Litigation Review No16 - Ogier

Litigation Review No16 - Ogier Litigation Review No16 - Ogier

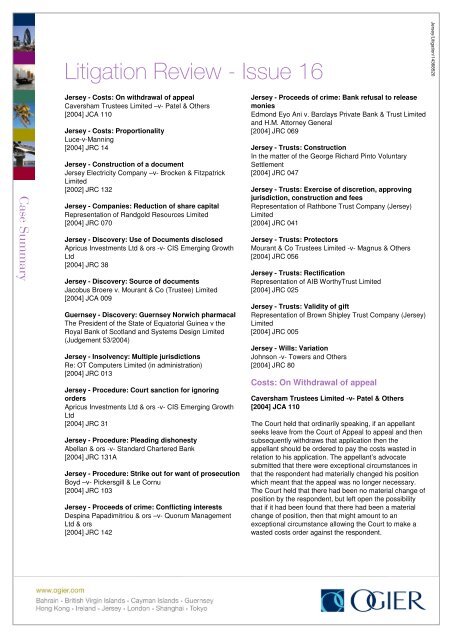

- Page 3 and 4: Litigation Review - Issue 16Case Su

- Page 5 and 6: Litigation Review - Issue 16Case Su

- Page 7 and 8: Litigation Review - Issue 16About O

<strong>Litigation</strong> <strong>Review</strong> - Issue 16Case Summaryor power in his capacity as a beneficiary but alsoincluding all relevant documents irrespective of thecapacity in which they had come into his possession,custody or power.The Court of Appeal stated that so long as documents arerelevant it does not matter in what capacity they are heldin a person’s possession, custody or power and thereforethey must be listed in the Affidavit of Discovery.Discovery: Guernsey Norwich pharmacalThe President of the State of Equatorial Guinea v theRoyal Bank of Scotland and Systems Design Limited(Judgement 53/2004)Two companies based in Guernsey were alleged to holdassets used to fund an attempted coup d’etat in theRepublic of Equatorial Guinea. The plaintiffs had obtainedan ex parte Norwich Pharmacal order seeking disclosurefrom the defendants, which the defendants now sought todischarge.The Court considered that, where the purpose of NorwichPharmacal relief is to assist a victim of a wrong-doing,there is no reason in principle to refuse the relief merelybecause corrective action is taking place outside thejurisdiction. However, this was subject to the reservationthat a court exercising its equitable jurisdiction to grantdisclosure would be expected to retain control over theuse of the order made. The Court felt that the plaintiff hadnot given sufficient thought as to what mechanism mightbe put in place with regard to the Court retaining effectivecontrol over the information disclosed and concluded thatno order should be made unless the plaintiff identified theuse to which the disclosure would be put. The order fordisclosure was stayed with leave to the plaintiff to returnwith specific proposals on this issue and on how theCourt might retain some effective control over thatinformation.Insolvency: Multiple jurisdictionsRe: OT Computers Limited (in administration)[2004] JRC 013A Jersey company (which carried on the bulk of itsbusiness in England) had previously sought a Letter ofRequest be issued from the Royal Court seeking theassistance of the English High Court in the making of anadministration order under the Insolvency Act 1986. TheEnglish High Court had made the administration orderrequested.The company now sought a further Letter of Request witha view to discharging the administration order and placingthe company into an English creditors’ voluntaryliquidation. The Royal Court held that it had an inherentjurisdiction to agree to an application being made to theEnglish Court in order that the insolvency proceedings becompleted in England, notwithstanding the availability ofalternative remedies in Jersey. Taking into the accountthe duplication of costs involved should insolvencyproceedings take place in both jurisdictions concurrently,the court concluded that it would be in the best interestsof the creditors for the insolvency proceedings to continuein England, although the company could return to theRoyal Court should that prove necessary.Procedure: Court sanction for ignoringordersApricus Investments Ltd & ors -v- CIS EmergingGrowth Ltd[2004] JRC 31The defendant had failed to comply with two orders of theRoyal Court requiring disclosure of financial and companyinformation. The Court registered its disapproval that asubsidiary of the Bank Austria Group should refuse tocomply with orders of the Jersey Royal Court. The Courtinvited the plaintiffs to liaise with both the British and UKregulatory authorities in order that the matter could betaken up with their Austrian regulatory counterparts.Procedure: Pleading dishonestyAbellan & ors -v- Standard Chartered Bank[2004] JRC 131AWhere a plaintiff suspects the defendant of dishonesty(which includes a plea of Nelsonion blindness, i.e. wherethe defendant has made a conscious decision not to askquestions because he has suspicions and does not wishto have those suspicions confirmed), but as yet has noevidence on which to found that suspicion, the properapproach to pleading is not to plead dishonesty, but tocommence proceeding by pleading a non-dishonestbreach of duty and then amend those pleadings if, ondiscovery, sufficient material is produced to found aproper plea of dishonesty.Procedure: Strike out for want ofprosecutionBoyd –v- Pickersgill & Le Cornu[2004] JRC 103The defendant had allegedly committed negligence or abreach of contract at the latest on 13 February 1987. Theplaintiff issued her order of justice on 21 April 1997. TheCourt of Appeal had held that the running of time for thepurposes of prescription had been suspended untilAugust 1989, which meant that the plaintiff was within theprescription period when she issued her proceedings inApril 1997. However, the Court of Appeal hademphasised that the plaintiff “having taken so long to starthese proceedings, is now obliged to take theseproceedings to trial with due speed. No further delayshould be permitted”. In fact nothing procedurally hadtaken place since the Court of Appeal issued its judgmentin September 1999. The Master issued a circular listingthe cases which the Court was minded to strike out of itsown volition. The plaintiff issued a summons seeking toshow cause why the action should continue and theADMIN-14368520-2

<strong>Litigation</strong> <strong>Review</strong> - Issue 16Case Summarydefendant issued a summons to strike out for want ofprosecution.The Court found that it must ask itself three questions inconnection with an application for dismissal for want ofprosecution: (i) Has there been inordinate delay? (ii) If so,has such delay been inexcusable? (iii) If so, has suchdelay given rise to a substantial risk that it is not possibleto have a fair trial of the issues in the action or is such asis likely to cause or to have caused serious prejudice tothe defendants?As to the first question, the Court found that the actionhad not progressed at all since September 1999 despitethe warnings of the Court of Appeal. The Court had nohesitation in categorising such delay, particularly after thelong delay in the issue of the proceedings in the firstplace, as inordinate. As to the second question, the Courtalso had no hesitation in finding that the delay wasinexcusable, notwithstanding that there had been somenegotiations ongoing. It is the responsibility of a plaintiff toprogress matters, and the plaintiff has to takeresponsibility for the actions or inactions of her advisers.The question of whether delay is inexcusable alsorequires a consideration of whether the defendants havein any way encouraged or agreed to the delay. Thedefendants had confirmed in September 2000 that theywould not take a point on delay pending possiblesettlement discussions. The Court held that thedefendants could not possibly have envisaged that thenegotiations would take a further three years from then.The fact that the defendants had not formally given noticethat time was now running again was irrelevant. In realitythere were no continuing negotiations. The defendants’confirmation could not be construed as allowing theplaintiff an open ended period to take as long as she likedto progress her matter.Finally, the Court found that the additional delay sinceSeptember 1999 was such as is likely to cause seriousprejudice to the defendants by reason of a further loss ofrecollection.[For further example of application of principles forstriking out on these grounds see – GamlestadenFastigheter AB –v- Baltic and ors[2004] JRC 131]Proceeds of crime: Conflicting interestsDespina Papadimitriou & ors –v- QuorumManagement Ltd & ors[2004] JRC 142The Royal Court refused to strike out a claim alleging thata trustee was in breach of its contractual and/or fiduciaryduties where, following filing of a Suspicious TransactionReport under the Proceeds of Crime (Jersey) Law 1999by the trustees, the trustees had refused to releaseproceeds from the sale of a house to the trustsbeneficiary. The plaintiff beneficiary alleged that thedefendants acted in breach of their duties to her byseeking to protect their own interests under the 1999 LawADMIN-14368520-2ahead of her interests, and doing so in a manner whichinvolved deceiving her as to the real reason why theywould not comply with her instructions.The plaintiff also alleged that the defendants weremistaken and negligent in concluding that there were anygrounds under the 1999 Law for failing to comply with herinstructions. The test for striking out requires it to be plainand obvious that the case cannot succeed. The mere factthe case is weak is no ground for striking out. The courtdeclined to strike out the case, commenting that this is adeveloping area of law, and the interaction of anti-moneylaundering legislation with the duties and obligations oftrustees who have developed a suspicion that they maybe dealing with tainted funds is as yet untested.Proceeds of crime: Bank refusal to releasemoniesEdmond Eyo Ani v. Barclays Private Bank & TrustLimited and H.M. Attorney General[2004] JRC 069The Royal Court considered the position of customersand financial institutions when there is a suspicion ofmoney laundering so that the provisions of Article 32 ofthe Proceeds of Crime (Jersey) Law 1999 apply.The Court recognised that there is at present no clearguidance from the Courts on the appropriate procedure toresolve matters when a customer is denied access to hisfunds by a Bank because of a suspicion of moneylaundering coupled with a refusal to consent todistributions on the part of the police.The Court felt that an application for costs was not theoccasion upon which to give such general guidance.However, it noted that there were two ways in which anaggrieved customer may try and obtain access to frozenfunds. Firstly, he could institute a public law actionagainst the police seeking an order that their refusal toconsent to payments be quashed and that they beordered to consent. Alternatively, the customer couldinstitute a conventional private law action against theBank seeking an order that it pays him his funds.Trusts: ConstructionIn the matter of the George Richard Pinto VoluntarySettlement[2004] JRC 047The trustee sought an order empowering it to pay capitalfrom the settlement into a new trust established for thebenefit of the children of the beneficiary of the settlement,such children not being themselves beneficiaries. Thetrust deed as drawn did not permit the addition of furtherbeneficiaries, and the trustees, whilst they wereempowered to pay away capital for the benefit of any oneor more of the beneficiaries, were only permitted toappoint new or other trusts for the benefit of all or any oneof the beneficiaries, so long as no other persons werebenefited. The Court held that those words were clear

<strong>Litigation</strong> <strong>Review</strong> - Issue 16Case Summaryand admitted of only one construction. The applicationwas therefore refused, as the provisions of the settlementdeed as drawn expressly prohibited the trustee fromdoing that which it now wished to do. The deed must beread and construed as a whole. The relevant clause ofthe settlement deed provided four overriding powers, andthe Court should not look for powers which were notexpressed on the face of the document when there wereprovisions expressly dealing with what the trustee wishedto do.Trusts: Exercise of discretion approvingjurisdiction, construction and feesRepresentation of Rathbone Trust Company (Jersey)Limited[2004] JRC 041This case is an example of the Court giving sensibleadministrative directions to assist a trustee.DK died resident and domiciled in the Netherlands. By hiswill he left a sum of money to each of his grandchildren“to be held in custody for them by the same Jersey trustarrangement” (as was mentioned elsewhere in the will)“which sum together with accrued interest and dividendswill be put to the disposal of the beneficiary in five equalinstalments, the first to be paid when reaching the age oftwenty-five…”.investment, this could not be determined from the termsof the will. However, the Court accepted the proposal thatthe funds be invested in the same manner as the trustassets of the related trust as this would bring economiesin terms of investment management costs. TheRepresentor would of course need to be mindful of theneed for prudence in investment decisions concerning thegrandchildren’s funds.Trustee Remuneration: The Will trust was silent ontrustee remuneration. The Representor applied underArticle 17 of the Law for approval that it be permitted tocharge fees. Following the authority of Re the R FNorman Settlement [2002] JRL61 the Court held it to beunrealistic to expect a professional trustee to act withoutremuneration, and in the interests of beneficiaries thattrusts should be managed professionally.In the course of the hearing the Court also affirmed thetest as first set out in Jersey in the Re S Settlement forapproving a trustee’s exercise of discretion, name: (i) isthe Court satisfied that the trustee had in fact formed itsopinion in good faith? (ii) is it satisfied that the opinionwhich the trustee has formed is one at which areasonable trustee properly instructed could havearrived? (iii) is it satisfied that the opinion at which thetrustee has arrived has not been vitiated by any actual orpotential conflict of interest which has or might haveaffected its decision?A number of issues arose in relation to the bequest. As apreliminary issue, did the Court have jurisdiction to hearthe case? If it did, did the trustee have the power to investthe monies and if so what was the scope of theinvestment powers. Further, should the trustee beremunerated?Jurisdiction: The wording was sufficient to create a newtrust. The monies were not however settled on theexisting Jersey trust referred to elsewhere in the will (andadministered by the same trustee). Article 4 of the Trusts(Jersey) Law 1984 (‘the Law’) sets out the test fordetermining the proper law of a trust. Whilst the properlaw was not set out expressly, it could be implied from thewording “to be held by the same Jersey trustarrangement” as this indicated an intention to link toJersey as opposed to another jurisdiction. Alternatively,Jersey was the jurisdiction with which the trust had itsclosest connection at the time of creation, as the place ofadministration, situs of the assets, place of residence ofthe trustee and where the objects of the trust would befulfilled were all in Jersey. The sections of the Lawapplicable to Jersey law trusts were therefore applicable.The requirements of Article 5 (jurisdiction of the Court)were also satisfied by reason of the trust being a Jerseylaw trust, but it was noted they would have been satisfiedin any event as the trustee was resident in Jersey, assetswere situate and administered in Jersey.Investment Powers: The wording “which together withaccrued interest and dividends” was held to indicate anintention that funds would be invested rather than simplybe left on deposit to accrue interest. As to the manner ofADMIN-14368520-2For further example of application of Re S[2001] JLR N-7, see Re Securities Services Ltd[2004] JRC 122.Trusts: ProtectorsMourant & Co Trustees Limited –v- Magnus &Others[2004] JRC 056The protector of a trust had committed serious criminaloffences including misappropriation of monies from thetrust itself. The protector had disappeared and could notbe found and so therefore could not be invited to resignfrom office. Did the Court have jurisdiction to remove aprotector from office absent any provision to that effect inthe trust deed? The Trusts (Jersey) Law confers no suchexpress power on the Court although there is provisionfor the removal of a trustee. However, the Court had longasserted a power to remove trustees for cause and hadno doubt that it had an inherent jurisdiction to remove aprotector of a trust from office for due cause. The Courtheld a protector is in a position of a fiduciary and theCourt must have power to police the activities of anyfiduciary in relation to a trust. It would be unconscionableand unthinkable that the Court should have no jurisdictionto remove a protector who was thwarting the execution ofa trust or who was otherwise unfit to exercise thefunctions entrusted to him by the trust instrument. TheCourt could think of few clearer cases calling for theexercise of its jurisdiction.

<strong>Litigation</strong> <strong>Review</strong> - Issue 16Case SummaryTrusts: RectificationRepresentation of AIB WorthyTrust Limited[2004] JRC 025Two settlements were executed in March and June 1985.The settlors relied to a very considerable extent upontheir professional advisers to ensure that the terms of thesettlement were such as to satisfy the best interests ofthe members of their families. It was necessary for thetrust funds to vest, at least in respect of income, in favourof one or more of the beneficiaries upon such beneficiaryattaining the age of 25 years. That object was notachieved.The Court held that the test to be applied is wellestablished and summarised it as follows: (i) the Courtmust be satisfied by sufficient evidence that a genuinemistake has been made so that the settlement/deed doesnot carry out the true intention of the parties; (ii) theremust be full and frank disclosure; and (iii) there should beno other practical remedy. The remedy of rectificationremains a discretionary remedy.The Court also referred to an earlier case wherein thefollowing statement was made:“The court has a discretion to rectify a mistake in a trustdeed at the suit of the settlor when it can be shown thatthe deed did not, in fact, give effect to his intentionsbecause of an incorrect legal advice he received at thetime of its preparation.”Mrs H signed an enduring power of attorney in favour ofher son, Mr H. She subsequently lost her mental capacityand the enduring power of attorney was registered withthe English Court of Protection. Mr H requested theJersey trustee declare a discretionary trust and arrangedto transfer certain assets to the trust of which his motherwas the sole beneficial owner. Mrs H had subsequentlydied.Under the provisions of the English Enduring Powers ofAttorney Act 1985, unless having consent of the Court ofProtection, the powers of an attorney to dispose of theproperty of the donor of the power by way of gift are verylimited. Mr H had made no such application for consentand accordingly, the Court declared that all of the assetspurportedly contributed to the trust were in fact not socontributed in law and were therefore held by the trusteeupon constructive trust for the estate of Mrs H. Theadvocate for Mr H sought to submit that, because thetransfers to the trust were void, the Court should alsotreat the transfers of the assets from the United Kingdomto Jersey as having never taken place. However, the factwas that the assets were physically situated in Jersey andin the name of the trustee. The position in law, therefore,was that there was an estate of Mrs H situated in Jersey.The normal rules must therefore apply and no paymentscould be made out of that estate unless and until a Jerseygrant of probate was obtained.Wills: VariationJohnson –v- Towers and Others [2004] JRC 80It was the intention of the professional advisers employedby the settlors to create accumulation and maintenancesettlements. It was clear from the evidence before theCourt that that object had not been achieved. The Courtwas accordingly satisfied that a genuine mistake hadbeen made and that the trust deed did not carry out thetrue intention of the parties. The Court was satisfied thatthese were proper applications for the discretionaryremedy of rectification and they were accordingly granted.The Court ordered in this case that the costs of theapplication be met out of the trust funds of the twosettlements.Representation of HSBC Trustees –v- Edwards[2004] JRC 114In respect of a trust governed by Guernsey law, aGuernsey advocate confirmed that he had no doubt thatthe decision of the Royal Court in the case of MJB/JBAmethyste Trust [2002] JLR 39 which stated that thethree requirements set out above, would be followed bythe Guernsey Royal Court.Trusts: Validity of giftRepresentation of Brown Shipley Trust Company(Jersey) Limited[2004] JRC 005The parties sought to vary the will of one Mr Towers. Byhis will he had left a legacy to one child, RT, and theremainder on discretionary trusts for his other child, CTand CT’s wife and their children and remoter issue. RT’sbequest was increased by agreement, and he no longerhad any interest in the estate. It was sought to vary thewill under Article 25 of the Probate (Jersey) Law, byinserting a legacy of £800,000 to CT with the residueremaining in discretionary trusts. It was then intended thatthe trustees would exercise their powers of appointmentunder the trusts to appoint the balance of the residue ontrust for the children and their remoter issue, effectivelyexcluding CT from further benefit from those assets. Theadvantage of the proposed variation was that the sum of£800,000 could be paid to CT free of inheritance andcapital gains tax if paid as a legacy. The variation wouldbe for the benefit of the children and remoter issue sincefollowing the appointment referred to above, CT would nolonger have any interest in the trust and they couldtherefore be expected to receive in due course the fullbenefit of the remaining trust funds. The Court thereforeapproved these arrangements as being in the interests ofthe minor and unborn children.If you have any questions in any of the cases referred toin this briefing, or would like more information, pleasecontact Kerry Lawrence at kerry.lawrence@ ogier.com.ADMIN-14368520-2

<strong>Litigation</strong> <strong>Review</strong> - Issue 16About <strong>Ogier</strong><strong>Ogier</strong> is an award winning world leader in the provision ofoffshore legal and fiduciary services. Our integrated legaland fiduciary approach has proved a winning combinationwhich enables us to secure awards for the quality of ourservices and our people.Case SummaryThe Group employs over 850 people and provides adviceon all aspects of BVI, Cayman, Guernsey and Jersey lawand fiduciary services through our international spread ofoffices that cover all time zones and key financialmarkets. Our network includes Bahrain, BVI, Cayman,Guernsey, Hong Kong, Ireland, Jersey, London,Shanghai and Tokyo.ADMIN-14368520-2

<strong>Litigation</strong> <strong>Review</strong> - Issue 16Contact detailsNORTH & SOUTH AMERICACaymanChris Russell+1 345 914 1685chris.russell@ogier.comEUROPE, MIDDLE EAST & AFRICAGuernseySimon Davies+44 (0) 1481 737175simon.davies@ogier.comCase SummaryJerseyKerry Lawrence+44 (0) 1534 504376kerry.lawrence@ogier.comMatthew Thompson+44 (0) 1534 504311matthew.thompson@ogier.comThis client briefing has been prepared for clientsand professional associates of the firm. Theinformation and expressions of opinion which itcontains are not intended to be acomprehensive study or to provide legal adviceand should not be treated as a substitute forspecific advice concerning individual situations.<strong>Ogier</strong> includes separate partnerships whichadvise on BVI, Cayman, Guernsey and Jerseylaw. For a full list of partners please visit ourwebsite.Please check with the relevant contact listedabove for specific details regarding the legalservices we offer from each office as we do notalways practice the law of the jurisdiction whereour offices are located. Please note that thenamed contact may not be qualified to advise onall the laws practiced from that office.