the explorers journal the global adventure issue - The Explorers Club

the explorers journal the global adventure issue - The Explorers Club

the explorers journal the global adventure issue - The Explorers Club

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>Winter 2007/2008president’s letterour honorable tradition continues<strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> was originally conceived as an association of<strong>explorers</strong> who ga<strong>the</strong>red for regular meetings that, in 1904, <strong>the</strong> foundersreferred to as smokers. While a lot has changed since <strong>the</strong>n, ourdedication to our original mission of promoting exploration by sharingour accomplishments with <strong>the</strong> general public and <strong>the</strong> educational andscientific communities is stronger than ever. This year, I have been privilegedto attend many inspiring educational programs at which I was ableto share some of our club’s history and current activities with scientists,educators, and students. I would like to highlight a few of those for you.In April, I spoke at a symposium dedicated to <strong>the</strong> future exploration ofEarth and space. This event was held in conjunction with <strong>the</strong> launch ofArizona State University’s new School of Earth and Space Exploration—<strong>the</strong>first institution to unite Earth and planetary scientists with astronomers.In June, I hosted a seminar on exploration at Morehouse College inAtlanta as part of <strong>the</strong> student-mentoring program, Adventures of <strong>the</strong>Mind. O<strong>the</strong>r members in attendance included Nobel Prize winner MurrayGell-Mann, Ph.D., FN’79, and Kenneth Mark Kamler, M.D., FR’84.In August, I was invited to appear on Bloomberg’s Night Talk withMike Schneider, which gave me <strong>the</strong> opportunity to share <strong>the</strong> historyof our club with <strong>the</strong> public, as well a chance to talk about some of <strong>the</strong>amazing accomplishments our members have achieved since <strong>the</strong> foundingof our club more than a century ago.In October, I moderated a symposium, Risk and Exploration II—Earthas a Classroom, at Lousiana State University in Baton Rouge. <strong>The</strong>re, Iwas once again joined by Kamler and our club’s honorary president, JimFowler, who spoke at <strong>the</strong> event. A webcast of <strong>the</strong> symposium, establishedby astronaut Leroy Chiao, FN’05, can be seen in its entirety atwww.riskexplore2007.com.Thank your for <strong>the</strong> opportunity to serve during this past year as yourpresident. It has been a privilege and an inspiration to represent <strong>the</strong> clubon <strong>the</strong>se momentous and groundbreaking occasions when history andexploration are still revered. It is also rewarding to know that after 103years, our mission is as relevant today as it was at our founding.Sincerely yours,Daniel A. Bennett

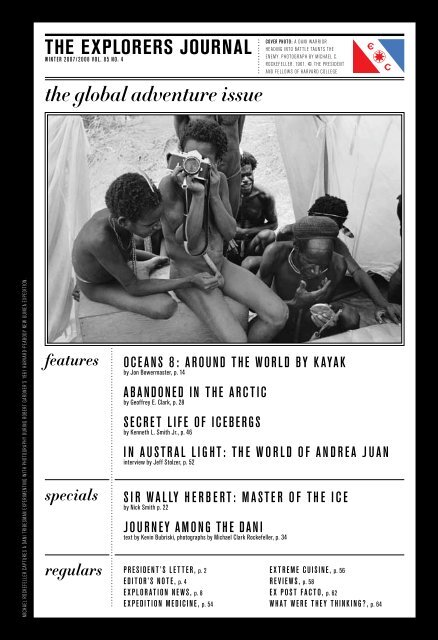

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>Winter 2007/2008editor’s noteA Global AdventureThis <strong>issue</strong> we set foot on literally every continent on Earth.In our lead story, Jon Bowermaster invites us along on hisOceans 8 expedition, which, as of this writing, is boundfor Antarctica’s Larsen Ice Shelf to complete <strong>the</strong> final legof a journey that has taken <strong>the</strong> avid kayaker to some of <strong>the</strong>most remote parts of our globe. Paddling through sharkinfestedwaters and treacherous seas, Bowermaster is ona quest to focus international attention on <strong>the</strong> plight of ouroceans, which are threatened by <strong>global</strong> warming, pollution,and overfishing.As part of our ongoing celebration of <strong>the</strong> InternationalPolar Year (see http://www.ipy.org/) we continue to highlightpioneering research in <strong>the</strong> polar environments. This<strong>issue</strong>, Kenneth L. Smith of <strong>the</strong> Monterey Bay AquariumResearch Institute shares his work unraveling <strong>the</strong> secretlives of Antarctica’s icebergs. Once thought to be littlemore than inanimate islands of frozen water, icebergs havebeen found to host complex independent ecosystems thatplay a critical role in <strong>the</strong> drawdown of carbon dioxide andorganic replenishment of our oceans. In <strong>the</strong> Arctic, Geoffrey Clark providesfresh insight into <strong>the</strong> events that unfolded during Adolphus W.Greely’s tragic Lady Franklin Bay Expedition of 1881–1884.We are also privileged to publish selections from a rare portfolio ofimages that have lain dormant since <strong>the</strong> 1968 publication of RobertGardner’s Gardens of War: Life and Death in <strong>the</strong> New Guinea StoneAge and snapped by none o<strong>the</strong>r than Michael Clark Rockefeller onlymonths before his mysterious disappearance while documenting<strong>the</strong> Asmat of sou<strong>the</strong>rn New Guinea in November 1961. Taken duringGardner’s famed Harvard-Peabody Expedition to <strong>the</strong> Baliem Valley, <strong>the</strong>photographs—some 4,000 in all—chronicle <strong>the</strong> daily lives of <strong>the</strong> warringDani, who, despite <strong>the</strong> encroachment of <strong>the</strong> modern world—continue topursue <strong>the</strong>ir traditional lifeways.an elegant manta ray swimsbeneath Jon Bowermaster’s kayakOff <strong>the</strong> atoll of Fakarava in <strong>the</strong>Tuamotus. Photo by Peter McBrideAngela M.H. Schuster, Acting Editor-in-Chief

THE EXPLORERS CLUB TRAVELERSA World of AdventuresFEATURED JOURNEYHidden AlaskaPrivate Lodges in Denali, Fox Island& <strong>the</strong> Kenai Peninsulawith <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> PresidentDaniel A. BennettJuly 8–19, 2008Travel with <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> members and friends onluxurious <strong>adventure</strong>s far off <strong>the</strong> beaten path in <strong>the</strong>company of distinguished and engaging leaders. Take a floatplane to <strong>the</strong> world famousBrooks Falls to view brown bearsfeeding on migrating salmon; Cruise aboard a private boat through<strong>the</strong> Kenai Fjords National Park toview sea otters, puffins (and manyo<strong>the</strong>r bird species), harbor seals, Stellersea lions, and whales; Stay deep within Denali National Parkand enjoy excursions to view caribou,moose, Dall sheep, grizzly bears, andresident & migratory birds. Experience <strong>the</strong> thrill of rafting through <strong>the</strong>Kenai National Wildlife Refuge; Optional flight-seeing tours of Mt.McKinley (Denali) and its adjacent glacialcanyons; Our small group of no more than 14participants will stay at some of Alaska’sfinest backcountry lodges.SELECTED JOURNEYSimage courtesy of © 2007 Will Steger FoundationPlease contact us at:800-856-89519am - 6pm Mon-Fri, ETToll line: 603-756-4004Fax: 603-756-2922Email: ect@studytours.orgWebsite: www.<strong>explorers</strong>.orgUltimate Serengeti SafariFebruary 12–24, 2008 (13 days)Himalayas by AirMarch 21–April 7, 2008 (18 days)<strong>The</strong> Best of Melanesia & MicronesiaPapua New Guinea, Trobriand Islands, Yap & PalauMay 8–24, 2008 (17 days)Fire & IceJapan to Kamchatka, June 7–21, 2008 (15 days)Kamchatka to Alaska, June 19–July 3, 2008 (15 days)

<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>winter 2007/2008<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> clubPresidentDaniel A. BennettBoard Of DirectorsOfficersPATRONS & SPONSORSHonorary ChairmanSir Edmund P. Hillary,KG, ONZ, KBEHonorary PresidentJames M. FowlerHonor a ry Direc torsRobert D. Ballard, Ph.D.George F. Bass, Ph.DEugenie Clark, Ph.D.Sylvia A. Earle, Ph.D.Col. John H. Glenn Jr., USMC (Ret.)Gilbert M. GrosvenorDonald C. Johanson, Ph.D.Richard E. Leakey, D.Sc.Roland R. PutonJohan Reinhard, Ph.D.George B. Schaller, Ph.D.Don Walsh, Ph.D.CLASS OF 2008Garrett R. BowdenJonathan M. ConradKristin Larson, Esq.Margaret D. Lowman, Ph.D.Robert H. WhitbyCLASS OF 2009Daniel A. BennettKenneth M. Kamler, M.D.Lorie Karnath<strong>The</strong>odore M. SiourisAlicia StevensCLASS OF 2010Anne L. DoubiletWilliam HarteKathryn KiplingerDaniel A. Kobal, Ph.D.R. Scott Winters, Ph.D.Vice President, ChaptersRobert H. WhitbyVice President, MembershipLynda RoyVice President For OperationsGarrett R. BowdenVice President, Research & EducationMargaret D. Lowman, Ph.D.TreasurerMark KassnerAssistant TreasurerKevin O’BrienSecretaryDaniel A. Kobal, Ph.D.Assistant SecretaryAnne DoubiletPatrons Of ExplorationRobert H. RoseMichael W. ThoresenCorporate Partner Of ExplorationRolex Watch U.S.A., Inc.Corporate Benefactors Of ExplorationLenovoRedwood Creek WinesCorporate Supporter Of ExplorationNational Geographic Societymas<strong>the</strong>adEDITORSActing Editor-in-ChiefAngela M.H. SchusterManaging EditorJeff StolzerContributing EditorsJeff BlumenfeldJim ClashClare Flemming, M.S.Michael J. Manyak, M.D., FACSMilbry C. PolkCarl G. SchusterNick SmithCopy ChiefValerie Saint-RossyART DEPARTMENTArt DirectorJesse AlexanderDeus ex MachinaSteve Burnett<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong> © (ISSN 0014-5025) is publishedquarterly by THE EXPLORERS CLUB, 46 East 70th Street,New York, NY 10021, telephone: 212-628-8383, fax:212-288-4449, website: www.<strong>explorers</strong>.org, e-mail: editor@<strong>explorers</strong>.org. <strong>The</strong> views and opinions expressed hereindo not necessarily reflect those of THE EXPLORERS CLUB or<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>. Subscriptions should be addressedto: Subscription Services, <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>,46 East 70th Street, New York, NY 10021.Subscriptionsone year, $29.95; two years, $54.95; three years, $74.95;single numbers, $8.00; foreign orders, add $8.00 per year.Members of THE EXPLORERS CLUB receive <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong><strong>journal</strong> as a perquisite of membership.PostmasterSend address changes to <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>, 46 East70th Street, New York, NY 10021.SUBMISSIONSManuscripts, books for review, and advertising inquiriesshould be sent to <strong>the</strong> Editor, <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>, 46East 70th Street, New York, NY 10021. All manuscripts aresubject to review. <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong> is not responsiblefor unsolicited materials.All paper used to manufacture this magazine comes fromwell-managed sources. <strong>The</strong> printing of this magazine is FSCcertified and uses vegetable-based inks.THE EXPLORERS CLUB, <strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> journaL, THE EXPLORERSCLUB TRAVELERS, WORLD CENTER FOR EXPLORATION, and <strong>The</strong><strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> Flag and Seal are registered trademarks ofTHE EXPLORERS CLUB, Inc., in <strong>the</strong> United States and elsewhere.All rights reserved. © <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>, 2007.50% RECYCLED PAPERMADE FROM 15%POST CONSUMER WASTE

<strong>The</strong> 6th Annual<strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>Film FestivalJune 13-14, 2008Celebrating<strong>the</strong> Spirit ofExplorationCall for Submissions: December 1, 2007Deadline for Submissions: February 15, 2008Best Exploration FilmBest Science Exploration FilmBest Adventure FilmBest Conservation and Wildlife FilmBest Environmental FilmBest Expedition FilmBest Film by an <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> MemberFestival Director’s Choice—An <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong> Flag Expedition Film.For more information: www.<strong>explorers</strong>.orgSir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay, courtesy <strong>the</strong> Royal Geographical Society Everest Archive

exploration newsedited by Jeff Blumenfeld, expeditionnews.comA r c t i c S e a i c erecord Lowfabled Northwest Passage open for shipping?square kilometers per year.One factor that contributedto this fall’s extreme declinewas that <strong>the</strong> ice was entering<strong>the</strong> melt season in an alreadyweakened state. Accordingto NSIDC research scientistJulienne Stroeve, “Spring of2007 started out with lessice than normal, as well asthinner ice.” Ano<strong>the</strong>r factorwas an unusual atmosphericpattern, with persistent highatmospheric pressures over<strong>the</strong> central Arctic Ocean andlower pressures over Siberiathis past summer—clear skiesunder <strong>the</strong> high-pressure cellpromoting strong melt. At<strong>the</strong> same time, <strong>the</strong> patternof winds pumped warm airinto <strong>the</strong> region. While <strong>the</strong>warm winds fostered fur<strong>the</strong>rmelt, <strong>the</strong>y also helped pushice away from <strong>the</strong> Siberianshore.Recycle thoseropesArctic ice has shrunk to <strong>the</strong>lowest level on record, newsatellite images show, raising<strong>the</strong> possibility that <strong>the</strong>Northwest Passage will becomean open shipping lane.According to <strong>the</strong> NationalSnow and Ice Data Center(NSIDC), <strong>the</strong> average seaice extent for <strong>the</strong> month ofSeptember was 4.28 millionsquare kilometers, <strong>the</strong> lowestSeptember on record, shattering<strong>the</strong> previous record for8<strong>the</strong> month, set in 2005, by 23percent. At <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> meltseason, September 2007 seaice was 39 percent below <strong>the</strong>long-term average from 1979to 2000. If ship and aircraftrecords from before <strong>the</strong> satelliteera are taken into account,sea ice may have fallen by asmuch as 50 percent since <strong>the</strong>1950s. <strong>The</strong> September rateof sea ice decline since 1979is now approximately ten percentper decade, or 72,000extend your lifelineSterling Rope has launcheda rope recycling program inpartnership with Rock/CreekOutfitters, ClimbingGear.com,and <strong>the</strong> Triple Crown BoulderingSeries. Until <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong>year, Sterling will be collectingand recycling used ropesof any brand, rewardingthose who participate witha discount on a brand newrope. Sterling feels that in cooperationwith climbers, <strong>the</strong>y

fields and rugged icepackin uncharted territory. Forinformation, visit: www.beyondshackleton.com.Brightest SupernovaEver Spottedis one coming to a galaxy near you?<strong>The</strong> brightest stellar explosionever recorded may be a longsoughttype of supernova,according to observationsby NASA’s Earth-orbitingChandra X-ray Observatoryand ground-based opticaltelescopes in Hawaii. Thisdiscovery indicates that violentexplosions of extremelymassive stars were relativelycommon in <strong>the</strong> early universe,and that a similar explosionmay be ready to go off in ourown galaxy.“This was a truly monstrousexplosion, a hundred timesmore energetic than a typicalsupernova,” said NathanSmith of <strong>the</strong> University ofCalifornia at Berkeley, who leda team of astronomers fromCalifornia and <strong>the</strong> Universityof Texas in Austin.First detected in September2006, <strong>the</strong> SN 2006gy explosionoccurred in a galaxyknown as NGC 1260, some240 million light-years away.It brightened over <strong>the</strong> course10EXPLORATION NEWSof 70 days, and at its peakemitted more than 150-billion-Sun’s worth of light.Scientists estimate thatamong <strong>the</strong> 400 billion starsin <strong>the</strong> Milky Way, <strong>the</strong>re areonly a dozen or so as massiveas SN 2006gy. <strong>The</strong> star thatproduced SN 2006gy apparentlyexpelled a large amountof mass prior to exploding.This large mass loss issimilar to that seen from EtaCarinae, a massive star 7,500light-years away in our owngalaxy, raising suspicion thatit may be poised to explodeas a supernova. An unstablestar, Eta Carinae is currentlyradiating about five milliontimes more energy than ourSun and is undergoing eruptionson its surface that aresimilar to what scientiststhink happened on <strong>the</strong> starthat produced SN 2006gyjust before it blew.“Eta Carinae’s explosioncould be <strong>the</strong> best star-showin <strong>the</strong> history of modern civilization,”said Mario Livio of <strong>the</strong>Space Telescope ScienceInstitute in Baltimore,” notingthat despite its relativelyclose proximity to us, EtaCarinae’s death is not likelyto pose any significant threatto life on Earth.Scientists believe thatafter <strong>the</strong> violent collapse ofstars such as SN 2006gy,runaway <strong>the</strong>rmonuclear reactionsensue and <strong>the</strong> explodingstars spew <strong>the</strong>ir remains intospace ra<strong>the</strong>r than completelycollapsing to a black hole as<strong>the</strong>orized. “In terms of <strong>the</strong>effect on <strong>the</strong> early universe,<strong>the</strong>re’s a huge difference between<strong>the</strong>se two scenarios,”said Smith. “One pollutes<strong>the</strong> galaxy with large quantitiesof newly made elementsand <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r locks <strong>the</strong>mup forever in a black hole.”Information and images of <strong>the</strong>supernova are available at:http://chandra.nasa.govSo What’s in a Comet?not <strong>the</strong> kitchen sink<strong>The</strong> heart of comet Tempel-1,which spurted out some ofits contents during <strong>the</strong> DeepImpact spacecraft encounterin July 2005, contains amixture of materials usuallyfound in very different environments,scientists report.Carey M. Lisse of JohnsHopkins University AppliedPhysics Laboratory in Laurel,MD, and colleagues traced<strong>the</strong> mineral compositionof <strong>the</strong> ejecta from infraredspectra taken with <strong>the</strong>Spitzer Space Telescope.<strong>The</strong> mixture included highlyvolatile organic ices, clays,and carbonates formed inenvironments with waterpresent, and highly crystallinesilicates formed at temperaturesexceeding 1,000degrees Kelvin. “Some typeof <strong>global</strong> mechanism formixing <strong>the</strong>se materials musthave been available during<strong>the</strong> solar system’s earliestdays,” says Lisse.

EXPLORATION NEWSGene SavoyAndean research loses a pioneer<strong>The</strong> world of Andean exploration lost one of its mostcolorful and controversial pioneers on September11. Douglas Eugene “Gene” Savoy, FE‘69, oncedubbed <strong>the</strong> “real” Indiana Jones by PEOPLEmagazine, died of natural causes, age of 80, at hishome in Reno, Nevada. In addition to his lifelonginterest in Andean exploration and archaeology, hewas deeply religious and eventually founded <strong>the</strong>International Community of Christ in Reno.Beyond <strong>the</strong> circle of hisfamily, friends, and religiousfollowers, Savoy is best rememberedfor his Andeanexploits. His life of <strong>adventure</strong>began in 1957. At <strong>the</strong>age of 30, following a failedfirst marriage, he left <strong>the</strong>United States to seek hisfortune in Lima. <strong>The</strong>re hemet and married a prominentPeruvian lady, founded<strong>the</strong> Andean <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>,and began his lifelongsearch for <strong>the</strong> “lost cities”of <strong>the</strong> Amazon. In 1964, herevisited Hiram Bingham’sruins at <strong>the</strong> Plain of Ghostsin <strong>the</strong> Amazonian rainforestand correctly identified <strong>the</strong>m as Vilcabamba, <strong>the</strong>Incas’ final redoubt. Several years later, he wasamong <strong>the</strong> earliest to visit <strong>the</strong> remote Chachapoyasite of Gran Pajatén in nor<strong>the</strong>rn Peru. His claimsof “discoveries” in both cases were later disputedby o<strong>the</strong>rs, setting a pattern that would plaguehim throughout his career. Antisuyo, his 1970book describing both expeditions, never<strong>the</strong>lessbecame a cult classic among aspirant amateur<strong>explorers</strong>, inspiring many, myself included, tohead off into <strong>the</strong> jungle.Savoy returned to <strong>the</strong> United States in 1971 andtook up residence in Reno, where he married fora third time and founded <strong>the</strong> Andean <strong>Explorers</strong>Foundation & Ocean Sailing <strong>Club</strong>. True to <strong>the</strong> lattername, he went to sea often between 1977 and 1982on a ten-meter schooner and attempted variousKon Tiki-style sea <strong>adventure</strong>s on rafts of ancientAndean design. Like Thor Heyerdahl before him, hewas pursuing a strong belief in oceanic diffusionamong <strong>the</strong> Precolumbian cultures of <strong>the</strong> Pacificcoast. His 1974 book, On <strong>the</strong> Trail of <strong>the</strong> Fea<strong>the</strong>redSerpent, recounted some of <strong>the</strong>se voyages.In later life, he refocused on Peru and renewedhis efforts in <strong>the</strong> jungles ofChachapoyas, where hepursued his unorthodoxbelief in Amazonian originsfor Andean civilization.Stone tablets unear<strong>the</strong>d<strong>the</strong>re in 1989 showed evidence,he thought, of OldWorld writing. Eventually,he announced discoveriesof more than 40 “new”lost cities, including GranVilaya and Gran Saposoa,each composed, he said,of thousands of ruins. Onceagain, his claims were metwith derision by some colleagues,who noted thatmany sites presented in <strong>the</strong>press as startling new finds had been previouslyrecorded by himself and o<strong>the</strong>rs.<strong>The</strong> Peruvian government belatedly recognizedhis long years of exploration with several medalsin <strong>the</strong> late 1980s and <strong>the</strong> city of Reno proclaimed“Gene Savoy Day” in October 1996. Gene Savoy’swork continues under <strong>the</strong> direction of his son, Sean,also a member of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>, but <strong>the</strong> passingof <strong>the</strong> “real” Indiana Jones leaves a large gap in<strong>the</strong> Andean scene that will not soon be filled.biographyVincent R. Lee, FN ‘90, is an architect, explorer, and author ofForgotten Vilcabamba: Final Stronghold of <strong>the</strong> Incas.<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

12Fossett Searchcontinuesmissing planes of <strong>the</strong> past foundIf it’s possible that somegood could come out of <strong>the</strong>presumed death of missing<strong>adventure</strong>r Steve Fossett, 63,it’s this: searchers have spotteda half-dozen unchartedcrash sites that, once <strong>the</strong>y’reinvestigated, might bringsome solace to families offliers who disappeared decadesago. According to <strong>the</strong>Reno Gazette-Journal, some15 to 20 private planes havevanished in <strong>the</strong> wildernes areasince 1950. Searchers combinga 53,000-square-kilometerarea have yet to find signsof Fossett, who is thoughtto have crashed in nor<strong>the</strong>rnNevada on September 3 as hewas scouting out locations forhis next <strong>adventure</strong>—an attemptat <strong>the</strong> land-speed record.M o n e y o n t h e M o o n ?private robot companies wantedInternet giant Google said itwill give $20 million to <strong>the</strong> firstprivate group to land a rovingrobot on <strong>the</strong> lunar surface.<strong>The</strong> purse is being offeredby <strong>the</strong> X Prize Foundation,which awarded $10 million in2005 to a group that includedMicrosoft co-founder PaulAllen for launching a humaninto space. In <strong>the</strong> 1970s, <strong>the</strong>Soviets launched <strong>the</strong> onlyrobotic rovers to have negotiated<strong>the</strong> Moon. Budget woesforced NASA this spring tocancel its lunar-rover plan. Towin <strong>the</strong> $20 million, a vehiclemust ramble a quarter-mileand send video back to Earth.EXPLORATION NEWS<strong>The</strong> goals are “incrediblyfeasible,” said Peter Worden,director of NASA’s AmesResearch Center. “Most of<strong>the</strong> components could be purchasedoff <strong>the</strong> shelf.” NASAplans to send astronautsback to <strong>the</strong> Moon by 2020and establish a lunar researchcamp, but Worden said <strong>the</strong>contest doesn’t threaten <strong>the</strong>agency. Such private spaceexploration “is exactly whatwe hoped would happen,” hesaid. “NASA is pretty excitedabout this.”Young Climbers at Riskstudy warns against hard trainingA review of <strong>the</strong> scientificliterature on young climbers—recently published by AudryMorrison and Volker Schöffl in<strong>the</strong> British Journal of SportsScience and posted to <strong>the</strong>American Alpine Journal websiteby Dougald MacDonald(www.americanalpineclub.org)—suggests <strong>the</strong>y maybe at risk for serious injury.Morrison and Schöffl defineyoung climbers as those betweenages 7 and 17. <strong>The</strong>ylooked at 50 climbing studiesand large-scale physiologicalstudies of <strong>the</strong> development ofyoungsters, and although <strong>the</strong>authors point out that <strong>the</strong>reis a “paucity” of research onyoung climbers, <strong>the</strong>ir reviewallowed <strong>the</strong>m to draw someconclusions:• Climbers under 16 should not dointensive finger strength training.• A young person’s final growth spurt(usually around age 14 or 15) is associatedwith increased risk of injury.Growth charts (height and shoe size)may help in identifying spurts.• A force producing a torn ligamentin an adult is likely to produce moredamage in a growing youngster.• Up to around age 12, children havea limited capacity to benefit fromintensive strength training, but possessan accelerated capability formotor development. This suggeststraining at this age should focuson volume and diversity of climbingroutes to improve technique andmovement skills, ra<strong>the</strong>r than purestrength.• Wearing excessively tight climbingshoes is not recommended in growingfeet to help prevent foot injuriesand deformities.• Climbers should be educated in<strong>the</strong> importance of appropriate dietand timing of meals for health andperformance.• Knowledgeable and qualified personnelshould monitor young climbers’training. When training intensityis increased, it should employ safeand effective exercises for a givengender and biological age, independentof any competition calendar.According to two UK-basedwebsites, www.ukclimbing.comand www.<strong>the</strong>bmc.co.uk, <strong>the</strong>International Federation ofSport Climbing implicitlyincorporates some of <strong>the</strong>seguidelines in its rules, whichprohibit international competitionat <strong>the</strong> adult level forclimbers under 16. But as<strong>the</strong> popularity of competitionclimbing grows—and as more14- and 15-year-olds performat an adult level—<strong>the</strong> pressureon talented young climbersto train harder is likely to increase,according to <strong>the</strong> AAC.Its abstract, titled Review of<strong>the</strong> Physiological Responsesto Rock Climbing in YoungClimbers, sellsfor $12.

EXPLORATION NEWSDr. Ballyhoo,I Presume?by Jeff Wozer<strong>The</strong> word expedition is <strong>the</strong> Frank’s RedHot Sauceof <strong>the</strong> English language. Add it to any outdoorendeavor—kayaking, camping, snow-shoeing—andit immediately transforms <strong>the</strong> activity into a worldclass<strong>adventure</strong>.I reached this conclusion after attending a climbingpresentation sponsored by an outdoor club. <strong>The</strong>speaker—a short, stocky guy with <strong>the</strong> body of a bigtoe—detailed with humdrum photos and monotonecommentary a summit he and three longtime climbingbuddies completed in <strong>the</strong> Canadian Rockies.During <strong>the</strong> presentation he repeatedly referred to<strong>the</strong> climb as an expedition when it sounded andlooked more like a vacation among three friends enjoyingan escape from middle-age responsibilities.I <strong>the</strong>n wondered to myself, if his talk had been advertisedas a reportage on climbing vacation, as opposedto a climbing expedition, would I, or anyone,have attended? In my case, <strong>the</strong> answer was clearlyno. But from a marketing standpoint it made puresense. As I pedaled home from <strong>the</strong> presentationo<strong>the</strong>r questions thumped through my skull: Howmany o<strong>the</strong>r noted expeditions, when shucked of <strong>the</strong>hype, were little more than disguised vacations?I began researching expeditions, past and present,and realized that, until <strong>the</strong> mid-twentieth century,<strong>the</strong>y possessed a clarity of purpose—<strong>adventure</strong>rsopening territories and minds with <strong>the</strong>ir daringand delving. Today, articulated purpose no longerranks as <strong>the</strong> defining standard for expedition classification;<strong>the</strong> goal, instead, is being photographedshouldering a backpack in <strong>the</strong> presence of peaks,puffins, penguins, or pygmies.With less uncharted turf to explore, a keenereye is required to discern relevance from folly.True expedition aces such as Michael Fay, WillSteger, and Wade Davis, who still roam <strong>the</strong>fringes, are proof that expeditions, in <strong>the</strong> honestsense, can still exist without relying on false hypeor gimmickry.To help sift <strong>the</strong> true from <strong>the</strong> trite, <strong>the</strong> planetneeds a World Expedition Court, presided over by<strong>the</strong> honorable Sir Edmund Hillary. <strong>The</strong>re would beno hearings, only exams. Each applicant would berequired to answer a series of questions related tohis or her specific endeavor. Questions like:1. You hope <strong>the</strong> photos snapped on your trek will:A. Aid scientific researchB. Inspire o<strong>the</strong>rs into a life of <strong>adventure</strong>C. Attract new friends on MySpace2. You embarked on this <strong>adventure</strong> because:A. You wanted to bring attention to <strong>the</strong> Antarctic’s diminishingice shelvesB. You wanted to study indigenous mountain culturesC. You wanted to fur<strong>the</strong>r delay finding a real job3. While stargazing with your expeditionary partyA. Every constellation in <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Hemisphere was identifiedB. Debate raged over Pluto’s doubtful status as a planetC. A commuter plane was mistaken for a meteor4. During your trek, most of your time was devoted to:A. Ga<strong>the</strong>ring soil samplesB. Collecting ice coresC. Snapping spirited photos of yourself with <strong>the</strong> hope of appearingin Patagonia’s upcoming fall catalogue5. <strong>The</strong> greatest scientific discovery made during your trek was:A. Concluding that Bering Sea tides are diurnalB. Finding ammonite fossils in Nepal’s Kali Gandaki ValleyC. Seagulls love CheetosAnyone answering “C” to any of <strong>the</strong> questionswould be denied use of <strong>the</strong> word expedition formarketing purposes. And, as a penalty for wastingSir Edmund Hillary’s time, get whacked across<strong>the</strong> shins with a Leki trekking pole and forcedto watch a PowerPoint presentation of someoneelse’s mountain vacation.biographyJeff Wozer (www.jeffwozer.com) works as a nationally touringstand-up comedian based in Denver.<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

Oceans 8around <strong>the</strong> worldby kayakby Jon BowermasterIf <strong>the</strong>re was a single moment that launched myquest to kayak around <strong>the</strong> world, one continent ata time over eight years, it came in 1999 during anexpedition to <strong>the</strong> Aleutian Islands, on a tiny rockoutcropping in <strong>the</strong> Bering Sea called Chuginadak.Four of us had come in a pair of six-meter-longkayaks to a region known as <strong>the</strong> Birthplace of <strong>the</strong>Winds. Constant fog, 2ºC water, and ripping windsthat reached 95 kilometers per hour had doggedus for weeks. It was <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> trip, and we hadsuccessfully navigated among five snow-cappedvolcanoes and climbed to one 1,800-meter peak,and now, after 30 days at sea, we were waiting tobe picked up by fishing boat.As I sat on <strong>the</strong> black volcanic sand, strainingto hear <strong>the</strong> welcome putt-putt-putt of our boatthrough <strong>the</strong> fog, I tried to imagine what it had beenlike for <strong>the</strong> Aleuts, who populated <strong>the</strong>se islandsthousands of years before and had been among<strong>the</strong> first to use sea kayaks—same frigid seas, samedense fog, same big winds, very different technology.Instead of Kevlar and Gore-Tex, <strong>the</strong> Aleutshad relied on whalebone and sealskin.As I watched <strong>the</strong> cold surf pound <strong>the</strong> shore, I realizedthat despite <strong>the</strong> differences in our craft, <strong>the</strong>Aleuts and I had one thing in common: a great lovefor being on <strong>the</strong> sea, in small boats, wanderingfreely, reaching hidden coves and tiny beachesinaccessible to <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> world. I was cold,tired, and anxious to be back in civilization, yet allI could think as I sat on that beach was: where togo next.<strong>The</strong> answer came quickly: <strong>the</strong> coast of Vietnam.For me, it was a logical leap. A voyage <strong>the</strong>rewould be completely different from <strong>the</strong> Aleutianexpedition, during which we had seen no oneand endured long days of cold but relatively shortpaddles in <strong>the</strong> frigid water. In Vietnam, we would14

Off AlaskaWe paddle toward <strong>the</strong> volcanic island of Uliaga, one of <strong>the</strong>Islands of Four Mountains we kayaked to and climbed in <strong>the</strong>heart of <strong>the</strong> Aleutian chain. Photo by Barry Tessman.<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

in croatiaWe paddle beneath a 12-meter, horseshoe waterfall onCroatia’s Zrmanja River, which flows into <strong>the</strong> Adriatic. Photoby Peter McBride.

have long, hot days of paddling and were guaranteedto see hundreds, thousands of peopleeach day. What’s more, one third of Vietnam’s77 million people lives and depends on <strong>the</strong>sea, and I had long been fascinated by Vietnam,especially <strong>the</strong> north.With that transition from <strong>the</strong> cold BeringSea to <strong>the</strong> warm South China Sea, <strong>the</strong> ideafor OCEANS 8 was born. Our <strong>the</strong> goal wouldbe to visit each of <strong>the</strong> seven continents, plusOceania, by sea kayak. Team rosters, whichvaried from trip to trip, included photographers,videographers, environmentalists, andlocal experts. To date we’ve completed sevenof <strong>the</strong> eight expeditions. As you read this, wewill have embarked on our eighth and final journey,to Antarctica’s Larsen Ice Shelf.So far, <strong>the</strong> eight-year project has taken usfrom <strong>the</strong> Aleutians to Vietnam, to <strong>the</strong> TuamotuArchipelago—78 coral-reef atolls in <strong>the</strong> SouthPacific—to <strong>the</strong> high, arid Altiplano of SouthAmerica, on a circumnavigation of Gabon’sfirst national park and, most recently, an explorationof <strong>the</strong> 1,200 Adriatic islands off <strong>the</strong>coast of Croatia.Our experiences have been marvelously variedthroughout our journeys, from paddling infour-meter swells off a barely visible coral reefin <strong>the</strong> South Pacific to facing down wadinghippos off <strong>the</strong> coast of Gabon. We’ve been inspiredby <strong>the</strong> lives of <strong>the</strong> people we have met,from <strong>the</strong> commercial squid fishermen in Vietnam’sHa Long Bay to <strong>the</strong> solitary urchin-diversoff Antofagasta in nor<strong>the</strong>rn Chile. In 2006, wewent halfway around Tasmania, ending in itsremote Furneaux Group of islands in <strong>the</strong> BassStrait, where we encountered <strong>the</strong> wildest seasyet–yet because Antarctica may offer us ourgreatest challenge, with its frigid temperaturesand kayak-crushing icebergs.<strong>The</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong> world’s oceans face mountingenvironmental challenges, from <strong>global</strong>warming, pollution, and overfishing, has addedresonance to each expedition, making our finaljourney to Antarctica all <strong>the</strong> more important.If <strong>the</strong> surface of <strong>the</strong> Earth is truly onesingle, complex system, <strong>the</strong>n Antarctica is itsheart, <strong>the</strong> slowly beating pump that drives <strong>the</strong>whole world. Each austral winter, an 18-million-

square-kilometer halo of sea ice forms around<strong>the</strong> continent, and each spring, trillions of tonsof fresh water are released into <strong>the</strong> ocean as itthaws. This is <strong>the</strong> planet’s great annual climatecycle, <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>rmodynamic engine that drives <strong>the</strong>circulation of ocean currents, redistributing <strong>the</strong>sun’s heat, regulating climate, forcing <strong>the</strong> upwellingof deep-ocean nutrients, setting <strong>the</strong> tempo of<strong>the</strong> planet’s wea<strong>the</strong>r. <strong>The</strong> Antarctic affects all ourlives, but through forces so deep and elementalthat we’re not even aware of <strong>the</strong>m.Our Larsen Ice Shelf Expedition will providean empirical look at how <strong>the</strong> seventh continent ischanging and evolving and dramatically influencing<strong>the</strong> world’s oceans. <strong>The</strong> eastern side of <strong>the</strong>Antarctic Peninsula is seldom seen ei<strong>the</strong>r by scientistsor <strong>explorers</strong>, because it is more exposed tobig seas and rapidly changing wea<strong>the</strong>r, unprotectedby big islands as are <strong>the</strong> better-known parts of<strong>the</strong> western side of <strong>the</strong> peninsula.In March 2002, scientists watched <strong>the</strong> Antarctic’s500-billion-ton Larsen-B ice shelf shatter intothousands of tiny icebergs before <strong>the</strong>ir eyes. Itsbreak-up was an early warning sign. <strong>The</strong> peninsularice shelves are considered among <strong>the</strong> firstindicators of <strong>global</strong> warming. What happened sodramatically to <strong>the</strong> Larsen Ice Shelf suggests <strong>the</strong>rest of <strong>the</strong> peninsula’s ice may one day calve ordeteriorate. No one knows how quickly that willhappen. All this warming and shifting is also havingclear and extremely troubling impact on lifearound its shores. We intend to get as close aswe can to what remains of <strong>the</strong> Larsen Ice Shelf, todocument from sea level how it is today.<strong>The</strong> thread running through all of my expeditionshas been <strong>the</strong> kayaks, which serve as floating ambassadors.It wouldn’t be <strong>the</strong> same to approach<strong>the</strong>se places by Zodiac or fishing boat, or by road.In <strong>the</strong> kayaks we have been able to reach seldomseencorners of <strong>the</strong> world, examine <strong>the</strong> health of<strong>the</strong> oceans from sea level and come face-to-bowwith people whose lives are inextricably tied tothose oceans.Each expedition has been a unique <strong>adventure</strong>.<strong>The</strong> logistical challenges have been enormous,leading to <strong>the</strong> occasional snafu—such as having<strong>the</strong> boats mistakenly delivered to Ho Chi MinhCity ra<strong>the</strong>r than to Hanoi. We’ve struggled tonavigate through ice, through fog, through stormyseas, and through politics. No one, for example,had previously sought permission to take kayaksalong <strong>the</strong> coast of nor<strong>the</strong>rn Vietnam. When I approached<strong>the</strong> Foreign Press Center in Hanoi forpermission in 2000, I was greeted by a directorwith a smile and a cloud of cigarette smoke.“That… will…be…quite…impossible,” he said.<strong>The</strong> year that followed was full of tense, on-again,off-again negotiations with <strong>the</strong> government, whichultimately led to an arrangement whereby I wouldpay a healthy fee for a “filming permit” to be allowedto bring <strong>the</strong> kayaks and <strong>the</strong> team into <strong>the</strong>country. We also had to agree to take along anofficial monitor—a non-swimming, ocean-hating,Elvis-loving, pro-Communist monitor named LinhCua, who kept to his post for every paddle strokedown 1,800 kilometers of coastline, from <strong>the</strong> Chineseborder to Hoi An.While Linh was a slightly disconcerting additionto <strong>the</strong> team, Vietnamese-born social worker andtranslator Ngan Nguyen was a delight. I’d foundNgan, who grew up in New Orleans, through aninternet site read by resettled Vietnamese refugees.Her fa<strong>the</strong>r had been a helicopter pilot with<strong>the</strong> South Vietnamese Air Force, and on <strong>the</strong> lastday of <strong>the</strong> war in 1975 he’d helped shuttle Americansfrom Saigon to a waiting ship. As a reward,he was allowed to bring his family aboard; Nganwas three years old. She grew up to graduatefrom Tulane, <strong>the</strong>n receive a master’s in internationalrelations from Tufts, and she had returnedto Vietnam several times, including a trip in 2000as part of <strong>the</strong> delegation that accompanied PresidentClinton.Though Ngan admitted she wasn’t an experiencedkayaker, we welcomed her to our teambecause of her knowledge of <strong>the</strong> country. Andbecause she was a sou<strong>the</strong>rner traveling for <strong>the</strong>first time in <strong>the</strong> north, each day was a revelationfor her, and thus for <strong>the</strong> team, especially when wepaddled <strong>the</strong> Ben Hai River, which was <strong>the</strong> dividingline between north and south. As we slipped <strong>the</strong>kayaks into <strong>the</strong> river that day, I noticed Ngan wascrying. Rubbing <strong>the</strong> back of her hands across hercheeks, she explained <strong>the</strong>re were two reasons forher tears: first, she had always imagined arriving in<strong>the</strong> north from <strong>the</strong> south, as a victor, and second,because this man-made line, drawn in a Genevaconference room in 1954, had in part resulted in<strong>the</strong> deaths of more than three million Vietnamese,from both sides of <strong>the</strong> tragic conflict.By contrast, on our Oceania trip, we found <strong>the</strong>Tuamotus to be sparsely populated and remote.18

In <strong>the</strong> South Pacific we saw sharks every day, including this pack off <strong>the</strong> coral reef of Rangiroa. Photo by Peter McBrideTwelve thousand people live among <strong>the</strong> 78 coralatolls spread over 2,600 kilometers. Known as <strong>the</strong>“Dangerous Archipelago” by seafarers going backas far as Magellan, who first sighted <strong>the</strong> chain in1521, <strong>the</strong> low-lying reefs have sunk countlessships. Our biggest worry during our two-mon<strong>the</strong>xploration of paradise was <strong>the</strong> daily presence ofour companions through <strong>the</strong> coral: sharks.Whe<strong>the</strong>r we were diving to 50 meters or justkicking through crystal shallows among <strong>the</strong> reefs,<strong>the</strong> sharks were with us. Most were of <strong>the</strong> nonaggressivereef variety, but we were occasionallyvisited by big lemonsand grays. One day,off an atoll called Rangiroa,we swam amid300 of <strong>the</strong> three-meterlongcritters as <strong>the</strong>ybumped our kayaks andour legs and nibbled atpaddles.Phase four, <strong>the</strong>South American trip,took place in <strong>the</strong> fallof 2003, when I took ateam of six—two Americans,one Kiwi, oneBriton, two Chileans—on a nearly 4,000-kilometerloop throughSouth America’s Altiplano(nor<strong>the</strong>rn Chile,nor<strong>the</strong>rn Argentina,sou<strong>the</strong>rn Bolivia), aplace where <strong>the</strong> seaused to be. We began<strong>the</strong> expedition at sealevel, paddling in roughwater along <strong>the</strong> 60-meter-high limestone cliffs off<strong>the</strong> coast of Chile and ended it atop <strong>the</strong> 5,915-meterLicancabur Volcano on <strong>the</strong> Bolivian border.After leaving <strong>the</strong> water to make <strong>the</strong> climb to <strong>the</strong>peak—pulling our kayaks behind us on a portagecart—we found evidence of prehistoric ocean everywhere,from remnants of coral and shells mixedin with <strong>the</strong> high, dry sand to <strong>the</strong> biggest salt lakein <strong>the</strong> world, Salar de Uyuni, which is spread overmore than 12,500 square kilometers in Bolivia.Searching for water in <strong>the</strong> driest place on Earth,dragging kayaks into <strong>the</strong> 4,300-meter-high desertmay seem quixotic, but we were drawn by <strong>the</strong>intense beauty of <strong>the</strong> high, mineral-rich lakes, aswell as by <strong>the</strong> thought that every step we took hadonce been covered by ocean.Each expedition has brought its own hardships.In <strong>the</strong> cold seas of <strong>the</strong> Aleutians, we figured that ifwe capsized we had 15 minutes to live. <strong>The</strong> SouthPacific, as blue and perfect as it was, delivereda nasty staph infection that spread to four of ourfive team members. <strong>The</strong> Altiplano was high anddry, sucking air from our lungs as we paddled andclimbed. In Croatia, camps on <strong>the</strong> 1,200 islandswere few and far between, which meant sleepingon tiny spits of rockand sand, or on cementboat docks. Butby far <strong>the</strong> most physicallyexhausting wasour fifth trip, in 2004,when photographerPeter McBride, environmentalistJ. MichaelFay, and two Africans,Sophiano Etouck andAime Jessy, joined mein Gabon.In this small WestAfrican nation, wecircumnavigated <strong>the</strong>country’s first nationalpark, Loango. <strong>The</strong> combinationof unrelenting38ºC heat; little food;long, long days on <strong>the</strong>ocean; and a three-dayjungle portage took aheavy toll. For me, <strong>the</strong>physical challenge washeightened by <strong>the</strong> factthat I was traveling with Fay, who had gained acclaima few years back for spending 453 daysstraight walking across <strong>the</strong> Congo.Yet, as always, <strong>the</strong>re were astonishing rewards.After paddling into high winds across wide lakes,<strong>the</strong>n up a 70-kilometer river—spending one nightsleeping in our kayaks in a flooded forest—wespent several days on <strong>the</strong> ocean. <strong>The</strong> typical dayended with a beautiful equatorial sunset formingbehind us, and we sat in <strong>the</strong> surf zone, not quiteready to paddle in to <strong>the</strong> beach, despite havingbeen in <strong>the</strong> kayaks for eight hours. As we backpaddled,being gently pushed toward <strong>the</strong> sandy<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

shore by two-meter seas, first one, <strong>the</strong>n ano<strong>the</strong>rforest elephant lumbered onto <strong>the</strong> beach.We bobbed and watched as a pair of hipposheaded into <strong>the</strong> surf for a swim. A moment latera small family of buffalo waded into <strong>the</strong> water.“Damn!” said Fay. “Noah’s ark, right <strong>the</strong>re infront of us. For sure, no one has ever seen sucha sight from <strong>the</strong> seat of a kayak!” That’s beenour goal. To use <strong>the</strong> kayaks to go to places wecouldn’t get to o<strong>the</strong>rwise.acknowledgments<strong>The</strong> author would like to acknowledge <strong>the</strong> support of <strong>the</strong>National Geographic Society’s Expeditions Council andseveral loyal corporations, including Mountain Hardwear,Werner Paddles, Necky Kayaks, Timberland/Mion, O.R.,who have made <strong>the</strong> Oceans 8 expedition possible.biographyFellow of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong> <strong>Club</strong>, Jon Bowermaster is postingupdates on his expedition at www.jonbowermaster.com.20

In GabonOur run-ins with large animals were <strong>the</strong> most spectacularpart of our paddling days. Here, a herd of elephants cross alagoon just in front of us. Photo by Peter McBride.<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

sir WallyHerbertmaster of <strong>the</strong> icetext by Nick Smithpaintings by sir wally herbertWhen Sir Wally Herbert died earlier this year, tributespoured in for <strong>the</strong> greatest polar explorer since <strong>the</strong>golden age of Scott and Shackleton. He was also anaccomplished artist, whose paintings have just beenpublished in a new book, <strong>The</strong> Polar World.“You have to understand,” says Kari Herbert, <strong>the</strong>explorer’s daughter, “while Dad was fiercely proudof his achievements, records didn’t mean much tohim unless <strong>the</strong>y were underpinned by geographicalresearch. <strong>The</strong> whole point of <strong>the</strong> British Trans-ArcticExpedition back in <strong>the</strong> late 1960s wasn’t to be <strong>the</strong>first to reach <strong>the</strong> North Pole. But on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand,while you’re up <strong>the</strong>re…”Inevitably Sir Wally Herbert’s fame will rest on <strong>the</strong>fact that he was <strong>the</strong> first to make a surface crossingof <strong>the</strong> Arctic Ocean along its longest axis. This feathas never been repeated, leading some historiansto call it “<strong>the</strong> last great journey on Earth.”During this expedition in <strong>the</strong> late 1960s he alsobecame—along with his three companions, FritzKoerner, Allan Gill, and Ken Hedges—<strong>the</strong> first man22

Self-portrait, facing page, endurance, aboveto walk to <strong>the</strong> North Pole. Unlike Edmund Hillary’sfirst ascent of Everest or Roald Amundsen’s attainmentof <strong>the</strong> South Pole, Sir Wally’s achievement hastaken longer to pass into <strong>the</strong> annals of exploration.Maybe it was because events at <strong>the</strong> top of <strong>the</strong>world were overshadowed by <strong>the</strong> lunar landings,or by <strong>the</strong> contested claims of Admiral Robert E.Peary or Dr. Frederick A. Cook, but recognitionfor <strong>the</strong> success of Sir Wally and his men has beena slow burner. In <strong>the</strong> 1980s, he took matters intohis own hands when he published <strong>the</strong> meticulouslyresearched Noose of Laurels, an analysisof Peary’s claims concluding that <strong>the</strong> commanderhad not reached <strong>the</strong> pole. <strong>The</strong> polar communitynow accepts that April 6, 1969, is <strong>the</strong> date thatcounts, a date Sir Wally hammered home in his<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

polar bear on <strong>the</strong> ice<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

painting North Pole Group No. 1, 6th April 1969.It may seem unfair, but <strong>the</strong> sheer scale of SirWally’s achievement is not widely recognizedoutside <strong>the</strong> exploration community. Yet <strong>the</strong> factsof his career as a polar explorer are simply extraordinary.Over <strong>the</strong> span of half a century he traveledwith dog teams and open boats more than 40,000kilometers—over half of that distance through virginterritory. A formidablecartographer andsurveyor, he mappedsome 75,000 kilometersof new countryin Antarctica andretraced <strong>the</strong> routes ofsome of <strong>the</strong> greatest<strong>explorers</strong> in history.Few have contributedmore to ourunderstanding of <strong>the</strong>native Inuit of northwestGreenland. Hepublished ten books, received many medals andawards, including <strong>the</strong> coveted Explorer’s Medal in1985, and was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II on<strong>the</strong> last day of <strong>the</strong> second millennium “for servicesto polar exploration.”What is not so well known is that he was anextraordinary artist, which his last book, <strong>The</strong> PolarWorld, makes clear. Nearly all of Sir Wally’s paintingshave been brought toge<strong>the</strong>r for <strong>the</strong> first time.Nearly all, says Kari, because <strong>the</strong>re are “four orfive paintings that are ei<strong>the</strong>r lost or are hard totrack down. I’d like to hear from anyone who hasone that is not reproduced in <strong>The</strong> Polar World.”Sir Wally was a commercial artist in <strong>the</strong> sensethat he painted for a living—this means much ofhis work has disappeared into private collections.Reinhold Messner commissioned both Everestand <strong>The</strong> Landfall of <strong>the</strong> James Caird on SouthGeorgia, included in <strong>the</strong> book, despite having noobvious polar association. Kari remembers as achild watching <strong>the</strong> paintings grow over time only tosee <strong>the</strong>m packed up and shipped off to <strong>the</strong> client“almost before <strong>the</strong> paint had dried.” Sir Wally wasin <strong>the</strong> habit of commissioning high-quality, largeformatplate photography of his finished work andit is from <strong>the</strong>se transparencies that much of <strong>the</strong>book has been assembled.And yet Sir Wally might never have becomean artist, despite showing a talent for drawing26at school. Kari explains, “When dad retiredfrom expeditions in <strong>the</strong> early 1980s, he officiallybecame a full-time writer—that’s how he earnedhis living. But <strong>the</strong> book deals dried up a bit.”Despite his fame, he met with little successwhen hawking his book proposals. “He was gettingfed up with being rejected and I think mumthought it would be a good idea for him to takeup painting again torelieve <strong>the</strong> stress.”Reluctant to do thisat first, he soonfound that his childhoodaptitude forart had coalescedwith his professionalexpertise indraftsmanship andcartography to producepaintings thatnot only attracted acommercial market,but gained <strong>the</strong> attention of <strong>the</strong> likes of HRH <strong>the</strong>Prince of Wales, who in Kari’s words, “becamedad’s biggest fan.”His “biggest fan” has described Sir Wallyvariously as a “genius” and “a national treasure,”but to Kari, who is an accomplished writer andphotographer in her own right, “my dad was <strong>the</strong>embodiment of <strong>the</strong> polar world and so it follows heshould paint it.” <strong>The</strong> Polar World is an extraordinaryepitaph to a man of many gifts—writer, painter,genuine explorer of <strong>the</strong> old school, and one of <strong>the</strong>great men of <strong>the</strong> twentieth century.informationCopies of <strong>The</strong> Polar World are available from Polarworld Booksin standard hardback edition (£35) or in two special limitededitions: lea<strong>the</strong>r hand-bound, £499 and cloth, £240. Forinformation, contact: kari@kariherbert.combiographyA Fellow of <strong>the</strong> Royal Geographical Society, Nick Smith isa writer and photographer specializing in exploration andtravel. He is also literary editor of Bookdealer magazine. Hiswork has appeared in publications from <strong>the</strong> Daily Telegraph toCountry Life.North Pole Group No 1 6th April 1969

a pioneering journey: Sir wally herbert in his own wordsFour men, four teams of dogsIn this extract from <strong>The</strong> Polar World, Sir Wally described<strong>the</strong> tensions on <strong>the</strong> eve of setting out on <strong>the</strong> first surfacecrossing of <strong>the</strong> Arctic Ocean.On 20th February l968: “I signalled <strong>the</strong> pilot of <strong>the</strong> Dakotawith a nod. Our mission was to find a way onto <strong>the</strong> driftingpack ice, and our position at that time was about 80 miles[129 km] of ENE of Barrow. He eased <strong>the</strong> plane into a turnand took one last look to <strong>the</strong> north. <strong>The</strong> vast expanse ofdrifting ice was awesome—limitless. To <strong>the</strong> south, weak raysof sunlight pierced <strong>the</strong> clouds and scattered <strong>the</strong> ice withpatches of light. Cracks and open leads caught <strong>the</strong> sun likemolten silver and darted around on <strong>the</strong> surface of <strong>the</strong> packbefore turning into jet black scars that marked <strong>the</strong> blue-greyskin of <strong>the</strong> frozen sea. It was a moment of profound relief—<strong>the</strong> moment of decision. Tomorrow, four men and four teamsof dogs would set out on a journey from which <strong>the</strong>re couldbe no turning back.Our proposed journey along <strong>the</strong> longest axis of <strong>the</strong> ArcticOcean would be a pioneer journey—a horizontal Everest thatwould mark each one of us for life. Our beds, most nights,would be on ice no more than two meters thick (and oftenvery much thinner); ice which might at any time split orstart to pressure. <strong>The</strong>re would not be a day during <strong>the</strong> next16 months when <strong>the</strong> floes over which we were travelling,or sleeping off our fatigue, would not be drifting with <strong>the</strong>currents or driven by <strong>the</strong> winds. <strong>The</strong>re would be no end to<strong>the</strong> movement; no rest, no landfall, no sense of achievement,no peace of mind, until we reached Spitsbergen. Most importantly:<strong>the</strong>re was no possibility whatsoever of rescue.By midnight on <strong>the</strong> eve of our departure <strong>the</strong> pace of preparationhad slackened, and on that day I received a parcel fromhome containing <strong>the</strong> Union Jack and a note from my fa<strong>the</strong>r,which simply read: ‘You forgot your flag—good luck.’ I was sotouched by this correction that I took it on <strong>the</strong> journey. Thatlast night at Barrow I remember very well—it felt like <strong>the</strong> eveof a battle—still, clear, cold, silent, with no one sleeping; anatmosphere heavy with private thoughts. I felt as though I wasin a trench in <strong>the</strong> First World War along with <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs—wefixed our bayonets and just waited for <strong>the</strong> first weak light ofdawn and for <strong>the</strong> young lieutenant to blow his whistle, whereupon,almost numb, we would all scramble out to face our fate.I was physically sick with fear, and <strong>the</strong> weight of <strong>the</strong> trust thatmy three companions had in me. Which of <strong>the</strong>se two was <strong>the</strong>greater, I still do not know—even to this day.I unlatched <strong>the</strong> huge doors of <strong>the</strong> warehouse and spread<strong>the</strong>m open. <strong>The</strong> night was almost over. It was calm, clear,and very cold. <strong>The</strong> sledge moved over <strong>the</strong> floor on rollers,bit <strong>the</strong> snow, and slid forward, out into a deserted streetsmoke-grey in seeping twilight. I left it facing north-east at<strong>the</strong> end of two rows of day-bleached lights that pointed aperspective arrow south-west down <strong>the</strong> main street. <strong>The</strong>rewas not a breath of wind to dissipate <strong>the</strong> plumes of vapourthat hung over each box-like building—<strong>the</strong> camp was still andsleeping and <strong>the</strong> only sound was of <strong>the</strong> throbbing warmthwithin each man-made shelter.”And so <strong>the</strong> scene was set at Point Barrow, Alaska, on 21stFebruary l968 for <strong>the</strong> final farewells, and <strong>the</strong> start of whatmost historians now regard as <strong>the</strong> “last of <strong>the</strong> great pioneeringjourneys made on <strong>the</strong> face of <strong>the</strong> Earth.”<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

Abandonedin <strong>the</strong> ArcticAdolphus W. Greelyand <strong>the</strong> Lady Franklin Bay Expedition, 1881–1884by Geoffrey E. ClarkOn March 27, 1935, a small contingent of mounted General Adolphus W. Greely. It was only <strong>the</strong> fourthcavalry leading a military band, and a government time in <strong>the</strong> nation’s history that <strong>the</strong> medal had beenlimousine flying <strong>the</strong> flag of Secretary of War George presented for peacetime service. Few of <strong>the</strong> neighborsH. Dern pulled up in front of a modest house on “O” surrounding <strong>the</strong> porch had any idea why <strong>the</strong> honor wasStreet in <strong>the</strong> quiet Georgetown section of Washington, being bestowed and <strong>the</strong>y were not enlightened whenD.C. As newsreels captured <strong>the</strong> event, Secretary Dern <strong>the</strong> citation was read. It made no mention of <strong>the</strong> pivotalpresented <strong>the</strong> Congressional Medal of Honor to an chapter in Greely’s career: his three years as leaderelderly, but erect retired military officer, Major of <strong>the</strong> fateful Lady Franklin Bay Expedition.Greely at <strong>the</strong> wheel of <strong>the</strong> rescue ship <strong>The</strong>tus in 1884, courtesy NARA28

An Illustration from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper shows <strong>the</strong> dead being brought aboard <strong>the</strong> Bear in 1884In 1881, Greely and a group of 25 men establisheda frigid outpost <strong>the</strong>y named Fort Conger, just725 kilometers from <strong>the</strong> North Pole on EllesmereIsland. <strong>The</strong>y conducted scientific research andexploration as part of <strong>the</strong> first International PolarYear. When in 1883, a ship failed to appear tobring <strong>the</strong>m home, Greely and his men fell back ona pre-arranged plan to retreat 400 kilometers southalong <strong>the</strong> coast of Ellesmere to Cape Sabine onPim Island, where a year’s worth of supplies, if nota ship, was to await <strong>the</strong>m.<strong>The</strong> retreat south proved to be an agonizing,two-month ordeal over treacherous, moving ice.When Greely and his men finally arrived at CapeSabine in mid-October, <strong>the</strong>y were horrified to findnone of <strong>the</strong> promisedsupplies had been left.In preparation for <strong>the</strong>coming winter, <strong>the</strong>y constructeda stone house,which <strong>the</strong>y christenedCamp Clay. <strong>The</strong> monthsthat followed broughta descent into a frozenhell of starvation, madness,and suicide. Allbut one man managedto survive <strong>the</strong> winter,but with <strong>the</strong> coming ofspring <strong>the</strong> men began torapidly die of scurvy orstarvation. Unbelievably,two relief expeditionsorganized by <strong>the</strong> U.Sgovernment to re-supplyand <strong>the</strong>n retrieve <strong>the</strong> Greely expedition had failed,leaving <strong>the</strong> men’s fate unknown. When a navalrescue mission—instigated in part by a determinedHenrietta Greely and led by Commander WinfieldScott Schley—finally reached <strong>the</strong> men on June 22,1884, <strong>the</strong> few remaining members of Greely’sparty were within hours of death. Tragically, <strong>the</strong>world would soon learn that only Greely and six ofhis men had managed to survive.When <strong>the</strong> expedition returned to <strong>the</strong> UnitedStates on August 4, 1884, <strong>the</strong> survivors and<strong>the</strong>ir rescuers received a tumultuous receptionin Portsmouth, New Hampshire, very unlike <strong>the</strong>modest ceremony on “O” Street 50 years later.Greely’s men had not only completed <strong>the</strong>ir missionand brought back all of <strong>the</strong>ir data—includingmeteorlogical measurements, observations oftides, magnetism, and gravity, as well as biologicaland ethnological studies—<strong>the</strong>y had also claimed anew record for <strong>the</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>st north, which had beenheld by <strong>the</strong> British for 300 years.Within days of <strong>the</strong> joyous welcome home, however,ugly stories began to appear in <strong>the</strong> newspapers,alleging that <strong>the</strong> expedition’s dead had beencannibalized to support <strong>the</strong> living. Despite <strong>the</strong> factthat <strong>the</strong> rescuers had found at least six corpsesstripped of <strong>the</strong>ir flesh, <strong>the</strong> survivors, to <strong>the</strong> end of<strong>the</strong>ir days, denied any involvement. Greely’s onlycomment was, “I know no law of God or man thatwas broken at Cape Sabine.”Sadly, <strong>the</strong> Lady Franklin Bay Expedition’s heroicchapter in Arcticexploration slipped intoobscurity, clouded byaccusations of governmentincompetence,needless loss of life,and <strong>the</strong> ultimate taboo.During Greely’s lifetime,o<strong>the</strong>r polar <strong>explorers</strong>,particularly Robert E.Peary, avoided himand years later in 1961,Wilhjalmur Stefanssonrecalled that a hushwould fall wheneverGreely entered <strong>the</strong>room. <strong>The</strong> last livingperson to meet <strong>the</strong> general,Thaddeus Thorn,recalled him beingreferred to by <strong>the</strong> neighborhood boys as, “eat ‘emalive Greely.”So what is <strong>the</strong> real truth about this fascinating,accomplished man, who, among o<strong>the</strong>r things,served as <strong>the</strong> first president of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Explorers</strong><strong>Club</strong>? Should he be remembered as a hero, avictim, or a villain?<strong>The</strong>se were <strong>the</strong> questions that came to mindwhen I read Greely’s account, Three Years ofArctic Service, in preparation for a 1988 campingtrip with my wife and eldest son on <strong>the</strong> shores ofLake Hazen—<strong>the</strong> largest lake north of <strong>the</strong> ArcticCircle—which was some 80 kilometers northwestof Fort Conger. This story of heroism and villainy,personality conflicts, and coincidences, as well aspolitical shenanigans, seemed more like a work of<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

fort congercarl ritterellesmeregreenlandcape sabine on pim island

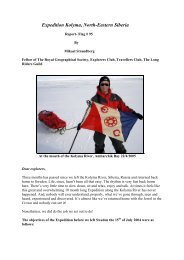

fiction than a factual account. During our trip,we had an opportunity to visit Fort Conger andsee <strong>the</strong> remains of Greely’s camp—<strong>the</strong> artifactswell preserved in <strong>the</strong> cold dry climate. It was<strong>the</strong>n that I realized I wanted to bring this importantepisode in <strong>the</strong> history of Arctic explorationto <strong>the</strong> public’s attention in a documentary film.In <strong>the</strong> summer of 2000, I joined a kayak triporganized by Steven Smith, a professionalguide, outfitter, and field biologist, to kayakfrom Alexander Fiord to Pim Island to see <strong>the</strong>site of Greely’s winter camp near Cape Sabine.When I first asked Steve whe<strong>the</strong>r it would befeasible to retrace Greely’s retreat from FortConger to Cape Sabine with a documentarycrew using inflatable boats, he dismissed <strong>the</strong>idea as being impractical and extremely hazardous.But, after fur<strong>the</strong>r consideration, hethought it possible if he could assemble an expertcrew using kayaks, which could be moreeasily hauled over <strong>the</strong> ice.While doing historical research for <strong>the</strong> project,I was fortunate to meet many of Greely’sdescendants, all of whom were very enthusiasticabout <strong>the</strong>ir ancestor, “<strong>The</strong> General.”Greely’s great-grandson, David Shedd ofBartlett, New Hampshire, suggested that hisson James, <strong>the</strong>n a senior in college, participatein <strong>the</strong> expedition as a representative of <strong>the</strong> family.<strong>The</strong> organizing structure of <strong>the</strong> film quicklyfell into place: we would not simply present <strong>the</strong>historical material, but ra<strong>the</strong>r, actively engage<strong>the</strong> viewer in <strong>the</strong> drama by telling Greely’s storythrough <strong>the</strong> eyes of his great-great-grandson,James Shedd. At <strong>the</strong> same time we would put<strong>the</strong> viewer in touch with <strong>the</strong> spectacular environmentas James retraced <strong>the</strong> party’s arduousjourney down <strong>the</strong> coast of Ellesmere.But James’ ability to participate was by nomeans certain: <strong>the</strong> expedition would be a challengeto <strong>the</strong> most experienced guide and hisexperience as an outdoorsman was limited tocamping in <strong>the</strong> White Mountains with his fa<strong>the</strong>rand skiing. To his credit, James enthusiasticallyundertook preparing himself for <strong>the</strong> challengeby kayaking in <strong>the</strong> Pacific Northwest and undertakinga very strenuous backpacking trip in <strong>the</strong>High Arctic. Ultimately, Steve agreed to takehim on and subsequent events would provethat James more than met <strong>the</strong> challenge.In many ways <strong>the</strong> success of both <strong>the</strong> filmand expedition depended on logistics andcareful organization. Fortunately, <strong>the</strong> projecthad engaged <strong>the</strong> services of two seasonedprofessionals: Steve Smith and Gino DelGuercio of Boston Science Communications.Gino has created award-winning documentariesfor PBS, NOVA, and <strong>the</strong> DiscoveryChannel. While he was an avid outdoorsman,he had never been to <strong>the</strong> Arctic. O<strong>the</strong>r expeditionmembers included professional guideswho had worked with Steve for many years.<strong>The</strong> most difficult step would be arranging<strong>the</strong> transport of <strong>the</strong> team and its equipment toFort Conger, as well as <strong>the</strong> teams subsequentresupply en route. Fuel for <strong>the</strong> Twin Otters and<strong>the</strong> helicopters used for aerial photographywould need to be cached along <strong>the</strong> coast andthat in itself would require expensive transportationand additional fuel.<strong>The</strong> expedition component of <strong>the</strong> documentary—afive-man, one-woman team using threekayaks—would retrace Greely’s journey down<strong>the</strong> coast from Fort Conger to his winter campat Cape Sabine. Since <strong>the</strong> kayaks could notcarry sufficient food and supplies for <strong>the</strong> anticipatedsix- to seven-week expedition, Gino,Tom Stere, and I would serve as <strong>the</strong> supportteam: leapfrogging down <strong>the</strong> coast by planeto resupply <strong>the</strong> team, filming from shore andhelicopter, as well as providing a communicationslink. We would be aided by Scott Simper,a professional <strong>adventure</strong>r videographer, whowas one of <strong>the</strong> kayakers. <strong>The</strong> kayak team alsohad a small video camera that it would use torecord <strong>the</strong> members’ private thoughts during<strong>the</strong> trip. Gino had arranged for ano<strong>the</strong>r cameraman,Simon Reeves, to do filming when <strong>the</strong>team arrived at Cape Sabine.While <strong>the</strong> route and <strong>the</strong> environment wouldbe much <strong>the</strong> same as Greely encountered,<strong>the</strong>re were many important differences: wewould be using <strong>the</strong> very latest in outdoorequipment, and we had access to communicationsvia satellite-phone and high frequencyradio between team members, <strong>the</strong> supportcrew, and <strong>the</strong> outside world. Perhaps <strong>the</strong> mostimportant difference was <strong>the</strong> time of year:<strong>the</strong> <strong>explorers</strong> <strong>journal</strong>

we did not want to risk starting out at <strong>the</strong> end ofAugust with <strong>the</strong> imminent approach of winter. Wechose to embark on our expedition in June, at <strong>the</strong>beginning of <strong>the</strong> brief Arctic summer when <strong>the</strong>reis still-solid sea ice, knowing that after <strong>the</strong> first fewweeks, <strong>the</strong> kayak team would be able to paddlefreely in open water. Greely and his men, who leftalmost three months later, encountered just <strong>the</strong>opposite—ever-worsening ice conditions as <strong>the</strong>yretreated fur<strong>the</strong>r south.We ga<strong>the</strong>red in Yellowknife, capital of <strong>the</strong>Northwest Territories, packed kayaks, gear, andfuel into a chartered De Havilland transport planeand set off for <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rnmost regular airportat Resolute in <strong>the</strong> district of Nunavut. We <strong>the</strong>nregrouped, picked up a Canadian park ranger andcontinued on to Fort Conger in <strong>the</strong> Twin Otter. Avery large area of Ellesmere Island, including FortConger, is in Canada’s nor<strong>the</strong>rnmost nationalpark, and people are not allowed to visit <strong>the</strong> siteof Greely’s camp without official supervision. Welanded in a dry stream bed near Fort Conger,where <strong>the</strong> foundation of <strong>the</strong> station and much ofGreely’s equipment remains to this day.<strong>The</strong> team set out on <strong>the</strong> summer equinox—<strong>the</strong>anniversary of Greely’s rescue in 1884—pulling<strong>the</strong>ir kayaks over 16 kilometers of sea ice across32Lady Franklin Bay. Meanwhile, Gino, Tom, and Itook off to set up our first basecamp at Carl RitterBay. While <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs were exerting <strong>the</strong>mselves,we lived in relative luxury in a huge, six-meter dometent with most of <strong>the</strong> comforts of home.All went according to plan until July 4, when anaccident occurred that could have been tragic for<strong>the</strong> expedition. As Scott attempted to come ashorein his kayak, he became pinned between “<strong>the</strong> icefoot”—ice frozen firmly against <strong>the</strong> shore—and arapidly moving ice floe that was being pushed upand against <strong>the</strong> foot by <strong>the</strong> incoming tide. Scott’skayak was crushed and he was severely injured.If <strong>the</strong> ice had closed in any fur<strong>the</strong>r, Scott wouldhave undoubtedly been killed, but fortunately, itstopped just in time for his kayaking companionsto pull him out.While <strong>the</strong> team waited anxiously for <strong>the</strong> helicopterfor his immediate medical evacuation, <strong>the</strong>y found<strong>the</strong>mselves floating offshore on a cracking ice floe inever-thickening fog, a haunting reminder of Greely’smen drifting in Kane Basin. Thanks to modern communications,<strong>the</strong> Canadian Army detachment at<strong>the</strong> Eureka wea<strong>the</strong>r station, and Peter Jefford, ourhelicopter pilot, Scott was plucked from <strong>the</strong> ice;transported to Iqualuit, <strong>the</strong> capital of Nunavut; and<strong>the</strong>n to Ottawa for intensive medical treatment—all<strong>The</strong> east coast of Ellesmere Island, photo by James Shedd