Gramsci and Trotsky in the Shadow of Stalinism: The ... - Indymedia

Gramsci and Trotsky in the Shadow of Stalinism: The ... - Indymedia

Gramsci and Trotsky in the Shadow of Stalinism: The ... - Indymedia

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

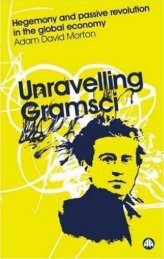

<strong>Gramsci</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Trotsky</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>Shadow</strong> <strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ism<strong>The</strong> Political <strong>The</strong>ory <strong>and</strong> Practice <strong>of</strong> OppositionEmanuele SaccarelliNew York London

To Mamma <strong>and</strong> Nonna, who do not approve

ContentsAcknowledgmentsixChapter OneIntroduction: Enter Stage Left, <strong>Gramsci</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Trotsky</strong> 1PART I: THE MUMMY, THE PROFESSOR, AND THECANNIBAL: THE CONTEMPORARY USES AND THEMARXIST RECLAMATION OF ANTONIO GRAMSCI 21Chapter TwoOut <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Wrapp<strong>in</strong>gs: <strong>Gramsci</strong>ology <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Embalm<strong>in</strong>g<strong>of</strong> Political <strong>The</strong>ory 23Chapter ThreeA Man <strong>of</strong> Modest Appetite: <strong>Gramsci</strong> <strong>and</strong> Political Cannibalism 46PART II: THE FORTUNE-TELLER AND THEHIGH-WIRE ACT: LEON TROTSKY, STALINISM,AND POLITICAL THEORY 87Chapter FourTell<strong>in</strong>g Fortunes to <strong>the</strong> Doomed: <strong>Trotsky</strong> from Clairvoyanceto <strong>The</strong>ory 89Chapter Five<strong>The</strong> Balance <strong>of</strong> Criticism: <strong>Trotsky</strong>’s High-Wire Act 129Chapter SixConclusion 183vii

viiiContentsNotes 193Bibliography 285Index 295

xAcknowledgmentsI thank my advisor James Farr for his support <strong>and</strong> guidance throughoutthis process. I have always suspected that Jim was partly bemused <strong>and</strong>partly horrified by my antics. But he always rema<strong>in</strong>ed generous <strong>and</strong> supportive,<strong>and</strong> was wise enough to keep me on a long leash. I thank MaryDietz for not lett<strong>in</strong>g me get away with too much, <strong>and</strong> especially for tolerat<strong>in</strong>gmy less than tactful mus<strong>in</strong>gs on Arendt. Thanks to Mary I understoodthat <strong>the</strong>re is a difference between <strong>in</strong>tellectual rigor <strong>and</strong> rigor mortis. I thankAugust Nimtz for show<strong>in</strong>g me that it can be done, <strong>and</strong> I don’t mean writ<strong>in</strong>ga book. Expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> ways <strong>in</strong> which August transcends <strong>the</strong> limits imposedby academia would require a separate dissertation, <strong>and</strong> one is more thanenough. I thank Christopher Isett for be<strong>in</strong>g always helpful <strong>and</strong> available tome. Because <strong>of</strong> Chris my <strong>in</strong>tellectual <strong>in</strong>terests took an <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g detour,<strong>and</strong> although I am back on my own road, I do no regret it. I thank TimothyBrennan for a gracious note delivered, as some Italians would say, <strong>in</strong> “zonaCesar<strong>in</strong>i,” <strong>and</strong> regret that our paths <strong>in</strong> M<strong>in</strong>nesota didn’t cross <strong>in</strong> time for amore extensive collaboration.I must also thank Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Chris Johnson, from Wayne State University,who opened up new vistas for my m<strong>in</strong>d. Before meet<strong>in</strong>g Chris, I ate,slept, <strong>and</strong> did as I was told. After, I started th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g. Incidentally, Chris alsodemonstrated to me that <strong>the</strong> old left is far from senile, <strong>and</strong> alerted me to <strong>the</strong>possibility that it’s <strong>the</strong> new guys who have lost <strong>the</strong>ir m<strong>in</strong>ds. From WayneState I also wish to thank Philip Abbott, that ideologically <strong>in</strong>scrutable, dist<strong>in</strong>guishedgentleman <strong>of</strong> political <strong>the</strong>ory. I thank <strong>the</strong> many comrades fromDetroit who are better than I am, <strong>and</strong> without question know more aboutthis stuff than I do. In spite <strong>of</strong> my laz<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>and</strong> bad habits, <strong>the</strong>y cont<strong>in</strong>ue toprovide a different, <strong>and</strong> no less important k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> education. Hopefully oneday I’ll learn. I thank <strong>the</strong> few friends who have helped make my seven years<strong>in</strong> graduate school almost tolerable: Mike Heck, Giuliano Pappalardo, MaryThomas, Bogac Erozan, Amit Ron, Giunia Gatta, Kev<strong>in</strong> Parsneau, JorgeRivas, Reynolds Towns <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Red Star FC. I thank those who helped organize<strong>and</strong> some, but not all <strong>of</strong> those who participated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>The</strong>ory Colloquium,<strong>the</strong> Marx Read<strong>in</strong>g Group, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Little Jimmies dissertation group.I thank Dave <strong>and</strong> Steve for many <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g conversations <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Polab <strong>and</strong>for be<strong>in</strong>g normal people <strong>in</strong> a place that is decidedly not. I thank <strong>the</strong> staff <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Fondazione Istituto <strong>Gramsci</strong> <strong>in</strong> Rome for <strong>the</strong>ir predictably Italian k<strong>in</strong>d<strong>of</strong> help, which I hope to be able to reciprocate very soon. I thank John Grennanfor his timely <strong>in</strong>tervention <strong>in</strong> support <strong>of</strong> my unsteady grammar.Hav<strong>in</strong>g come across Russell Jacoby’s devastat<strong>in</strong>g criticism <strong>of</strong> this practice,I will not thank <strong>the</strong> several c<strong>of</strong>fee shops (Second Moon <strong>and</strong> Mapps <strong>in</strong>M<strong>in</strong>neapolis, Urban Gr<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong> San Diego) where I wrote my book. But I

Acknowledgmentsxiwill thank <strong>the</strong> many, many degenerates I encountered <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se establishments.<strong>The</strong>ir babbl<strong>in</strong>g nonsense, <strong>in</strong>cessant navel-gaz<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> really terriblepoetry <strong>the</strong>y <strong>in</strong>sisted on recit<strong>in</strong>g aloud provided constant <strong>in</strong>spiration (<strong>of</strong>a k<strong>in</strong>d) for me to cont<strong>in</strong>ue writ<strong>in</strong>g even when I didn’t want to. I thank <strong>the</strong>Democratic Party <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> US, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> parties <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Italian “left,” for <strong>the</strong>ircomplete political bankruptcy, which <strong>in</strong>spires me <strong>in</strong> special ways. I have afeel<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>y will cont<strong>in</strong>ue to <strong>in</strong>spire me <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> future.I would be remiss if I neglected to thank <strong>the</strong> many fellow graduate studentsI have met <strong>in</strong> many courses <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> occasional conference. AlthoughI am tempted to, <strong>the</strong>y are far too many to s<strong>in</strong>gle out anyone <strong>in</strong> particular.<strong>The</strong>ir remarkable sense <strong>of</strong> attunement to <strong>the</strong> latest academic fashion, <strong>the</strong>irunflagg<strong>in</strong>g commitment to pr<strong>of</strong>essionaliz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>mselves <strong>and</strong>, whenever possible,o<strong>the</strong>rs, <strong>the</strong>ir unerr<strong>in</strong>g capacity to arrive at <strong>the</strong> most conventional politicalconclusion by way exotic <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>comprehensible epistemological routesnever failed to guide me throughout <strong>the</strong> completion <strong>of</strong> this project. Just asa compass that <strong>in</strong>congruously po<strong>in</strong>ts to <strong>the</strong> South can still serve as a reliable<strong>in</strong>strument for orientation, so long as it does so steadily <strong>and</strong> consistently,<strong>the</strong>ir op<strong>in</strong>ions <strong>and</strong> reactions were an <strong>in</strong>valuable guide for this journey.As to <strong>the</strong>ir own journey, from Chakrabarty to Negri to Agamben, onward<strong>and</strong> upwards to Planet N<strong>in</strong>e, I wish <strong>the</strong>m a safe l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g. I would also liketo thank my new colleagues <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> Political Science at SanDiego State University. I am sure we’ll get along just f<strong>in</strong>e.Most <strong>of</strong> all I wish to thank my wife, who obviously deserved better, forher patience <strong>and</strong> support. She read everyth<strong>in</strong>g I wrote here more times than Ihave. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> time we got toge<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> reason why she puts up with me hasbeen a mystery to many. While I don’t <strong>in</strong>tend to give away <strong>the</strong> secret here, Ido want thank her from my heart.

And who can still say, “I am a Marxist”? 1 Jacques Derrida, 1994.Chapter OneIntroductionEnter Stage Left, <strong>Gramsci</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Trotsky</strong><strong>The</strong> Bolsheviks are compromised, discredited, <strong>and</strong> crushed. More than that. . . <strong>the</strong>ir teach<strong>in</strong>g has turned out to be an irreversible failure, <strong>and</strong> has sc<strong>and</strong>alizeditself <strong>and</strong> its believers before <strong>the</strong> world <strong>and</strong> for all time. 2Editorial page <strong>of</strong> Zhivoe slovo, July 1917.This book addresses a particular period <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> historical development <strong>of</strong>Marxism <strong>in</strong> order to make sense <strong>of</strong> its contemporary impasse, both as a str<strong>and</strong><strong>of</strong> political <strong>the</strong>ory <strong>and</strong> as a liv<strong>in</strong>g political tradition. Specifically, I focus on<strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>oretical <strong>and</strong> political legacy <strong>of</strong> two important Marxist figures, Antonio<strong>Gramsci</strong> <strong>and</strong> Leon <strong>Trotsky</strong>, us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir compell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> tragic stories toprovide a concrete historical account <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rise <strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ism <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terwarperiod <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1920s <strong>and</strong> 1930s. Through this account, I <strong>the</strong>orize Stal<strong>in</strong>ism as<strong>the</strong> complex, disastrous, <strong>and</strong> by no means <strong>in</strong>evitable outcome <strong>of</strong> a politicalstruggle <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational communist movement <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> aftermath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Russian Revolution. I also assess <strong>the</strong> relative merits <strong>of</strong> <strong>Gramsci</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Trotsky</strong>’sanalyses <strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ism, a phenomenon that not only disrupted <strong>the</strong> established<strong>the</strong>oretical framework <strong>of</strong> Marxism, but also served as a challenge <strong>and</strong> imperativeto develop it fur<strong>the</strong>r. In this sense, my book is a work <strong>of</strong> political <strong>the</strong>oryunderstood as <strong>the</strong> historical study <strong>of</strong> political ideas. Stal<strong>in</strong>ism, however, is nota largely ext<strong>in</strong>guished phenomenon <strong>of</strong> mere historical <strong>in</strong>terest. I argue thatStal<strong>in</strong>ism casts a long, though <strong>in</strong> many cases undetected shadow over variouscontemporary academic attempts to revitalize—as well as attempts to overcome—Marxism.While <strong>the</strong>se attempts operate largely at <strong>the</strong> level <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory,much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir force <strong>and</strong> animat<strong>in</strong>g impulses derive from a deeply entrenchedcommon sense about <strong>the</strong> Russian Revolution <strong>and</strong> its <strong>in</strong>evitable totalitarian1

2 <strong>Gramsci</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Trotsky</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Shadow</strong> <strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ismdegeneration. In this <strong>in</strong>troduction I beg<strong>in</strong> by situat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> project <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> contemporarypolitical <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tellectual context. I <strong>the</strong>n discuss <strong>the</strong> choice to focuson <strong>Gramsci</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Trotsky</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>fer a few methodological reflections to expla<strong>in</strong>my approach <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g protocols <strong>of</strong> political <strong>the</strong>ory.F<strong>in</strong>ally, I will provide a schematic account <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> book.I. POLITICAL AND INTELLECTUAL CONTEXTIn an apparently paradoxical turn, <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cold war has marked <strong>the</strong>resurgence <strong>of</strong> academic as well as popular <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> Marx’s writ<strong>in</strong>gs. S<strong>in</strong>ce<strong>the</strong>n, <strong>the</strong> New York Times, <strong>the</strong> New Yorker, U.S. News & World Report, <strong>and</strong>even <strong>the</strong> Wall Street Journal have published articles on Marx that appreciated,albeit reluctantly <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> a politically qualified manner, <strong>the</strong> historicalsignificance <strong>and</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ued relevance <strong>of</strong> his ideas to <strong>the</strong> underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g<strong>of</strong> our world. 3 Similarly, many ambitious <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluential academic works,such as Dipesh Chakrabarty’s Prov<strong>in</strong>cializ<strong>in</strong>g Europe <strong>and</strong> Empire by MichaelHardt <strong>and</strong> Antonio Negri, have called attention to <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> Marx’sthought—although, as <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Wall Street Journal, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir ownpeculiar ways. 4This revival <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> Marx is a curious development. <strong>The</strong> fall <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Soviet Union, widely <strong>in</strong>terpreted as <strong>in</strong>controvertible pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> failure<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> socialist project, could well have resulted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> permanent shelv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong>Marx’s works. Instead, ra<strong>the</strong>r than exorcis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> specter <strong>of</strong> Marx once <strong>and</strong>for all, <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cold war seems to have merely shaken <strong>the</strong> conceptualframework that regimented <strong>the</strong> uses <strong>and</strong> read<strong>in</strong>gs his works. Released from<strong>the</strong> grip <strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ism on one h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> dogmatic anticommunism on <strong>the</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r, seem<strong>in</strong>gly no longer bound to an immediate, credible political referent,be it a party or a state, Marx’s legacy appears now more than before as anopen question.This is not, one should hasten to say, necessarily a good th<strong>in</strong>g. This newclimate could easily encourage politically detached <strong>and</strong> hopelessly eclecticapproaches. <strong>The</strong> questions raised by Marx’s legacy are now even more likelyto be put, so to speak, academically. <strong>The</strong>y can be turned <strong>in</strong>to a mere <strong>in</strong>tellectualexercise that, while more or less rigorous <strong>in</strong> its scholarly <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretivest<strong>and</strong>ards, rema<strong>in</strong>s completely <strong>in</strong>ert <strong>in</strong> a political sense. Nor is it necessarilydesirable to make a clean break from <strong>the</strong> past. <strong>The</strong> framework imposed by<strong>the</strong> cold war was not simply an oppressive fetter, but was itself a process<strong>of</strong> real struggles that, while dom<strong>in</strong>ated by two oppressive poles, might havefeatured real alternatives that were never fully suppressed nor fully pursued.<strong>The</strong>re may be no need to start from scratch <strong>and</strong> re<strong>in</strong>vent <strong>the</strong> wheel. Thus <strong>the</strong>

Introduction 3end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cold war, while hav<strong>in</strong>g a general liberat<strong>in</strong>g effect, is no more thana political opportunity <strong>and</strong> presents us with its own difficult questions <strong>and</strong>accounts left to be settled.<strong>The</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ued <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> Marx can be attributed <strong>in</strong> part to <strong>the</strong> sheerpower <strong>and</strong> richness <strong>of</strong> his works, someth<strong>in</strong>g that even many <strong>of</strong> those who arepolitically unsympa<strong>the</strong>tic to Marxism readily concede. But this <strong>in</strong>terest mustalso be expla<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong> fact that contemporary conditions rema<strong>in</strong> stubbornlybound to many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same questions faced, expla<strong>in</strong>ed, <strong>and</strong> fought byMarx <strong>and</strong> his political heirs. Deny<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se alarm<strong>in</strong>g conditions has become<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly difficult as <strong>the</strong> millennial optimism <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1990s has come to anend. To utter <strong>the</strong> slogans <strong>and</strong> promises <strong>of</strong> this period today—a “new worldorder,” “dividends <strong>of</strong> peace,” a crisis-free “new economy,” <strong>and</strong>, best <strong>of</strong> all,<strong>the</strong> “end <strong>of</strong> history”—is to hear <strong>the</strong> qua<strong>in</strong>t <strong>and</strong> fad<strong>in</strong>g echoes <strong>of</strong> a hopelesslydistant past. <strong>The</strong> ongo<strong>in</strong>g political, military, <strong>and</strong> economic convulsions <strong>of</strong>capitalism <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir severe human consequences cont<strong>in</strong>ue to br<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong>fore those old questions that were thought to have been settled once <strong>and</strong> forall by its alleged triumph.American democracy is afflicted by a pr<strong>of</strong>ound <strong>and</strong> prolonged politicalcrisis. <strong>The</strong> manifold contradictions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> system—<strong>the</strong> strategic convergence<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two bourgeois parties, <strong>the</strong> dom<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>of</strong> money <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> electoral process,<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional straightjacket <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two-party system, <strong>the</strong> fusion <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> state <strong>and</strong> corporate apparatuses—have assumed a very sharp expressions<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> heady days <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> early 1990s. This process was punctuated by anumber <strong>of</strong> dramatic events, most importantly <strong>the</strong> sordid denouement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>2000 election, which brought to <strong>the</strong> fore <strong>the</strong> deep antidemocratic undercurrents<strong>of</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stitutions. 5 <strong>The</strong> result <strong>of</strong> this process is <strong>the</strong> effectivedisenfranchisement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> American population. Most significantly, despite<strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> American people oppos<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> war <strong>in</strong> Iraq, <strong>the</strong> exist<strong>in</strong>gpolitical establishment rema<strong>in</strong>s completely unable to translate this popularwill <strong>in</strong>to a fact.This is not, moreover, merely a political crisis <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g parties <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>stitutions, but a more comprehensive ideological one <strong>of</strong> perspective <strong>and</strong>orientation. It affects all those forces that, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternationally,had hi<strong>the</strong>rto played a plausible <strong>and</strong> passable role as alternativesto unfettered capitalism. American liberalism is <strong>in</strong> a state <strong>of</strong> term<strong>in</strong>al decaythat can be measured <strong>in</strong> myriad ways. In <strong>the</strong> academic establishment, onecould compare John Dewey’s attitude toward <strong>the</strong> free market with that <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> late Richard Rorty, or consider Alan Dershowitz <strong>and</strong> Michael Igniatieff’sefforts to f<strong>in</strong>esse <strong>the</strong> philosophically proper uses <strong>of</strong> torture <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> waraga<strong>in</strong>st terror. In <strong>the</strong> media, it can be measured by observ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> change <strong>in</strong>

4 <strong>Gramsci</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Trotsky</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Shadow</strong> <strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ismBob Woodward’s activities, from his dogged <strong>and</strong> uncompromis<strong>in</strong>g pursuit<strong>of</strong> Richard Nixon’s lies to his calm <strong>and</strong> docile chronicl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> an adm<strong>in</strong>istrationwhose level <strong>of</strong> deceit <strong>and</strong> crim<strong>in</strong>ality is exponentially greater. Or itcan be measured by <strong>the</strong> active <strong>and</strong> conscious role played by <strong>the</strong> New YorkTimes <strong>in</strong> prepar<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> groundwork for <strong>the</strong> war <strong>in</strong> Iraq, as well as its embarrass<strong>in</strong>glypremature celebration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> failed 2002 coup <strong>in</strong> Venezuela. Thisdecay can even be measured <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> broader realm <strong>of</strong> public <strong>in</strong>tellectuals <strong>and</strong>popular culture, by observ<strong>in</strong>g how easily September 11 caused <strong>the</strong> politicalunh<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> many “sensible progressives”—from left-radicals like ChristopherHitchens down to funny-man Dennis Miller. 6Internationally, multifarious alternative capitalist models, each with itsown dist<strong>in</strong>ctive charm—from <strong>the</strong> cradle-to-grave welfare <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sc<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>aviansocial democracies to Japan’s promises <strong>of</strong> lifelong employment—all nowappear as folkloristic episodes, deviations that are be<strong>in</strong>g reabsorbed <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>fold <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> global market <strong>and</strong> its harsh imperatives. Whe<strong>the</strong>r measured by <strong>the</strong>conscious <strong>and</strong> acknowledged Thatcherism <strong>of</strong> Tony Blair’s New Labour, by <strong>the</strong>ambitions <strong>of</strong> Gerhardt Schroeder’s Agenda 2010, or <strong>the</strong> radical free-market“reforms” enacted <strong>in</strong> Italy by Romano Prodi <strong>and</strong> Massimo D’Alema, Europeansocial democracy, once considered a political alternative, now lays <strong>in</strong>shambles. Third World nationalism is <strong>in</strong> no better shape, hav<strong>in</strong>g squ<strong>and</strong>ered<strong>the</strong> political capital it accrued <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> anti-imperialist struggles <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> past.<strong>The</strong> trajectory <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Congress Party <strong>of</strong> India is <strong>in</strong>structive <strong>in</strong> this sense. Thisorganization had been <strong>the</strong> historical vehicle <strong>of</strong> a struggle aga<strong>in</strong>st foreign capital<strong>and</strong> dom<strong>in</strong>ation that, regardless <strong>of</strong> its political limits, was endowed witha certa<strong>in</strong> dignity. In <strong>the</strong> past two decades, however, <strong>the</strong> Congress acted as <strong>the</strong>political vanguard <strong>of</strong> free-market reform. Driv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> symbolic last nail <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> c<strong>of</strong>f<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Congress Party tradition, prime m<strong>in</strong>ister Manmohan S<strong>in</strong>ghdeclared <strong>in</strong> his speech at Oxford that, “India’s experience with Brita<strong>in</strong> hadits beneficial consequences,” <strong>and</strong> that “India’s struggle for <strong>in</strong>dependence wasmore an assertion by Indians <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir natural right to self-governance than anoutright rejection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> British claim to good governance.” 7 <strong>The</strong>re are manymore examples <strong>of</strong> this degeneration, from Muammar Gaddafi’s prostrationbefore <strong>the</strong> Bush adm<strong>in</strong>istration regard<strong>in</strong>g Libya’s nuclear program, to what isleft <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Palest<strong>in</strong>e Liberation Organization, with its total political <strong>and</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancialdependence on Western imperialism. <strong>The</strong> contemporary <strong>in</strong>ternationall<strong>and</strong>scape is littered with <strong>the</strong> political carcasses <strong>of</strong> Third World nationalism,particularly those organizations <strong>and</strong> regimes that could parade as mavericks<strong>and</strong> emancipators under <strong>the</strong> military shield <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Soviet Union.This generalized political impasse rests on a troubled economic foundation.In <strong>the</strong> American economy, <strong>the</strong> lynchp<strong>in</strong> market <strong>of</strong> world capitalism, one

Introduction 5f<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>the</strong> accumulation <strong>of</strong> significant vulnerabilities. <strong>The</strong> widely predictedrun on <strong>the</strong> dollar, <strong>the</strong> complete dependence on foreign <strong>in</strong>vestments, <strong>the</strong>explosion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial, <strong>and</strong> particularly <strong>the</strong> trade deficit, <strong>the</strong> negative sav<strong>in</strong>gsrate <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> American consumers, <strong>the</strong> “outsourc<strong>in</strong>g” even <strong>of</strong> service jobs,<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> unprecedented “bubble” <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> hous<strong>in</strong>g market, constitute powerfulwarn<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> trouble to come. This may or may not signal <strong>the</strong> possibility <strong>of</strong> animpend<strong>in</strong>g economic crisis. In any case, <strong>the</strong> great prosperity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cl<strong>in</strong>tonera, one that <strong>in</strong> fact dispensed its bless<strong>in</strong>g only to a very limited section <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> population, has come to a halt, leav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> its wake only dizzy<strong>in</strong>g levels <strong>of</strong>social <strong>in</strong>equality. <strong>The</strong> rise <strong>of</strong> social <strong>in</strong>equality, beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mid-1970s,has now reached levels last seen at <strong>the</strong> onset <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Great Depression. 8 This is<strong>the</strong> most endur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> significant fact <strong>of</strong> economic life <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States.Its social manifestations are legion <strong>and</strong> well documented—<strong>the</strong> tens <strong>of</strong> millionswho lack medical <strong>in</strong>surance, <strong>the</strong> decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g access to a university educationfor <strong>the</strong> lower segments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population, etc. Indeed <strong>the</strong> political crisissketched out above is <strong>the</strong> unsurpris<strong>in</strong>g outcome <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fundamental <strong>in</strong>compatibilitybetween <strong>the</strong>se levels <strong>of</strong> social <strong>in</strong>equality <strong>and</strong> democracy.<strong>The</strong>se economic troubles are not conf<strong>in</strong>ed to <strong>the</strong> United States. Internationally,<strong>the</strong> luster <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most dynamic model <strong>of</strong> capitalist development,<strong>the</strong> “Four Tigers” <strong>of</strong> Asia, was significantly tarnished by <strong>the</strong> 1998 crisis. <strong>The</strong>condition <strong>of</strong> Central <strong>and</strong> South American countries, highlighted by <strong>the</strong> “bailout”<strong>of</strong> Mexico <strong>in</strong> 1995, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> later economic meltdown <strong>of</strong> Argent<strong>in</strong>a, hasput a damper on illusions about <strong>the</strong> prospect <strong>of</strong> a generalized prosperity <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> absence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Soviet threat. <strong>The</strong> economic “miracles” <strong>of</strong> India <strong>and</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>amay be very impressive <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> GDP growth, but appear <strong>in</strong> an entirelydifferent light when considered from <strong>the</strong> st<strong>and</strong>po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rural <strong>and</strong> urbanwork<strong>in</strong>g population <strong>of</strong> those countries, <strong>and</strong> only serve to prepare futureconflagrations. <strong>The</strong> social <strong>and</strong> economic impact <strong>of</strong> capitalist restoration <strong>in</strong>Russia, f<strong>in</strong>ally, is perhaps <strong>the</strong> most embarrass<strong>in</strong>g reality that <strong>the</strong> once-eagerprophets <strong>of</strong> capitalist triumph must now face with extreme discomfort—<strong>in</strong>this case, <strong>the</strong> farce, as it were, preceded <strong>the</strong> tragedy.But <strong>the</strong> most concrete <strong>and</strong> destructive manifestations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> present difficultiesare found <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> realm <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational relations. <strong>The</strong> ongo<strong>in</strong>g events<strong>in</strong> Iraq <strong>and</strong> Afghanistan—<strong>and</strong> before that, <strong>the</strong> no less predatory (thoughmore tactfully presented) adventures <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Balkans, Somalia <strong>and</strong> Haiti—have vanquished <strong>the</strong> hopes for a peaceful new world order. But <strong>the</strong>y havealso stimulated <strong>the</strong> suspicion that <strong>the</strong> old question <strong>of</strong> imperialism rema<strong>in</strong>sone <strong>of</strong> press<strong>in</strong>g significance. <strong>The</strong> resurgence <strong>of</strong> economic <strong>and</strong> political tensionbetween <strong>the</strong> United States <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> European countries (<strong>the</strong> Boe<strong>in</strong>g-Airbus affair, <strong>the</strong> fight over agricultural subsidies, <strong>the</strong> conflict over <strong>the</strong> Iraq

6 <strong>Gramsci</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Trotsky</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Shadow</strong> <strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ismwar, <strong>the</strong> development <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States <strong>of</strong> a crude antipathy toward allth<strong>in</strong>gs French) <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> many unmistakable signals sent by Japan (JunichiroKoizumi’s <strong>in</strong>cendiary visits to <strong>the</strong> shr<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> Japan’s war dead, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> proposedrevision <strong>of</strong> Article N<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Japanese Constitution concern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> national armed forces) assail one’s nostrils with <strong>the</strong> familiar <strong>and</strong> unpleasantodor <strong>of</strong> chauv<strong>in</strong>ism characteristic <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pre-World War I period. Indeedit is significant that imperialism is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly be<strong>in</strong>g discussed <strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> aroundrul<strong>in</strong>g circles without shame, as a positive good. From Oxford dons (NiallFerguson), to more common foot-soldiers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bourgeois press (<strong>the</strong> appropriatelynamed Max Boot), to <strong>the</strong> human residue unpleasantly deposited <strong>in</strong>our times by <strong>the</strong> empires <strong>of</strong> old (D<strong>in</strong>esh D’Souza <strong>and</strong> Deepak Lal), a remarkablyshameless literature <strong>in</strong> praise <strong>of</strong> imperialism has been produced <strong>of</strong> late. 9In sum, all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> forces that had <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> past made claims <strong>and</strong> attemptsto resist, moderate, or modulate capitalism today show unmistakable signs<strong>of</strong> historical exhaustion. At <strong>the</strong> same time, however, even <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> epoch <strong>of</strong>its alleged triumph, capitalism cont<strong>in</strong>ues to go through terrible convulsions.Recurr<strong>in</strong>g economic crises, <strong>the</strong> historical <strong>in</strong>completeness <strong>and</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r erosion<strong>of</strong> democracy, <strong>and</strong>, most importantly, a state <strong>of</strong> war that shows no sign <strong>of</strong>abat<strong>in</strong>g all suggest that <strong>the</strong> real character <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> present epoch has little <strong>in</strong>common with <strong>the</strong> pervasive trumpet<strong>in</strong>g that followed <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> coldwar. For <strong>the</strong>se reasons, <strong>the</strong> ongo<strong>in</strong>g Marx revival is at least <strong>in</strong> one sense notsurpris<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>The</strong> gap between <strong>the</strong> severity <strong>of</strong> current conditions <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> earlierexpectations practically dem<strong>and</strong>s a second look at <strong>the</strong> tradition that provided<strong>the</strong> most forceful, radical, <strong>and</strong> comprehensive critique <strong>of</strong> capitalism <strong>and</strong> itseffects. It is <strong>in</strong> this sense, <strong>in</strong>cidentally, that I hope to fend <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> likely primafacie objections about <strong>the</strong> untimely character <strong>of</strong> a return to Marx <strong>and</strong> hislegacy. If, for whatever reason, <strong>the</strong> Wall Street Journal feels at liberty to revisit<strong>the</strong> question <strong>of</strong> Marx’s legacy, <strong>the</strong>n anyone can feel safe <strong>in</strong> do<strong>in</strong>g so withouthav<strong>in</strong>g to worry about knee-jerk accusations <strong>of</strong> strange or depraved belatedness.However, precisely because <strong>the</strong> Wall Street Journal is engaged <strong>in</strong> thisoperation, <strong>the</strong> specific character <strong>of</strong> this revival—its nature, its ends, its prospects—needsto be <strong>in</strong>terrogated.It is no exaggeration to say that many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> academic works that haveattempted to revisit Marx seem <strong>in</strong>tended to exorcise him. More precisely,<strong>the</strong>se seem to be attempts to transcend Marx, to demonstrate his fundamental<strong>in</strong>adequacy to <strong>the</strong> challenges <strong>of</strong> our epoch, even as <strong>the</strong>y pay homage to histower<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tellect. <strong>The</strong> two works I have cited as examples <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> academicdimension <strong>of</strong> this revival illustrate <strong>the</strong> peculiar <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> some ways tendentiouscharacter <strong>of</strong> this phenomenon. In Prov<strong>in</strong>cializ<strong>in</strong>g Europe, Chakrabartyreturns to Marx, but as a stepp<strong>in</strong>g-stone to better reach Heidegger. 10

Introduction 7In Empire, Hardt <strong>and</strong> Negri summon Marx to po<strong>in</strong>t out <strong>the</strong> myriad ways <strong>in</strong>which he has been surpassed. 11Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, to <strong>the</strong> extent that <strong>the</strong>se works seek to recover positive,useful <strong>in</strong>sights from Marx, <strong>the</strong>y tend to do this by detach<strong>in</strong>g his <strong>in</strong>tellectuallegacy from his political one. Many examples <strong>of</strong> this tendency couldbe listed, such as Terrell Carver’s <strong>The</strong> Postmodern Marx, Derrida’s Specters <strong>of</strong>Marx, <strong>and</strong> Moishe Postone’s Time, Labor, <strong>and</strong> Social Dom<strong>in</strong>ation. In <strong>the</strong>seworks, we see an attempt to return to <strong>and</strong> develop a particular aspect <strong>of</strong>Marx’s thought paired with an explicit rejection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> historical experience<strong>of</strong> Marxism. 12 This peculiar maneuver takes place as though <strong>the</strong> collapse <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Soviet Union had really freed Marx himself, <strong>and</strong> not just <strong>the</strong>se academicauthors, from an unwanted burden, so that he can f<strong>in</strong>ally assume his rightfulplace as a proper <strong>in</strong>tellectual. In some cases, strenuous efforts are madeto make Marx himself speak aga<strong>in</strong>st Marxism. 13 In o<strong>the</strong>r cases, what Marxactually said is considered to be irrelevant, leav<strong>in</strong>g one to wonder exactlywhat <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g to even a formal <strong>and</strong> conditional allegiance to himmight be. 14 Of course <strong>the</strong> actual political import <strong>of</strong> this literature is less thanclear, sometimes even to its authors. 15Shift<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> focus <strong>of</strong> this discussion more decisively from Marx toMarxism, a move that gets us closer to <strong>the</strong> actual subject <strong>of</strong> this work, it ispossible to see similarly odd academic uses <strong>and</strong> abuses <strong>of</strong> this political tradition.On <strong>the</strong> one h<strong>and</strong>, it is all too easy to detect a widespread rejection<strong>of</strong> it. For a wide array <strong>of</strong> “post-Marxisms,” encompass<strong>in</strong>g cross-discipl<strong>in</strong>arytrends such as poststructuralism <strong>and</strong> postcolonialism, Marxism customarilyserves as a foil. <strong>The</strong> criticisms levied aga<strong>in</strong>st it have to do with <strong>the</strong> Eurocentriccharacter <strong>of</strong> its narrative (its <strong>in</strong>sensibility to cont<strong>in</strong>gency <strong>and</strong> culturalspecificity); <strong>the</strong> reductionism <strong>of</strong> its underly<strong>in</strong>g social <strong>the</strong>ory (its perceivedcorrespondence between an economic “base” <strong>and</strong> a political <strong>and</strong> ideological“superstructure”); <strong>the</strong> determ<strong>in</strong>ism <strong>of</strong> its outlook (its emphasis on objectivestructures <strong>and</strong> processes that elim<strong>in</strong>ates any room for human agency); <strong>and</strong>its scientism (its untenable pretension to exam<strong>in</strong>e social phenomena as onewould exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> natural world). On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>the</strong>re is someth<strong>in</strong>gpeculiar about <strong>the</strong> way <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong>se trends have emerged <strong>and</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ueto develop out <strong>of</strong> a confrontation with <strong>the</strong> perceived deficiencies <strong>of</strong> Marxism.This seems to be less <strong>of</strong> a necessary prelim<strong>in</strong>ary move to clear out newground <strong>and</strong> more <strong>of</strong> a permanent posture. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, if Marxism didnot exist, it would be necessary for <strong>the</strong> post-Marxists to <strong>in</strong>vent it. 16 Thus,multifarious str<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> academic thought seem <strong>in</strong>tent on permanently keep<strong>in</strong>gMarxism, such as <strong>the</strong>y perceive it to be, <strong>in</strong> a sort <strong>of</strong> coma. Marxism isdeemed to be completely <strong>in</strong>ert, <strong>and</strong> yet, <strong>in</strong> a certa<strong>in</strong> sense, its existence is

8 <strong>Gramsci</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Trotsky</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Shadow</strong> <strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ismconsidered sacred. It is tangibly present, among us, but no longer able tospeak for itself. Instead, it is always spoken about by critics who are not boldor serious enough to renounce <strong>and</strong> denounce it once <strong>and</strong> for all.Exactly what is this “Marxism” <strong>the</strong> “post-Marxists” are perpetually <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> transcend<strong>in</strong>g? We are rarely told. When a dem<strong>and</strong> for somespecificity <strong>and</strong> precision is made to this literature, one comes away emptyh<strong>and</strong>ed.In most cases, “Marxism” appears as a remarkably generic <strong>and</strong>unspecified construct. An example that is especially pert<strong>in</strong>ent to my work is<strong>the</strong> way <strong>in</strong> which Stuart Hall <strong>and</strong> Cornel West praise <strong>Gramsci</strong> as a sophisticated<strong>the</strong>orist <strong>of</strong> endur<strong>in</strong>g significance. In do<strong>in</strong>g so, <strong>the</strong>y both present aremarkable contrast. Hall claims that. . .”hegemony” <strong>in</strong> <strong>Gramsci</strong>’s sense requires, not <strong>the</strong> simple escalation<strong>of</strong> a whole class to power, with its fully formed “philosophy,” but <strong>the</strong>process by which a historical bloc <strong>of</strong> social forces is constructed <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ascendance <strong>of</strong> that bloc secured. 17West, <strong>in</strong> turn, <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g his <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> <strong>Gramsci</strong>, develops an implicitcomparison:<strong>Gramsci</strong>’s work is historically specific, <strong>the</strong>oretically engag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> politicallyactivistic <strong>in</strong> an exemplary manner. His concrete <strong>and</strong> detailed<strong>in</strong>vestigations are grounded <strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> reflections upon local struggles, yet<strong>the</strong>oretically sensitive to structural dynamics <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational phenomena. . . For [<strong>Gramsci</strong>], <strong>the</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> philosophy is not only to becomeworldly by impos<strong>in</strong>g its elite <strong>in</strong>tellectual views upon people, but tobecome part <strong>of</strong> a social movement by nourish<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g nourishedby <strong>the</strong> philosophical views <strong>of</strong> oppressed people <strong>the</strong>mselves for <strong>the</strong> aims<strong>of</strong> social change <strong>and</strong> personal mean<strong>in</strong>g. 18In both cases, one is compelled to ask <strong>the</strong> question, “as opposed to whom?”Just who or what is <strong>Gramsci</strong>’s concept <strong>of</strong> hegemony superior to, his mode<strong>of</strong> analysis more “historically specific” <strong>and</strong> “concrete,” <strong>and</strong> more mean<strong>in</strong>gfullyconnected to <strong>the</strong> “people <strong>the</strong>mselves?” It is not difficult to see that <strong>the</strong>answer is “Marxism.” But what is this exactly? Hall designates it as “classical”Marxism. 19 But this does not advance matters very much. Does this refer toKorsch, Bordiga, Bukhar<strong>in</strong>, Len<strong>in</strong>, or <strong>Trotsky</strong>? This sort <strong>of</strong> question is notposed—certa<strong>in</strong>ly not <strong>in</strong> this way—because such a level <strong>of</strong> specificity is notdeemed to be pert<strong>in</strong>ent to <strong>the</strong> tasks at h<strong>and</strong>. “Classical” Marxism is construedto <strong>in</strong>clude any <strong>and</strong> all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m. Indeed <strong>in</strong> this literature, <strong>Gramsci</strong> is

Introduction 9typically <strong>the</strong> only one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> “Marxists” to be rescued from this undifferentiatedmass.Understood <strong>in</strong> this way, <strong>and</strong> as shown from <strong>the</strong> passages quoted above,(classical) “Marxism” actually st<strong>and</strong>s for a vulgar <strong>and</strong> crude tradition from apolitically distant past. Although it is obviously passé, it rema<strong>in</strong>s an obligatoryreference exactly <strong>in</strong> order to mark out <strong>the</strong> freshness <strong>and</strong> superiority <strong>of</strong>one’s own outlook. This orientation toward Marxism should be questionedon <strong>the</strong>oretical grounds. <strong>The</strong> differences on matters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory among <strong>the</strong> figuresthat constitute Marxism are quite extensive <strong>and</strong> complex. If, pursu<strong>in</strong>gHall <strong>and</strong> West’s considerations, one were to <strong>in</strong>terrogate Len<strong>in</strong>’s texts on <strong>the</strong>question <strong>of</strong> hegemony, historical specificity, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g quality <strong>of</strong> “philosophy,”for example, <strong>the</strong> results would be completely different than Bordiga’sideas on <strong>the</strong>se topics. Or, if one were to consider Bukhar<strong>in</strong>’s underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g<strong>of</strong> hegemony, it would be necessary to draw a sharp dist<strong>in</strong>ction betweenhis ideas before <strong>and</strong> after <strong>the</strong> year 1921, when this question came to beat <strong>the</strong> center <strong>of</strong> his th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g. In <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> conduct<strong>in</strong>g such exercises,moreover, one is likely to beg<strong>in</strong> reconsider<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> common assessment <strong>of</strong><strong>Gramsci</strong> as st<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g head <strong>and</strong> shoulders above <strong>the</strong>se o<strong>the</strong>r figures—beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g,for example, with <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>Gramsci</strong> himself identified Len<strong>in</strong> as <strong>the</strong>highest <strong>the</strong>oretician <strong>of</strong> hegemony.As much as <strong>the</strong> self-evidence <strong>of</strong> Marxism’s supposed poverty dependson a widespread, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> many cases <strong>in</strong>herited <strong>the</strong>oretical myopia (amongacademics today it would be scarcely possible to f<strong>in</strong>d someone whobelieves it necessary to read Bukhar<strong>in</strong>, ra<strong>the</strong>r than simply accept <strong>the</strong> commonsense notion <strong>of</strong> classical Marxism as a gray blur <strong>of</strong> “<strong>the</strong>ory”), it isalso important to note that it is propped up by an implicit <strong>and</strong> powerfulpolitical judgment. Marxism st<strong>and</strong>s <strong>in</strong> fact for political failure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mostconspicuous <strong>and</strong> large-scaled sort, <strong>and</strong> for a whole host <strong>of</strong> crimes aga<strong>in</strong>sthumanity. Beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> perceived <strong>the</strong>oretical dullness <strong>and</strong> deficiency st<strong>and</strong>livelier <strong>and</strong> more decisive facts, entrenched <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> our <strong>the</strong>orists<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> common sense <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> epoch: <strong>the</strong> bread l<strong>in</strong>es, <strong>the</strong> gulag, <strong>the</strong>purges, <strong>and</strong> so on.<strong>The</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> this powerful force <strong>in</strong> most cases must be <strong>in</strong>ferred.In expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> need for his “Marxism without guarantees,” Hall speaks<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> “lost dream or illusion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>oretical certa<strong>in</strong>ty.” 20 But where did thisf<strong>in</strong>al disenchantment take place? When did certa<strong>in</strong>ty end, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> slouch<strong>in</strong>gtoward ambiguity, deconstruction <strong>and</strong> undecidability beg<strong>in</strong>? It would benaïve to th<strong>in</strong>k that this occurred at <strong>the</strong> moment when an especially centralconceptual confusion or logical impossibility with<strong>in</strong> Marxist <strong>the</strong>ory wasexposed, or when certa<strong>in</strong> advances <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> philosophy <strong>of</strong> language took place.

10 <strong>Gramsci</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Trotsky</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Shadow</strong> <strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ismAlthough <strong>the</strong> discourse <strong>of</strong> post-Marxism always proceeds on <strong>the</strong> plane <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>ory, it should not be difficult to see that <strong>the</strong> shipwreck <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> communistmovement, <strong>and</strong> most importantly <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Soviet Union, plays a powerful, ifcovert role <strong>in</strong> it. 21 On this question, <strong>in</strong>cidentally, we will not catch <strong>the</strong> WallStreet Journal equivocat<strong>in</strong>g. If it is possible for <strong>the</strong> bourgeois press <strong>and</strong> publicto somewhat playfully reconsider Marx’s legacy, <strong>the</strong> symbols <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> SovietUnion cont<strong>in</strong>ue to haunt <strong>the</strong>ir imag<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>duce a mood <strong>of</strong> terribleseriousness at <strong>the</strong> least provocation. 22In cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g to consider <strong>the</strong> way <strong>in</strong> which post-Marxism underst<strong>and</strong>sclassical Marxism, it should be noted that <strong>the</strong> former does not always present<strong>the</strong> latter as a generic <strong>and</strong> unexam<strong>in</strong>ed construct. Occasionally, classicalMarxism is exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> considerable detail before be<strong>in</strong>g rejected as <strong>in</strong>adequate.But even <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se cases, <strong>the</strong> exam<strong>in</strong>ation is a largely philosophicalmatter. Ernesto Laclau <strong>and</strong> Chantal Mouffe’s critique <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Marxist traditionis a good example <strong>of</strong> this approach. <strong>The</strong> dimension <strong>of</strong> political practiceis unreflectively subsumed <strong>and</strong> taken for granted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> account <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>oretical<strong>in</strong>adequacy <strong>of</strong> Marxism. In this way, a strictly philosophical critiqueis isolated from, <strong>and</strong> made to st<strong>and</strong> for, a serious assessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lessons<strong>of</strong> struggle <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> history <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Marxist movement. <strong>The</strong> most importantproduct <strong>of</strong> this tendency, Hegemony <strong>and</strong> Socialist Strategy, is <strong>the</strong> story <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al essentialism that fatally ta<strong>in</strong>ted Marxism from its <strong>in</strong>ception,<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> difficult philosophical flight from it, which resulted <strong>in</strong> <strong>Gramsci</strong>’sbreakthrough, <strong>and</strong> more decisively <strong>and</strong> importantly <strong>in</strong> Laclau <strong>and</strong> Mouffe’sbreakthrough. <strong>The</strong>ir bitter exchange over <strong>the</strong> merits <strong>of</strong> post-Marxism withNorman Geras follows a similar pattern. Laclau <strong>and</strong> Mouffe’s historicalaccount <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> developments lead<strong>in</strong>g to post-Marxism consists <strong>of</strong> a h<strong>and</strong>ful<strong>of</strong> conventional remarks about <strong>the</strong> failure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Soviet Union <strong>and</strong> a farmore substantive narrative describ<strong>in</strong>g this philosophical escape from orig<strong>in</strong>alessentialism. 23 On this Laclau <strong>and</strong> Mouffe consistently miss <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t<strong>of</strong> Geras’ critique based on <strong>the</strong> political, not philosophical, conditions <strong>of</strong>possibility <strong>of</strong> post-Marxism.From <strong>the</strong> st<strong>and</strong>po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> my argument, Laclau <strong>and</strong> Mouffe’s version<strong>of</strong> post-Marxism, compared to Hall <strong>and</strong> West, certa<strong>in</strong>ly has <strong>the</strong> merit <strong>of</strong>review<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> history, <strong>of</strong> assess<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> differences between, say, Eduard Bernste<strong>in</strong><strong>and</strong> Rosa Luxemburg, or Luxemburg <strong>and</strong> Len<strong>in</strong>. But this variant alsorema<strong>in</strong>s one-sided. In this case, <strong>the</strong> force <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> argument, though displaced<strong>and</strong> refracted, also comes from <strong>the</strong> common sense about <strong>the</strong> political failure<strong>of</strong> Marxism. Why is it possible for Laclau <strong>and</strong> Mouffe to operate largely on<strong>the</strong> philosophical level? Precisely because this political failure is so self-evidentat <strong>the</strong> political level that it need not be discussed.

Introduction 11II. MARXISM IN THE SHADOW OF STALINISM:GRAMSCI AND TROTSKYThus, whe<strong>the</strong>r Marxism serves as <strong>the</strong> drab <strong>and</strong> undifferentiated backgroundon which post-Marxists can pa<strong>in</strong>t <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>the</strong>ory <strong>in</strong> bright colors, or whe<strong>the</strong>rit is unpacked <strong>and</strong> disentangled philosophically before be<strong>in</strong>g set aside, <strong>the</strong>real force, <strong>the</strong> condition <strong>of</strong> possibility for <strong>the</strong>se operations is <strong>the</strong> reality <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>political failure <strong>of</strong> Marxism, at least as perceived by <strong>the</strong>se <strong>the</strong>orists. <strong>The</strong> argumentI develop <strong>in</strong> this work emerges from a desire to contest this perception.In order to do so, it is not possible to proceed start<strong>in</strong>g from a revision <strong>and</strong> re<strong>in</strong>terpretation<strong>of</strong> Marx that disregards <strong>the</strong> movements <strong>and</strong> consequences thatflowed from his political legacy. If, as I have attempted to expla<strong>in</strong>, <strong>the</strong> debatesabout <strong>the</strong> contemporary st<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> Marxism are substantially displaced,<strong>the</strong>n an “<strong>in</strong>nocent” return to Marx, however sympa<strong>the</strong>tic <strong>and</strong> powerful, willnot do. It will not be possible to bypass <strong>the</strong> conscious <strong>and</strong> semiconsciousmental occlusions concern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> historic failure <strong>of</strong> Marxism <strong>in</strong> this way. <strong>The</strong>direction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> analysis needs to be reversed, proceed<strong>in</strong>g not from Marx tous, but by trac<strong>in</strong>g our steps back to him. This book will seek to recover <strong>the</strong>lost thread <strong>of</strong> Marxism at <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> which “certa<strong>in</strong>ty” happened to be lost:amidst <strong>the</strong> crimes <strong>and</strong> horrors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Soviet Union’s degeneration.In effect, <strong>the</strong> debates I have briefly reviewed take place <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> presence<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> proverbial elephant <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> room: Stal<strong>in</strong>ism. <strong>The</strong> post-Marxists pretendnot to notice, <strong>in</strong> part because this problem appears to <strong>the</strong>m as an excessivelyconcrete <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>sufficiently “rich” as a matter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory. More importantly, <strong>the</strong>post-Marxists ignore it because <strong>the</strong> question is already settled <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir m<strong>in</strong>ds.Silently, efficiently, without dem<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g any effort on <strong>the</strong>ir part, Stal<strong>in</strong>ismperforms <strong>the</strong> work <strong>of</strong> demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> necessity <strong>and</strong> righteousness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ircherished prefix. At <strong>the</strong> same time, however, <strong>the</strong> project <strong>and</strong> prospect <strong>of</strong>a revitalization <strong>of</strong> Marxism will not be effective as long as it is allowed torema<strong>in</strong> a generic <strong>and</strong> self-evident tradition <strong>and</strong> pretends that it can afford toignore <strong>the</strong> question <strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ism. Any reconsideration <strong>of</strong> Marxism seek<strong>in</strong>gto do more than provide yet ano<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>terpretive riff on various texts mustaccount for this reality. Marxism needs to situate itself by provid<strong>in</strong>g a morespecific set <strong>of</strong> historical <strong>and</strong> political coord<strong>in</strong>ates, spell<strong>in</strong>g out concretely itsrelation to <strong>and</strong> its distance from <strong>the</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ist degeneration.Accord<strong>in</strong>gly, m<strong>in</strong>e is not a defense <strong>of</strong> Marxism based on its irreducibleplurality. <strong>The</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t is not to spark <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>and</strong> deflect objections by <strong>in</strong>sist<strong>in</strong>gthat beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle label <strong>of</strong> “Marxism” st<strong>and</strong> a multiplicity <strong>of</strong> differentviews. 24 In o<strong>the</strong>r words, it will not do to po<strong>in</strong>t out that Bordiga’s politicalthought <strong>and</strong> practice was <strong>in</strong> fact substantially different from Bukhar<strong>in</strong>’s,

12 <strong>Gramsci</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Trotsky</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Shadow</strong> <strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ismunless <strong>the</strong> political salience <strong>of</strong> this difference can be demonstrated, <strong>and</strong> notjust <strong>in</strong> a historical sense. 25 With this <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d, I chose to focus on two specificfigures <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> pan<strong>the</strong>on <strong>of</strong> Marxism that were politically active <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> period<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1920s <strong>and</strong> 1930s, when <strong>the</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ist degeneration occurred.<strong>The</strong> first figure is an all too familiar one: Antonio <strong>Gramsci</strong>. <strong>The</strong> Italiancommunist enjoys great popularity <strong>in</strong> academia, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> this sense <strong>the</strong> choicedoes not need to be justified. As I have already discussed, <strong>Gramsci</strong> is <strong>the</strong>frequent, nearly obligatory stop <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> typical post-Marxist trajectory. Withfew exceptions, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tellectuals I have discussed as part <strong>of</strong> this broad categoryconsider <strong>Gramsci</strong> to be central to <strong>the</strong>ir agenda. 26 Indeed <strong>Gramsci</strong> is animportant, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> some cases <strong>in</strong>dispensable, figure for a wide range <strong>of</strong> discipl<strong>in</strong>ary<strong>and</strong> cross-discipl<strong>in</strong>ary currents, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g cultural studies, subalternstudies, postcolonial <strong>the</strong>ory, cultural history, pragmatism, critical pedagogy,anthropology, <strong>in</strong>ternational relations, <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> course post-Marxism itself. Myargument is predicated on <strong>the</strong> suspicion that <strong>Gramsci</strong> is popular <strong>in</strong> academiafor <strong>the</strong> wrong reasons.As already shown <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> Hall, West, Laclau, <strong>and</strong> Mouffe, <strong>the</strong>prevail<strong>in</strong>g tendency is to distill <strong>Gramsci</strong>’s <strong>the</strong>ory from Marxist <strong>the</strong>ory <strong>and</strong>practice—to displace <strong>Gramsci</strong> from <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tellectual <strong>and</strong> political traditionto which he belonged. My argument develops <strong>in</strong> opposition this tendency. Iassess <strong>Gramsci</strong> as a Marxist, seek<strong>in</strong>g to discern what he <strong>of</strong>fers to <strong>the</strong> revitalization,not <strong>the</strong> dismissal, <strong>of</strong> this tradition. In exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g this question from<strong>the</strong> st<strong>and</strong>po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> necessity to confront Stal<strong>in</strong>ism directly, however, I alsodevelop a critique <strong>of</strong> those who have attempted to reclaim <strong>Gramsci</strong> for <strong>the</strong>Marxist tradition. My argument beg<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> fact from a consideration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>adequacy <strong>of</strong> this literature, <strong>in</strong>sist<strong>in</strong>g that it is not possible to make sense <strong>of</strong><strong>Gramsci</strong> without putt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> problem <strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ism <strong>in</strong>to focus. I thus expla<strong>in</strong>how <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ist degeneration affected <strong>the</strong> production <strong>of</strong> <strong>Gramsci</strong>as an author <strong>in</strong> significant ways. I <strong>the</strong>n reverse <strong>the</strong> direction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> analysis,us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Gramsci</strong> as an entry-po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> question <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rise <strong>and</strong> consolidation<strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ism. I pose <strong>the</strong> question <strong>of</strong> whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Gramsci</strong> was able todetect <strong>and</strong> underst<strong>and</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ism as a phenomenon, <strong>and</strong> whe<strong>the</strong>r his politicalbehavior as one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> leaders <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Italian Communist Party contributed toits consolidation.Exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g significance <strong>and</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ism <strong>in</strong> thisway, my work must confront certa<strong>in</strong> methodological issues from <strong>the</strong> st<strong>and</strong>po<strong>in</strong>t<strong>of</strong> political <strong>the</strong>ory as a discipl<strong>in</strong>e. In a methodological sense, <strong>in</strong> confront<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> difficult <strong>in</strong>terpretive tasks <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> read<strong>in</strong>g dem<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g texts,I <strong>in</strong>sist on <strong>the</strong> need to underst<strong>and</strong> authors as political actors, <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> aliv<strong>in</strong>g struggle <strong>of</strong> social <strong>and</strong> political forces. <strong>The</strong> texts I exam<strong>in</strong>e are not a

Introduction 13collection <strong>of</strong> desiccated, more or less logical, more or less falsifiable propositions,but can only be understood, let alone put to use, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> thisstruggle. For example, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> next chapter I demonstrate that <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong>production <strong>of</strong> <strong>Gramsci</strong> as an author, <strong>the</strong> way <strong>in</strong> which he was made availablefor academic consumption, was itself saturated with Stal<strong>in</strong>ist erasures<strong>and</strong> distortions that cont<strong>in</strong>ue to affect how he is put to use by contemporaryacademics. Subsequently, I demonstrate that beneath <strong>the</strong> generic <strong>and</strong> purely“<strong>the</strong>oretical” surface <strong>of</strong> <strong>Gramsci</strong>’s prison writ<strong>in</strong>gs lurks a labyr<strong>in</strong>th <strong>of</strong> politicalwarn<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> judgments that is simply un<strong>in</strong>telligible without an underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> complex struggles that were tak<strong>in</strong>g place with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> communistmovement at that time. My work <strong>in</strong>sists, <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r words, on <strong>the</strong> ties thatb<strong>in</strong>d political <strong>the</strong>ory to political practice as a methodological imperative for<strong>the</strong> task <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretation.<strong>The</strong> question <strong>of</strong> methodology is even more press<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> Leon<strong>Trotsky</strong>, <strong>the</strong> second figure I exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> this work. This is true for <strong>the</strong> simplereason that while <strong>Gramsci</strong> is a highly regarded th<strong>in</strong>ker, political <strong>the</strong>ory hasvirtually ignored <strong>Trotsky</strong>. <strong>The</strong> problem here is <strong>in</strong> part expla<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong> factthat <strong>Trotsky</strong> was <strong>the</strong> victim <strong>of</strong> a process <strong>of</strong> systematic distortion <strong>and</strong> erasure<strong>of</strong> unprecedented scale, eclips<strong>in</strong>g that which affected <strong>Gramsci</strong>. In addition,<strong>the</strong> dichotomies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cold war cont<strong>in</strong>ued to squeeze <strong>Trotsky</strong>’s legacy out <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> field <strong>of</strong> what is politically legitimate or even conceivable. Yet this processwas never complete, <strong>and</strong> <strong>Trotsky</strong>’s legacy was never fully suppressed. In thissense, my work is an attempt to call attention to this tradition as a lost treasure,half-buried <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> political ru<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> Stal<strong>in</strong>ized Marxism. More specifically,I make <strong>the</strong> case that <strong>Trotsky</strong>’s <strong>the</strong>oretical underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>and</strong> politicalopposition to Stal<strong>in</strong>ism constitute an important resource for <strong>the</strong> sort <strong>of</strong> revitalization<strong>of</strong> Marxism I have discussed here. From this st<strong>and</strong>po<strong>in</strong>t, I suggestthat while <strong>Gramsci</strong> may be useful, <strong>Trotsky</strong> is <strong>in</strong>dispensable. 27Aside from <strong>the</strong> broader historical processes that obscured his legacy, <strong>the</strong>absence <strong>of</strong> <strong>Trotsky</strong> from <strong>the</strong> field <strong>of</strong> political <strong>the</strong>ory must also be expla<strong>in</strong>edby <strong>the</strong> discipl<strong>in</strong>ary parameters <strong>of</strong> political <strong>the</strong>ory itself. <strong>The</strong> same type <strong>of</strong>tendencies <strong>of</strong> textual <strong>and</strong> philosophical reductionism, <strong>of</strong> political neutralization<strong>and</strong> domestication that I have already identified as characteristic <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> post-Marxist approach to Marx <strong>and</strong> <strong>Gramsci</strong>, are certa<strong>in</strong>ly not alien topolitical <strong>the</strong>ory. Indeed, many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> figures I discussed <strong>in</strong> this <strong>in</strong>troduction—Laclau,Mouffe, Carver—f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong>ir discipl<strong>in</strong>ary home <strong>in</strong> political<strong>the</strong>ory. However, s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>re is no comparable body <strong>of</strong> academic literaturedevoted to <strong>Trotsky</strong> as <strong>the</strong>re is for Marx <strong>and</strong> <strong>Gramsci</strong>, <strong>the</strong> process <strong>in</strong>volvedhere is quite different. <strong>Trotsky</strong> is not <strong>the</strong> pivot for <strong>the</strong> tendentious operations<strong>of</strong> post-Marxism. He is not at <strong>the</strong> center <strong>of</strong> any tempest <strong>in</strong> academic