Water Efficiency for Instream Flow: Making the Link in Practice

Water Efficiency for Instream Flow: Making the Link in Practice

Water Efficiency for Instream Flow: Making the Link in Practice

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong><strong>Water</strong><strong>Efficiency</strong><strong>for</strong><strong>Instream</strong><strong>Flow</strong>:October 2011A jo<strong>in</strong>t project of <strong>the</strong> Alliance <strong>for</strong> <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong>, American Rivers,and <strong>the</strong> Environmental Law Institute

Project PartnersAlliance <strong>for</strong> <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong>300 W Adams Street, Suite 601Chicago, Ill<strong>in</strong>ois 60606www.alliance<strong>for</strong>waterefficiency.orgAlliance <strong>for</strong> <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong>The Alliance <strong>for</strong> <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> (AWE) is dedicatedto <strong>the</strong> efficient and susta<strong>in</strong>able use of water <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> United States and Canada. Based <strong>in</strong> Chicago,this nonprofit group advocates <strong>for</strong> water efficientproducts and programs and provides <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mationand assistance on water conservation ef<strong>for</strong>ts.AWE works with over 325 member organizations,provid<strong>in</strong>g benefit to water utilities, bus<strong>in</strong>ess and<strong>in</strong>dustry, government agencies, environmental andenergy advocates, universities, and consumers.American Rivers1101 14th Street NW, Suite 1400Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC 20005www.americanrivers.orgAmerican RiversAmerican Rivers is a conservation organizationstand<strong>in</strong>g up <strong>for</strong> healthy rivers so that communitiescan thrive. With over 65,000 members andsupporters, American Rivers works <strong>in</strong> five keyprogram areas—rivers and global warm<strong>in</strong>g, riverrestoration, river protection, clean water and watersupply—to protect our rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g natural heritage,undo <strong>the</strong> damage of <strong>the</strong> past and create a healthyfuture <strong>for</strong> our rivers and future generations.The Environmental Law Institute2000 L Street, NW, Suite 620Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC 20036www.eli.orgEnvironmental Law InstituteThe Environmental Law Institute (ELI) is a non-profit,non-partisan research and education organization.ELI’s mission is to advance environmental protectionby improv<strong>in</strong>g environmental law, policy andmanagement. S<strong>in</strong>ce 1969, ELI has been a preem<strong>in</strong>entsource of <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation on federal, state, and localapproaches to solv<strong>in</strong>g environmental problems.Through its research, practical analysis, and <strong>for</strong>wardlook<strong>in</strong>gpublications, ELI <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>ms and empowersop<strong>in</strong>ion makers, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g government officials,environmental and bus<strong>in</strong>ess leaders, academics,members of <strong>the</strong> environmental bar, and journalists.Project TeamMary Ann Dick<strong>in</strong>son, Alliance <strong>for</strong> <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong>C<strong>in</strong>dy Dyballa, Alliance <strong>for</strong> <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong>Michael Garrity, American RiversAdam Schempp, Environmental Law Institute1 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>

AcknowledgmentsThe Walton Family Foundationprovided fund<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> this project.A dedicated and enthusiasticadvisory group gave <strong>in</strong>valuableadvice, <strong>in</strong>sights and support.The f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs are not endorsedby <strong>the</strong> advisory group or <strong>the</strong>irorganizations:Larry MacDonnellUniversity of Wyom<strong>in</strong>gCollege of LawSteve OlsonArizona Municipal <strong>Water</strong> UsersAssociationJay Sk<strong>in</strong>nerColorado Division of Parksand WildlifeFrances Spivy-WeberCali<strong>for</strong>nia <strong>Water</strong> ResourcesControl BoardBrad UdallUniversity of Colorado andNOAA Western <strong>Water</strong> AssessmentMike WadeAgricultural <strong>Water</strong> ManagementCouncilMany throughout <strong>the</strong> westernU.S. provided <strong>in</strong>sights and<strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation through personal<strong>in</strong>terviews, phone conversationsand emails, shar<strong>in</strong>g draft reports,or attend<strong>in</strong>g a one-day work<strong>in</strong>gsession of experts. A specialthanks to Bill Christiansen andAlexa Loftus, Alliance <strong>for</strong> <strong>Water</strong><strong>Efficiency</strong>, and Brandon Souza,Agricultural <strong>Water</strong> ManagementCouncil, <strong>for</strong> assistance with<strong>the</strong> sections on municipal andagricultural water use efficiency.Contents3 Summary6 Chapter 1 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: OverviewAbout this Report<strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong>Streamflow17 Chapter 2 Lessons from Experience:Cases from Around <strong>the</strong> West35 Chapter 3 Legal Sett<strong>in</strong>g: The Colorado River Bas<strong>in</strong>47 Chapter 4 Challenges, Incentives and Promis<strong>in</strong>g Opportunities:<strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> and <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>sChallenges to Be MetIncentives and StrategiesCharacteristics of SuccessApproaches to PartnershipSett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Stage <strong>for</strong> Local ActionConclusion59 AppendicesSeparate Resource Sections on municipal, state and agriculturalwater efficiencyReport and Resource Sections onl<strong>in</strong>e:www.alliance<strong>for</strong>waterefficiency.org<strong>Water</strong><strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong><strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>:<strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>October 2011<strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>2

SummaryThroughout<strong>the</strong> Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>, with ever-expand<strong>in</strong>gdemands <strong>for</strong> multiple water uses and <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly uncerta<strong>in</strong>supply, any promis<strong>in</strong>g opportunity to do more with less iswelcome. The importance of healthy <strong>in</strong>stream flows, as oneof <strong>the</strong>se uses, is more press<strong>in</strong>g than ever. Improved waterefficiency can <strong>in</strong> concept help stretch water supplies and contributeto protection of aquatic environments and <strong>the</strong> resources and servicesthat <strong>the</strong>y provide.This report summarizes ef<strong>for</strong>ts to explore whe<strong>the</strong>r water efficiencyef<strong>for</strong>ts can be l<strong>in</strong>ked <strong>in</strong> practice to improved <strong>in</strong>stream flows <strong>in</strong>areas of <strong>the</strong> Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>. In brief, we found that practicalpossibilities to do this do exist with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> current context of <strong>the</strong>river bas<strong>in</strong>. Given a stream stretch with a clearly identified need <strong>for</strong>improved <strong>in</strong>stream flows and a realistic opportunity <strong>for</strong> improv<strong>in</strong>gwater efficiency, will<strong>in</strong>g partners generally can build <strong>the</strong> bridgesneeded to overcome o<strong>the</strong>r challenges.Project partners Alliance <strong>for</strong> <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong>, Environmental LawInstitute and American Rivers, each with a different perspective on <strong>the</strong>issue, posed several key questions which are addressed <strong>in</strong> this report:1. What is <strong>the</strong> practical experience <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> western U.S. <strong>in</strong> achiev<strong>in</strong>ggreater water efficiencies and apply<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m to <strong>in</strong>stream flows,and what lessons can we apply to <strong>the</strong> unique characteristics of <strong>the</strong>Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>?2. What is <strong>the</strong> legal sett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> each bas<strong>in</strong> state <strong>for</strong> apply<strong>in</strong>gconserved water to <strong>in</strong>stream purposes?3. What are <strong>the</strong> practical challenges to us<strong>in</strong>g water efficiencyprograms to improve <strong>in</strong>stream flows <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>?4. What are <strong>the</strong> most promis<strong>in</strong>g on-<strong>the</strong>-ground opportunities—<strong>in</strong>centives and strategies, characteristics of success, and approachesto partnership—<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> bas<strong>in</strong>?The Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong> is perhaps <strong>the</strong> most challeng<strong>in</strong>g riverbas<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nation: water demand now exceed<strong>in</strong>g supply, valued butfragile ecosystems, and support <strong>for</strong> nearly every type of water-relevant<strong>in</strong>terest. Build<strong>in</strong>g on this urgency led to this one-year survey projectto explore <strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>k between water efficiency programs and improved<strong>in</strong>stream flows <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>. Much is already knownabout how to achieve greater water efficiencies <strong>in</strong> urban and agriculturalwater use <strong>in</strong> a given situation. Documented <strong>in</strong>stream flow needsof priority aquatic environments are available <strong>in</strong> much of <strong>the</strong> bas<strong>in</strong>.3<strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>

Experience Across<strong>the</strong> WestAcross <strong>the</strong> West, water from both agricultural andmunicipal water efficiency ef<strong>for</strong>ts has been usedto improve <strong>in</strong>stream flows, often <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ationwith o<strong>the</strong>r water management ef<strong>for</strong>ts. Cases fromaround <strong>the</strong> West show that while an external legal orregulatory driver, or anticipation of one, can promptaction, cooperation can multiply benefits and aidsuccess. <strong>Water</strong> efficiency is often just one part of <strong>the</strong>water management package. Fund<strong>in</strong>g often requirescreativity and multiple sources. Location and scaleof projects vary; successful projects come <strong>in</strong> all sizesfrom rural headwaters <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g just two partners tomajor stream stretches <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g many parties.The Legal Sett<strong>in</strong>gIt is possible to apply water from efficiency ef<strong>for</strong>ts toenhance <strong>in</strong>stream flows <strong>in</strong> each Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>state, but opportunities and legal protections aregreater <strong>in</strong> some states than <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs. A wide arrayof federal and state programs can also affect watermanagement decisions <strong>in</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle stream as well asacross <strong>the</strong> Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>, <strong>for</strong>m<strong>in</strong>g a difficultweb to navigate.The ChallengesA wide range and diversity of challenges arise whenpeople from <strong>the</strong> Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong> contemplateus<strong>in</strong>g water from water efficiency ef<strong>for</strong>ts to helpimprove <strong>in</strong>stream flows. And <strong>the</strong> obstacles are many:legal, <strong>in</strong>stitutional and motivational, economic, andphysical.The traditional characteristics of <strong>the</strong> prior appropriationsystem of water allocation can appear to be a<strong>for</strong>midable barrier, particularly procedures associatedwith protection of o<strong>the</strong>r water right holders and <strong>the</strong>concept of “use it or lose it.” For some, <strong>the</strong> biggestconcern is potential impairment of exist<strong>in</strong>g waterrights because of <strong>the</strong> complex <strong>in</strong>teractions betweenwater uses. Polarized water <strong>in</strong>terests exist <strong>in</strong> manyareas. Fear, uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty, and a lack of trust can dom<strong>in</strong>ateconversations about improved water efficiencyand <strong>the</strong> use of any result<strong>in</strong>g water.For o<strong>the</strong>rs, <strong>the</strong> biggest question concerns who willpay <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>se ef<strong>for</strong>ts. A disconnect <strong>in</strong> costs, benefits,and impacts <strong>in</strong>hibits action. The tim<strong>in</strong>g and locationof <strong>in</strong>stream flow needs may not match <strong>the</strong> water thatcan be made available. Similarly, follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> physicaldrop of water may show that greater water efficiencydoes not result <strong>in</strong> additional water <strong>in</strong> a particular situation.And s<strong>in</strong>ce all <strong>in</strong>dividual ef<strong>for</strong>ts take place <strong>in</strong> abas<strong>in</strong> context, un<strong>in</strong>tended consequences may result.Incentives and StrategiesYet many of <strong>the</strong>se apparently pervasive challenges canbe cooperatively addressed on a local or watershedbasis, particularly <strong>in</strong> cooperation with o<strong>the</strong>rs. Thecontext is different <strong>in</strong> each case: <strong>the</strong> parties, <strong>the</strong> needs,<strong>the</strong> concerns, and more. As a result, <strong>the</strong> approach willvary <strong>for</strong> each situation. As different <strong>in</strong>centives motivatedifferent types of will<strong>in</strong>g partners, it is important toidentify <strong>the</strong> challenges <strong>in</strong> a particular situation andconsciously f<strong>in</strong>d ways to address and even leverage<strong>the</strong>m.Attitude, trust, and will<strong>in</strong>gness are <strong>the</strong> most importantkeys to success. These can counteract polarization,attitudes, and lack of motivation. Partnerships arekey <strong>for</strong> action—one water right holder can’t do thisalone—and leadership is key to partnerships.Initial motivation often comes from outside events,such as anticipated Endangered Species Act actions.While money can really motivate, it is not <strong>the</strong> only, oroften <strong>the</strong> primary, factor. Motivations to take action<strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>4

can transcend money—“green” values, water basedrecreation <strong>in</strong>terests, vista preservation, a sense oflegacy <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> future.While it is more difficult <strong>in</strong> some Colorado Riverbas<strong>in</strong> states than <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs, it is possible to l<strong>in</strong>k waterresult<strong>in</strong>g from efficiency measures to streamflowimprovement <strong>in</strong> each state. Where conserved watercan be protected from <strong>for</strong>feiture or transferred to an<strong>in</strong>stream flow use and protected from o<strong>the</strong>r waterusers, <strong>the</strong>re is greater <strong>in</strong>centive to l<strong>in</strong>k efficiency andflow. It is important to dist<strong>in</strong>guish between what<strong>the</strong> law allows and <strong>the</strong> perception of what is legallypossible. Clarify<strong>in</strong>g this can be an important strategy<strong>in</strong> foster<strong>in</strong>g this l<strong>in</strong>k.Promis<strong>in</strong>g OpportunitiesPractical possibilities <strong>for</strong> l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water efficiencyef<strong>for</strong>ts and <strong>in</strong>stream flows exist with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> current<strong>in</strong>stitutional context of <strong>the</strong> Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>.Given a stream stretch with a clearly identified need<strong>for</strong> improved <strong>in</strong>stream flows and a realistic opportunity<strong>for</strong> improv<strong>in</strong>g water efficiency, will<strong>in</strong>g partnersgenerally can build <strong>the</strong> bridges needed to overcomeo<strong>the</strong>r challenges. Creative fund<strong>in</strong>g, a def<strong>in</strong>ed legalpath, and short-term or pilot ef<strong>for</strong>ts are o<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>dicators of likely success.With a champion or catalyst, will<strong>in</strong>g partners, anda locally tailored approach, more efficient wateruse can be l<strong>in</strong>ked to improved <strong>in</strong>stream flows <strong>in</strong>areas of <strong>the</strong> Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>. To <strong>for</strong>ge this l<strong>in</strong>kon <strong>the</strong> practical level, <strong>in</strong>centives and approach arebest designed separately <strong>for</strong> each specific situation.Different <strong>in</strong>centives tailored to motivate various typesof will<strong>in</strong>g partners are required: <strong>for</strong> communities,water suppliers, agricultural water districts, farmersand ranchers, nonprofit organizations, governmentpartners, and o<strong>the</strong>rs.Nonprofits and government agencies can chooseto beg<strong>in</strong> short term ef<strong>for</strong>ts that set <strong>the</strong> stage <strong>for</strong>local action, and streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>k between local<strong>in</strong>stream flow needs and water efficiency ef<strong>for</strong>ts.These ef<strong>for</strong>ts can work squarely with<strong>in</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>stitutions.Opportunities can take <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>m of:An upstream farmer or rancher work<strong>in</strong>g witha nonprofit with an <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> streamflowprotection;A community with a direct connection to a streamstretch;An agricultural district seek<strong>in</strong>g to modernize itswater management systems <strong>in</strong> a way that can alsoreduce or relocate diversions from a river;Three-way arrangements <strong>for</strong> water use, such astrades among agriculture, streamflow, and a statefish and wildlife agency;A nonprofit with strong local relationships will<strong>in</strong>gto take <strong>the</strong> lead; andMultiple partners collaborat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a stream stretchto anticipate an upcom<strong>in</strong>g environmental need,whe<strong>the</strong>r physical or regulatory.5 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>

OverviewThroughout <strong>the</strong> Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>, wi<strong>the</strong>ver-expand<strong>in</strong>g demands <strong>for</strong> multiple wateruses and <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly uncerta<strong>in</strong> supply, anypromis<strong>in</strong>g opportunity to do more with lesswill allow <strong>the</strong> many uses that <strong>the</strong> river supports tocont<strong>in</strong>ue. The importance of healthy <strong>in</strong>stream flows,as one of <strong>the</strong>se uses, is more press<strong>in</strong>g than ever.Improved water efficiency can <strong>in</strong> concept help stretchwater supplies and contribute to better protection ofaquatic environments and <strong>the</strong> resources and servicesthat <strong>the</strong>y provide.Much is already known about how to achieve greaterwater efficiencies <strong>in</strong> urban and agricultural wateruse <strong>in</strong> a given situation. Documented <strong>in</strong>stream flowneeds <strong>for</strong> priority aquatic environments are identified<strong>in</strong> much of <strong>the</strong> Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>. But address<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong>se needs with water made available throughwater efficiency programs has not been adoptedas a ready, common solution, ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> bas<strong>in</strong> orelsewhere.The Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>, a watershed of 246,000square miles, poses perhaps <strong>the</strong> greatest watermanagement challenges of any river bas<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>nation: water demand exceed<strong>in</strong>g supply, valued butfragile ecosystems, and support <strong>for</strong> nearly every typeof water-relevant <strong>in</strong>terest. <strong>Water</strong> must serve multiplepurposes as it travels from headwaters at high mounta<strong>in</strong>elevations to <strong>the</strong> delta at <strong>the</strong> Gulf of Cali<strong>for</strong>nia.Millions make use of Colorado River water resources,many of <strong>the</strong>m outside <strong>the</strong> physical boundaries of<strong>the</strong> bas<strong>in</strong>. Uses range from water <strong>for</strong> agriculture andrangelands, residential and commercial development,<strong>in</strong>dustrial manufactur<strong>in</strong>g, m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, energy production,and Native American communities, to ecosystemservices <strong>for</strong> water-dependent recreation and tourism,endangered and o<strong>the</strong>r water-dependent species,wetland health, water quality, broader ecosystemhealth, and more.Over <strong>the</strong> past few years, a wide range of groupshas called <strong>for</strong> <strong>in</strong>novation <strong>in</strong> address<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se oftenconflict<strong>in</strong>g water uses. Build<strong>in</strong>g on this urgent appealled to this one-year survey project to explore <strong>the</strong>practical l<strong>in</strong>k between water efficiency programs andimproved <strong>in</strong>stream flows <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>.Project partners Alliance <strong>for</strong> <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong>,Environmental Law Institute and American Rivers eachbr<strong>in</strong>g a different perspective and expertise to thisissue—water efficiency, western water law, and riverprotection. We posed several questions:1. What is <strong>the</strong> practical experience <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> westernU.S. <strong>in</strong> achiev<strong>in</strong>g greater water efficiencies andutiliz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> result<strong>in</strong>g water <strong>for</strong> <strong>in</strong>stream flows,and what lessons can we apply to <strong>the</strong> uniquecharacteristics of <strong>the</strong> Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>?2. What is <strong>the</strong> legal sett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> each bas<strong>in</strong> state <strong>for</strong>apply<strong>in</strong>g conserved water to <strong>in</strong>stream purposes?3. What are <strong>the</strong> practical challenges to us<strong>in</strong>g waterefficiency programs to improve <strong>in</strong>stream flows <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>?4. What are <strong>the</strong> most promis<strong>in</strong>g on-<strong>the</strong>-groundopportunities—<strong>in</strong>centives and strategies,characteristics of success, and approaches topartnership—<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> bas<strong>in</strong>?This report summarizes what we found. In brief, practicalpossibilities <strong>for</strong> l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water efficiency ef<strong>for</strong>tsand <strong>in</strong>stream flows exist with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> current contextof <strong>the</strong> Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>. Given a stream stretchwith a clearly identified need <strong>for</strong> improved <strong>in</strong>streamflows and a realistic opportunity <strong>for</strong> improv<strong>in</strong>g waterefficiency, will<strong>in</strong>g partners generally can build <strong>the</strong>bridges needed to overcome o<strong>the</strong>r challenges.About This ReportThis report is a practical assessment, present<strong>in</strong>goptions <strong>for</strong> localized action, not a firm set of policyrecommendations. It is <strong>in</strong>tended <strong>for</strong> a diverse audience,but may be most useful <strong>for</strong> municipal andagricultural water agencies and utilities, state andfederal water policy decision makers, and nonprofitorganizations work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> water policy and waterresources management <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> bas<strong>in</strong>.This report first highlights current municipal andagricultural water efficiency ef<strong>for</strong>ts, to illustrate<strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>6

The Colorado River Bas<strong>in</strong>7 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>

<strong>the</strong> range of common practice and identify whatworks and what doesn’t, regardless of <strong>the</strong> purpose<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>se ef<strong>for</strong>ts. It also summarizes availability of<strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation about high-priority streamflow needs <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> bas<strong>in</strong>. This report uses a very broad concept of“water use efficiency” and “water conservation” s<strong>in</strong>ce<strong>the</strong>se terms are def<strong>in</strong>ed differently across states andcontexts.Six case studies follow <strong>in</strong> Chapter 2, drawn fromover 40 candidate examples documented by <strong>the</strong>project team, to illustrate <strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>k between waterefficiency programs and improved <strong>in</strong>stream flowsaround <strong>the</strong> West. Lessons are drawn from this rangeof experience, based on personal <strong>in</strong>terviews withthose <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> highlighted cases, and availablematerials. Chapter 3 presents an analysis of <strong>the</strong>law relevant to us<strong>in</strong>g conserved water <strong>for</strong> <strong>in</strong>streampurposes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> bas<strong>in</strong>.The challenges and <strong>in</strong>centives—legal, <strong>in</strong>stitutionaland motivational, economic and f<strong>in</strong>ancial, physicaland environmental, and water use—to l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g moreefficient water use and improved streamflows <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> bas<strong>in</strong> are presented <strong>in</strong> Chapter 4. These weredeveloped from over 60 <strong>in</strong>terviews of knowledgeable<strong>in</strong>dividuals throughout <strong>the</strong> bas<strong>in</strong> and <strong>the</strong> West,along with a one-day work<strong>in</strong>g session of selectedbas<strong>in</strong> experts. The promis<strong>in</strong>g opportunities identified,<strong>in</strong> terms of both characteristics of success andpromis<strong>in</strong>g approaches, are <strong>the</strong> result of analysis andsyn<strong>the</strong>sis of all this <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation.While <strong>the</strong> focus is on local, practical opportunitieswith will<strong>in</strong>g partners with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g bas<strong>in</strong>context, we also <strong>in</strong>clude what we heard about howstates and nonprofits can potentially set <strong>the</strong> stage<strong>for</strong> more local activities. Separate Resource Sectionscontributed by water efficiency experts lead <strong>the</strong>reader to more <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation on state level waterefficiency <strong>in</strong>itiatives and examples of currentexperience with municipal and agricultural waterefficiency programs.More Efficient <strong>Water</strong> Use:Common <strong>Practice</strong>Many communities, agricultural water districts,farmers and <strong>in</strong>dustries across <strong>the</strong> U.S. have significantexperience <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> efficiency of <strong>the</strong>ir wateruse to meet a variety of water supply and environmentalchallenges. Much is already known about howto achieve <strong>the</strong>se greater water use efficiencies, <strong>the</strong>range of successful practices, and what’s best <strong>in</strong> agiven municipal or agricultural situation.Municipal <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong>Many municipalities throughout <strong>the</strong> U.S. face a widerange of water supply and water resource challenges.This is particularly true <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> arid West and among<strong>the</strong> states withdraw<strong>in</strong>g water from <strong>the</strong> ColoradoRiver, where environmental concerns are prom<strong>in</strong>entand limited water resources are already spread th<strong>in</strong>.Even when a municipality has sufficient freshwaterresources to meet present needs, <strong>for</strong>ecasts may reveala future demand that grows beyond an exist<strong>in</strong>g andperhaps less reliable supply. This imbalance can bepartly or fully addressed through water demand managementstrategies such as water efficiency programs,which are often also called water conservation programseven though <strong>the</strong> terms are technically different.<strong>Water</strong> “efficiency” refers to <strong>the</strong> efficient flow rateof a fixture or device, such as a showerhead; water“conservation” refers to <strong>the</strong> behavior of <strong>the</strong> customerthat is us<strong>in</strong>g that efficient device, as <strong>in</strong> tak<strong>in</strong>g shortershowers. However, at <strong>the</strong> municipal program level, <strong>the</strong>terms are usually used <strong>in</strong>terchangeably.<strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>8

Municipal water efficiency programs are a successfulway to deal with a wide variety of needs, and ourcollective experience with <strong>the</strong>m spans over threedecades. Typically most water utilities first targetresidential customer end uses such as toilet flush<strong>in</strong>g,clo<strong>the</strong>s wash<strong>in</strong>g, shower<strong>in</strong>g, faucet use, lawn irrigation,and o<strong>the</strong>r outdoor water use. <strong>Water</strong> efficiencyprograms are also designed to target specificproblems <strong>in</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g consumer demand: commercialand <strong>in</strong>dustrial water use, peak season demandand <strong>the</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g phenomenon of outdoor wateruse, or leakage <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> water delivery system itself.Municipalities and <strong>the</strong>ir water utilities usually employeducation and outreach programs, ord<strong>in</strong>ances, andconservation rate structures as part of <strong>the</strong>ir ef<strong>for</strong>ts.Motivations beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> implementation of efficiencyprograms vary, but two common reasons are tofacilitate population and economic growth withoutgreatly <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> need <strong>for</strong> new or expandedwater supplies and to avoid <strong>in</strong>frastructure expansionprojects such as build<strong>in</strong>g new treatment and storagefacilities <strong>for</strong> water supply or wastewater. In addition,environmental concerns and state regulatoryrequirements can be driv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong>ces beh<strong>in</strong>d waterefficiency programs. And it’s worth not<strong>in</strong>g that just asmotivations <strong>for</strong> undertak<strong>in</strong>g water efficiency ef<strong>for</strong>tsdiffer, so do <strong>the</strong> results, <strong>in</strong> terms of reduced surfaceor groundwater withdrawals, <strong>the</strong> balance of watersupply sources <strong>for</strong> a specific water utility, and <strong>the</strong>impact on streamflows.Target<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Most Cost-EffectiveStrategiesHow do water utilities target specific end uses andreduce water consumption <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir service area? Theycan undertake active water efficiency programs,conduct education and outreach activities, and adoptord<strong>in</strong>ances affect<strong>in</strong>g specific water uses. One of <strong>the</strong>most popular efficiency program strategies <strong>for</strong> waterutilities is <strong>the</strong> product rebate. Customers are givena monetary <strong>in</strong>centive <strong>for</strong> purchas<strong>in</strong>g an efficienttoilet, showerhead, clo<strong>the</strong>s washer, smart irrigationcontroller, or o<strong>the</strong>r water us<strong>in</strong>g device. Sometimeswater utilities offer a direct <strong>in</strong>stallation program; or <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> case of toilets or irrigation systems, may require alicensed plumber or contractor to conduct <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>stallation.This <strong>in</strong>sures <strong>the</strong> device is <strong>in</strong>stalled properlyand will per<strong>for</strong>m as it should. Site surveys or auditsare also used to identify water sav<strong>in</strong>g opportunities.It is a great way to engage customers, and is veryeffective <strong>in</strong> commercial and <strong>in</strong>dustrial applicationsdue to <strong>the</strong> great variations <strong>in</strong> water use <strong>in</strong> thosesectors.Methodical plann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> water efficiency programs isessential. This process is outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> diagram on<strong>the</strong> next page. It is important that a water utility havean accurate understand<strong>in</strong>g of its supply situation,how its customers use water, and how both of <strong>the</strong>seth<strong>in</strong>gs will change <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> future. When <strong>the</strong> need <strong>for</strong>efficiency programs is documented and understood,targets and goals can be made. Follow<strong>in</strong>g this,conservation measures that are suitable <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>service area can be identified and evaluated. At <strong>the</strong>core of <strong>the</strong> evaluation process is <strong>the</strong> benefit-costanalysis, where <strong>the</strong> designed programs are evaluatedto ensure that <strong>the</strong>y will save a unit of water moreeconomically than it can be purchased or producedthrough new supply creation. One exception to thisrule is <strong>the</strong> water efficiency education and outreachprogram. While <strong>the</strong> sav<strong>in</strong>gs attributable to <strong>the</strong>sespecific programs are difficult to separate out fromo<strong>the</strong>r program ef<strong>for</strong>ts, educat<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>gwith <strong>the</strong> community is <strong>the</strong> backbone of any waterefficiency portfolio.Successful Municipal ProgramsResource Section 1 details successful municipalwater efficiency programs from 18 communities <strong>in</strong> 11states coast to coast. These examples illustrate whatis possible, and <strong>in</strong>deed practical, among municipalities.These can be used as a reference to identifyand understand <strong>the</strong> wide range and diversity of bestpractices <strong>in</strong> urban water efficiency, associated costsand sav<strong>in</strong>gs, and <strong>the</strong> types of communities that haveundertaken water efficiency ef<strong>for</strong>ts. In<strong>for</strong>mation onprogram offer<strong>in</strong>gs and reported water sav<strong>in</strong>gs wasdrawn primarily from each utility’s own website andpr<strong>in</strong>ted materials. Programs target mostly residentialcustomers, unless o<strong>the</strong>rwise noted.In order to assist municipalities <strong>in</strong> plann<strong>in</strong>gcost-effective water conservation programs, AWEdeveloped a specialized model. The AWE <strong>Water</strong>Conservation Track<strong>in</strong>g Tool is an Excel-based modelthat can be used to evaluate <strong>the</strong> water sav<strong>in</strong>gs, costs,and benefits of municipal conservation programs.Resource Section 2 illustrates <strong>the</strong> water efficiencyprogram plann<strong>in</strong>g process <strong>for</strong> a hypo<strong>the</strong>ticalColorado River bas<strong>in</strong> community us<strong>in</strong>g this tool.9 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>

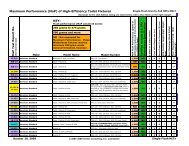

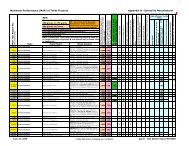

Source: AWWARF Project 2935: <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> Programs <strong>for</strong>Integrated <strong>Water</strong> Management, A&N Technical Services, Inc.It demonstrates that water utilities can plan to savea targeted amount of water and that this ef<strong>for</strong>t canbe cost effective, mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong> benefits outweigh<strong>the</strong> costs. This example provides estimated changes<strong>in</strong> service area water demand from a sample group ofwater efficiency programs and discussion regard<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> results.State Initiatives and PoliciesIn October 2009 AWE completed a review of exist<strong>in</strong>gstate-by-state municipal water efficiency requirementsand <strong>in</strong>itiatives <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> U.S. 1 In<strong>for</strong>mation from<strong>the</strong> survey <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> seven Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong> statesis appended <strong>in</strong> Resource Section 3. In summary, allof <strong>the</strong> bas<strong>in</strong> states provide technical assistance <strong>for</strong>implement<strong>in</strong>g water efficiency measures. Five of <strong>the</strong>seven states require municipal water conservationplann<strong>in</strong>g and implementation of water efficiencymeasures <strong>for</strong> water utilities. And all but one offersome <strong>for</strong>m of f<strong>in</strong>ancial assistance. In Cali<strong>for</strong>nia,both municipal water utilities and agriculturalwater districts signed agreements committ<strong>in</strong>g toimplement a suite of appropriate best managementpractices. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> time of <strong>the</strong> survey, Cali<strong>for</strong>nia hasadopted additional water conservation legislation,with a sweep<strong>in</strong>g target of 20 percent reduction <strong>in</strong>per person urban water use by 2020, with additionalrequirements <strong>for</strong> both urban and agricultural watersuppliers, which will lead to more efficient water use<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> state. 21 A summary of f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>for</strong> all 50 states is posted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> AWEResource library: http://a4we.org/water-efficiency-US.aspx.An update is planned <strong>for</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>g 2012.2 Cali<strong>for</strong>nia <strong>Water</strong> Conservation Act of 2009 (Senate Bill X7-7).<strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>10

State <strong>Water</strong> Conservation Initiatives andRequirements <strong>for</strong> Colorado Bas<strong>in</strong> States, 2009Arizona Cali<strong>for</strong>nia Colorado NevadaNewMexico Utah Wyom<strong>in</strong>gDoes <strong>the</strong> state require preparationof drought emergency plans bywater utilities or cities on any prescribedschedule?Does <strong>the</strong> state have a mandatoryplann<strong>in</strong>g requirement <strong>for</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>gwater conservation separate fromdrought emergency plans?Does <strong>the</strong> state require implementationof conservation measures aswell as preparation of plans?Does <strong>the</strong> state have <strong>the</strong> authority toapprove or reject <strong>the</strong> conservationplans?Does <strong>the</strong> state have m<strong>in</strong>imumwater efficiency standards morestr<strong>in</strong>gent than federal or nationalrequirements?Does <strong>the</strong> state regulate dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>gwater supplies and require conservationas part of its permitt<strong>in</strong>gprocess or water right permit?Does <strong>the</strong> state allow fund<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong>conservation programs under astate revolv<strong>in</strong>g fund? (dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>gwater)Does <strong>the</strong> state allow fund<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong>conservation programs under astate revolv<strong>in</strong>g fund? (wastewater)Yes Yes No Yes No No NoYes Yes Yes Yes No Yes NoYes Yes* Yes Yes No Yes NoYes Yes Yes Yes No No NoYes Yes Yes Yes No No NoYes Yes Yes No Yes No NoYes Yes Yes No Yes No YesYes Yes Yes No Yes Yes YesDoes <strong>the</strong> state offer o<strong>the</strong>r f<strong>in</strong>ancialassistance? Bonds? Appropriations?Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes NoDoes <strong>the</strong> state offer direct or<strong>in</strong>direct technical assistance?Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes YesDoes <strong>the</strong> state provide statewideET microclimate <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation?Yes Yes Yes No No No NoSource: Alliance <strong>for</strong> <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> State Survey, Oct. 2009 at http://a4we.org/water-efficiency-US.aspx* While Cali<strong>for</strong>nia does not literally require specific measures, its mandatory water use reduction goals cannot be met without action.11 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>

Agricultural <strong>Water</strong> Use<strong>Efficiency</strong>There’s great experience, and <strong>in</strong>terest, <strong>in</strong> both onfarmand delivery system water efficiency. <strong>Water</strong>use efficiencies <strong>in</strong> agriculture can be achieved bothwith ref<strong>in</strong>ed on-farm distribution practices andimprovements to district-wide water managementand delivery systems. Manag<strong>in</strong>g farm water is morethan simply water<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> crop once a week. Manyfactors <strong>in</strong>fluence how much water it takes to producea crop, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g soil type, soil sal<strong>in</strong>ity management,temperature, <strong>the</strong> delivery schedule of irrigationwater and <strong>the</strong> type of irrigation system be<strong>in</strong>g used.Variables with<strong>in</strong> each of <strong>the</strong>se factors make irrigationmanagement a challeng<strong>in</strong>g and often difficult task<strong>for</strong> farmers.How Agricultural <strong>Water</strong> Use <strong>Efficiency</strong>Differs from Municipal <strong>Water</strong>ConservationMany agricultural districts and farmers, like urbancommunities, have experience with ef<strong>for</strong>ts to usewater more efficiently or to reduce <strong>the</strong> amount ofwater that <strong>the</strong>y are consum<strong>in</strong>g. Farmers use waterto produce food and fiber <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> public to consume,much as factories might use steel to manufacturegoods. But as noted above, different factors <strong>in</strong>fluenceirrigation management and efficient agriculturalwater use. In agriculture, us<strong>in</strong>g more or less waterthan optimal can have serious consequences <strong>for</strong>production and <strong>the</strong> health of <strong>the</strong> crop.Agricultural <strong>Water</strong> Conservation<strong>Water</strong> conservation <strong>in</strong> agriculture may take <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mof changes to <strong>the</strong> characteristics of agriculturalwater supply and demand. The Agricultural <strong>Water</strong>Conservation Clear<strong>in</strong>ghouse at Colorado StateUniversity provides a broad def<strong>in</strong>ition of agriculturalwater conservation as <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g any of <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g:Increased crop water use efficiencyImproved irrigation application efficiencyIncreased capture and utilization of precipitationDecreased crop consumptive useIncreased irrigation water diversion and deliveryefficienciesReduced water use through adoption of conservationmeasures and new technologies <strong>for</strong> watermanagement 3Agricultural <strong>Water</strong> Use <strong>Efficiency</strong>There are a number of methods commonly usedto help estimate or quantify on-farm water useefficiency. One common method is to consider <strong>the</strong>amount of water it takes to produce a certa<strong>in</strong> amountof plant growth, a method often referred to as “cropper drop.”The “crop per drop” method, also known as agronomicwater use efficiency, recognizes that differentcrops serve different needs, and values <strong>the</strong> improvementof grow<strong>in</strong>g practices to ensure that farmersare match<strong>in</strong>g water use to <strong>the</strong> specific needs of <strong>the</strong>irsituation. Those needs are met through a number offactors.”Crop per drop efficiency” <strong>in</strong>cludes a factor known asdistribution uni<strong>for</strong>mity, or <strong>the</strong> uni<strong>for</strong>m distribution ofwater across an entire field. This <strong>in</strong> turn affects efficiency.A field may have different soil characteristicsfrom one end to ano<strong>the</strong>r or may not be perfectlylevel, which could reduce <strong>the</strong> potential distributionuni<strong>for</strong>mity of <strong>the</strong> irrigation water applied to <strong>the</strong> field.Low distribution uni<strong>for</strong>mity <strong>in</strong>creases water use and<strong>in</strong> some cases <strong>the</strong> energy needed to pump <strong>the</strong> waterto produce a crop.3 Agricultural <strong>Water</strong> Conservation Clear<strong>in</strong>ghouse at ColoradoState University, at http://agwaterconservation.colostate.edu/.<strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>12

available. The legal complexities result<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong>seeffects of agricultural water efficiencies are addressed<strong>in</strong> Chapter 3.Effects of improved agricultural water use efficiencyon <strong>in</strong>stream flows depend on many variables, eachhav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> potential to substantially impact <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>stream flow through <strong>the</strong>ir effects on water systemmanagement. Potential changes to water use efficiencypractices <strong>in</strong> agriculture on <strong>in</strong>stream flows mayhave un<strong>in</strong>tended consequences, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g changes <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> tim<strong>in</strong>g and volume of water <strong>in</strong>itially diverted <strong>for</strong>agriculture, <strong>the</strong> potential <strong>for</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased direct diversions<strong>for</strong> downstream use, alterations to <strong>the</strong> qualityand quantity of return flows both positive and negative,as well as potential repercussions <strong>for</strong> conjunctivegroundwater management.Practical Experience with On-Farm andDistrict <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong>Experience with both on-farm and district waterefficiency <strong>for</strong> different types of crops and differentwestern U.S. climates and soil types is extensive.Agricultural water managers can turn to severalgovernment and nonprofit sources of <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation,as well as private sector experts, such as those cited<strong>in</strong> this section. Several western states have identifiedagricultural practices <strong>for</strong> water management andefficient use. Cali<strong>for</strong>nia, <strong>for</strong> example, has adopteda list of “efficient water management practices” <strong>for</strong>water districts, while <strong>the</strong> Texas State Soil and <strong>Water</strong>Conservation Board has a guidebook on best managementpractices <strong>for</strong> both on-farm water use and <strong>for</strong>water delivery systems. 5Both <strong>the</strong> Natural Resources Conservation Service(NRCS) of <strong>the</strong> U.S. Department of Agriculture and <strong>the</strong>U.S. Bureau of Reclamation def<strong>in</strong>e and support agriculturalwater efficiency ef<strong>for</strong>ts. The NRCS Agricultural<strong>Water</strong> Enhancement Program (AWEP), part of <strong>the</strong>Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP),provides f<strong>in</strong>ancial and technical assistance to farmersto plan and implement conservation practices onagricultural land <strong>in</strong> project areas that more efficientlyuse surface and ground water and improve waterquality. The Agricultural Management Assistance(AMA) provides cost share assistance to agriculturalproducers to voluntarily <strong>in</strong>corporate new conservation5 Texas State Soil and <strong>Water</strong> Conservation Board, 2004 atwww.tsswcb.state.tx.us/files/contentimages/water_conservation_bmp.pdf.Source: Meet<strong>in</strong>g Colorado’s Future <strong>Water</strong> Supply Needs: Opportunities and Challenges Associated withPotential Agricultural <strong>Water</strong> Conservation Measures, Sept. 2008, Colorado Agricultural <strong>Water</strong> Alliance<strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>14

activities <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>ir farm<strong>in</strong>g operations, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gwater management or irrigation structures. 6 The U.S.Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) supports its west-wideand Cali<strong>for</strong>nia-specific lists of best managementpractices with two sources of technical assistanceand fund<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> implementation—<strong>the</strong> <strong>Water</strong>Conservation Field Services Program and <strong>the</strong><strong>Water</strong>SHARE ef<strong>for</strong>t. 7Non-profit, public benefit organizations also exist tohelp water suppliers and farmers improve water useefficiency. For example, <strong>in</strong> Cali<strong>for</strong>nia <strong>the</strong> Agricultural<strong>Water</strong> Management Council provides a voluntaryapproach to efficient water management practices<strong>for</strong> agricultural water suppliers and a system <strong>for</strong>determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g which practices are most likely toprovide local benefit, as well as provid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mationand resources to farmers work<strong>in</strong>g to improvewater use efficiency. 8SummaryEf<strong>for</strong>ts by agricultural water suppliers and farmersto improve water use efficiency <strong>in</strong> agriculture canbe successful but require consideration of both <strong>the</strong>possible benefits and impacts <strong>in</strong> a particular location.While <strong>the</strong> potential <strong>for</strong> improv<strong>in</strong>g agricultural wateruse efficiency to effect change on <strong>in</strong>stream flows <strong>in</strong>general is undeterm<strong>in</strong>ed, it has worked to enhancestreamflows <strong>in</strong> specific situations (see <strong>for</strong> examplecase studies <strong>in</strong> Chapter 2). Improv<strong>in</strong>g agriculturalwater use efficiency <strong>in</strong>telligently can provideopportunities to maximize water use potential whilemanag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> numerous variables that exist.Wise agricultural water use efficiency and conservationchoices will also ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> flexibility <strong>in</strong> farmers’crop selection. Farmers <strong>in</strong> irrigated regions of <strong>the</strong>western U.S. often must make annual changes to<strong>the</strong>ir cropp<strong>in</strong>g choices to respond to water availability,market demands, and o<strong>the</strong>r factors. Threeexamples of on-farm and water district efficiencyef<strong>for</strong>ts drawn from Cali<strong>for</strong>nia, contributed by <strong>the</strong>Agricultural <strong>Water</strong> Management Council, are available<strong>in</strong> Resource Section 4. These illustrate not only <strong>the</strong>range of possibilities <strong>in</strong> creatively manag<strong>in</strong>g wateruse but also provide some <strong>in</strong>dication of <strong>the</strong> range ofvariables that can be accommodated through <strong>in</strong>telligentwater use efficiency programs.<strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: How Much IsNeeded and WhenThis report does not attempt an evaluation of <strong>the</strong>highly complex science of streamflow assessment.But some po<strong>in</strong>ts are clear: not just <strong>the</strong> volume, but<strong>the</strong> tim<strong>in</strong>g, duration, variation, and location of flowsare important factors <strong>in</strong> a particular stream reach.Almost every state has its own methodologies <strong>for</strong>develop<strong>in</strong>g flow recommendations <strong>for</strong> localizedstream segments. The legal context of <strong>in</strong>stream flowrights and protections is somewhat unique <strong>in</strong> eachstate as well (see Chapter 3 beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g on page35). Several Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong> states have begunstatewide or regional ef<strong>for</strong>ts to identify streamflowneeds, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g develop<strong>in</strong>g rank<strong>in</strong>g systems to assist<strong>in</strong> identify<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> most critical stream stretches. Forpursu<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersection of water efficiency ef<strong>for</strong>tsand <strong>in</strong>stream flow needs, <strong>the</strong>se reaches and <strong>the</strong>seef<strong>for</strong>ts may be <strong>the</strong> most relevant.The Arizona Department of <strong>Water</strong> Resources f<strong>in</strong>alvolume of its state water atlas, <strong>for</strong> example, presentsa water susta<strong>in</strong>ability evaluation of Arizona water,highlight<strong>in</strong>g (or rank<strong>in</strong>g) <strong>the</strong> most important environmentalwater resources needs by geographicarea (groundwater bas<strong>in</strong>) <strong>in</strong> Arizona. 9 A separateUniversity of Arizona Environmental <strong>Water</strong> NeedsAssessment describes <strong>the</strong> geographic location and6 NRCS programs are accessed at http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/programs/.7 Agricultural <strong>Water</strong> Plann<strong>in</strong>g Guidebook, 2000, USBR athttp://www.usbr.gov/uc/progact/waterconsv/pdfs/Guidebook2000.pdf.USBR’s Mid-Pacific Region agricultural water conservationcriteria at http://www.usbr.gov/mp/watershare/documents.html.DOI’s <strong>Water</strong>SMART website features projects funded by <strong>the</strong>program at http://www.doi.gov/watersmart/html/<strong>in</strong>dex.php.8 Agricultural <strong>Water</strong> Management Council atwww.agwatercouncil.org/.A statewide Memorandum of Understand<strong>in</strong>g on agriculturalwater efficiency provides guidel<strong>in</strong>es <strong>for</strong> water managementplans and implementation of cost-effective efficient watermanagement practices. A 2009 state law sets additionalgoals <strong>for</strong> all water users, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g agriculture.9 Arizona Department of <strong>Water</strong> Resources, Arizona State<strong>Water</strong> Atlas at http://www.azwater.gov/AzDWR/StatewidePlann<strong>in</strong>g/<strong>Water</strong>Atlas/default.htm.15 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>

focus of nearly 100 studies of environmental waterneeds <strong>in</strong> Arizona, to identify environmental waterneeds <strong>for</strong> some rivers and <strong>the</strong> connection betweenwater availability and ecological health. 10State fish and game agencies have also reviewed<strong>in</strong>stream flow needs. The Wyom<strong>in</strong>g Game andFish Department five-year plan is one example. 11Cali<strong>for</strong>nia’s Fish and Game Department’s <strong>Instream</strong><strong>Flow</strong> Program develops scientific <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation on<strong>the</strong> relationships between flow and available streamhabitat, to determ<strong>in</strong>e what flows are needed toma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> healthy conditions <strong>for</strong> fish and wildlife. 12Two related ef<strong>for</strong>ts are underway <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> state ofColorado. Phase two of <strong>the</strong> Statewide <strong>Water</strong> SupplyInitiative identified environmental needs (2007). Andn<strong>in</strong>e regional roundtables (groups of stakeholders)<strong>for</strong> each sub-bas<strong>in</strong> provide <strong>in</strong>put to <strong>the</strong> State’snonconsumptive water needs assessments (bo<strong>the</strong>nvironmental and recreational water needs) <strong>for</strong>each sub-bas<strong>in</strong>. 13 Similarly, some of New Mexico’s16 locally developed regional water plans addressenvironmental water needs. 14Cali<strong>for</strong>nia is embark<strong>in</strong>g on a more complexwatershed-based approach to mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>k <strong>in</strong>one watershed (outside <strong>the</strong> Colorado River bas<strong>in</strong>)between quantifiable <strong>in</strong>stream flow objectives,water quality standards and criteria, and water rightsadm<strong>in</strong>istration. The State <strong>Water</strong> Resources ControlBoard, <strong>in</strong> consultation with Fish and Game, developeda list <strong>in</strong> late 2010 of <strong>in</strong>stream flow studies <strong>for</strong>138 rivers statewide, as required by state legislation.In August 2010 <strong>the</strong> Board adopted a flow study <strong>for</strong><strong>the</strong> Sacramento/San Joaqu<strong>in</strong> Delta ecosystem. TheBoard is now do<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> work to set flow objectives<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> San Joaqu<strong>in</strong>, focus<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> lower river; adraft is anticipated by early 2012 with flow objectives<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Delta and Sacramento River, <strong>for</strong>mal adoption,and a water rights proceed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> entire ecosystemto follow. <strong>Water</strong> users <strong>in</strong> each tributary river willneed to f<strong>in</strong>d ways to get to that target objective,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g water efficiency measures. 15A wealth of o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation is available from publicsources, <strong>for</strong> those <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> a specific location.Ma<strong>in</strong> stem Colorado River flows are driven by federalreservoir management and by endangered speciesneeds. Federal habitat conservation plans <strong>for</strong> endangeredor threatened aquatic species can identifycritical stretches. Biological op<strong>in</strong>ions and environ-mental impact statements <strong>for</strong> federally sponsoredprojects can provide reach-specific <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation. TheUpper Colorado River endangered fish recoveryprogram has compiled available technical reports <strong>for</strong>flow recommendations by river (Gunnison, etc). Andseveral states have active <strong>in</strong>stream flow programs andpolicies that secure <strong>the</strong>se flows once needs aredef<strong>in</strong>ed. One is Colorado’s <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong> Programthat obta<strong>in</strong>s and holds water rights (mostly junior)<strong>for</strong> <strong>in</strong>stream flows <strong>in</strong> specific stream stretches.10 Arizona Environmental <strong>Water</strong> Needs Assessment Report,Joanna Nadeau and Sharon B. Megdal, University of Arizona,2011 at http://ag.arizona.edu/azwater/pdfs/AZEWNA_Assessment-Mar8-flat.pdf.11 <strong>Water</strong> Management Unit Five-Year Plan 2006–2010, Wyom<strong>in</strong>gGame and Fish Department, April 2006 at http://gf.state.wy.us/downloads/pdf/Fish/5yearplan2006.pdf.12 Cali<strong>for</strong>nia Department of Fish and Game ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s a websitewith <strong>in</strong>stream flow <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation at http://www.dfg.ca.gov/water/<strong>in</strong>stream_flow_docs.html and has made recommendationson 22 priority streams at http://www.waterplan.water.ca.gov/docs/cwpu2009/0310f<strong>in</strong>al/v4c10a04_cwp2009.pdf.13 These Colorado ef<strong>for</strong>ts, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g specific reports, aredescribed at http://cwcb.state.co.us/environment/nonconsumptive-needs/Pages/ma<strong>in</strong>.aspx.Statewide <strong>in</strong>itiative reports are found at http://cwcb.state.co.us/public-<strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation/publications/Pages/StudiesReports.aspx.14 New Mexico <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation is at http://www.ose.state.nm.us/isc_regional_plans.html.15 Personal communication with Frances Spivy-Weber, Cali<strong>for</strong>nia<strong>Water</strong> Resources Control Board, August 2011. The State <strong>Water</strong>Board has regulatory authority over both water rights andwater quality; its n<strong>in</strong>e regional boards over water quality only,which <strong>in</strong>cludes <strong>in</strong>stream flow levels.<strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>16

Lessons from Experience:Cases from Around <strong>the</strong> WestAwide rang<strong>in</strong>g search <strong>for</strong> practical experience <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> western U.S. l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water efficiencyand <strong>in</strong>stream flow protection yielded over 40 candidate case studies, from <strong>in</strong>dividualon-farm water efficiency measures to major city-wide conservation programs and largescaleagricultural district efficiencies. We gave particular attention to several cases thatwe feel shed <strong>the</strong> most light on this l<strong>in</strong>k and best illustrate <strong>the</strong> range of possibilities.Along with our featured cases we describe o<strong>the</strong>r, similar ef<strong>for</strong>ts that are also <strong>in</strong>structive, among<strong>the</strong>m canal modernization projects <strong>in</strong> Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, Montana and Cali<strong>for</strong>nia; several projects ofWash<strong>in</strong>gton’s Office of <strong>the</strong> Columbia River; on-farm projects <strong>in</strong> Montana, Utah, and Idaho; andmulti-party municipal ef<strong>for</strong>ts <strong>in</strong> Cali<strong>for</strong>nia.Cedar River, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton (metropolitan Seattle)Impact of long-term municipal conservationDeschutes River Bas<strong>in</strong>, Oregon(irrigation district and municipal ef<strong>for</strong>ts)Role of <strong>the</strong> non-profitWACedar RiverManatash CreekORMTNorth Fork Blackfoot RiverGrand Valley, Colorado River, Colorado(Government High L<strong>in</strong>e Canal)Moderniz<strong>in</strong>g irrigation diversionsDeschutes River Bas<strong>in</strong>IDWYManastash Creek, Yakima River Bas<strong>in</strong>,Wash<strong>in</strong>gton (Creek Restoration Project)Impact of agricultural efficienciesRussian RiverNVUTCONorth Fork Blackfoot River, Montana(Weaver Farm)Individual on-farm ef<strong>for</strong>tsCAGrand ValleyRussian River, Cali<strong>for</strong>nia(Sonoma County <strong>Water</strong> Agency)More natural flows17 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>

While <strong>the</strong>re are many successful water efficiency programswest-wide, if a program had no l<strong>in</strong>k to <strong>in</strong>streamflow, however <strong>in</strong>direct, we did not <strong>in</strong>clude it. Likewise,we opted to focus on cases with demonstrableresults ra<strong>the</strong>r than models and policies that are as yetuntested. Appendix 1 describes our criteria and lists<strong>the</strong> cases we considered. Separate resource sectionsgive examples of successful water efficiency programsundertaken <strong>for</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r purposes.What This ExperienceTells UsSeveral lessons emerge from this wealth of experienceabout what works and what doesn’t <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>application of water efficiency ef<strong>for</strong>ts to improved<strong>in</strong>stream flows. The approach or model adapts to <strong>the</strong>situation, <strong>the</strong> participants and <strong>the</strong>ir water managementgoals. While an external legal or regulatorydriver, or anticipation of one, can prompt action,cooperation can multiply benefits and aid success.<strong>Water</strong> efficiency is often just one part of <strong>the</strong> watermanagement package. Fund<strong>in</strong>g often requirescreativity and multiple sources. Location and scaleof projects vary; successful projects come <strong>in</strong> all sizesfrom rural headwaters <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g just two partners tosignificant river stretches <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g many partners.Urban and agricultural water efficiency ef<strong>for</strong>ts arepractical and can result <strong>in</strong> water available <strong>for</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rpurposes, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stream flows.External Drivers OftenPrompt ActionFederal environmental requirements canserve as a driver of action.The Endangered Species Act (ESA) has <strong>for</strong>ced orprovided <strong>in</strong>centives <strong>for</strong> many of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>stream flowprojects that rely <strong>in</strong> part or entirely on water from<strong>in</strong>creased efficiencies. This <strong>in</strong>fluence can come fromlitigation or its threat, or from requirements ofhabitat conservation plans (HCPs) or biological op<strong>in</strong>ions.In some cases, water management actions havebeen undertaken <strong>in</strong> anticipation of such pressures.O<strong>the</strong>r federal laws that could serve as drivers <strong>in</strong>clude<strong>the</strong> Clean <strong>Water</strong> Act, Federal Power Act, FederalEnergy Regulatory Commission (FERC) relicens<strong>in</strong>gprocedures, and U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR)project authorities, though such drivers are not seen<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> cases reviewed.Cases: Many, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Grand Valley, Manastash,RussianState water rights decisions can prompt<strong>the</strong> development of a project.<strong>Water</strong> right adjudications have prompted agreementsthat <strong>in</strong>clude water conservation measures and<strong>in</strong>stream flow benefits. Some cases <strong>in</strong>volve a legalchange <strong>in</strong> water rights; o<strong>the</strong>rs occur despite suchopportunities <strong>in</strong> law not be<strong>in</strong>g available.Cases: SunnysideKey Lessons and Cases That Illustrate ThemCase External driver Fund<strong>in</strong>g Cooperation Package ScaleCedarmediumDeschutesmediumGrand Valley largeManastashsmallNorth BlackfootsmallRussianmediummajor factorfactor<strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>18

Fund<strong>in</strong>g Is Critical to SuccessFund<strong>in</strong>g often requires creativity andmultiple sources.Fund<strong>in</strong>g needs <strong>for</strong> implement<strong>in</strong>g efficiency measuresrange widely. But at least half <strong>the</strong> cases <strong>in</strong>volveseveral fund<strong>in</strong>g sources and some f<strong>in</strong>ancial creativity.<strong>Water</strong> efficiency projects often <strong>in</strong>volve upfront <strong>in</strong>vestments.When <strong>the</strong>se <strong>in</strong>vestments are not <strong>in</strong>dividuallyf<strong>in</strong>ancially rational from <strong>the</strong> water user view, waterright users often are unwill<strong>in</strong>g if not unable to absorb<strong>the</strong> entire cost. This may be especially true of agriculturaldistrict costs <strong>for</strong> technological improvements.Cases: Deschutes, Grand Valley, Columbia Bas<strong>in</strong>Project and many smaller projects such as<strong>the</strong> North Fork BlackfootFund<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> fisheries improvements can betapped <strong>for</strong> conservation.The ESA not only creates legal pressure to improveflows, but it often br<strong>in</strong>gs along a fund<strong>in</strong>g source.Cases we reviewed have tapped fund<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong>Upper Colorado Recovery Program, Bonneville PowerAdm<strong>in</strong>istration (BPA) Fish and Wildlife Program/Columbia Bas<strong>in</strong> <strong>Water</strong> Transactions Program,ESA Section 6 (habitat conservation) money,Wash<strong>in</strong>gton Department of Ecology’s ColumbiaRiver <strong>Water</strong> Management Program, and <strong>the</strong> PacificCoastal Salmon Recovery Fund. Mitigation funds<strong>in</strong>dependent of <strong>the</strong> ESA can also be used to boostflows—some BPA money goes to mitigate <strong>for</strong> speciesaffected by <strong>the</strong> federal Columbia River dams, not justfish and wildlife listed under <strong>the</strong> ESA, though <strong>the</strong>yare generally prioritized. Even fund<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> relativelysmall scale projects undertaken by non-profits cancome from fisheries mitigation funds—Montana’sClark Fork Coalition, Oregon’s Freshwater Trust, <strong>the</strong>Wash<strong>in</strong>gton <strong>Water</strong> Trust and Trout Unlimited’s (TU)<strong>Water</strong> Projects <strong>in</strong> western states all depend <strong>in</strong> parton BPA money to work with farmers on farm waterefficiencies. Though our cases did not illustratethis, potential exists <strong>in</strong> tribal settlements and FERCrelicens<strong>in</strong>g that funded <strong>in</strong>stream flow improvements<strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r sett<strong>in</strong>gs, though not necessarily from waterefficiency measures.Cases: Deschutes, Manastash, North Fork BlackfootFederal and state fund<strong>in</strong>g sources <strong>for</strong>water efficiency can assist streamflow.USBR <strong>Water</strong>SMART programs, <strong>for</strong> example, havefunded agricultural water delivery system improvements,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g more efficient district watermanagement. In some cases this has resulted <strong>in</strong>streamflow improvements, though flows are not <strong>the</strong>major focus of <strong>the</strong>se projects. O<strong>the</strong>r federal and stateprograms targeted at water efficiency ef<strong>for</strong>ts couldalso be utilized <strong>in</strong> this manner.Cases: Sunnyside, Los Mol<strong>in</strong>os, Yellowstone(all <strong>Water</strong>SMART projects)Funds can be raised with <strong>the</strong> promise offisheries or environmental improvements.The rais<strong>in</strong>g of capital to support projects thatimprove <strong>in</strong>stream flows, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g those that do itthrough water efficiency ef<strong>for</strong>ts, can have <strong>the</strong> addedbenefit of reduc<strong>in</strong>g water demand if donations are atleast <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory l<strong>in</strong>ked to actual domestic water use.In this way, environmental or fishery improvementscan promote water efficiency. Even where <strong>the</strong>re arenot ESA-listed species, it can help nonprofit groupsto raise money when <strong>the</strong>ir projects benefit rare butnon-listed fish like Bonneville cutthroat.Cases: Bonneville <strong>Water</strong> Restoration Certificates,Conserve to EnhanceCooperation Can MultiplyBenefits and Aid SuccessMultiple parties can work effectivelytoge<strong>the</strong>r.Given <strong>the</strong> complexity of some of <strong>the</strong>se projects, <strong>the</strong>various benefits that result, and <strong>the</strong> fund<strong>in</strong>g needed,<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>volvement of multiple parties <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> developmentand execution of projects can be vital andhas proved successful <strong>in</strong> a number of cases. Whilelaw and fund<strong>in</strong>g play <strong>in</strong>tegral roles <strong>in</strong> allow<strong>in</strong>g and<strong>in</strong>centiviz<strong>in</strong>g projects, little is possible without waterright holders amenable to <strong>the</strong> changes. The lessencourag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> circumstances of law and fund<strong>in</strong>g,<strong>the</strong> more critical it is to be work<strong>in</strong>g with an <strong>in</strong>terestedwater right holder.Cases: North Fork Blackfoot and similar cases,Manastash, Grand Valley, Central Oregon19 <strong>Water</strong> <strong>Efficiency</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Instream</strong> <strong>Flow</strong>: <strong>Mak<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>k</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>