Improved livelihoods and governance of natural resources ... - WWF

Improved livelihoods and governance of natural resources ... - WWF

Improved livelihoods and governance of natural resources ... - WWF

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

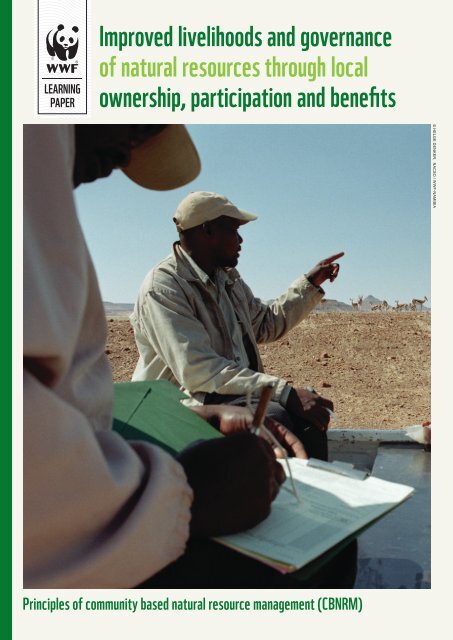

© HELGE DENKER, NACSO / <strong>WWF</strong>-NAMIBIALEARNINGPAPER<strong>Improved</strong> <strong>livelihoods</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>governance</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>natural</strong> <strong>resources</strong> through localownership, participation <strong>and</strong> benefitsPrinciples <strong>of</strong> community based <strong>natural</strong> resource management (CBNRM)

Written by Melissa de KockCover design by: Malin Redvall / www.reddesign.noFront cover photo: Helge Denker, NACSO / <strong>WWF</strong>-NamibiaPrinted by Weberg printshopPublished in December 2010 by <strong>WWF</strong>-World Wide Fund ForNature (Formerly World Wildlife Fund), Oslo, NorwayAny reproduction in full or in part must mention the title <strong>and</strong>credit the above-mentioned publisher as the copyright owner.© Text 2010 <strong>WWF</strong>All rights reserved<strong>WWF</strong> is one <strong>of</strong> the world’s largest <strong>and</strong> most experiencedindependent conservation organizations, with over5 million supporters <strong>and</strong> a global Network active inmore than 100 countries.<strong>WWF</strong>’s mission is to stop the degradation <strong>of</strong> the planet’s<strong>natural</strong> environment <strong>and</strong> to build a future in which humans livein harmony with nature, by conserving the world’s biologicaldiversity, ensuring that the use <strong>of</strong> renewable <strong>natural</strong> <strong>resources</strong>is sustainable, <strong>and</strong> promoting

TABLE OF CONTENTS1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................12. WHAT IS CBNRM..........................................................................................................................13. RELEVANCE FOR <strong>WWF</strong>-NORWAY.............................................................................................34. CORE PRINCIPLES OF SUSTAINABLE CBNRM.......................................................................44.1 Core principles relevant at a strategic / policy level.....................................................................44.2 Core principles <strong>of</strong> sustainable CBNRM relevant for practical programme implementation ........7CASE STUDY: CONSERVATION SUCCESS AND IMPROVED LIVELIHOODS FROM CBNRM ..11

8. The community that will manage <strong>and</strong> benefit from the resource <strong>and</strong> the geographic extent <strong>of</strong> the resource which will be managed, must be clearly defined by the community itself, <strong>and</strong> legitimised by the government. This will provide both internal <strong>and</strong> external legitimacy, circumvent conflict over who is meant to manage <strong>and</strong> benefit, <strong>and</strong> prevent exploitation <strong>of</strong> the resource by outsiders. If the community defines itself, there is greater potential for developing an authority with required external <strong>and</strong> internal legitimacy xxx . This will also contribute to the sense <strong>of</strong> ownership (see point 3.1(7)), <strong>and</strong> to self determination <strong>and</strong> thus empowerment which also is an important benefit <strong>of</strong> successful CBNRM. 9. Equitable partnerships, collaboration <strong>and</strong> trust between local communities <strong>and</strong> the public <strong>and</strong> private sector are required. Such partnerships include those between the community <strong>and</strong> government agencies, with NGOs -‐ as supporters for communities <strong>and</strong> as supporters or challengers where necessary <strong>of</strong> governments -‐, <strong>and</strong> with the private sector investors. There is a potential imbalance <strong>of</strong> power between communities <strong>and</strong> the government <strong>and</strong> with private sector partners which can be addressed by facilitation <strong>and</strong> technical support from an external agency <strong>and</strong> provision <strong>of</strong> capacity building, <strong>and</strong> through security <strong>of</strong> tenure for communities <strong>and</strong> their knowledge <strong>of</strong> their rights xxxi . Trust is crucial to partnerships <strong>and</strong> building trust with communities <strong>and</strong> between communities <strong>and</strong> other stakeholders may take time, particularly if there have been failed interventions previously or other stakeholders have not treated them equitably in the past. CBNRM in southern Africa has been facilitated through successful longterm collaborations between communities <strong>and</strong> governments assisted by support organisations. For example, the CAMPFIRE Association (Zimbabwe) or the Namibian Association <strong>of</strong> CBNRM Support Organisations (NASCO), provide capacity building, technical support <strong>and</strong> policy inputs to communities <strong>and</strong> government partners <strong>and</strong>, as such, are crucial in promoting CBNRM in those countries xxxii . 4.2 Core principles <strong>of</strong> sustainable CBNRM relevant for practical programme implementation Both sets <strong>of</strong> principles outlined in points 3.1 above <strong>and</strong> 3.2 below are required for sustainable CBNRM. The principles outlined in point 3.1 above lay the foundation for sustainable CBNRM, <strong>and</strong> need to be in place before, or be put in place while, the principles below are applied. Similarly, the principles below need to be applied in practical programme implementation to complement those in 3.1. Implemented in synergy, they will contribute to sustainable CBNRM. 1. Capacity building is required to ensure that community members <strong>and</strong> their institutions have the required knowledge, skills <strong>and</strong> expertise to manage the <strong>resources</strong> <strong>and</strong> resulting income, <strong>and</strong> to negotiate with (<strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong> up to) other stakeholders xxxiii . There may be barriers hindering people from participating effectively in planning processes <strong>and</strong> from management, which need to be 7

• Monitoring <strong>and</strong> reporting <strong>of</strong> CBNRM impacts <strong>and</strong> results is required against biodiversity, <strong>livelihoods</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>governance</strong> indicators. This is required to justify continued donor investment, <strong>and</strong> to prove its value as a preferred l<strong>and</strong> use option for governments. • CBNRM can also be affected by myriad external factors, such as political change, <strong>natural</strong> ecosystem dynamics, climate change, etc. xlviii . Please refer to the following case study for an example <strong>of</strong> successful CBNRM. CASE STUDY: CONSERVATION SUCCESS AND IMPROVED LIVELIHOODS FROM CBNRM The Namibian Conservancy programme, a government programme supported by a number <strong>of</strong> NGOs including <strong>WWF</strong>, enables local people living on communal l<strong>and</strong>s to use wildlife <strong>and</strong> nature-‐based tourism enterprises as an additional livelihood strategy once registered as a communal ‘conservancy’. Conservancies are multiple-‐use areas, in other words, community members continue with their usual subsistence activities such as livestock or agriculture alongside wildlife management, according to a management plan which includes zones for multiple use, tourism <strong>and</strong> wildlife. Through far sighted legislation passed in 1996, the Government transferred rights over (certain species <strong>of</strong>) wildlife to communities, if registered as a conservancy, <strong>and</strong> enabled those communities to manage <strong>and</strong> use the wildlife within their demarcated Conservancy for their own benefit, primarily through hunting <strong>and</strong> photographic tourism initiatives. Communities have the right to enter into agreements with private sector partners for the use <strong>of</strong> the wildlife, <strong>and</strong> retain all revenue generated through those agreements. The community elects a representative community institution who manages the conservancy on the community’s behalf. Communal conservancies cover 16.1% <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> in Namibia, complementing the state managed protected area network which comprises 16.5% <strong>of</strong> the country. More than 230 000 community members are involved <strong>and</strong> benefit from conservancies <strong>and</strong> the broader CBNRM Programme, which is approximately 10% <strong>of</strong> the country’s population. Income <strong>and</strong> benefits from Namibia’s CBNRM Programme increased from approximately N$600,000 in 1998 (four conservancies) to N$35 million in 2009 (59 conservancies) xlix . This income is supplementary income for these communities who are primarily subsistence farmers. This additional money remains within the community, <strong>and</strong> is used as determined by the community to fund conservancy operations, <strong>and</strong> to distribute to individuals or villages <strong>and</strong> to undertake community 11

projects. In the case <strong>of</strong> village payouts, the villages collectively decide how to spend that money <strong>and</strong> have constructed maize storage facilities, school buildings, ceremonial buildings, <strong>and</strong> boreholes, which benefit the whole village <strong>and</strong> which would not have been possible without that money l . It is rare that CBNRM becomes the sole or even primary source <strong>of</strong> income for rural people living on communal l<strong>and</strong>, but rather the CBNRM income or benefits are supplementary to people’s existing <strong>livelihoods</strong> (e.g. farming) <strong>and</strong> are valuable as an additional livelihood diversification strategy li . The community in a registered conservancy retains all the revenue generated from the conservancy, for example from hunting <strong>and</strong> tourism concessions <strong>and</strong>/or community campsites. Since inception <strong>of</strong> the programme in the mid-‐1990s, the attitudes <strong>of</strong> many local communal area residents have changed from resentment <strong>of</strong> the state managed wildlife system where the state received all benefits, whilst the community bore the brunt <strong>of</strong> wildlife in their area, to seeing wildlife as a community asset. Prior to the formation <strong>of</strong> communal conservancies, wildlife was largely regarded as competition to livestock grazing <strong>and</strong>/or despised as a threat to personal assets (i.e., crops, livestock, <strong>and</strong> infrastructure) or even the lives <strong>of</strong> one’s family. Poaching is no longer socially acceptable <strong>and</strong> the presence <strong>of</strong> wildlife is being promoted through participatory community l<strong>and</strong>-‐use zoning processes which create core wildlife (wildlife only) <strong>and</strong> multiple-‐use (wildlife mixed with livestock <strong>and</strong> people) areas in which wildlife numbers are increasing <strong>and</strong> flourishing lii . The change in attitudes is attributable to the increased income <strong>and</strong> other benefits local communities receive from wildlife enterprises <strong>and</strong> management liii . While economic benefits, such as income or employment, are easier to quantify, other important benefits for communities are less quantifiable socio-‐cultural benefits such as participation in decision-‐making <strong>and</strong> authority to make decisions regarding the resource (i.e. empowerment) <strong>and</strong> receipt <strong>of</strong> meat from hunted wildlife to supplement diets. The change in attitude has resulted in improved <strong>governance</strong> over the wildlife <strong>and</strong> a significant recovery <strong>of</strong> wildlife populations, with population trends <strong>of</strong> all species (with the exception <strong>of</strong> lion <strong>and</strong> hyena in some conservancies in the north east <strong>of</strong> Namibia) either stable or increasing. The increasing wildlife populations have resulted in increased tangible benefits for the communities – including cash pay-‐outs, job creation, tourism enterprise development, meat (from trophy hunting) livlv . Increasing wildlife numbers include lions which, in the Kunene have increased from approximately 30 to an estimated 125 by 2008 lvi <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong>ed their range by several thous<strong>and</strong> square kilometres. Such a recovery was only possible because it was accompanied by a massive recovery <strong>of</strong> the prey base <strong>and</strong> increased tolerance by resident communities. Namibia is the only country in the world where populations <strong>of</strong> black rhino outside protected areas are rising (Weaver, Petersen, Diggle <strong>and</strong> Matongo, 2010). The free-‐roaming black rhino population has more than doubled from 1990 to 2008 in the north-western communal <strong>and</strong> state l<strong>and</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> elephant numbers have increased from approximately 7,000 in 1995 to more than 16,000 by 2008. 12

End notes i Jones <strong>and</strong> Murphree 2004 ii Emerton 2001; Fabricius, Matsiliza <strong>and</strong> Sisitka 2002; Child <strong>and</strong> West Lyman 2005 iii ARD, 2001 iv Weaver <strong>and</strong> Skyer 2005 v Magome <strong>and</strong> Fabricius, 2005; Weaver <strong>and</strong> Skyer, 2005; Fischer, Muchapondwa & Sterner 2005; Atwell, 2005 vi Hamilton et. al. 2007; Mbewe et. al 2005 vii Weaver et al 2010; NACSO, 2010 viii SCBD <strong>and</strong> UNDP 2008; Rights <strong>and</strong> Resources 2008; Weaver <strong>and</strong> Skyyer 2005; de Kock 2007 ix UN 1993a x UN 1993b xi UN 1992 xii ILO Convention 169 1989 xiii UN 2007 xiv Murphree 1991 as cited in Murphree 2005; IIED 1994; Gibson <strong>and</strong> Marks 1995; Child <strong>and</strong> West Lyman 2005; Fabricius, Matsiliza <strong>and</strong> Sisitka, 2002; Fabricius et al. 2005; Jones <strong>and</strong> Murphree 2004; Schuerholz <strong>and</strong> Baldus 2007 xv Fabricius 2005 xvi Fabricius, Matsiliza <strong>and</strong> Sisitka, 2002; Fabricius et al., 2005; Jones <strong>and</strong> Murphree, 2004; Child <strong>and</strong> West Lyman, 2005; Child, 2005a xvii Fabricius, 2005 xviii Fabricius et al. 2005; Child <strong>and</strong> West Lyman, 2005; Murphree, 2005; Jones <strong>and</strong> Murphree, 2004; Child 2003; Metcalfe, 1996 xix Barrow <strong>and</strong> Murphree 1998; Fabricius et al. 2005; Bond et al. 2010 xx Murphree, 1991 cited in Murphree, 1995; Gibson <strong>and</strong> Marks, 1995; Emerton, 2001; Jones <strong>and</strong> Murphree, 2004; Barrow <strong>and</strong> Murphree, 1998; Fabricius, Matsiliza <strong>and</strong> Sisitka, 2005 xxi Barrow <strong>and</strong> Murphree 1998; Fabricius, Matsiliza <strong>and</strong> Sisitka 2002; Fabricius et al. 2005 xxii Child 2003 xxiii Child 2003 xxiv Barrow <strong>and</strong> Murphree 1998 xxv IIED 1994; MET 2005 xxvi Bond et al 2010 xxvii Barrow <strong>and</strong> Murphree 1998; Turner 2005 xxviii S<strong>and</strong>with et al. 2001; Metcalfe 2003 xxix Child, 2003; Weaver <strong>and</strong> Skyer, 2005:90; Barrow <strong>and</strong> Murphree, 1998 xxx Jones <strong>and</strong> Murphree 2004; Atwell 2005 xxxi Jones <strong>and</strong> Murphree 2004 xxxii Bond et al. 2010 xxxiii Child, 2003, Child <strong>and</strong> West Lyman 2005; IIED 1994 xxxiv Child 2003; Child <strong>and</strong> West-‐Lyman 2005 xxxv Fabricius, Matsiliza <strong>and</strong> Sisitka 2002; Fabricius et al. 2005 xxxvi Fabricius et al. 2005 xxxvii Jones, 1998; Child <strong>and</strong> West Lyman, 2005; Fabricius, Matsiliza <strong>and</strong> Sisitka, 2002; Fabricius et al., 2005 xxxviii Child <strong>and</strong> West Lyman 2005 xxxix Atwell 2005 xl Barrow <strong>and</strong> Murphree, 1998 xli Adams <strong>and</strong> Hulme, 2001; Jones <strong>and</strong> Murphree, 2004; Child <strong>and</strong> West Lyman, 2005) xlii Adams <strong>and</strong> Hulme, 2001; Jones <strong>and</strong> Murphree, 2004 xliii Jones, 1999 xliv S<strong>and</strong>with et al. 2001; Bh<strong>and</strong>ari 2003; Norton et al. 2001; Taylor 2001; Berkes 2003; du Pisani <strong>and</strong> S<strong>and</strong>ham 2006 14

xlv Jones <strong>and</strong> Murphree, 2004 xlvi Magome <strong>and</strong> Fabricius, 2005 xlvii Jones <strong>and</strong> Murphree 2004; Atwell 2005 xlviii Magome <strong>and</strong> Fabricius, 2005 xlix NACSO 2010 l de Kock 2007 li Magome <strong>and</strong> Fabricius 2005; Weaver <strong>and</strong> Skyer 2005 lii Weaver et al 2010 liii Weaver <strong>and</strong> Skyer 2005 liv Jones 1998; Child 2003; Weaver <strong>and</strong> Skyer 2005; Nott <strong>and</strong> Jacobsohn 2005; Weaver et al, 2010 lv Weaver et al 2010; NACSO, 2010 lvi P. St<strong>and</strong>er, 2008 in NACSO, 2010 lvii <strong>WWF</strong> in Namibia 2010 References Adams, W.M. <strong>and</strong> Hulme, D. (2001b). “Changing Narratives, Policies <strong>and</strong> Practices in African Conservation.” In Hulme, D <strong>and</strong> Murphree, M (eds) African Wildlife <strong>and</strong> Livelihoods. The promise <strong>and</strong> performance <strong>of</strong> Community Conservation. Cape Town, David Philips. Anstey, S. (2009). Institutional Change And Community Based Natural Resource Management In Northern Mozambique: The Village Goes Forward: Governance <strong>and</strong> Natural Resources in North Niassa Centre for Applied Social Sciences, University <strong>of</strong> Zimbabwe, May 2009 Atwell, C.A.M. (2005). “Review <strong>of</strong> CBNRM activities in the Region.” The Feasibility Study Draft Report regarding the Development <strong>of</strong> the Limpopo National Park <strong>and</strong> its Support Zone. Development Bank <strong>of</strong> Southern Africa, Agence Française de Developpement <strong>and</strong> the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Tourism <strong>of</strong> Mozambique. Nepad Project Proposal <strong>and</strong> Feasibility Fund. October 2005 Barrow, E. <strong>and</strong> Murphree, M. (1998). “Community Conservation from concept to Practice: A practical framework.” Community Conservation Research in Africa: Principles <strong>and</strong> Comparative Practice. Working Papers. Paper No. 8. Institute for Development Policy <strong>and</strong> Management, University <strong>of</strong> Manchester. August 1998. http://www.sed.manchester.ac.uk/idpm/publications/archive/cc/cc_wp08.pdf Bond, I., Chambwera, M., Jones, B., Chundama, M. <strong>and</strong> Nhantumbo, I. (2010) REDD+ in dryl<strong>and</strong> forests: Issues <strong>and</strong> prospects for pro-‐poor REDD in the miombo woodl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> southern Africa, Natural Resource Issues No. 21. IIED, London. Child, B (2005) “Principles, practice, <strong>and</strong> results <strong>of</strong> CBNRM in Southern Africa.” In Child, B. <strong>and</strong> West Lyman, M (eds) Natural Resources as community assets. S<strong>and</strong> County Foundation <strong>and</strong> the Aspen Institute. Child, B <strong>and</strong> West Lyman, M. (2005). “Introduction.” In Child, B. <strong>and</strong> West Lyman, M (eds) Natural Resources as communityassets. S<strong>and</strong> County Foundation <strong>and</strong> the Aspen Institute. Child, B. (2003). Origins <strong>and</strong> Efficacy <strong>of</strong> Modern CBNRM Practices in the Southern African Region. Corbett, A. <strong>and</strong> Jones, B. (2000). The legal aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>governance</strong> in CBNRM in Namibia. Paper prepared for the CASS / PLAAS second regional meeting, on the legal aspects <strong>of</strong> <strong>governance</strong> in CBNRM, University <strong>of</strong> the Western Cape, 16-‐17 October 2000. De Kock, M. (2007). Exploring the efficacy <strong>of</strong> community based <strong>natural</strong> resource management in Salambala Conservancy, Caprivi Region, Namibia. University <strong>of</strong> Stellenbosch, South Africa. Emerton, L. (2001). “The Nature <strong>of</strong> benefits <strong>and</strong> the benefits <strong>of</strong> nature: Why wildlife conservation has not economically benefited communities in Africa.” In Hulme, D <strong>and</strong> Murphree, M (eds) African Wildlife <strong>and</strong> Livelihoods. The promise <strong>and</strong> performance <strong>of</strong> Community Conservation. Cape Town, David Philips. Fabricius, C. (2005). “The fundamentals <strong>of</strong> community-‐based <strong>natural</strong> resource management.” In Fabricius, C. <strong>and</strong> Koch, E. with Magome, H. <strong>and</strong> Turner, S. (eds Rights, Resources <strong>and</strong> Rural Development: Community-‐based Natural Resource Management in Southern Africa. Earthscan Publications Limited. London, UK. Fabricius, C., Koch, E., Turner, S., Magome, H. <strong>and</strong> Sisitka, L. (2005). “Conclusions <strong>and</strong> recommendations: What we have learned from a decade <strong>of</strong> experimentation.” In Fabricius, C. <strong>and</strong> Koch, E. with Magome, H. <strong>and</strong> 15

Turner, S. (eds) Rights, Resources <strong>and</strong> Rural Development: Community-‐based Natural Resource Management inSouthern Africa. Earthscan Publications Limited. London, UK. Fabricius, C., Matsiliza, B., & Sisitka, L. (2002). An update <strong>of</strong> laws <strong>and</strong> policies that support community-based <strong>natural</strong> resource management (CBNRM) type programmes in South Africa. (Final Draft). Report to the Department <strong>of</strong> Environmental Affairs <strong>and</strong> Tourism (South Africa) <strong>and</strong> GTZ. August 2002. Gibson, C.G. <strong>and</strong> Marks, S.A. (1995) “Transforming rural hunters into conservationists: An assessment <strong>of</strong> Community-‐based Wildlife Management Programs in Africa”, World Development 23 (b) 941-‐958. Goodwin, J., <strong>and</strong> Edmunds C.(2004). Contribution <strong>of</strong> Tourism to Poverty Alleviation to Pro Poor Tourism <strong>and</strong> the Challenge <strong>of</strong> Measuring Impacts. Transport Policy <strong>and</strong> Tourism Section, Transport Division UN ESCAP Hamilton, K, Tembo, G, Sinyenga, G., B<strong>and</strong>yopadhyay, S., Pope, A., Guilton, B., Muwele, B., Mann S. & Pavy, JM (2007). The Real Economic Impact <strong>of</strong> Nature Tourism in Zambia. NRCF, Lusaka, Zambia. Edited by Camilla Hebo Buus. IIED (1994). Whose Eden? An overview <strong>of</strong> Community Approaches to Wildlife Management. London, International Institute for Environment <strong>and</strong> Development. ILO (1989). C169 Indigenous <strong>and</strong> Tribal Peoples Convention. (ILO169), 1989. Jones, B. (1998). Namibia’s approach to Community-‐based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM): Towards sustainable development in communal areas. Sc<strong>and</strong>inavian Seminar College: African Perspectives <strong>of</strong> Policies <strong>and</strong> Practices 112 Supporting Sustainable Development in Sub-‐Saharan Africa. Windhoek, September 1998. Jones, B. (1999). “Rights, Revenue <strong>and</strong> Resources: The problems <strong>and</strong> potential <strong>of</strong> conservancies as community wildlife management institutions in Namibia.” Evaluating Eden Series Discussion paper No. 2. September 1999. Jones, B. <strong>and</strong> Murphree, M.W. (2004). “Community-‐Based Natural Resource Management as a Conservation Mechanism: Lessons <strong>and</strong> Directions”. In Child, B. (ed) Parks in Transition. Biodiversity, Rural Development <strong>and</strong> the Bottom Line. Published for IUCN <strong>and</strong> SASUSG by Earthscan Publications Limited. London, UK. Mbewe, B., Makota, C., Hachileka, E., Mwitwa, J., Chundama, M. <strong>and</strong> Nanchengwa, M. (2005). Community Based Natural Resource Management in Zambia. Status Report 2005. <strong>WWF</strong> / Zambia CBNRM Forum. Metcalfe, S (2003). Impacts <strong>of</strong> Transboundary Protected Areas on Local Communities in Three Southern African Initiatives. Paper prepared for the workshop on Transboundary Protected Areas in the Governance Stream <strong>of</strong> the 5th World Parks Congress, Durban, South Africa, 12-‐13 September 2003. Murphree, M.J. (2005). “Counting Sheep”: The Comparative Advantages <strong>of</strong> Wildlife <strong>and</strong> Livestock – A Community Perspective.” In Os<strong>of</strong>sky, S.A., Cleavel<strong>and</strong>, S., Karesh, W.B., Kock, M.D., Nyhus, P.J., Starr, L. <strong>and</strong> Yang, A. (Eds). Conservation <strong>and</strong> Development Interventions at the Wildlife / Livestock Interface: Implications for Wildlife, Livestock <strong>and</strong> Human Health. IUCN, Gl<strong>and</strong>, Switzerl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Cambridge Murphree, M.W. (2005). “Congruent Objectives, Competing Interests, <strong>and</strong> Strategic Compromise: Concept <strong>and</strong> Process in the evolution <strong>of</strong> Zimbabwe’s CAMPFIRE, 1984-‐1996”. In Brosius, J. P., Tsing, A.L. <strong>and</strong> Zerner, C. (eds) Communities <strong>and</strong> Conservation. History <strong>and</strong> Policies <strong>of</strong> Community-‐based Natural Resource Management. AltaMira Press. Walnut Creek, USA. NACSO. 2010. Namibia’s communal conservancies: a review <strong>of</strong> progress <strong>and</strong> challenges in 2009. NACSO, Windhoek. Nott, C <strong>and</strong> Jacobsohn, M (2005). “Key Issues in Namibia’s conservancy movement.” In Fabricius, C. <strong>and</strong> Koch, E. with Magome, H. <strong>and</strong> Turner, S. (eds) Rights, Resources <strong>and</strong> Rural Development: Community-‐based Natural Resource Management in Southern Africa. Earthscan Publications Limited. London, UK. Rights <strong>and</strong> Resources (2008). From Exclusion to Ownership? Rights <strong>and</strong> Resources Initiative, 2008, Washington, USA. www.rights<strong>and</strong><strong>resources</strong>.org Roe D., Nelson, F., S<strong>and</strong>brook, C. (eds.) 2009. Community management <strong>of</strong> <strong>natural</strong> <strong>resources</strong> in Africa: Impacts, experiences <strong>and</strong> future directions, Natural Resource Issues No. 18, International Institute for Environment <strong>and</strong> Development, London, UK S<strong>and</strong>with, T. Shine, C., Hamilton, L. <strong>and</strong> Sheppard, D. (2001). Transboundary Protected Areas for Peace <strong>and</strong> Cooperation. IUCN – Gl<strong>and</strong>, Switzerl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Cambridge, UK 16

Secretariat <strong>of</strong> the Convention on Biological Diversity (SCBD) <strong>and</strong> United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2008) Global Indigenous Peoples Consultation on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation <strong>and</strong> Forest Degradation (REDD), Baguio City, Philippines 12-‐14 November 2008, Summary Report, CBD Secretariat). Tsing, A.L., Brosius, J.P., <strong>and</strong> Zerner, C. (2005) “Introduction.” In Brosius, J.P., Tsing, A.L. <strong>and</strong> Zerner, C. (eds) Communities <strong>and</strong> Conservation. History <strong>and</strong> Policies <strong>of</strong> Community-‐based Natural Resource Management. AltaMira Press. Walnut Creek, USA. Turner, S. (2004). A crisis in CBNRM? Affirming the commons in southern Africa. Paper presented at the 10th IASCP Conference, Oaxaca, 9-‐13th August 2004. Centre for International Co-‐operation, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Turner, S. (2005). “Community-‐based <strong>natural</strong> resource management <strong>and</strong> rural <strong>livelihoods</strong>”. In Fabricius, C. <strong>and</strong> Koch, E. with Magome, H. <strong>and</strong> Turner, S. (eds) Rights Resources <strong>and</strong> Rural Development: Community-‐based Natural Resource Management in Southern Africa. Earthscan Publications Limited. London, UK. Weaver, L.C, <strong>and</strong> Skyer, P (2005). “Conservancies: Integrating Wildlife L<strong>and</strong>-‐use options into the Livelihood, Development <strong>and</strong> Conservation Strategies <strong>of</strong> Namibian Conservancies.” In Os<strong>of</strong>sky, S.A., Cleavel<strong>and</strong>, S., Karesh, W.B., Kock, M.D., Nyhus, P.J., Starr, L. <strong>and</strong> Yang, A. (Eds). Conservation <strong>and</strong> Development Interventions at the Wildlife / Livestock Interface: Implications for Wildlife, Livestock <strong>and</strong> Human Health. IUCN, Gl<strong>and</strong>, Switzerl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Cambridge, UK. United Nations (UN). (1993a). Agenda 21: Earth Summit -‐The United Nations Programme <strong>of</strong> Action from Rio. http://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/documents/agenda21/english/agenda21toc.htm United Nations (UN). (1993b) Multilateral Convention on Biological Diversity. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. United Nations Treaty Series. p142-‐382.: http://www.biodiv.org/convention/articles.asp United Nations (UN). (2007). United Nations Declaration on the Rights <strong>of</strong> Indigenous Peoples. Adopted by the UN at the 107th plenary meeting. 13 September 2007. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf Weaver, L.C., Petersen, T., Diggle, R., <strong>and</strong> Matongo, G. (2010) A Decade <strong>of</strong> Wildlife Utilization in Namibia’s Communal Conservancies. 17

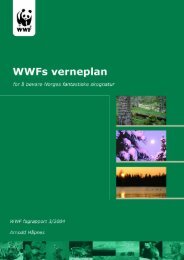

LIMPROVED LIVELIHOODS AND GOVERNANCEOF NATURAL RESOURCESINCENTIVE BASEDAPPROACH TONATURAL RESOURCEMANAGEMENT– Communities receiveequitable benefits whichoutweigh the negativeimpacts <strong>of</strong> conservation.PARTICIPATIONAND OWNERSHIPIMPROVED NATURALRESOURCE MANAGEMENT– Successful CBNRM results inimproved biodiversity <strong>and</strong> habitatconservation <strong>and</strong> increasedwildlife numbers <strong>and</strong> range.– Communities makethe decisions over their<strong>resources</strong>.Why we are hereTo stop the degradation <strong>of</strong> the planet’s <strong>natural</strong> environment <strong>and</strong>to build a future in which humans live in harmony <strong>and</strong> nature.POLICY ANDLEGISLATION– Community rightsshould be enshrinedin national policies<strong>and</strong> legislation.100%RECYCLED• IMPROVED LIVELIHOODS AND GOVERNANCE OF NATURAL RESOURCES THROUGH LOCAL OWNERSHIP, PARTICIPATION AND BENEFITS •ularWhy we are hereTo stop the degradation <strong>of</strong> the planet’s <strong>natural</strong> environment <strong>and</strong>to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature.www.wwf.no<strong>WWF</strong>-Norge, organisasjonsnr 952330071MVA og registrert i Norge med reg.nos. © 1989 p<strong>and</strong>asymboletog ® “<strong>WWF</strong>” registrert varemerke av Stiftelsen <strong>WWF</strong> Verdens Naturfond (World Wide Fund for Nature),<strong>WWF</strong>-Norge, Postboks 6784 St Olavs plass, 0130 Oslo, tlf: 22 03 65 00, epost: wwf@wwf.no, www.wwf.no.© NASA<strong>WWF</strong>.NO