Language disadvantage and dyslexia - Dyslexia International

Language disadvantage and dyslexia - Dyslexia International

Language disadvantage and dyslexia - Dyslexia International

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Language</strong> <strong>disadvantage</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>dyslexia</strong>The development of skills, highlighting thegains to be made in cognition, <strong>and</strong> throughoutthe curriculum from multisensory teachingDr Harry Chasty, 2012

ContentsAbout the author 6Introduction 91The importance of language skills 112<strong>Language</strong>s <strong>and</strong> the incidence of <strong>dyslexia</strong> 12Evolution of languages 12Pace of phonetisization 15Extent of phonetisization 16Historical perspective: <strong>dyslexia</strong> first identified in the English language 17Phonological <strong>dyslexia</strong> as an acceptable world model of congenital readingfailure 18Phonologically ‘simple’ languages <strong>and</strong> the incidence of <strong>dyslexia</strong> 19<strong>Dyslexia</strong> in logographic languages 21Speech structures <strong>and</strong> reading failure 24The child’s synthesis of grammatical rules 25Idiosyncrasy of meaning from language 26Class differences in language usage 28Meaning from grammatical structure 29<strong>Language</strong> for representation of ideas <strong>and</strong> thought 30Causes of literacy failure 33Literacy failure <strong>and</strong> language <strong>disadvantage</strong> 332

ContentsCausality <strong>and</strong> literacy 34Prediction of reading attainment 35<strong>Language</strong> comparisons 35Incidence of deprivation in Europe 36Effects of deprivation <strong>and</strong> <strong>disadvantage</strong> 37Is increased criminality the inevitable outcome? 38Some positive effects of mothers working 39Quantifying language deprivation 40Cognitive/phonological difficulty 41Word reading competence index 41Deficiencies in learning or teaching? 423Deprivation, <strong>disadvantage</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>dyslexia</strong>; similar in form <strong>and</strong> treatment 45Causes of educational difficulties in language <strong>disadvantage</strong>d students 46<strong>Language</strong> <strong>disadvantage</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>dyslexia</strong> 47Differences between language-<strong>disadvantage</strong>d <strong>and</strong> dyslexic students 48Are total literacy expectations unreasonable? 48Historical perspectives 49Abilities <strong>and</strong> difficulties of the language-<strong>disadvantage</strong>d 51Speech <strong>and</strong> brain dominance 51Hemispheric specialism in normal children 53Test comparisons between normal <strong>and</strong> dyslexic students 54<strong>Language</strong>-advantaged <strong>and</strong> <strong>disadvantage</strong>d children 54Neurological differences in <strong>dyslexia</strong> 55Effects of <strong>Language</strong> development programmes 55Questions for further research 564Value of focused programmes to develop students’ skills 58Using educational resources efficiently 58Economic background 58Efficient use of educational resources 60Allocation of time 613

Contents5Accuracy of definition 646Confusions in terminology 64Development of definitions 65Other factors related to definitions of <strong>dyslexia</strong> 67Ongoing assessment 69Changing ‘static <strong>dyslexia</strong>’ into ‘dynamic <strong>dyslexia</strong>’ 70<strong>Dyslexia</strong> as a neurological condition 71Psychological assessment 737Profiles from psychological assessment 73Different kinds of thinking/problem solving evident in dyslexic profiles 74Implications of these profiles for identification <strong>and</strong> remediation of sub-types of<strong>dyslexia</strong> 75Other reading failing students with competent word recognition but poorcomprehension skills 77School history, cognitive <strong>and</strong> literacy profile of a student with ‘late onset<strong>dyslexia</strong>’ 78Special educational programmes should be directly focused to meet identifiedneeds 80The need for ‘value added’ 80Motor skills leading to aks linkages 81Speech skills 84Numeracy 86Memory 90Testing memory skills 90Working memory problems 93Perception 96Perception can be a very inefficient process 96The reading failing student’s different learning/thinking strategies in workingmemory 98Deficits in working memory 99Teaching memory skills 1004

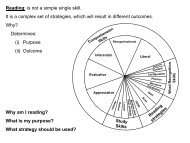

ContentsEffective working memory skills 101Social <strong>and</strong> behavioural skills 103Complex social problems 104Different aspects of working memory 106Working memory <strong>and</strong> literacy skills 1078Structured multisensory programmes 111Metacognitive control <strong>and</strong> multisensory learning 111Principles of multisensory teaching 113Reading in a wider context 115Metacognition – the key to learning to learn 117Use of talents 118Improving cognition <strong>and</strong> examination performance 118Metacognition is a shared responsibility 119Overall Conclusions 122Postscript 127Literacy is for life … <strong>and</strong> work 127Glossary 129Bibliography 1355

About the authorDr. Harry Chasty has been a teacher, Principal Teacher of a local education authorityprimary school in a deprived area, <strong>and</strong> Head of one of the largest <strong>and</strong> most importantpreparatory schools in Irel<strong>and</strong>. Stemming from his interest <strong>and</strong> practical experience inthe development of child language <strong>and</strong> literacy skills, he held a research fellowship inthe Department of Psychology at Queen’s University, Belfast, UK, where he establishedthe relationship between the development of child language, <strong>and</strong> preferences in visual/verbal problem solving, leading to strengths <strong>and</strong> weaknesses in the acquisition of literacy.In 1978, he was appointed Professional Director of the <strong>Dyslexia</strong> Institute, UK. There heset up <strong>and</strong> developed the national psychological assessment <strong>and</strong> teacher-training provisions.For some years he was Chair of the British <strong>Dyslexia</strong> Association’s <strong>International</strong>Conference Committee. He also led in the establishment <strong>and</strong> validation of the bda’snational specialist teaching diploma. For this work he was awarded an honoraryA.M.B.D.A. He was a founder member of the Council for the Registration of SchoolsTeaching Children with <strong>dyslexia</strong>, <strong>and</strong> established its school visiting <strong>and</strong> classificationprocedures. He was Consultant Psychologist to several first rank English independentschools, carrying out all the psychological assessments, training the teachers, advisingon the teaching programmes, <strong>and</strong> monitoring <strong>and</strong> reporting on student progress forparents <strong>and</strong> the school.He has wide experience in education across Europe, working with teachers <strong>and</strong>psychologists in Belgium, Irel<strong>and</strong>, Israel, Italy, Norway, Scotl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Sweden. He haswritten many articles <strong>and</strong> books, <strong>and</strong> has been a frequent contributor to conferenceson <strong>dyslexia</strong>. In a paper given at the World <strong>Dyslexia</strong> Forum at unesco, Paris, 2010, hereviewed the use of multisensory teaching procedures worldwide, <strong>and</strong> set out guidelinesfor more effective literacy teaching for dyslexic students.This paper builds on that presentation, taking a classroom rather than psychologicalresearch stance, to advance a forward-looking <strong>and</strong> practical perspective on readingfailure <strong>and</strong> <strong>dyslexia</strong>, initially examining the structures <strong>and</strong> processes of languageitself, to identify aspects which present particular difficulties to both dyslexic <strong>and</strong>language-<strong>disadvantage</strong>d students. Worldwide variability in the incidence <strong>and</strong> symptomsof reading failure across shallow/deep orthographies is linked to the ease/difficultywith which the essential ‘vaks’ linkages are established across these language categories.The inter-relationship between language <strong>disadvantage</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>dyslexia</strong> is explored.6

About the authorThe efficiency of multisensory teaching methods is considered in detail, reading skillsgains are documented <strong>and</strong> compared with progress made by dyslexic students in theirprevious class teaching. Firm recommendations are made for achieving the maximumskills gain at a minimum cost of provision.In teaching reading skills, the need for multisensory teaching will be stressed, not justas an end in itself to develop literacy but also to make associations, allow skills transfersto improved cognitive competences resulting in more effective performance in thewhole curriculum.Detailed programmes for facilitating the development of working memory skills inchildren with <strong>dyslexia</strong> are discussed; the wide-ranging effects of the failure to developautomaticity in a range of developmental skills is advanced as the central core difficultyin <strong>dyslexia</strong>. The need to enable reading failing students to develop metacognitive controlover all the skills of learning is highlighted.7

Acknowledgements<strong>Dyslexia</strong> <strong>International</strong> is grateful to Matthew St<strong>and</strong>age, Alex Edwards <strong>and</strong> Dr RobertBanham, of The Department of Typography & Graphic Communication, University ofReading, UK, for the preparation of this document.8

IntroductionFine words do not obviate school failure, nor the need forbasic teacher training.Despite the fine words from international <strong>and</strong> national bodies about the worldwideequality of educational opportunity, without basic teacher training in managing theeducation of students with language <strong>disadvantage</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>dyslexia</strong>, far too many studentsare failing in our schools. The daunting size of this failure is reflected in the arrestingstatistic given by unicef, that nearly a billion people entered the 21st century unableto read a book or sign their name, <strong>and</strong> two thirds of those illiterate world citizens werewomen. With the world population in 2000 being just over 6 billion, almost 17% of theworld population are illiterate <strong>and</strong> need literacy help.In the past, I have been a strong advocate for the need to identify <strong>and</strong> offer specialistteaching to all dyslexic students. This was necessary to counter the regrettable attitudeadvanced in some educational <strong>and</strong> political organizations that dyslexic students wereactually ‘stupid middle-class children.’ But as a former head-teacher who has kept a closeeye on educational developments worldwide, I have become increasingly concernedby the huge number of students, whether dyslexic or not, who fail in their educationsystem because they lack the lack the language <strong>and</strong> literacy skills required to workeffectively with the learning experiences provided there, <strong>and</strong> go on to swell the unicefilliteracy statistic quoted above. Consequently, I have given further thought to the kindsof problems faced by dyslexics <strong>and</strong> also those whose literacy failures are attributable tolanguage <strong>disadvantage</strong>, or the more modern attribute, language learning impairment.If we take an overview of causation, it is apparent that literacy failure results from interactionsbetween (i) limitations in the learner’s language background reinforced by poorcarer mediation; (ii) student cognitive difficulties, <strong>and</strong> (iii) teachers’ often idiosyncraticpresentation of literacy skills, <strong>and</strong> curriculum information.It is my opinion that there are similarities in the neurological, cognitive, <strong>and</strong> specialeducational needs underlying the language, literacy, <strong>and</strong> curriculum failures of language<strong>disadvantage</strong>d, language learning impaired, <strong>and</strong> dyslexic students, <strong>and</strong> in theclassroom, these similarities are much more important than differences, in determiningthe essential skills development programmes these students require. The supportingevidence for this will be presented later in this paper.In the practical background of the busy classroom, the teacher must be encouraged todeal quickly <strong>and</strong> effectively with literacy failure, whatever the causality, <strong>and</strong> without9

Introductionmaking ‘elitist’ distinctions between literacy failure arising from congenital cognitivefactors, <strong>and</strong> those arising from environmental factors in socioeconomic <strong>disadvantage</strong>.Whatever the causality, if untreated, the effects of these difficulties can be catastrophic,leaving the student totally out of touch with the learning process <strong>and</strong> their schoolcurriculum. In these challenging circumstances one must ask, in the United NationsLiteracy Decade, what do the inspiring unesco policies of Education for All, QualityEducation, <strong>and</strong> Inclusion really mean for the literacy failing student? Equally, whatdoes a national government’s stated policy of entitlement to a full national curriculumreally mean for the student failing in reading? Without basic training for all teachersin ordinary classrooms in what these difficulties entail, <strong>and</strong> what to do about them, thesuccinct answer to this question must be ‘Not a lot!’Whilst it may be agreed by everyone that such a basic training programme is necessary,in no sense is this paper intended as an essential initial training for class teachers.Those seeking such a programme will find it in <strong>Dyslexia</strong> <strong>International</strong>’s course, Basicsfor teachers: <strong>Dyslexia</strong> — How to identify it <strong>and</strong> what to do, directed by Dr. Vincent Goetry,the applicability of which goes much beyond the confines of <strong>dyslexia</strong>. (Ministries ofEducation are invited to contact <strong>Dyslexia</strong> <strong>International</strong> in order to access the course.)This paper aims to acquaint teachers who know something of reading failure, <strong>dyslexia</strong><strong>and</strong> the relevant assessment <strong>and</strong> literacy teaching methods with further details whichwould not be included in a basic training programme. Whilst mention will be madeof structured multisensory methods in developing literacy, the focus will be on usingstructured multisensory techniques derived from language learning in order toovercome the cognitive deficits underlying language <strong>disadvantage</strong>, language learningimpairment <strong>and</strong> <strong>dyslexia</strong> which interfere so significantly with the dyslexic student’swork in all the subjects of the school curriculum.Teachers must underst<strong>and</strong> the different learning styles which children with language<strong>disadvantage</strong>/impairment/<strong>dyslexia</strong> bring to the acquisition of language, literacy <strong>and</strong> thecurriculum <strong>and</strong>, building on this, as the title suggests, enable students with these difficultiesto learn how to learn <strong>and</strong>, in doing so, to monitor, control <strong>and</strong> eventually direct theirown learning.What is important in this paper is not solely the identification <strong>and</strong> amelioration of theparticular complexities of phonological <strong>dyslexia</strong>, but underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>and</strong> providing forthe worldwide commonalities of the hereditary, environmental <strong>and</strong> pedagogic factorscontributing to the developing science of reading failure. The intention is to provide awider, more inclusive perspective on language <strong>disadvantage</strong>, literacy failure <strong>and</strong> <strong>dyslexia</strong><strong>and</strong>, in the light of recent research, pose questions arising from personal observation<strong>and</strong> experience for others to consider, follow up, <strong>and</strong> perhaps, after research <strong>and</strong> discussion,find more definitive answers.Note: ‘he’/‘his’ also refers throughout to ‘she’/‘her’s.’10

The importance oflanguage skillsChapter 1The importance of language skillsRegardless of the competences <strong>and</strong> preferences in representing <strong>and</strong> manipulating ideaswhich the student brings to learning in school, language <strong>and</strong> literacy skills are essentialfor success in education. We will leave ‘language <strong>disadvantage</strong>’ <strong>and</strong> ‘language learningimpairment’ for later consideration <strong>and</strong> start by looking at the concept of <strong>dyslexia</strong>.Whilst this will be reviewed in some detail later in this paper <strong>and</strong> full definitions of alltypes will be given, analysed, <strong>and</strong> directly linked to the profile observed from ongoingpsychological assessment, at this early stage in our considerations it is proposed that wefocus on the form of <strong>dyslexia</strong> most frequently observed in the English language, <strong>and</strong>use the description given in the Glossary.<strong>Dyslexia</strong> is a different learning style, which is less effective within a verballybiased,literacy-based education system, but more effective within a visually/practically based working/thinking paradigm.Whilst in the previous sentence referring to a visually/practically based educationsystem would have given a satisfying balance, this even-h<strong>and</strong>edness is impossiblebecause such a system does not exist. The education process is staffed, designed, operated,maintained, inspected, <strong>and</strong> reviewed by skilled verbal practitioners, who have beensuccessful examination passers, but are not particularly adept at the presentation ofessential information in visual/practical terms, nor do they really underst<strong>and</strong> the needfor always offering that option as an alternative.At the beginning of the education process reading is the first major skill area to beacquired. Throughout the education process competent st<strong>and</strong>ards in speech <strong>and</strong> literacyare required. At the conclusion of this education process, students must pass verballypresentedexaminations, which require high levels of literacy skill. It is evident thatchildren with language <strong>disadvantage</strong>/<strong>dyslexia</strong> must learn, operate <strong>and</strong> be judged, pass/fail, within a school system which by its inherent nature <strong>and</strong> structure is biased againsttheir preferred thinking <strong>and</strong> information processing systems.For them, education is not about skillfully applying their preferred cognitive strategies,but about developing other options <strong>and</strong> approaches more in keeping with the establishedverbal system required in the education process with consequent losses in theiruse of visual representation <strong>and</strong> creativity. Evidence to support this will be offered later11

The importance oflanguage skills 1in the paper. It is not surprising that some of these students become frustrated, <strong>and</strong>give up the struggle to communicate within what seems to them to be an alienschool system.<strong>Language</strong>s <strong>and</strong> the incidence of <strong>dyslexia</strong>Before looking at the problems language <strong>disadvantage</strong>d <strong>and</strong> dyslexic students experiencewhen learning literacy, the systems <strong>and</strong> structures of languages themselves mustbe considered to identify elements which will cause difficulties to less skillful auditory/verbal learners. Is the incidence of <strong>dyslexia</strong> consistent across all languages? Do studentswho are dyslexic in English show exactly the same symptoms as those who are dyslexicin German or Spanish? Do students who have been identified as dyslexic in Englishalways show the same symptoms in cognitive <strong>and</strong> literacy development? How do thevarying visual symbol-sound-meaning systems <strong>and</strong> structures of world languages affectthe incidence <strong>and</strong> forms of <strong>dyslexia</strong>? Do these structures present particular difficultiesto some learners <strong>and</strong> not to others? If so, why? These questions are important <strong>and</strong>in considering these matters later in this paper, the points raised are relevant to theEnglish language but other languages worldwide will present a lesser or greater range ofdifficulties. This variability in the onset of <strong>dyslexia</strong> <strong>and</strong> the symptoms observed acrosslanguages worldwide will be discussed in the next section.Evolution of languages<strong>Language</strong> is a system of signs for encoding <strong>and</strong> decoding information. <strong>Language</strong>s haveevolved over a period of more than 100,000 years. They live, die, move from place toplace, change in structure <strong>and</strong> form with time, <strong>and</strong> when they cease to change are ‘dead.’It has been estimated that across the history of mankind as many as 500,000 languageshave existed, but at the last count, only 6,909 remain <strong>and</strong> half of these are threatenedwith extinction. With rapidly growing educational sophistication <strong>and</strong> increasingly fastworldwide communication, language diversity is diminishing with only some twentyimportant languages covering almost the entire world population. The most frequentlyspoken language is Chinese, with Hindi second, Spanish third, <strong>and</strong> English fourth.Because English is frequently used by speakers of other languages as a second languagechoice, it has greater world importance than its fourth place would suggest, but it shouldnot be forgotten that it is far from being the major world language. Reading researchwhich is based solely upon the English language, <strong>and</strong> advances in theories of readingbased solely upon the development of limited skills at the earliest stages of reading inEnglish (Anglocentricity) should be questioned for their relevance to all major languages.Spoken language takes the priority in man’s evolution, <strong>and</strong> also comes first in the developmentof the child. It has a complexity <strong>and</strong> carries information not readily reproduciblein other language forms such as print. The human speech apparatus can produce anenormous variety of sounds. No language uses anything like the full range. Each usesa small set of basic sounds called phonemes. Across all spoken languages worldwide thenumber of phonemes used varies from 15 to 85. English uses 45. These phonemes maybe used to represent words in a range of ways from very simple to very complex.In phonetic languages such as English, phonemes do not convey meaning. In English(but not all languages), meaning comes from patterned, organized sounds which make12

The importance oflanguage skills 1words. The sounds ‘p’, ‘a’, <strong>and</strong> ‘t’ can be used in different orders to make ‘pat,’ ‘tap,’ ‘apt.’Whilst the constituent sounds used are the same, the sound sequences are different<strong>and</strong>, in each case, the meaning is very different. It is the order of the sounds leading tothe organized pattern comprising the word which conveys the meaning. The languagelearner must therefore be sensitive to the sequential order as well as the nature ofthe sound.Phonology is the study of the sound system of a particular language, <strong>and</strong> how thesounds are organized to make words <strong>and</strong> give access to the meaning. It includes aninventory of the sounds, their features, <strong>and</strong> the rules, which may range from verysimple to extremely complex, specifying how these sounds interact with each otherin that language to form words <strong>and</strong> convey meaning.For many thous<strong>and</strong>s of years, mankind lived, thrived, <strong>and</strong> peopled the earth, withoutthe communication system provided by language. The problem with inter-personalspeech is that it is not recorded, <strong>and</strong> memory, which can be very fallible, is the onlyregister of the expressed meaning. Although there are recorded instances of veryimportant events/stories being carried in tribal collective memory for many centuries,for example Plato’s Atlantis, more complex material needed to be recorded. With increasingreligious, technological <strong>and</strong> social sophistication, there was a developing need forlanguage to facilitate the expression <strong>and</strong> recording of ideas. Consequently, languagebegins in the necessity to document information for others. Important events in thetribe’s history, key skills, techniques, procedures, predictions about coming events,the form of religious ceremonies, which had to be passed down to future generations,needed to be recorded.Anthropology has established that in these earliest stages of language development, themode of representation was always visual. Though initially local, <strong>and</strong> particular to atribe or nation, this visual representation could be just as meaningful to the Europeanwho viewed it centuries later as it was to the Aztec who made it. While speech was lostas soon as its trace was eliminated from memory, visual representation had the greatadvantage of conveying information clearly across cultures <strong>and</strong> down many generations.Figure 1The expedition of Myeengun<strong>Language</strong> can exist without speech, <strong>and</strong> visual representation can provide the structurefor a language. An example of the visual recording of information for the tribe <strong>and</strong>posterity is shown in Figure 1. This painting was engraved on a cliff near Lake Superior,13

The importance oflanguage skills 1Canada. It depicts an important expedition undertaken by Chief Myeengun. Beforereading the verbal description in the following paragraph, look at the picture, turn backto this page <strong>and</strong> then answer the following questions, treating this as a visual comprehensionexercise. Think about whether you answered directly (from visual memory) orwhether you had to keep looking back at the picture to use verbal systems ineffectivelyto answer visual problems. Such an approach would greatly reduce your efficiency <strong>and</strong>increase your response times (just like a child with <strong>dyslexia</strong> inappropriately using visualskills when reading a complex verbal script).How many warriors were in the second canoe?How many warriors were in the fourth canoe?Who comm<strong>and</strong>ed the leading canoe?How long did the expedition last?How do you know that the expedition came safely to l<strong>and</strong>?How do you know that the warriors behaved courageously?Now let us consider, in words, the meaning conveyed by that picture. Five canoeswere used to carry, in the first sixteen men, in the second nine men, in the thirdten men, in the fourth <strong>and</strong> fifth eight men. The leading canoe was comm<strong>and</strong>ed byKishkemuncsee whose totem sign is above it. The three suns shown under the vaultof the sky on the right h<strong>and</strong> side confirm that the expedition took three days. Theman on horseback on l<strong>and</strong> is the maker of magic whose skills facilitated the successof the expedition. The l<strong>and</strong> tortoise in the centre shows that the warriors came safelyto l<strong>and</strong>. The eagle on the left symbolizes the courage the men showed. The monstrouscreatures at the bottom were invoked to lend their aid.This picture is certainly ‘worth a thous<strong>and</strong> words,’ conveying much information veryeconomically in a way which most children with language learning impairment/<strong>dyslexia</strong> would readily underst<strong>and</strong>, but verbally skillful expert grammarians mightstruggle to appreciate the deep meaning. How well did you do? Were you a 2 correctout of 6, mediocre visual comprehender, or a 5 correct out of 6, visual star? How wouldyou make out if your future depended upon your visual skills?Whilst in the development of Homo sapiens, the processing of recorded informationbegan in the visual dimension; using systems similar to those shown in the depictionof Chief Myeengun’s expedition, over a lengthy period of time language representationmoved from visual to verbal. This modality shift has been observed <strong>and</strong> confirmedby anthropologists across the range of major ‘civilizations,’ Aztec, European,Egyptian, Indian, Japanese, Mayan, Mesopotamian. Despite visual channel dominancein everyday human relationships, natural selection/heritability favours the auditoryverbalchannel.If the development of the language form associated with one of the civilizations listedabove is followed historically, the language begins in the pictographic/logographicform, with the language signs (graphemes) directly representing ideas. Graphemesare not linked to the auditory form required for pronunciation <strong>and</strong> a ‘reader’ does notneed to know the sound required for pronunciation to underst<strong>and</strong> the meaning. Apurely logographic script was simple, direct, but educationally impracticable becausewith developing sophistication of language content, the increasingly large numberof logograms used had to be memorized by rote, which presented great difficulties tothe learner.14

The importance oflanguage skills 1The move to ‘phonetisization,’ with the visual symbols representing language sounds,which could be synthesized into words required an extension of the auditorykinaesthetic-semantic(aks) system used for speech to the more cognitively complexvisual-auditory-kinaesthetic-semantic (vaks) modality linkages required for the writtenlanguage form.Mastery of the vaks language system is absolutely essentialfor competent reading.Pace of phonetisizationIn this process of linguistic evolution worldwide, variations in the pace <strong>and</strong> extent of theprocess of phonetizisation have important cultural <strong>and</strong> learning consequences.In most civilizations the development of phonetisization was a very gradual evolutionover many centuries, from shape representing a large, diffuse sound chunk, throughthe stage where the shape represented a much smaller more precise unit of sound, tothe final stage, where the shape represented a range of possible sounds, with the actualrepresentation being determined by syntactic, semantic <strong>and</strong> pragmatic language factors.The stages in this process are described as phonemes representing a:1. Sentence2. Word or phrase3. Syllable4. Sound5. Range of possible soundsThese changes were usually driven by educational <strong>and</strong> linguistic pressures from withinthe culture using that language, <strong>and</strong> over time led to notable cognitive <strong>and</strong> educationalbenefits. The relatively slow pace of development facilitated the preservation of culturalstability <strong>and</strong> integrity, <strong>and</strong> enabled the establishment <strong>and</strong> appreciation of a culturalliterature linked to increasing st<strong>and</strong>ards in literacy.Because of pressures from incoming societies with competing cultures, other languagesmoved from the spoken form to print extremely quickly. An example of this is the Maorilanguage, which was originally a spoken language <strong>and</strong> had no visual or written representation.This language system was entirely appropriate for spoken communicationwithin the tribe/family, <strong>and</strong> to facilitate the simple practical education system necessaryto teach growing children the skills required for adult life in that culture.However, in 1815, visiting English missionaries drew up a Maori lexicon, listing thewords they heard, using an English sound-symbol representational system. Later, in1824, using English university resources, a grammatical structure for the spoken Maorilanguage was drafted. The rationale behind this activity was to enable the missionariesto communicate more effectively with the Maori people <strong>and</strong> to develop their knowledgeof Christianity much more rapidly. The pressure from competing missionary groupswas so intense that within a few years 40,000 religious books in this extended Maorilanguage form were being printed each year in Northl<strong>and</strong>, New Zeal<strong>and</strong>. Whether15

The importance oflanguage skills 1reading in this precipitately extended Maori language developed equally quickly to takeadvantage of these ‘opportunities’ is not recorded <strong>and</strong> is very questionable.The current Maori language is therefore a recent, externally-motivated construct,deliberately created to bring about rapid cultural <strong>and</strong> religious change. With thewisdom of almost two centuries’ hindsight, the lack of appreciation by the Europeanmissionaries of the full effects of their actions would certainly be questioned byMaori cultural activists. Yet it must be said that by deliberately adding the visual <strong>and</strong>kinaesthetic orthographic elements to the pre-existing phonological/semantic languagestructure the questionable cultural effects were balanced to some extent by the resultingpositive cognitive representational benefits. For the Maori generations which followedthe availability of a visual-auditory-kinaesthetic-semantic representational system facilitatedthe possibility of equality within the national, verbally-based English languageeducation system.Extent of phonetisizationThe extent of phonetisization of languages affects the nature, frequency of occurrence<strong>and</strong> point of incidence of <strong>dyslexia</strong> along the speech-language literacy continuum.Some phonetic languages developed to stage 5 (described above), which required a highlevel of phonological complexity, but others remained at stage 2, 3 or 4. Across phoneticlanguages worldwide, there are therefore, marked variations in the complexity/obscurityof the links between the visual symbol <strong>and</strong> the sound it conveys. Those with simple,direct links are easy to learn to read, show a later incidence of reading failure in learners,<strong>and</strong> a reduced incidence of <strong>dyslexia</strong>. However those with more complex <strong>and</strong> obscurelinks are harder to learn to read, show a much earlier incidence of reading failure inlearners, <strong>and</strong> an increased incidence of <strong>dyslexia</strong>. The English language is consideredto be amongst the most phonologically complex <strong>and</strong> difficult languages, so an earlyincidence of reading failure at the phonology word recognition stage, <strong>and</strong> an increasedfrequency of <strong>dyslexia</strong> may be anticipated in this language.Frost et al. (1987) classified orthographies according to phonological complexity asshallow or deep. ‘In a shallow orthography ... the phonemes of the spoken word are representedby the graphemes in a direct <strong>and</strong> unequivocal manner. In contrast, in a deeporthography, the relation of spelling to sound is opaque. The same letter may representdifferent phonemes in different contexts, moreover different letters may represent thesame phoneme.’Seymour et al. (2003) further developed this shallow/deep classification process byadding, as a second dimension, a measure of syllabic complexity ranging from simpleopen syllables to closed cvc (consonant, vowel, consonant) syllables, <strong>and</strong> frequent initial<strong>and</strong> final consonant clusters. This revised system was used by Seymour’s research teamto classify thirteen European languages according to the difficulty presented to readinglearners, with Finnish being simplest, <strong>and</strong> English the most complex. Later, Seymour(2005) demonstrated the clear links existing between levels of language difficulty, ageof reading skills acquisition, <strong>and</strong> error rates in reading tasks.Across all languages worldwide, depending upon the simplicity/complexity of the linksbetween the shape seen, the sound conveyed, the movement pattern to say or write16

The importance oflanguage skills 1it, <strong>and</strong> the implicit meaning, there will be differences in the stage of onset of readingdifficulty <strong>and</strong> the types of reading problems experienced by literacy learners. There istherefore, no single worldwide form of reading difficulty observed in <strong>dyslexia</strong>.This system of classifying languages according to their phonological/orthographiccomplexity opens the possibility of quantifying the level of difficulty presented toliteracy learners by a particular language <strong>and</strong> so facilitates the calculation of probableearly reading difficulty figures within that language. This will be considered in somedetail at a slightly later stage in this paper.Historical perspective: <strong>dyslexia</strong> first identified in the English languageBecause of its extremely deep orthography <strong>and</strong> complex phonological structure, itis only to be anticipated that it was in English that <strong>dyslexia</strong> was first identified <strong>and</strong>described. <strong>Dyslexia</strong> was regarded as a phonological problem with the difficulty beingseen, initially, in the learner’s ability to tune into <strong>and</strong> manipulate the sounds of hislanguage, <strong>and</strong> at a slightly more mature stage, in connecting those sounds to the letteror word shapes to develop word recognition skills for reading. This led to a searchinganalysis of phonological awareness in reading learners, an area of study which quicklyachieved high prestige status in psychological research into reading failure. Though it isonly in the last forty years that ‘phonological awareness’ has become so popular, someof the ideas have been around for many centuries. In the fourth book of De RerumNatura by Lucretius (1 st century bc), key issues of the relationship between phonology<strong>and</strong> semantics are raised: for example, ‘And so it haps that thou canst sound, perceive,yet not determine what the words may mean.’Vellutino (1979) reviewed the available literature on phonological difficulty <strong>and</strong> readingfailure in English. He concluded that <strong>dyslexia</strong> was characterized by weakness in phonological,semantic <strong>and</strong> syntactic aspects of language processing, <strong>and</strong> verbal memory.These views were extended <strong>and</strong> developed in a more recent study, Vellutino et al. (2004),which provides a very detailed <strong>and</strong> authoritative exposition of phonological <strong>dyslexia</strong>in English. This survey of the literature over a forty year period is very strong on theimportance of phonological awareness leading to linguistic coding competences, <strong>and</strong>is firm on the causality of reading difficulties.‘Specific reading difficulty (<strong>dyslexia</strong>) in otherwise normal children has been <strong>and</strong> continuesto be defined as a basic deficit in learning to decode print.’ And again, ‘There isabundant evidence that difficulty in learning to identify printed words is the manifestcause of difficulties in beginning readers, there is also abundant evidence that thisproblem itself is causally related to significant difficulties in acquiring phonologicalanalysis skills <strong>and</strong> mastering the alphabetic code.’But Vellutino et al. does not offer the same detailed insights into the next stage of theprocess of learning to read, how the auditory competences in linguistic coding areeffectively linked to visual coding to provide the word recognition skills which havebeen acknowledged to be deficient <strong>and</strong> are accepted in the reviewed literature as thecause of reading failure. ‘Linguistic <strong>and</strong> visual coding processes together facilitate theestablishment of firm associations between the spoken <strong>and</strong> written counterparts ofprinted words, in the interests of helping the child acquire a sight vocabulary.’ Teachers17

The importance oflanguage skills 1who have worked very long <strong>and</strong> hard with their dyslexic students on the carefullystructured ‘reading pack,’ that is look at the letter shape, then say the key word with itssound, <strong>and</strong> spelling pack, that is listen to the sound, now say it <strong>and</strong> drills to write it, willsmile wryly at the assertion that ‘linguistic <strong>and</strong> visual processes together facilitate theestablishment of firm associations …,’ <strong>and</strong> wish it were that simple, easy <strong>and</strong> seeminglyautomatic in the special education classroom.Phonological <strong>dyslexia</strong> as an acceptable world model of congenitalreading failureCriticisms of the directions taken in this work have been growing recently. Whilethe authority <strong>and</strong> accuracy of Vellutino et al.’s observations of the research literatureover the last half century are not questioned, teachers must look searchingly at thevery limited language sample (Anglocentricity) in that research, <strong>and</strong> should also beconcerned about the limited definitions of reading used by the researchers. Whilethey defined reading as ‘the process of extracting <strong>and</strong> constructing meaning fromwritten text for some purpose,’ generally across the research surveyed, reading isregarded as word recognition. These factors lead to a narrow definition of <strong>dyslexia</strong>(quoted two paragraphs above) <strong>and</strong> result in the formulation of research groupsheavily loaded with a particular type of dyslexic student. This results in a limited perspectivebased upon ‘early onset <strong>dyslexia</strong>’ as observed in a phonologically extremelydeep orthography which may be misleading when viewed from the wider internationalfield.Reading is not just recognizing <strong>and</strong> saying the names of words. It is about the extraction,storage, recall <strong>and</strong> effective use of the meaning of continuous text. Nor shouldany single sub-skill of reading be detailed as being more important than the others,or regarded as a ‘st<strong>and</strong> alone’ entity. Each sub-skill is an integral part of a very muchmore complex process described in detail later in this paper. The establishment of aparticular sub-skill should be achieved in a way which, at the succeeding stage of thestudent’s development, facilitates the construction of the next skill in the hierarchy,<strong>and</strong> ensures the effectiveness of the operation of the whole schema, minimizing theloading it places upon working memory.Clearly, in learning to read, the child must establish effective links between his visualcoding competences, <strong>and</strong> his phonological linguistic competences, so that the unitsof sound which comprise the syllable or word are recognized <strong>and</strong> said. There mustalso be an effective link to the semantic aspects of the visual symbol so that the childhas access to the meaning of the text, a requirement which is largely neglected in theliterature surveyed by Vellutino et al. At a slightly later stage, in literacy development,the motor movement patterns for saying the sound <strong>and</strong> writing the word must beintegrated into this evolving structure, so that language-reading skills facilitate writing<strong>and</strong> spelling to express the learner’s meaning for others.Some practitioners would regard this as enabling the development of effective vakscross-modal transfers by using multi-sensory techniques, but such terminology seemsto be at odds with the views reported by Vellutino.However, more recent work by the Cross-Modal Research Laboratory in theDepartment of Experimental Psychology at Oxford University <strong>and</strong> similar facilities18

The importance oflanguage skills 1in other universities emphasize the importance of multi-sensory learning in theestablishment of cross-modal linkages in subjects experiencing a range of cognitivedifficulties.In attempting to make sense of these issues, we seem to have reached a stage of cognitivedissonance rather than a more constructive dialectic, as the difficulties seem to liemore in the concepts <strong>and</strong> language used by groups of researchers <strong>and</strong> teachers, ratherthan in the actual structures <strong>and</strong> processes of language-literacy learning. We mustreturn to this point later in our discourse but will leave the discussion with the appositecomment that if it had been held in Old Uzbek it would certainly have brought tearsto our eyes …Phonologically ‘simple’ languages <strong>and</strong> the incidence of <strong>dyslexia</strong>There is evidence that in phonologically simple languages dyslexics show a lowerincidence of phonological deficits <strong>and</strong> consequently a reduced incidence of deficienciesin word recognition skills leading to early reading difficulty. This is touched onby Vellutino et al. (2004). ‘The prevailing view is that the core phonological deficitsof <strong>dyslexia</strong> are ‘harder to detect’ in children who have learned to read in transparent(phonologically simpler) orthographies such as German or Italian.’The work of Wimmer, Mayringer <strong>and</strong> L<strong>and</strong>erl (1998) supports the view that in suchlanguages, impairments can be identified most clearly on tasks that require the evaluationof verbal short term memory, rapid automatized naming (ran) <strong>and</strong> visual-verbalpaired associate learning, rather than on tests evaluating phonological awareness <strong>and</strong>phonological (letter-sound) decoding. Wimmer et al. report that German speakingdyslexic students show generally competent word recognition skills but read moreslowly <strong>and</strong> later show reading comprehension difficulties. Students who are dyslexic inGerman, Spanish, Portugese, Finnish or Greek do not show the early phonological <strong>and</strong>word recognition difficulties which have been documented in the literature as such amajor part of <strong>dyslexia</strong> in English. But they generally show later developing difficultiesin higher literacy skills.The comparisons recorded by Philip Seymour <strong>and</strong> his associates across Europeanlanguages are striking. In transparent orthographies such as Italian, Spanish orGreek, few problems are presented by the language phonology to young readers. Moreopaque orthographies such as English, French, or Polish, which give precedence tomorphological level over phonological level, are more difficult for learners to manage,<strong>and</strong> phonological weakness <strong>and</strong> early word recognition difficulties in reading are muchmore prevalent.Seymour et al. found that children from the majority of European countries learningto read in languages which were phonologically ‘simple’ become accurate <strong>and</strong> fluent infoundation level reading before the end of the first school year, but children learningto read in the phonologically opaque English language are more than twice as slow.Fluency in English spelling, which requires knowledge of more than three times thenumber of graphemes as most European languages, retards literacy progress in thatlanguage still further.It therefore appears that despite dyslexic students’ consistent underlying cognitiveproblems in motor skills <strong>and</strong> working memory, in transparent phonological languages19

The importance oflanguage skills 1they can cope with the simpler, early developing literacy skills leading to word recognition,but later developing <strong>and</strong> more complex schema manipulation required in readingcomprehension, reading speed, spelling, <strong>and</strong> the written expression of ideas is impaired.Depending upon the inherent phonological complexity of the language being used forinstruction, the symptoms of <strong>dyslexia</strong> which teachers observe in the classroom willvary from language to language along the phonology-speech-literacy-verbal thinkingcontinuum, with dyslexic students learning in opaque phonological languages showingearly word recognition problems, <strong>and</strong> dyslexic students learning in transparentphonological languages showing problems in the later, more complex stages of literacyacquisition. It is apparent that the key concepts of phonological <strong>dyslexia</strong> as summarizedin Vellutino et al. (2004) do not transfer easily into <strong>dyslexia</strong> in other more orthographicallytransparent world languages, <strong>and</strong> especially not into logographic languages.Growing reservations about the worldwide applicability of the ‘<strong>dyslexia</strong> is difficulty inphonological awareness’ model have been expressed in the literature. Considering thecognitive psychological implications, Bishop <strong>and</strong> Snowling (2004) state: ‘We suggest thatthe overwhelming emphasis on phonological awareness in studies of reading disabilitymay be misplaced <strong>and</strong> that factors other than segmentation may be implicated in thedifficulties children have in mapping between orthography <strong>and</strong> phonology.’ And later,‘although most of the emphasis in studies of <strong>dyslexia</strong> has been on phonological awareness,we suggest that phonological memory may be a more fruitful skill to investigatewhen studying the phonological origins of literacy problems in <strong>dyslexia</strong> <strong>and</strong> sli.’Approaching the discussion from the point of view of genetics, Pennington (2006)commented: ‘The consensus about a core phonological processing deficit in <strong>dyslexia</strong> asdescribed in Vellutino et al. (2004) suggests a single cause of <strong>dyslexia</strong>. A probabilisticmulti-factorial model forms a better explanation for the heterogeneity than a deterministicsingle cause.’Ziegler <strong>and</strong> Goswami (2006), raise issues about the relevance of the extreme developmentof the phonological deficit model to reading failure in other languages: ‘Englishlies at the extreme end of the consistency continuum with regard to orthographyphonologyrelationships, it might be that some of the most sophisticated processingarchitecture (e.g. two separate routes to pronunciation in the skilled reading system)may in fact, only develop for English.’Much stronger reservations have been expressed by David Share (2008). In his critiqueof current reading research <strong>and</strong> practice, he contended that ‘the extreme ambiguityof English spelling-sound correspondence had confined reading science to an insularAnglocentric research agenda addressing theoretical <strong>and</strong> applied issues with limited relevanceto a science of reading. The unique problems posed by the ‘outlier’ orthographyhave focused disproportionate attention on oral reading <strong>and</strong> accuracy at the expense ofsilent reading, meaning access <strong>and</strong> fluency, <strong>and</strong> have significantly distorted theorizingwith regard to many issues including phonological awareness, early reading instruction,the architecture of stage models of reading development, the definition <strong>and</strong> remediationof reading disability <strong>and</strong> the role of lexical semantic <strong>and</strong> supra-lexical information inword recognition.’It is apparent that the ‘phonological awareness deficit’ so prevalent in psychologicalresearch into reading failure in the English language over almost half a century, is not a20

The importance oflanguage skills 1universal attribute of <strong>dyslexia</strong> worldwide. The ‘<strong>dyslexia</strong> is phonological difficulty leadingto failure in word recognition’ paradigm seems to be applicable only to the languagesat the extreme end of the orthographic depth-syllabic complexity dimension describedabove, <strong>and</strong> appears to relate to a significant minority of the world population.<strong>Dyslexia</strong> in logographic languagesFrom the literature it appears that <strong>dyslexia</strong> in logographic languages is different fromthe phonological <strong>dyslexia</strong> described by Vellutino et al. But how significant are theobserved differences? From the preceding section we have seen that it can be misleadingto reach hard conclusions about the universal applicability of differences in aspects ofsingle skills acquisition in the beginning stages of reading in a single language. Theobserved similarities <strong>and</strong> differences between <strong>dyslexia</strong> as observed across the range ofopaque phonological languages, transparent phonological languages <strong>and</strong> logographiclanguages must be carefully evaluated.In the development of modern Japanese, two language varieties, Kanji <strong>and</strong> Kana, havesurvived <strong>and</strong> are still used today. Kanji, borrowed from classical Chinese, is logographicwith the meaning being directly apparent from the graphemes. Kana, derived fromearly Japanese requires the reader to transfer the information conveyed by the graphemeinto the syllabic (sound) form to gain the meaning. In the research literaturethere is evidence of learners who are dyslexic in Kana, but not in Kanji. This suggeststhat: 1) students who are competent in a logographic/ideographic language could bemuch less competent in a syllabic language requiring very different initial cognitive/neurological processing systems, which did not suit their particular neurologicallydetermined abilities, <strong>and</strong> consequently, 2) worldwide, dyslexic students’ processing <strong>and</strong>representational problems in reading arise from the need to develop <strong>and</strong> apply effectiveinter-sensory vaks linkages to move incoming visual information from the page to thesemantic system in whatever order their language requires, through the auditory <strong>and</strong>motor dimensions, to say the words <strong>and</strong> access the meaning.Wydell <strong>and</strong> Butterworth (1999) reported on a bilingual English/Japanese student withmonolingual <strong>dyslexia</strong>. The complexity of the auditory, visual, kinaesthetic, <strong>and</strong> semanticlinks required by the phonologically opaque English orthography determined theincidence of symptoms of <strong>dyslexia</strong>. In the Japanese language form used these essentiallinks were much more easily established by their student. They concluded that in anylanguage where the transfer from the orthography to the phonology was simple orwhere the orthographic unit was either a word or a whole character there should not bea high incidence of phonological <strong>dyslexia</strong>.I have recently confirmed their findings when working with a seventeen year oldSouth African student. His primary language is Zulu, but he has also been educatedin Afrikaans <strong>and</strong> English. He is fluent in speaking his primary language, Zulu, butalso speaks English very well, if a little slowly. He reads Zulu competently but has greatdifficulty with reading in English. Testing showed that he was of at least average intellectualability but had marked auditory short term memory problems, <strong>and</strong> was dyslexicin English, but not in Zulu.As a language, Zulu has near perfect letter-sound correlation, <strong>and</strong> is at the ‘simple’ endof the phonological complexity dimension described above. Data is available which21

The importance oflanguage skills 1confirms that because of this very simple symbol-sound correspondence learners findZulu a relatively easy language to learn to read, with some 81% of Zulu first languagespeakers showing greater competence in reading Zulu than other languages. The establishmentby the learner of the necessary vaks linkages is relatively easy in Zulu, <strong>and</strong>could be managed by my student, even with his deficient auditory short-term memory.English is, however, a much more phonologically complex language. A clear exampleof this complexity is seen in the range of sounds <strong>and</strong> meanings conveyed by ‘ough.’ InEnglish, the essential links between the symbol shape, its sound, the movement patternnecessary to say or write it, <strong>and</strong> its meaning, are much more difficult to establish. Thisclarifies my student’s seemingly anomalous difficulties in reading English, but not Zulu.As Wydell <strong>and</strong> Butterworth (1999) predicted, my student was not dyslexic in the phonologicallysimplest language he spoke.The most frequently used logographic language, Chinese, has a pictographic writingsystem which uses a total of 20,000+ characters, giving learners an immense visualmemory task. Consequently, some researchers into <strong>dyslexia</strong> in Chinese have anticipatedthat Chinese reading failing students would show visual rather than phonologicalprocessing problems, but research has not fully supported this expectation.Ho, Chan, Tsang <strong>and</strong> Lee (2002) found that rapid naming deficit (ran) was the mostfrequently observed difficulty in their sample of Chinese dyslexic children, being evidentin some 60% of the students they studied. Most significantly, they observed that morethan 50% of their sample showed three or more cognitive deficits, <strong>and</strong> the greater thenumber of deficits the dyslexic child experienced, the more severe his <strong>dyslexia</strong> was.ran has been documented very frequently as a key deficit in <strong>dyslexia</strong>. (See the Glossary<strong>and</strong> the comments of Wimmer, Mayringer <strong>and</strong> L<strong>and</strong>erl already referred to on page 19.)ran deficit has been described in the literature as a failure of automatization of verbalresponses to visual stimuli (i.e. the visual-verbal link), <strong>and</strong> Denkla <strong>and</strong> Rudel (1976)confirmed that failure in this skill differentiated English-speaking dyslexic children fromnormal controls <strong>and</strong> non-dyslexic learning disabled children. It is interesting to note itssignificant place in identifying children who were dyslexic in the logographic Chineselanguage, <strong>and</strong> also in the phonologically transparent German language.Wai Ting Siok (2009), University of Hong Kong, used functional magnetic resonanceimaging to determine whether Chinese children with <strong>dyslexia</strong> had difficulty in comprehendingthe essential visual details of their logographic language. Siok reported thatin her Chinese dyslexic group, ‘Disordered phonological processing may commonlyco-exist with abnormal visuo-spatial processing.’ She observed that Chinese people with<strong>dyslexia</strong> seemed to experience both visual <strong>and</strong> phonological problems.Other researchers, using similar techniques, have compared English <strong>and</strong> Chinese childrenneurologically when learning to read. They identified different <strong>and</strong> more diversifiedleft hemisphere processing in competent Chinese readers.These observed differences in neurological organization suggest that Chinese childrendevelop a different cognitive structure for processing reading <strong>and</strong> that worldwide thereis a range of different neurological organizations underlying reading failure acrossall languages.22

The importance oflanguage skills 1Drawing attention to the differences she observed between her Chinese dyslexicstudents <strong>and</strong> English children with phonological <strong>dyslexia</strong>, Siok stressed the need for a‘uniform theory of sufficient scope to accommodate the full complexity of the observeddysfunctions <strong>and</strong> interactions of the brain systems underlying (all) reading impairments.’At the World <strong>Dyslexia</strong> Forum, unesco, February 2010, Professor Alice Cheng-Lai reportedon her research with Chinese children with <strong>dyslexia</strong> <strong>and</strong> age-matched controls competentin reading. Using ‘logistic regression analysis’ she established that deficiencies invisual <strong>and</strong> phonological skills did not fully distinguish Chinese children with <strong>dyslexia</strong>from competent readers. She considered that morphological awareness, i.e. the abilityto recognize <strong>and</strong> process the smallest component of the Chinese word which carriedmeaning (i.e. the link between the visual unit in print <strong>and</strong> its semantic implications)was the strongest predictor of reading ability.Professor Cheng-Lai described the differences between the first steps young Chinese<strong>and</strong> English learners take in their approach to reading. In English, the visual units(the letters) represent sounds which, organized in sequence, give access to meaning<strong>and</strong> muscles are moved to say the words. In Chinese, the visual character represents amorpheme, i.e. the smallest component of a word which carries meaning. These haveto be integrated to construct the whole meaning, then muscles are moved to say thesounds. In Chinese, the reader has access to the meaning without saying the sounds.In English, meaning is accessed directly from print by skillful readers with automaticcontrol over vaks linkages, whilst poor readers are frequently observed to point <strong>and</strong> saythe words aloud, or move their lips appropriately to gain much slower <strong>and</strong> less completeaccess to the sense.The different initial linkage procedures required in phonetic <strong>and</strong> logographic languagesin order to begin reading are depicted in Figure 2.Figure 2Initial linkages in learningto read in phonetic <strong>and</strong>logographic languagesmotor controlto say (or write)idea ormeaningEnglishshapemotor controlto say (or write)idea ormeaningChineseshapesoundsoundIt is misleading to base a theory of the nature <strong>and</strong> causes of literacy difficulty on wordrecognition in the beginning stages of reading, which is only one step in a long <strong>and</strong>complex spoken language-literacy-verbal thinking process. The ‘uniform theory’ whichProfessor Siok seeks will not be found by concentrating upon fine inter-language differencesin word recognition.Whilst clearly the initial approach to establishing the essential visual-auditorykinaesthetic-semanticcross-modal linkages is different for phonological <strong>and</strong> logographiclanguages, considered developmentally over time, this is not a matter of great cognitiveor linguistic significance. What is much more important is that in both types oflanguage, regardless of the different approach to creating the initial links across theseessential aspects of early literacy, good readers can move freely <strong>and</strong> easily from onesensory modality to access all the others, but poor readers cannot. It is the achievement23

The importance oflanguage skills 1of automatic control over the cross-modal transfer of information in reading whichdistinguishes good from poor readers in both phonological <strong>and</strong> logographic languages,<strong>and</strong> it is at this level that Siok’s ‘uniform theory’ can be found.Without automatic control over these linkages the acquisition of language <strong>and</strong> literacywill be slow, difficult <strong>and</strong> very inefficient. Later in this paper where the beginnings ofthe teaching of reading are considered, the contribution of Vygotsky to the underst<strong>and</strong>ingof this particularly important area of the young child’s development will be considered<strong>and</strong> suggestions for remediation will be offered.Speech structures <strong>and</strong> reading failureWe have seen that problems in the child’s development of the structure of speechcontribute to his later reading failure.Animal communication systems can be identified <strong>and</strong> linked with regular meaningsso that the same movement pattern or sequence always represents the same meaning.This regularity is a key characteristic of their communication, but, as will be seen fromthe discussion following, this consistency does not hold for human speech, <strong>and</strong> it is inthis area of inconsistency in vocabulary, structure <strong>and</strong> usage that dyslexic <strong>and</strong> language<strong>disadvantage</strong>d learners have problems.For the young child learning his language, the first step in building a very complexstructure is to hear <strong>and</strong> make sounds. This leads him from phonetics to phonology,determining which phonetic sounds are significant, <strong>and</strong> how these sounds are meaningfulto the speaker. The next step in the evolving process is to develop competence inmorphology, the appreciation of how sounds are used to construct words. Then the useof words in a growing grammatical structure leads to an appreciation of syntax. Thisgives underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the expression of meaning in semantics, <strong>and</strong> at a very high levelof skill, the underst<strong>and</strong>ing of meaning <strong>and</strong> language usage related to speaker-addresseecontext in pragmatics. All these competences are structurally linked <strong>and</strong> each successivestage is dependent upon the integrity of the preceding level. Difficulties in phonetics<strong>and</strong> phonology will lead to significant limitations in learner performance at the laterdeveloping, higher levels of semantics <strong>and</strong> pragmatics. In phonologically opaquelanguages effective underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the application of these skills to word recognitionis required for reading success.Generally, in learning his language, the child starts by producing <strong>and</strong> playing withsounds. Then, at the end of his first year, he uses sound patterns repetitively to formwords. The number of words which the child must learn varies from language tolanguage, because the total vocabulary of languages varies greatly, with English havinga huge lexicon of approximately 1,000,000 words, while some other European languagessuch as French use about 250,000 words.In saying a single word, it cannot be assumed that the child’s usage is similar to theadult’s. The child’s single word is ‘holophrastic,’ actually st<strong>and</strong>ing for a sentence. In thislanguage form the word ‘door’ can mean ‘open that door’ or perhaps, ‘what a nice door,’depending upon speed, pitch <strong>and</strong> tone of the utterance. Eventually other word formssuch as verbs are added, particularizing <strong>and</strong> clarifying meaning but the child’s developinglanguage has been described by most experts as being different from the adultlanguage model <strong>and</strong> may be classified as a language form in its own right. Vocabulary24

The importance oflanguage skills 1increases enormously with age, with best estimates being given of 2,500 words at age six,3,600 words at age eight, <strong>and</strong> 5,400 words at age ten.The extent of the child’s vocabulary knowledge is important because the research literatureshows that vocabulary knowledge in pre-first grade children is an accurate predictorof their later reading development. Snowling et al. (2003) is one of many papers offeringsupport to this perspective. Deficient vocabulary skills have been shown by Tabors <strong>and</strong>Snow (2001) to be a significant cause of reading failure in second language learners withlimited spoken English skills. There is one further area where vocabulary deficits arerelevant. Snowling (2000) has shown that vocabulary deficits are a significant cause ofreading comprehension problems in students with adequate skill in word recognition.The child’s synthesis of grammatical rulesAgain, international differences are apparent in simple sentence construction, with mostlanguages placing the verb before the subject, but this does not hold for English. Therelevant grammatical rules must be synthesized by the child from whatever backgroundlanguage experience is available.Towards the end of the child’s second year, following a period of rapid vocabulary growth,the child begins to experiment with word groupings, varying the original model eachtime, e.g. ‘Give me teddy’ ... ‘Give me the ball.’ Research by Berman (1969) <strong>and</strong> Bever(1971) confirms the importance for the learner of sentence models in both speaking <strong>and</strong>extracting the meaning from spoken words. Bruner (1957) also stressed the importanceof the quality of the language sample available to the learning child, <strong>and</strong> the necessity ofconstructing adequate models, but pointed out that in the time available it was impossiblefor the child to learn all the sentence forms that he would eventually be able to produce bymodeling. The child must work out the rules governing new utterances <strong>and</strong> modify theseconstructively, as experience, maturation <strong>and</strong> consolidation dictated.At this stage of the child’s language development it is evident that two key determiningfactors are necessary for the successful formulation of the required structural rules forspeech <strong>and</strong>, later, literacy. These are (i) a positive <strong>and</strong> helpful language sample availablefrom parents/significant others in the home/nursery background <strong>and</strong> (ii) the cognitivecompetences in perception <strong>and</strong> memory to make the necessary analyses of speech samples<strong>and</strong> syntheses of the relevant structural rules. Limitations in one or both of these factorswill lead to phonological/speech/language difficulties with consequent negative effects uponthe later developing acquisition of literacy which is based upon this foundation.Bruner’s view of the importance of the establishment of structural rules was confirmed bythe fascinating research of Jean Berko (1958), who pioneered the use of nonsense syllablesto demonstrate the child’s underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>and</strong> use of grammatical rules. The child wasshown a picture of a small animal <strong>and</strong> told, ‘This is a wug. Now there are two of them.There are two ...?’ As the child had never heard of a wug before, <strong>and</strong> had no previousexperience of this plural form, his response ‘wugs’ was evidence of his knowledge of a rulefor the construction of the plural form synthesized from past experience, <strong>and</strong> which wasapplicable to this novel situation.Wiig, Semel <strong>and</strong> Crouse, (1973) reported significant differences between poor <strong>and</strong> normalnine year old readers on Berko’s Test of Morphological Usage, <strong>and</strong> concluded that language<strong>disadvantage</strong>d<strong>and</strong> dyslexic students were significantly delayed in the acquisition of25

The importance oflanguage skills 1morphological generalizations. It was thought that this deficiency was a cause rather thanan effect of reading difficulty. They recommended that remediation of these speech/cognitiveproblems should be undertaken prior to the approach to reading instruction.A further study supporting these findings was carried out by Vogel (1978) who comparedseven year old dyslexic <strong>and</strong> normal children on a range of speech skills: syntactic ability,oral syntax, morphological usage, listening comprehension, sentence repetition, clozeprocedure, <strong>and</strong> ability to detect melodic variations. She found that her reading failing groupwas deficient on 7 out of the 9 measures. Stark <strong>and</strong> Tallal (1988), also reached a similarconclusion, ‘the vast majority of children with reading impairment may also have somedegree of oral language deficit.’The developmental history of students attending a specialist school for children withspecific language impairment was monitored by Haynes <strong>and</strong> Naidoo (1991). They reportedthat only 7 out of 82 children attending the school showed no reading impairments.From all this work, it is apparent that in learning language <strong>and</strong> literacy in English, weaknessin phonology, limited vocabulary, poor knowledge of morphology <strong>and</strong> grammaticalrules, an inadequate structure of language, <strong>and</strong> deficient reading skills are causally related<strong>and</strong> have a common base in the quality <strong>and</strong> extent of the child’s early language experience<strong>and</strong> cognitive development. There is also support in the literature for the inference thatthe learner’s inadequate structure in language leads to the different thinking/learningstyle, characteristic of language deprived <strong>and</strong> dyslexic students in their less than successfulinteraction with school’s curriculum.Idiosyncrasy of meaning from languageWhilst the primary function of language is communication, language has the veryimportant secondary function of providing mankind with a ‘thinking tool.’ This greatlysimplifies <strong>and</strong> facilitates his manipulation of ideas but does this tool actually distortthe ideas being manipulated? There is evidence to confirm that it does. It is generallyacknowledged that languages do not exhibit an absolute one-to-one correspondencebetween form <strong>and</strong> meaning. Meaning conveyed through language is more idiosyncraticthan we think.Initially the unanimity of acceptance of the meaning of single words across the rangeof speakers of the language must be considered. The organized pattern of sounds whichcomprise words mean something to the speaker <strong>and</strong> to the listener but the assumptionthat these sound patterns have exactly the same meaning for two different childrenfrom contrasting learning backgrounds, for a dyslexic <strong>and</strong> a skilled verbal learner, for ateacher <strong>and</strong> student, for a defendant <strong>and</strong> a magistrate in court, is unwarranted.Take the meaning of the word ‘book,’ <strong>and</strong> think about it carefully. Does it have a hardcover? Not necessarily, a paper back or soft cover will do. What size is it? It can be big orsmall, thick or thin. What about its contents? Does it have to contain a formal expositionof a learned subject? No, it can be a story, a diary, a collection of papers. How would youclassify Vercingetorix the Gaul? Is it a comic? But when may a comic become a book?What about print? Does that determine the concept of ‘book’? We might agree that abook contains words in print, but it can also contain figures, diagrams, pictures, musicalscores, spaces, <strong>and</strong> even blank pages. Is every book printed? Look at the Book of Kells in26

The importance oflanguage skills 1the library of Trinity College, Dublin, <strong>and</strong> the answer must be in the negative as booksmay be (beautifully) h<strong>and</strong>written.Now let us apply this knowledge to define objects in our world as books <strong>and</strong> non-books. Ihave gone round a lecture group of teachers, lifting objects off their desks <strong>and</strong> asking themto say whether the object was a book or non-book, <strong>and</strong> found some surprising disagreements.I ask, ‘is this object a book?’ Some teachers say, ‘yes,’ but others say ‘no, that is alarge magazine, or an exercise book, or a note book.’ Practical testing demonstrates thateven in a very homogeneous group there is no unanimity on the full meaning of even themost concrete concepts. The underst<strong>and</strong>ing of meanings of more complex <strong>and</strong> abstractideas varies even more substantially. The ideas conveyed by the word ‘paradigm’ when usedby a linguist <strong>and</strong> when used by a psychologist skilled in experimental design are two totallydifferent things. If a further example is necessary, consider the diversity of meanings of theexpression ‘public interest’ as used by a defensive Home Secretary, a left wing politician,a ‘green’ voting street protester <strong>and</strong> Julian Assange of WikiLeaks. At this point, languagechoice by skilled users approaches ‘spin,’ where a statement deliberately clouds rather thanclarifies reality for the listener.The meaning individual listeners derive from words spoken by a speaker to an audiencevaries quite significantly <strong>and</strong> can be very ‘subject-context’ related. The conveyance ofmeaning from speaker to listener can never be a 100% effective procedure. As teachers werely very heavily upon this spoken communication process when imparting informationto the children in our care <strong>and</strong> we must be extremely careful about supposing it to be moreeffective than it actually is.The difficulties in formulating complex meaning into words so that another person withdifferent language experience can underst<strong>and</strong> our thinking, is clearly seen in a ‘tonguein-cheek’report from the courts published in the Sunday Times in the 1970s. An illiterateresident of West Indian origin was summoned to a London court for the non-paymentof rates (the local council charge). When the magistrate asked him for an explanation, hereplied, ‘Man I don’t pay no rates.’ The magistrate was offended by this direct, forthright,statement <strong>and</strong> the dogmatic tone used <strong>and</strong> incorrectly interpreted what was said as adeliberate refusal to pay. He ordered that the defendant should go to prison. Fortunately forall concerned, a solicitor, also of West Indian extraction, attending for another case, spokeup <strong>and</strong> explained, ‘What that man was trying to say was, ‘the rates bill of the property inwhich I reside is not my financial responsibility because I pay a rent which is inclusive ofrates.’ This is a complex idea which requires considerable skill in formulation <strong>and</strong> expression<strong>and</strong> more than a little patience <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong>ing in the listener. This illustrationshows not only the complexity of the problem, but perhaps more significantly, the need torecognize in the first place that a significant problem exists.It is clear that there may be a world of difference between what is heard by the listener <strong>and</strong>what is meant by the speaker. The meaning conveyed by the actual words spoken may alsobe modified semantically by other aspects of speech such as rhythm, pitch <strong>and</strong> tone, whichare not apparent from the printed word. Words <strong>and</strong> phrases may be marked with a declarative,emphatic, emotional or questioning tone, which modifies the semantic implicationsThis was shown by an acquaintance, who carried out an excellent piece of research on thebroadcast football results each Saturday evening on bbc radio. He demonstrated that it waspossible to predict the match result from the home team score <strong>and</strong> the announcer’s use ofpitch as he approached the second score.27