Lola Haskins Maggie Taylor

Lola Haskins Maggie Taylor

Lola Haskins Maggie Taylor

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Lola</strong> <strong>Haskins</strong><strong>Maggie</strong> <strong>Taylor</strong>Solutions Begin ning with

DedicationsFor D’Arcy and Django, children of my heart<strong>Lola</strong> <strong>Haskins</strong>For Jerry, my generous and patient collaborator<strong>Maggie</strong> <strong>Taylor</strong>

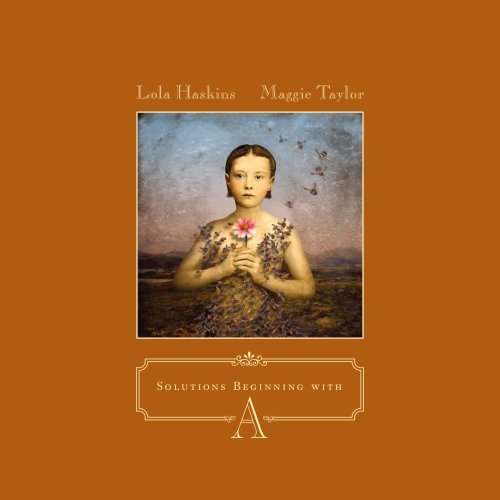

IntroductionSolutions. They come in many different forms. I sometimes think we forget that art can be a solution, whether it bemusical, visual, or the written word. We can be guided by these things in a most wondrous way. And sometimes, thereare solutions within solutions, a collaborative effort.n It is fascinating to me how two independently composed works can synchronistically come together to create awhole new unique piece. Such is the case with Solutions Beginning with A. Most of <strong>Maggie</strong> <strong>Taylor</strong>’s striking montagesand <strong>Lola</strong> <strong>Haskins</strong>’ ethereal stories were created separately and have found each other here in this book; perhaps, assome kind of preordained “solution.” I have personally experienced this particular kind of magic when a lyric I havewritten jibes perfectly with a piece of music I had nothing to do with. The end result seems “meant to be.” I believethese unions are rare and special.n For a moment, cast aside your textbooks, your self-help gurus, and your journal. Open Solutions Beginning with Aand go on a mystical, glorious, and evocative journey with <strong>Maggie</strong> and <strong>Lola</strong>. Become part of the process. Find a solution.And then go on to “B.”Shawn Colvin, 2007

The Compass Points of ANo r t hThe lines of a ladder lean exactly into each other, linked by the thin shelf of whatthey share. One exists for support, but the other may be climbed, with the caveatthat anyone considering the top had better be ready to dive, like closed scissors,into a pool so far below it can scarcely be seen--an act only the experienced survive.Most people consider the risk, then settle for reaching as if for grapes, from the nextrung down. But not us. Although we understand that the stars we see burned outbefore we were born, we don’t care, we want them anyway, yearn up so hard that weoverstretch, and are perpetually in the throes of injury.9

Adr i a nAdrian’s skin was the hole into which colors fall. She was the answer to the beginner’s question, whathappens if I mix all these? She dressed in the black of her arms, otherwise shades of silver, accentedby the dim red of planets seen from earth. She seldom came to the city, but lived on a hill, in a housethe stars would flitter through at night. Sometimes they would be hungry and she would throw themcrumbs from her dreams. Sometimes, when the moon went behind a cloud, they would multiply, and atdawn more would flurry up than had ventured down.n At fifty, Adrian discovered a spot on the back of her hand, and a splotch like a little nebula justabove the left side of her smile. With time, the spots became clusters. She named them: opal, abalone,trine. With Adrian as with others, it is known--such patterns mark the bits of skin which death hasclaimed for itself. But what they are made of is different for everyone. For some, they are shadow, asof sun through noon trees; for others, the escape paths of doubts that have worked their way from theinside like bots from eggs; for others, simply the dust which has splattered on the body from years oftraveling. But Adrian’s were points of light. She had always been a place the stars could feel at home, anda sky has its own stars. But what hers were could not have been clear until now, not until her body hadspent itself making them, bringing them to the surface the way carp rise, beautiful and hungry.12

Ada hAdah’s mother had closets of baby clothes, which she kept sorted by color, the azures and the roses andthe sunlights together. When Adah was taken out, the chubby folds of her legs would end not in toesbut in matching bootees or tiny tennis shoes or miniature Mary Janes, as if she were being carried to adance. From her first remembered moment, Adah experienced the world around her--the dusty greenof summer oak, the flame of Indian paintbrush--as if she were wearing it.n Adah grew up to be an artist of the skin. She knew where the blank spaces on her canvas shouldbe, the parts of her body through which birds might flutter freely, the rests for the ears between notes,the harbors for the eye, weary of beating into the wind. She knew also that the body is music. Shewanted to craft a concerto so unforgettable that someone who’d wandered into the hall by mistake,having to be somewhere else, and soon, would remember her all his life, so that she would wend its wayinto his soul or, more accurately, emerge, since she would never have left, at moments when he thoughthimself alone. At such times there would be a flash of green light as the music settled into the horizon,followed by softening rose, then a blue for which he had no name but peace, spreading like wind dyingon the waves.n Adah meets a woman holding a steaming cup. From this woman Adah learns how kissed coffee canblaze the throat, how the right pinot can turn the mouth edgy, how yellow crumbs will not stay put but insiston lingering on the lips. And now her curious art begins a slow delicious stretch, down through her skininto the organs her body keeps covered. She encounters her intestine, her liver, her contented heart. Andpedalpoint enters her repetoire. And with it, force, as what is unseen impels the more, like weatherbuilding from the west, like the jet stream that speeds a plane to Boston where it lands, the lone aircrafton its runway, on a day so cold that words shatter as they hit the air, and should you cry, your lasheswould turn brittle, and break from your eyes.16

A d a h c o n t i n u e d . . .n Adah moves in with the woman--Adah with her gauzy skirts like wavy-tailed fish, her blouseslike no-moon-black fish or fish with fire-yellow gills. And underneath her skirts uncountable restlessfish, new minnows every dawn to make up for those the ones had been taken in the night. And thoughthis woman never sings herself--her small grey voice walks crippled--she informs Adah’s every note,covered or naked, sotto or soaring. Adah’s skin is lit from inside now, like a house seen from a distanceacross a dark road, in which someone is kissing someone else, kissing so long and so sweetly that thewhole house first glows, then shines, then lifts away.18

Ane m o n eWhen she was little, Anemone would skip along the beach in front of her house singing I am the SeaQueen, I am the Sea Queen. When she started school, the minute her mother’s homecoming car stoppedrolling, she would be away down the long comma of sand, her head bent as if the coastal wind thatchanged the trees were blowing now.n Anemone kept in her room hundreds of shells. Some were twinned--those were her wings.Some were jagged and single--those were her tempers. The bites at the edges were the moments shestamped her feet. The night she was thirteen, Anemone dreamed she had killed every creature whosehouse she owned, pried the muscles loose that tried to hold on. But there was never any blood, andnone of the soft bodies had entered her mouth, had swum even for a moment in that red cave with itsveiny lights.n Anemone’s hair drifted around her face, so blonde it was almost green. Her skin was cool, smooth,translucent as bare nacre. It never browned, never even tinted the way glasses, looking lightward,turn dark. One day she saw a stubble-jawed boy watching her as his hand lingered across the top of hisbathing suit. Walking on the littered beach that afternoon, she noticed a new kind of shell, gnarled andtwisted on the outside. The beautiful spit inside the shell was turning moldy at the edges.n For days Anemone had watched the hurricane on the news, hotter and hotter as it approachedthe coast. Now the wind was up, and her hair was frizzling from her scalp. She was told to leave. Hermother and father had already gone. She’d sworn she’d follow, she wanted to bring her car out. Insteadshe went upstairs.n She remembers floating without will. She can still hear the fish calling each other, the breaths ofloosely-opening flowers on the black ocean floor. She remembers the pull of the root that kept her fromfloating away from here, where it was safe, upward towards the killing light. Her mouth opens andcloses, soft as a kiss. Bright fish, entranced, swim in.20

Ari s t aWhen Arista came home from work, the box was there, leaning against her door. It was nothing she’dordered. What if it exploded as she split the slick brown tape and pried it open with the same knife she’dstood behind her ex-husband with, having just cut an onion into little teary squares. She’d stood therefor some time before she’d lowered the knife to her side.n The box said Handle with Care, Human Eyes. Arista set it on the kitchen table, poured a glass ofscotch. She looked at the wood-wormy cabinets, and dingy counters, scratched as if by a vengeful cat.She opened the pantry door and considered the shelves of cans, many already rusted and bulging. Whatthe hell, she thought. So she took the knife (she still thought of Adam every time she used it), and slitthe lines where the tape showed weakness, carefully so as not to puncture what might be inside. Sheprized open the carton’s cardboard arms.n And there, shrink-wrapped on a nest of shreds sat a pair of eyes, whites bright as shells circlingdeep violet centers. She uncreased the booklet tucked underneath and spread it flat. How to Install, thebooklet began. The instructions were longer than they looked. By the time she finished reading, it wasfull dark, and the view of the alley with its perpetual stink of garbage had been replaced by Arista’s facein the black glass.n Remove the old eyes and discard. Arista got the trick in that. With both eyes out, how could shesee to put new ones in? She decided to do the left first. The instructions had not specified a tool, butthe melon scoop seemed right. She had a small one, just the thing for cold salads when you were in ahurry. Using this, she carefully removed the eye. The replacement popped neatly in. It was dizzying.If she shut her right eye, the lines around her mouth smoothed and vanished, its corners lifted, andsomething sweetened the kitchen air as if birds sang outside, not sobbing like owls but joyful, the sortof outpour she remembered from when she was twenty, waking among mountains, in love with herown visible breath.22

A r i s t a c o n t i n u e d . . .n But if she opened the right eye too, she found herself riding a tilt-a-whirl which no one wouldstop, so she spun and sickened, sickened and spun until her life spilled out green and still she spun. Sheshivered and took up the scoop. This one was harder. The root pulled against her, and she had to cut itloose with the knife.n But finally she got it out, and both eyes stared buried from the trash. She did not relax until sheheard the pre-dawn banging of the pick-up men, carrying them away.n Adjusting to Your New Eyes. From this section, Arista had gathered that adjustment would takesome time. This turned out to be true. The problem wasn’t work. She floated through that, explainingthe change of eye color as contacts. But at first the perfumes disconcerted, the way they’d shift withoutwarning from balsam to patchouli to something else, and back again. And Arista found it hard toget used to the way her skin felt perpetually stroked, as if any touch could send her over the edge.Then there were the songs. Arista spent evenings writing them down, her pen drifting beyond heracross the pages spread on her shiny kitchen table.n Whose gift was this? She wrote UPS. But her letter arced across the country and disappeared. Shetried the telephone. A recording said, press one, which she did, but no operator ever came on the line.Finally she decided on Chance. She said it out loud every morning Thank you, Chance, and every dawnfell fresh in love with the white clouds that came out of her mouth.24

Ala b a s t e rShe had northern skin and a heart curled to keep warm. One spring, traveling, she met an island manwho smelled of soft mud, like the bottom stems of marsh grass in receding tide.n He used to moan her name across the waters. In response, she’d gather tighter the small whitejealous shells she couldn’t give him, hold them like sharp babies to her chest.n One three o’clock they went downtown. He took her arm, and in the heat they passed from squareto square. Finally, they reached the river. Over the way loomed a dry-docked boat, a black freighter withmany decks and a foreign name. His index finger traced her skin from elbow to wrist. She shivered likethe worked boat’s hull. And suddenly she wanted to let the shells of possession fall, all the white fans ofthem in tiny clatters to the ground.n But outside Alabaster’s window the snow had flurried all night, all night. It lay heavy as burialagainst her door. Trapped inside, she picked up a shell and touched it to her tongue. She tasted salt, thesweet sex tang of fish. She put the shell away, closed the lid of her basket, and left him sitting there.26

The Compass Points of AWe s tShe works the A’s point against the seam that joins the pages. She throws the coverand binding threads away. She climbs the flights of the fire tower, one hand on therail, the other holding close the baby of her work. The steps are steel but slenderand as she ascends, the staircase sways, like a woman’s hips keeping time. The windturns sudden, huh, huh trying to separate her from her book, but she holds on. If shelooked down, she would see her crumpled roof, the continents of rust on her car’sblue top. If she looked across, she would see a faint thumb of smoke, where someoneis burning trash. But she is looking up.n At the last step, she lets the pages go. They arc, they sail, they waft, parthandkerchief, part genoa, part something she can’t yet describe. Then she turnsaside to watch the miles of trees for flame. When she finishes her shift, she climbsdown and picks up what she finds. She’s leaving her story to the air. It may end inthe middle now. It may never end. But it’s hers, and she holds it in her hands.31