La Biennale di Venezia

La Biennale di Venezia

La Biennale di Venezia

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Presentation of ASAC – Historical Archives of Contemporary ArtsThe documents and the materials (photographs, catalogues, press kits, press clips, etc.) that bearwitness to the activities of all the Sectors (Visual Arts, Architecture, Cinema, Music and Theatre) ofla <strong>Biennale</strong> <strong>di</strong> <strong>Venezia</strong> are conserved in its Historical Archives of Contemporary Arts (ASAC).Currently, the Historic Fund (the heart of the archives) and the collections of posters, photographsand plates, perio<strong>di</strong>cals, musical scores, documentary collections, me<strong>di</strong>a library and artistic fund, areconserved in the spaces located in the VEGA Scientific and Technological Park in Porto Marghera,and are open to consultation by the public (students, researchers, critics, etc.), thanks to therestoration and reorganization projects completed in recent years with the help of theSoprintendenza Archivistica per il Veneto.The Library is located in the Central Pavilion in the Giar<strong>di</strong>ni <strong>di</strong> Castello. Now that the Funds havebeen stored and catalogued, every year specific exhibitions are organized in the <strong>Biennale</strong>headquarters at Ca’ Giustinian, in collaboration with the various Sectors. ASAC has ongoingcollaboration and exchange programmes, in various fields, with cultural, educational andconservation Institutions, in Italy and abroad.The Library of the <strong>Biennale</strong>The new Library of la <strong>Biennale</strong> is an integral part of the historic Central Pavilion in the Giar<strong>di</strong>ni, asa result of the project that has transformed it into a new multi-purpose structure. The restorationproject was completed in 2010 with the opening of the new, large rea<strong>di</strong>ng room, surrounded by atwo-storey mezzanine floor which carries over 800 linear metres of shelving with 134,000 books, ofwhich 40% are stored on the open shelving, catalogues, monographs, texts and e<strong>di</strong>torial series fromall the Sectors of activity at la <strong>Biennale</strong>: Visual Arts, Architecture, Cinema, Music, Theatre, Dance.The Library is particularly <strong>di</strong>stinguished for its complete collection of catalogues of la <strong>Biennale</strong>since the first e<strong>di</strong>tion of the Art Exhibition in 1895, which has since been complemented by theacquisition of exhibition catalogues from all over the world, becoming one of the most completecollections with over 70,000 books at the <strong>di</strong>sposition of scholars and researchers. In order to identifyguidelines for the acquisitions policy in years to come, in 2009 the “Bibliography of the Exhibition”was introduced: the artists and architects invited to the Exhibitions must contribute the publicationsthey deem most significant regar<strong>di</strong>ng the works on <strong>di</strong>splay. The initiative has proven effective and900 books per year have been collected for Art and Architecture. New acquisitions also derivefrom an intense and prolific exchange between institutions. The Library is open all year, and may beaccessed from Calle del Paludo Sant’Antonio, and when the Exhibitions are open, inclu<strong>di</strong>ngSaturday and Sunday.

VIDEO MEDIUM INTERMEDIUM: thematic explorationsVideogallery by Gerry SchumIn 1969, the year in which the first video-recor<strong>di</strong>ng equipment came out on the market, GerrySchum announced the foundation of a videogallery in which TV was used as an artistic me<strong>di</strong>um.The video broadcasts, which up to that time were simple reports on art projects, become actualworks of art. The objective was to step out of the restricted elite circle represented by galleries andmuseums. The Fernseh Galerie in Düsseldorf was inaugurated by <strong>La</strong>nd Art, a film by Schumfocusing on the artists who work <strong>di</strong>rectly on the natural environment, outside tra<strong>di</strong>tional exhibitionspaces. The land artist produced works without stable form, subject to natural phenomena and tothe action of time. The film <strong>La</strong>nd Art uses images alone to document the processes lea<strong>di</strong>ng to thecreation of the great installations and works on the environment produced by Earth Art artists suchas Richard Long, Barry Flanagan, Dennis Oppenheim, Marinus Boezem, Robert Smithson, JanDibbets, Walter De Maria. Transferred into video, <strong>La</strong>nd Art was broadcast in April 1969 by atelevision station in Berlin, Freies Berlin. A second broadcast entitled Identifications was producedby Schum the following year. It is a collection of videos lasting 35 seconds to 5 minutes featuringtwenty artists from <strong>di</strong>fferent countries inclu<strong>di</strong>ng Joseph Beuys, Mario Merz, Alighiero Boetti,Daniel Buren, Walter De Maria, Richard Long and Giliberto Zorio.Artists with Fluxus and Happening Art backgroundFluxus was an international movement that spread around 1960 across two major centres, NewYork and Tokyo, and simultaneously through many European cities such as Copenhagen, Paris,Düsseldorf, Amsterdam, London and Nice. George Maciunas, an American artist of Lithuanianorigin, is considered the founder. Giuseppe Chiari was the only Italian artist to join the movement,starting in 1962. The <strong>La</strong>tin word fluxus suggests the idea that art filters into daily life and also refersto the temporary nature of art objects. The exponents of Fluxus are attracted by the idea of total artcombining music, dance, poetry, theatre and performance. Happenings are a practical translation ofthis concept. The word was invented by Allan Kaprow between the Fifties and Sixties to in<strong>di</strong>cateartistic events that emphasize the relationship between the spectator and the performer, and theimportance of randomness and improvisation. The video me<strong>di</strong>um made it possible to record theFluxus events and happenings, thereby transforming their nature. Fleeting situations turned intorepresentations permanently established in time.PerformancePerformance art was developed in the Sixties thanks to the work of conceptual artists who usedtheir own body as a means of expression, inclu<strong>di</strong>ng Marina Abramovich and Simone Forti. Thecon<strong>di</strong>tions conducive to a performance required the presence of four basic elements: time, space,the body of the performer and the relationship between the performer and the public. The

possibility of recor<strong>di</strong>ng these events fostered the <strong>di</strong>ffusion of performances held in the absence ofspectators.Linguistics and tautologyIn the Seventies some artists used video as a means for reflecting on visual and verbal language.They were based on the linguistic theories of Wittgenstein, on semiotics and on Structuralism. JohnBaldessari, for example, used word games and semantic constructs with irony and brillianthumour. He thereby ri<strong>di</strong>culed the pedantry of much of the conceptual art of the time.Self-reflectionsArtists began to turn the video-camera on themselves, using their own body as the preferred subjectof their works, like Vito Acconci and Arnulf Rainer. This practice was not just an exploration ofin<strong>di</strong>vidual identity but also of the relationship between man and society, intimacy and public space,freedom and social con<strong>di</strong>tioning.Electronic ExperimentsStarting in the late Sixties, some artists began to consider video as a plastic me<strong>di</strong>um and to usevarious technical devices to manipulate electronic signals and create an original imaginary ofabstract forms that undergo a continuous metamorphosis. They often relied on the collaboration oftechnical personnel and experts and avant-garde technological <strong>di</strong>scoveries. Two important centersfor electronic art were The Kitchen, a workshop founded in 1971 in New York by Woody andSteina Vasulka and the Experimental Television Center in Binghamton, New York where EdMellnik recorded his first live performances.Extension of artistic experimentation through videoThanks to the spread of new video technology that was cheaper and easier-to-handle than in thepast, at the end of the Sixties the artists <strong>di</strong>scovered a new terrain for experimentation. They had anew tool that could be combined with performance and body art, sculpture and installations, andstrengthened their expressive power. In ad<strong>di</strong>tion, sustains Les Levine, video is a liquid me<strong>di</strong>a thatis constantly changing and evolving. These characteristics made it a highly fascinating me<strong>di</strong>um foran entire generation of artists.

VIDEO MEDIUM INTERMEDIUMVideos in ExhibitionSection 1: Video-gallery by Gerry SchumGerry Schum – TV Show 1. <strong>La</strong>nd Art (1969), 35’ (Boezem, Dibbets, Flanagan, Long, De Maria,Oppenheim, Smithson)Gerry Schum – Tv Show 2. Identifications (1970), 50’ (Anselmo, Beuys, Boetti, Brown, Buren,Calzolari,De Dominicis, Van Elk, Fulton, Gilbert&George, Kuehn, Merz, Rinke, Rueckriem,Ruthenbeck, Serra, Sonnier, Erhard Walther, Weiner, Zorio)Section 2: Fluxus e Happening ArtJoseph Beuys - Vitex Agnus Castus (1972), 11’Giuseppe Chiari - Spoleto Concert 2 (1974), 19’45”Allan Kaprow - Then (1974), 23’38”Nam June Paik - Global Groove (1975), 50’Section 3: Electronic ExperimentsEd Mellnik - A piece to the Puzzle (1975), 4’50”Ed Mellnik - One Minute (1975), 1’03”Pamela Shaw - Cross Currents (1975), 18’24”Nina Sobel - From 73 & 74 (1975) , 4’02”Woody Valsuka - Random Selection. Vocabulary (1973), 5’ 54”Bill Viola - Polaroid Video Stills (1973), 10’59”Section 4: Performance ArtMarina Abramovic - Art must be beautiful, Artists must be beautiful (1975), 8’07”Eleanor Antin - Europa n.1 (1974), 33’11’Christian Boltanski - <strong>La</strong> vie est triste, la vie est gaie ( 1974), 25’Simone Forti - No title Untitled (1973), 29’10”Rebecca Horn - Videotape n.3, (1973), 29’46”Joan Jonas - Merlo (1974), 10’53”Section 5: Linguistics and tautologyVincenzo Agnetti - Documentario n.2 ( 1973), 8’John Baldessarri - The Italian Tape, (1974), 8’32”Dan Graham - Past. Future Split Attention (1975), 17’03”Maurizio Nannucci - The missing Poem is the Poem (1974), 8’

Section 6: Self-reflectionsVito Acconci - Home Movies (1973), 33’24”Douglas Davies - The Florence Tape: clothing, walking, lifting, leaving (1974), 28’21”Ketty <strong>La</strong> Rocca - Appen<strong>di</strong>ce per una supplica (1972), 9’26”Arnulf Rainer - Slow Motion ( 1974), 9’53”Section 7: Extension of artistic experimentation in videoAlighiero Boetti - Ciò che sempre parla in silenzio è il corpo (1974), 1’Les Levine - Outside the Republican Convention (1972), 17’17”Urs Luthi - Self Portrait (1974), 8’Giulio Paolini - Unisono (1974), 1’03”Lucio Pozzi - Portrait of Maria Gloria (1975), 1’09”

Description of the restoration of the art/tapes/22 collectionThe <strong>di</strong>gital preservation of the art/tapes/22 collection began with the collaboration between ASAC -Historical Archives of Contemporary Arts of the <strong>Biennale</strong> <strong>di</strong> <strong>Venezia</strong> and the Università degliStu<strong>di</strong> <strong>di</strong> U<strong>di</strong>ne with CREA (Centro Ricerche Elaborazione Au<strong>di</strong>ovisiva), its production andau<strong>di</strong>ovisual preservation laboratories, and <strong>La</strong> Camera Ottica. The project, conceived jointly by theuniversity located in the Friuli region and the Venetian archives, included the conservation of partof the collection of works that came prevalently from the artistic video production companyart/tapes/22. The purpose of the project was to stabilize the physical and chemical con<strong>di</strong>tions of theoriginal supports, the <strong>di</strong>gital preservation of approximately 200 works and the creation of accesscopies to view the works on DVD and on intranet. The protocol used by the laboratories of theUniversità degli Stu<strong>di</strong> <strong>di</strong> U<strong>di</strong>ne was developed in conformity with the methodologies, decisionmakingmodels and operational protocols adopted in the most important experiences for theconservation of artistic video collections carried out in Europe and in the United States.Restoration proceduresThe first phase of the works served to gather the documentation and the paratexts of the workssubjected to the preservation treatment; it also included the verification of metadata on the coversand on the supports; a survey and philological analysis were conducted on the versions in thecollection. The <strong>di</strong>agnosis of the material state of the supports highlighted the presence of traces ofphysical deterioration caused by exposure to moisture in the conservation spaces and wear causedby use of the tapes. As a result, a chemical, physical and mechanical regeneration process wasundertaken, and the magnetic supports were cleaned. The tapes in the collection were also cleanedand baked to make it possible to reactivate the supports in order to <strong>di</strong>gitize them.The second phase of <strong>di</strong>gital acquisition required the stabilization of the signal and the productionof working copies to assess the technical quality of the image and the state of the work as a text. Bycomparing the information gathered in the earlier documentation phase and, in some cases, bymeans of a comparison with other versions of the same work, the integrity of the text, the qualityof the image and the correspondence between the <strong>di</strong>gitized work and the artistic intentions of theoriginal work were assessed. This made it possible to verify whether the material con<strong>di</strong>tions of the<strong>di</strong>gitized work corresponded to its meaning (from an aesthetic and historical point of view). Whenno <strong>di</strong>screpancy between the <strong>di</strong>gitized copy and the aesthetic and historic intent of the originalwork were noted, a <strong>di</strong>gital conservation copy was produced. In the opposite case, a furtherattempt was made to acquire the signal. The conservation copy (made on an AIT-3 support and ona hard <strong>di</strong>sk) duplicates the original material as faithfully as possible without any e<strong>di</strong>ting orintervention of any sort, and this makes it possible to keep the intervention as reversible aspossible. These <strong>di</strong>gital copies are the new masters that can be used to produce access andexhibition copies. In the process of publishing the access copies, e<strong>di</strong>torial decisions were made torestore the integrity of the works and the original viewing con<strong>di</strong>tions, thereby actualizing and

functionalizing them by virtue of the cultural and aesthetic value of this artistic collection. Thelaboratories of <strong>La</strong> Camera Ottica and CREA also completed a pilot project for the <strong>di</strong>gitalrestoration of the work Portrait of Maria Gloria by Lucio Pozzi. Using algorithms for the <strong>di</strong>gitalcorrection of the image made it possible to eliminate the errors and defects of the video signal dueto corruption caused by the physical deterioration and the material history of the work.

The collection of artists’ videos in ASACThe me<strong>di</strong>a library of the <strong>Biennale</strong> founded by Wla<strong>di</strong>miro Dorigo at the beginning of the Seventiescurrently gathers au<strong>di</strong>o-visual material for an overall number of approximately 9,000 cataloguedtitles, sub<strong>di</strong>vided by <strong>di</strong>scipline: art, film, music, theatre, dance, mass-me<strong>di</strong>a. A significant part ofthese titles refers to cinema and is composed of 3,550 films, inclu<strong>di</strong>ng 1200 reels from the VeniceInternational Film Festival. Another important section of the collection includes over 1,500magnetic-tape video recor<strong>di</strong>ngs produced prevalently between the early Seventies and the lateEighties by the Au<strong>di</strong>o-visual <strong>La</strong>boratory of the <strong>Biennale</strong>, documenting theatre and musicalperformances, dance, animations, street happenings, in<strong>di</strong>vidual and collective interviews,workshops, press conferences, lessons, conversations, exhibitions, conferences, courses, debatesseminars and various events.The remaining part of the me<strong>di</strong>a library is constituted by artists’ videos and the documentation ofhappenings and performances. These works were initially recorded on 1-inch and 1/2 inch openreeltapes, progressively transferred by the Au<strong>di</strong>o-visual laboratory of the <strong>Biennale</strong> into Umatic,VHS and finally DVD formats to guarantee that they may be enjoyed over time despite theobsolescence of the equipment required to view them. A Catalogue-pricelist of the magnetic-videotaperecor<strong>di</strong>ngs of the ASAC printed in 1979 showed that at that time the collection counted 249 originaltapes (masters) of this kind, which have now grown to 1,000, almost 2,000 if we take intoconsideration the various access copies catalogued over time, which in turn required a treatmentsimilar to that of the masters, given that the various typologies of copies on <strong>di</strong>fferent supports havebeen registered with their own inventory number.Since 2005 the latter corpus of the me<strong>di</strong>a library has become part of the Artistic Fund (the collectionof the <strong>Biennale</strong> works of art) to make it easier to manage them and, funds permitting, to initiate anew project to re-order, catalogue, restore and utilize them.The first nucleus of video works at the <strong>Biennale</strong> was collected in 1972 almost by accident withrespect to the intentions of the operators of the time. The idea that the new me<strong>di</strong>a for recor<strong>di</strong>ng onmagnetic tape rather than on film, which cost relatively little, could lead to the development of anew area of artistic creation, was still hard to imagine at that time, and in fact the tapes wereinventoried in the me<strong>di</strong>a library as ‘other video documentation material’. Nevertheless, the firsttapes to be included in the archive were milestones in the development of video art: they were fourreels (one-inch open reels) donated to the 1972 <strong>Biennale</strong> by Gerry Schum, who had beencommissioned to curate the innovative Video-tapes section and especially to involve and stimulatethe creativity of artists who had not yet begun to consider this new means of expression.The inauguration of the ASAC headquarters at Ca’ Corner della Regina in 1976 coincided with the<strong>Biennale</strong>’s acquisition of the entire body of works produced or <strong>di</strong>stributed by the art/tapes/22gallery in Florence. The gallery, founded and <strong>di</strong>rected by Maria Gloria Bicocchi, the energeticcosmopolitan daughter of Futurist painter Primo Conti, sold over 200 tapes made by artists whocame to Florence from various parts of the world: many of them were inexperienced but would in

many cases turn out to be major protagonists of the contemporary art scene. To support them in thedevelopment of their works, Bill Viola was brought in to serve as technical <strong>di</strong>rector from theUnited States, where the technology in this field was more advanced: he would never neglect tounderline on various occasions how important this early Italian experience became for thesubsequent development of his artistic career. Also included in the Bicocchi sale were the entirearchives of the gallery, inclu<strong>di</strong>ng photographic documentation of all kinds, correspondence, books,magazines regar<strong>di</strong>ng the production, exhibition and issues involved in video-art, its production and<strong>di</strong>stribution, economic and technical issues, and its <strong>di</strong>ffusion.These were mostly tapes/masters purchased by Asac with circulation and reproduction rights; insome cases with the right to sell a limited number of copies, in other cases purchased with<strong>di</strong>stribution rights alone, and in some rare cases, with permission only for internal screenings, someof them produced in collaborations between art/tapes/22 and other galleries (for more informationon this issue see the book entitled Arte in videotape art/tapes/22 collezione ASAC <strong>La</strong> <strong>Biennale</strong> <strong>di</strong> <strong>Venezia</strong>,conservazione restauro valorizzazione, e<strong>di</strong>ted by Cosetta Saba, Silvana e<strong>di</strong>trice 2007).In this exciting phase for this new means of communication, the archives set up a viewing room,which was very futuristic for the time, with a series of stations equipped with monitors andheadphones for consultation upon request of both au<strong>di</strong>o and video tapes. In collaboration withMaria Gloria Bicocchi, who briefly became a consultant for ASAC in 1977, a number of initiativeswere held to advance awareness of this means and the ability of artists to use it. In this context, aseminar entitled Artists and videotape was organized, during which the <strong>Biennale</strong> would <strong>di</strong>rectlyproduce a series of videos made by Giuseppe Chiari, Jean Otth, Richard Kriesche, MicheleSambin.The collection would later be expanded with new tapes from the various e<strong>di</strong>tions of the Art<strong>Biennale</strong> and the cycle organized by Asac in 1980 entitled Videotapes from Australia.With the return to painting invoked in the Eighties, interest in video art slowly dwindled, or betteryet, underwent a transformation that led to the creation of video installations that became mucheasier thanks to the evolution of the technology. Acquisitions would not take up again withrenewed vigor until 1986 with the arrival of videos presented in the Installations section, whichraised yet another issue: at this point these videos are elements of a sum total of far more complexworks whose only reason to be is documentation and study, and they represent one or morefragments of a work of art that in turn must be documented by a video to be understood in itscomplexity.Since 2003, the procedure has been reorganized so that the Visual Arts and Architecture sectorssystematically send ASAC service copies of the artists’ videos presented in the various e<strong>di</strong>tions ofthe exhibitions curated <strong>di</strong>rectly by the <strong>Biennale</strong>, though they can only be used for documentationand study.Since 2005, under <strong>di</strong>rector Giorgio Busetto, the <strong>Biennale</strong> began a systematic project to transfer theworks included in the nucleus of video art into <strong>di</strong>gital format, initiating a collaboration with ascientific committee from the University of U<strong>di</strong>ne.The first significant corpus, selected prevalently from the Bicocchi acquisition, was exhibited in 2007for the entire duration of the 52 nd International Art Exhibition in the ASAC spaces in the Arsenale,in concurrence with the beginning of a pilot project created in collaboration with Cosetta Saba andAndrea Lissoni, respectively a professor and student of the University of U<strong>di</strong>ne, the purpose ofwhich was to test which methods were most appropriate for cataloguing and documenting complexmultime<strong>di</strong>a installations and performances with photographic images, videos and interviews. Thesame year Chiara Bertola, as part of the Tribute to Vedova shown in the Venice pavilion, presented aselection of art/tapes/22 videos.

In 2008 about thirty of the most significant videos were loaned by ASAC for the exhibitionart/tapes/22 production organized by Alice Hutchinson at the University Art Museum UAM (LongBeach California State University). On that occasion Hutchinson wanted to explore, in closecollaboration with the artists, the possibility of using new technologies to present works conceivedmostly to be seen on 24-inch black and white monitors, thereby updating the exhibition as far aspossible.Currently the works that have been progressively <strong>di</strong>gitized – the project is an ongoing one – havebeen made available for consultation by appointment on intranet in the various venues of la<strong>Biennale</strong>.

Video art in the history of la <strong>Biennale</strong> <strong>di</strong> <strong>Venezia</strong>The first exhibition of video art entitled Exposition of Music – Electronic Television took place in March1963 in Wuppertal in Germany, and focused on the Korean-born artist and musician Nam JunePaik, considered by many to be the father of electronic art. On that occasion, the images and soundsreproduced by thirteen televisions were deformed by placing a magnet near the cathode ray tube.With this device Paik inaugurated his first manipulations of television images and the creative useof the me<strong>di</strong>um. Two years later in New York he made the video Café Gogo using the first model ofportable video-camera released on the market. This was the foun<strong>di</strong>ng act of video art because acommonplace event – city traffic – was presented as an artistic fact in a process similar toDuchamp’s ready-made. The manipulation of the electronic signal, of broadcasts and recor<strong>di</strong>ngswill remain the in<strong>di</strong>sputable constant in Paik’s work which brings together music, sculpture,painting and film in the immateriality of the electronic image. His experimentations were howeverpreceded by two significant events. In 1952 Lucio Fontana published his manifesto of the spatialmovement for television, co-signed, among others, by Ambrosiani, Burri, Tancre<strong>di</strong>, Deluigi. In 1958the Fluxus artist Wolf Vostell created the first TV dé-collage, an assemblage of objects that recallthe mass society of which electro-acoustic devices and televisions are part.Electronic art appears for the first time in the history of the <strong>Biennale</strong> <strong>di</strong> <strong>Venezia</strong> in 1968 (<strong>di</strong>rector:Gian Alberto Dell’Acqua) in two spaces created by Vostell under the title Omaggio a <strong>Venezia</strong>.Electronic de-coll-age-happening. Room 1959-1968. These are works with a strong visual impactconstituted by light, sound, television sets and photo-electric devices, glass and computers. Thepresence of Vostell, as a representative of the nascent video-art, was part of the <strong>Biennale</strong>’s attemptto bring itself up-to-date with respect to the new fields of artistic expression of those years, in anextremely lively cultural and political climate. Video was taken in this context to be the mostappropriate tool for achieving the “democratization of art” and breaking open the so-called“triangle” of artist-gallery-museum. In ad<strong>di</strong>tion electronic me<strong>di</strong>a allowed the artist great creativefreedom and a substantial reduction in the costs of producing and <strong>di</strong>ffusing the works.In 1969 Germany’s television channel one broadcast a group of videotapes entitled <strong>La</strong>nd Art,produced by Gerry Schum for the “Fernseh Galerie” (videogallery) which opened in Dusseldorfthat same year, and soon became a reference point for video-artists from all over the world. <strong>La</strong>ndArt, devoid of commentary, was a live documentation of interventions on nature and the landscapeby artists such as De Maria, Long, Dibbets and Smithson. The following year Schum producedIdentifications, videos that recorded the actions and performances of international artists such asBeuys, Gilbert & George, Boetti, Serra, Anselmo, De Dominicis, Merz and Zorio. In Schum’sutopian vision TV could have become a formidable tool for the democratic <strong>di</strong>ffusion of art.In 1970 the exhibition Gennaio 70, curated by Renato Barilli, Maurizio Calvesi, Andrea Emilianiand Tommaso Trini opened in Bologna. Defined as “the first exhibition of video-objects <strong>di</strong>rectly

deriving from the work of artists without the me<strong>di</strong>ation of film” is unquestionable one of the mostadvanced presentations in Italy of the new forms of expression such as actions and videoperformances. The same year, the 35 th Art Exhibition of the <strong>Biennale</strong> (<strong>di</strong>rector: Umbro Apollonio)organized the sections Manual, mechanical, electronic, conceptual Production, in which the visitor couldsee the first laser images and works made by computer, and Relax e gioco which set up a closedcircuitTV system.It was in 1972 (<strong>di</strong>rector: Mario Penelope) that video stormed its way into the <strong>Biennale</strong> with its fullcommunicative force, particularly in the section entitled Video-Nastri , curated by Gerry Schum. Inthis exhibition, videotape was presented both as a tool for documenting artists operating in the areaof Performance, Happening, Body and <strong>La</strong>nd Art, and as a means of expression in and of itself, inthe form of video-object. The artists included, among others, Baldessari, Beuys, Buren, DeDominicis, Dibbets, Serra and Weiner. On this occasion, Schum presented his now-famous work<strong>La</strong>nd Art at the <strong>Biennale</strong> for the first time.In Italy during those years, centres for the <strong>di</strong>ffusion and production of video-art proliferated: inFerrara the Centro Videoarte in the Palazzo dei Diamanti founded by Lola Bonora in 1972, inFlorence art/Tapes/22 <strong>di</strong>rected by Maria Gloria Bicocchi assisted by a very young Bill Viola, and inVenice Carlo Cardazzo and the Galleria del Cavallino. In America one of the most importantcentres was The Kitchen, founded in new York by Steina and Woody Vasulka in 1971.In 1974 various exhibitions of video-art were organized in important international museums: at theKunstverein in Cologne the exhibition Video Tapes with works by Acconci and Nauman, at thePalais des Beaux Arts in Brussels Artist’s Video with works by Paik, Vostell and Beuys, and at theMusée d’Art Moderne in Paris the Art Video Confrontation retrospect whose participants includedDan Graham, among others.At the 37 th Art <strong>Biennale</strong> in 1976 (<strong>di</strong>rector: Vittorio Gregotti), entitled Environment.Participation.Cultural structures, video became the ideal me<strong>di</strong>um for live documentation of the political upheavalof that historic period. In the exhibition The Environment as Social, curated by Enrico Crispolti andRaffaele de Grada, the vast au<strong>di</strong>o-visual documentation (interviews, films, videotapes) was todemonstrate how the role of cultural operator had changed and that his role was increasinglybecoming “cultural solicitor”.The most important event that year was however the inauguration, in Ca’ Corner della Regina, ofthe new headquarters of ASAC, the Historical Archives of Contemporary Arts, <strong>di</strong>rected byWla<strong>di</strong>miro Dorigo. ASAC became a centre of the avant-garde thanks to its modern amenities:exhibition spaces, a film screening room, a multime<strong>di</strong>a room, a photographic stu<strong>di</strong>o, monitors andpermanent stations to consult au<strong>di</strong>o and video material.In 1976 Maria Gloria Bicocchi sold ASAC the videotapes made by her gallery art/Tapes/22 whichclosed that year due to problems of financial viability. This was an experimental centre for theproduction, <strong>di</strong>stribution and <strong>di</strong>ffusion of videos made by a range of <strong>di</strong>fferent artists working withinvarious movements such as Pop Art, Minimalism, Arte Povera, Conceptual Art, Fluxus, Body Art,<strong>La</strong>nd Art, Lettrism. In the reminiscences of Bill Viola, who served as technical <strong>di</strong>rector of the centrestarting in 1974, art/Tapes/22 was “a place where artists from all nations could find a commonlanguage in video”. In ad<strong>di</strong>tion to the corpus of videotapes, ASAC also purchased the archives ofthe gallery that contained publications, photographs signed and numbered by the artists, slidesfrom behind-the-scenes made by Gianni Melotti and other documents.In November 1977 the cycle Gli Art/Tapes dell’ASAC was organized to present the materialpurchased by the <strong>Biennale</strong> to the public. The program of screenings included a selection of 39videos and was accompanied by a course in The theory and practice of videotapes in masscommunication, in which American scholar Marshall McLuhan participated, and a seminar

entitled Artists and videotape during which the au<strong>di</strong>o-visual laboratories of ASAC produced a firstseries of videos by Giuseppe Chiari, Richard Kriesche, Jean Otth and Michele Sambin.During the 1978 <strong>Biennale</strong> (<strong>di</strong>rector: Luigi Scarpa), a special project curated by Vittorio Fagone wasde<strong>di</strong>cated to the relationship between art and film and to the comparative analysis of historical andrecent works. The films in the programme were not videos however but Super 8 and 16mm films.Videotapes were featured massively in the next e<strong>di</strong>tion of the <strong>Biennale</strong> in 1980 (<strong>di</strong>rector: LuigiCarluccio). The main exhibition The Art of the Seventies, curated by Achille Bonito Oliva, MichaelCompton, Martin Kunz and Harald Szeemann, de<strong>di</strong>cated an entire section to film and video. It was<strong>di</strong>vided into three parts: Documentation (which presented the report on Arte Povera made by BonitoOliva and Emilio Greco for Rai Television) and Films and video-productions by artists working inperformance art (which presented, among others, the work of Vito Acconci, Rebecca Horn, DennisOppenheim, Ulay and Marina Abramovich from the collections of ASAC). In the catalogueSzeemann underlines how that decade witnessed “a superb tendency to dematerialize art” thatproduced more “formalistic” results in America, whereas in Europe it sought to bring change toman and the community. In the 1980 e<strong>di</strong>tion, video art was also the protagonist of nationalpavilions such as Canada, which presented an ample overview of the country’s video production,and Portugal which exhibited a video performance by Ernest de Sousa; ASAC contributed with thecycle entitled Videotapes from Australia (Ca’ Corner della Regina from 19-31 July).Between the end of the Seventies and the early Eighties, several European cities founded festivalsand programmes de<strong>di</strong>cated to electronic art inclu<strong>di</strong>ng the VideoArtFestival in Locarno and ArsElectronica in Linz.In 1984 the Art <strong>Biennale</strong> <strong>di</strong>rected by Maurizio Calvesi organized a Programmed Selection of Videotapeswhich included over 50 works by the most important artists of the moment and de<strong>di</strong>cated a sectionto Video-installations. After the end of the season of political and social utopias, video was no longerconsidered a tool for dematerializing art, but a means of pure artistic expression.The 42 nd Exhibition in 1986, <strong>di</strong>rected by Giovanni Carandente, featured a futuristic centre fortelematic connection called Ubiqua to explore the potential of new computer technology with a<strong>La</strong>boratory Workshop open to visitors. The section of the exhibition de<strong>di</strong>cated to the Installations<strong>di</strong>splayed works made by using computers, synthesizers, lasers and other electronic devices. Theartists in the show included Bill Viola and Brian Eno.In the Nineties, there was an explosion of electronic me<strong>di</strong>a, which had become a vital instrument forcreative expression. In 1990 (<strong>di</strong>rector: Giovanni Carandente) the United States won the Golden Lionaward for an installation by Jenny Holzer which consisted in LED signboards that reproducedstatements and literary or poetic quotes. In Aperto ’90, the section de<strong>di</strong>cated to young art, the artistsinvited to participate included Stan Douglas, Gudrun Bletz and Ruth Schnell, Border artworkshop-Taller de arte Fronterizo, the Japanese group Complesso Plastico, Theodoulos Gretouand Jana Sterback.In 1993 in the <strong>Biennale</strong> curated by Bonito Oliva, The Car<strong>di</strong>nal Points of Art, electronic art wasfeatured in all the sections of the exhibition in the widest variety of forms. The Golden Lion for bestnational participation was awarded to the Federal Republic of Germany which hosted anextraor<strong>di</strong>nary electronic installation by Nam June Paik in its pavilion, together with a work byHans Aacke. The many electronic works included: videos by Yoko Ono and Mario Schifano,documentations by Luciano Giaccari and experimentations by Grazia Toderi and Pippilotti Rist,both shown in the section Aperto ’93 which included a space de<strong>di</strong>cated to Video/tape/me<strong>di</strong>a.Though the 1995 Art Exhibition <strong>di</strong>rected by Jean Clair favoured figurative art, Gary Hill won theGolden Lion as best artist for a video-installation. Among the national pavilions, several

particularly significant video artists were featured, such as Bill Viola, for the United States, andPeter Fischli and David Weiss for Switzerland.In the 1997 <strong>Biennale</strong>, curated by Germano Celant, the presence of videos and video-installationswas rather limited, except for the recor<strong>di</strong>ng of performances by Marina Abramovich entitled BalkanBaroque, the works of Pippilotti Rist, Douglas Gordon and Sam Taylor Wood. The nationalpavilions featured among other the works of a pioneer of electronic art such as Steina Vasulka andJapanese artist Mariko Mori with a three-<strong>di</strong>mensional <strong>di</strong>gital-video installation.The 48 th Art Exhibition <strong>di</strong>rected by Szeemann in 1999, under the first presidency of Paolo Baratta,presented many video works by recognized artists such as Bruce Nauman, Jenny Holzer andRosemarie Trockel, and younger artists such as Doug Aitken, Grazia Toderi and Shirin Neshat.In 2001, in the second <strong>Biennale</strong> curated by the Swiss critic, the international exhibition and thenational pavilions together counted over one hundred electronic works. The most interesting ofthese works include The Quintet of the Unseen by Bill Viola, winner of the Golden Lion, andWallpiece by Gary Hill. The artists working with video included Stan Douglas, Regina Galindo andAlessandra Tessi. The pavilions featured an array of multi-screen video installations. The Britishpavilion exhibited a video installation by Markus Wallinger, the Cana<strong>di</strong>an pavilion featured awork by Lyndal Jones, Greece exhibited Nikos Navidris and Iceland presented a complexinstallation by Finnbogi Pètursson.The 50 th Exhibition curated in 2003 by Francesco Bonami, supported by eleven other internationalcritics, featured a growing contingent of electronic art, both in the essential form of a video and inmore complex and innovative combinations. Among the various sections, the most interesting wasZ.O.U. Zona d’urgenza organized by Hou Hanrou, which in a relatively small space gathered anincre<strong>di</strong>ble quantity and quality of works produced with an amazing range of electronic devices. Themost significant works included Blue and White by Xu Tan, Let’s puff by Yang Zhenzhong and SafetyInstruction by Zhan Peili.At the beginning of the new millennium, it seemed like that extraor<strong>di</strong>nary idea of thedematerializing and democratizing art through the mass me<strong>di</strong>a, imagined in the Sixties, was goingto be made possible by the <strong>di</strong>ffusion of a means that was far more powerful than television , i.e. theWeb.In the 2005 e<strong>di</strong>tion, curated by Spanish critics Maria de Corral and Rosa Martinez, many of the mostsignificant works proved to be electronic works. The Italian Pavilion, in ad<strong>di</strong>tion to the installationby Tania Bruguera, featured the works of several giants of video-art such as Stan Douglas, JennyHolzer, Bruce Nauman and William Kentridge. At the Arsenale, the main attractions were thelarge space-ship by Mariko Mori, the video-installation by the group Blu Noses and the videoworks by Regina Galindo, winner of the award for young artists. Among the electronic works onexhibit in the national pavilions, those of Pippilotti Rist for Switzerland and Eva Koch for Denmarkdeserve particular mention.The 52 nd Exhibition curated by Robert Storr in 2007 counted more than 40 electronic works andmultime<strong>di</strong>a installations, inclu<strong>di</strong>ng the series of videos Seven Intellectuals in a Bamboo Forest byChinese artist Yang Fudong, the work of the Italian collective Alterazioni Video, the videoinstallationby Austrian VALIE EXPORT and the work of Steve McQueen.In the 2009 e<strong>di</strong>tion of the Art <strong>Biennale</strong> <strong>di</strong>rected by Daniel Birnbaum, the presence of video-art wasless invasive, in particular in the Arsenale which <strong>di</strong>d however feature the three-channel animationby Paul Chan, Sade for Sae’s Sake, the video by Ulla von Barndenburg filmed in the Villa Savoyedesigned by Le Corbusier and the video installation by Grazia Toderi. In the central Pavilion,particularly interesting works included the Claymation film by Nathalie Djurberg (winner of the

Silver Lion for a promising young artist), the kinetic sculpture of Simon Starling which served as afilm projector and the 16mm film by Gordon Matta-Clark Tree Dance made in 1971.The latter brings us back to the origins of video art when, in connection with the contemporary artmovements, it proved to be the most appropriate instrument for the documentation ofperformances and the most fleeting actions to preserve a trace of them over time. As Nam JunePaik correctly pre<strong>di</strong>cted “the experience of au<strong>di</strong>ovisuals, music and video accumulated over historymakes it possible to enter the memory of history. Of course our brain is made like a magnetic tape.”

Video artists awarded in previous e<strong>di</strong>tions of <strong>Biennale</strong> Artyear e<strong>di</strong>tion <strong>di</strong>rector artist award section notes1993 45. Achille BonitoOlivaNam June Paik Coutries Award German pavilion Germany is alsorappresented byHans HaackeMatthew BarneyAward Duemila youngartistOpen 93 exhibits in Artagainst AIDS1995 46. Jean Clair Gary Hill International Award <strong>La</strong><strong>Biennale</strong> <strong>di</strong> <strong>Venezia</strong> -Golden Lion forsculptureIdentityAlterityandRichard Kriesche Honor mention Austrian Pavilion Honor mentionwith Nunzio,Hiroshi Seneju,Jehon Soo Cheon1997 47. Germano Celant Pipilotti Rist Award Duemila youngartistFutur, Present, PastDouglas GordonAward Duemila youngartistFutur, Present, PastSam Taylor-Wood Award illycaffè Futur, Present, Past1999 48. HaraldSzeemannShirin NeshatDoug AitkenGrazia ToderiInternational Award <strong>La</strong><strong>Biennale</strong> <strong>di</strong> <strong>Venezia</strong> -Golden LionInternational Award <strong>La</strong><strong>Biennale</strong> <strong>di</strong> <strong>Venezia</strong> -Golden LionGolden Lion for bestNational participationAPERTO Over All 3 Golden Lion:Doug Aitken, CaiGuo-Qiang andShirin NeshatAPERTO Over All 3 Golden Lion:Doug Aitken, CaiGuo-Qiang e ShirinNeshatItalianinsideOver AllPavilionAPERTOGrazia Toderirappresent Italywith MonicaBonvicini, BrunaEsposito, Luisa<strong>La</strong>mbri, Paola PiviEija-Liisa Ahtila Honor mention Finland Pavilion 3 Honor mention;E.L. Ahtila, GeorgesAdéagbo, KatarynaKozyraKataryna Kozyra Honor mention Poland Pavilion

Bruce Nauman Golden Lion to amasterofcontemporary artAPERTO Over All 2 Lifetimeachievement: BruceNauman and LouiseBougeoisyear e<strong>di</strong>tion <strong>di</strong>rector artist award section notes2001 49. HaraldSzeemannJanet Car<strong>di</strong>ff &George BuresMillerPierre HuygheSpecials Awards "<strong>La</strong><strong>Biennale</strong> <strong>di</strong> <strong>Venezia</strong>"Specials Awards "<strong>La</strong><strong>Biennale</strong> <strong>di</strong> <strong>Venezia</strong>"Anri Sala Specials Awards foryoung artistsCana<strong>di</strong>an PavilionFrance PavilionPlateauHumankindof3 special awards foryoung artists: AnriSala, FedericoFerrero, John Pilson2003 50. FrancescoBonamiJohn Pilson Specials Awards foryoung artistsPlateauHumankindTion Ang Mention Plateau ofHumankindofvideoartphotografy/installations3 special awards foryoung artists: AnriSala, FedericoFerrero, John Pilson,A1-531674 mentions:Tiong Ang, YinkaShonibare, SamuelBecket/MarinKarmitz, JuanDowneyJuan Downey Mention Cile Pavilion 4 mentions:Tiong Ang, YinkaShonibare, SamuelBecket/MarinKarmitz, JuanDowneyOliver Payne eNick RelphAvishKheberhzadehGolden Lion for artistunder 35Award for youngitalian artConflicts anddreams. TheDictatorship of theViewerMinistry of Heritageand Culture -DARC - artwork forNational museumof XXI centuryMAXXIfilmakersvideo -animationSu Mei-TseGolden Lion for thebest NationalParticipationLuxembourgPavilion2005 51. Rosa MartinezMaria de Corral2009 53. DanielBirnbaumRegina JoséGalindoNathalie DjurbergGolden Lion for artistunder 35Silver Lion for bestyoung artistAlways a little bitmorefarthe experience of artMaking WorldsR.J. Galindoparticipate to:Always a little bitmore farMing Wong Special mention Singapor Pavilion Artist cinema/performance2011 54. Bice Curiger Christian Marclay Golden Lion for bestartistILLUMInations

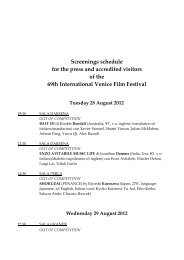

VIDEO MEDIUM INTERMEDIUM – Videolibrary Artists1. Marina Abramovic2. Vito Acconci3. Vincenzo Agnetti4. Giovanni Anselmo5. Eleonor Antin6. Ylona Aron7. Enrico Bafico8. John Baldessari9. Joseph Beuys10. Alighiero Boetti11. Marinus Boezem12. Christian Boltanski13. Corinne bronfman14. Stanley Brown15. Chris Burden16. Daniel Buren17. Richard Calabro18. Pierpaolo Calzolari19. Giancarlo Car<strong>di</strong>ni20. Sandro Chia21. Giuseppe Chiari22. Colette23. James Collins24. Diego Cortez25. Andrea daninos26. Douglas davis27. Gino De Dominicis28. Marco Del Re29. Walter De Maria30. Antonio Dias31. Jan Dibbets32. Ger van Elk33. Franz Erhard Walther34. Barry Flanagan35. Simone Forti36. Hamish Fulton37. Gilbert & George38. Frank Gillette39. Ulrike Golden40. Dan Graham41. Andrea Granchi42. David Hall43. Rebecca Horn44. Peter Hutchison45. Taka Ito (Takahito)Iimura46. Joan Jonas47. Allan Kaprow48. Jannis Kounellis49. Gary Kuehn50. Ketty <strong>La</strong> Rocca51. Elliot <strong>La</strong>ndy52. Richard <strong>La</strong>ndry53. Les Levine54. Richard Long55. Alvin Lucier56. Urs Lüthi57. Andy Mann58. Ed Mellnik59. mario merz60. Gerald Minkoff61. Alberto Moretti62. Antoni Muntadas63. Maurizio Nannucci64. Muriel Olesen65. Luigi Ontani66. Dennis Oppenheim67. Luciano Ori68. Jean Otth69. CharlemagnePalestine70. Giulio Paolini71. Clau<strong>di</strong>o Parmiggiani72. Paolo Patelli73. Alberto Pirelli74. Lucio Pozzi75. Arnulf Rainer76. Klaus Rinke77. Fried Rosenstock78. Ulrike Rosnbach79. Reiner Ruthenbeck80. Ulrich Rückriem81. Michele Sambin82. Mona Sarkis83. Guido Sartorelli84. Richard Serra85. Gerry Schum86. Willoughby Sharp87. Pamela Shaw88. Robert Smithson89. Nina Sobel90. Allan Sondheim91. Allan Sonfist92. Keith Sonnier93. Mike Steiner94. John Sturgeon95. Peggy Stuffi,96. UFO97. Woody Vasulka98. Steina e WoodyVasulka99. Bill Viola100. <strong>La</strong>wrence Weiner101. Nancy KitchellWilson102. Gilberto Zorio