Valour does not wait - Battle of Prestonpans 1745

Valour does not wait - Battle of Prestonpans 1745

Valour does not wait - Battle of Prestonpans 1745

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Valour</strong> <strong>does</strong> <strong>not</strong> <strong>wait</strong>THE RISE AND FALL OF CHARLES EDWARD STUARTARRAN JOHNSTON

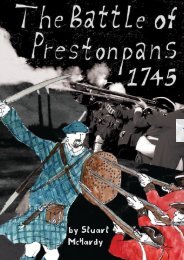

<strong>Valour</strong> <strong>does</strong> <strong>not</strong> <strong>wait</strong>“In great Princes whom nature has marked out for heroes,valour <strong>does</strong> <strong>not</strong> <strong>wait</strong> for number <strong>of</strong> years.”In December 1720 a great storm devastated the state <strong>of</strong> Hanover,announcing <strong>of</strong> the birth <strong>of</strong> the military leader who would sweepaway the injustices <strong>of</strong> Hanoverian rule in Great Britain andIreland. That leader was Charles Edward Stuart. Born in exile, theyoung Charles spent his childhood in Italy <strong>wait</strong>ing to be calledupon by destiny. He was the last hope <strong>of</strong> restoring the Stuarts tothe throne.Before he was 25, Charles would shake the British establishmentto its very foundations, forcing all <strong>of</strong> Europe to take <strong>not</strong>ice. By thetime he died at 68, he was a forgotten political relic and a touristcuriosity.This new book delves deep into the Prince’s mind, seeking toexpose the motivations and talents <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> the 18th Century’smost extraordinary political figures. What persuaded a 24 year oldexile that he could overthrow the British government? Why didhard-headed strangers risk all that they had for him and his cause?How did he conquer armies and capture cities with almost nomilitary experience? And then where did it all go wrong?Born from the author’s personal fascination with this exceptionalcharacter and his knowledge <strong>of</strong> the areas through which hecampaigned, this new study explores how the <strong>1745</strong> Rising allowedthe Prince to show <strong>of</strong>f his greatest abilities, and how it affected hisstate <strong>of</strong> mind so deeply that it haunted the rest <strong>of</strong> his life.This is the story <strong>of</strong> a young man’s extraordinary achievements, <strong>of</strong>his hopes and ambitions, failures and torments. It is the story <strong>of</strong>the real Bonnie Prince Charlie, and the mission which first made,and then destroyed him..

<strong>Valour</strong> <strong>does</strong> <strong>not</strong> <strong>wait</strong>

<strong>Valour</strong> <strong>does</strong><strong>not</strong> <strong>wait</strong>The Rise and Fall <strong>of</strong> Charles Edward StuartArran Paul JohnstonPublished by Prestoungrange University Press in associationwith Burke’s Peerage & Gentry

First Published 2010Copyright © 2010 <strong>Battle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Prestonpans</strong> (<strong>1745</strong>) Heritage TrustAll rights reserved. Copyright under international and Pan-American CopyrightConventions.No part <strong>of</strong> this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system ortransmitted in any other form or by any other means, electronic, mechanical,photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission <strong>of</strong> thepublisher and copyright holder. Within the UK, exceptions are allowed inrespect <strong>of</strong> any fair dealing for the purpose <strong>of</strong> research or private study, orcriticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act,1988.While the publisher makes every effort possible to publish full and correctinformation in this book, sometimes errors <strong>of</strong> omission or substance may occur.For this the publisher is most regretful, but hereby must disclaim any liability.ISBN 978-0-85011-124-8The portrait <strong>of</strong> Prince Charles Edward on the front cover was painted byKate Hunter for the <strong>Battle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Prestonpans</strong> <strong>1745</strong> Heritage Trust following thecontroversy over La Tour’s portrait now belived to be <strong>of</strong> Charles’s brotherHenry.Prestoungrange University Press with Burke’s Peerage & Gentry forThe <strong>Battle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Prestonpans</strong> <strong>1745</strong> Heritage Trust227/229 High Street, <strong>Prestonpans</strong>East Lothian, Scotland EH32 9BEDesign & Typesetting by Chat Noir Design, FrancePrinted & bound in Great Britain

ContentsAuthor’s Introduction 7Aeneas 16The Politician 41The Fall <strong>of</strong> Edinburgh 60The Soldier 79Victory at <strong>Prestonpans</strong> 96Living with Murray 112Defeat at Culloden 140The Fugitive Prince 159King Charles III 186Appendix I 197Appendix II 201Appendix III 205Appendix IV 210Bibliography 2135

Author’s IntroductionWhen I was about ten years old, growing up in southernDerbyshire, my parents turned their thoughts to my secondaryeducation. At that point, I was studying in the dark Victoriancharm <strong>of</strong> Friar Gate House, a fine Georgian town house in thecentre <strong>of</strong> Derby, and although it was a small, <strong>of</strong>ten bemusingschool, I’ve been known to credit it with the responsibility forsome <strong>of</strong> my better traits. Nevertheless, it was time to move.Little did I know it then, but just a short distance walk fromthe school yard, two hundred and fifty years before had stood thebaggage <strong>of</strong> an invading army.After exploring a number <strong>of</strong> options, I set out to gain a placeat Derby Grammar School, based in the rather more rural setting<strong>of</strong> Rykneld Hall. Although the hall was old, the school was new,and that gamble made the experience all the more exciting forme, if <strong>not</strong> my parents. In truth, however, the school claimedrightful descent from its proud predecessor, Derby School, andwas formed with the support and passion <strong>of</strong> those Old Derbeianswho still mourned the loss <strong>of</strong> their school in 1989. Rykneld’spanelled halls were therefore filled with memorabilia <strong>of</strong> theancient grammar, its former pupils, and its impressive heritage.On the wall there hung a sketch <strong>of</strong> an old Tudor schoolhouse onSt Peter’s Street in Derby, a building I <strong>of</strong>ten passed in the city butrarely <strong>not</strong>iced.Little did I know, two hundred and fifty years before, thoseschoolrooms had been filled with the exhausted bodies <strong>of</strong>sleeping clansmen.To win a place at the school, I needed to perform well in theentrance papers, and my parents were keen to <strong>of</strong>fer me everyadvantage. They dutifully prepared exercises for me to practice at,and one night they sat me down at the dining room table andinstructed me to compose a short story. I sat in the quiet room,in our house in Swanwick, and scribbled away in the spidery7

VALOUR DOES NOT WAITscrawl that I would later strive to restrain. It has made a surprisereturn this year, in fact. The details <strong>of</strong> the story have long slippedmy mind and memory, but I recall the general gist, with theamusement <strong>of</strong> hindsight. I wrote with the voice <strong>of</strong> a young Derbylad, <strong>not</strong> unlike myself, who struck up a friendship with amysterious stranger staying in the town. No doubt the boy wasconfused by the activity in the city, and the unusual behaviour <strong>of</strong>the adults around him. But when the time came for the strangerto depart, he left behind him a letter, addressed to the boy. Uponopening it, the young Derbeian saw to his amazement that it wassigned in a bold hand: Bonnie Prince Charlie. Somehow, and Iknow <strong>not</strong> how, this man and his name had entered into mypsyche. It is my first memory <strong>of</strong> him.Little did I know it then, but he would become one <strong>of</strong> themost important people in my life.I took up my place at Derby Grammar with the usual prideand cockiness that comes with a new uniform and a Latin motto.Year on year, my interest in the events <strong>of</strong> <strong>1745</strong> grew anddeveloped, and in a school proud <strong>of</strong> its links to a fine city, therewas plenty <strong>of</strong> opportunity to indulge such interests. I rememberschool projects evaluating the strategic importance <strong>of</strong> the Trentbridge at Swarkestone, trips to that old Tudor schoolhouse –then, appropriately, a local heritage centre, although morerecently a hairdressers. It was on one such school trip that I wasintroduced, by the Richard Felix who would shortly becomefamous for his videos on the paranormal, to members <strong>of</strong> theCharles Edward Stuart Society, a motley crew <strong>of</strong> battle re-enactorswho paraded in the town each year. Although far too young t<strong>of</strong>ight in their battles, I joined them with enthusiasm. AtAvoncr<strong>of</strong>t Museum one summer, I donned the ill-fitting uniform<strong>of</strong> the Royal Eccossais, and began what has already been a longand varied life in the world <strong>of</strong> re-enactment. Proudly, I portrayedan English volunteer in the Jacobite army, before becoming anartilleryman on our infamous non-firing cannon. Then, early inthe new millennium, I made something <strong>of</strong> a leap: I was asked to8

A UTHOR’ S I NTRODUCTIONtake on the role <strong>of</strong> Charles Edward Stuart for the society and itsevents.Shortly after this, in the summer <strong>of</strong> 2003, I left the GrammarSchool and headed north, drawn by an irresistible force to therocky capital <strong>of</strong> Scotland. My time at the University <strong>of</strong>Edinburgh was immensely fulfilling, and although I was studyingthe politics and literature <strong>of</strong> ancient Rome, I felt myselfbroadening in outlook. Exposed to the charms <strong>of</strong> a magnificentland I had never encountered beyond the stories I had read <strong>of</strong> the‘45, I soaked in as much <strong>of</strong> Scotland as possible, and I soon hadthree sweetie jars, containing the mud <strong>of</strong> <strong>Prestonpans</strong>, Falkirk,and Culloden. Although I had a passion for my Latin, my mindand my work have ever since brought me back to the ’45.And it brought me here, to the day I decided to write aboutthe man I had first written about in the dining room atSwanwick. Most people have heard <strong>of</strong> Charles Edward, but fewaccounts <strong>of</strong> his life are consistent. There seem to have been manyCharles Edwards, ranging from the dashing tartan hero <strong>of</strong> theshortbread tin, to the effeminate coward <strong>of</strong> comedians and satire.The reality is, <strong>of</strong> course, that the mists <strong>of</strong> time and the ferventpassions <strong>of</strong> partisans have clouded the truth and hidden this manfrom our eyes. As a character-actor as well as an historian, I havestriven to push those clouds aside, and I believe that I can nowsee that man.For many years now, I have been presenting Charles EdwardStuart to all kinds <strong>of</strong> audiences. Through me, he has visitedschools, historical societies, social clubs, and museums. I haveused charm and smiles, as Charles would have done, and I haveranted and raged as he would too. Like Charles, I haveexperienced both successes and failures. I have raised my standardby Loch Shiel, been piped into Holyrood Palace, and havedeclared King James at the Mercat Cross in Edinburgh. I havebroken Cope’s lines at <strong>Prestonpans</strong>, and marched on foot intoDerby. Likewise, I have been dragged away from faltering battlelines, sensed the shame <strong>of</strong> defeat, and have pressed my rough9

VALOUR DOES NOT WAITtartan into the bracken, deep inside unwelcoming caves. Toexperience life in the lines, I have also dared the desperate chargeat Culloden, through biting sleet and winds, faced the charge <strong>of</strong>Hawley’s dragoons, worked cannons, and fallen to bayonets. Theresult is that I believe I know Charles Edward Stuart – confidentand brave, broken and unfulfilled – in all his moods and hismanifestations. I want others to know him also.It is difficult to explain the very personal nature <strong>of</strong> this study,and its importance to me. It is perhaps best expressed througha<strong>not</strong>her short story. It was late in 2007, and I was fresh fromuniversity and eager to find my place in a formidable world. Iworked in the museum in Derby, living with my parents in thehome we had moved into when I had left Friar Gate. I wasunsettled, itchy, and uncertain. Plotting, I took a week <strong>of</strong>f work,and went to see a friend in York – a<strong>not</strong>her Old Derbeian. I wassupposedly spending half the week in York and half in Fife. Butbetween the two, in the greatest secrecy, I headed deep into thewestern highlands. On the one hand, I was researching for aproject which would become my first book, Rebellious Scots toCrush. In reality, however, I was really looking for advice, orrather inspiration. I struck out from a base in North Ballachulish,walking alone in Glencoe and Glenfinnan, chasing the Jacobitesas usual.Eventually, I pulled <strong>of</strong>f the road alongside Loch nan Uamh –an unexpected manoeuvre, occasioned by a tiny roadside <strong>not</strong>icefor the Prince’s Cairn. Like countless others before me, I droppeddown the almost hidden path, to the spot from which Charlesleft Scotland forever. I scrambled over the rocks beyond, anddown to the waterfront. I washed my hands and face in the clearcold water, and sat on the ragged outcrop. The water seemed still;the silence was natural and soothing. As I sat and pondered myfuture, I spoke aloud. Beyond the barrier <strong>of</strong> centuries long past, Isought the advice <strong>of</strong> a<strong>not</strong>her man who had stood just here andwondered what his future would bring. Charles Edward made noanswer, but he did make my decision. I have lived in Scotland10

A UTHOR’ S I NTRODUCTIONever since, having moved to Edinburgh with neither work norlodgings, to throw myself on the mercy its people. This is when Irealised that Charles Edward Stuart is <strong>not</strong> to be found in thearchives <strong>of</strong> Windsor or the libraries <strong>of</strong> Scotland, but here on theground. He lives on in the land which he so trusted, which sowell protected him, and where, in the hardest times and againstall the odds, he felt at home for that one brief period in his longand deeply troubled life.This is my most ambitious project to date, and although it is <strong>of</strong>great personal importance to me, I am a classicist by training andso I have attempted to make my work thorough and my methodsrigorous. What is presented, therefore, should be valued as areliable conclusion based upon a wide spectrum <strong>of</strong> primary andsecondary reading, a careful balance <strong>of</strong> authorial bias and motive,and the fluid nature <strong>of</strong> historiography.There is certainly no shortage <strong>of</strong> material covering the ’45, noris there a lack <strong>of</strong> biographies <strong>of</strong> Prince Charles. My intention is toprovide something a little different to what is already accessible. Ihave pored over a great many statements and opinions regardingthe Rising and its leader, and identified what I believe bestsummarises Charles’ complex personality. I am deeply indebtedto the work <strong>of</strong> many far more eminent scholars than myself, all <strong>of</strong>whom have contributed to my passion for the study even whenthey haven’t gained a formal reference here. Hopefully, thismodest effort will be able to contribute something to theunderstanding <strong>of</strong> the Rising even if it will never be asimmeasurably useful as a copy <strong>of</strong> Duffy’s The ’45, amongstothers.It is important to acknowledge that finding the real CharlesEdward is no easy task. The primary sources are exceptionallypartisan, and even within Jacobite texts there are wildlycontrasting versions <strong>of</strong> the same events. An easy example to11

A UTHOR’ S I NTRODUCTIONAs a re-enactor, I have experienced life in the first century, theseventeenth, and the eighteenth, as a rich man and a poor man, asoldier and a statesman. From shouting orders on a drill square,or repelling cavalry attacks to boarding tall ships or haulingcannon across battlefields, I am fortunate to have gained firsthandexperience <strong>of</strong> many <strong>of</strong> the hardships the Prince would alsohave been exposed to. Through the work I’ve been doing, I havebrought the Prince to audiences across Britain, from Borrodale toDerby, all the while developing a greater understanding andattachment to the personality I am assuming. There are alsomoments when I can<strong>not</strong> put Charles aside, like when his tempermade the chandeliers shake during a talk in the midlands, orwhen I sulked for a day after reading comments by Elcho. Mydear friend Adam Watters, <strong>of</strong> the Alan Breck Stewart VolunteerRegiment despairs that he has to restrain me from leading thecharge in person. Such is the power <strong>of</strong> this long deceased Prince.All those I have worked with, or who have helped me in mymodest quest, are gratefully thanked.I must also here thank the <strong>Battle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Prestonpans</strong> (<strong>1745</strong>)Heritage Trust, with whom I have worked extensively since anaccidental meeting with their chairman whilst walking on thebattlefield collecting my thoughts. I am a passionate supporter <strong>of</strong>their intention to improve interpretation <strong>of</strong> their battle, and havedone what I can to assist them. That work has ranged fromwriting exhibitions to helping arrange the now annual reenactmentsthere. In return, the Trust has helped me enjoy someunforgettable experiences, from occupying Holyroodhouse tocapturing Cope’s baggage at Cockenzie. They honoured me bycommissioning and publishing my first book, Rebellious Scots toCrush, which summarises the literary legacy <strong>of</strong> the battle at<strong>Prestonpans</strong>, and they introduced me to the author Steven Lordwith whom the Trustees and I recently spent a delightful week inthe Highlands. The gentle sparring we had in front <strong>of</strong> the fire atBorrodale House gave me an added impetus for continuing withthis current project, which had been in my mind for some time.13

VALOUR DOES NOT WAITThe Trust also introduced me to Martin Margulies, a<strong>not</strong>herwriter on the period, who also happens to share my attachmentto ancient Rome. Since then, many messages and debatesregarding the Rising have crossed the Atlantic, <strong>not</strong> always inagreement but always in good humour. Most recently, the battletrust at <strong>Prestonpans</strong> has done me further honour by making mean executive trustee, and it is by their kindness that I can nowwork from a desk which looks across the Forth, with a pieceGardiner’s thorn tree mounted on the wall beside me.Alongside my analysis <strong>of</strong> Charles’ performance in the ’45, Ihave included three ‘special’ chapters, covering the capture <strong>of</strong>Edinburgh and the battles <strong>of</strong> <strong>Prestonpans</strong> and Culloden. Thesechapters are intended to provide a contrast to the main body <strong>of</strong>the work, by <strong>of</strong>fering a vivid and enlightening view into these keyevents. I could have chosen others (most <strong>not</strong>ably, the battle <strong>of</strong>Falkirk is missing, and I originally also planned to exploreDerby), but I really wanted to use my intimate knowledge <strong>of</strong> thebattlefield context at <strong>Prestonpans</strong>, and my passion for the city <strong>of</strong>Edinburgh in which I live and work. Culloden is consideredbecause <strong>of</strong> its contrast to <strong>Prestonpans</strong>, and because it is importantto explore that battle more fully than this study would otherwisepermit. These chapters are written in a more narrative style, andshould express some <strong>of</strong> my passion for the period as well asmaking use <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> my experience on the re-enactmentbattlefield. Their major purpose is to provide a feeling for theatmosphere <strong>of</strong> the events which raised and broke both Charles’hopes and his spirits. Through seeing what he witnessed in detail,we can get a deeper understanding <strong>of</strong> the wider picture, and thusits effects on the participants.I have tried to analyse the Prince’s character from a distance,and impartially, but I am proud to say that I have probably failed.I have long believed that no history is unbiased, and no historianshould hope or pretend to be so. We must evaluate the evidence,decide what we believe, and then persuade others to believe italso. We are <strong>not</strong> therefore merely historians, but storytellers and14

A UTHOR’ S I NTRODUCTIONartists, and the advocates for those who can no longer reach us.As such, my presentation is undoubtedly as partisan as thememory <strong>of</strong> O’Sullivan or Murray. I am in no way blind to thefaults <strong>of</strong> the man I have spent so much time seeking, but I can seethem in the context <strong>of</strong> a human figure in a challenging world.Charles and I share one further similarity: when Charlescampaigned in Scotland, he was the same age as I am as I writethis study. It is an age <strong>of</strong> ambition and uncertainty, as I know aswell as any.The story <strong>of</strong> Charles Edward Stuart brings a tear to my eye atone moment, and fills me with fire the next. All said, I believe weshould share his journey, see into his mind, and emerge with anadmiration for an extraordinary individual, tinged with morethan a little sadness for his ultimate tragedy.15

AeneasIn 1734, the exiled Stuart king <strong>of</strong> Great Britain and OldChevalier, James III, sent his son on a mission to gain themilitary experience that would be needed if the boy was to oneday recover the family’s fortunes. It was the end <strong>of</strong> the boy’schildhood, and the beginning <strong>of</strong> a manhood that would propelhim into legend. The future King Carlos III <strong>of</strong> Spain wasbesieging a key Habsburg fortress between Rome and Naples,and Charles had joined them for the closing stages <strong>of</strong> theoperation. The town was Gaeta, known to the ancient Romans asCaieta:Yet more! Forever famed Caieta, by dying here,O nurse <strong>of</strong> Aeneas, on our shore you’ve left your name.Virgil, Aeneid, 7.1-2 1According to the ancient legend, Caieta was the nursemaid <strong>of</strong> theTrojan hero Aeneas. As the city <strong>of</strong> Troy burned behind him, thelast survivor <strong>of</strong> its royal house escaped by sea, and to a long exilein remote lands. Eventually, settling in central Italy, Aeneas andhis loyal followers fought a bloody war, overthrowing the rulingaristocracy and establishing a new royal dynasty. His bloodlineformed one <strong>of</strong> the greatest empires the world had ever seen: theRomans. Centuries later, the Roman emperor Augustus commissionedthe poet Virgil to compose an epic poem recalling thelegendary founding <strong>of</strong> their race. It was one <strong>of</strong> the finest works <strong>of</strong>Latin literature, composed in what was considered to be a goldenage. Indeed, the literary Aeneas was intended as a mirror <strong>of</strong>Augustus himself.In the eighteenth century, Aeneas became a metaphor once1 Translated from the Latin by the author.16

A ENEASagain. Somewhere, a people were dissatisfied. They longed for ahero, a man <strong>of</strong> royal blood who would sail across the seas from anenforced exile, and re-establish his house in a land he had neverseen. He would be young and inexperienced, counselled by a wisefather, supported by strong and loyal men. He would overcomeall obstacles and all odds, and his restoration would begin a newgolden age. These were the expectations which Charles EdwardStuart grew up with, and which he would strive to fulfil.Although few may have <strong>not</strong>iced the coincidence that Charles cuthis teeth at the siege <strong>of</strong> Caieta, named for the woman whonurtured Aeneas, people certainly compared the two heroes.Nor could the s<strong>of</strong>t seducing charms,Of mild Hesperia’s blooming soil,E’er quench his noble thirst <strong>of</strong> arms,Of generous deeds and honest toil.Hamilton <strong>of</strong> Bangour, Ode to GladsmuirHamilton’s Ode is perhaps the finest Jacobite poem in English,written in the wake <strong>of</strong> Charles’ first battlefield victory. The clearlyclassical style, the reference to Hesperia – the ancient name forItaly – and the association <strong>of</strong> highland soldiers with rusticshepherds, all make a link with Latin literature <strong>of</strong> the golden age .It was a common theme in Jacobite propaganda before, during,and after the ’45, but it was also a lot for a young man to live upto. Charles Edward, however, knew what was being expected <strong>of</strong>him. He was acutely conscious <strong>of</strong> his exile, and felt the weight <strong>of</strong>the responsibility he was destined to bear. At the same time, heknew it was neither he nor his father that was to blame for theirunhappy state. A letter sent from Perth in September <strong>1745</strong>reveals the depth <strong>of</strong> his understanding, and the level to which theStuarts were at the mercy <strong>of</strong> their own history:17

VALOUR DOES NOT WAITThey will no doubt endeavour to revive all the errors andexcesses <strong>of</strong> my grandfather’s unhappy reign, 2 and impute themto your Majesty and me, who had no hand in them, andsuffered most by them... What have these princes to answer for,who by their cruelties have raised enemies <strong>not</strong> only tothemselves but to their innocent children?Charles Edward StuartThe new Aeneas was the son <strong>of</strong> King James III <strong>of</strong> Great Britain &VIII <strong>of</strong> Scotland, the Old Pretender to his enemies, and was bornto him in Rome at the end <strong>of</strong> 1720. The war which would makehim famous was the final act in a conflict that began over ahundred years before it. Charles knew the story intimately, as didthose who would sit before their fires in Britain as they searchedtheir souls to decide whether to support him. Their decisions were<strong>of</strong>ten as rooted in the previous century as in the present, and sothat context needs consideration here, however brief it must be.Long before the birth <strong>of</strong> the legendary Bonnie Prince Charlie,a<strong>not</strong>her Charles – King Charles I – had been born in the ancientroyal palace <strong>of</strong> Dunfermline, austere and dislocated from power,and a relic <strong>of</strong> a former world. Charles was soon moved toLondon, where his complex and fascinating father was learningto control two kingdoms from one city. Charles was anunfortunate child, apparently unhappy and largely overlookedbefore the death <strong>of</strong> his elder brother; he grew up to be introvertedand formal, devout and sincere. King James I & VI had sufferedan even more troubled youth, but it had given him one bigadvantage over his son and successor: he had learned the mind <strong>of</strong>the Scots. Charles, too young and overshadowed to have takenmuch in at Dunfermline, had avoided returning to his secondkingdom until his coronation as King <strong>of</strong> Scots in 1633. 3 Thestrict formality <strong>of</strong> his English court and the king’s alo<strong>of</strong> personal2 King James II <strong>of</strong> Great Britain & VII <strong>of</strong> Scots (1633-1701).3 He had been crowned in Westminster in 1626, but delayed his Scottishceremony.18

A ENEASpresentation were at odds with the forthright approach <strong>of</strong>traditional Scots politics. In return to the <strong>of</strong>fence many Scotsnobles took from his attitude, Charles I left Edinburgh believinghis northern lands to be rude and uncouth. The distance theseand similar misunderstandings placed between the king and hisScots subjects weighed heavily against him when the politicsbecame rough.In the end, manners mattered little when it came to religion.The king’s attempt to introduce a new liturgy, as part <strong>of</strong> anoverall policy <strong>of</strong> anglicising the Scots church, changed Britainforever. Although it was composed by Scots, under advice fromthe controversial Archbishop Laud <strong>of</strong> Canterbury, the PrayerBook was fundamentally at odds with the Presbyterian practice <strong>of</strong>the kirk, which in turn clashed with the king’s desire for aformalised, standardised and unified Protestant church in Britain.Upon its first reading in St Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh went wildand the National Covenant was composed. The ensuing chaosled to the complete collapse <strong>of</strong> the king’s authority in Scotland,and soon there was a Scots army invading England – technicallyto rescue the king from his wicked advisors. Recalling Parliamentto authorise funding for the war, Charles unhappily unleashed abacklash against his long rule without consultation to that body,which culminated in the outbreak <strong>of</strong> civil war in England in1642. The Scots Covenanters, finding common ground with thepuritans in the London Parliament, and led on by promises <strong>of</strong> aPresbyterian church in England, turned the tide <strong>of</strong> the wardecisively against the king.Scotland suffered heavily during this period. The Marquess <strong>of</strong>Montrose, James Graham, led a lightning campaign across thehighlands in 1644-5 and scored a string <strong>of</strong> major victories in theking’s name. Clad in tartan trews and highland dress, the militarymarquess struck an image <strong>not</strong> a million miles distant to a figureto follow him a hundred years later. The Covenanter armyfighting in England was weakened to save the government inEdinburgh, and Montrose was finally defeated. His war, however,19

VALOUR DOES NOT WAIThad been waged without mercy on both sides, and the cost to thenation was immense. The king’s cause collapsed in England andhe surrendered to the Scots army, but he steadfastly refused toamend his religious views and was handed to theParliamentarians. Many Scots now rediscovered their attachmentto their ancient royal house, and the King’s treatment frustratedthem. Eventually, as it became clear that there would never be anextension <strong>of</strong> Presbyterianism to England, a Royalist factiongained the upper hand in Scottish politics and an Engagementwas agreed with Charles. A Scots army under the inadequateDuke <strong>of</strong> Hamilton marched south to rescue the king from hisenemies. The Engagers were, however, hopelessly defeated atPreston in 1648. 4 Within a year, King Charles was put on trialfor treason and sentenced to death, without the Scots even beingconsulted. On January 30th 1649, a date ever after to be dreadedby Stuarts, the anointed king was killed. Execution, assassination,murder, martyrdom: all terms which have been used to describeone <strong>of</strong> the darkest and most influential events in British history.Almost immediately, Charles II was declared King <strong>of</strong> Scotstwould <strong>not</strong> be until 1660 after years <strong>of</strong> war and exile, after aRoyalist invasion <strong>of</strong> England and a Commonwealth invasion <strong>of</strong>Scotland, that there was a reigning king again.The Restoration did <strong>not</strong> restore Scotland’s fortunes, nor patchup its relationship with the monarchy. Warfare had been virtuallyconstant since 1638, plague and famine never far from its heels,and the economy was as tattered as the political fabric <strong>of</strong> theland. Worse, the Presbyterian powers in the 1650s haddetermined to make the young Charles II more amenable – andPresbyterian – than his father. Whilst he had tolerated andendured their machinations and educations because it was hisonly hope <strong>of</strong> restoration, their efforts in every sense had failed.4 Preston was an unhappy place for Stuart supporters. They suffered defeatthere again in 1715, and in <strong>1745</strong> the Jacobites hesitated at crossing theriver which had seen so many <strong>of</strong> their ancestors defeated.20

A ENEASUltimately, it was the Commonwealth’s muscleman in Scotland,General Monck, who restored Charles to his subjects. Those whohad once attempted to force Charles’ hand now faced his anger,and the suppression <strong>of</strong> the Covenant was severe. The head <strong>of</strong> theMarquess <strong>of</strong> Argyll soon sat on the spike on which theCovenanters had placed Montrose’s.Having failed to produce a legitimate heir, Charles II passedthe throne to his capable but flawed brother James. HisCatholicism, and refusal to compromise on it, brought him intoconflict with the majority <strong>of</strong> his people. The killing timescontinued in Scotland, suppressing extremist Presbyterianism.Eventually, however, it was the fear that James II would educatehis son as a Catholic that drove the English Parliament to expelhim. War returned to Britain, although the battles <strong>of</strong>Killiecrankie and Dunkeld (1689) in Scotland and the Boyne(1690) in Ireland failed to return James to the crown. A newmonarchy was installed, safely Protestant and securely indebtedto Parliament for its power, and although James’ daughter Annereceived the crown in 1702, her Stuart family were overlooked atthe succession. The electors <strong>of</strong> Hanover were invited in (the newKing George I was married to Sophia, a granddaughter <strong>of</strong> James I<strong>of</strong> Great Britain).James II’s bloodline, meanwhile, continued in exile on thecontinent. His son, known to his supporters as James III & VIII,continued with his father’s Catholicism and eventually settled hiscourt in Rome. In 1715, he landed in Scotland in the hope <strong>of</strong>leading a Jacobite uprising to victory. Under the ineffectivecommand <strong>of</strong> the ‘Bobbing’ John Erskine, Earl <strong>of</strong> Mar, the ’15shuddered to failure at the inconclusive battle <strong>of</strong> Sheriffmuir, andJames returned to exile. Five years later, in a palace provided bythe Pope, James’ wife gave birth to Charles Edward.That Charles felt all this family history keenly is obvious. Thefortunes and fates <strong>of</strong> his ancestors affected his outlook and hispolitics. The lessons <strong>of</strong> his grandfather especially, but also hisfather, certainly influenced Charles’ attitude to religion, for21

VALOUR DOES NOT WAITexample. However, this consciousness also manifests itself in avery personal way. A small example is the fact that when inScotland, Charles carried a snuff box mounted with a silverportrait <strong>of</strong> King Charles I, the Royal Martyr. Perhaps it was fromfamily loyalty, perhaps from identification with a king who ledhis armies in battle with distinction and met death with coolnobility. Whatever the reason, it was obviously a point which wasknown to those around him, hence Elcho’s ominous observation:They [Charles’ advisors] were careful to remind him <strong>of</strong> their[the Scots’] bad behaviour towards King Charles First.Colonel David Wemyss, Lord Elcho 5Charles therefore clearly knew where he came from and, withtime working against the exiled court, how important it was thata trigger was found for action. Accordingly, the new Aeneaswould need training for war, and an education which wouldequip him for kingship.Unfortunately, the family, palace and world into whichCharles Edward was born created a bewildering and uncertainenvironment which would affect his character deeply. Charleswas born in the Palazzo Muti, granted to his father by PopeClement XI in 1719, on the Piazza dei Santi Apostoli in the heart<strong>of</strong> Rome, just paces from the ancient forum. After the death <strong>of</strong>his father, Charles would return here as the new King Across theWater. The family was loving, but unstable. James ran a busy andactive exiled court to and from which messages and informationtravelled the lengths <strong>of</strong> Europe. It is difficult to dislike James,who comes across as a kindly man with a noble countenance andan intelligent mind. Sadly, however, he could <strong>not</strong> compromise on5 Wemyss (2003): 114. The snipes are attributed to the Prince’s Irish advisorsin the period after Culloden. The snuff box referred to can be seen in BlairCastle, amongst a very fine collection <strong>of</strong> Jacobite relics. Unless otherwisestate, all quotations from this source are the words <strong>of</strong> Lord Elcho himself.22

A ENEAShis faith and this proved a fundamental barrier to his restorationplans. Worn down by constant disappointment, failure andbetrayal, Old Mr Melancholy was the cause’s intellectual headbut now lacked the dynamism and energy which was needed tocarry the Stuarts back to St James’ Palace. Nevertheless, he was adevoted father and cared deeply for his two boys, just as he felt aclear responsibility towards those who had sacrificed everythingfor his name and lived in exile alongside him.The court <strong>of</strong> the king was <strong>not</strong> a palace <strong>of</strong> happy families.James had secured a fine match in 1719 when he married, byproxy, the Polish princess Clementina Sobieski. Not only did shebring much needed wealth into the Muti, she was also attractive,young and charming, and capable <strong>of</strong> bearing the king sons.Importantly, she carried in her veins the martial blood <strong>of</strong> hergrandfather, John III Sobieski <strong>of</strong> Poland. John was a hero <strong>of</strong> theChristian world, who had led an allied army to spectacularvictory at Vienna in 1683 which crushed the hopes <strong>of</strong> theOttoman Empire. The mix <strong>of</strong> such blood with that <strong>of</strong> the Stuartswould surely stand Charles in good stead. Regrettably,Clementina’s Catholic faith was fanatical, whilst James kept herout <strong>of</strong> his state business. Although the couple clearly loved onea<strong>not</strong>her and both were faithful, the fragile peace <strong>of</strong> the courthabitually erupted with fiery arguments.Charles’ mother was a tragically fragile character, and shereacted to her isolation from her family and homeland as well asher exclusion from the king’s business, by throwing herself whollyat the Church. When Charles was born on New Year’s Eve 1720,there was a great crowd present in her chamber including largenumbers <strong>of</strong> cardinals. It was a deliberate act on James’ part: therewere once rumours he had been smuggled into his mother’s roomin a bedpan, and he wanted no such doubts to surround his ownson’s legitimacy. In this intimidating and intrusive atmosphere,perhaps Clementina took some comfort from the Pope’s arrival tobless the child, and the linen he sent to clothe him. The parentsargued over the Prince’s education, the staff employed to oversee23

VALOUR DOES NOT WAITit, and the queen’s role in the court. James was clearly the wiser ininsisting that Protestants were equally accessible to Charles asCatholics. With both parents being proud, stubborn anddepressive, tempers broke frequently and indiscreetly. Themarriage became a source <strong>of</strong> gossip and scandal, in whichClementina was more <strong>of</strong>ten seen as the victim than was fair.Furthermore, as she became known through Rome for herexceptional piety and saintly devotion to the Church, sheprovided valuable propaganda for the court in London. Worse, itwas destroying her body. She fasted, and much as the king triedto intervene Clementina’s health was visibly in decline. InJanuary 1735, at only thirty-two, Maria Clementina Sobieski wasburied in St Peter’s Basilica. Charles was deeply distressed by theevent, and the sense <strong>of</strong> loss can only have been magnified by themassive funeral event which moved all Rome. Although he hadnever been particularly close to his mother, the two were verysimilar in nature: he had her fire, charm, and temper, but also heremotional fragility and sense <strong>of</strong> isolation. Her obsession with theChurch warned Charles <strong>of</strong>f religion as much as his family historyhad, and her instability made him wary <strong>of</strong> relationships. All thisremained to be seen, as the boy <strong>of</strong> fifteen mourned the loss <strong>of</strong> amother the city had proclaimed a virtual saint.Despite the problems <strong>of</strong> his parent’s marriage, Charles’schildhood should be considered as unstable rather than unhappy.The arguments, the temper, the emotional insecurity andtendency to depression would all return to haunt him, but theywere <strong>not</strong> his entire world. There were tender moments too, withboth parents. The year before she died, Clementina took acarriage out to meet Charles as he returned from Gaeta, takingthe young Henry with her. We can only imagine the worry shehad endured in his absence. James was a loving father, callingCharles by the affectionate diminutive Carluccio, andendeavouring to advise his son long after the bitter failure <strong>of</strong> the‘45. It is easy to see a father’s pride in the exiled king’s reception<strong>of</strong> the young David Wemyss in 1740:24

A ENEASHe now rang a small bell and the princes came in from thenext room. I kissed hands and called them ‘Your Highness’, justas I had called their father ‘Your Majesty’. The Chevalier mademe stand back to back with the elder, Prince Charles, who wasa year older than I and much taller. 6Lord ElchoIn the strange environment <strong>of</strong> the Muti, Charles seems to havegrown up quickly. He was <strong>not</strong> an easy child to govern, with hisindependent spirit and his tantrums, but he quickly became thedarling <strong>of</strong> Roman society. Henry, five years his junior, was neverfar behind and the boys seem to have been close. The Londongovernment was keen from the moment <strong>of</strong> Charles’ birth tospread false reports <strong>of</strong> his incapacity and disabilities, but theevidence <strong>of</strong> those who encountered the boys gives a very clearimage <strong>of</strong> their steady progress.James tried to make sure that Italy stopped at the Muti door,and he wrote and spoke to the boys in English. WithEnglishmen, Irishmen, and Scotsmen around him all the time,Charles grew comfortable with British fashions and manners, aswell as the language. This is something which is <strong>of</strong>ten forgottenor unspoken, but it is important. It is certainly a mistake tobelieve that by growing up in Italy, Charles could <strong>not</strong> communicateeffectively whilst in Scotland, or that he seemedsomehow alien to his supporters. Nor was Charles stupid. WhenElcho reported that Charles, ‘was very ignorant <strong>of</strong> what washappening in the United Kingdom,’ he was considering theintimacies <strong>of</strong> social politics, with which Elcho was more intimate,having for a long time found himself with a foot in each camp.Charles could hardly have been familiar with life on the groundin Britain, but the Muti had extensive communications contacts.6 The warmth <strong>of</strong> the reception he received at the Muti whilst passingthrough on the grand tour drew Elcho irretrievably into Jacobite circles. Hewould, it seems, come to resent his youthful enthusiasm.25

VALOUR DOES NOT WAITThat said, Elcho was certainly <strong>not</strong> impressed with the Prince’seducation. He spent a winter in Rome in 1740, during which hewas well courted by the Jacobites, and he is a valuable witness:The Duke <strong>of</strong> York [Henry] has far better manners and is morepopular. Lord Dunbar is a man <strong>of</strong> the world and should havebeen able to give him [Charles] a better education, which he isaccused <strong>of</strong> neglecting; Sir Thomas Sheridan is an ardent Papistwith no knowledge <strong>of</strong> how England is governed, and who holdsthe l<strong>of</strong>tiest <strong>not</strong>ions about the divine right <strong>of</strong> kings and absolutepower.Lord ElchoIt is possible that Elcho’s recollections are being coloured by hislater animosity to Charles, or perhaps he was just misreadingwhat he saw. Dunbar (James Murray) was the Prince’s governor,and whilst the Catholic Sheridan was under-governor, the formerwas certainly Protestant, so we should <strong>not</strong> be misguided byElcho’s comment. Charles may very much have believed in thedivine nature <strong>of</strong> kingly authority, but the practical application <strong>of</strong>it that he promised in the ’45 <strong>does</strong> <strong>not</strong> comply with Elcho’sexpression here. If his brother was the more popular, then it iseasy to understand why Charles was so driven in his youth, andso eager to find his own independent identity. As for his ownpopularity popularity, Charles’s magnificent tour <strong>of</strong> northernItaly in 1737 was an immense success and the Prince’s charm,stamina, and comeliness drew unrivalled admiration. He may <strong>not</strong>have been an academic nor as bookish as his brother, but he hadclearly learned some winning ways.It is <strong>not</strong> denied that Charles neglected his studies, but that isto overlook, amongst other things, the fact that he wasconversing freely in English, French, and Italian. Nevertheless,his spelling would never greatly improve despite his father’s hopethat, ‘a little custom and application will soon make you write well,both for spelling and sense.’ This, however, is <strong>not</strong> unusual in the26

A ENEASeighteenth century, a time before standardisation <strong>of</strong> both spellingand grammar and when understanding was the only realrequirement <strong>of</strong> a communication. The Prince’s spelling comparesvery favourably to O’Sullivan’s, for example. The important pointis that Charles was <strong>not</strong> neglecting his studies out <strong>of</strong> idleness orlack <strong>of</strong> intelligence. He just had other concerns.The young Elcho remarked that, ‘Prince Charles did <strong>not</strong> havemuch to say to those who came to pay him court, and would spend allhis time shooting blackbirds and thrushes, or playing the Scottishgame <strong>of</strong> golf,’ and a<strong>not</strong>her eye-witness <strong>not</strong>iced that, ‘he had anovermastering passion for the pr<strong>of</strong>ession <strong>of</strong> arms.’ This, then, is whyCharles was <strong>not</strong> focussed on his books, and had no, ‘other interestsbut shooting and music’: he knew he was Aeneas. As Charles gotolder, he would spend more and more time out <strong>of</strong> the palazzo,and more time up in the hills around Rome. He was hunting,shooting, and training. He was toughening himself up, preparinghis body for the trials <strong>of</strong> a military campaign. He would leavebefore most <strong>of</strong> the household was awake, and when he returned,late in the night, he would relax by playing his cello or violin. Hewas soon known as a remarkable shot. His stamina was impressive:even when <strong>not</strong> out all day shooting, he would be paradingaround the dances, balls, and galas <strong>of</strong> society. The hours werelong, but these were routines he had been accustomed to from anearly age. There are, however, lessons that can<strong>not</strong> be learnedwhilst shooting thrushes. Thrushes, for example, don’t fire back.Charles needed formal military experience, and theopportunity came when he was just fourteen years old. The War<strong>of</strong> the Polish Succession had drawn international superpowersinto a Europe-wide contest, each eager to exploit the distractions<strong>of</strong> the other. In Italy, the Austrian controlled fortress <strong>of</strong> Gaeta wasunder siege by the army <strong>of</strong> Don Carlos <strong>of</strong> Spain. Joining theFranco-Spanish army was James Frances Fitz-James Stuart, Duke<strong>of</strong> Berwick, whose name exposes his descent from King James II.His father had just been killed fighting in the Rhineland, andKing James took the opportunity to send a message <strong>of</strong> comfort to27

VALOUR DOES NOT WAIThis relation, whilst giving Charles exactly the sort <strong>of</strong> experiencehe needed. Charles left Rome on 30th July 1734 for his first taste<strong>of</strong> war, and he relished it.Gaeta was an impressively fortified ancient town, lyingbetween Rome and Naples, and sited on a defensible promontory.It had seen many sieges before, and this would <strong>not</strong> be thelast. 7 The garrison, heavily outnumbered, had held out stubbornlyfor nearly four months, but the war had been lost andwon elsewhere and the siege’s outcome was in little doubt. It isimportant to consider the behaviour <strong>of</strong> the Prince during theseexperiences, and we are fortunate to have the reactions <strong>of</strong>Berwick himself to inform us. Charles, made an honorary general<strong>of</strong> artillery upon his arrival – which thankfully came with ahandsome wage – took his duties seriously. He worked in thetrenches which extended towards the walls, providing cover forthe soldiers preparing for an assault, and he showed courage andcool-headedness beyond the expectations <strong>of</strong> his age. On oneoccasion, a battery opened fire upon a farmhouse Berwick wasusing as a headquarters, and he was obliged to remove himself.Charles returned from the trenches and, in a no doubt deliberatedisplay <strong>of</strong> contempt for danger, insisted on returning into theshattered property:I must confess that he made me pass some uneasy moments...He showed <strong>not</strong> the least concern for the enemy’s fire, even whenthe balls were hissing about his ears... He stayed in it [thehouse] a very considerable time with an undisturbedcountenance, though the walls had been pierced through withthe cannon balls. In a word, this discovers that in great Princeswhom nature has marked out for heroes, valour <strong>does</strong> <strong>not</strong> <strong>wait</strong>for number <strong>of</strong> years.James Fitz-James Stuart, 2nd Duke <strong>of</strong> Berwick7 There is still an important military base in the town, alongside the residues<strong>of</strong> its former military significance.28

A ENEASThis letter alone should silence those who have, on occasion,doubted Charles’ personal bravery. It is an extraordinary tributeto a boy <strong>of</strong> fourteen, and is supported by the Prince’s behaviourthroughout his later military trials. Furthermore, Charles hadbeen actively learning from the siege, observing the conventions<strong>of</strong> eighteenth century warfare and soaking in anything that mightone day be <strong>of</strong> use to him in his greater mission. His conductbrought fresh admiration, and added to the frustration <strong>of</strong> theestablishment in London who were following his progress withapprehension.They were right to do so. Charles’ life was building towards itsgoal. He was preparing himself physically, had determinedly andsuccessfully set about seducing the courts <strong>of</strong> Italy, and he wasmaturing into a strong, single-minded Prince who knew thesignificance <strong>of</strong> his duty and the effort needed to succeed. AllCharles now wanted was the opportunity to strike. Would such achance ever come, when Britain was eager for change, at the samemoment that the European powers were keen to support regimechange? No trigger had been found since the failure at GlenShiel, when Spain’s frustrations had led them to support theStuarts, and the best chance had been lost in the ’15 even beforethat. Although Jacobitism was still a potent force, time was <strong>not</strong>on its side, and it would take an immense effort to revive loyaltyto the cause across the whole <strong>of</strong> Britain. All this Charles knew,and the whole network <strong>of</strong> Jacobites – at home and in exile –knew it also. Every opportunity had to be taken, since in theyoung Charles the cause had something it had previously lacked:charismatic leadership.Charles’ opportunity was coming. In 1738, Captain RobertJenkins <strong>of</strong> the brig Rebecca presented his severed ear (no doubtmuch grizzled) to the House <strong>of</strong> Commons. It had been cut <strong>of</strong>fseveral years before after his ship had been boarded by Spaniards,and alongside evidence <strong>of</strong> other Spanish provocation this eventprovided the pretext for a British declaration <strong>of</strong> war on Spain.The great Latin empire had supported King James before;29

VALOUR DOES NOT WAITperhaps they would do so again. In 1739, the Duke <strong>of</strong> Ormondeand the Earl Marischal, powerful and capable Jacobite exiles,rushed to Spain to negotiate support for a new Jacobite rebellion.Hopes were high, but quickly dashed. Spain would <strong>not</strong> providethe Stuarts with the necessary military assistance, as its attentionwas firmly on the Americas. Nevertheless, the War <strong>of</strong> Jenkins’ Earwas causing widespread discontent in Britain, eventually leadingto the downfall <strong>of</strong> its first prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole.War with Spain was, however, soon overshadowed by the spectre<strong>of</strong> a war far more dreadful, and immediate. The War <strong>of</strong> theAustrian Succession: total war on a global scale.In 1740, the death <strong>of</strong> the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles VI,drew central Europe into a war which would last for eight longyears. Maria Theresa, the emperor’s heir, provided the Habsburgdynasty’s enemies with their pretext for war, and they assertedSalic Law which prevented a female inheritance. Prussia, Franceand Spain were amongst those states that lined up against MariaTheresa, and Britain’s links with Hanover therefore drew it intoopposition to France, as well as Spain. Although Britain had <strong>not</strong>yet entered the war, it was only a matter <strong>of</strong> time before George IIwas drawn to action in his capacity as Elector <strong>of</strong> Hanover. AnAnglo-Spanish war may <strong>not</strong> be enough to trigger a Jacobiterebellion, but a war that pitted Britain against both Spain andFrance, played for the very highest stakes on a massive scale, mustsurely provide the ripest opportunity the Muti court couldenvisage. The Jacobite world, already on the alert over theSpanish war, now awoke to the real possibility that somethingmight actually happen. It was time to make ready.Whilst the Stuarts’ best hopes on the continent lay withFrance, in Britain they rested on Scotland. Along with Ireland,that nation had provided the most active and long-standingcommitment to the cause, and was also possessed <strong>of</strong> severalstrategically important advantages. The first was the relativeremoteness <strong>of</strong> its highlands, providing a chance for any internalrebellion to gather some momentum before interception. The30

A ENEASsecond, and perhaps most significant, was the fact the Scottishhighlanders were the most warlike <strong>of</strong> the British peoples, with atradition <strong>of</strong> bearing arms that had largely become dormant in, forexample, much <strong>of</strong> England. Combined with the large number <strong>of</strong>Scots and Irish serving in foreign armies, the prominence <strong>of</strong>Episcopalian worship (<strong>not</strong>ably in the east), and the simmeringresentment still lingering after the Act <strong>of</strong> Union (1707), Scotlandwas clearly the best landing stage for any proposed rebellion.Nevertheless, Jacobite contacts were nationwide, and sympathyfor the exiled dynasty could be found across Wales and Englandtoo. The task was to transfer genteel toasts to the King Across theWater into active military and political succour. To that end,King James’ network began to heave with activity.Perhaps sensing the moment was drawing near, JamesDrummond, the staunchly Jacobite and eminently likeable Duke<strong>of</strong> Perth, presented Prince Charles with a highland targe. A roundshield <strong>of</strong> 19 inches diameter, covered in pigskin and backed withleopard, the magnificent object was adorned with silverdecorations <strong>of</strong> battle standards, fasces, 8 broadswords and pistols.In its centre, a formidable Medusa gripping in her gnarling teetha ferocious spike. It is a weapon designed to represent theauthority <strong>of</strong> the bearer, whilst the gorgon petrified his enemies.Charles, receiving the weapon in 1740, was a young man morethan ever aware <strong>of</strong> his responsibility as the military saviour <strong>of</strong> thecause. And it would be the highlands that provided the means forhim to achieve it. 98 The ancient symbols <strong>of</strong> authority, the fasces were a bundle <strong>of</strong> rods boundupon an axe carried ahead <strong>of</strong> the magistrates and politicians <strong>of</strong> the ancientRoman Republic. They symbolised the power <strong>of</strong> the individual behindthem to forcibly move people from their path, and the number <strong>of</strong> slavesbearing the fasces reflected the status <strong>of</strong> the magistrate. Revived as symbolsby Mussolini, they gave their name to the fascists.9 The targe was lost by Charles during the escape from Culloden, along withmost <strong>of</strong> his personal baggage. It was rescued by Cluny <strong>of</strong> Macpherson, andcan now be seen in the National Museum <strong>of</strong> Scotland.31

VALOUR DOES NOT WAITMore practically, potential supporters <strong>of</strong> a rising werebeginning to band together and express themselves. Associationsbegan to be formed, the most <strong>not</strong>able being that which included:the Duke <strong>of</strong> Perth and his uncle Lord John Drummond; the Earl<strong>of</strong> Traquair and his brother; Sir John Campbell <strong>of</strong> Auchenbreck;Cameron <strong>of</strong> Lochiel, de facto chief; and Simon Fraser, LordLovat. They were a mixed band, some <strong>of</strong> whom would prove farmore useful than others, and they were stirred into movement in1740 by contact from the continent. John Murray <strong>of</strong> Broughton,an able man who ruined his reputation by turning King’sEvidence when the ’45 collapsed, was also becoming highlyactive, whilst the young and well-connected Lord Elcho wasbeing drawn ever deeper into the plots. If his narrative is to bebelieved, however, he was simply being naive. At the samemoment, the irrepressible Gordon <strong>of</strong> Glenbucket was insisting toKing James that 20,000 men could rally to his standard as soonas they were armed, but the king was too sensible to be sweptalong. Messengers criss-crossed Europe, initially promising aFrench invasion in 1742/3, although this failed to materialiseafter the death <strong>of</strong> Cardinal Fleury, and French ministers deniedhaving ever entertained the plan.Nevertheless, the wheels were now turning and the overallsituation in Europe was moving in favour <strong>of</strong> King James. TheFrench had suffered a strategic reverse in the war with Austria,and their position was significantly less promising than it hadonce appeared. British forces had landed on the continent in July1742, and despite there being no formal war declared betweenBritain and France, King George had won an impressive victoryover the French at Dettingen within a year. If the British couldturn the tide <strong>of</strong> the war in Europe, then France would providethem with a distraction elsewhere: the Jacobites. As 1743 drew toa close, the French invited Charles to Paris, and the young princecame with all the authority he needed.32

A ENEASJames R.Whereas We have a near Prospect <strong>of</strong> being restored to theThrone <strong>of</strong> our Ancestors, by the good Inclinations <strong>of</strong> ourSubjects towards Us, and whereas, on account <strong>of</strong> the presentSituation <strong>of</strong> this Country, it will be absolutely impossible forUs to be in Person at the first setting up <strong>of</strong> Our RoyalStandard, and even sometime after, We therefore esteem it forOur Service, and the Good <strong>of</strong> Our Kingdoms and Dominionsto nominate and appoint, Our dearest Son, CHARLES, Prince<strong>of</strong> Wales, to be sole Regent <strong>of</strong> Our Kingdoms <strong>of</strong> England,Scotland, and Ireland, and <strong>of</strong> all other Our Dominions,during Our Absence.23rd December 1743 in the 43rd Year <strong>of</strong> Our Reign, J RKing James’ Commission for Prince CharlesAeneas left Rome in a suitably adventurous manner. The Princewas accustomed to sleeping in a chair fully clothed, ready to head<strong>of</strong>f for the hunt at one or two in the morning, and so there was<strong>not</strong>hing remarkable about the day he announced that he wasleaving for a shooting trip in Cisterna ahead <strong>of</strong> his brotherHenry. Few had been present to witness the moment he partedcompany with the King:Charles:King James:I go, sire, in search <strong>of</strong> three crowns, which Idoubt <strong>not</strong> but to have the honour and happiness<strong>of</strong> laying at Your Majesty’s feet. If I fail in theattempt, your next sight <strong>of</strong> me shall be in ac<strong>of</strong>fin.Heaven forbid that all the crowns in the worldshould rob me <strong>of</strong> my son. Be careful <strong>of</strong> yourself,my dear prince, for my sake and, I hope, for thesake <strong>of</strong> millions. 1010 Marshall (1988): 51.33

VALOUR DOES NOT WAITC<strong>of</strong>fin or otherwise, the king would never see his belovedCarluccio again. This tender farewell was the beginning <strong>of</strong> thegreat adventure that would define Charles’ life. When Henryreached the rendezvous, he was told that his brother had beendelayed by a riding accident, but in reality he had begun a raceacross Europe. He defied the spies <strong>of</strong> his enemies, slipped past theRoyal Navy to land at Antibes, and crossed France in anastonishingly rapid five days. The preparations in Italy had stoodup to the first test, and Charles wrote with some amusement thathis travelling companions were, ‘quite rendu,’ and had scarcelykept pace with him.The excitement was tangible. After a lifetime <strong>of</strong> <strong>wait</strong>ing andtraining, the opportunity had come at last. Scarce had theadventure begun, however, when Charles was met with his firstdisappointment. King Louis was clearly caught <strong>of</strong>f guard by hisarrival. The French plan had been for a large scale invasion <strong>of</strong>southern England to be led by Ormonde and the esteemedgeneral Marshal Saxe, whilst the Earl Marischal led a diversionarylanding in Scotland. Charles’ presence, with the manifestoswritten in the king’s name, would make the expedition look morelike liberation than invasion. Charles’ rapid descent on Paris,however, quickly identified that he was unlikely to tolerate beinga mere figurehead. After a lukewarm reception at the Frenchcourt, Charles was obliged to remain incognito. He was soon tohave so many aliases that even he must have struggled torecognise his true self. When he moved to Gravelines to join withthe gathering invasion force, he was Baron Douglas, and theadventure seemed back on track as he moved amongst thecommon soldiery whilst his anticipation mounted.Unfortunately, more disappointment was to follow. Theinvasion fleet was scattered by a terrible storm, and although the<strong>of</strong>ficial outbreak <strong>of</strong> war between France and Britain should havehelped Charles, it simply meant that French attention shifted toFlanders and Saxe went <strong>of</strong>f without even the courtesy <strong>of</strong> tellingthe Prince. It was March 1744, and Charles was already insisting34

A ENEAShe would be better <strong>of</strong>f alone than with friends like the French.He was <strong>not</strong> being unrealistic, for as much as a rising would needarms, money, and military pr<strong>of</strong>essionals, the European contextmeant that anti-French feeling in Britain largely outweighed anylingering Jacobite sympathies. Aware <strong>of</strong> his lack <strong>of</strong> militaryexperience, Charles was eager to join the French army in Flandersbut this would have played into the hands <strong>of</strong> his domesticenemies, and his youthful militarism was appropriately deflectedby, among others, the Earl Marischal. Besides, by the timeCharles returned to Paris, Louis had already gone to war withouthim. Frustrated at every turn, the Prince flouted his incognito,even sitting cheekily close to the queen <strong>of</strong> France herself during aball and drawing her attention. It was deliberate provocation, aretaliation against the poor treatment he had received from Louis.He moved to Fitz-James, belonging to the relations who hadtaken him to Gaeta, and struck up a warm friendship with hisother relatives, the du Bouillons. As he spent increasing amounts<strong>of</strong> time with the family, perhaps he caught the eye <strong>of</strong> his cousin,Louise de la Tour. She had once been recommended as apotential wife for the Prince, but James had rejected the idea andshe had instead married into powerful French connections.Whatever they thought <strong>of</strong> one a<strong>not</strong>her in early <strong>1745</strong>, 11 theycould hardly have expected what the future held for them.As the King <strong>of</strong> France mused over how to rid himself <strong>of</strong> thenuisance that he had unwittingly brought into his sphere – Louiswas probably conscious his behaviour had lacked courtesy –Charles plotted how to kick-start the grand adventure withouthim. Within his small court there was certainly no lack <strong>of</strong>activity. Murray <strong>of</strong> Broughton cast caution to the wind and,forgetting the Associators’ conditions, had become swept up inthe enthusiasm and persuaded Charles that Scotland would rise.11 Possibly <strong>not</strong> too much, as Louise had just become pregnant for the firsttime and Charles was busy focussed on his more important tasks. Hecertainly did, however, take great comfort in the friendly familyatmosphere.35

VALOUR DOES NOT WAITTo provide some military expertise, John William O’Sullivan hadbeen put in charge <strong>of</strong> the Prince’s household, where he could alsodemonstrate his skills as an organiser. A loan <strong>of</strong> 180,000 livreswas secured to purchase weapons, and ships were sought toprovide transport and protection. O’Sullivan soon sensed, ‘therewas something abrewing,’ and was at last let in on the secretplanning. He quickly procured, ‘1800 sabres, such as are fit for thehighlanders, several cases <strong>of</strong> Pistols, an Armor, Bed, & set <strong>of</strong> pleat forthe Prince’. 12 On the 5th July <strong>1745</strong>, with the exiled Prince <strong>of</strong>Wales disguised as a divinity student from the Scots College inParis, the adventure began, and the expedition set sail.Aeneas was on the move at last, and soon had a chance toprove his warrior’s mettle. When the Prince’s ship and its escort,the Elisabeth, were intercepted by a British man <strong>of</strong> war, a seabattle ensued. For hour after hour, the two ships pounded eachother with cannon fire until both the Elisabeth and the BritishLyon were crippled. Throughout the engagement, Charleswatched from the small frigate Du Teillay, and O’Sullivan wasimpressed by, ‘the ardeur the Prince shewed on yt occasion; he’dobsolutly have a share in the fight.’ Although the expeditionaryforce had held its own, Captain D’O and most <strong>of</strong> the Elisabeth’s<strong>of</strong>ficers were dead and the ship was unable to proceed further.Distressingly for the cause, it returned to France with most <strong>of</strong>Charles’ supplies. Undeterred, the Prince pressed on and finallylanded in Scotland on 23rd July. The legendary Seven Men <strong>of</strong>Moidart (undoubtedly there were more) were all Charles had torestore his father’s fortunes.The enterprise was bold, nay rash, and unexampled.Captain James Johnstone12 O’Sullivan (1938): 46-7. For Armor, read armoire (a travelling chest), andfor pleat, plate.36

A ENEASUnexampled it certainly was. The Rising was starting cold,without the necessary supplies let alone troops. Was Charlescompletely mad? There was a fine line between determinationand boldness, and the reckless rashness <strong>of</strong>ten attributed to thePrince. For Charles, however, this was simply the dynamism thecause so badly needed. Certainly the reception the expeditionaryforce received when it arrived was less than reassuring, and therewas a desperate rush by individuals to either distance themselvesfrom a rising that looked certain to fail, or to persuade Charles toa<strong>wait</strong> a more favourable opportunity. He was, however,determined to hazard everything in the current enterprise.Elcho makes much <strong>of</strong> Charles’ assumption that Britain wasripe for rebellion: ‘he had been persuaded... the house <strong>of</strong> Hanoverwas detested and that the whole country would rally to his standardon his appearance.’ This is to misunderstand his mind. CertainlyCharles had faith that once the Rising was in motion itsmomentum would gather immense support and in time becomea national movement. At the same moment, he was also keenlyaware that this was his best opportunity to achieve something.He and his father had <strong>wait</strong>ed long enough. The memory <strong>of</strong> KingLouis’ cool reception was still fresh in his mind. Each year thatpassed weakened Charles’ hand in Europe and strengthened theHanoverian dynasty’s hold in Britain. Besides, he was <strong>not</strong> sonaive as to believe he could overwhelm the military might <strong>of</strong> theyoung British Empire, something that was never really hisintention. Instead, he was affecting regime change, with thesupport <strong>of</strong> a liberal manifesto and an unshakeable determinationto fulfil his destiny. As such, the expedition should be seen asbold indeed, but reasoned, balanced against the reality that thismight be the Stuarts’ last chance. France was a false friend, andonly those who had proven their loyalty in the past could now berelied upon. As such, Charles was <strong>not</strong> just being hopelesslyromantic when, on being told to go home by Boisdale, heparried:37

VALOUR DOES NOT WAITI am come home, sir, and I will entertain no <strong>not</strong>ion at all <strong>of</strong>returning to that place from whence I came; for that I ampersuaded my faithful highlanders will stand by me.Charles Edward StuartThe statement was early evidence <strong>of</strong> the Prince’s most formidableweapon: his own character. From the outset, Charles set aboutwinning over his reluctant supporters and binding them to out <strong>of</strong>loyalty <strong>not</strong> just to the cause, but to himself. That he earned thatloyalty, from hard-headed and powerful men, is pro<strong>of</strong> positive <strong>of</strong>both his skill and his charm. This was no foppish Italian prince;it was a man who came meaning business and who promised toshare in the risks.On 19th August <strong>1745</strong>, one <strong>of</strong> the most inspiring andsignificant dates in Scottish history, Charles moved up the greatlength <strong>of</strong> Loch Shiel, still in disguise, with a small flotilla <strong>of</strong>Clanranald bodyguards. During the halt at Dalilea, the RoyalStandard had been given its finishing touches, patched togetheras it was from whatever had been available on the Du Teillay. Themessages had been dispatched, the preliminary interviews anddebates concluded. All that remained was to see whether thegamble had paid <strong>of</strong>f. He stepped up to the prow <strong>of</strong> the long boatas the rendezvous came into sight. As the boats beached gently,he stepped onto the shingle and crossed the small rivulet that fedthe loch. The young adventurer’s heart thumped hard, and hestruggled to suppress his nerves at the lack <strong>of</strong> a reception. Soonsmall numbers <strong>of</strong> people had gathered about here and there,curious locals mildly interested in the unusual activity. After ananxious eternity scanning the empty horizon, Charles moved intothe shade <strong>of</strong> a low bothy, perhaps to hide his nerves from thoseabout him. As morning passed into noon, at last the longed-foractivity occurred. The distant sound might have come fromwithin his mind, he thought, until it became clearer and morecertain. He stepped out, as those men stationed on a nearbyeminence carried the message along the vale. In regular columns,38

A ENEASand in reassuring numbers, the men <strong>of</strong> Clan Cameron marchedbeneath the strains <strong>of</strong> their pipers. Relief gave way to joy: ifLochiel would come, then the whole west would surely follow.Ageing but loyal, the Marquess <strong>of</strong> Tullibardine, Jacobite Duke<strong>of</strong> Atholl, raised the Standard, and the Prince’s commission <strong>of</strong>regency was read along with his political manifestos. Thegathering army gave out a great huzzah, and Charles stoodforward. ‘He was in the prime <strong>of</strong> youth, tall and handsome, and <strong>of</strong> afair complexion,’ 13 and cut a fine figure as he acknowledged thecheers. He made a short, stirring speech before he, ‘ordred yt somekasks <strong>of</strong> brandy shou’d be deliver’d to the men, to drink the Kingshealth’. After several days, as the clans were consolidated into themakings <strong>of</strong> an army, and when the available munitions and armshad been distributed, the campaign began. First blood hadalready gone to the Jacobites, who had ambushed a company <strong>of</strong>Royal Scots at High Bridge. Now the war must begin in earnest.The gamble had paid <strong>of</strong>f indeed, and Charles was now incommand <strong>of</strong> about 1,200 men. The initiative lay with him.Prisoners present at Glenfinnan were dispatched to report on thesuccess <strong>of</strong> the gathering, and the quality <strong>of</strong> the Prince. Havinginitially dismissed reports <strong>of</strong> the Prince’s landing, theGovernment was awakening too late to the reality <strong>of</strong> the threat.With their main forces, including much <strong>of</strong> the new Black Watchregiment, tied up in Flanders, the highland garrisons were tooweak to respond effectively. If Charles was to be stopped, itwould have to be John Cope who stopped him. An experiencedveteran, Sir John was able and willing, but conscious that hisforces were far from infallible. When all the ovens <strong>of</strong> Edinburghhad given up their bread, the British Army moved north. Manyin the establishment believed that it was just a case <strong>of</strong> nipping theRising in the bud, <strong>of</strong> dispersing a discontented rabble. If onlythey could have seen the swift marches <strong>of</strong> the hard mountainmen, and their swelling numbers. If only they could have13 According to John Home, no friend <strong>of</strong> the cause.39

VALOUR DOES NOT WAITimagined the newly formed Jacobite Army, eager for battle andfor the righting <strong>of</strong> ancient wrongs:The brave Prince marching on foot at their head like a Cyrusor a Trojan hero, drawing admiration and love from all thosewho beheld him, raising their long dejected hearts, andsolacing their minds with the happy prospect <strong>of</strong> a<strong>not</strong>her GoldenAge.John DanielA Trojan hero indeed: having left his distant land behind, bravingadversity and war at sea, following a destiny he now trulyunderstood, Aeneas had come to fight. Arma virumque cano. 1414 ‘I sing <strong>of</strong> arms and <strong>of</strong> a man,’ Virgil, Aeneid, I.1.40

The PoliticianThe Christian hero’s looks here shine,Mixt with the sweetness <strong>of</strong> the Stewart’s line.Courage with mercy, with virtue join’d,A beauteous person with more beauteous mind.How wise! How good when great! When low, how brave!Who knows to suffer, conquer, and to save.Such grace, such virtues, are by Heav’n design’d.To save Britannia and bless mankind.Anon, Lyon in Mourning 15Charles had an enormous mountain to climb, and <strong>not</strong> just interms <strong>of</strong> militarily overthrowing the British government. In orderto raise, maintain, and keep his army, he needed skills beyondthose <strong>of</strong> an ordinary general. In an army <strong>of</strong> volunteers (orsomething very near that), there is <strong>not</strong> the inherent discipline andobligatory obedience which can be found amongst regular forces.Nor are there the structures and systems <strong>of</strong> support and supply.Charles also knew that an army <strong>of</strong> a few thousand stood littlehope <strong>of</strong> overwhelming the entire nation, without widespreadpublic support and sympathy. He was a liberator, he believed, <strong>not</strong>a conqueror, and as such he could neither shun nor alienate anypart <strong>of</strong> the society into which he had thrust himself. If he was tosucceed, he needed to be a statesman, a diplomat, and apolitician.In this regard, the Prince has acquired a rather mixedreputation. His conduct and manner have been much criticised,and even his intelligence has been questioned. Elcho, whosereflections on the ’45 always carry the bitter tone <strong>of</strong> a mandisgruntled, <strong>not</strong>ed that before the Rising, ‘the Prince was very15 The poem records a gentleman’s reaction on seeing the Prince’s portrait.Forbes (1895): II.359.41