Download - Downbeat

Download - Downbeat

Download - Downbeat

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

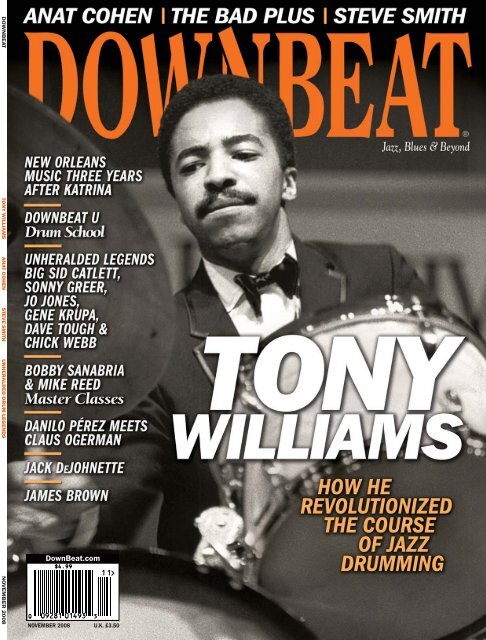

DOWNBEAT TONY WILLIAMS ANAT COHEN STEVE SMITH UNHERALDED DRUM LEGENDSNOVEMBER 2008DownBeat.comNOVEMBER 2008 U.K. £3.50

November 2008VOLUME 75 – NUMBER 11PresidentPublisherEditorAssociate EditorArt DirectorProduction AssociateBookkeeperCirculation ManagerInternKevin MaherFrank AlkyerJason KoranskyAaron CohenAra TiradoAndy WilliamsMargaret StevensKelly GrosserMary WilcopADVERTISING SALESRecord Companies & SchoolsJennifer Ruban-Gentile630-941-2030jenr@downbeat.comMusical Instruments & East Coast SchoolsRitche Deraney201-445-6260ritched@downbeat.comClassified Advertising SalesSue Mahal630-941-2030suem@downbeat.comOFFICES102 N. Haven RoadElmhurst, IL 60126–2970630-941-2030Fax: 630-941-3210www.downbeat.comeditor@downbeat.comCUSTOMER SERVICE800-554-7470service@downbeat.comCONTRIBUTORSSenior Contributors:Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard MandelAustin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago:John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer,Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana:Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, KirkSilsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis:Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring,Willard Jenkins, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, BillDouthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, JimmyKatz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Jennifer Odell, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken,Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob, KevinWhitehead; North Carolina: Robin Tolleson; Philadelphia: David Adler, ShaunBrady, Eric Fine; San Francisco: Forrest Bryant, Clayton Call, Jerry Karp, YoshiKato; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Tampa Bay: Philip Booth; Washington, D.C.:John Murph, Bill Shoemaker, Michael Wilderman; Belgium: Jos Knaepen;Canada: Greg Buium, James Hale, Diane Moon; Denmark: Jan Persson;France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Detlev Schilke, Hyou Vielz; Great Britain:Hugh Gregory, Brian Priestley; Israel: Barry Davis; Japan: Kiyoshi Koyama;Netherlands: Jaap Lüdeke; Portugal: Antonio Rubio; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu;Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert.Jack Maher, President 1970-2003John Maher, President 1950-1969SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: Send orders and address changes to: DOWNBEAT, P.O. Box 906,Elmhurst, IL 60126–0906. Inquiries: U.S.A. and Canada (800) 554-7470; Foreign (630) 941-2030.CHANGE OF ADDRESS: Please allow six weeks for your change to become effective. Whennotifying us of your new address, include current DOWNBEAT label showing old address.DOWNBEAT (ISSN 0012-5768) Volume 75, Number 11 is published monthly by Maher Publications,102 N. Haven, Elmhurst, IL 60126-3379. Copyright 2008 Maher Publications. All rights reserved.Trademark registered U.S. Patent Office. Great Britain registered trademark No. 719.407. Periodicalspostage paid at Elmhurst, IL and at additional mailing offices. Subscription rates: $34.95 for oneyear, $59.95 for two years. Foreign subscriptions rates: $56.95 for one year, $103.95 for two years.Publisher assumes no responsibility for return of unsolicited manuscripts, photos, or artwork.Nothing may be reprinted in whole or in part without written permission from publisher. Microfilmof all issues of DOWNBEAT are available from University Microfilm, 300 N. Zeeb Rd., Ann Arbor,MI 48106. MAHER PUBLICATIONS: DOWNBEAT magazine, MUSIC INC. magazine, UpBeat Daily.POSTMASTER: SEND CHANGE OF ADDRESS TO: DOWNBEAT, P.O. BOX 906, Elmhurst, IL 60126–0906.CABLE ADDRESS: DOWNBEAT (on sale October 21, 2008) MAGAZINE PUBLISHERS ASSOCIATIONÁ

DB InsideDepartments508 First Take10 Chords & Discords13 The Beat14 The ArchivesNovember 4, 197619 The Question21 Vinyl Freak22 Backstage With ...Jack DeJohnette24 Caught26 PlayersMarcus GilmoreElvin BishopJoanna PascaleAdam RudolphGene Krupa44 Tony WilliamsBridge To The Beyond | By Ken MicallefDespite being one of the most influential drummers of the 20th century,Williams never felt he got proper credit for his innovations behind the kit. Morethan 11 years have passed since he died at a far too young age. With this perspectiveof time, we focus on three albums on which he participated or led—Filles De Kilimanjaro, Believe It and Wilderness—as a guide to his musical progression,talking to drummers and collaborators about the true extent ofWilliams’ rhythmic ingenuity.DOWNBEAT ARCHIVES67 Reviews90 Transcription92 Legal Session94 Jazz on Campus98 Blindfold TestThe Bad PlusFeatures34 Anat CohenVillage AmbassadorBy Dan Ouellette38 New Orleans:Three YearsAfter KatrinaMusical Healing?By Ned Sublette4450 Chick Webb,Jo Jones, Gene Krupa,Sid Catlett, Sonny Greerand Dave ToughSix Forgotten BeatsBy John McDonough54 Steve SmithRhythm RootsBy Yoshi Kato58 Bobby Sanabria &Mike ReedMaster Classes62 Toolshed67 Uri Caine Ensemble Gunther Schuller6 DOWNBEAT November 2008Cover photography by Tom Copi; taken at a 1967 Miles Davis Quintet show.

First TakeBy Jason KoranskyTrackingWilliams’ GeniusWhile we were in production forthis issue of DownBeat, I had a discussionwith someone about TonyWilliams being on the cover. Heposed the question: “Why TonyWilliams?”Good question. Of course, theanswer could easily be, “Why not?”After all, his influence on jazzdrumming was as profound as anyartist’s over the past 50 years. But inthe feature on Page 44, we don’t celebratean anniversary of Williams’birth or death, or another significantmilestone or reissue. Rather, KenMicallef delves into a few ofWilliams’ seminal recordings, andlearns from Williams’ collaboratorsand fellow drummers about how profound animpact he had on the course of jazz.How did DownBeat cover Williams over thecourse of his career? Soon after he joined MilesDavis’ quintet, DownBeat featured him for thefirst time, including the then teenage drummer ina roundtable discussion in the magazine’s NewYork office with Art Blakey, Mel Lewis andCozy Cole, which appeared in the March 26,1964, issue.Even at this young age, Williams had anastute ability to dissect his playing, and hewas quite opinionated about the state of jazzdrumming.“When I hear the hi-hat being played on 2and 4, through every solo, through every chorus,through the whole tune, this seem to me to be—Ican’t play it like that,” he said. “Chit, chit, chit,chit—all the way through the tune. My time ison the cymbal and in my head, because when Iplay the bass drum, I play it where it meanssomething. I just put it in. When a person playsthis way, they don’t play the bass drum, theydon’t play the hi-hat—well, they say they’replaying completely free—that word is a dragtoo. What makes it different is that they don’thave any bottom.”Jump forward more than 10 years, after herecorded the milestone jazz-rock album BelieveIt. In an interview with Vernon Gibbs thatappeared in the Jan. 29, 1976, issue, Williamsdiscussed the challenges of mining new veins ofcreativity and creating his own musical identityafter his historic work with Davis.“If I felt that playing with Miles was thebest I’m ever gonna play, then I would justgive up,” he said. “The reason it came out sowell was because it was fresh; when the freshnesswears off, I have to find something else todo or else I’m not stimulated. I still think thereTony Williams:catching up onhis readingare very few people who can play jazz drums acertain kind of way. But just because of that itdoesn’t mean that I have to go out and prove itall the time because I happen to be one of thefew people who can do it on a certain reallyclassy level. It doesn’t mean that I have tospend my life being a martyr. I don’t want to bea martyr and I don’t want to be a museumpiece. I don’t want people to come out and hearme because it’s nostalgic.”The martyr language is interesting. In ourfeature this issue, Wallace Roney said thatWilliams “felt the critics never credited him forbeing the innovative jazz drummer he was.”Williams did not want his music to exist in abubble, or become a snapshot of a bygone era.In the November 1983 issue, Paul de Barrosinterviewed Williams. When asked about whatdirection his music was going, Williamsresponded, “The popular direction. I like MTV. Ilike The Police, Missing Persons, LaurieAnderson.”He then went on to discuss if jazz should getthe same institutionalized treatment as classicalmusic does in American society: “[H]ow muchis that really going to do for musicians? I don’tthink society really recognizes classical music,anyway. It’s all patronage, and grants, a certainclass of people. Jazz was originally the music ofthe people in the streets and not in concert halls,so when you lose that, you suffer the consequences.There’s nothing wrong with jazz beingan art form, but it has a certain roughness andvitality and unexpectedness that’s important. Iguess I’m old-fashioned.”Old-fashioned would probably be the lastterm one would associate with Williams. As welearn in this issue of DownBeat, his influencestill pushes today’s artists to pursue new frontiersin their music.DBDOWNBEAT ARCHIVES

Chords & DiscordsDon’t Forget ButterfieldI was surprised not to read Paul Butterfield’sname in Frank-John Hadley’s article on guitaristAmos Garrett (“Players,” September’08). Garrett came to prominence in Butterfield’sgroup Better Days 35 years ago. Thearticle also highlighted Garrett’s new focuson the music of Percy Mayfield, and led oneto believe that Garrett was unaware ofMayfield’s music until recently. Actually,Garrett is featured on the Better Days recordingof Mayfield’s “Please Send Me SomeoneTo Love” in 1973.Tom ReneyAmherst, Mass.No Reed FanReading about Ed Reed (“Players,” September’08) prompted me to buy his CD TheSong Is You. I could not even stand to getthrough one whole hearing in the car. I’mglad he cleaned up his life, but his attemptsat creative variations around the melodic linehurt the ears like nails on a chalkboard. Thisguy is no singer.Ronald SanfieldBostonGlasper Could Use DecorumI was stunned that Robert Glasper could notpick out any pianists he heard in his “BlindfoldTest,” and yet he finds a way to belittlethe playing of at least half of the artists(September ’08). This was a sad commentaryon the state of this generation’s musicians.How often does the musician not guess asingle other musician in his or her field andthen proceed to cut on their playing? Eventhough Glasper is a great pianist, he needs toget over himself.Gregoire Raymondgregoireraymond@yahoo.comWhat’s the Best Peggy Lee?John McDonough’s review of the Peggy Leereissues (“Reviews,” August ’08) was informative,but at the end of the first paragraphhe mentions that none of the recordingsreviewed are among her best. This makesme wonder: What does McDonough considerLee’s best recordings and could he sharehis opinions on them?Ari GoldbergLondonTeacher Thanks DownBeatI can’t say enough about how wonderfulDownBeat has been to make issues availableto high school students for free. Each month,I have students here at Lake Zurich HighSchool asking when the new DownBeats areMARK SHELDONConsider OrnetteI saw Ornette Coleman at the Chicago JazzFestival over Labor Day weekend and itwas like being with an all-time great at hispeak. Mainstream listeners deserve tohear a historical master at such a late ageand understand that he still gracefully createsthe shape of jazz to come. Considerputting him on the cover.Arnie LevitanSkokie, Ill.going to arrive. Your articles support myemphasis on jazz history, listening and practicingthrough interviews with pros and articlesabout the legends. Not only that, bybeing on top of all the most progressivemusicians, my students know where to lookfor inspiration and who to go hear when theycome to town. Kudos to you on recognizingyour target audience for the future. Yourquality product is a wonderful supplement tothe education that is happening in thetrenches.Josh ThompsonLake Zurich, Ill.Remembering Bobby DurhamI was sad to note the passing of drummerBobby Durham (“The Beat,” September ’08).As trombonist Al Grey’s partner, I would liketo add that Bobby was also a longtime drummerin Al’s quintet in clubs and cruises.Rosalie SoladarScottsdale, Ariz.Have a chord or discord? E-mail us at editor@downbeat.com.

the first A&R chief for A&M, was visiting theNew York offices of Helios Music, a song publishingcompany, trolling for new material.A German native of a small border town nowpart of Poland, Ogerman moved to New York in1959. When Creed Taylor brought Ogerman toVerve as musical director in 1963, his orchestralarranging and conducting gigs included writingcharts for Getz, Connie Francis, WesMontgomery, Oscar Peterson and Kai Winding.Seminal pairings in 1967 with Jobim and Sinatracemented his reputation even further.“A guy wearing an elegant looking suitwalked in, and one of the songwriters asked if Iwanted to meet the boss and introduced me toClaus,” LiPuma said. “I was astounded, becauseI knew that Claus was a famous arranger andhad worked on two records I loved, AntonioCarlos Jobim’s Composer Of Desafinado, Playsand Bill Evans’ With Symphony Orchestra. Isensed I’d found a kindred spirit.”They kept up their bicoastal friendship for afew years, but busy schedules kept them apartthrough the early 1970s. After landing at WarnerBros. in 1975, LiPuma started producing a newGeorge Benson record, which called for strings.With Ogerman’s help, the resulting album,Breezin’, became a big hit, with the single “ThisMasquerade” reaching No. 1 across theBillboard pop, jazz and r&b charts and winningthe Grammy for Record of the Year. Their collaborationlater that year on Gilberto’s Amorosokicked their musical partnership into gear.With LiPuma’s connections to various artistsand with his unwavering support, Ogerman wasable to focus on his compositional gifts andother longstanding musical dream projects.Although by the mid-’70s Ogerman began tohave his own compositions recorded by artistslike Jobim and Evans, LiPuma helped spearheadalbum projects that put a spotlight on thewriting, like Gate Of Dreams, Cityscape andClaus Ogerman Featuring Michael Brecker.At the October 2007 sessions for Across TheCrystal Sea in New York, Pérez impressedOgerman so much during the rehearsals that thecomposer tweaked the scores to give the pianistmore solo space. Apprehensive beforehandbecause Ogerman delivered the music to himjust days before the recordings began, Pérezsaid being given a greater role in the projectmade him even more nervous.“It put more of a challenge on me,” Pérezsaid. “But that was fine. Claus’ music alwaysseems to be floating by, there’s no rush to it. Allthe songs were stories—he told us how much alot of the music meant to him as a kid, and thatput me into the feeling he was looking for.”Pérez notes that two tracks, “The PurpleCondor,” which is based on de Falla’s musicand opens with bassist Christian McBride andpercussionist Luis Quintero locked in a dance,and “The Saga Of Rita Joe,” from a theme byMassenet, were opened up considerably.“I’d worked with everyone in the rhythmsection, and we saw that the trick was not tooverplay, even though, for jazz musicians,there’s that temptation,” Pérez said. “WithWayne, I’ve learned that less is more, whichserved me well on Across The Crystal Sea.”Pérez added the only time Ogerman gavehim some guided instruction was on the closing“Another Autumn,” asking him to listen to arecording by Cristina Branco, the Portuguesefado singer, to appreciate the feeling of thesong’s legato notes.“Claus is so good at letting artists find themselves,”Pérez said. “On ‘The Purple Condor,’ Iwas given 100 bars to improvise on, and I’mthinking, ‘Oh, God.’ Claus’ reply was, ‘You,need this’—and on our first day of recording.”Asked to compare Shorter and Ogerman,Pérez said, “Wayne treats music as if it belongsto the galaxy, and Claus is more interested ingreen flowers and intense colors.”Bringing in Cassandra Wilson to performwas Ogerman’s idea, who said that letting theorchestra play on and on “gets tiresome.” Afterthe singer’s tracks were finished, the tapes werebrought Los Angeles and the orchestration wasrecorded in the Capitol Recording Studios’vaunted Room A. By that time, LiPuma saidthat Ogerman had decided that he was going torelinquish his top billing on the album to Pérez.“Claus, being the gentleman and smart individualthat he is, knows Danilo has more notorietythan he does, so it made sense to put thecredit for the CD on him,” LiPuma said. “Itended up being a gift.”Because the album’s rhythm, piano andvocal tracks were recorded separately from theorchestral arrangements, no one heard thealbum in its entirety until after the sessions weremixed. When he finally heard the completedalbum, Pérez said, “I understood what Claushad in mind. I just had no idea—it was so beautiful.So often when I was improvising duringthe sessions I was worried that I was taking toomany chances, maybe bumping against thestrings’ lower tones. Listening to how it cametogether was emotional.” —Thomas StaudterThe ARCHIVESForty Years of theNomadic HerdBy Herb Nolan“There is a brilliant future forbands,” Woody Hermansaid. “If we can get financialand other kinds of help fromthe record industry first,then radio and television.They invest money in a lotof projects but thus far havebeen deaf to the big bandsound. I don’t think bigbands have to be a dyingproposition. If it does happen,it will be because wewere defeated, but I don’tthink the young people comingup are going to put up with it.There’s a great deal of involvementon their part and therecord industry is stupid forignoring it.”Von Freeman:Underrated butUndauntedBy John Litweiler“Sometimes on records I wonderif I was able to get what I wasreally thinking,” Von Freemansaid. “Sometimes it might beonly eight bars or a chorus, thenthat thing would escape me. Notthat anything I’ve had to say isEarth-shaking, but some of thesehard numbers, there’s so manybeautiful ways to play, and youknow you’re missing them. Iheard that Beethoven wrote thislittle part eight times before hegot it right. Now, maybe you andI would be satisfied with the firstseven versions.”November 4,1976Albert King: True to HisType of the BluesBy Chuck Berg“Little things can make youhave the blues,” Albert Kingsaid. “You don’t have to be oldto have the blues. You live andstruggle. Even in your businessyou can have two or three blowupsand you say, ‘Why me!’And naturally, you ain’t got noup spirit. So you want to hearsome good blues music. But theblues, they’re always there. Aslong as things go OK you don’tthink about them. But when youhit that rough spot, that’s whenthey come around. So bluesmusic is going to be here along time.”DB14 DOWNBEAT November 2008

RiffsFONT Awards Smith: The Festival ofNew Trumpet Music gave IshmaelWadada Leo Smith its award of recognitionat the sixth annual installment ofthe event in Brooklyn, N.Y., on Sept. 13.Other FONT performers this year includedJeremy Pelt, Avishai Cohen andRalph Alessi. Details: fontmusic.orgBest Buy Swallows Napster: Retailchain Best Buy announced that it wouldacquire the digital download serviceNapster for $54 million on Sept. 15.Details: bestbuy.comLatin Stamp:The United StatesPostal Serviceunveiled its stampcommemorating XLatin jazz at a ceremonyat the National Postal Museumin Washington, D.C., on Sept. 8.Percussionist Candido Camero performedat the ceremony. Details: usps.govAxes Captured: Photographer RalphGibson’s black and white shots of jazz,funk and rock guitarists are on displayat the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston,through Jan. 19, 2009. The photosare also collected in the book State OfThe Axe (Yale University Press).Details: mfah.orgFame Relaunches: Fame Records,which became famous for its MuscleShoals, Ala., sound in the ’60s, hasrestarted. In its heyday, the label and itsstudio hosted such r&b stars as ArethaFranklin, Otis Redding and WilsonPickett. Along with repackaging historicrecordings, the revamped label will alsoissue new music through a distributiondeal with EMI. Details: emigroup.comRIP, Arthur Duncan: Blues singer andharmonica player Little Arthur Duncandied on Aug. 20 in Northlake, Ill., of complicationsfrom brain surgery. He was74. Duncan performed frequently in theChicago area and recorded for Delmark.LILLIAN SCHRANKMarie’sVersion ofNationalAnthemStirs UpDenverOn the final night of theDemocratic NationalConvention in Denver,as Senator Barack Obamaspoke to more than84,000 people packed inInvesco Field, singerRené Marie performedfor a much smaller audienceat the club Dazzle.While fireworks followedObama’s speech, René MarieMarie’s appearance onstage followed verbal fireworks set off eightweeks earlier when she sang the NationalAnthem at the mayor’s annual “State of theCity” address.Rather than offering the anthem in traditionalform, the singer offered the melody of the “StarSpangled Banner” blended with the words of“Lift Ev’ry Voice And Sing.”Marie had been working on this interpretationfor months. In February, the vocalist premieredher 12-minute suite “Voice Of MyBeautiful Country” that integrated “AmericaThe Beautiful,” “My Country, ’Tis Of Thee”and “Lift Ev’ry Voice And Sing” sung to themusic of “The Star Spangled Banner.” Threemonths later, she sang the concluding anthemsection of the suite at the Colorado prayer luncheonbefore government officials, includingColorado Governor Bill Ritter, to great applauseand even hugs. Two weeks after the prayer luncheon,the singer received an e-mail fromDenver Mayor John Hickenlooper’s office invitingher to sing the National Anthem at hisspeech on July 1.“There was much more pomp and circumstanceduring the speech than at the prayer luncheon,”Marie said. “When the color guard camein, I actually questioned what I was about to do. Ithought for a second and told myself to sing itstraight. At the mike, I was so scared that I juststood for a while before I decided to go aheadand sing it in the way that felt right to me.”Before too long, her version of the anthem hitthe media and became a national story. “I wasnaïve enough to think that those interviewswould present what I did and why, and then Icould move on,” she said.Instead, those following the story would readhow the singer seemingly boasted that she“pulled a switcheroonie on them.” In fact, Marienotes that the “switcheroonie” comment wasmade in passing to a photographer from one ofthe Denver daily newspapers while he was settingup his equipment.“My mother called me after reading thatcomment,” Marie said, “and asked if I had reallysaid that. I tried to explain that I didn’t mean itthe way it sounded and that I wasn’t gloating.”Gloating or not, she received more than1,500 e-mails, including death threats. From thesinger’s perspective, what she did may not havebeen politically correct, but, “I wasn’t thinkingabout it in political terms or in terms of promotingmy career. The only thing in my mind wasartistic expression.”The night before her opening performanceduring the week of the convention, Mariereceived another death threat and had a dreamof people shooting at her and coming at herwith knives. She offered to cancel her date atDazzle along with resigning from the board ofthe Colorado Coalition for the Homeless.Those suggestions were rejected. So she tookthe stage at Dazzle during the convention andsang “Voice Of My Beautiful Country” threetimes during the six sets she performed overtwo nights.“The first time I sang the song,” she said, “itleft a bitter taste in my mouth. It was like eatingsomething you like and then getting sick from it.The second time it was not so bad. And the thirdtime, it felt good to do it.”Hickenlooper said that Marie “is a remarkableand uniquely talented singer who was justmaking an artistic statement in an inappropriateplace. It took me a while to figure out was goingon. I recognized the words to ‘Lift Ev’ry VoiceAnd Sing’ and believed the National Anthemwould follow. After, I though I should havewalked up after she finished and said, ‘I can’tsing very well but let’s sing the anthem together.’That way she could have made her artisticstatement and those expecting the anthem wouldhave been satisfied.” —Norman ProvizerLUIS CATARINO16 DOWNBEAT November 2008

The QUESTION Is …By Dan OuelletteWhat jazz artistwould make thebest president?In light of this presidential season, let’splay fantasy election in the spirit ofLester “Prez” Young. But in keepingwith such historical campaigns as Dizzyfor President, Vote for Miles and Zappafor President, maybe it’s not unthinkablefor jazz musicians to seek the office.SHONNA VALESKATenor saxophonist Benny Golson: I’d elect Sonny Rollins. He loves people, lovesmusic and loves animals. He’d teach everyone about jazz. If everyone knew about andunderstood jazz, there wouldn’t be any more wars. Sonny wouldn’t have to engage inwars. If there was a problem with a country, he’d swing ’em to death.Tenor saxophonist Donny McCaslin: I’dnominate Joe Lovano for president. He’ssuch an inspiring musician on the bandstandand such a generous human beingoff the bandstand. Joe leads by example inboth areas and has a deep knowledge ofthe history of music. We need a leader whocan inspire us, who is aware of history andwho is compassionate.Drummer Willie Jones III: I’d vote for Wynton Marsalis. He’s well spoken, has a definitephilosophy and can articulate to the public. And he’s political. He’s concernedabout getting his musical philosophy out to as many people as possible, which couldbe transferred to the political arena. He’s great on a platform. My second choice wouldbe John Clayton, who’s also well spoken and has a great personality when dealing withpeople. He’s not nearly as political as Wynton, but he too has a philosophy that he articulatesto the public.Saxophonist Pee Wee Ellis: I’d vote for Sonny Rollins. He’s a fair-minded man with agreat sense of humor and fair ethics. Plus, he’s broad-minded and well rounded. Hedoesn’t just play bebop; he’s also at home with calypso and funk. My second choicewould be Herbie Hancock. He’s eclectic.Vocalist Kendra Shank: I’d vote for Charles Lloyd in hopes that his gentle soul anddeeply spiritual, healing music would bring us peace.Pianist Geri Allen: Dr. Billy Taylor would getmy vote. As a humanitarian, he personifies theoffice. He’s always been gracious and generousto all the different camps, to all the differentpeople involved in music. He’s made hugecontributions personally and has been a witnessto so many major transitions. He’d be anadvocate for voices not getting heard. He hasan open mind for music outside his owntastes. He gives all people an opportunitygiven their merit of artistry, and he has accessto far-reaching possibilities.Saxophonist J.D. Allen: I’d elect Ornette Coleman for president. If he could make 12tones agree with each other, imagine what he could do with seven continents? I’d alsoelect Branford Marsalis as vice president, simply because he’s a smart cat and can executehis ideas in any situation, and Cindy Blackman for secretary of defense becauseshe’s a powerhouse.DBGot an opinion of your own on “The Question”? E-mail us: thequestion@downbeat.com.GILDAS BOCLEJerald MillerNu Jazz LaunchesNew Methods ofDigital Distribution“Nu jazz; for a Nu era” is the audacious sloganfor Nu Jazz Entertainment, a completely digitallabel led by Jerald Miller, which is using newformats to sell traditional straightahead jazz.The label uses major online music servers, inaddition to its web site, nujazzentertainment.com, to sell audio and video performancesfor download. Miller made this decision after heobserved the pitfalls other jazz labels face andthe downturn of the retail music business.“When I came up with my idea to do NuJazz, I didn’t want to concentrate on things inthe traditional level,” Miller said. “I had to dothings that are smart, that are economical, thatdon’t sacrifice the quality of the music.”By abolishing the need for traditional retailagreements while embracing the virtual marketplace, Miller can focus on his goals of promotingthe music and careers of his label’s talent.But Miller has taken a unique approach toselling phyiscal product. Instead of CDs, artistson the label are presented through prepaid digitaldownload cards that can be sold at stores orartists’ performances.“I needed to find a way to translate digitalsales for product at artists’ gigs in the physicalformat,” Miller said. “That’s where I came outwith the concept of making all the releases availableon prepaid digital download cards. I’m thefirst jazz label doing it.”Those releases include saxophonist JimmyGreene’s The Overcomer’s Suite. Miller also hasplans to issue previously unreleased DukeEllington master recordings (Miller managedEllington’s estate in the late 1990s). Recently,Miller arranged to have Nu Jazz titles availablethrough 300 digitital download services in morethan 60 countries.“I’m seeing a significant amount of salesfrom countries that I have done no marketing into date,” Miller said. “It’s amazing that peoplego out and discover music the way they do.”—Thomas ClanceyPABLO SECCANovember 2008 DOWNBEAT 19

Griffin Played Hard,Lived QuietlyFour days after performing what would becomehis final concert, saxophonist Johnny Griffindied of a heart attack at his country home inAvailles-Limouzine, France, on July 25. He’dhad heart problems since 1993. Griffin was 80years old.“Johnny Griffin was the nicest person thatI’ve ever been around,” said drummer KennyWashington, who worked with him often overthe last 28 years. “He was always positive, to thepoint where club owners and promoters wouldtake advantage of him. In all the years I waswith him, I never saw him get mad.”Maybe that was because Griffin chose totake revenge in a characteristically gentleway—by living freely and well. In recent years,he worked when he wished and enjoyed gardeningand tending the 10-room château in theFrench countryside with his wife, Miriam, thathad been their home since 1984. It was an unexpectedand elegant outcome to a life that wouldnot likely have come to Griffin had he remainedin the United States.Born April 24, 1928, in Chicago, Griffincame of age as bebop was displacing swingin the mid and late ’40s. Known for theglancing speed and intensity of his attack,Griffin was a titan of the straightahead, musculartenor persuasion.“He had this way of abruptly lunging atthings at any moment,” said pianist MichaelWeiss, a member of Griffin’s quartet since 1987.“But he could also finish the same line with asweet lyrical melody. Griffin should be rememberednot only for his technical virtuosity, butfor how he used that technique in his overallexpression, woven into the fabric of his style.”If Griffin received perhaps too much creditfor his speed, he received too little for otherqualities.“I don’t mean to take anything away fromJohn Coltrane,” Washington said, “but whenIra Gitler coined that phrase ‘sheets of sound,’Johnny was playing like that in the early’50s—stacking chords and playing throughthe changes. Griffin is from that in-betweenera of tenor players. He was into Don Byasand Coleman Hawkins. He took a lot of whatthose great swing players had like tone—Buddy Tate, Ike Quebec and LuckyThompson—and he meshed that with bop, soyour got the best of both.”Griffin started his career in the big time at18 with Lionel Hampton, and scored his firstrecord session sitting next to Arnett Cobb onHampton’s famous “Hey Ba-Ba-Re-Bop” inDecember 1945. Another 227 sessions andconcerts would be added to his discographyover the next 60 years, during which time herecorded with fellow tenors from Cobb andJohnny Griffin at New York’sBlue Note in 2005Dexter Gordon to Coltrane and, more recently,James Carter.One of his most exciting tenor partnershipsbegan in 1960 with Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis.Picking up on the two-tenor tradition of WardellGray–Dexter Gordon and Flip Phillips–IllinoisJacquet, the pair were a study in contrasting personalitiesbut perfectly matched skills, as eachset a high bar for the other. The “Tough Tenors,”as they were called, worked on and off for thenext 25 years.After marking time playing r&b in the late’40s and a two-year stint in the army, Griffinburst onto the hard-bop scene of the mid-’50swith a vengeance, working first with Art Blakey,then Thelonious Monk, and finally a series of hisown albums between 1958 and 1963 for OrrinKeepnews’ Riverside and Milestone labels,including The Little Giant and Way Out!In 1963, Griffin’s long battle with the IRSbegan. At the same time, young critics werebeing beguiled by the new free jazz. “I though itwas all rubbish,” he told his biographer, MikeHennessey in the book The Little Giant: TheStory Of Johnny Griffin (Northway).Griffin also felt his personal life was sinking.“I was misusing my body,” he said, “drinkingtoo much and not eating right.” So he leftAmerica for Europe and would not return for 15years. “If I had stayed in America I would bedead by now,” he told Hennessey. “I was astoned zombie when I left.”In Europe, a reinvigorated Griffin found acommunity of peers. He worked with the greatClarke–Bolland Big Band, his first full band gigsince Hampton, and regained strength and confidence.In 1978 he returned to the U.S. to considerableacclaim and a series of new albums forGalaxy/Fantasy, once again for Keepnews. ButAmerica was now a place to visit, not to live. Hereturned frequently during the next 30 years, butnever permanently.“Johnny had a stroke around 2003,” Weisssaid, “and lost a considerable amount of weight.I played with him at the Blue Note in 2005 andwe thought his endurance would be a problem.But he couldn’t stop playing.”“He never wanted to depend on anybody,”Washington said. “He always had some moneystashed, so he was never under anyone’s thumb.That was a lesson for me. Grif told me to alwayskeep some scratch around so if somethingdoesn’t go right, you’re free to go home.”—John McDonoughJACK VARTOOGIAN20 DOWNBEAT November 2008

By John CorbettThe QUESTION Is …Ernie And Emilio CaceresErnie & Emilio Caceres(AUDIOPHILE, 1969)MICHAEL JACKSONIn 2003, a fetishistic little reissue wasproduced in a run of only 500 copiesof a 78-rpm 10-inch record on theParis Jazz Corner imprint. Sportingartwork by R. Crumb, it featuredmusic by the Brothers Caceres,Emilio and Ernie, recorded forBluebird in the 1930s. Aside fromcatering to the splinter group of vinylcollectors dedicated to the antiquatedformat, it offered listeners a rarechance to hear these legendary buttoo-little-known Mex-Tex jazz musiciansfrom San Antonio.Baritone saxophonist and clarinetistErnie was, of the two, far morefamous. Starting in the late ’30s, afterhe had toured extensively with thesmall band led by his violinist brotherEmilio, he played in various higher profilesettings, including the bands of BobbyHackett, Glenn Miller, Tommy Dorsey,Benny Goodman and Woody Herman.From 1949, he led his own group in NewYork. Along with the sweet early swing, herecorded in a wild array of settings duringhis productive life, from dates with EddieCondon and Sidney Bechet and intermittenttelevision gigs with the Gary MooreOrchestra to a Metronome All Stars trumpet-heavysession with Miles Davis, FatsNavarro and Dizzy Gillespie, as well asCharlie Parker. Meanwhile, family manEmilio opted to live and work close tohome in Texas.Ernie moved back to San Antonio in themid-’60s. In 1969, two years before hisdeath, he teamed up with Emilio onceagain for an LP of their old favorites,recording for the little Audiophile label,based in Mequon, Wis. It’s a wonderfulprize for those who can track it down,exploding with color, warmth and musicality—thewisdom born of experience—androllicking, mischievous, filial joy. Emilio isterrific, with nimble fingers, a gorgeous,sensuous sound and voluminous doublestopsthat recall his early love of Joe Venuti(as well as a little of Stephane Grappelli’ssugar), but also betraying a sensibility thatrecalls his heritage in norteño music. It’sbeen said that the brothers’ sound, matchinga big, unforced baritone sax with theviolin, also has its affiliations with aMexican esthetic. This may be true, but themusic is genuine swing, uncut and unambiguous.With Cliff Gillette on piano, George Pryoron bass, Curly Williams on guitar and JoeCortez, Jr., on drums, the group rompsthrough pieces they’d recorded 30 yearsprior, like “Gig In G,” updating it by switchingErnie from the original clarinet lead to alurking, supporting role on bari, with Emiliokicking heavy booty on fiddle.Harry Carney aside, there are too fewchances to hear the big sax featured in aconvincing way in swing, but one listen toErnie flutter his way through “PoorButterfly” and the possibilities becomeimmediately clear. He’s a quicksilver clarinetist,too, featured sassily on a brisk “IFound A New Baby,” but his most distinctivemark might be on the baritone. Alongwith the rosin workouts, Emilio submits aluscious romantic ballad, “Estrellita,” hisbrother joining for a joint moment of clarinetand violin.There’s nothing frumpy or out-of-dateabout this great record. It’s a family testimonial(check it out, there’s still an activeCaceres musical line in jazz): two greatmusicians toward the end of the line givinga brilliant, bear-hug of a performance. DBE-mail the Vinyl Freak: vinylfreak@downbeat.comMore than 60 years separate the first jazz recording in 1917 and the introduction of the CD in the early ’80s.In this column, DB’s Vinyl Freak unearths some of the musical gems made during this time that have yet to be reissued on CD.November 2008 DOWNBEAT 21

Joe MorrisBackstage With …By John EphlandLYN HORTONJoe Morris Steps Upfor Hartford JazzIn 2007, after 40 years producing one of thenation’s longest-running free outdoor jazzevents, bassist Paul Brown stepped down fromprogramming Monday Night Jazz (MNJ) inBushnell Park in Hartford, Conn. The timing ofthe transition was out of sync with the normalfunding cycle for the series and it was alsocrunch time for programming.Scrambling to secure funding and create anevent that would equal Brown’s vision, DanFeingold, president of the Hartford JazzSociety, led his volunteer organization towardmaking two key decisions: take a differentdirection and bring in guitarist/bassist JoeMorris as artistic director.Programming chairman Bill Sullivan metMorris in 2001 at Morris’ trio concert inHartford. He also admired the Firehouse 12series that the musician launched in NewHaven in 2005. Sullivan said that New Havenseries’ agenda was consistent with the newdirection set for MNJ 2008.For his part, Morris said he was happy tostretch the series with more daring programming.He based his choice of performers onwhat he considers the music’s quality, originality,as well as the character of the band leaderor players. Ultimately, Morris picked who hecalls, “Traditional bands with rhythm sectionswhose musicians use melody, take solos andplay with grooves.”The musicians mostly came from theNortheast so that expenses would be minimal.Matthew Shipp, whose trio performed the firstsummer gig at the 37-acre park, said thatMorris’ involvement at the festival will have asignificant impact on the series. Other performersthis summer, including saxophonist TimBerne, echoed the sentiment. Hartford reedistLee Rozie, who handled the post-concert jamsessions at Black-Eyed Sally’s, said, “Joe’sprogramming is a welcome change after yearsof stylistic predictability.”Feingold said that plans for 2009 willinclude traditional and avant-garde artists, aswell as Latin musicians. —Lyn HortonMARK SHELDONJackDeJohnetteMultidirectional drummer Jack DeJohnetteremains true to his calling. HisStandards Trio work with Keith Jarrett andGary Peacock is in its 25th year, andDeJohnette acts like an artist replicatinghimself simultaneously among his differentgroups and running his own label, GoldenBeams. But working in the trio setting iswhere DeJohnette seems to surface inmost often. This time it was one with ChickCorea and Bobby McFerrin, where theymade their last stop at the GilmoreInternational Keyboard Festival inKalamazoo, Mich., on April 26.How did this new improv trio ideacome about?I’ve been playing with Bobby for morethan 20 years, and with Chick I go evenlonger back. The shows were exciting,fun, free and creative. The idea for thetour actually came from Bobby’s sonTaylor. Bobby had done duos with Chickand me separately and Taylor suggesteddoing it as a trio. They are all a continuationof what I have always done.Is there something irresistible about playingin trio settings for you?Trios are like a pyramid, a triangle, a magicnumber. It seems to evolve for three people.My son-in-law [Ben Surman], whoadded ambient sounds and bass effects tothe Bill Frisell recording [The ElephantSleeps But Still Remembers on GoldenBeams], rounded things out. We addedJerome Harris for the live version. Bill and Ihave electronic gizmos for a full sound ofall these colors. The other combination isTrio Beyond with John Scofield and LarryGoldings, which plays Tony’s [Williams]music. When we get some time to do it,Trio Beyond will get together. It’s just sobusy. As for the Camp Meeting trio, a lotof jazz piano players like what Bruce[Hornsby] did. He went to school for jazz,so it’s not foreign to him.What’s the latest news on GoldenBeams?The most recent recording is Peace Time,which is doing some things with meditationand relaxation, music that’s workingin hospitals with patients to help soothethem. We have a dear friend in the hospitalwith a form of cancer, and she hasa copy of Peace Time to help her getthrough her treatments. We need somemusic to calm all the business in our society,that goes beyond time, where we liveright in the now.CREDITYou have a number of tours this year,with the Standards Trio, with Frisell, yourelectronica-ambient group Ripple Effect,and another new group you formedcalled The Intercontinentals.The Intercontinentals are going to do a tourin November in England. The Intercontinentalsincludes a fantastic South Africansinger named Sibongile Khumalo; she’s anopera singer who can improvise and singanything as well as any jazz vocal instrumentalistI know. Also Billy Childs, who Ihave been wanting to work with for a longtime, and Jerome. Ripple Effect came outof a collaboration with Ben, who puttogether a remix of some music I haddone. He added his father, John Surman, alongtime collaborator of mine, again withJerome Harris. There’s also an unusualvocal instrumentalist, Marlui Miranda fromBrazil. She is part Indian and is an ethnomusicologist.She uses a lot of Indian languagesand rhythms in her music. Anotherproject that will be coming out on GoldenBeams next year is the trio with JohnPatitucci and Danilo Pérez. We have anincredible empathy, and I am looking forwardto doing some touring with them. Icould go on and on with ideas for otherprojects, but I am trying to keep it realisticas to what is possible. I am blessed to be ina creative space, surrounded by creativepeople, and it feels infinite.DB22 DOWNBEAT November 2008

Temecula FestHonors JazzVeteransNestled in the hilly wine countryhalfway between LosAngeles and San Diego, Temeculahas become one of California’spremier arts destinations.Several jazz events areheld in town, and 2008’s highlightwas the fifth annual TemeculaInternational Jazz Festival,held July 10–13. The rich senseof history that pervaded theweekend was proof that jazz is atimeless art form. Veterandrummer Dick Berk, who at 18had backed Billie Holiday at Monterey, joinedsaxophonists Richie Cole and Jimmy Mulidoreto serenade the festival’s supporters at the beginningof the event.The festival’s centerpiece was a reunionperformance by legendary bandleader GeraldWilson and singer/cowboy film star HerbJeffries, who had not performed together inmore than five decades. When Jeffries decidedto head for Paris in 1947, the reins of his bandwere given to Wilson, who never looked back.TODD JENKINSHerb JeffriesNow 90, tossing and nodding his gray lion’smane, Wilson enthralled the audience with histai chi-like conducting style and boundlessenergy. Upon the 95-year-old Jeffries’ entranceonto the stage, he and Wilson were presentedwith city and county commendations. Jeffriesthen delivered a warm, charming set backed byWilson’s taut orchestra. As Jeffries’ set closedwith “Flamingo,” his 1941 hit with DukeEllington’s orchestra, the audience marveled atthe performers’ youthful spirit. —Todd JenkinsNew Orleans StarsJump-Start DemocraticFestivitiesJust before theDemocratic conventionstarted inDenver, a healthyassortment of theCrescent City’smusical stars filledthe city’s FillmoreAuditorium for theFriends of NewOrleans event onAug. 25.Beyond the serious“Heroes of theStorm” awards, performersincludedthe Meters (withIrmaThomasAllen Toussaint in place of Art Neville), andthe Voice of the Wetlands All-Stars with TabBenoit, Irma Thomas, Donald Harrison,Terence Blanchard and many others. Theartists played in various combinations, includingRandy Newman and Blanchard teaming upon Newman’s “Louisiana 1927.”—Norman ProvizerDINO PERRUCCINovember 2008 DOWNBEAT 23

%CaughtPaal Nilssen-LoveKongsberg Fest SpotlightsNorway’s Hometeam ImprovisersWhile most jazz festivals gain their reputationby programming international headliners, theKongsberg Jazz Festival, held every July in aquaint silver mining village about 90 minutesfrom Oslo, excels because it places a premiumon Norwegian artists. While this year’s event,which ran from July 2–5, had its share of bignames—Wayne Shorter’s Quartet with ImaniWinds, Roy Hargrove, Ron Carter, andSaxophone Summit with Joe Lovano, DaveLiebman and Ravi Coltrane—the most rewardingmusic was made largely by homegrown talent.One of the unspoken themes of this year’sfestival was how Norway’s also becoming alocus for international collaboration. Actshelmed by Norwegians were frequently joinedby musicians from neighboring countries likeSweden and Denmark, and as far away as theU.S., the Netherlands, Germany and France.Performing at the sepulchral Smeltehytta, arenovated smelting plant, the quartet Dans LesArbres kicked things off with a gorgeous murmur.The collective improvisations of NorwegiansChristian Wallumrød (piano), IvarGrydeland (guitar, banjo) and Ingar Zach (percussion),with French clarinetist Xavier Charles,transformed extended technique into a symphonyof muted tones and gestures. The spell wasbroken a few hours later when, at the cozyEnergiMølla club, The Fat Is Gone cleaned outeardrums with a wild and woolly free-jazzassault stoked by drummer Paal Nilssen-Love(in the first of five different projects he was partChicago-based trumpeter Orbert Davis was profoundlymoved by Nelson Mandela’s autobiography,Long Walk To Freedom, and paid compositionaltribute to the occasion of the SouthAfrican leader for his 90th birthday on July 21.Racial unity was one of Mandela’s mandates,and that ideal permeated the diverse ranks of the50-plus member Chicago Jazz Philharmonic atthe dramatic Pritzker Pavilion in Chicago’sMillennium Park for this performance. Davis,with debonair aplomb, not only composes andconducts for the CJPO, but fronts from the podiumwith burnished yet fiery trumpet blasts.Selections from his “Collective Creativity Suite”preceded the four-movement “Hope In Action”Mandela homage, attempting to balance thedemands of keeping the orchestra membersengaged in the presentation while wooing theaudience with the intimacy of non-notated jazzelements.Though many of the musiciansin the CJPO, true to Davis’boast, are adept in classical andjazz, the core jazz presence centeredon bassist Stewart Miller,drummer Ernie Adams, pianistRyan Cohan and guest saxophonistsAri Brown and ZimNgqawana, (the latter flew infrom South Africa for the event).“1,000 Questions, One Answer”boldly kicked off proceedingswith textured interplay betweenDavis’ pocket trumpet, soulfuloutpourings from the wellmatchedBrown and Ngqawanaand penetrating trills from NicoleMitchell’s piccolo.For anyone skeptical that theCJPO is an arid Third Streamof in three days), Swedish saxophonistMats Gustafsson and German firebreatherPeter Brötzmann. Initiating ashowcase for the superb SmalltownSuperjazz label, the trio ripped througha set of high-energy ebb-and-flow, witheach musician finding gambits andlicks in one another’s improvisations tomutate and stretch. The stream-of-consciousnesstrip was never less thanfluid, even if the musical flow sometimesseemed like whitewater rafting.A couple of days later the sameclub hosted a dynamic new quartet ofScandinavian upstarts—Swedishreedists Fredrik Ljungkvist and JonasKullhammar, Danish bassist Jonas Westergaardand Nilssen-Love. It was the group’s second gig,so there was an occasional lack of energy andcohesion, but when it clicked the band delivereda feverish post-bop exploration, and a clarinetsolo by Ljungkvist toward the end of the set wasso explosive that his cohorts almost seemed inawe. Kullhammar also turned up as a guest ofthe searing-hot Norwegian organ trio Jupiter,adding thick tenor lines and solos that reached alogical boiling point, always in sync with theheavy grooves.There were also some terrific performancesby young mainstays of the Norwegian scene.Pianist Morten Qvenild, joined by his In TheCountry rhythm section and Jaga Jazzist vibistAndreas Mjøs played two hours of new compositionsstartling in their minimalist beauty, butsinger Susanna Wallumrød stole the show onher two-song cameo. Jaga Jazzist trumpeterMatthias Eick played music from his new ECMalbum, The Door, during an intimate performanceat the Kongsberg Kino, articulating hisdreamy, almost pop-like melodies with a technicalprecision that makes his horn seem to dripwith honey. The quartet Supersilent helped winddown the festival with a powerful set that saw itsincreased instrumental palette find its way.Trumpeter and vocalist Arve Henriksen hasmade his sideline drumming far more effective,while sound artists Helge Sten has added texture-ladenguitar to the enterprise. More than adecade on these improvisers keep finding newways to surprise. —Peter MargasakOrbert Davis Sends Musical Birthday Greeting to MandelaOrbert Davis rehearsingMICHAEL JACKSON CARSTEN STOLZENBACH24 DOWNBEAT November 2008

confection, Davis peppered the set with lighterfare, including “Relax Max,” a cha-cha-chá thatsinger Dee Alexander delievered with irresistiblecharisma. The versatile Alexander subsequentlyturned the mood on its heels with an evocativerendition of Miriam Makeba’s “Little Boy.”Actress T’keyah Crystal Keymah interspersedwith poignant excerpts from Mandela’s memoirs,including key phrases repeated for dramaticeffect. During his time in captivity on RobbenIsland, Mandela was permitted one letter everysix months and spent time in solitary confinement.“Prisoner 466/64” evoked the dull clamorof hammers on rock, recalling the forced laborMandela endured and the deadening torpor ofthese years of containment, with low tones fromthe sousaphone, bass clarinet, tuba and timpani.—Michael JacksonAmerican, North AfricanMusical Bonds Forgedat Festival GnaouaJaleel Shaw(left) withGnawamusiciansSUZAN JENKINSThe Festival Gnaoua in Essaouira, Morocco, is aspectacle of hypnotic music, brilliant colorpalettes and teeming humanity. At its core it celebratesthe music of the Gnawa brotherhood,spirit music purveyors whose sound is driven bythe pulsating bass ranged, three-stringed, camelskinnedguimbre plucked and drummed by theinvited Maalems (or masters). The Gnawa shareancestral lineage with African Americans andhave encouraged joyous musical partnershipsfrom the time Randy Weston first becameimmersed in Gnawa music in the late 1960s tothe Wayne Shorter Quartet’s eager absorption atthis year’s festival—the 11th annual installment—whichran from June 26–29.With the festival, the tranquil Atlantic coastaltown of Essaouira, a haven of Gnawa life, welcomesnearly a half-million festival revelers tothe free event every year. The festival invitesmusicians and the occasional band from theWest, sub-Saharan Africa and other parts ofMorocco to interact with the Gnawa musicianson its two main stages and after-hours acousticsets, and their spirit-centered, trance-inducingmusic dominates the proceedings. Shorter’sgroup and alto saxophonist Jaleel Shaw proudlyrepresented the ancestral African developmentknown as jazz, bringing deep wells of that sensibilityto the tranquil cadence of life in Essaouirathat explodes during Gnawa festival weekend.Shorter’s quartet delivered cunninglyimplied, circular and freely plumbed themes andgrooves, all imagined through the prism of atelepathic band relationship. Bassist JohnPatitucci at one point instigated a wicked tango,drawing a huge smile of encouragement fromdrummer Brian Blade, slashing then tastefullydownshifting the traps alongside. Pianist DaniloPérez grew ever more assertive as the set wendedits way onward. Then the Gnawa musiciansentered to the eager anticipation of the group,particularly the rhythm section, which had plottedits fusion course earlier over savory taginesand couscous at lunch. Before long Shorterfound his place, blowing short phrases amidstthe insistent rhythms that engulfed and clearlybemused him.The next evening Shaw, who had beenenthralled by their vibe, stepped up for somebrotherly dialogue with Malian ngoni playerBassekou Kouyate’s band. Just when it felt as ifthe venue, Place Moulay Hassan, couldn’t beuplifted any higher, Maleem Mahmoud Ghania,one of the pillars of Gnawa music, upped theante. As the huge throng hung onto his mightyguimbre and baritone chants, Guinea paced hiseight percussionists, chanters and acrobaticdancers through a staggering set that left manywrung out from ecstasy. Then he invitedKouyate and Shaw back out for a brilliant finalcall to the spirits of their ancestors.—Willard JenkinsNovember 2008 DOWNBEAT 25

PlayersMarcus Gilmore ;Bloodline FuelWhile it may not be uncommon to find youngdrummers who can execute the range of rhythmicdialects and hybrids that were mainstreamedinto jazz during the ’90s and early ’00s, it’s rarerto hear a young musician who can articulatethose beats with Marcus Gilmore’s finesse. Anencounter with Chick Corea offers one example.In the summer of 2006, Gilmore toured with thepianist, playing timpani and orchestral percussionfrom notated scores, while also propelling aCorea-led quartet. At that time, Gilmore was justa couple years out of high school.“Chick said he hired me because he knew Ididn’t always have to play loud,” Gilmore said.“We were playing with a chamber orchestra,with violins and cellos, in old churches andcathedrals that weren’t made for brass cymbalsor drums. He said, ‘I know you can be delicateand sensitive.’”Since then, Glimore, still shy of 22, hasbecome an in-demand sideman for a wide rangeof leaders, all of whom he feels energize hiswork.“One thing I love about being a sideman isthat I can play in so many different situations,”Gilmore said. “I feel stagnant after I’ve donethe same thing for a long time, so I have toswitch it up.”Gilmore said this in mid-August as he concludedan engagement in Sardinia, Italy, withSteve Coleman, to whom his uncle, GrahamHaynes, introduced him in 2002, when he was15 years old. Two weeks before, he’d concludeda four-night run at Manhattan’s Jazz Standardwith Vijay Iyer, who began to use Gilmore regularlyin 2003. On the following night, he lefttown with trumpeter Nicholas Payton, anemployer since 2004. Later in August, uponreturning to New York, he played choros andswing tunes with clarinetist Anat Cohen, thenflew to the Windy City for a Chicago JazzFestival set with Iyer.The drummer has already become accustomedto fulfilling jam-packed itineraries. Hisrecent resumé includes such consequentialrecordings as Gonzalo Rubalcaba’s Avatar (BlueNote), Christian Scott’s Anthem (Concord) andIsraeli guitarist Gilad Hekselman’s WordsUnspoken (LateSet), as well as projects withCassandra Wilson, Aaron Parks, AmbroseAkinmusire and Walter Smith. Back in highschool, Gilmore recorded and toured with ClarkTerry’s big band, and in 2004 he drum-battledwith his grandfather, Roy Haynes, on GeneKrupa’s “Sing Sing Sing” on a nationally broadcastJazz at Lincoln Center concert.To some degree, Gilmore’s esthetic andmusical proclivities stem from his famousbloodline.“My grandfather strongly influenced my conceptionof drumming,” Gilmore said. “If not forhim, I wouldn’t be playing. He wasn’t particularlyhands-on, but I was eyes-on, always, from theget-go. By third grade, I knew I wanted to be adrummer, and I asked him for a drum set. On my10th birthday, he came by with one of his kits.“Basically, he tried to head me into my owndirection,” Gilmore continued. “He talked abouthow important and fundamental it is for alldrummers to have their own sound on the ridecymbal, and I listened to his ride cymbal beat,crisp and clean, like he speaks—you hear everyword, every syllable. I can ask him what this orthat was like, and he can tell me. It’s a beautifulthing to have access to that much information.”Gilmore bedrocked his rapid learning curveon assimilating the fundamentals at JuilliardSchool of Music, where his mother enrolled himat 11 in courses that covered orchestral and folkloricpercussion, as well as music theory. Heenjoyed and played r&b and hip-hop, but devotedmost of his energy to “finding jazz and classicalrecords.”“I met Elvin [Jones] around that time, whenmy grandfather played a double bill with him atBryant Park, and I studied him and Philly Joeand my grandfather’s contemporaries, as well asIgnacio Berroa, who I heard with Gonzalo,”Gilmore said. “Jazz has a spontaneous elementthat wasn’t there in other things I was hearing.They could be exciting or smooth, but usuallydidn’t change, didn’t explore. In jazz I’d alwaysbe intrigued—something would start here, gothere, go so many places.”In Coleman’s company, Gilmore began tofind an outlet for his own experimental inclinations.“Steve was working on an on-the-spotarrangement of ‘Countdown’ when I met him,and it opened up my mind,” Gilmore said.“Later, he sang me a drum chant that he wantedme to play. It took me a while to get it, but finallyI did. No one had ever sung me rhythms thatwere so intricate and required that level of independence.”The logical next step, Gilmore said, is to documenthis personal development with an albumof his own. “I have enough material to make arecord, but I need to make more time,” he said.“I’m always coming back from somewhere andabout to go somewhere.” —Ted PankenMARK SHELDON26 DOWNBEAT November 2008

PlayersElvin Bishop ; Elder’s SummitElvin Bishop has played blues guitar since the1960s and his self-produced new album, TheBlues Rolls On (Delta Groove), shows howmuch he wants to pass on to a new generation.“I got to thinking about how nice guys wereto me when I was starting out and how lucky Iwas to play with guys like Hound Dog Taylor,Big Joe Williams, Paul Butterfield, Junior Wellsand Clifton Chenier,” Bishop said from hishome north of San Francisco. “Then I got tothinking about the guys coming up now andhow it’d be nice to go back and do the tunesfrom some of those old guys and get these newguys to help me out and illustrate the way bluesflows from one generation to another.”Guided by Bishop, the flow is natural. B.B.King joins him in updating the Roy Miltonjump-blues “Keep A Dollar In Your Pocket”and blues harp elder James Cotton, with up-andcomingsinger John Németh and veteran harmonizerAngela Strehli, deliver the Chicago bluesflag-waver “I Found Out.” Middle-aged folks onother songs include zydeco master R.C. Carrier,boogie revivalist George Thorogood, harmonicachamp Kim Wilson and guitarists WarrenHaynes, Tommy Castro and Mike Schermer. Inaddition to Németh, representatives of the youthmovement are guitarists Derek Trucks andRonnie Baker Brooks and bayou accordionplayer Andre Thierry and the Delta’s preteenand-teenageHomemade Jamz Blues Band.Bishop does not want anyone to get theimpression The Blues Rolls On is just anotherblues album with “a bunch of names up there tosell the thing.” He reasoned, “I tried to come upwith material that would be right down theartists’ alley, match things up good.”Bishop’s own slide guitar is pronounced onJimmy Reed’s “Honest I Do.”“I play the melody and get a lot of satisfactionout of it, because in a way it’s the voice Inever had,” Bishop said. “It’s got a big rangeand you can put the vibrato you want on it.”“Where a lot of guys play slide in open tuningand fire off a bunch of licks simply becausethose notes are underneath their fingers, Elvinpicks only the choice notes and plays themmeaningfully,” Schermer added.For Bishop, the idea of combining differentgenerations is rooted in the early ’60s, when heaccepted a scholarship to the University ofChicago. His school’s South Side location providedthe ultimate in luck for a blues enthusiast.“It was ground zero for the Chicago blues,”Bishop said. “I got to make friends with theguys. When you actually see a guy’s hand on theguitar doing this stuff, you can get somewhere.”—Frank-John HadleyJEN TAYLOR28 DOWNBEAT November 2008

PlayersJoanna Pascale ;Forbidden PracticeThe music of Tin Pan Alley and Broadwayserved as a backdrop for Joanna Pascale’s youthand inform her recent album, Through My Eyes(Stiletto). But the Philadephia singer’s embraceof this upbeat material did not come so easily.Pascale’s mother was religious, and forbadeher from listening to pop music. A year or sobefore high school, Pascale began listening tothe radio when she could get away with it. Shebecame enamored with a Philadelphia stationthat spun big band records, and this exposure toFrank Sinatra, Nancy Wilson and SarahVaughan provided a gateway to jazz.Suprisingly, Pascale’s mother eventuallycaught on. Rather than anger, the music evokednostalgia. The concord was mutually beneficialas Pascale did not find much personal appeal inthe mainstream pop singers who emerged in themid-’90s, anyway.“It took her back because my grandfatherwas an amateur singer who died way before Iwas born. When she saw there was this connection,she just let it happen and allowed me to listento it,” Pascale, 29, said at her home in SouthPhiladelphia. “It’s funny because I wasn’tallowed to listen to my generation’s popularmusic, but I could listen to Billie Holiday sing‘My Man.’“Looking back,” Pascale continued, “I’mgrateful because I immersed myself in the GreatAmerican Songbook. The songs are a part ofme. It’s not like I’m going back and learning thismusic because it’s novel. I’m digging into thismusic because it’s who I am.”While there are rare exceptions—StevieWonder’s “Happier Than The Morning Sun,”Carole King’s “Will You Still Love MeTomorrow?”—Pascale’s muse compels her todelve into the past and unearth obscure repertoire.She largely avoids war horses and the signaturesongs of other artists. “I’m trying to findthese gems that have fallen through the cracks,”she said. “‘What Is This Thing Called Love?’ isnot a song that I particularly care for.”Pascale earned a bachelor’s degree in jazzperformance in 2001 at Temple University,where she now teaches. When Lights Are Low,Pascale’s first album, came out in 2004.Through My Eyes not only features the songsshe typically performs, but also the band thatbacks her three times a week at SoleFood, aseafood restaurant at Philadelphia’s LoewsHotel. Pascale’s hallmarks include an understatedvibrato and a knack for beginning phrases atunexpected moments. Her interpretations bear acloser resemblance to instrumentalists thansingers—she almost never plays it straight. Thegroup includes saxophonist Tim Warfield,drummer Dan Monaghan and bassist MadisonRast, who Pascale married in 2005.While Pascale yearns for more exposure,she expresses satisfaction with her career. Sheconsiders herself fortunate to have come ofage in Philadelphia. “There were so manygreat venues that were around where the oldermusicians would not only play, but just hangout,” she said. “You could sit in with thesepeople, but you couldn’t just get up and fake it.They would invite you up, and you had to sinkor swim.”—Eric FineSTEVE STOLTZFUSHIROSHI TAKAOKAAdam Rudolph ; Framing the WorldPercussionist Adam Rudolph was an early advocatefor fusing jazz and world music, carrying ona tradition of avant-garde multiculturalismforged by Don Cherry. But that attraction todiverse musical traditions was not formedthrough Rudolph’s association with the trumpeteror through his international travels, but byhis seemingly more downhome upbringing onChicago’s South Side.“I heard a lot of great artists who lived in myneighborhood,” Rudolph said. “From Howlin’Wolf I learned how musical technique shouldserve the expression of deep feeling. From theArt Ensemble of Chicago I learned how importantit is to have the courage to pursue the ideasof your own creative imagination. I also learnedthat if I wanted to have a long relationship withmusic, I had to learn as much as I could aboutevery phenomenon of music that there is.”Recently, Rudolph has been applying thoseconcepts to several different projects. HuVibrational is a percussion group with HamidDrake, Brahim Fribgane and Carlos Niño; theGo: Organic Orchestra is an open-ended large30 DOWNBEAT November 2008

ensemble that Rudolph conducts through cuedimprovisational concepts; and Moving Picturesis a malleable ensemble that has been a vehiclefor Rudolph’s compositional ideas since 1992.The blend of musicians and opportunitiesoffered as fodder for these projects in New Yorkbrought him back East a year ago, after twodecades of being primarily based in Venice,Calif.On Moving Pictures’ recent Dream Garden(Justin Time), Rudolph uses his octet to combinedisparate instruments in an additive techniquesimilar to a painter blending colors on a paletteand then allowing them to clash on canvas. Hewrites for the group using his “cyclic verticalism,”which combines African polyrythms andIndian rhythmic cycles.“Each composition zeros in like a laser into aparticular esthetic and formalistic element,”Rudolph said. “When all the musicians understandthat the compositions aren’t just ‘play ahead and then go,’ they can go deep into whattheir role and function is. They can be as free asthey want to be, but the music has direction andfocus.”Rudolph does not take a literal-mindedapproach, as he emphasizes concepts andphilosophies rather than more concrete elementsin blending traditions.“What people call ‘world music’ oftenbecomes a smorgasbord of styles and instruments,”Rudolph said. “What interested memore as time went on was the cultural cosmologythat underlies the music.”At the same time, Rudolph brings his yearsstudying jazz trap drummers to his cross-culturalpercussive approach.“The drummers who influenced me mostwere people like Elvin Jones, Tony Williamsand Ed Blackwell, because they had their ownvoices on the instruments,” Rudolph said.“That’s what I’m trying to do for myself as ahand drummer.”Listening to Rudolph discuss the broader philosophybehind his music—which he sees asone element of the Hatha yoga he’s studied formore than 30 years—the boundary between hiscreative efforts and his spiritual beliefs isblurred. “John Coltrane made overt what everybodyknew was in this music already,” he said.“That you could project a sense of your ownevolution in your personal mysticism.”Rudolph’s compositional specifics encompassa greater philosophical perspective—the spontaneousexisting within an arranged framework.“That’s what this so-called jazz music isabout,” Rudolph said. “In life we don’t knowwhat’s going to happen next. Each day dawnsbut once, and every moment we get the illusionof routine, but we don’t know what’s going tohappen next. The mind loves to go forward andworry, or rehash the past, but all that reallyexists is the moment of the eternal now, andthat’s one of the things this music celebrates.”—Shaun BradyNovember 2008 DOWNBEAT 31

VillageAmbassadorAnat Cohen offers a fresh, multiculturalclarinet sound to the jazz worldBy Dan Ouellette Photos by Michael WeintrobWithin the span of a little less than amonth this summer, Anat Cohen performedin front of two diverse audiences,captivating both.On July 13 at the North Sea Jazz Festival inRotterdam, Holland, the clarinetist/saxophonist andher quartet delivered an exuberant set in front of alarge jazz-minded crowd. Most of the people therewere curious to catch the reeds player who has capturedthe Rising Star Clarinet prize two years in arow in the DownBeat Critics Poll. Cohen not onlyproved to be a woodwind revelation of dark tonesand delicious lyricism, but also a dynamic bandleaderwho danced and shouted out encouragementto her group—whooping it up when pianist JasonLindner followed her clarinet trills on a Latin-flavorednumber by chopping up the clave and flyinginto a dissonant space. With her dark, curly, shoulder-lengthhair swaying to the beat of the music asshe danced, she was a picture of joy.On a hot late afternoon on Aug. 7, Cohen andher band took their song to the streets, this time onan outdoor stage in New York’s Union Square infront of people bustling by on their way home fromwork, lazily hanging out while snacking on barbecuefrom street vendors or sleepily lounging on thesmall grass lawns. It was a totally different audience—notnecessarily jazz aficionados, but musicbuffs who gravitated to the stage because ofCohen’s groove and bubbly, woody tone on theclarinet. The group offered no balladry as theybreezed through an amalgam of styles, sometimesBrazilian with a Middle Eastern vibe, Afro-Cubanwith an Israeli folk sensibility, classical with an IvoPapasov-like wedding party gaiety or straight-upjazz where Cohen snake-danced on clarinet withguitarist Gilad Hekselman.Different crowds, similar response. The audiencesstayed put instead of wandering off—atNorth Sea to any one of the 15 other stages presentingmusic; at Union Square to any number of shopslining 14th Street at rush hour.“It doesn’t matter where we are, whether it’sNorth Sea or here,” Cohen said after the UnionSquare show ended with rousing applause. “We’rehaving fun, which is what the audience is pickingup on, and yes, we’re busy.” She added, “Almostdoing too much,” before skipping off to do a duetwith guitarist Howard Alden at the chamber musicvenue Bargemusic at the Fulton Ferry Landing inBrooklyn. A few days later she jaunted off to theNewport Jazz Festival, where she was enlisted byfestival impresario/pianist George Wein to be amember of his Newport All-Stars group that alsofeatured Alden, bassist Esperanza Spalding anddrummer Jimmy Cobb.Has Cohen’s rise to prominence been meteoric?Not if you’ve been following Cohen’s longstandingbut on-the-fringes Stateside career, first in Bostonand then in New York with a variety of bands, fromBrazilian choro groups to her own Waverly Sevenband that pays tribute to Bobby Darin.34 DOWNBEAT November 2008

Messianic? Certainly in the secular sense, marked by idealismand an aggressive crusading spirit, which permeatesCohen’s musical outlook.Exerting gravitational jazz pull? Indeed. While her musicopens ears and turns heads, at the same time she’s unintentionallybecome the centerpiece for a new jazz scene in NewYork due largely to her indie label, Anzic. Originally foundedto self-release her debut CD, 2005’s Place And Time,Anzic expanded to give Cohen’s colleagues a home base todocument their own music. In addition to her own albums,Anzic has released discs by Anat’s brother Avishai Cohen(including After The Big Rain), Waverly Seven and ChoroEnsemble.On the eve of releasing her latest CD, Notes From TheVillage, Cohen downplayed her role in becoming the focusof a burgeoning musical community. “There was a scenehere before I arrived in 1999,” she said. “I was attracted to itbecause of the enthusiasm, its openness to world music andits dedication to playing jazz, whether it’s traditional, out orwhatever. I was proud to be a part of this. If I wasn’tinvolved, everything would still be happening. There is theimpression that Anzic started the scene, but that’s not true.”Cohen acknowledges that she has served as a catalyst forthe scene’s growth, particularly through Anzic. “I don’t seemyself as the center,” she said. “All the musicians who are part of the labelare striving to do the same things I am. We practice, we write, we record.I’m happy to gather people together to make a bigger force. We’re all doingCDs, so it’s like, let’s unite and make a bigger noise, a bigger statement.”She hastened to add that Anzic is not a closed society. “We’re lookingfor other people to connect with the music, to record different people fromother scenes. That’s how we will grow.”Cohen’s partner in forging Anzic’s artistic vision, arranger and labelgeneral manager Oded Lev-Ari, said, “With record sales overall falling,individual artists need to have some kind of fair mechanism by which theycan get their music out. Anzic artists are more involved in all aspects oftheir CDs—from manufacturing to marketing—which makes them awareof all the costs involved in their recording adventures. We enter into anagreement where both parties share the risks. Nothing is hidden; there areno surprises.” He added that one of the most obvious differences betweenAnzic and other labels is that artists are paid immediately for CD sales versuswaiting for the recording advance to be recovered.That system works for Lindner, who recorded Live At The Jazz Galleryfor Anzic and has a new album in the wings. “I’ve been on major labels acouple of times and it hasn’t been a good experience,” he said. “Youalways have to answer to higher authorities, so it’s hard to be artistic ifthey’re not fully behind you. Anzic has complete artistic freedom. Thatcomes from Anat.”Saxophonist Joel Frahm, a member of Waverly Seven as well as abandleader who released We Used To Dance on Anzic in 2007, likes thelabel model. “It’s less like a typical jazz label in that it’s not a cold businessventure,” he said. “We’re trying to develop as a family. And Anat isgreat at bringing people into the Anzic orbit. She’s so eclectic. She playsso many styles convincingly that she becomes an ambassador for music.”Cohen performs atthe 2008 NewportJazz FestivalBorn in Tel Aviv, Cohen started playing clarinet at home when shewas 12, attracted to its low tones. Her first clarinet was her father’s.She graduated to her own instrument when she went to the TelAviv Conservatory along with her two brothers—her older brother Yuvalhad already picked up the alto saxophone and her younger brother Avishaichose the trumpet, because, Anat said with a laugh, “it only had three buttons,so he thought it would be easy to play.” (The three siblings performtogether in the band the 3 Cohens that released Braid in 2007.)At the conservatory, Cohen played in a dixieland band and at her juniorhigh for the arts studied classical music, in a chamber setting with celloand piano. While most aspiring reeds players set aside their “beginner”instrument for a saxophone, she clung to the clarinet because of its expressivequality. She also began to practice on the tenor saxophone.At the Thelma Yellin High School for the Arts, Cohen majored in jazz,learning early on that the clarinet had lost its popularity in modern music.“People felt it was a folkloric instrument and that it was associated withklezmer,” she said. “Increasingly, my teacher told me to bring my big saxto school, but leave my clarinet at home.” When she reported for her twoyearmandatory Israeli military duty in 1993, she toted her tenor that sheplayed in the Israeli Air Force band.During her years of tenor fascination, Cohen found inspiration in JohnColtrane, Sonny Rollins and Dexter Gordon. She was accepted to BerkleeCollege of Music in 1996 for her saxophone playing. She brought alongher clarinet, figuring that it could be valuable as “a doubling instrument forplaying in big bands.” However, one of her teachers, Phil Wilson, heardher play the clarinet and encouraged her to pursue exploring its depth.“Phil told me that I had a voice on the clarinet,” she said. “I told him Icouldn’t play it that well, that my fingers wouldn’t move like they do onthe saxophone. But he was the first person in my adult life who got methinking about getting my chops on the clarinet.”Cohen committed herself to dual-instrument activities, blowing thetenor in contemporary jazz settings as well as in an Afro-Cuban bandwhile carrying the clarinet to choro sessions and Colombian andVenezuelan folk gigs where the instrument was favored.While for her 2007 album Noir Cohen brought to the mix soprano, altoand tenor saxophones as well as clarinet, her Poetica CD, released simultaneously,was an all-clarinet affair. “My goal was to reveal the poetic sideof the clarinet,” she said. “It’s a voice, not a style. I didn’t want to do aBenny Goodman tribute.”While both discs were enthusiastically received, Cohen’s prowess onthe clarinet upped her status. To bring new life to an instrument relegatedto second-class citizenry in jazz gave Cohen a rep for fostering originalitywith her special touch and vision.“As I began to get recognition as a clarinet player, it triggered in me therealization that I am a clarinetist who can bring something new to theinstrument,” Cohen said. “I didn’t believe that fully until I got my firstclarinet award. After that, I started playing it a lot more in my live shows.The clarinet itself has a nice classical sound, but I try to play it with a gutsysound like the tenor saxophone. That’s become part of the lexicon of mysound. But it can be a challenge. An overblown clarinet can start behavingbadly by squeaking.”Lindner attributes Cohen’s rise to Anzic giving her the opportunity to36 DOWNBEAT November 2008