Language, Culture, and Adaptation in Immigrant Children - Harvard ...

Language, Culture, and Adaptation in Immigrant Children - Harvard ...

Language, Culture, and Adaptation in Immigrant Children - Harvard ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

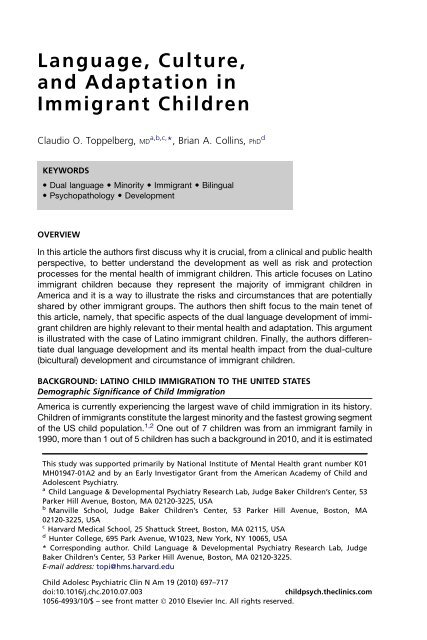

<strong>Language</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>,<strong>and</strong> <strong>Adaptation</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>Immigrant</strong> <strong>Children</strong>Claudio O. Toppelberg, MD a,b,c, *, Brian A. Coll<strong>in</strong>s, PhD dKEYWORDS Dual language M<strong>in</strong>ority <strong>Immigrant</strong> Bil<strong>in</strong>gual Psychopathology DevelopmentOVERVIEWIn this article the authors first discuss why it is crucial, from a cl<strong>in</strong>ical <strong>and</strong> public healthperspective, to better underst<strong>and</strong> the development as well as risk <strong>and</strong> protectionprocesses for the mental health of immigrant children. This article focuses on Lat<strong>in</strong>oimmigrant children because they represent the majority of immigrant children <strong>in</strong>America <strong>and</strong> it is a way to illustrate the risks <strong>and</strong> circumstances that are potentiallyshared by other immigrant groups. The authors then shift focus to the ma<strong>in</strong> tenet ofthis article, namely, that specific aspects of the dual language development of immigrantchildren are highly relevant to their mental health <strong>and</strong> adaptation. This argumentis illustrated with the case of Lat<strong>in</strong>o immigrant children. F<strong>in</strong>ally, the authors differentiatedual language development <strong>and</strong> its mental health impact from the dual-culture(bicultural) development <strong>and</strong> circumstance of immigrant children.BACKGROUND: LATINO CHILD IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATESDemographic Significance of Child ImmigrationAmerica is currently experienc<strong>in</strong>g the largest wave of child immigration <strong>in</strong> its history.<strong>Children</strong> of immigrants constitute the largest m<strong>in</strong>ority <strong>and</strong> the fastest grow<strong>in</strong>g segmentof the US child population. 1,2 One out of 7 children was from an immigrant family <strong>in</strong>1990, more than 1 out of 5 children has such a background <strong>in</strong> 2010, <strong>and</strong> it is estimatedThis study was supported primarily by National Institute of Mental Health grant number K01MH01947-01A2 <strong>and</strong> by an Early Investigator Grant from the American Academy of Child <strong>and</strong>Adolescent Psychiatry.a Child <strong>Language</strong> & Developmental Psychiatry Research Lab, Judge Baker <strong>Children</strong>’s Center, 53Parker Hill Avenue, Boston, MA 02120-3225, USAb Manville School, Judge Baker <strong>Children</strong>’s Center, 53 Parker Hill Avenue, Boston, MA02120-3225, USAc <strong>Harvard</strong> Medical School, 25 Shattuck Street, Boston, MA 02115, USAd Hunter College, 695 Park Avenue, W1023, New York, NY 10065, USA* Correspond<strong>in</strong>g author. Child <strong>Language</strong> & Developmental Psychiatry Research Lab, JudgeBaker <strong>Children</strong>’s Center, 53 Parker Hill Avenue, Boston, MA 02120-3225.E-mail address: topi@hms.harvard.eduChild Adolesc Psychiatric Cl<strong>in</strong> N Am 19 (2010) 697–717doi:10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.003childpsych.thecl<strong>in</strong>ics.com1056-4993/10/$ – see front matter Ó 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

698Toppelberg & Coll<strong>in</strong>sthat these figures will rise to 1 out of 3 children by the year 2020. 3 There is a significant3-way overlap between Lat<strong>in</strong>o, dual language, <strong>and</strong> immigrant children <strong>in</strong> the UnitedStates. The majority of Lat<strong>in</strong>o children come from immigrant families, <strong>and</strong> most immigrantfamilies <strong>and</strong> children <strong>in</strong> the United States are Lat<strong>in</strong>o. 4 Most immigrant familiesspeak a language other than English at home (most commonly Spanish) <strong>and</strong> a largeproportion of children <strong>in</strong> America grow up us<strong>in</strong>g 2 languages. The past 3 decadeshave seen a rapid <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong>os <strong>in</strong> the United States with their numbers morethan tripl<strong>in</strong>g from 1970 (10 million) to 2000 (35 million). 4 Lat<strong>in</strong>o children are alreadythe largest m<strong>in</strong>ority group <strong>in</strong> schools. 5The majority of children from immigrant families are second-generation immigrants,that is, born <strong>in</strong> the United States to 1 or 2 foreign-born parents; most US Lat<strong>in</strong>o youthare young (median age 12.8) <strong>and</strong> from the second generation (52%). 6,7 Despite theiryoung age <strong>and</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g numbers, empirical research address<strong>in</strong>g the development,wellbe<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> mental health of children of immigrants is lack<strong>in</strong>g, with most of thework focused on adolescents <strong>and</strong> adults. 8Public Health Significance: Risk of Depression, Suicidality, <strong>and</strong> SchoolFailure <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong>o <strong>Children</strong>Many children of immigrants, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Lat<strong>in</strong>os, live <strong>in</strong> families exposed to multiple riskfactors, such as poverty; poor schools; neighborhood violence; discrim<strong>in</strong>ation; <strong>and</strong>disparities <strong>in</strong> access to health care, education, <strong>and</strong> jobs. 9–11 All these factors arestrongly associated with low performance at school <strong>and</strong> poor psychosocial adaptation,as well as negative economic <strong>and</strong> health outcomes. 3,12,13 Most of these factorshave been found to be associated with high prevalence of mental disorders. In severalimportant areas, Lat<strong>in</strong>o youth are at a higher emotional, behavioral, <strong>and</strong> academic riskthan European American <strong>and</strong> other m<strong>in</strong>ority youth. 14,15Depression, violence, <strong>and</strong> substance abuse risk <strong>in</strong>dicatorsWhen compared with European Americans <strong>and</strong> African Americans, Lat<strong>in</strong>o youth (bothboys <strong>and</strong> girls) present the highest prevalence of <strong>in</strong>dicators of depression (36%) 14 <strong>and</strong>suicidality, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g hav<strong>in</strong>g made a suicide plan (14.5%) or attempt (11%), with thisrisk be<strong>in</strong>g astonish<strong>in</strong>gly high among Lat<strong>in</strong>o girls. 14,16 Most <strong>in</strong>dicators of violence (be<strong>in</strong>gthreatened with a weapon or be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a physical fight while on school property, miss<strong>in</strong>gschool because of safety concerns, carry<strong>in</strong>g a gun or weapon) are higher <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong>o than<strong>in</strong> white <strong>and</strong> black youth. 14 Lat<strong>in</strong>o teenagers have the highest rates of illegal <strong>in</strong>jectiondrug abuse, methamphetam<strong>in</strong>e, ecstasy, <strong>and</strong> coca<strong>in</strong>e. 14 US-born Lat<strong>in</strong>os may havehigher behavioral problem prevalence 17 <strong>and</strong>, <strong>in</strong> large epidemiologic studies, higherlifetime prevalence of mental disorders (32% to 24%) 18 than foreign-born Lat<strong>in</strong>os(see the later discussion about the immigrant paradox). This prevalence has led 2prom<strong>in</strong>ent Lat<strong>in</strong>o researchers to ask the question: “What is it about liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the USthat may place Lat<strong>in</strong>os at risk for psychological disorders <strong>and</strong> suicidal behaviors?” 19Educational risk <strong>in</strong>dicatorsLat<strong>in</strong>os as a group have extremely low high school graduation rates (53%), 20 collegegraduation rates, <strong>and</strong> achievement <strong>and</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g scores 21,22 (at grade 11, they averagegrade 8 achievement levels), but the causes of such alarm<strong>in</strong>g educational outcomesare not fully understood. Lat<strong>in</strong>o children are 6 times more likely to be placed <strong>in</strong> specialeducation services. They lag beh<strong>in</strong>d African Americans, European Americans, <strong>and</strong>Asian Americans <strong>in</strong> high school completion, high-technology education, <strong>and</strong> collegeadmission. As a consequence, Lat<strong>in</strong>o children as a group are more likely to becomeor rema<strong>in</strong> poor. Educational <strong>and</strong> socioeconomic status are l<strong>in</strong>ked to health <strong>in</strong> general<strong>and</strong> to mental health <strong>in</strong> particular. 9 Although there is important overlap between

<strong>Language</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Adaptation</strong> 699psychopathology <strong>and</strong> negative educational outcomes (for <strong>in</strong>stance, depression,conduct, <strong>and</strong> antisocial disorders are associated with low educational achievement),the extent to which mental health factors contribute to high-school dropout rates <strong>and</strong>educational failure <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong>o youth is unknown.Protective Processes <strong>and</strong> Resilience <strong>in</strong> <strong>Children</strong> of <strong>Immigrant</strong>s: the <strong>Immigrant</strong> ParadoxA multidimensional perspective on psychosocial strengths, rather than a narrow, exclusivefocus on deficit <strong>and</strong> pathology, is fundamental <strong>in</strong> ga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a deeper underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g ofthe mental health <strong>and</strong> function<strong>in</strong>g of Lat<strong>in</strong>o children of immigrants. Although manyimmigrant families <strong>and</strong> their children face the multiple risk factors already discussed,they also br<strong>in</strong>g with them several characteristics that may serve as protective factors,such as religion, community, optimism, dual frame of reference, <strong>and</strong> high valu<strong>in</strong>g ofeducation. 23 Many children of immigrants have shown to be extremely resilient despiterisk <strong>and</strong> adversity. 24 Lat<strong>in</strong>o parents frequently share the goal to have their childrendevelop <strong>in</strong>strumental competences <strong>and</strong> to preserve values related to <strong>in</strong>trapersonal(personalismo) <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpersonal (respeto) skills, family connections (familismo), theexpression of affection (car<strong>in</strong>˜os), <strong>and</strong> the value of education (educacio´n). 25 These typesof strengths are an important part of the traditions <strong>and</strong> values of Lat<strong>in</strong>os <strong>and</strong> other immigrantgroups <strong>and</strong> are widely cited <strong>in</strong> the literature. 2,8,26,27For a long time <strong>and</strong> based on a deficit model, it had been assumed that recent immigrantswould have less favorable outcomes than their US-born immigrant <strong>and</strong> nonimmigrantpeers. However, recent empirical work strongly suggests exactly theopposite, namely, that recent immigrants fare better <strong>in</strong> many areas of health,a phenomenon that has come to be known as the immigrant paradox. 12,28,29 Betterphysical <strong>and</strong> mental health as well as educational achievement are be<strong>in</strong>g documented<strong>in</strong> foreign-born Lat<strong>in</strong>o immigrants (first generation) compared with their US-born counterparts(second <strong>and</strong> later generations). 9,30 The first generation has lower levels ofdepression, anxiety, <strong>and</strong> substance abuse, <strong>and</strong> higher positive adjustment than theirUS-born peers, 31–33 <strong>in</strong> particular <strong>in</strong> those of Mexican <strong>and</strong>, to some extent, Cub<strong>and</strong>escent. 34 As stated before, this raises the question of what it is about liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> theUnited States that may place Lat<strong>in</strong>os at higher risk. 19The knowledge base on Lat<strong>in</strong>o <strong>and</strong> other dual language immigrant children is limited<strong>and</strong> needs to be significantly exp<strong>and</strong>ed. For important cl<strong>in</strong>ical, public health, <strong>and</strong>educational reasons, it is critical to underst<strong>and</strong> risk <strong>and</strong> protective doma<strong>in</strong>s specificto the development of these children. Further research exp<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g evidence-basedunderst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> lead<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>in</strong>terventions <strong>and</strong> policy directed at young children ofimmigrants are critically needed. One specific area that is poorly understood is theimpact of these children’s develop<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>guistic competence <strong>in</strong> 2 languages on theiremotional/behavioral function<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> mental health.THE DEVELOPMENT OF DUAL LANGUAGE (BILINGUAL) COMPETENCEMost of the research on language development has centered on monol<strong>in</strong>gual children.Although the study of children acquir<strong>in</strong>g 2 or more languages is still <strong>in</strong> its early stages,significant progress made <strong>in</strong> the last 3 decades is reviewed <strong>in</strong> the section that follows.The Development of Dual <strong>Language</strong> L<strong>in</strong>guistic CompetenceDoma<strong>in</strong>s of language development<strong>Language</strong> competence is composed of competences <strong>in</strong> specific doma<strong>in</strong>s of languagedevelopment, such as phonology (the sound system), syntax <strong>and</strong> morphology (pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesthat govern word order <strong>and</strong> word formation), <strong>and</strong> lexicon/semantics (vocabulary,

700Toppelberg & Coll<strong>in</strong>smean<strong>in</strong>g), all of which <strong>in</strong>terface with language usage (pragmatics, discourse). 35–37Although first-language acquisition is a lifelong process, the majority takes placedur<strong>in</strong>g early childhood. 35,38,39 <strong>Language</strong> competence is not a stable construct 40 but,rather, a fluctuat<strong>in</strong>g, dynamic, multidoma<strong>in</strong> capacity. 41,42The <strong>in</strong>fluence of the environments of the child on dual language developmentDual language development is dependent, among other factors, on the type <strong>and</strong>amount of exposure <strong>and</strong> the age at which children beg<strong>in</strong> acquir<strong>in</strong>g their secondlanguage. Sequential bil<strong>in</strong>guals acquire their first language (L1) dur<strong>in</strong>g the period ofrapid language acquisition before 3 years of age <strong>and</strong> a second language (L2) later.Simultaneous bil<strong>in</strong>guals acquire both languages as first languages (2 L1s). BecauseLat<strong>in</strong>o children <strong>in</strong> the United States typically acquire Spanish as an L1 <strong>and</strong> Englishas an L2, most are sequential bil<strong>in</strong>guals. The term dual language children has becomefavored over bil<strong>in</strong>gual more recently, because it does not presuppose full proficiency<strong>in</strong> both languages <strong>and</strong> it allows for the reality of <strong>in</strong>dividual differences <strong>in</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>gual development,with wide variability of L1 <strong>and</strong> L2 competences. 43,44Sequential bil<strong>in</strong>guals have their language competences distributed acrosslanguages, with vary<strong>in</strong>g degrees of skills <strong>in</strong> each language, particularly <strong>in</strong> thosedoma<strong>in</strong>s highly dependent upon language exposure, such as semantics. 45,46 In thisway, it would be natural to f<strong>in</strong>d, <strong>in</strong> Spanish/English dual language children, that vocabularyrelated to the school context is stronger <strong>in</strong> English, whereas that related to thehome context is stronger <strong>in</strong> Spanish. This situation presents unique complexities <strong>in</strong>the mental process<strong>in</strong>g of their language systems, <strong>and</strong> how these relate to their adaptationalfunction<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> their ability to tap <strong>in</strong>to protective resources.Although it is rare for anyone to be equally proficient across all l<strong>in</strong>guistic contexts<strong>and</strong> doma<strong>in</strong>s, high competence <strong>in</strong> both languages is possible. 47 Also common is forbil<strong>in</strong>guals to be dom<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>in</strong> 1 language, but the particular configuration of languagedom<strong>in</strong>ance varies widely. 48 The dom<strong>in</strong>ant language of an <strong>in</strong>dividual often fluctuatesover time <strong>and</strong> across contexts, 49 so that language dom<strong>in</strong>ance is not stable.Because of the assimilative forces that propel children of immigrants to learn Englishquickly, language shift or loss starts occurr<strong>in</strong>g as soon as they beg<strong>in</strong> school. Secondgenerationimmigrants are more likely to lose their first language than to rema<strong>in</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>gual.50 Contrary to the popularized (but <strong>in</strong>accurate) belief that immigrant children arenot learn<strong>in</strong>g English, this process of L1 loss is occurr<strong>in</strong>g much sooner than <strong>in</strong> priorwaves of immigration, when it was more typical for the second generation to rema<strong>in</strong>bil<strong>in</strong>gual, <strong>and</strong> only for the third generation to become English dom<strong>in</strong>ant. 51–53 Outsideof the home, children of immigrants often start us<strong>in</strong>g English exclusively, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> thehome, as much as they can, 33 even when they have only learned barely enough tomuddle through communication. 54 Consider<strong>in</strong>g the frequent discrim<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong>stigmas associated with speak<strong>in</strong>g a language other than English <strong>in</strong> the UnitedStates, 55 it is underst<strong>and</strong>able that children will prefer to speak the dom<strong>in</strong>ant, communitylanguage. This result of societal <strong>and</strong> school pressures, comb<strong>in</strong>ed with a devaluedview of the m<strong>in</strong>ority language, is truly unfortunate, as there is wide consensus amongdual language acquisition researchers that it is not necessary for children to have toab<strong>and</strong>on their home language to develop strong competences <strong>in</strong> the second, majoritylanguage 56 <strong>and</strong> that proficient bil<strong>in</strong>gualism, a normative developmental outcome,often results <strong>in</strong> academic, cognitive, <strong>and</strong> social benefits. 43,45,57–59The development of both the L1 <strong>and</strong> L2 is to a good extent dependent upon the levelof language support <strong>and</strong> language exposure. Subtractive bil<strong>in</strong>gualism tends to occurwhen L2 acquisition comes at the cost of the loss of the L1, when children aresubmersed <strong>in</strong> a majority language with limited support <strong>and</strong> exposure to their home

<strong>Language</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Adaptation</strong> 701language (subtractive bil<strong>in</strong>gual sett<strong>in</strong>gs). 51,60–62 Additive bil<strong>in</strong>gualism, <strong>in</strong> contrast, iscommon <strong>in</strong> sett<strong>in</strong>gs where substantial support for the L1 is offered as the L2 isacquired, 51 which leads to the well-documented benefits of proficiency <strong>in</strong> 2languages. 38,57,63,64 Research from 2 decades ago 65 suggested that <strong>in</strong>creased movementtoward English-language use among children of immigrants occurs primarilydur<strong>in</strong>g the adolescent years as youths spend more time <strong>in</strong> contexts outside of thehome. However, more recent research is show<strong>in</strong>g a similar shift much earlier, whenchildren first beg<strong>in</strong> school<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> develop proficiency <strong>and</strong> general preference forthe English language. <strong>Language</strong> shift has been evidenced as early as preschool ork<strong>in</strong>dergarten, <strong>and</strong> through the elementary grades. 66 Wong-Fillmore 62 found that earlyexposure to English leads to first-language loss. The younger children are when theylearn English, the greater the effect; children attend<strong>in</strong>g L2 preschools were subsequentlymore likely to be unable to speak the home language than children whoattended L1 preschools. For all children, there is an established relationship betweenthe l<strong>in</strong>guistic environment at home <strong>and</strong> children’s later language competence. 67,68<strong>Children</strong> <strong>in</strong> stimulat<strong>in</strong>g environments show more rapid language development 69 <strong>and</strong>maternal language abilities contribute to large variation <strong>in</strong> children’s vocabularygrowth. 70 <strong>Children</strong> from lower socioeconomic status (SES) have lower language skills<strong>and</strong> smaller vocabularies than children from higher SES. 71,72 For dual language children,the l<strong>in</strong>guistic environment at home is closely associated with children’s languagepreference, dom<strong>in</strong>ance, competence, <strong>and</strong> usage. 43,73 It is therefore clear that the environmentsat home <strong>and</strong> school are <strong>in</strong>fluential <strong>in</strong> language development <strong>and</strong>, morespecifically, the ma<strong>in</strong>tenance <strong>and</strong> loss of first <strong>and</strong> second languages. Societal <strong>and</strong>school pressures to lose L1 raise serious ethical concerns. Ethical concerns arisebecause press<strong>in</strong>g children <strong>in</strong>to los<strong>in</strong>g their first language <strong>and</strong> the chance of proficiency<strong>in</strong> their 2 languages means, <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly globalized economy <strong>and</strong> diverse society,“to deprive them of access to important job- <strong>and</strong> life-related skills.” 74The development of children’s home language may associate with strengthen<strong>in</strong>g offamily cohesion <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>timacy, parental authority, <strong>and</strong> transmission of cultural norms,all of which can lead to healthy adjustment <strong>and</strong> a strong identification <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternalizationof the social values of the family. 75–79 Develop<strong>in</strong>g L2 skills is crucial for academicsuccess <strong>and</strong> long-term social <strong>and</strong> economic well-be<strong>in</strong>g 80,81 because children’s abilityto function with<strong>in</strong> the school context <strong>in</strong>fluences school retention, graduation rates, <strong>and</strong>cont<strong>in</strong>uation <strong>in</strong>to higher education.For adolescents, the wide range of media <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly available <strong>in</strong> immigrants’ L1s(radio, television, <strong>and</strong> the Internet) may help immigrants ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> a mean<strong>in</strong>gfulconnection to their heritage, culture, <strong>and</strong> language, but also allows <strong>in</strong>creased accessto aspects of American society. 82 Likewise, prior exposure to the dest<strong>in</strong>ation languagebefore migration contributes to better skills <strong>in</strong> the host language upon immigration. 83Contextualized <strong>in</strong>terpersonal communication skills versus decontextualizedacademic language proficiencyAll children typically move between language environments throughout the day, as thecharacteristics of language spoken differs from the classroom to other environments,with a remarkable contrast <strong>in</strong> the quality of language competences required.<strong>Language</strong> at home <strong>and</strong> the playground tends to be contextualized (ie, it conta<strong>in</strong>smultiple references to shared physical, family, social, affective, <strong>and</strong> communicativecontexts), rely<strong>in</strong>g on shared knowledge (long-term memory). It is <strong>in</strong>dividualized forthe listener, who can ask for clarification. 84–86 Contextualized language thus m<strong>in</strong>imizesthe l<strong>in</strong>guistic <strong>and</strong> cognitive process<strong>in</strong>g dem<strong>and</strong>s. In contrast, language <strong>in</strong> the classroomtends to be decontextualized; that is, it is abstract, relies heavily on l<strong>in</strong>guistic

702Toppelberg & Coll<strong>in</strong>s<strong>and</strong> cognitive process<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> is detached from a common outside reference. Themessage is self-conta<strong>in</strong>ed, to be decoded by any unknown listener without referenceor assistance. 87 Cumm<strong>in</strong>s 88 formally dist<strong>in</strong>guished the 2 types of language competencesas basic <strong>in</strong>terpersonal communicative skills (BICS; the more context rich,less cognitively complex areas of language use, common <strong>in</strong> the home <strong>and</strong> the playground)<strong>and</strong> cognitive academic l<strong>in</strong>guistic proficiency (CALP; the more contentspecific, cognitively dem<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g areas of language, typical <strong>in</strong> the classroom). Thespecific relevance of this to the dual language child is that acquir<strong>in</strong>g CALP <strong>in</strong> a secondlanguage, a prerequisite for academic achievement, generally takes an extended time(5–7 years). BICS <strong>in</strong> a second language takes much less time to develop (2–3 years)<strong>and</strong> this superficial communicative ability may mislead adults <strong>and</strong> teachers <strong>in</strong>toth<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g that the child is ready for English-only classroom placement, when <strong>in</strong> factthe child only has <strong>in</strong>terpersonal fluency, but not enough academic proficiency <strong>in</strong>English.Dual language profiles <strong>and</strong> low language competenceThe language profiles of dual language children can be characterized, at a given developmentalpo<strong>in</strong>t, based on whether they have age-appropriate competence <strong>in</strong> bothlanguages (balanced bil<strong>in</strong>guals), age-appropriate competence <strong>in</strong> one language <strong>and</strong>low competence the other (typically, children who are L1 or L2 dom<strong>in</strong>ant), or lowcompetence <strong>in</strong> both (low L1/L2 competence). 47,49,89–92 The low L1/L2 profile isconsidered here a low language competence (low LC) group, while it is also hypothesizedthat when children dom<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>in</strong> one language have low LC <strong>in</strong> the otherlanguage, they may be at risk as well. Although these children’s low LC profiles mayrepresent, <strong>in</strong> many cases, a stepp<strong>in</strong>g stone toward established balanced bil<strong>in</strong>gualismor functional language dom<strong>in</strong>ance, <strong>in</strong> other cases they may arguably be an early risk<strong>in</strong>dicator for persistently low LC associated with adaptational <strong>and</strong> mental health problems.The low L1/L2 profile group likely <strong>in</strong>cludes children with true language impairments<strong>and</strong> delays, which are certa<strong>in</strong>ly possible <strong>in</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>gual (as they are <strong>in</strong>monol<strong>in</strong>gual) children.DUAL LANGUAGE (BILINGUAL) LINGUISTIC COMPETENCE AND THE MENTAL HEALTHOF CHILDREN OF IMMIGRANTSAssociation of <strong>Language</strong> Competence <strong>and</strong> Psychosocial <strong>Adaptation</strong>It has been well documented that language competence is a critical contributor to theemotional <strong>and</strong> behavioral development of monol<strong>in</strong>gual children. 37,93 However, less isknown about how this contribution is represented for children who speak multiplelanguages. The empirical research focus<strong>in</strong>g on the association between dual languagel<strong>in</strong>guistic competence <strong>and</strong> mental health <strong>and</strong> emotional/behavioral function<strong>in</strong>g islimited. 94 Thus, the authors will first review the related research <strong>in</strong> monol<strong>in</strong>gual children<strong>and</strong> then extend the discussion to dual language children. <strong>Language</strong> competenceis related to mental health <strong>in</strong> children. On the one h<strong>and</strong>, low languagecompetence accompanies poor adaptation <strong>and</strong> psychopathology. On the other,good language skills are the substrate of many protective factors, such as IQ, <strong>and</strong>communicative, social, <strong>and</strong> school competences. Low language competence hasbeen conventionally <strong>and</strong> operationally def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> research <strong>in</strong> monol<strong>in</strong>guals aslanguage delays <strong>and</strong> disorders. Empirical studies <strong>in</strong> monol<strong>in</strong>guals published <strong>in</strong> thelast decade have shown the high true comorbidity of childhood language disorders<strong>and</strong> psychiatric disorders. 95–99 Longitud<strong>in</strong>al studies show that the presence ofa language disorder predicts greater severity or prevalence of (1) attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) <strong>and</strong> externaliz<strong>in</strong>g disorders, (2) learn<strong>in</strong>g disorders,

<strong>Language</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Adaptation</strong> 703<strong>and</strong> (3) <strong>in</strong>ternaliz<strong>in</strong>g disorders (anxiety <strong>and</strong> depression). 97 A systematic review 37 <strong>in</strong>dicatesthat language deficits forecast both externaliz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternaliz<strong>in</strong>g problems, butthat the risk for externaliz<strong>in</strong>g problems is significantly higher. Moreover, receptive deficitsare considered to be the most potent risk factors <strong>and</strong> specifically associated withdim<strong>in</strong>ished social competence, <strong>and</strong> aggressive <strong>and</strong> disruptive behavior outcomes. 96To be sure, nonpathologic psychosocial outcomes are of importance <strong>in</strong> underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gthe impact of language <strong>in</strong> children. <strong>Language</strong> competence predicts social competence,literacy skills, <strong>and</strong> school achievement.Some pathways from language competence to adaptation <strong>and</strong> maladaptationChild language competence has <strong>in</strong>ternal <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpersonal functions relevant foradaptation. In the <strong>in</strong>ternal sphere, language competence is a major tool for emotional,behavioral <strong>and</strong> cognitive self-regulation. 100 For <strong>in</strong>stance, private speech, the subvocalizedtransition from external speech to <strong>in</strong>ternal speech, proposed by Vygotsky ashelpful to promote task-related behavior, seems to play an ample role <strong>in</strong> cognitive,behavioral, <strong>and</strong> emotional self-regulation. 101–103 Semantic competence <strong>in</strong> label<strong>in</strong>g ofemotions plays an important role <strong>in</strong> the regulation of emotional <strong>and</strong> affective states,as well as <strong>in</strong> practical tasks <strong>and</strong> schoolwork. Basic language processes underlieliteracy <strong>and</strong> math, <strong>and</strong> subsequent school achievement. Narrative competencesparticipate <strong>in</strong> self-image regulation <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the organization of a personal history ascont<strong>in</strong>uous <strong>and</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>gful. A solid <strong>in</strong>ner narrative can be used as a template to forecast<strong>and</strong> lend cohesion to one’s future states <strong>and</strong> reactions. Specific aspects oflanguage, such as the development of a theory of the m<strong>in</strong>d (as <strong>in</strong>dicated by the emergenceof narratives conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g evaluative references to others), help the child topredict others’ reactions <strong>and</strong> to anticipate consequences. Similarly, certa<strong>in</strong> languagedoma<strong>in</strong> competences (for <strong>in</strong>stance, grammatical development of verb tenses, lexicalacquisition of categories or superord<strong>in</strong>ates, narrative development of temporalanchor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> sequence cha<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> conversational skills that <strong>in</strong>itiate <strong>and</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>topics) help move beyond the here <strong>and</strong> now, aid<strong>in</strong>g with gratification <strong>and</strong> impulsedelay.In the <strong>in</strong>terpersonal sphere, language competence is a major tool for social communication,crucial for the social navigation of the outside world, school, friendships, <strong>and</strong>family life. 104 Pragmatic language skills allow for better gaug<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> f<strong>in</strong>e tun<strong>in</strong>g of theexchange with the environment. Verbal humor <strong>and</strong> verbal aggression are a constant ofchild language used to negotiate hierarchies <strong>and</strong> other roles with peers. 104 The abilityto narrate is a basic substrate of many other social skills, such as the ability to makenew friends. Communicative competence is also necessary for self-agency with<strong>in</strong> thefamily system, to negotiate with the parent <strong>and</strong> with<strong>in</strong> the sibl<strong>in</strong>g subsystems.Communicative competence is also essential to elicit emotional responses, praise<strong>and</strong> useful feedback, to defend one’s viewpo<strong>in</strong>t, <strong>and</strong> to help <strong>in</strong> process<strong>in</strong>g stressful<strong>and</strong> pathogenic events. In summary, theoretical <strong>and</strong> empirical consideration po<strong>in</strong>t toways specific aspects of language may underlie enhanced attentional, emotional,cognitive, affective, <strong>and</strong> behavioral function<strong>in</strong>g.Low language competence: mechanisms <strong>and</strong> pathways to psychopathology <strong>and</strong>adaptation <strong>in</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>gual childrenSome <strong>in</strong>trapsychic <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpersonal implications of language for adaptation arespecific to dual language children. Proficiency <strong>in</strong> 2 languages can be a promoter ofcognitive <strong>and</strong> other development. Balanced bil<strong>in</strong>gualism (def<strong>in</strong>ed as age-appropriatecompetences of 2 languages) <strong>and</strong> successful L2 acquisition are associated with, <strong>and</strong>may be determ<strong>in</strong>ants of, growth <strong>in</strong> a host of verbal <strong>and</strong> nonverbal cognitive skills, such

704Toppelberg & Coll<strong>in</strong>sas metal<strong>in</strong>guistic awareness, concept formation, creativity, <strong>and</strong> cognitive flexibility(<strong>in</strong>trapsychic aspects). 105,106 Balanced bil<strong>in</strong>gualism is also associated with sociocultural(<strong>in</strong>terpersonal) <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic advantages. 107 The cognitive <strong>and</strong> other advantagesmay, <strong>in</strong> turn, result <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased adaptation <strong>and</strong> low risk for psychopathology. L1competence plays an important role <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternal label<strong>in</strong>g of emotions, regulation of <strong>in</strong>nerstates, <strong>and</strong> family function<strong>in</strong>g. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to a rich case study literature, each languagehas a differential emotional valence, <strong>and</strong> the first language (mother’s tongue) encodes<strong>and</strong> labels the first emotions <strong>and</strong> regulates early mental states. 108 In this way, poor L1may lead to emotional dysregulation (<strong>in</strong>ternal sphere). At home, <strong>in</strong>tact <strong>in</strong>terpersonalcommunication modulates behavior <strong>and</strong> emotions 109 ; hence, poor L1 may result <strong>in</strong>difficulties <strong>in</strong> family communication <strong>and</strong> loss of its protective functions, 100 which <strong>in</strong>turn may add to maladaptation. As Wong Fillmore states “When parents are unableto talk to their children, they cannot easily convey to them their values, beliefs, underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gs,or wisdom about how to cope with their experiences.” 62<strong>Language</strong> competence is also a predictor of social competence <strong>and</strong> schoolachievement. Interpersonally, poor language skills often predict poor social skills <strong>in</strong>monol<strong>in</strong>guals as well as <strong>in</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>guals. Social competence <strong>and</strong> communicative competenceare correlated. 110 <strong>Language</strong>-delayed children are often poorly socialized, 111shy, aloof, or less outgo<strong>in</strong>g. 112 Their peer <strong>in</strong>teractions are shorter <strong>and</strong> they <strong>in</strong>frequently<strong>in</strong>itiate them. 113 Their peers do not accept them well. 114 Longitud<strong>in</strong>al studies confirmthese same l<strong>in</strong>ks. 115 Communicative competence <strong>and</strong> social competence are alsocorrelated <strong>in</strong> L2-learn<strong>in</strong>g children; children with poor L2 mastery are treated as babies,not spoken to <strong>and</strong> often ignored by their peers. 113,116 In turn, social <strong>in</strong>competencemay lead to behavioral, mood, <strong>and</strong> anxiety problems. Moreover, L2 competencesupports the child’s <strong>in</strong>trapsychic emotional/behavioral regulation <strong>and</strong> access to <strong>in</strong>terpersonalresources (eg, praise by teachers <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g rules, schoolwork, <strong>and</strong>expectations). Communication rendered <strong>in</strong>effectual by low second-language skillsmay lead to the unmask<strong>in</strong>g or emergence of psychopathology. The authors arguethat good language skills predict growth <strong>in</strong> social adaptation <strong>and</strong> low risk of psychopathology.In addition, poor L2 skills <strong>in</strong>terfere with academic performance <strong>and</strong> predictpoor educational outcomes, which, <strong>in</strong> turn, feed <strong>in</strong>to a cycle of maladjustment <strong>and</strong>poor behavioral/emotional outcomes. In a cl<strong>in</strong>ical study of psychiatrically referredLat<strong>in</strong>o bil<strong>in</strong>gual children, levels of academic language proficiency were extremelylow, with classroom language dem<strong>and</strong>s considered to be extremely difficult to impossiblefor 40% of the children <strong>in</strong> at least 1 language, <strong>and</strong> for 19% <strong>in</strong> either language. 117Empirical evidence for an association between low dual language competence <strong>and</strong>psychopathologyA basic question is whether language disorders are associated with psychopathology<strong>in</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>gual children as they are <strong>in</strong> monol<strong>in</strong>gual children. In a study of Lat<strong>in</strong>o duallanguagechildren consecutively referred to a child psychiatry cl<strong>in</strong>ic, estimated prevalenceof language deficits (48%) <strong>and</strong> disorders (41%) was high, with most casesbe<strong>in</strong>g of the mixed receptive-expressive type. 94 These prevalences were found tobe comparable to prior studies <strong>in</strong> monol<strong>in</strong>gual children. 98 A second question iswhether levels of dual language competence are associated with psychiatric symptomseverity. Several analyses of the same sample addressed this question. In a subgroupof children with cl<strong>in</strong>ically significant emotional/behavioral problems, the correlationsbetween a composite of dual language competences <strong>and</strong> psychiatric scoresexpla<strong>in</strong>ed 45% of the variance <strong>in</strong> total, del<strong>in</strong>quency, <strong>and</strong> social problems, <strong>and</strong> approximately20% to 33% <strong>in</strong> externaliz<strong>in</strong>g, aggression, thought, <strong>and</strong> attention problems,with most associations rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g significant after controll<strong>in</strong>g for the most relevant

<strong>Language</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Adaptation</strong> 705confounds. 94 In a different set of analyses, levels of language competence <strong>in</strong> bothlanguages correlated to psychiatric symptom severity, expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g an average of38% (range 28%–46%) of the variance <strong>in</strong> total, social, thought, attentional, del<strong>in</strong>quency,<strong>and</strong> aggression problems, with no significant decrease when adjusted forrelevant control variables. A third set of related questions is (1) whether the languagecompetences <strong>in</strong> each language act as a unit or <strong>in</strong>dependently when it comes to theirassociations with psychopathology <strong>and</strong> (2) whether one language is more importantthan the other when it comes to the relation of language competence <strong>and</strong> psychopathology.In the previous cl<strong>in</strong>ical study, the associations between psychopathology <strong>and</strong>language competence <strong>in</strong> each language were <strong>in</strong>dependent from each other, so thateach language expla<strong>in</strong>ed, overall, as much variance <strong>in</strong> psychopathology as the other,but the variances expla<strong>in</strong>ed did not overlap, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that each language plays animportant role, but that the roles are differentiable, <strong>and</strong> that low competence <strong>in</strong> onelanguage only (eg, English dom<strong>in</strong>ance) would be associated with psychiatric severity<strong>in</strong> this cl<strong>in</strong>ical sample. 118 To avoid the impact of selection bias <strong>in</strong> a cl<strong>in</strong>ically referredsample, these relations were studied <strong>in</strong> a community-based study of young Lat<strong>in</strong>o,dual language children recruited from urban public schools (n 5 228; mean age: 6years). Unpublished prelim<strong>in</strong>ary analyses of this cohort suggest the same f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsof <strong>in</strong>dependent <strong>and</strong> robust negative associations of language competences <strong>in</strong> eachlanguage with levels of psychiatric symptoms; associations rema<strong>in</strong>ed significant afterrelevant controls. 119 In this same community cohort, Spanish <strong>and</strong> English languagecompetences also accounted for moderate to large portions of variance <strong>in</strong> multipledimensions of emotional <strong>and</strong> behavioral wellbe<strong>in</strong>g. 120In terms of other l<strong>in</strong>guistic communities, adjust<strong>in</strong>g to a new culture <strong>and</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gEnglish language skills is significantly <strong>and</strong> substantially associated to immigrants’home country of orig<strong>in</strong>, even after controll<strong>in</strong>g for factors related to SES. 83 One potentialreason is the l<strong>in</strong>guistic distance between immigrants’ first language <strong>and</strong> English, 121affect<strong>in</strong>g the time it takes to learn the new language as a function of the distancebetween the language structure of L1 <strong>and</strong> L2. One could speculate that higherdem<strong>and</strong>s are present for languages that are more distant, <strong>in</strong> turn affect<strong>in</strong>g adaptation,although no empirical studies have, to the authors’ knowledge, explored this question.DIFFERENCES BETWEEN DUAL-CULTURE ACQUISITION AND DUAL LANGUAGEACQUISITIONSecond culture contact may result <strong>in</strong> challeng<strong>in</strong>g or overwhelm<strong>in</strong>g dem<strong>and</strong>s, knownas acculturative stress. Second culture contact <strong>and</strong> second language contact oftenco-occur, so that acculturative dem<strong>and</strong>s overlap with language dem<strong>and</strong>s. However,each one sets <strong>in</strong> motion different specialized responses. Acculturative dem<strong>and</strong>s aremet by the immigrant’s vary<strong>in</strong>g degrees of bicultural competence, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> biculturalor monocultural adaptation (or maladaptation) with their mental health implications.122,123 Monocultural adaptation results from the immigrant’s exclusiveadoption of the second, ma<strong>in</strong>stream culture (assimilation) or of the ethnic, homeculture (ethnic monocultural affiliation). Of the various proposed models of secondculture acquisition, bicultural adaptation is considered, by the literature on m<strong>in</strong>oritychildren <strong>and</strong> adults, the healthiest <strong>and</strong> most successful overall outcome, result<strong>in</strong>gfrom the ability to develop <strong>and</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> competence <strong>in</strong> both cultures. 122–124 Incontrast, language dem<strong>and</strong> is met by the child’s current dual language competence,his capacity to acquire languages, <strong>and</strong> specific protective resources support<strong>in</strong>g thechild (l<strong>in</strong>guistically <strong>and</strong> emotionally) <strong>in</strong> the process of second-language acquisition.

706Toppelberg & Coll<strong>in</strong>sCross-cultural research on immigrants documents large contributions of languagecompetence to variance <strong>in</strong> acculturation 123 <strong>and</strong> low language competence as a determ<strong>in</strong>antof acculturative stress 122 <strong>and</strong> poor social <strong>and</strong> educational outcomes. 30 Acculturativestress appears to be associated with psychopathology <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong>o youth, 19 <strong>and</strong>language conflict may expla<strong>in</strong> a good portion of the impact of acculturative stress. 125Bicultural competence of the child <strong>and</strong> family may have a protective effect, favor<strong>in</strong>gbicultural adaptation. In the discussion that follows, the authors justify their particularfocus on dual language competence by view<strong>in</strong>g it as closely connected to but differentiablefrom other components of bicultural competence.Cultural Competence <strong>in</strong> Bicultural IndividualsBicultural competence is considered the optimal outcome of the acculturation/dualculture acquisition process <strong>and</strong> is conceptualized as a multidimensional, heterogeneousconstruct. 124 The follow<strong>in</strong>g component dimensions of bicultural competencehave been proposed: (1) language competence, (2) knowledge of cultural beliefs<strong>and</strong> values, (3) positive attitudes toward both majority <strong>and</strong> m<strong>in</strong>ority groups, (4) biculturalefficacy, (5) role repertoire, <strong>and</strong> (6) a sense of be<strong>in</strong>g grounded (ie, hav<strong>in</strong>g supportnetworks <strong>in</strong> both cultures). 124 Thus, language competence is considered a majorbuild<strong>in</strong>g block of bicultural competence; when L2 acquisition is accompanied bysupport of L1 ma<strong>in</strong>tenance, as shown by the research on bil<strong>in</strong>gual programs, biculturalcompetence is promoted. Other research suggests that language competenceexpla<strong>in</strong>s most of the variance <strong>in</strong> acculturation, 123 <strong>and</strong> views its deficits as strong determ<strong>in</strong>antof acculturative stress 122 <strong>and</strong> as a risk factor. 30 In the authors’ conceptualization,be<strong>in</strong>g able to communicate <strong>in</strong> the language of both worlds maximizes the child’scapacity to draw upon available protective resources, while at the same time itenables an adaptive response to the language dem<strong>and</strong>. Conversely, nonl<strong>in</strong>guisticaspects of bicultural competence <strong>in</strong> the child, family, <strong>and</strong> extended social environmenthave an important protective role <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong>o children of immigrants, support<strong>in</strong>glanguage <strong>and</strong> cultural acquisition <strong>and</strong> m<strong>in</strong>imiz<strong>in</strong>g distress.Dual language competence can <strong>and</strong> should be explicitly differentiated from othernonl<strong>in</strong>guistic components of cultural competence, s<strong>in</strong>ce it has a unique <strong>and</strong> centralrole with<strong>in</strong> the broader construct, <strong>and</strong> its own constra<strong>in</strong>ts, qualities, <strong>and</strong> complexitiesthat set it apart from other dimensions <strong>in</strong> the bicultural competence construct. Duallanguagecompetence is differentiable from other elements of bicultural competence<strong>in</strong> at least the follow<strong>in</strong>g 5 ways. First, the l<strong>in</strong>guistic systems mobilized <strong>in</strong> L2 <strong>and</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>gualacquisition are <strong>in</strong>dependent <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>volve specific strategies. Second, acculturativestress is fully conceivable <strong>and</strong> observed even <strong>in</strong> the absence of languagebarriers, such as <strong>in</strong> the case of nonimmigrant m<strong>in</strong>orities. Third, although biculturaladaptation may ideally tend to compromise as a way of resolv<strong>in</strong>g cultural conflict,the conflicts between discrepant l<strong>in</strong>guistic systems (eg, Spanish allows flexibility <strong>in</strong>subject-verb-object order, whereas English is rather rigid) are ideally resolved by fullydifferentiat<strong>in</strong>g the 2 languages. In bil<strong>in</strong>gual acquisition, solutions of compromise areonly transient, <strong>in</strong>termediate steps. In other words, bicultural adaptation tends towardsynthesis <strong>and</strong> compromise as an end result, while bil<strong>in</strong>gual acquisition progressestoward language-system <strong>in</strong>dependence, albeit often <strong>in</strong>complete. Fourth, immigrantscan ga<strong>in</strong> knowledge of target cultural beliefs <strong>and</strong> values or a positive attitude moreeasily <strong>and</strong> quickly than they can ga<strong>in</strong> the experiences that support L2 acquisition<strong>and</strong> L1 ma<strong>in</strong>tenance. Because of globalization <strong>and</strong> penetration of American ma<strong>in</strong>streamculture <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> America, many nonimmigrant Lat<strong>in</strong> Americans develop knowledgeof American cultural beliefs without ever sett<strong>in</strong>g foot on American soil. Fifth,although positive attitudes toward American culture are part of the motivation beh<strong>in</strong>d

<strong>Language</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Adaptation</strong> 707voluntary immigration to the United States, few adult <strong>and</strong> adolescent first-generationimmigrants (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g highly motivated ones) become nativelike speakers of English.Group analyses show associations among various component bicultural dimensions,but stratification will likely show <strong>in</strong>dividual differences, such as a strong monoculturalidentity with high bil<strong>in</strong>gual competence, or strong bicultural knowledge of culturalbeliefs without accompany<strong>in</strong>g bil<strong>in</strong>gual competence.CLINICAL AND POLICY IMPLICATIONSDual language children often enter school with a wide variability of competences <strong>in</strong>their L1 <strong>and</strong> L2, <strong>and</strong> a large proportion of these children have low competences <strong>in</strong> 1or both languages. However, many are able to meet developmental expectationsdur<strong>in</strong>g the first 2 years of school. Lat<strong>in</strong>o children of immigrants often grow up <strong>in</strong>l<strong>in</strong>guistic isolation, enter school at a disadvantage, <strong>and</strong> experience <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gacademic achievement gaps <strong>and</strong> mental health disparities over time. From a developmentalperspective, the authors can suggest that support<strong>in</strong>g the development of bothL1 <strong>and</strong> L2, especially dur<strong>in</strong>g the transition from home to school, is developmentallybeneficial.It is imperative that cl<strong>in</strong>icians <strong>and</strong> specialists underst<strong>and</strong> the importance of recogniz<strong>in</strong>gthe wide range of language competences young children of immigrants have <strong>in</strong>their L1 <strong>and</strong> L2. By better underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g normal <strong>and</strong> abnormal dual language development,we can develop <strong>in</strong>tervention strategies to target language delays as soonas possible while also support<strong>in</strong>g the development of both languages.Ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g (or not) the Two <strong>Language</strong>s <strong>in</strong> <strong>Children</strong> with <strong>Language</strong><strong>and</strong> Other DeficitsMa<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the first language is important for guarantee<strong>in</strong>g access to family <strong>and</strong>community supports <strong>and</strong> protective factors. There has been a poorly substantiatedbut unfortunately common practice of recommend<strong>in</strong>g to parents that they discont<strong>in</strong>ueexposure to one of the languages (typically the home language) when a child is fac<strong>in</strong>gcognitive, language, or learn<strong>in</strong>g delays, without consideration of the social <strong>and</strong> familyconsequences of this recommendation. This practice has little or no empirical support,<strong>and</strong> some research suggests that children with language impairment can be healthilyexposed to <strong>and</strong> learn 2 languages, 43 even with benign manifestations of languageimpairment <strong>in</strong> both languages. It may be true, nonetheless, that for <strong>in</strong>dividual childrenwith language deficits or disorders, the additional cognitive <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic dem<strong>and</strong>s ofdual language learn<strong>in</strong>g may become overwhelm<strong>in</strong>g. A cl<strong>in</strong>ical recommendation to discont<strong>in</strong>ueexposure to one of the languages <strong>in</strong> children who are struggl<strong>in</strong>g withlanguage learn<strong>in</strong>g or learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> general, or who express distress or overload on exposureto a language may then be necessary, but it is nonetheless a serious decisionthat, because of its last<strong>in</strong>g consequences, should not be made lightly. 126 Such decisionsshould ideally <strong>in</strong>volve a speech/language pathologist with expertise <strong>in</strong> assess<strong>in</strong>gdual language children, consultation with the parents <strong>and</strong> others who know the childwell, <strong>and</strong> an <strong>in</strong>formed decision process by the parents with consideration to the family’splans for the future. 126 For <strong>in</strong>stance, it may be crucial to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> Spanish, fora child whose immigrant family ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s firm ties with the home country or oldermembers of the family, or as a way to prevent family distanc<strong>in</strong>g caused by poorcommunication. 127 When recommendations are made about ab<strong>and</strong>on<strong>in</strong>g one of thelanguages, the l<strong>in</strong>guistic ability of the parents <strong>and</strong> family should be considered. It isimportant to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> the richness of the l<strong>in</strong>guistic environments of the child. 128

708Toppelberg & Coll<strong>in</strong>sInstruct<strong>in</strong>g parents to switch to English at home, when they do not master thislanguage, is ill advised <strong>and</strong> possibly counterproductive <strong>in</strong> most situations.Suspect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Diagnos<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Language</strong> Disorders <strong>in</strong> Dual <strong>Language</strong> <strong>Children</strong>Of considerable concern with the large <strong>and</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g dual language population is howto properly recognize normal <strong>and</strong> abnormal dual language development. Both theoverdiagnosis as well as the underdiagnosis of language delays of English-languagelearners is a persistent problem. 129–132 There is a press<strong>in</strong>g need for st<strong>and</strong>ard guidel<strong>in</strong>es<strong>in</strong> underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g normal <strong>and</strong> abnormal dual language development when us<strong>in</strong>gthe current tests <strong>and</strong> norms recommended for assess<strong>in</strong>g oral-language competence.133 An ongo<strong>in</strong>g problem with the diagnosis of language delays <strong>in</strong> dual languagechildren is that children’s English competences are often the only ones assessed. Thispractice renders it impossible to differentiate children who have not yet had the opportunityor the time to learn English (eg, Spanish dom<strong>in</strong>ant) from those that are notmak<strong>in</strong>g significant ga<strong>in</strong>s despite adequate exposure because of impairments <strong>in</strong> theirlanguage-acquisition ability. A language disorder should be suspected <strong>in</strong> a duallanguage child, when the child is reported to be significantly beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong> the underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gof both languages, when there has been significant exposure to bothlanguages, <strong>and</strong> when there are language-based learn<strong>in</strong>g problems. Although it hasbeen clearly documented that bil<strong>in</strong>gualism does not cause language delay or languagedisorder, 128 language disorders are certa<strong>in</strong>ly possible <strong>in</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>gual children <strong>and</strong> suchpossibility should not be easily dismissed, <strong>and</strong> apparent delays should not <strong>in</strong>steadbe misattributed to the child’s bil<strong>in</strong>gual condition. Auditory-verbal work<strong>in</strong>g memorydeficits associated with ADHD 134 or a language disorder 135 may slow down the acquisitionof a second language.Dual <strong>Language</strong> AssessmentDual language assessment is a complex task <strong>and</strong> some important conceptual <strong>and</strong>empirical progress has occurred <strong>in</strong> the last years 92,93,136 to dist<strong>in</strong>guish betweenlanguage delays <strong>and</strong> normal dual language developmental variability. 136,137 The fieldof language pathology has made headway <strong>in</strong> the area of determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g dual languagecompetence. 133,136,138 Although research on the normal dual language developmenthas used normed st<strong>and</strong>ardized measures of language competence developed formonol<strong>in</strong>guals, 139–141 there are no widely accepted, normed st<strong>and</strong>ardized assessmentsof dual language competence exclusively for bil<strong>in</strong>gual children. Instead, parallelmeasures of language competence available <strong>in</strong> multiple languages have been used.Dual language children with a regular <strong>and</strong> rich exposure to both languages exhibitsimilar developmental patterns <strong>and</strong> milestones as monol<strong>in</strong>guals <strong>in</strong> terms of the orderof acquisition of l<strong>in</strong>guistic structures. 58,142,143 The <strong>in</strong>terpretation of normed st<strong>and</strong>ardizedscores of language assessments with monol<strong>in</strong>gual populations can be usedcautiously as a reference po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> the assessment of dual language children <strong>and</strong> asan <strong>in</strong>dicator of reasonable approximation of age-appropriate language competence.133 Dual language children <strong>in</strong> the transitional process of language acquisitiontypically fall short of the monol<strong>in</strong>gual normal 48,144,145 because of the distributive natureof dual language acquisition (eg, vocabulary related to school is stronger <strong>in</strong> English,whereas that related to home is stronger <strong>in</strong> Spanish). 46 Grammatical <strong>and</strong> otherlanguage errors made by a child learn<strong>in</strong>g a second language or a second English dialect(such as st<strong>and</strong>ard American English) should not be confused with the grammaticalor lexical abnormalities of language disorders. Specialized early speech/languageassessment <strong>in</strong> 2 languages is often necessary to differentiate normal dual languageacquisition from language disorder. 136,146

<strong>Language</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Adaptation</strong> 709Silent Period <strong>and</strong> Selective Mutism<strong>Children</strong> who are suddenly immersed <strong>in</strong> a second-language environment with noknowledge of the language, particularly young children, will normally go througha nonverbal period limited to the second language, 116 which should not be confusedwith selective mutism. 147 Although sudden immersion <strong>and</strong> its nonverbal period can bestressful depend<strong>in</strong>g on environmental support <strong>and</strong> the temperamental characteristicsof the child, selective mutism typically lasts longer, appears <strong>in</strong> both languages <strong>and</strong>unfamiliar situations, <strong>and</strong> tends to be disproportionate <strong>in</strong> relation to the child’slanguage exposure <strong>and</strong> competence. 147 The prevalence of selective mutism appearsto be, however, higher among immigrant dual language children, <strong>and</strong> it is thus importantthat the cl<strong>in</strong>ician be familiar with features that differentiate selective mutism fromthe normal nonverbal period. 147Educational ImplicationsIt is important that educational approaches <strong>and</strong> policies recognize the <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gdiversity <strong>in</strong> today’s schools <strong>and</strong> establish a connection between home <strong>and</strong> schoolby <strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g aspects of the home <strong>and</strong> community <strong>in</strong>to the curriculum. For duallanguagechildren of immigrants, adequately function<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> 2 languages at home<strong>and</strong> school may be associated with their wellbe<strong>in</strong>g. 120 Support<strong>in</strong>g the developmentof both L1 <strong>and</strong> L2 at school may prove to be beneficial to children’s l<strong>in</strong>guistic, psychosocial,<strong>and</strong> academic development. Future policy decisions <strong>and</strong> educational practiceshould reflect the importance of the development of L1 <strong>and</strong> L2 competences <strong>in</strong>multiple doma<strong>in</strong>s of children’s wellbe<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> academic progress.SUMMARYThe study of dual language acquisition <strong>and</strong> how its developmental trajectories impactsthe overall wellbe<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> mental health of the immigrant child is <strong>in</strong> its early stages, 148requir<strong>in</strong>g further major empirical <strong>and</strong> theoretical work. Nonetheless, several importantimplications can be derived from extant developmental <strong>and</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical research: (1) Decisionsabout discont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g learn<strong>in</strong>g or exposure to one of the languages should not bemade lightly <strong>and</strong> should consider the personal <strong>and</strong> family circumstances of the child;(2) Delays <strong>in</strong> language acquisition can be formally evaluated without prematurely dismiss<strong>in</strong>gthem as normal <strong>in</strong> bil<strong>in</strong>gual children. Assessments are available that allow forevaluation of bil<strong>in</strong>gual children; (3) A complete language assessment will often requiretest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> both languages; (4) The brief, normal, nonverbal period <strong>in</strong> second-languageacquisition can <strong>and</strong> should be differentiated form selective mutism; <strong>and</strong> (5) Educational,cl<strong>in</strong>ical, <strong>and</strong> family efforts to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> support the development of competence<strong>in</strong> the 2 languages of the dual language child may prove reward<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> terms oflong-term wellbe<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> mental health, <strong>and</strong> educational <strong>and</strong> cognitive benefits. Theseconsiderations are critical for cl<strong>in</strong>icians <strong>and</strong> practitioners work<strong>in</strong>g with the most rapidlygrow<strong>in</strong>g segment of the US child population, dual language children of immigrants.ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThe first author expresses his special gratitude to his late mentor, Stuart Hauser,MD, PhD, who provided him with <strong>in</strong>spiration, <strong>in</strong>sight, <strong>and</strong> support over many yearsof work<strong>in</strong>g together.

710Toppelberg & Coll<strong>in</strong>sREFERENCES1. Capps R, Capps R, Fix ME, et al. The health <strong>and</strong> well-be<strong>in</strong>g of young children ofimmigrants. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC: The Urban Institute; 2005.2. Suárez-Orozco C, Suárez-Orozco MM. <strong>Children</strong> of immigration. Cambridge(MA): <strong>Harvard</strong> University Press; 2001.3. Mather M. <strong>Children</strong> <strong>in</strong> immigrant families chart new path. PRB Reports on America.Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC: Population Reference Bureau; 2009.4. U.S. Census: The 2002, 2003, <strong>and</strong> 2005 U.S. Current Population Survey, AnnualDemographic <strong>and</strong> Economic Supplement, March: 2006. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC:Census of Population; 2006.5. Zehler AM, Fleischman HL, Hopstock PJ, et al. Descriptive Study of Services toLimited English Proficient (LEP) Students <strong>and</strong> LEP Students with Disabilities,vol. I. Research Report. Arl<strong>in</strong>gton (VA): Development Associates, Inc; 2003.6. Fry R, Passel J. Lat<strong>in</strong>o children: a majority are US-born offspr<strong>in</strong>g of immigrants.Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC: Pew Research Center; 2009.7. Suro R, Passel JS. The rise of the second generation: chang<strong>in</strong>g patterns <strong>in</strong>Hispanic population growth. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2003.8. Flores G, Fuentes-Afflick E, Barbot O, et al. The health of Lat<strong>in</strong>o children: urgentpriorities, unanswered questions, <strong>and</strong> a research agenda. JAMA 2002;288:82.9. Adelman L. Unnatural causes: is <strong>in</strong>equality mak<strong>in</strong>g us sick? Prev Chronic Dis2007;4(4). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2007/oct/07_0144.htm.Accessed March 5, 2010.10. Hern<strong>and</strong>ez DJ. Child development <strong>and</strong> the social demography of childhood.Child Dev 1997;68:149.11. Hern<strong>and</strong>ez DJ, Denton NA, Macartney SE. <strong>Children</strong> <strong>in</strong> immigrant families —theU.S. <strong>and</strong> 50 States: national orig<strong>in</strong>s, language, <strong>and</strong> early education. Albany(NY): University at Albany, SUNY; 2007.12. Perreira K, Harris K, Lee D. Mak<strong>in</strong>g it <strong>in</strong> America: high school completion byimmigrant <strong>and</strong> native youth. Demography 2006;43:511.13. Suárez-Orozco C, Suárez-Orozco MM, Todorova I. Learn<strong>in</strong>g a new l<strong>and</strong>: immigrantstudents <strong>in</strong> American Society. Cambridge (MA): <strong>Harvard</strong> University Press;2008.14. Eaton DK, Kann L, K<strong>in</strong>chen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance–UnitedStates, 2005. MMWR Surveill Summ 2006;55:1.15. Grunbaum JA, Kann L, K<strong>in</strong>chen SA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2001. J Sch Health 2002;72:313.16. Zayas L, Lester R, Cabassa L, et al. Why do so many lat<strong>in</strong>a teens attemptsuicide? A conceptual model for research. Am J Orthop 2005;75:275.17. Reardon-Anderson J, Capps R, Fix ME. The health <strong>and</strong> well-be<strong>in</strong>g of children <strong>in</strong>immigrant families, <strong>in</strong> ”new federalism: national survey of america’s families.Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC: Urban Institute; 2002. p. 1.18. Alegría M, Mulvaney-Day N, Torres M, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disordersacross lat<strong>in</strong>o subgroups <strong>in</strong> the United States. Am J Public Health 2007;97:68.19. Can<strong>in</strong>o G, Roberts RE. Suicidal behavior among Lat<strong>in</strong>o youth. Suicide LifeThreat Behav 2001;31:122.20. Orfield G, Losen D, Wald J, et al. Los<strong>in</strong>g our future: how m<strong>in</strong>ority youth are be<strong>in</strong>gleft beh<strong>in</strong>d by the graduation rate crisis. The Civil Rights Project at <strong>Harvard</strong>University. Contributors: advocates for children of New York. Cambridge (MA):The Civil Society Institute; 2004.

<strong>Language</strong>, <strong>Culture</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Adaptation</strong> 71121. President’s Advisory Commission on Educational Excellence for Hispanic Americans.F<strong>in</strong>al report: from risk to opportunity: fulfill<strong>in</strong>g the educational needs ofhispanic americans <strong>in</strong> the 21st century. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton DC: White House Initiativeon Educational Excellence for Hispanic Americans; 2003.22. Villarruel FA, Walker NE. “Donde esta la justicia?” A call to action on behalf ofLat<strong>in</strong>o <strong>and</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong>a youth <strong>in</strong> the U.S. justice system. Build<strong>in</strong>g blocks for youth.San Francisco (CA): Center on Juvenile & Crim<strong>in</strong>al Justice; 2002.23. Fuligni AJ. A comparative longitud<strong>in</strong>al approach to acculturation. Harv EducRev 2001;71:566.24. Masten AS. Resilience <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual development: Successful adaptationdespite risk <strong>and</strong> adversity. In: Wang MC, Gordon EW, editors. Educational resilience<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ner-city America: challenges <strong>and</strong> prospects. Hillsdale (NJ): LawrenceErlbaum Associates; 1994. p. 3.25. Suárez-Orozco C. Commentary. In: Suárez-Orozco MM, Paez MM, editors.Lat<strong>in</strong>os: remak<strong>in</strong>g America. London (Engl<strong>and</strong>): University of California Press;2002. p. 302.26. Perez M, Rodriguez J, Wisdom JP, et al. Trauma treatment outcome amongculturally diverse Lat<strong>in</strong>o children <strong>and</strong> adolescents. Paper presented at Criticalissues <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong>o mental health. New Brunswick (NJ), June 9, 2009.27. Pumariega A. Acculturation <strong>and</strong> mental health <strong>in</strong> adolescents. Paper presentedat AACAP Annual Meet<strong>in</strong>g. Honolulu, Hawaii, October 31, 2009.28. Alegria M, Sribney W, Woo M, et al. Look<strong>in</strong>g beyond nativity: the relation of ageof immigration, length of residence, <strong>and</strong> birth cohorts to the risk of onset ofpsychiatric disorders for Lat<strong>in</strong>os. Res Hum Dev 2007;4:19.29. Garcia-Coll C. The immigrant paradox <strong>in</strong> child <strong>and</strong> adolescent development.Paper presented at CUNY Graduate Center Lat<strong>in</strong>o/a <strong>and</strong> Caribbean PsychologyColloquium. New York (NY), 2008.30. Hern<strong>and</strong>ez DJ, Charney E, editors. From generation to generation: the health<strong>and</strong> well-be<strong>in</strong>g of children <strong>in</strong> immigrant families. National Research Council<strong>and</strong> Institute of Medic<strong>in</strong>e: Committee on the Health <strong>and</strong> adjustment of immigrantchildren <strong>and</strong> families; board on children, Youth <strong>and</strong> families. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC:National Academy Press; 1998. p. xvii.31. Bankston CL, Zhou M. Be<strong>in</strong>g well us. do<strong>in</strong>g well: self-esteem <strong>and</strong> school performanceamong immigrant <strong>and</strong> nonimmigrant racial <strong>and</strong> ethnic groups. Int MigrRev 2002;36:389.32. Kao G, Thompson JS. Racial <strong>and</strong> ethnic stratification <strong>in</strong> educational achievement<strong>and</strong> atta<strong>in</strong>ment. Annu Rev Sociol 2003;29:417.33. Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Legacies: the story of the immigrant second generation.Berkeley: University of California Press; 2001.34. Alegria M, Can<strong>in</strong>o G, Shrout PE, et al. Prevalence of mental illness <strong>in</strong> immigrant<strong>and</strong> non-immigrant U.S. lat<strong>in</strong>o groups. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:359.35. Berko GJ. The development of language. 3rd edition. New York: Macmillan;1993.36. Hymes D. On communicative competence. Hammondsworth (UK): Pengu<strong>in</strong>; 1972.37. Toppelberg CO, Shapiro T. <strong>Language</strong> disorders: a 10-year research updatereview. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000;39:143.38. Collier V. Acquir<strong>in</strong>g a second language for school, vol. 1. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC:National Clear<strong>in</strong>ghouse for Bil<strong>in</strong>gual Education; 199539. Pan BA. Semantic development: learn<strong>in</strong>g the mean<strong>in</strong>g of words. In: BerkoGleason J, editor. The development of language. 3rd edition. New York: Macmillan;1993. p. 302.