies Foster<strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong>?Research <strong>of</strong>fers many effective strategies thatpromote and increase adolescent literacy. <strong>Reform</strong>ingprograms <strong>of</strong> adolescent literacy demandsstrategies that target motivation, comprehension,and critical thinking.MotivationThe question <strong>of</strong> motivation presents one <strong>of</strong> themost perplexing issues <strong>of</strong> adolescent literacy.Many students who are able to read and writechoose not to, rendering many forms <strong>of</strong> instructionineffectual. Furthermore, as this behaviorbecomes ingrained, students can become lesslikely to become engaged with literacy practices.Research shows, however, ways to increase studentmotivation toward literacy.• Strategy Instruction: Teaching students tomonitor their own literacy practices, to lookfor information, to interpret literature, and todraw on their own prior knowledge enhancesmotivation (Guthrie et al., 1996).• Diverse Texts: Sustained experience withdiverse texts in a variety <strong>of</strong> genres that <strong>of</strong>fermultiple perspectives on life experiences canenhance motivation, particularly if texts includeelectronic and visual media (Greenleafet al., 2001).• Self-selection <strong>of</strong> Texts: Many texts must beread in common by an entire class, as the curriculumdictates, but allowing some discretionfor students to choose their own textsincreases motivation, especially because theseselections can help students make connectionsbetween texts and their own worlds.Of course, reading self-selected texts alsoincreases reading fluency, or the ability toread quickly and accurately (Alvermann, etal., 2000; Moje et al., 2000).ComprehensionMany students leave elementary school ableto decode language without fully understandingwhat it says. <strong>Reform</strong> in adolescent literacyinstruction must include attention to students’ability to comprehend what they read. Fortunately,research-based strategies are available tosupport such learning.• Vocabulary Development: Reading, writing,speaking, and listening can all contribute tovocabulary development. Since each disciplinehas its own vocabulary, students needboth direct and indirect instruction to activelylearn new words (Dole, Sloan, and Trathern,1995.)• Discussion-based Approaches: Makingmeaning from texts is crucial to reading comprehension,and focused discussions aboutacademic texts can help students learn to readbetter at the same time that they learn moreabout a specific field. (Applebee et al., 2003).Strategies like reciprocal teaching, questiongenerating, and summarizing can foster discussions.Critical ThinkingEffective literacy education leads students tothink deeply about texts and use them to generateideas and knowledge. Students can be taughtto think about their own thinking, to understandhow texts are organized, to consider relationshipsbetween texts, and to comprehend complexities.• Self-monitoring: Focused instruction canteach students how to consider their ownunderstandings <strong>of</strong> a text and learn how to proceedwhen their understanding fails (Bereiterand Bird, 1985).• Interpretation and Analysis: A successfulprogram <strong>of</strong> literacy education enables studentsto dissect, deconstruct, and re-constructtexts as they engage in meaning making(Newmann, King, & Rigdon, 1997).The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English

7• Multi-disciplinary: Critical thinking takesslightly different form in each discipline, andeffective instruction for adolescent literacyhelps students develop capacities for criticalthinking in each discipline (Greenleaf et al.,2001).• Technology: Many adolescents are drawnto technology, and incorporating technologyinto instruction can increase motivation at thesame time that it enhances adolescent literacyby fostering student engagement (Merchant,2001).AssessmentAssessment is <strong>of</strong>ten seen as external to instruction,but it is an essential part <strong>of</strong> teaching. Bothteachers and students benefit from multipleforms <strong>of</strong> evaluation. While high-stakes testsrarely provide feedback that has instructionalvalue, other forms <strong>of</strong> assessment can fosterliteracy development in adolescents.• Ongoing Formative Assessment: Assessmentthat provides regular feedback about studentlearning has benefits for students and teachers.It can enhance motivation as well asachievement among students. Teachers whoreceive daily or weekly information aboutstudent development can intervene effectively(Biancarosa and Snow, 2004).• Informal Assessment: Assessment need notbe an onerous task for teachers since there aremany ways to evaluate student achievementinformally. Brief responses to a student journal,students’ written summaries <strong>of</strong> learning atthe end <strong>of</strong> class, or a student-teacher conferenceare examples <strong>of</strong> informal assessment thatdoes not require a grade but provides formativeevaluation <strong>of</strong> student achievement.• Formal Assessment: The test at the end <strong>of</strong>a unit or the paper written in response to amulti-week assignment are examples <strong>of</strong> formalassessment that is usually graded and canbe described as summative rather than formative.When prepared and graded by a teacheras part <strong>of</strong> ongoing instruction, formal assessmentcan provide useful insights into studentlearning (Darling-Hammond et al., 1995).Meeting the Challenge<strong>Reform</strong> designed to improve adolescent literacythrough increased motivation, comprehension,critical thinking, and classroom-based assessmentmust contribute to measurable gains in studentachievement. Instruction that foregroundsinstructional experiences like these will requiresubstantial reform, both in teaching practicesand in the school infrastructures in which theyare enacted. Teachers possess the greatest capacityto positively affect student achievement,and a growing body <strong>of</strong> research shows that thepr<strong>of</strong>essional development <strong>of</strong> teachers holds thegreatest potential to improve adolescent literacyachievement. In fact, research indicates thatfor every $500 directed toward various schoolimprovement initiatives, those funds directedtoward pr<strong>of</strong>essional development resulted in thegreatest student gains on standardized achievementtests (Greenwald et al., 1996).Research indicates thatfor every $500 directedtoward various schoolimprovement initiatives,those funds directedtoward pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment resultedin the greatest studentgains on standardizedachievement tests.The James R. Squire Office for Policy Research

8SECTION IIPROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT: THE ROUTE TO REFORMThe Importance <strong>of</strong> TeacherQualityFormer U.S. Secretary <strong>of</strong> Education Rod Paigerecognized the value <strong>of</strong> well-prepared teachers:“We know that being a highly qualifiedteacher matters because the academic achievementlevels <strong>of</strong> students who are taught by goodteachers increase at greater rates than the levels<strong>of</strong> those who are taught by other teachers” (U.S.Department <strong>of</strong> Education 2003). In makingsuch claims, Paige drew upon research thatdocuments how well-prepared teachers raisethe achievement <strong>of</strong> all students, not just thosewho were already doing well (Babu and Medro,2003; Sanders and Rivers, 1996).The term “highly-qualified teacher,” used byPaige and many others, entered the language <strong>of</strong>education with the No Child Left Behind Act<strong>of</strong> 2001. According to NCLB, highly-qualifiedteachers have a BA degree, full state certification,and knowledge <strong>of</strong> the subject(s) they teach.Teachers can demonstrate subject-matter knowledgewith a major—or credits equivalent to amajor—in the subject they teach, a passing gradein a state test, or a graduate degree.For teachers in middle and high schools, however,literacy is not, for the most part, an area <strong>of</strong>expertise. Those who can be described as highlyqualified in math, social studies, English, orscience rarely have any significant training in literacyinstruction. Traditionally teacher preparationprograms include little (if any) course workin literacy, so it is possible for teachers to beidentified as highly-qualified even though theywere not prepared to address the challenges <strong>of</strong>adolescent literacy. Many content-area teachersdescribe themselves as not prepared to teach lit-eracy within their content area (Phillips, 2002).Ironically, many secondary school teachers resistthe work <strong>of</strong> reading specialists in their schools(Darwin, 2002).Many content-areateachers describethemselves as notprepared to teachliteracy within theircontent area.Centrality <strong>of</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essionalDevelopmentBecause middle and high school teachers whoare highly qualified in some ways can lack fundamentalknowledge about literacy development,pr<strong>of</strong>essional development must be at the center<strong>of</strong> any reform effort that seeks broad improvementin adolescent literacy. Without additionaltraining, teachers at the secondary level remainlargely unable to take up the task <strong>of</strong> enhancingadolescent literacy. Given the demonstrated impact<strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional development upon studentachievement, investing in pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentis both the most cost-effective and systematicway to address the challenges <strong>of</strong> adolescentliteracy at the national level (Greenwald et al.,1996).The quality <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional development is, <strong>of</strong>course, a key concern. All pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentis not created equal, and much <strong>of</strong> whatis described as pr<strong>of</strong>essional development is notsustained or in-depth enough to foster significantThe <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English

9and lasting teacher learning. Because researchshows that student achievement depends uponteachers learning from pr<strong>of</strong>essional development,it is important for high quality pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment in adolescent literacy to bethe standard (Pang and Kamil, 2003).High Quality Pr<strong>of</strong>essionalDevelopmentResearch on pr<strong>of</strong>essional development hasfocused on both teacher learning and studentlearning. Like all learning, teacher learningoccurs over time, and the diagram below showshow effective pr<strong>of</strong>essional development movesteachers, over time, from little or no knowledgeto expertise.Multiple Stages <strong>of</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essionalDevelopment LearningAdapted from Robert B. Cooter’s capacity-building model(Cooter, 2004).Unfortunately much pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentis concentrated at the level <strong>of</strong> “firstexposure” and comes in the form <strong>of</strong> a singleworkshop or presentation on a given teachingstrategy. “Deep learning,” by contrast, involvesextended engagement with new ideas and strategies,such as reading and discussing a text orparticipating in a demonstration. At the “firstexposure” stage, teachers can be described ashaving knowledge about a given approach butlimited capacity to implement it. By contrast,when teachers are able to practice approacheswith support from a mentor or coach who can<strong>of</strong>fer suggestions and encouragement, they areable to implement newly-acquired strategieseffectively. After teachers have had opportunitiesfor supported practice, they then engage inrefined and expanded learning, which is characterizedby a comfortable incorporation <strong>of</strong> newapproaches into regular classroom practices.Pr<strong>of</strong>essional development reaches its ultimatestage when teachers feel comfortable supportingothers in learning a new approach.Time is not, <strong>of</strong> course, the only importantfeature <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional development. The remainder<strong>of</strong> this section will discuss other aspects<strong>of</strong> all effective pr<strong>of</strong>essional development. Thenext section will consider features specific topr<strong>of</strong>essional development focused on adolescentliteracy.Involvement and Commitment <strong>of</strong> allStakeholdersTeachers and staff who will take part in orwho are affected by a program <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment should be part <strong>of</strong> the planningprocess, particularly as fundamental decisionsare being made. Teacher knowledge aboutstudents can help make needs clear—in a needsassessment, for instance—and faculties who areinvolved in planning pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentare much more likely to “buy into” the content<strong>of</strong> the ensuing program. Rather than bringingan outside expert to deliver strategies that willThe James R. Squire Office for Policy Research

10then be implemented by individual teachersin the privacy <strong>of</strong> their own classrooms, teachersand administrators should work together todetermine needs, decide on a course <strong>of</strong> action,and implement development plans (Gusky andHuberman, 1995).Connection with Local InstructionTo have significant impact, pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentshould link to other parts <strong>of</strong> the instructionalinfrastructure in a given school. Eachschool has a unique context, and the best pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment takes account <strong>of</strong> the multiplefactors that contribute to student learning in thatcontext. These include the community <strong>of</strong> whichthe school is a part, student standards, curricularframeworks, textbooks, instructional programs,and assessments. Attention to the local contextalso includes understanding and acknowledgingthe knowledge and experience teachers bring topr<strong>of</strong>essional development. When teachers canmake connections between mandated standardsor features <strong>of</strong> the existing curriculum and ideasforwarded in pr<strong>of</strong>essional development, they aremuch more likely to incorporate new approachesinto their pedagogical repertoires. Pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment can also help teachers understandand work with standards and curricular frameworksso that they implement them more substantiallyin the classroom (Dutro et al., 2002).Creation <strong>of</strong> a Pr<strong>of</strong>essional CommunityIsolation is a difficulty faced by many teachers,and it frequently leads individuals to leave thepr<strong>of</strong>ession (Hanushek et al., 2001). Conversely,teachers who belong to a study group, a learningcommunity, or some other collaborative enterpriseare most likely to remain in the pr<strong>of</strong>essionas highly successful instructors. Effective pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment fosters collegial relationships,creating pr<strong>of</strong>essional communities whereteachers share knowledge and treat each otherwith respect. Within such communities teacherinquiry and reflection can flourish, and researchshows that teachers who engage in collaborativepr<strong>of</strong>essional development feel confident andwell prepared to meet the demands <strong>of</strong> teaching(Holloway, 2003). Furthermore, teachers whoreflect on their own work engender high-achievingstudents (Darling-Hammond & McLaughlin,1995).EvaluationEvaluation should be part <strong>of</strong> the plan for all pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment. Without careful consideration<strong>of</strong> its effects, pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentcannot improve. Guskey (2000) suggests thatfive levels <strong>of</strong> evaluation be included in order toget a full portrait <strong>of</strong> the strengths and weaknesses<strong>of</strong> a given program <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional development.The five are:• participants’ reactions• participants’ learning• organization support and change• participants’ use <strong>of</strong> new knowledge and skills• student learning outcomesCollecting and analyzing data regarding each<strong>of</strong> these areas is demanding, but without suchinformation it is impossible to determine the effectiveness<strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional development.Effective Pr<strong>of</strong>essionalDevelopment Programs• Continue beyond a single session orstrategy• Require the commitment <strong>of</strong> all stakeholders• Connect with local instruction• Create a pr<strong>of</strong>essional community• Include evaluation• Result in student achievementThe <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English

11Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Development andStudent AchievementStudent development and achievement is theultimate measure <strong>of</strong> success, and research showsthat pr<strong>of</strong>essional development improves studentperformance. Quality <strong>of</strong> teacher influencesstudent achievement more than factors like classsize and classroom peers, and effective teachersproduce better achievement regardless <strong>of</strong> whichcurriculum materials or pedagogical approachesare used (Darling-Hammond & Youngs, 2002).Not surprisingly, when pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentis tailored to classroom practice or content, ithas the greatest impact on student achievement(Garet et al. 2001; Kelleher 2003). In short, investmentin pr<strong>of</strong>essional development pays largedividends in student achievement.A growing body <strong>of</strong> research documents theconnection between systematic and sustainedpr<strong>of</strong>essional development and improved studentachievement. Greenwald et al. (1996) foundthat moderate increases in pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentcould lead to significant increases instudent achievement. Estrada (2005) found thatan extended program <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentimproved student achievement. She alsoobserved that this can result when “all stakeholders,including teachers, researchers, andpr<strong>of</strong>essional developers [are] willing to face thefacts <strong>of</strong> student performance levels, take responsibility,and take the risks inherent in workingtoward improvement” (355). Langer (2000)studied the links between teachers’ pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment and student achievement over fiveyears and found that students whose teachersparticipated in pr<strong>of</strong>essional development improvedsignificantly. She writes, “The teachersInvestment inpr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentpays large dividends instudent achievement.in schools that are beating the odds are in touchwith their students, their pr<strong>of</strong>ession, their colleagues,and society at large . . . The knowledgeand experiences gained in their wide pr<strong>of</strong>essionalarena affect the classroom context, theirstudents’ learning and achievement” (434).The James R. Squire Office for Policy Research

12SECTION IIIPROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT TO IMPROVEADOLESCENT LITERACYThe features <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional development discussedin Part II are important for pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment focused on adolescent literacy.Extended time for teachers to move from littleor no knowledge to being able to mentor othersin specific approaches; the involvement<strong>of</strong> all stakeholders; connection with the localinfrastructure; and the creation <strong>of</strong> a pr<strong>of</strong>essionalcommunity—all <strong>of</strong> these contribute to effectivepr<strong>of</strong>essional development. In addition, somefeatures <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional development applyspecifically to those concerned with adolescentliteracy: pr<strong>of</strong>essional communities in secondaryschools, interdisciplinary collaboration, andliteracy coaching.Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Development toImprove <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Literacy</strong>• Builds pr<strong>of</strong>essional community• Encourages interdisciplinary collaboration• Relies on qualified literacy coaches forguidancePr<strong>of</strong>essional Communities inSecondary SchoolsCollaboration among teachers is always importantto student learning because it enables studentsto see connections across the curriculum.Such collaboration is especially important forPr<strong>of</strong>essionalcommunities amongteachers are mostcommon in elementaryschools and least commonin secondary schools.fostering achievement in literacy among adolescentsbecause literacy enables and requireslearning across the curriculum. Unfortunately,as research shows, pr<strong>of</strong>essional communitiesamong teachers are most common in elementaryschools and least common in secondary schools(Louis & Marks, 1996). Features such as sharedvalues, focus on student learning, deprivatizedpractice, and reflective dialogue are much lesscommon among middle and high school teachersthan among their peers in elementary schools.<strong>Reform</strong> aimed at improving the literacyachievement <strong>of</strong> adolescents will need to encouragepr<strong>of</strong>essional development that helps teacherscreate pr<strong>of</strong>essional communities. The implementation<strong>of</strong> new approaches <strong>of</strong>fered by pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment requires the existence <strong>of</strong> astrong pr<strong>of</strong>essional community that creates asafe environment for teachers to experiment withinnovation (Bryk & Schneider, 2003). Pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment can help create pr<strong>of</strong>essionalThe <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English

13communities in schools. As the research <strong>of</strong>Louis & Marks (1996) shows, characteristics <strong>of</strong>pr<strong>of</strong>essional communities include:• Shared values• Focus on student learning• Collaboration• Deprivatized practice• Reflective dialogueInterdisciplinary Collaboration<strong>Adolescent</strong> literacy is necessarily interdisciplinarybecause middle and high school studentsmust read and write in such fields as science,mathematics, and social sciences as well asEnglish. This means that they need to learnthe forms, purposes, and other textual demandsspecific to multiple disciplines (Kucer, 2005).<strong>Adolescent</strong> literacyis necessarilyinterdisciplinary.Students who have opportunities to read andwrite many types <strong>of</strong> texts become fluent, broadentheir vocabularies, and expand their abilitiesas readers and writers. In particular, studentswho participate in discussions that develop theirunderstanding <strong>of</strong> discipline-specific contentlearn to read and write efficiently and effectively(Applebee et al., 2003). They develop the abilityto recognize how texts are organized in differentdisciplines and begin to consider the varioussocial, political, and historical contexts andpurposes that surround all texts.Whether they are in a science or Englishclass, adolescents need to understand literacy asan array <strong>of</strong> related and complex mental and socialactivities rather than a set <strong>of</strong> discrete skills.This, in turn, will lead them to competenceand engagement as learners (Allington, 2001;Alvermann & Moore, 1991). When studentsin middle and high school experience effectiveliteracy instruction, they develop the ability tothink critically about their own reading and writingpractices. They also become able to explainthe meaning <strong>of</strong> a text and to recognize whenthey do not understand, which is a first step inhelping them move to understanding. Willingnessto monitor their own literacy learning is oneindication <strong>of</strong> student engagement, and researchshows a high correlation between such engagementand improved literacy learning (Taylor etal., 2003).Research shows that pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentassociated with writing across the curriculumleads to more effective interdisciplinary collaborationamong teacher learners (WinchesterSchool District, 1987). When teachers from severaldisciplines work together in the context <strong>of</strong>pr<strong>of</strong>essional development, they are much morelikely to develop working relationships. Furthermore,when teacher learning extends acrossdisciplines it also enhances student achievement(Arbaugh, 2003; Burbank & Kauchak, 2003).Multi-modal literacy, literacy practices thatcan be used in the context <strong>of</strong> multiple sites/texts/media, supports and is supported by interdisciplinarity.Multimodal texts are inherentlyinterdisciplinary because creation <strong>of</strong> them drawsupon several fields <strong>of</strong> inquiry. Similarly, themultidisciplinary nature <strong>of</strong> literacy leads naturallyto multi-modal forms that combine visualand verbal texts in various ways.The James R. Squire Office for Policy Research

14The most promisingform <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment overallappears to be literacycoaching.<strong>Literacy</strong> CoachingThe most promising form <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentoverall appears to be literacy coaching(Kamil, 2003). In this work, literacy specialistsconsult with content teachers to help theminfuse literacy instruction into their teaching.Although qualifications and responsibilities <strong>of</strong>literacy coaches vary from one site to another,most agree that coaches model instruction,observe teachers and make suggestions, leadteacher inquiry groups, and disseminate researchfindings. Qualifications include 1) a strongfoundation in literacy, 2) leadership skills, and3) familiarity with adult learning. Unlike readingspecialists who spend most <strong>of</strong> their time workingwith students, literacy coaches focus on teacherlearning, concerning themselves with increasingthe knowledge and skills <strong>of</strong> teachers and administrators.<strong>Literacy</strong> coaches can help teachers:• provide a bridge between adolescents’ rich literatebackgrounds and school literacy activities• work on school-wide teams to teach literacyin each discipline as an essential way <strong>of</strong> learningin the disciplines• recognize when students are not makingmeaning with text and provide appropriate,strategic assistance to read course content effectively• facilitate student-initiated conversations regardingtexts that are authentic and relevant toreal life experiences• create environments that allow students toengage in critical examinations <strong>of</strong> texts asthey dissect, deconstruct, and reconstruct inan effort to engage in meaning making andcomprehension processes.Together with the International ReadingAssociation (IRA) and other pr<strong>of</strong>essional associations,<strong>NCTE</strong> has developed standards forwhat literacy coaches should know and be ableto do to help teachers. These standards provideguidance for schools seeking to include literacycoaching in their pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentplans. Briefly, the standards (see list on page 15)include general ones directed toward all coachesand content-area-specific ones grounded in thedisciplines.<strong>NCTE</strong> is addressing this challenge by establishing,in cooperation with the InternationalReading Association, the <strong>Literacy</strong> CoachingClearinghouse. The Clearinghouse will provideresearch-based information and service to literacycoaches and educational leaders in schoolsacross the nation.In addition, the Clearinghouse will leadfurther research on literacy coaching in order toanswer questions such as these:• In what domain—student learning, teacherlearning, or school climate—is the impact <strong>of</strong>literacy coaches greatest?• How can schools collect their own data aboutthe effects <strong>of</strong> literacy coaching on studentachievement?• How can we compare literacy coaches acrosscontexts?• What are the characteristics <strong>of</strong> highly effectivecoaches?Continued on page 16The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English

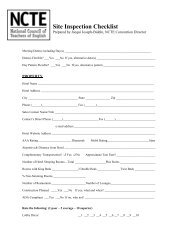

15STANDARDS FOR LITERACY COACHES *1) Skillful CollaboratorsWorking with the school’s literacy team, literacy coaches determine the school’sstrengths (and need for improvement) in the area <strong>of</strong> literacy in order to improvestudents’ reading, writing, and communication skills and content area achievement.2) Skillful Job-Embedded Coaches<strong>Literacy</strong> coaches work with teachers individually, in collaborative teams, an/orwith departments, providing practical support on a full range <strong>of</strong> reading, writing,and communication strategies3) Skillful Instructional Strategists<strong>Literacy</strong> coaches lead faculty in the selection and use <strong>of</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> assessmenttools as a means to make sound decisions about student literacy needs as related tothe curriculum and to instruction.4) Content area literacy coaches are accomplished middle and high school teacherswho are skilled in developing and implementing instructional strategies to improveacademic literacy in English language arts.5) In English language arts, mathematics, science, and social studies literacycoaches are familiar with the content area and know how reading and writingprocesses intersect with the given discipline.* For a full description <strong>of</strong> each standard, seehttp://www.ncte.org/library/files/About_<strong>NCTE</strong>/Education_Issues/coaching_standards.pdfThe James R. Squire Office for Policy Research

16• What is the relationship between coaches’familiarity with content area standards and effectiveintegration <strong>of</strong> literacy instruction intocontent area lessons?• How does a coach’s knowledge in a givencontent area affect the teacher’s sense <strong>of</strong> expertise?• Which qualities <strong>of</strong> literacy coaches correlatemost highly with enhanced student achievementin literacy?• What reading comprehension strategies arebest received by teachers?• Which comprehension strategies and practicesare most effective for students?• What is the optimum context for teacher-literacycoach planning and evaluation <strong>of</strong> instruction?• How do coach-led teams allocate literacy andcontent area instruction?• What differences between content-area teachers’practices can be attributed to participationin coach-led teacher meetings?Answering questions like these can be describedas a practice-embedded research (Donovan,Wigdor, and Snow, 2003). Such researchstarts with the practice as it exists and, buildingon successful teacher practices already in place,addresses practitioner questions while also accumulatingdata across sites. The findings willIt will take approximatelyten thousand literacycoaches to help the ninemillion fourth- throughtwelfth-graders whostruggle with reading(Sturtevant, 2003).inform the training and evaluation <strong>of</strong> literacycoaches. Ultimately, <strong>of</strong> course, the Clearinghousewill be an instrument <strong>of</strong> reform focusedon improving student achievement by enhancingthe development <strong>of</strong> under-literate adolescents.CONCLUSION<strong>Reform</strong> in adolescent literacy requires a recognition<strong>of</strong> the seriousness <strong>of</strong> the problem as wellas a reconceptualization <strong>of</strong> the role <strong>of</strong> secondaryschool teachers in all fields, including theintroduction <strong>of</strong> new approaches to teaching,new forms <strong>of</strong> collaboration, and systematicassessment <strong>of</strong> results. Pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentpromises to be the most productive area onwhich to focus reform efforts because researchshows that pr<strong>of</strong>essional development yields thegreatest improvement in student achievement.The most effective form <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment is <strong>of</strong>fered by literacy coaches, andthe need is urgent. It will take approximately tenthousand literacy coaches to help the nine millionfourth- through twelfth-graders who struggle withreading (Sturtevant, 2003). Meeting this challengewill require concerted and collaborativeefforts <strong>of</strong> a number <strong>of</strong> groups, including teachers,administrators, policy makers, higher education,and pr<strong>of</strong>essional associations like the <strong>National</strong><strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English.The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English

17WORKS CITEDACT. (2006). Reading between the lines: Whatthe ACT reveals about college readiness inreading. http://www.act.org/path/policy/reports/reading.html.Alvermann, D. & Moore, D. (1991). Secondaryschool reading. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P.Mosenthal, and P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook<strong>of</strong> Reading Research (Vol. 2, pp. 951–983). New York: Longman.Alvermann, D. E., Hagood, M. C., Heron, A.,H., Hughes, P., Williams, K. B., and Jun, Y.(2000). After school media clubs for reluctantadolescent readers. Final Report (SpencerFoundation Grant #199900278).Applebee, A., Langer, J., Nystrand, M., andGamoran, A. (2003). Discussion-based approachesto developing understanding: Classroominstruction and student performance inmiddle and high school English. AmericanEducational Research Journal 40(3), 685–730.Babu, S. and Mendro, R. (2003). Teacher accountability:HLM-based teacher effectivenessindices in the investigation <strong>of</strong> teachereffects on student achievement in a stateassessment program. Paper prepared for the2003 American Educational Research AssociationMeeting, Chicago, IL.Baier, J. D., Cook, A. L., Baldi, S. (2006). Theliteracy <strong>of</strong> America’s college students. Washington,DC: American Institutes <strong>of</strong> Research.Bereiter, C. and Bird, M. (1985). Use <strong>of</strong> thinkingaloud in identification and teaching <strong>of</strong>reading comprehension strategies. Cognitionand Instruction 2, 131–56.Biancarosa, G., and Snow, C. E. (2004). Readingnext—A vision for action and research inmiddle and high school literacy: A report toCarnegie Corporation <strong>of</strong> New York. Washington,DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.Burbank, M. D., and Kauchak, D. (2003). Analternative model for pr<strong>of</strong>essional development:Investigations into effective collaboration.Teaching and Teacher Education 19(5),499–514.Cooter, R.B. (2004). Deep training + coaching:A capacity-building model for teacher development.Perspectives on rescuing urban literacyeducation: Spies, saboteurs, and saints.Mahweh, NJ: Erlbaum.Darling-Hammond, L., Ancess, J., and Falk,B. (1995). Authentic assessment in action:Studies <strong>of</strong> schools and students at work. NewYork: Teachers College Press.Darling-Hammond, L., & McLaughlin, M.W.(1995). Policies that support pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment in an era <strong>of</strong> reform. Phi DeltaKappan. 76, 597–604.Darling-Hammond, L., Youngs, P. (2002). Defining“highly qualified teachers”: What doesscientifically-based research tell us? EducationalResearcher, 31(9), 13–25.Darwin, M. (2002). Delving into the Role <strong>of</strong> theHigh School Reading Specialist. Unpublisheddoctoral dissertation, George Mason University.Dole, J. A., Sloan, C., & Trathen, W. (1995).Teaching vocabulary within the context <strong>of</strong>literature. Journal <strong>of</strong> Reading 38(6), 452–60.Donovan, M. S., Wigdor, A.K., & Snow, C.E.(Eds.). (2003). Strategic education researchpartnership. Washington, DC: <strong>National</strong> AcademiesPress.Dutro, E., Fisk, M. C., Koch, R., Roop, L. J., &Wixson, K. (2002). When state policies meetlocal district contexts: Standards-based pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment as a means to individualagency and collective ownership. TeachersCollege Record 104(4), 787–811.The James R. Squire Office for Policy Research

18Estrada, P. (2005). The courage to grow: A researcherand teacher linking pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentwith small-group reading instructionand student achievement. Research in theTeaching <strong>of</strong> English 39(4), 320–364.Garet , M., et al. (2001). What makes pr<strong>of</strong>essionaldevelopment effective? Results from anational sample <strong>of</strong> teachers. American EducationalResearch Journal 38(4), 915–945.Greenleaf, C., Schoenbach, R. Cziko, C., &Mueller, F. (2001). Apprenticing adolescentreaders to academic literacy. Harvard EducationalReview 71(1), 79-129.Greenwald, R., Hedges, L. V., & Laine, R. D.(1996). The effect <strong>of</strong> school resources onstudent achievement. Review <strong>of</strong> EducationalResearch 66(3), 361–396.Gusky, T., and Huberman, M. (Eds.) (1995).Pr<strong>of</strong>essional development in education: Newparadigms and practices. New York: TeachersCollege Press.Guthrie, J. T., Van Meter, P., McCann, A. D.,Wigfield, A., Bennett, L., Poundstone, C. C.,Rice, M. E., Faibisch, R. M., Hunt, B., &Mitchell, A. M. (1996). Growth <strong>of</strong> literacyengagement: Changes in motivations andstrategies during concept-oriented readinginstruction. Reading Research Quarterly 31,302–332.Guthrie, J. T., & Wigfield, A. (2000). Engagementand motivation in reading. In M.L.Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, & R.Barr (Eds.). Handbook <strong>of</strong> Reading Research(Vol III, pp. 403-22). Mahwah, NJ: LawrenceErlbaum Associates.Hanushek, E. A., Kain, J. E., & Rivkin, S. G.(2001). Why public schools lose teachers(NBER Working Paper No. 8599) Cambridge,MA: <strong>National</strong> Bureau <strong>of</strong> Economic Research.Hobbs, R., & Frost, R. (2003). Measuring theacquisition <strong>of</strong> media-literacy skills. ReadingResearch Quarterly 38, 330–356.Holoway, J. H. (2003). Sustaining experiencedteachers. Educational Leadership 60(8),87–89.Kamil, M. L. (2003). <strong>Adolescent</strong>s and literacy:Reading for the 21st century. Washington,DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.Kelleher, J. (2003). A model for assessmentdrivepr<strong>of</strong>essional development. Phi DeltaKappan 84(10), 751–756.Langer, J. A. (2000). Excellence in English inmiddle and high school: How teachers’ pr<strong>of</strong>essionallives support student achievement.American Educational Research Journal 37(2), 397–439.Louis, K. S., & Marks, H. (1996). Does pr<strong>of</strong>essionalcommunity affect the classroom?Teachers’ work and student experiences inrestructuring schools. Wisconsin Center onorganization and restructuring <strong>of</strong> schools,Madison, WI.Little, J. W. (1993). Teachers’ pr<strong>of</strong>essional developmentin a climate <strong>of</strong> educational reform.Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis15, 129–151.Luke, C. (2003). Pedagogy, connectivity,multimodality, interdisciplinarity. ReadingResearch Quarterly 38, 397–403.Merchant, G. (2001). Teenagers in cyberspace:An investigation <strong>of</strong> language use and languagechange in internet chatrooms. Journal<strong>of</strong> Research in Reading Special Issue: <strong>Literacy</strong>,Home and Community 24, 293–306.Moje, E., Young, J., Readence, J., & Moore, D.(2000). Reinventing adolescent literacy fornew times: Perennial and millennial issues.Journal <strong>of</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> and Adult <strong>Literacy</strong>43(5), 400–410.Newmann, F., King, B., & Rigdon, M. (1997).Accountability and school performance: Implicationsfrom restructuring schools. HarvardEducational Review, 67, 41–74.The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English

19Pang, E., and Kamil, M. (March 2003). Updatesand extensions to the teacher educationresearch database. Presented to the AmericanEducational Research Association, Chicago,IL.Phillips, M.P. (2002). Secondary teacher perceptionsrelating to Alabama Reading Initiativetraining and implementation. (Doctoraldissertation, University <strong>of</strong> Alabama & University<strong>of</strong> Alabama in Birmingham, Birmingham,Alabama). Rivers, 1999.Sanders, W., and Rivers, J. (1996). Cumulativeand residual effects <strong>of</strong> teachers on futureacademic achievement. Knoxville, Tenn.:University <strong>of</strong> Tennessee Value-Added Researchand Assessment Center.Sturtevant, E. G. (2003). The literacy coach:A key to improving teaching and learning insecondary schools. Alliance for ExcellentEducation, Washington, DC.Tylor, B., Pearson, P. D. Peterson, D. S., Rodriquez,M. C. (2003). Reading growth inhigh-poverty classrooms: The influence <strong>of</strong>teacher practices that encourage cognitiveengagement in literacy learning. ElementarySchool Journal 104(1), 3–28.U.S. Department <strong>of</strong> Education (2004). TheSecretary’s third annual report on teacherquality. Washington, DC: Westat.Winchester School District, MA (1987). Winchesterhigh school excellence in educationgrant: Reading and writing across the curriculum.Final report. Washington: Office <strong>of</strong>Educational Research and Improvement.©2006 by the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English.All rights reserved. No part <strong>of</strong> this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, includingphotocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the copyright holder. Additional copies <strong>of</strong> this policy briefmay be purchased from the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English at 1-877-369-6283. A full-text PDF <strong>of</strong> this document may be downloaded freefor personal, non-commercial use through the Association’s Web site: www.ncte.org (requires Adobe’s Acrobat Reader).The James R. Squire Office for Policy Research

20The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English1111 W. Kenyon RoadUrbana, Illinois 61801-10961-877-369-6283 or 217-328-3870Web: www.ncte.orgThe <strong>National</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>of</strong> Teachers <strong>of</strong> English