Fall 2005 - Women's Health Experience

Fall 2005 - Women's Health Experience

Fall 2005 - Women's Health Experience

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

VOLUME 1 ■ NUMBER 1 ■ FALL <strong>2005</strong> A QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER FOR HEALTH CARE PROVIDERSPractical Strategies inWOMEN’S HEALTHCONTENTSUNCOVERING COMMON BUTEMBARRASSING CONDITIONSPatients are unlikely to bring upsymptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction.Mickey Karram, MD, recommendsusing questionnaires or askingpatients directly ........................1HORMONE THERAPY IN THEAFTERMATH OF THE WHIVivian M. Dickerson, MD, asks:Did the Women’s <strong>Health</strong> Initiativerepresent the patient populationmostly likely to use hormonetherapy? ..................................1OUR GOAL: IMPROVING THEHEALTH CARE OF WOMENThe Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Experience</strong>seeks to help clinicians better meetthe needs of their patients ..........2DIAGNOSTICCHALLENGETommasoFalcone, MD,discusses thediagnosis andmanagement ofendometriosispage 4PELVIC FLOORDYSFUNCTIONMickey Karram, MDAccurately diagnosing the cause ofpelvic floor dysfunction can bedifficult; the condition covers avariety of abnormalities that share symptomswith a host of other conditions.Very commonly these symptoms may notcorrelate with the anatomic abnormalitiesseen on physical examination.Making matters more difficult,many women will not initiate a discussionabout their symptoms because theyare embarrassed; believe the symptomsare a normal part of aging; or falselybelieve the only treatment is surgery,which will likely be unsuccessful.www.womenshealthexperience.comPatients need to be screenedfor pelvic floor dysfunctionTherefore, a critical stage in diagnosisrests with clinicians screening patients.<strong>Health</strong> care professionals should offerwomen questionnaires or ask themdirectly about pelvic floor dysfunction.Clinicians can then proceed with morespecific diagnosis through history, examination,and testing or refer patients tospecialists in female pelvic medicine.Pelvic floor dysfunction:An umbrella termThe term “pelvic floor dysfunction” hasbeen popularized to describe all of thefunctional and anatomic problems associatedwith one or more of the 3 systems inthe pelvic floor: the lower urinary tract,the genital system, and the lower gastrointestinaltract. Symptoms may include—but are not limited to—voiding dysfunction,evidence of tissue protrusion,page 8WHAT AREN’TYOUR PATIENTSTELLING YOU?Pelvic floor continues on page 6Simple officecystometryThis techniqueassesses a patient’sbladder capacity andthe severity of herconditionWHIWHAT DOES IT MEAN TO YOUAND YOUR PATIENTS?TheWomen’s <strong>Health</strong> Initiative (WHI) has changedhow we manage menopausal and postmenopausalpatients. We must provide initial counseling for patientswho may benefit from hormone therapy (HT), and wemust regularly revisit the risk-benefit profiles with ourpatients who are on HT. The American College ofObstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the Food andDrug Administration, and numerous other organizationsVivian M. Dickerson, MDrecommend that women take the lowest effective doseof HT for the shortest duration of time.HT and quality of lifeImportantly, ACOG guidelines state that HT should not bewithheld from women who have menopausal symptoms;severity of vasomotor symptoms is the criterion for initiatingand maintaining therapy 1 because of the profoundThis newsletter is brought to you through grants from American Medical Systems; Astellas Pharma US, Inc.;Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc.; and TAP Pharmaceutical Products, Inc.Hormone therapy continues on page 3

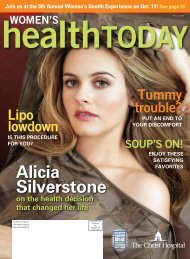

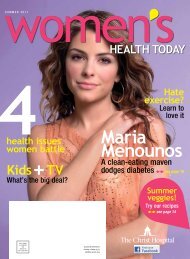

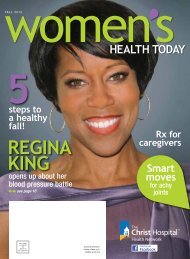

VOLUME 1 ■ NUMBER 1 ■ FALL <strong>2005</strong>Practical Strategies inWOMEN’S HEALTHPresented by the FOUNDATION FOR FEMALE HEALTH AWARENESSFounders MICKEY KARRAM, MD/MONA KARRAMNational Advisory BoardLinda Brubaker, MDProfessor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Urogynecology/Urology, LoyolaUniversity of Chicago Stritch School of Medicine; Co-Director, Women’s PelvicMedicine Center, Loyola University Medical CenterVivien K. Burt, MD, PhDAssociate Professor of Clinical Psychiatry, The David Geffen School ofMedicine at UCLA; Founder and Director, Women’s Life Center, UCLANeuropsychiatric Institute and HospitalVivian M. Dickerson, MDAssociate Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of California,Irvine, College of Medicine; Director, Division of General Obstetrics andGynecology, UCI Medical Center; Director of UCI’s Post ReproductiveWomen’s Integrative <strong>Health</strong> CenterTommaso Falcone, MDProfessor and Chairman, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics,The Cleveland Clinic Foundation; Co-director, Center for Advanced Researchin Human Reproduction and InfertilitySebastian Faro, MD, PhDClinical Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Women’s Hospital of TexasNieca Goldberg, MDAssistant Professor of Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn,New York; Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine, New York UniversitySchool of MedicineThomas Herzog, MDProfessor, Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, College of Physicians andSurgeons, Columbia University ; Director, Division of Gynecologic Oncology,Columbia University Medical Center, New YorkBarbara Levy, MDMedical Director, Women’s <strong>Health</strong> Center, St. Francis Hospital, Federal Way,Washington; Assistant Clinical Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology, YaleUniversity School of Medicine; Assistant Clinical Professor of Obstetrics andGynecology, University of Washington School of MedicineTMSenior Vice Presidents Mark Dowden, Carl C. Olsen, Robert J. Osborn, Jr.Director of Events David SmallSenior Managing Editor Kathleen OgleSenior Art Director Jonathan BernbachProduction Director Nick GiglioProduction Coordinator Heather GuzmanImage Specialist John KimCirculation Director Mary Ellen PollinaPromotion Director Jean SmithSenior Account Managers Lee Crouch, Tia DeBonAccount Manager Izabella StefnisEDITORIAL INQUIRIES: The editors invite letters, article ideas, and other inputfrom readers. Write to: Editor, Practical Strategies in Women’s <strong>Health</strong>, 110Summit Avenue, Montvale, NJ 07645; (201) 930-5862;e-mail info@womenshealthexperience.comREPRINTS: To purchase a reprint of an article, write to: Practical Strategies inWomen’s <strong>Health</strong>, Circulation, 110 Summit Avenue, Montvale, NJ 07645; (201)505-5886 or visit www.womenshealthexperience.comADVERTISING AND SPONSORSHIP INQUIRIES: Please contact Carl Olsen at(847) 559-1332 or carl.olsen@dowdenhealth.com.Practical Strategies in Women’s <strong>Health</strong> is published four times a year by Dowden<strong>Health</strong> Media, 110 Summit Avenue, Montvale, NJ 07645, in conjunction withthe Foundation for Female <strong>Health</strong> Awareness, PO Box 43028, Cincinnati, OH45243. © <strong>2005</strong> Foundation for Female <strong>Health</strong> Awareness and Dowden <strong>Health</strong>Media, Inc. All rights reserved.The opinions expressed are those of the authors and not of the editor orpublisher of Practical Strategies in Women’s <strong>Health</strong>. Physicians shouldconsult complete prescribing information before administering any of thedrugs discussed.Our goalImprove thehealth care of womenThe Foundation for Female <strong>Health</strong> Awareness is proudto announce the launch of Practical Strategies inWomen’s <strong>Health</strong>, a newsletter for healthcare providersdeveloped as part of the Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Experience</strong>,a program that educates consumers and helps cliniciansbetter meet the needs of their patients.The Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Experience</strong> comprises thefollowing components:❚ Practical Strategies in Women’s <strong>Health</strong>, the quarterlynewsletter you hold in your hands, designed to helpyou meet everyday challenges in patient care❚ Women’s <strong>Health</strong> Today, a national magazine forwomen that delivers authoritative and practical healthinformation for consumers❚ Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Experience</strong> Online, an extensiveWeb site, featuring educational information forconsumers and health care providers. Visitwww.womenshealthexperience.com❚ Hospital-sponsored regional meetings, where localphysicians present the educational portions of theprogram and health-conscious women learn aboutimportant health issuesOur National Advisory Board reviews all programmaterials to ensure that the content is accurate andunbiased and reflects the highest standards of education.We thank our sponsors—American Medical Systems,Astellas Pharma US Inc, Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc,and TAP Pharmaceutical Products Inc—for their generoussupport of the Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Experience</strong>. Revenuegenerated from the Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Experience</strong> will beused to support much needed, unbiased medical researchin various areas of women’s health.The Foundation for Female <strong>Health</strong> Awareness, inconjunction with Dowden <strong>Health</strong> Media, is very excitedabout bringing the Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Experience</strong> to you.Sincerely,Mickey Karram, MDCo-founder and DirectorFoundation for Female <strong>Health</strong> AwarenessMESSAGE FROM THE FOUNDER2 Practical Strategies in Women’s <strong>Health</strong> ❚ <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2005</strong>

EndometriosisTommaso Falcone, MDDIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENTEndometriosis is a chronic inflammatorydisease characterized bythe presence of endometrialglands and stroma in areas outside ofthe uterus. Normally found in the uterinecavity, these glands form the physiologicuterine lining that is shed andextruded each menstrual period. Someof these glands flow upward throughthe uterine tubes into the peritonealcavity and may adhere to different sitesin and around the pelvis.Normally, the body can clear theseglands from the cavity. However, if thereis a dysfunction in this peritoneal clearancemechanism or if there are intrinsicfeatures of the glands that allow them toescape clearance, these glands persist.The inflammatory response that occursmay result in scar tissue and other manifestationsof the disease.Tommaso Falcone, MD, isProfessor and Chairman, Department ofObstetrics and Gynecology, ClevelandClinic Foundation, Cleveland, Ohio. Hischapter on endometriosis will appear inConn’s Current Therapy, next year.Family history is important whenendometriosis is suspected. Severalgenetic abnormalities found in womenwith endometriosis predispose them toeither the development of the diseaseor the clinical manifestations of thedisease. Chronic exposure to environmentalpollutants is also associatedwith the development of endometriosis.Other immunologic disorders aswell as cancers seem to be increased inwomen with endometriosis.Endometriosis is one of the leadingcauses of hospital admission for noncancerousgynecologic disorders due topain, formation of cysts, and infertilityassociated with the disease.Diagnostic challengesThe primary manifestations ofendometriosis are chronic pain andinfertility. The chronic pain can presentwith constant lower abdominalpain, cyclic menstrual pain (dysmenorrhea)or pain with sexual intercourse(dyspareunia).Endometriosis is suspected inwomen with the classic symptoms.There are several challenges to a definitivediagnosis:◗ No specific blood tests candetermine if a patient hasendometriosis.◗ Imaging techniques such as ultrasoundcan detect cysts on theovary that may be fromendometriosis but do not revealeven extensive pelvic disease.◗ Sophisticated imaging technologiesmay be more sensitive todeeply infiltrating disease butcannot rule out the presence ofendometriosis.Because of these limitations, diagnosticlaparoscopy, a surgical procedurethat introduces a camera through theumbilicus, is usually required. Expertsrecommend biopsy of the lesion to confirmthe presence of endometriosis. TheAmerican Society for ReproductiveMedicine established a system to classifydisease severity from stage 1 (minimal)to stage 4 (severe). Classificationof the patient’s stage facilitates communicationamong all clinicians involvedin treating her.CASE REPORT 1Longstanding severe, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and severe dysmenorrheaPresentation and medical history. A 38-year-old woman complainsof 3 years of severe, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and severe dysmenorrhea.On a presumptive diagnosis of endometriosis, she wastreated with an oral contraceptive and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatorydrugs, which have failed to improve her condition after 1 year.Physical examination. Physical examination reveals somenodularity in the posterior cul de sac, which is consistent withendometriosis. She reports severe pain on bimanual examinationwithout any significant pelvic masses.Diagnosis. Since the patient is primarily interested in symptom relief,diagnostic laparoscopy is not initially ordered, and treatment proceedson the presumption of endometriosis based on her presentation ofclassic symptoms.Treatment and management. This patient should be sent foran ultrasound of her ovaries to check for cysts, which would be consistentwith endometriosis. In such cases, medical management is noteffective, and surgery is required.If the ultrasound reveals no cysts or indications of previous pelvicinflammatory disease, this patient has 2 options: empiric medical managementor surgery. If she chooses medical treatment, a depotgonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist should be prescribedand a follow-up appointment at 2 months should be scheduled, atwhich time effectiveness of the GnRH agonist can be assessed. If thereis improvement in symptoms within 2 months, she should continue withthe agonist for 6 months. If hypogonadal symptoms occur, norethindronecan be added, and it will also protect against bone loss. If there isno improvement in 2 months, this patient should have surgery.Alternatively, this patient could have surgery, which would probablyshow endometriosis. The extent of disease bears no correlation withthe extent of symptoms; however, the fact that she had cul de sacnodularity points to a more advanced stage. Excision requires anexperienced surgeon. Typically, two thirds of patients will respond tosurgical management. ❚4 Practical Strategies in Women’s <strong>Health</strong> ❚ <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2005</strong>

Nonoperative managementManagement of endometriosis dependson whether the patient is seekingrelief from pain or treatment forinfertility. An oral contraceptive agentand nonsteroidal anti-inflammatorydrugs (NSAIDS) are usually usedinitially to manage chronic pelvicpain, to thin the endometrial lining,and to reduce the inflammatoryresponse. No formulation is superiorto another. During this drug therapyconsideration should be given toancillary methods of pain relief suchas biofeedback, acupuncture, andphysical therapy that may help thepain syndrome. Some patients havepain relief only with medication andwill require long-term treatment.If pain persists after 2 to 3months, simple medical therapy can beconsidered a failure and more sophisticatedtreatment consisting of agentsthat suppress the menstrual cycle orsurgical treatment should be initiated.Gonadotropin releasing hormoneagonist. Gonadotropin releasing hormone(GnRH) agonists suppress themenstrual cycle and create a pseudomenopausalstate for the patient. Themedication is the most commonly usedcycle suppressant and is very effectivein relieving symptoms. However, significantside effects include hot flushesand decreased bone density. The initialtreatment cycle is usually for 6months, and recurrence of pain afterdiscontinuing the drug is quite common.A repeat treatment with the medicationis possible.Add-back therapy. When patientsare treated with a GnRH agonist for 6months or longer, norethindrone, aprogestin, should be added to preventside effects, including bone loss.Danazol. Danazol, an androgenderivative, has shown benefit in relievingsymptoms but is not as popularbecause of the side effects of weightgain and some increase of facial orbody hair. Newer forms of medicationare presently under investigation.EndometriosisDuring a menstrual period, endometrial glands,normally found in the uterine cavity, mayflow upward through the uterine tubes.Once in the abdominal cavity theymay adhere to different sites inand around the pelvis.Illustration by John W. KarapelouSurgical managementSurgical management of chronic pelvicpain is also quite effective. The procedureis performed laparoscopically byan experienced gynecologic surgeon,who ablates or excises the endometrialglands. Most studies have shown thatthe majority of patients will respond. 1,2Many patients will have recurrent symptomsthat may require further surgery.Endometriosis and infertilityEndometriosis associated with infertilityis treated somewhat differently,because cycle-suppressing drugs likeGnRH agonists will not improve fertility.Surgery can improve pregnancyrates, although not dramatically, and acouple may need to try for up to a yearto achieve a spontaneous pregnancywithout the use of fertility drugs.It the surgery fails or the surgicaloption is not acceptable because of thedelay in achieving a pregnancy, then fertilitydrugs can be used. These drugs arevery effective and have a high pregnancyrate in women in the early reproductiveyears. In vitro fertilization (IVF) is anothergood option for women withendometriosis. However, there are datato suggest that results are less in womenwith endometriosis, especially in womenwith advanced disease, than IVF resultsin women without endometriosis. 3ConclusionEndometriosis is a very commoninflammatory disease that usually causesdebilitating pain and infertility.Present pharmacologic therapy has significantrecurrence rates, and surgicalmanagement fails in a portion ofpatients as well. Ongoing research onnew medical interventions may offermore hope of long-term relief. ❚References1. Sutton CJG, Ewen SP, Whitela N, Haines P. Prospectiverandomized double blind controlled trial of laserlaparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associatedwith minimal, mild and moderate endometriosis. FertilSteril. 1994;62:696-700.2. Abbott J, Hawe J, Hunter D, Holmes M, Finn P, Garry R.Laparoscopic excision of endometriosis: a randomized,placebo controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:878-884.3. Barnhart K, Dunsmoor-Su R, Coutifaris C. Effect ofendometriosis on IVF. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:1148-1155.www.womenshealthexperience.com<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2005</strong> ❚ Practical Strategies in Women’s <strong>Health</strong> 5

PELVIC FLOORDYSFUNCTIONWHAT AREN’TYOUR PATIENTSTELLING YOU?Pelvic floor from page 1defecatory dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, and certaintypes of pelvic pain and may take such forms as:◗ Incontinence of urine or stool◗ Incomplete bladder emptying◗ Pelvic pain, including pain with intercourse;discomfort or heaviness; or pain/burning◗ Irritation from protrusion of vaginal tissue◗ Irritative bladder symptoms such as urinaryfrequency, urgency, nocturia, or dysurea◗ Pelvic pain of bladder origin◗ Difficulty evacuating stool◗ Fecal urgencyMickey Karram, MD, is Director of Urogynecology, Good SamaritanHospital, and Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of CincinnatiCollege of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio. He is Director and Co-founder of theFoundation for Female <strong>Health</strong> Awareness.The 3 most common types of pelvic floor dysfunctionencountered clinically are urinary incontinence, fecalincontinence, and pelvic organ prolapse. It is estimatedthat at least one third of adult women are significantlyaffected by at least one of these conditions.A survey by Olson et al noted that a woman who livesto be 80 years old has an 11.1% lifetime risk of undergoingan operation for incontinence or prolapse with 29%requiring a second operation. 1With the steady increase in the population of olderwomen, the national cost burden related to pelvic floordisorders is enormous regarding lost productivity,decreased quality of life and direct health care costs.The prevalence of various types of pelvic floor dysfunctionis:Urinary incontinence. Severe urinary incontinence (atleast one bout of incontinence per day) may affect asmany as 7% of women younger than age 60, as many asCASE REPORT 2Urinary frequency and urgency with bouts of urge incontinencePresentation and medical history. A 76-year-old woman reportsurinary frequency and urgency with rare bouts of urge incontinence.She also complains of some vaginal pressure and painwhen she is on her feet for prolonged periods of time. She admitsto some mild stress incontinence as well. She has had two vaginaldeliveries. She is approximately 25 years postmenopausal anddoes not use hormone therapy. During the initial interview, sheclaims that she voids in the range of 15 to 20 times per 24 hours.As a result, she is very reluctant to leave her house and has littlesocial interaction. She takes no medications that influence thelower urinary tract, she is not sexually active, and she denies anydefecatory dysfunction.Physical examination. General physical and neurologic examsyielded normal results. A review of systems is unremarkable. Pelvicexam reveals a normal-size uterus that is mobile and in the midplane.She has mild descent of the anterior and posterior vaginalwalls into the middle to lower third of the vagina when she strainsin a supine position. There is mild descent of the uterus. Grossappearance of the vaginal mucosa is consistent with urogenitalatrophy.Assessment of the pelvic floor musculature is performed byplacing two fingers in the vagina and asking the patient to contracther levator muscles at the level of the mid vagina. She is able toonly slightly contract her muscles. However, she can completelyrelax these muscles. Massage of the area as a form of biofeedbackto reacquaint her with the location of the muscle is performed, andshe is able to contract her muscles more strongly. The muscle contractionstrength is upgraded from 1/5 to 3/5. With a subjectively fullbladder the patient is asked to cough and strain, first in the supineand then in the standing position. No leakage occurs. When askedto use the toilet, she voids 175 cc. Catheterization reveals a residualof 15 cc of urine (a bladder scan may also be used for thispurpose). A urine dipstick is negative for bacteria or leukocytes.Diagnosis. This patient was diagnosed with overactive bladder(OAB) and urogenital atrophy. Most of this woman’s pressure symptomsare likely related to urogenital atrophy. Her atrophy may alsobe contributing to her irritative lower urinary tract symptoms.Treatment and management. This patient should beginbehavioral therapy in the form of timed voiding and pelvic-floorrehabilitation. An anticholinergic and local estrogen therapy shouldbe prescribed.The patient should follow up in approximately 4 to 6 weeks. Ifshe does not report significant improvement, her clinician shouldinquire about compliance with behavioral therapy and about possibleanticholinergic side effects. If she reports significant sideeffects, switching to a different pharmacologic agent may be ofbenefit. If she reports no side effects, the dosage should beincreased. If no improvement results, pharmacologic therapy maybe assumed to have failed.If symptoms of urinary frequency, urgency, or urge incontinencecontinue with no improvement, further evaluation with urodynamicsand possibly cystoscopy should be considered (see OfficeCystometry Technique, page 8).Symptoms of urogenital atrophy typically improve with localestrogen administration, which can be safely administered in awoman who still has her uterus. No more than 4 g of local estrogencream should be applied each week. Up to 6 weeks of treatmentmay be necessary before any significant improvement occurs.If the patient continues to have OAB symptoms on this therapeuticregimen, then neuromodulation (placement of an interstimdevice) could be considered. ❚6 Practical Strategies in Women’s <strong>Health</strong> ❚ <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2005</strong>

14% of women between the ages of 60 and 85 years, and Treatment options17% of women 85 years or older. 2,3Nonsurgical management. Nonsurgical managementWhen defined as any leakage of urine in a woman, the begins with education and behavioral modification, suchprevalence is much higher, between 20% and 45%. 3,4 as timed voiding and exercises to strengthen, retrain, andDefecatory dysfunction. As it relates to the pelvic floor, relax the muscles of the pelvic floor. Local estrogen anddefecatory dysfunction most commonly takes the form of certain medications for overactive bladder may befecal incontinence or outlet obstruction secondary to a rectocele.The prevalence of fecal incontinence has been na, can be offered to women with symptomatic prolapseprescribed. A pessary, or small device inserted in the vagi-reported in the range of 10% for women older than age 50 who want to avoid surgery.and as high as 50% in women who are in tertiary care Surgical intervention. Surgical intervention includes afacilities or nursing homes. 5variety of anti-incontinent and reconstructive procedures.As previously mentioned, Olsen et al studied aPelvic organ prolapse. Few studies evaluate the prevalenceof pelvic organ prolapse. In one study, 497 women population in a managed care facility and extrapolatedscheduled for routine gynecologic care were examined for that a US-born woman has an 11% lifetime risk ofprolapse based on a standardized grading system. These undergoing surgery for prolapse and/or incontinence byinvestigators noted that 51% of the women had stage 2 or the age of 80. Sixty-one percent of these surgeries werestage 3 pelvic organ prolapse. 6 done for prolapse with or without incontinence, givingPelvic floor continues on page 8CASE REPORT 3Symptoms of stress incontinenceand asymptomatic uterine prolapsePresentation and medical history. A 35-year-old woman complains ofsymptoms of stress incontinence. A mother of 3, she exercises frequentlybut wears a pad during physical activity. She denies significant frequency,urgency, or nocturia. She voids approximately 8 times per 24 hours. Shehas no pertinent past medical history and is taking no medications.Physical examination. General physical and neurologic exams yieldedresults within normal limits. When she strains in a standing position, thereis mild descent of the uterus and anterior vaginal wall descending to justinside the hymen. She readily demonstrates the sign of stress incontinenceas she leaks urine when asked to cough in the supine position.She voids to completion and results of her urinalysis are negative.Assessment of her pelvic floor reveals her pelvic muscle strength to be5/5. She is very interested in discussing the most definitive therapy forher problem.Diagnosis. This woman most likely has straightforward stress incontinence.At a minimum, the clinician should document the sign of stressincontinence prior to discussing surgical options. Office cystometry willassess the patient’s bladder capacity and subjectively assess the severityof her condition (see Office Cystometry Technique, page 8). Full urodynamicassessment could be performed, which will most likely involve subtractedcystometry and urethral function tests.Treatment and management. If the patient chooses an anti-incontinenceprocedure, the next consideration is the asymptomatic prolapse.Some procedures will not alter the vaginal axis (ie, a synthetic midurethralsling). If one of these is selected, it may be prudent to ignore the prolapse.However, if a suspension at the level of the bladder neck via retropubicrepair or a traditional proximal sling is performed, the vaginal axis may bealtered, potentially worsening the prolapse. This should be discussed withthe patient, and the surgeon should individualize treatment. ❚CODING TIPSScreening for pelvicfloor dysfunction❚ If pelvic floor dysfunction is suspected, a followupvisit should be scheduled for a more specificdiagnosis. If the consultation is performedappropriately, a Code 99244 consult can bebilled. Medicare reimbursement for this is$168.39, based on Midwest reimbursements.This coding requires approximately 60 minutesof face-to-face time with the patient.Reimbursement has very specific requirementsthat must be fulfilled and should be reviewed inadvance by the clinician.❚ A simple cystometrogram requiring only a red,rubber catheter, asepto syringe and water iscoded as 51725 (see Office Cystometry Technique,page 8). Medicare reimbursement is $261.86.❚ Neuromuscular re-education is coded 97112,which is matched with pelvic floor muscle weakness,code 728.2 with Medicare reimbursementat $28.88.❚ If only a specimen is needed, a straight catheterizationcoded at 51701 will be reimbursed at$76.59.❚ A dipstick urine sample is coded 81002, reimbursedat $3.30.❚ If a revisit is required, it usually can be billed atLevel 3, 99213 (see Medicare guidelines), whichis reimbursed at $51.03.www.womenshealthexperience.com<strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2005</strong> ❚ Practical Strategies in Women’s <strong>Health</strong> 7

PELVIC FLOORDYSFUNCTIONPelvic floor from page 7WHAT AREN’TYOUR PATIENTSTELLING YOU?women an approximate lifetime risk of 7% for prolapsesurgery. 6Surgical therapy involves a variety of reconstructiveprocedures for prolapse that can be performed vaginally,abdominally, or laparoscopically. Most incontinence proceduresthat are performed for stress incontinence can bedone in a minimally invasive fashion as an outpatientprocedure.The accompanying case studies (see pages 6 and 7)review pertinent points regarding evaluation and managementand provide practical strategies to help clinicianscritically evaluate and manage patients who may havepelvic floor dysfunction. ❚References1. Olson AL, Smith VJ, Bertstrom JO, Colling JD, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgicallymanaged pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol.1997;89:501-506.2. Samuelson EC, Arne Victor FT, Svardsudd KF. Five-year incidence and remissionrates of female urinary incontinence in a Swedish population less than 65 years old.Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:568-5743. Brown JS, Grady D, Ouslander JG, et al. Prevalence of urinary incontinence andassociated risk factors in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:66-70.4. Van Oyen H, Van Oyen P. Urinary incontinence in Belgium; prevalence, correlatesand psychosocial consequences. ACTA Clin Belg. 2002;57:207-218.5. Swithinbank LV, Donovan JL, Du Heaume JC, et al. Urinary symptoms and incontinencein women: relationships between occurrence, age, and perceived impact. BrJ Gen Pract. 1999;49:897-900.6. Swift SE. The distribution of pelvic organ support in a population of female subjectsseen for routine gynecologic health care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:272-285.Office Cystometry Technique1. The patient is asked to void in a Texas Hat and the amountvoided is recorded.2. A red rubber catheter is inserted to obtain a postvoid residual.3. While the patient remains sitting, sterile water is poured into a syringeattached to a catheter, which allows the bladder to be refilled usinggravity. The patient is asked to notify the clinician when she firstperceives a sensation, is full, and is at maximum capacity.4. It is critical that the clinician note any rises in the column of waterin the syringe during the procedure. This could indicate uninhibitedbladder contraction.5. The catheter is removed when maximum capacity is reached.6. The patient is then asked to cough, bounce on her heels, or listento running water in an attempt to reproduce and confirm reportedincontinence.www.womenshealthexperience.comIllustration by Mary K. Bryson110 Summit AvenueMontvale, NJ 07645