text final july-sep-10.pmd - Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi ...

text final july-sep-10.pmd - Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi ...

text final july-sep-10.pmd - Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

A Journal of<strong>Mahatma</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong><strong>Antarrashtriya</strong><strong>Hindi</strong> VishwavidyalayaL A N G U A G EDISCOURSEW R I T I N GVolume 4July-September 2010EditorMamta KaliaKku 'kkafr eS=khPublished by<strong>Mahatma</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong> International <strong>Hindi</strong> University

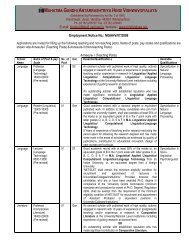

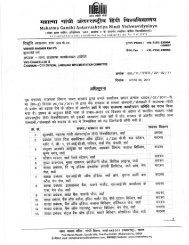

<strong>Hindi</strong> : Language, Discourse, WritingA Quarterly Journal of <strong>Mahatma</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong> <strong>Antarrashtriya</strong><strong>Hindi</strong> VishwavidyalayaVolume 4 Number 7 July-September 2010R.N.I. No. DELENG 11726/29/1/99-Tc© <strong>Mahatma</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong> <strong>Antarrashtriya</strong> <strong>Hindi</strong> VishwavidyalayaNo Material from this journal should be reproduced elsewhere withoutthe permission of the publishers.The publishers or the editors need not necessarily agree with theviews expressed in the contributions to the journal.Editor : Mamta KaliaEditorial Assistant : Madhu SaxenaEditorial Office :C-60, Shivalik, I Floor, Malaviya NagarNew Delhi-110 017Phone : 41613875Sale & Distribution Office :Publication Department,<strong>Mahatma</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong> <strong>Antarrashtriya</strong><strong>Hindi</strong> VishwavidyalayaPost Manas Mandir, <strong>Gandhi</strong> Hills, Wardha-442001 (Maharashtra) IndiaSubscription Rates :Single Issue : Rs. 100/-Annual - Individual : Rs. 400/- Institutions : Rs. 600/-Overseas : Seamail : Single Issue : $ 20 Annual : $ 60Airmail : Single Issue : $ 25 Annual : $ 75Published By :<strong>Mahatma</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong> <strong>Antarrashtriya</strong> <strong>Hindi</strong> Vishwavidyalaya, WardhaAll enquiries regarding subscription should be directed to the<strong>Mahatma</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong> <strong>Antarrashtriya</strong> <strong>Hindi</strong> Vishwavidyalaya, WardhaPrinted at :Ruchika Printers, Delhi-110 032Phone : 92127962562 :: July-September 2010

L A N G U A G EDISCOURSEW R I T I N GJuly-September 2010ContentsHeritageCaptain Rashid Upendra Nath Ashk 7Dachi Upendra Nath Ashk 18MemoirThe Graceful Charmer, Ashk Rajinder Singh Bedi 25Qissa Khan :A Coloureful Storyteller Named Ashk Phanishwar Nath Renu 3 7Muktibodh Harishankar Parsai 45PoetryTen Poems Badri Narayan 5 1Discourse<strong>Hindi</strong> Literary Journalism SinceBhartendu Age Bharat Bharadwaj 59Dalit Saint Poets of Bhakti Movement :Pride and Prejudice Subhash Sharma 69Some Great Indian Literary Theorists Ravi Nandan Sinha 86July-September 2010 :: 3

Short StoryThe Bamboo Kashinath Singh 94The Brats Manisha Kulshreshtha 9 7Saaz Nasaaz Manoj Rupra 108Pages From A NovelAnitya : Thoughts in Jail Mridula Garg 134FilmsMeena Kumari Kanan Jhingan 1 4 7Book ReviewAbbu Ne Kaha Tha :Unpacking Swag of Pangs Rohini Agrawal 1554 :: July-September 2010

Editor's NoteOn a recent visit to Goa, I had the occasion to be present at the conferringof Jnanpith award upon Konkani author and national activist Ravindra Kelekar.It was an event in which the Government of Goa not only took activepart but mobilised the entire literati to participate in it. Jnanpith laureateRavindra Kelekar was not in the best of health that day. He remainedseated during the award function. However the audience of 2000 strongaccorded him a standing ovation for full five minutes. Lovers of Konkanilanguage and literature thronged the auditorium to have a glimpse of theirvenerated writer.The <strong>Hindi</strong> world could learn a lesson or two from this experience. <strong>Hindi</strong>has a great number of writers and scholars who have given a lifetimeof service to the enrichment of the language. In <strong>Hindi</strong>, books are publishedin bulk and marketed all over the world. Considering the vast numberof people who speak <strong>Hindi</strong> and no less who read it, the returns of thisharvest to the writer are meagre. Even worse is the output in terms ofsocial status. This history repeats itself from Nirala to Nagarjun and fromPremchand to Amarkant.Upendranath Ashk whose centenary occurs this year was one brave authorwho broke free from the clutches of commercial injustice to set up hisown publishing house in 1949. His writer wife Kaushalya Ashk took overthe reins of Neelabh Prakashan and relieved him of all humdrum businesschores. Except for a few short term jobs, Ashkji remained a freelancerthroughout his life. He formed an ideal family with an understanding, sensitivewife and an intellectual son Neelabh. The three shared great vibrationsand ruled an otherwise difficult literary town– Allahabad. Ashkji’s life wasnot luxurious but self dependent.We carry two of his famous short stories in our heritage column andtwo memoirs on him by his contemporaries. His son Neelabh has obligedus by giving us this archive material. It is noteworthy that the level ofJuly-September 2010 :: 5

mutual appreciation among writers was exemplary fifty years ago. Bedi andRenu were writers of a different genre but they warmly acknowledged Ashkji’sindividuality. This type of tolerance is totally missing in present times.Other short stories by Kashinath Singh, Manoj Rupra and Manisha Kulshreshthaare very significant for their content and style.Badri Narayan is known for his simplicity of diction and richness of content.We bring you some of his poems. In discourse Bharat Bharadwaj haspainstakingly chalked out the history of <strong>Hindi</strong> literary journalism. We alsohave a candid study of dalit saint poets by Subhash Sharma and an analysisof poetic theory by Ravinandan Sinha. Our readers are well familiar withboth of them.<strong>Hindi</strong> has a rich treasure chest of memoirs and we bring you one byHarishankar Parsai. He recalls Muktibodh in all his shades of personality.Mridula Garg’s novel Anitya has been translated into English recently andwe present one chapter from the same. Chandrakanta’s collection of shortstories ‘abbu ne kaha tha’ is reviewed by hindi literary critic Rohini Agrawal.In films column, Kanan Jhingan’s portrayal of Meena Kumari speaks volumesabout that superb suffering artiste.Friends, you can well assess that the number of women writing in hindiis no less than that of men, in fact it may be greater. But this isincidental. After all gender is not important in literature. Women writerscan not wear it like a badge or a banner. Every writer has to face thetest of time.6 :: July-September 2010

HeritageCAPTAIN RASHIDUpendra Nath AshkTranslatedJai Ratanby“I was thinking of Hanif. Why don’t you find a place for himin your new scheme?”Captain Rashid had his tunic on and was pacing the roomas usual, while buttoning it. At the same time he was feverishlythinking of giving a face-lift to his weekly. His imagination ranriot. He had already appointed new, able and experienced subeditors;had asked the press to cast new type-faces; had prevailedupon the headquarters to supply better quality news stock; hadincreased the number of pictorial pages and during his editorship,the paper had undergone a vast change and had become far moreuseful for the armed forces...His wife’s words fell dimly upon his ears as if he were ina state of somnambulism. He knit his brows and turning round,he looked at her in surprise.She was sitting on the edge of her bed, preparing a cup oftea for him. Capt. Rashid’s office started at nine, but he hadmade it a point to be in the office fifteen minutes before time.It was his belief that an officer should be at his desk beforethe clerks arrived. He would set the alarm clock for an earlyhour and the servant had instruction to bring the morning teain the bed room, so that he would be ready to leave for officeby 8:15.As she stirred the sugar in the cup, a faint smile played acrossher face, like the first reluctant streak of an autumn dawn, andJuly-September 2010 :: 7

her face gradually reddened with theordeal of a request. She looked at herhusband from the corner of her eyes.Stirring the tea, she repeated her request.“I was telling you about Hanif...”“You are a fool. “Capt. Rashid snapped.There was a scowl on his face. Pickingup the cup, he again started pacing theroom.His wife watched him silently as hestrode to the other end of the room.Her gaze sliding down his fast baldinghead, the back of which ended inpronounced bulge, took in his thin neckand rounded shoulders and came to reston his feet. She realised that his gaithad undergone a great change. For thatmatter, she had noticed the change sincethe day he had been appointed to hisnew position. His thin neck was alwaysstiff as if he had pulled a muscle. Hewalked on his toes and on reaching thewall he pirouetted on his toes, like atop taking a sharp spin.Not only his gait, even his mannershad undergone a change. His gaze, whichpreviously was always subdued and borea puzzled and helpless expression, hadnow changed into a bold stare, brimmingwith confidence. While talking, he wouldsmile ironically, thinking the other personto be a damned fool or curl up hislips, as if the other fellow was indulgingin some silly prattle, unworthy of hisnotice.For sometime Mrs. Rashid watchedher husband sipping tea and pacing upand down the room. She did not mindthe ‘title’ that her husband had bestowedupon her for asking him to fix up hercousin’s husband with a job under hiscontrol. When Rashid had donned themilitary uniform for the first time, hiselder brothers had laughed at him.“What’s the army coming to these days.”his eldest brother would say with a merrytwinkle in his eyes, “that even such prizespecimens have come to find a placein it”. The elder brother would recitea couplet saying:‘Seeing my photo said that impishbeauty.This cartoon is fit for a newspaper.’Their wives stuffed handkerchiefs intotheir mouths to keep them from burstinginto laughter and Mrs. Rashid hung herhead with embarrassment. This was thereason, that now her husband’s stiff neck,his short temper, his droll appearanceand irascible nature gave her a sort ofsatisfaction. She knew that his elderbrother felt sorry for having made himthe mark of his witticism and that theeldest brother felt awkward at this reedthinman having made the grade. Hadn’the lived up to his boast that withoutthe recommendation and help of his KhanBahadur father, he would come up inlife. Through his own ability andperseverance he had risen to the rankof capt. and been selected for thisimportant post. His words still rang inher ears: “I am the first Indian to bemade the Editor of this weekly. For the8 :: July-September 2010

past half century this position has beeninvariably held by Britishers alone.”Mrs. Rashid looked at her husbandwith great pride. He had finished hiscup and after putting it back on thetea-tray was now nibbling at a biscuit.She drained the cup in an empty glassand pouring the tea for a second cupbroached the topic again. “You knowhow much regard I have for Shamim.She’s a distant relation, no doubt, butI hold her dearer than a sister.”She paused. Capt. Rashid was stillpacing the room. She said again, “Auntieis worried about shamim. It’s now fouryears since she was married. She hastwo children. But Hanif Bhai is still withouta decent job.”She put a spoonful of sugar and halfa spoon of milk. Capt. Rashid continuedto walk. He knitted his eye-brows whichfurrowed his forehead and his gait becameheavy. His wife continued: “In theseexpensive times one cannot feed evenone mouth on sixty rupees a month.”She sighed. “And then Shamim has twochildren and father and mother to carefor.”She stirred the sugar. Capt. Rashidmade no reply. His lips twisted and thescowl on his face deepened. “Peoplewithout even the rudiments of Englishare these days earning a salary of Rs.200/-” she continued, without noticingher husband’s expression who stoodfacing the wall. “Hanif, as you know,has done his B.A. with Honours. Buthe is poor and lacks contacts to pullthe right strings.”Capt. Rashid could not hold backhis anger. ‘You foolish woman,’ he saidto himself, tantalised, ‘did I get whereI am through anybody’s help? Hard work,ability, honesty– these are the keys tosuccess. I have not made this schemeto give asylum to worthless creatureslike Hanif. I have no use for drones.I want diligent and experiencedjournalists, who know the ropes!’ Buthe did not say all this to her. He casta pitying glance at his silly wife, andlooked at the watch. It was going onto be eight. “I want journalists, not clerks,”he said shortly, and without touchingthe cup of tea, he strode out of theroom.Mrs. Rashid didn’t get up. She satstunned and although she had stirredthe sugar, she went on stirring the teaabsentmindedly.Capt. Rashid was the third and theyoungest son of a military contractor,whom the Government had honouredwith the title of Khan Bahadur. Incomparison with his two brothers, hewas not much to look at, but he hadan alert and agile mind. Although hewas no match to these two ‘bulls’ (who,he used to say, had fattened themselveson the ill-gotten wealth of their father)he was fired with the ambition ofoutstanding them in some other fieldof activity. That was the reason, whileJuly-September 2010 :: 9

his two brothers were busy squanderingtheir father’s money, earned throughlegitimate or illegitimate means, he hadput his heart and soul into acquiringan education. After completing his collegeeducation he went in for a course ofjournalism. He had hardly finished hiscourse when he was offered a commissionin the army. Although his father hada big hand in getting him this position,Capt. Rashid however, attributed hisachievement to his own talent anddiligence; he was fully convinced thathe was worthy of this position.The weekly journal, of which he hadbeen made the editor, was not one ofthose countless newspapers, which hadsprouted overnight like mushroomsduring the second World War. The paperhad been established about fifty yearsago and was intended for the armedforces engaged in fighting the tribalson the Afghan border. When Capt. Rashidtook over its editorship, it was beingpublished in several vernacularlanguages.The armed personnel do not haveaccess to the general run of newspapers.Hundreds of miles away from home theyhave to fight in jungles, difficult mountainterrain, forlorn deserts and isolatedpockets. Although even in those daysevery effort was being made to providewholesome diversion through games andrecreations to fill the leisure hours ofthese semi-literate soldiers, yet it wasfelt that they must have a newspaperof their own, which should help themto beguile the tedious hours which hangheavy on them after a full day’s ordeal;when their thoughts turn to their homes,when they pine to know about the welfareof their near and dear ones, the conditionof the land and the crops. The paperhad been started to fill this need. Inthe beginning, the newspaper wasconfined to a bare two sheets, and itseditorial staff limited to a few persons.Although the two world wars sawthe addition of number of translatorclerksto the journal, and its establishmentalso expanded considerably, yet its modeof editing was as hackneyed andstereotyped as that of the earliest days.The bulk of its material was suppliedby the Government InformationDepartment. The sub-editor and the typistbetween them vetted the <strong>text</strong>, whichwas then typed out and distributed tothe vernacular sections for translation.The vernacular sections were faithfulversions of the parent English edition.The gossip columns and tit-bits werefirst written in English and then translatedinto the various vernaculars, where thejokes failed to come off, and thetranslations, often made quaint reading.The English edition was actually intendedfor the Officers, so that they could makesure, that nothing objectionable orseditious was going into the vernaculareditions. Not a line was changed, noteven the captions, to suit the vernacular<strong>text</strong>s.As soon as Capt. Rashid came tothe helm and examined the paper with10 :: July-September 2010

the eyes of a professional journalist, hefrowned and curled his lips. “It’s a rag.”he said in disgust, flinging it down onthe table. Within a week he had drawnup a scheme to infuse new blood intoits degenerate body.The eye-brows at Headquarters wentup. Would the finance Departmentapprove Capt. Rashid’s scheme? Whatcould be wrong with a paper which hadstood the test of time for fifty years?To admit that there was something wrongwith the paper amounted to acceptingthe fact that Capt. Rashid’s predecessorshad been a pack of fools.Capt. Rashid had gone to theHeadquarters fully prepared to meet hisadversaries on their own ground. First,he patiently explained to them thesignificance of the newspaper. This paper,he said, was the only organ of its typefor the other ranks and could play animportant role in moulding their wayof thinking. Then he impressed uponthem that the soldier today was notthe same as his compatriot fifty yearsago. Today, he was politically consciousand sensitive to what was going on aroundhim. It was, therefore, necessary to showa greater degree of astuteness in framingthe policies of the paper so as to caterto his new requirements. He also ridiculedthe idea of entrusting the editing to pettyclerks, who were not only innocent ofthe rudiments of journalism, but alsoincompetent translators. He picked upthe Urdu edition and pointed out somehowlers.“I can look after the English editionmyself”, he said, “And the Urdu editiontoo. But what about the <strong>Hindi</strong>, Gurumukhi,Tamil, Telugu and Marathi editions? Arewe to leave them at the mercy of pettyclerks?”Capt. Rashid’s proposals wereaccepted. It was decided in the firstinstance to appoint Sub-editors for thefour vernacular editions at Rs.250/- amonth and also a Sub-editor for theEnglish edition.It was a deep winter morning.Although past eight, there was nosunshine, as if like the inhabitants ofthe surrounding bungalows, the sun wasalso reluctant to fling aside its quilt.In the sky’s slumberous eyes traces ofsleep still lingered. A cold wind blewscattering the dead leaves along the roadand the foot-paths. But the earth wasawake. In the bungalows, on both sidesof the road, eucalyptus, jamun, mango,silk-cotton and neem trees kissed thesky in their nude apology.But Capt. Rashid was oblivious ofthe indolence of the sky or theexhilaration of the earth. He was obsessedwith only one thought, how to changethe garb of his journal. In his mind’seye he was already seeing his journalshuffling off its skin like a snake. Withhis hands thrust in his trouser pocketshe was mentally interviewing candidates,who had been called for interview tofill the newly created jobs.July-September 2010 :: 11

Although there were only four jobs,the number of applications wasinordinately large. Out of these, Capt.Rashid had called only twenty candidatesfor interview– five for each section, outof which he would select the most eligiblefour. Of these applicants, some werealready working in responsible positionson well-known dailies; he personally knewthat they were competent. This was onereason why he was having so muchdifficulty in making up his mind. Onhis way to the office, he vacillated betweenone candidate and the other, not knowingin whose favour to throw his weight.The orderly was sitting on a stooloutside his office. He jumped to attentionand saluted Capt. Rashid.Lost in thought, Capt. Rashid passedhim; slid into the chair and then rangthe bell.Like a puppet pulled by a string,the orderly briskly strode into the room.“Yes Sir.”“Give my salaams to Panditji.” Hesaid and picked up the latest editionof the journal.Of those clerks, who, taking a cuefrom their officers, arrived before openingtime, Pandit Kirpa Ram was the foremost.Fifty five years of easy going life hadmade him soft and rotund. Now baldheaded, with his front-teeth missing, hehad joined service at a young age, andacted as the translator of Gurmukhi, Urduand <strong>Hindi</strong> sections respectively from timeto time. He was now incharge of theDepartment. Not that he was any goodat this job. Far from being an efficienttranslator, he was still raw at the game.But he was a past-master in the art ofhumouring his superiors, which is aninvaluable asset in a Government Officeand helps one clerk to score over hisfellow clerks, gaining him quickpromotion. He would bully his lessfortunate colleagues into grappling withthe work of translation, while he tookupon himself to hail a taxi for the Sahebs;procure rations and poultry for them;or ingratiate himself into their wives’favour by doing odd jobs. He had madeit a point to be the first to greet hisofficer on arrival, and bid him farewellat the time of departure. He would breakinto a broad grin at the faintest traceof a smile on his officer’s face and startfrowning when his officer became grave.It was because of these sterling qualitiesthat by gradual stages he had risen tobe incharge of a section. Before theorderly could convey the Captain’smessage to him, he was standing beforehis boss, teeth bared in a smile.Ignoring his smile, Capt. Rashidacknowledged his salutation with animperceptible nod of the head.Unable to plumb the mind of hisnew Indian master, whose ways wereso different from those of the Britishsahebs, Pandit Kirpa Ram gave anotherbland smile and then stood there lookingblank.“How many people are coming forthe interview?”12 :: July-September 2010

Pandit Kirpa Ram ran out to fetchthe files.Capt. Rashid picked up the latestedition of the journal. The very firstpage carried such a rich crop of misprintsthat his mind boiled with rage. He wasabout to pick up the telephone to callup the press, when the telephone bellrang.“Hello” His voice had a touch ofasperity. “Chaddu.” It was his father atthe other end. “Your mother has alreadyspoken to you about it. It’s about Hanif.Yesterday he came to see me in thisconnection. And besides, he’s our relationyou know...”“I can’t do anything about it, abbajan*,” Capt. Rashid said interrupting hisfather. “Hanif won’t make the grade. He’sunfit for this job.”“What do you mean by unfit? He’sB.A. (Hons.)”“A B.A. (Hons.) does not necessarilymake a good journalist, abba. I wanta journalist, an experienced hand, whocan give a face-lift to our paper. Hanifdoes not know even the ABC ofjournalism.”“He’ll learn. Given a chance, a diligentman can learn anything.”Capt. Rashid felt exasperated at thebrazen demand of his father. “This isa newspaper office, abba jan,” he saidcontrolling his temper, “Not a schoolof journalism. If I recruit a raw hand,what will my superior officers say? Hanifwill not be able to pull his weight withothers. They’ll laugh at him.”“The government offices are full offools– one worse than the other.” TheKhan Bahadur who knew all about theset up, said.“You are inducing me to actdishonestly,” Capt. Rashid bellowed intothe mouth piece. His voice was so loudthat the clerks in the other rooms heldtheir breath.“You are a fool.” He heard his fatherbang down the receiver.Pandit Kirpa Ram placed the file ofthe candidates before Capt. Rashid andstood before him smiling. Capt. Rashid’seyes blazed like live coals. The Pandit’ssmile died on his lips.‘er...er... may I...?”“Yes, you may go.”Holding the collar ends of his tunicCapt. Rashid started pacing in the room.The image of his father and that ofthe other Khan Bahadur, the owner ofthe press, where his newspaper wasprinted, flitted across his mind. Hewanted to vent his spleen on this otherKhan Bahadur, for turning out such ashoddy job on his newspaper. He saton his chair and was about to lift thetelephone receiver when a car stoppedoutside and next moment Major Saleem,wearing a languid smile, entered the room,with a young man in tow.Capt. Rashid got up from the chairand saluted major Saleem. Instead ofJuly-September 2010 :: 13

eturning the salute the Major, who wason friendly terms with him in privatelife, held out his hand. “Please, please,don’t be so formal.” He sat on the oppositechair and before Rashid could take hisseat, introduced the youngman to him.“Here is Mr. Jyoti Swaroop Bhargava,B.A. He’s a well-known <strong>Hindi</strong> writer anda journalist. He’s equally at home withUrdu. He’ll help you with the <strong>Hindi</strong>edition.” Again putting on thatlanguorous smile, he rang the bell andasked the peon to give his salaam toPandit Kirpa Ram.But seeing the car, Pandit Kirpa Ramwas already on his way to pay his respectsto Major Saleem.“Panditji, this is Mr. Jyoti SwaroopBhargava, B.A.” Major Saleem said, “He’llassist you with the <strong>Hindi</strong> edition.” Henodded to the youngman to go withPandit Kirpa Ram. Both of them leftimmediately.“He’s Col. Chopra’s man,” Major said.You’ll have to accommodate him. You’llhave no trouble with him. He knowshis job.”“On which paper is he working?”“He has come from Burma and isnow working as a canvasser for a businessfirm. But while in Burma, he broughtout a paper by the name of ‘BurmaSamachar’.“But translation...”“He has translated two English booksinto <strong>Hindi</strong>. One of them is Col. Hurdon’sPoultry Farming. You know, how acutethe problem of supplying eggs to thearmy has become these days. All unitsare being encouraged to run their ownpoultry farms. You’ll do well to serializeCol. Hurdon’s book in your journal. Mr.Bhargava can prepare <strong>Hindi</strong> and Urduversions.”As if a big load was off his chest,Major Saleem leaned back in his chairand lit a cigar. “The book will be ofimmense interest to our jawans,” Headded. “Most of our Jawans are peasants.Many of them may take to poultry farmingafter the war.”Capt. Rashid found himself in a seriouspredicament. He had already made uphis mind to offer the job to a renownedjournalist, who was working on a leading<strong>Hindi</strong> daily. It became difficult for himto sit in the chair; the strain was gettingtoo much for him.Do you think this fellow will do justiceto the job?” he said at last hesitatingly.“Even our translators have somegrounding in journalism. I was lookingfor a really capable journalist.”Major Saleem ignored his remark.“Col. Chopra has recommended yourcase,” he said after taking a few leisurelypuffs at the cigar.“My case?” Capt. Rashid looked up,surprised.“He was saying, you should bepromoted to the rank of a Major. Yourpredecessors, who were in charge of this14 :: July-September 2010

newspaper were all Majors.”Capt. Rashid wanted to have moreparticulars about Mr. Bhargava, but henever came to the point of asking morequestions.“Aren’t you coming to the meeting?”Major Saleem suddenly asked.“What meeting?”“With the Brigadier of course. Hehas returned from the front and wouldlike to discuss a few important thingsin that connection. Come along. I’ll giveyou a lift.”“But I have to interview thecandidate.”“At what time?”“Between eleven and four.”“Oh, don’t worry. You’ll be back ingood time.”Capt. Rashid had no alternative.Leaving word with his assistant editor,Lieut. Ali Gul Khan to take care of thecandidates, while he was away, he leftfor the Headquarters with Major Saleem.In the evening when Capt. Rashidreturned from the Headquarters, A sikhSubedar accompanied him.At the meeting the Brigadier had madea pointed reference to the technicalmistakes that abounded in the paper.He was particularly sore at the ridiculousrendering of the military jargon intothe vernaculars. For instance, ‘fox holes’was being translated as ‘fox’s dens.’ Suchhowlers were strewn all over the pages.To safeguard against such mistakes theBrigadier had suggested that thenewspaper should have an officer onits staff, who had seen actual fightingand was fully conversant with militaryterminology. The other officers presentat the meeting heartily approved theBrigadier’s proposal and told him thatin fact they were themselves thinkingalong these lines. Col. Chopra went onebetter and pressed for the immediateappointment of an officer of the staffof the newspaper.After the meeting the Brigadier calledCapt. Rashid to his room and introducedhim to a Sikh Subedar. “He is a seasonedofficer,” the Brigadier said, “And is fullyconversant with all the military terms.Put him in charge of the Gurmukhisection.”“My good sir, I know next to nothingabout journalism,” the old Subedar hadsaid as he sat by Capt. Rashid’s sidein the Car. “I worked with the BrigadierSaheb a long time back and he is verykind to me. I requested the BrigadierSaheb to put me on some other job,as I had never seen the face of anewspaper, much less edited it. But theBrigadier saheb won’t listen to me. Hesaid, “well Subedar, you just try yourhand at it. It’s not difficult. I’ll ask theeditor to teach you the game. I wantan officer who has seen actual fightingto serve on the newspaper.”“Which front were you at?” Capt.Rashid asked.July-September 2010 :: 15

“My good sir,” the old Subedar saidnaively. “If I had to die a dog’s death,what was the point in coming here.Unfortunately, I had enlisted in theEngineer’s Corps. I have no experienceof this line. And what is worse, ourCorps is shortly being drafted to theBurma front. I ran to the Brigadier Saheb,“Sir,” I said, “If you want to help me,it is now or never. There’s no one tolook after my wife and children. If Iam packed off to the front, what goodwill your kindness be to me there? TheSaheb has a soft corner in his heartfor me. He took pity on me and shuntedme off to you. I’ll do my best to learnthe job. If I make a success of it, theSaheb has promised to recommend mefor decoration.”Reaching his office, Capt. Rashidimmediately sent for Pandit Kirpa Ram.But the Pandit was already coming toCapt. Rashid. He wanted to pay hisrespects to his boss and was eager toknow what had transpired at theHeadquarters. He stood before Capt.Rashid and smiled ingratiatingly.It was for the first time in threemonths that Capt. Rashid responded tohis smile.“Subedar Saheb is the Brigadier’srecommendee,” he said. “He’ll be theSub-editor of the Gurmukhi edition. TheBrigadier Saheb wants us to have a manfrom the Military wing on our staff. Pleasetell the Gurmukhi translators not to makethings difficult for the Subedar sahib.”“Please do not worry,” Pandit KirpaRam said effusively. “Your instructionswill be carried out. As long as I amthere, my officers need have no worry.”And when he came out with theSubedar the smile on his face hadbroadened into a grin.Capt. Rashid again rang the bell forthe peon. “Give my salaam to Lieut Ali.”“Did you get my instructions?” heasked Lieut. Ali, when the latter cameto him.“Yes Sir.”“Have you interviewed thecandidates?”“Yes Sir, only for the <strong>Hindi</strong> andGurmukhi sections. The others, I haveasked to report tomorrow.“You should have disposed them oftoo. The selection has been more orless <strong>final</strong>ised.”“Who has been selected for English?”“He’s the Director General’s man. TheBrigadier told me that the DirectorGeneral wants the English assistant tobe a man of the highest calibre. It’sthe English Edition that feeds the othersections. Probably he is a man fromthe Headquarters.”“And the Urdu man?”“He too has been selected.”Capt. Rashid picked up a file andgot engrossed in it.Although the file was before him,he could not sign even a single paper.16 :: July-September 2010

Pushing away the file he got up fromthe chair, and holding his tunic collarshe started pacing the room.It was past seven. Hesitatingly thepeon peeped into his room. Capt. Rashidwas still pacing the room as before.Next morning when Pandit Kirpa Ramcame to Capt. Rashid’s room to pay hissalaams, he found a youngman sittingby his side. “This is Mr. Hanif, B.A.Hons.’’ Capt. Rashid said introducing theyoungman to Pandit Kirpa Ram. “He’lllook after the Urdu section.”Pandit Kirpa Ram bared his teethin a smile and bowed to Mr. Hanif.As they were leaving the room, heheard Capt. Rashid saying, “Please tellthe translators to help him with the job.”Upendra Nath Ashk (1910-1996), renowned authorwhose creative output like Premchand was first in Urdu and laterin <strong>Hindi</strong>. He was born and educated at Jalandhar, Punjab and settledat Allahabad in 1948. Except for a few short term jobs in All IndiaRadio and films, he was a whole timer in creative writing. He wroteplays, novels, short stories, poems, essays, memoirs and literary criticismbesides editing the famous literary volume ‘sanket’. He was a progressivewriter who led an eternal struggle against reactionary forces. He wroteregularly from 1926 to 1995. Most of his works were published byhis writer wife Kaushalya Ashk from their own publishing house NeelabhPrakashan, named after his illustrious son who is a major poet andan intellectual in his own right. Ashkji’s major works are ‘girti deewaren’,‘pathharal pathhar’, ‘garm rakh’, ‘badi badi ankhen’, ‘ek nanhi kandil’,‘bandho na nav is thanv (novels); ‘anjo didi’, ‘tauliye’, ‘sookhi dali’,‘lakshmi ka swagat’, ‘adhikar ka rakshak’ etc. (collections of plays);‘akashchari’, ‘judai ki sham’, ‘kahani lekhika aur jhelum ke saat pul’,‘chheente’, ‘ubaal’, ‘dachi’, ‘kale saheb’, ‘palang’ etc. (short story collections);‘deep jalega’, ‘chandni raat aur ajgar’, ‘bargad ki beti’ (poetry collections);‘manto : mera dushman’, ‘chehre anek’ (memoirs); ‘hindi kahaniyanaur fashion (lit. criticism).Jai Ratan : born Dec. 6, 1917 Nairobi, veteran scholar of <strong>Hindi</strong> andEnglish who has devoted a life time to translation. He worked as P.R.O.in a prominent business firm in Kolkata and was founder memberof Writers’ Workshop. <strong>Hindi</strong> owes him a tribute for numerous prestigiousEnglish translations including Premchand’s Godan way back in 1955.He now lives in Gurgaon.July-September 2010 :: 17

HeritageDACHIUpendra Nath AshkTranslated by the authorBakar– the Muslim Jat from the hamlet Pi-Sikandar-was greedilyeyeing the dachi (She-camel). Chaudhary Nandu, who was restingbeneath a tree roared, “You there! What are you doing?” Andhis six-foot tall massive body, which lay propped against the trunk,suddenly grew tense and his broad chest and rippling biceps showedbeneath his buttonless kurta.Bakar came a little nearer. His eyes flashed for a brief momentfrom the dark, sunken hollows and his face lit up in the blackand dusty frame of his pointed beard. His moustache, closelytrimmed over the upper lip according to his religion, quiveredslightly and he said with a faint smile, “I was just looking atyour dachi, Chaudhari. What a lovely, spirited animal she is!”Hearing his dachi praised, Chaudhari Nandu relaxed. Smilinghe enquired, “Which one do you mean?”“There, you see. The fourth one from the left” Bakar said,pointing to the dachi.There were about eight or ten animals tethered under the shadeof a tree; the dachi in question was craning her long and beautifulneck to pluck at the leaves.In the cattle fair, so far as one’s eyes could travel, nothingwas visible except a large number of tall camels, black and uglybuffaloes, hefty bullocks and cows. There were quite a few donkeystoo. But the camels predominated in this fair, which was being18 :: July-September 2010

held in the desert near Bahawal Nagar.Camels in this region were put to workin a number of ways, mainly for transportand agriculture. In the past, when cowscould be bought for ten rupees andbullocks for about fifteen rupees, a goodcamel fetched no less than fifty rupees.Even now, when this area received anadequate water supply, camels have notlost their usefulness; in fact, those usedfor riding are sold for anything betweentwo to three hundred rupees, and thoseemployed for agriculture and transport,for not less than eighty rupees.Advancing a little closer, Bakar said,“To tell you the truth, Chaudhari, I havenot seen a more beautiful dachi in thewhole fair.”“Why just this one? Nearly all mycamels are equally fine, because I feedthem properly,” Nandu said proudly.“Would you like to sell it?” Bakarasked with diffidence.“That’s what I have brought it herefor.”“Then tell me a reasonable price forit.” Nandu’s penetrating eyes surveyedBakar from top to toe and he said, smiling,“Do you want to buy it for yourselfor for your landlord?”“For myself!” Bakar answeredemphatically.Nandu nodded his head somewhatindifferently. He could not think of thispoor labourer being able to afford acamel. He said nonchalantly, “I’m afraid,my man, you won’t be able to affordit.” With 150 rupees in his pocket Bakarexcitedly said, “It is none of your businessto ask me for whom I am buying it.Your only concern is the price of thecamel. Now tell me.”Nandu again looked critically atBakar’s weather-beaten face, the dirtyclothes and the rough pair of homemadeshoes. And to get rid of the fellow,he indifferently demanded a high price,“You must look for an ordinary camelelsewhere man, for I shan’t accept apie less than a hundred and sixty rupees.”A quiver of joy crossed Bakar’s seamedand weary face. He was afraid thatChaudhary might suggest a price beyondhis capacity, but now he felt happy.He was short of only ten rupees andthought, if Chaudhary does not yield,I will ask him for credit for this smallsum. He was simple and naive, ignorantin the ways of bargaining and haggling.Hopefully, he whipped out the foldedbundle of notes from his pocket andflung it at Chaudhary, saying “Well, youmay please count these. I’m sorry Idon’t have more. It is entirely up toyou to <strong>final</strong>ize the deal.”Nandu started counting the moneyrather indifferently, but as he finishedit, his eyes brightened. He had quotedan exorbitant price only to avoid Bakar.One could get good camels for less thanhundred and fifty rupees and for thisone he had not expected anything morethan a hundred and thirty rupees. Buthe artfully wore a grave expression onJuly-September 2010 :: 19

his face and told Bakar in a patronizingtone, “My camel could easily fetch twohundred rupees, but I will give it toyou for a hundred and fifty rupees.”Saying this he got up, untied the cameland handed the bridle-string over to him.For a brief moment, Nandu’s hardheartednessmelted instinctively and gaveway to a rush of natural tenderness.The camel was born and bred at hisplace; and today, after all the years ofaffectionate rearing, he was no longerits master. His heart was inundated withthe same feelings that come to a fatherat the time of sending his daughter tothe bridegroom’s place. He murmuredsoftly, “I needn’t remind you to takegood care of this camel. I brought herup with great love and devotion.”“You need not worry, Chaudhary.I’ll tend it with the greatest care possible,”Bakar replied, his heart surging with joy.Nandu put the money carefullybetween the folds of his waist-cloth, andthen filled an earthen cup with waterfrom the pitcher to slake his thirst.Everywhere in the fair, huge columnsof dust rose towards the sky. Dust isa common feature even in fairs heldin the cities. The temporary pipes thereand the water-bearers sprinkling waterthe whole day long do not help much;it was no wonder then that in this desertfair, dust reigned supreme: on the vender’ssliced pieces of sugar-cane, on the halvaand Jalebi of the sweetmeat-seller, andon the spiced delicacies at the stalls–everywhere a thick layer of dust hadsettled. The drinking water was carriedfrom the canal, but by the time it reachedthe fair, it invariably became muddy.Nandu had thought of drinking somewater after the dirt had settled. But histhroat was dry and parched. He gulpedthe water greedily and pursing his lipsasked Bakar if he would like a cup ofwater. Though Bakar was thirsty now,he had no time to drink water. He wasin a great hurry to return to his villagebefore nightfall. Holding the bridle ofthe camel in his hand, he gently ledthe animal through the blinding dust.Kameens by caste, Bakar’s ancestorswere potters; but Bakar had given uphis ancestral occupation and eked outa meager living in the fields, workingas a landless labourer. He had alwaysbeen lazy, and he could afford to remainso, because his wife, who loved himand cared so much for his comfort andhappiness, worked very hard.His carefree days, however, endedwith his wife’s passing away about fiveyears ago, leaving behind a doll-likedaughter. On her death-bed, she hadwhispered to him, “I am now leavingRazia all alone in your care. My lasthope is that you will save her fromall troubles.”This last wish of his wife altered thecourse of Bakar’s life. After her death,Bakar brought his widowed sister fromher village, and throwing off his slackness,devoted himself conscientiously to20 :: July-September 2010

fulfilling his wife’s wish.He worked hard so that he mightbe able to buy good things for his daughterto make her happy. Whenever he returnedfrom the market, little Razia would clingto him, and fixing her eyes on his dustyface, ask, “What have you brought forme, Abba?” Bakar would lift her ontohis lap and planting a kiss on her cheek,give her many toys and sweetmeats.As soon as Razia got these, she wouldjump down and run away to show hertoys to her friends.When she was eight years old, oneday she asked her father, “Abba, I wanta dachi. When will you buy one for me?”Poor, innocent child! How could sherealize that she was the daughter of apoor landless labourer who could notafford a dachi? But lest he hurt thetender feelings of his daughter, Bakarsmiled and said, “My darling Razzo, whatwill you do with a dachi?”But he failed in attempting to distracther. Razia had seen the landlord comingto their hamlet riding on his dachi, withhis little daughter seated in front of him.It was then that Razia had begun tolong to ride one herself. And realizingthe intensity of her longing, the lastvestige of Bakar’s laziness had vanished.Although he had somehow succeededin diverting the attention of his daughterthat day, he took a vow to buy hera dachi before long. To earn enoughmoney in order to fulfill his daughter’swish, he started going to the neighbouringvillages seeking more work. Very soonhis daily wages increased with the volumeof labour he was putting in. During theharvest season, he used to reap the cornin the field, thresh and cleanse the grain,and prepare fodder for the cattle duringthe sowing season; he ploughed in thefields and did many odd-jobs. Wheneverhe could not find work in the villageitself, he would get up early in themorning and go to the market, trudginga distance of 16 miles on foot, to doodd-jobs there. All the time he was intenton saving a good slice of his incomewith a miser’s frugality. Sometimes hissister would say, “How much you havechanged, Bakar! Never before you workedso hard in all your life.”“You want me to remain a lazy loutthroughout my life? Hmmm...?”“Oh no! I don’t mean that you shouldremain lazy, but I don’t want you toearn money at the cost of your health.”And always, on such occasions, Bakarwould almost instinctively be remindedof his dead wife and her last wish. Hewould then throw an affectionate glanceat his daughter playing in the courtyard.A tremor of inexpressible bliss would touchthe inner-most core of his heart and acontented smile would play across hislips; and a renewed sense of energy andenthusiasm would pervade his whole being.Today, after a long spell of hard workfor nearly a year and a half, he hadat last fulfilled his long-cherished desire.July-September 2010 :: 21

He held the bridle-string of the dachiin his hand and was returning homealong the path skirting the edge of thecanal. It was evening. The rays of thesetting sun had daubed the scene intints of gold. The air had turned dampand in level fields, far away, a ‘redwattledlapwing flew low over the groundrepeating its shrill cry : tihu-tihu-hut...tihu-tihu-hut. Bakar was howeveroblivious of the surrounding beauty. Hismind roved through the meandering alleysof his past. Sometimes a farmer ridingon his camel would pass him. At timesthe children of the farmers sitting onbig stacks of hay in the carts wouldaffectionately urge on the pair of bullocksand sing a broken line or two of a folksong, or play with the ungainly camelswho followed the carts.Swaddled in his own dream, Bakarthrew an indifferent glance at theenchanting landscape touched by thelast rays of the setting sun. His villagewas still a long way off. He looked backmomentarily at the dachi mutelyfollowing him, and then, with a surgeof unutterable delight, hastened his stepsto reach home before Razia went to bed.With his landlord’s village in sight,Bakar’s own hamlet was only some fourmiles away. His pace slackened a littleand as he neared his destination hisimagination began to run riot. Bakarvisualized his daughter clinging to hislegs joyously, her eyes full of wonderand curiosity as she looked at him holdingthe bridle of the camel... He imaginedhimself riding the dachi along the canalbankwith Razia seated in front of him.It was evening and mild wind was blowing.At times a jungle crow cawed and flewabout, flapping its heavy wings. Razia’sjoy knew no bounds. She felt as if shewere flying in an aeroplane... Again, heimagined himself visiting a market atBahawal Nagar with his daughter. Shelooked curiously at the mountainousheaps of grain and innumerable hackneycarts. A gramophone was playing at ashop and Bakar took her there. Poorgirl! She was at a loss, not knowing wherethe sound came from, wondering if therereally was a man singing from withinthat box. Bakar went on explaining butshe did not understand a word of whathe said and her eyes gleamed with wonderand excitement...While he was lost in these dreams,his mind was arrested by a sudden thoughtas he entered the village of his landlord.This was not a big village. All the villagesin this part of the country were alike.Even the biggest one had not more thanfifty houses. Tiled roofs or brick wallswere not to be found in this area. InBakar’s own hamlet there were only fifteenhouses. They were in fact small thatchedhuts. His landlord’s village was slightlybigger with nearly twenty-five huts. Thelandlord’s house was made of brickalthough the roof was thatched.Bakar stopped before the house ofNanak, the carpenter. Before going tothe fair he had asked Nanak to preparea saddle for a camel, and now on his22 :: July-September 2010

way home he was reminded of it. ShouldRazia insist on riding the dachi howcould he manage without a saddle? Hecalled out the carpenter’s name onceor twice but his wife’s shrill voiceanswered from inside that he was notat home, and had gone to the market.Bakar’s heart sank. If Nanak had goneto the market, he could not possiblyhave prepared the saddle. Bakar drewsome comfort from the thought that hemight have just found time to attendto it and he enquired again, “I had askedhim to prepare a saddle for my camel,I wonder if he has made it.”“I don’t know”, came the curt replyfrom inside.Half of his enthusiasm ebbed away.It was no use taking the camel homewithout a saddle. Had Nanak been there,he could have taken an old one fromhim, even if he had not prepared theone he had ordered. Then suddenly hiseyes twinkled as he thought of a solution.He could see his landlord who had manycamels and might spare him an old saddletill he got his own. And he took a turntowards his landlord’s house.The landlord had amassed a hugefortune while in government service, andwhen the canal was extended to thisarea he had at once bought many acresof land cheaply. He was now earninga handsome rent from his lands afterhis retirement.He was smoking a hookah as hereclined there in his courtyard and waswearing a white turban, a matching whiteshirt, a milk-white tehmad and a velvetjacket over his shirt. When he saw thedust-smeared Bakar, holding the stringof a dachi, he enquired, “Where areyou coming from Bakar?”Bakar bowed a little and saluting himsaid, “Sir, I’m just returning from thecattle fair in Bahawal Nagar.”“Who owns this dachi?”“It’s mine, Sir. I bought it there.”“What price did you pay for it?”Bakar felt like telling a lie that hehad paid Rs. 160/-, because he felt surethat such a handsome dachi was worthRs. 200/-. But he could not tell a lie.“He was demanding a hundred and sixtyfor it,” he said with utter naiveté, “butreduced ten rupees for me.”The landlord threw a searching glanceat the dachi. He was desirous of buyinga beautiful dachi for himself. Althoughhe had a good dachi for riding, shehad contracted a disease last year andhad lost her former gait. Bakar’s dachiappealed to him tremendously. Howlovely and well-proportioned were herneck and features, her white and greycomplexion adding to her beauty.“Well, you take Rs. 160/- from me.I’ve been on the lookout for a camelmyself,” the landlord said.“Sir, I am sorry. I have bought thecamel to fulfill the long-cherished desireof my little daughter,” Bakar mumbled.A chill of fear ran through his wholeJuly-September 2010 :: 23

eing, but his lips trembled to form aweak smile.The landlord rose to his feet, andcoming near the camel, he gently pattedits neck. “Oh, what a lovely dachi youhave bought, Bakar! You may take Rs.15 extra. Agreed?”He called for Noore, his servant, whowas cutting grass for the buffaloes. Hecame running with the scythe in hishand. The landlord told him, “Take thisdachi and tie it over there. I am buyingit for Rs. 165/-. How do you like it?”Noore snatched the bridle-string fromBakar’s hand, who stood dumbfoundedand sorrowful, and eyeing the camel said,“She is indeed very handsome, Sir.”The landlord took out Rs. 60/- fromhis pocket and gave them to Bakar witha crafty smile, “Just now a tenant hasgiven me this money and perhaps itwas destined for you. Keep it now andI’ll send you the rest in a month ortwo.” And without waiting for a replyhe turned away. Noore had once againstarted cutting grass. The landlord againshouted “O you, Noore! Better leave thefodder for the buffaloes now. Go andfeed the dachi at once. She looks sohungry.”And coming closer to the camel heappreciatively patted it.The moon had not yet risen. Therewere a few stars twinkling in the clearazure sky, and in the distance the dumbacacia trees took on the appearance ofdark patches. When he reached his hamlet,Bakar lurked behind a bush and lookedbreathlessly at the dim light that issuedfrom his hut. He knew that Razia wouldstill be awake in anxious expectationof his return. And he waited for thelamp to be put out, so that he mightenter his hut after she had gone to sleep.courtesy : Neelabh24 :: July-September 2010

MemoirTHE GRACEFUL CHARMER, ASHKRajinder Singh BediTranslatedbyS.S. ToshkhaniThe year was 1936. A condolence meeting was held at a localhotel in Lahore to pay homage to Munshi Premchand.It was just the beginning of my literary career. I must havewritten about a dozen short stories or so, which slowly beganto appear in literary magazines after minor difficulties. The entirebatch of us new writers was influenced by Premchand. That iswhy all of us were feeling as though we had lost our godfather.That was the reason why I too went there to make my sorrowknown to others and make the sorrow of others my own. Italso occurred to me that this would enable me to meet the realinheritors of Premchand’s legacy, whom I knew indirectly buthad never met.The programme of the condolence meeting began. It is rarelythat good writers are also good speakers. Some people madevery good speeches. Some such people too were in the meetingwho beat their breasts and created a mournful atmosphere. Theyall were ‘pamphleteers’. This reminded me of Sharatchandra Chatterji’sDevdas who, when his father died, asked customary mournerswailing and weeping in a corner of the house to go to his worldlybrother, saying, “Over there. That side.”There were some “this-siders” also in that meeting. One ofthem– a brown complexioned guy with his forehead as if a slateplaced slantingly against the wall, his hair arranged in TusharkantiGhosh style, his eyes covered by Harold Lloyd glasses– got up.July-September 2010 :: 25

He was dressed in dhoti-kurta– a mosqueabove, a temple below– tired-looking;distracted; sad; dead ages before death...“I want to say something”, he said,joining his fingers to his thumb andextending his hand towards the chairman.Even though the chairman had notyet given the permission, he went tothe table and began to speak in a coarsevoice and rough accent. It appearedas if he was straightening the humpsof <strong>Hindi</strong> and Urdu with a Punjabi hammer–Now he set out for London, arrived inCalcutta; then people saw—“Oh, he isroaming in Coimbatore!”; no he is inDelhi; and just then he arrives at hisdestination in an imaginary jet plane.As for his speech, it was like the gaitof a person who has boozed a little toomuch to drown his sorrow. But he didn’tbother about anyone. He went onspeaking in the “nalaa paaband-e-naynahin hai” 1(“the gushing water is notbound by the pipe”) mode and, standingat one side of the table, looked as ifhe was father of the whole universe andall else were his children who were playingand should be allowed to play.In spite of all this, his speech waseffective, because it came straight fromthe heart, which does not accept rulesof grammar. It was suffused with a painand restlessness which falls to the shareof the devastated and the geniuses only;its illogical reasoning leaving the‘pamphleteers’ dazed. He was referringto the letters that Premchand had writtento him during his lifetime, which gavethe impression of emotional intimacywith a fellow writer rather than “guidance”or “solution of problems”. In thosemoments of grief, these letters hadbecome more of a literary treasure thanmere letters.This was Ashk. I had not even methim before this. I had no doubt readhim in Sudarshan’s magazine ‘Chandan’,but not seen him. I had not even seena picture of his. Those who know Ashkwill say that this cannot be possible,for Ashk, besides writing and editing,also believes in publicity and regardsthe writer who knows merely how towrite not only as a fool of the firstorder but also stupid.Later, I too noticed – with absoluteinformality, Ashk foists an absurd-lookingphotograph of his on an editor or apublisher and the poor fellow has topublish it willy-nilly. And what aphotograph it is. Front one fourth, threefourthsor profile with the locks fallingon the shoulders or if the face is wellshaven, then hair is very skillfullyfashioned into curls. After closely lookingat it for sometime, one thinks it is ofa man... now bare, now covered … Ifearlier there was a <strong>Gandhi</strong> cap on thehead, now he has a felt hat placeddeliberately aslant on the head, makinghim look foppish. What is more, evenhe himself is smiling. Or else he is donninga black curlew cap … with his eyes halfopen,trying to look very much like a26 :: July-September 2010

coquettish charmer– which is irritatingto the eyes of thousands of his readers,yet finds a place in their hearts. Inthe words of Hafiz 2 , ‘he is relaxing inthe private chamber of the heart andthe world is under the illusion that heis sitting in the assembly’. I, who wantto see a beard only on the face of anenemy, and because of that phobia donot even look into the mirror, see aFrench-cut goatee on his face. Nobodyknows what Ashk will look like in hisnext photograph, not even Ashk. Because,despite his slender body and mind assharp as a razor’s edge, Chanakya’sintelligence and far-looking eyes, Ashkfully respects only the present momentin which he is living at that time. Heenjoys life not only through the sensesbut his consciousness too is involvedin it in full measure. If anybody haswrongly understood Krishnamurti’s 3discourse on the present, it is Ashk.May be in one of his next photographshe may appear in a Jogi’s dress withone hand raised to pronounce ‘chhu’ 4on the spectator. The matter does notend here. The photograph may evenbe published in some novel ‘tender asa flower bud’, but strong enough to ‘cutthrough the heart of a diamond’.May be some primeval friendship orlasting relationship was destined to beestablished that even though notintroduced to Ashk, I was convincedthat this man could be none else thanAshk. Ashk was the only one amongthe writers of that era who was closeto Munshi Premchand and yet he wasdifferent. Munshi Premchand must havewritten letters to so many other peoplein his life, but the letters to which Ashkwas referring pointed to something thatthey both shared…The meeting came to an end. Thosedays I was working as a postal clerkand was, hence, greatly afraid of publiccomplaints. I, therefore, approachedAshk slowly and gingerly. He wasdiscussing something with some editor.Discussion for discussion’s sake has beenAshk’s hallmark to this day. It is notthat what he wants to say has no logicor weight. It has everything, and yetit has nothing. Ashk derives some sortof a vicarious pleasure from it and usesall the weapons of argument and debateto make his point heard. A man maybe saying something quite sensible, butAshk tells him that it is two differentthings they are talking about and putshim in such a dilemma, such a quandary,that he goes off the track and you knowwhat follows once a train goes off thetrack. The opponent is left smartingwith impotent rage. If he is clever anddoes not want to be drawn into a wrongkind of discussion, then Ashk can beseen bursting into a loud laughter andsaying, “You’ve become serious, yaar!”And while the opponent has still notunderstood him fully, Ashk holds hishand and says – “Actually, I too amsaying the same thing as you are.” Andwhat else can the other person do afterthis but feel stunned and think whatJuly-September 2010 :: 27

a silly person he is or feel angry thathe has been unnecessarily made toexercise his tongue. The result in boththe cases is the same. If someone isdispleased, Ashk wins the day, if someoneisn’t displeased, then too Ashk wins theday – it is a win-win situation for himevery way. As I slowly went towardsAshk, the editor had already faced themusic. Now it was my turn. I steppedforward and said –“Ashk Sahib…!Ashk swiftly turned round and fixinghis gaze upon me started looking rightthrough me. Now, if you fit a camerawith x-ray light instead of the ordinaryone, what will even the best romanticscene be like? What else than a skullcollides with another skull, a skeletonraises its arm and it gets stuck intoanother skeleton’s throat, and it comesto be known that a member of the othersex has been pulled closer not to hugbut to smother. And then where isthe throat? …“Ashk Sahib, for a longtime it has been my desire to…”“You…?” And then, (dropping thehonorific aap) the next very moment,he was saying, “You are Rajendra SinghBedi, I presume?”Suddenly I felt as though I hadforgotten my name. At least I certainlyfelt that Rajendra Singh Bedi was someother person, and I just happened toknow him. Then coming to my own,I said, “Yes, Mr. Ashk, Rajendra SinghBedi is what they call me.”How far does a man’s ego reach?Indeed, what a big forest this world is,what a vast desert in which he wandersas though lost, wishing every momentthat someone should recognize himsomeone should call his name. And ifthat happens, how happy he feels. Achild slowly learns to say his name andbegins to distinguish himself from others.But when he grows up, acquiring hisworldly name, how hard does he striveto know his real name and after beingidentified by it cannot distinguish it fromGod’s name. And then in spite of hisdesire to merge in Him, he wants toretain his own <strong>sep</strong>arate identity as well.If I recognized Ashk without anyintroduction, he too recognized me atone glance. I was a very small writerand such a big writer knew me by myname.… No, no, he even mentioned thetitles of one or two short stories ofmine, which had appeared those daysat short intervals in some Lahorejournals… He was even admiring them.… Can it be true? Is there a placefor an incapable postal clerk like mein this vast desert?…Whether a place was there or not,whether even now there is a place ornot, that is not to be argued. If Ashklikes someone, he also accepts him andmakes a conscious effort to create aplace for him in this world of nameand address. This is something thatI have found abundantly in Ashk. Todaywhen I look back at the thirty years28 :: July-September 2010

of my literary career, I bow my headwith regret – I for one have not helpedany new writer as Ashk has. I too couldhave praised someone, criticizedsomeone, and made someone’s path easyfor him. But Ashk is Ashk and Iam I! Even now when I meet Ashkand find him mentioning some newwriter’s name, I feel surprised. Thelove that one has for oneself all thetwenty-four hours turns into hate, andbecause a man loves himself in allcircumstances, one feels annoyed withAshk. … What is the reason for thisweakness that I have? It may perhapsbe difficult for me to explain this andfor someone to understand! To makethings simple, I will confine myself tosaying that from the beginning I havebeen suffering from some kind ofinferiority complex, and despite all myefforts, despite being praised and admiredby others, I have not been able to shakeit off. For instance, I do not haveconfidence in myself… Why do I nothave confidence? If someone wants tounderstand it, he shall have to live mylife, and to know why Ashk has it, heshall have to live Ashk’s life.Next very moment we were talkinglike two friends, as though we had knowneach other for years. … It was summer,perhaps, and the sky was covered bya cloud of dust. The dust had risenfrom the dirt tracts below and carriedupward by tramping of countless horsesand unbridled winds and was now comingdown slowly, particle by particle. Wewere walking on foot. Ashk was theone who was doing the talking and Iwas listening. He wanted to say so manythings. Why was it so, I came to knowlater. At that time, we were talkinglike a newly wed couple, who say alot many things to each other for thewhole night and on the next day wonderwhat they had said. Walking on footand chatting with each other, we reachednear Anarkali where Ashk showed mehis house.Ashk’s house was a little away fromthe Anarkali Market in a denselypopulated back lane where women couldbe heard talking with one another faceto face from their houses: “Sister! Whathave you cooked today at your place?”She replies, “I haven’t cooked anythingtoday as he is going to eat out. Couldyou please send me a katori 5 of daal.”And if you happen to pass by lost inyour thoughts, garbage is likely to fallon your head from above and set yourmood right. The lane is not wide enoughfor one to jump over and stand on oneside. And then there are windows facingeach other. A boy standing at a windowholds the hand of a girl bending fromthe opposite window and scratches herpalm. This is a common scene in Lahore,showing that in matters of amour thereis no place in the world that beatsLahore!... And it was in this very lanethat Ashk lived. There is a differencein the way you pronounce ‘ashk’ (meaning“tears’ in Urdu) and ‘ishk’ (meaning ‘love’),but it comes to the same thing. WhoJuly-September 2010 :: 29

knows when ‘ishk’ will change into ‘ashk’and vice versa? … Ashk had a twostoreyhouse, with his dentist brotherDr. Sharma living in the upper storeywith his wife and children, and Ashkand his library – his workplace – locatedin the lower. To reach it you hadto pass through “heaven for the thinman” and “hell for the fat man” typeof stairs. There was a rope, soiled bypeople’s hands repeatedly holding it. Ifyou did not hold it for going up thestairs, there was every danger of yourtumbling down. … It was in this narrowand dark house that Ashk lived. It washere that he would write in the wishywashystyle of an artist, cross what hewrote, and then write again — erasingold lines and drawing new ones. Writingwas a habit for him and an act of worshiptoo. It was something that transcendedlife, and transcended death as well!Ashk began to earn his livelihoodfrom his childhood. His father was astationmaster, who had the habit ofdrinking and neglecting home. Wheneverhe would proceed towards home, it wasfor reprimanding or thrashing someone– quarreling with his wife, thunderingat her, or suspending a child upsidedown and beating him up mercilessly.He looked like a tyrant and thought likea tyrant. A decision once taken was<strong>final</strong> and irrevocable. To this cruel manwas married an extremely gentle woman,Ashk’s mother. Her husband’s atrocitieshad left permanent lines of sorrow onher face. In addition to domestic quarrels,Ashk’s writings have characters thatrevolt against their parents. And it wasbecause of the overbearing personalityof his father that Ashk left paternal shelterto find a place for himself in life. Theson threw a challenge, the father tookit up, and both were victorious. For,he who was buffeted by storms and hadfaced hostile winds of life, who fell avictim to a mortal illness like tuberculosisbut mocked death and escaped it, whodespite utter poverty and indifferenceof friends and kith and kin steadfastlyran the business of writing andpublication in a jealousy ridden city likeAllahabad, could have been the son ofsuch a father only.Ashk’s parents had brought six sonsinto this world (actually they had broughtseven but one of them died in infancy),and all of them males. They were broughtup in Jalandhar, a zone which producesgems of men; where every person isa poet or a singer; where the Harvallabhfestival is held every year; a place towhich maestros of classical music aredrawn from the whole of India and yetare afraid to sing because every childthere is a ‘connoisseur’, knows wherea note has gone wrong and so feels noneed for showing deference to anybody.In whichever corner he may be sitting,he will call out from there with aninvitation to kneel submissively beforehim or his guru and learn music fromhim for several years. During winternights, he will sit around a fire andstart recitation of couplets, which will30 :: July-September 2010

go on until morning hours. … Everyperson of that city considers himselfa genius, and if anybody does not accepthim as one, then a hand will rise andgo straight towards the turban of theperson who does not accept itstraightforwardly, and then it could cometo even abuses and blows. … All thesix brothers were products of that cityand it is not surprising that each oneof them was a well-known figure in hisown field – possessor of a personalitythat only he will deny who wants toinvite trouble. It so appears that apunch is also a part of an argument.And, if for some reason he is unableto land a punch, he will at least beraising hue and cry without any reason.Cries of, “Oh I’m dead! They’ve killedme!” will be heard, with people pretendingnot to have heard them. It is not justone-day’s affair that one can dosomething about it. Every day the roarof someone or the other is heard fromthis house. They are all lions, the sixof them. If an elder brother pins theother one down under his weight, theyounger one too will not desist fromgrowling. If nothing, he will raise anoutcry. Nothing here happens withoutnoise. There is commotion all around.Two of them will be going hither, threeof them thither. They are coming outof their den; someone is being beatenup for allowing himself to be beatenup. This is followed by everyone comingout to roar. A roaring voice is drownedby a still louder roar— “Silence!” Thisis father’s voice – the roar of a lion,hearing which the whole jungle falls silent.In this mountainous zone, there is nofox — not one sister (one was born,but did not survive). Gentle as a cow,mother trembles when father sits withthe bottle in front of him. He commitsa mistake but being a Brahman, he alsoknows how to obtain pardon. He sings:“O lord, do not mind my vices!”Ashk’s father was proud of being aBrahman. He was the descendant ofthat Parshuram who had decimatedKshatriyas twenty one times, axe in hand.These descendants of Parshuramintimidate Kshatriyas, whose professionit was to kill and be killed and whowere not subdued by anyone, and arenot even today. It seems that boozingby Ashk’s father increased after the birthof a couple of children. …After fairlygood names like Surendra Nath, UpendraNath, he came to Parshuram, who wasthe third among these brothers. Thereason for this was that they lived inthat quarter of Jalandhar whereKshatriyas (Khatris) were always atdaggers drawn with Brahmans. Abouta year back the Kshatriyas of the localityhad mercilessly beaten up their mentallyunsound uncle in absence of Ashk’s fatheras Ashk’s gentle mother and greatgrandmotherlooked on helplessly withsuspended breath. Since then Ashk’soutwardly weak and gentle mother hadtaken a vow in her mind, and it wasbecause of this vow that the new- bornbaby was named Parshuram. From hisJuly-September 2010 :: 31

childhood the child was told: “What! …You cry although you are Parshuram,he who decimated the entire Kshatriyaclan and did not bat an eyelid?” …And the child would stop crying, thinkingthat he will destroy all Kshatriyas whenhe grows up. … Ashk’s father namedthe fourth son as Indrajeet – son ofthe Brahman Ravana, who subdued Indra,the king of gods, and made the KshatriyaLakshman unconscious by shootingshakti-baan (arrow consecrated in thename of Shakti, the goddess personifyingdivine power) at him. Were it in thepower of Ashk’s father, he would rewritethe whole of Ramayana wherein it wouldbe proved that the Brahman Ravana wasthe hero and the Kshatriya Ramchandrathe villain.About Ashk’s mother, astrologers hadpredicted that she would be the “motherof seven sons”. In the first place shewould never have a daughter, and evenif she had one it would not survive,the joy of kanyadaan (giving away adaughter in marriage) was not writtenin her fate. And that is exactly whathappened. Only boys fell to her shareand, because of the teaching theyreceived, each one was a brasher, morebelligerent than the other was. Thevengefulness of the Pathans is well knownin the history of the world, for theybequeath their feuds, like their property,to their children in inheritance. ButAshk’s parents were no less vengeful.In the end, a day came when Ashk’sbrothers had thrashed all the Kshatriyasof the locality and sent them to hospital.It is obvious that Parashuram was thehero of this war. He single-handedlyvanquished all his enemies. Althoughhe himself was wounded and also fellinto the clutches of law, everybody wasglad that the soul of the mad grandfatherwould be feeling happy watching all this.These then were the main charactersof Ashk’s play ‘Chhatha Beta’ (The SixthSon) and his voluminous novel ‘GirtiDeevaren’ (The Crumbling Walls). Ashkwas the second of these brothers. Thenthe wives of these brothers startedarriving. Goats began to be tetheredby the sides of lions. Now, you sayhow they could have any food or drink.Even if they did have food or drink,would it at all be wholesome for thebody in such an atmosphere of mutualviolence and commotion that prevailedin the whole house? Before the housein Anarkali, Ashk lived with his elderbrother in an extremely damp, narrowand dark house in the Changad localitywhere they did not have air but eachother’s breath to inhale. In this‘Hairatabad’ or ‘place of surprises’, theutmost that the women could do wasto cry or feel choked.When Ashk’s wife Sheela came as abride, she was a plump girl of tawnycomplexion laughing about everything.She began to feel choked in theatmosphere of this house. Still, shewould laugh at the earliest opportunity.It appeared that nothing could suppressher laughter. I have not met Sheela,32 :: July-September 2010

ut in Ashk’s room in Lahore and laterin the room of his elder son Umeshin Allahabad, I surely have seen herphotograph in which she is smiling. Evendeath could not suppress her laughter…. Ashk would remain very busy thosedays. He would take a close look athis writings, take them to the marketto see if they were selling or not. Someof them sold while some did not. Somemoney was realized and some was not;but it was because of these very writingsthat he got a job of an assistant editorin the Urdu daily “Bhishma’ and laterin the ‘Bande Mataram’. During leisuretime, he would engage himself in ghostwriting – manuals written by Ashk soldin thousands but all he got for themwas peanuts. Then another incident tookplace. Ashk’s father-in-law becameinsane. His mother-in-law began towork as a maid in the house of a richman. For her even taking water at herson-in-law’s house was taboo, and shewanted to be near her husband. Thishurt the sentiments of Ashk and Sheela.Ashk decided that he would give Sheelasuch a position and status socially thather inferiority- complex would go. Hedecided to sit for the examination fora sub-judge’s post.Now he began to study law. Literarywork, college studies, tuitions during theday and personal study and reflectionin the evening. He had books as largeas mansions, but the stuff of which Ashkwas made, the bone of which his spinewas formed, could withstand any hardwork. Meanwhile, Sheela gave birthto Umesh –Ashk’s eldest son. She fellill because of the atmosphere in thehouse and lack of nutritious diet. Ashkhad not yet taken his F. E. L. examinationwhen the doctors suspected it to betuberculosis. Ashk did not accept defeat.He passed his F. E. L in the first division.During his L. L. B. he took her to Lahoreand got her admitted there to the GulabDevi Hospital, eight miles away fromthe city. Now he would do literarywriting on one side, study law on thesecond, and on the third side visit Sheelatwice or thrice a week in the hospital,which was situated away from ModelTown even. He did not believe thatfate would take this cruel joke to thelimits of baseness. He thought that Sheelawould get well, but even as he passedhis law exam with distinction, Sheelapassed away. God gave with one handand took away everything with the other.Now there was no order, no purposeleft in life. Ashk gave up the idea ofbecoming a sub-judge. She for whosesake he wanted to become a sub-judgewas no more. … He picked up his penin a state of terrible sorrow, terriblegrief, endless exhaustion and engagedhimself in literary creativity, as it wasby burying himself in literary creativityalone that he could forget, to some extent,that terrible tragedy of his life. It wasdomestic quarrels, dreadfulcircumstances, social injustice which heformed the subject matter of his writings.During this period he had already startedJuly-September 2010 :: 33

writing his novel ‘Girti Diwaren’ (‘TheCrumbling Walls)’, which can also bepartly regarded as Ashk’s autobiographyand which is his greatest attainment.Along with this, he also wrote the ministories–Konpal (The Sprout), Gokhru,Sangdil (Stonehearted), Nanha (LittleChild), Pinjra (The Cage), which beara clear imprint of his extreme dejection.Perhaps Ashk will bear witness tomy statement that he had been in lovewith only one woman in his life andthat woman was Sheela, because for allhis awareness, he did not know in thatage what love is. Nor did Sheela know.Both of them were living, sometimesfor their own sake, sometimes for eachother. And it was a love which waseffortless in its every act, which wasn’tdependent on any name or quality. ... Even after this Ashk was in love, butit was love from which the passion wasmissing. He had acquired a certainmaturity that made it possible for himto leave Maya, his second wife, onlyone month after marriage and say toKaushalya, his present wife, “Darling!I am tired in this journey of life. Ido not have anymore that flare of youthin me. If you are looking for that inme, then it is futile. I am not worthyof that love which flashes like a flame.I can give you the love that cooks onlow heat and therefore tastes good.”Thus it was that Ashk took me tohis house and talked about a hundredthings. He revealed to me all about himselfwithout any reservation. Experiencedpeople do not normally tell everythingabout themselves and that too to a personwho is meeting them for the first time.But Ashk wanted to say so many thingsto me. It was good that he found me,otherwise he would have talked to thewalls, unburdened himself before the lamppost on the street. …Till then it waspast midnight. The dust had settled, butthe sky hadn’t cleared yet. At some places,a star in its keenness to show off hadstarted displaying its twinkling beauty,piercing through the layers of fog, dustand smoke. While listening to Ashk, Isometimes laughed and sometimes myeyes brimmed with tears. ...Now I hadbegun to feel a bit bored. The thoughtthat Satwant—my wife—would be waitingfor me at home also crossed my mind.Until convinced that he is a wanderer,every woman dispatches some horsesafter her husband. Some of them turnout to be asses, and among them wasa relative of mine who was sent to lookfor me. Ashk came down to give mecompany for some distance so as tosee me off. He couldn’t go far for hehad taken off his dhoti-kurta and changedinto his undershirt and tahband 6 afterhe had reached his home. But lettingoff squibs of talk, we came out of thebig market of Anarkali and emerged infront of Church Society, and from thereto Mall Road… towards my home… Aswe reached Golbagh, the same relativeof mine passed by us, singing (as wecame to know afterwards):Chitthiye dard firaq waliye34 :: July-September 2010