An Orphaned Highway - Central Federal Lands Highway Division

An Orphaned Highway - Central Federal Lands Highway Division

An Orphaned Highway - Central Federal Lands Highway Division

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>An</strong><strong>Orphaned</strong><strong>Highway</strong>Reconstruction andemergency repairs aimto resolve longstandingownership and maintenancetroubles for a historicroadway near Yellowstone.by Michael Kulbacki,Bert McCauley, and Steve Moler(Above) In this panoramic view, aswitchback section of the Beartooth<strong>Highway</strong> climbs toward the 3,345-meter (10,974-foot) Beartooth Passin Montana, making a 1,219-meter(4,000-foot) elevation gain over 16.1kilometers (10 miles). Photo: MDT.Inset: One of the “bear’s teeth” forwhich the Beartooth <strong>Highway</strong> wasnamed is visible along the ridgelinein the center of this photo takenfrom the highway looking intoMontana from the Wyoming side.<strong>An</strong>other bear’s tooth visible fromthe highway is located on BeartoothButte in Wyoming.Awoman planning a summervacation once wrote a letterto CBS travel correspondentCharles Kuralt and asked, “What areAmerica’s most beautiful highways?”As documented in his 1979 bookDateline America, Kuralt answered,“The most beautiful road in Americais U.S. 212”—the Beartooth <strong>Highway</strong>.From the Beartooth’s westernend at the northeastern entranceof Yellowstone National Park to thehighway’s eastern end just outsideRed Lodge, MT, the 108-kilometer(67-mile) Beartooth offers travelersan incredible high-country drivingexperience. The highway crossessome of the most rugged mountainsin the lower 48 States, with 20 peaksmore than 3,600 meters (12,000feet) high. In June 2002, the <strong>Federal</strong><strong>Highway</strong> Administration (FHWA)designated a large portion of thehighway as an All-American Roadbecause of the corridor’s historical,cultural, and scenic significance.Built between 1931 and 1936 as along approach road to Yellowstone,the Beartooth <strong>Highway</strong> today is aneconomic lifeline for the Montana18PUBLIC ROADS • July/August • 2006

Flash’s Photographyresort towns of Cooke City and RedLodge, connecting them on a twolane,roughly crescent-shaped roadwaythat bends southward intoWyoming when viewed from above.About 200,000 people enteredYellowstone through the park’snortheastern gate near Cooke City in2004, most via the highway, accordingto the U.S. Department of theInterior’s National Park Service (NPS).Despite its renown and significanceto the local economy, thehighway has suffered neglect overthe years. Even though the Beartoothcarries visitors to the Nation’s oldestnational park and zigzags throughthree national forests, three counties,and two States, no government agencyhas claimed ownership of largesegments of the roadway throughmuch of its history, earning it thenickname the “orphaned highway.”Since the mid-1990s, however,the FHWA <strong>Federal</strong> <strong>Lands</strong> <strong>Highway</strong><strong>Division</strong> (FLHD) has worked withNPS, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s(USDA) Forest Service,the Montana Department of Transportation(MDT), and other partnerson a major initiative to resolve thehighway’s ownership and maintenanceissues. The goal is to repairand upgrade substandard sections tomeet current State highway standardsso that the relevant countiesor States can adopt the portions ofthe highway within their boundariesinto their road systems, therebyensuring long-term stewardship.Partners acknowledge hurdles inthe endeavor. “It is quite challengingbuilding a project with such controversyregarding ownership,” saysAmong other things, the Beartooth <strong>Highway</strong> was intended to spur tourism andcommerce in Red Lodge, shown here during the Memorial Day parade in 1927.The seven segments of the Beartooth <strong>Highway</strong> designated during the planningfor the reconstruction are shown on this map. Segment 1, to the left, andsegment 4, in the middle, are the focus of the reconstruction, while theswitchback area of segment 5 was the site of May 2005 mudslides andsubsequent emergency repairs that summer.Project Engineer Jason Hahn, whomanages a portion of the projectfor FHWA’s Western <strong>Federal</strong> <strong>Lands</strong><strong>Highway</strong> <strong>Division</strong> (WFLHD), “tryingto figure out for whom you are buildingthe road—the Forest Service, theNational Park Service, or the MontanaDepartment of Transportation.”But, adds Larry Smith, recentlyretired division engineer for FHWA’s<strong>Central</strong> <strong>Federal</strong> <strong>Lands</strong> <strong>Highway</strong> <strong>Division</strong>(CFLHD), interagency cooperationhas been instrumental in constructionand resolving ownership.“The development of solutions forthe future of the Beartooth <strong>Highway</strong>has been successful due to the partnershipdeveloped among the manystakeholders and their drive for success,”he says.Despite the challenges of interagencycooperation and a recentnatural disaster that set the projectback, reconstruction is underway,and the Beartooth may yet find apermanent steward.HistoryThe Beartooth <strong>Highway</strong> came intoexistence after the automobile becamea popular method of traveling toYellowstone, beginning around 1915.The introduction of cars spurred arapid rise in local tourism, with guestPUBLIC ROADS • July/August • 2006 19

A History of Mixed FortunesAlthough the original construction of the Beartooth <strong>Highway</strong> was completed according to schedule andbudget, the fortunes of its contractors were not so uniformly successful. McNutt & Pyle of Eugene, OR,was responsible for the 40.2-kilometer (25-mile) stretch heading up the western slope of the BeartoothPlateau and over Beartooth Pass to the Montana-Wyoming border. The company’s $478,000 bid was$40,000 below the engineering estimate and $200,000 below the only other bid, causing fear in somethat the firm did not know what it was getting into.History proved that the firm underestimated the costs. McNutt & Pyle had only begun working withmechanized equipment 2 years earlier, in 1929, having used horses for power in all its grading contractsuntil then. The company had never worked a project so large and technically complex, or so demandingof qualified workers. It spent $30,000 building a “tote road” from Cooke City to the western end of itsproject to move equipment and supplies. At the same time, the firm had its two excavation teams “walktheir shovels into the project” from Gardiner, MT, 129 kilometers (80 miles) away, observed an incredulousBPR engineer, Harry Mitchell.Mitchell claimed the company would reach Beartooth Lake, roughly the contract’s midpoint, in 30days. But by the end of the first construction season in late 1931, according to Mitchell, the contractorhad “practically demolished” the little equipment it did have on the glacial boulders and solid rock reefsthat lay in the path. Workers would not reach Beartooth Lake for another year.As winter set in, the company continued to house its workers at a temporary camp on Muddy Creek.A large tent became a makeshift mess hall. Many families simply left for fear of freezing to death. Thisfreed up tents for other uses at least, and on one occasion, a work crew drove a truck in need of repairinto a large vacant tent. In keeping with the company’s luck, however, the tent burned to the ground andthe truck was barely saved when a fire lit from old crankcase oil for warmth spread.McNutt & Pyle merged with Washburn & Hall later in the winter. BPR forced a project reorganizationenabling Washburn & Hall managers to supervise McNutt & Pyle workers directly. Mitchell credited thiswith the ability of the firm to finally complete the project.By comparison, the Morrison-Knudsen Company of Boise, ID, was much more efficient. Morrison-Knudsen worked on the difficult switchback area, the 19.3-kilometer (12-mile) section extending from theState line northeast to Quad Creek. The firm also was responsible for an 8-kilometer (5-mile) section fromthe eastern end of the first section to the beginning of the <strong>Federal</strong>-aid portion 13.8 kilometers (8.6 miles)outside Red Lodge in Custer National Forest.Morrison-Knudsen drew on its experience with three large grading projects inside Yellowstone in1929–1931, employing more experienced construction managers and skilled workers than McNutt & Pylehad. The company kept employee morale high by providing good working conditions. Its camp had widestreets, electric lighting, clean and reliable water supplies, and houses that were weatherproofed againstthe cold. A blacksmith shop enabled workers to undertake practically any repair.The Beartooth took its toll on McNutt & Pyle, however, and the company went bankrupt, despitethe merger, soon after completing its work. Some subcontractors on the roadwork went the same way,while other contractors—mainly S. J. Groves & Sons and Winston Brothers Company—at least survived.Morrison-Knudsen, on the other hand, prospered on the Beartooth, becoming a world-class mining,engineering, and construction conglomerate decades later.Flash’s PhotographyIn July 1931, this Grane & Company shovel and truck was helpingin the early stages of construction of the Beartooth.ranches, lodges, and hunting facilitiesbeckoning travelers to come and viewthe scenery and wildlife.The rise in tourism and the needto support the local mining industryincreased demand for better roads.In 1925 the Forest Service andFHWA’s predecessor, the Bureauof Public Roads (BPR), conductedthe first known feasibility studiesfor a new road from Cooke City toRed Lodge.Around this time, groups fromboth towns began lobbying the U.S.Congress to finance an eastern approachto Yellowstone. Finally, inJanuary 1931, President HerbertHoover signed the National ParkApproaches Act, and the RedLodge–Cooke City route was thefirst park road to receive funding.But the law contained general restrictionsthat affected the Beartooth<strong>Highway</strong>. One stricture was that apark approach road could not bemore than 96.6 kilometers (60miles) long. The final Beartoothalignment, however, measured 110.4kilometers (68.6 miles). To coverthe excess mileage, the remaining13.8 kilometers (8.6 miles) to thewest of Red Lodge would be designatedas part of the <strong>Federal</strong>-aid highwaysystem, with another shortportion inside Custer NationalForest placed under the jurisdictionof the forest highway system.Financing was sorted out byspring 1931, with support comingfrom forest highway, <strong>Federal</strong>-aid,and park approach act funding.NPS allocated the first $1 millionfor initial construction of the 96.6kilometers (60 miles) covered underthe park approach act. Montanaconstructed the <strong>Federal</strong>-aid sectionand incorporated it into the Statehighway system.A 1926 NPS-BPR agreement signedduring construction of Glacier NationalPark’s Going-to-the Sun Road hadgiven BPR responsibility for designingand building roads throughout theentire national park system. ThereforeBPR managed the work along thesection of the Beartooth being builtunder the park approach act. Thefirst contracts were let in June 1931,and actual construction began laterthat summer. Despite presentingserious engineering and logisticalchallenges for contractors, the highwaywas completed on time andwithin budget.20PUBLIC ROADS • July/August • 2006

Maintenance Issues RaisedAlthough constructing the highwayprogressed rather smoothly, maintainingit became an entirely differentstory. Snowplowing and removingrockslide debris were immediateconcerns. In 1937, for example, ittook BPR road crews until June 19to clear the road of snow. The followingyear the road opened just afew days earlier, on June 10. Whowould continue such maintenanceover the long term—and who wouldpay for it—became topics of debatein the years following construction.The park approach act was creditedwith making construction ofthe Beartooth possible, but it alsocreated problems. Even though theact authorized NPS to contract formaintenance work, Congress did notprovide additional money for thatpurpose. So NPS urged the MontanaState <strong>Highway</strong> Commission to assumefull responsibility for maintenance,and even pushed legislationgiving Montana authority to maintainthe Wyoming section. NPS reasonedthat the road was a Montana approachto Yellowstone, was built atthe urging of the Montana congressionaldelegation, and connectedtwo Montana communities (RedLodge and Cooke City).Montana, however, argued thatmaintenance responsibility belongedto the <strong>Federal</strong> Government sincethe road was an approach to a nationalpark. In the end, the <strong>Federal</strong>Government agreed to do minimalmaintenance such as snowplowingand landslide clearing alongthe entire route except the final13.8-kilometer (8.6-mile) <strong>Federal</strong>-aidsection west of Red Lodge, whichhad always been cleared by MDTworkers. From 1938 to 1945, BPR,using NPS funds, oversaw the sectionmanaged under the park approachact. But in 1945, Congressenacted legislation giving NPS theauthority to plow and clear thehighway, and thereafter park servicecrews, using Forest Service funds,maintained the longer section.Three <strong>Orphaned</strong> SectionsIn the early years, Wyoming was neverexpected or formally asked to maintainits 56.3-kilometer (35-mile) sectionof the Beartooth, a bow-shapedsquiggle between the western andeastern ends of the roadway, whichThe narrow roadway width and lack of formal pullouts and parking areascreate dangerous situations when bicyclists, cars, recreational vehicles, andtour buses converge at the same location, such as at this spot heading westtoward Cooke City near Beartooth Butte. Plans call for better designed andmore appropriately located pullouts and parking areas.are both in Montana. (The Wyomingportion would later be designatedsegments 2, 3, and 4 during the modernreconstruction.) The highwayprovided little value to Wyomingbecause it had no connection to therest of that State’s highway system.Similarly, Montana never maintainedthe 13.5 kilometers (8.4 miles) fromthe park’s northeastern entranceeastward through Cooke City to theWyoming border (segment 1 duringreconstruction) because the roadwaywas never incorporated intoMontana’s highway system due to itsremoteness and proximity to the park.By the late 1950s, this NPSmaintainedsection of Montanaroad had fallen into disrepair andbecome a problem for the agencyto maintain. In 1959 NPS proposedturning the section and an “undeterminedstrip of land” adjacent to thehighway into a national parkway<strong>An</strong> excavator removes material from a cut section and dumps it into a truckduring the segment 1 rehabilitation. Republic Mountain is in the background.PUBLIC ROADS • July/August • 2006 21

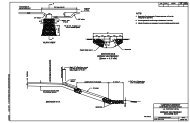

similar to the Blue Ridge Parkwayin the southern AppalachianMountains. This would have putsome 80 percent of the Beartoothand the strip of land under NPSjurisdiction, making the corridoreligible for annual congressionalmaintenance appropriations andsubject to the same regulations asany road inside a national park.But the Forest Service and localresidents opposed removing thestrip of land from Forest Servicejurisdiction and limiting its use.There were also issues with theeastern portion of the highway inMontana, emerging in a northeastwarddirection from Wyoming andgoing to Red Lodge. The <strong>Federal</strong>Government agreed to put mostof that section managed under thepark approach act into the foresthighway system so funds could beallocated from the Forest <strong>Highway</strong>Program (FHP) for maintenance andrepairs. The Forest Service, in collaborationwith FLHD, reconstructedsome of the flatter sections of theBeartooth between 1963 and 1984using FHP funds. But that still leftsome of the more rugged sectionsin need of repair. Some improvementoccurred in 1965, when MDTstarted maintaining 24.1 kilometers(15 miles) of the eastern sectioninside Montana due to the expenditureof FHP funds on that section.In the summer of 1982,Yellowstone’s superintendentasked the U.S. Department of theInterior’s Office of the Solicitorto determine who had ownershipand maintenance responsibility forthe Beartooth. The solicitor for theRocky Mountain region, in an August1982 opinion, determined thatalthough NPS had no authority to administerthe right-of-way or enforcetraffic laws, it did have “the responsibilityfor the usual maintenanceactions such as repaving, fillingpotholes, striping, and even reconstructionof the road.” The solicitor’sreport concluded that a satisfactorydivision of maintenance responsibilitiescould only be worked outbetween NPS and the Forest Service.“Unfortunately, it appears likely thatthe present situation will continuefor some time,” the solicitor wrote.A Maintenance QuandaryTo this day, about two-thirds of theBeartooth remains unclaimed—the portion in Montana nearestYellowstone (the later segment 1)and the Wyoming portions (thelater segments 2, 3, and 4). Thosestretches have served the publicfor 70 years without a permanentguardian willing and financiallyable to perform the kinds of repairsand maintenance demandedof a major alpine highway.A series of recent thin pavementoverlays has made the Beartooth appearon the surface to be in decentshape. But serious structural problemshave lurked beneath the pavementfor decades along some of its morerugged sections. Problems includedeteriorating pavement, base, andsubgrade; inadequate drainage; inconsistentroadway geometry; crumblingbridges; and insufficient roadwaywidth to accommodate today’s largertour buses and recreational vehicles.HKM EngineeringThese before-and-after photos show the slide debris deposited on the roadway at the Quad Creek crossing and thecleared road. During the slide, the debris flow blocked the culvert, forcing Quad Creek down the Beartooth <strong>Highway</strong>shoulder. The final project restored the original creek location and reestablished the channel and culvert drainage.22PUBLIC ROADS • July/August • 2006

Del McOmie, the WyomingDepartment of Transportation’s(WYDOT) chief engineer, explains theState’s predicament: “The section withinWyoming doesn’t meet the minimumdesign and operating standardsrequired for us to place the highwayinto our State highway system. Thecurrent condition of the highway ispoor, and we can’t afford the addedfinancial burden to bring the roadwayup to an acceptable service level forincorporation into our system.”If these sections of roadwayare upgraded to meet currentstandards, WYDOT will approachthe State transportation commissionand request that it fold thehighway into Wyoming’s maintenanceportfolio. “We’re continuingto work with FHWA and resourceagencies to bring the highway upto State standards so these ownershipand maintenance issues canbe [re]solved,” McOmie says.For its part, MDT is waiting onWyoming before it acts on Montana’swestern portion of the road. “Oncethe highway is up to standards andWYDOT takes over the Wyomingsection, there’s little reason Montanawouldn’t do the same,” says MDTDirector Jim Lynch.Finding PermanentCaregiversResolving the Beartooth’s ownershipand maintenance issues began in earnestin 1994, when NPS asked FHWAto complete an evaluation and needsassessment of the entire Beartoothcorridor. In doing the evaluation,FLHD divided the highway into sevensegments going west to east, beginningwith segment 1 at the parkentrance and ending with segment7 outside Red Lodge. The evaluationdetermined that segments 2 and 3 inWyoming and segments 6 and 7 inMontana met minimum State highwaystandards and were in at leastfair condition because of the 1963–1984 rehabilitations. Segment 5,just north of the Montana-Wyomingline in the east and known as theswitchback section, was rebuilt tomodern standards in the 1970s andis in acceptable condition; however,it has a history of landslides becauseof its extremely steep terrain.On the other hand, segment 1and Wyoming’s 29-kilometer (18-mile)segment 4, from the Clay ButteLookout Road to the summit of3,337-meter (10,947-foot) BeartoothPass and the State line, had neverbeen brought up to modern standards.These sections were deemedin poor condition and in need ofimmediate reconstruction. Theybecame the focus of the overall initiativeto rebuild and modernize theBeartooth.After the evaluation was completed,in 1997, the Montana congressionaldelegation convened a steeringcommittee comprising representativesfrom the Forest Service, FHWA,NPS, WYDOT, and MDT to overseethe highway’s funding, maintenance,and ownership issues. The committeeprovided extensive documentationof potential funding sources andestablished the goal of rebuildingsegment 4 to modern standards by2010. Then Wyoming could considertaking full ownership and maintenanceresponsibility for its sectionof the highway.At about the same time, effortsto improve segment 4 received aThe Beartooth’s narrowroadway and lackof shoulders leavelittle or no room tostore snow when theroad is plowed andopened to traffic in thespring. The resultinghigh snow banksshown here createan additional safetyhazard, but wideningthe roadway will helpalleviate the problem.A common road surfacecondition, known as“alligator cracking,”along segment 4 is alsoevident in this photo,because pavementbreakup caused bypoor drainage allowedwater to permeate thepavement substructure.funding boost. USDA designated$9.8 million for segment 4 from a1998 congressional appropriationthat resulted from a mine settlement(Crown Butte). That sameyear, Congress listed the Beartooth<strong>Highway</strong> as a “high-priority” projectin the Transportation Equity Actfor the 21 st Century and allowedMontana to spend up to $19.9 millionon any section of the highway,whether in Montana or Wyoming.Some of the Crown Butte moneywas used to install a thin asphaltoverlay on segment 4 in 2001 asa temporary preventive measureuntil the highway could be rebuilt.The money also enabled FLHDto begin design, environmentaldocumentation, and environmentalcompliance for reconstructing thesegment.Segment 1 ReconstructionFLHD secured FHP funds for similarwork on segment 1 as well. ByAugust 1997, the WFLHD office inPUBLIC ROADS • July/August • 2006 23

One of the most unsafe alignment areas along segment 4 and site of numerous crashes is Beartooth Ravine, shown herein an aerial photograph from the EIS depicting the location for the new bridge. The bridge is a three-span steel girderstructure that will cost in excess of $4 million. Source: FHWA.Vancouver, WA, had completed adraft environmental assessment forreconstruction. Public commentand revisions took 5 more years.The first phase of segment 1reconstruction, a 3-year, $11.2 millionproject stretching about 8kilometers (5 miles) from CookeCity to the Montana-Wyoming border,began in May 2004. Work duringthe first two seasons includedclearing, earthwork for roadwaywidening and realignments, roadwaysubexcavation and backfilling,placement of subbase material, andinstallation of new drainage structures.Crews will finish phase 1 insummer 2006 by completing workon the realignments and drainagesystems, placing the road base, installingmore than 3.2 kilometers(2 miles) of guardrail, and completingasphalt paving and striping.The second phase of segment 1reconstruction, a 2-year, $8 millionproject covering about 5.6 kilometers(3.4 miles) from the park entranceto Cooke City, is scheduled tobegin in summer 2007. Phase 2 issmaller in scope but involves similarwork, primarily widening the roadwayto 8.5 meters (28 feet), makingminor realignments, improving drainage,and completely reconstructingthe pavement. After completion ofphase 2 in fall 2008, the entire westernMontana section will meet currenthighway standards.Segment 4 ReconstructionReconstructing segment 4, the alpinesection that climbs up and overBeartooth Pass, is a complex and difficultproject, according to engineeringstudies. The 1994 environmentalimpact statement (EIS) concluded,“Segment 4 clearly has the worst conditionsof any portion of the route.”One major challenge is the roadway’snarrow width and absenceof paved shoulders. The 2.7-meter(9-foot) travel lanes are narrowerthan standard snowplow blades,making snow removal difficult andunsafe, especially when the road isopen to traffic. Also, some of thesteeper sections have little or noroom to store the plowed snow.Many of today’s tour buses and motorhomes measure 3.2 meters (10.5feet) wide including side mirrors.When two such vehicles meet alongthis section of the highway, one orboth must drive off the pavementto avoid a collision. Not only arethese conditions unsafe for motoristsand bicyclists, they contributeto “edge raveling,” erosion of thepavement edge due to insufficientlateral support, which is normallyprovided by a paved road shoulder.Other problems on segment 4include inadequate drainage, causingthe pavement to crack and break upin many locations, lack of definedroadside pullouts and parking areas,sharp curves, sudden dips andcrests, and deteriorating bridges.24PUBLIC ROADS • July/August • 2006

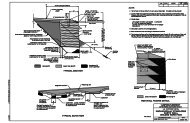

Because of the size and scopeof reconstructing segment 4, theCFLHD office in Lakewood, CO,planned the project under an EISbeginning in 1999. During theprocess, CFLHD developed andevaluated six alternatives, includinga “no action” option. The five “build”alternatives looked at the potentialsocial, economic, and environmentalimpacts of road widening, majorroad realignments, and pulloutconstruction. After consultationwith the public and project partnersand stakeholders, alternative6 was selected and published in aFebruary 2004 record of decision.Alternative 6 includes wideningthe road to a width, includingshoulders, ranging from 8.5 meters(28 feet) to 9.8 meters (32 feet),depending on location. It also callsfor major realignments at five locations,upgrading drainage structures,constructing and improvingparking areas or pullouts, reconstructingfour historic bridges, andinstalling a new asphalt pavementsurface. A recent funding analysisestimates the total costs for alternative6 at $115 million, includingengineering, making for a projecttimeline of 8 to 9 years for segment4, based on timely receipt ofrequired fiscal year appropriationsbeginning in 2007.Mudslides and FundingRemove Focus FromSegment 4Reconstruction of segment 4, using$17.5 million of MDT’s $19.9million appropriation, began withtree clearing and setup of a contractorwork camp in 2004. Actualconstruction was planned to beginin summer 2005 at a hazardous locationknown as Beartooth Ravine,a 0.8-kilometer (0.5-mile) sectioncontaining extremely sharp curves.A new bridge and retaining wall areproposed for the area, along with apullout to view Beartooth Falls anda new geologic and wildlife interpretivesite at the western end ofthe bridge. Because of substantialprice increases in the constructionindustry, however, bids received onthe project were too high to allowaward, because no other sources offunding were available to supplementthe remaining MDT funds.Also, in the spring of the 2005construction season, the highwayexperienced yet another setback.A series of devastating landslidesstruck the Beartooth Pass andswitchback area of Montana’ssegment 5 on May 20. A severeAt the Streck swale turnout, the contractor crushed and reprocessed excess slide material through a sieve and utilized itfor slope stabilization and backfill on the wall structures.HKM EngineeringPUBLIC ROADS • July/August • 2006 25

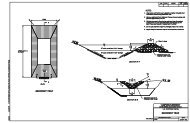

Innovative Solutions for aTemporary SetbackAfter mudslides on parts of segment 5 of the Beartooth <strong>Highway</strong> in May 2005, the repairwork required ingenuity, technical expertise, coordination among engineering disciplines,and management ability. The design and construction team needed to consider the complexhydrologic, geologic, and climatic conditions of the site.Mountainous terrain, with slopes up to 70 degrees and highly unstable material,presented numerous challenges. Gullies were eroded in places, creating drops of 12.2meters (40 feet). Construction performance levels—such as the need to protect motoristsfrom future debris flows and the roadway from high repair costs—were established todetermine appropriate levels of repair.In the end, the project team chose debris barrier fences and training berms to controlfuture slide impacts. Training berms improve public safety and facilitate maintenance by redirectingand isolating debris flows, usually at the top of a slope. A Geobrugg ® rockfall fencingsystem was installed at several sites where unstable slopes still had the potential for smallslides. The fences are the first of their kind in Montana and the tallest in North America.Because the damage occurred within the boundaries of a national forest, the contractorsused special aesthetic features, such as reusing native rock for armoring at drainagestructures, to preserve and protect natural resources and minimize visual impacts. TheForest Service was actively involved throughout the design process.A major design component was mechanically stabilized earth (MSE) walls. Due to limitedaccess to segment 5 and its narrowness, the contractors needed to modify conventionaldesigns. Workers used truncated, geosynthetic reinforcement (geogrids) to stabilizethe multiple wall layers. At 7.9 meters (26 feet) high, they are the tallest geogrid-reinforcedMSE walls used on any MDT project. Onsite fabrication reduced construction costs andtime. About 557 square meters (6,000 square feet) of walls were constructed to supportbackfill for new roadway alignments.Rock bolts anchor the MSE wall system. The contractors increased the number ofanchors and steel tiebacks to provide more sacrificial steel and enhance the safety factor.A study indicated that larger steel components and increasing the number of structuralelements would raise the safety factor to 1.30, meaning the structures were nearly 1.5times stronger than the maximum forces expected to be exerted on them in a futureevent. Higher safety factors are often used during design of geotechnical structures dueto difficulty in determining loading parameters.<strong>An</strong> oversized, micropile-supported concrete foundation also enhanced stability andprovided a higher safety factor. The micropiles are designed to ensure that the MSE wallswill withstand large debris storage, resist overturning forces, and result in improved bearingcapacity, which is the ultimate load a foundation can support before failure. To protectthe walls from erosion, the contractors also filled trenches, ranging from 1.5 to 3.0meters (5 to 10 feet) deep, at the MSE wall toes with concrete. In addition, rock retentionwalls were used to contain slide debris at critical locations to facilitate maintenance.At the top of Beartooth Pass, more than 76,400 cubic meters (100,000 cubic yards) ofrock and slope material were blasted and removed to accommodate the roadway wideningfor the new drainage system. <strong>An</strong> innovative feature of the project was the reuse ofmaterial from blasting and debris flow excess.Workers screened, sorted, and reused the debris as engineered rockfills on failedslopes, armoring at drainage inlets and outlets, and structural backfill within the MSEwalls. Reusing the material expedited the project, minimized haul distances, reducedoverall costs, and assisted the Forest Service with reclaiming a former open-pit chromitemine by using debris flow material as fill. In addition, the project restored a major drainage(Quad Creek), which was realigned by the debris flow.Through effective management, efficient communication, and creative design, thecontracting team completed the project ahead of schedule and almost $4 million underbudget. The collaborative spirit exhibited by the stakeholders, community representatives,and the project team was essential to restoring the highway and ensuring enjoyment ofthe Beartooth for future generations.spring storm that dropped nearly22.9 centimeters (9 inches) of raincaused avalanches of mud, rock,and debris to completely sweepaway sections of the highway inseveral places. In all, five majorslides damaged 13 portions of theroad. MDT had to close the roadindefinitely in the slide area—justa week before the Memorial Dayweekend and the start of the busytourist season.“The closure of the Beartooth<strong>Highway</strong> was significant to oureconomy,” says Bev Chatelain,owner of the Big Moose Resortand president of the Cooke City,Colter Pass, Silver Gate Chamber ofCommerce. “A survey completed inJune 2005 comparing numbers toJune 2004 indicated a decrease inbusiness as high as 75 percent forsome establishments, the averagebeing about a 20-percent to 30-percent decline.”She adds: “Our small communitiesof Colter Pass, Cooke City, andSilver Gate, with 90 year-roundresidents, offer the most uniqueaccess anywhere in the world toMother Nature’s natural beauty, butthen you can see how devastationfrom Mother Nature can affect us.”Because of the road’s economicimportance to Red Lodge andCooke City, tremendous effortensued to reopen it as quickly aspossible. Repair costs were estimatedat $15 million to $20 million.U.S. Transportation SecretaryNorman Y. Mineta authorized aquick release of $2 million in emergencyrelief funds on June 10, 2005,so MDT could jump-start the processof clearing debris, stabilizingslopes, and installing other safetymeasures. By using the remaining$12 million of unspent high-priorityproject funds for segment 4, MDTobtained enough additional fundingfor the emergency repairs.“Our goal was to get the roadopened as soon as possible,”says FHWA Montana <strong>Division</strong>Administrator Jan Brown. “So themoney from CFLHD was transferredback to Montana, with the agreementthat Montana would returnthe money as soon as the Statereceived additional emergencyrelief funds in the future. All theparties involved are working togetherto make sure this happens.”The project contract was awarded26PUBLIC ROADS • July/August • 2006

June 15, 2005, less than4 weeks after the landslides.Constructioncrews, working 24hours a day, 6 days aweek, completed theproject in just 4 months,in early October.The Road toAdoptionWith the Montana sectionnow repaired, the focushas shifted to puttingreconstruction of segment4 back on track.To construct a 1-kilometer(0.6-mile) project containinga new bridge andretaining wall at the highway’sworst safety location(Beartooth Ravine),$4 million is needed in2007 in addition to theremaining $12 million inhigh-priority funds. Toadvance a 2.8-kilometer(1.6-mile) project fromthe beginning of segment4 through BeartoothRavine, thus taking advantageof economies ofscale and better constructionsequencing, an additional$8 million is required.In support of this fundingneed, WYDOT has requested additionalfunding from the Public<strong>Lands</strong> <strong>Highway</strong>s DiscretionaryProgram in the fiscal year 2007appropriations bill in the amountof $5 million. These efforts andothers will help advance reconstructionof all of segment 4—andthus set the orphaned Beartooth<strong>Highway</strong> on the road to adoption.Michael Kulbacki is a field operationsengineer with FHWA’s Montana<strong>Division</strong> office in Helena. As theoperations team leader, he is responsiblefor oversight and stewardshipduties for the <strong>Federal</strong>-aid highwayprogram in Montana in the areasof design, environment, and construction.His career spans 13 yearswith FHWA and 2 years consultingin the private sector. He earneda B.S. in civil engineering fromVirginia Polytechnic Institute andState University and is currentlyfinishing an M.S. in civil engineeringConcrete pump and delivery trucks are parked on the temporary alignment during constructionof a foundation at an MSE wall on the second Bradshaw Crossing. The uphill slope is overlaidwith geofabric and soil bolt anchors inserted as a stabilization measure to prevent slopefailure.at the University of Colorado atBoulder. Kulbacki is a registeredprofessional engineer in Coloradoand Montana. He can be reachedat 406–449–5302, ext. 239, ormichael.kulbacki@fhwa.dot.gov.Bert McCauley is a project managerwith CFLHD in Lakewood, CO.He is currently the agency’s projectmanager for segment 4 reconstructionin Wyoming. He has been intransportation engineering for 34years in various <strong>Federal</strong>, State, andlocal government and universitycapacities, including 18 years withFHWA. He holds a B.S. in civil engineeringfrom Texas Tech University,completed the graduate curriculumin transportation engineering as arecipient of the FHWA fellowshipto the Bureau of <strong>Highway</strong> Trafficat Pennsylvania State University,and is a registered professional engineerin Wyoming and Texas. Hecan be reached at 720–963–3726or bert.mccauley@fhwa.dot.gov.Steve Moler is a public affairs specialistat FHWA’s Resource Center inSan Francisco, CA. He has workedin various aspects of journalism andmass communications for more than20 years, including news writingand editing, public relations, andcommunity outreach. He has a B.S.in journalism from the University ofColorado at Boulder. He has beenwith FHWA for 5 years, helping itsfield offices and partners with mediarelations, public relations, and publicinvolvement communications. Hecan be reached at 415–744–3103or steve.moler@fhwa.dot.gov.For more information, visit www.cflhd.gov/projects/wy/beartooth/index.cfm or contact BertMcCauley at 720–963–3726 orbert.mccauley@fhwa.dot.gov.Additional information about theBeartooth <strong>Highway</strong> can be foundat www.byways.org/browse/byways/2281.The authors would like to thankJennifer Corwin, an environmentsenior technical specialist at CFLHD,for her contribution to this article.MDTPUBLIC ROADS • July/August • 2006 27