Judge Michael McC _ nick - Voice For The Defense Online

Judge Michael McC _ nick - Voice For The Defense Online

Judge Michael McC _ nick - Voice For The Defense Online

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Judge</strong> <strong>Michael</strong> <strong>McC</strong> _<strong>nick</strong>*WELDON HOLCOIIB11 1-B N. SpringTyler, Texas 7

JOURNAL OF THE TEXAS CRIMINALDEFENSE LAWYERS ASSOCIATIONVOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong> (ISSN 0364-2232) ipublished monthly by the Texas Crimini<strong>Defense</strong> Lawyers Assaeiation, 603 W. 13thAustin, Texas 78701, (512) 478-2514. Annursubscription rate for memben of the assaeialion is $100, which is included in dues. Secoaclass postage paid at Austin, Texas. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to VOICEfotheDeferrre, MX) W. 13lh, Austin, Texas 78701All anicles and mher editorial contributionshouldbeaddressed totheeditor, Kerry P. Pi@Gerald, Reverchan P lm at Turtle Creek, Suit1350,3500MapleAve., Dallas, Texas 75219Advertising inquiries andcontrack sent to Me,Connally, Arlfoms, Ine., 6201 OuadalupeAustin, Texas 78752 (512) 451-3588.EDITORSEdilor. VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong>Kerry P. fiitz~erald*DallasBusiness EditorF. R. "Buck" Files, Jr.TylerEditor, Significant Decisions ReportCatherine Greene BurneftHoustonOrnICERShidentEdward A. MallenHoustonPresident-ElectJ. A. "Jim" BoboOdessafist Vlce-PresidentTim Evans<strong>For</strong>t WorthSecand Vice-PresidentRichard A. AndersonDallasSecretary-TreasurerGerald H. GoldsteinSun AntonioAssistant Secretary-TressurerBuddy M. DickenShermanSTAFFExecutive DirectorJohn C. BostonAdministrative AssistantLillian SummarellSecretaryShannon MclntoshBookkeeper/SecretaryLinda Shumate6, IY8V'I'EXAS CWMINAL UEWNSKIAWYEllS ASSOCIATIONJANUARY 1989 CONTGNTS VOL. 18, NO. 5FEATURE ARTICLES5 Talking With. . .by Bill White12 <strong>The</strong> Benson-Boozer Debate:How Should We Measure Sufficiency of Evidence?by Chris Hiibner19 Warrantless Searches and Seizures, Part IDby Jade Meeker24 <strong>The</strong> Probation Revocation Hearingby <strong>Judge</strong> Richard Mays30 Polygraph Usage for Attorneys in Criminal Casesby Bill Parker32 In Memoriam- W.T. Phillips33 A Comparison of the Public Defender and Ad Hoc Systemsof Providing Indigent Representationby <strong>Judge</strong> Pat McDowellCOLUMNS3 President's Columnby Edward Mallet4 Editor's Columnby Kerry FitzGeraldSDRl-8 Significant Decisions Repoa34 White Collar <strong>Defense</strong>by <strong>Michael</strong> E TigarNEWS3 Announcements4 Announcements7 Index to Adveaisers11 CIassifiedAds35 List of Granted Petitions forDiscretionary Reviewby John Jasuta36 TCDLA Committee Updateby Jeffety Hirrkley38 Legislative Updateby E.G. (Gerry) Morris39 In and Around Texasby John Boston27 Lawyers Assistance Committee37 <strong>The</strong> Enticementby Patti AndersonPAST PRESIDENTSCharlw D. Bum, Ssn Anlonio. (1987-88) George F. Luquelte, Houston (1978-79)Knor lanes, MeAllen (198687) Emmett Colvin, Dallas (1977-78)Luuis Dugas, Jr. Orange (1985-86) Weldon Holmmb, Tyler (197677)Clifton L. "Scrappy" Holm, Lungview (1984-85) C. David Evans. San Antonio (1975-76)Thomas G. Sharp. Ir.. Brownsville (1983-84) George E. Gilkerron, Lubbock (1974-75)Clifford W. Brown, Lubbock (1982-83) Phil Burlwon. Dallas (1973-74)Charlw M. McDonald. Waco (1981-82) C. Anthony Fdoux, Jr. Hourton (1972-73)Roben D. Jom, Austin (198IL81) Frank hlaloney. Austin (1971-72)Vincent Walker Perini. Dallas (1979-80)DIRECTORSDavid 8. BiresHoustonk i d L. BotsfardAustinWilliam A. Bratton 111DallasStan BrowAbilencCharlw L. CapcnonDBUmJoseph A. Connors IIIMCAIIS~Dick M. DeGuerinHwstonBob &Ira&Wichita FallsF. R. "BueL" Files, Ir.TVIEI -,~~~ AurtinCarolyn Clause GarciaHoustonRonald GuyerSan AntonioMark C. HallLubbockHarry R. HeardLungviewleffmy ~ in~leyMidlandFmnl; JacksonDallasJeff Keamey<strong>For</strong>r wonhJohn LincbargerFan wonhLvnn Wade MaloneWarnEdgar A. MasonMlsrJohn H. Miller. Irlack J. RawitscherHou~tooCharlss RittenbenyAmarilloKent Alan ScbaflerHoustonGeorge SchamnSan AntonioDavid A. ShemadAustinMark StevensSan AntonioJack V. SfricklandFon wmhI. Douglas TinkerCorpus Chn'stiStanlev I. WeinbereD&-Sheldon WeirfeldBrawnrvillsWilliam A. WhiteAustinDain P. WhitwonhAurlinBil WisehkaempcrLubbodiRoben 1. YlaguirreMcAllcnJack B. ZimmcrmannHo~stonASSOCIATEDIRECTORSDon A&msI~ine~ike &ownLubbockWilliam T. HabemSugar LandBob HintonDallasJulie HowellAurlinChuck LanehanLubbockMargy MeyersHwrtonDavid MitchamHoustonRod PontonEl PasoDennis PowellOmgeGeorge RolandMcKinncyMartin UnderwoodC0msloek

President's ColumnLas Vegas! Please plan to attend yourPast President's Seminar and Mid-yearBoard Meeting at the world-class GoldenNugget, a totally new downtown resort.We'll be thereFebmary25-27,1989. Atour of the sights along the Strip will showyou great entertainment and some of thetackiest people in America (members ofthe TCDLA and visiting judges notwithstanding).Wecan play golf andtennisin thevalley and we'll be only 45 minutesfrom the slci slope$ and Hoover Dam.In addition to recreation and CLE, wecan catch up on what's happening in ourstate and national governments.<strong>For</strong> example, a two-year study releasedin December by the Criminal Justice Sectionof the American Bar Association hasreported the "side effects" of the war ondrugs. <strong>The</strong>report concluded that enormousgovernment expenditures have totallyfailed to reduce importation, sale or use ofdope. Indeed, the drug war has created anunderground network of enormouseconomic impact that feeds upon and issustainedby the present systemofprohibitions.Instead of curtailing drug abuse, themassive allocation of law enforcementresources todrug cases hascaused pridlockin the administration of our nation's judicialbusiness, civil and criminal.<strong>The</strong> study reported that:the Justice Depattment and DEA hierarchies.We defenselawyers all know of the £requencywith which agents viblate the oath.<strong>For</strong> example, filing a Franks v. Dela~varemotion is the rule -not the exceptioninsearch wmant cases. Now, it's been admitted:<strong>The</strong> perjury we expect fromofficers is symptomatic of a disease in thesupreme federal drug agency, whosecredibility with the publichas been, in part,sustainedforyears by its abiity to successfullydupe the press.'J%e ABAstudy was basedontestimonytaken from all pups in the legal community,added to a survey of police,prosecutors, defense lawyers and judges.<strong>The</strong> ABA conclusion is that Constitutionalrestrictions, such as the exclusionaryrule and the Miranda protections, are nothindering the police and prosecutors frommaking their cases. Most of the personscontacted in the survey reported that a lackofresources, and amisallocationofresourcesarethemajor obstacles to effective lawenforcement, rather than Constitutionalprotections.What this means is that the TexasCriminal <strong>Defense</strong> Lawyers Associationhas been and remains on the right track inits criticism of the rhetoric of the vigilantepups organized shortly before each bien-Ed Mallettnial legislative session. At the Ias Vegasseminar and meeting, we will vote torecommend or oppose specific Bills thatwill bepending intheTexas legislahuethisspring. We will take positions based onfact, not fiction.<strong>The</strong>re will be one purely social item onthe calendar: Scrappy Holmes willcelebrate his 50th birthday. It's time toParty.<strong>The</strong>se extraordinary efforts havedistortedandoverwhelmed the criminaljustice system, crowding docketsand jails, and diluting law enforcementand judicial efforts to deal withother major criminal cases.Shortly after this announcement,another flap began, a controversy whoserelationship to the ABA Report is subtlebut real: <strong>The</strong> DEA confessed to having aninstitutional policy of lying to the nationalnews media. This means that what the JusticeDepartmenttold American people, foryears, about the size and number ofseizures and the names and numbers ofdefendants, were often lies told to"protect" covert operations and to enhancecongressional funding and job security forAnnouncementsHome Run Hitter's SeminarPlan now! TCDLA's spring trip will be to CANCUN, Mexico. We will depattWednesday, April 5,1989, and return Sunday, April 9,1989.<strong>The</strong> package price is $545/double occupancy, with a $150 single supplementcharge. This price includes: 4 nights deluxe accommodations at theHOTEL INTER-CONTINENTAL CANCUN; hotel tax and tips; surcharges; maid service; baggagehandling; round trip airfare from DFW or Houston Intercontinental; round trip transfers;and our meeting room.<strong>The</strong> hotel has its own water purification system, beautiful pool, best beach in Cancun,deep sea fishing, and sightseeing trips to the many beautiful spots of the island.1f ycni would likejunior innd dcluxe suites, thcy arc available at an extra charge.- FOR --- FURTHER - - INFORMATION. PLEASE CONTACI' Martha land~m ofAssociated Travel, 1-800-3465764.FULL PAYMENT IS NEEDED BY FEBRUARY 6,1988.January 1989 1 VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong> 3

Editor's ColumnWehopethateachofyouenjoyedavery second edition of "Texas Rules ofmerry Christmas and that you have a suc- Evidence Manual," written by Hulen D.cessful 1989. We have been delighted at Wendorf (Professor of Law Emeritus,Ithenumber ofyou who havesent us articles Baylor University) andDavid A. SchlueterI forpublication in the <strong>Voice</strong>. Weencourage (Associate Dean and Professor of Law, St.-all of wu to eet involved and send articles.and thus share your expertise. Please notemy change of address for the materials:Kerry P. FitzGerald, 3503 Maple Avenue,LB 27, Suite 1350, Dallas, Texas 75219.As 1988 drew to a close, Richard"Racehorse" Haynes received yet anotheraward, this time fromthe California Attorneysfor Criminal Justice. <strong>The</strong>y selected"Racehorse" to receive the 1988 SignificantContribution to the Criminal Jus-tice Systemaward.'All ofus are awaiting furtherword fromtheunited States Supreme Court, this timeMarv's Universitv). , <strong>The</strong>se authors did anexcellent job in bringing together a mountainof materials in this Manual. <strong>The</strong> rules,both civil and criminal, are examined indepth and are compared. <strong>The</strong> relevantcases are discussed under each rule.Whether youarein thefieldtrying lawsuitsor appealing adverse judgments, orwhether you are thejudgecalling theshots,there is always a need for materials whichcontain the rules, cases construing therules, and an independent analysis whichbrings the rules into focus. This Manualwas written by two professors with out-for thedecision in ~nited~fates v. Mistret- standing bac&un&. I believe the endfa, which w+ argued in October of 1988. result is an evidence Manual, with Supple-This case will decide whether or not the ments, which will benefit every one of us.federal sentencing -- rmidelines are constitu- <strong>The</strong> Manual is available from the Michietional.Company [(P.O. Box 7587, Charlottes-While we wait for that decision, many ville, VA 2290&7587) (804) 972-7600].of us continue to file a Notice of Appeal Chuck Lanehart, a prominent Lubbockfollowing sentencing, ifthereis any chance attorney, sent me a jury note received byat all that the defendant would have been the Court just before a mistrial wasable to secure a lighter sentence had the declared. His client had a .I1 B.T. in aguidelines not been Eollowed.D.W.I. case. Chuck wrote that he hadIn the meantime, the United States "framed the owma1 in (his) office as aKerry P. FitzGeraldtv."After receiving Chuck's jury note, Irecalled a similar note, which made meequally ill in a case tried in the late '70s.<strong>The</strong> note read: "We are hopelessly deadlockedinour efforts toreach averdict. It isthedesireandrequestoftheentirejurythatthe evidence be reopened because theevidence presented is insufticient and in-General Accounting officeis conducting a reminder that the defense counsel should canclusiv~, making a true verdict imposcomprehensiveanalysis of the federal sen- be forever vigilant in reminding juries of sible." A subsequent special pleaof doubletencine rmidelines and their resoective ao- the law in regard to the burden of oroof in ieonardv likewise fell on deaf ears. So-- - ,. ,plication throughout the country. Two acriminalcase." <strong>The</strong>noteread: "Jury isun- muchfor war stories, at leastthose withoutofficials fiom the office in Cincinnati, able to make a decision due to lack of a happy end'mg. I hope each of you enjoysOhio came to Dallas in early November of evidence. Four -guilty; - . Two -not gug- . a very rewarding - 1989.last year and interviewed members of theFederal Judiciary and the United StatesAttorney's Office in Dallas. <strong>The</strong>y alsovisited at len& with our own resident expert,F.R. "~UCK' Files. It was quite obviousthat these officials were not onlyconcerned with making a report to Congress,but were also committed to submittinga very thorough analysis whichincluded input from experts within thecriminal defense bar, such as Buck Files.I am not really the person to write bookreviews, and I generally fmd it difficult toenlist much help in writing a book review.Instead of delegating another such effort, Ithought ~wouldpe~onall~ recommend the I4 VOICE for the Defeme I January 1989AnnouncementsLong Range Planning.Cammittee MeetingWill be held at the GOLDEN NUGGET HOTEL, Las Vegas, Nevada, Friday,February 17,1989 from 3:00 p.m. to 300 p.m.This meeting is an open meeting and all members are welcome to attend and helpTCDLA make plans for the fuhlre. Please bring your ideas, advice and informationthat will help TCDLA better represent you, the criminal defense lawyer, or thecriminal justicesystem.If you have ideas, advice, information or requests and cannot attend, please sendto Ron Goranson, 714 Jackson Street, Suite 900, Dallas, Texas 75202 or call Ronat 214-651-1121.

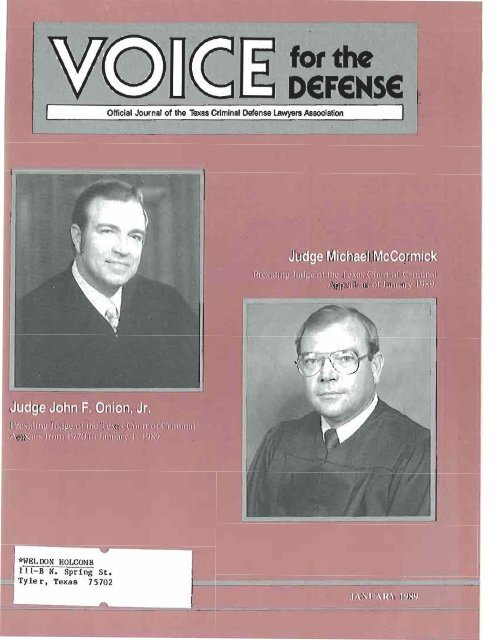

Talking With.. .by Bill WhiteOn January 1,1989, <strong>Judge</strong> John Onion, Court of Criminal Appeals <strong>Judge</strong> since of those conversations appear below.twenty-two years as a Texas Court of 1981, was elected the new Presiding <strong>Judge</strong>Criminal Appeals <strong>Judge</strong>, eighteen years of of the Court. Bill White, an Austin lawyer, Bill White (BW): What has been yourwhich he served as a Presiding <strong>Judge</strong>, had an opportunity to talk to the two men personalphilosophy as an appellate couHretired. <strong>Judge</strong> <strong>Michael</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormick, a about the court and their careers. Excerpts judge?<strong>Judge</strong> John F. Onion, Jr. nus electedto the Court of Crintinal Appeals in 1967and, at 41 years of age, became theyoungest elected judge at that time toever serve on the Court of Criminal Apoeals.In 1970, <strong>Judge</strong> Onion wselectedzs Presiding <strong>Judge</strong> of the Court ofCriminal Appeals in the first statewidedection far the position of Presrding<strong>Judge</strong>. He nus re-elected in 1976 and2982 without opposition. <strong>Judge</strong> Onion'urs drafted arrdparticipared in securing'egislalion and proposed constitutionalzmendnzents affecting the operation of'he Coun He organized the first staffforzny appellate coun in Texas which has5econte the model for many other appel-'ate courts. <strong>Judge</strong> Onion has personallybvritten over 4SW legal opinions and7articipated in thousands of otherfecisions.Prior to his tenure on the Coun ofCrirninal Appeals, <strong>Judge</strong> Onion servedIS the District Court <strong>Judge</strong> for the 175thDistrict Coun in Bexar County, Texasfrom 1957 until 1967 when he waselected to the Court of Criminal Appeals.He hasalso servedasa~tassistantdistrictattorney for Bexar County andas a Justiceof the Peace for Precinct NumberOne in Bexar County. <strong>Judge</strong> Onionreceived his ID. from the University oJTexas School of Law in 1950.<strong>Judge</strong> Onion has received numerousho~wrs during his legal career. In Marchof 1973. he nus chosen as the orrtstandinggraduate of the Universiry of TexasSchoolofLawforcontributio,r to thefieldof law and society. In May of 1972, hewas awrded Order of the Coif by theUniversity of Texas School of Law foroutstanding judicial service. <strong>Judge</strong>Onion is listed in Who's Who inAnzerican Law and was chosen by theState bar in 1984 and 1988 as Outstand-ing <strong>Judge</strong> in Texas for demonstrating excellenceas an appellate judge andsubstantive contributions to the legalprofessions. <strong>Judge</strong> Onion has conductedsenrbursthrough the National College oJthe State Judiciary in various states andis a long-time faculty member of theTexas College for the Judiciary. He hasalsopublishednun~erousanicles in nunydifferent publications, including theTexas Bar Journal, the southwesternLaw Journal, the Texas Law ReviewandSouth Texas Law Journal. <strong>Judge</strong> Onionalso authored the "Special Co~nntentaries"found in the 1965 Vernon's Amnotated Code of Criminal Procedure,Volumes I through 5.<strong>Judge</strong> Onion sewed in the UtzitedStates Marine Corps during World War11. He is married and has three children.<strong>Judge</strong> Onion: I think every judge whocomes on the court probably comes as aproduct of his experience and backgroundinlarge measure and probably has a prettygood idea of his philosophy before he getshere. Some people are labeled state'smindedjudges by virtue of their opinionsor sometimes because of their background.Maybe they've been former district attorneysbefore they came to the court. Somejudges come here having shared both theexperience of being a prosecutor and adefense counsel. Others come here strictlyas defense counsel, and many people havea tendency to try to put them in slotsor givethem labels, and they say they're defensemindedor they're state's-minded. Mybackground and experience for so manyyears has been as a judge; I thii myphilosophy is to call them as you see them.Let the chips fall where they may, and onetime you're going to be ruling for the state,another time for the defense, but when thepublic sees that you arecalling themas yousee them, and you're not trying to reach acertain result in every case, I think theyhave more respect for that judge and hisopinion because they know he's trying tobe fair and impartial. <strong>The</strong>y might not alwaysagree with what be does. <strong>The</strong>y maylie to applaud the guy that's on their sideof the docket more or gives the indicationthat he is, but every judge I think is aproduct of some background, and in fact, Ithink when you examine most of thejudges' records, you may find that theyhave maybe written more one way for thedefense than for the state and visce versa.But, you'll fmd that they've gone bothways. I think most, by the time they gethere, are trying to be fair and impartial.BW: Myfirst cnnfact with the criminallaw was in 1976, as a briefing attorney forthis court. I recall that when I wanted togain an understanding of a particularJanuary 1989 I VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong> 5

area of the criminallaw, I usually wenttoone ofyouropinwns becanse they seemedto contain an historiealperspective ofthelaw. Is that something you have alwaystriedto do as ajudge? Give lawyem an hktoricalperspective of the mqior areas ofcriminal law?<strong>Judge</strong> Onion: Yes, because I like thatas an approach to use in trying to understandsomething. It's always helped meand I guess I've always felt like if I'mgoing to have to do the research, I wantsomebody else to have the benefit of itwithout having to plow through the sameground. If they can find an opinion of minetbat would take them through, and I try tobe as thorough as I can. I think that meansI've tried to keep in mind that in writingopinions, you write for a whole bunch ofdifferent groups. You write for the partiesand for the trialbench. And then, of course,you have to keep in mind that youropinions may be of some help to the lawstudent. I've always kept something elseinmind that I haven't always been successllin selling to other judges. That is yon try towrite an opinion that's understandable tothe press because if the press doesn't understandit, they'll give you lots of badaverage, publicity, when you're just asright as you can be. But if you haven'tmade it clear so that the unhained lawyeror the non-lawyer news media has difficultyunderstanding it, thcn you may cnd upwith a lot ofouestions about vouroninion.<strong>The</strong>n I guess, being a trial judge, I alwaysthought that it always helped to put a littlefwtnoteor something inthat tells themthisis theway it might save youquestions lateron at the trial of some other case.BW: So you feel like these opinionsshouldhe@givegiridanceto both lawyersand trial jndges on how to conduct theirbusiness?<strong>Judge</strong> Onion: Oh, yes, absolutely. Ithink that's the main purpose of writingone of these opinions. <strong>The</strong> main purpose,of course, is to dispose of the case and doso rightly, but I think in the process, if youcan aid the bench and the bar in the trial offuture cases, keep in mind that some lawstudent may be readmg your case, may behelping him to learn the law, and also keepin mind the court canbe saved alot of uglypublicity if the non-lawyer news reportercan understand what you're talking about.BW: I never thoughf of writing fortheunderstanding of the press.<strong>Judge</strong> Onion: Oh, yes, and sometimesI've said that to judges, "<strong>The</strong> way you'vegot it phrased here, it's going to wave aredflag-you'reright, butthe way yon'vegotit phrased is going to make a hunch ofpeople mad about it. Write it, explain it alittle bit better." And a lot of times judgeshaven't always agreed with me on that approach, but I think thosearethings that I'vetried to keep in mind.BW: I think the bench and bar wouldbe interested in knowing what actnalprocess yon go through in researchingand wriring an opinion.<strong>Judge</strong> Onion: It depends fmt of allwhether or not we've had oral argument. IfI'veheenexposed to acase through oral argument,and having read the benchmemorandum before I heard oral argument,I know something about it beforehand.If not, if I'm getting the case fresh, Istart just lie1 do with all cases in readingthe briefs and getting a feel for what the issuesare; I don't take one ground of error,I read through the entire brief because lotsof times, you find working only on oneground of error, you find that you're overhkingsomething that relates to anothcrone. So1 trvtorcadthc bricfsoibothsidcs.get a pre& good idea of what the issuesare, all the issues, and then I read therecord. And I think this is important. Manytimes people ask me as an appellate judge,"Do you read the record?" Not only do Iread therecord, hut Iread it maybe two andthree times. And sometimes the answer tothese points of error are very simply statedin the record. Very clearly in the record.<strong>The</strong>y may not have been pointed out in thebrief, or they've been overlooked in thebriefs. I think answers to some of yourtougher questions are found simply byreading the record. <strong>The</strong>n I start my individualresearch trying to group the pointsof error that are related, but to answer eachand every one of them and to thoroughlyresearch the case. We find many times thebriefs are just kind of an assistance to getus started. A lot of times, we really have todo theresearch afterthecasegets here. Andthen after that's thoroughly done, then ofcourse, we try to put it into a draft opinionthat we will feel fully answers the points oferror and also will meet with the majority'sapproval. It doesn't serve any purpose towrite something way off out of themainstream and way off wme, hopingthat maybe the court will go along withyou. You realize that you've got a courtand the majority may say take it back andrewrite it, we won't go along with this.BW: So you take into considerationthe otherjudges' points of view from thebeginning.<strong>Judge</strong>onion: Yes-that doesn'tmeanthatI'mgoing to change my outlookon thething, but I wouldn't go out and put somethingway out that I think is not goingthrough conference.BW: If you conld choose an idealbackground for an appellate judge, whatsod of background would it be?<strong>Judge</strong> Onion: I think he should first bea criminal trial judge with a few years experiencebefore he comes up here. I don'tsay that youcan't beagood appellatejudge 'or even a great appellate judge withoutthat, but1 thinkthat experienceis soimportant,I really do. I've told one legislativecommittee that I wouldn't write that in asa requirement, but as I get older in dealingwith more judges who are very sincereabout what they're looking at in the recordbut had no trial judge experience, I'm almostinclined to think tbat it maybe oughtto be a prerequisite to being on the appellatebench.BW: Al~mst all the appellate judgeshere have litigant experience as either apmsecntor ordefense lawyer, don't they?<strong>Judge</strong>onion: Yes,they do. But it's sortof like the judge who was appoint6 to thetrial benchshortly after I went onto districtcourt. He was appointed to another districtcourt and he was a lawyer with many yearsof experience, and he came in to see me andsaid, "What do you say to a guy when youtake the guilty plea? I've been there 100times but Inever listened to whatlhe judgesaid, so please tell me." You can have a lotof experience in the Rial court as a lawyer,defense lawyer or prosecutor, but sometimesyou don't realize why the judge is6 VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong> I January 1989

saying what he says.BW: If gives you a much befferfeel?<strong>Judge</strong> Onion: I thii it gives you amuchbetterfeelwhenyou'relookingat therecord.BW: You were a trial jdge for manyyears; didyou like being a trialjudge betterthan you've liked being an appellatejudge?<strong>Judge</strong>onion: IS& both. I thinkit wasreal hard when1 first wneup to the appellatecourt not to be a little sow that I hadleft the trial bench. You were a judge onyour own down there, you called themlikeyou saw them, if you thought somethingwas right, you did it that way. Up here youhadto have amajority voteand sometimeswhat you thought was right was voteddown, and it's p~tty hard to take at times.But then after awhile, you get accustomedto it. I think <strong>Judge</strong> Tnunan Roberts took alot longer to adjust than I did. He had beena trial jndge a long time, too; and so, yes, Ithink the trial judge position is an enjoyableone. You get to see the lawyers andwitnesses and jurors, and youdeal with thelawyers and the people around the courthouse.All of that is gone when you get toan appellate court.BW: Which one do you think is theharderjob?<strong>Judge</strong> Onion: This one. Well, it's liethe former appellate jndge who said thatsomeday he was going to go back to thetrial court because down there he couldshoot and nm, up hem he had to stay stjuand write the reasons. I think that's true, Ithink you can call it as you see it if youthink it's right, you can say overruled orsustained, you can issue what orders youthink and go on about your businass. Youdon't have to research to give what youthink is the right answer, sometimes on avery meager record. And I think lots oftimes, triallawyers don't realize that whpthey'resending questians upthat theyreallywant answered, they don't call all theirwitnessesthat they need and whenthey dohave the important witnesses there, qeyleave a lot of questions hanging. A lot oftimes I don't think they review their cases,either. That'smy opinion. <strong>The</strong>y oftendon'treview their cases and see what they needto ask, so if they ask just what comes tomind at the time and thenexpect us to takea meager record and lay down a hard andfast rule for all the courts to follow. Itmakes it very difficult. So, yes, this workuphereis muchharder. IknowI'veworkeda lot harder. I thought I was a very busy,energetic, hadworking trial judge, and itwasn't anything compared to what I'vedoneup heretokeep up overthe years. I'veworked nights and on the weekends. Istarted taking cases home becauseat first Ithought I was too slow in getting myopinions out and because all of the judgesat that time had been here for some timeand they seemed to be turning out theiropinions faster than I, so I started takingwork home. Twenty-two years later, I'mstill doing it, but I'm a hell of a lot fasterthan I used to be.BW: Overthe course of ZZyears, whatopinions ofyoum do you believe are yourbest work or are most sigmifcanf in theklw?<strong>Judge</strong> Onion: Oh, gee, I've wfittenover4,50Oopinionsinthe22 yearspndit'shard to pick out particular ones. I wouldthink that one case would be Olson 1484S.W.2d 756 -holding that compelling ablood test and handwriting exemplar donot constitute compelling an accused to"give evidence against himself' in violationof the Texas constitutional self-incriminationprivilege]. Perhaps Martinez[437 S.W.2d 8421,abouttheseparatehearingrequired, on challenged eyewitnessidentificatidn testimony would be anotherone. Yes, those are a couple that havelasted. In the past,I1ve written an opinionandit's lasted fot 10 or 12 years, and thena new majority comes along and overrulesthe case, hut those are the cases that havelasted and westill quoted by many COW.BW: Just as amatterof interest, doyourecall the most bizam case that you'veencountered?<strong>Judge</strong> Onion: One that always sticksout inmy mind is one1 mn't write. <strong>Judge</strong>Dailey wrote on a case 6ut of Harris Countywhere the jndge charged the jury on theextraneous offense and ignoredthe chargein the indictment. I thinkthat was the mostunusualthatIcan think of off the top of myhead. <strong>The</strong>judgechargedthejurytofind thedefendant guilty if they believedbeyond amisonabledoubt that he committed anextnurw,usoffense.BW:l hwe always wondered whetherpersuasive writing of the brief or persuasiveoml argument has any eflect onthe outcome of cases that come to theCourt.<strong>Judge</strong>Onion: I think if it's a well-donebrief and it's wen-organized aud movesswiRly and concisely to the point that heseeks to advanceand is persuasive, you dotake a longer, harder look at it than if it'snot very well put together. Now oral argumentpeople are not going to likeme to saythis, but there have been few cases everchangedby oralargument. Many attorneyscome down here and argue, but they a@sayingusually what's already intheirbrief.In other words, very few cases are everchanged onthe basis of oral argument. <strong>The</strong>real value of oral argument as I view it isthat when you request oral argument,there's a bench memorandumdone by ouradministrativeassistant~,thejudgesreaditthey hear oral argument, and when someotherjudge draws that case and then c d-lates an opinion, they say, "Wait a minute,that's a little bit different than the case Iheardargued" or"Didn'theraisethis pointthat you haven't covered?" So, I think ithelps to prevent what aU appellate courtsseek to avoid, is a one-judgedisposition ofthe case. So oral argument I think is helpful.But as far as changing opinions, I'mnut sure it really does all that much gwd.BW: Would it be your advice todefense lawyers to no#filltheir brief withpoinfsthatdon'the agreaf dealof meritand limit their attention to their mostmeriforiouspoints?<strong>Judge</strong> Oninm Absolutely. I would alsosay something else. I never understand attorneyswho put their best pint of errornumber 16 in 32 paints of error, becauseyou plow through, and you find one afteranother that seems meritless, and prettysoon you say, "Well, this fellowhas alarge<strong>Voice</strong> AdvertisersClassified Ads . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9FreelanceEnterprises . . . . . . . . 15January 1989 I VOICEfor the <strong>Defense</strong> 7

number ofpoints of error, andnoneofthemare good." And then you stumble ontonumber 16 and you wonder why he buriedhis best point down there. Further, I havedifficulty understanding why an attorneywould makeone point of error number oneand another one that is so closely relatednumber28. And if you'regoingta writeonone of them, you're going to have to writeon the other one, and yet he'll brief it andput all the facts up there about number oneand then he has to rebrief it and say almostthe same thing in dealing with number 28.I don't know why they aren't pulled togethermore, but you find it in briefs thatway. <strong>The</strong>y split themup, they're not closetogether at all.BW: Is there anything in particularthat you want to say to the judges and attorneysof Texas?<strong>Judge</strong> Onion: <strong>The</strong> only thing I canthinkof that I'd really like to say is that if1had to do it all over aeain. I'd still choosethe judiciary. I still think ;hat's an importantpas of thelegal profession. I thinkthatwe should take every effort to encouragemore people to consider the judiciary andgood people, we need good people, wellqualifiedpeople on the bench and I thinkto keep, to get good people and keep themthere, we're going to have to do somethingaboutjudicial salaries. I'msure that Icouldhave nladenlot morenamy practicing lawthiln sittinz - on the bench over all of thescyears. It's hard to say to my son who's alawyer or to other young people who ask,"Do you think there's a chance for me toever be a judge?" and I say, "Oh, yesthere's a chance, but I think you reallyought to seriously consider whether that'swhat you want to do so much that you'rewilling to give up something that you pmbabiycould acquire a lot easier." But, wedo need good, honest people who are goingto call them like they see them. I thinkthat's what the members of the bench andthe bar ought to be looking for. Do somethingtoencouragemoregoodpple to getinto the judiciary.BW: What, ifyou feellikesharingwifhus, are your plans affer you leave theCourt of Criminal Appeals?<strong>Judge</strong> Onion: Oh, I was afraid youwere going to ask me that. I really don'tknow. I'mprobably going to end up sittingby assignment around the various pints ofthe state as a trial judge. Of course, if theyask me to come sit on the appellate courtsometimes I wouldn't be opposed to that.InfactJ'd probably look forward to it. But,I assume that what I'll he doing mostly isaccepting assignments to the trial bench.BW: See you in Couft!Conversation With<strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormickBill White (BW): What do you see asachange in yorcrrole now thdyou're thenervprwidingjr~dge of the Court?<strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>urmick: As far as theopinion writing and all, I don't see that myrole will change; I'll still just be one of 9voting judges and so I don't expect tochange the direction that the court is<strong>Judge</strong> <strong>Michael</strong> J. <strong>McC</strong>on<strong>nick</strong> wasplected to the Court of Criminal Appeals11 1981. In November of 1988, he won:lection to the position of Presidingludge on the Court of Criminal Appealsmd will begin his tenure in January of'989. <strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormick received hisSD. from the St. Mary's Universityichool of Law in 1970. He graduatedkom St. Mary's as an Honor Graduaterrzd was editor of the St. Mary's Lawmoving philosophically. I don't see thatthat's therolethat peopleperceive, at leastinternally, to be the role of the Presiding<strong>Judge</strong>. I say administratively, carry out thewishes of the court as far as administrativematters, but as far as the practitioner willperceive -I don't perceive that there willbe any change at all other than the changeof whoever thenew member that the governorappoints would impact the alignmentsof the coua.BW: Dayonperceive a change in howthe courf's going to opemte?<strong>Judge</strong><strong>McC</strong>ormiek: Yes, I've got a lotof ideas and I think there are a lot of othergood ideas that other judges have, and Ithink that we can say without hesitationthat if there's some ideas that surface thatmight helpus move cases a little better andbe a little more responsive to the needs Ithink in the system that the majority rulesis one way I'm approaching it. And if thereJorrrnal in 1969 and 1970. hr 1970, hewas named as the Leslie Merrin~ OutstandingLaw Graduate. He received hisundergraduate degree froin the Universityof Texas at Austin.<strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>orr<strong>nick</strong> served on theBoard of Directors for the National DistrictAtiorneys Association from 1977rrntil1978. He ws Executive Director ofthe Texas District and County Altorneysas so cia ti or^ from 1976 throrrgh 1980,and served as President of the NationalAssociation of Prosecutor Coordinatorsin 1978. He worked as an Assistant DistrictAttorney in Travis County, Texas&a 1971 until Novernber of 1972 as aChief Felony Prosecutorand Chief of theAppellate Division. <strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormick~asalsoa bnepngattorneyforthe Courtof Criminal Appealsfrom May of I970through July of 1971.<strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>orr<strong>nick</strong> is a member ofnumerous State Bar conmdttees and Iectrrresat many criminal law seminars. HeMas a member of the drafting committeeof the 1973 Penal Code and authoredBranch annotated Penal Code, 3rdedition.<strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormickalso received theRosewood Gavel Awardfrom St. Mary'sLaw School in 1984.8 VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong> I January 1989

are five judges that want to try something,I hopethat we'll give it a whirl, unless youtry and you don't know if it's going towork; if it doesn't work we can always goback to whatever the system was before.Yes, so I think there's a number of thingsthat we can probably see tried that are newor novel.BW: Can you think of any way withyour present staff and caseload to speedup getting an opinion out?<strong>Judge</strong><strong>McC</strong>ormick: No, Bill we've gota fantastic staff and they can churn it out. Ithink we'reprobably operating close to themaximum right now. I think that we coulddeemphasize some things. What I wouldlike to do is see that the legislature give1 107 jurisdiction to thecourts of appeals.1think that would then free up - <strong>The</strong>studies that we've done indicate that wespend about 50 man hours, attomey manhours per weekou writs in our central staff,andthat'snotcountingthetimethat they'rereviewed up in our offices. That's essentiallyone very experienced lawyer we useto do take-offs on writs of which 90% arereally frivolous. Each judge has to act onabout 350 writs. Now, if we spread that outto the couits of appeals based on the numberof judges on the cows of appeals, itwould end up that each judge on the couaof appeals would end up doing about 25,about 2 per month.BW: Wouldyon give the corrrt of appealsdeath penalty jurisdiction also?<strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormick: I would like to, Ithinkat least the issues could be reviewed.I think we could separate a lot of the wheatfrom the chaff there and then handle themon petitions for review much lie we donow. I think that we could do morejusticeto the meritorious issues in thecase insteadof having to write on 47 clearly nonmeritoriousissues and only maybe 4 or 5 goodissues.BW: I have noticed in recenf timesseeing a lot of remands going back to thecourt of appeals to deal with issues ofharmless error. How do you feel aboutthat?<strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormick: Well, there's a lotof discussion about that. My feeling is weare a court of last resort and when you lookatthebasisupon which petitions for revieware granted, I perceive our role to be that ofthe ultimate decision-maker on issues, andonce we have made an ultimatedetermination,hopefully that determination is goingto be the law for a little while. It is the dutyof the court of appeals then to make thatapplication. And it's only those misapplications that we should be taking a lookat.1 know thatit'screatingalotofworkforthe courts of appeals, but realistically theyhavealready reviewed therecord one time.And it seems like at least it's arguable thatif it were sent back to the court or to thejudges that have already read that recordonce, they would certainly be able to comeup with a solution much easier than ushaving to redo it from the whole cloth.BW: What is your personal judicialphilosophy?<strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormick: My main approachto the interpretive position that thecow must take is that of a strict constructionisttype of judicial approach. I guessthat comes from the fact that havingworkedwith thelegislatureand seeing howthe legislature functions, I feel that that'sthe legislature's responsibility to write thelaw, and our responsibility to cany out andinterpret that law to cany out the intent ofthe legislature. Whether we agree with theintent or not should not enter into my writingof the opinion. If the expression of thelegislature is clear, if the intent is clear,then I think it's our responsibility as thecourt to carry that out.BW: How do you feel aboirt looking tothe United States Supreme Con~t decisiom~LY being the lasafthe land, insteadoJlonking to oiw State Consliliition lu seewhether il provides greater protectionthan federal law?<strong>Judge</strong><strong>McC</strong>ormick: Well, you're talkingin general terms certainly. We have theright to interpret our State Constitutionwithin the confines of similarprovisions ofthe US. Constitution. I think the issue primarilyevolves around the fundamentalrights of the Bill of Rights as expressed inthe two documents. I have an idea that unlessthere is a clear departure in the languageof the Texas Constitution from thecorresponding provision of the federalconstitution, that thehistorical backgroundis, as a general rule, that which was drawnfrom the federaldocument. History injournalsof the constihltional convention of1845 pretty well bear that out except insomevery limited ways. If you go backandlookatthehistorical basisofthedocument,and clearly see that there was an intent toafford a greater right, I have no qualmsabout that, but I do believe that original intenthas got to be part of my judicial philosophy.Had the people of Texas wanted abroader expression in our constitution,they would have said so.BW: Whatprocess do you go throughin writing an opinion?<strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormick: Well, I don'tknow. Mine's probably different fromeverybody else's. Just the work load keepsme from writing as much as I would liketo. I've always lied and enjoyed the appellatework, I did it when I was in theD.A.'s office as well as trial work. And Istill do a lot of it outside thecourt with mybooks and stuff. I wish I had more time todo it. As to the way it works now and theway we write opinions in my office, is myresearch assistant and my briefing attomeywill go pickup a case. We'll discuss the is-Classified Ads. Be typed.Be worded as it should appear.Include the number of consecutive issuesit is to appear.. Be prepaid. (M&e checks payable to k-forms, Inc.)Be received by the 15th of the monthpreceding date of publication.Classified Advertising MUWClassifid ads areS15.00 for the Bat 25 wordsand 50C for every word over 25. Advertisingcnov should be submitted to ARTFORMS.6'2% Guadalupe, Austin, TX 78752. Tel.(512) 451-3588.Acceptance of classified advertising forpublication in the VOICEfor lhe Defeme doesnot imply approval or endorsemenl of anyproduct, service, or representation by eitherthe VOICE for rlre <strong>Defense</strong> or the TCDLA.No refunds on cancelled ads.We Want to Buy Your Books! TopValue Law Book Exchange, 27516Blanco Road, San Antonio, Texas78258, 1-800-321-1228. We Sell Books,January 1989 I VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong> 9

sues, what my gut reaction is, having reviewed it when it came up previously onPDR. I tell them my gut reaction of what Ithinktheoutwme oughtto beand why andthen I turn them loose and let them write.Mer they've prepared a draft opinion, itcomes back in here and as time allows, Iwork through those drafts, make whateverchanges I want, if they're in pretty goodshape wecanjust make minor changes thatmight he necessary and send it out of hereas an opinion. IfIperceive some problems,I may ask them to rewrite, re-research orreinvestigate those issues, hut right nowof tips you can think o$<strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormick: Put the best pointof error fust, don't hideit down in the bottomsomewhere. So many times, the bestpoint is downlike number eight or nine outoffifteen. Put your best one fmt, that's theone we're looking for if there's a goodpoint. Let us zero in on that one, don't letus work through all of them and, afterwe've written a forty-page opinion, discover,my God, here's a good point. I thinkthat's one thing. Secondly, undo discussionand hypothetical situations within abrief that don't really help us. I wouldpeal. Ithink you oughttowmeuphereandgive us your best shot.BW: After being an appellate coutrjudge for eight years, is there somethingthat you would tell trial couls judges toheb the appeals coutr do its job?<strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormick: WeU, you know,I'venever sat on a trial wurt. I don't thinkI have the temperament that I could sit onatrialcourt. Itriedalot of cases whenlwasin theD.A.'s office, Icamot sit and watcha trial. I cannot go walk into a courtroomand watch someone trying a we, and Ithat's about the only way that we &n pos- muchpreferthey statetheir groundoferror don't think I could sit on a bench and dosiblv even hove to stav

themsinceI'vebeenhereissoflofaliaisonfor ow budgetary matters,I think that or Iwant to hopefully regenerate that relationshipthat I've had with the legislature,hopefully in fuaherance of ow whole 5ystem.BW: Whnt are you goi~zg to ask fromthe legislature on behalfof the cowt?<strong>Judge</strong><strong>McC</strong>ormick: When it comes towhat thecontt wants in the way of legislativeaction,Iwill appear overthereonly onthose matters where the majority wants meto be wer there. I don't have anagenda ofmy own by any stretch of the hagination.Our primary goal, of come is our budget,and hopefully some improvement in theareaof staff, and I hope that I've got somecommitments from not just the prosecutors,but from the defense attorneys locallyfor some help in working with theleg&lature and try& to get thLm attunedto the fact that we do need some help. Wehaven't had any personnel increases since1973, and that I think is going to theprimary goal of the whole cow. Budget isow main concem at this time.BW: Who do you feel hns injluencedyou the most in your carver?<strong>Judge</strong><strong>McC</strong>ormiek: Oh, I thinkthere'sno question,leonDouglashadthemostinflueneeon me, at least in my weer. Hegave me my first job when I got out of lawschool. I've known him a long, long time.His daughter andmy wife weremommatesincollege.He gavemea job whenlgot outof law school. He encomgedme to go tothe D.A.'s office and get some trial experience,so i'd say that was the majorguiding hand' I'd say that secondly, I'dhave to say Dain Whitworth, probably. Iworked with Dain for so many years at theD.A.'s association. ThoughDainprobablywouldn't want to takecredit for it, butDainhelpedrriedevelop anattitudeofreceptive-ness and compmmise that I like to think Ihave.BW:Zsthere anythingyou wanttosayto the bench anddefense bar?<strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormick: Well, a couple ofthings. First of all, I'm really lobking forwardto the next six years, and I hope it'sgoing to be pfwductive for everybody involvedincriminaljusticeand int~courts.Secondly, I want you to understand, mydoor is always opentosuggestioy Ifthen?are practitioners that have someideas thatmight help us better do owjob, I $we wantto hear about it. I'm corning into this jobsoe of like the dog that caught the bus. Igot it, now what am1 going to do with it Iwant to be receptive to ideas that mighthelp us. Let's commnnicate, and if there'sa problem in ow rules or a problem in ouropefations that someone perceives, let usknow about it. We're not up here in anivory tower.I<strong>The</strong> National Legal Aid & Defender Association presents:LIFE IN THE BALANCE: Defending Death Penalty CasesM4T)(3NALLEGAL February 24-25,1989AID & DEFENMRASSOC~A~ Wyndham Hotel Southpark, Austin, TX1625 KSmEEI, N.W.EIGHM FLOORWASH.. D.C. 2W06Co-sponsored by:Texas Criminal <strong>Defense</strong> Lawyers Association(202) 452-0620FacultyMillard FarmerCathy E. BennettScott HoweKevin McNallyDeana LoganGerald H. GoldsteinRobert McGlassonDennis BalskeJ. Vincent Aprile IIBryan StevensonScharlette HoldmanJoseph NurseyStephen BrightAndrea LyonDavid &ruckGeorge KendallAdvance RegBtratlon: NLADA 8 TCDLA members -- $160, Non-members --$ZOO<strong>For</strong> information, contact: Mary Broderick, NLADA, 1625 K St. NW, 8th Floor, Washington, DC 20006.Phone (202) 452-0620.January 1989 I VOICEfor the <strong>Defense</strong> 11

<strong>The</strong> Denson-Boozer Debate: How ShouldWe Measure Sufficiency of Evidence?by Chris HiibnerIn January of 1980, Mike Onega wasindicted for credit card abuse.' <strong>The</strong> indictmentalleged that he "intentionally andknowingly with intent to fraudulentlyobtain property and services" presented aSears credit card with knowledge that thecard had not been issued to him. Ortegawas convicted and on appeal he alleged,inter alia, that the evidence was insnfficientto support the jury's fmdmg that heused the credit card with intent to fraudulentlyobtain both property and services.<strong>The</strong> Corpus Christi Court of Appeals heldthat although theie was no evidence thatOrtega used the credit'card to obtain services,the evidence was nevertheless sufficientto sustain his conviction for creditcard abuse. Ortem v. State. 653 S.W.2d1982). <strong>The</strong> court of appeals concluded:"We fail to see how the use of 'and services'in the indictment injured the defendant."Onega, supra, 653 S.W.2d at 830.<strong>The</strong> Court of Criminal Appeals, onoriginal submission, affirmed after findingthat the evidence showed Ortega intendedfraudulently to obtain not only "property,"but also the "services" necessaryto complete the transaction at the timehe presented the credit card. Ortega v.State, 668 S.W.2d 701, 705 (Tex.Cr.App. 1983). On rehearing the Courtreversed Ortega's conviction and ordereda judgment of acquittal, fmding that theevidence was insufficient to show that thesales clerk's "service" was the intendedobject of Ortega's desire. "<strong>The</strong> steps takento extend him credit were merelv , incidentalto the transaction." Ortega, supra, at706 (Opinion on Rehearing). It was heldthat the extension of credit, in and of itself,without further proof, does not constitutea "service."In reaching this conclusion, <strong>Judge</strong>Campbell added, "because the charge instructedthe jury that it must fmd bothpropertyand services before returning a guiltyverdict, then it was necessary that there besufficient proof of both means alleged."12 VOICE for tke <strong>Defense</strong> I January 1989Chris Hiib,ter is a native of Oak Ridge,Tennessee. He graduated from IndianaUniversity in 1982 (Phi Beta Kappa) witha double major in history and politicalscience and received his J. D. degreefromthe University of Housfon Law Center in1985.Chris has worked as Briefng Attorneyfor Presiding <strong>Judge</strong> John F. Onion of theTexas Court of Criminal Appeals (1985-861, and was also employed as <strong>Judge</strong>Onion's Research Attorney. He is licensedtopractice before the Texas Supreme Couriand the United States District Courtfor theWestern District of Texas. Chris is nowpracticing criminal law in Austin.Ortega, supra, at 707 (emphasis inoriginal). <strong>Judge</strong> Campbell maintained thatotherwise a guilty verdict would be contraryto the law and the evidence. and citedwith approval <strong>Judge</strong> Clinton's explanato~yfootnote in the opinion on original submissiondiscussing "surplusage" in the court'scharge. That fwhote read in relevant partBut once the [surplus] phrase is incor-porated into the court's instructions tothe jury in such a way that the jury mustfind it before a verdict of guilty isauthorized, Article 36.13, V.A.C.C.P.,it must be proved, or the verdict willbe deemed "contrary to the law andevidence." See Article 40.03(9),V.A.C.C.P. In sum, there is no suchthing as "surplusage" in the part of thecourt's instructions to the jury whichauthorizes a conviction, and if the prosecutorbelieves that portion of thecharge unnecessarily increases his burdenofproof, it behooves him speciallyto request a charge which correctlyallocates the burden pIaced on him bylaw. This is nothing more than thecourse of law which is due before a personmaybe deprived of liberty. Article1 .O4, V.A.C.C.P. And if the recordreflects the prosecutor has pursued thiscourse to protect his lawful obligations,but the trial court has neverthelessrefused the amendment to the indictmentor submission of the requestedcharge, and the evidence is found insufficientto support the verdict bemuseof the trial court's error in this regard,those reviewable rulings of the trialcourt found erroneous by the appellatecourt constitute "trial error," and theState is free to pursue another prosecution.Cf. Burks v. United States, 437US. 1, 98 S.Ct. 2141, 57 L.Ed.2d 1(1978); and Greene v. Massey, 437US. 19,98S.Ct.2151,57L.Ed.2d15(1978).Ortega, supra, at 705, n. 10 (emphasis inoriginal).<strong>Judge</strong> Clinton's footnote No. 10 effwtivelyset the stage for a debate which hasdivided the Court of Criminal Appeals fornearly a decade. <strong>The</strong> debate focuses onwhether sufficiency of the evidence is tobe measured by the charge that is givento the jury. This article will analyze indetail two cases in which the Court hasaddressed this issue at length, namely Ben-

son v. State, 661 S.W.2d 708 (Tex.Cr.App. I982), cert. denied, 467 US. 219,104 S.Ct. 2667, 81 L.Ed.2d 372 (1984)and Boozer v. State, 717 S.W.2d 608(Tex.Cr.App. 1984). <strong>The</strong> writer will thenturn to the subsequent case law to assesshow the Court has dealt with this issuesince deciding Benson and Boozer. Hopefully,a clearer picture will emerge fromwhat has proven to be a complex and contentiouslegal issue.On original submission, Benson attackedthe sufficiency of the evidence to sustainhis conviction based on the lack of evidenceshowing his intent to commit thefelony offense of retaliation.2 <strong>The</strong> indictmentalleged that Benson "did then andthere intentionally and knowingly enter ahabitation without the effective consent ofVirgie Harris, the owner, having intent tocommit the felony offense of retaliation."Writing for the majority, Jndge Odom succinctlyoutlined the question presented:Hence the issue before us is whetherone who intends "to coerce . . . aprivate citizen to drop assault chargespending against him" possesses therequired intent to commit the felonyoffense of retaliation. Stated more narrowly,is this "private citizen complainant,"who had not testified in anyofficial proceeding, a "witness" as thatterm is used in the Retaliation statute,V.T.C. A,, Penal Code, Sec. 36.06?Benson, supra. at 710.In disposing of this issue <strong>Judge</strong> Odomnoted that the Legislature had, by statute,differentiated offenses against "witnesses"only and "witnesses and prospective witnesses."<strong>The</strong> Conrt held that the term"witness" under V.T.C.A., Penal Code,§ 36.06(a), means "one who has testifiedin an official proceeding," thereby excludingamerely "prospective witness." It wasthus relatively easy to conclude that sincethe complainant, Mary Benson, was onlya prospective witness against her exhusbandin a pending assault charge, theevidence adduced at trial was insufficientto show that Benson possessed the requisiteintent to act "in retaliation for or on accountof the services of another as awitness." Benson, supra, at 71 1 (emphasisin original). Benson's conviction wasreversed and a judgment of acquittal wasordered.Jndge Odom's straightforward conclusionbecame a distant memory as the Conrtdelved headlong into the State's firstmotion for rehearing. This opinion,authored by <strong>Judge</strong> Clinton, interpreted theState's new approach as follows:On motion for rehearing, however,the State's Attorney contends the evidencewas adequate to support theindictment allegation that appellantintended to commit the offense of "retaliation''-~~long as the general term,"retaliation," is specifically narrowedto the alternative theory in which theintended victim is an "informant" asopposed to "witness." [footnote omitted]<strong>The</strong>refore, goes the argument, theerror in the case is merely a matter ofan erroneous charge which was draftedon a theory not supported by the evidenceand, as such, presented only"trial error'' which does not necessitatethe entry of a judgment of aquittaL3Benson, supra, at 711-712 (emphasis inoriginal).<strong>Judge</strong> Clinton acknowledged the State'sadvancement of "a provocative argument,"but concluded that since the Statedid not object to the portion of the court'scharge now complained of on rehearing,it was precluded from benefitting from anyperceived error in the charge.More important for our purposes, however,is the rationale Jndge Clinton setforth in reaching this conclusion. Hewrote:Because a verdict of "guilty" necessarilymeans the jury found evidence ofthat on which it was authorized to convict,the evidence is measirred by thecharge which perforce comprehendsthe indictment allegations. [footnoteomitted] It follows that if [the indictment]does not conform to the charge,it is insufficient as a matter of law tosupport the only verdict authorized.[footnote omitted] Benson, supra, at712 (Emphasis supplied).<strong>Judge</strong> Clinton concluded that under thecourt's charge the only verdict authorizedin view of the evidence was "not guilty."Having found no "trial error" of whichthe State might benefit upon retrial, theCourt concluded that the disposition madeon original submission was correct. <strong>The</strong>State's first motion for rehearing wasoverruled..<strong>The</strong> State promptly submitted a motionfor leave to file a second motion for rehearingbased on the identical contentions rejectedin the first motion for rehearing.Consequently, the Court again faced "theissue of whether the reviewing court mustlook to the indictment-as the State contends,or to the charge-to determine thesufficiency of the evidence." Benson,supra, at 713. After distinguishing thedistinct functions of the indictment vis-avisthe charge, <strong>Judge</strong> W. C. Davis determinedthat the charge in the instant casecontained no error. <strong>Judge</strong> Davis thenlooked to the indictment to see whether theevidence was sufficient to show that Benson"possessed the requisite intent to act'in retaliation for or on account of the servicesof another as a witness."' Benson,supra, at 714.A comparison of the "indictment, proofand charge," revealed, as it had on theprevious two submissions, that the Statefailed to satisfy its burden of proving thatBenson acted with anything but retaliationas it related to a "witness." In upholdingthe Court's previous result, however,<strong>Judge</strong> Davis added another dimension tothe analysis:We hold that when a charge is correctfor the theory of the case presented wereview the sufficiency of the evidencein a light most favorable to the verdictby comparing the evidence to the indictmentas incorported into the charge.Benson supra, at 715 (emphasis inoriginal).In denying the State's second motion forrehearing <strong>Judge</strong> Davis concluded that "[a]reading of the charge and indichnent as incorporatedinto the charge shows that theevidence is insufficient as a matter of lawto support the jury's verdict and the conviction."Benson, supra, at 716.Now, instead of measuring the evidencesimply by the charge that is given, as JndgeClinton had suggested, the Court expandedits analysis to include a comparison of theevidence to the indictment as incorporatedinto the charge "when a charge is correctJanuary 1989 I VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong> 13

for the theory of the case presented."AU this did not sit well with <strong>Judge</strong><strong>McC</strong>ormick, who dissented to the denialof the State's second motion for rehearing.He argued, citing plenty of case law, thatthe Court's practice "bas been to reviewthe sufficiency of the evidence by examiningthe allegations in the indicrment and theevidence presented at trial." Benson,supra, at 718, n. 1. <strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormickexplained:<strong>The</strong> purpose of an examination as to thesufficiency of'the evidence is not todetermine whether this particular juryerred in their verdict, but whether "arational trier of fact" could have foundthe essential elements of the offensebeyond a reasonable doubt. Jackson v.Virginia, 443 U.S. 307,99 S.Ct. 2781,61 L.Ed. 2d 560 [(1979)]. In otherwords, has the State met the burden ofproviding the allegations made in thcirindictment against ., the dcfendcnt. Benson,supra, at 717-18.Although <strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormick agreed thatthe abstract portion of the charge expandedon the allegations in the indictment by addingthe phrase "as a witness," he did notbelieve this was error. He added:However, for the purposes of discussion,assuming the addition of thisphrase was error, it was not the type oferror envisioned in law to mandate ajudgment of acquittal. Rather, it is whathas become known as "trial error,"that is, error which renders a casereversible and ripe for new trial. <strong>The</strong>United States Supreme Court in Burksv. United States, 437 US. 1, 16, 98S.Ct. 2141,2149,57 L.Ed.2d 1 (1978),recognized this distinction and includedincorrect jury instructions under thecategory of trial error. Benson, supra,at 718.Judgc <strong>McC</strong>ormick concluded that the inclusionof "witness" in the~indictment~~~~~had~no bearing on Benson's guilt or innocenceand that "even if the jury charge shouldbe considered when discussing sufficiencyof the evidence, the evidence in this casewas clearly sufficient to find that appellanthad the intent to retaliate against a witness-witnessbeing properly defined at thetime of trial by a layman's definition."Benson, supra, at 721.After Benson, the battle lines wereclearly drawn. On one side a majority ofthe Court agreed that sufficiency of the evidenceshould be measured by comparingthe evidence to the indictment as incorporatedinto the charge. If the charge iscorrect for the theory of the case presented(i.e., there is no "trial error"), but theevidence is insufficient to support the instructionssubmitted to the jury, then anacquittal results. This is especially truewhere the State fails to object by tenderinga special requested charge under Article36.15, V.A.C.C.P., and as a resultshoulders an added burden of proof.<strong>The</strong> dissenters in Benson argued that anyerror in the charge should be interpretedas "trial error," thus entitling the defendantonly to a reversal and the possibilityof facing a new trial. <strong>The</strong> premise here isthat the indictment, and not the jurycharge, should be looked to in assessingthe sufficiency question. "In other words,has the State met the burden of proving theallegations made m their indichnent againstthe defendant?" Benson, supra, at 718(<strong>McC</strong>ormick, J., dissenting). <strong>The</strong> argumentmaintains that the sufficiency errorwhich the majority found in Benson hadnothing to do with the defendant's guilt orinnocence and that the evidence clearlyproved up the allegations in the indicrment.In Boozer, the trial court's charge instructedthe jury that Margaret Wilson wasan accomplice witness as a matter of law;however, the evidence showed that thecourt's instruction was erroneous. Prior tothe submission of any charge to the jury,Boozer made a motion for an instructedverdict of acquittal based on the State'sfailure to meet its burden of adducing independentevidence corroborative of theaccomplice witness's testimony <strong>The</strong> motionwas overruled and on direct appealBoozer argued that the trial court hadreversibly erred by denying his motion forinstructed verdict. <strong>The</strong> El Paso Court ofAppeals found that while no corroborationof the accomplice witness existed, theevidence did not establish the witness asan accomplice as a matter of law and thereforeBoozer was not entitled to the instruction.Writing for the majority, <strong>Judge</strong>Clinton noted: "Thus, as we understandit, the court of appeals held the evidencewas insufficient to support the jury's verdictthat appellant was guilty under thecourt's instructions, but the insufficiencywas 'harmless' because appellant was notentitled to have the State prove whatthe trial court instructed the jury mustbe proved before a conviction was warranted."Boozer, supra, at 609.<strong>The</strong> Court of Criminal Afpeals rejectedthe lower court's rationale and reaffirmedthat "the sufficiency of the evidence ismeasured by the charge that was given."Boozer, supra, at 610 (emphasis inoriginal). In reaching this conclusion <strong>Judge</strong>Clinton stated specifically that the Courtwas not reviewing "whether the evidenceadduced at trial supported submission ofthe court's instruction that the witness wasan accomplice as a matter of law." Boozer,supra, at 610 (emphasis in original). Instead,Benson was cited for the proposition"that if evidence does not conform tothe instruction given, it is insufficient asa matter of law to support the only verdictof 'guilty' which was authorized." Boozer,supra, at 610-11. <strong>Judge</strong> Clinton dismissedthe State's now familiar argument conceming"trial error" and emphasized that theState, like the defendant, never objectedto the burden of proof placed upon it bythe trial court's instructions. He concluded:Under the trial court's charge inthe instant case, the only verdict authorizedin view of the evidence was "notguilty"; restated, had the jury followedthe trial court's instructions, appellantwould have been acquitted. Boozer,supra, at 611.Accordingly, the judgment of the court ofappeals was reversed and the cause wasremanded to the trial court for entry of ajudgment of acquittal.<strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormick dissented, as he hadin Benson, to the majority's opinion onoriginal submission. He noted: "Onceagain the majority has seen fit to enter anerroneous order of reversal and acquittalwhen the evidence presented at trial clearlysatisfies the allegations of the indictment."Boozer, supra, at 613. <strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormickargued, a la Benson, that the instructionalerror was not of the type envisioned towarrant a judgment of acquittal, hut ratheramounted to "trial error," which renderedthe case merely reversible and ripe for a14 VOICE for the <strong>Defense</strong> I January 1989

ANNOUNCING THE 1989 EDITIONS OF THE TEXAS HANDBOOK SERIESINCLUDING THE NEW ADDITION TO THIS SERIES:THE TEXAS CRIMINAL EVIDENCE HANDBOOKTEXAS PENAL CODE HANDBOOK:About 400 pages of text and casenotes, including the full text of the 1974 Texas Penal Codeand updated with- annotations on Texas court decisions reported through 754 S.W.2d.TEXAS DRUGS AND DWI HANDBOOK:Over 130 pages of text and casenotes, including the text of the Controlled Substances Act,Dangerous Drugs Act, Volatile Chemicals, Simulated Controlled Substances, and DWI Statutes,and updated with annotations on Texas court decisions reported through 754 S.W.2d.TEXAS CRIMINAL PROCEDURE HANDBOOK:Over 700 pages of text and casenotes, including the text of the provisions of the Texas Codeof Criminal Procedure relating to criminal procedure. (Does not include chapters relating toevidence, which are included in the Texas Criminal Evidence Handbook.) Also included areprovisions of the Texas Rules of Appellate Procedure relating to criminal cases, and updatedwith annotations on Texas court decisions reported through 754 S.W.2d.TEXAS CRIMINAL EVIDENCE HANDBOOK:About 400 pages of text and casenotes, including the text of the provisions of the Texas Codeof Criminal Procedure relating to evidence (Chapters 14, 15, 18, 24, 38 and 39), as well asthe Texas Rules of Criminal Evidence. Also included are annotations on Texas court decisionsreported through 754 S.W.2d.QuantityPrice1989 Texas Penal Code Handbook 60.001989 Texas Drugs & DWI Handbook 30.001989 Texas Criminal Procedure Handbook 90.001989 Texas Criminal Evidence Handbook 60.00AmountPostage and handling: $2.00 per book on orders under $100.00Ship to:Subtotal:Sales Tax*:Total Enclosed*:* Sales tax information: inside Austin MTA: 8%elsewhere in Texas: 7%Mail completed form to:~reelance Enterprises, Inc.P. 0. Box 15243Austin, TX 78761-5243

new trial. Since it was the trial court thaterred when it gave the faulty instructionto the jury, "the only proper remedy isto reverse and remand for a new trial."Boozer, supra, at 613. <strong>Judge</strong> <strong>McC</strong>ormick'sdissent was joined by three other judgesof the Court.With such disparate pints of view dividingthe Court, the Statejustifiably filed itsmotion for leave to file a motion forrehearing. <strong>The</strong> Court denied the State'smotion, although several opinions werefiled both in support and in dissent of theCourt's action. <strong>Judge</strong> Clinton wrote to concurin the denial of the motion, reemphasizingthat "when the defendant, the Stateand the trial judge all agree as to what mustbe proved in a prosecution, yet the evidencefails to measure up, the State has hadits 'bite of the apple' since being given afair opportunity to marshall the evidencenecessarily includes a comprehensive electionof exactly what that evidence mustestablish." Boozer, supra, at 614. <strong>Judge</strong>Clinton concluded that there was no "error"other than insufficiency of the evidenceand that the State should not beallowed to complain on appeal that its"critical choice to acquiesce in the burdenimposed on it in the trial court, constituteda critical 'error' entitling it successively toprosecute a citizen." Boozer, supra, at614.<strong>Judge</strong> Campbell also concurred in theCourt's denial of the State's motion forrehearing. He felt, "[alfter carefully reexaminingthe issue in this case," that thecause was correctly decided on originalsubmission. Nevertheless, he complained:However, the majority on original submissionfails to define the crucial phrase"reviewable rulings of the trial court,"Boozer v. State, No. 402-82, Slip op.at 6, quoting Ortega v. State, 668S.W.2d 701, 705, no. 10 (1984), andtherefore fails to give the bench and baradequate guidance in determiningwhether appellate courts will permitretrials in cases where the State requests,but does not receive, a chargewhich correctly sets for the State'sburden of proof under the indictmentand facts of the case. Boozer, supra, at616.<strong>Judge</strong> Campbell cogently argued that inthe instant case the State shouldered agreater burden of proof by acquiescing ina jury charge requiring it to corroboratethe testimony of its key witness, which theState could not do. However, "[wlhen theState does make known its complaint to thetrial judge concerning the burden allocatedto it by the charge, it not only allows thetrial judge to correct the charge then andthere, but also notifies appellate courts thatthe State is not volunteering to shoulderany greater burden of proof than is requiredby the indictment and the evidencepresented in the case." Boozer, supra, at616. If the State follows this course of actionand the trial judge nevertheless insistson making the State shoulder a greaterburden of proof than required by the law,<strong>Judge</strong> Campbell "would hold that allrulings on the State's requested specialcharges pursuant to Art. 36.15, [V.A.C.c.P.] are re~iewable."~ Boozer, supra, at616. Such an error would then be considered"trial error" and the State wouldbe allowed to retry an accused, providedit complies with Article 36.15, supra. Thiswas essentially what <strong>Judge</strong> Clinton hadargued in Ortega, supra, at 705, n. 10.<strong>Judge</strong> Campbell would not, however,agree with the majority opinion's "implication"that the jury charge may not bereviewed unless the accused first raises theissue. He concluded:Thus, I don't think that reviewing theState's requested special charges is evenremotely tantamount to allowing theState to appeal. <strong>The</strong> function of the requestedspecial charge on appeal in thesufficiency context is to allow the appellatecourt to determine whether theevidence is insufficient because theState "bit offmore thanit could chew,"or because the trial judge erroneouslyforced the State to prove somethingwhich was not necessary under the lawnor under the evidence adduced at trial.In either situation, the decision toreverse or affirm is based on the chargeas given to the jury. Only the defendant'schallenge to the sufficiency of theevidence occasions appellate review ofthe State's requested special charges,and then the purpose of review is solelyto determine whether a retrial is permittedunder Burks v. United States,437 US. 1,98 S.Ct. 2141,57 L.Ed.2d1 (1978) and Greene v. Massey, 437U.S. 19,98S.Ct.2151,57L.Ed.2d15(1978). Allowing the State, in fact evenencouraging the State, to prevent adefendant from obtaining appellaterelief to which that defendent is not constitutionallyentitled is simply not thesame as allowing the State to appealfrom an adverse outcome in the trialcourt. Boozer, supra, at 617 (emphasisin original).Hardly a lone dissenter, Presiding <strong>Judge</strong>Onion filed his dissent to the denial of theState's motion for rehearing, in whichthrcc othcr membcrs of thc Gurt joined.<strong>The</strong> Presiding <strong>Judge</strong> initially nnted that thctrial court had not erred in overrulingBoozer's motion for instructed verdict,since Margaret Wilson was not an accomplicewitness under Article 38.14, supra,and therefore her uncorroborated testimonyalone could support the conviction."This should have ended the matter."Boozer, supra, at 618. According to <strong>Judge</strong>Onion the court of appeals "sua spontebroadened the contention and did not mentionat all the motion for instructed verdictset forth in appellant's only ground oferror." Boozer, supra, at 618.<strong>The</strong> court [of appeals] stated, "Appellant'ssole ground of error is that theevidence was insufficient to sustain theconviction because the same was basedupon the uncorroborated testimony ofan accomplice witness." Article 38.14,V.A.C.C.P.***<strong>The</strong> Court of Appeals agreed the evidencewas insufficient to corroborateWilson's testimony if she was an accomplicewitness, but held that in lightof Easter [536 S.W.3d 223 (Tex.Cr.App. 1976)], that Wilson could not beprosecuted as a party to the burglary,and was not an accomplice witness. <strong>The</strong>claim of insufficient evidence was rejected.Boozer, supra, at 618.Boozer then "switched" from his originalcontention on appeal to alleging that thecourt of appeals erred in denying him thebenefit of the finding by the trial court thatthe witness was an accomplice as a matterof law. It was on this basis that Boozer'spetition for discretionary review was16 VOlCEfor the <strong>Defense</strong> I Januq 1989