Download this publication - Plantlife

Download this publication - Plantlife

Download this publication - Plantlife

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

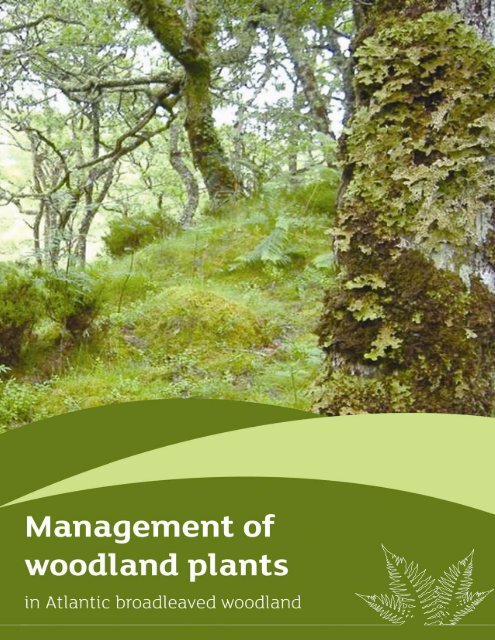

MANAGEMENT OF WOODLAND PLANTSIN ATLANTIC BROADLEAVED WOODLANDA CONSERVATION FRAMEWORKWritten by Richard Worrell and Deborah LongAcknowledgementsThe authors wish to thank: Sandy Coppins, Gordon Rothero, Richard Thompson (ForestEnterprise), Dave Genney (SNH), Lucy Sumsion, Peter Quelch and Carol Crawford for theiradvice and expert input. Thank you to Sue Nottingham for proofreading and Luke Morton fordesign.2

Contents1. Introduction 31.1 Aims 31.2 Need for improved management of plant communities 31.3 The Important Plant Area concept 32. Atlantic Woodland and its current management 62.1 Defining Atlantic Woodland 62.2 Current management of Atlantic Woodland72.3 Management for woodland flora 93. Guiding principles for woodland management 114. Landscape scale planning 145. Site (woodland) scale management 165.1 Assessing plant communities and drawing up management prescriptions 165.2 Management prescriptions 271. Planning issues 272. Grazing control 283. Manipulating the woodland canopy to improve conditions for flora284. Woodland shrubs and scrub 305. Deadwood 306. Control of invasive exotic plant species 317. Conversion of conifer to native woodland, including PAWS 328. Movement of woodland plants into species poor isolated woodland 325.3 Integration of management prescriptions 325.4 Monitoring 335.5 Support via Scottish Government grant schemes 343

1. Introduction1.1 AimsThis report describes a “conservation management framework” for Atlantic woodland basedon the Important Plant Area (IPA) concept (www.plantlife-ipa.org/reports.asp). Theframework is intended to deliver:1. Guidance on how to assess the conservation value of woodland flora.2. Outline management guidance for woodland flora at both local (site) and catchment(habitat network) scales.3. Means of assisting conservation planning by prioritising the locations where managementis required based on habitat network principles.The long term aim is to increase habitat and species resilience through improved habitatquality and the formation and expansion of habitat networks. The need for <strong>this</strong> work arisesbecause:• There is relatively little management guidance aimed specifically at woodland flora,compared with that available for trees, birds, mammals and some invertebrates.• There is a need to strengthen landscape scale and habitat network approaches inconservation management to augment current site based approaches.• There is a need for conservation organisations to be able to prioritise scarce resourcesin the face of effectively unlimited demands.The approach described here is designed to dovetail with other available guidance; notablythe Forestry Commission Forest Habitat Network approach (Moseley et al. 2005), theWoodland Grazing Toolkit (Sumsion and Pollock 2006), and the Peterken-Worrell managementmodels for Atlantic Oak woodlands (Peterken and Worrell 2005, Quelch 2005). It is intendedto be suitable for all organisations involved in woodland conservation and management.Atlantic woodland is one of six priority habitats under <strong>Plantlife</strong> Scotland’s “Back From theBrink” programme. This report will guide conservation activities undertaken by <strong>Plantlife</strong>Scotland within the West Coast IPA under <strong>Plantlife</strong> Scotland’s Back From the Brinkprogramme.1.2 Need for improved management of plant communitiesMost woodland plans, especially those without designated areas, have limited coverage ofwoodland flora and little or no consideration of management that might enhance plantcommunities (other than trees). Management specifically aimed at safeguarding andenhancing woodland plants in Scotland has started to be developed in the last five years(Coultard and Scott 2001, Coppins and Coppins 2005, Moseley et al 2005, Rothero 2005,Thompson 2005, Sumsion and Pollock 2006, Averis and Coppins 1998, Coppins et al. 2008).However, with a few notable exceptions (e.g. Averis and Coppins 1998, Thompson 2005),there is currently little guidance aimed at practitioners (owners, agents, surveyors) thatwould help in preparing the vegetation sections of woodland plans. This is clearly adeficiency as woodland plans are the main vehicle for delivering improved management andare the means by which owners can access government grants to support conservation work.4

1.3 The Important Plant Area conceptIn 2007, <strong>Plantlife</strong> launched a list of 150 Important Plant Areas (IPAs) across the UK (seewww.plantlife-ipa.org/reports.asp). IPAs are areas of great botanical importance forthreatened species, habitats and plant diversity; and their identification and managementmeets Target 5 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (<strong>Plantlife</strong>, Kew and JNCC 2002).In the UK, IPAs have been identified where there are exceptional sites holding rare anddiverse communities of flowering plants, bryophytes, lichens, stoneworts and algae. Areasqualify if they meet one or more of these internationally agreed criteria (Anderson 2002):1. They hold significant populations of one or more species that are of global orEuropean conservation concern.2. They have an exceptionally rich flora in a European context in relation to itsbiogeographic zone.3. They are an outstanding example of a habitat type of global or European plantconservation and botanical importance.IPAs can contain a wide range of habitats and species and they are rarely identified on thepresence of one type of plant or habitat. IPA boundaries are identified using a two stageprocess that maps:• “Core areas” of habitat where the qualifying features are present. These cancorrelate with designated sites (e.g. SSSIs), but also includes all other ecologicallysuitable areas. They may consist of a single area or several unconnected areascomprising a series of plant sites.• “Zones of opportunity”, into which, if the current land use is appropriate and correcthabitat management is carried out, the key species or habitats could expand. Theseare shown as a series of 1 km buffer zones around the core areas filtered using keypredictive environmental variables to identify areas with the greatest potential forexpansion.The IPA approach can be used for prioritising conservation work. Firstly sites within IPAs arelikely to be of higher priority than similar sites not in IPAs and the most important habitats inthe IPAs are identified. Secondly the most important locations and broad types ofconservation work required are identified during the IPA mapping process. Priorities forconservation work would usually follow the sequence:1. Improving the habitat condition of the core areas;2. Expanding core areas into the zones of opportunity to form larger more robust areas;3. Linking areas of habitat into larger networks usually by improving the habitat conditionof areas of ground between habitat patches (in both core areas and zones ofopportunity).Such work to improve habitat networks provides the potential for increasing resilience ofplant communities and habitats to a range of impacts, including the effects of climatechange.IPAs and Forest Habitat NetworksThe process of developing IPAs closely mirrors Forest Habitat Networks(www.forestresearch.gov.uk) meaning the two approaches are compatible. For example,initial analysis of the West Coast IPA has indicated that the Sunart area IPA for Atlantic5

woodland is similar to the Sunart Forest Habitat Network 1 (see figs 1 and 2). This is importantbecause many of the woodland managers involved with Atlantic woodlands will be familiarwith the Forest Habitat Network approach.Figure 1: West Coast Scotland IPA showing the core areas and zones of opportunity.1 Core Areas and Zones of Opportunity in IPAs are equivalent to “habitat“ and “restoration / conversion /expansion zones” of Forest Habitat Networks.6

Figure 2: IPA map for Loch Sunart area. Green areas are Zones of Opportunity, other coloursare different categories of Core Area.The West Coast Scotland IPAThe West Coast Scotland IPA is one of 42 IPAs identified in Scotland. It covers an area ofabout 800 km 2 stretching from Kinlochbervie in the north, to Tarbert in the south and GlenCoe in the east (http://www.plantlife-ipa.org/Factsheet.asp?sid=1116). Most sites within <strong>this</strong>area have been nominated for old sessile oak woodland and montane oceanic heath 2 , bothhabitats that are internationally rare. Some of the best Atlantic woodland sites for oceanicbryophytes and lichens in Europe occur here. It includes 47 core sites, nominated for the richdiversity of bryophytes, lichens and other plants, many of which are internationallyimportant. Subsidiary core sites are identified as ancient woodland with a high diversity oflichens and / or bryophytes and the presence of an indicator species, Plagiochila heterophylla(Fraser and Winterbottom 2008). The main threats to woodland sites are the spread ofRhododendron ponticum, over and under grazing and inappropriate woodland management.Core Areas and Zones of OpportunityFraser and Winterbottom (2008) identified 47 core sites, according to their rich bryologicaland lichenological diversity, with additional subsidiary core sites identified from a) the SNHAncient Woodland Inventory, b) specific sites identified by Averis (2001); and c) sites withPlagiochila heterophylla, an indicator species for Atlantic woodland. Details of the mappingprocedure are given in Fraser and Winterbottom (2008).2 Other habitats included are dune systems, Caledonian pinewoods, blanket bog and freshwater lochs.7

2. Atlantic woodland and its current management2.1 Defining Atlantic woodlandAtlantic woodland is woodland that occurs in highly oceanic climatic conditions close to theAtlantic Ocean. Various definitions have been put forward employing the terms Atlantic,oceanic and hyperoceanic to describe the climate, woodland and plant communities andusually focusing on:• Wetness i.e. high annual rainfall, high numbers of wet days, wetness during summerseason, low potential water deficit.• Little annual temperature variation and low incidence of frost and snow cover.For the purpose of <strong>this</strong> report all native woodland within the West Coast Scotland IPA is to beconsidered to be ‘Atlantic’ (see Figure 1).The botanical defining characteristics of Atlantic woodland centre on the rich bryophyte andlichen communities that are supported in these climatic conditions, that often showgradations with increasing oceanicity even within the Atlantic zone. As a result of theclimatic conditions and topography, Atlantic woodlands acquire other characteristics:- high wind speeds result in wind driven disturbance patterns and in coastal areas,dwarfing of trees including salt effects;- steep environmental gradients with proximity to coast and increasing elevation lead tostrong landscape-scale variation;- the soils show clear patterns of leaching and flushing according to topographic position,with corresponding variation in woodland and plant communities;- the often highly incised topography, including ravines and raised coastlines, leads tounusual habitats and habitat network patterns.At a global scale Atlantic woodlands are best considered as part of the coastal temperaterainforest biome, which has a very restricted global distribution (see Figure 3).Figure 3: Global locations of temperate rainforest biome (Weigand et al, 1992, see Worrell1996). There may also be small areas on the coasts of France, Spain and Portugal.8

Woodland communitiesAtlantic woodlands include the following woodland communities:• Oak-birch woodland W11 and W17.• Ash woodland W9: usually in small patches.• Alder and willow ‘wet’ woodlands - mainly W4 (downy birch) and W7 (alder).• Hazel woodland that do not fit well into the National Vegetation Classification (NVC).• Pine woodlands W18.Woodland conservation effort in recent decades has focused strongly on oak woodlandsbecause of their botanical importance for bryophytes and lichens, their greater extent andtheir dominance in designated sites. Ash and hazel woods have received less attention in thepast, though many ecologists would now rate them as at least as important as oak woods, notleast because they have a more natural composition and structure compared to many coppiceoak woodlands. Ancient hazel woods with long site occupancy have recently receivedconsiderable attention (Coppins et al. 2008). Alder and willow woods can have importantbryophyte and lichen elements. The extensive areas of recent W4 downy birch woodland areof more limited value at present, although they may provide valuable habitats in future.Some NVC pinewood sub-communities (notably W18d Sphagnum capillifolium/ quinquifariumand W18e Scapania gracilis) share aspects of the lower plant interest with Atlanticbroadleaved woodlands and have similar management needs. Guidance will focus on thefollowing plant communities: W11b Blechnum spicant sub-community, W17a Isotheciummyosuroides – Diplophyllum albicans subcommunity, and W9 ash woodlands and hazel scrub.Wet woodland and pine communities, which often occur in intimate mosaics with the mainoak-birch and ash woodlands, are included as associated woodland types.2.2 Current management of Atlantic woodlandCurrent woodland management as it influences woodland flora is best described in relation totwo main factors:• Management of tree cover: <strong>this</strong> covers interventions to alter the composition andstructure of the canopy which can influence woodland flora and spans a range from‘no management’ (neglect) through ‘minimum intervention’ to ‘conservationmanagement’ and ‘multi-purpose management’.• Management of grazing: <strong>this</strong> covers grazing by both wild deer and domestic stock; andspans the range from no control (high grazing pressure), to controlled grazing (byfence and/or deer culling or via woodland grazing plans), to zero grazing in fencedplots.These two factors are encountered in a surprising number of permutations to give the mainmanagement scenarios:1. No woodland management: no woodland management or restricted to opportunisticremoval of small quantities of firewood.a) Unenclosed grazed woodland: woodland (and wood pasture) used as grazing andshelter for farm stock and/or deer. Where densities of farm stock are high (especiallysheep) <strong>this</strong> is usually unfavourable for most plant communities, though it can beacceptable in the short term for epiphytes. At lower grazing densities and/orseasonal grazing, it can be favourable for some bryophytes and many lichens.9

) Woodland enclosed by stock fences but with no deer control: woodland (and woodpasture) often regarded primarily as deer shelter. Woodland is often moderatelyfavourable for ground flora and favourable in areas which are difficult for deer toaccess (ravines etc); often favourable for epiphytes and bryophytes on boulders.c) Total exclusion of grazing: <strong>this</strong> happens temporarily over small areas whenbroadleaved woodland is deer-fenced for other purposes, usually fences erected forcommercial forestry. This can give rise to young regenerating broadleaved woodland,which can be temporarily detrimental to lower plant communities. Absence ofbrowsing can be favourable for woodland plants for a year or two, but rapidlybecomes unfavourable. However, deer populations usually penetrate these areasafter a few years and they revert to type 1b above, although shading in highly stockedyoung stands can be detrimental to lichens.2. Conservation management: <strong>this</strong> occurs as a) minimum intervention restricted to deercontrol and removal of exotic species and b) active conservation management which involvesimproving the composition and structure of the woodland in addition to deer control andremoval of exotics. Work directed at diversifying the canopy, encouraging native shrubs andincreasing deadwood is generally beneficial for all plant groups provided it is done sensitivelyand no trees with rare epiphytes are removed in thinnings. Both management approaches areencountered on woodland nature reserves and increasingly in private and Forestry Commissionwoodlands.a) Without deer control: scattered tree and shrub regeneration might be protected byguards. Generally moderately favourable for woodland flora and favourable in areaswhich are difficult for deer to access (ravines etc).b) With deer culling under deer management plan: with deer control at a levelintended to allow recruitment of tree regeneration in gaps and at woodland edges.Generally favourable for woodland flora as browsing is never wholly eliminated, butcan be detrimental to those bryophytes requiring heavier grazing / browsing, orwhere canopy gaps critical for lichens become infilled by tree shrub regeneration.c) With controlled grazing: controlled grazing under a woodland grazing plan intendedto improve woodland flora. Potentially a highly favourable management regime,currently only implemented over small areas in woods traditionally grazed by cattle(under FC stewardship grants).d) Deer control primarily by fencing: typical of ‘regeneration areas’ in nativewoodlands. Allows recovery of regenerating trees and shrubs. Total exclusion ofgrazing instituted to encourage regeneration of trees and shrubs eventually becomesdamaging for many ground flora species, although tall herb communities can prosperon some sites.3. Multipurpose woodland management: <strong>this</strong> usually involves management aimed at smallscale timber extraction by thinning and group felling, with or without deer control, and oftenincludes elements of conservation management. On an appropriate site, at a sensible scaleand done with care, timber management is typically neutral or only slightly/temporarilydamaging for some woodland plants and over the long term can be compatible withconservation of plants. If carried out on important plant sites and done without regard to theflora of the site, <strong>this</strong> can be damaging, especially for lower plants.Recent history of managementPrior to about 1990, the management of the majority of woodlands could have been10

characterised as ‘neglect’ i.e. they were unmanaged woodland on estates and farms 3 , simplyused as pasture and shelter for deer and farm stock, with occasional local cutting forfirewood. There was a scatter of well-known instances of minimum interventionmanagement, mainly on oak woodland national nature reserves (e.g. Ariundle in Sunart, GlenNant near Taynuilt and Taynish, near Crinan). Parts of these areas were subject to smallgroup fellings to attempt to initiate a new age class of trees, though <strong>this</strong> rarely had theintended effect. Oakwood SSSIs increasingly had SSSI plans, which were either implementedor not, according to the wishes of owners. A few woods were managed sporadically fortimber, although <strong>this</strong> mainly took the form of opportunistic felling of more valuable trees.Starting in the early1990’s, renewed interest in native woodland had the effect ofencouraging management of oak woods, often promoted by native woodland initiatives withsupport from Forestry Commission and Scottish Natural Heritage (e.g.www.sunartoakwood.org.uk). This encompassed a range of approaches from minimumintervention, to active conservation management aimed at restructuring and promotingregeneration, through to multiple benefit management with an emphasis on small scaletimber harvesting. Fencing aimed at total exclusion of grazing and browsing was commonpractice. At the same time there was an increasing appreciation of the botanical and culturalvalue of grazed wood pastures and veteran trees, especially in western Scotland. Starting in2003, these approaches were augmented by initiatives to encourage controlled woodlandgrazing of livestock initiated by farm woodland interests (Sumsion and Pollock 2006).The main manifestations of these factors have been:• A significant increase in the area of woodland enclosed by either stock or deer fencingand increased culling of deer within large fenced enclosures (Ratcliffe and Staines2005).• Some attempts to diversify oak monocultures by group felling aimed at initiating oakregeneration. Dense birch regeneration with rowan and some oak regrowth has beenthe usual outcome.• Attempts to harvest small quantities of oak timber to supply mobile sawmills.• A series of trials of controlled grazing by domestic stock supported by S9 Stewardshipgrants under the former Scottish Forestry Grant Scheme.• Ongoing restoration in some significant areas of PAWS plus a few small areas ofRhododendron clearance.• Until recently, an increasing number of woods being the subject of management plans.Many of these have now expired with no grants schemes in place to continue them.• Very recently, signs of an increase in firewood extraction and the installation of minihydro schemes. Both have the potential to impact negatively on lower plantcommunities in high botanical value woodland.2.3 Management for woodland floraEfforts to introduce management aimed specifically at woodland flora have begun. Thesehave generally been limited to:• Botanical and site condition monitoring surveys of important sites, that have mainly fedinto management plans for designated areas.• Awareness raising, involving a limited number of owners and agencies, but latterly morewidely via targeted <strong>publication</strong>s and events.3 The vast majority of Atlantic oakwoods are on privately owned land.11

• Control of grazing: the traditional reliance on permanent fencing is being replaced bylimited efforts to institute temporary fencing, deer culling under deer managementplans and controlled grazing using the Woodland Grazing Toolkit.• Removal of exotics especially Rhododendron ponticum, with site-based projects beingreplaced by a more strategic approach.Management guidance for plantsManagement guidance specifically aimed at safeguarding and enhancing plants in Atlanticwoodland has been developed in the last five years (e.g. Coppins and Coppins 2005, Rothero2005. Thompson et al. 2005). The Atlantic Oakwood Symposium in 2004 led to the productionof papers providing management principles for bryophytes and lichens, with particularreference to Atlantic oak (summarised in table 1). This has been followed by the <strong>publication</strong>of a new series of identification guides by <strong>Plantlife</strong> Scotland describing the key commonlichens (Acton and Griffiths 2008) and bryophytes (Rothero 2010) of Atlantic woodlands andproviding a means for non-experts to engage with the identification of important species.Management guidelines for fungi in Atlantic woodland are limited to general guidance ondeadwood (Watling 2005) and on hazel gloves fungus (Coppins et al 2007).Recent woodland management guidance seeks to integrate conservation management withwider economic and social objectives, giving prescriptions which are widely applicable andfairly pragmatic (Peterken and Worrell 2005, Thompson 2005, Quelch 2005). Peterken andWorrell developed 5 “management models” (long rotation high forest, standard rotation highforest, minimum intervention, wood pasture, coppice) to help steer woodland management inthe Sunart Oakwoods. These give owners a range of options and if all models are representedwithin a catchment, would safeguard conservation interests whilst allowing some productiveuse. In addition, progress has been made in landscape scale management using the ForestHabitat Network approach (Moseley et al. 2005), the output of which is generally sound forwoodland flora provided low dispersal distances are used. Responding to the need to thinoakwoods, Thompson et al. (2005) produced innovative guidance on how to select trees forthinning using a process that includes assessment of the value of epiphytic bryophytes andlichens on individual trees and boulders.Collectively, current guidance adopts the following general positions:• That current bryophyte and lichen interest of oakwoods is high and needs to beprotected from unwise management intervention and invading exotics (Coppins andCoppins 2005, Rothero 2005, Long and Williams 2008).• Management to increase the structural and tree species diversity of woods, if donecarefully, can be compatible with conservation of bryophytes and lichens (Peterken andWorrell 2005, Thompson 2005, Quelch 2005).• Careful management of the woodland canopy can increase bryophyte and lichendiversity especially in the longer term e.g. by producing a new generation of veterantrees, enhancing species diversity and increasing deadwood (Thompson 2005, Coppins andCoppins 2005).• Conditions for woodland plants can be improved by controlling grazing (Sumsion andPollock 2006).• Coppicing of ancient hazelwoods can be highly detrimental for epiphytes (SNH 2008).• Conditions for some species groups, especially lichens can be improved by diversifyingthe structure and composition of woods.• Translocations of ‘missing’ plant species may be beneficial for common woodlandspecies in some limited circumstances (Coulthard and Scott 2001).12

Table 1: an overview of the main habitat requirements, threats and managementrecommendations for different plant groups (based on Rothero 2005 and Coppins andCoppins 2005)HabitatrequirementsMain threatsFavourable, or at leastneutral, managementpracticesWoodlandherbs, smallshrubs andferns• Variety oflight levelsaccord-ing tospecies• Intermediategrazing levels• Appropriatetree andshrub speciesin the canopyaccording tosite• Invasion byRhododendronponticum & beech• Over grazing• Zero grazing• Perpetuation ofoak canopy on ashwoodland sites• Controlled grazing• Removal of Rhododendronponticum and beech• Minimum interventionmanagement• Thinning and small groupfellings in uniformwoodland canopyBryophytesandepiphyticferns• Suitablesubstrates:rocks & trees• Constant highhumidity• Old veterantrees• Deadwood• Clearfelling• Felling of highbiodiversity trees,• Felling/thinning onsoutherly aspects• Felling thinningnear key gorgesites• Timber extractionthat reduces deadwood• Invasion byRhododendronponticum & beech• Excessive shadingby exotic trees/shrubs• Over grazing• Zero grazing• Disruption ofboulders & rockoutcropsby creationof extractionroutes and forestroads• Controlled grazing• Removal of Rhododendronponticum & beech• Minimum interventionmanagement.• Buffer strips alongwatercourses and ravinesand near high biodiversitysites• Careful thinning based onbryophyte biodiversity ofindividual trees• Removal of infilled saplingsaround old open growntree• Favouring large treesduring thinning which canbecome future veterans• Avoiding chemical controlof bracken on highbiodiversity sites13

Lichens• Suitablesubstrates• High humidity• Variety oflight levels –mainly semishade• Variety oftree andshrub species• Old, veterantrees• Presence ofdeadwood• Intermediategrazing levels• Clearfelling• Felling of highbiodiversity trees• veteran trees• Felling whichreduces deadwood• Coppicing ofhazelwoods• Invasion byRhododendron &beech• Over grazing• Zero grazing• Controlled grazing• Removal of Rhododendronponticum & beech• Maintain full range of treesizes• Variable stocking andirregular thinning.• Small group fellings inuniform woodland canopy• Removal of infilled saplingsaround old open growntrees• No gap infilling withplanted trees• Prevention of developmentof dense understorey14

3. Guiding principles for woodland managementWoodland dynamics and long term management: woodlands inevitably change and developslowly through time in long cycles, with only some stages (mainly with mature / over-maturetrees) being optimal for many specialist plant species. However, all the phases of woodlandsuccession are inevitable over a long time period and the different plant species have theirown strategies for dealing with them. Therefore, the wide variety of woodland structuresand compositions which comprise the natural successional stages are potentially acceptableexpressions of ‘favourable’ habitat conditions. Sometimes short term losses of plant diversitymay occur, followed by gains in the longer term; for example, <strong>this</strong> could happen when a woodis thinned in order to promote a new generation of older, large trees. The benefits orimpacts of different management options can only be assessed using timeframes measured indecades or longer.Landscape scale: the ecological quality of woodland for plants needs to be assessed onwhole woodland or catchment scale (10-100ha or more), as well as at stand scale. An oakbirchwoodland which is 99% birch may look non-optimal, but if the rest of the woods in thecatchment turn out to be oak monocultures, it suddenly becomes desirable as an element ofdiversity. Similarly management options can only be judged at these larger scales. It isusually desirable to manage to achieve a variety of age classes and woodland structures atcatchment scale but makes no sense to attempt to represent these in individual woods (as hasmisguidedly been attempted in places during recent decades). The overall pattern to strivetowards is a dynamic patchwork of different woodland conditions with the various stagesslowly shifting their locations through time.Analyses at landscape scales via the IPA or Forest Habitat Network (FHN) models can be usedto make informed decisions as to how best to optimise the development of high qualityhabitat patches into larger networks. The formation of networks aids dispersal of species andcreates larger more resilient populations. This approach can work at all scales from habitatpatches within individual woodlands, to woodlands within a catchment. This approach isthought to work well for plants even though many woodland plant populations appear to beable to survive in small habitat patches and have relatively poor dispersal capabilities.Natural v. artificial: it has widely been assumed that ‘natural’ compositions and structures,together with the processes that gave rise to them, are always desirable. Whilst <strong>this</strong> is still asafe assumption in many cases (especially in closed canopy woodland), some artificialconditions arising from past management are also valuable and worth perpetuating. Indeedthe distinction between natural and artificial is often sufficiently hard to define in theory andobserve in the field, and can become a distraction rather than a useful tool. This can beillustrated by wood pastures; they are clearly highly valuable ecologically, but have manyartificial aspects 4 . They may have had ‘natural’ counterparts in the distant past but theirstatus in historic and prehistoric times can currently only be guessed at. The ‘filling in’ of oldwood pasture by natural regeneration to form closed canopy woodland is a natural processleading to what most people would regard as a more natural structure, yet it is usuallyecologically undesirable. Artificial aspects of woodlands need to be assessed for their ownecological value and only changed if there are clear biodiversity (or other) benefits, rather4 The setting of the boundaries of woodland SSSIs and SACs illustrates the potential pitfalls. Designated areas usuallyinclude only the closed canopy woodland, most of which had been intensively managed for timber in the past andexcluded many far more valuable areas of habitat in adjacent old wood pastures.15

than being changed simply because they do not conform to our current view of what might benatural.Disturbance: disturbance is a natural process leading to cyclical changes in woods and withdifferent plants losing and gaining as a result of disturbance episodes. The assumption shouldnot automatically be made that disturbance is bad and will damage plants; <strong>this</strong> will be true ofsome species, but others actually require periodic disturbance. It is useful to try to form apicture of the disturbance regimes in different parts of woods and how different plants copewith them. Management interventions aimed at introducing greater diversity into woodland(and/or harvesting timber) often share some attributes with natural disturbance. Knowledgeabout how plants cope with natural disturbance allows you to assess the effects of thesemanagement operations. Disturbance regimes in Atlantic woodland tend to be dominated bysmall scale events causing death of individual trees and small groups due to wind (distributionof events influenced by poor rooting in waterlogged or shallow soils and by occurrence ofdisease), overturning of trees in ravines and other steep side slopes (due to leaning growthhabit and poor rooting), disease especially in birch and ash, flood and landslip besidewatercourses and occasionally drought. Large scale wind disturbance events occur, but thegreater frequency of damaging winds in Atlantic woodlands may be offset by trees being tosome extent adapted by constant exposure to high winds. Furthermore oak is relativelyresistant to wind damage, although birch is not. The role of ‘phoenix’ regeneration increating habitat for epiphytes has been noted in the field (Coppins pers. comm.) and mayhave been under estimated to date: <strong>this</strong> occurs where significant wind-blow ‘events’ causemature oak trees to be blown over, which then put up regenerative growth. Fire sufficient tocause tree death is very rare, although out of control muirburn is very damaging. Refugeswith long periods between disturbance events exist in old woodland in very sheltered siteswith good soils (such as some types of ravine), whereas disturbance cycles elsewhere areprobably shorter. All <strong>this</strong> suggests that woodland ground flora is very well adapted to smallscale disturbance events at time scales ranging between short (e.g. in birch or wooded ravinesides) to quite long (many oakwoods).Trade-offs: different plant species have different habitat requirements and so responddifferently to management interventions. For example, conditions for lichens may improvefollowing careful opening of the canopy whereas <strong>this</strong> may not be the case for bryophytes.There will always be difficult trade-off to make, at all scales from choosing individual trees ina thinning operation (see Thompson 2005), through to choosing management options forindividual woods at catchment scale.Personal attitudes to timeframes and intervention: some managers prefer to rely on naturalmechanisms to effect change, which typically act slowly and have relatively uncertain,although naturalistic outcomes. Others prefer to do use more interventionist managementtechniques, which produce faster and usually (but not always) more certain outcomes. Thereis frequently no way of resolving which approach is best; it is a matter of personal preferenceand the unique combinations of factors at each site. Professional attitudes ebb and flowsomewhat, and recent decades have seen a preference for less interventionist approaches ingeneral (e.g. fencing is now seen as problematic), but a greater acceptance of well thoughtout management intervention where benefits are proven (e.g. the thinning of Atlanticoakwoods reported by Thompson et al 2005 and controlled grazing).Few right answers: there are two management options that are universally viewed aspositive: these are the removal of rhododendron and the institution of appropriate grazing.16

However beyond these, there are few wholly right answers in determining the management ofindividual woods. Managers need to be able to make a clear case for their chosenmanagement interventions (or the lack of them) and to be able to justify them in the face ofapparently equally viable alternatives.4. Landscape scale planning for woodlandsThis involves analysing the distribution and conservation value of woodlands in order todetermine how they contribute to habitat networks and how networks can be improved. Thisallows the most important areas of woodland for conservation work to be identified. This isuseful mainly for organisations involved in the setting of priorities at regional scale.Landscape scale planning for woodlands can be done as an Important Plant Area exercise (seesection 1.3), or, to give greater detail, as a forest habitat network project (Moseley et al.2005, 2007). In both cases the aims will be to classify the current woodland habitat accordingto its conservation value and then determine, in <strong>this</strong> case:1. Areas/networks of native woodland of high conservation value which can act as corehabitat from which species might be able colonise adjacent lower quality woodland.2. Areas of lower native value woodland which can contribute to networks by beingrestored to higher value woodland.3. Plantation conifers, some of which might be best converted to native woodland.4. Which areas of woodland can most usefully be expanded in order to improve networks.This involves developing fewer larger networks in a catchment to replace smallerscattered ones. It also requires determining the conservation value of the open landthat new woodland might be established on (so as to avoid impacting on valuable openground habitats).The order of priority for conservation work that emerges from IPA and FHN analyses willgenerally be as follows:• Priority 1: Protect and improve habitat condition of native woodland in core areas(FHN= Core Habitat). Focus first on areas of highest quality woodland.• Priority 2: Improve habitat condition of woodland in zone of opportunity (= FHNrestoration and conversion zones) starting with areas adjacent to areas of corehabitat. This will involve work to improve the conservation status of native woodland (=FHN restoration zone) or convert plantation conifers to native woodland (= FHNconservation zone).• Priority 3: Expand native woodland in core area into adjacent non-wooded area inthe zone of opportunity (= FHN expansion zones) if appropriate and feasible. This isbest done in a way that expands the highest quality woodland and/or creates thelargest networks and has least impact on any valuable open ground habitats.The West Coast IPA analysis will be available at www.plantlife-ipa.org when complete. Detailsof how to carry out FHN analyses are given in Moseley et al. 2005 and 2007. FHN mapsgenerated using low dispersal distances 5 (of perhaps 100-200 m) are most appropriate, as5 Forest Habitat Network maps use specific dispersal distances (from a few hundred metres toseveral km) to illustrate how woodland blocks are effectively connected into networks for17

woodland plants are assumed to have low dispersal capabilities (Long and Williams 2008). Themanagement techniques most appropriate for implementing these priorities are described insection 5.2.Using GIS mapping to assess conservation value at landscape scaleGIS mapping of woodland can make a good start on identifying areas of high quality woodlandby focusing on designated areas and ancient semi-natural woodland. However, the databasesused have some problems associated with them. As a result, maps can be broad brush andcontain substantial local inaccuracies, notably missing many smaller woods of highconservation value (e.g. ravine woodlands) and highlighting areas of ancient semi-naturalwoodland of only moderate value due to past history of intensive coppice management. Initialmaps built from publicly available data should ideally be supplemented and tested againstmore detailed records and reports from species experts. These include reports commissionedby SNH, National Trust for Scotland and Scottish Wildlife Trust for example and rare andthreatened species databases held by the specialist societies and often available atwww.nbn.org.uk. All lichen surveys commissioned by SNH and others in Scotland are listed athttp://spreadsheets.google.com/ccc?key=0AshyEG2UDWgycF9YRDlrbl81NGJKTElhVkpFT3FOR1E&hl=en_GB. <strong>Plantlife</strong> is completing <strong>this</strong> process through IPA mapping, which will be availableonce complete at www.plantlife-ipa.org. Such maps are, however, only suitable for strategicplanning and not for making management decisions for individual sites.Using GIS to assess the conservation value of open ground adjacent to woodlands, that mightbe suitable for woodland expansion, is also extremely difficult. It is possible to get someindication from GIS layers describing broad vegetation types (especially for mires/peatlands)and landuse categories. However, ultimately, it is always necessary to carry out a groundsurvey.Using Peterken / Worrell management models for oakwoodsOne of the aims of the Peterken/Worrell management (stewardship) models was to try toensure that full the range of different woodland management models were represented inindividual catchments / regions. This involves assigning woodland blocks (i.e. groups ofindividual woods) or individual woodlands to Peterken/Worrell management (stewardship)models (Peterken and Worrell 2005; Quelch 2005). Information on broad managementprescriptions for the different models are available that can be used to develop woodlandplans (Quelch 2005). The five models (according to Quelch’s titles) are:• Natural Reserves (minimum intervention 6 )• Ancient Oak Forest (long-rotation high forest)• Native Timber Stands (standard rotation high forest)• Coppice• Wood pastureThis is particularly useful for ownerships interested in management that includes an elementof timber production, as the models attempt to balance conservation with productive use.species with different dispersal capabilities.6 Peterken Worrell titles in brackets18

5. Site (woodland) scale managementThis section sets out the how managers and owners can:• Assess the (botanical) conservation value of individual woods or parts of woods.• Identify problems affecting plant communities.• Draw up prescriptions to address the problems that can be entered into a woodlandplan, woodland grazing plan or SSSI or LBAP plan.At <strong>this</strong> stage it is assumed that it is useful to know how to improve the conservation value ofall areas of woodland, irrespective of their current conservation value and scope forimprovement. Once the conservation status (botanical value, woodland condition,management needs) of a woodland or group of woodlands has been assessed, it becomespossible to prioritise those areas most deserving of attention.5.1 Assessing woodland and drawing up management prescriptionsThe process of determining the best management prescriptions starts by assessing thebotanical value of the site, then moves on to consider the woodland condition and ends bydetermining the management needs. The stages involved in <strong>this</strong> are summarised in figures 4and 5 below.Step 1 Assess the value of the flora (botanical value)The aim is to distinguish areas with high botanical value from more ordinary areas of Atlanticwoodland. Areas with high botanical value are distinguished by:• Areas with diverse and complete plant communities, including the presence ofcharacteristic or rare species or communities, especially lichens and bryophytes.• Presence of ancient woodland with ancient woodland indicator species.• Favourable topography (ravines, watercourses) and microtopography (rocks, boulders,crags).• Favourable gazing levels.• Low levels (usually but not always) of past management.The first step in surveying woodland is often to do an initial rough survey – which might beno more than a fairly rapid walk around the wood. This allows you to do a quick assessmentof the flora and woodland condition and to roughly divide the wood into provisionalmanagement units according to topography, woodland type, condition and immediatelyapparent management needs. These management units should have broadly similar woodlandcharacteristics and management needs. Their boundaries can be adjusted as survey of thewood progresses.Following the simple guidance given here helps woodland managers to assess the botanicalinterests of the site, without detailed knowledge of bryophytes and lichens. Hopefully, <strong>this</strong>process will also enhance appreciation and enjoyment of the wide botanical diversity ofAtlantic woodland sites.19

Figure 4: outline of process for determining management prescriptions for woodland flora.1. ASSESS WOODLAND FLORA(BOTANICAL VALUE)Draw up plant lists and determine NationalVegetation Classification woodland type.Identify areas of the wood of high botanical valuefocusing on lichens and bryophytes.2. IDENTIFY ANY PRIORITY SPECIES ORCOMMUNITIESDetermine whether there are plant species /communities that should be afforded particularpriority. These will usually be bryophytes and/orlichens.3. ASSESS CONDITION OF THE WOODDescribe / assess the features of the woodlandthat have a bearing on plant communities – bothpositive and negative (grazing, woodlandcomposition, woodland structure, regenerationetc).4. WHAT ARE THE KEY PROBLEMS ANDCONSERVATION MANAGEMENTPRESCRIPTIONS?Determine conservation problems andmanagement prescriptions that address these.OTHER MANAGEMENT PRESCRIPTIONSConsider the effects of managementprescriptions for other objectives (productiveuse, recreation, grazing) on vegetation.Amend as necessary.5. IMPACTS OF PROPOSED CONSERVATIONMANAGEMENTConsider any impacts of proposed managementprescriptions on other aspects of conservation valueand wider management objectives (productive use,recreation, grazing). Amend if necessary. Tradeoffswill be necessary.6. WOODLAND PLANEnter prescriptions into a woodland plan,woodland grazing plan or SSSI plan.20

The next step is to carry out a full survey, during which plant species lists are drawn up. Theaim of <strong>this</strong> is to divide the site into areas with similar vegetation according to:1. Woodland NVC community: to help provide an overview of (mainly) vascular plants and toguide general woodland conservation management;2. Botanical value: to identify areas with high quality plant communities, focussing mainly onlichens and bryophytes.Most woodland or ecological surveyors will be able to draw up a satisfactory list of vascularplants and assign sites to a woodland NVC type. However some surveyors will have difficultywith lichens and bryophytes; and unfortunately there are currently only a small (butincreasing) number of surveyors with a good knowledge of these lower plants who might becalled upon to help. To overcome <strong>this</strong>, a method of assessing the botanical value of sites isprovided below which requires little or no prior ability to identify lichens and bryophytes.The approach uses 2 levels of assessment:• <strong>Plantlife</strong> Level 1 Assessment of Botanical Value: <strong>this</strong> requires no identification oflichen and bryophyte species, but presence of habitats suitable for important lichensand bryophytes are inferred from canopy and topographic features. This is thought tobe sufficient to flag up areas of potential higher botanical value. These would ideallythen be assessed using the Level 2 (below) to verify the existence of the most obviouslichens and bryophytes.• <strong>Plantlife</strong> Level 2 Assessment of Botanical Value: <strong>this</strong> requires identification of a smallnumber of lichens and bryophytes using <strong>Plantlife</strong> identification leaflets (Acton andGriffith 2008; Rothero 2010). Most woodland /ecological surveyors willing to invest alittle time in identifying characteristic lichens and bryophytes will be able to use <strong>this</strong>method.In addition a list of characteristic plant species (vascular, bryophyte, lichens) is shown inAppendix 1 that can be used to add detail to areas identified as high botanical value.Presence of the species in these lists is further confirmation of the status of sites as highbotanical value sites.Expert surveysSome owners and agents will be in a position to engage expert plant surveyors who will beable identify plants in all species groups and give a detailed picture of the value of sites.Guidance on assessments at <strong>this</strong> expert level is available (e.g. Coppins and Coppins 2002).Contact <strong>Plantlife</strong> Scotland or the Lower Plant and Fungi Advisor at Scottish Natural Heritagefor a list of reputable expert consultants, who are able to conduct surveys to the higheststandard.21

Figure 5: evaluation of botanical valueINITIAL SURVEY: Familiarise yourself withthe wood and its vegetation. Divide it intoprovisional management units according totopography, woodland type andmanagement needs etc.VEGETATION SURVEY: Make species lists forvascular plants and as many lichens orbryophytes as you easily can. Divide the siteinto areas with similar vegetation. Assign anNVC type to each provisional managementunit.BOTANICAL VALUE ASSESSMENT LEVEL 1REQUIRES NO IDENTIFICATION OF LOWER PLANTSUse the <strong>Plantlife</strong> Level 1 Assessment to identify areas of woodland thatare potentially of high botanical value, focusing on bryophytes andlichens.BOTANICAL VALUE ASSESSMENT LEVEL 2REQUIRES IDENTIFICATION OF A FEW KEY LOWER PLANTSUse the <strong>Plantlife</strong> Level 2 Assessment to identify areas of woodland thatare of high botanical, focusing on bryophytes and lichens.Produce vegetation map showing NVCand areas of high botanical value.22

<strong>Plantlife</strong> Level 1 Assessment of Botanical Value:Woodland areas are scored for the attributes shown in Box 1 by ticking the box in each rowthat best describes the site. The site (or part of a site) is then ascribed to a category ofbotanical value by looking at the weighting of the 6 ticks (low, medium, high). This approachgives a very basic assessment of sites and is suitable for use by all woodland surveyors.Box 1DescriptionAttributeCanopycoverTree speciesOld treesPresence ofrocks andbouldersLow canopycover ofsmall/youngtrees/shrubsMainly downybirch and/oralderSmall/youngrecentlyestablishedtreesNo bouldersor crags,even terrainHigh canopycover ofsmall/youngor mid-agetreesOlder trees,but still withmost treeshaving silvery,rather thanfissured, barkScattered,small bouldersor crags oneven slopeRavines No ravines Minorwatercourseswith graduallyshelving sidesGreen /brownepiphytecover ontree bolesand rockslooking likethesepicturesBOTANICALVALUESee Image 1belowSee Image 2belowHigh canopycover (70-90%) of oldertrees andshrubsMainly oakOlder/biggertrees, withfrequenttrees withfissured barkFrequentlargerboulders andcrags onuneven slopeDeep gully,but nowaterfall orcragsSee Image 3belowLow canopycover ofveteran trees /shrubs or oldwoodland/hazel scrubwith frequentgladesMainly elm,ash, hazelOld / big treeswith fissuredbarkLarge blockyboulders andcrags; hard towalk acrossDeep ravinewith waterfallsand cragsSee Image 4belowLOW MEDIUM HIGH23

Image 1:Image 2:24

Image 3:Image 425

<strong>Plantlife</strong> Level 2 Assessment of Botanical Value:Woodland areas are scored for the attributes shown in Box 2 by ticking the box in each rowthat best describes the site. The site (or part of a site) is then ascribed to a category ofbotanical value by looking at the weighting of the ticks (low, medium, high). Surveyors whoneed help in identifying lichens and bryophytes should use leaflets available from <strong>Plantlife</strong>Scotland (Acton and Griffith 2008, Rothero 2010). This approach gives a simple but fairlyeffective assessment of sites and is suitable for use by all woodland/ecological surveyors. Allthe species mentioned here can be found in the <strong>Plantlife</strong> guides (Acton & Griffith 2008,Rothero 2010). Additional species that indicate habitat quality will be present, but for thepurposes of <strong>this</strong> exercise, it is sufficient to use the lichens shown in the guides.Box 2DescriptionBryophytesPlagiochilaspinulosa group(<strong>Plantlife</strong> guide)Not presentLow abundanceand restricted tounusual featuresScapania gracilis Not present Low abundanceand restricted tounusual featuresHymenophyllumwilsonii (anhonorarybryophyte in <strong>this</strong>context)LichensLobarion andSticta species in<strong>Plantlife</strong> guideon ash, hazel,willow, rowanand old oakNot presentNot presentCrustose lichens Not present -hazel oftencovered incommonmossesSpecies in<strong>Plantlife</strong> guideon birch, alder,oakDominated bycommonspecies e.g.Parmeliasaxatilis,Platismatiaglauca,EverniaprunastriLow abundanceand restricted tounusual featuresLow abundanceand restricted tofew featuresModerateabundance onyounger smallerstems with onlya few speciesAny of thefollowing speciesin low abundanceandrestricted to fewfeatures:Menegazziaterebrata,Parmotremacrinitum,Hypotrachynataylorensis26High abundance over widerange of featuresHigh abundance over widerange of featuresHigh abundance over widerange of featuresHigh abundance over widerange of featuresFrequent crustose lichenson hazel and other species(e.g. rowan and holly) witha variety of speciesFrequent presence of anyof the following on treesand rocks: Menegazziaterebrata, Parmotremacrinitum, Hypotrachynataylorensis

Vascular speciesDryopterisaemulaBOTANICALVALUEStronglydominated bywavy hairgrass andtufted hairgrassHerbs restrictedto morecommonwoodlandspecies i.e.primrose,honeysuckle,stitchwort, woodsage, commoncow-wheatNil Occasional AbundantLOW MEDIUM HIGHFrequent dogs mercury orsanicleThe output of <strong>this</strong> stage should be a vegetation map showing the NVC communities andindicating the botanical value of the sites (see Figure 6). Individual species and habitats ofnote can be shown on maps as labelled arrows.Figure 6: a hypothetical example of a site vegetation map, showing NVC communities and thebotanical value of the site27

Step 2 Determine priority plant species/communitiesOn sites of high botanical value, determine whether there are priority plant species orcommunities that management will need to focus on, usually bryophytes or lichens. Thisdecision can be based on the presence of species marked in red on the species lists inappendix 1, plus other rare or notable species recorded in the survey. When considering thecondition of the woodland and drawing up management prescriptions (step 3 below), bear inmind the habitat requirements of these priority species.Step 3 Assess woodland condition.Assess the condition of the wood by gathering information on the features of the wood thathave a bearing on the plant communities (see table 2). These features can be split between:• Inherent features of the woodland e.g. its topographic features, ancientness etc.• Features influenced by management e.g. age classes, canopy composition etc.Lists should be drawn up of the features which contribute to or detract from the condition ofthe woodland. These lists can be entered into a management plan in the sections thatdescribe the conservation value and condition of the woodland.28

Table 2: checklist of features influencing woodland conditionHeadingRepresentation of woodlandtypes in landscapePositive features1. Inherent features of woodland• Ash woodland• Hazel woodland/scrub esp. where oldand with long site occupancy• Oak woodland where <strong>this</strong> is scarce incatchment• Riparian woodland• High elevation woodland• Wood pastureNegative featuresSite antiquity / continuity • Ancient semi-natural woodland on ASNWinventory• Ancientness apparent from plantcommunities (indicator species inCrawford 2009) – although vascularplant indicators are somewhat lessreliable in Atlantic woodlandsHabitat network • Woodland part of large patch / network/ corridor• Areas of ‘deep woodland’ conditions• Valuable woodland edge areas (esp. iffocus is on lichens)• Recent origin or planted woodland• Wood not in network, isolated byground that might be better carryingwoodlandPlant habitat • Ravines• Watercourses, waterfalls with splashzones• Flushes• Glades• Boulders, crags• Deadwood (see below)29

2. Features determined by past managementCanopy composition • Diverse canopy with representation ofash, elm, birch, bird cherry, goatwillow, silver birch, aspen, hazel.• Oak or ash trees gaining representationin secondary birch woodland• Tree canopy species reflecting NVCcommunities and underlying soil typesCanopy structure • Representation of different age/sizeclasses; presence of young or very oldtrees• Signs of natural disturbance due towind, disease, drought, landslip etc• Presence of canopy gaps / gladesShrubs • Presence of hazel, holly, blackthorn,hawthorn, willows, guelder rose, elder.Tree and shrub regeneration • Presence of seedling /sapling shrubs andtrees in field layer where <strong>this</strong> isdesirable, eg to expand existingwoodland or to diversify species or agestructureDeadwood • Significant quantities of deadwood, bothstanding and lying• Old and dying trees, evidence of naturalmortality and self thinningAssociated open space • Open space of high conservation valuewithin/beside woodlandGrazing • Grazing/browsing at apparentlysustainable levels and favourable for30• Monocultural overstorey of oak ordowny birch; especially where <strong>this</strong> iscommon in rest of catchment• Planted coppice oak on ash woodlandsites• Few old / large/ veteran trees• High density of small oak stemsresulting from stools not having beensingled/thinned• Shaded veteran trees• Dense regeneration of birch in oldwood pasture• Shrub layer lacking• Hazel recently coppiced as part ofcoppicing programme• Presence of excessive holly causingshading of key lichens andbryophytes species• Tree or shrub seedlings in areas ofimportant open space e.g. aroundveteran trees or in glades needed tosupport lichens. Large areas of densebirch regeneration in areas of highbotanical value woodland.• Little or no deadwood• Total exclusion of browsing andgrazing by deer fence

plant groups of interest.• Sheep excluded or only seasonal(winter) use by sheep• Controlled grazing regime in place esp.if with cattle• Deer management plan in place thatachieves acceptable deer densities• Deer damage on saplings and shrubs atacceptable levelsExotic species • Control of rhododendron, beech,sycamore or regenerating conifers inprogress.• Presence of high sheep numbersthroughout year, resulting inwidespread damage by trampling,poaching and localised erosion• Stock and deer preventing seedlingand sapling growth in areadesignated for woodlandregeneration• Presence of rhododendron, beech,sycamore or regenerating conifers• Presence of garden escapes andinvasive plants31

If it is considered helpful, different areas of the woodland can be assigned to different classesof woodland condition (poor, good, very good), using the features listed in table 2. Asimplified overview of what needs to be captured in such a categorisation is shown in table 3.This can be done if it is considered helpful to produce a map of woodland condition.Table 3: overview of categorisation into classes of woodland conditionWoodlandconditionVery goodGoodGrazing Composition Structure AntiquityDeer andstock numberscontrolled,but notexcluded.Stockexcluded.Deer atacceptabledensitiesDiverse array ofnative trees andshrubs that reflectsite conditionsand/or tree andshrub speciesdominated by speciesthat are favourablefor priority plants.No exotictrees/shrubs.Mix of early and latersuccessionaltree/shrub specieswith representationof species especiallyfavourable forpriority plant species.No or few exoticstree/shrubs.Complexstructure(canopylayers, ageclasses, gaps,deadwood)and/orstructurefavourable forpriorityplants.Somestructuraldiversity andsome areaswherestructure isfavourable forpriorityplants.Ancientwoodlandand /orpresence ofveterantrees.Ancient or‘longestablishedof plantationorigin’woodland.Some oldtrees.PoorUncontrolledgrazing atunacceptablelevelsORAll grazingtotallyexcluded foran extendedperiod (> 7years)Tree species limitedin number andrestricted to earlysuccessional species.Shrubs lacking.Exotic trees/shrubspresentORThicket regenerationproducing uniformdark, damp conditions;ivy cloaksrocks, trees & shrubs.Simplestructure andsingle ageclass.Recent,planted orlong establishedofplantationorigin.Output at <strong>this</strong> stage should include a list of woodland condition issues for entry into awoodland plan.32

Step 4 Conservation problems and prescriptionsDetermine conservation problems that can be addressed by management i.e. aspects of nonfavourablecondition for each management unit. A list of typical problems and themanagement prescription to address them are shown in section 5.2. These can be split into:• Connectivity• Grazing control• Lack of botanical diversity• Woodland structure• Woodland composition• Tree and shrub regeneration• Deadwood• Invasive exotic plant speciesDetermine the best management prescriptions to address the problems using the guidance setout in section 5.2 as a starting point. Further detail can be added by referring to specificmanagement guidance <strong>publication</strong>s. If you have selected priority species and communities forthe site, order the management prescriptions to prioritise those activities that improveconditions for those species.Outputs at <strong>this</strong> stage can be:1. A list of problems and prescriptions for entry into a management plan.2. Some of the key problems and prescriptions marked on a management prescriptionsmap.Step 5 Integration with other management objectivesManagement prescriptions for flora need to be integrated with other management objectivesfor the wood. Two issues are involved:• Consider the impacts of prescriptions for flora on other aspects of conservation or widermanagement objectives (timber production, recreation, grazing). If they haveunacceptable impacts, consider amending them.• Consider any negative impacts of management for wider objectives (productive use,recreation and grazing) on woodland plants. Amend these as necessary.Step 6 Enter information and prescriptions into planEnter the information on the botanical value, woodland condition, conservation problems andmanagement prescriptions into a plan and, importantly, the accompanying maps. This caneither be a woodland plan, woodland grazing plan or an SSSI management plan.33

5.2 Management prescriptions1. Planning issues1.1 Safeguarding areas of high botanical valueProblem: Areas with high botanical value need to be protected so as they can act as sourcesfor species to colonise adjacent lower quality woodland.Management prescriptions: Map areas of high/very high botanical value and assess featureson site to help inform a view of:• The factors that have allowed plant communities to flourish (site, topography, history,management, grazing).• The direction that natural woodland dynamics are currently taking the site (changes intree/shrub cover and composition, canopy structure, canopy gaps, light regime,deadwood, invasion of exotic species etc.)• Any small scale management activities (typically grazing, collection of firewood) thathave been carried out in the wood and whether they are compatible/incompatible withthe high botanical value.Ensure the continuation of those factors that have been favourable for plant communities andonly contemplate altered management (for plants or for other objectives) when there aresolid grounds for <strong>this</strong>. Evaluate the changes that are likely to arise in the long term as a resultof the long term operation of natural woodland dynamics. Decide if any of these need to beredirected by management intervention. Only interfere with ongoing small scale managementif it has demonstrable negative impacts.1.2 Encourage the spread of woodland plants within woodlandProblem: A key aim is to expand areas of high botanical value. This means carefulmanagement of adjacent woodland, so as to facilitate the expansion of areas of high botanicalvalue in the long term (decades).Management prescriptions: Restoration zones. Set up restoration zones around areas of highbotanical value where management focuses on creating conditions conducive for expansion ofthe woodland plants/communities in question. This will involved delineating areas at least100 m wide and ideally up to 500 m where management will be weighted towards theprescriptions set out in sections 2-7 below. Establishment of a suitable grazing regime willoften be critical. This will take many years to effect.1.3 Expansion of woodland patch/network sizeProblem: Small populations of plants in small habitat patches are generally more vulnerablethan larger populations. Atlantic woodlands are often fragmented with small patch/networksizes. A key priority is to increase the networks by joining smaller patches/networks togetherto form larger ones by creating strategically placed new woodland.Management prescriptions: Woodland expansion. Where areas of woodland of high/very highbotanical value are adjacent to open ground areas of lower conservation value, and wherethere is a net benefit to establishing new woodland (or woodland/open ground mosaics),afford high priority to woodland expansion. The best location for new woodland should bedetermined using a forest habitat network approach (see section 4 and guidance in Moseley atal. 2005 and 2007). Expansion should often be sought primarily by natural regeneration and34

should be achievable where suitable seed sources are present and especially if advancedregeneration is already in place. For species missing in the source woodland (typicallywoodland shrubs and the less common trees), consider planting small numbers of theseamongst regeneration. For guidance on woodland expansion, see Rodwell and Patterson 1994,Thompson 2004.1.4 Age diversityProblem: At a catchment scale, it is best if there is representation of a range ofwoodland/tree age classes, so new habitat can be recruited to replace mature woodland lostby disturbance/mortality. One of the clear continuing needs for Atlantic woodlands is torecruit areas of younger woodland, especially of ash and oak. Ideally, catchments lackingyoung woodland would be prioritised when planning expansion activity. This logic does notapply at the scale of single woodlands, where some even-aged areas of woodland are to beexpected, especially in alder and birch woods.Management prescription: Prioritise woodland expansion. Get rough information on the agedistribution of the type of woodland under consideration at catchment scale – probablyobservations made simply driving around in the general area would suffice. If there is littlerecent recruitment of younger woodland, prioritise sites within the catchment for expansion,especially high conservation value woods with valuable plant populations.2. Grazing control2.1 OvergrazingProblem: Grazing and browsing levels are often too high and impact negatively on woodlandplants and/or prevent establishment of woodland shrubs and/or a new generation of trees andshrubs (where <strong>this</strong> is desirable).Management prescriptions:a) Controlled grazing. Further management advice: see the woodland grazing toolkit/toolbox(Sumsion and Pollock 2006, Black & Armstrong 2009 and available atwww.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/farmingrural/SRDP/RuralPriorities/Options).b) Temporary stock or deer fencing. This should be seen as a temporary measure to effectchange in the woodland, after which it is dismantled and, ideally, controlled grazing isestablished. There needs to be a plan to set out clearly the objective of fencing, when ithas fulfilled its purpose and the arrangements for dismantling it.c) Individual protection of regenerating trees and shrubs. This can be useful in woodlandsand wood pastures where browsing is confined to roe deer and the main requirement is toestablish a new generation of scattered trees and shrubs. It is usually successful in areaswhere there are already signs that unprotected regeneration is growing beyond the seedlingstage, but being held back by deer. Protecting saplings using netting stapled to stakes isbest and tubes should be avoided, especially in shaded conditions.2.2 Total exclusion of grazingProblem: Fencing of areas to allow regeneration of trees, or as part of an exclosure for otherpurposes (e.g. adjacent conifer woodland), can lead to near total cessation of grazing, whichis detrimental for woodland flora if it continues for more than a couple of years. However,deer fencing remains an important tool for expanding woodland in the right circumstances i.e.when other forms of grazing control are impracticable. This could be when the fence is35

estricted to open ground beside wood, where it does not impinge on areas of higher botanicalvalue, where its ecological benefits clearly outweigh any associated problems or when erectedover smaller areas or for shorter time periods.Management prescription: Where fencing remains the best solution, try to avoid fencinglarger areas of woodland than necessary and avoid impinging on areas of woodland with higherbotanical value. As soon as the purpose of the fence is fulfilled, remove the fence or takeaction to re-admit grazing animals. Ideally the area would be made subject to a controlledgrazing regime. However, <strong>this</strong> is not always practical and well targeted deer control may be amore practical solution in many cases.3. Manipulating the woodland canopy to improve conditions for flora3.1 Oak monocultures: tree/shrub diversity issuesProblem: Low representation of other naturally occurring tree species in oak woodland due topast coppice management. This can lead to lack of plant species associated with the missingtree species, especially epiphytes.Management prescriptions: Diversify tree canopy species representation to reflect siteconditions. Identify areas (from small patches to whole stands) which would naturally carryspecies other than oak.• Where seed sources for other appropriate trees and shrubs exist: Search out preestablishedseedlings (e.g. ash, bird cherry, hazel) and protect from browsing with meshstapled onto stakes. Focus on seedlings growing where canopy conditions are favourable –on ‘correct’ sites types and in canopy gaps (not immediately below mature trees). In oakmonocultures, consider the need to fell individual oaks to provide light for replacementtrees/shrubs, especially if the wood is being managed with small scale oak timberproduction as one of the aims. For further management advice, refer to thinningguidelines (Thompson et al 2005).• Without seed sources for other appropriate trees and shrubs: Consider the same approachas above, but by planting of very small numbers of local provenance tree/shrub seedlingsin appropriate locations. These will act as future seed sources.3.2 Oak monocultures: tree size and structure issuesProblem: Former coppice has a very even aged and even sized structure, and <strong>this</strong> lack ofdiversity can limit occurrence of niches for epiphytes. Over the very long term, variation intree size will increase as natural mortality takes its course and a decision needs to be made asto whether natural processes are adequate or whether active management intervention isdesirable.Management prescription: Thin to promote tree size diversity. Survey the site and make anassessment of how natural mortality is proceeding and whether <strong>this</strong> might be sufficient tointroduce tree size diversity in the future. If not, consider small scale thinning, especially ifthe wood is being managed with small scale oak timber production as one of the aims.Thinning should aim to free-up larger trees and trees with good existing epiphyte communitiesby removing some of those adjacent to them. For further management advice, use fellingguidelines in Thompson (2005).36

3.3 Large /old open grown veteran treesProblem: Lack of recruitment of large/old/open grown veteran trees. These are especiallyvaluable for epiphytes.Management prescriptions:a) New woodland: Include a component of open grown trees in all new woodland. Thisshould be at spacing of 10m or more.b) Thinning scattered trees/clumps: Many woods include areas of scattered trees andsmall clumps. Some of these can be thinned by picking the largest trees and removingthe trees around them to create open grown trees.c) Establish new wood pastures: Establish areas of wood pasture by planting widelyspaced trees into pasture or aim for sporadic regeneration with increased grazinglevels after recruitment of young trees and shrubs. These will need to be wellprotected until they are beyond the vulnerable stage.Problem: Space around open grown veteran trees in-filled by regenerated or planted trees innew woodland or on fenced sites. This shades out important epiphytes and damages theveteran trees.Management prescription: Discourage regenerating trees/shrubs and/or periodic cutting withhandsaw, brushcutter or chainsaw and by re-instituting grazing.3.4 Woodland / open space mosaics and gladesProblems: Some plant and fungi species, especially lichens, thrive in woodlands containing amosaic of woodland and open space in the form of glades, and there is the danger of thesemosaics being lost either due to loss of woodland (lack of regeneration due to grazing) orexcessive regeneration.Management prescription: Identify important areas of woodland / open space mosaic andconsider what needs to be done to perpetuate them; either where the woodland component isbeing lost, by protecting seedlings/saplings or instituting controlled gazing or where gladesare being lost, by grazing or cutting out unwanted regeneration of trees and shrubs.4. Woodland shrubs and scrub4.1 Under-representation of shrubsProblem: Under-representation of shrubs in woodland, especially birch and oak woods. Thiscan limit niches for epiphytes.Management prescription: Recruit shrubs ideally by natural colonisation using approachesoutlined in 2.1 above, resorting to small scale planting only when there is no realistic hope ofnatural colonisation due to distance to seed sources. Note that a dense understory of shrubswould probably not favour lower plants.4.2 Veteran hazel standsProblem: Potential loss of veteran hazel stands by inappropriate cutting / coppicing. Loss ofkey habitat for epiphytes, notably hazel gloves. Ancient hazel stands on the west coast maynot look old, being composed of slender and medium stems and are not the result of pastcoppicing. Coppicing (cutting back the entire stool) should never be instated on these sites.Management prescription: Avoid coppicing hazel in Atlantic woodlands. Any coppicing, ifappropriate, should be limited to selected individual stems and should only harvest a lowpercentage of shoots (see SNH undated). Avoid underplanting pure hazel stands with other37

species that will eventually over top and shade them out.4.3 Shading of lower plant communitiesProblem: Heavy levels of shading by some shrubs, including holly, can potentially damagebryophyte communities if they regenerate widely in an area of high botanical importance. Atthe same time holly can be an important element of diversity in oakwoods.Management prescription: Small scale removal of holly on key sites. Survey key sites and cutout shrubs where <strong>this</strong> necessary.5. DeadwoodProblem: Deadwood of all types is an important habitat for many lower plant species, and istypically present in insufficient quantities in Scottish woods. This is largely the result of pastmanagement practices. However, woods where timber is removed for firewood are more likelyto be lacking deadwood.Management prescription: Attempt to restrict firewood collection to sites of lower botanicalvalue. Ensure that the management plan has a statement on the amount and type ofdeadwood present, its value for plants and the prospects for more arriving by naturalmortality of trees and branches. If desirable, an inventory of deadwood can be carried out andthe quantities present estimated (m 3 /ha) to get an idea about how far the amount present isfrom recommended levels, usually at least 40-100 m 3 /ha (Forest Enterprise 2002). On siteswhere deadwood is an important habitat, enter into negotiations with any local interests thatmay be currently, or in the future, extracting timber and agree suitable practices in terms ofvolumes to be harvested and retention of deadwood to ensure that firewood collection issustainable.6. Control of invasive non native plant species6.1 Rhododendron ponticumProblem: Severe damage to all plant groups and habitats caused by presence and rapidexpansion of Rhododendron ponticum, which casts severe shade and quickly develops into adense monoculture.Management prescription: Use the management decision tool devised in Long and Williams(2008) and Edwards (2007) to identify appropriate control techniques, which should be part ofa strategic, landscape scale management plan. On sites with priority bryophyte and lichenspecies and habitats still present, consider using stem treatment control techniques (Edwards2007). On sites with dense, flowering Rhododendron ponticum, which has completelydominated the habitat, remove Rhododendron ponticum using the most appropriatetechnique. This could include lever and mulch (Kennedy 2009), and cutting or stem treatment(Edwards 2007). Ensure that control is part of a landscape scale management plan to preventre-invasion from adjacent sites. Ensure that targeted rhododendron populations areresponding to control and reserve contingency funding for additional control work ifnecessary.6.2 Beech treesProblem: Local loss of ground flora and lichen interest as a result of shading and accumulationof leaf litter, especially on oak woodland sites. However old beech trees can diversify fungalcommunities and can be a reasonable substrate for some lichen species.38