128 K. Rastle, M. Brysbaert / Cognitive Psychology 53 (2006) 97–145cost <strong>in</strong> terms of total orthographic activation, however, a cost which would have to be taken<strong>in</strong>to account <strong>in</strong> the re<strong>for</strong>mulation of any lexical decision rule.Further analyses of the DRC model under this parameterization reveal another veryserious cost: These alterations to the model leave it unable to read aloud exception words.The DRC model used <strong>in</strong> Simulation 5 was presented with the 88 exception words and the88 matched regular words developed by Rastle and Coltheart (1999) <strong>for</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g aloud.Though the model read aloud 85/88 regular words correctly, it read aloud 0/88 exceptionwords correctly. These errors comprised regularizations (69/88; e.g., ‘books’fi/buks/), lexicalizations(3/88; e.g., ‘tsar’fi/tai/), and other k<strong>in</strong>ds of error (16/88; e.g., ‘aft’fi/ææt/).Given the massive contribution of assembled phonology required to simulate fast <strong>phonological</strong><strong>prim<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>effects</strong> on lexical decision, it is not surpris<strong>in</strong>g that exception words posesuch difficulty <strong>for</strong> the DRC model under this parameterization.6.7. Simulation 6These simulations leave us <strong>in</strong> a difficult position. On the one hand, the DRC modeloperat<strong>in</strong>g under the standard set of parameters <strong>for</strong> lexical decision (Simulation 1) doesnot come close to simulat<strong>in</strong>g fast <strong>phonological</strong> <strong>prim<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>effects</strong>. On the other hand, theDRC parameterization that shows some scope <strong>for</strong> simulat<strong>in</strong>g fast <strong>phonological</strong> <strong>prim<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>effects</strong> on lexical decision (Simulation 5) cannot correctly read aloud exception words. Ifour evaluation of the DRC model requires that it simulate fast <strong>phonological</strong> <strong>prim<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>effects</strong> on lexical decision us<strong>in</strong>g a set of parameters that can also read aloud, then the modelseems almost certa<strong>in</strong>ly false. An alternative approach would be to justify us<strong>in</strong>g theparameters developed <strong>in</strong> Simulation 5 <strong>for</strong> lexical decision while adopt<strong>in</strong>g the standardset of parameters (Coltheart et al., 2001; Rastle & Coltheart, 1999) <strong>for</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g aloud.Indeed, Coltheart et al. (2001) used a parameter set <strong>for</strong> simulat<strong>in</strong>g lexical decision that differedvery slightly (on a s<strong>in</strong>gle parameter) from that used <strong>for</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g aloud—justify<strong>in</strong>g thissmall parameter change as a strategic response to the specific demands posed by the lexicaldecision task.In Simulation 6, we <strong>in</strong>vestigated quantitatively whether we could offer a specific justification<strong>for</strong> adopt<strong>in</strong>g the parameter set used <strong>in</strong> Simulation 5 <strong>for</strong> lexical decision. Our logicwas simple. We reasoned that the lexical decision task requires readers to discrim<strong>in</strong>atebetween word and nonword stimuli. As such, any strategic variation <strong>in</strong> the parametersused <strong>for</strong> lexical decision should maximize—not m<strong>in</strong>imize—the model’s ability to per<strong>for</strong>mthis discrim<strong>in</strong>ation. If the parameters used <strong>in</strong> Simulation 5 are to be justified <strong>in</strong> terms of astrategic variation due to the demands posed by the lexical decision task, then words andnonwords should produce a larger difference <strong>in</strong> the sources of activation used to make alexical decision when the model is controlled by the parameters used <strong>in</strong> Simulation 5 thanwhen it is controlled by the standard parameters <strong>for</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g aloud (Coltheart et al., 2001;Rastle & Coltheart, 1999). We there<strong>for</strong>e presented two parameterizations of the DRCmodel with the 112 word targets and the 112 nonword targets used <strong>in</strong> Experiment 1,and monitored the two sources of activation currently used to make a lexical decision(i.e., the total activation of the orthographic lexicon and the maximum activation ofany s<strong>in</strong>gle unit; see Coltheart et al., 2001) <strong>for</strong> a 100 cycle period with<strong>in</strong> each parameterization.If the parameters developed <strong>in</strong> Simulation 5 are to be justified <strong>for</strong> use <strong>in</strong> lexicaldecision on strategic grounds, then they should work to maximize the model’s ability todiscrim<strong>in</strong>ate between words and nonwords.

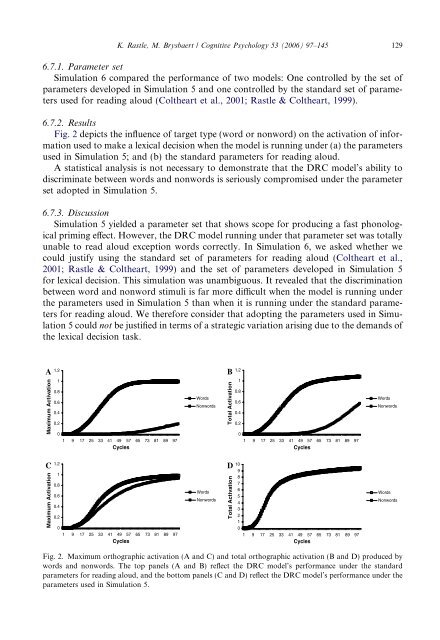

K. Rastle, M. Brysbaert / Cognitive Psychology 53 (2006) 97–145 1296.7.1. Parameter setSimulation 6 compared the per<strong>for</strong>mance of two models: One controlled by the set ofparameters developed <strong>in</strong> Simulation 5 and one controlled by the standard set of parametersused <strong>for</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g aloud (Coltheart et al., 2001; Rastle & Coltheart, 1999).6.7.2. ResultsFig. 2 depicts the <strong>in</strong>fluence of target type (word or nonword) on the activation of <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mationused to make a lexical decision when the model is runn<strong>in</strong>g under (a) the parametersused <strong>in</strong> Simulation 5; and (b) the standard parameters <strong>for</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g aloud.A statistical analysis is not necessary to demonstrate that the DRC model’s ability todiscrim<strong>in</strong>ate between words and nonwords is seriously compromised under the parameterset adopted <strong>in</strong> Simulation 5.6.7.3. DiscussionSimulation 5 yielded a parameter set that shows scope <strong>for</strong> produc<strong>in</strong>g a fast <strong>phonological</strong><strong>prim<strong>in</strong>g</strong> effect. However, the DRC model runn<strong>in</strong>g under that parameter set was totallyunable to read aloud exception words correctly. In Simulation 6, we asked whether wecould justify us<strong>in</strong>g the standard set of parameters <strong>for</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g aloud (Coltheart et al.,2001; Rastle & Coltheart, 1999) and the set of parameters developed <strong>in</strong> Simulation 5<strong>for</strong> lexical decision. This simulation was unambiguous. It revealed that the discrim<strong>in</strong>ationbetween word and nonword stimuli is far more difficult when the model is runn<strong>in</strong>g underthe parameters used <strong>in</strong> Simulation 5 than when it is runn<strong>in</strong>g under the standard parameters<strong>for</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g aloud. We there<strong>for</strong>e consider that adopt<strong>in</strong>g the parameters used <strong>in</strong> Simulation5 could not be justified <strong>in</strong> terms of a strategic variation aris<strong>in</strong>g due to the demands ofthe lexical decision task.A1.2B1.2Maximum Activation10.80.60.40.201 9 17 25 33 41 49 57 65 73 81 89 97CyclesWordsNonwordsTotal Activation10.80.60.40.201 9 17 25 33 41 49 57 65 73 81 89 97CyclesWordsNonwordsCMaximum Activation1.210.80.60.40.201 9 17 25 33 41 49 57 65 73 81 89 97CyclesWordsNonwordsDTotal Activation1098765432101 9 17 25 33 41 49 57 65 73 81 89 97CyclesWordsNonwordsFig. 2. Maximum orthographic activation (A and C) and total orthographic activation (B and D) produced bywords and nonwords. The top panels (A and B) reflect the DRC model’s per<strong>for</strong>mance under the standardparameters <strong>for</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g aloud, and the bottom panels (C and D) reflect the DRC model’s per<strong>for</strong>mance under theparameters used <strong>in</strong> Simulation 5.

- Page 5 and 6: K. Rastle, M. Brysbaert / Cognitive

- Page 7 and 8: Table 1Studies of English phonologi

- Page 9 and 10: Table 2Studies of English phonologi

- Page 11 and 12: Table 4Studies of English phonologi

- Page 13 and 14: Table 5Studies of English phonologi

- Page 15 and 16: K. Rastle, M. Brysbaert / Cognitive

- Page 17 and 18: K. Rastle, M. Brysbaert / Cognitive

- Page 19 and 20: K. Rastle, M. Brysbaert / Cognitive

- Page 21 and 22: Phonological priming effects on RTs

- Page 23 and 24: As in Experiment 1, we assessed pho

- Page 25 and 26: simulation of masked priming. It is

- Page 27 and 28: items yielded this pattern; and at

- Page 29 and 30: K. Rastle, M. Brysbaert / Cognitive

- Page 31: Despite improvement in the analysis

- Page 35 and 36: K. Rastle, M. Brysbaert / Cognitive

- Page 37 and 38: K. Rastle, M. Brysbaert / Cognitive

- Page 39 and 40: K. Rastle, M. Brysbaert / Cognitive

- Page 41 and 42: flu phlue slaur DSD 727 669 0.15 0.

- Page 43 and 44: nerve nurve narve SDS 563 547 0.10

- Page 45 and 46: K. Rastle, M. Brysbaert / Cognitive

- Page 47 and 48: K. Rastle, M. Brysbaert / Cognitive

- Page 49: K. Rastle, M. Brysbaert / Cognitive