Jennifer R.B. Miller G.S. Rawat K. Ramesh - Keck Science Department

Jennifer R.B. Miller G.S. Rawat K. Ramesh - Keck Science Department

Jennifer R.B. Miller G.S. Rawat K. Ramesh - Keck Science Department

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Jennifer</strong> R.B. <strong>Miller</strong>G.S. <strong>Rawat</strong>K. <strong>Ramesh</strong>

Copyright © 2008 by <strong>Jennifer</strong> R.B. <strong>Miller</strong>The Wildlife Institute of India, PO Box #18, Chandrabani, Dehradun 248001,Uttrakhand, IndiaCover photographs: Mountain scene at Koilipoi camp, GHNP © <strong>Jennifer</strong> R.B. <strong>Miller</strong>;Plumages of Western Tragopan, Himalayan Monal and Koklass Pheasant, modified fromphotos © John CorderThe authors welcome discussion on the data and conclusions in this report. Please contactjennie.r.miller@gmail.com with your comments.Suggested citation:<strong>Miller</strong>, J.R.B., <strong>Rawat</strong>, G.S., and K. <strong>Ramesh</strong>. 2008. Pheasant population recovery as anindicator of biodiversity conservation in the Great Himalayan National Park, India.Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, India.

TABLE OF CONTENTSLIST OF TABLES _________________________________________________________ iLIST OF FIGURES _________________________________________________________ iiLIST OF PLATES_________________________________________________________ iiiLIST OF APPENDICES _____________________________________________________ ivPROJECT BACKGROUND AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS _____________________________ vABSTRACT______________________________________________________________ 11 INTRODUCTION_________________________________________________________ 21.1 Human Exclusion as a Conservation Practice _____________________________ 21.2 The Great Himalayan National Park (GHNP) as a Case Study ________________ 31.3 Biodiversity Conservation Efforts in the Great Himalayan National Park _______ 41.4 The Need for Ecological Assessment ___________________________________ 91.5 Study Objectives __________________________________________________ 112 METHODS____________________________________________________________ 132.1 Design Overview __________________________________________________ 132.2 Study Species _____________________________________________________ 132.3 Intensive Study Site ________________________________________________ 152.4 Population Abundance Estimates______________________________________ 172.5 Interviews with Villagers and Park Officials_____________________________ 192.6 Analysis _________________________________________________________ 203 RESULTS ____________________________________________________________ 22

3.1 Population Abundance Estimates______________________________________ 223.1.1 Overall Abundance _____________________________________________ 223.1.2 Abundance by Transect__________________________________________ 223.1.3 Abundance by Forest Type _______________________________________ 253.1.4 Abundance by Elevation Range ___________________________________ 253.2 Group Characteristics for Himalayan Monal_____________________________ 283.3 Call Frequency for Koklass Pheasant and Western Tragopan________________ 303.4 Interviews________________________________________________________ 304 DISCUSSION __________________________________________________________ 334.1 Recovery of Pheasants and Park Biodiversity ____________________________ 334.2 Causes of Recovery ________________________________________________ 344.2.1 Impacts of the Ban on NTFP Collection_____________________________ 354.2.2 Impacts of the Declining Gucchii __________________________________ 364.3 Management Recommendations ______________________________________ 374.4 Final Remarks ____________________________________________________ 415 REFERENCES _________________________________________________________ 42

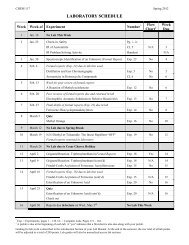

LIST OF TABLESTable 1. Characteristics of the sampling units used to estimate pheasant populationabundances ______________________________________________________ 16Table 2. Mean and change in encounter rate before and after the ban on natural resourceharvesting in the Great Himalayan National Park ________________________ 24Table 3. Male to female composition ratio of male-female combined groups ________ 29Table 4. Encounter rates of Koklass Pheasant and Western Tragopan from comparablestudies__________________________________________________________ 34i

LIST OF FIGURESFigure 1. Location and composition of the Great Himalayan National Park___________ 6Figure 2. Map of the intensive study area in the Great Himalayan National Park _____ 16Figure 3. Depiction of call count stations used to measure population abundances forKoklass Pheasant and Western Tragopan ______________________________ 19Figure 4. Encounter rates before and after natural resource harvesting was banned____ 23Figure 5. Encounter rates by forest type in 2008_______________________________ 26Figure 6. Encounter rates by elevation range in 2008 ___________________________ 27Figure 7. Proportion of observations of Himalayan Monal in each elevation range ____ 28Figure 8. Group characteristics of Himalayan Monal observed in 2008 _____________ 29Figure 9. Calling frequency of Koklass Pheasant and Western Tragopan in 2008 _____ 30Figure 10. Buying price for dried gucchii over time in Gushani and Banjar _________ 31ii

LIST OF PLATESPlate 1. Photographs of gucchii ____________________________________________ 47Plate 2. Photographs of study species _______________________________________ 48Plate 3. Photographs of Kharongcha villagers_________________________________ 49iii

LIST OF APPENDICESAppendix 1. Data sheet for measuring population abundance of Himalayan Monal ___ 50Appendix 2. Data sheet for transects ________________________________________ 51Appendix 3. Data sheet for measuring population abundances of Koklass Pheasant andWestern Tragopan ________________________________________________ 52Appendix 4. Data sheet for call count stations_________________________________ 53Appendix 5. Detailed descriptions of transect and call count stations_______________ 54iv

ABSTRACTFor the past two decades, the Great Himalayan National Park (GHNP) in HimachalPradesh has been the site of a series of conservation efforts utilizing societal development asa tool for protecting biodiversity. From 1994 to 1999, the Forest <strong>Department</strong> implemented anecodevelopment program in and around the Ecodevelopment Zone of the GHNP. Subsequentfinal notification of the park generated a ban on extraction of non-timber forest products bythe local people. While the social implications of these events have been examined at length,the ecological consequences have been poorly studied. To test whether the ban on naturalresource collection in the GHNP impacted biodiversity, I compared the populationabundances of Himalayan Monal (Lophophorus impejanus), Koklass Pheasant (Pucrasiamacrolopha) and Western Tragopan (Tragopan melanocephalus) between 1998 and 2008.Encounter rates collected with transect walks and call counts indicated that abundances for allthree pheasant populations increased significantly over the ten years. Population recoveryappears to have been stimulated by a reduction in human disturbance from the finalnotification ban and a natural decline in morel mushrooms (gucchii), a targeted non-timberforest product. Pheasant abundance is increasing although some people continue to extractnatural resources in spite of the ban, suggesting that complete human exclusion may beneither achievable nor necessary in many remote protected areas, such as the GHNP. Thisreport discusses how biodiversity conservation can accommodate multiple stakeholdersthrough active regulation of natural resource use that involves mutual agreement with localcommunities. Finally, I make management recommendations for future conservation effortsin the park and the surrounding communities.1

Himalayan moist temperate forest, sub-alpine forest and alpine scrub (Champion & Seth1968, Negi 1996). Prominent fauna include the threatened musk deer (Moschuschrysogaster), snow leopard (Uncia uncia) and the state bird of Himachal Pradesh, theWestern Tragopan (Tragopan melanocephalus). The park falls within one of the ICDPBiodiversity Project Endemic Bird Areas of the World and contains a total of 203 identifiedbird species (International Council for Bird Preservation 1992, Wildlife Institute of India1999). Pandey 2008 contains a vivid description of the past and current legal, political andsocio-economic settings of the GHNP and its surrounding communities. Thus, I provide hereonly a brief background of conservation efforts in the park.Villagers living around the GHNP have historically depended on natural resources ina sustainable manner, grazing their livestock and harvesting food, fodder and firewood in theforests (Tucker 1997). However, a growing demand for medicinal plants and morelmushrooms (Morchella esculenta) by expanding international commercial markets during the1960’s led to a sudden increase in the collection of NTFPs. By 1997, villagers were earning70 percent of their cash income from the extraction and sale of NTFPs, especially medicinaland aromatic plants from the GHNP premises (Tandon 1997). Recognizing the danger ofunsustainable harvest on the local people and environment, the Indian government initiatedecodevelopment efforts in the communities around the park to lessen their dependency on theprotected area.5

Figure 1. Location and composition of the Great Himalayan National Park, including the intensive study area Source: <strong>Ramesh</strong> 2003.6

Between 1994 and 1999, the Forest <strong>Department</strong> of Himachal Pradesh received a loanof US $1 million from the International Development Agency of the World Bank to fund theConservation of Biodiversity Project in the Ecodevelopment Zone of the GHNP. TheEcodevelopment Zone contains 127 villages and 14,000 people historically dependent onnatural resources inside park borders (Pandey 2004, Mathur et al. 2004). Under this program,the management authorities of GHNP organized microplan units called VillageEcodevelopment Committees, in which forest officials collaborated with local villagers toassess community needs and implement ecodevelopment projects. The Forest <strong>Department</strong>also initiated Women Saving and Credit Groups and a conservation-awareness street theatregroup. Stakeholders were educated about alternative forms of income generation, such asvermi-composting, organic farming, medicinal plant cultivation, seed oil extraction, souvenircrafts and ecotourism (Pandey 2008). Simultaneously, the program supported a massivecollaboration between Indian and international scientists to gather baseline on the biologicaland social environment in the GHNP and the surrounding communities (see Wildlife Instituteof India 1999). Many components of the ecodevelopment program ended with the project’sconclusion in 1999, and only the Women Saving and Credit Groups, education campaignsand ecotourism efforts continue to exist today. They are now jointly supervised by the GHNPForest <strong>Department</strong> and a non-government organization called the Society for Advancementof Hill and Rural Areas (SAHARA).The Forest <strong>Department</strong> instated a ban on extraction of all NTFPs from the parkimmediately following the termination of the ecodevelopment program. Although theHimachal Government declared the designation of GHNP on 1 March 1984, legal status wasnot constituted until 28 May 1999. As per the Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1972, allconsumptive use of biomass within the park was subsequently forbidden and monetary7

compensation was provided to individuals who had written rights in the historic SettlementReport of the area (Pandey 2004).Angered by the sudden restrictions to the resources of the GHNP, many of the localpeople protested final notification by destroying park properties such as bridges, inspectionhuts and rest houses. This was a severe blow to the park’s infrastructure and the Forest<strong>Department</strong> is still in the process of rebuilding these structures (Brockington & Igoe 2006,author’s personal observation). Since 1999, villagers have continued to petition in lessconfrontational ways by requesting politicians to reinstate their rights in the park in exchangefor election votes (Baviskar 2003, Chhatre & Saberwal 2005). The Forest <strong>Department</strong> lacksthe necessary funds and manpower to coordinate consistent enforcement of the law againstNTFP collection, further amplifying poor relations between forest officials and villagepeople. The few forest guards that patrol the park often lack personal motivation and thusoverlook the violation of legislation, turning a blind eye to intruders (Nangia & Kumar 2001,Saberwal 2003).Throughout history, many protected areas have first closed their borders to adjacentcommunities and only later implemented ecodevelopment projects to help the affected peopleadapt their lifestyles and livelihoods. This model denies villagers their basic source ofsustenance, livelihood and tradition without offering them an alternative, perpetuating theirpoverty and enflaming their relations with park authorities. In contrast, management in theGHNP applied a reverse series of events, in which final notification of the park excludednatural resource use after ecodevelopment had been initiated. This order of “education first,application second” theoretically creates a smoother transition for the villagers and providesan ideal scenario from which we can study the effects of these interventions (ecodevelopmentand exclusion) on the biodiversity value of the managed system.8

1.4 The Need for Ecological AssessmentWhile the social and economic implications of the park management have beendiscussed at length (Wildlife Institute of India 1999, Badola 2000, Nangia & Kumar 2001,Chhatre 2003, Misra & Gokhale 2003, Gouri et al. 2004, Chhatre & Saberwal 2005, Chhatre& Saberwal 2006, Saberwal & Chhatre 2006, Pandey 2008), its impacts on the ecosystem hadyet to be assessed before this report. An evaluation of the environmental response was neededto comprehensively determine the effects of ecodevelopment and exclusionary legislations inthe GHNP and to offer lessons to the world at large.This study attempts to assess the ecological response to final notification of theGHNP and subsequent ban on extraction of NTFPs and livestock grazing in the GHNP. Tosense changes in faunal populations, I compared abundances of the Himalayan Monal(Lophophorus impejanus), Koklass Pheasant (Pucrasia macrolopha) and Western Tragopan(Tragopan melanocephalus) as bioindicators before and ten years after the ban on biomassextraction. Time restrictions and language barriers prevented me from surveying the localcommunities around the GHNP to investigate the long-term impacts of the ecodevelopmentprogram, and data from this study can only offer insight on the impacts of final notification.Additional research is required to target questions of socio-economic progress and accuratelydetermine how the ecodevelopment program of the 1990’s continues to influence localpeople today.Pheasants are ideal indicators for biodiversity because they are extremely sensitivityto human exploitation (Fuller & Garson 2000, Nawaz & Malik 2000). Their omnivorous dietsand preference of a variety of forest types and undergrowth patches make them highlyresponsive to habitat degradation (McGowan & Gillman 1997, Devictor et al. 2008).Pheasants are also an important prey base for raptors and mammalian predators, causingshifts in their population abundances to directly impact higher trophic levels. The distinct9

markings and colorful feathers of the birds have made them a central figure in traditionaldecorations and conservation awareness materials, establishing them as flagship species andcultural keystones recognized and appreciated by both native people and the mainstreampublic (Kumar et al. 1997, Nawaz & Malik 2000). Finally, pheasants can be effectivelysampled during the breeding season, when males are audibly and visibly apparent as theyattempt to attract mates.The GHNP contains five pheasant species (<strong>Ramesh</strong> et al. 1999), of which theHimalayan Monal, Koklass Pheasant and Western Tragopan were chosen for this study. Allthree species have overlapping elevation and habitat niches in the upper temperate forests,offering a perspective on biodiversity responses in an array of habitats. The appropriatesampling techniques (transect walks and call counts) also permit data collection for all threespecies within a single morning, enabling efficient sampling with limited effort.Natural resource extraction and human-wildlife interface issues are significant in thepheasants’ habitats. Previous research suggested that the increasing demand for NTFPs byexpanding commercial markets had led to unsustainable pressure on their habitats and causeda decline in pheasant populations within the GHNP (Gaston & Garsen 1992, <strong>Ramesh</strong> et al.1999). The largest decreases in population abundances of Himalayan Monal, KoklassPheasant and Western Tragopan were most recently noticed during a study conductedbetween 1997 and 1999 and largely attributed to human disturbance associated with thecollection of morel mushrooms, more popularly known as gucchii by Himachal locals(<strong>Ramesh</strong> et al. 1999; Plate 1). These three species are particularly sensitive to this activitybecause their breeding seasons overlap the March-May period when mushrooms are gathered(<strong>Ramesh</strong> 2003). As people scour the forest floor for the inconspicuous mushroom, theydestroy nests, consume eggs, trample habitat and invertebrate prey and permit their domesticdogs to chase and predate upon the birds. In 2008, dried gucchii were sold for Rs. 10,000 (US10

$230) per kilogram in local markets around the GHNP (author’s personal observation) andwere considered a subsidiary source of income for at least 54 percent of households located atthe periphery of the park (Pisharoti 2008). Although banned in 1982, poaching is also stillbelieved to impact pheasant populations (Tucker 1997). A recent survey found that pheasantswere hunted in as many as 83 percent of the 75 villages sampled around the GHNP, withofftake rates per hunting household of approximately one Himalayan Monal and WesternTragopan and eight Koklass Pheasants per year (Kaul 2004).1.5 Study ObjectivesThe primary goal of this study was to assess the ecological impact of the 1999 finalnotification of GHNP and resulting ban on biomass extraction, using pheasants as anindicator taxon for the status of the overall biodiversity in the park. This broad goal wasfocused through specific objectives:• Determine the current status of pheasant populations, and compare pheasantabundances in 2008 to abundances in 1998.• Evaluate how the ban has affected local peoples’ behavior with regards to collectionof NTFPs.• Sense how changes in the amount of NTFP collection has impacted pheasantabundance.This report presents the study’s findings on how populations of the Himalayan Monal,Koklass Pheasant and Western Tragopan have responded to final notification and the ban inthe Tirthan Valley area of the GHNP. I draw correlations between changes in populationabundances and the reduction in human disturbance following the ban on natural resourceutilization. My results indicate that population recovery in the GHNP may be occurringdespite a low level of continued human disturbance, suggesting that biodiversity conservation11

in some protected areas may permit a more lenient and inclusive management approach thancomplete human exclusion. Finally, I make suggestions for future research and monitoringefforts that could be initiated to more deeply understand the impacts of both final notificationand ecodevelopment on the GHNP social and ecological system.12

2 METHODS2.1 Design OverviewI compared pheasant population abundance estimates between springs 1997-1999 andspring 2008, framing the 1999 ban on NTFP collection as the experimental treatment. Datafrom 1997-1999 was taken from a study on pheasant ecology conducted in the park by<strong>Ramesh</strong> et al. (1999). I collected data during 2008 according to the sampling design in<strong>Ramesh</strong> et al. 1999 to enable direct comparison between years. Data collection during bothperiods was carried out during the peak of breeding season in April and May, when pheasantsoccupy the full range of their natural habitats. In addition to sampling pheasants, I alsointerviewed villagers and park officials to sense the amount of natural resource harvestingwithin the GHNP over time.<strong>Ramesh</strong> et al. (1999) recorded the lowest pheasant abundances during 1998, and datafrom this year was utilized for direct comparison to 2008 abundances to illustrate the greatestpotential impact of final notification. Data from the full span of 1997-1999 was used tocomment on pheasant habitat and elevation preferences, since the larger sample size offeredmore profound insight on the birds’ behaviors.2.2 Study SpeciesThe Himalayan Monal is perhaps the most well recognized pheasant species of theWestern Himalaya (Plate 2a). The male’s brilliant, rainbow-colored plumage and importanceto Himachal folklore (Delacour 1977) have contributed to the species’ high status as thenational bird of Nepal and the state bird of Uttarakhand, India. Although well established inthe GHNP, the Monal is declared a protected species under the Indian Wildlife (Protection)Act of 1972 because of habitat degradation and hunting pressure throughout its range.Hunting has decreased substantially since made illegal in Himachal during 1982 (Tucker13

1997), but the male Monal continues to be targeted by poachers for its crest feather, whichHimachal village men use to ornament their ceremonial hats (Kumar et al. 1997, <strong>Ramesh</strong>2003). The Himalayan Monal ranges from eastern Afghanistan through the Himalayan areasof Pakistan, India, Nepal, Southern Tibet and Bhutan and favors upper temperate oak andconifer forests scattered with open grassy slopes, cliffs and alpine meadows between 2,500 mand 4,500 m (Johnsguard 1986, <strong>Ramesh</strong> 2003).In contrast to the Monal, little is known about the Koklass Pheasant due to itsskulking behavior (Plate 2b). The species is found in temperate broadleaf, conifer and subalpineoak forests with dense undergrowth between 2,100 m and 3,300 m from Afghanistanto central Nepal and northeastern Tibet to northern and eastern China (Johnsgard 1986,Grimmett et al. 1998). The bird is believed to have a large global population size and iscurrently ranked by the IUCN as a species of least conservation concern (2007).With less than 5,000 individuals in the world, the Western Tragopan is considered therarest pheasant in the world (IUCN 2007; Plate 2c). Its narrow endemic range extends fromHazara in northern Pakistan through the states of Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh andthe western part of Garhwal in India (Johnsguard 1986, Grimmett et al. 1998). The speciesfavors broadleaf and coniferous forests with thick undergrowth and bamboo between 2,000 mand 3,000 m in winter. The species was recently announced the state bird of HimachalPradesh and is listed as vulnerable on the IUCN 2007 Red List and in Appendix 1 of CITESand Schedule I the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1972.14

2.3 Intensive Study SiteI measured pheasant abundances along trails within a 16 km 2 intensive study site inTirthan Valley of the GHNP (Fig. 2). Reconnaissance surveys and previous research carriedout by <strong>Ramesh</strong> et al. (1999) indicated that the site supported a substantial population of thestudy species. With elevations between 1,890 m and 3,710 m and several different foresttypes (Table 1), the area represents a wide range of habitat composition and topography. Thesite also lies within close proximity of the Ecodevelopment Zone and was frequented byvillagers collecting mushrooms and grazing their livestock prior to final notification. Thesefactors make the study area an excellent location to evaluate human impacts on theecosystem.15

Figure 2. Map of the intensive study area in the Great Himalayan National Park, Transectsare represented by “T” and call count stations with “C”. Map by K. <strong>Ramesh</strong>.Table 1. Characteristics of the sampling units used to estimate pheasant populationabundances.Transect a Sampling Transect Dominant forest Elevationunits b length (km) type range (m)Rolla-Dulunga T1, C1, C2 c 1.0 Broadleaf 2290-2640Dulunga-GrahaniT2, C3, C4 1.0 Mixed broadleafand conifer2700-2770Shilt-Chorduar T3, C5, C6 1.2 Mixed broadleaf2900-2920and coniferShilt-Dara T4 0.7 Sub-alpine oak 2900-3010Rolla-Basu T5, C7, C8 1.0 Conifer 2420-2655Basu-Koilipoi T6, C9, C10 1.0 Conifer 2710-2870a Transect names reflect the campsite or village located on either end of the footpath.b T=transect; C=call count station.c C2 was used by <strong>Ramesh</strong> et al. (1999) but was not utilized in the current study.16

2.4 Population Abundance EstimatesPheasant abundances were estimated based on a systematic design appropriate to eachspecies’ behavior. I sampled Himalayan Monal with transect walks because the speciesfrequently flushes along trails but calls sporadically during the day (Kaul & Shakya 2001). Incontrast, Koklass Pheasant and Western Tragopan are elusive and elicit audible breeding callsat dawn from April to May; hence, call count is a more effective method for measuringpopulation abundance of these species (<strong>Ramesh</strong> 2003).I sampled six transects and ten call count stations twice per month during April andMay, generating four pseudo-replicates of each. Additional repeat measurements were notpossible due to the limited period of breeding season. <strong>Ramesh</strong> et al. (1999) had designatedtransects as portions of pre-existing footpaths since the inaccessibility of the rough terrainand dense forest made random selection of transects and stations inefficient. The selectedpaths varied in length from 0.7 km to 1.2 km and were located among an assortment ofhabitat types and elevations, with each transect and call count station positioned to representa single dominating forest type (Table 1; see Appendices 2 and 4 for data sheets). Fixedwidths were not employed, but birds were counted only if they could be visually observedwhen flushing. Vegetation density was observed to be consistent enough between 1997-1999and 2008 to prevent differences in sighting ability. I recorded weather conditions (windintensity, precipitation, cloud cover and temperature) during each transect walk and callcount. I avoided sampling pheasants in adverse weather such as thick fog, heavy rainfall orstrong winds because these conditions are thought to alter normal pheasant activity and/orobscure observers’ ability to accurately measure bird presence (Khaling et al. 2002).I walked transects in the mornings before 10:00 am, before Monals left their roostingsites for the day. This timing allowed me to sample abundance in habitat that is critical for17

pheasant survival. Sampling in the morning additionally lowered the chances that villagersand tourists would flush the birds when they occasionally traversed the trails. For eachencounter of Monal, I recorded data on sex, sighting angle, sighting distance, time andlatitude/longitude location (see Appendix 1 for data sheet). Walking pace was standardized toreduce irregularities in sampling effort and abundance estimates.I conducted call counts of Koklass Pheasant and Western Tragopan from call stations,which were fixed circular areas with 300 m listening radii (Fig. 3). Each trail contained oneor two stations positioned 500 m apart to avoid listening overlap between observers. My fieldassistants and I sampled two call stations on each morning, with one observer measuringfrom each station. On the morning of sampling, observers positioned themselves at thestations 15 minutes before first light to minimize disturbance of the pheasants (arrival time atthe station changed with seasonal lighting shifts and ranged from 5:30 am in early April to4:15 am by late May). Observers began sampling at the first audible call and ended one hourafter sunrise, which K. <strong>Ramesh</strong> and I determined to be the most effective period formeasuring both Koklass Pheasant and Western Tragopan. Each call was recorded withrespect to species, time, distance and cardinal direction (see Appendix 3 for data sheet). Aftersampling, observers compared the time and direction of calls to eliminate multiple accountsof the same bird from different stations.18

Figure 3. Depiction of call count stations used to measure population abundances forKoklass Pheasant and Western Tragopan. Source: <strong>Ramesh</strong> 2003.2.5 Interviews with Villagers and Park OfficialsI interviewed villagers and GHNP Forest <strong>Department</strong> officials to sense local opinionson pheasant conservation and harvesting of gucchii from the park. The villagers I interviewedwere predominantly residents of Kharongcha, Dingcha, Ropa and Gushaini. These villagesbelong to a cluster located closest to the GHNP Tirthan Valley entry gate and their residentshave the most access to NTFPs in the park. Officials were forest guards and their assistants(watchers) stationed at the entry gate and Sai Ropa Community Training and Tourist Center.Information on the market value of gucchii between 1998 and 2008 was collectedfrom my assistant, Pritam Singh, who is well informed about mushroom collection in thearea. Pritam gave confident estimates of the average buying price for 2004-2007, but couldnot clearly recall values for years prior to 2004.Interviews were formatted as informal conversations and were not structured assurveys. Because most villagers spoke either Hindi or a local language, my assistant, PritamSingh, translated most conversations into English. To reduce the risk of biased translation, I19

epeated the same questions to various people, including English-speakers, and interpreted anoverall sentiment from the responses I received.2.6 AnalysisI calculated Himalayan Monal and Koklass Pheasant abundances using data fromApril and May 1998 and 2008, since the breeding behaviors of these species remainedconstant during both months. Western Tragopans emitted calls predominantly during Maydue to a later breeding season, and I consequently restricted calculations of Tragopanabundance to May observations so as to reflect their peak calling period and avoid timingbias.I calculated an encounter rate for each pseudo-replicate by dividing the number ofbirds observed by distance (transect walks) or station (call counts). The arithmetic mean foreach transects or call station was pooled to calculate the mean encounter rate and standarddeviation for 1998 and 2008. I checked for the normality of the data and appropriately testedfor statistical differences between years with the Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test (Monaltransect walks) and Paired Samples t-Test (Koklass Pheasant call counts) using SPSS 16.0 forMac. These tests were conducted only on data collected in sampling units common to both1998 and 2008 (n = 9 stations, 6 transects) in order to account for statistical and biologicalvalidity. No statistical tests were performed to analyze Western Tragopan encounter rates dueto a dearth of positive records during the initial study year (1998), and because directcomparison was sufficient to detect variation in the abundance.Encounter rates were also organized by transect, forest type and elevation ranges(based on the distribution of transects where data was collected) to detect differences amongthese factors for all species. Finally, the group characteristics of Himalayan Monals were20

investigated by compiling observations from transect walks and opportunistic sightings andcalculating distributions of group size and sex composition.21

3 RESULTS3.1 Population Abundance Estimates3.1.1 Overall AbundancePopulation abundances for all three pheasant species show large recovery over theten-year period. Himalayan Monal encounter rates tripled from 2.2 ± 1.1 birds/km in 1998 to6.1 ± 3.0 birds/km in 2008 with a significant increase of 3.9 birds/km (z = -2.86, p < 0.005, n= 24; Fig. 4a). Encounter rates for the Koklass Pheasant also tripled from 3.2 ± 1.2birds/station to 10.9 ± 2.9 birds/station, a rise of 7.7 birds/ station (t = -11.5, df = 35, p

Figure 4. Encounter rates before (1998) and after (2008) natural resource harvesting wasbanned, for (a) Himalayan Monal (n=6); (b) Koklass Pheasant (n=9); and (c) WesternTragopan (n=9). Y-bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.23

Table 2. Mean (± SE) and change in encounter rate before (1997-1999) and after (2008) the ban on natural resource harvesting in the GreatHimalayan National Park for (a) Himalayan Monal; (b) Koklass Pheasant; and (c) Western Tragopan.TransectEncounter rate in birds/km (Monal) or birds/station (Koklass and Tragopan)1997-1999 1 2008 Change from1997-1999 to 2008HimalayanKoklassWesternHimalayanKoklassWesternHimalayanKoklassWesternMonalPheasantTragopanMonal 4PheasantTragopanMonalPheasantTragopanRolla-Dulunga 0.8 ± 0.3 1.2 ± 0.3 0.0 0.8 ± 0.3 9.3 ± 0.3 4 0.0 2 0.0 8.1 0.0Dulunga-Grahani 2.4 ± 0.5 0.2 ± 0.1 0.4 ± 0.2 3.0 ± 0.7 10.0 ± 1.2 4 1.5 ± 2.1 3 0.6 9.8 1.1Shilt-Chorduar 3.9 ± 0.5 1.2 ± 0.3 0.0 10.6 ± 2.3 8.6 ± 0.6 6 4.5 ± 0.7 3 6.7 7.4 4.5Shilt-Daran 2.5 ± 0.6 0.7 ± 0.2 0.4 ± 0.1 2.5 ± 0.9 9.0 ± 0.7 4 0.0 2 0.0 8.3 -0.4Rolla-Basu 1.5 ± 0.8 0.3 ± 0.1 0.0 2.0 ± 0.7 7.6 ± 1.3 6 0.8 ± 0.8 5 0.5 7.3 0.8Basu-Koilipoi 1.4 ± 0.4 0.4 ± 0.2 0.2 ± 0.1 8.5 ± 2.5 6.0 ± 1.3 6 1.5 ± 0.6 5 7.1 5.6 2.31 Pooled mean between years, n=11 (<strong>Ramesh</strong> 2003)2 Arithmetic mean, n=13 Arithmetic mean, n=24 Arithmetic mean, n=45 Arithmetic mean, n=66 Arithmetic mean, n=824

3.1.3 Abundance by Forest TypeNo substantial species-specific differences in encounter rates occurred between foresttypes (Fig. 5). All three species are known to inhabit the four forest types sampled in thisstudy (except for Western Tragopan, which does not favor broadleaf forest, as is indicated bythe lack of sightings in broadleaf forest). The overlapping standard errors may confirm thatthe pheasants indeed do not show large preferences for one forest type over another.However, the extremely small sample size (n=1 for broadleaf and oak and n=2 for mixedbroadleaf and conifer and conifer) makes comparison between the groups unsubstantiated andit is impossible to confidently draw conclusions from the data set.3.1.4 Abundance by Elevation RangeComparisons of encounter rates between three elevation ranges showed that mostpheasant species preferred higher elevations. Higher population abundances were measuredfor both Himalayan Monal and Western Tragopan, with no differences arising between the2700-2900m and 2900-3000m ranges (Fig. 6a, 6b). However, a greater proportion ofHimalayan Monal sightings were observed in the highest elevation range, suggesting that thespecies may more commonly frequent upper elevations (Fig. 7). Abundances of KoklassPheasant were equally distributed among all three ranges (Fig. 6b).25

Figure 5. Encounter rates by forest type in 2008 for (a) Himalayan Monal; (b) KoklassPheasant; and (c) Western Tragopan. Y-bars indicate standard error.26

Figure 6. Encounter rates by elevation range in 2008 for (a) Himalayan Monal (n=2); (b)Koklass Pheasant; and (c) Western Tragopan. Y-bars indicate standard error.27

Figure 7. Proportion of observations of Himalayan Monal in each elevation range, includingboth opportunistic and transect observations (n=137).3.2 Group Characteristics for Himalayan MonalAnalysis of Himalayan Monal group characteristics indicated that most birds sightedwere either alone or in pairs (Fig. 8). Very few groups contained more than 4 individuals, aresult consistent with the findings of <strong>Ramesh</strong> (2003). Both males and females were mostcommonly seen alone, and I observed approximately an equal number of single males andfemales (n=25 and n=20, respectively). Of the male-female combined groups that I observed,sexes were most often present in equal proportions or with a higher number of females (Table3).28

Figure 8. Group characteristics of Himalayan Monal observed in 2008 (n=137) for groupsize distribution (top) and sex composition (bottom). Columns illustrate the number of groupsand diamonds represent the mean group size. Y-bars indicate standard deviation.Table 3. Male to female composition ratio of observed male-female combined groups (n=9).Male:Female CompositionNumber of groups1:1 51:2 12:2 22:5 129

3.3 Call Frequency for Koklass Pheasant and Western TragopanA comparison of calling frequency against time between Koklass Pheasant andWestern Tragopan indicated that Tragopan initiated calling as much as 30 minutes beforeKoklass, while Koklass Pheasant continued calling well after Western Tragopan had finished(Fig. 9). Out of the sampled time, both birds called for 60 minutes with 30 minutes of thisperiod overlapping and a simultaneous peak calling time of 5:00-5:14 am. Males from thetwo species appear to be utilizing different time periods, perhaps as an evolved strategy tomaximize their chances of being heard.Figure 9. Calling frequency of Koklass Pheasant (black bars, n=335) and Western Tragopan(light bars, n=44) across sampled times in April and May 2008.3.4 InterviewsInterviews with villagers in the Ecodevelopment Zone indicated that the number ofpeople collecting gucchii has been steadily declining since the ban on collection was imposedwith final notification in 1999. Some people cited the park restriction as a primary reason forending their collection, but many more complained that a decreasing availability of gucchii inthe forest has made collection unsustainable. Consequentially, collectors either dedicate moreeffort and time in the forests with lower productivity or abandon collection altogether in30

Figure 10. Buying price for dried gucchii (morel mushrooms) over time in Gushani andBanjar, two towns located in the Tirthan Valley close to the Great Himalayan National Park.Sources: <strong>Ramesh</strong> 2005 (1994-1998) and current study (2004-2008).favor of agriculture or work in nearby towns. The latter option does not seem to be afavorable or convenient one, as men from the most rural villages such as Kharongcha orDingcha would be forced to either commute two hours each day or live away from theirfamilies in order to work in town. I also heard several men express frustration over theshortage of available day jobs in the nearby cities (Gushani and Banjar), raising the questionof whether the current job market can even withstand a surge of new workers.In response to a falling supply of gucchii, middlemen have been raising their buyingprice on a yearly basis. The market buying price for one kilogram of dried gucchii steadilyincreased in value from Rs. 900 (US $20) in 1994 (<strong>Ramesh</strong> et al. 2005) to Rs. 10,000 (US$230) in 2008 (author’s personal observation; Fig. 10). It seems as though the high price ofthe mushroom tends to motivate collection by people who are especially poor (often definedby the villagers as owning no land) or have extra time to dedicate to collection (i.e. they areotherwise unemployed or have enough income to afford the time). Although gucchii continue31

to be a targeted NTFP, people are increasingly reducing their dependence on park resourcesin favor of other, more dependable sources of income.32

4 DISCUSSION4.1 Recovery of Pheasants and Park BiodiversityThe results of this study indicate that abundances of Himalayan Monal, KoklassPheasant and Western Tragopan have increased significantly since livestock grazing and thecollection of NFTPs were banned in the GHNP. In the years immediately prior to finalnotification (1997-1999) during the formative period of ecodevelopment, the pheasantpopulations showed decline in response to human activities in their habitats (<strong>Ramesh</strong> et al.2005). The recent reduction in human disturbance appears to have caused the populations torapidly recover, indicating high species sensitivity to disturbance.This finding is consistent with the conclusions of previous studies on speciesresponses to reduced human disturbance (Madhusudan 2004, Harihar et al. 2008).Additionally, a previous study measuring abundances of the Satyr Tragopan (Tragopansatyra) and Koklass Pheasant in comparable vegetation types with less human disturbancemeasured encounter rates ranging from 5.0 to 7.0 birds/station and 4.2 to 5.7 birds/station,respectively (Kaul & Shakya 2001). The close resemblance to the data of the current study(Table 4) suggests that populations of Western Tragopan and Koklass Pheasant in the GHNPmay be approaching more natural abundances than recorded in the past.As indicator species, the Himalayan Monal, Koklass Pheasant and Western Tragopanmay reflect the conservation status of temperate forest ecosystems of the Western Himalaya.The three pheasant species inhabit a variety of vegetation types between 2,000 m and 4,500m ranging from upper temperate broadleaf, conifer and sub-alpine oak forests to denseundergrowth of bamboo and alpine scrub, to open grassy meadows and slopes, to barren cliffsides (<strong>Ramesh</strong> 2003). The increased abundances of these species suggest that these habitatsin the GHNP may also be quickly recovering. Several mammalian species share the33

pheasants’ habitats, including prominent species such as goral (Nemorhaedus goral),Himalayan tahr (Hemitragus jemlahicus), Asiatic black bear (Ursus thibetanus), Himalayanbrown bear (Ursus arctos), common leopard (Panthera pardus), red giant flying squirrel(Petaurista petaurista) and yellow-throated marten (Martes flavigula). Populations of thesespecies are also likely to benefit from improved habitat quality as a result of lower humandisturbance.Table 4. Encounter rates of Koklass Pheasant and Western Tragopan from comparablestudies.PheasantEncounter rates by source (birds/station)<strong>Ramesh</strong> et al. 1999 Current study Kaul & Shakya2001Koklass Pheasant 3.2 ± 1.2 10.9 ± 2.9 4.2 to 5.7Western Tragopan 0.2 ± 0.0 3.2 ± 1.4 Not measuredSatyr Tragopan Not measured Not measured 5.0 to 7.04.2 Causes of RecoveryEvidence suggests that the recovery of habitat conditions in parts of the GHNP hasbeen stimulated by a reduction in human pressure. Based on my observations in the field, Iattribute changes in human behavior to two possible influences:(1) The ban on livestock grazing and collection of NTFPs resulting from finalnotification, and(2) The decline in abundance of gucchii in the GHNP forests.34

4.2.1 Impacts of the Ban on NTFP CollectionThere is no doubt that the ban on natural resource collection has reduced humanpresence in the GHNP. In my interviews, several local people stated that park restrictions haddeterred them from collecting mushrooms and grazing livestock. Comparisons between myobservations of human presence in the park with K. <strong>Ramesh</strong>’s reflect these statements. In1998, K. <strong>Ramesh</strong> observed groups with as many as 50 people entering the GHNP on a singleday to collect mushroom, yet the biggest group I observed in 2008 consisted of no more than20 individuals. I also observed an absence of domestic dogs in the park during 2008, whereasvillagers had previously brought their dogs for protection against wild animals (<strong>Ramesh</strong> et al.2005). This change would reduce disturbances to breeding pheasants and may reflectvillagers’ attempts to lessen their visibility while collecting NTFPs within the GHNP.Although slack in enforcing restrictions on NFTP collection, the Forest <strong>Department</strong>appears to actively prevent livestock grazing in the park. In a survey of select villages in theTirthan Valley, 10 percent of all households said they no longer graze their livestock insidethe GHNP and 22.7 percent of these cited park restrictions as the primary reason for theirshift (Pisharoti 2008). Some villagers reported confrontations with forest guards in whichthey were repetitively blocked from passing through the entry gate with livestock. One manmentioned that the Forest <strong>Department</strong> had filed a law case against several shepherds,although I could not locate documentation to confirm legal action. Regardless, the rumorseems to have intimidated many villagers and prevented them from attempting to grazelivestock in the park.Income from alternative livelihoods may also have decreased human pressure onpheasant habitat. The organization SAHARA recruits program participants from familiesknown to collect natural resources in the GHNP (Pandey 2008). Approximately 800 womenfrom these households now participate in Women’s Saving and Credit Groups. Many of the35

men work as porters, cooks and guides for SAHARA’s ecotourism group, which providesthem with decent wages and a distraction during the gucchii harvest season. My onlyobservations of lingering ecodevelopment influences were several ecotourist groups led bySAHARA employees that I encountered in the GHNP. Further research is necessary todetermine whether these supplemental incomes reduce families’ dependence on naturalresources.4.2.2 Impacts of the Declining GucchiiFinal notification of the GHNP occurred just as the gucchii population began todecline, making it challenging to deduce which of these two factors had a greater impact onecological conservation. An especially poor mushroom harvest that occurred between Apriland June 1999 led to low human activity during this year (K.R.’s personal observation),making it virtually impossible to judge the immediate impact of the ban in May 1999.However, my interviews and observations, as well as the drastic price rise of gucchii in thelocal market, are signs that fewer villagers may have collected mushroom in 2008 than 1998.A reduction in the number of people gathering mushrooms would likely stimulateenvironmental restoration because collection causes extensive disturbance. Gucchii are small,cream-colored fungi that typically grow on the ground around fallen trees. Their camouflagedappearance makes them difficult to locate, forcing collectors to stray from park trails andtrample vegetation as they meticulously scour the forest floor. Villagers living in the TirthanValley are also incredibly resourceful and tend to gather a plethora of natural productswhenever they are in the forest. I observed villagers collecting feathers, bamboo, wood,fruits, vegetables, herbs and even trash that they found in the park. Reducing this impactwould certainly lessen the impact on the ecosystem.36

4.3 Management RecommendationsIt is highly probable that the increases in pheasant abundance are not due to parkrestrictions or mushroom decline alone, but rather to a combination of the two factors.Although the GHNP is legally closed to collection of biomass, in reality villagers continue topressure the habitat, although in lesser degree. Yet despite the continued disturbance,pheasant populations no longer appear to be declining. A threshold may have been crossed,reestablishing a balance in the system and allowing villagers and pheasants to again coexist.The data of this study are too preliminary to make strong conclusions and thus additionalresearch is needed to determine whether the system is sustainable.With this in mind, I suggest the following recommendations for future management inthe GHNP:1. Regulate Rather Than Remove VillagersThe equilibrium indicates that regulation rather than elimination of people’s activitiesmay be a plausible compromise for conservation in the GHNP. The management must ensurethat this transformation is stable enough to survive considerable changes in the system, suchas an exceptionally high annual yield of mushroom or a lack of alternative sources of income.One potential regulation scheme could be to distribute complimentary permits formushroom collection within the buffer forests and adjacent sanctuaries. This would track andcontrol human presence during critical months for threatened fauna, such as the May-Junebreeding season for the Western Tragopan. In addition to conserving habitat, this actionwould strengthen the trust between the Forest <strong>Department</strong> and villagers by formallyrecognizing local people’s needs and the environment’s ability to accommodate some level ofhuman disturbance.37

Although many challenges would accompany active regulation, its attainment is notinconceivable. Forest guards will need to be personally motivated to carry out their duties,since frontline presence is directly correlated to the effectiveness of a management program(Brunner et al. 2001). The Forest <strong>Department</strong> in Himachal Pradesh has already taken asignificant step towards solving this problem. They recently hired and trained new wildlifeguards who have accomplished high levels of education, many of them with postgraduatedegrees in biology. These individuals are apt to infuse the <strong>Department</strong> force with knowledge,fresh perspectives and self-initiated passion for conservation.2. Initiate Ecological and Social Monitoring and ResearchAs suggested in this case, frequent monitoring efforts are another simple yet essentialcomponent of evaluating the success of park management. In my study, the timing of finalnotification created an ideal yet unintentional experimental circumstance. Yet this reportexamines only one ecological component (pheasants) of a complex system, and the currentdearth of monitoring data has prevented a comprehensive evaluation of the biological andsociological responses to both final notification and ecodevelopment. Monitoring programsaimed at vital ecological and sociological issues can help protected area managers remainaware of the conditions in their areas and maintain a realistic understanding of therelationship between local communities and biodiversity.The GHNP authorities have already planned a Long Term Monitoring Project and thiseffort should be consistently carried out. Ecotourist groups led by SAHARA could collect orcomment on ecological conditions, with the benefit of simultaneously supplementing regularmonitoring data and educating tourists.I also suggest continued monitoring of the Tirthan Valley populations of HimalayanMonal, Koklass Pheasant and Western Tragopan. The research conducted by K. <strong>Ramesh</strong>38

(<strong>Ramesh</strong> et al. 1999, <strong>Ramesh</strong> 2003, <strong>Ramesh</strong> 2005) and myself (current study) providepopulation abundance estimates from 1997, 1998, 1999 and 2008, thus providing an excellentbeginning to a longer monitoring project of pheasants in the GHNP. At the end of this report,I include a detailed description of my sampling units for future data collection (Appendix 5).Although both K. <strong>Ramesh</strong> and I sampled the species over a two-month period, samplingcould be focused in the month of May, when both Koklass and Tragopan males call, toreduce the time required. During my study, I trained Vijay Thakur, one of the newly hiredWildlife Guards, to conduct pheasant call counts and transect walks. Mr. Thakur couldeffectively monitor these pheasants on a yearly basis with the guidance of Pritam Singh, avillager from Kharongcha who worked as a lead research assistance for both K. <strong>Ramesh</strong> andmyself. Monitoring of these species would measure the rate of recovery and determinewhether the populations are stable.Maintaining an accurate record of villagers entering the Tirthan Valley entry gate iscritical for fully understanding the ecological and social systems in and around the GHNP.Many of the conclusions in this report would gain more credibility if supported by data ongucchii. I strongly encourage that the Forest <strong>Department</strong> initiate a project to meticulouslyexamine collection of gucchii and other NTFPs in the GHNP. In addition, when K. <strong>Ramesh</strong>visited the GHNP at the end of my study, he commented on the large amount of vegetationre-growth compared to his last visit in 2000. The change may be a result of decreasedlivestock grazing and a research study on the vegetation response to the final notification banwould be useful to understanding the system. Researchers at the Wildlife Institute of Indiahave expressed interest in these issues and I am confident they would be enthusiastic aboutcollaborating on such projects.39

3. Implement More Intensive Ecodevelopment EffortsThe current situation in which people are dishonoring legal obligations and continuingto exploit the park’s resources signifies that the ecodevelopment investment was notstaggered according to the level of dependency, and that the program has not fully benefitedthe communities. The higher effort level now required to harvest gucchii means that amajority of collectors are driven by poverty. This is an opportune time for the Forest<strong>Department</strong> to initiate another round of intensive ecodevelopment and target villagers whoare still dependent on NTFPs. Hopefully a fresh management perspective would succeed inguiding these people into more stable and sustainable sources of livelihood.3. Appropriate Zonation of the Park and Buffer ZoneThis study suggests that pheasant populations (and possibly the greater biodiversity)within the study site in the Tirthan Valley can co-exist with a minimal level of humandisturbance. It seems that the area proximate to the study site may not require the strictprotection laws that accompany national park status (i.e. a complete ban on biomassextraction) for biodiversity to be conserved. A more feasible and pragmatic strategy may beto designate such areas as Wildlife Sanctuary or Buffer Zone to allow local people traditionalresource-use in a sustainable manner. National Park zonation could accordingly be restrictedto more sensitive or degraded core forest areas of the park region. However, additionalstudies on other aspects of the ecosystem besides pheasants should be carried out prior to rezonationto ensure that human disturbance is not causing detrimental effects on biodiversitythat the current study may have overlooked.40

4.4 Final RemarksThe findings of this study indicate that conservation can successfully move awayfrom a battle against local people towards an approach that reaches compromise between allstakeholders. The recovery of pheasant populations in the GHNP is an encouraging casestudy for other protected areas in India and the world at large, and serves as a testament of thepositive impacts that can result from appropriate park management.41

5 REFERENCESAgrawal, A., and C.C. Gibson. 1999. Enchantment and disenchantment: the role ofcommunity in natural resource conservation. World Development 27:629-649.Badola, R. 1999. People and protected areas in India. Unaslyva 50. Available fromhttp://www.fao.org/docrep/x3030e/x3030e05.htm (accessed September 2008).Badola, R. 2000. Local people amidst the changing conservation ethos: relationships betweenpeople and protected areas in India. Pages 187-201 in T. Enters, P.B. Durst, and M.Victor, editors. Decentralization and devolution of forest management in Asia and thePacific. RECOFTC Report N-18 and RAP Publication 2000/1. Regional Office forAsia and the Pacific, Bangkok, Thailand. Available fromhttp://www.fao.org/docrep/003/x6898e/x6898e05b.htm (accessed August2008).Baviskar, A. 2003. States, communities and conservation: the practice of ecodevelopment inthe Great Himalayan National Park. Pages 267-299 in V.K. Saberwal and M.Rangarajan, editors. Battles over nature: <strong>Science</strong> and the politics of conservation.Permanent Black, Delhi, India.Brockington, D., and J. Igoe. 2006. Eviction for conservation: a global overview.Conservation and Society 4:424-470.Brunner, A.G., Gullison, R.E., Rice, R.E., and G.A.B. da Fonseca. 2001. Effectiveness ofparks in protecting tropical biodiversity. <strong>Science</strong> 291:125-128.Champion, H.G., and S.K. Seth. 1968. A revised survey of forest types of India. Manager ofPublications, New Delhi, India.Chhatre, A. 2003. The mirage of permanent boundaries: politics of forest reservation in theWestern Himalayas, 1875-97. Conservation and Society 1:137-163.42

Chhatre, A., and V. Saberwal. 2005. Political incentives for biodiversity conservation.Conservation Biology 19:310-317.Chhatre, A., and V. Saberwal. 2006. Democracy, development and (Re-) visions of nature:rural conflicts in the western Himalayas. Journal of Peasant Studies. 33:678-706.Convention on Biological Diversity. 1992. Multilateral: Convention on biological diversity(with annexes). United Nations – Treaty Series 1760:142-382.Delacour, J. 1977. The Pheasants of the World. Spur Publications and the World PheasantAssociation, United Kingdom.Devictor, V., Julliard, R., and F. Jiguet. 2008. Distribution of specialist and generalist speciesalong spatial gradients of habitat disturbance and fragmentation. Oikos 117:507-514.Dowie. M. 2008. Eviction slip. Guernica. New York, NY. Available fromhttp://www.guernicamag.com/features/556/post_1/ (Accessed September2008).Fuller, R.A., and P.J. Garson, editors. 2000. Pheasants: status survey and conservation actionplan 2000-2004. IUCN Publications Services Unit, Cambridge, United Kingdom.Gouri, Mudgal, S., Morrison E., and J. Mayers. 2004. Policy influences on forest-basedlivelihoods in Himachal Pradesh, India. International Institute for Environment andDevelopment, London.Grimmet, R., Inskipp, C., and T. Inskipp. 1998. Birds of the Indian subcontient. OxfordUniversity Press, Delhi, India.Harihar, A., Pandav, B., and S.P. Goyal. 2008. Responses of tiger (Panthera tigris) and theirprey to removal of anthropogenic influences in Rajaji National Park, India. EuropeanJournal of Wildlife Research DOI 10.1007/s10344-008-0219-2.Hayes, T.M. 2006. Parks, people, and forest protection: an institutional assessment of theeffectiveness of protected areas. World Development 34:2064-2075.43

International Council for Bird Preservation. 1992. Putting biodiversity on the map: priorityareas for global conservation. International Council for Bird Preservation, Cambridge,United Kingdom.Kathari, A. and A. Patel. 2006. Environment and human rights: an introductory essay andessential readings. New Delhi, India. National Human Rights Commission.Kaul, R., and S. Shakya. 2001. Spring call counts of some Galliformes in the Pipar Reserve,Nepal. Forktail 17:75-80.Khaling, S., Kaul, R., and G.K. Saha. 2002. Calling behavior and its significance in SatyrTragopan, Tragopan satyra (Galliformes: Phasianidae) in the Singhalila NationalPark, Darjeeling. Proceedings of the Zoological Society (Calcutta) 55:1-9.Kumar, S.R., <strong>Rawat</strong>, G.S., and S. Sathyakumar. 1997. Winter habitat use by HimalayanMonal (Lophophorus impejanus) in Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary, WesternHimalaya. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 103:49-56.Lynch, O.J. 1992. Securing community based tenurial rights in the tropical forests of Asia –an overview of current and prospective strategies. Issues in Development, WorldResources Institute, Washington, D.C.Madhusudan, M.D. 2004. Recovery of wild large herbivores following livestock decline in atropical Indian wildlife reserve. Journal of Applied Ecology 41:858–869.McGowan, P.J.K., and M. Gillman. 1997. Assessment of the conservation status of partridgesand pheasants in South East Asia. Biodiversity and Conservation 6:1321-1337.McNeely, J.A. 1994. Protected areas for the 21 st century: working to provide benefits tosociety. Biodiversity and Conservation 3:390-405.Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2003. Ecoystems and human well-being. Pages 71-84 inWorld Resources Institute. Ecosystems and human well-being: a framework forassessment. Island Press, Washington, D.C., United States.44

Misra, M.K, and S.S. Gokhale. 2003. Base line information on medicinal plants conservationand sustainable utilization. Himachal Pradesh. Foundation for Revitalisation of LocalHealth Traditions, Bangalore, India. Available fromhttp://www.frlht.org.in/html/reports/arunachal%20pradesh.pdf (accessed August2008).Nangia, S., and P. Kumar. 2001. Population and environment interface in the GreatHimalayan National Park. International Union for the Scientific Study of Population,Paris, France. Available fromhttp://www.iussp.org/Brazil2001/s00/S08_P08_Sudesh.pdf (accessed August 2008).Nawaz, R., Garson, P.J., and M. Malik. 2000. Monitoring pheasant populations in montaneforests: some lessons learnt from the Pakistan Galliformes Project. Pages 196-209 inGalliformes 2000: Proceedings of the 2 ndInternational Galliformes Symposium.World Pheasant Association, Reading, United Kingdom.Negi, G.C.S., Rikhari, H.C., Ram, J., and S.P. Singh. 1993. Foraging niche characteristics ofhorses, sheep and goats in an alpine meadows of the Indian Central Himalaya. Journalof Applied Ecology 30:383-94.Pandey, S. 2008. Linking ecodevelopment and biodiversity conservation at the GreatHimalayan National Park, India: lessons learned. Biodiversity Conservation 17:1543-1571.Pisharoti, P.M. 2008. Livelihood changes in response to restrictions on resource extractionfrom the Great Himalayan National Park. National Centre for Biological <strong>Science</strong>s,Bangalore, India.<strong>Ramesh</strong>, K. 2003. An ecological study on pheasants of The Great Himalayan National Park,Western Himalaya. Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, India.45

<strong>Ramesh</strong>, K., Sathyakumar, S., and G.S. <strong>Rawat</strong>. 1999. Ecology and conservation status ofpheasants of the Great Himalaya National Park, Western Himalaya. Wildlife Instituteof India, Dehradun, India.<strong>Ramesh</strong>, K., Sathyakumar, S., and G.S. <strong>Rawat</strong>. 2005. Recent trends in the pheasantpopulation in Great Himalayan National Park, Western Himalaya: conservationimplications. Pages 40-43 in Wildlife Conservation, Research and Management. Y.V.Jhala, R. Chellam and Q. Qureshi (editors). Technical report RR-05/001. WildlifeInstitute of India, Dehradun, India.Saberwal, V.K. 2003. Conservation by state fiat. Pages 240-263 in V.K. Saberwal and M.Rangarajan. Battles over nature: science and the politics of conservation. PermanentBlack, Delhi, India.Saberwal, V., and A. Chhatre. 2006. Democratizing nature: politics, conservation, anddevelopment in India. Oxford University Press, New Delhi, India.Tandon, V. 1997. Report on the status of collection, conservation, trade and potential forgrowth in sustainable use of major medicinal plant species. Wildlife Institute of India,Dehradun, India.Tiger Task Report. 2005. Union Ministry of Environment and Forests (Project Tiger), NewDelhi, India.Tucker, R. 1997. The historical development of human impacts on the Great HimalayanNational Park. Winrock International and Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, India.Wildlife Institute of India. 1999. An ecological study of the conservation of biodiversity andbiotic pressures in the Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area – anecodevelopment approach. Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, India.46

Plate 1. Photographs of morel mushrooms (gucchii). After gucchii are collected in the park(right center), the mushrooms are dried (bottom) and then sold in town to middlemen, whoare often well-respected business owners or politicians. <strong>Jennifer</strong> R.B. <strong>Miller</strong>.47

Plate 2. Photographs of study species, male (top) and female (bottom): (a) Himalayan Monal (John Corder); (b) Koklass Pheasant (JeanHowman and Stevenn N) and; (c) Western Tragopan (Sat Pal Dhiman and John Corder).(a) (b) (c)48

Plate 3. Photographs of Kharongcha villagers, who are dependent on the forests around them for fodder and firewood (top left) and for grazingtheir livestock.49

Appendix 1. Data sheet for measuring population abundance of Himalayan Monal.Transect Walk Data SheetTrail name: Observer(s): Date: Starting Time: Ending Time:Weather:Wind speed: 0-15 kph 16-30 kph >30 kphPrecipitation: None Fog Light Rain Heavy Rain HailCloud cover: Sunny Partly cloudy Dense cloudsTemperature: 0-10˚C (32-50˚F) 11-20˚C (50-70˚F) 21-30˚C (70-85˚F) >30˚C (>85˚F)IDSpeciesNumber of birds in flockMale Female Sub UnknadultTotalInitialsight.angleInitialdist.(m)Flushsight.angleFlushdist.(m)GPS UTMs(Northing/Easting)Notes50

Appendix 2. Data sheet for transects.Transect Walk Master Data SheetTrail # and name:Description:Start of trail: UTM Northing: UTM Easting:End of trail: UTM Northing: UTM Easting:Altitude at start:Altitude at end:Vegetation type:Number of streams:Side trail visibility (every 100m or 50m):Evidence of human activities:Photos taken:Notes:51

Appendix 3. Data sheet for measuring population abundances of Koklass Pheasant andWestern Tragopan.Call Count Data SheetTrail: Station #: Observer(s): Date:Starting Time:Ending Time:Weather:Wind speed: 0-15 kph 16-30 kph >30 kphPrecipitation: None Fog Light Rain Heavy Rain HailCloud cover: Sunny Partly cloudy Dense cloudsTemp: 0-10˚C (32-50˚F) 11-20˚C (50-70˚F) 21-30˚C (70-85˚F) >30˚C (>85˚F)Influences on audibility:Remarks:T and time = tragopan K and time = koklass M and time = monalNWE100m200mS300m52

Appendix 4. Data sheet for call count stations.Call Count Master Data SheetTrail # and name:Station #:Description:Center of station: UTM Northing: UTM Easting:Altitude:Vegetation type:Proximity and number of water:Audibility quality (valley, water, rocks, etc):Evidence of human activities:Photos taken:Notes:53

Appendix 5. Detailed descriptions of transect and call count stations.Transect aRolla-DulungaDulunga-GrahaniSamplingunit bT1C1T2C3LatitudeLongitude31˚40’44.7”77˚29’21.2”31˚40'50.6''77˚29'15.6''31˚41'00.3''77˚29'17.3''31˚41'00.4''77˚29'21.7''Start descriptionElevation Physical landmarks c(m)2,372 Approx. 15 min from Rollacamp, first major rockoverhang resting placewhere trail makesswitchback to right ofmountain2,499 Approx 20 min past start oftransect, at steep ascent intrail by large boulders intrail2,726 After initial climb, on flatportion of trail soon afterconifer forest begins2,752 3 min after beginning oftransect at boulderLatitudeLongitude31˚40’58.3”77˚29'13.2''End descriptionElevation Physical landmarks c(m)2,656 Last rock on trail beforeenter meadow clearing forDulunga campsite--- --- ---314˚11'74.''77˚29'23.4''2,736 In small clearing aboveGrahani camp near largeboulder before walkingdown trail to campsiterock overhang--- --- ---C431˚41'12.4''77˚29'22.1''2,752 Approx 10 min from end oftransect at turn in trail nearfallen log that obscures trail--- --- ---54

Shilt-ChorduarT3C5C631˚41'10.3''77˚28'59.5''31˚41'23.7''77˚29'11.4''31˚41'26.7''77˚29'24.0''3,015 Approx. 20 min from Shiltcamp, at rock resting placewith prominent vista pointbefore trail descends2,954 Trail juts out frommountain side before largedescent2,946 At end of transect in fallenlogs31˚41'26.7''77˚29'23.7''2,947 2 min past Chorduar campat fallen logs before traildescends towards stream--- --- ------ --- ---Shilt-DaraRolla-BasuT4C11T5C7C831˚40'55.6''77˚28'53.4''31˚40'52.4''77˚28'51.5''31˚40'27.0''77˚29'23.2''31˚40'22.8''77˚29'25.8''31˚40'20.4''77˚29'41.9''2,948 After trail forks betweenShilt camp trail and Darantrail (take left fork toDaran), just before enteringmeadow clearing2,930 After initial meadowclearing at large boulderbefore entering coniferforest2,356 First prominent restingplace with vista towards themountains southeast ofTirthan Valley, before trailascends2,379 Soon after transect begins,directly after climbingaround large boulders2,663 3 min before Basu camp, atboulder immediately beforelarge fallen tree31˚40'44.1''77˚28'48.1''2,863 After climbing aroundseveral boulders on steepslope before descendingtowards Daran, view ofvillages ahead--- --- ---31˚40'32.2''77˚29'70.5''2,649 1 min walk past Basucamp to turn in trail withlarge rock on mountainsideof trail--- --- ------ --- ---55

Basu-KoilipoiT6C931˚40'10.3''77˚30'02.9''31˚40'01.6''77˚30'23.8''2,870 Approx. 25 min from Basu,at edge before largeclearing on slope after trailascends2,964 At highest ridge on trailamong boulders31˚39'54.9''77˚30'42.4''2,979 On trail in forest beforemeadow clearing forKoilipoi camp--- --- ---C1031˚39'56.7''77˚30'35.7''2,986 5 min before Koilipoi campin down-sloping openmeadow area by gorge--- --- ---a Transect names reflect the campsite or village located on either end of the footpath.b T=transect; C=call count station.c Descriptions are written with the assumption that the observer is starting at the first campsite or village listed in the transect name (i.e. for Rolla-Dulunga, observer is walking from Rolla to Dulunga).56