Mother Tongue-based Literacy Programmes: Case Studies of Good ...

Mother Tongue-based Literacy Programmes: Case Studies of Good ... Mother Tongue-based Literacy Programmes: Case Studies of Good ...

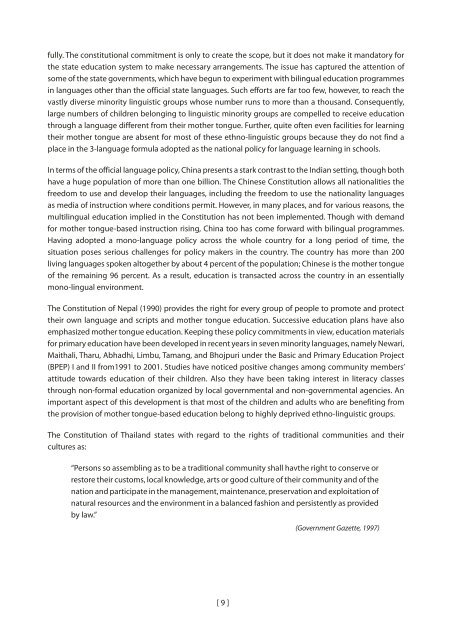

Table 1: Linguistic Contexts of the Case StudiesCOUNTRIES LANGUAGES LITERACY (%) POPULATION #Officiallanguages+Living languages* Extinct languages * Male # Female#Bangladesh 2 39 - 53.9% 31.8% 147,365,352Cambodia 1 21 - 84.7% 64.1% 13,881,427China 1 235 1 95.1% 86.5% 1,313,973,713India 22 415 13 70.2% 48.3% 1,095,351,995Indonesia 1 737 5 92.5% 83.4% 245,452,739Nepal 1 123 3 62.7% 34.9% 28,287,147Thailand 2 74 - 94.9% 90.5% 64,631,595Source: * Ethnologue# www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/countrylisting.html+ These countries also have national language(s), which in many cases overlap with official language.For instance, even a relatively small country like Nepal has 123 living languages, but three otherlanguages have either become extinct or remain only as spoken languages. Linguistic diversity is anequally big challenge in these countries, not only because of the complex logistics it demands, butalso because of the sheer number involved. For instance, in large countries like India and China, even5-10 percent of a population could mean more than 100 million people belonging to linguistic minoritygroups. No national programme of education can ignore this reality if Education for All goals are to carryany meaning. To what extent do the national policies on language use respond to the linguistic diversitycharacterizing the Asia and Pacific countries? This is explored in the next section.An Overview of Language PolicyBangladesh introduced the Compulsory Primary Education Act in 1993 with a view to achievingEducation for All goals. Though free education - including free textbooks and a food-for-educationprogramme - has been introduced to move in this direction, no particular attention has been given tothe needs of the ethno-linguistic indigenous communities in the country. The situation is quite dismalbecause approximately 80 percent of adivasi (original tribal inhabitants) children drop out of schoolwithout completing even the primary cycle. This is often due to feelings of discrimination, povertyand problems of non-comprehension. However, initiatives have been taken in recent years under theauspices of UNESCO, UNICEF and SIL Bangladesh to create awareness about education among theadivasi communities and Bangladeshi society, at large. Various NGOs are also operating schools for theadivasi population in their own language, with a view to increasing their participation in schools andenhancing their learning levels.The Indian Constitution recognizes 22 major languages as national languages. Each of these languagesis spoken by a large number of people inhabiting one or more states, and are recognized as the officiallanguages of those respective states. Linguistic minorities have to be, therefore, identified vis-à-vis theofficial languages of different states. Recognizing the need for special efforts to protect the interests ofthe linguistic minorities, the Indian Constitution states: “It shall be the endeavor of every state and ofevery local authority within the state to provide adequate facilities for instruction in the mother tongueat the primary stage to children belonging to linguistic minority groups.” Does this arrangement fullytake care of the linguistic minority groups’ need to receive education through their mother tongue? Not[8 ]

fully. The constitutional commitment is only to create the scope, but it does not make it mandatory forthe state education system to make necessary arrangements. The issue has captured the attention ofsome of the state governments, which have begun to experiment with bilingual education programmesin languages other than the official state languages. Such efforts are far too few, however, to reach thevastly diverse minority linguistic groups whose number runs to more than a thousand. Consequently,large numbers of children belonging to linguistic minority groups are compelled to receive educationthrough a language different from their mother tongue. Further, quite often even facilities for learningtheir mother tongue are absent for most of these ethno-linguistic groups because they do not find aplace in the 3-language formula adopted as the national policy for language learning in schools.In terms of the official language policy, China presents a stark contrast to the Indian setting, though bothhave a huge population of more than one billion. The Chinese Constitution allows all nationalities thefreedom to use and develop their languages, including the freedom to use the nationality languagesas media of instruction where conditions permit. However, in many places, and for various reasons, themultilingual education implied in the Constitution has not been implemented. Though with demandfor mother tongue-based instruction rising, China too has come forward with bilingual programmes.Having adopted a mono-language policy across the whole country for a long period of time, thesituation poses serious challenges for policy makers in the country. The country has more than 200living languages spoken altogether by about 4 percent of the population; Chinese is the mother tongueof the remaining 96 percent. As a result, education is transacted across the country in an essentiallymono-lingual environment.The Constitution of Nepal (1990) provides the right for every group of people to promote and protecttheir own language and scripts and mother tongue education. Successive education plans have alsoemphasized mother tongue education. Keeping these policy commitments in view, education materialsfor primary education have been developed in recent years in seven minority languages, namely Newari,Maithali, Tharu, Abhadhi, Limbu, Tamang, and Bhojpuri under the Basic and Primary Education Project(BPEP) I and II from1991 to 2001. Studies have noticed positive changes among community members’attitude towards education of their children. Also they have been taking interest in literacy classesthrough non-formal education organized by local governmental and non-governmental agencies. Animportant aspect of this development is that most of the children and adults who are benefiting fromthe provision of mother tongue-based education belong to highly deprived ethno-linguistic groups.The Constitution of Thailand states with regard to the rights of traditional communities and theircultures as:“Persons so assembling as to be a traditional community shall havthe right to conserve orrestore their customs, local knowledge, arts or good culture of their community and of thenation and participate in the management, maintenance, preservation and exploitation ofnatural resources and the environment in a balanced fashion and persistently as providedby law.”(Government Gazette, 1997)[9 ]

- Page 1 and 2: Mother Tongue-basedLiteracy Program

- Page 3 and 4: Mother Tongue-based Literacy Progra

- Page 5 and 6: ContentsAcronymsviPartI 1Mother Ton

- Page 7 and 8: AcronymsIndiaZSSTLCPLPCEIPCLGZSSSRC

- Page 9 and 10: PartI

- Page 11: Mother TongueLiteracy Programmesin

- Page 14 and 15: Entrenchment of the common (majorit

- Page 18 and 19: It may be noted that there is no re

- Page 20 and 21: “If we stop using our language, i

- Page 22 and 23: their normal lives and communicatio

- Page 24 and 25: the project ensured that community

- Page 26 and 27: Also, it was important to identify

- Page 28 and 29: conservation. Tharu traditional pra

- Page 31 and 32: In Thailand, participation in schoo

- Page 33 and 34: would there be projects to cover al

- Page 35 and 36: © UNESCO/D. Riewpituk

- Page 37 and 38: BackgroundBangladesh is a delta lan

- Page 39 and 40: As a consequence, literacy rates am

- Page 41 and 42: Orthography DevelopmentDuring early

- Page 43 and 44: and discussion in the plenary, age-

- Page 45 and 46: qualifications in the tribal commun

- Page 47 and 48: Before opening the school, the rese

- Page 49 and 50: Networking with Other Organizations

- Page 51 and 52: A small baseline study was conducte

- Page 53 and 54: parents of the children studying in

- Page 55 and 56: Awareness Creation and Opinion Form

- Page 57 and 58: Table 2: At-a-Glance Status of MT S

- Page 59 and 60: Tasks for National and Internationa

- Page 61 and 62: © POEYS

- Page 63 and 64: BackgroundCurrent Situation of Mino

- Page 65 and 66: of instruction, but the Bunong chil

fully. The constitutional commitment is only to create the scope, but it does not make it mandatory forthe state education system to make necessary arrangements. The issue has captured the attention <strong>of</strong>some <strong>of</strong> the state governments, which have begun to experiment with bilingual education programmesin languages other than the <strong>of</strong>ficial state languages. Such efforts are far too few, however, to reach thevastly diverse minority linguistic groups whose number runs to more than a thousand. Consequently,large numbers <strong>of</strong> children belonging to linguistic minority groups are compelled to receive educationthrough a language different from their mother tongue. Further, quite <strong>of</strong>ten even facilities for learningtheir mother tongue are absent for most <strong>of</strong> these ethno-linguistic groups because they do not find aplace in the 3-language formula adopted as the national policy for language learning in schools.In terms <strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>ficial language policy, China presents a stark contrast to the Indian setting, though bothhave a huge population <strong>of</strong> more than one billion. The Chinese Constitution allows all nationalities thefreedom to use and develop their languages, including the freedom to use the nationality languagesas media <strong>of</strong> instruction where conditions permit. However, in many places, and for various reasons, themultilingual education implied in the Constitution has not been implemented. Though with demandfor mother tongue-<strong>based</strong> instruction rising, China too has come forward with bilingual programmes.Having adopted a mono-language policy across the whole country for a long period <strong>of</strong> time, thesituation poses serious challenges for policy makers in the country. The country has more than 200living languages spoken altogether by about 4 percent <strong>of</strong> the population; Chinese is the mother tongue<strong>of</strong> the remaining 96 percent. As a result, education is transacted across the country in an essentiallymono-lingual environment.The Constitution <strong>of</strong> Nepal (1990) provides the right for every group <strong>of</strong> people to promote and protecttheir own language and scripts and mother tongue education. Successive education plans have alsoemphasized mother tongue education. Keeping these policy commitments in view, education materialsfor primary education have been developed in recent years in seven minority languages, namely Newari,Maithali, Tharu, Abhadhi, Limbu, Tamang, and Bhojpuri under the Basic and Primary Education Project(BPEP) I and II from1991 to 2001. <strong>Studies</strong> have noticed positive changes among community members’attitude towards education <strong>of</strong> their children. Also they have been taking interest in literacy classesthrough non-formal education organized by local governmental and non-governmental agencies. Animportant aspect <strong>of</strong> this development is that most <strong>of</strong> the children and adults who are benefiting fromthe provision <strong>of</strong> mother tongue-<strong>based</strong> education belong to highly deprived ethno-linguistic groups.The Constitution <strong>of</strong> Thailand states with regard to the rights <strong>of</strong> traditional communities and theircultures as:“Persons so assembling as to be a traditional community shall havthe right to conserve orrestore their customs, local knowledge, arts or good culture <strong>of</strong> their community and <strong>of</strong> thenation and participate in the management, maintenance, preservation and exploitation <strong>of</strong>natural resources and the environment in a balanced fashion and persistently as providedby law.”(Government Gazette, 1997)[9 ]