An evaluation of in-possession medication procedures within ...

An evaluation of in-possession medication procedures within ...

An evaluation of in-possession medication procedures within ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>An</strong> <strong>evaluation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> <strong>procedures</strong> with<strong>in</strong>prisons <strong>in</strong> England and WalesA report to the National Institute <strong>of</strong>Health ResearchAugust 2009

Copyright © 2009 The Offender Health Research NetworkTitle: <strong>An</strong> <strong>evaluation</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> <strong>procedures</strong> with<strong>in</strong> prisons <strong>in</strong> Englandand WalesFirst published: August 2009Published to OHRN website, <strong>in</strong> electronic PDF format onlyhttp://www.ohrn.nhs.ukUnless otherwise stated, the copyright <strong>of</strong> all the materials <strong>in</strong> this report is held by TheOffender Health Research Network. You may reproduce this document for personal andeducational uses only. Applications for permission to use the materials <strong>in</strong> this documentfor any other purpose should be made to the copyright holder. Commercial copy<strong>in</strong>g,hir<strong>in</strong>g and lend<strong>in</strong>g is strictly prohibited.The Offender Health Research Network is funded by Offender Health at theDepartment <strong>of</strong> Health, and is a collaboration between several universities, based at theUniversity <strong>of</strong> Manchester. It was established <strong>in</strong> 2002 to develop a multi-discipl<strong>in</strong>ary,multi-agency network focused on <strong>of</strong>fender health care <strong>in</strong>novation, <strong>evaluation</strong> andknowledge dissem<strong>in</strong>ation.2

Research teamUniversity <strong>of</strong> ManchesterPr<strong>of</strong>essor Jenny Shaw, Head <strong>of</strong> Psychiatry Research GroupDr Jane Senior, Research Network ManagerLamiece Hassan, Research AssistantDavid K<strong>in</strong>g, Research AssistantNaomi Mwasambili, Research AssistantCharlotte Lennox, Research AssociateDr. Matthew Sanderson, Speciality Registrar <strong>in</strong> Forensic PsychiatryJade Weston, Research AssistantAddress for correspondence:Dr Jane SeniorOffender Health Research NetworkHostel 1, Ashworth Hospital,Maghull, Merseyside, L31 1HWE-mail: jane.senior@merseycare.nhs.uk3

AcknowledgementsWe are grateful to all prison establishments throughout England and Wales whichtook part <strong>in</strong> the national survey which formed the basis <strong>of</strong> this report.We are particularly grateful to those staff and prisoners who gave up their time forface-to-face or telephone <strong>in</strong>terviews provid<strong>in</strong>g their thoughts and op<strong>in</strong>ions.F<strong>in</strong>ally, we would like to thank Joanna Mell<strong>in</strong>g and Sarah Royale for assist<strong>in</strong>g withthe transcription <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terviews.4

ContentsResearch team ................................................................. 3Acknowledgements .......................................................... 4Contents........................................................................... 5Executive summary .......................................................... 71. Introduction ............................................................... 121.1 Background............................................................................. 121.2 In-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong> community and hospital sett<strong>in</strong>gs ........ 131.3 Wider medic<strong>in</strong>es management and cl<strong>in</strong>ical governance issuesencompass<strong>in</strong>g prison sett<strong>in</strong>gs .................................................... 141.4 Rationale for <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong> the prison sett<strong>in</strong>g........... 161.5 Prison based <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> policies ............................ 181.6 Risk assessments & reviews <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong> .................................. 191.7 Packag<strong>in</strong>g and storage issues .................................................... 221.8 Evidence <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong> practice .......................... 231.9 The next step .......................................................................... 241.10 Research aims......................................................................... 242. Method ...................................................................... 252.1 Phase 1: National survey .......................................................... 25Survey design ...........................................................................25Sample.....................................................................................26Procedure .................................................................................26<strong>An</strong>alysis....................................................................................262.2 Phase 2: Qualitative <strong>in</strong>terviews .................................................. 26Interview schedule design ...........................................................27Sample.....................................................................................27Procedure .................................................................................28<strong>An</strong>alysis....................................................................................283. Results ...................................................................... 303.1 Phase 1: Questionnaire survey..................................................... 30Sample..................................................................................... 30Verification <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong> ............................................................ 31Then and now: 2003 versus 2008 ................................................45Summary <strong>of</strong> questionnaire survey f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs ....................................473.2 Phase 2: Semi-structured <strong>in</strong>terviews ............................................ 48Verification <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong> ........................................................... 49Actions where immediate verification not possible.......................... 49Barriers to verification <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong> ............................................ 50Improvements to verification <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong>................................... 525

In-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> ........................................................... 53Benefits <strong>of</strong> IP ............................................................................ 604. Discussion ................................................................. 705. Recommendations ...................................................... 786. References ................................................................. 797. Appendices................................................................. 82Appendix 1: Questionnaire ................................................................ 83Appendix 2: Interview topic guides..................................................... 87Appendix 3: Participant <strong>in</strong>formation sheets.......................................... 89Appendix 4: Thematic network summaris<strong>in</strong>g key <strong>in</strong>terview themes ......... 926

Executive summaryIntroductionOffenders <strong>of</strong>ten come from deprived backgrounds with histories <strong>of</strong> social exclusionand disadvantage, frequently compounded by complex and multiple healthproblems. S<strong>in</strong>ce the cl<strong>in</strong>ical development partnership between the NHS and HMPrison Service was <strong>in</strong>stigated <strong>in</strong> 1999, a wide rang<strong>in</strong>g work programme has beenundertaken to improve prison based health services to improve people’s health andlife chances. Much <strong>of</strong> this has been driven by the ‘equivalence pr<strong>in</strong>ciple’, the notionthat prisoners should have access to ‘the same quality and range <strong>of</strong> health careservices as the general public receives from the NHS’ (Health Advisory Committeefor the Prison Service, 1997).Every year, approximately £7,000,000 is spent on medic<strong>in</strong>es for prisoners (DH,2003). Historically, healthcare staff have been responsible for supervis<strong>in</strong>g andadm<strong>in</strong>ister<strong>in</strong>g s<strong>in</strong>gle doses <strong>of</strong> all but the most benign <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong>s. However, thedrive for equivalence <strong>of</strong> care has led towards allow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> tobecome the default position, rather than the exception. In-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong>means that where possible, prisoners are given autonomy and responsibility for thestorage and adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> their <strong>medication</strong>, dependent on <strong>in</strong>dividual riskassessment (Bradley, 2007).Notably, several benefits <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> have been previouslyreported <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g medic<strong>in</strong>es be<strong>in</strong>g adm<strong>in</strong>istered at more appropriate times,reductions <strong>in</strong> time spent by prisoners queu<strong>in</strong>g at <strong>medication</strong> hatches andreductions <strong>in</strong> workload for healthcare staff and escort<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong>ficers (DH, 2003).Despite such evidence, there apparently rema<strong>in</strong>s unease among some staffwork<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong> prisons based on notions that <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> may<strong>in</strong>crease the risk <strong>of</strong> drugs be<strong>in</strong>g abused, traded, stolen or used to self-harm viaoverdose (Bradley, 2007).This study was commissioned by Offender Health at the Department <strong>of</strong> Health toestablish current practice and policies <strong>in</strong> relation to <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong>currently <strong>in</strong> operation with<strong>in</strong> prisons <strong>in</strong> England and Wales.7

AimsThe ma<strong>in</strong> aims <strong>of</strong> this study were:• To determ<strong>in</strong>e current policies and practices <strong>in</strong> relation to <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> across the prison estate <strong>in</strong> England and Wales;• To explore the views <strong>of</strong> key stakeholders, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g prisoners and staff,regard<strong>in</strong>g the perceived barriers and benefits <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong>,and suggestions for improv<strong>in</strong>g practice; and• To identify examples <strong>of</strong> good practice and make recommendations abouthow <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> policies and practices might best be takenforward across the prison estate.MethodsThe study adopted a mixed-methods approach <strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g both qualitative andquantitative data. Data collection was divided <strong>in</strong>to two dist<strong>in</strong>ct phases:Phase 1 -Phase 2 -A national survey <strong>of</strong> all prison establishments <strong>in</strong> England and Walesto establish current practices <strong>in</strong> relation to <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> <strong>procedures</strong>.Semi-structured <strong>in</strong>terviews <strong>in</strong> 12 prisons to elicit pr<strong>of</strong>essional andservice user perspectives on <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong>ResultsQuestionnaire survey key f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs• A 90% response rate was achieved. Of those that responded, all reported tohave <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> operat<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong> their establishments to somedegree.• Fewer than half <strong>of</strong> all prisons (42%) had a written policy relat<strong>in</strong>g to theverification and prescription <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong> for newly received prisoners.However most prisons (78%) reported that they did aim to verifyprescriptions with<strong>in</strong> three days <strong>of</strong> reception <strong>in</strong>to custody.• Healthcare staff were the ma<strong>in</strong> contributors to the development <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> policies.• While the majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> policies <strong>in</strong>cluded sections onrisk assessment and monitor<strong>in</strong>g/review (87% and 71%), fewer detailedsecurity arrangements surround<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> and storage(29% and 24% respectively).• Most establishments (93%) used a structured risk assessment method forassess<strong>in</strong>g suitability for <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong>. However, these varied <strong>in</strong>8

terms <strong>of</strong> structure and the types <strong>of</strong> risk factors assessed. The vast majority(96%) specifically considered risk <strong>of</strong> suicide/self-harm.• The ma<strong>in</strong> prompts for review <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> were cl<strong>in</strong>ical factorsand/or changes to a patient’s condition or their environment. Twoestablishments (both open prisons) reported that they never reviewed <strong>in</strong><strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong>.• Just under half <strong>of</strong> establishments (44%) reported that they provided specificstorage facilities for <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong>. Local prisons and young<strong>of</strong>fender <strong>in</strong>stitutions were the least likely to provide storage facilities (20%and 29% respectively).• S<strong>in</strong>ce 2003, there has been an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> prisons that reportedhav<strong>in</strong>g a drug and therapeutic committee and <strong>in</strong> the number that used limitedprescrib<strong>in</strong>g lists. There had also been changes <strong>in</strong> the types <strong>of</strong> pharmacyproviders used, with decreased use <strong>of</strong> satellite prison pharmacies and<strong>in</strong>creased use <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dependent providers.Semi-structured <strong>in</strong>terviewsThe key f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from this section <strong>of</strong> the results can be summarised as follows.• The process <strong>of</strong> verify<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong> was seen to be complicated by severalfactors <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g external factors, prisoner factors and establishmentfactors.• Respondents argued <strong>in</strong> favour <strong>of</strong> a national/regional database which wouldallow <strong>in</strong>formation on a prisoner’s health and prescribed <strong>medication</strong> to beaccessed directly.• Respondents reported the value <strong>of</strong> prison staff foster<strong>in</strong>g stronger l<strong>in</strong>ks withcommunity healthcare providers or pharmacists.• Respondents stated that prisoners should be received from a smallercatchment area to improve communication with local primary care andpharmacy services.• Respondents’ personal experiences <strong>of</strong> the operation <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> at their establishment were generally positive.• Establishments varied accord<strong>in</strong>g to when people were risk assessed; someconducted the assessment at reception and others waited until the prisonerhad been assessed by a doctor.• Little consistency between establishments was found regard<strong>in</strong>g which staffwere responsible for the risk assessment process.• The majority <strong>of</strong> pharmacists <strong>in</strong>terviewed had somewhat negativeperceptions <strong>of</strong> current risk assessment processes. Generally, theyexpressed a view that risk was dynamic and that exist<strong>in</strong>g assessmentprocesses did not reflect this.9

• Respondents stated that risk assessment forms <strong>in</strong> current usage wereoutdated and not reflective <strong>of</strong> current prescrib<strong>in</strong>g practices.• There were concerns about the robustness <strong>of</strong> the risk assessment process;respondents commented that it was <strong>in</strong>sufficiently thorough or unduly<strong>in</strong>fluenced by subjective staff op<strong>in</strong>ion.• Staff respondents stated that it was common practice for prisoners to signa contract/compact promis<strong>in</strong>g not to trade or otherwise misuse their<strong>medication</strong> before <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> was sanctioned. However, prisonerrespondents frequently commented that they were unaware <strong>of</strong> the detailsor implications <strong>of</strong> such contracts.• Monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> was frequently viewed as acollaborative process, <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g security staff and the various cl<strong>in</strong>icalpr<strong>of</strong>essions.• Prisoners stated that the convenience <strong>of</strong> hav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong><strong>in</strong>creased the likelihood <strong>of</strong> them rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g concordant with treatmentregimes.• Barriers to <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> policies <strong>in</strong>cluded staff attitudes; prisonerattitudes, system difficulties and the prison environment.Recommendations• Supply<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> should be the default position <strong>in</strong>prisoners; justification should be required for opt<strong>in</strong>g out <strong>of</strong> this policy,rather than justification for opt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>.• Healthcare teams with<strong>in</strong> prisons should be aware <strong>of</strong> the open<strong>in</strong>g hours <strong>of</strong>local healthcare providers, ensur<strong>in</strong>g that they exploit fully those providerswhich do rema<strong>in</strong> open after 5pm on weekdays.• Busy local prisons should serve as small a local catchment area as possibleto facilitate <strong>in</strong>formation exchange with local healthcare providers.• Verify<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong> should be a rout<strong>in</strong>e task follow<strong>in</strong>g reception <strong>in</strong>tocustody, undertaken by discretely tasked staff.• Consideration should be given to an <strong>in</strong>formation campaign – for examplecirculat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation leaflets to local GP practices and other communityhealthcare providers – to expla<strong>in</strong> the role <strong>of</strong> prison healthcare teams andtheir status with<strong>in</strong> the NHS.• Medication education should be rout<strong>in</strong>ely <strong>of</strong>fered to prisoners provided bythe multi-discipl<strong>in</strong>ary healthcare team.• Cl<strong>in</strong>ical IT systems with<strong>in</strong> and outwith prisons should be shared, allow<strong>in</strong>gaccess to comprehensive patient <strong>in</strong>formation whether people are <strong>in</strong> or out <strong>of</strong>custody.• All prisons should be covered by a Drug and Therapeutics Committee orequivalent.10

• Medic<strong>in</strong>es, as a matter <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciple, should be held <strong>in</strong> the <strong>possession</strong> <strong>of</strong>prisoners.• Each prison establishment should have an <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> risk assessmentpolicy developed and ratified by the Drug and Therapeutics Committee, fordeterm<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, on an <strong>in</strong>dividual basis, any exceptions to the default<strong>possession</strong> <strong>of</strong> medic<strong>in</strong>es and related devices be<strong>in</strong>g held <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong>.• The development and implementation <strong>of</strong> a nationally ratified, evidencebased,structured pr<strong>of</strong>essional judgement risk assessment <strong>in</strong>strumentshould be considered to reduce <strong>in</strong>consistencies <strong>in</strong> risk assessmentprocesses. Assessment should be undertaken at a def<strong>in</strong>ed po<strong>in</strong>t afterreception, followed by a dynamic review process when cl<strong>in</strong>ical, patient orenvironmental changes occur.• All cells should have some form <strong>of</strong> lockable storage for <strong>medication</strong>.• All prisons should have a system <strong>of</strong> record<strong>in</strong>g adverse events.• Sufficient supplies <strong>of</strong> medic<strong>in</strong>es should be issued to prisoners to cover thewhole period they are <strong>in</strong> court or be<strong>in</strong>g transferred between establishments.• A policy <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> and risk assessment criteria, developed throughthe drug and therapeutics committee, and implemented <strong>in</strong> co-operation withprisoner escort services, should extend to those prisoners attend<strong>in</strong>g court oron transfer.11

1. Introduction1.1 BackgroundThe prevalence <strong>of</strong> physical and mental health problems is higher <strong>in</strong> prisons than <strong>in</strong>the general population. In a sample <strong>of</strong> adult male prisoners, 46% reported hav<strong>in</strong>gsome type <strong>of</strong> long stand<strong>in</strong>g illness or disability (Bridgwood & Malbon, 1995).Specifically, 10% <strong>of</strong> prisoners reported asthma, bronchitis or other respiratoryproblems and 15% <strong>of</strong> prisoners aged over 45 reported hav<strong>in</strong>g a heart or circulatoryillness (ibid).Plugge et al (2006) reported particularly high prevalence <strong>of</strong> physical ill health foradult women <strong>in</strong> remand prisons, with 83% report<strong>in</strong>g a longstand<strong>in</strong>g illness ordisability compared with 32% <strong>of</strong> the females <strong>in</strong> the general population. The mostcommon illnesses cited <strong>in</strong>cluded depression (57%) and anxiety and/or panicattacks (42%). Sexual health problems are common among prisoners; one selfreportstudy found that 22% <strong>of</strong> prisoners reported hav<strong>in</strong>g had a sexuallytransmitted <strong>in</strong>fection at some time <strong>in</strong> their life (Green et al, 2003). Rates <strong>of</strong> mentalillness are also noted to be particularly high <strong>in</strong> prisons, with 90% <strong>of</strong> all prisonershav<strong>in</strong>g a diagnosable mental health problem, personality disorder and/or substancemisuse problem (S<strong>in</strong>gleton et al, 1998).S<strong>in</strong>ce 1999, the NHS and HM Prison Service have been engaged <strong>in</strong> a cl<strong>in</strong>icalimprovement partnership based on the broad pr<strong>in</strong>ciple that prisoners should haveaccess to healthcare services <strong>of</strong> equivalent scope and quality as are available to thewider population. In terms <strong>of</strong> the current report, application <strong>of</strong> the pr<strong>in</strong>ciple <strong>of</strong>equivalence has contributed to developments <strong>in</strong> practices around ‘<strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong>’(IP) <strong>medication</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g that, when safe and appropriate, prisoner-patients shouldbe given autonomy and responsibility for the storage and adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> theirown <strong>medication</strong>. This contrasts with earlier rout<strong>in</strong>e practice whereby <strong>medication</strong>was generally only given <strong>in</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle, supervised doses (Bradley, 2007).The aim <strong>of</strong> this report is to evaluate current practices around the operation <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> policies with<strong>in</strong> prisons <strong>in</strong> England and Wales, and toexam<strong>in</strong>e potential ways <strong>of</strong> ensur<strong>in</strong>g the widest acceptability, safety and efficacy <strong>of</strong><strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> practices through the adoption <strong>of</strong> proven communitybasedstrategies, appropriately and proportionally adapted to take <strong>in</strong>to account thediscrete security and <strong>in</strong>stitutional <strong>in</strong>fluences operational with<strong>in</strong> prisons.12

1.2 In-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong> community andhospital sett<strong>in</strong>gsIn-<strong>possession</strong> prescription <strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong> the community is common practice forboth acute and chronic conditions, supplemented by the wide availability <strong>of</strong> nonprescription<strong>medication</strong> for m<strong>in</strong>or ailments. However, the ability to self adm<strong>in</strong>ister<strong>medication</strong> is not universal; for example some hospital wards do not allow <strong>in</strong>patientsto reta<strong>in</strong> supplies <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong>. In such cases even the most competent<strong>of</strong> patients who manage <strong>medication</strong> effectively at home may have it taken fromthem once <strong>in</strong> hospital and not returned until they are discharged (Dimond, 2004).Traditional practice on <strong>in</strong>-patient wards <strong>in</strong>volved the adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> drugs bynurs<strong>in</strong>g staff at set times throughout the day. Several problems have beenidentified with such drug rounds <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g issues with adm<strong>in</strong>ister<strong>in</strong>g medic<strong>in</strong>es atset times (Cous<strong>in</strong>s, 1992; Gaze, 1992); patients becom<strong>in</strong>g dependent on staff toreceive medic<strong>in</strong>es (Hassal, 1991); and a lack <strong>of</strong> education or advice on manag<strong>in</strong>gconditions upon discharge (Turton & Wilson, 1981).Such care systems potentially create patient “learned helplessness”, lead<strong>in</strong>g to aloss <strong>of</strong> skills relat<strong>in</strong>g to self care <strong>in</strong> general and <strong>medication</strong> management <strong>in</strong>particular (Dimond, 2004). They are also at odds with expectations outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> theNHS Plan, NMC Guidel<strong>in</strong>es for the Adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> Medic<strong>in</strong>es and Improv<strong>in</strong>gHealth <strong>in</strong> Wales (NHS, 2000; NMC, 2002; NHS Cymru Wales, 2001). Thesedocuments collectively agree that patients should be <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> decisions aroundthe prescription <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong>; be responsible for self-adm<strong>in</strong>istration; be educated<strong>in</strong> matters relat<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>medication</strong>; and take personal responsibility for its use.Patients self adm<strong>in</strong>ister<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong> with<strong>in</strong> hospital environments has beenreported to provide several benefits <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g patients reta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g control overmedic<strong>in</strong>e; patients hav<strong>in</strong>g the opportunity to practice tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong> undersupervision; healthcare staff be<strong>in</strong>g able to observe problems with adherence to<strong>medication</strong> regimes; improvements <strong>in</strong> patient morale; <strong>in</strong>creased patient comfort <strong>in</strong>relation to pa<strong>in</strong> relief and sleep (HCC, 2003); improved communication betweennurses and patients (Wade & Bowl<strong>in</strong>g, 1986); and improved adherence to drugregimes upon discharge (Baxendale et al, 1978; Bird, 1988; Webb et al, 1990).Furlong (1996) reported that 86% <strong>of</strong> their sample <strong>of</strong> hospital ward patientspreferred to keep control over their <strong>medication</strong> whilst <strong>in</strong> hospital. In a review <strong>of</strong>twelve empirical studies evaluat<strong>in</strong>g self-adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong>, Coll<strong>in</strong>gsworthet al (1997) reported that the most commonly reported disadvantage <strong>of</strong> patientsreta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g control <strong>of</strong> their <strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong> hospital sett<strong>in</strong>gs was under, rather thanover, adm<strong>in</strong>istration. No studies reported <strong>in</strong>cidents regard<strong>in</strong>g problems surround<strong>in</strong>gma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g security <strong>of</strong> patients’ <strong>medication</strong>, for example patients steal<strong>in</strong>g<strong>medication</strong>.The majority <strong>of</strong> self-adm<strong>in</strong>istration policies with<strong>in</strong> hospital sett<strong>in</strong>gs outl<strong>in</strong>eassessment stages for patients be<strong>in</strong>g considered for self-adm<strong>in</strong>istration as an <strong>in</strong>patient.The example below typifies the general content <strong>of</strong> self-adm<strong>in</strong>istrationpolicies <strong>in</strong> operation across NHS Trusts. Such policies allow patients to reta<strong>in</strong>13

control over the adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong>, depend<strong>in</strong>g upon satisfactoryassessment <strong>of</strong> their level <strong>of</strong> competence.• Stage 1 – One week’s supply <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong> is supplied to the ward <strong>in</strong>conta<strong>in</strong>ers conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g patient directions on the label. Medic<strong>in</strong>e is kept <strong>in</strong> thetrolley to be self-adm<strong>in</strong>istered <strong>in</strong> the presence <strong>of</strong> nurs<strong>in</strong>g staff.• Stage 2 - Individual day supplies sent to the ward <strong>in</strong> <strong>medication</strong> bags oranother form <strong>of</strong> packag<strong>in</strong>g designed to aid compliance and issued to thepatient.• Stage 3 – Two bags are supplied by pharmacy to be given to the patient,one with three days’ supply and the other with four days’ supply.• Stage 4 – Weekly supplies are issued to the patient.(Bolton, Salford, and Trafford Mental Health NHS Trust, 2006).The provision <strong>of</strong> drug <strong>in</strong>formation leaflets is an important aspect <strong>of</strong> selfadm<strong>in</strong>istration, <strong>in</strong> compliance with European Council Directive 92/27/EEC <strong>of</strong> 31March 1992 on the Labell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> Medic<strong>in</strong>al Products for Human Use and on PackageLeaflets (EEC, 1992). This stated that all medic<strong>in</strong>es supplied to patients should belabelled with a batch number and expiry date and be supplied with an <strong>in</strong>formationleaflet expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the <strong>medication</strong>’s use and risks <strong>in</strong> lay terms, <strong>in</strong> the appropriatelanguage. This would require consideration to be given to patients who havetrouble read<strong>in</strong>g labels and therefore may have issues follow<strong>in</strong>g directions. In suchcircumstances alternatives such as the use <strong>of</strong> symbols (e.g. moon and sun to<strong>in</strong>dicate adm<strong>in</strong>istration times) or colour codes along with verbal <strong>in</strong>struction on use<strong>of</strong> the <strong>medication</strong> should be employed, rather than simply us<strong>in</strong>g the difficulty as anexclusion criterion (HCC, 2003).1.3 Wider medic<strong>in</strong>es management and cl<strong>in</strong>icalgovernance issues encompass<strong>in</strong>g prison sett<strong>in</strong>gsIt is recommended <strong>in</strong> the document A Pharmacy Service for Prisoners (DH, 2003)that NHS medic<strong>in</strong>e management systems should be duplicated with<strong>in</strong> the prisonsystem, requir<strong>in</strong>g the development <strong>of</strong> medic<strong>in</strong>e management protocols cover<strong>in</strong>g arange <strong>of</strong> issues <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g:• The prescription, supply and adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong> adher<strong>in</strong>g withpolicies/protocols which ensure good pr<strong>of</strong>essional practice;• Non-medical prescrib<strong>in</strong>g;• Repeat prescrib<strong>in</strong>g;• Repeat dispens<strong>in</strong>g;• Management <strong>of</strong> chronic conditions and protocols for timely reviews <strong>of</strong>associated <strong>medication</strong>;• Return and disposal <strong>of</strong> unwanted or unused <strong>medication</strong>;• Establishment-wide formularies;14

• Procedures for access<strong>in</strong>g supplies out <strong>of</strong> hours;• Procedures for identify<strong>in</strong>g and report<strong>in</strong>g adverse <strong>in</strong>cidents and drugreactions;• Policies for the supply <strong>of</strong> non-prescription medic<strong>in</strong>es, through eitherhealthcare departments and/or prisoners’ shops; and• Accurate cl<strong>in</strong>ical record keep<strong>in</strong>g and developments <strong>in</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical <strong>in</strong>formationtechnology.Evaluat<strong>in</strong>g how effective medic<strong>in</strong>e management systems operate is an essentialpart <strong>of</strong> NHS cl<strong>in</strong>ical governance systems which seek to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> or improvestandards through exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g service quality, risk management and the monitor<strong>in</strong>g<strong>of</strong> new <strong>in</strong>itiatives (DH, 1999). Such cl<strong>in</strong>ical governance <strong>procedures</strong> apply equally tohealthcare services operat<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong> prisons. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical audit is a fundamental part <strong>of</strong>cl<strong>in</strong>ical governance, evaluat<strong>in</strong>g actual service delivery aga<strong>in</strong>st pre-def<strong>in</strong>edexpectations <strong>of</strong> quality conta<strong>in</strong>ed with<strong>in</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical policies. Similarly, systems torecord and learn from adverse <strong>in</strong>cidents are essential to improve patient and<strong>in</strong>stitutional safety.To help deliver appropriate governance, it is recommended that all prisonestablishments have a drug and therapeutic committee (DTC; DH, 2003). Thesecommittees should be multi-discipl<strong>in</strong>ary with members provid<strong>in</strong>g specialistexpertise from various backgrounds e.g. medic<strong>in</strong>e, pharmacy, and security. Thema<strong>in</strong> role <strong>of</strong> these committees is to develop local policies and <strong>procedures</strong> around<strong>medication</strong> and prescrib<strong>in</strong>g (NPC, 2005). Other responsibilities may <strong>in</strong>clude thedevelopment <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> formularies; review<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong>s’ overall suitabilityfor <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong>; production <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong>-specific disease managementguidel<strong>in</strong>es; the <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> new <strong>medication</strong>s; general prescrib<strong>in</strong>g policies; anddevelop<strong>in</strong>g risk assessment criteria to assess <strong>in</strong>dividual suitability for <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> (ibid). The National Prescrib<strong>in</strong>g Centre (NPC) outl<strong>in</strong>ed the <strong>in</strong>dividualsthat should be <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the development <strong>of</strong> prison-based <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> policies,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g:• Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians;• GPs, senior medical <strong>of</strong>ficers;• Healthcare managers/heads <strong>of</strong> healthcare, senior nurses;• Non-medical prescribers;• Governors;• Prison <strong>of</strong>ficers/ Prison Officers Association;• Special search team representative;• Independent Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Board;• W<strong>in</strong>g managers;• Mental health team leaders;• Service users;15

• PCT cl<strong>in</strong>ical governance leads;• PCT pharmaceutical/ prescrib<strong>in</strong>g advisers; and• PCT primary care development managers.Drug and therapeutic committees are also responsible for ensur<strong>in</strong>g adherence toPrison Service Order 3550 Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Services for Substance Misusers. This states that‘adm<strong>in</strong>istration and consumption <strong>of</strong> controlled drugs and other drugs subject tomisuse with<strong>in</strong> the prison must be directly observed’ (HMPS, 2000), thus remov<strong>in</strong>gsuch drugs from any consideration <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> adm<strong>in</strong>istration. Drugs with thehighest potential for misuse are likely to have a high currency value <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong>illicit trad<strong>in</strong>g by prisoners, therefore the security implications <strong>of</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g them topatients <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> is generally agreed to be too great (NPC, 2005).1.4 Rationale for <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong> the prisonsett<strong>in</strong>gWith<strong>in</strong> prison establishments, the adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong> may require apatient to be escorted to the healthcare centre, wait or queue by a <strong>medication</strong>hatch or gated cl<strong>in</strong>ic, expla<strong>in</strong> the need for their <strong>medication</strong>, wait for verificationthat this is acceptable and have a s<strong>in</strong>gle dose issued by healthcare staff (DH,2003). Several problems have been identified with such <strong>procedures</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g:• Nurses spend<strong>in</strong>g large amounts <strong>of</strong> time prepar<strong>in</strong>g and adm<strong>in</strong>ister<strong>in</strong>gprescribed drug regimens when their skills could be better employed <strong>in</strong>other areas;• Healthcare staff adm<strong>in</strong>ister<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong>s to large populations <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>tenunfamiliar <strong>in</strong>dividuals lead<strong>in</strong>g to the risk <strong>of</strong> drug adm<strong>in</strong>istration errors;• Fixed adm<strong>in</strong>istration times limit<strong>in</strong>g the ability to adm<strong>in</strong>ister <strong>medication</strong> atoptimum times, for example with food, or at night;• A lack <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> results <strong>in</strong> an absence <strong>of</strong> standardised riskassessment;• Frequent changes to prisoners’ locations, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> adm<strong>in</strong>istrativeproblems;• Patients be<strong>in</strong>g moved around the prison estate, potentially result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>terruptions to the supply <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong> or <strong>medication</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g lost or mislaid;• S<strong>in</strong>gle dose adm<strong>in</strong>istration creates a culture <strong>of</strong> dependence likely to causeproblems when the prisoner is released back <strong>in</strong>to the community; and• Time consum<strong>in</strong>g <strong>procedures</strong> <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle dose adm<strong>in</strong>istration can<strong>in</strong>terrupt prisoners’ engagement <strong>in</strong> educational and vocational activities (DH,2003; NPC, 2005).The rationale beh<strong>in</strong>d develop<strong>in</strong>g and implement<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong><strong>procedures</strong> with<strong>in</strong> prison sett<strong>in</strong>gs centres around an assumption that patients <strong>in</strong>prison should be treated as responsible people and be empowered to take an active16

ole <strong>in</strong> their own care (DH, 2003). Policies for <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> should bebased on an assumption that prisoners suffer<strong>in</strong>g from long term conditions arelikely to have an understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> how to manage their own health problems andunderstand the implications <strong>of</strong> self-adm<strong>in</strong>istrat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong> (South StaffordshirePCT, 2007).However, prison environments engender <strong>in</strong>herent tensions between ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gthe security <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>stitution as a whole, and encourag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividuals to acceptresponsibility for their lives and choices. This is highlighted by the issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> which, anecdotally, creates feel<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> unease <strong>in</strong> staffstemm<strong>in</strong>g from fears that medic<strong>in</strong>es will be abused, traded, stolen or used to selfharm/commitsuicide through overdose (Bradley, 2007; Simpson & Shah, 2006).However, it has been reported that, at a time when over 90% <strong>of</strong> prisons operated<strong>in</strong> <strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> <strong>procedures</strong>, proportionally few <strong>in</strong>cidents <strong>of</strong> self-harmwere a result <strong>of</strong> prisoners poison<strong>in</strong>g themselves with their own, or someone else’s,<strong>medication</strong> (Adeniji, 2003).The potential benefits <strong>of</strong> employ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> systems with<strong>in</strong> prison sett<strong>in</strong>gs<strong>in</strong>clude:• Prisoners tak<strong>in</strong>g an active role <strong>in</strong> manag<strong>in</strong>g their own care;• Medic<strong>in</strong>es be<strong>in</strong>g adm<strong>in</strong>istered at appropriate times;• Increased <strong>in</strong>formation for prisoners about their health problems;• Improved and more equitable relations between prisoners and staff;• Increased co-operation between healthcare staff and prisoners;• Improved health outcomes;• Time reductions <strong>in</strong> wait<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>medication</strong>s at treatment <strong>in</strong>tervals; and• Reduc<strong>in</strong>g the chances <strong>of</strong> miss<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong> upon transfer, when at courtetc.Queu<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>medication</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g treatment <strong>in</strong>tervals several times a day can also bea daunt<strong>in</strong>g experience for some patients, perhaps particularly the old and frail whomay fear details <strong>of</strong> the <strong>medication</strong> they receive becom<strong>in</strong>g known to possiblypredatory prisoners (NPC, 2005). Supply<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> can tacklethis, <strong>in</strong>crease confidentiality and reduce opportunities for bully<strong>in</strong>g. Follow<strong>in</strong>grelease, better health outcomes may be obta<strong>in</strong>ed if people have practised the skillsand discipl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> concordance with treatment whilst <strong>in</strong> prison (NPC, 2005; Pike,2005).It is not only patients who benefit from the implementation <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> policies with<strong>in</strong> prisons; healthcare staff can also improve work<strong>in</strong>gpractices, for example:• M<strong>in</strong>imis<strong>in</strong>g the time and staff<strong>in</strong>g required to adm<strong>in</strong>ister <strong>in</strong>dividual doses atset times;• Develop<strong>in</strong>g more efficient systems for the supply <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong>s;• Increased mean<strong>in</strong>gful contact with patients;17

• Improved medic<strong>in</strong>e management systems;• Increased job satisfaction; and• Safer adm<strong>in</strong>istration <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong> (NPC, 2005).Changes <strong>in</strong> time commitments provides an opportunity to redeploy resources andfor staff to make better use <strong>of</strong> their skills or enhance their tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. This could<strong>in</strong>clude time spent on activities such as review<strong>in</strong>g patient <strong>medication</strong>s, healthpromotion and/or ga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g new skills <strong>in</strong> supplementary prescrib<strong>in</strong>g and manag<strong>in</strong>gm<strong>in</strong>or conditions (ibid).<strong>An</strong>other benefit <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> policies may br<strong>in</strong>g is a change to prison culturethrough reduc<strong>in</strong>g the perceived value <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong>. Prisoners generally regard<strong>medication</strong> as hav<strong>in</strong>g a high potential trad<strong>in</strong>g value, largely due to a belief that all<strong>medication</strong> provides elation, pleasure and bestows status. However, if it iscommonly understood that <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> medic<strong>in</strong>es are <strong>in</strong>herently not <strong>of</strong> abusevalue, this may improve prisoners’ overall approach to, and knowledge <strong>of</strong>,<strong>medication</strong> (DH, 2003). Furthermore, by improv<strong>in</strong>g patients’ understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> how<strong>medication</strong> works and what role it plays <strong>in</strong> treat<strong>in</strong>g conditions, it may be possible toreduce or prevent cases whereby <strong>medication</strong>s are stolen, traded or hoarded (NPC,2005).1.5 Prison based <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> policiesNumerous guidel<strong>in</strong>es and policy documents have been produced both with<strong>in</strong> theprison system and by other organisations around the need to empower patients totake an active role <strong>in</strong> their own care. This was a key theme outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> The NHSPlan (NHS, 2000) and, <strong>in</strong> 2003, was adopted by HM Prison Service as the pr<strong>in</strong>cipleobjective for the document A Pharmacy Service for Prisoners, which highlighted theneed to provide a more patient-focused primary care pharmacy service centred onidentified needs and promot<strong>in</strong>g self care (DH, 2003).It is currently recommended that, with<strong>in</strong> prisons, <strong>medication</strong> and anyaccompany<strong>in</strong>g adm<strong>in</strong>istration or monitor<strong>in</strong>g device should normally be held <strong>in</strong><strong>possession</strong>as a matter <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciple (Bradley, 2007). Furthermore, prisons aredirected toward implement<strong>in</strong>g systems for the modernisation <strong>of</strong> pharmacy servicesby sett<strong>in</strong>g a number <strong>of</strong> goals and objectives <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g:• Identify<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividual and collective patient need to assist development <strong>of</strong>more patient-focused services;• Improv<strong>in</strong>g access to pharmacy services for prisoners;• Develop<strong>in</strong>g pharmacy services which encourage and support patient selfcare;• Establish<strong>in</strong>g efficient delivery service systems for the supply <strong>of</strong> medic<strong>in</strong>es;• Integrat<strong>in</strong>g prison-based pharmacy services <strong>in</strong>to other healthcare services;• M<strong>in</strong>or ailment and <strong>medication</strong> advice cl<strong>in</strong>ics provided through pharmacyservices;• Provid<strong>in</strong>g telephone advice by pharmacists;18

• Provision <strong>of</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ics cover<strong>in</strong>g a range <strong>of</strong> topics e.g. smok<strong>in</strong>g cessation,asthma, diabetes etc;• Support<strong>in</strong>g other healthcare staff <strong>in</strong> their roles and duties;• Effectively utilis<strong>in</strong>g staff resources and medic<strong>in</strong>es to promote costeffectiveness; and• Develop<strong>in</strong>g and improv<strong>in</strong>g services through cl<strong>in</strong>ical governance (DH, 2003).The document Medication <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong>: a guide to improv<strong>in</strong>g practice <strong>in</strong> secureenvironments, produced by the National Prescrib<strong>in</strong>g Centre <strong>in</strong> 2005, explored therecommendations and pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> detailed <strong>in</strong> APharmacy Service for Prisoners, exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the benefits for prisoners and staff(Pike, 2005). Furthermore, it discussed the practical issues to be considered whendevelop<strong>in</strong>g and implement<strong>in</strong>g a local <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> policy whilst also sett<strong>in</strong>gprimary objectives outl<strong>in</strong>ed as:• Support for local prison/PCT partnerships <strong>in</strong> mov<strong>in</strong>g to a position whereby itbecomes the norm for patients located with<strong>in</strong> prisons to possess and usetheir own <strong>medication</strong>;• The promotion and dissem<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> good practice around <strong>medication</strong>management; and• The standardisation <strong>of</strong> approach towards <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> acrossthe prison sector, acknowledg<strong>in</strong>g that each will be start<strong>in</strong>g from a differentbasel<strong>in</strong>e and use different methods to implement <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong>that may be appropriate to the local sett<strong>in</strong>g (Pike, 2005).This report also recommended that <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> policies and riskassessment criteria apply to patients be<strong>in</strong>g transferred to other establishments orotherwise under escort e.g. to court or police <strong>in</strong>terviews (DH, 2003).Guidel<strong>in</strong>es for <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> were also outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the 2008 documentExpectations: Criteria for assess<strong>in</strong>g the conditions <strong>in</strong> prisons and the treatment <strong>of</strong>prisoners produced by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate <strong>of</strong> Prisons (HMCIP). Thisdocument outl<strong>in</strong>ed the particular standards aga<strong>in</strong>st which HMCIP measureseveryday aspects <strong>of</strong> a prisoner’s life, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g health and pharmacy services.Specifically with regards to <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong>, it noted that prisonhealthcare departments should provide community based services on the w<strong>in</strong>gs forthose suffer<strong>in</strong>g from chronic mental and physical conditions to promote<strong>in</strong>dependence (ibid). The policies discussed also cover the important issues <strong>of</strong> thesafe packag<strong>in</strong>g and storage <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong>.1.6 Risk assessments & reviews <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong>All activities with<strong>in</strong> prisons are rout<strong>in</strong>ely subject to risk assessment andmanagement, with vary<strong>in</strong>g degrees <strong>of</strong> formality. The National Prescrib<strong>in</strong>g Centre(2005) list a number <strong>of</strong> factors to be taken <strong>in</strong>to consideration when develop<strong>in</strong>g arisk assessment tool for determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>dividual’s suitability for <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong>. These factors can be grouped <strong>in</strong>to three ma<strong>in</strong> categories, relat<strong>in</strong>g topatient, cl<strong>in</strong>ical and environmental factors (Box 1).19

Currently with<strong>in</strong> prison healthcare practice, there is no national, validated riskassessment tool for <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong>. Rather, it has been advised thateach prison should develop its own tool, tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to account specific issues at thatparticular establishment (NPC, 2005). For example, <strong>in</strong> local prisons with high levels<strong>of</strong> transfer activity, patients may be less settled and less well known to staff, thuslocal risk management needs to specifically consider these factors (Pike, 2005).Risk assessment <strong>procedures</strong> should formalise circumstances which trigger review,for example failure to attend a cl<strong>in</strong>ic, proposed or imm<strong>in</strong>ent transfer or apotentially destabilis<strong>in</strong>g change <strong>in</strong> legal status (NPC, 2005).Box 1: Factors to be considered for risk assessment toolsPatient-related factors• Will<strong>in</strong>gness to take responsibility for own <strong>medication</strong>s• Cognitive ability to understand medical condition and <strong>medication</strong>• Age, e.g. children & young people• Risk <strong>of</strong> self-harm, tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to account past behaviour and knowncurrent circumstances — such as those prisoners currently be<strong>in</strong>gmanaged as at specific risk• History <strong>of</strong> drug misuse• History <strong>of</strong> trad<strong>in</strong>g/hoard<strong>in</strong>g• Vulnerability to violence/bully<strong>in</strong>g• History or tendency to violence/bully<strong>in</strong>g• <strong>An</strong>tisocial, explosive or impulsive personality traits• Prisoner status or change <strong>in</strong> status, e.g. sentenced/remandCl<strong>in</strong>ical and <strong>medication</strong>-related factors• Choice <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong>, e.g. tricyclic anti-depressant or selectiveseroton<strong>in</strong> re-uptake <strong>in</strong>hibitor• Flammability <strong>of</strong> preparation and potential for its misuse• Potential for harm from excess or missed doses• Stability <strong>of</strong> medical condition• Monitor<strong>in</strong>g requirements• Concordance/compliance with previous treatments• Duration <strong>of</strong> treatment required, i.e. acute or chronic need• Frequency <strong>of</strong> adm<strong>in</strong>istration, i.e. as required use or regular dos<strong>in</strong>g• Access to over-the-counter medic<strong>in</strong>es, i.e. from canteen list• Suitability <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong> to be stored <strong>in</strong> a cell environment• Suitability <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong> packag<strong>in</strong>g, e.g. glass”NPC (2005), p36-7The type <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g prescribed is also highlighted as an important factorwhen assess<strong>in</strong>g risk; some medic<strong>in</strong>es have higher toxicity and therefore eithercannot be given <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong>, or only with caution. Prisons have, therefore,rout<strong>in</strong>ely developed local formularies that detail the types <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong> that canand cannot be supplied <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong>.20

Risk assessments also need to take <strong>in</strong>to account the length <strong>of</strong> supply permitted.Hirst (2004) identified four broad categories for outcomes <strong>of</strong> prison-based<strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> risk assessment processes:1. Not <strong>in</strong> IP;2. IP, no more than seven days supply;3. IP, no more than 14 days supply; and4. IP, no more than 28 days supply.In addition to <strong>in</strong>dividual patient variables, length <strong>of</strong> supply is also <strong>in</strong>fluenced byprison factors. Given that local prisons have high population turnover, there isgreater potential for wastage <strong>of</strong> medic<strong>in</strong>es. Therefore, local prisons rout<strong>in</strong>ely<strong>in</strong>itially assess patients for seven days <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> with<strong>in</strong> their firstweek <strong>in</strong> custody (ibid). Follow<strong>in</strong>g this, length <strong>of</strong> supply may be extended for up to28 days. However, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g prisons, with generally stable populations, usuallyassess prisoners for 28 days <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> with<strong>in</strong> their first week (ibid).Once a decision regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> has been reached, stepsshould be taken to ensure that all parties <strong>in</strong>volved, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the patient,understand their roles and responsibilities (NPC, 2005). As part <strong>of</strong> this process,patient <strong>in</strong>formation leaflets and any other relevant <strong>in</strong>formation, such as specific<strong>medication</strong> and/or dos<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>structions, should be made available. These shouldtake <strong>in</strong>to account any language or literacy difficulties (NPC, 2005). <strong>An</strong>y concernsthe patient may have about hold<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>possession</strong> should be addressedas part <strong>of</strong> the decision mak<strong>in</strong>g process and <strong>in</strong>formed consent. Prisoners are <strong>of</strong>tenrequired to sign a contract/compact outl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g their understand<strong>in</strong>g and agreementwith their responsibilities <strong>in</strong> the process. Such compacts rout<strong>in</strong>ely conta<strong>in</strong> clausesoutl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the consequences <strong>of</strong> non-compliance, such as discipl<strong>in</strong>ary action or thewithdrawal <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> (Simpson, 2005). Expectations <strong>of</strong> prisonersgenerally cover the follow<strong>in</strong>g areas:• Ensur<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>medication</strong> is taken only as directed by healthcare staff;• Individual responsibility for correct storage <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong>;• The return <strong>of</strong> unused <strong>medication</strong> to healthcare staff; and• A ban on trad<strong>in</strong>g or sell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong> (ibid).Obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formed compliance with compacts from juvenile or young <strong>of</strong>fendersand those with serious mental illness or learn<strong>in</strong>g disabilities requires specialconsideration. Those aged over 16 years are, <strong>in</strong> the majority <strong>of</strong> cases, deemedcompetent to consent to treatment. Legal precedent dictates that young peopleunder the age <strong>of</strong> 16 are deemed competent to consent to treatment or particular<strong>in</strong>terventions if they demonstrate a sufficient understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the medical carethat is advised (NPC, 2005). This capacity to consent requires assessment and issimilar for patients with learn<strong>in</strong>g difficulties (DH, 2001).The NPC (2005) stated that risk assessment tools only act to guide decisionmak<strong>in</strong>grather than straightforwardly determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>al outcomes. A multidiscipl<strong>in</strong>aryapproach to risk assessment is advised, requir<strong>in</strong>g the consideration <strong>of</strong>the op<strong>in</strong>ions <strong>of</strong> all <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the care and custody <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dividual as one group21

<strong>of</strong> staff may have access to pert<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>in</strong>formation not generally available to otherworkers.It is also noted that any risk assessment tool only provides an assessment at aparticular po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> time; therefore it is important that criteria are identified for thecircumstances when it is necessary to review <strong>medication</strong> or to repeat riskassessments (Hirst, 2004). The assessment <strong>of</strong> risk should be an ongo<strong>in</strong>g process;an event such as bad news for a patient could <strong>in</strong>crease risk, therefore it may bethat it is no longer considered safe for the <strong>in</strong>dividual to be responsible for their<strong>medication</strong> (Pike, 2005). Furthermore it has been recommended that riskassessments are tailored to the <strong>in</strong>dividual and that a “one size fits all” approach is<strong>in</strong>advisable (Bradley, 2007). Along with formal risk assessment <strong>procedures</strong>,regular cl<strong>in</strong>ical review, def<strong>in</strong>ed as a structured, critical exam<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> patients’<strong>medication</strong>s, are essential to good practice with regards to <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> (NPC, 2002).Different approaches and levels to perform<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong> reviews have beendescribed <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g:• Level 1: Pr<strong>of</strong>essionals scrut<strong>in</strong>is<strong>in</strong>g the list <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong>s patients arereceiv<strong>in</strong>g to identify potential problems and anomalies;• Level 2: Utilis<strong>in</strong>g patients full medical notes to review medic<strong>in</strong>es; and• Level 3: Conduct<strong>in</strong>g a full face-to-face cl<strong>in</strong>ical review where medic<strong>in</strong>es areevaluated <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> the condition and the patient’s lifestyle (NPC, 2002).The National Prescrib<strong>in</strong>g Centre recommends that pharmacy services are <strong>in</strong>cludedwhen perform<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong> reviews on patients (ibid)1.7 Packag<strong>in</strong>g and storage issuesThe importance <strong>of</strong> packag<strong>in</strong>g was first recognised <strong>in</strong> 1968 by the RoyalPharmaceutical Society <strong>of</strong> Great Brita<strong>in</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Standards Inspectors. Theystated that, follow<strong>in</strong>g the Medic<strong>in</strong>es Act <strong>of</strong> 1968, a properly dispensed medic<strong>in</strong>emust be appropriately packaged or dispensed by a qualified pharmacist (Williams,1999). In-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong> prisons is rout<strong>in</strong>ely supplied <strong>in</strong> a variety <strong>of</strong>types <strong>of</strong> packag<strong>in</strong>g, for example cardboard cartons, plastic bottles and monitoreddosage packs (DH, 2003).Difficulties experienced by patients <strong>in</strong> remember<strong>in</strong>g to take their <strong>medication</strong>s canbe addressed by supply<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong> its orig<strong>in</strong>al packag<strong>in</strong>g. Manufacturers<strong>of</strong>ten supply packs which cover commonly prescribed courses <strong>of</strong> treatment, forexample rout<strong>in</strong>e regimens <strong>of</strong> antibiotics. Therefore blister packs can be speciallyprepared and supplied to assist patients’ drug regimes (NPC, 2005). Us<strong>in</strong>g differentconta<strong>in</strong>ers/packag<strong>in</strong>g to the orig<strong>in</strong>al can be costly <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> the time needed toprepare and re-package medic<strong>in</strong>e and can potentially cause problems <strong>in</strong> identify<strong>in</strong>gthe <strong>medication</strong>, requir<strong>in</strong>g extra care to ensure that all appropriate patient<strong>in</strong>formation is provided (DH, 2003). Us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong> the orig<strong>in</strong>al packag<strong>in</strong>g alsohas the advantage <strong>of</strong> meet<strong>in</strong>g both the <strong>in</strong>formation requirements and labell<strong>in</strong>gcriteria required under medic<strong>in</strong>es legislation. Therefore, the Department <strong>of</strong> Healthrecommends that medic<strong>in</strong>es should generally be provided <strong>in</strong> the orig<strong>in</strong>al patient22

packs sent from the supplier. Monitored dosage systems are suggested for use onan <strong>in</strong>dividual needs-led basis (ibid). Furthermore, accord<strong>in</strong>g to guidel<strong>in</strong>es set bythe National Prescrib<strong>in</strong>g Centre, <strong>medication</strong> should be dispensed <strong>in</strong> a clearlylabelled conta<strong>in</strong>er detail<strong>in</strong>g the name <strong>of</strong> the <strong>medication</strong>; date dispensed; addresswhere dispensed; quantity; dosage <strong>in</strong>structions; strength; date <strong>of</strong> issue; person towho supplied; and any cautionary warn<strong>in</strong>gs (NPC, 2005).Safe and appropriate storage is also a vital consideration when implement<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> as medic<strong>in</strong>es not stored securely can potentially pose risk toothers. Various approaches to this issue have been taken; with<strong>in</strong> hospitals and carehomes <strong>medication</strong>s are rout<strong>in</strong>ely kept <strong>in</strong> lockable cupboards. However, options forthe safe storage <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong> with<strong>in</strong> prisons may be more problematic. Patients <strong>in</strong>s<strong>in</strong>gle cells can ensure their door is locked when they are not there; however those<strong>in</strong> shared cells may have the risk <strong>of</strong> their <strong>medication</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g readily accessible toanother prisoner (Pike, 2005). There are establishments that have alreadyprovided lockable cupboards with<strong>in</strong> shared cells, although the use <strong>of</strong> an additionallocked storage place <strong>in</strong> the cell may impact upon the time taken by w<strong>in</strong>g staff toconduct cell searches (ibid). Specific consideration is required for <strong>medication</strong> whichneeds to be stored under particular conditions, for example items requir<strong>in</strong>grefrigeration.1.8 Evidence <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong> practiceA case study documented <strong>in</strong> A Pharmacy Service for Prisoners gave details <strong>of</strong> threeestablishments (one category B/C, one category C and one dispersal prison) whichprovided nearly all <strong>medication</strong> on an <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> basis. None <strong>of</strong> theestablishments demonstrated a higher level <strong>of</strong> harm connected with medic<strong>in</strong>e usecompared to prisons with more limited or no <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong>. It was alsonoted that, as a consequence <strong>of</strong> the accompany<strong>in</strong>g streaml<strong>in</strong>ed adm<strong>in</strong>istrativeprocesses around <strong>medication</strong>, healthcare provision developed positively <strong>in</strong> otherareas such as healthcare staff be<strong>in</strong>g able to utilise the full range <strong>of</strong> their skills andexpertise and improved operation and staff<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ics (DH, 2003).In contrast, problems encountered by prison pharmacy services and patients weredocumented <strong>in</strong> a case study detail<strong>in</strong>g a patient suffer<strong>in</strong>g from diabetes when<strong>medication</strong> was not supplied IP. Issues highlighted centred on the order<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong><strong>medication</strong> which was noted to be sporadic. Cont<strong>in</strong>uous escort<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the patient toreceive <strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>jections was required and problems fitt<strong>in</strong>g this <strong>in</strong> around otherduties performed by both healthcare and discipl<strong>in</strong>e staff were also outl<strong>in</strong>ed (DH,2003). In contrast, the patient’s treatment follow<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> an <strong>in</strong><strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> policy was also detailed. Follow<strong>in</strong>g appropriate assessment,the patient was allowed to self-adm<strong>in</strong>ister <strong>medication</strong>, us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>ject<strong>in</strong>g equipmentstored <strong>in</strong> cell. Other advantages to the patient <strong>in</strong>cluded the successful operation <strong>of</strong>a repeat prescrib<strong>in</strong>g system similar to that conducted with<strong>in</strong> GP surgeries andattendance at a chronic disease management cl<strong>in</strong>ic where their treatment wasreviewed jo<strong>in</strong>tly by medical and pharmacy staff. Furthermore, with <strong>medication</strong>supplied directly to the patient, pharmacy staff had an opportunity to provideadditional pr<strong>of</strong>essional advice. Discipl<strong>in</strong>e staff resources could also be more usefullyredeployed due to the reduction <strong>in</strong> escorts required (DH, 2003).23

1.9 The next stepA major challenge with<strong>in</strong> prisons is that <strong>of</strong> alter<strong>in</strong>g negative perceptions regard<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> and alter<strong>in</strong>g a generally risk averse culture to one that isrisk aware and capable <strong>of</strong> pro-active risk management. This is vital <strong>in</strong> build<strong>in</strong>gprison/health partnerships with the goal <strong>of</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividual responsibility(Bradley, 2007). By harness<strong>in</strong>g a multi-discipl<strong>in</strong>ary approach regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> policies, effective medic<strong>in</strong>es management systems can beusefully employed. It is vital that this is communicated to, and embraced by, allprison staff, not just healthcare staff, thus achiev<strong>in</strong>g a balance <strong>of</strong> security, safety,economic and health related factors (ibid).1.10 Research aimsThe study was commissioned by the department <strong>of</strong> Offender Health at theDepartment <strong>of</strong> Health (DH) to exam<strong>in</strong>e current practices around <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> <strong>in</strong> prison sett<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> England and Wales.The study had three aims:• To determ<strong>in</strong>e current policies and practices <strong>in</strong> relation to <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> across the prison estate <strong>in</strong> England and Wales;• To explore the views <strong>of</strong> key stakeholders, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g prisoners and staff,regard<strong>in</strong>g the perceived barriers and benefits <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong>,and suggestions for improv<strong>in</strong>g practice; and• To identify good practice and make recommendations on how <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> policies and practices might best be taken forward across theprison estate.24

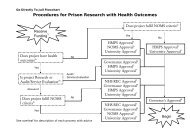

2. MethodThe study adopted a mixed-methods approach <strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g both qualitative andquantitative data. Data collection was divided <strong>in</strong>to two dist<strong>in</strong>ct phases:Phase 1 -Phase 2 -A national survey <strong>of</strong> all prison establishments <strong>in</strong> England and Walesto establish current practices <strong>in</strong> relation to <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong><strong>medication</strong> <strong>procedures</strong>.Semi-structured <strong>in</strong>terviews <strong>in</strong> 12 prisons to elicit pr<strong>of</strong>essional andservice user perspectives on <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong>2.1 Phase 1: National surveyA national survey <strong>of</strong> prisons <strong>in</strong> England and Wales was undertaken <strong>in</strong> order toestablish current practices regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> across the prisonestate and between different categories <strong>of</strong> prison establishment.Survey designA 24-item survey was developed specifically for the study (see Appendix 1)compris<strong>in</strong>g questions <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g areas:Establishment <strong>in</strong>formation -Prison name; job title <strong>of</strong> staff membercomplet<strong>in</strong>g the survey.Verification <strong>of</strong> <strong>medication</strong>- Policies for verify<strong>in</strong>g <strong>medication</strong> upon aperson’s reception <strong>in</strong>to custody and firstnight/early custody prescrib<strong>in</strong>g protocols.Medication <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> -Use and limits <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong>;policy development; risk assessment;development <strong>of</strong> establishment formularies;prescrib<strong>in</strong>g; <strong>medication</strong> storage facilities;provision <strong>of</strong> pharmacy services; and barriersto implement<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong>.In addition to closed and Likert-scale questions, a number <strong>of</strong> free text boxes were<strong>in</strong>cluded for respondents to provide further details <strong>of</strong> current challenges associatedwith <strong>in</strong>-<strong>possession</strong> <strong>medication</strong> and/or examples <strong>of</strong> good practice.25