Addisonian Pigmentation of the Oral Mucosa - Cutis

Addisonian Pigmentation of the Oral Mucosa - Cutis

Addisonian Pigmentation of the Oral Mucosa - Cutis

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

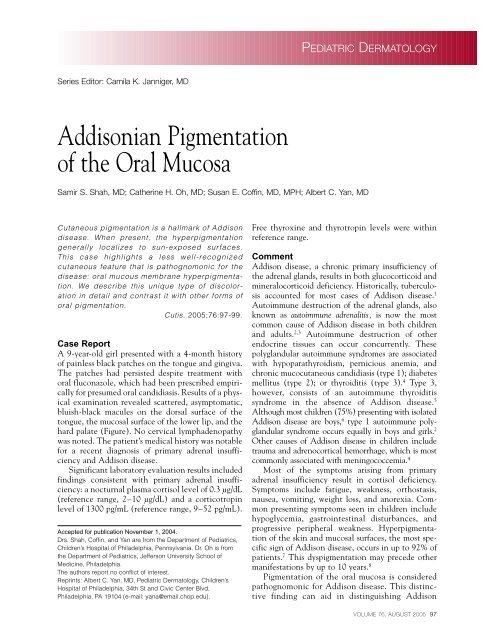

PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGYSeries Editor: Camila K. Janniger, MD<strong>Addisonian</strong> <strong>Pigmentation</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Oral</strong> <strong>Mucosa</strong>Samir S. Shah, MD; Ca<strong>the</strong>rine H. Oh, MD; Susan E. C<strong>of</strong>fin, MD, MPH; Albert C. Yan, MDCutaneous pigmentation is a hallmark <strong>of</strong> Addisondisease. When present, <strong>the</strong> hyperpigmentationgenerally localizes to sun-exposed surfaces.This case highlights a less well-recognizedcutaneous feature that is pathognomonic for <strong>the</strong>disease: oral mucous membrane hyperpigmentation.We describe this unique type <strong>of</strong> discolorationin detail and contrast it with o<strong>the</strong>r forms <strong>of</strong>oral pigmentation.<strong>Cutis</strong>. 2005;76:97-99.Case ReportA 9-year-old girl presented with a 4-month history<strong>of</strong> painless black patches on <strong>the</strong> tongue and gingiva.The patches had persisted despite treatment withoral fluconazole, which had been prescribed empiricallyfor presumed oral candidiasis. Results <strong>of</strong> a physicalexamination revealed scattered, asymptomatic,bluish-black macules on <strong>the</strong> dorsal surface <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>tongue, <strong>the</strong> mucosal surface <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lower lip, and <strong>the</strong>hard palate (Figure). No cervical lymphadenopathywas noted. The patient’s medical history was notablefor a recent diagnosis <strong>of</strong> primary adrenal insufficiencyand Addison disease.Significant laboratory evaluation results includedfindings consistent with primary adrenal insufficiency:a nocturnal plasma cortisol level <strong>of</strong> 0.3 µg/dL(reference range, 2–10 µg/dL) and a corticotropinlevel <strong>of</strong> 1300 pg/mL (reference range, 9–52 pg/mL).Accepted for publication November 1, 2004.Drs. Shah, C<strong>of</strong>fin, and Yan are from <strong>the</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Pediatrics,Children’s Hospital <strong>of</strong> Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dr. Oh is from<strong>the</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Pediatrics, Jefferson University School <strong>of</strong>Medicine, Philadelphia.The authors report no conflict <strong>of</strong> interest.Reprints: Albert C. Yan, MD, Pediatric Dermatology, Children’sHospital <strong>of</strong> Philadelphia, 34th St and Civic Center Blvd,Philadelphia, PA 19104 (e-mail: yana@email.chop.edu).Free thyroxine and thyrotropin levels were withinreference range.CommentAddison disease, a chronic primary insufficiency <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> adrenal glands, results in both glucocorticoid andmineralocorticoid deficiency. Historically, tuberculosisaccounted for most cases <strong>of</strong> Addison disease. 1Autoimmune destruction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> adrenal glands, alsoknown as autoimmune adrenalitis, is now <strong>the</strong> mostcommon cause <strong>of</strong> Addison disease in both childrenand adults. 2,3 Autoimmune destruction <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rendocrine tissues can occur concurrently. Thesepolyglandular autoimmune syndromes are associatedwith hypoparathyroidism, pernicious anemia, andchronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (type 1); diabetesmellitus (type 2); or thyroiditis (type 3). 4 Type 3,however, consists <strong>of</strong> an autoimmune thyroiditissyndrome in <strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> Addison disease. 5Although most children (75%) presenting with isolatedAddison disease are boys, 6 type 1 autoimmune polyglandularsyndrome occurs equally in boys and girls. 2O<strong>the</strong>r causes <strong>of</strong> Addison disease in children includetrauma and adrenocortical hemorrhage, which is mostcommonly associated with meningococcemia. 4Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> symptoms arising from primaryadrenal insufficiency result in cortisol deficiency.Symptoms include fatigue, weakness, orthostasis,nausea, vomiting, weight loss, and anorexia. Commonpresenting symptoms seen in children includehypoglycemia, gastrointestinal disturbances, andprogressive peripheral weakness. Hyperpigmentation<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> skin and mucosal surfaces, <strong>the</strong> most specificsign <strong>of</strong> Addison disease, occurs in up to 92% <strong>of</strong>patients. 7 This dyspigmentation may precede o<strong>the</strong>rmanifestations by up to 10 years. 8<strong>Pigmentation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> oral mucosa is consideredpathognomonic for Addison disease. This distinctivefinding can aid in distinguishing AddisonVOLUME 76, AUGUST 2005 97

Pediatric Dermatologydisease from o<strong>the</strong>r endocrinopathiesthat also may presentwith hyperpigmentation, such ashyperthyroidism. 9 The oral hyperpigmentedmacules <strong>of</strong> Addisondisease can be found diffusely on<strong>the</strong> tongue, gingiva, buccalmucosa, and hard palate. Themacules tend to be blue-black orbrown and can be spotty orstreaked in configuration. Thepattern <strong>of</strong> pigmentation is usuallypatchy and can occasionally alternatewith leukodermic patterns.The hyperpigmentation <strong>of</strong>Addison disease tends to producea generalized bronze appearancethat is more easily detectable infair-skinned children. In darkskinnedchildren, a similar increasein color may be mistaken for atan. Hyperpigmentation occursmost prominently at <strong>the</strong> flexures,sites <strong>of</strong> pressure and friction,palmar and plantar creases, andsun-exposed areas. It also mayresult in intensification <strong>of</strong> normallypigmented areas such as <strong>the</strong>genitalia and areolae mammae. 6Scars also can exhibit hyperpigmentation,which only appears inscars acquired after <strong>the</strong> onset <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> disease. Coexistence <strong>of</strong> pigmentedand uncolored scars mayaid in <strong>the</strong> precise dating <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>destructive process found in <strong>the</strong>adrenals. 8 Paradoxically, vitiligoalso may be seen in patients withAddison disease and may occurconcurrently with hyperpigmentation.<strong>Pigmentation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> vaginalmucosae and conjunctivaealso are frequently observed inaffected patients. 1Hyperpigmentation associatedwith Addison disease presumably occurs secondaryto overproduction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pro-opiomelanocortinbyproduct -lipotropin, which is secreted in excessamounts concomitantly with corticotrophin from<strong>the</strong> pituitary gland because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> feedbackinhibition seen in adrenal insufficiency states. 10O<strong>the</strong>r conditions that lead to increased corticotropinproduction also may present with similarcutaneous hyperpigmentation, as seen in adrenoleukodystrophy(Siemerling-Creutzfeldt disease), 11<strong>Pigmentation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tongue (A) and lower lip (B) in Addison disease.familial adrenocorticotropin unresponsiveness syndrome(familial glucocorticoid deficiency), 12 thymiccarcinoids, 13 and paraneoplastic corticotropin productionin <strong>the</strong> setting <strong>of</strong> underlying malignancy 14 ;however, oral pigmentation has not been specificallyreported in <strong>the</strong>se cases.Adequate hormone replacement <strong>the</strong>rapy typicallyresults in a decrease in <strong>the</strong> degree <strong>of</strong> cutaneouspigmentation, though oral pigmentation persistsindefinitely. 15 In this particular case, <strong>the</strong> patient’sAB98 CUTIS ®

Pediatric Dermatologyoral pigmentation did show modest improvementwith good hormonal control; however, when <strong>the</strong>patient was noncompliant with hormonal <strong>the</strong>rapy,her pigmentation worsened clinically. In someaffected younger children, <strong>the</strong> skin color may eventuallyreturn to normal with <strong>the</strong>rapy.Differential DiagnosisDiagnoses that may mimic <strong>the</strong> oral pigmentation<strong>of</strong> Addison disease include: oral “black tongue”candidiasis, ethnic pigmentation, and reactions tocertain drugs. Black hairy tongue and black tonguecandidiasis are disorders believed to be caused byCandida albicans and occasionally Aspergillusspecies. These conditions are associated with longtermuse <strong>of</strong> antibiotics. Characterized by dense,black, bluish-black, or brown “matted” areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>dorsal surface <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tongue, black tongue candidiasiscan be successfully eliminated by discontinuationor minimization <strong>of</strong> antibiotics, gentlebrushing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tongue surface, and use <strong>of</strong> an oralantifungal agent. 16The most common pattern <strong>of</strong> ethnic or racial pigmentationis a band <strong>of</strong> pigment at <strong>the</strong> junction <strong>of</strong>attached and alveolar mucosa. In contrast to Addisondisease, pigmentation on <strong>the</strong> tongue <strong>of</strong> those with skin<strong>of</strong> color is typically localized to <strong>the</strong> tips <strong>of</strong> isolated groups<strong>of</strong> filiform papillae. 17 Such pigmentation, usually foundonly in persons with dark skin, also can be found asisolated pigmented patches in 5% <strong>of</strong> Caucasians.Drug-induced pigmentation can range frombrown (seen with oral contraceptives, cytotoxicagents, and some anticonvulsants) to yellow orblue-black (as seen with <strong>the</strong> antimalarial drugsquinacrine, chloroquine, and hydroxychloroquine).18 Long-term use <strong>of</strong> minocycline has beenassociated with a blue-gray staining <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tongue,gingival margins, palate, and pretibial surfaces.Patchy blue-black hyperpigmentation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> oralmucosa should cause suspicion <strong>of</strong> Addison disease,particularly if appropriate systemic signs are notedand if no o<strong>the</strong>r explanatory factors, such as concomitantcandidiasis, ethnic background, or drugs,are associated.REFERENCES1. Dunlop D. Eighty-six cases <strong>of</strong> Addison disease. BMJ.1963;3:887-891.2. Soderbergh A, Winqvist O, Norheim I, et al. Adrenalautoantibodies and organ-specific autoimmunity in patientswith Addison disease. Clin Endocrinol. 1996;45:453-460.3. Myhre AG, Undlien DE, Løvås K, et al. Autoimmuneadrenocortical failure in Norway. autoantibodies andhuman leukocyte antigen class II associations relatedto clinical features. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.2002;87:618-623.4. Baker JR Jr. Autoimmune endocrine disease. JAMA.1997;278:1931-1937.5. Spinner MW, Blizzard RM, Childs B. Clinical andgenetic heterogeneity in idiopathic Addison’s diseaseand hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.1968;28:795-804.6. Oelkers W. Current concepts: adrenal insufficiency. N EnglJ Med. 1996;335:1206-1212.7. Hurwitz S. Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook <strong>of</strong>Skin Disorders <strong>of</strong> Childhood and Adolescence. 2nd ed.Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1993.8. Forest MG. Adrenal steroid deficiency states. In:Brook CGD, ed. Clinical Paediatric Endocrinology. 3rded. Cambridge, England: Blackwell Science;1995:453-498.9. Banba K, Tanaka N, Fujioka A, et al. Hyperpigmentationcaused by hyperthyroidism: differences from <strong>the</strong> pigmentation<strong>of</strong> Addison disease. Clin Exp Dermatol.1999;24:196-198.10. Wiebke A, Allolio B. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet.2003;361:1881-1893.11. Ropers HH, Burmeister P, Petrykowski W, et al.Leukodystrophy, skin hyperpigmentation, and adrenalatrophy: Siemerling-Creutzfeldt disease. transmissionthrough several generations in two families. Am J HumGenet. 1975;27:547-553.12. Berberoglu M, Aycan Z, Ocal G, et al. Syndrome <strong>of</strong> congenitaladrenocortical unresponsiveness to ACTH.report <strong>of</strong> six patients. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab.2001;14:1113-1118.13. Gartner LA, Voorhess ML. Adrenocorticotrophic hormoneproducingthymic carcinoid in a teenager. Cancer.1993;71:106-111.14. Makita M, Maeda Y, Hashimoto K, et al. Acute lymphoblasticleukemia with large molecular ACTH production.Ann Hematol. 2003;82:448-551.15. Dummett CO. Systemic significance <strong>of</strong> oral pigmentationand discoloration. Postgrad Med. 1971;49:78-82.16. Wolf IJ. Black tongue moniliasis. Pediatrics. 1970;46:975.17. Leston JM, Santos AA, Varela-Centelles PI, et al. <strong>Oral</strong>mucosa: variations from normalcy, part II. <strong>Cutis</strong>.2002;69:215-217.18. Kleinegger CL, Hammond HL, Finkelstein MW. <strong>Oral</strong>mucosal hyperpigmentation secondary to antimalarialdrug <strong>the</strong>rapy. <strong>Oral</strong> Surg <strong>Oral</strong> Med <strong>Oral</strong> Pathol <strong>Oral</strong> RadiolEndod. 2000;90:189-194.VOLUME 76, AUGUST 2005 99