Logos - Ardingly College

Logos - Ardingly College

Logos - Ardingly College

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

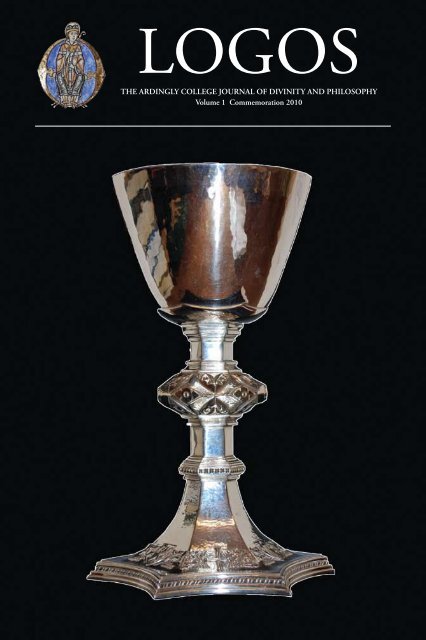

LOGOSTHE ARDINGLY COLLEGE JOURNAL OF DIVINITY AND PHILOSOPHYVolume 1 Commemoration 20101

LOGOSTHE ARDINGLY COLLEGE JOURNAL OF DIVINITY AND PHILOSOPHYVolume 1 Commemoration 2010Staff Editor:Adam KendryStudent Deputy Editor:Florence BellStudent Editor:Lucy SheehanStudent Sub-Editors:Olivia Bell and Rosie GibbensStudent Contributors:Oscar Baker, Luke Barratt, Florence Bell, Olivia Bell, Julia Casella, Amelia Elwin, Sam Elwin, RosieGibbens, John Gibson, Marcus Hunter, Mirei Ikeuchi, Robert Key, George Pinkerton, Beth Prosser, MaryReader, Lucy Sheehan, Sebastian Spence, Christopher TapsellThe <strong>Ardingly</strong> Divinity and Philosophy Department are:Mr Adam Kendry, MA (Oxon), Head of DepartmentMrs Clare Huxley, MA (Cantab) MPhil (Cantab)Mr Jamie Large, BA (Bristol)Fr David Lawrence-March, BA (Lampeter)Miss Laura White, MA (Cantab), MA (London)En arche en ho <strong>Logos</strong>…“In the beginning was the Word…”John 1: 1The Greek word <strong>Logos</strong> is difficult to translate. It is usually rendered as ‘word’ or ‘speech’ but canmean ‘concept’, ‘discourse’ or ‘reason’. It finds its way into modern English in words such asBiology and Theology - meaning literally, ‘speech about life’, and, ‘speech about God’.To the ancient philosophers the <strong>Logos</strong> was the principle of reason that underpinned the universe.They believed that the human mind was endowed with a fragment of this universal reason, andwere therefore able to understand the universal <strong>Logos</strong> .Jewish thinkers at the time of Christ used thesame word to describe the creative power of God.Saint John continues this tradition. He speaks of Christ as the Word at the beginning of the FourthGospel. He refers to the Jewish tradition that God ‘spoke’ the universe into being. He identifies thisWord with Christ.This journal contains a number of reflections by students on questions of Divinity and Philosophy.Some of the students write from a position of faith, others from a position of scepticism. Whatall of the contributions have in common is that, as with the philosophical and biblical logoi, they areacts of creation. They show <strong>Ardingly</strong> students at their most erudite, most rational and most creative.

ContentsEditorialAdam Kendry, Head of Department Page 1Introducing the Divinity and Philosophy Reading Group Page 2Parallel Lives: Grappling with the GospelsFlorence Bell Page 5In Praise of Idleness: A Reflection on Bertrand Russell’s Lecture on LethargyGeorge Pinkerton Page 6Ahead of the Times: Does God Know the Future and, if so, are we Free?Freddie Watts Page 9God and Generation X: A review of Tom Beaudoin’s ‘Virtual Faith’Rosie Gibbens Page 10Tea with the Archbishop: The ‘Faith in the World’ ConferenceBeth Prosser Page 11The Maniac: G.K. Chesterton on Atheists, Madmen, and FaeriesFlorence Bell Page 12Introducing the Theory of Knowledge Course Page 14Size Matters: Remarks on InfintudeLuke Barratt Page 15Turns of Phrase: Remarks on Language and CultureMirei Ikeuchi Page 15The Proof is in the Pudding: On the Possibility of Complete CertaintyJulia Casella Page 16Talking Heads: Trip to the Heythrop Philosophy ConferenceOlivia Bell Page 18The Undiscovered Country: Is Knowledge Discovered or Invented?Sam Elwin Page 20In a Nutshell: A Reflection on Julian of Norwich’s ‘Revelations of Divine Love’Rob Key Page 23Poetry:Sweet FreedomMary Reader Page 24EvilVivienne Lazib Page 25HaitiMarcus Hunter Page 25I am EvilLidia Nawrocka Page 26The Weight of Glory: Reading C.S. Lewis on Beauty and LoveFlorence Bell Page 27A Dutiful Life: The Relationship Between Morality and DutyKaty Reader Page 28Introducing Sophos Page 30Fully Justified? Thoughts on the Origin and Nature of EvilTom Prosser Page 32What is Philosophy? ReflectionsSebastian Spence Page 33God and Morality: Does Religion Make One Behave Better?Oscar Baker Page 33Lies, Damned Lies: The Philosophy of DeceitAnastasia Harrington and Lidia Nawrocka Page 34Machiavellian Machinations: Thinking about ‘The Prince’John Gibson and Kaan Tuncel Page 35The Sacred Made Real: Visit to the National Gallery, LondonLucy Sheehan Page 36Ecce Homo: A Reflection on ‘The Sacred Made Real’Olivia Bell Page 38

EditorialClassical Foundations: What can a Modern Philosopher Learn from Ancient Texts?Florence Bell Page 39What Beauty Teaches Us: Reflections on Theological AestheticsRosie Gibbens Page 41The Elusive Deity: Arguments For and Against the Existence of GodAmelia Elwin Page 42Is Theology a Believers Only-Enterprise? The First <strong>Ardingly</strong> Divinity Prize EssayMary Reader Page 43What is Meant by Human Flourishing? The First <strong>Ardingly</strong> Philosophy Prize EssayGeorge Pinkerton Page 45The Library of Babel: On Jorge Luis Borges’ Dark Philosophical FantasyFlorence Bell Page 47Positive Thinking: Evaluating a Problem of Medieval God-TalkChris Tapsell Page 48To the Slaughter: A Philosophical Analysis of ‘Slaughterhouse Five’Julia Casella Page 49Discussing Descartes: A Firseide Conversation on Meditations 1 and 2’Chris Tapsell and Florence Bell Page 51The Last Word Page 53Divinity and Philosophy are at the heart of the Woodard tradition. We are called to be a theological community,that is, we speak about God. We do not all believe, and those that do, do not always agree - but that we talk is partof our distinctive character.Our discourse at <strong>Ardingly</strong> takes a variety of forms. All of our students study Divinity at in the Shell year: aprogramme that involves an explanation of the three great Abrahamic faiths. Many students opt to continue theirstudies onto GCSE. Those that do not follow a programme in Philosophy that runs in the Remove year and is knownas “Eudaemonia” – a name that derives from the philosopher Aristotle’s term for human flourishing. Academicstudy flourishes in the Sixth Form also, with healthy numbers studying either the Divinity A-Level course or thePhilosophy IB programme. Finally, all of those students following the International Baccalaureate diploma take the‘Theory of Knowledge’ course (on which more later). These pages contain examples of work from all these coursesand represent the whole breadth of ages of students at the <strong>College</strong>.Beyond the classroom, the Department runs two societies, one for the Middle School, the other a Sixth FormReading Group. Much of the work of these features throughout this Journal, including reports on a number oftrips undertaken. It was in this Sixth Form Reading Group that this Journal had its origins. The students suggestedcollecting a number of reflections on their work as the year went on and this provided the kernel for producing amagazine with a broader remit. To this we added some of the best pieces of work produced by students within theDepartment over the last twelve months. <strong>Logos</strong> is the result.I am tremendously indebted to all the students whose hard work is included in these pages. Many studentscontributed pieces and it was not possible to include them all. I am particularly grateful for my Student EditorialCommittee who worked long and hard to produce this. <strong>Logos</strong> belongs to them. This is the first word – hopefully itwill not be the last.Adam KendryHead of Divinity and Philosophy<strong>Ardingly</strong> <strong>College</strong>1

Faith Seeking UnderstandingThe Divinity and Philosophy Reading Group (DPRG)was founded this year with the aim of supportingthose students who are considering applying to readeither subject at University. Its broader aim, however,was to encourage the students to engage with primarytexts in these disciplines and to allow them to developthe reading and analytical skills that would form anessential part of their University experience. Restrictedto Sixth Formers, the group has proved to be a hugesuccess, with fifteen to twenty regular members meetingon Monday nights fortnightly.Texts are circulated in advance of the meetings andstudents meet to tease out and debate the interpretationof the reading. There is an attempt to vary the texts,and we have read essays, short stories, articles, academicpapers and excerpts from longer works. We have lookedat texts by Plato written two and a half thousand yearsago as well as an Oxford paper published in the last fiveyears. Many of the students who have joined the DPRGhave gone on to apply to read Divinity or Philosophy.Some have remained simply to broaden their studies.The DPRG has also undertaken a number of trips andevents outside of the classroom including a trip to TheSacred Made Real exhibition at The National Galleryand holding a hugely-popular garden party. Furthertrips are planned for next year.There follow a number of reflections on texts fromthe DPRG. Each student who has submitted a piecevolunteered to do so on the basis that something in thetext had particularly resonated with them.Mr Kendry3

The First Annual Divinityand Philosophy Reading GroupGarden Party Wednesday 26th May 2010Parallel Lives:Grappling with the GospelsFLORENCE BELL (T)Lower Sixth IB Philosophy StudentBeside Christ Himself, the Bible forms the foundationof Christianity. It allows for the holding of theteachings and expectations of Christians and thusprovides the basis for leading a good Christian life. Inthis the Gospels, which provide an account of Jesus andhis teachings, are invaluable, allowing as they do for anexploration of the truth of Christianity. Whilst the three‘synoptic’ Gospels, Matthew, Mark and Luke seem verymuch to coincide in terms of the specific stories theytell, often they place different interpretations on theadvice of Jesus and as such each gospel tends to displayaspects of Christianity in different ways, allowing forthe personal perspectives of the individuals involved inreading them to come to the foreground. The FourthGospel, the canonical Gospel of John, is very differentin style, in the way that it considers more carefully theaspect of the two natures of Jesus - human and divine -than it does the story of His life.It is believed by most theologians that Mark is theprimary literary source for the other gospels and thatthe other two remaining synoptic gospels spring fromit, with a combination of Mark and other externalsources as guidance. Clearly there are some strongparallels therefore – although there are at the sametime, a large number of small conflictions. This is bestexemplified through looking at particular instancesthroughout the gospels. For instance, all three synopticgospels deal with the issue of marriage and divorce: inMark 10:11-12, it is written “Whoever divorces hiswife and marries another, commits adultery against her;and if she divorces her husband and marries another,she commits adultery.” However, Matthew, in Chapter9 claims that Jesus’ view was that “whoever divorceshis wife, except for unchastity, and marries another,commits adultery.” In this way there is a definite shift inprinciples and in this way it is an example of the abilityof the reader of the scriptures to be able to interpretthem in any way that makes sense to them.Furthermore, there have been controversies regardingthe ending of Mark, as to whether Mark 16:9–20,describing some of the disciples’ encounters withthe resurrected Jesus was added after the originalautograph. This appears very much to be the case asit is written in a very different style to the rest of thegospel, using vocabulary that is not considered to beusual for him, which is rarely replicated in the rest ofhis gospel. However, despite the fact that many criticswould therefore use this as an excuse to discount theseparticular verses and only consider the rest of the text,it does appear to cause us to beg the question as to howwe are to decide whether any of the gospels or indeedany of the scriptures are “true”. However, regardless ofthe objective truth within them, they provide a valuableinsight into Christian thought and furthermore, they areinvaluable in providing for Christians a way of living,furnished with the morals and teachings of Jesus Christ- the most important of which is spread throughout thegospels, regardless of author “You must love the Lordyour God with all your heart, all your soul, all yourstrength…and love your neighbour as yourself”.4 5

In Praise of Idleness: A Reflection onBertrand Russell’s Lecture on LethargyGEORGE PINKERTON (WB)Upper Sixth A-Level Divinity StudentIn Praise of Idleness is a revelation. To me, it expressedsentiments I have often felt, namely that if everyoneworked only half the hours they do now, the economywould remain the same, but we would all have twicethe leisure time we now have. Russell explains thehectic pace of a modern life centred on work as aphenomenon that was a relic of ancient injustices: inprimitive communities, families worked as hard asthey could and were only able to produce (or catch,grow, fell, hunt, gather, &c.) as much as they and theirimmediate relations required, with little or no surplus.What surplus they produced ‘was appropriated bywarriors and priests’ who produced nothing themselvesbut death, fear, and superstition. He points out that intimes of shortage, the army and clergy took the foodthey wanted or needed regardless of the peasant’s needs,and so the peasants died. This, he reasoned, continuedinto our own day, but on very flawed principles.Eventually, it was not necessary to beat or berate tithesand taxes from the workers because they had come toaccept that, not only did these fatuous parasites deservewhat they stole, by that it was actually good to workhard, denying oneself to feed and supply a class ofindividuals society did not need. With this, he explainsto the contemptible self-deprecation of Christianity,and the exploitative work-ethic of Protestantism andJudaism. This sort of social selection might well havecontinued through the mediæval eras, but ought tohave ended with the Industrial Revolution, whichallowed man, collectively, to produce a surplus many,many times more than the sum of what individualscould either produce or consume. It did not however,and the feudal work ethic was transplanted to theindustrial society. In this Russell declares his sympathyfor socialism, but also for liberalism; he states thatthe agricultural-feudal system came to an end in theBolshevik Revolution in Russia, in the AmericanRevolution in the Northern U.S., and in the CivilWar in the Southern. In all these societies, ‘in theEast’, and in Britain, the ethic imposed on the villainsremained sealed on the minds of the urban artisans andlabourers: that it their duty to ‘live in the interests oftheir masters’. Concluding that increased leisure timeis not only beneficial but essential to properly civilizedhumanity, that great intellectual advances were madein history only when there was adequate leisure time –the ancient Greeks and Romans delegated their workto masses of slaves, and it was these battalions thatallowed the important civic figures to get some seriousthinking done.While praising the end – the otium cum dignitæ ofthe Roman gentry – Russell criticizes the means bywhich they achieved it: ‘their idleness is only renderedpossible by the industry of others’. Russell does notavoid unfavourable comparison between the modernidle rich – himself an earl of unimpeachable lineage –and the real mediæval earls and dukes, who subsistedsolely on the taxes and extortion of their serfs.Instead, arguing from the unusual but none the lesssolid ground that labour was bad, leisure was good,that unemployment was excessive leisure, and thattotal idleness was equally bad, Russell deduces thateveryone should do some work, and by that meanseverything necessary would still get done and everyonewould have more time to pursue more satisfyinggame. Industrialization alone allowed for this. Whilethe Athenian oligarchs were able to philosophizeat length because their work was done for them bythe less entitled, if the work was divided justly therewould be no time for examining life at all. The changecame with machines, and the division of labour. Itis no longer necessary to work from dawn till duskbecause machines can now do much of the labour forus. But the preservation of the unhappy myth thatStakhanovite excretions are virtuous led and continuesto propagate unemployment everywhere in themechanized world. Essentially, the eight- or ten-hourworker is hoarding employment.It would benefit all, I think, if the working hours of theentire workforce were reduced: not only would those inemployment’s opportunities for recreation increase, butthose people now out of work would find their labourin greater demand. For instance, if we assume everyonenow employed, some 28,830,000, works an eight-hourday, five days a week – in other words, the forty hourweek – we can calculate that there is a demand for230,640,000 hours of work per day. But this leavessome 2,510,000 out of a job. So if those hours weredistributed evenly over the workforce – the currentemployed plus the unemployed – full employment,with an apparently paradoxical increase in free time,could be achieved if everyone only worked seven hoursand twelve minutes a day – just less than a thirty-sixhourweek. This is a much less radical decrease thanthat which Russell advocated – a four-hour day insteadof eight-hour – and of course it assumes a whole cohortof things concerning the versatility of labourers and soon, and the obvious point that until recently Francemandated a thirty-five-hour week and there remainedunemployment, but the point stands that fairer work isless work and more leisure.The masses’ leisure time was to be spent in all sortsof wholesome activities. The modern worker, asmuch in our own as in Russell’s day, is incapable,after a long day or week, of anything more thanpassive entertainment – cinema, the internet, and thetelevision in his limited free time. But a workforceuniformly liberated from all but the minimum ofnecessary toil, will be free to enlighten themselves withsport, science, art, and society. A somewhat headyconclusion lightened with the hue of pacifism andshaded with unreasonable optimism follows, but thewhole piece is somewhat tongue-in-cheek anyhow, forall its serious and practical points. In Praise of Idlenessis a thoroughly logical evaluation of the ills of modernsociety and how they might be solved, and it applies aswell today as in 1932. In fact, it is a real wonder whyno attempt has been made by any country to makethese suggestions a reality.6 7

Ahead of the Times: Does God Knowthe Future and, if so, are we Free?FREDDIE WATTS (WB)Upper Sixth A-Level Divinity StudentThis question is highly complex and there are manypeople who have different opinions and ideas on it.One deciding factor on your opinion is the perceptionyou have or God, whether He is timeless or everlasting.This in itself will be a determining factor on whetheryou believe you are free or not.There are many people who hold the view that God istimeless, outside of time and space. This view is heldstrongly by many traditional Christian theologianssuch as Augustine, Boethius and Aquinas. The idea thatGod is timeless means that time does not apply to him.Therefore, our present, past and future are all presentto him because past or future tenses are meaninglessto him. Boethius explains this by describing hisknowledge of life as ‘the whole simultaneous andcomplete possession of external life all at once’.Therefore, according to Boethius, God does know ourfuture. Because for Him it is present, but we are free.For Boethius, God knows what we are freely going tochoose at his present because he is omniscient. This isa very complex idea, this is why Augustine attempts tosimplify it in an analogy. The analogy is God standingon a mountain looking down onto a road. On this longroad he sees the beginning and the end. He can see usat the beginning, the middle and the end all at once.This is the analogy of God seeing our future, presentand past simultaneously.However, a different view on God’s knowledge of ourfuture is that if God is outside of time, that meanshe is outside of change, because without time changecan’t occur. Therefore if God knows our future, hisknowledge of our future is also unchanging, thereforeour future is fixed; we have no free will.However, there is another view that can be takenon God that is taken by the majority of religioustheologians. This is that God is everlasting, but withintime. This view is one that is close to the Bible’sdescription of God, that He is everlasting and eternalbut in time. Augustine also provided an analogy of theeverlasting God. Imagine time extended in both wayswithout end; this is the idea of an everlasting God.This means God does know our future, because he is intime, which means that our future is fixed therefore ourlives and choices are not free. Because for God to knowour future he must know our choices for them to leadto the future he knows, we cannot be free.However, I take a slightly different look on this view ofan everlasting God. If God is within time and he knowsour future, God’s knowledge must also be in time.Therefore, it is subject to change. Thus our future is notfixed because every choice we make can change God’sknowledge of our future.Peter Vardy took his stance on an everlasting God thatif he is inside time, he can’t have created it. If God hadbeen within time then the problem would have arisenthat there was something (time) outside of God thathe had not created, therefore God’s omnipotence isquestioned. If God is not omnipotent he may not beomniscient, which means he may not know our future,then our future is not fixed and we are free to forge ourown destiny.God’s knowledge of our future is a topic RichardSwinburne had a strong opinion on. He believedthat if God is outside of time, then he cannot applyhis knowledge and actions in our world which is soseparate from him. If we say that P brings about X,we can sensibly ask when does he bring it about?God’s actions cannot be applied to time, thereforehis knowledge can’t be either. Therefore, he cannotknow our future because he can’t use his knowledgein our world. Ergo our futures are blank for us tofreely choose.Brian Davies rejects Swinburne’s theory strongly andsays that God’s knowledge and actions can be relatedto our world. Just because of the constrains of theEnglish language which are temporal and therefore can’tbe related to God, this does not mean he cannot haveknowledge of our world. Therefore, he does know ourfuture, he can very well act in our world which meanshe may be able to influence it. Therefore we may bedetermined and we may be predestined.Lastly, for us to know or believe in God knowing ourfuture and therefore our free will, we must examinewhether God is omnipotent. For this there are certainparadoxes that question this – can God create a stoneso heavy that he can’t lift it? One view would be thatGod can do anything possible, therefore their logicalcontradictions are meaningless because they are notpossible. A Cartesian approach is God can do anything.Therefore, God’s omnipotence is possible and he mayknow our future, therefore we are not free to choose it.In conclusion, the question “does God know ourfuture, and if so are we free?” is one I believe the answerto is that God knows every possible future for us.However, it is our free choice that chooses which futureto take and live.8 9

God and Generation X: A Reviewof Tom Beaudoin’s ‘Virtual Faith’ROSIE GIBBENS (T)Lower Sixth A-Level Divinity StudentTom Beaudoin is Professor of Theology in the GraduateSchool of Religion at Fordham University in NewYork City. His style of theology focuses intensivelyon questions of practice, especially the relationshipbetween “spiritual” and “secular” practices. Hisbooks include Witness to Dispossession: The Vocationof a Postmodern Theologian (Orbis, 2008) ConsumingFaith: Integrating Who We Are With What We Buy(Rowman and Littlefield, 2003); and perhaps mostfamously Virtual Faith: The Irreverent Spiritual Quest ofGeneration X (Simon and Schuster/Jossey-Bass, 1998).revealing something about themselves’ and similarly,Beaudoin believes that the ironies and criticism in ourunderstanding of religion through the world around us,is an important way to discover our own views (whichbecome more balanced through these criticisms).Hesees the scandalous depictions of institutional religionand the juxtaposition of the sacred and profane, whichcan be seen everywhere in our culture (for example,the uses of crucifixes as fashion statements), as part of apublic discussion of open spirituality.Beaudoin ends the book by suggesting that GenerationX’s irreverence should be seen as a form of spiritualityin itself and that this ‘lived theology of a generation canboth teach religious institutions and learn from them’.Virtual Faith was a fascinating read and I wouldrecommend it to anyone who is struggling to see therelevance of religion in modern life. I thought thatsome of Beaudoin’s interpretations were slightly far –fetched such as his interpretation that body piercingare representative of the generations suffering andtheir search for spirituality. However, most of the bookwas excellent. I found that Beaudoin’s theories wereaccessible and refreshing and the book certainly mademe re – evaluate the meaning in this often seeminglyshallow culture. As such, it provided me with insightinto the struggle of society today and consequently,his interpretation of the natural spirituality of theindividual was poignant in its exploration of thesociology of religion, since the start of time andforward, into the future.Tea with the Archbishop: The ‘Faithin the World’ ConferenceVirtual Faith focuses on the spirituality of the youthgeneration of our society – the so-called ‘GenerationX’. Beaudoin suggests that one can gain a religious orspiritual understanding through the scepticism andirreverence of modern youth culture through exploringthe religious imagery in various incarnations of popculture (such as music video and fashion). He cleverlyinverts the apparent irreligious attitude of this culture asa way to reveal important criticisms which can lead to adeeper understanding of religiosity for the generation.For example Beaudoin claims that many popularmusic videos contain important religious messagesand criticisms which should most definitely be takenseriously by religious institutions if they want tounderstand why many youth reject organized religion.One of these interpretations uses to the music videofor Black Hole Sun (a song by the band Soundgarden)which Beaudoin claims ‘subtly pit Jesus against theinstitution’ through the apparent symbolism. Thistakes place through a young lamb being tied to a fenceand fed a bottle by a Christian minister. This ‘craftilyconstructed sequence’ can be interpreted as a criticism ofthe taming of Christ’s message, as the ‘Lamb of God’(John 1:29) by the institutional religious teachers andpractices. Alternatively, the lamb could be interpretedas symbolizing those people who blindly follow religionor our ‘force fed’ like the lamb in the video, implicitlyreferencing religious followers as sheep (c.f. “the goodShepherd lays down his life for his sheep’ John 10:11).Beaudoin interprets anti – religious pop culture, suchas in music videos, as a basis for constructive criticismand therefore a closer understanding of religion. Hesees this criticism and scepticism as a ‘key step inGeneration X theology’. By this, Beaudoin means thatthis criticism is important in discovering a deeper andmore genuine approach to Christian theology. Hesuggests that availability and importance of pop cultureand the internet mean that we can more widely discussand interpret our religious views (and break awayfrom the moulds of institutions or from our parents).Beaudoin uses the use of irony as an example for away to reach this deeper understanding of spirituality.Kierkegard believed that ‘irony lures its readers intoBETH PROSSER (T)Lower Sixth A-Level Divinity StudentOn Thursday 4th February 2010, myself and four otherAS Theologians were privileged enough to attend aconference held by the Archbishop of Canterbury atChurch House in London. The conference, entitled‘What does faith mean for society today?’ featuredshort lectures from Revd Richard Coles (priest andbroadcaster) Professor Elaine Graham (Lecturer at theUniversity of Chester) and Dr Rowan Williams, theArchbishop of Canterbury.Revd Richard Coles began the afternoon with a talklabelled ‘Thinking Differently.’ In a rapid and wellput presentation of the problems of global poverty,discrimination and inequality, and the role of themedia in shaping what people think about faith, hechallenged the audience to rethink what it means toshare responsibility in society.Second to the podium was Professor Elaine Grahamwho looked ahead at the next 10 years in her lecture,‘2020 Vision.’ Accompanied with a PowerPoint sheencouraged us to think about which questions facingsociety need us to understand faith so that we can findanswers that we can share. She argued that increasingdiversity in religious practice, combined with theglobalisation not just of business but of problems likeclimate change, means we need to find new ways ofliving with difference in our communities.Under the title ‘Taking Responsibility’ Dr RowanWilliams paid tribute to the role of faith in holdingon to a full view of what it means to be human.Referring back to history of the 20th Century, he10 11

described how he has been influenced by the writingsof Etty Hillesum, a young Jewish woman living inAmsterdam at the time of the Nazi invasion who wassurprised to find how her faith became important toher as the world around her darkened. That experienceleft her with the view that somebody needed “to takeresponsibility for God”, to show by their own life andactions that evil did not have the last word. This is themessage that we were encouraged to take note of andput into practice.After the lectures had been concluded, we were thenencouraged to pose questions to the panel beforeheading back to small conference rooms where we weregiven a chance to look at the work of fellow students.In the week preceding the event, a poster was preparedby our school on a topic of our choice to do with howfaith influences society today. Our poster, exploringthe intricacies of Abortion and Euthanasia Laws andtheir relationship with religious views, was displayedwith posters from 60 other schools from the South ofEngland. As the day came to an end, we were luckyenough to meet the Archbishop of Canterbury inperson and discuss the ideas we expressed in our posterwith him. This was certainly a fulfilling way to concludean academically stimulating day.The Maniac: G.K. Chesterton onAtheists, Madmen, and FaeriesFLORENCE BELL (T)Lower Sixth IB Philosophy StudentIt is clear from reading Chesterton’s The Maniac thathis interpretation of society is radically different frommost traditional thinking. From the very start of thispiece of writing there are clear demonstrations to this:his very first line is “Thoroughly worldly people neverunderstand even the world; they rely altogether on afew cynical maxims which are not true.” Whilst a lotof what he continues to say does not necessarily makesense within the context of the real world, this phrase isparticularly potent in that it allows for the explorationand even the condemnation of those things that wejust take to be so, because that is how they have alwaysseemed. In this, Chesterton draws our attention tothe way that things differ in the way that they seemto be from the way that they actually are and in doingso, attacks our personal interpretations of reality,challenging the ways in which we perceive the world.This way of challenging us is one that is very successfulin commanding the attention of the reader, encouragingus to reform our interpretations of the world. However,what is especially brilliant is that he demonstrates theway that our ordinariness makes us see the world ina way that is exciting, as Chesterton says “In short,oddities only strike ordinary people. Oddities do notstrike odd people.” Furthermore, when we considerthose who we would expect to be mad, we wouldprimarily argue that it is likely to be those involvedin artistic pursuits as they are the ones most closelylinked to the dangerously bohemian and their skill ofimagination considered to be on a par with lunacy.Yet Chesterton points out that in actual fact, historywould tend to prove otherwise: “Exactly what doesbreed insanity is reason.” It is only those who are overlyaffected by reason that tend towards insanity, becauseit is only the disruption of a predisposed pattern thatcan cause true disorder. In pointing out this discrepancyin our natural thought paths, he indicates how easy itoften is to be distracted by the semblance of somethingand not look beyond its outward appearance to discoverthe truth of the matter within it.The madman is also afflicted by this condition, butto a greater degree. Furthermore, he creates a sphereof existence, within which all that he believes makessense. As Chesterton argues: “…if a man says that he isJesus Christ, it is no answer to tell him that the worlddenies his divinity; for the world denied Christ’s.”Any argument you will try to find that disproves hisargument can in fact be twisted and made to fit withinhis particular sphere. Thus Chesterton feels it is bestnot to attempt to argue specifically, but merely tobroaden the madman’s mind, bringing him out from self-contemplation to contemplation of the greater things inlife. Clearly this is the most successful way of dealing with the problem as any other – indeed, even when men aresane, it is evident to some extent at least that Chesterton believes the only way to true mental health is to introduceconcepts which cannot necessarily be explained within the real world: “As long as you have mystery you have health;when you destroy mystery you create morbidity.”12 13

How do we Know?Size Matters:Remarks onInfinitudeTurns of Phrase:Remarks onLanguage andCulture<strong>Ardingly</strong> is unusual in that it offers its Sixth Formstudents the opportunity either to study A Levels orto follow the International Baccalaureate (IB). Part ofthe core provision for the IB diploma is for studentsto take a course in the Theory of Knowledge (TOK).TOK requires students to reflect on the question ‘Howdo I know?’. It challenges them to analyse both theways in which they gain knowledge through perception,emotion, reason and language and asks them tocritically consider the different areas of knowledge andthe strengths and weaknesses of each.This clearly allows the students the opportunity tothink in a far more incisive way about the possibilityof truth and as such gives them the chance to explorethe relativity contained within any knowledge based ontheir experiences of the world. This topic is thereforeone that draws on individualistic interpretations of theworld and of reality and thus the students are able toexplore their own personal opinions, founded always onthe question of knowledge.For some students, this allows them an exceptionalopportunity to consider the curious nature ofeducation, where so much is taken for granted, basedon what has been shown through the empirical sciences.As such, this is an incredible area for growth, somethingthat is considered to be an essential part of the studyof a student of the Baccalaureate. They are forced toconsider the nature of reality, through consulting theways in which we claim to know and through linkingthe ways in which we claim we can know things:through History, Ethics, Mathematics, the Arts and somuch more.As part of their studies we ask students to keep ajournal in which they make regular entries whenevera knowledge issue occurs to them. Not only does thisallow them to explore with imagination any topicthat strikes them as particularly relevant or importantwithin their day-to-day lives, but it opens the door toa process of creative writing teamed with introspectiveconsideration, through exploring the topic from apoint of view that may either be entirely objective, orcombine elements of subjectivity as well. Althoughthe journal entries themselves are not marked, theycontribute massively to the student’s ability to framea question of the topic of knowledge and providean argument for it. This therefore creates a resourcefrom which they are able to pull out specific tools toallow them to complete other parts of the TOK – apresentation, on a subject of the candidate’s choice, anda 1500 word essay, the title of which is chosen by thestudent from a database of 10 or more each year. Whilsttherefore the journal entries therefore do not have aspecific relevance in terms of points, they are crucialto allow the student to develop both their thinkingand their writing style, to adapt to the TOK spectrum.These entries may be written from the perspective ofa TOK class or any of their subjects and the resultsare often wide-ranging in topic, varied in style andperceptive in quality. A number of the best journalentries from this year’s lower sixth students appear inthese pages.Mr KendryLUKE BARRATT (H)Lower Sixth ToK StudentToday I was thinking about the issues raised in the lessonabout there being such thing as a big infinity and a smallinfinity. It was something that I never really thoughtabout but it somehow made immediate sense that thereare different infinities. I like to think that infinity isthe same value, but it simply increases at different rateswhich makes one going faster than the other cause abigger infinity and a smaller infinity. The one thing,however, which I don’t agree with about the infinityreasoning, or at least something that annoys me, is that itwas to at one point end. I mean, we speak about certainthings which are infinite such as numbers, but how canwe say confidently that time is infinite? If, as many othersas well as I believe, the universe was started by the BigBang theory almost instantly, then wouldn’t it make sensethat it could disappear just as quickly? Thus ending time?As I thought about this further I established that at leastin my life everything has a peak and then falls and ends.It’s the typical “what goes up must come down” theory.So if in life everything ends or dies at one point, thenwhy should the universe be any different?The other thing that this led me on to think about wasGod and how people believe in him. I know this soundsclichéd and of course it’s one of the most contested topicsin human history, however, today I looked at it from adifferent perspective. I had always looked at God andheaven as being in the afterlife and therefore a long wayin the future. However, today, for whatever reason, Idecided to look backwards. If, as suggested, humans havebeen around for thousands of years then surely as I ama descendent from them, that many of my predecessorshave died. Therefore because life has been around so long,how do we know the world in which we live in is our firstlife? And therefore, how do we know if where we are atthe moment is not heaven? This new idea gave me a newperspective and made me believe, although only slightly,that it is not probable that there can be an afterlife as I donot know whether this is in fact my first life.MIREI IKEUCHI (T)Lower Sixth ToK StudentLanguage, the means by which people connect withthe thought processes of others, differs from regionto region within countries. When I learnt to speakEnglish, I do not think that I was really aware that I waslearning a language. I was fully excited about findingdifferences between different languages. I rememberthat when I looked up one word in English, I alwaysgot several Japanese translations, all of which are totallydifferent. So, I couldn’t always make a choice. But now,I realise that some words and phrases can never exist inEnglish. It might be in the dictionary, but it wouldn’tbe the right meaning or feeling so only native speakersrecognise your feeling when you say certain words.As a result, I think that by speaking another language,you can broaden your knowledge and ability to feelthings. For example, I use three different languageswhen I talk to my mum and I use different languageswhen I want to describe certain feelings. Even thoughI have never studied Korean literature before, Ican feel what an author means because we have asimilar culture. Similarly, even when you understanda language, it doesn’t mean necessarily that youunderstand their way of thinking.Language is a dramatic gift bequeathed to humans. Itcan be wonderfully inclusive, enveloping its speakersin a glow of belonging and common perceptions.Unfortunately, at the same time language can also bea source of exclusion, misunderstanding and conflict.For me, language is just like a kind of telepathybetween two people, who have got the same culture andexperience; its amazing that how a short word describesour complex feeling.14 15

The Proof is in the Pudding: Onthe Possibility of Complete CertaintyJULIA CASELLA (T)Lower Sixth IB ToK StudentCharles Darwin once wrote, “Mathematics seems toendow one with something like a new sense”. He iscorrect: mathematics is like a new sense because it doesnot rely on any other ones. Our six senses depend onperception. Mathematics however exists outside therealm of perception and therefore is free of the flawsassociated with perception as a way of knowing. In away, mathematics can be considered the perfect “sense”.The knowledge that one gains from mathematics is oftenconsidered the most pure form of knowledge due tothe concept of absolute proofs. When things are provenmathematically, they are then considered true forever.While mathematics provides a universal certainty that isdifficult to refute, I believe that other areas of knowledgecan provide a similar, subjective, certainty.Mathematical certainty is a type of certainty that existsin no other discipline known to man. When somethingis proven mathematically to be true, it is then true untilthe end of time. This search for absolute knowledge iswhat drives mathematicians to slave after proofs. Oneof the most famous theorems was the theorem putforth by Fermat in the seventeenth century and finallysolved in 1993 by Andrew Wiles. This importance ofsolving a proof is noted by John Coates when he said“In mathematical terms the final proof is the equivalentof splitting the atom or finding the structure of DNA.A proof of Fermat is a great intellectual triumph andone shouldn’t lose sight of that the fact that it hasrevolutionized number theory in one fell swoop. Forme the charm and beauty of Andrew’s work has beena tremendous step for number theory.” While heis correct in asserting that it is a “ great intellectualtriumph”, Coates is not pointing out the fact thatsolving a proof could perhaps be better than findingthe structure of DNA, or any other scientific claims.Science relies on evidence, while mathematics is builton infallible logic. Mathematics is based on a priorireasoning, a type of knowledge thatcan be known to be true independent of experience.Even Descartes, who enjoyed questioning absolutelyeverything, said “ to speak freely, I am convincedthat mathematics is a more powerful instrument ofknowledge than any other that has been bequeathed tous by human agency, as being the source of all others”.While others feel that math is created, I believe thatit is discovered. It manifests itself in our daily lives,yet it is not something that we try to mould. Insteadis something that we try to untangle and discover.Mathematicians achieve a truth, which is beyond thefallibility of human judgment.When it comes to art, the way in which one assertscertainty is completely subjective to the viewer. Youcan be certain that a piece of art is beautiful, because inthe situation of art, it really only matters if you thinkit is beautiful. The certainty that one feels a piece ofart embodies, whether that be the certainty that thepiece is beautiful, ugly, representing hate or love, variesfrom each person. It differs from math in the sense thata group of people do not always agree on the beautyof a piece of art, however a group of people can noteven begin to attempt to disagree about simple mathproblems. I personally do not like Duchamp’s TheBridge Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors. In this statementI am certain. Clearly other people are certain that thispiece of art is beautiful, or moving, or ugly, yet theircertainty does not affect the certainty that I feel. A fewyears ago I went to the Uffizi in Florence and stood infront of one of my favorite pieces of art ever: The Birthof Venus. For me, the certainty that I feel towards thispiece of art, is almost on the same level of certainty thatI have towards knowing the answer to a math problem.However, they differ in that while I am sure of my ownknowledge regarding both math and art, the certaintythat I have towards art is entirely my own. I am certainthat The Birth of Venus is amazingly beautiful and Iam certain that when you divide a number by zero theanswer is zero. However these are two different typesof certainty: a certainty that is internal and a certaintythat is external. This certainty that we feel towards artis subject to change. As our perception and emotionschange so does our certainty concerning certain aspectsof our lives, including art. Because the certainty thatone feels about art is dependent on the certaintythat one gets from the other ways of knowing, it isconstantly subject to change. Therefore it appears thatone should never feel certain. However I think thatdespite this flaw in the certainty we gain from otherareas of knowing that are not mathematics, we shouldalso employ reason, the foundation of mathematics, andnote that life would be unbearable if it was lived witha constant sense of not knowing. Therefore one shouldnever feel as if they know everything, and likewise: as ifthey know nothing.While the certainty that one gains from art is subjectiveand the certainty that one gains from math is absolute,one wonders if there are any uncertainties in math orcertainties in art. Art does have an aspect of certaintyin it, when it relies on mathematics. The golden ratiois a number often encountered when taking the ratiosof distances in simple geometric figures such as thepentagon, pentagram, decagon and dodecahedron .Paintings such as the Mona Lisa, which is considereda masterpiece, follows the golden ratio perfectly. Theartistic value in seashells is noted in the fact that theyare commonly painted and photographed, and theytoo follow the golden ratio. Just as Leonardo da Vincifollowed the golden ratio to create beautiful art, natureseems to have its own art pieces that follow the samerule. Therefore some things are known as beautiful inthe artistic, subjective, way of knowing and also in themathematical, absolute, way of knowing. Math alsohas its own set of inconsistencies. Math is based onaxioms, that have never be proven and therefore arejust accepted as true. Therefore the most valid proofis based on things that cannot be proven. Furthermore, there are things that should be able to be solvedmathematically, but cannot be. This summer I waswatched my grandfather play solitaire and I startedwondering what the chances of winning solitaire were.Knowing that this was a mathematical question, Icalled my father, a lover of math, who got his mastersin engineering. He said he did not know and had tothink about it. I looked it up and found out that “ thetheoretical odds of winning a standard game of nonthoughtfulKlondike are currently unknown. It hasbeen said that the inability of theoreticians to calculatethese odds is ‘ one of the embarrassment of appliedmathematics’”. This creates a problem, not only inthe sense that something can not be solved using themost “absolute way of knowing” but in the sense thatif mathematics is no longer completely valid because itfalls short of explaining certain things, are the thingsthat depend on it no longer valid as well? Are seashellssuddenly ugly? Were they only beautiful before becausethey depended on mathematics? Perhaps we are betteroff using emotion, perception and language in anattempt to decipher the world around us. However thisalso draws on the fact that despite the flaws imbeddedin the use of perception, language and emotion, wehave not completely refuted them as ways of knowing.Therefore one cannot discard math based on the factthat it does fail to answer certain questions. Or isit because math seems so perfect, that when it fallsthrough, it is seen as a disgrace? Perhaps we don’tdepend on the other ways of knowing in the way wedepend on math. Perception fails us every time weare tricked by an optical illusion. Language fails uswhen we find it difficult to understand other people’smentalities and culture due to the radically differentone we grew up in. Emotion fails us when we fall inlove with someone we shouldn’t. However math is notsupposed to fail us. 2+2 is 4, no matter where on theworld we are, or who we are in love with. It provides16 17

us with a consistency that we rarely see in the otherareas of our life. So if it fails, it seems that it should becompletely disregarded despite the fact that the otherways of knowing fail us daily and we still use them.Mathematics is free from the ever so obviously flawsthat accompany the other ways of knowing. But inall of its perfect glory, it still manages to fall shortat times. But since it is more valid than the otherways of knowing, and the ways of knowing are reallyjust relative to each other, mathematics should thenautomatically be considered the most valid. If a groupof students take a test and the highest score is a 9 outof 10, teachers will sometimes “ scale” the test andgive each of the students an extra point so the topscorer gets a perfect score. So when it comes to theways of knowing, while math is not always reliable,perhaps we should look at it on a scale. It isn’t perfect,but it is the best thing we have to reaching absolutecertainty and perfection. And while math and artseem to be radically different in their assertion of anytype of absolute certainty, it is important to note thatboth of them must employ another way of knowingin order to be truly brilliant. Despite what many highschool students may think, math is not a dispassionatesubject. I can do a math problem without emotion,but to do truly great math, and to discover truly greatthings, requires a certain level of love and passion forthe subject. Vincent Van Gogh said that he wanted hispaintings to touch those who look at them. AndrewWiles would have not have spent eight years solvingFermat’s Last Theorem if he hated math. If math andart drew no emotion from the person working onit, and those who study and admire it, they wouldjust be dispassionate areas of knowledge. However,dispassionate areas of knowledge are never sought after,and therefore their certainty is never questioned.Talking Heads: Trip to the HeythropPhilosophy ConferenceOLIVIA BELL (T)Lower Sixth IB Philosophy StudentOn 26th February, all Lower Sixth A level theologians andIB philosophers escaped the college for a day to attend aconference at the famous Heythrop <strong>College</strong>. The day wassplit into two halves, each comprising of two lectures. Thefirst, by Stephen Law, was an interesting and insightfuldebate on whether the universe was fine-tuned by God.A good chance for some revision, we were reminded ofthe ‘New Teleological Argument’ consisting of WilliamPaley’s ‘watchmaker argument’ which argues there mustbe a designer as the world is so complicated, and StephenLaw brought us through the ‘irreducible complexityargument’, one that basically reveals that as the universeis very complicated, with the right levels of all theelements needed, this simply cannot be coincidence.Quoting Douglas Adams, he reminded us of the analogyof a puddle – like the puddle is formed in a certain waybecause of the shape of the dip in the road, so we too (asthe water) are shaped by the world, and the world is notshaped by us. He then moved on to criticise a Darwinianapproach, arguing that biological complexes such as theflagellum on bacteria are so complex that they cannothave evolved gradually.After a short spout of questions, where Jack Donoghueseemed intent on grilling Stephen Law on every singlepoint made in his argument – and winning – the nextlecturer, Nigel Warburton, stepped up to the podium.His lecture, more ethically based, was on the conceptof utilitarianism. Giving a brief overview of JeremyBentham’s concept of morality being based aroundthe consequences, and not the actual action, he ledus through the Hedonic Calculus; he expanded onthe basic idea of maximising pleasure and minimisingpain as being the only way to view morality. Afterestablishing these roots of utilitarianism, he elaboratedon how exactly we could heighten pleasure, primarilyby intensity, duration, and fecundity, and then led usinto Mill’s criticisms of Bentham’s ideology, in thatnot all pleasures count as the same, and that there aretherefore ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ pleasures, using examplessuch as that of assisted suicide. Taking his words toheart, we decided that the best and most pleasurablething to do would be to go and get a spot of lunch.After the break, Michael Lacewing gave us an informativeinsight on the concept of religious experience. This beinga more controversial subject, Jack Donoghue, joinedwith Owuor Odonde, made sure that their views onthe subject were also heard. Michael Lacewing touchedon Freud, with the idea of all religious experience beingpsychological, developing from a sense of vulnerabilityand an intense subconscious desire for God to existresulting in a hallucination.The last lecture was again highly controversial, and agood way to end what had been a very intellectuallystimulating day. Chris Horner gave a speech onEuthanasia and Abortion, touching also on the conceptof moral responsibility with the ‘Acts and OmissionsDoctrine’ featuring prominently in his arguments.Reminding us of the different sorts of euthanasia,(active, passive, voluntary and involuntary), he led usthrough the difficult questions of duty, and whether itis actually right for us to take a life.This finished off a fascinating day full of interestingconcepts and ideas. Returning to school brimmingwith theology and philosophy, all that remained tobe said was a huge thank you to Mr Kendry and MissWhite for taking time out to allow us to go to such arewarding and inspirational set of lectures.18 19

The Undiscovered Country:Is Knowledge Discovered or Invented?SAM ELWIN (WB)Upper Sixth ToK StudentThis question is central to the Theory of Knowledgebecause a resolution either way has a significantimpact on the way we think about our acquisitionof knowledge; it also has an impact outside of thephilosophical realm as it has huge ramificationsfor intellectual property laws. For example, if allknowledge is discovered (it existed prior to humanitybecoming aware of it) then it would seem illogical toallow people to patent the discovery itself as they didnot create it, although is there ever a case when theact of discovery itself might merit patenting? Whereasif all knowledge is invented (it did not exist prior tohumanity’s awareness of it – someone had to createit) then all scientific discoveries would be patentable.Plato’s often used definition of knowledge is ‘justifiedtrue belief’, which essentially means that in order forsomething to be considered knowledge it must bebelieved, this belief must be based on evidence andthe belief must be true (it must correspond to reality).I disagree with the claim made in the question as Ibelieve that in order for something to be consideredknowledge it must be discovered; in order to assessthe validity of my belief we will consider several areasof knowing (maths, natural sciences, the arts andethics) and evaluate the arguments for and against thediscovered nature of knowledge.The origin of Mathematics is frequently argued over,possibly due to its claim to certainty coupled with itsabstract nature. Its abstract nature makes some peoplesceptical of its reality, however at the same time it ismiraculously appropriate ‘for the formulation of thelaws of physics’ suggesting that it has some foundationin reality (it would seem implausible for something tobe invented about 20,000 years ago and still be relevantto explaining 21st century physics). Philosophers andmathematicians who insist that maths is invented pointto the development of the numeral system which owingto its numerous incarnations is very likely tohave been invented. Fallibilism presents maths as amere abstraction of these invented numbers. One ofits proponents, Wittgenstein, has been paraphrasedas stating that maths is ‘a motley of overlapping andinterlocking language games’. Fallibilism essentiallypresents maths as an invented “reality”; with each“discovery” being little more than adding to thepainting of known mathematics. However, such a viewof maths is difficult to reconcile with its ‘unreasonableeffectiveness’ in studying the real world; withmathematical inventions/discoveries such as ellipsesand parabolas, which had little application whendiscovered/invented, proving to be essential for moderndevelopments such as modern astronomy.The natural sciences bear many similarities tomathematics in their search for knowledge throughproof, although they lack the ability to achievecomplete certainty due to their inductive nature. Buttheir invented nature is not claimed as a result of theirabstraction, but rather with the way in which they try toexplain natural phenomena. For example as part of ourchemistry course we study hybridisation (an adaptationto molecular orbital theory that tries to explain howtetrahedral molecules form) - in standard orbital theorya tetrahedral molecule should not occur as the centralatom would not be able to form enough sigma bonds.The notion of hybridisation would seem to be aninvention as it is a created explanation for an observed,previously unexplained, phenomenon. However, such aclaim has problems: if hybridisation is actually true thenscientists discovered it - the fact that hybridisation existedprior to our knowledge of it rules out the possibility of itbeing invented. Furthermore if hybridisation is not a trueexplanation of how bonding occurs can it really be calledknowledge as it would not be a ‘true belief’?Ethics is another contentious area of knowledge asthere is great argument over the origins of ethics. Is ourmoral code an invention arrived at through reason inan attempt to create a smoothly running society, or isit discovered, either from a higher power (e.g. God), orthrough reasoned analysis? Anti-realists, in particularconstructivists, believe that ethics is to some extentinvented by humans and that we have moral rulesbecause those are the ones that have been agreed upon;however, from my point of view this is not correct as Ibelieve that we can discover ethics because God has laiddown a moral code. Stephen Law points out some ofthe issues with this viewpoint, such as the Euthyphrodilemma: how do we know that what God says is goodactually is good? However, I would argue that if weassumed not that God was good but that he was allloving then we could be sure that his commandmentswould at least have good intentions and produce peoplewith loving (good) characters (a view of “good” whichwould fit with virtue ethics). Alternatively, philosopherssuch as Immanuel Kant and St Thomas Aquinas haveargued that ethics can be discovered through reasoning:Kant arguing that moral behaviour is itself rational andAquinas, that reason can be used to discover what isnatural and therefore moral. As a result it can be seenthat whether discovered through divine revelation ora reasoned analysis of nature and the choices availableEthics can be discovered.Another area of knowledge that raises significantchallenges to my thesis is the arts. Of all the ways ofknowing, the arts are perhaps the most subjective asthey are largely concerned with individual reactionsand interpretations. Essentially the art work serves as aconduit for the truth that the artist is trying to conveyto the viewer, although not everyone will interpretthe artwork in the same way. As an example a friendclaimed that modern art was not really art and gave a(possibly invented) example of a painting, which hedescribed as a huge board painted white with a largeblack dot in the middle titled “The Meaning ofSilence”. Purely for the sake of argument I claimed thatthis was in fact art as it was just as valid an expressionof silence as the more realistic picture he suggested toexpress the same title. He felt that my argument was infact correct (the truth); however, I had argued the pointsimply for the sake of argument without really believingin what I was saying - does this mean that I inventedthe truth expressed in the painting? Even if I did inventa meaning for the painting my friend discovered it,thereby gaining knowledge, the question is thereforewhether or not I gained knowledge by inventing themeaning. This is complicated, as although I inventedthe truth being expressed by the painting it is notobvious that I invented my knowledge of it as it couldbe argued that through arguing a viewpoint, which Idid not initially hold, I discovered its merit.The arts rely heavily on perception which as a way ofknowing raises significant problems to the idea thatall knowledge is discovered. The reason for this isthat the way we perceive the world is affected by ourexperiences and physical limitations. Furthermore,our brain actually creates a lot of the image that wesee, for example it fills in our blind spots. As a resultcould it be said that all knowledge gained throughsensory experience is invented? However, if our brainis distorting our image of the world is it a true imageand as a result is it knowledge? If the answer to thisquestion was “no” we would have to conclude that itis impossible to gain knowledge through vision, whichwould seem to be highly counterintuitive. To ascertainthe nature of knowledge obtained through perceptionlet us consider insects. To the extent that insects arecapable of knowing, they quite clearly gain knowledgeof their surroundings through the use of their eyes;however, they perceive the world very differently asa result of their compound eyes. To suggest that theyinvented this knowledge because they do not see allreality, would, according to my definition of invention,20 21

equire a capacity for creativity which insects do notseem to possess. As a result it would seem that insectscannot invent their knowledge of their surroundings,thereby suggesting that an inability to see all of realityis not an obstacle to gaining knowledge about it or ofdiscovering that knowledge.It can be seen, in these individual cases, that it is morelikely that knowledge was discovered rather thaninvented. From my experience, people, includingmyself, seem to have a predisposition towards believingthat this is true in general, perhaps the idea that wecan never know the truth is simply to terrible an ideato entertain. Nevertheless, there is a more fundamentalissue with the claim that knowledge can be invented.Gaining knowledge implies that you have learntsomething new about the world, if you did not knowsomething you could not invent that knowledgeand if you did invent it you could not know that theknowledge was actually true. Knowledge of thingsexternal to oneself cannot solely arise from an internalthought process. Such an attempt would have nojustification for the beliefs it creates and thus externalinformation must have been taken in. If externalinformation is being taken in then that informationmust exist independent of the knower hence theknower discovers new knowledge.In a Nutshell: A Reflection onJulian of Norwich’s ‘Revelations ofDivine Love’ROB KEY (M)Lower Sixth IB Philosophy StudentClassical theism is well known for portraying God asthe Father. When thinking of God in today’s societywe, more or less, picture a Man who is strong andpowerful and will always be able to look after us.However, our discussion was of Julian of Norwich,who experienced God as she lay on her bed presumablydying in medieval hospital, as not only our Fatherbut as our Mother. Julian came to an understandingthat “as truly as God is our Father, so truly is Godour Mother.” The main reason for this is that God islove, God causes us to love and it is God that causesus to yearn. The idea, though, seems questionableand to many it might appear (as it did to me beforefully understanding the text) that Julian was merelyunhappy as she had realised how unfair it was onwomen if we do continue to understand God as theFather. How can women ever really achieve equalitywith men if the One, Eternal.Omniscient, Omnipotent God is seen as a man?However after the initial confusion and the initialdesire to discard the idea we see that there is perhapssome obvious reasoning behind it. Besides the fact thatan all powerful, all knowing and divine God whichnothing can compare to would most likely be neithermale nor female (or both perhaps?) the God which webelieve in also holds the attribute of beingomnibenevolent, something very closely linked tofeminist ways. Julian proposed the argument that thebond between mother and child was the only earthlyrelationship that comes close to the relationship wehave with God. God is therefore a mother because ofHer enduring love for us, Her mercifulness and herability to always see us as perfect.Julian of Norwich was adamant that Love be ascribedas the primary quality of the Mother God and alsostressed how She knew no wrath, “…for wrath isnothing else but a perversity and an opposition topeace and love.” This led our discussion on to a massivedigression of topic as we tried to determine what loveactually was and whether the term is appropriatelyused in our society or in Julian’s attributing of God.Although it is evident there are many types of love,it is important to understand what Julian is actuallymeaning when she says that God loves us. Juliansays our relationship with Jesus is most similar tothe relationship between a child and its mother butalso says God shows no wrath. In our discussions weestablished this as a potential flaw in the argumentas for love to be true love a certain degree of wrath,discipline and concession is necessary. All mothersneed to discipline their children to a certain degree toavoid a lazy and demanding natured child yet Julian’s‘Mother’ does not seem capable of providing thisdiscipline. Perhaps this is the reason we are inherentlyirrational and selfish as many philosophers believe usto be? For love to be possible it must be desired byboth partners yet there seem to be countless millionswho refuse to take faith in a Father or a Mother as aGod. Words from The Revelations of Divine Love do notseem to be taking into account today’s more commonatheistic approach “I love thee and thou lovest me, andour love shall never be separated in two”. Whether loveis possible or can ever exist between two individualsis questionable. With love comes attachments andconditions and the word itself can be split into furthercategories and divisions that make determining whatit is exceptionally hard to do. Love is either tragic orsad, it needs passion and can feed off anger and wrath.Although, kindness and a caring aspect are of courseessential for love to work, they are by no means theonly necessary requirements or characteristics of love.22 23

PoetryOn 12th January 2010, an earthquake measuring 7.0 on the Richter scale hit Haiti, destroying much of the capital,Port au Prince. The Remove students were at that time studying the problem of evil and had just turned to thequestion of natural evil. The Haitian earthquake proved a timely reminder that theological questions have pragmaticand pastoral dimensions.The GCSE students were asked to compose a poem which meditated on the question of evil in general and thedisaster in Haiti in particular. A number of these are reproduced here.Sweet FreedomMARY READER (N)Remove GCSE Divinity StudentDevils of dust choke,Bare feet pressing against earthy foundations,A path snaking down to a small village,Cursed among folded hills.A young girl stumbles,Balanced upon her small head,As if a trophy held high,A bucket of murky waterSourced from eternal springs of suffering.Tumultuous clouds cast over the dwelling from thefirmament aboveThundering,Roaring,Growling from the neighbouring hillsEarthy foundations tremor beneath a pair of feet,The power and rage of the AlmightyShuddering…Until silence descends to revealScreams of suffering,Echoing amongst a sea of rubble and dustWherein treasure lies –A small bucket – a trickle of water,Disappeared,Gone.‘DEATHS IN HAITIAN EARTHQUAKE REACHTHREE-HUNDRED-THOUSAND.”Newspapers pour out endless headlines,Narrating the sorrowAcross vast oceans -Gulfs of divergence;Nations of prosperity,Businessmen making their millionsDayAfter day…The clock runs out for anotherAmongst the rubble.And all this in hopeThat amongst nations of ignoranceCharity and compassion will bear the weight of untoldsorrow.Yet by what intention does our omnibenevolent GodAllow the earth to shake thoseMeagre lives into dust?Or allow his renegade angels to taunt his belovedcreationInto misery?By what intention do we –‘Crusaders of democratic freedom’Pay children in the Third WorldA pittance for eternal hours of labour –A trap for prosperity and povertyTo co-exist within the hellish walls of God’sGarden of Eden?Will Eve fall to theTemptations of Evil,EvilVIVIENNE LAZIB (A)Remove GCSE Divinity StudentEvil is an absence;The absence of goodness.Good is not the absence of evil,For love is not the absence of hate.Evil is in doing;By doing malicious deeds.Actions that cause pain;They create suffering upon the innocent.Evil does exist;It exists to make tears hit the floor.It exists as a power to weaken us,And if we allow, it will triumph.HaitiMARCUS HUNTER (M)Remove GCSE Divinity StudentThey woke to the sun filtering inTheir eyes dazzled by the blinding raysThen began a massive dinPeople screaming in waves and wavesThe earth began to shakeThe noise began to roarThe sound of an earthquakeBanging at the doorTake a bite from that sugar-sweet apple,Transformed into Planet Earth,With a portion of peace and loveDevoid from hearts governed by sweet freedom?Evil plays;It plays on our mind.Evil hinders with our mentality,So we must remain strong.Choices are vital;Ability to choose - we can stop evil.The ones who chase away malevolence,Must be praised and not diminished.They are the ones who dare face the Devil,In a desperate struggle to end evil.An intended confrontation.Houses fellThe earth crackedThe ringing sound of the bellIt fell to the ground and smackedThe hard rock floorThere was then silenceThe noise no moreThere was no penance.24 25

I am EvilLIDIA NAWROCKA (A)Remove GCSE Divinity StudentThe Weight of Glory: ReadingC.S. Lewis on Beauty and LoveI am the one you never seeI am the one that is always thereI am the one that many say does not existI am the one that is always someone’s faultI am the one that people argue overI am the one you always blameI am the one you never noticeI am the one you see far too lateI am the one you will never understandI am the one you never want to be withI am the one you try to get rid ofI am the one who is proudI am the one who is enviousI am the one who is greedyI am the one who is vainI am the one who is lustfulI am the one who is lazeI am the one who is angryI am the one who hatesI am the one that liesI am the one in youI am the one.I am evil.FLORENCE BELL (T)Lower Sixth IB Philosophy StudentThis sermon of Lewis’, published in THEOLOGY1941, is considered by many critics to be one of hisbest. Exploring as it does the concept of “love”; itdraws on the value of reward, not in such a way as tomake “Christian life a mercenary affair”, but insteadreshaping our concept of reward, showing it to be, asLewis says “the activity itself in consummation”. Hiscomparison of the Christian to a reluctant schoolboyallows us to consider the way in which Christianobedience must first seem to be a duty, before it can beseen as a joy, whilst his reference to the “far-off country”wherein we are able to find the satisfaction of ourdesire for beauty is incredibly resonant. It draws on ourintimate selves, that part of ourselves, that secret that ashe says “hurts so much that you take your revenge onit by calling it names like Nostalgia and Romanticismand Adolescence”. In doing so it therefore provides forthe reader of the sermon a point of personal reference,from which we can draw our own inspiration inconsideration of the form of beauty, be it throughreligious piety or otherwise.It is through this contemplation of the form in factthat we are able to show some form of reasoning forthe existence of a paradisiacal state. Using the analogyof a man hungering for bread, Lewis argues that thefact that we strive for a satisfaction of this desire is notto say that it will ever be fulfilled, but that it proves tosome extent there must be something that will satisfyit to some extent. In a similar way, the man’s hungerdemonstrates he “comes of a race which repairs its bodyby eating and inhabits a world where eatable substancesexist.” As such there is reasoned proof, demonstratingthe logic of belief in a higher plane of existence, forwhich we are intended to strive.In Lewis’s opinion, this state of Paradise is synonymouswith being with God: “he who has God and everythingelse has no more than he who has God only.” Forthis reason, for him, Glory is not associated as ittraditionally is, with fame or luminosity. Instead,glory is being “noticed by God”, to be known byhim. In this way it tends far more to the notion ofsplendour, allowing us to share in the brightness ofwonder. However, Lewis makes a point that furtherenhances this concept of glory: it is through assistingour neighbours in achieving theirs, that we becometruly glorified. This clearly is part of the notion oflove mentioned earlier in the passage, an extensionof the love for God and for fellow-man proclaimedthroughout Christ’s teaching. Mere tolerance or “othersuch flippancies” are not to be tolerated as they detractfrom the value of true, unconditional love, as it ismeant to be. It is only through the realisation of thislove, for God and for fellow mortals that we are trulyable to comprehend, and attain, the Weight of Glory asa true reward.26 27