Access PDF version - Asian Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Network

Access PDF version - Asian Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Network

Access PDF version - Asian Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Network

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

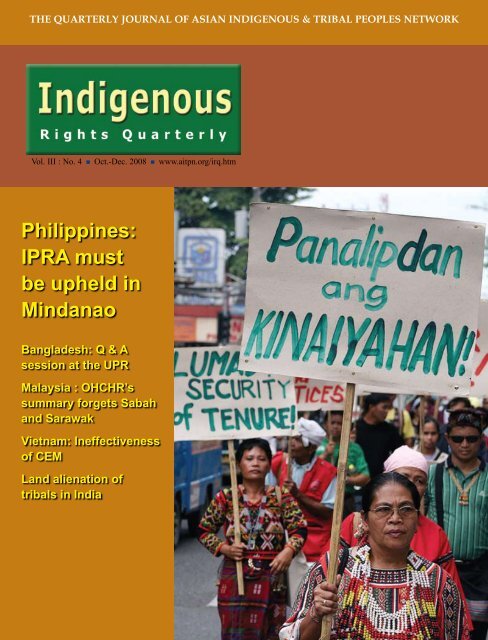

contentsEditorial 1Philippines: IPRA must be upheldin peace agreement on Mindanao 2Bangladesh: Q& A session at the UPR 5Editor-in-Chief: Paritosh ChakmaCover photos:Courtesy: www.mindanao.comSubmit articles/letters/news:IRQ welcomes articles ranging from1200 to 2000 words. Any article submittedmust be exclusive - the articlemust not have been published or submittedto other publications.Malaysia at UPR: OHCHR’ssummary forgets Sabah <strong>and</strong> Sarawak 8New Delhi Guidelines on theEstablishment of NationalInstitutions on the Rightsof <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> 11The Government Committeeis Not Enough : CEMA of Vietnam 16The Ministry of Chittagong Hill TractsAffairs of Bangladesh : An Agency forDiscrimination 18The Department of Orang Asli Affairs,Malaysia : An Agency for Assimilation 21L<strong>and</strong> Alienation of <strong>Tribal</strong>s in India 25If you have news on indigenousissues, please send them to us.You can also send comments, clarificationsor letters to the articles published.IRQ reserves the right to edit with thefinal approval of the writers/authors.Subscriptions:Single copy: US$ 5 + postageYearly: US$ 20 + postageContacts:Articles for submission, letters to theeditor or any query should be sent tothe editor by email at: aitpn@aitpn.org© <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>Tribal</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>Network</strong>. All rightsreserved. Reproduction is prohibitedwithout the prior permission of AITPN.<strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong> & <strong>Tribal</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>Network</strong>C-3/441 (Top Floor), Janakpuri, New Delhi 110058, INDIATel/Fax: +91 11 25503624Website: www.aitpn.org; Email: aitpn@aitpn.org

<strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights Quarterly Vol. III : No. 4 • October-December 2008 1The formation of a new peace panelby the Government of Republic ofPhilippines on 25 December 2008for resumption of the stalled peaceprocess with the Moro IslamicLiberation Front (MILF) is welcome.AITPN also takes note of the fivepointpreconditions announced by theCentral Committee of the MILF on 26December 2008 for resumption of thetalks. The talks were stalled followingdeclaration of the Memor<strong>and</strong>um ofAgreement on Ancestral Domainon Bangsamoro Juridical Entity”(MOA-AD-BJE) between thegovernment of Philippines <strong>and</strong> theMILF as unconstitutional by theSupreme Court on 14 October 2008.What followed were humanitari<strong>and</strong>isasters, especially for theindigenous peoples, caused by thearmy <strong>and</strong> the socalled renegades ofthe MILF.The conditions put by the MILF,among others, include (i) having aninternational guarantee composedof states or association of states toensure that both the Government<strong>and</strong> MILF will honor <strong>and</strong> implementagreement or agreements forged bythe parties; (ii) change in the st<strong>and</strong>of Government over the MOA-ADas ‘no deal’ <strong>and</strong> ‘unconstitutional’ inthe aftermath of the Supreme Courtjudgement of 14 October 2008; <strong>and</strong>(iii) Malaysia to stay as facilitator ofthe peace talks.In fact all the international actorsinterested in the peace process inMindanao, in particular, Malaysia,Japan <strong>and</strong> the United Statesmust recognize the diversityof the conflict in Mindanao <strong>and</strong>ensure that the rights of indigenouspeoples, who are numericalminorities, are not subsumed forpeace with the MILF.editorialPhilippines: Indispensability of the IPRAfor peace in MindanaoObviously, the legitimate questionarises as to who are the indigenouspeoples of Mindanao. Many Morosclaim themselves as indigenous.AITPN does not dispute their claims.However, the fact remains thatthe Bangsamoros are not legallyrecognised as indigenous peoplesunder the <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>Rights Act (IPRA) of 1997. The IPRAlists 110 ethno linguistic groups ofPhilippines as indigenous peoplesbut Bangsamoros are not included.Many Moros opine that their nonrecognitionas indigenous peoples isan act of discrimination by Christi<strong>and</strong>ominated Filipinos.At the same time, in the existingAutonomous Region of MuslimMindanao (ARRM) – a product ofthe peace process with the Moros, the<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> Rights Act of 1997is not applicable. The experiencesof the indigenous communities ofTeduray, Lambangian <strong>and</strong> DulanganManobo of Maguindanao <strong>and</strong> SultanKudarat provinces whose AncestralDomains of 400,000 hectares wereincluded have not been encouraging.In the ARMM Act, there is noprovision for titling of ancestraldomains of the indigenous people asprovided under the IPRA. Absenceof title means lack of tenurial security<strong>and</strong> therefore lack of ownership.Having the powers of eminentdomain, the Regional Government ofthe ARMM under section 3 of ArticleV of the ARMM Act has the authorityto acquire/take over the ancestraldomain of the indigenous peopleciting public interest.The IPRA whose constitutionalvalidity has been upheld by theSupreme Court has been relegatedto oblivion. The token representationfrom indigenous communities hasnot been helpful. Under Clause1 under heading “Concepts <strong>and</strong>Principles” of the MOA-AD-BJE, theBangsamoro identity is imposed onthe indigenous peoples. It providesthat, “It is the birthright of all Moros<strong>and</strong> all <strong>Indigenous</strong> peoples of Mindanaoto identify themselves <strong>and</strong> be accepted as“Bangsamoros”. The Bangsamoro peoplerefers to those who are natives or originalinhabitants of Mindanao <strong>and</strong> its adjacentisl<strong>and</strong>s including Palawan <strong>and</strong> the Suluarchipelago at the time of conquest orcolonization <strong>and</strong> their descendantswhether mixed or of full native blood.Spouses <strong>and</strong> their descendants areclassified as Bangsamoro. The freedom ofchoice of the <strong>Indigenous</strong> people shall berespected.”For indigenous peoples, it is a matterof rights recognized under the IPRA<strong>and</strong> not freedom of choice that thegovernment of Philippines <strong>and</strong> theMILF would like to espouse. Anypeace agreement with the MILFmust explicitly recognize that the<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> Rights Act of1997 shall prevail. Without suchexplicit reference, indigenouspeoples of Mindanao shall loosetheir rights.Unless Bangsamoros recognizethe applicability of the IPRA inany future agreement with thegovernment of Philippines, theMoros themselves can be accusedof committing the same act ofdiscrimination for which theyrightly point the fingers towards theChristian dominated Filipinos.Recognition of rights of indigenous<strong>Peoples</strong> through explicit reference tothe IPRA remains fundamental.

2<strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights Quarterly articleVol. III : No. 4 • October-December 2008Philippines: IPRA must be upheld in peaceagreement on MindanaoOn 25 December 2008, the governmentof Philippines formed a new peacepanel consisting of three membersfor negotiation with the MoroIslamic Liberation Front (MILF).On 26 December 2008, the MILFCentral Committee announced itspreconditions, which, among others,included (i) having an internationalguarantee composed of states orassociation of states to ensure thatboth the Government <strong>and</strong> MILF willhonor <strong>and</strong> implement agreement oragreements forged by the parties; (ii)change in the st<strong>and</strong> of Governmentover the Memor<strong>and</strong>um of Agreementon Ancestral Domain on BangsamoroJuridical Entity” (MOA-AD-BJE)as ‘no deal’ <strong>and</strong> ‘unconstitutional’in aftermath of the Supreme Courtjudgement of 14 October 2008; (iii)continuance of Malaysia as thefacilitator of the peace talks.While the peace process must resumesoon, it is not yet clear as to whetherthe Memor<strong>and</strong>um of Agreement onAncestral Domain on BangsamoroJuridical Entity” (MOA-AD-BJE)declared unconstitutional by theSupreme Court will form the basisof the peace talks. What is clear isthat the rights of indigenous peoplesare being abrogated both in thepeace process <strong>and</strong> the final outcomedocument.I. MoA-AD-BJE in the present form- a deadly knock for indigenouspeoplesa. Total disregard of the <strong>Indigenous</strong><strong>Peoples</strong>’ Rights ActThe <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> Rights Actof 1997 provides for the “right tofree <strong>and</strong> prior informed consent”.Unless the Bangsamorosrecognize the applicabilityof the IPRA in any futureagreement with thegovernment of Philippines,the Moros themselves can beaccused of committing thesame act of discrimination forwhich they rightly point thefingers towards the Christi<strong>and</strong>ominated government.However, in the whole peace processthat culminated in the form of MOA-AD-BJE, both the Government <strong>and</strong> theMILF failed to ensure respect for theindigenous peoples. This is despitethe fact that many indigenous peopleswho do not identify themselvesas Bangsamoros are supposed tobe subsumed in the Bangsamoroidentity. As per Clause 2 under theheading “Territory” of the MOA-AD-BJE, the territorial extent of the BJE isidentified as three categories of areasviz. (i) Core area of BJE, (ii) CategoryA areas, <strong>and</strong> (iii) Category B areas.All the three categories of areas covervast tracts of ancestral domains ofthe indigenous peoples in a numberof provinces.Inclusion of indigenous peoples in thepeace process has been only a tokenattempt on the part of both the MILF<strong>and</strong> the government of Philippinesto impress upon the indigenouspeoples. While the government ofPhilippines does not consider theindigenous peoples including theLumads as necessary party solely onthe ground that they are not engagedin armed conflicts, the MILF soughtto assimilate indigenous peoplesunder the Bangsamoro identity.b. Imposition of “Bangsamoro”identity on the indigenous peopleThe MOA-AD-BJE imposes the“Bangsmoro” identity on theindigenous people. This is clear froma simple reading of Clause 1 underheading “Concepts <strong>and</strong> Principles”,the MOA-AD-BJE which reads,“It is the birthright of all Moros <strong>and</strong> all<strong>Indigenous</strong> peoples of Mindanao toidentify themselves <strong>and</strong> be acceptedas “Bangsamoros”. The Bangsamoropeople refers to those who are nativesor original inhabitants of Mindanao<strong>and</strong> its adjacent isl<strong>and</strong>s includingPalawan <strong>and</strong> the Sulu archipelago atthe time of conquest or colonization<strong>and</strong> their descendants whether mixedor of full native blood. Spouses <strong>and</strong>their descendants are classified asBangsamoro. The freedom of choiceof the <strong>Indigenous</strong> people shall berespected.”The above clause states that allMoros <strong>and</strong> indigenous peoples ofMindanao have the birth right toidentify themselves <strong>and</strong> acceptedas Bangsamoro. However, the 1987Constitution of Philippines identifiedthe indigenous peoples as <strong>Indigenous</strong>Cultural Communities (ICCs). In 1997,the IPRA used the term “indigenouspeoples” to identify the 110 ethnolinguistic groups of Philippines<strong>and</strong> formally recognized them as

<strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights Quarterly articleVol. III : No. 4 • October-December 2008 3indigenous peoples. The Moros arenot listed as one of the indigenouspeoples. Yet, the MOA-AD-BJEseeks to subsume the identity of allindigenous peoples of Mindanaounder the Bangsamoro identity. Thisis an attempt of forced assimilation ofthe indigenous people by the Moropeople aimed at destroying theirestablished formal identity.c. Denial of the right of selfdeterminationof indigenouspeoplesThe IPRA provides for the rightof self-governance of indigenouspeoples through a number of rightsincluding the rights to ancestraldomains (sections 4-12), rights tosocial justice <strong>and</strong> human rights(sections 21-28); right to culturalintegrity (sections 29-37) <strong>and</strong> theestablishment of the NationalCommission on <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>consisting of indigenous peoples.Section 17 of IPRA specificallyprovides that the indigenous peopleshave the right to determine <strong>and</strong>to decide their own priorities fordevelopment affecting their lives,beliefs, institutions, spiritual wellbeing,<strong>and</strong> the l<strong>and</strong>s they own,occupy or use. They also have theright to participate in the formulation,implementation <strong>and</strong> evaluationof policies, plans <strong>and</strong> programsfor national, regional <strong>and</strong> localdevelopment which may directlyaffect them.Section 15 further provides that theindigenous peoples shall have theright to use their own commonlyaccepted justice systems, conflictresolution institutions, peace buildingprocesses or mechanisms <strong>and</strong> othercustomary laws <strong>and</strong> practices withintheir respective communities.Section 13 also provides thatthe government of Philippinesrecognizes self-governance <strong>and</strong> selfdeterminationas inherent rights ofindigenous people. It also providesthat the State respects the integrity oftheir values, practices <strong>and</strong> institutions<strong>and</strong> shall guarantee the right of ICCs/IPs to freely pursue their economic,social <strong>and</strong> cultural development.As no reference to the IPRA Actis made in the MOA-AD-BJE,indigenous peoples are all set to losetheir right of self-determination.d. Regression of all other rightsprovided under IPRAFor indigenous peoples recognizedas such under the IPRA of 1997,the MOA-AD-BJE of 4 August 2008would have constituted a regressionof rights.Under the IPRA, the right toancestral domain includes the rights- of ownership; to develop l<strong>and</strong>s<strong>and</strong> natural resources; to stay in theterritories; in case of displacement; toregulate entry of migrants; to safe <strong>and</strong>clean air <strong>and</strong> water; to claim parts ofreservations; <strong>and</strong> to resolve conflict.Self-Governance <strong>and</strong> Empowermentis recognized as an inherent right ofthe indigenous peoples <strong>and</strong> they havethe right to determine <strong>and</strong> decidetheir own priorities for developmentaffecting their lives, beliefs,institutions, spiritual well-being, <strong>and</strong>the l<strong>and</strong>s they own, occupy or use.They also have the right to participatein the formulation, implementation<strong>and</strong> evaluation of policies, plans<strong>and</strong> programs for national, regional<strong>and</strong> local development which maydirectly affect them.The provisions on social justice<strong>and</strong> human rights includes- equalprotection <strong>and</strong> non-discrimination ofICC/IPs (section 21), right to specialprotection <strong>and</strong> security in periods ofarmed conflict (section 23), freedomfrom discrimination <strong>and</strong> right toequal opportunity <strong>and</strong> treatment(section 23), right to basic services ofthe state (section 25) etc.The indigenous people have the rightto preserve <strong>and</strong> protect their culture,traditions <strong>and</strong> institutions (section29). The state is under legal obligationto provide equal opportunities to theindigenous peoples through a mannerappropriate to their cultural methodsof teaching <strong>and</strong> learning. They arealso entitled to the recognition ofthe full ownership <strong>and</strong> control <strong>and</strong>protection of their cultural <strong>and</strong>intellectual rights.However, no such provision has beenmade under the MOA-AD-BJE.II. Experiences of <strong>Indigenous</strong>peoples within ARMMThe experiences of the indigenouscommunities of Teduray,Lambangian <strong>and</strong> Dulangan Manoboof Maguindanao <strong>and</strong> Sultan Kudaratprovinces whose Ancestral Domainsof 400,000 hectares were includedin the existing Autonomous Regionof Muslim Mindanao (ARMM)has not been encouraging. ThoughARMM Act predates the IPRA, whileadopting IPRA <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong>ing theARMM, no reference was made aboutthe applicability of the IPRA in theARMM. In reality, there is no legal barfor applying the IPRA in the ARRM.However, in reality the ARMMauthorities only apply the ARRMAct <strong>and</strong> not the IPRA. Consequently,non-Muslim indigenous communitiesliving under the ARMM were furthermarginalised.a. Limited ownership over ancestraldomainsIn comparison to IPRA, the concept ofancestral domain under the ARMMAct is restrictive <strong>and</strong> incomplete.Section 1 of Article XI of the ARMMAct excludes “strategic minerals such

4<strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights Quarterly articleVol. III : No. 4 • October-December 2008as uranium, coal, petroleum, <strong>and</strong> otherfossil fuels, mineral oils, <strong>and</strong> all sourcesof potential energy; lakes, rivers <strong>and</strong>lagoons; <strong>and</strong> national reserves <strong>and</strong> marineparks, as well as forest <strong>and</strong> watershedreservations” from the definition ofancestral domain.Further, in the ARMM Act, there isno provision for titling of ancestraldomains of the indigenous peoples.Absence of title means lack oftenurial security <strong>and</strong> therefore lackof ownership. Having the powersof eminent domain, the RegionalGovernment under section 3 ofArticle V of the ARMM Act has theauthority to acquire/take over theancestral domain of the indigenouspeople citing public interest. Undersection 2 of Article XI of the ARMMAct, right to ancestral domain inrespect of constructive or traditionalpossession of l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> resourcesis already dependent upon judicialaffirmation, which has not beendefined in the law.The safeguards against transfer/conveyance of ancestral domain tonon-indigenous peoples under theARMM Act are very weak. Section6 of Article XI of the ARMM Actprovides, “unless authorized bythe Regional Assembly, l<strong>and</strong>s of theancestral domain titled to or owned by anindigenous cultural community shall notbe disposed of to nonmembers” whichmeans that the Regional Assemblyis the authority to grant permit fordisposing off l<strong>and</strong>s of ancestraldomains to non-members (who isnot a domain holder). Effectively,indigenous peoples’ rights toancestral domain/l<strong>and</strong> are at themercy of the Regional Assembly. But,it is the not case under IPRA, it is theindigenous community who has theright to decide what to do or what notdo with their ancestral domain, albeitin conformity with relevant nationallaws <strong>and</strong> policies.Unlike the ARMM Act, the right toancestral domains under the IPRA isvery strong <strong>and</strong> there are clear <strong>and</strong>precise provisions on delineation<strong>and</strong> titling of ancestral domains<strong>and</strong> ancestral l<strong>and</strong>s by the NCIP byissuance of CADT or CALT. Thesetitles are again registered with theL<strong>and</strong> Registration Authority.The requirement of free <strong>and</strong> priorinformed consent acts like shieldagainst any attempt to dispossess orwrongfully deprive the indigenouspeople of their right to ancestraldomains.b. No right to determine <strong>and</strong> decidetheir own developmentAs discussed above, the ARMMAct recognizes only the indigenouspeoples’ right to ancestral domainsubject to some limitation <strong>and</strong> riders.The ARMM Act does not provide forthe indigenous peoples’ right to selfgovernance<strong>and</strong> self-determinationunlike section 13 of <strong>Indigenous</strong><strong>Peoples</strong> Rights Act of 1997.Section 17 of IPRA further re-enforcesthe right to self-governance <strong>and</strong> selfdetermination.A con-joint reading to sections 13<strong>and</strong> 17 read with section 7 of IPRA,which provides for rights to ancestraldomain means that the indigenouspeople have the right to determine<strong>and</strong> decide their own priorities fordevelopment <strong>and</strong> it is the duty ofthe State to guarantee their rightto freely pursue their economic,social <strong>and</strong> cultural development intheir ancestral domains <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>s.Right from having ownership, theindigenous people have the right todevelopl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> natural resources;stay in the territories; remedies,including compensation in caseof displacement; regulate entry ofmigrants; safe <strong>and</strong> clean air <strong>and</strong>water; claim parts of reservations; toresolve conflict.c. No provisions for affirmativeactions for indigenous peoplesunder the under ARMM ActThe IPRA provides for an array ofaffirmative action programs in favourof the indigenous peoples. Amongothers, these include – (i) right toself-governance <strong>and</strong> empowerment(Sec. 13); (ii) right to participate indecision making (Sec.16); (iii) specialmeasures for basic services (Sec.25);(iv) special provisions for AncestralDomains Fund (Sec. 71) etc.On the other h<strong>and</strong>, except theprovision to formulate <strong>and</strong> implementspecial development programs <strong>and</strong>projects, responsive to the particularaspirations, needs <strong>and</strong> values of theindigenous cultural communitiesunder section 2 of Article XII, theARMM Act has no other provisionsfor affirmative action for theindigenous peoples.III. Self-identification as IPs vs.recognition under IPRASelf-identification or self-ascription isone of the criteria for determinationas indigenous or tribal group. In thisregard, Article 1(2) of ConventionNo. 169 of the International LabourOrganisation (ILO) reads,“Self-identification as indigenous ortribal shall be regarded as a fundamentalcriterion for determining the groups towhich the provisions of this Conventionapply.”In Section 3 (h), IPRA also providesthat indigenous peoples/indigenouscultural communities refer to a groupof people or homogenous societiesidentified by self-ascription or byothers.Undoubtedly, the Moros havean inalienable right to identifythemselves as indigenous peopleof Philippines. But, they have not

<strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights Quarterly articleVol. III : No. 4 • October-December 2008 5been classified as indigenous unlikethe 110 ethno linguistic groupswho have been recognized underthe IPRA.Bangladesh: Q & A sessionat the UPRWhile the Moros term this exclusionfrom the list of 110 ethno-linguisticgroups as an act of discrimination,the MILF <strong>and</strong> many other Morogroups have been committing thesame act of discrimination againstindigenous peoples recognizedunder the IPRA. It is also the dutyof the Government of Philippines<strong>and</strong> the MILF that the rights of theindigenous people whose rightsare recognized <strong>and</strong> protectedunder IPRA are not violated whileexercising the right to selfdeterminationof the Moros.<strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tribal</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong><strong>Network</strong> recommends to thegovernment of Philippines <strong>and</strong> theMILF to ensure the following in anyfuture peace process:- Make specific reference in anyfuture agreement with the MILFthat the <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>Rights Act of 1997 shall apply inany proposed area for BangsaMoro Judicial Entity;- include Chairperson of theNational Commission on<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> of thePhilippines in the PeaceSecretariat of the governmentof Philippines;- delineated Ancestral Domainsof the non-Muslim indigenouscommunities be recognised<strong>and</strong> protected in any peacenegotiation between theGovernment <strong>and</strong> the MILF inthe future; <strong>and</strong>- include representatives ofthe non-Muslim indigenouscommunities in any peacenegotiation between theGovernment <strong>and</strong> the MILF.The Working Group of the UniversalPeriodic Review of the HumanRights Council is scheduled toexamine Bangladesh on 3 February2009. The government of Bangladeshhas submitted its report (A/HRC/WG.6/4/BGD/1). As manyas 17 stakeholders (civil societyorganizations), including <strong>Asian</strong><strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tribal</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong><strong>Network</strong> (AITPN) 1 , have contributedto the process for effective scrutinyof the human rights situation ofBangladesh.The submission of Bangladeshis economical with the truth <strong>and</strong>presented a hunky-dory situation inthe country while ignoring criticalhuman rights issues facing thecountry.Since the submission of the reportby the government of Bangladesh<strong>and</strong> stake-holders, major changeshave taken place in the country. TheNational Human Rights Commissionwas established through an Ordinance<strong>and</strong> the Right to InformationOrdinance was promulgated.Most importantly, the AwamiLeague won the national electionsheld on 29 December 2008 <strong>and</strong> a newgovernment led by Prime MinisterSheikh Hasina has been formed sincethen.In the light of these developments,<strong>Asian</strong> Coalition on UPR submits thefollowing to be raised at the WorkingGroup on UPR:a. Elections in the CHTs RegionalCouncilsThe parliamentary elections held on29 December 2008 <strong>and</strong> the UnionParishad elections being held shouldbe welcomed.However, no election has been heldin the local bodies of the ChittagongHill Tracts (CHTs). The CHTsRegional Council established in1998 did not have any elections.The last elections in the Hill DistrictCouncils of Rangamati, B<strong>and</strong>arban<strong>and</strong> Khagrachari were held in 1989by then President General H MErshad. The Hill District Councils<strong>and</strong> the Regional Council are beingrun by appointees of the authoritiesin Dhaka.The government of Bangladeshshould be asked as to when theelections in the Hill District Councils<strong>and</strong> the Regional Council will beheld.The members of the Working Groupon UPR should recommend thegovernment of Bangladesh to holdthe elections in the Hill DistrictCouncils <strong>and</strong> the Regional Council ofthe CHTs as early as possible.b. Implementation of the CHTsPeace AccordThe present government ofBangladesh headed by Awami Leagueis the one that has signed the CHTsPeace Accord in December 1997. Inthe last 11 years, the CHTs Accordhas not been implemented. The armycamps have not been withdrawn asrequired under Section 17 (a) of PartD of the Peace Accord <strong>and</strong> the CHTL<strong>and</strong> Commission established underSection 4 of Part D of the Peace Accordfailed to take off <strong>and</strong> not a single caseof l<strong>and</strong> dispute has been resolved.A total of 9,780 families out of total

6<strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights Quarterly articleVol. III : No. 4 • October-December 200812,222 Jumma families who returnedfrom India following the CHT PeaceAccord have not got back their l<strong>and</strong>s,orchards or gardens <strong>and</strong> homestead.In May 2000, Task Force Committeeidentified 90,208 Jumma families<strong>and</strong> 38,156 non-tribal Bengali settlerfamilies as “internally displacedfamilies” in CHTs. 2 In addition, therewere some 10,000 tribal IDP familieswho were left out by the Task Force.By including the non-tribal IDPs,the government sought to legitimizethe settlement of the Muslims fromthe plains in the CHTs under theState-sponsored ethnic cleansingprogramme. While the Jumma IDPswere not provided any rehabilitationor food aid, educational facilities,health care services, sanitation <strong>and</strong>safe drinking water etc, illegal settlerfamilies have been provided freerations <strong>and</strong> other facilities by thegovernment since 1978. 3On the other h<strong>and</strong>, indigenouspeoples <strong>and</strong> their l<strong>and</strong>s continueto be targeted. In 2008, the SpecialRapporteur on the situation of humanrights <strong>and</strong> fundamental freedomsof indigenous people sent a jointcommunication calling the attentionof the Government to the allegedillegal seizure of the traditional l<strong>and</strong>sof indigenous communities in the CHT<strong>and</strong> systematic campaign to supportthe settlement of non-indigenousfamilies in the CHTs with the activesupport of the security forces, withthe ultimate aim of displacing theindigenous community. 4The government of Bangladesh shouldbe questioned as to what measures itwill take to fully implement the PeaceAccord especially withdrawal of thearmy camps, functioning of the CHTsL<strong>and</strong> Commission <strong>and</strong> addressingthe issues raised by the SpecialRapporteur. The government ofBangladesh must also be questionedon the steps taken to ensure full<strong>and</strong> proper rehabilitation of all theThe government of Bangladeshshould be asked to make thereport of the one-man JudicialInvestigationCommissionas well as the action takenreport including details ofpunishments awarded to theguilty along with the names<strong>and</strong> designation of the personsfacing criminal proceedingspublic.returnee indigenous Jumma refugees<strong>and</strong> indigenous IDPs.c. Return of the Enemy Properties:In 2000 the Special Rapporteur onreligious intolerance, after receivinginformation about appropriation ofproperty under Vested Property Act,recommended the government ofBangladesh to ensure full restorationof properties of the Hindu community<strong>and</strong> the Hurukh/Oroan tribes. 5 NewDelhi-based <strong>Asian</strong> Centre for HumanRights (ACHR) in its UPR submissionnoted that Hindu minorities continuedto be targeted <strong>and</strong> their religiousfreedoms violated. It is reportedthat some 1.2 million or 44 per centof the 2.7 million Hindu householdsin Bangladesh were affected by theEnemy Property Act, 1965 <strong>and</strong> theVested Property Act, 1974 whichempowers to identify the Hindus asenemies of the State <strong>and</strong> seize theirproperties. 6 According to an estimate,approximately 2.5 million acres ofl<strong>and</strong> of the Hindus was seized underthe Vested Property Act until the Actwas scrapped in 2001. 7The current government ofBangladesh led by Awami Leaguewas the one which adopted EnemyProperties Return Act 2001 with aview to restoring ownership of thelost l<strong>and</strong> to the Hindu families. But nomeasure has been taken to implementthe Act. According to a recent study byAbul Barkat, professor of economicsat Dhaka University, nearly 200,000Hindu families have lost over 40,000acres of l<strong>and</strong> since 2001. 8The government of Bangladesh shouldbe questioned as to what measuresit will take to fully implement theEnemy Properties Return Act 2001<strong>and</strong> restore the seized l<strong>and</strong>s of theHindus.d. Human Rights Defenders:AITPN expresses concerns about thepersecution of the indigenous humanrights defenders in Bangladesh.The government has been seekingto establish an Eco-Park in theModhupur forest area under Tangaildistrict at the cost of displacement <strong>and</strong>survival of about 25,000 indigenousGaro <strong>and</strong> Koch peoples.On 27 April 2007, the SpecialRapporteur on the situation of humanrights <strong>and</strong> fundamental freedoms ofindigenous people jointly with theSpecial Rapporteur on extrajudicial,summary or arbitrary executions <strong>and</strong>the Special Rapporteur on the questionof torture asked the government ofBangladesh to investigate the killingof Choles Ritchil <strong>and</strong> the ill-treatmentof Protab Jamble, Piren Simsang <strong>and</strong>Tuhin Hadima, <strong>and</strong> prosecute theguilty as well as to compensate thevictims <strong>and</strong> Mr. Ritchil’s family. Inits reply submitted on 11 October2007, the government of Bangladeshstated that a one-member JudicialInvestigation Commission headed bya retired District Judge has been set upto investigate the killing of CholeshRitchil. Four persons belongingto Armed Forces were awardedpunishments, which includedremoval from service <strong>and</strong> exclusion

<strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights Quarterly articleVol. III : No. 4 • October-December 2008 7from promotion. Finally, a numberof other individuals, including publicofficials, doctors <strong>and</strong> forest officials,had also been subject to criminalproceedings.The government of Bangladeshshould be asked to make publicthe report of the one-man JudicialInvestigation Commission <strong>and</strong> theaction taken report including detailsof punishments awarded to theguilty along with the names <strong>and</strong>designation of the persons facingcriminal proceedings.e. Accountability for extrajudicialexecutionsIn the stakeholders’ summary (A/HRC/WG.6/4/BGD/3) it has beenpointed out by several stakeholdersthat the security forces of Bangladeshhave been responsible for systematic<strong>and</strong> widespread “extrajudicialexecutions”, arrest <strong>and</strong> routine useof torture with impunity. AITPNnoted that the continued presence<strong>and</strong> expansion of military basescontributes to the ongoing humanrights abuses including extrajudicialkillings in the Chitagong HillTracts (CHT). 9 According to humanrights group Odhikar, a total of 319persons have been killed by the lawenforcement personnel during thefirst 23 months of state of emergency(11 January 2007 to 11 December2008). Of them, 155 persons werekilled by the Rapid Action Battalion(RAB) <strong>and</strong> 118 by the police. 10The government of Bangladeshshould be asked what measuresare being taken for establishingaccountability into the killings byRapid Action Battalion, the police<strong>and</strong> other security forces.f. National Human RightsCommissionThe care-taker government ofBangladesh should be welcomedfor the establishment of a NationalThe government of Bangladeshshould also be asked whatmeasures will be taken forenactment of a law includingguarantees for inclusionof religious minorities <strong>and</strong>indigenous/tribal peoples asmembers of the NHRC.Human Rights Commission <strong>and</strong>appointment of the members.The government of Bangladeshshould be asked what measureswill be taken for enactment of a lawincluding guarantees for inclusion ofreligious minorities <strong>and</strong> indigenous/tribal peoples as members of theNHRC.g. Right to Information OrdinanceOn 20 September 2008, the Caretakergovernment approved the Right toInformation Ordinance, 2008 <strong>and</strong> itcame into effect on 20 October 2008with the publication in the officialBangladesh Gazette.The Working Group on UPR shouldask the democratically electedgovernment of Sheikh Hasina to passthe Right to Information Ordinance inthe Parliament <strong>and</strong> to provide furtherinformation about the establishmentof the Information Commissionprovided for under the Right toInformation (RTI) Ordinance, 2008 toimplement the RTI Ordinance.h. Cooperation with human rightsmechanismsThe government of Bangladesh failedto comply with its treaty reportingobligation to submit periodic reportsto treaty bodies. Bangladesh’stwelfth to fourteenth report to theCERD is overdue from 2002 to 2006;initial <strong>and</strong> second report to CESCRis overdue from 2000 to 2005; initialreport to HR Committee is overduesince 2001; first to third reports toCAT is overdue since 1999 to 2007;Second report to OP-CRC-AC isoverdue since 2007. 11Bangladesh has also failed to ratify anumber of key international humanrights instruments including theInternational Labour OrganizationConvention No. 169 concerning<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tribal</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> inindependent countries.The government of Bangladeshshould be asked to submit its pendingperiodic reports to the treaty bodies<strong>and</strong> to ratify the ILO Convention No.169 <strong>and</strong> other international humanrights instruments which it has notyet ratified.(Footnotes)1. AITPN’s submission “Bangladesh: We wantthe l<strong>and</strong>s, not the indigenous peoples” canbe read online at http://www.aitpn.org/UN/UPR-Bangladesh.pdf2. Parbatya Chattagram Jana Samhati Samiti,Bangladesh3. <strong>Asian</strong> Centre for Human Rights – SouthAsia Human Rights Index 2008, BangladeshChapter4. Para 39, A/HRC/WG.6/4/BGD/25. Para 40, A/HRC/WG.6/4/BGD/26. Para 48, A/HRC/WG.6/4/BGD/37. Religious minorities vulnerable inBangladesh: US, Hindu JanajagrutiSamity, 17 September 2007, http://www.hindujagruti.org/news/3028.html8. Bangladeshi Hindus loose property: study,Economic Times, 26 May 20079. Para 20, A/HRC/WG.6/4/BGD/310. 23 Months of State of Emergency inBangladesh , Odhikar, 12 December 2008available at http://www.odhikar.org/documents/23months_report.pdf11. A/HRC/WG.6/4/BGD/2

8<strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights Quarterly articleVol. III : No. 4 • October-December 2008Malaysia at UPR: OHCHR’s summary forgetsSabah <strong>and</strong> SarawakDuring the upcoming fourth sessionfrom 2-13 February 2009, the HumanRights Council is scheduled toexamine the human rights situationin Malaysia under the UniversalPeriodic Review.On 19 November 2008, Malaysiasubmitted its national report to theHuman Rights Council. Malaysia’snational report comprising 114paragraphs in VI Parts, amongothers, summarizes Malaysia’sefforts for promotion <strong>and</strong> protectionof human rights; its achievements,best practices, challenges, constraints<strong>and</strong> national priorities; <strong>and</strong> capacitybuilding.Various non-governmentalorganizations – national, regional<strong>and</strong> inter-national – submittedstakeholders’ submission.In order to bring out the exact situationof human rights of the indigenouspeoples in Malaysia, it is pertinentto critically analyse Malaysia’snational report vis-à-vis variousstakeholders’ submissions, reports<strong>and</strong> the compilation prepared by theOffice of the High Commissioner forHuman rights.Summary of Malaysia’s nationalreport (on the rights of theindigenous people)In sub-part B (Challenges, constraints<strong>and</strong> national priorities) in Part IV ofits national report, Malaysia devoted11 paragraphs to highlight its effortsfor uplift of the indigenous peoples<strong>and</strong> minorities. Malaysia considerslifting indigenous groups frombackwardness through assimilationinto mainstream society as the mostSince Malaysia has not yetratified most of the keyinternational human rightsinstruments, it provides anopportunity to the WorkingGroup on UPR to effectivelyexamine the human rightssituation in Malaysiaincluding the situation of theindigenous peoples.significant challenge. Malaysia statesthat it has developed comprehensivepolicies <strong>and</strong> strategies to upliftthe status <strong>and</strong> quality of life ofthe indigenous community viasocioeconomic programmes aswell as through prioritising thepreservation of traditional culturalheritage of the indigenous peoples.It particularly highlighted theConstitution, the Aboriginal PeopleAct, 1954; the Department of OrangAsli Affairs, State Committee onPenan Affairs <strong>and</strong> various programsformulated <strong>and</strong> implemented underthe Committee are Penan VolunteerCorps, Service Centres, EducationAssistance, Health <strong>and</strong> MedicalServices <strong>and</strong> Agriculture ExtensionServices.On l<strong>and</strong> rights, Malaysia statesabout the gazetting of 2,128hectares of l<strong>and</strong> to the Penans asnative customary rights (NCR) bySarawak State Government in 1981<strong>and</strong> development of these areas forcommercial plantation for the benefitof 154 Penans. Malaysia’s nationalreport further states that a total of52,864 hectares of l<strong>and</strong> in the Baramdistrict was allocated to the seminomadicPenans for hunting <strong>and</strong>gathering purposes.OHCHR’s compilation of UNinformationExcept the Convention on theElimination of Discriminationagainst Women (CEDAW) <strong>and</strong> theConvention on the Rights of the Child(CRC), Malaysia has not ratifiedany of the major United Nationsconventions.Malaysia has neither issued anyst<strong>and</strong>ing invitation to any of theSpecial Rapporteurs nor agreedupon the requests by many SpecialRapporteurs to visit the country. Arequest by the Special Rapporteur onindigenous peoples has been pendingsince 2005.The UN Committee on the Rightsof the Child has recommendedthat Malaysia undertake steps toprevent <strong>and</strong> combat discriminatorydisparities against children belongingto vulnerable groups, including theOrang Asli, indigenous <strong>and</strong> minoritychildren living in Sabah <strong>and</strong> Sarawak<strong>and</strong> particularly in remote areas.On 14 January 2008, the SpecialRapporteur on the situation of humanrights <strong>and</strong> fundamental freedoms ofindigenous people <strong>and</strong> the SpecialRepresentative of the Secretary-General on the situation of humanrights defenders raised concerns

<strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights Quarterly articleVol. III : No. 4 • October-December 2008 9with the Government of Malaysiaon the death of an aboriginal leaderinvolved in anti-logging campaignsin the Upper Baram region.OHCHR’s summary of stakeholders’submissionsFrom various stakeholders’submissions, the Office of the HighCommissioner on Human Rights(OHCHR) summarized the followingissues with regard to indigenouspeople in Malaysia:“The Orang Asal, or indigenouspeoples, consist of more than80 ethno-linguistic groups,each with its own culture,language <strong>and</strong> territory, asindicated by the JaringanOrang Asal Semalaysia(JOAS). Collectively, the 4million indigenous peoplesare among the poorest<strong>and</strong> most marginalised.SUHAKAM noted that therights of indigenous peopleto customary l<strong>and</strong> shouldbe upheld; <strong>and</strong> existingstate legislations should bereviewed. SUHAKAM notedthat the Malaysian Court hasprogressively recognisedcustomary l<strong>and</strong> rights. BCMnoted that State Governmentshave cleared ancestral l<strong>and</strong><strong>and</strong>/or alienated l<strong>and</strong> occupiedor utilised by aborigines tothird parties (e.g. for logging,palm cultivation) <strong>and</strong> has onlyoffered to pay compensationfor loss of agriculturalproducts planted on such l<strong>and</strong>.According to BCM, the GOMhas found it difficult to extendto the aboriginal community theright to proper education <strong>and</strong>health services. 105 COMANGOalso indicated that there is alsoan ‘Islamisation policy’ thattargets the con<strong>version</strong> of theOrang Asli community.”For reasons best known, OHCHR,though it confirmed the receiptof the submission by AITPN, hasfailed to mention AITPN <strong>and</strong> inthis process has omitted a numberof critical issues, raised by AITPN,from the stakeholder’s summaryreport. AITPN summarises theconcerns with regard to the situationof indigenous peoples in Sabah <strong>and</strong>Sawarak.i. Preference for logging <strong>and</strong>plantations over cultivation inSabahIn southern part of Sabah, the Statehas given the l<strong>and</strong>s which lie withinthe Kalabakan Forest Reserve toseveral companies against therepeated appeals from the SerudungMurut of Kalabakan. Severalindigenous communities haveestablished settlements <strong>and</strong> farmsin forest reserves as more l<strong>and</strong>s arebeing taken for oil palm plantations.The process of demarcation <strong>and</strong>recognition of customary l<strong>and</strong>s isvery slow, while the alienation oflarge areas for plantations, logging<strong>and</strong> protected areas is rapid. TheNational Human Rights Commissionurged the government to consider theproblems faced by the villagers whohave been residing in the areas sincebefore it was gazetted as a ForestReserve. 1In recent years, the governmentrapidly exp<strong>and</strong>ed oil palm cultivationespecially in States of Sarawak <strong>and</strong>Sabah. At least 55-59 percent of oilpalm expansion between 1990 <strong>and</strong>2005 occurred at the cost of forests.The area of oil palm plantations morethan doubled to 3.6 million hectares<strong>and</strong> at least 1.04 million hectares wereconverted for the oilseed during theperiod. 2Further, Native Customary L<strong>and</strong>sare being converted to corporatemonocultures in Sarawak. TheSarawak’s L<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> SurveyDepartment signs away NCR l<strong>and</strong>sbefore communities give priorinformed consent. For example,a South Korean-Malaysian jointventure is about to set up a cassavaplantation on about 2,000 hectaresof Native Customary Rights (NCR)l<strong>and</strong> initially in Balut area in Julaudistrict. The State L<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> SurveyDepartment reportedly confirmed thel<strong>and</strong> status. The government statesthat the project will benefit the people<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>owners besides creating jobs<strong>and</strong> business opportunities, etc. 3As a result of Native CustomaryRights (NCR) being continuouslyeroded, on 20 February 2008, amemor<strong>and</strong>um containing l<strong>and</strong> claimsfrom 32,352 natives over a collectivearea of 339,984 acres from 18 districtsin Sabah was submitted to Head ofState Tun Ahmadshah Abdullah<strong>and</strong> Chief Minister Datuk Seri MusaAman. 4ii. Targeting the Penans of SarawakThe conditions of the indigenousPenans in Sarawak State remaineddeplorable. In July 2007, theSUHAKAM following a fact-findingmission issued statement identifyingseven key areas requiring “drasticimprovement” by the governmentin order to improve the situation ofthe Penans. The SUHAKAM listedthe following concerns – l<strong>and</strong> rights;Environmental Impact Assessment(EIA) reports; poverty; personalidentification documents; education;health <strong>and</strong> the duty of the SarawakState government to protect therights of the Penans. The SUHAKAMstressed the need to amend theSarawak L<strong>and</strong> Code of 1958 as theCode has no provision on the rightsof the Penans to l<strong>and</strong> ownership. 5Certifying the extinction process:In 2001, the Malysian TimberCertification Council (MTCC) started

10<strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights Quarterly articleVol. III : No. 4 • October-December 2008a dubious method of legalizing itsillegal trade of timber by issuing“certificates” in the name ofpromoting environmentally soundlogging practices. The MTCC issuestwo types of certificates - Certificatefor Forest Management <strong>and</strong>Certificate for Chain-of-Custody. TheCertificate for Forest Managementcertifies that the Forest ManagementUnits (FMU) is sustainably managed<strong>and</strong> that timber was harvestedlegally. The Certificate for Chainof-Custodyassures the buyers thattimber products originated fromMTCC-certified FMUs. MTTC statesthat participation <strong>and</strong> consent oflocal communities, particularlyforest-dwelling indigenous people,is a key criterion for issuing of such“certificates”. 6However, since 2001, the <strong>Network</strong>of <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>and</strong> Non-Governmental Organisations onForest Issues (JOANGOHutan)withdrew from talks with thegovernment on certificationprocess. The organisation heldthat the scheme is “only concernedwith the sustainability of timberproduction <strong>and</strong> not the socialculturalsustainability of indigenouslivelihoods”. Like elsewhere,participation of indigenous peoplesis tokenism at its best. 7In January 2007, the Sarawakauthorities prevented the indigenousleaders from meeting an officialdelegation of European Unionwhich visited Sarawak as part ofthe negotiations between the EU<strong>and</strong> Malaysia to reach a “VoluntaryPartnership Agreement” to controlillegal logging <strong>and</strong> work towardssustainable forest management inMalaysia. 8The socalled certification processby the MTCC has been allowing theillegal loggers to flout the sustainableforestry practices <strong>and</strong> indigenouspeoples’ rights over their l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong>resources. The MTCC has reportedlycertified 4.73 million hectares ofPermanent Forest Reserves (PFR)that include eight forest managementunits (FMU) in the peninsula <strong>and</strong>the Selaan-Linau FMU in Sarawak.The practice is therefore proving tobe disastrous for the survival of theindigenous peoples who are largelydependent on forests produce. 9Manipulating EnvironmentalImpact AssessmentEnvironment Impact Assessmentsfor projects are often manipulatedby the authorities. In the Belagain Sarawak, the EnvironmentalImpact Assessment (EIA) done byJB Agriculture Management Servicesfor an oil palm <strong>and</strong> forest plantationtotally overlook the presence of thePenans by saying that there wasno evidence of human settlementsin Ulu Belaga forests. However,the Malaysian Human RightsCommission (SUHAKAM) followinga fact-finding mission to Sarawak inSeptember 2006 found contradictions<strong>and</strong> inconsistencies in the EIA onShin Yang Forest Plantation whichstretches between Batang Belaga<strong>and</strong> Sungai Murum. The EIA ofthe plantation scheme erroneouslydeclared that there is no humansettlement in the 155,930ha projectarea. Earlier, in 1999, Shin Yang hadobtained a 60-year Licence for PlantedForest. The project is divided into 80%forest plantation <strong>and</strong> 20% oil palm.Suhakam which released its report‘Penan in Ulu Belaga: Right to L<strong>and</strong><strong>and</strong> Socio-Economic Development’in August 2007 revealed that 19% ofthe Penan population of 15,500 residein Ulu Belaga, with 20 settlements inthe disputed region. 10Killing as the responseThose who oppose logging weretargeted. Many Penans have beenarrested <strong>and</strong> jailed for their actions.In December 2007, a village chieftainidentified as Kelesau Naan (70) wasfound dead in the jungles of Borneoin Sarawak state. Some of his boneswere reportedly fractured indicatingthat he had been assaulted. Hedisappeared on 23 October 2007while checking an animal trap nearthe remote village of Long Kerongin eastern Sarawak State. KelesauNaan has been a key figure in antiloggingefforts by the Penans. 11 Manysupporting activists who carriedout fact-finding missions or spokeout against atrocities perpetrated bylogging companies, police, etc werebanned from entering Sarawak. 12On 28 January 2008, an Iban villagechief <strong>and</strong> two others identified asTuai Rumah Taman Anak Embat(55), Robert Anak Gickson Sawing(23) <strong>and</strong> Alu Anak Embat (58) werearrested for setting up a blockadeto stop encroachment by plantationcompany, Saradu Plantation Sdn Bhdfor logging activities into their NativeCustomary Rights (NCR) l<strong>and</strong> in UluBalingian. 13iii. Displacement due to Bakun Damin SarawakIn late 2007, the government ofMalaysia decided to resume thecontroversial Bakun Hydro ElectricProject in Sarawak to its originaldesign to generate 2,400 megawattsof electricity power. 14 The Dam hasalready destroyed 23,000 hectares ofvirgin rainforest <strong>and</strong> displaced 9,000indigenous people. The communitiesclaimed that the survey conducted onthe ground was not properly carriedout. On 9 August 2007, AustraliabasedRio Tinto Aluminium signeda deal with Malaysian conglomerateCahya Mata Sarawak for a jointstudy to build a US$ 2 billion smelterin Similajau near Bintulu, 80 kminl<strong>and</strong> from the Bakun Dam. 15 Theindigenous people were strugglingto survive on resettlement sites due

<strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights Quarterly articleVol. III : No. 4 • October-December 2008 11to unemployment <strong>and</strong> hunger. Theindigenous people displaced by thedam project claimed that they havenot been properly resettled <strong>and</strong>adequately compensated. However,the State government has deniedthese <strong>and</strong> claimed that only the oldergeneration had reservations aboutthe resettlement program. 16(Footnotes)1. The <strong>Indigenous</strong> World 2008, InternationalWork Group for <strong>Indigenous</strong> Affairs,Copenhagen2. Half of oil palm expansion in Malaysia,Indonesia occurs at expense of forests,Mongabay.com, 20 May 2008, http://news.mongabay.com/2008/0520-palm_oil.html3. Biofuels from cassava plantation in Sarawak:new corporate monoculture planned onNCR l<strong>and</strong>s without prior informed consentof indigenous communities, availableat: http://borneoproject.org/article.php?id=6714. Memo on l<strong>and</strong> claims submitted, The DailyExpress, 21 February 20085. The <strong>Indigenous</strong> World 2008, InternationalWork Group for <strong>Indigenous</strong> Affairs,Copenhagen6. Malaysia: Certifying extinction ofindigenous peoples, <strong>Indigenous</strong> RightsQuarterly -Vol. II: No. 01,Jan-March, 2007,AITPN, available at: http://www.aitpn.org/IRQ/vol-II/issue-1.htm7. Ibid8. Ibid9. Ibid10. Overlooked minority, The Star.com,30 October 2007, available at: http://thestar.com.my/lifestyle/story.asp?file=/2007/10/30/lifefocus/20071030094513&sec=lifefocus11. Borneo tribesman who fought loggingfound dead in Malaysia, family says, TheBangkok Post, 3 January 200812. The <strong>Indigenous</strong> World 2008, InternationalWork Group for <strong>Indigenous</strong> Affairs,Copenhagen13. Ulu Balingian Ibans held for settingblockade, The Rengah Sarawak, 29 January200814. Malaysia Government should respond tothe Report of World Commission on Dams,The Rengah Sarawak, 7 January 200815. <strong>Indigenous</strong> World 2008 <strong>and</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong>World 2007, The <strong>Indigenous</strong> World 2008,International Work Group for <strong>Indigenous</strong>Affairs, Copenhagen16. IWGIA, available at: http://www.iwgia.org/sw18360.aspNew Delhi Guidelines on theEstablishment of National Institutionson the Rights of <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>,IntroductionNew Delhi,October 18-19, 2008Regional Conference on theRole of the National Institutions on theRights of <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>At the Regional Conference on theRole of the National Institutions on theRights of <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> 1 heldin New Delhi, on 18-19 October 2008,the representatives of indigenouspeoples participating in theconference unanimously welcomedthe contributions made by UN SpecialRapportuer on the situation of humanrights <strong>and</strong> fundamental freedomsof indigenous peoples, Prof JamesAnaya; Chairman of the NationalCommission on <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>of the Philippines <strong>and</strong> member of theUnited Nations Permanent Forumon <strong>Indigenous</strong> Issues, Mr Eugenio AInsigne; Member of the GoverningCouncil of the National Foundationfor Development of <strong>Indigenous</strong>Nationalities of Nepal, Mr ArjunLimbu; Member of the NationalCommission for Protection of ChildRights of India, Ms Dipa Dixit;Representative of the Delegation ofthe European Commission to India,Mr Hans Schoof; <strong>and</strong> former SpecialRapporteur on the right to adequatehousing, Mr Miloon Kothari.The representatives of indigenouspeoples participating in theconference adopted the followingguidelines which they underst<strong>and</strong>to reflect the minimum st<strong>and</strong>ardsfor the establishment of anyNational Institutions on theRights of <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>(NIRIPs). These guidelines aredesigned to be of use to all whoare concerned with promotion<strong>and</strong> protection of the rights ofindigenous peoples, in particular, thegovernments <strong>and</strong> the United Nationsbodies <strong>and</strong> agencies.New Delhi Guidelines on theestablishment of NationalInstitutions on the Rights of<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>, New Delhi,October 18-19, 2008I. The significance of NationalInstitutions on the Rights of<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>1. Since the adoption of theUnited Nations Paris Principleson National Human RightsInstitutions in 1991, a numberof National Human RightsInstitutions have beenestablished by the governmentsacross the world.2. A number of NationalInstitutions on the Rightsof <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> havealso been established by thegovernments across the world.

12<strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights Quarterly reportVol. III : No. 4 • October-December 20083. The establishment of the NationalInstitutions on the Rights of<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> reflects apolicy shift of the concernedgovernments from assimilationof indigenous peoples torecognition <strong>and</strong> preservationof the distinctiveness of theindigenous peoples <strong>and</strong> therights of indigenous peoplesto all human rights <strong>and</strong>fundamental freedoms.4. There have also been significantlegal developments atinternational level enhancingthe rights of indigenous peoplesincluding the UN Declarationon the Rights of <strong>Indigenous</strong><strong>Peoples</strong>, ILO Convention No169 concerning <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>Tribal</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> in IndependentCountries <strong>and</strong> a number ofinternational instruments whichrefer to indigenous peoples.5. It is now undisputed that allhuman rights are indivisible,interdependent, interrelated<strong>and</strong> of equal importancefor human dignity <strong>and</strong> thatindigenous peoples are equallyentitled to all these rights.6. It is recognized that theNational Institutions on theRights of <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>have an important <strong>and</strong> crucialrole to play for recognition,promotion, protection <strong>and</strong>implementation of the rights ofindigenous peoples includingthe UN Declaration on theRights of <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>.7. The United Nations bodiesespecially those relating toindigenous peoples like SpecialRapporteur on the situation ofhuman rights <strong>and</strong> fundamentalfreedoms of indigenouspeople, Permanent Forumon <strong>Indigenous</strong> Issues <strong>and</strong> theExpert Mechanism on the Rightsof <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> of the UNHuman Rights Council have arole to play for promotion <strong>and</strong>establishment of the NationalInstitutions on the Rights of<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>.8. The UN agencies shouldencourage States <strong>and</strong> includethe establishment of theNational Institutions on theRights of <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>in their technical cooperationprogrammes.Chapter I: Constitution of aNational Institution on the Rightsof <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>1. The National Institutionson the Rights of <strong>Indigenous</strong><strong>Peoples</strong> (NIRIPs) should beconstitutional bodies m<strong>and</strong>atedto protect, promote <strong>and</strong> defendhuman rights, fundamentalfreedoms <strong>and</strong> other rights <strong>and</strong>interests of the indigenouspeoples with due regard to theirbeliefs, customs, traditions <strong>and</strong>institutions <strong>and</strong> shall exercisethe powers conferred upon, <strong>and</strong>perform the functions assignedto it.2. The NIRIPs shall reflectplurality <strong>and</strong> representation ofindigenous communities.3. The Chairperson, members <strong>and</strong>Chief Executive Officer shall beindigenous persons.4. The NIRIPs shall have officesin the territories of indigenouspeoples.1. Criteria /Qualifications1. The Chief Commissioner <strong>and</strong>the Commissioners must haveexperience <strong>and</strong> expertise onindigenous peoples’ issuesincluding the experienceworking with an indigenouscommunity for substantialperiod of time <strong>and</strong>/or anygovernment agency involved inindigenous peoples’ issues, theability, integrity <strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ingfor selflessness to the causeof justice for the indigenouspeoples.2. The composition of the NIRIPsshall reflect the diversityof the indigenous peoplesincluding gender, ethnicity <strong>and</strong>geographical regions.2. Procedure of appointment ofmembersThe members of the NIRIPs shall beappointed by the head of the State onthe recommendation of a committeecomprising of the representativeof the government, leader/s of theopposition in the National Parliament<strong>and</strong> representatives of indigenouspeoples.The procedures of appointment shallbe made public through issuance ofa notification through publicationin all national newspapers <strong>and</strong>other communication systems likeinternet inviting recommendationsfrom indigenous communities forappointment <strong>and</strong> filling up the vacantposts of members of the NIRIPs aswell as inviting comments from theindigenous peoples (individuals <strong>and</strong>organizations) on c<strong>and</strong>idature of allthe nominees; <strong>and</strong> further the detailsof the nominees including names,address, educational qualifications,work experience etc. beforeappointment <strong>and</strong> the informationpertaining to all the nominees shallbe made public.3. Resignation <strong>and</strong> removal ofmembers1. The members of NIRIPs may,by notice in writing under his/her h<strong>and</strong> addressed to the Headof State, resign his/her office.2. The members of NIRIPs shallonly be removed from his/her office by the initiativeof appropriate authority orupon recommendation by anyindigenous community on theground of proven misbehaviour

<strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights Quarterly reportVol. III : No. 4 • October-December 2008 13or incapacity after the apex court,on reference being made to it bythe appropriate authority, has,on inquiry held in accordancewith the procedure prescribedin that behalf by the apex court,reported that the members ofthe NIRIPs, as the case may be,ought on any such ground to beremoved.3. The Head of State on the adviceof the appropriate authoritymay by order remove membersof NIRIPs as the case may be;(a) is adjudged an insolvent;or(b) engages during his/herterm of office in any paidemployment outside theduties of his/her office; or(c) is unfit to continue in officeby reason of infirmity ofmind or body; or(d) is of unsound mind <strong>and</strong>st<strong>and</strong>s so declared by acompetent court; or(e) is convicted <strong>and</strong> sentencedto imprisonment for anoffence involves moralturpitude.4. Procedure to be regulated by theNIRIPsThe NIRIPs shall regulate its ownRules of Procedure.5. Officers <strong>and</strong> other staff of theNIRIPs1. The NIRIPs shall be madeavailable:(a) an officer who shall bean indigenous person<strong>and</strong> serve as the ChiefExecutive Officer; <strong>and</strong>(b) such investigative staff<strong>and</strong> officers as may benecessary for the efficientperformance of thefunctions of the NIRIPs.2. The NIRIPs may appoint suchother administrative, technical<strong>and</strong> scientific staff as it mayconsider necessary.6. Offices <strong>and</strong> departments of theNIRIPsThe NIRIPs, among others, shall havethe following offices which shall beheaded by indigenous persons <strong>and</strong> beresponsible for the implementation ofthe policies hereinafter provided:(a)Policy, Planning <strong>and</strong> Research<strong>and</strong> Advocacy office will beresponsible for formulationof appropriate policies <strong>and</strong>programs for indigenouspeoples such as, but notlimited to, the developmentof a Five-Year Master Plan forthe indigenous peoples. TheNIRIPs shall endeavor to assessthe plans <strong>and</strong> make necessaryrectifications in accordance withthe changing situations. TheOffice shall also undertake thedocumentation of customarylaw <strong>and</strong> shall establish <strong>and</strong>maintain a Research Center thatwould serve as a depository ofethnographic information formonitoring, evaluation <strong>and</strong>policy formulation. It shall assistthe legislative branch of thegovernment in the formulationof appropriate legislation onindigenous peoples(b) Education <strong>and</strong> CultureOffice will ensure effectiveimplementation of theeducation, cultural <strong>and</strong> healthrights of the indigenous peoples.It shall assist, promote <strong>and</strong>support community schools,both formal <strong>and</strong> non-formal,for the benefit of the indigenouscommunities, especially in areaswhere existing educationalfacilities are not accessible tomembers of the indigenousgroups. It shall administer allscholarship programs <strong>and</strong> othereducational rights intendedfor indigenous people’sbeneficiaries in coordinationwith the Ministry of Education,Culture <strong>and</strong> Sports <strong>and</strong> otherrelated agencies. It shall alsoundertake special programsto preserve <strong>and</strong> promote thelanguages <strong>and</strong> traditionalknowledge of the indigenouspeoples.(c) Office on Socio-EconomicServices <strong>and</strong> Special Concernswill coordinate with pertinentgovernment agenciesspecially charged with theimplementation of variousbasic socio-economic services,policies, plans <strong>and</strong> programsaffecting the indigenous peoplesto ensure that the same areproperly <strong>and</strong> directly enjoyedby the indigenous peoples. Itshall also be responsible forsuch other functions as theNIRIPs may deem appropriate<strong>and</strong> necessary.(d)(e)(f)Women Rights Cell which,among others, shall design <strong>and</strong>implement the programmesof the NIRIPs pertaining toindigenous women.Youth <strong>and</strong> Child Rights Cellwhich, among others, shalldesign <strong>and</strong> implement theprogrammes of the NIRIPspertaining to indigenous youths<strong>and</strong> children.Office of Empowerment <strong>and</strong>Human Rights will ensure theenjoyment of the human rights<strong>and</strong> fundamental freedomsby the indigenous peoples. Itshall, among others, undertakecapacity building programmes,participation of indigenouspeoples at all levels of decisionmaking<strong>and</strong> intervene againstviolations of the rights of

14<strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights Quarterly reportVol. III : No. 4 • October-December 2008(g)indigenous peoples.Administrative Office, amongothers, shall provide the NIRIPswith economic, efficient <strong>and</strong>effective services pertainingto personnel, finance, records,equipment, security, supplies<strong>and</strong> related services.(h) Legal Affairs Office shall,among others, advice theNIRIPs on all legal mattersconcerning indigenous peoples<strong>and</strong> providing legal assistanceto indigenous peoples inlitigations.(i)Other Offices - The NIRIPsshall have the power to createadditional offices or regionaloffices in all developmentregions or wherever it maydeem necessary.7. Consultative AdvisoryCommittee1. It shall be the duty of theNational Institutions on theRights of <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>to establish a ConsultativeAdvisory Committee ofindigenous peoples which shallhave the m<strong>and</strong>ate to:(i) advise the NIRIPs onmatters relating to theproblems, aspirations <strong>and</strong>interests of the indigenouspeoples; <strong>and</strong>(ii) ensure indigenouspeoples participationfor appointment of themembers of the NIRIPs;2. The Consultative AdvisoryCommittee shall ensureequitable representationof gender, ethnicity <strong>and</strong>geographical diversity.Chapter II: Functions <strong>and</strong> Powers ofthe NIRIPs8. Functions <strong>and</strong> powers of theNIRIPs1. The National Institutions on theRights of <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong>shall be informed <strong>and</strong> consultedby the government on allmajor policy matters affectingindigenous peoples.2. The NIRIPs shall have quasijudicial<strong>and</strong> quasi-legislativepowers <strong>and</strong> functions <strong>and</strong>the duty of the NIRIPs shallinclude:(a) To serve as the primarygovernment agencythrough which indigenouspeoples can seekgovernment assistance<strong>and</strong> as the primary agencymedium, through whichsuch assistance may beextended;(b) To monitor, review, <strong>and</strong>assess the conditionsof indigenous peoplesincluding existing laws <strong>and</strong>policies pertinent thereto<strong>and</strong> to propose relevantlaws <strong>and</strong> policies toensure their proportionateparticipation in nationaldevelopment;(c) To coordinate, formulate<strong>and</strong> implement policies,plans, programs <strong>and</strong>projects of the governmentfor the economic, social<strong>and</strong> cultural developmentof the indigenous peoples<strong>and</strong> monitoring theimplementation thereof;(d) To request <strong>and</strong> engagethe services <strong>and</strong> supportof experts from otheragencies of governmentor employ private experts<strong>and</strong> consultants as may berequired in the pursuit ofits objectives;(e) To inquire into specificcomplaints, on receiptof complaints or suomotu, with respect to theviolations of the rights<strong>and</strong> safeguards of theindigenous peoples;(f) To receive complaints<strong>and</strong>/or take suo motuaction <strong>and</strong> inquire intonon-implementation of theservices provided by thegovernment <strong>and</strong> compelaction from appropriateagency;(g) To participate <strong>and</strong> adviseon the planning processof socio-economicdevelopment of theindigenous peoples <strong>and</strong>to evaluate the progress oftheir development;(h) To study <strong>and</strong> makerecommendations forsustainable developmentof indigenous peoples;(i) To discharge such otherfunctions in relation tothe protection, welfare<strong>and</strong> development <strong>and</strong>advancement of theindigenous peoples;(j) To discharge such otherfunctions in relation tothe protection, welfare<strong>and</strong> development <strong>and</strong>advancement of theindigenous peoples as thecase may be, subject tothe provisions of any lawmade by Parliament;(k) To convene periodicconventions or assembliesof indigenous peoples toreview, assess as well aspropose policies or plans;(l) To update the scheduledlist of indigenous peoplesthrough identification<strong>and</strong> recognition ofthe unidentified <strong>and</strong>unrecognized ones;(m) To recognize, promote <strong>and</strong>protect traditional wisdom<strong>and</strong> knowledge of theindigenous peoples <strong>and</strong>prevent transfer of such

<strong>Indigenous</strong> Rights Quarterly reportVol. III : No. 4 • October-December 2008 15knowledge <strong>and</strong> wisdom tonon-indigenous peoples/areas without benefitsharing <strong>and</strong> ensuring fullrespect for the right tofree, prior <strong>and</strong> informedconsent;(n) To act as the regulatingagency for implementationof programmes or projectsby non-governmentalorganizations <strong>and</strong> theprivate sector;(o) To promulgate thenecessary rules <strong>and</strong>regulations for theimplementation of therights of indigenouspeoples;(p) To secure the assistanceof the governmentdepartments to enforce theorders of the NIRIPs; <strong>and</strong>(q) To constitute one ormore Sub-Committeesfor purposes of research,investigation, review<strong>and</strong> monitoring of social,economic, cultural <strong>and</strong>civil <strong>and</strong> political rights ofthe indigenous peoples.9. Powers relating to inquiries1. The NIRIPs shall, whileinquiring into any complainthave all the powers of a civilor criminal court whicheverapplicable in respect of thefollowing matters, namely:-(a) summoning <strong>and</strong> enforcingthe attendance of anyperson <strong>and</strong> examining himon oath;(b) requiring the discovery<strong>and</strong> production of anydocuments;(c) receiving evidence onaffidavits;(d) requisitioning any publicrecord or copy thereoffrom any court or office;(e) issuing summons for theexamination of witnesses<strong>and</strong> documents; <strong>and</strong>(f) any other matter whichmay be prescribed by theparliament.2. The NIRIPs shall have powerto require any person, subjectto any privilege which may beclaimed by that person underany law for the time being inforce, to furnish informationon such points or matters as, inthe opinion of the NIRIPs, maybe useful for, or relevant to, thesubject matter of the inquiry <strong>and</strong>any person so required shall bedeemed to be legally bound tofurnish such information aslegally provided.3. The NIRIPs or any other officerspecially authorised in thisbehalf by the NIRIPs may enterany building or place where theNIRIPs has reason to believethat any document relating tothe subject matter of the inquirymay be found, <strong>and</strong> may seizeany such document or takeextracts or copies there fromsubject as provided under law.4. Every proceeding before theNIRIPs shall be deemed to bea judicial proceeding <strong>and</strong> thedecisions of the NIRIPs shall beappealable only before the apexcourt of the country.Chapter III: Procedures10. Inquiry into complaints1. The NIRIPs while investigatinginto non-implementation ofsafeguards available to theindigenous peoples under theConstitution or any law forthe time being in force mayinitiate an inquiry by its owninvestigation department orother agency of the governmentas the NIRIPs deems fit toinquire into the complaintsof violations of the rights ofindigenous peoples;2. Where the inquiry disclosesviolation of rights of theindigenous peoples ornegligence in the preventionof violation of the rights bya public servant, the NIRIPsmay take appropriate actions/measures as may deem fitgainst the concerned person orpersons;11. Annual <strong>and</strong> special reports of theNIRIPs1. The NIRIPs shall submit anannual report to the Parliament<strong>and</strong> may at any time submitspecial reports on any matterwhich, in its opinion, is ofsuch urgency or importancethat it should not be deferredtill submission of the annualreport.2. The Government shall submita memor<strong>and</strong>um of actiontaken or proposed to be takenon the recommendations ofthe NIRIPs <strong>and</strong> the reasonsfor non-acceptance of therecommendations, if any.Chapter IV: Finance12. Financial autonomyThe National Institutions on theRights of <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> shallhave financial independence:1. The Government shall afterdue appropriation made byParliament by law in this behalf,pay by way of grants suchsums of money as the NIRIPsmay present in a budget to theGovernment annually.2. The NIRIPs can directly receiveadditional funds from anysource as donation, assistance,grants etc.(Footnotes)1. The Regional Conference was organisedby <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Tribal</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong><strong>Network</strong>.