Update on the serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma - Anatomia ...

Update on the serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma - Anatomia ...

Update on the serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma - Anatomia ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Human Pathology (2010) xx, xxx–xxxwww.elsevier.com/locate/humpathProgress in pathology<str<strong>on</strong>g>Update</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>serrated</strong> <strong>pathway</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong>Dale C. Snover MD ⁎Department of Pathology, Fairview Southdale Hospital, Hibbing, MN 55746, USADepartment of Labora<strong>to</strong>ry Medicine and Pathology, The University of Minnesota Medical School, Edina, MN 55435, USAReceived 7 May 2010; revised 11 June 2010; accepted 16 June 2010Keywords:Col<strong>on</strong> adeno<strong>carcinoma</strong>;Serrated <strong>pathway</strong>;Sessile <strong>serrated</strong> adenoma;Traditi<strong>on</strong>al <strong>serrated</strong>adenoma;Hyperplastic polypSummary Adeno<strong>carcinoma</strong> of <strong>the</strong> large intestine can no l<strong>on</strong>ger be c<strong>on</strong>sidered <strong>on</strong>e disease but ra<strong>the</strong>r afamily of diseases with different precursor lesi<strong>on</strong>s, different molecular <strong>pathway</strong>s, and different end-stage<strong>carcinoma</strong>s with varying prognoses. Approximately 60% of <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong>s arise fromc<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al adenomas via <strong>the</strong> suppressor <strong>pathway</strong> leading <strong>to</strong> microsatellite stable <strong>carcinoma</strong>s. These<strong>carcinoma</strong>s represent <strong>the</strong> <strong>pathway</strong> that has been <strong>the</strong> target of screening and preventi<strong>on</strong> programs <strong>to</strong> date.However, approximately 35% of <strong>carcinoma</strong>s arise al<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>serrated</strong> <strong>pathway</strong> developing from <strong>the</strong>precursor lesi<strong>on</strong> known as <strong>the</strong> sessile <strong>serrated</strong> adenoma (also referred <strong>to</strong> as <strong>the</strong> sessile <strong>serrated</strong> polyp).Sessile <strong>serrated</strong> adenomas/polyps lead <strong>to</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong>s with extensive CpG island promoter methylati<strong>on</strong>(CpG island methylated phenotype positive <strong>carcinoma</strong>s), which can be ei<strong>the</strong>r microsatellite instable highor microsatellite stable. The remaining 5% of <strong>carcinoma</strong>s arise from c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al adenomas in patientswith germ line mutati<strong>on</strong>s of mismatch repair genes (Lynch syndrome), leading <strong>to</strong> CpG islandmethylated phenotype negative microsatellite instable <strong>carcinoma</strong>s. Carcinomas arising from sessile<strong>serrated</strong> adenomas/polyps are not prevented by removing c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al adenomas and hence may bemissed in routine screening programs. In additi<strong>on</strong>, a subset of <strong>the</strong>se lesi<strong>on</strong>s may potentially progressrapidly <strong>to</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong>; hence, it is likely that <strong>the</strong>se lesi<strong>on</strong>s will require a different screening strategy fromthat used for c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al adenomas. This article reviews <strong>the</strong> various <strong>pathway</strong>s <strong>to</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong>with emphasis <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>serrated</strong> <strong>pathway</strong> and evaluates <strong>the</strong> implicati<strong>on</strong>s of this <strong>pathway</strong> for <strong>colorectal</strong><strong>carcinoma</strong>s screening programs.© 2010 Published by Elsevier Inc.1. Introducti<strong>on</strong>Colorectal <strong>carcinoma</strong> is a major health issue in <strong>the</strong> UnitedStates, representing <strong>the</strong> sec<strong>on</strong>d most comm<strong>on</strong>ly fatalmalignancy after lung. Although it is often assumed thatalmost all <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong>s arise from c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>aladenomas via <strong>the</strong> suppressor <strong>pathway</strong> initiated with amutati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> APC gene (<strong>the</strong> Fear<strong>on</strong>-Vogelstein model),it is now clear that this <strong>pathway</strong> accounts for <strong>on</strong>lyapproximately 60% of col<strong>on</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong> [1,2]. Most of <strong>the</strong>⁎ Department of Pathology, Fairview Southdale Hospital.E-mail address: snoverd@umn.edu.remaining 40% is accounted for by <strong>the</strong> more recentlydescribed <strong>serrated</strong> <strong>pathway</strong> leading <strong>to</strong> CpG island methylatedphenotype (CIMP+) <strong>carcinoma</strong> (approximately 35%), with<strong>the</strong> remaining 5% arising via <strong>the</strong> muta<strong>to</strong>r <strong>pathway</strong> in Lynchsyndrome [2]. Trying <strong>to</strong> understand <strong>the</strong> multiplicity of<strong>pathway</strong>s is c<strong>on</strong>fused by a plethora of overlapping ways <strong>to</strong>describe <strong>the</strong>se <strong>pathway</strong>s and cancers. Pathways have beendefined by <strong>the</strong> presumed initiating fac<strong>to</strong>r (ie, suppressor[chromosome instability] versus muta<strong>to</strong>r [microsatelliteinstability] <strong>pathway</strong>s) and by <strong>the</strong> presumed precursor lesi<strong>on</strong>s(ie, c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al adenoma-<strong>carcinoma</strong> sequence versus <strong>the</strong><strong>serrated</strong> <strong>pathway</strong>). A comm<strong>on</strong>ly utilized subdivisi<strong>on</strong> in<strong>to</strong>microsatellite stable (MSS) <strong>carcinoma</strong>s (which represent bothsuppressor <strong>pathway</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong>s arising ei<strong>the</strong>r sporadically or0046-8177/$ – see fr<strong>on</strong>t matter © 2010 Published by Elsevier Inc.doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2010.06.002

6 D. C. SnoverFig. 4 Microvesicular hyperplastic polyp. Note that <strong>the</strong> crypts arerelatively straight with narrow bases (40). Also, see Fig. 3A.are found almost exclusively in <strong>the</strong> left col<strong>on</strong> andcomm<strong>on</strong>ly dem<strong>on</strong>strate Kras mutati<strong>on</strong>s, whereas MVHP,which is still predominantly left-sided but with more rightsidedlesi<strong>on</strong>s than GCHP, tends <strong>to</strong> be BRAF mutated [4].MPHP appears <strong>to</strong> represent a damaged MVHP with reactivechange, but this category is rare and has not been wellstudied. It has been suggested that MVHP may act as aprecursor <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> more advanced and clearly premalignantSSA/P, in large part because <strong>the</strong>y share <strong>the</strong> BRAF mutati<strong>on</strong>and a propensity <strong>to</strong> methylati<strong>on</strong>, although this has not beenproven and perhaps is of more <strong>the</strong>oretical than practicalsignificance. Very rarely will <strong>on</strong>e encounter a MVHP thatdem<strong>on</strong>strates cy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasia resembling c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>aladenoma, and hence, it is possible that MVHP mayoccasi<strong>on</strong>ally become methylated at a gene critical forcarcinogenesis, as occurs in SSA/P, and hence may progress<strong>to</strong> malignancy without an intervening SSA/P.Perhaps <strong>the</strong> most persistent and perplexing issueregarding <strong>serrated</strong> lesi<strong>on</strong>s is <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong>re remains noc<strong>on</strong>sensus <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> best terminology for <strong>the</strong> lesi<strong>on</strong> knownvariably in <strong>the</strong> literature as sessile <strong>serrated</strong> adenoma (SSA),sessile <strong>serrated</strong> polyp (SSP), or <strong>serrated</strong> polyp with abnormalproliferati<strong>on</strong> . The term SSA was <strong>the</strong> first term used for thislesi<strong>on</strong>, and a majority of <strong>the</strong> current literature is written using<strong>the</strong> term SSA; however, <strong>the</strong>re is a sec<strong>on</strong>d large group whoprefers SSP. The term <strong>serrated</strong> polyp with abnormalproliferati<strong>on</strong> is rapidly losing favor. The rati<strong>on</strong>ale for <strong>the</strong>use of “polyp” ra<strong>the</strong>r than “adenoma” for this lesi<strong>on</strong> revolvesaround a c<strong>on</strong>cern that use of “adenoma” will cause c<strong>on</strong>fusi<strong>on</strong>with c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al adenomas arising via <strong>the</strong> APC mutati<strong>on</strong><strong>pathway</strong>, despite <strong>the</strong> fact that most authors in <strong>the</strong> field acceptthat <strong>the</strong>se lesi<strong>on</strong>s are functi<strong>on</strong>ally premalignant and hence“neoplastic.” In <strong>the</strong> practice of this author, who has used <strong>the</strong>term SSA since 1996, c<strong>on</strong>fusi<strong>on</strong> with c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al adenomashas not been an issue with our gastroenterologists, who seem<strong>to</strong> have no difficulty understanding <strong>the</strong> difference betweenSSA, tubular adenoma, tubulovillous adenoma, and villousadenoma <strong>on</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>y are familiar with <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>cept. Manyauthors believe that SSA is <strong>the</strong> best term because it reflects<strong>the</strong> premalignant potential of this lesi<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> <strong>serrated</strong><strong>pathway</strong> and is likely <strong>to</strong> lead <strong>to</strong> more appropriatemanagement that o<strong>the</strong>r more n<strong>on</strong>committal terms. N<strong>on</strong>e<strong>the</strong>less,c<strong>on</strong>sensus has not been reached, and <strong>the</strong> upcomingfourth editi<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> WHO classificati<strong>on</strong> of tumors of <strong>the</strong>digestive trace will reflect that at <strong>the</strong> current time ei<strong>the</strong>r termis acceptable as l<strong>on</strong>g as it is recognized that SSA and SSP arereferring <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> same lesi<strong>on</strong> [11]. For clarity sake, SSA/P willbe used throughout this article. Unfortunately, <strong>the</strong>re are stillsome pathologists who c<strong>on</strong>tinue <strong>to</strong> use <strong>the</strong> term hyperplasticpolyp or variant hyperplastic polyp for <strong>the</strong>se lesi<strong>on</strong>s, a mostunfortunate fact given <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>siderable management differencesbetween HP and SSA/Ps. The use of <strong>the</strong> “hyperplasticpolyp” for <strong>the</strong>se lesi<strong>on</strong>s should be avoided.SSA/P is characterized mechanistically by movement of<strong>the</strong> proliferative z<strong>on</strong>e away from its usual locati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> baseof <strong>the</strong> crypts, resulting in maturati<strong>on</strong>, which may develop<strong>to</strong>ward <strong>the</strong> base of <strong>the</strong> crypts leading <strong>to</strong> dis<strong>to</strong>rti<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> cryptarchitecture, comm<strong>on</strong>ly with dilated, L, inverted T, or anchorshapedcrypts with mature cells where <strong>the</strong> proliferative z<strong>on</strong>enormally is located (as evidenced by mucinous differentiati<strong>on</strong>as well as marking for cy<strong>to</strong>keratin 20 (Figs. 3B and 5) [10]).The crypts still retain <strong>the</strong>ir “attachment” or orientati<strong>on</strong> <strong>to</strong>ward<strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscularis mucosae, however, and are arrangedperpendicular <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscularis mucosae. SSA/P in itsearliest stage does not manifest dysplasia resemblingc<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al adenoma, although with progressi<strong>on</strong> <strong>to</strong>ward<strong>carcinoma</strong>s, such dysplasia develops.There has been variati<strong>on</strong> regarding <strong>the</strong> best term forlesi<strong>on</strong>s that combine <strong>the</strong> features of SSA/P with areas offrank cy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasia that resemble c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>aladenomas (Fig. 6). These lesi<strong>on</strong>s have in most of <strong>the</strong> olderFig. 5 SSA/P without cy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasia. Compared <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>HP, <strong>the</strong> overall architecture is dis<strong>to</strong>rted with variably shaped cryptsand mature cells at <strong>the</strong> base of <strong>the</strong> crypts (40). Also, see Fig. 3B.

Serrated <strong>pathway</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong>Fig. 6 SSA/P with cy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasia. This lesi<strong>on</strong> hascharacteristics of an SSA/P <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> right, but <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> left, <strong>the</strong>epi<strong>the</strong>lium is cy<strong>to</strong>logically dysplastic dem<strong>on</strong>strating hyperchromaticel<strong>on</strong>gated nuclei with pseudostratificati<strong>on</strong>. This may indicatec<strong>on</strong>versi<strong>on</strong> <strong>to</strong> a MSI state. There is an underlying invasiveadeno<strong>carcinoma</strong> as well (40).literature been called mixed HP-TA, and with <strong>the</strong> recogniti<strong>on</strong>of SSA/P, it turned out that <strong>the</strong> <strong>serrated</strong> porti<strong>on</strong> of most of<strong>the</strong>se mixed lesi<strong>on</strong>s was in reality SSA/P, leading <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> useof <strong>the</strong> term mixed SSA/P-TA for <strong>the</strong>se lesi<strong>on</strong>s [7]. However,it is currently felt that this term is misleading because <strong>the</strong>cy<strong>to</strong>logically dysplastic part of <strong>the</strong>se polyps is not ac<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al TA from a molecular perspective and probablyhas a more aggressive course than c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al TA. Asnoted above, c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al TA is a lesi<strong>on</strong> that starts with anAPC mutati<strong>on</strong>, acquires additi<strong>on</strong> mutati<strong>on</strong>s over time, andeventually, in a small number of cases and generally over <strong>the</strong>course of 10 years or more, becomes malignant. SSA/P withcy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasia, <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, in some cases (ie, in<strong>the</strong> case of lesi<strong>on</strong>s developing in<strong>to</strong> MSI <strong>carcinoma</strong>s)represents <strong>the</strong> development of microsatellite instability in<strong>the</strong> lesi<strong>on</strong> and hence is creating a lesi<strong>on</strong> with a propensity <strong>to</strong>develop in<strong>to</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong> with high frequency and rapidity (seeFig. 2 and discussi<strong>on</strong> above). These lesi<strong>on</strong>s are not APCmutated and probably require c<strong>on</strong>siderably more aggressivefollow-up than c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al adenomas. Hence, “SSA/P withcy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasia” is <strong>the</strong> preferred term for this lesi<strong>on</strong>,and <strong>the</strong> term mixed SSA/P-TA or HP-TA is no l<strong>on</strong>gerc<strong>on</strong>sidered acceptable.The o<strong>the</strong>r term that has had some c<strong>on</strong>troversy is that of <strong>the</strong>“traditi<strong>on</strong>al” <strong>serrated</strong> adenoma (TSA). This lesi<strong>on</strong> is <strong>on</strong>e ofseveral forms of <strong>serrated</strong> lesi<strong>on</strong>s that fit <strong>the</strong> definiti<strong>on</strong> of“<strong>serrated</strong> adenoma” proposed in <strong>the</strong> seminal article byL<strong>on</strong>gacre and Fenoglio-Prieser in 1990 [12]. The definiti<strong>on</strong>provided initially for “<strong>serrated</strong> adenoma” was that a “<strong>serrated</strong>adenoma” was a lesi<strong>on</strong> with dysplasia (and hence “adenoma”by c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al criteria in use at <strong>the</strong> time) but which showedan overall <strong>serrated</strong> c<strong>on</strong>figurati<strong>on</strong>. Unfortunately, this definiti<strong>on</strong>is overly broad and can be used <strong>to</strong> describe what are nowknown <strong>to</strong> be 3 or possibly 4 different lesi<strong>on</strong>s (SSA/P, SSA/Pwith cy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasia, TSA, and c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al APCadenomas with a <strong>serrated</strong> growth pattern). Recognizing this,in 2003, it was suggested that <strong>the</strong> most unique of this group,and <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>e member of this group which did not have a bettername, should be recognized as a separate entity, and <strong>the</strong> termtraditi<strong>on</strong>al <strong>serrated</strong> adenoma was recommended (because itwas thought that this lesi<strong>on</strong> was <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>e member of thisgroup that was most easily recognized by most pathologists,and <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>e that at <strong>the</strong> time was probably most comm<strong>on</strong>lybeing called “<strong>serrated</strong> adenoma,” in large part because at <strong>the</strong>time SSA/P was still being called HP by most pathologists,and SSA/P with cy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasia was being calledmixed HP-TA.) [3]. It is of some interest al<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se linesthat a recent reproducibility study identified this lesi<strong>on</strong> as <strong>the</strong><strong>on</strong>e with <strong>the</strong> best kappa statistic of <strong>the</strong> various <strong>serrated</strong>lesi<strong>on</strong>s, supporting our c<strong>on</strong>tenti<strong>on</strong> that most pathologistsalready know how <strong>to</strong> recognize this lesi<strong>on</strong> [13].There does c<strong>on</strong>tinue <strong>to</strong> be some variati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> diagnosisof TSA, however, in large part because of recent suggesti<strong>on</strong>sfor expansi<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> diagnostic criteria [10]. The originaldefiniti<strong>on</strong> of TSA was a very simplistic <strong>on</strong>e, with <strong>the</strong> mostnotable feature being <strong>the</strong> presence of a peculiar type ofatypical cell characterized by relatively abundant eosinophiliccy<strong>to</strong>plasm resembling that of an <strong>on</strong>cocyte, wi<strong>the</strong>l<strong>on</strong>gated nuclei (typically not hyperchromatic) often locatedin <strong>the</strong> mid porti<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> cell and with little or nopseudostratificati<strong>on</strong> and with little proliferative activity asdetermined by mi<strong>to</strong>tic count or Ki67 immunoreactivity[3,7,10]. This cell was c<strong>on</strong>sidered by many as being“dysplastic” and <strong>the</strong>refore was often equated with <strong>the</strong>“dysplasia” of c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al adenomas. Given <strong>the</strong> lack ofproliferative activity (as well as <strong>the</strong> lack of APC mutati<strong>on</strong>s)in <strong>the</strong>se cells, <strong>the</strong>y are not likely <strong>to</strong> have <strong>the</strong> same neoplasticpotential as c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al dysplasia and are better c<strong>on</strong>sideredFig. 7 TSA. This lesi<strong>on</strong> is characterized by an overall somewhatvilliform c<strong>on</strong>figurati<strong>on</strong> with a very complex overall architecture(40). Also, see Fig. 3C.7

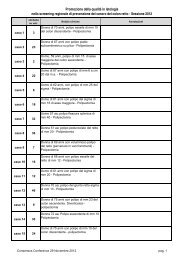

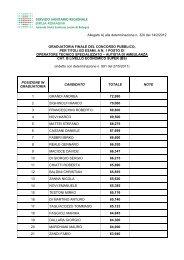

8 D. C. SnoverTable 2Proposal for a semimolecular classificati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>colorectal</strong> polypsTraditi<strong>on</strong>al terminology(pre-2003)Recently revised terminology(post-2003)Proposed semimolecular terminologyAdenoma C<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al adenoma APC-related neoplastic polypsTubular adenoma Tubular adenoma N<strong>on</strong><strong>serrated</strong> neoplastic polyp without villous comp<strong>on</strong>entTubulovillous adenoma Tubulovillous adenomas N<strong>on</strong><strong>serrated</strong> neoplastic polyp with villous comp<strong>on</strong>entVillous adenoma Villous adenomaSerrated adenomaHyperplastic polyp Serrated adenomas CIMP-adenomas, BRAF typeHyperplastic polyp SSA/P without cy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasia Sessile <strong>serrated</strong> neoplastic polyp without cy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasiaSSA/P with cy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasia Sessile <strong>serrated</strong> neoplastic polyp with cy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasiaCIMP-adenomas, KRAS typeTSA without c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al dysplasia Filiform <strong>serrated</strong> neoplastic polyp without c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al dysplasiaTSA with c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al dysplasia Filiform <strong>serrated</strong> neoplastic polyp with c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al dysplasiaHyperplastic polypsHyperplastic polyp, BRAF typeMicrovesicular HPMicrovesicular HPHyperplastic polyp, Kras typeGCHPGCHPHyperplastic polyp, o<strong>the</strong>rMucin poor HPMucin poor HPa metaplastic or possibly senescent cell. Although this celltype was original c<strong>on</strong>sidered a sine qua n<strong>on</strong> for <strong>the</strong> diagnosisof TSA, it is now apparent that this cell type can be seen in avariety of circumstances including in small areas ofo<strong>the</strong>rwise typical SSA/P, in some c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al adenomas(APC-related) and sometimes even in reactive mucosa. Animmunohis<strong>to</strong>chemical analysis of proliferati<strong>on</strong> and maturati<strong>on</strong>in <strong>serrated</strong> lesi<strong>on</strong>s has pointed out that a more likelydiagnostic abnormality in TSA is <strong>the</strong> presence of smallec<strong>to</strong>pic crypts created by apparent loss of anchoring of <strong>the</strong>Fig. 8 TSA with c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al dysplasia. This TSA hascy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasia similar <strong>to</strong> that seen in c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al adenomasin <strong>the</strong> right porti<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> pho<strong>to</strong>. In this particular case, <strong>the</strong> dysplasiais high grade with a cribriform pattern of growth. There wasinvasive <strong>carcinoma</strong> elsewhere in this polyp (40).crypt bases <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> muscularis mucosae [10] (Figs. 3C and 7).These ec<strong>to</strong>pic crypts dem<strong>on</strong>strated str<strong>on</strong>g CK20 staining in<strong>the</strong> luminal porti<strong>on</strong>s and Ki67 staining in <strong>the</strong> deeper aspects,hence recapitulating small crypts except that <strong>the</strong> base of <strong>the</strong>crypts was free floating in <strong>the</strong> lamina propria of villi ra<strong>the</strong>rthan sitting <strong>on</strong> (or being “anchored <strong>to</strong>”) <strong>the</strong> muscularismucosae. We now feel that <strong>the</strong>se ec<strong>to</strong>pic crypts are probably<strong>the</strong> best defining feature of TSA, although most TSAs willalso have <strong>the</strong> atypical eosinophilic cell noted above. Theseec<strong>to</strong>pic crypts are not present in all areas of all TSAs butshould be present at least focally. Often TSA will have largeareas with <strong>the</strong> metaplastic eosinophilic cells described above,but using <strong>the</strong>se diagnostic criteria, a TSA can also becomposed mainly of goblet cells. Whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>se different celltypes have any molecular or prognostic implicati<strong>on</strong>s is als<strong>on</strong>ot known. The lesi<strong>on</strong> described as “filiform” <strong>serrated</strong>adenoma is probably syn<strong>on</strong>ymous with TSA or represents asubset of TSA and may provide less c<strong>on</strong>fusing terminology(see Table 2) [14].Although eosinophilic metaplastic cells often make up ac<strong>on</strong>siderable porti<strong>on</strong> of TSAs, atypical cells with many of<strong>the</strong> morphological attributes of c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al dysplasia (ie,hyperchromasia, pseudostratificati<strong>on</strong> and increased proliferativeactivity) do occur in TSA, probably as part ofc<strong>on</strong>versi<strong>on</strong> <strong>to</strong>ward malignancy (Fig. 8). The molecularcharacteristics of <strong>the</strong>se cells (eg, mutati<strong>on</strong> and methylati<strong>on</strong>status) have not been well characterized, however, and <strong>the</strong>rehas been essentially no discussi<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> terminology of thisc<strong>on</strong>verted lesi<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> literature. Trying <strong>to</strong> be analogous <strong>to</strong>SSA/P, it would probably be appropriate <strong>to</strong> refer <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>selesi<strong>on</strong>s as “TSA with c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al cy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasia,”despite <strong>the</strong> fact that this is somewhat cumbersome. Thespecific mechanism of carcinogenesis in TSA is currentlynot well known and is discussed briefly above under

Serrated <strong>pathway</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong>“molecular mechanisms of <strong>carcinoma</strong>s development via <strong>the</strong><strong>serrated</strong> <strong>pathway</strong>.”5. The role of SSA/P in carcinogenesis and itseffect <strong>on</strong> management of <strong>the</strong>se lesi<strong>on</strong>sAs noted in <strong>the</strong> introducti<strong>on</strong>, it is now generallyrecognized that “col<strong>on</strong> cancer” comprises a family ofdiseases with various molecular <strong>pathway</strong>s. There is now noquesti<strong>on</strong> that SSA/P is <strong>the</strong> immediate precursor lesi<strong>on</strong> <strong>to</strong>sporadic CIMP+MSI <strong>carcinoma</strong>s. SSA/P is likely <strong>the</strong>precursor lesi<strong>on</strong> <strong>to</strong> CIMP+MSS <strong>carcinoma</strong>s as well.Combined, CIMP+MSI and CIMP+MSS <strong>carcinoma</strong>s accountfor approximately 35% of all <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong>;hence, <strong>the</strong>se are very important lesi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>to</strong> recognize anddeal with if <strong>on</strong>e wants <strong>to</strong> reduce <strong>the</strong> risk of col<strong>on</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong>through screening. Unfortunately, we are still somewhatimpaired in our understanding of <strong>the</strong> natural his<strong>to</strong>ry of<strong>serrated</strong> lesi<strong>on</strong>s because of a lack of l<strong>on</strong>gitudinal studies,and current recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for management are based inlarge part <strong>on</strong> our understanding of <strong>the</strong> molecular mechanismsof <strong>the</strong> <strong>pathway</strong> and <strong>on</strong> observati<strong>on</strong>al studies includingrecent data <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> frequency of <strong>serrated</strong> <strong>pathway</strong>–associated <strong>carcinoma</strong>s presenting as interval cancers inscreening programs.One important difference in screening for <strong>serrated</strong>lesi<strong>on</strong>s (as opposed <strong>to</strong> screening for c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al adenomas)results from <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong> CIMP+MSI <strong>pathway</strong>may be a rapidly progressive <strong>pathway</strong>, much more rapidthan carcinogenesis via <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al APC <strong>pathway</strong>, asdescribed above. Recent analysis of “interval <strong>carcinoma</strong>s”occurring in screening populati<strong>on</strong>s has indicated that <strong>the</strong>secancers are disproporti<strong>on</strong>ally MSI [15]. One possiblereas<strong>on</strong> for this is that some of <strong>the</strong>se lesi<strong>on</strong>s may becomemalignant very rapidly, with <strong>the</strong>ir entire lifespan fitting in<strong>the</strong> 5 or 10 years between screening examinati<strong>on</strong>s. Ano<strong>the</strong>rpotential reas<strong>on</strong> that should not be overlooked, however, isthat SSA/P is a very subtle lesi<strong>on</strong> and may be difficult <strong>to</strong>identify <strong>on</strong> endoscopic examinati<strong>on</strong>, especially for anendoscopist who is not experienced with recognizing <strong>the</strong>subtle changes that might indicate <strong>the</strong> presence of a lesi<strong>on</strong>(especially adherent s<strong>to</strong>ol or mucin that must be washed off<strong>to</strong> visualize <strong>the</strong> lesi<strong>on</strong>). Therefore, interval MSI cancersmight also occur because SSA/Ps are being missed. It turnsout that interval cancers are not <strong>on</strong>ly disproporti<strong>on</strong>allyCIMP+MSI, but <strong>the</strong>y are also disproporti<strong>on</strong>ally CIMP+MSS [16]. Because <strong>the</strong>re is no a priori reas<strong>on</strong> <strong>to</strong> suspectthat CIMP+MSS development has <strong>the</strong> same potential rapidprogressi<strong>on</strong> as seen with CIMP+MSI <strong>carcinoma</strong>, thisfinding would bolster <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory that some of <strong>the</strong> issuerelated <strong>to</strong> interval cancers involves failure <strong>to</strong> identify <strong>the</strong>underlying lesi<strong>on</strong>. Regardless of <strong>the</strong> reas<strong>on</strong>, this apparentenhancement of interval cancers with CIMP+ <strong>carcinoma</strong>sarising via <strong>the</strong> <strong>serrated</strong> <strong>pathway</strong> has significant implicati<strong>on</strong>s<strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> appropriate interval for rescreening patients with aknown SSA/P.Our past recommendati<strong>on</strong>s had suggested that <strong>the</strong> mostworrisome lesi<strong>on</strong>s of this group, and <strong>the</strong> lesi<strong>on</strong> with <strong>the</strong> mostpressing need for close surveillance, were <strong>the</strong> SSA/Ps withcy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasia, since <strong>the</strong>se lesi<strong>on</strong>s have <strong>the</strong> potential<strong>to</strong> rapidly progress <strong>to</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong> [7,8]. We still maintain thatany lesi<strong>on</strong> with this his<strong>to</strong>logy should be removed entirely bywhatever means necessary and that <strong>the</strong> patient undergorepeat endoscopy no l<strong>on</strong>ger than a year after initial excisi<strong>on</strong>(if <strong>the</strong> endoscopist is comfortable that <strong>the</strong> lesi<strong>on</strong> has beenentirely removed) or so<strong>on</strong>er if <strong>the</strong>re is any questi<strong>on</strong> aboutadequacy of excisi<strong>on</strong>. TSAs, ei<strong>the</strong>r with or without changesof c<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al dysplasia, are probably best treated asc<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong>al adenomas because <strong>the</strong>y do not lead <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong>development of MSI <strong>carcinoma</strong>s, and hence, <strong>the</strong>re is noreas<strong>on</strong> <strong>to</strong> suspect that <strong>the</strong>y might be more aggressive thano<strong>the</strong>r lesi<strong>on</strong>s. In additi<strong>on</strong>, because <strong>the</strong>y tend <strong>to</strong> occur in <strong>the</strong>rec<strong>to</strong>sigmoid regi<strong>on</strong> and are usually well-circumscribedprotruding lesi<strong>on</strong>s, surveillance and removal tend <strong>to</strong> beeasier. The real management issue is for SSA/P withoutcy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasia because <strong>the</strong>se are <strong>the</strong> most comm<strong>on</strong>lesi<strong>on</strong>s and are <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>es that are most difficult <strong>to</strong> visualizeand remove.Our original recommendati<strong>on</strong>s were relatively leisurelyregarding this group, with recommendati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>to</strong> remove <strong>the</strong>lesi<strong>on</strong> if possible or, if <strong>the</strong> lesi<strong>on</strong> was not easily resected via<strong>the</strong> endoscopy, <strong>to</strong> do surveillance at annual intervals <strong>to</strong>liberally biopsy <strong>the</strong> lesi<strong>on</strong> and look for cy<strong>to</strong>logical dysplasiathat would <strong>the</strong>n accelerate <strong>the</strong> need <strong>to</strong> remove <strong>the</strong> lesi<strong>on</strong>[7,8]. If <strong>the</strong> lesi<strong>on</strong> was completely removed, <strong>the</strong>n wesuggested reversi<strong>on</strong> <strong>to</strong> “standard” adenoma surveillanceintervals. Given <strong>the</strong> recent data regarding CIMP+ andinterval cancers, however, this may not be an adequatestrategy. Pers<strong>on</strong>al observati<strong>on</strong>s by myself and o<strong>the</strong>rs(Kenneth Batts, MD, pers<strong>on</strong>al communicati<strong>on</strong>s) wouldindicate that often patients with <strong>on</strong>e SSA/P will harboro<strong>the</strong>rs, ei<strong>the</strong>r synchr<strong>on</strong>ously or metachr<strong>on</strong>ously. This seemsespecially true for large lesi<strong>on</strong>s found in <strong>the</strong> right col<strong>on</strong>.When <strong>the</strong> criteria for “<strong>serrated</strong> polyposis” (formerly knownas “hyperplastic polyposis”) are met ([1] at least 5 <strong>serrated</strong>polyps proximal <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> sigmoid col<strong>on</strong> with 2 or more of<strong>the</strong>m larger than 10 mm, [2] any number of <strong>serrated</strong> polypsproximal <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> sigmoid col<strong>on</strong> in an individual who has afirst-degree relative with <strong>serrated</strong> polyposis, or [3] morethan 20 <strong>serrated</strong> polyps of any size, but distributedthroughout <strong>the</strong> col<strong>on</strong> ), <strong>the</strong> situati<strong>on</strong> is more defined, andclose surveillance with possible colec<strong>to</strong>my is c<strong>on</strong>sidered[11]. However, <strong>the</strong> criteria for <strong>serrated</strong> polyposis are at thispoint still entirely arbitrary, and <strong>the</strong>refore, it is possible ifnot probable that <strong>the</strong> finding of multiple SSA/Ps of any sizeor locati<strong>on</strong> may be adequate <strong>to</strong> recommend more frequentsurveillance. As noted above, <strong>the</strong> issue with SSA/P may be2-fold—potential rapid progressi<strong>on</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong> andincomplete removal. To prevent interval cancers, <strong>the</strong>refore,shortened interval surveillance may be appropriate.9

10 D. C. SnoverReas<strong>on</strong>able risk fac<strong>to</strong>rs suggesting <strong>the</strong> need for shortinterval reendoscopy would include size of lesi<strong>on</strong>s (lesi<strong>on</strong>ssmaller than 1 cm may not be as important), locati<strong>on</strong> oflesi<strong>on</strong>s (right sided lesi<strong>on</strong>s may be more important), and age(older patients being more pr<strong>on</strong>e <strong>to</strong> SSA/P as well as <strong>to</strong>sporadic MSI <strong>carcinoma</strong>s), in additi<strong>on</strong> <strong>to</strong> number of lesi<strong>on</strong>s.A reas<strong>on</strong>able strategy, and <strong>on</strong>e we are currently recommending,would be <strong>to</strong> repeat surveillance at 1 year forany<strong>on</strong>e with 2 or more completely removed SSA/Ps greaterthan 1 cm and determine future screening based <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong>sefindings. If <strong>the</strong>re is any significant risk that a lesi<strong>on</strong> was notcompletely removed, repeat endoscopy at a shorter intervalmay well be indicated. If additi<strong>on</strong>al SSA/Ps are identified at1 year, annual surveillance (at least until <strong>the</strong>re is a negativecol<strong>on</strong>oscopy) would seem reas<strong>on</strong>able. If screening at 1 yearis clear of lesi<strong>on</strong>s, <strong>the</strong>n extensi<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> interval <strong>to</strong> 2 <strong>to</strong> 3years would seem appropriate.6. Proposed soluti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>to</strong> <strong>on</strong>going issuesAs noted above, perhaps <strong>the</strong> more important issuesregarding <strong>serrated</strong> lesi<strong>on</strong>s involve appropriate management,although terminology remains an issue as well. Themanagement issue is amenable <strong>to</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r clinicopathologicalstudies focusing <strong>on</strong> natural his<strong>to</strong>ry, not <strong>on</strong>ly for <strong>the</strong> morecomm<strong>on</strong> SSA/P but also for TSA, since we know <strong>the</strong> leastabout that lesi<strong>on</strong>. Additi<strong>on</strong>al molecular characterizati<strong>on</strong> ofspecific genetic changes resulting in CIMP+MSS <strong>carcinoma</strong>sand for <strong>carcinoma</strong>s arising in TSA will also be valuablein this regard, since this informati<strong>on</strong> may help determine <strong>the</strong>best surveillance and preventi<strong>on</strong> strategies.Regarding <strong>the</strong> terminology issues, at <strong>the</strong> current time, <strong>the</strong>reappears <strong>to</strong> be a stalemate between <strong>the</strong> prop<strong>on</strong>ents of SSA andthose for SSP. Much of this problem exists because of <strong>the</strong>traditi<strong>on</strong>al use of <strong>the</strong> term adenoma not as a generic family oflesi<strong>on</strong>s (ie, polyps with premalignant potential) but ra<strong>the</strong>r for aspecific subset of adenomas, that is, adenomas predominantlyarising al<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong> suppressor <strong>pathway</strong> initiated with APCmutati<strong>on</strong>s. Perhaps it is time for gastrointestinal pathologists <strong>to</strong>c<strong>on</strong>sider reclassificati<strong>on</strong> of adenomas <strong>on</strong> a semimolecularbasis, realizing that it is not practical <strong>to</strong> perform moleculartesting <strong>on</strong> all lesi<strong>on</strong>s removed as adenomas. We could,however, alter our terminology <strong>to</strong> indicate <strong>the</strong> likely molecularaspects of adenomas, something that would point out <strong>the</strong>potential molecular difference and would at a minimum havean educati<strong>on</strong>al effect if not a direct management effect. It mightalso be advisable <strong>to</strong> eliminate <strong>the</strong> term adenoma fromterminology given <strong>the</strong> l<strong>on</strong>g his<strong>to</strong>ry of using this word <strong>on</strong>lyfor precursor lesi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>to</strong> n<strong>on</strong>-CIMP <strong>carcinoma</strong>s (ie, APCrelated<strong>carcinoma</strong>s arising via <strong>the</strong> suppressor <strong>pathway</strong> and MSI<strong>carcinoma</strong>s arising via MMR mutati<strong>on</strong>s in Lynch syndrome);however, finding a c<strong>on</strong>venient shorthand substitute will bedifficult. N<strong>on</strong>e<strong>the</strong>less, as a starting point, a suggesti<strong>on</strong> for asemimolecular classificati<strong>on</strong> is proposed in Table 2.References[1] Fear<strong>on</strong> ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for <strong>colorectal</strong> tumorigenesis.Cell 1990;61:759-67.[2] Jass JR. Classificati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>colorectal</strong> cancer based <strong>on</strong> correlati<strong>on</strong> ofclinical, morphological and molecular features. His<strong>to</strong>pathology2007;50:113-30.[3] Torlakovic E, Skovland E, Snover DC, et al. Morphologicreappraisal of <strong>serrated</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> polyps. Am J Surg Pathol2003;27:65-81.[4] O'Brien MJ, Yang S, Mack C, et al. Comparis<strong>on</strong> of microsatelliteinstability, CpG island methylati<strong>on</strong> phenotype, BRAF and KRASstatus in <strong>serrated</strong> polyps and traditi<strong>on</strong>al adenomas indicates separate<strong>pathway</strong>s <strong>to</strong> distinct <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>carcinoma</strong> end points. Am J Surg Pathol2006;30:1491-501.[5] Yachida S, Mudali S, Martin SA, M<strong>on</strong>tgomery EA, Iacobuzio-D<strong>on</strong>ahueCA. Beta-catenin nuclear labeling is a comm<strong>on</strong> feature of sessile<strong>serrated</strong> adenomas and correlates with early neoplastic progressi<strong>on</strong> afterBRAF activati<strong>on</strong>. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1823-32.[6] Boparai KS, Dekker E, Van Eeden S, et al. Hyperplastic polyps andsessile <strong>serrated</strong> adenomas as a phenotypic expressi<strong>on</strong> of MYHassociatedpolyposis. Gastroenterology 2008;135:2014-8.[7] Snover DC, Jass JR, Fenoglio-Preiser C, Batts KP. Serrated polyps of<strong>the</strong> large intestine: a morphologic and molecular review of an evolvingc<strong>on</strong>cept. Am J Clin Pathol 2005;124:380-91.[8] Snover DC. Serrated polyps of <strong>the</strong> large intestine. Sem Diag Pathol2005;22:301-8.[9] East JE, Saunders BP, Jass JR. Sporadic and syndromic hyperplasticpolyps and <strong>serrated</strong> adenomas of <strong>the</strong> col<strong>on</strong>: classificati<strong>on</strong>, moleculargenetics, natural his<strong>to</strong>ry, and clinical management. Gastroenterol ClinNorth Am 2008;37:25-46.[10] Torlakovic EE, Gomez JD, Driman DK, et al. Sessile <strong>serrated</strong> adenoma(SSA) vs. traditi<strong>on</strong>al <strong>serrated</strong> adenoma (TSA). Am J Surg Pathol2008;32:21-9.[11] Snover DC, Ahnen DJ, Burt RW, Odze RD. Serrated polyps of <strong>the</strong>col<strong>on</strong> and rectum and <strong>serrated</strong> (“hyperplastic”) polyposis. In: BozmanFT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise N, edi<strong>to</strong>rs. WHO classificati<strong>on</strong> oftumours. Pathology and genetics. Tumours of <strong>the</strong> digestive system.Berlin: Springer-Verlag (4th ed. [in press]).[12] L<strong>on</strong>gacre TA, Fenoglio-Preiser CF. Mixed hyperplastic adenoma<strong>to</strong>uspolyps/<strong>serrated</strong> adenomas. A distinct form of <strong>colorectal</strong> neoplasia. AmJ Surg Pathol 1990;14:524-37.[13] Farris AB, Misdraji J, Srivastava A, et al. Sessile <strong>serrated</strong> adenoma:challenging discriminati<strong>on</strong> from o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>serrated</strong> col<strong>on</strong>ic polyps. Am JSurg Pathol 2008;32:30-5.[14] Yantiss RK, Oh KY, Chen YT, et al. Filiform <strong>serrated</strong> adenomas: aclinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 18 cases. Am JSurg Pathol 2007;31:1238-45.[15] Sawhney MS, Farrar WD, Gudiseva S, et al. Microsatellite instabilityin interval col<strong>on</strong> cancers. Gastroenterology 2006;131:1700-5.[16] Arain MA, Sawhney M, Sheikh S, et al. CIMP status of interval col<strong>on</strong>cancers: ano<strong>the</strong>r piece <strong>to</strong> <strong>the</strong> puzzle. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:1189-95.