Relationship between decile score of secondary school, the

Relationship between decile score of secondary school, the

Relationship between decile score of secondary school, the

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

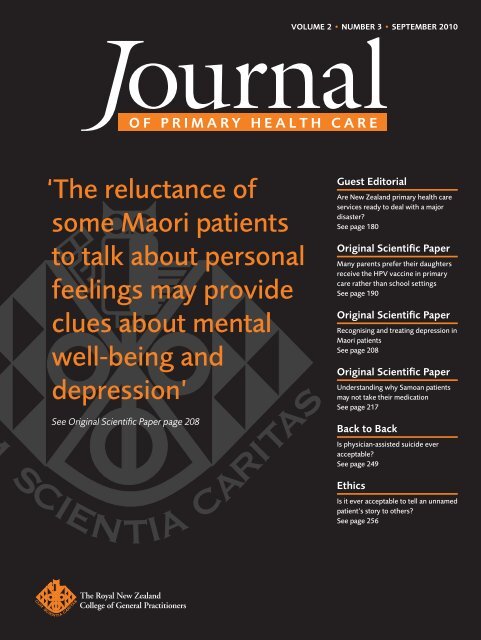

VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE‘The reluctance <strong>of</strong>some Maori patientsto talk about personalfeelings may provideclues about mentalwell-being anddepression’See Original Scientific Paper page 208Guest EditorialAre New Zealand primary health careservices ready to deal with a majordisaster?See page 180Original Scientific PaperMany parents prefer <strong>the</strong>ir daughtersreceive <strong>the</strong> HPV vaccine in primarycare ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>school</strong> settingsSee page 190Original Scientific PaperRecognising and treating depression inMaori patientsSee page 208Original Scientific PaperUnderstanding why Samoan patientsmay not take <strong>the</strong>ir medicationSee page 217Back to BackIs physician-assisted suicide everacceptable?See page 249EthicsIs it ever acceptable to tell an unnamedpatient’s story to o<strong>the</strong>rs?See page 256

EDITORIALsfrom <strong>the</strong> editorJPHC achieves MEDLINE statusFelicity Goodyear-Smith MBChB, MGP,FRNZCGP, EditorCorrespondence to:Felicity Goodyear-SmithPr<strong>of</strong>essor and GoodfellowPostgraduate Chair,Department <strong>of</strong> GeneralPractice and PrimaryHealth Care, TheUniversity <strong>of</strong> Auckland,PB 92019 Auckland,New Zealandf.goodyear-smith@auckland.ac.nzWe are delighted to announce that<strong>the</strong> Journal <strong>of</strong> Primary Health Care(JPHC) has been selected by <strong>the</strong> UnitedStates National Library <strong>of</strong> Medicine (NLM)for inclusion in Index Medicus and MEDLINE.The primary consideration in selecting journalsfor indexing is <strong>the</strong> scientific merit <strong>of</strong> a journal’scontent. The validity, importance, originality,and contribution to <strong>the</strong> coverage <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> field <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> overall contents are key factors considered by<strong>the</strong> NLM’s selection panel in recommending ajournal for indexing.If a journal is published three or more times ayear, four issues are needed to apply for indexing.The application to NLM was made in January2010 based on <strong>the</strong> first four issues (2009, volume1, issues 1 to 4). MEDLINE indexing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> JPHChas <strong>the</strong>refore been achieved in <strong>the</strong> shortest possibletime. Throughout its 35 years <strong>of</strong> publication(1974 to 2008), <strong>the</strong> New Zealand Family Physicianwas unsuccessful in its bids to be indexed inMEDLINE. 1 One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> drivers for launching <strong>the</strong>JPHC was to create a flagship publication for <strong>the</strong>RNZCGP that would be internationally recognisedas a quality journal and obtain MEDLINEstatus.While <strong>the</strong> editor plays a substantial role, producinga journal is a team effort. This milestoneis a formal recognition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> contributionsmade by <strong>the</strong> many people who help create <strong>the</strong>journal—<strong>the</strong> authors who submit <strong>the</strong>ir work,peer reviewers who critique it, members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>editorial board who provide advice and guidance,<strong>the</strong> College staff who work to produce a firstrateprint and online journal and <strong>the</strong> readerswho provide thoughtful feedback. Many thanksto all who have played a part towards us reachingthis goal.MEDLINE is a bibliographic database containingover 18 million references to journal articles inlife sciences and biomedicine from about 5000 selectedjournals. Articles published in MEDLINEindexedjournals can be found using PubMed.Research published in non-MEDLINE journalshas little chance <strong>of</strong> being accessed and quoted byo<strong>the</strong>rs, hence it is <strong>of</strong> great value for journals tobe indexed in MEDLINE. Indexing will enablereaders to search and retrieve all JPHC articlesincluding our back issues.In 2009, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Chris van Weel, past President<strong>of</strong> Wonca, was instrumental in <strong>the</strong> NLM introducinga new Subject Heading ‘Primary HealthCare’ (including Family Medicine) in IndexMedicus and reallocating <strong>the</strong> journals that focuson primary health care, family medicine andgeneral practice to this subject. 2 This means that<strong>the</strong> JPHC will be categorised alongside leadinggeneral practice journals such as Annals <strong>of</strong> FamilyMedicine, Family Practice and <strong>the</strong> British Journal<strong>of</strong> General Practice.Some <strong>of</strong> our readers still wish for a publicationby GPs for GPs, as attested in our Lettersto <strong>the</strong> Editor, while o<strong>the</strong>rs applaud <strong>the</strong> interdisciplinaryapproach adopted by <strong>the</strong> JPHC. Thisissue certainly continues with our cross-specialtyapproach. Authors include GPs and o<strong>the</strong>r medicalpractitioners, nurses, psychologists, pharmacists,epidemiologists and o<strong>the</strong>r assorted researchersand academics and cover a broad spectrum <strong>of</strong>primary health care issues.Mitchell and colleagues explore whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>secondary</strong><strong>school</strong> <strong>decile</strong> rating and size <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir town<strong>of</strong> origin has any impact on medical students’subsequent career choices such as rural generalpractice. 3 There are two studies from <strong>the</strong> team at178 VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010 J OURNAL OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

EDITORIALsguest editorialWhile it is unlikely that <strong>the</strong>re will be a war here,recent international seismic events have raisedour awareness that, in NZ, we too are highlylikely to experience natural disasters by virtue <strong>of</strong>our geographic location on major, active tectonicplate intersections, volcanic zones and <strong>the</strong> oceanicand climatic impacts which bring tsunami, majorfloods and landslips. Climatic conditions mayalso generate circumstances for transport-relateddisasters, including road transport and aircraftcrashes as well as maritime disasters. Although<strong>the</strong>re are Civil Defence plans for immediateemergency disaster intervention, few, if any,resources appear to have been made available fortrauma treatment over <strong>the</strong> longer term.Any major disaster is accompanied by traumafor those upon whom it impacts ei<strong>the</strong>r directlyor indirectly, making <strong>the</strong>m susceptible to posttraumaticreactions <strong>of</strong> varying levels <strong>of</strong> severity.Estimates suggest PTSD will affect up to 30% <strong>of</strong>iour and academic performance <strong>of</strong> children andadolescents. 1,7 The Georgian experience has beenthat PTSD also has economic and social impactson adults, with observed increases in alcoholand drug abuse, depression and family violence.These impacts affected adults’ ability to care forchildren and also those normally expected towork with <strong>the</strong>m, such as teachers and communityhealth providers. 8There is an extensive body <strong>of</strong> evidence supportingtrauma-focussed CBT as <strong>the</strong> most effectiveintervention for post-traumatic symptoms. 4,5,9,10There is also evidence that such CBT is also<strong>the</strong> intervention <strong>of</strong> choice when working withtraumatised children, 11 including those as youngas two years old. 12Given that only a small proportion <strong>of</strong> NZ’smental health pr<strong>of</strong>essionals is trained to providetrauma-focussed CBT interventions, it is likelyHealth pr<strong>of</strong>essionals resident in a disaster area may be able toprovide an initial response, but it has to be recognised that, in anymajor disaster, locals are <strong>the</strong>mselves frequently traumatised andthus less well able to deliver an effective servicedisaster victims. 1 Because <strong>of</strong> delayed reactions andfactors associated with disruption <strong>of</strong> normal life,displacement from home, exposure to death orinjury <strong>of</strong> family members, loss <strong>of</strong> employment oro<strong>the</strong>r family stressors, PTSD symptoms may continueto emerge over periods as long as six monthsto two years post-disaster. 1,2 Research indicatesthat those most susceptible to development <strong>of</strong>PTSD are children, women and <strong>the</strong> elderly, whichis not to suggest that males are immune as <strong>the</strong>military data on male PTSD indicate. 4,5Post-disaster studies <strong>of</strong> children exposed to <strong>the</strong>effects <strong>of</strong> earthquakes, floods, tornados and <strong>the</strong>9/11 terror attack show that <strong>the</strong>y are particularlysusceptible to PTSD. 2,3,6,7 These effects aredurable, especially if untreated, being evidentfor at least three years afterwards. The impacts<strong>of</strong> PTSD are found to affect both <strong>school</strong> behavthateven fewer primary health care pr<strong>of</strong>essionalswill have had such training. As a result,provision <strong>of</strong> an effective response to moderateto severe trauma effects will be unlikely unlesssome consideration is given to training a cadre<strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essionals who would <strong>the</strong>n be availableto respond to <strong>the</strong> traumatic aftermath <strong>of</strong> anymajor disaster. Health pr<strong>of</strong>essionals resident ina disaster area may be able to provide an initialresponse, but it has to be recognised that, in anymajor disaster, locals are <strong>the</strong>mselves frequentlytraumatised and thus less well able to deliver aneffective service.We identified a number <strong>of</strong> lessons for primaryhealth providers from <strong>the</strong> Russian–Georgianconflict and from <strong>the</strong> research literature thatcould be considered relevant to <strong>the</strong> NZ context inpreparing for a natural disaster.VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010 J OURNAL OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE 181

EDITORIALsguest editorialFirst, an initial emergency response, while helpful,is insufficient to provide significant benefitsfor persons suffering from moderate to severepost-traumatic effects, particularly as PTSD can,by definition, only be diagnosed at least fourweeks after exposure to <strong>the</strong> traumatic experience. 13Second, children and <strong>the</strong> elderly are <strong>the</strong> mostvulnerable to <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> post-traumaticsymptoms, females are more susceptible thanmales, and post-traumatic symptoms have amajor impact upon children’s academic performance,particularly concentration, memory, andclassroom demeanour and upon adults’ ability t<strong>of</strong>unction normally.Third, <strong>the</strong>re were cultural and gender differencesin symptom expression. In <strong>the</strong> cultural context,increases in somatic complaints (e.g. headaches,stomach pains) were noted, along with complaints<strong>of</strong> ‘illness’. Cultural beliefs around mental illnessmade somatic symptoms a more acceptable mode<strong>of</strong> expressing stress and trauma than reporting‘mental’ symptoms such as anxiety, phobias,panic reactions or re-experiencing. In terms <strong>of</strong>gender, boys tended to display post-traumaticproblems through increases in <strong>the</strong>ir aggressiveplay, disobedience and displays <strong>of</strong> anger, aggressionor anxiety (externalising), while girls tendedto become withdrawn, depressed or anxious andless able to focus on <strong>school</strong> work (internalising).Women <strong>of</strong>ten expressed concerns about <strong>the</strong> menand children ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong>ir own symptoms,and tried to avoid discussing <strong>the</strong> situation thatcaused <strong>the</strong> trauma. Men were more likely to denyany traumatic symptoms and to avoid treatment,while at <strong>the</strong> same time demonstrating increasesin drinking, smoking, anger and sleeplessness.Substance abuse and domestic violence increasedamongst displaced and unemployed males, affectingboth women and children in <strong>the</strong>ir familieswho already were living in very stressful circumstances.Males displaying trauma symptoms<strong>of</strong>ten denied trauma or avoided engaging withtreatment services. The emergency service andmilitary personnel exposed to <strong>the</strong> conflict werenot immune from trauma effects, but frequentlyfailed to seek assistance or be <strong>of</strong>fered it.Fourth, we found that, with our novice pr<strong>of</strong>essionals,key CBT trauma intervention skillscould be taught to a level <strong>of</strong> mastery relativelyeasily and in a short time (six weeks), whichmade effective intervention available for thosewho accepted treatment. Our trainee <strong>the</strong>rapistsfound that CBT produced rapid beneficial effectswith adults and children, even in cases <strong>of</strong> severePTSD symptoms and <strong>of</strong>ten after relatively briefexposure to treatment, so that symptoms such asavoidance, re-experiencing, insomnia and panicattacks became manageable, allowing normalfunctioning to be achieved.Our conclusion was that it would make sense totrain a cadre <strong>of</strong> primary health care personnelto deliver CBT for trauma so that NZ was wellprepared for <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> any major disaster onits own shores and better able to <strong>of</strong>fer assistanceto nearby Pacific countries experiencing naturaldisasters.References1. Kruczek T, Salsman J. Prevention and treatment <strong>of</strong> posttraumaticstress disorder in <strong>the</strong> <strong>school</strong> setting. Psychol Sch.2006;43(4):461–470.2. Bal A. Post-traumatic stress disorder in Turkish child and adolescentsurvivors three years after <strong>the</strong> Marmara earthquake.Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2008;13(3):134–139.3. Bokszcanin A. PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents28 months after a flood: age and gender differences. J TraumaStress. 2007;20(3):347–351.4. Briere J, Scott C. Principles <strong>of</strong> trauma <strong>the</strong>rapy: symptoms,evaluation and treatment. New York: Sage Publications; 2006.5. Taylor S. Clinician’s guide to PTSD: a cognitive-behavioralapproach. New York: Guilford Press; 2006.6. Evans LG, Oehler-Stinnett J. Structure and prevalence <strong>of</strong> PTSDsymtomology in children who have experienced a severetornado. Psychol Sch. 2006;43(3):283–295.7. Sahin NH, Batigun AD, Yilmaz B. Psychological symptoms <strong>of</strong>Turkish children and adolescents after <strong>the</strong> 1999 earthquake:exposure, gender, location and time duration. J Trauma Stress.2007;20(3):335–345.8. World Health Organization. Unpublished report by <strong>the</strong> GeorgianWHO Mental Health Cluster Survey <strong>of</strong> IDP communitiesin conflict zones and collection centres in Georgia; 2009.9. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, editors. Effective treatmentsfor PTSD. New York: Guilford Press; 2000.10. Zayfert C, Becker CB. Cognitive-behavioral <strong>the</strong>rapy forPTSD: a case formulation approach. New York: GuilfordPress; 2007.11. Cohen J A, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E. Treating trauma andtraumatic grief in children and adolescents. New York: GuilfordPress; 2006.12. Scheeringa MS, Salloum A, Arnberger RA, Weems CF,Amaya-Jackson L, Cohen JA. Feasibility and effectiveness <strong>of</strong>cognitive-behavioral <strong>the</strong>rapy for post traumatic stress disorderin pre<strong>school</strong> children: Two case reports. J Trauma Stress.2007;20(4):631–636.13. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and StatisticalManual. 4th Ed. (Text Revision) (DSM-IV-TR). WashingtonDC; 2000.182 VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010 J OURNAL OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPErSquantitative research<strong>Relationship</strong> <strong>between</strong> <strong>decile</strong> <strong>score</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>secondary</strong> <strong>school</strong>, <strong>the</strong> size <strong>of</strong> town <strong>of</strong> originand career intentions <strong>of</strong> New Zealandmedical studentsClinton J Mitchell MBChB, Med;¹ Boaz Shulruf PhD,² Phillippa J Poole BSc, MBChB¹ABSTRACTintroduction: New Zealand is facing a general practice workforce crisis, especially in rural communities.Medical <strong>school</strong> entrants from low <strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s or rural locations may be more likely to chooserural general practice as <strong>the</strong>ir career path.1Medical Education Division,The University <strong>of</strong> Auckland,Auckland, New Zealand2Centre for Medical andHealth Sciences Education,The University <strong>of</strong> AucklandAim: To determine whe<strong>the</strong>r a relationship exists <strong>between</strong> <strong>secondary</strong> <strong>school</strong> <strong>decile</strong> rating, <strong>the</strong> size <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>town <strong>of</strong> origin <strong>of</strong> medical students and <strong>the</strong>ir subsequent medical career intentions.Methods: University <strong>of</strong> Auckland medical students from 2006 to 2008 completed an entry questionnaireon a range <strong>of</strong> variables thought important in workforce determination. Analyses were performed ondata from <strong>the</strong> 346 students who had attended a high <strong>school</strong> in New Zealand.Results: There was a close relationship <strong>between</strong> size <strong>of</strong> town <strong>of</strong> origin and <strong>decile</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>secondary</strong> <strong>school</strong>.Most students expressed interests in a wide range <strong>of</strong> careers, with students from outside major citiesmaking slightly fewer choices on average.DISCUSSION: There is no strong signal from <strong>the</strong>se data that career speciality choices will be determinedby <strong>decile</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>secondary</strong> <strong>school</strong> or size <strong>of</strong> town <strong>of</strong> origin. An increase in <strong>the</strong> proportion <strong>of</strong> rural students inmedical programmes may increase <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> students from lower <strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s, without addingano<strong>the</strong>r affirmative action pathway.KEYWORDS: Education, medical; social class; career choiceBackgroundSome <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most important decisions in <strong>the</strong>shaping <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> future medical workforce relate to<strong>the</strong> selection <strong>of</strong> medical students. There is a socialobligation on universities to facilitate <strong>the</strong> development<strong>of</strong> a wide range <strong>of</strong> medical practitioners tomeet <strong>the</strong> health needs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population.It is likely that medical graduates from diversebackgrounds would address priority areas <strong>of</strong>need and result in <strong>the</strong> range <strong>of</strong> doctors needed. 1–3Diversification also allows equity <strong>of</strong> access forminority groups. For around 40 years, Maoriand Pacific medical student admission schemeshave been in place to redress <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> minorityrepresentation within <strong>the</strong> medical workforce.Around 16% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> current Auckland studentbody identifies as Maori or Pacific (Medical ProgrammeDirectorate, The University <strong>of</strong> Auckland,personal communication). Since 2004, TheUniversity <strong>of</strong> Auckland has <strong>of</strong>fered places to 20students <strong>of</strong> rural origin. Evidence suggests <strong>the</strong>sestudents will be more likely to return to practisein rural settings. 4,5 In recent years in <strong>the</strong> UnitedKingdom, a number <strong>of</strong> efforts have been made togive students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds<strong>the</strong> opportunity to become doctors. 6 Fewstudies have reported on <strong>the</strong> career pathways andchoices <strong>of</strong> individuals from low socioeconomiccommunities.J PRIMARY HEALTH CARE2010;2(3):183–189.CORRESPONDENCE TO:Phillippa PooleAssociate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor,Medical EducationDivision, School <strong>of</strong>Medicine, Faculty <strong>of</strong>Medical and HealthSciences, The University<strong>of</strong> Auckland, PB 92019Auckland 1142,New Zealandp.poole@auckland.ac.nzVOLUME 2 • NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010 J OURNAL OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE 183

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPERSquantitative researchcould classify practising doctors. Although anopen field was also included, in all instancesresponses could be attributed to one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 18options.The careers in which students indicated an interestin working were analysed by high <strong>school</strong><strong>decile</strong> and by size <strong>of</strong> town <strong>of</strong> origin. Odds ratios(OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated;instances where <strong>the</strong> OR value +/- 95% CIdid not cross 1.00 were deemed significant. O<strong>the</strong>rtechniques included logistic regression and crosstabulation.Statistical analyses were preparedusing SPSS for Windows Version 16.0.ResultsData were available from 397 medical studentsin <strong>the</strong> entry cohorts 2006 to 2008, which wasan 82% return rate. Of this cohort, 51 sets <strong>of</strong>data were excluded where <strong>the</strong> <strong>secondary</strong> <strong>school</strong>attended by <strong>the</strong> student was overseas or <strong>the</strong> NewZealand Correspondence School.There was a marked preponderance <strong>of</strong> studentsfrom <strong>decile</strong> 9 and 10 <strong>school</strong>s (see Figure 1). Itshould be noted that <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> year 13 studentsin each <strong>decile</strong> nationwide is not uniform;in fact <strong>decile</strong> 9 and 10 students make up 30%<strong>of</strong> year 13 students in New Zealand (Centre forMedical and Health Sciences Education, personalcommunication).The average <strong>decile</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>school</strong>s for studentsfrom a major city was 8.1 compared with 6.4 and6.3 for provincial centre and small town respectively.By far, <strong>the</strong> largest number <strong>of</strong> city-origin studentscame from Auckland; Hamilton, Wellington andChristchurch were also represented. Over <strong>the</strong>three-year period <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study, students camefrom 120 <strong>school</strong>s throughout New Zealand.Students made a mean <strong>of</strong> 9.75 expressions <strong>of</strong>interest from <strong>the</strong> possible 18 career choices. Ingeneral, students from lower <strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s and/or smaller towns made fewer choices (Tables 2and 3), although this exceeded <strong>the</strong> significancelevel <strong>of</strong> 0.05 only for town size when analysis <strong>of</strong>variance was used.WHAT GAP THIS FILLSWhat we already know: Students from impoverished backgrounds arerare in medical student classes. The current retention crisis in New Zealand isuntenable, especially in rural communities.What this study adds: Seventy-two percent <strong>of</strong> students indicated aninterest in general practice on entry to medical <strong>school</strong>. An increase in <strong>the</strong>number <strong>of</strong> medical students from lower socioeconomic and rural areas mayhave <strong>the</strong> benefit <strong>of</strong> an added number <strong>of</strong> students choosing to practise incertain specialties, including general practice.When <strong>the</strong> data <strong>of</strong> students from small towns andprovincial centres were combined, students frommajor cities made more choices (10.20 (SD 5.4)versus 8.15 (SD 5.9); p

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPErSquantitative researchNone<strong>the</strong>less, some differences were seen in <strong>the</strong>patterns <strong>of</strong> choice among students from differentbackgrounds.The major differences emerged in an analysiscomparing students who came from high <strong>decile</strong><strong>school</strong>s in major cities and those in <strong>the</strong> remaininggroups. Students from high <strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s weremore likely to signal an interest in most specialties(Figure 5) and <strong>the</strong>y were twice as likely aso<strong>the</strong>r students to signal an interest in medicineand surgery and respective subspecialties.DiscussionThere was a strong relationship <strong>between</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>decile</strong> <strong>of</strong> a <strong>secondary</strong> <strong>school</strong> and <strong>the</strong> size <strong>of</strong> townFigure 2. Location <strong>of</strong> origin <strong>of</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Auckland medical students by regions <strong>of</strong>New Zealand and size <strong>of</strong> town.<strong>of</strong> origin. The average <strong>decile</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>school</strong>s <strong>of</strong>‘major city’ students was two <strong>decile</strong> points higherthan <strong>the</strong>ir provincial/small town counterparts.These variables were associated with a relativelyminor effect on intended medical career choices.The majority <strong>of</strong> students came from <strong>the</strong> greaterAuckland region and <strong>the</strong> upper North Island.There was a very wide range <strong>of</strong> <strong>secondary</strong> <strong>school</strong><strong>of</strong> origin—this is in contrast to a common viewthat most students in <strong>the</strong> Auckland programmecome from a limited number <strong>of</strong> city <strong>school</strong>s inAuckland. We were encouraged to find over 11%came from areas with a population <strong>of</strong> 10 000 orless. To put <strong>the</strong>se findings in context, a studyfrom <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Otago found that 84.5%came from main urban areas, while only 2.9%came from rural areas. 11 This observation may bean indication that <strong>the</strong> rural entry programmesintroduced in 2004 are having <strong>the</strong> desired effecton diversification.With <strong>the</strong> limitation that <strong>the</strong> <strong>decile</strong> <strong>of</strong> a high<strong>school</strong> can at most be an approximation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>socio economic status <strong>of</strong> an individual student,it was encouraging that 45% <strong>of</strong> students in <strong>the</strong>study reported <strong>the</strong>y did not attend <strong>decile</strong> 9 or10 <strong>school</strong>s. Traditionally, medical students havecome largely from upper socio economic groups. 12Even though students aiming for medical <strong>school</strong>are, by and large, capable students, it is stilllikely that <strong>the</strong> academic and personal preparationneeded during final years <strong>of</strong> high <strong>school</strong> and<strong>the</strong> admissions process unduly favour studentsfrom higher <strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s. Both universities nowselect students after at least one year at universityfor a number <strong>of</strong> reasons, one <strong>of</strong> which is thatthis may allow capable students who seek entryto medicine to compete on relatively level terms,regardless <strong>of</strong> socio economic status and location <strong>of</strong>high <strong>school</strong>.Thompson and Subich have recently discernedthat social status was predictive <strong>of</strong> ‘career decisionself-efficacy’, 13 and extended upon previousfindings that <strong>the</strong> range and implementation <strong>of</strong>choices was also affected by social status. 13,14At <strong>the</strong> opposite end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> spectrum, studentsperceiving <strong>the</strong>mselves as having greater economicresources compared with <strong>the</strong>ir peers reportedmore certainty in, and comfort with, career186 VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010 J OURNAL OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPERSquantitative researchFigure 3. Odds ratio for students from low (left) or middle (right) <strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s choosing a particular specialty compared with those from high <strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s.Figure 4. Odds ratio for students from small towns (left) or provincial centres (right) choosing a particular specialty compared with those from major cities.VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010 J OURNAL OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE 187

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPErSquantitative researchFigure 5. Odds ratio (OR) for students from high <strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s in major cities choosing aparticular specialty compared with those from all o<strong>the</strong>r areas and <strong>decile</strong>s.choices. 13 A different effect was seen with thiscohort <strong>of</strong> students. We found that NZ domesticstudents entering medical <strong>school</strong> in Aucklandare enthusiastic about <strong>the</strong> range open to <strong>the</strong>m; onaverage, students rate an interest in nearly 10 <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> 18 options available to <strong>the</strong>m. Students fromlower <strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s, provincial centres and smalltowns made fewer choices. The implication <strong>of</strong>this finding is not yet clear and <strong>the</strong>re are severalpossible explanations. There may be a lack <strong>of</strong>awareness in <strong>the</strong>se groups <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> potential careerswithin medicines, or deliberate strategies used bystudents from larger towns/higher <strong>decile</strong>s to keepmany options open. An alternative hypo<strong>the</strong>sis isthat students from lower <strong>decile</strong>s or smaller townsmay be more definite about what <strong>the</strong>y do and donot want to do in medicine.Studies have shown that only a minority <strong>of</strong>students (45%) correctly identified <strong>the</strong>ir lateractual choice <strong>of</strong> specialty prior to <strong>the</strong>ir first day<strong>of</strong> lectures. 15 There were few strong and consistentpatterns in <strong>the</strong> intended careers <strong>of</strong> medicalstudents’ intention at entry due to <strong>the</strong> fact that<strong>the</strong>re were relatively small numbers <strong>of</strong> studentsin <strong>the</strong> survey and a wide range <strong>of</strong> choices available.However, we found that students from high<strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s in major cities were over twice aslikely to signal an interest in medicine and/orsurgery and <strong>the</strong>ir subspecialties. In five <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>18 specialties, including <strong>the</strong> clinical specialties<strong>of</strong> geriatrics, general practice and obstetrics andgynaecology, <strong>the</strong>re was no significant differencein preferences <strong>between</strong> any <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> student groupsin this study.A positive finding was that 250 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 346students (72%) indicated an interest in generalpractice, a priority specialty area in NZ. Areasin NZ with high chronic disease burdens areover-represented by low <strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s and underservedby GPs. In Counties-Manukau, 65.5%<strong>of</strong> <strong>school</strong>s are <strong>decile</strong> 4 or below; 16 <strong>the</strong>re are 280general practitioners for every 100 000 population,compared with 425 for <strong>the</strong> same populationin Auckland DHB. 17 Vaglum found that studentsinterested in a career in family medicine at entryto medical <strong>school</strong> were motivated by status/security,more so than for any o<strong>the</strong>r career. They postulatedthat students coming from a lower ‘socialorigin’ may be more aware <strong>of</strong> a change in statusand/or security that accompanies being a doctor. 18This present study, however, does not supportthis notion—students from all groups signalledan interest in general practice similarly.Time will allow <strong>the</strong> testing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>secondary</strong>hypo<strong>the</strong>ses generated from this study that studentsfrom smaller centres/lower <strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>sare more accurate in <strong>the</strong>ir predictions <strong>of</strong> careerchoices, and that students from high <strong>decile</strong> city<strong>school</strong>s are twice as likely to become NZ’s futurephysicians and surgeons.The students entering <strong>the</strong> programme now willnot be specialists until at least 2020. A strategy<strong>of</strong> seeking to ‘grow our own’ health pr<strong>of</strong>essionalsseems appropriate. Zayas opines that pr<strong>of</strong>essionalspractising in <strong>the</strong>ir home communities aremore cognisant <strong>of</strong>, and sensitive to, local needs. 19For us to achieve this will require overcoming<strong>the</strong> perception that students from lower socioeconomicgroups identify medical <strong>school</strong> as ‘culturallyalien and “posh”; few consider <strong>the</strong>y haveany chance <strong>of</strong> ever gaining a place’. 20 Selection188 VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010 J OURNAL OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPERSquantitative researchprocesses and pathways must continue to enhance<strong>the</strong> prospects <strong>of</strong> a medical career for studentsfrom outer metropolitan areas and beyond, andfrom lower <strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s.The announcement <strong>of</strong> an imminent increase inmedical student numbers provides both medical<strong>school</strong>s with <strong>the</strong> impetus to review and possiblyamend admission policies. Given that half <strong>of</strong>NZ’s population live in <strong>the</strong> upper North Island,recruiting strategies for The University <strong>of</strong> Aucklandmight target outer metropolitan, regionaland rural <strong>school</strong>s in this region. Because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>strong relationship <strong>between</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>school</strong> <strong>decile</strong>and rurality identified in this study, an increasein <strong>the</strong> proportion <strong>of</strong> students from outside majorcities in <strong>the</strong> rural origin pathway would have <strong>the</strong>corollary <strong>of</strong> more students coming from lower<strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s. It might not be necessary to haveano<strong>the</strong>r specific pathway. Over time, we hope tohelp shed light on this debate.14. Blustein DL, Chaves AP, Diemer MA, Gallagher LA, et al.Voices <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forgotten half: <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> social class in <strong>the</strong><strong>school</strong>-to-work transition. J Couns Psychol. 2002;49:311–323.15. Zedlow PB, Preston RC, Daugherty SR. The decision toenter a medical specialty: timing and stability. Med Educ.1992;26:327–32.16. Big Cities. School <strong>decile</strong> ratings. [document on <strong>the</strong> Internet].Quality <strong>of</strong> Life ’08; 2008 [cited 19 December, 2008]. Availablefrom: http://www.bigcities.govt.nz/pdf2001/<strong>decile</strong>.pdf.17. Medical Council <strong>of</strong> New Zealand. The New Zealand medicalworkforce in 2007. Wellington: Medical Council <strong>of</strong> NewZealand; 2007.18. Valgum P, Wiers-Jenssen J, Ekeberg O. Motivation for medical<strong>school</strong>: <strong>the</strong> relationship to gender and specialty preferences ina nationwide sample. Med Educ. 1999;33:236–42.19. Zayas LE, McGuigan D. Experiences promoting healthcarecareer interest among high-<strong>school</strong> students from underservedcommunities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(9):1523–1531.20. Ma<strong>the</strong>rs J, Parry J. Why are <strong>the</strong>re so few working-class applicantsto medical <strong>school</strong>s? Learning from <strong>the</strong> success stories.Med Educ. 2009;43:21–228.References1. Angel CV, Johnson A. Broadening access to undergraduatemedical education. BMJ. 2000;321:1136–8.2. Lakhan SE. Diversification <strong>of</strong> U.S. medical <strong>school</strong>s via affirmativeaction implementation. BMC Med Educ. 2003;3:6.3. Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M. The role <strong>of</strong> Black andHispanic physicians in providing health care for underservedpopulations. New Engl J Med. 1997;4:1305–1310.4. Easterbrook M, Godwin M, Wilson R, Hodgetts G et al. Ruralbackground and clinical rotations during medical training:effect on practice location. CMAJ. 1999;160:1159–63.5. Hsueh W, Wilkinson T, Bills J. What evidence-based undergraduateinterventions promote rural health? N Z Med J.2004;117(1204):U1117.6. Garlick PB, Brown G. Widening participation in medicine.BMJ. 2008;336:1111–1113.7. Medical Training Board. Collation <strong>of</strong> discussion papers released30 September 2008. Wellington: Government PublishingService; 2008.8. Ministry <strong>of</strong> Education. How <strong>the</strong> <strong>decile</strong> is calculated [documenton <strong>the</strong> Internet]. Wellington: MOH; 2008 [cited 19 December,2008]. Available from: http://www.minedu.govt.nz/educationSectors/Schools/SchoolOperations/Resourcing/OperationalFunding/Deciles/HowTheDecileIsCalculated.aspx.9. Roulston D. Educational policy change, newspapers andpublic opinion in New Zealand, 1988–1999. Victoria University<strong>of</strong> Wellington: Wellington; 2005.10. Shulruf B, Hattie J, Tumen S. Individual and <strong>school</strong> factorsaffecting students’ participation and success in higher education.J Higher Educ. 2008;56(5):613–632.11. Heath C, Stoddart C, Renwick J. Urban and rural origins <strong>of</strong>Otago Medical students. N Z Med J. 2002;115(1165).12. Heath C, Stoddart C, Green H. Parental backgrounds <strong>of</strong> Otagomedical students. N Z Med J. 2002;115(1165):U233.13. Thompson MN, Subich LM. The relation <strong>of</strong> social statusto <strong>the</strong> career decision-making process. J Vocat Behav.2006;96:289–301.COMPETING INTERESTSNone declared.VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010 J OURNAL OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE 189

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPERSquantitative researchbegan at <strong>the</strong> start <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 2009 <strong>school</strong> year <strong>of</strong>feringvaccination to girls in Year 8 and above(12 years up). Administration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Gardasil ®vaccine is recommended at an early age asyounger girls mount a greater antibody responseand <strong>the</strong>refore may be afforded better protectionagainst <strong>the</strong> virus, 3 and vaccination prior to sexualdebut ensures girls have not already been exposedto <strong>the</strong> virus. 4In NZ, Maori and Pacific women have <strong>the</strong> highestincidence <strong>of</strong> cervical cancer and a poorerprognosis once diagnosed. 5,6 Disparities have alsobeen reported in access to both screening (breastand cervical) and immunisation for Maori andPacific women. 5–7 The National HPV immunisationimplementation plan <strong>the</strong>refore recognisesMaori and Pacific as priority groups for vaccination,with additional funding provided to DHBsto address <strong>the</strong>se priority groups. 8 To achieve highuptake, and to minimise <strong>the</strong> risk <strong>of</strong> increasing inequalitiesfor both Maori and Pacific, we need anunderstanding <strong>of</strong> those factors that may increase,or conversely hinder, widespread coverage.Studies have been conducted overseas to exploreparental attitudes towards <strong>the</strong> new HPV/cervicalcancer vaccine. 9–19 NZ research has exploredparental views towards o<strong>the</strong>r childhood vaccines,and barriers to vaccination. 20–23 Place <strong>of</strong> vaccinationis an important factor when consideringaccess and uptake; <strong>the</strong> success <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> MeNZB TMprogramme that was predominately <strong>school</strong>-based(for five- to 17-year-olds) played a role in <strong>the</strong>decision to deliver Gardasil ® via <strong>school</strong>s, despitedifferences in <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> disease targetedby <strong>the</strong>se vaccines. 8 Non-return <strong>of</strong> signed consentforms prohibits receipt <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> vaccine. Analysis<strong>of</strong> data from one DHB region on receipt <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>11-year-old vaccine (dip<strong>the</strong>ria/tetanus/whoopingcough) showed that Maori were significantly lesslikely to return consent forms than non-Maori. 23By contrast, consent form return rates were highfor Maori in <strong>the</strong> MeNZB TM programme. 8The cervical cancer vaccine differs from o<strong>the</strong>rson <strong>the</strong> immunisation schedule in a number<strong>of</strong> important ways. For example, it targets aninfection that is sexually transmitted and ismost effective when administered prior to sexualonset, it reduces likelihood <strong>of</strong> developing aWHAT GAP THIS FILLSWhat we already know: The HPV/cervical cancer vaccine has <strong>the</strong> potentialto reduce current disparities in cervical cancer incidence for Maori andPacific if high uptake is achieved. The vaccine will be delivered via a <strong>school</strong>basedprogramme in most areas <strong>of</strong> New Zealand to girls in Year 8 and above.What this study adds: Parents indicated a preference for <strong>the</strong>ir daughters’receipt <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> HPV/cervical cancer vaccine in primary care, and many wouldseek <strong>the</strong> views <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir GP before making a decision about vaccination for<strong>the</strong>ir daughter(s). The rationale for vaccination at a young age needs to be explainedclearly and information provided in a way that is accessible to parentsfrom all backgrounds.time-distant disease, and is currently only availablefor girls. Given <strong>the</strong> unique nature <strong>of</strong> thisvaccine, we aimed to explore factors that mightimpact on uptake, including: parents’ preferenceson where <strong>the</strong>ir daughter(s) receive <strong>the</strong> vaccineand at what age; age-appropriate informationfor girls; information needed to assist parentswith decision-making; parental contact regardingconsent and information-sharing <strong>between</strong> <strong>school</strong>and primary care.MethodsThe study was approved by <strong>the</strong> Central RegionEthics Committee on 17 June 2008(CEN/08/04/014). Surveys were distributed to<strong>school</strong>s in October and November in term 4 <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> 2008 <strong>school</strong> year. Return <strong>of</strong> a completedsurvey signified a parent’s consent to participate;surveys were received up until <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> January2009. Questions were developed based on findingsfrom key informant interviews conductedwith parents, similar work conducted overseasand local attitudinal research on immunisation.20–22 Surveys were piloted with 15 participants,and modified following feedback on clarityand ambiguity in question formatting.Recruitment and distribution <strong>of</strong> surveysEligibility criteria for <strong>school</strong>s included: locatedin Wellington, more than 100 pupils (with <strong>the</strong>exception <strong>of</strong> one Kura Kaupapa Maori languageimmersion <strong>school</strong> that had fewer than 100pupils), and attended by girls in Year 8 and above(intermediate and <strong>secondary</strong> <strong>school</strong>s). SchoolsVOLUME 2 • NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010 J OURNAL OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE 191

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPErSquantitative researchwere stratified by <strong>decile</strong> rating into low (<strong>decile</strong>s1–3), medium (<strong>decile</strong>s 4–7) and high (<strong>decile</strong>s 8–10).Schools with lower ratings had higher proportions<strong>of</strong> Maori and Pacific students so were oversampledto achieve good representation <strong>of</strong> priority groups.The <strong>decile</strong> rating <strong>of</strong> a <strong>school</strong> is an indicator <strong>of</strong>socioeconomic status <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population within<strong>the</strong> <strong>school</strong>-defined area, where children attendinga <strong>decile</strong> 1 <strong>school</strong> are likely to be from a lowersocioeconomic background than those attending a<strong>decile</strong> 10 <strong>school</strong>. 24 All eligible <strong>school</strong>s in <strong>the</strong> Wellingtonarea with <strong>decile</strong> ratings <strong>between</strong> 1 and 5were invited to participate. Schools with <strong>decile</strong>ratings <strong>of</strong> 6 and above were randomly chosen (using<strong>the</strong> Excel RAND function).A letter <strong>of</strong> invitation was sent to <strong>the</strong> principal at22 <strong>of</strong> 41 eligible <strong>school</strong>s (10 low, six medium andsix high <strong>decile</strong>). Arrangements for administering<strong>the</strong> survey were made and a $50 book vouchergiven as a token <strong>of</strong> appreciation. Parents wereeligible for participation if <strong>the</strong>y had a daughterattending one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> participating <strong>school</strong>s.Surveys (with a brochure about cervical cancerand <strong>the</strong> HPV vaccine) 25 were distributed in one <strong>of</strong>two ways, as nominated by <strong>the</strong> <strong>school</strong>: girls took<strong>the</strong> survey home to <strong>the</strong>ir parents (10 <strong>school</strong>s),or <strong>the</strong> <strong>school</strong> posted <strong>the</strong> survey to parents (four<strong>school</strong>s). For three high-<strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s with largerolls, we asked <strong>school</strong>s to distribute surveys toparents <strong>of</strong> only half <strong>the</strong>ir students. Surveys werereturned directly to <strong>the</strong> researchers by freepostenvelope (eight <strong>school</strong>s), or students returned surveysto <strong>the</strong> <strong>school</strong> with small incentives <strong>of</strong>feredby <strong>the</strong> <strong>school</strong> (for example, entry into a draw towin vouchers) in an attempt to increase responserates. Reminder notices about completion andreturn <strong>of</strong> surveys were sent out by all <strong>school</strong>sin <strong>the</strong>ir newsletters and/or in daily notices. Theresearch team did not send reminders to nonrespondersas contact details for parents were notobtained due to privacy reasons.Data collection and analysisQuestionnaires collected demographic data andasked parents about <strong>the</strong>ir vaccination preferenceswith regards to age, venue and information needs,as well as <strong>the</strong> likelihood <strong>of</strong> seeking vaccinationfor <strong>the</strong>ir daughter(s). Ethnicity was collectedusing <strong>the</strong> 2001 NZ census question and wasrecoded to <strong>the</strong> following four groups: Maori, Pacific,New Zealand European (NZEu) and O<strong>the</strong>r.Assignment was based on prioritised ethnicity. 26‘Strongly agree’ and ‘agree’ responses were pooledfor analysis, as were ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘disagree’responses. Comments made to open-endedquestions were analysed for content and coded toallow for a frequency count (reason for preferenceon place <strong>of</strong> vaccination, format and content <strong>of</strong>fur<strong>the</strong>r information if desired). Kruskal-Wallistests followed by Wilcoxon pairwise comparisonswere performed in situations where data couldnot be assumed to follow a normal distribution.For <strong>the</strong>se pairwise comparisons, Bonferroni correctionswere applied to control for Type I errorresulting from multiple comparisons (significancelevel set at 0.05/n comparisons). Chi-square testswere performed to test for significant differences<strong>between</strong> categorical variables, and 95% confidenceintervals calculated where appropriate. Statisticalanalyses were performed using SAS (v9.2).ResultsFifteen <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 22 <strong>school</strong>s agreed to participate and,<strong>of</strong> those, 14 took part (six co-ed, two girls only,five intermediate and one full Kura Kaupapa Maori<strong>school</strong>) giving a population <strong>of</strong> 3123 girls in <strong>the</strong>age range. Five <strong>school</strong>s declined (all low <strong>decile</strong>) dueto ‘lack <strong>of</strong> time’, two were undecided (one highandone low-<strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>) after several weeks sowere not fur<strong>the</strong>r pursued. The overall responserate from parents was 24.6% (769/3123). Co-education<strong>secondary</strong> <strong>school</strong>s had <strong>the</strong> lowest responserate (19.6%, 370/1889); followed by intermediate<strong>school</strong>s (30.5%, 215/704), <strong>the</strong> highest response ratewas parents <strong>of</strong> girls at girls-only <strong>secondary</strong> <strong>school</strong>s(35%,182/520). Participating <strong>school</strong>s were spreadacross <strong>decile</strong>s, with a response rate <strong>of</strong> 18.7% fromfour low-<strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s (157/838), 24.4% from sixmedium-<strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s (380/1560) and 32% fromfour high-<strong>decile</strong> <strong>school</strong>s (232/725).Table 1 presents <strong>the</strong> characteristics <strong>of</strong> participatingparents who returned completed surveys(n=769), with p-values denoting significantoverall differences <strong>between</strong> ethnic groups ondemographic variables using chi-square tests forsignificance. Pairwise comparisons showed thatMaori and Pacific parents were significantly more192 VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010 J OURNAL OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPERSquantitative researchlikely to be younger (p

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPErSquantitative researchTable 2. Likelihood <strong>of</strong> seeking vaccination for daughter and preferred venue and age at receipt <strong>of</strong> vaccinationWant daughter to receiveHPV vaccineTotal Maori Pacific NZEu ‘O<strong>the</strong>r’(n=769) (n=126) (n=57) (n=477) (n=109)n % n % n % n % n %(95% CI) (95% CI) (95% CI) (95% CI) (95% CI)514 66.8 84 66.7 36 63.2 323 67.7 71 65.1(63.4 – 70.2) (57.7 – 74.8) (49.3 - 75.6) (63.3 – 71.9) (55.4 – 74.0)Preferred venueClinic* 302 39.3 55 43.7 31 54.4 179 37.5 37 33.9(35.8 – 42.8) (34.8 – 52.8) (40.7 – 67.6) (33.2 – 42.0) (25.1 – 43.6)School 197 25.6 28 22.2 6 10.5 135 28.3 28 25.7(22.6 – 28.9) (15.3 – 30.5) (4.0 – 21.5) (24.3 – 32.6) (17.8 – 34.9)Clinic or <strong>school</strong> 89 11.6 17 13.5 5 8.8 56 11.7 11 10.1(9.4 – 14.0) (8.1 – 20.7) (2.9 – 19.3) (9.0 – 15.0) (5.1 – 17.3)Her choice 156 20.3 21 16.7 10 17.5 98 20.5 27 24.8(17.5 – 23.3) (10.6 – 24.3) (8.7 – 29.9) (17.0 – 24.5) (17.0 – 34.0)No preference /16 2.1 2 1.6 3 5.3 8 1.7 3 2.8Not having it(1.2 – 3.4) (0.2 – 5.6) (1.1 – 14.6) (0.7 – 3.3) (0.6 – 7.8)Preferred ageNever 22 2.9 1 0.8 4 7 12 2.5 5 4.6(1.8 – 4.3) (0.0 – 4.3) (1.9 – 17.0) (1.3 – 4.4) (1.5 – 10.4)Not sure 131 17 21 16.7 15 26.3 74 15.5 21 19.3(14.4 – 19.9) (10.6 – 24.3) (15.5 – 39.7) (12.4 – 19.1) (12.3 – 27.9)Median age 13 13 14 13 15(Interquartile range) (12 – 15) (12 – 14) (13 – 15) (12 – 15) (12.3 – 16)Age 10 years 25 3.3 12 9.5 2 3.5 11 2.3 0 0Age 11 years 24 3.1 7 5.6 1 1.8 11 2.3 5 4.6Age 12 years 167 21.7 31 24.6 5 8.8 115 24.1 16 14.7Age 13 years 121 15.7 18 14.3 5 8.8 89 18.7 9 8.3Age 14 years 88 11.4 15 11.9 7 12.3 59 12.4 7 6.4Age 15 years 76 9.9 9 7.1 9 15.8 42 8.8 16 14.7Age 16 or older 102 13.3 12 9.5 7 12.3 54 11.3 29 26.6* Includes GP or nurse clinic, Maori and Pacific health clinicsNon-return <strong>of</strong> consent formsand information-sharingThe majority <strong>of</strong> parents (87%) were happy to bephoned if <strong>the</strong>y had not returned a consent form(672/769). Few parents (8%) answered ‘no’ tobeing phoned (63/769) and only 3% were unsure.Maori (13%) and Pacific (14%) parents had aslightly higher proportion <strong>of</strong> ‘no’ responses thanNZEu (5.7%) parents (p

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPERSquantitative researchyounger girls (causes and risks <strong>of</strong> cervical cancer,how HPV is passed on, abstinence, possible sideeffects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> vaccine, genital warts and STIs).Table 4 presents data relating to parents’ desirefor more information (o<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> Ministry <strong>of</strong>Health brochure provided) to assist with decisionmakingabout <strong>the</strong> vaccine. Three-quarters <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>se parents (77%) responded to an open-endedquestion about <strong>the</strong> type <strong>of</strong> information <strong>the</strong>ywould want (184/236). Responses included: informationon side effects and risks (39/184); efficacyand long-term effects <strong>of</strong> vaccination (38/184);evidence-based research and scientific information(37/184); and safety (31/184). A few parentsalso noted <strong>the</strong>y would want ‘unbiased’ information,details about vaccine contents, updated informationabout <strong>the</strong> programme, and informationon whe<strong>the</strong>r a booster is needed at five years.DiscussionParents indicated a greater preference for delivery<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Gardasil ® vaccine in clinic ra<strong>the</strong>r than<strong>school</strong> settings. Reasons for clinic-based vaccinationwere, most frequently, that it would allowfor continuity <strong>of</strong> care (from <strong>the</strong> family GP),enable parental involvement and <strong>the</strong> opportunityfor parents to provide comfort and support to<strong>the</strong>ir daughter. Given that <strong>the</strong> HPV vaccinationprogramme will be run predominantly through<strong>school</strong>s, enabling girls to have whanau/familysupport on vaccination day at <strong>school</strong> might bebeneficial. Parents also need to be encouraged toseek vaccination for <strong>the</strong>ir daughter(s) through primarycare if that is <strong>the</strong>ir preference. Conveniencewas cited as a key reason for preferring <strong>school</strong>baseddelivery. In a previous study, parents expresseda preference for delivery <strong>of</strong> childhood immunisations(meningococcal disease and measles)in general practice, with <strong>the</strong> exception <strong>of</strong> Pacificparents who preferred <strong>school</strong>-based delivery 20 —afinding that differs from <strong>the</strong> current study.Just over a quarter <strong>of</strong> parents (28%) thought ages10–12 appropriate for receipt <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> vaccine. Parents<strong>of</strong> Pacific and ‘O<strong>the</strong>r’ ethnicities were morelikely to indicate a preference for older age at re-Table 3. Information deemed appropriate for girls when discussing <strong>the</strong> HPV vaccineWhat should be discussed withgirls aged 12–15, and girls aged 16and older?*Topic (n responding to question)‘Yes’ responses presented by age groupBoth age groups 16 years and older only 12 to 15 years only Nei<strong>the</strong>r age groupn % n % n % n %(95% CI) (95% CI) (95% CI) (95% CI)Cervical cancer—causes and risks 615 95.3 28 4.3 1 0.2 1 0.2(645) (93.4 – 96.8) (2.9 – 6.2) (0.0 – 0.9) (0.0 – 0.9)HPV: What it is and how it’s passedon (during sexual contact) 587 92.2 47 7.4 2 0.3 1 0.2(637) (89.8 – 94.1) (5.5 – 9.7) (0.0 – 1.1) (0.0 – 0.9)Cervical screening and pap smears 545 86.6 78 12.4 1 0.2 5 0.8(629) (83.7 – 89.2) (9.9 – 15.2) (0.0 – 0.9) (0.3 – 1.8)Practising safe sex 545 86.6 78 12.4 1 0.2 5 0.8(629) (83.7 – 89.2) (9.9 – 15.2) (0.0 – 0.9) (0.3 – 1.8)Not having sex 490 78 26 4.1 42 6.7 69 11(628) (74.6 – 81.2) (2.7 – 6.0) (4.9 – 8.9) (8.6 – 13.7)Possible side effects <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> vaccine 603 94.2 27 4.2 2 0.3 8 1.3(640) (92.1 – 95.9) (2.8 – 6.1) (0.0 – 1.1) (0.5 – 2.4)Genital warts and STIs 559 86.7 53 8.2 2 0.3 16 2.5(630) (86.0 – 91.1) (6.4 – 10.9) (0.0 – 1.1) (1.5 – 4.1)* Respondents were asked to answer for both age groups. A number <strong>of</strong> parents responded only for <strong>the</strong> age group in which <strong>the</strong>ir daughter fell, so <strong>the</strong>ir responses are notrecorded here to avoid skewing <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> data.VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010 J OURNAL OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE 195

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPErSquantitative researchTable 4. Desire for more information to assist decision about vaccinationInformation needsWant more informationbefore deciding on HPVvaccinationTotal Maori Pacific NZEu O<strong>the</strong>r(n=769) (n=126) (n=57) (n=477) (n=109)n % n % n % n % n %(95% CI) (95% CI) (95% CI) (95% CI) (95% CI)Yes 236 30.7 34 27 25 43.9 141 29.6 36 33(27.4 – 34.1) (19.5 – 35.6) (30.7 – 57.6) (25.5 – 33.9) (24.3 – 42.7)No 405 52.7 64 50.8 22 38.6 263 55.1 56 51.4(49.1 – 56.2) (41.7 – 59.8) (26.0 – 52.4) (50.5 – 59.7) (41.6 – 61.1)Don’t know 94 12.2 21 16.7 7 12.3 52 10.9 14 12.8Would seek o<strong>the</strong>r’s viewsabout <strong>the</strong> vaccine(10 – 14.7) (10.6 – 24.3) (5.1 – 23.7) (8.2 – 14.0) (7.2 – 20.6)Yes 582 75.7 96 76.2 47 82.5 358 75.1 81 74.3(72.5 – 78.7) (67.8 – 83.3) (70.1 – 91.3) (70.9 – 78.9) (65.1 – 82.2)No 137 17.8 19 15.1 4 7 96 20.1 18 16.5(15.2 – 20.7) (9.3 – 22.5) (1.9 – 17.0) (16.6 – 24.0) (10.1 – 24.8)Don’t know 41 5.3 7 5.6 3 5.3 22 4.6 9 8.3If Yes, would seek views <strong>of</strong>:(3.9 – 7.2) (2.3 – 11.1) (1.1 – 14.6) (2.9 – 6.9) (3.8 – 15.1)P-value*Extended family/whanau 231 39.7 48 50 18 38.3 143 39.9 22 27.2

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPERSquantitative researchceipt <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> vaccine. This might reflect characteristics<strong>of</strong> parents in <strong>the</strong>se groups; <strong>the</strong>y were morelikely to be immigrants (over 50% have English asa second language), and have a religious affiliationso might have different views on <strong>the</strong> appropriateage for vaccination. A recent NZ study reportedthat practice nurses would be more likely torecommend <strong>the</strong> vaccine to girls aged 16–26 (thanto younger girls), and that GPs would most likelyrecommend <strong>the</strong> vaccine to girls aged 13–15 yearsold, followed closely by 9–12-year-olds. 27 In <strong>the</strong>current programme, <strong>the</strong> vaccine will be <strong>of</strong>feredto girls in Year 8 (girls aged 12), <strong>the</strong>refore carefulexplanation will be needed for parents (andhealth providers) to understand <strong>the</strong> importantreasons for vaccination at this age.The majority <strong>of</strong> parents deemed informationrelating to HPV vaccination (presented in Table 3)suitable for girls <strong>of</strong> all vaccine-eligible ages.Cervical screening and pap smears, practisingsafe sex, genital warts and STIs were thoughtto be appropriate for discussion only with girlsaged 16 and older by 8–12% <strong>of</strong> parents. A third <strong>of</strong>parents wanted more information about Gardasil ®before making a decision about vaccination, andmany indicated that <strong>the</strong>y would seek <strong>the</strong> views<strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs—most commonly those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> familydoctor (GP). A telephone survey <strong>of</strong> 1052parents conducted in 2009 also showed <strong>the</strong> GP/nurse/medical centre was <strong>the</strong> preferred place toget information on <strong>the</strong> vaccine. 28 As with o<strong>the</strong>rvaccines, health pr<strong>of</strong>essionals’ endorsement andsupport <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> HPV vaccine will be important toensure <strong>the</strong> success <strong>of</strong> this programme. Henniger’ssurvey showed that GPs and practice nurses indicateda high level <strong>of</strong> willingness to recommend<strong>the</strong> vaccine to <strong>the</strong>ir patients. 27With parental or patient permission, receipt <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> HPV vaccine will be recorded on <strong>the</strong> NationalImmunisation Register (NIR), and authorisedhealth pr<strong>of</strong>essionals will be able to access thisinformation. Parents in this study were happy forinformation-sharing to occur <strong>between</strong> <strong>the</strong> NIRand primary care, stating that it was importantthat <strong>the</strong>ir daughter’s GP receive this informationfor <strong>the</strong>ir records. However, it appears that GPs/health providers are not routinely notified when<strong>the</strong>ir patients receive Gardasil ® at <strong>school</strong>, but canrequest information on <strong>the</strong>ir patients’ vaccinationstatus. This lack <strong>of</strong> information-sharing willpotentially limit opportunities for vaccination.Parents were also happy to be phoned if <strong>the</strong>yhad not returned a consent form to enable <strong>the</strong>irdaughter’s receipt <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> vaccine. Resources t<strong>of</strong>ollow-up on consent forms will be particularlyimportant in <strong>school</strong>s or areas known to have lowreturn rates <strong>of</strong> (any) <strong>school</strong>-related paperworkfrom parents. The mass communicationcampaign, integrated information systems(<strong>school</strong>s and primary care) and <strong>the</strong> resources tosupport recall and follow-up have been cited askey to <strong>the</strong> success <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> MeNZB TM programme.Our findings support <strong>the</strong> view <strong>of</strong> Grant etal. who advocated for an integrated systemto enable all opportunities for immunisationwith Gardasil ® to be utilised, 29 with vaccineadministration and information-sharing <strong>between</strong>primary care and education providers.This is <strong>the</strong> first NZ study to describe parents’preferences on where and when <strong>the</strong>ir daughters’receive <strong>the</strong> Gardasil ® vaccine. The inclusion <strong>of</strong>groups most at-risk for cervical cancer (Maori,Pacific and lower socioeconomic groups) is astrength <strong>of</strong> this research. By targeting <strong>school</strong>sknown to have a higher proportion <strong>of</strong> Maori andPacific students, we aimed to oversample parentsin <strong>the</strong>se ethnic groups, but response rates weregenerally lower from those <strong>school</strong>s. The distribution<strong>of</strong> our predominantly female participantsacross ethnic groups (62% European, 16.4% Maoriand 7.4% Pacific) closely reflects that <strong>of</strong> femalesaged 30–55 in <strong>the</strong> Wellington region where 70%are European, 11.7% Maori and 4.7% Pacific. Respondentsmay be more representative <strong>of</strong> parentswho have stronger views towards this vaccine.Pacific parents most <strong>of</strong>ten responded in waysthat differed from <strong>the</strong> three o<strong>the</strong>r groups, butfindings should be interpreted with caution dueto <strong>the</strong> smaller sample size (n=57). The responserate (25%) and recruitment <strong>of</strong> parents from onlyone region limits <strong>the</strong> generalisability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> findingsbeyond <strong>the</strong> study participants. However, <strong>the</strong>response rate is likely to be slightly higher thanthat reported, as we were generous in <strong>the</strong> number<strong>of</strong> surveys distributed to <strong>school</strong>s, having beengiven estimates <strong>of</strong> student numbers at participating<strong>school</strong>s. A survey <strong>of</strong> parent attitudes to HPVVOLUME 2 • NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010 J OURNAL OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE 197

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPErSquantitative researchACKNOWLEDGEMENTSWe gratefully acknowledgeparticipation by 769parents and <strong>the</strong>irdaughters as well asprincipals and <strong>the</strong>ir<strong>school</strong>s for facilitatingdistribution and return<strong>of</strong> surveys. Thanks alsoto a small advisory groupfor early advice on <strong>the</strong>study, and to Dr JamesStanley (Biostatistician,Department <strong>of</strong> PublicHealth) for statisticaladvice and assistancewith analyses.FUNDINGThis study was fundedby a grant from <strong>the</strong>Health Research CouncilPartnership programme(REF 08/602).COMPETING INTERESTSNone declared.vaccination achieved a similar response rate (22%)in <strong>the</strong> United Kingdom, 30 and <strong>the</strong> Christchurchsurvey <strong>of</strong> GPs and practices nurses reached a 39%response rate. 27ConclusionsWe suggest that a programme jointly deliveredin primary care and <strong>school</strong> settings, that is appropriatelyresourced for follow-up and information-sharingwould increase vaccine coverage.The rationale for vaccination at age 12 needsto be made clear to parents and evidence-basedinformation needs to be delivered appropriately toparents and girls. As with o<strong>the</strong>r vaccines, healthpr<strong>of</strong>essionals’ endorsement <strong>of</strong> and support forthis new programme will be important to ensureits success.References1. Muñoz N, Bosch FX, Castellsagué X, Díaz M, Sanjose Sd,Hammouda D, et al. Against which human papillomavirustypes shall we vaccinate and screen? The international perspective.Int J Cancer. 2004;111(2):278–85.2. Wiley DJ, Douglas J, Beutner K, Cox T, Fife K, Moscicki AB, etal. External genital warts: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention.Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:S210–S24.3. Block SL, Nolan T, Sattler C, Barr E, Giacoletti KE, MarchantCD, et al. Comparison <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> immunogenicity and reactogenicity<strong>of</strong> a prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus(types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine in maleand female adolescents and young adult women. Pediatrics.2006;118(5):2135–45.4. Villa LL, Costa RL, Petta CA, Andrade RP, Paavonen J, IversenOE, et al. High sustained efficacy <strong>of</strong> a prophylactic quadrivalenthuman papillomavirus types 6/11/16/18 L1 virus-likeparticle vaccine through five years <strong>of</strong> follow-up. Br J Cancer.2006;95(11):1459–66.5. Robson B, Purdie G, Cormack D. Unequal Impact: Maori andNon-Maori Cancer Statistics 1996–2001. Wellington: Ministry<strong>of</strong> Health Report; 2006. [Accessed Dec 2009]:Available from:http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/pagesmh/4761/$File/unequal-impact-maori-nonmaori-cancer-statistics-96-01.pdf.6. Centre for Public Health Research. Annual monitoring report2004, National Cervical Screening Programme. Wellington:Massey University; 2007.7. Ministry <strong>of</strong> Health. Immunisation handbook 2006. Wellington,New Zealand: Ministry <strong>of</strong> Health; 2006.8. Ministry <strong>of</strong> Health HPV Project Team. The HPV (HumanPapillomavirus) Immunisation Programme: National ImplementationStrategic Overview. Population Health Directorate,Wellington: Ministry <strong>of</strong> Health; 2008. [Accessed Aug2009]:Available from: http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/pagesmh/7893/$File/hpv-national-implementation-strategicoverview.pdf.9. Waller J, Marlow LAV, Wardle J. Mo<strong>the</strong>rs’ attitudes towardspreventing cervical cancer through human papillomavirusvaccination: a qualitative study. Cancer Epidemiol BiomarkersPrev. 2006;15(7):1257–61.10. Olshen E, Woods ER, Austin SB, Luskin M, Bauchner H. Parentalacceptance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> human papillomavirus vaccine. J AdolescHealth. 2005;37(3):248.11. Brabin L, Roberts SA, Kitchener HC. A semi-qualitativestudy <strong>of</strong> attitudes to vaccinating adolescents against humanpapillomavirus without parental consent. BMC Public Health.2007;7:20.12. Vallely LA, Roberts SA, Kitchener HC, Brabin L. Informingadolescents about human papillomavirus vaccination: whatwill parents allow? Vaccine. 2008;26(18):2203–10.13. Dempsey AF, Zimet GD, Davis RL, Koutsky L. Factors that areassociated with parental acceptance <strong>of</strong> human papillomavirusvaccines: a randomized intervention study <strong>of</strong> written informationabout HPV. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1486–93.14. Chan SSC, Cheung TH, Lo WK, Chung TKH. Women’s attitudeson human papillomavirus vaccination to <strong>the</strong>ir daughters.J Adoles Health. 2007;41(2):204.15. Marshall H, Ryan P, Roberton D, Baghurst P. A cross-sectionalsurvey to assess community attitudes to introduction <strong>of</strong>human papillomavirus vaccine. Aust NZ J Public Health.2007;31(3):235–42.16. Constantine NA, Jerman P. Acceptance <strong>of</strong> human papillomavirusvaccination among Californian parents <strong>of</strong> daughters:a representative statewide analysis. J Adolesc Health.2007;40(2):108–15.17. Hausdorf K, Newman B, Whiteman D, Aitken J, Frazer I. HPVvaccination: what do Queensland parents think? Aust NZ JPublic Health. 2007;31(3):288–9.18. Marlow LAV, Waller J, Wardle J. Parental attitudes to prepubertalHPV vaccination. Vaccine. 2007;25(11):1945.19. Ogilvie GS, Remple VP, Marra F, McNeil SA, Naus M, PielakK, et al. Intention <strong>of</strong> parents to have male children vaccinatedwith <strong>the</strong> human papillomavirus vaccine. Sex Trans Infect.2008;84(4):318–23.20. Petousis-Harris H, Turner N, Soe B. Parent views on <strong>school</strong>based immunisation. NZ Fam Phys. 2004;31(4):222–28.21. Petousis-Harris H, Turner N, Kerse N. New Zealand mo<strong>the</strong>rs’knowledge <strong>of</strong> and attitudes towards immunisation. NZ FamPhys. 2002;29(4):240–46.22. Petousis-Harris H, Goodyear-Smith F, Godinet S, Turner N.Barriers to childhood immunisation among New Zealand mo<strong>the</strong>rs.NZ Fam Phys. 2002;29(6):396–401.23. Loring BJ, Curtis ET. Routine vaccination coverage <strong>of</strong> 11 yearolds, by ethnicity, through <strong>school</strong>-based vaccination in SouthAuckland. N Z Med J. 2009;122(1291):14–21.24. Ministry <strong>of</strong> Education. Frequently asked questions about<strong>decile</strong>s. Wellington: Ministry <strong>of</strong> Education; 2007. [AccessedJun 2009]: Available from: http://www.minedu.govt.nz/index.cfm?layout=document&documentid=7696&data=l25. Ministry <strong>of</strong> Health. Cervical cancer vaccine brochure—information for girls, young women and <strong>the</strong>ir familes. Ministry<strong>of</strong> Health website: HPV Immunisation programme 2008.[Accessed Aug 2008]:Available from: http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexmh/immunisation-diseasesandvaccineshpv-programme#resources.26. Ministry <strong>of</strong> Health. Ethnicity data protocols for <strong>the</strong> health anddisability sector. Wellington: Ministry <strong>of</strong> Health; 2004. [AccessedFeb 2010]:Available from: http://www.nzhis.govt.nz/moh.nsf/pagesns/228/$File/ethnicity-data-protocols.pdf.27. Henninger J. Human papillomavirus and papillomavirusvaccines: knowledge, attitudes and intentions <strong>of</strong> general practitionersand practice nurses in Christchurch. J Primary HealthCare. 2009;1(4):278–85.28. Wyllie A, Brown R. HPV vaccine communications first trackingmonitor. Research report for GSL network on behalf <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Ministry <strong>of</strong> Health. 2009; October (Phoenix Research, Unpublished).29. Grant CC, Turner N, Jones R. Eliminating ethnic disparities inhealth through immunisation: New Zealand’s chance to earnglobal respect. N Z Med J. 2009;122(1291):10–13.30. Brabin L, Roberts SA, Farzaneh F, Kitchener HC. Future acceptance<strong>of</strong> adolescent human papillomavirus vaccination: Asurvey <strong>of</strong> parental attitudes. Vaccine. 2006;24(16):3087.198 VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 3 • SEPTEMBER 2010 J OURNAL OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPERSquantitative researchIncreasing <strong>the</strong> uptake <strong>of</strong> opportunisticchlamydia screening: a pilot study in generalpracticeBeverley A Lawton ONZM, MBChB, FRNZCGP, DObst; 1 Sally B Rose PhD; 1 C Raina Elley MBChB, PhD; 2Collette Bromhead PhD; 3 E Jane MacDonald MBChB, FAChSHM, DTM&H; 4 Michael G Baker MBChB,FAFPHM, FRACMA, DComH, DObst 5ABSTRACTIntroduction: Genitourinary Chlamydia trachomatis infection is common and associated with considerablepersonal and public health cost. Effective detection strategies are needed.Aim: To assess feasibility <strong>of</strong> an opportunistic incentivised chlamydia screening programme in generalpractice over six months.MethodS: This study was designed as a pilot for a randomised controlled trial in primary care. Threegeneral practices were randomly allocated to intervention (two practices) and control groups. Theintervention involved practice education, self-sample collection and practice incentives (funding andfeedback) for a three-month ‘active’ intervention period. Feedback and education was discontinued during<strong>the</strong> second three-month period. Practice-specific nurse- or doctor-led strategies were developed foridentifying, testing, treating and recalling male and female patients aged 16–24 years. The main outcomemeasure was <strong>the</strong> difference <strong>between</strong> <strong>the</strong> practices’ chlamydia screening rates over <strong>the</strong> six months followingintroduction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> intervention, controlling for baseline rates from <strong>the</strong> previous year.Results: Chlamydia testing rates during <strong>the</strong> year prior to <strong>the</strong> intervention ranged from 2.9% to 7.0%<strong>of</strong> practice attendances by 16–24-year-olds. The intervention practices had higher rates <strong>of</strong> screeningcompared with <strong>the</strong> control practice (p