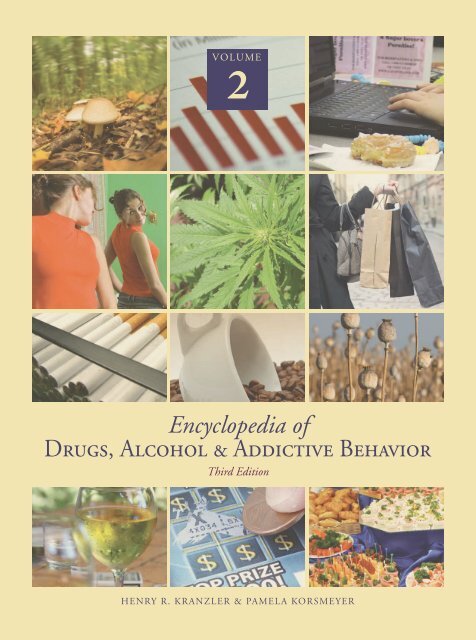

Encyclopedia of Drugs, Alcohol & Addictive Behavior

Encyclopedia of Drugs, Alcohol & Addictive Behavior

Encyclopedia of Drugs, Alcohol & Addictive Behavior

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

VOLUME<br />

2<br />

<strong>Encyclopedia</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Drugs</strong>, <strong>Alcohol</strong> & <strong>Addictive</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong><br />

Third Edition<br />

HENRY R. KRANZLER & PAMELA KORSMEYER

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF<br />

DRUGS, ALCOHOL<br />

& ADDICTIVE<br />

BEHAVIOR<br />

THIRD EDITION<br />

Volume 2<br />

D–L<br />

Pamela Korsmeyer and Henry R. Kranzler<br />

EDITORS IN CHIEF

DAST. See Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST).<br />

n<br />

DELIRIUM. The primary clinical feature <strong>of</strong><br />

delirium is the disturbance <strong>of</strong> consciousness and/<br />

or attention. Associated symptoms are disorientation,<br />

memory deficits, and language or perceptual<br />

disturbances. Any cognitive function may be affected.<br />

Fleeting false beliefs, including paranoid ideas, are<br />

common but usually short-lived. Additional clinical<br />

symptoms include sleep/wake cycle disturbances<br />

(insomnia, daytime drowsiness, sleep/wake cycle<br />

reversal, nocturnal worsening <strong>of</strong> symptoms), increased<br />

or decreased psychomotor activity, increased or<br />

decreased flow <strong>of</strong> speech, increased startle reaction,<br />

and emotional disturbances (irritability, depression,<br />

euphoria, anxiety, apathy). Delirium develops within<br />

hours to days, and its symptoms fluctuate over<br />

time. Although many cases <strong>of</strong> delirium resolve<br />

promptly with the treatment <strong>of</strong> the underlying<br />

cause, symptoms may persist for months after treatment,<br />

especially in the elderly. Sometimes an episode<br />

<strong>of</strong> delirium establishes a new, lower cognitive<br />

baseline.<br />

Regarding epidemiology, the community prevalence<br />

<strong>of</strong> delirium is age-dependent: 0.4 percent in<br />

those over 18, 1.1 percent in those over 55 and<br />

13.6 percent in those over 85 (Folstein, Bassett,<br />

Romanowsk, et al., 1993). Delirium is common in<br />

the hospital setting: 11 to 42 percent. Among the<br />

elderly presenting for hospital admission, 24<br />

D<br />

percent <strong>of</strong> community dwelling and 64 percent <strong>of</strong><br />

nursing home residents are delirious. Delirium is<br />

associated with increased morbidity and mortality.<br />

For example, 25 percent <strong>of</strong> elderly patients with<br />

delirium during hospitalization die within six<br />

months after discharge (American Psychiatric Association,<br />

2000).<br />

Risk factors associated with delirium are as follows:<br />

age over sixty-five, physical frailty, severe illness,<br />

multiple diseases, dementia, visual or hearing<br />

impairment, polypharmacy, sustained heavy drinking,<br />

renal impairment, and malnutrition. Precipitants<br />

are acute infections, electrolyte disturbances,<br />

drugs (especially anticholinergics), alcohol withdrawal,<br />

pain, constipation, neurological disorder,<br />

hypoxia, sleep deprivation, surgery, and environmental<br />

factors (Young & Inouye, 2007).<br />

Delirium is an acute dysfunction <strong>of</strong> arousal<br />

and/or attentional brain networks. Since arousal<br />

and attention are the bases for higher cognitive<br />

functions, most cognitive functions are affected.<br />

Neurochemically, delirium is characterized by disturbances<br />

in acetylcholine, dopamine, norepinephrine,<br />

glutamate, gamma aminobutyric acid,<br />

and serotonin systems. Cytokines and blood-brain<br />

barrier abnormalities may also play a role (Alagiakrishnan<br />

& Wiens, 2004; Van Der Mast, 1998).<br />

Treatments for delirium target the underlying<br />

cause(s), as well as the associated behavioral problems<br />

and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Modifiable<br />

risk factors or precipitants should be addressed<br />

(e.g., by treating the underlying medical condition,<br />

1

DELIRIUM TREMENS (DTS)<br />

withdrawing <strong>of</strong> possible <strong>of</strong>fending medications,<br />

correcting sensory deficits by using hearing aids<br />

and eyeglasses). <strong>Behavior</strong>s that put an individual<br />

at risk should be managed by changing the environment<br />

(e.g., providing access to familiar people<br />

and objects, protecting the individual on a locked<br />

treatment unit when there is a risk <strong>of</strong> wandering)<br />

and through behavioral interventions (e.g., reorientation,<br />

de-escalation techniques), possibly in combination<br />

with medications. Neuropsychiatric symptoms<br />

(e.g., perceptual disturbances, agitation, aggression)<br />

are managed with antipsychotics, mood stabilizers,<br />

or antiepileptics. Benzodiazepines may be useful in<br />

treating withdrawal from alcohol.<br />

See also Complications.<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

Alagiakrishnan, K., & Wiens, C. A. (2004). An approach to<br />

drug induced delirium in the elderly. Postgraduate<br />

Medical Journal, 80, 388–393.<br />

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and<br />

Statistical Manual <strong>of</strong> Mental Disorders (4th rev. ed.).<br />

Washington, DC: Author.<br />

Folstein, M. F., Bassett, S. S., Romanowsk, A. J., et al.<br />

(1993). The epidemiology <strong>of</strong> delirium in the community:<br />

The Eastern Baltimore Mental Health Survey.<br />

International Psychogeriatrics, 3, 169–179.<br />

Van Der Mast, R. C. (1998). Pathophysiology <strong>of</strong> delirium.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 11(3),<br />

138–45.<br />

Young, J., & Inouye, S. (2007). Delirium in older people.<br />

British Medical Journal, 334, 842–846.<br />

n<br />

KALOYAN TANEV<br />

DELIRIUM TREMENS (DTS). Delirium<br />

tremens (DTs) refers to the most severe form<br />

<strong>of</strong> the alcohol withdrawal syndrome, occurring<br />

with the abrupt cessation <strong>of</strong>, or reduction in, alcohol<br />

consumption in an individual who has been a<br />

heavy drinker for many years. It is associated with a<br />

significant mortality rate <strong>of</strong> an estimated 1 to 5<br />

percent, which is likely higher (perhaps up to 15<br />

percent) if untreated.<br />

DTs usually begin at seventy-two to ninety-six<br />

hours after the cessation <strong>of</strong> drinking and usually<br />

last two to three days but can occasionally last<br />

considerably longer. Early treatment <strong>of</strong> withdrawal<br />

symptoms is thought to prevent the risk <strong>of</strong> developing<br />

DTs and its related mortality. Risk factors for<br />

DTs include infection, a history <strong>of</strong> epileptic seizures,<br />

tachycardia (rapid heart rate) upon admission<br />

to hospital, withdrawal symptoms with a blood<br />

alcohol concentration 1 g/L, and a prior history<br />

<strong>of</strong> DTs. Concurrent medical conditions such as<br />

infection, trauma, and liver failure may increase<br />

the mortality <strong>of</strong> DTs.<br />

Symptoms <strong>of</strong> DTs include those typically seen<br />

in delirium, including disorientation, confusion,<br />

fluctuating levels <strong>of</strong> consciousness and attention,<br />

vivid hallucinations, delusions, agitation, and also<br />

include those found in alcohol withdrawal; fever,<br />

elevated blood pressure, rapid pulse, sweating, and<br />

tremor. Delirium is the hallmark and defining feature<br />

<strong>of</strong> DTs and differentiates the syndrome from<br />

uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal. The delirium<br />

may at times be preceded by a withdrawal seizure,<br />

although a seizure neither defines nor is its presence<br />

required to diagnose DTs, and not all patients<br />

that experience withdrawal seizures develop DTs.<br />

The treatment <strong>of</strong> DTs necessitates close monitoring<br />

in the hospital setting.<br />

For patients in alcohol withdrawal but without<br />

DTs, as the severity <strong>of</strong> withdrawal increases, patients<br />

may experience transient mild hallucinations that<br />

are auditory, visual, or tactile in nature. Loss <strong>of</strong><br />

insight into hallucinations or development <strong>of</strong> more<br />

severe and persistent hallucinations may suggest<br />

that the syndrome has progressed or is progressing<br />

to DTs. Delirium tremens is differentiated from the<br />

syndromes <strong>of</strong> alcoholic hallucinosis and chronic alcoholic<br />

hallucinosis, which are terms used inconsistently<br />

in the literature to refer to the transient<br />

hallucinosis experienced during alcohol withdrawal<br />

and/or the subsequent development <strong>of</strong> a state <strong>of</strong><br />

psychosis accompanied by hallucinations and/or<br />

delusions (particularly persecutory) that persists<br />

beyond the period <strong>of</strong> detoxification. There is controversy<br />

as to whether chronic alcoholic hallucinosis<br />

syndrome exists.<br />

See also Delirium; Withdrawal.<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

Debellis, R., Smith, B. S., Choi, S., & Malloy, M. (2005).<br />

Management <strong>of</strong> delirium tremens. Journal <strong>of</strong> Intensive<br />

Care Medicine, 20 (3), 164–173.<br />

2 ENCYCLOPEDIA OF DRUGS, ALCOHOL & ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR, 3RD EDITION

De Millas, W., & Haasen, C. (2007). Treatment <strong>of</strong> alcohol<br />

hallucinosis with risperidone. American Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Addictions, 16 (3), 249–250.<br />

Graham, A. W., Schultz, T. K., Mayo-Smith, M., & Ries, R.<br />

K. (Eds.). (2003). Principles <strong>of</strong> addiction medicine,<br />

third edition. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society <strong>of</strong><br />

Addiction Medicine.<br />

MYROSLAVA ROMACH<br />

KAREN PARKER<br />

REVISED BY ALBERT J. ARIAS (2009)<br />

DENMARK. See Nordic Countries (Denmark,<br />

Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden).<br />

n<br />

DEPRESSION. The term depression refers to<br />

both a mood and a group <strong>of</strong> psychiatric disorders.<br />

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual <strong>of</strong> Mental<br />

Disorders (DSM-IV-TR, 2000) depressed mood<br />

occurs as part <strong>of</strong> major depressive disorder (MDD),<br />

dysthymic disorder (chronic, less severe depression),<br />

and schizoaffective disorder (psychosis cooccurring<br />

with depressed or manic mood), and<br />

can also occur in bipolar disorder (periods <strong>of</strong> mania<br />

that can alternate with periods <strong>of</strong> depression) and<br />

during intoxication or withdrawal from certain<br />

substances.<br />

Many people experience brief periods <strong>of</strong><br />

depressed mood that are <strong>of</strong>ten responses to stressful<br />

life events or negative experiences. However,<br />

when depression-related symptoms cluster, persist,<br />

and ultimately cause impairment in functioning,<br />

the person is considered to be experiencing a<br />

depressive syndrome. The DSM-IV classifies this<br />

syndrome as a major depressive episode and requires<br />

the following criteria: a period <strong>of</strong> low mood (or<br />

loss <strong>of</strong> interest or pleasure in usual activities) lasting<br />

at least two weeks; four or more out <strong>of</strong> eight additional<br />

symptoms (significant change in weight or<br />

appetite, poor or increased sleep nearly every day,<br />

psychomotor agitation or retardation that is noticeable<br />

to others nearly every day, fatigue or low<br />

energy nearly every day, feelings <strong>of</strong> worthlessness<br />

or inappropriate guilt nearly every day, difficulty<br />

concentrating or making decisions nearly every<br />

day, and recurring thoughts <strong>of</strong> death, suicide, or<br />

DEPRESSION<br />

suicidal attempt); and functional impairment or<br />

clinically significant distress.<br />

If the symptoms <strong>of</strong> depression are the direct<br />

physiological effects <strong>of</strong> heavy consumption <strong>of</strong> alcohol<br />

or another psychoactive substance and are<br />

greater than the expected effects <strong>of</strong> intoxication<br />

or withdrawal, the depression is considered to be<br />

substance-induced. In DSM-IV, normal bereavement<br />

is not present if inappropriate guilt, thoughts<br />

<strong>of</strong> death unrelated to the deceased person, a preoccupation<br />

with worthlessness, marked psychomotor<br />

retardation, and hallucinations that are not a<br />

phenomenon shared by others in one’s cultural<br />

group are present, signaling the presence <strong>of</strong> a major<br />

depressive episode. Major depressive disorder is<br />

also distinguished from low mood resulting from<br />

a medical condition and mood changes that are due<br />

to exposure to a toxin or chemical substance.<br />

Major Depression is one <strong>of</strong> the most common<br />

psychiatric disorders experienced by adults. One<br />

study <strong>of</strong> data drawn from the 2001–2002 National<br />

Epidemiologic Survey on <strong>Alcohol</strong> and Related<br />

Conditions indicated that approximately 13 percent<br />

<strong>of</strong> the U.S. population has experienced a major<br />

depressive episode (Hasin et al., 2005). Women<br />

have higher rates <strong>of</strong> lifetime depression than men<br />

(17.10 percent vs. 9.01 percent), Native Americans<br />

are at greater risk for depression than other ethnic<br />

groups, and individuals who are middle-aged or<br />

widowed, separated, or divorced, and those with<br />

lower income levels are at increased risk. Depression<br />

is associated with substantial impairment<br />

(Weissman et al., 1991; Kessler et al., 1994; Kessler<br />

et al., 2003), psychiatric comorbidity (Weissman et al.,<br />

1991; Kessler et al., 1994; Kessler et al., 2003; Hasin<br />

et al., 2005), poor health (Dentino et al., 1999), and<br />

mortality (Insel & Charney, 2003).<br />

The cause <strong>of</strong> depression is multi-systemic. Imaging<br />

studies have shown abnormal neurochemical<br />

activity and changes in volume in specific areas <strong>of</strong><br />

the brain <strong>of</strong> depressed people. These biological<br />

changes, combined with genetic and psychosocial<br />

factors (e.g., life events, learned behaviors, and cognitions)<br />

all interact to varying degrees. Depression is<br />

a highly recurrent but treatable illness. Effective<br />

treatment options are available (e.g., psychotherapy,<br />

pharmacotherapy, psychoeducation, and, generally<br />

as a last option, electroconvulsive therapy), and the<br />

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF DRUGS, ALCOHOL & ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR, 3RD EDITION 3

DESIGNER DRUGS<br />

choice <strong>of</strong> treatment depends on multiple factors<br />

such as the individual’s psychiatric history, the<br />

severity <strong>of</strong> the current episode, family and social<br />

support, general medical health, the patient’s level<br />

<strong>of</strong> motivation, and the compatibility <strong>of</strong> the treatment<br />

with the patient’s current circumstances.<br />

See also Complications: Mental Disorders; Risk Factors<br />

for Substance Use, Abuse, and Dependence: An<br />

Overview.<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and<br />

statistical manual <strong>of</strong> mental disorders (4th rev. ed.).<br />

Washington, DC: Author.<br />

Dentino, A. N., Pieper, C. F., Rao, M. K., Currie, M. S.,<br />

Harris, T., Blazer, D. G., et al. (1999). Association <strong>of</strong><br />

interleukin-6 and other biologic variables with depression<br />

in older people living in the community. Journal<br />

<strong>of</strong> the American Geriatric Society, 47, 6–11.<br />

Hasin, D., Goodwin, R., Stinson, F. S., & Grant, B. F.<br />

(2005). Epidemiology <strong>of</strong> major depressive disorder:<br />

Results from the national epidemiologic survey on<br />

alcoholism and related conditions. Archives <strong>of</strong> General<br />

Psychiatry, 62, 1097–1106.<br />

Insel, T. R., & Charney, D. S. (2003). Research on major<br />

depression: Strategies and priorities. Journal <strong>of</strong> American<br />

Medical Association, 289, 3167–3168.<br />

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Koretz,<br />

D., Merikangas, K. R., et al. (2003). National Comorbidity<br />

Survey Replication: The epidemiology <strong>of</strong> major<br />

depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity<br />

Survey Replication (NCS-R). Journal <strong>of</strong> American<br />

Medical Association, 289, 3095–3105.<br />

Kessler, R. C., McGonagle, K. A., Zhao, S., Nelson, C.,<br />

Hughes, M., Eshleman, S., et al. (1994). Lifetime and<br />

12-month prevalence <strong>of</strong> DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders<br />

in the United States: Results from the National<br />

Comorbidity Survey. Archives <strong>of</strong> General Psychiatry, 51,<br />

8–19.<br />

Weissman, M. M., Bruce, L. M., Leaf, P. J., Florio, L. P., &<br />

Holzer, C., III. (1991). Affective disorders. In L. N.<br />

Robins & D. A. Regier (Eds.), Psychiatric disorders in<br />

America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study<br />

(pp. 53–80). New York: Free Press.<br />

n<br />

SHARON SAMET<br />

DESIGNER DRUGS. ‘‘Designer drugs’’<br />

are synthetic chemical analogs <strong>of</strong> abused substances<br />

that are designed to produce pharmacological<br />

effects similar to the substances they mimic. In<br />

the pharmaceutical industry, the design <strong>of</strong> new<br />

drugs <strong>of</strong>ten utilizes principles <strong>of</strong> basic chemistry,<br />

so that the structure <strong>of</strong> a drug molecule is slightly<br />

altered in order to change its pharmacological<br />

activity. This strategy has a long and successful<br />

history in medical pharmaceutics, and many useful<br />

new drugs or modifications <strong>of</strong> older drugs have<br />

clearly resulted in improved health care for many<br />

people throughout the world. The principles <strong>of</strong><br />

structure-activity relationships have been applied<br />

to many medically approved drugs, especially in<br />

the search for a nonaddicting opioid analgesic for<br />

the treatment <strong>of</strong> pain. However, the clandestine<br />

production <strong>of</strong> ‘‘designer’’ street drugs is intended<br />

to avoid federal regulation and control. This practice<br />

can <strong>of</strong>ten result in the appearance <strong>of</strong> new and<br />

unknown substances with wide-ranging variations<br />

in purity. The quality <strong>of</strong> personnel involved in<br />

clandestine designer-drug synthesis can range from<br />

‘‘cookbook’’ amateurs to highly skilled chemists,<br />

which means that these substances have the potential<br />

to cause dangerous toxicity with serious health<br />

consequences for the unwitting drug user.<br />

A resurgence in the popularity <strong>of</strong> a relatively old<br />

drug, methamphetamine, was observed during the<br />

first decade <strong>of</strong> the twenty-first century. Although<br />

methamphetamine is manufactured in foreign or<br />

domestic ‘‘superlabs,’’ the drug is also easily made<br />

in small clandestine laboratories with relatively inexpensive<br />

over-the-counter ingredients. This practice<br />

can lead to wide variations in the purity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

methamphetamine available for illicit distribution.<br />

Methamphetamine is a highly addictive central nervous<br />

system stimulant that was developed early in the<br />

twentieth century and initially used in nasal decongestants<br />

and bronchial inhalers. Like amphetamine,<br />

methamphetamine produces increased activity and<br />

talkativeness, anorexia, and a general sense <strong>of</strong> wellbeing.<br />

However, methamphetamine differs from<br />

amphetamine in that much higher levels <strong>of</strong> methamphetamine<br />

get into the brain when comparable<br />

doses are administered, making it a more potent<br />

stimulant drug. And while methamphetamine<br />

blocks the reuptake <strong>of</strong> dopamine at low doses, in<br />

a manner similar to cocaine, it also increases the<br />

release <strong>of</strong> dopamine, leading to much higher concentrations<br />

<strong>of</strong> this neurotransmitter. Although the<br />

pleasurable effects <strong>of</strong> methamphetamine most likely<br />

result from the release <strong>of</strong> dopamine, the elevated<br />

4 ENCYCLOPEDIA OF DRUGS, ALCOHOL & ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR, 3RD EDITION

elease <strong>of</strong> this neurotransmitter also contributes to<br />

the drug’s deleterious effects on nerve terminals.<br />

Specifically, brain-imaging studies have demonstrated<br />

alterations in the activity <strong>of</strong> the dopamine<br />

system that are due to methamphetamine use.<br />

Recent studies <strong>of</strong> chronic methamphetamine users<br />

have revealed structural and functional changes in<br />

areas <strong>of</strong> the brain associated with emotion and<br />

memory, which may account for many <strong>of</strong> the emotional<br />

and cognitive problems experienced by<br />

chronic users.<br />

Addicts typically exhibit anxiety, confusion,<br />

insomnia, mood disturbances, and violent behavior,<br />

and they can also display a number <strong>of</strong> psychotic<br />

features, including paranoia, visual and auditory<br />

hallucinations, and delusions. These psychotic<br />

symptoms can last for months or years after methamphetamine<br />

use has ceased, and stress has been<br />

shown to precipitate the spontaneous recurrence <strong>of</strong><br />

methamphetamine psychoses. Methamphetamine<br />

can also produce a variety <strong>of</strong> cardiovascular effects,<br />

including rapid heart rate, irregular heartbeat, and<br />

increased blood pressure. Hyperthermia (elevated<br />

body temperature) and convulsions may occur during<br />

a methamphetamine overdose, and, if not<br />

treated immediately, this can result in death. Tolerance<br />

to methamphetamine’s pleasurable effects<br />

develops with chronic use, and abusers may take<br />

higher doses <strong>of</strong> the drug, take it more frequently,<br />

or change their method <strong>of</strong> drug intake in an effort<br />

to intensify the desired effects. Methamphetamine<br />

has also become associated with a culture <strong>of</strong> risky<br />

sexual behavior, both among men who have sex<br />

with men and heterosexual populations, because<br />

methamphetamine and related psychomotor stimulants<br />

can increase libido. Paradoxically, however,<br />

long-term methamphetamine abuse may be associated<br />

with decreased sexual functioning.<br />

Other hallucinogenic designer drugs that are<br />

amphetamine analogs—such as methylenedioxyamphetamine<br />

(MDA), methylenedioxymethamphetamine<br />

(MDMA or ‘‘Ecstasy’’) and methylenedioxyethamphetamine<br />

(MDEA or ‘‘Eve’’)—can also produce<br />

acute and chronic toxicity. Acute toxicity from these<br />

drugs is usually manifested as restlessness, agitation,<br />

sweating, high blood pressure, tachycardia, and<br />

other cardiovascular effects, all <strong>of</strong> which are suggestive<br />

<strong>of</strong> excessive central nervous system stimulation.<br />

Following chronic administration, MDA produces a<br />

DESIGNER DRUGS<br />

degeneration <strong>of</strong> serotonergic nerve terminals in rats,<br />

implying that it might induce chronic neurological<br />

damage in humans as well.<br />

Newer designer drugs <strong>of</strong> abuse that have recently<br />

emerged on the black market include amphetaminederived<br />

drugs such as para-methoxyamphetamine<br />

(PMA), para-methoxymethamphetamine (PMMA)<br />

and 4-methylthioamphetamine (4-MTA). In addition,<br />

newer designer drugs <strong>of</strong> the benzyl or phenyl<br />

piperazine type, and <strong>of</strong> the pyrrolidinophenone type,<br />

have gained popularity and notoriety as party or<br />

‘‘rave’’ drugs. These include N-benzylpiperazine<br />

(BZP); 1-(3, 4-methylenedioxybenzyl)piperazine<br />

(MDBP); 1-(3-chlorophenyl)piperazine (mCPP);<br />

1-(3-trifluoromethylphenyl)piperazine (TFMPP);<br />

1-(4-methoxyphenyl)piperazine (MeOPP); alphapyrrolidinopropiophenone<br />

(PPP); 4’-methoxyalpha-pyrrolidinopropiophenone<br />

(MOPPP); 3’,<br />

4’-methylenedioxy-alpha-pyrrolidinopropiophenone<br />

(MDPPP); 4’-methyl-alpha-pyrrolidinopropiophenone<br />

(MPPP); and 4’-methyl-alpha-pyrrolidinoexanophenone<br />

(MPHP). These drugs produce<br />

feelings <strong>of</strong> euphoria and energy and a desire to<br />

socialize. While ‘‘word on the street’’ suggests that<br />

these designer drugs are safe, studies in rats and<br />

primates have suggested that they present risks to<br />

humans. In fact, a variety <strong>of</strong> adverse effects have<br />

been associated with the use <strong>of</strong> this class <strong>of</strong> drugs in<br />

humans, including a life-threatening serotonin syndrome<br />

(due to an excess <strong>of</strong> this neurotransmitter),<br />

and toxic effects on the liver and brain that result in<br />

behavioral changes.<br />

An opioid that has resulted in serious health<br />

hazards on the street is fentanyl (Sublimaze), a<br />

potent and extremely fast-acting narcotic analgesic<br />

with a high abuse liability. This drug has also served<br />

as a template for many look-alike drugs in the<br />

clandestine chemical laboratory. Very slight modifications<br />

in the chemical structure <strong>of</strong> fentanyl can<br />

result in analogs such as para-fluoro-, 3-methyl-, or<br />

alpha-methyl-fentanyl, with relative potencies that<br />

are 100, 900, and 1,100 times that <strong>of</strong> morphine,<br />

respectively. Unfortunately, a steady increase in<br />

deaths from drug overdoses associated with fentanyl-like<br />

designer drugs has been reported.<br />

Designer drugs already on the street, such as<br />

methamphetamine and related stimulants, can produce<br />

significant brain damage following long-term<br />

use, and analogs <strong>of</strong> the opioid fentanyl can produce<br />

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF DRUGS, ALCOHOL & ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR, 3RD EDITION 5

DEXTROAMPHETAMINE<br />

fatal overdoses. Taken to the extreme, the widespread<br />

illicit manufacture and use <strong>of</strong> designer drugs<br />

with unknown toxicity could result in millions <strong>of</strong><br />

people ingesting the drug before the toxic effects<br />

are known, potentially producing an epidemic <strong>of</strong><br />

neurodegenerative disorders and fatalities.<br />

See also Controlled Substances Act <strong>of</strong> 1970; MDMA;<br />

MPTP.<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

Barnett, G., & Rapaka, R. S. (1989). Designer drugs: An<br />

overview. In K. K. Redda, C. A. Walker, & G. Barnett<br />

(Eds.), Cocaine, marijuana, designer drugs: Chemistry,<br />

pharmacology, and behavior (pp. 163–174). Boca<br />

Raton, FL: CRC Press.<br />

Beebe, D. K., & Walley, E. (1991). Substance abuse: The<br />

designer drugs. American Family Physician, 43(5),<br />

1689–1698.<br />

Christophersen, A. S. (2000). Amphetamine designer<br />

drugs: An overview and epidemiology. Toxicology Letters,<br />

112–113, 127–131.<br />

de Boer, D., Bosman, I. J., Hidvégi, E., Manzoni, C.,<br />

Benkö, A. A., dos Reys, L. J., et al. (2001). Piperazine-like<br />

compounds: A new group <strong>of</strong> designer drugs<strong>of</strong>-abuse<br />

on the European market. Forensic Science<br />

International, 121(1–2), 47–56.<br />

Klein, M., & Kramer, F. (2004). Rave drugs: Pharmacological<br />

considerations. AANA Journal, 72(1), 61–67.<br />

Maurer, H. H., Kraemer, T., Springer, D., & Staack, R. F.<br />

(2004). Chemistry, pharmacology, toxicology, and<br />

hepatic metabolism <strong>of</strong> designer drugs <strong>of</strong> the amphetamine<br />

(ecstasy), piperazine, and pyrrolidinophenone<br />

types: A synopsis. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring,<br />

26(2), 127–131.<br />

Nichols, D. E. (1989). Substituted amphetamine controlled<br />

substance analogues. In K. K. Redda, C. A. Walker &<br />

G. Barnett (Eds.), Cocaine, marijuana, designer drugs:<br />

Chemistry, pharmacology, and behavior (pp. 175–185).<br />

Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.<br />

Soine, W. H. (1986). Clandestine drug synthesis. Medicinal<br />

Research Reviews, 6(1), 41–47.<br />

Staack, R. F., & Maurer, H. H. (2005). Metabolism <strong>of</strong><br />

designer drugs <strong>of</strong> abuse. Currents in Drug Metabolism,<br />

6(3), 259–274.<br />

Trevor, A., Castagnoli, N., Jr., & Singer, T. P. (1989).<br />

Pharmacology and toxicology <strong>of</strong> MPTP: A neurotoxic<br />

by-product <strong>of</strong> illicit designer drug chemistry. In K. K.<br />

Redda, C. A. Walker & G. Barnett (Eds.), Cocaine,<br />

marijuana, designer drugs: Chemistry, pharmacology,<br />

and behavior (pp. 187–200). Boca Raton, FL: CRC<br />

Press.<br />

Ziporyn, T. (1986). A growing industry and menace:<br />

Makeshift laboratory’s designer drugs. Journal <strong>of</strong> the<br />

American Medical Association, 256(22), 3061–3063.<br />

n<br />

NICHOLAS E. GOEDERS<br />

DEXTROAMPHETAMINE. This is the<br />

d-isomer <strong>of</strong> amphetamine. It is classified as a psychomotor<br />

stimulant drug and is three to four times<br />

as potent as the l-isomer in eliciting central nervous<br />

system (CNS) excitatory effects. It is also more<br />

potent than the l-isomer in its anorectic (appetite<br />

suppressant) activity, but slightly less potent in its<br />

cardiovascular actions. It is prescribed in the treatment<br />

<strong>of</strong> narcolepsy and obesity, although care must<br />

be taken in such prescribing because <strong>of</strong> the substantial<br />

abuse liability.<br />

High-dose chronic use <strong>of</strong> dextroamphetamine<br />

can lead to the development <strong>of</strong> a toxic psychosis as<br />

well as to other physiological and behavioral problems.<br />

This toxicity became a problem in the United<br />

States in the 1960s, when substantial amounts <strong>of</strong><br />

the drug were being taken for nonmedical reasons.<br />

Although still abused by some, dextroamphetamine<br />

is no longer the stimulant <strong>of</strong> choice for most<br />

psychomotor stimulant abusers.<br />

See also Amphetamine Epidemics, International; Coca/<br />

Cocaine, International.<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

de Wit, H., et al (2002). Acute administration <strong>of</strong> d-amphetamine<br />

decreases impulsivity in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology,<br />

27, 813–825.<br />

Schmetzer, A. D. (2004). The psychostimulants. Annals <strong>of</strong><br />

the American Psychotherapy Association, 7, 31–32.<br />

MARIAN W. FISCHMAN<br />

n<br />

DIAGNOSIS OF SUBSTANCE USE<br />

DISORDERS: DIAGNOSTIC CRI-<br />

TERIA. Diagnosis is the process <strong>of</strong> identifying<br />

and labeling specific disease conditions. The signs<br />

and symptoms used to classify a sick person as<br />

having a disease are called diagnostic criteria. Diagnostic<br />

criteria and classification systems are useful<br />

for making clinical decisions, estimating disease<br />

6 ENCYCLOPEDIA OF DRUGS, ALCOHOL & ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR, 3RD EDITION

prevalence, understanding the causes <strong>of</strong> disease,<br />

and facilitating scientific communication.<br />

Diagnostic classification provides the treating<br />

clinician with a basis for retrieving information about<br />

a patient’s probable symptoms, the likely course <strong>of</strong> an<br />

illness, and the biological or psychological processes<br />

that underlie the disorder. For example, the Diagnostic<br />

and Statistical Manual (DSM) <strong>of</strong> the American Psychiatric<br />

Association is a classification <strong>of</strong> mental disorders<br />

that provides the clinician with a systematic<br />

description <strong>of</strong> each disorder in terms <strong>of</strong> essential features,<br />

age <strong>of</strong> onset, probable course, predisposing factors,<br />

associated features, and differential diagnosis.<br />

Mental health pr<strong>of</strong>essionals can use this system to<br />

diagnose substance use disorders in terms <strong>of</strong> the following<br />

categories: acute intoxication, abuse, dependence,<br />

withdrawal, delirium, and other disorders. In<br />

contrast to screening, diagnosis typically involves a<br />

broader evaluation <strong>of</strong> signs, symptoms, and laboratory<br />

data as these relate to the patient’s illness. The purpose<br />

<strong>of</strong> diagnosis is to provide the clinician with a logical<br />

basis for planning treatment and estimating prognosis.<br />

Another purpose <strong>of</strong> classification is the collection<br />

<strong>of</strong> statistical information on a national and<br />

international scale. The primary purpose <strong>of</strong> the<br />

World Health Organization’s International Classification<br />

<strong>of</strong> Diseases (ICD), for example, is the enumeration<br />

<strong>of</strong> morbidity and mortality data for public<br />

health planning. In addition, a good classification<br />

will facilitate communication among scientists and<br />

provide the basic concepts needed for theory development.<br />

Both the DSM and ICD have also been<br />

used extensively to classify persons for scientific<br />

research. Classification thus provides a common<br />

frame <strong>of</strong> reference in communicating scientific<br />

findings.<br />

Diagnosis may also serve a variety <strong>of</strong> administrative<br />

purposes. When a patient is suspected <strong>of</strong><br />

having a substance use disorder, diagnostic procedures<br />

are needed to exclude ‘‘false positives’’ (i.e.,<br />

people who appear to have the disorder but who<br />

really do not) and borderline cases. Insurance reimbursement<br />

for medical treatment increasingly<br />

demands that a formal diagnosis be confirmed<br />

according to standard procedures or criteria. The<br />

need for uniform reporting <strong>of</strong> statistical data, as<br />

well as the generation <strong>of</strong> prevalence estimates for<br />

epidemiological research, <strong>of</strong>ten requires a diagnostic<br />

classification <strong>of</strong> the patient.<br />

DIAGNOSIS OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS: DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA<br />

CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS<br />

<strong>Alcohol</strong>ism and drug addiction have been variously<br />

defined as medical diseases, mental disorders, social<br />

problems, and behavioral conditions. In some<br />

cases, they are considered the symptom <strong>of</strong> an<br />

underlying mental disorder (Babor, 1992). Some<br />

<strong>of</strong> these definitions permit the classification <strong>of</strong> alcoholism<br />

and drug dependence within standard<br />

nomenclatures such as the DSM and ICD. The<br />

most recent revisions <strong>of</strong> both <strong>of</strong> these diagnostic<br />

systems—DSM-IV (1994) and ICD-10 (1992)—<br />

have resulted in a high degree <strong>of</strong> compatibility<br />

between the classification criteria used in the<br />

United States and those used internationally. Both<br />

systems now diagnose dependence according to the<br />

elements first proposed by Edwards and Gross<br />

(1976). They also include a residual category<br />

(harmful alcohol use [ICD-10]; alcohol abuse<br />

[DSM-IV]) that allows classification <strong>of</strong> psychological,<br />

social, and medical consequences directly<br />

related to substance use.<br />

HISTORY TAKING<br />

Obtaining accurate information from patients with<br />

alcohol and drug problems is <strong>of</strong>ten difficult<br />

because <strong>of</strong> the stigma associated with substance<br />

abuse and the fear <strong>of</strong> legal consequences. At times,<br />

these individuals want help for the medical complications<br />

<strong>of</strong> substance use (such as injuries or depression)<br />

but are ambivalent about giving up alcohol or<br />

drug use entirely. It is <strong>of</strong>ten the case that these<br />

patients are evasive and attempt to conceal or minimize<br />

the extent <strong>of</strong> their alcohol or drug use.<br />

Acquiring accurate information about the presence,<br />

severity, duration, and effects <strong>of</strong> alcohol and drug<br />

use therefore requires a considerable amount <strong>of</strong><br />

clinical skill.<br />

The medical model for history taking is the<br />

most widely used approach to diagnostic evaluation.<br />

This model consists <strong>of</strong> identifying the chief<br />

complaint, evaluating the present illness, reviewing<br />

past history, conducting a review <strong>of</strong> biological systems<br />

(e.g., gastrointestinal, cardiovascular), asking<br />

about family history <strong>of</strong> similar disorders, and discussing<br />

the patient’s psychological and social functioning.<br />

A history <strong>of</strong> the present illness begins with<br />

questions on the use <strong>of</strong> alcohol, drugs, and<br />

tobacco. The questions should cover prescription<br />

drugs as well as illicit drugs, with additional elaboration<br />

<strong>of</strong> the kinds <strong>of</strong> drugs, the amount used, and<br />

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF DRUGS, ALCOHOL & ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR, 3RD EDITION 7

DIAGNOSIS OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS: DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA<br />

the mode <strong>of</strong> administration (e.g., smoking, injection).<br />

Questions about alcohol use should refer<br />

specifically to the amount and frequency <strong>of</strong> using<br />

the major beverage types (wine, spirits, and beer).<br />

A thorough physical examination is important<br />

because each substance has specific pathological<br />

effects on certain organs and body systems. For<br />

example, alcohol commonly affects the liver, stomach,<br />

cardiovascular system, and nervous system,<br />

while drugs <strong>of</strong>ten produce abnormalities in ‘‘vital<br />

signs’’ such as temperature, pulse, and blood<br />

pressure.<br />

A mental status examination frequently gives<br />

evidence <strong>of</strong> substance use disorders, which can be<br />

signaled by poor personal hygiene, inappropriate<br />

affect (e.g., sad, euphoric, irritable, anxious), illogical<br />

or delusional thought processes, and memory<br />

problems. The physical examination can be supplemented<br />

by laboratory tests, which sometimes aid in<br />

early diagnosis before severe or irreversible damage<br />

has taken place. Laboratory tests are useful in two<br />

ways: (1) alcohol and drugs can be measured<br />

directly in blood, urine, or exhaled air; (2) biochemical<br />

and psychological functions known to be<br />

affected by substance use can be assessed. Many<br />

drugs can be detected in the urine for 12 to 48<br />

hours after their consumption. An estimate <strong>of</strong><br />

blood alcohol concentration (BAC) can be made<br />

directly by blood test or indirectly by means <strong>of</strong> a<br />

breath or saliva test. Elevations <strong>of</strong> the liver enzyme<br />

gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTP) or the<br />

protein carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT)<br />

are sensitive indicators <strong>of</strong> chronic and heavy alcohol<br />

intake. However, while these tests can detect<br />

recent use <strong>of</strong> a wide variety <strong>of</strong> psychoactive substances<br />

(e.g., opioids, cannabis, stimulants, barbiturates),<br />

they are not able to detect alcohol or<br />

drug dependence.<br />

In addition to the physical examination and laboratory<br />

tests, a variety <strong>of</strong> diagnostic interview procedures<br />

have been developed to provide objective,<br />

empirically based, reliable diagnoses <strong>of</strong> substance use<br />

disorders in various clinical populations. One type,<br />

exemplified by the Diagnostic Interview Schedule<br />

(DIS; see Robins et al., 1981) and the Composite<br />

International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; see Robins<br />

et al., 1988), is highly structured and requires a<br />

minimum <strong>of</strong> clinical judgment by the interviewer.<br />

These interviews provide information not only about<br />

substance use disorders, but also about physical conditions<br />

and psychiatric disorders that are commonly<br />

associated with substance abuse. Because <strong>of</strong> its standardized<br />

questioning procedures, the CIDI has been<br />

used by the World Health Organization to estimate<br />

the prevalence <strong>of</strong> mental disorders, including substance<br />

use disorders, in the general populations <strong>of</strong><br />

countries throughout the world (Haro et al., 2006).<br />

In the United States, the <strong>Alcohol</strong> Use Disorder<br />

and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV<br />

(AUDADIS-IV) has been used extensively in population<br />

surveys, including the National Epidemiologic<br />

Survey on <strong>Alcohol</strong> and Related Conditions (Grant et<br />

al., 2003). It covers alcohol consumption, tobacco<br />

use, family history <strong>of</strong> depression, and selected DSM-<br />

IV Axis I and II psychiatric disorders.<br />

A second type <strong>of</strong> diagnostic interview is exemplified<br />

by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV<br />

(SCID), which is designed for use by mental health<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionals (Spitzer et al., 1992; First et al., 2002).<br />

The SCID assesses the most commonly occurring<br />

psychiatric disorders described in DSM-IV, including<br />

mood disorders, schizophrenia, and substance use<br />

disorders. A similar clinical interview designed for<br />

international use is the Schedules for Clinical Assessment<br />

in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN; see Wing et al.,<br />

1990). The SCID and SCAN interviews allow the<br />

experienced clinician to tailor questions to fit the<br />

patient’s understanding, to ask additional questions<br />

that clarify ambiguities, to challenge inconsistencies,<br />

and to make clinical judgments about the seriousness<br />

<strong>of</strong> symptoms. Both are modeled on the standard<br />

medical history practiced by many mental health<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionals. Questions about the chief complaint,<br />

past episodes <strong>of</strong> psychiatric disturbance, treatment<br />

history, and current functioning all contribute to a<br />

thorough and orderly psychiatric history that is<br />

extremely useful for diagnosing substance use disorders.<br />

The Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance<br />

and Mental Disorders (PRISM; Hasin et al.,<br />

2006) is another semistructured diagnostic interview.<br />

It is designed to deal with the problems <strong>of</strong><br />

psychiatric diagnosis when subjects or patients drink<br />

heavily or use drugs. The PRISM is used for making a<br />

number <strong>of</strong> DSM-IV Axis I and Axis II diagnoses,<br />

including alcohol and drug use disorders, in a way<br />

that allows differentiation <strong>of</strong> psychiatric disorders<br />

from substance-induced disorders and from the<br />

expected effects <strong>of</strong> intoxication and withdrawal.<br />

8 ENCYCLOPEDIA OF DRUGS, ALCOHOL & ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR, 3RD EDITION

In recent years, there has been interest in developing<br />

better methods to obtain accurate information<br />

from patients with substance use disorders, both for<br />

diagnostic purposes and for the measurement <strong>of</strong><br />

treatment outcomes. It has been assumed that information<br />

obtained from alcohol and drug users cannot<br />

be trusted, because they <strong>of</strong>ten unconsciously deny<br />

that they have a problem or deliberately lie about<br />

their substance use to avoid the embarrassment <strong>of</strong><br />

being labeled as an alcoholic or a drug addict.<br />

Another factor is clinical suspicion that individuals<br />

with substance use disorders <strong>of</strong>ten are not capable <strong>of</strong><br />

reporting their symptoms accurately, due to the cognitive<br />

effects <strong>of</strong> chronic substance use.<br />

With advances in the technology <strong>of</strong> psychiatric<br />

interviewing, questionnaire design, and psychological<br />

measurement, it is now possible to obtain valid<br />

measurement at the symptom level and to improve<br />

classification accuracy at the syndrome level (Haro<br />

et al., 2006). According to one systematic review <strong>of</strong><br />

methodological studies, self-report measures using<br />

questionnaires and interviews tend to be valid and<br />

reliable in the aggregate under most circumstances<br />

(Del Boca & Noll, 2000). Nevertheless, patients<br />

may bias their responses in a socially desirable<br />

direction when they do not understand the purpose<br />

<strong>of</strong> the questions, feel threatened by the possible<br />

outcome <strong>of</strong> the diagnostic evaluation (e.g.,<br />

being labeled as having a psychiatric disorder), have<br />

cognitive disabilities that affect memory and recall,<br />

or have personality characteristics (e.g., psychopathy)<br />

that increase the chances <strong>of</strong> deliberate lying.<br />

DIAGNOSIS OF ABUSE AND HARMFUL USE<br />

A major diagnostic category that has received<br />

increasing attention in research and clinical practice<br />

is substance abuse—in contrast to dependence.<br />

This category permits the classification <strong>of</strong> maladaptive<br />

patterns <strong>of</strong> alcohol or drug use that do not<br />

meet criteria for dependence. The diagnosis <strong>of</strong><br />

abuse is designed primarily for persons who have<br />

recently begun to experience alcohol or drug problems,<br />

as well as for chronic users whose substancerelated<br />

consequences develop in the absence <strong>of</strong><br />

marked dependence symptoms. Examples <strong>of</strong> situations<br />

in which this category would be appropriate<br />

include: (1) a pregnant woman who keeps drinking<br />

alcohol even though her physician has told her that<br />

DIAGNOSIS OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS: DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA<br />

it could cause fetal damage; (2) a college student<br />

whose weekend binges result in missed classes,<br />

poor grades, and alcohol-related traffic accidents;<br />

(3) a middle-aged beer drinker regularly consuming<br />

a six-pack each day who develops high blood<br />

pressure and fatty liver in the absence <strong>of</strong> alcoholdependence<br />

symptoms; and (4) an occasional marijuana<br />

smoker who has an accidental injury while<br />

intoxicated.<br />

In the fourth revision <strong>of</strong> the Diagnostic and<br />

Statistical Manual (American Psychiatric Association,<br />

1994), substance abuse is defined as a maladaptive<br />

pattern <strong>of</strong> alcohol or drug use leading to<br />

clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested<br />

by one or more <strong>of</strong> the symptoms listed in<br />

Table 1. (For comparative purposes, the table also<br />

lists the criteria for harmful use in ICD-10.) To<br />

assure that the diagnosis is based on clinically<br />

meaningful symptoms, rather than the results <strong>of</strong><br />

an occasional excess, the duration criterion specifies<br />

how long the symptoms must be present to qualify<br />

for a diagnosis.<br />

In ICD-10, the term harmful use refers to a<br />

pattern <strong>of</strong> using one or more psychoactive substances<br />

that causes damage to health. The damage may<br />

be: (1) physical (physiological)—such as pancreatitis<br />

from alcohol or hepatitis from needle-injected<br />

drugs; or (2) mental (psychological)—such as<br />

depression related to heavy drinking or drug use.<br />

Adverse social consequences <strong>of</strong>ten accompany substance<br />

use, but they are not in themselves sufficient<br />

to result in a diagnosis <strong>of</strong> harmful use. The key<br />

issue in the definition <strong>of</strong> this term is the distinction<br />

between perceptions <strong>of</strong> adverse effects (e.g., wife<br />

complaining about husband’s drinking) and actual<br />

health consequences (e.g., trauma due to accidents<br />

during drug intoxication). Since the purpose <strong>of</strong><br />

ICD is to classify diseases, injuries, and causes <strong>of</strong><br />

death, harmful use is defined as a pattern <strong>of</strong> use<br />

already causing damage to health.<br />

Harmful patterns <strong>of</strong> use are <strong>of</strong>ten criticized by<br />

others, and they are sometimes legally prohibited<br />

by governments. However, the fact that alcohol or<br />

drug intoxication is disapproved by another person<br />

or by the user’s culture is not in itself evidence <strong>of</strong><br />

harmful use, unless socially negative consequences<br />

have actually occurred at dosage levels that also<br />

result in psychological and physical consequences.<br />

This is the major difference that distinguishes<br />

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF DRUGS, ALCOHOL & ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR, 3RD EDITION 9

DIAGNOSIS OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS: DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA<br />

Symptom Criteria<br />

ICD-10 Criteria for Harmful Use DSM-IV Criteria for Abuse<br />

Clear evidence that alcohol or drug use is responsible for<br />

causing actual psychological or physical harm to the<br />

user<br />

Duration Criterion The pattern <strong>of</strong> use has persisted for at least 1 month or<br />

has occurred repeatedly over the previous 12 months<br />

One or more symptoms has occurred during the same 12-month period<br />

ICD-10’s harmful use from DSM-IV ’s substance<br />

abuse—the latter category includes social consequences<br />

in the diagnosis <strong>of</strong> abuse.<br />

THE DEPENDENCE SYNDROME CONCEPT<br />

The diagnosis <strong>of</strong> substance use disorders in ICD-10<br />

and DSM-IV is based on the concept <strong>of</strong> a ‘‘dependence<br />

syndrome,’’ which is distinguished from disabilities<br />

caused by substance use (Edwards, Arif, &<br />

Hodgson, 1981). An important diagnostic issue is<br />

the extent to which dependence is sufficiently distinct<br />

from abuse or harmful use to be considered a<br />

separate condition. In DSM-IV, substance abuse is a<br />

residual category that allows the clinician to classify<br />

clinically meaningful aspects <strong>of</strong> a patient’s behavior<br />

when that behavior is not clearly associated with a<br />

dependence syndrome. In ICD-10, harmful substance<br />

use implies identifiable substance-induced<br />

medical or psychiatric consequences that occur in<br />

the absence <strong>of</strong> a dependence syndrome. In both<br />

classification systems, dependence is conceived as<br />

an underlying condition that has much greater<br />

clinical significance because <strong>of</strong> its implications for<br />

understanding etiology, predicting course, and<br />

planning treatment.<br />

The dependence syndrome is seen as an interrelated<br />

cluster <strong>of</strong> cognitive, behavioral, and physiological<br />

symptoms. Table 2 summarizes the criteria used<br />

to diagnose dependence in ICD-10 and DSM-IV. A<br />

diagnosis <strong>of</strong> dependence in all systems is made if<br />

three or more <strong>of</strong> the criteria have been experienced<br />

at some time in the previous twelve months.<br />

The dependence syndrome may be present<br />

for a specific substance (e.g., tobacco, alcohol,<br />

A maladaptive pattern <strong>of</strong> alcohol or drug use indicated by at least one <strong>of</strong><br />

the following: (1) failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school,<br />

or home (e.g., neglect <strong>of</strong> children or household); (2) use in situations in<br />

which it is physically hazardous (e.g., driving an automobile);<br />

(3) recurrent substance-related legal problems (e.g., arrests for<br />

substance-related disorderly conduct); (4) continued substance use<br />

despite having recurrent social or interpersonal problems<br />

Table 1. Diagnostic Criteria for Harmful Use (IDC-10) and Substance Abuse (DSM-III-R, DSM-IV). ILLUSTRATION BY GGS INFORMATION<br />

SERVICES. GALE, CENGAGE LEARNING<br />

or diazepam), for a class <strong>of</strong> substances (e.g., opioid<br />

drugs), or for a wider range <strong>of</strong> various substances.<br />

A diagnosis <strong>of</strong> dependence does not necessarily<br />

imply the presence <strong>of</strong> physical, psychological, or<br />

social consequences, although some form <strong>of</strong> harm<br />

is usually present. There are some differences among<br />

these classification systems, but the criteria are very<br />

similar, making it unlikely that a patient diagnosed<br />

in one system would be diagnosed differently in<br />

the other.<br />

The syndrome concept implicit in the diagnosis<br />

<strong>of</strong> alcohol and drug dependence in ICD and DSM is<br />

a way <strong>of</strong> describing the nature and severity <strong>of</strong> addiction<br />

(Babor, 1992). Table 2 describes four dependence<br />

syndrome elements (salience, impaired control,<br />

tolerance, withdrawal, and withdrawal relief) in relation<br />

to the criteria for DSM-IV, andICD-10. The<br />

same elements apply to the diagnosis <strong>of</strong> dependence<br />

on all psychoactive substances, including alcohol,<br />

marijuana, opioids, cocaine, sedatives, phencyclidine,<br />

other hallucinogens, and tobacco. The elements represent<br />

biological, psychological (cognitive), and behavioral<br />

processes. This helps to explain the linkages and<br />

interrelationships that account for the coherence <strong>of</strong><br />

signs and symptoms. The co-occurrence <strong>of</strong> signs and<br />

symptoms is the essential feature <strong>of</strong> a syndrome. If<br />

three or more criteria occur repeatedly during the<br />

same period, it is likely that dependence is responsible<br />

for the amount, frequency, and pattern <strong>of</strong> the person’s<br />

substance use.<br />

Salience. Salience means that drinking or drug use<br />

is given a higher priority than other activities in spite<br />

<strong>of</strong> its negative consequences. This is reflected in the<br />

emergence <strong>of</strong> substance use as the preferred activity<br />

from a set <strong>of</strong> available alternative activities. In addition,<br />

the individual does not respond well to the<br />

10 ENCYCLOPEDIA OF DRUGS, ALCOHOL & ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR, 3RD EDITION

Dependence element<br />

Salience<br />

Impaired control<br />

Tolerance<br />

Withdrawal and<br />

withdrawal relief<br />

Diagnostic level<br />

Cognitive, behavioral<br />

<strong>Behavior</strong>al<br />

<strong>Behavior</strong>al, cognitive<br />

<strong>Behavior</strong>al<br />

Biological, behavioral<br />

<strong>Behavior</strong>al, biological,<br />

cognitive<br />

normal processes <strong>of</strong> social control. For example,<br />

when drinking to intoxication goes against the tacit<br />

social rules governing the time, place, or amount<br />

typically expected by the user’s family or friends, this<br />

may indicate increased salience.<br />

One indication <strong>of</strong> salience is the amount <strong>of</strong><br />

time or effort devoted to obtaining, using, or<br />

recovering from substance use. For example, people<br />

who spend a great deal <strong>of</strong> time at parties, bars,<br />

or business lunches give evidence <strong>of</strong> the increased<br />

salience <strong>of</strong> drinking over nondrinking activities.<br />

Chronic drinking and drug intoxication interfere<br />

with the person’s ability to conform to tacit social<br />

rules governing daily activities—such as keeping<br />

appointments, caring for children, or performing a<br />

job properly—that are typically expected by the person’s<br />

reference group. Substance use also results in<br />

mental and medical consequences. Thus, a key aspect<br />

<strong>of</strong> the dependence syndrome is the persistence <strong>of</strong><br />

substance use in spite <strong>of</strong> social, psychological, or<br />

physical harm—such as loss <strong>of</strong> employment, marital<br />

problems, depressive symptoms, accidents, and liver<br />

disease. This indicates that substance use is given a<br />

higher priority than other activities, in spite <strong>of</strong> its<br />

negative consequences.<br />

One explanation for the salience <strong>of</strong> drug- and alcohol-seeking<br />

behaviors despitenegativeconsequencesis<br />

the relative reinforcement value <strong>of</strong> immediate and long-<br />

DIAGNOSIS OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS: DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA<br />

ICD-10 symptoms<br />

Progressive neglect <strong>of</strong> alternative activities in<br />

favor <strong>of</strong> substance use<br />

Persistence with substance use despite harmful<br />

consequences<br />

A strong desire or sense <strong>of</strong> compulsion to drink<br />

or use drugs<br />

Evidence <strong>of</strong> impaired capacity to control substance<br />

use in terms <strong>of</strong> its onset, termination, or levels<br />

<strong>of</strong> use<br />

Increased doses <strong>of</strong> substance are required to<br />

achieve effects originally produced by lower<br />

doses<br />

A physiological withdrawal state<br />

Use to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms and<br />

subjective awareness that this strategy is effective<br />

DSM-IV symptoms<br />

Important social, occupational, or<br />

recreational activities given up<br />

Continued use despite psychological or<br />

physical problems<br />

Substance <strong>of</strong>ten taken in larger amounts<br />

or over a longer period than intended<br />

Any unsuccessful effort or a persistent<br />

desire to cut down or control substance<br />

use<br />

Either (a) increased amounts needed to<br />

achieve desired effect; or (b) markedly<br />

diminished effect with continued use<br />

Either (a) characteristic withdrawal<br />

syndrome for substance; or (b) the<br />

same substance taken to relieve or<br />

avoid symptoms<br />

Table 2. ICD and DSM Diagnostic Criteria for Dependence (labeled according to diagnostic level—physiological, cognitive, and<br />

behavioral—and underlying dependence elements). ILLUSTRATION BY GGS INFORMATION SERVICES. GALE, CENGAGE LEARNING<br />

term consequences. For many alcoholics and drug<br />

abusers, the immediate positive reinforcing effects <strong>of</strong><br />

the substance, such as euphoria or stimulation, far outweigh<br />

any delayed negative consequences, which may<br />

occur either infrequently or inconsistently.<br />

Impaired Control. The main characteristic <strong>of</strong><br />

impaired control is the lack <strong>of</strong> success in limiting<br />

the amount or frequency <strong>of</strong> substance use. For<br />

example, the alcoholic wants to stop drinking, but<br />

repeated attempts to do so have been unsuccessful.<br />

Typically, rules and other stratagems are used to<br />

avoid alcohol entirely or to limit the frequency <strong>of</strong><br />

drinking. A resumption <strong>of</strong> heavy drinking after<br />

receiving pr<strong>of</strong>essional help for a drinking problem<br />

is evidence <strong>of</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> success. The symptom is<br />

considered present if the drinker has repeatedly<br />

failed to abstain or has only been able to control<br />

drinking with the help <strong>of</strong> treatment, mutual-help<br />

groups, or removal to a controlled environment<br />

(e.g., prison).<br />

In addition to an inability to abstain, impaired<br />

control is also reflected in the failure to regulate the<br />

amount <strong>of</strong> alcohol or drug consumed on a given<br />

occasion. The cocaine addict vows to snort only a<br />

small amount but then continues until the entire<br />

supply is used up. For the alcoholic, impaired<br />

control includes an inability to prevent the spontaneous<br />

onset <strong>of</strong> drinking bouts, as well as a failure to stop<br />

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF DRUGS, ALCOHOL & ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR, 3RD EDITION 11

DIAGNOSIS OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS: DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA<br />

Symptom<br />

Craving<br />

Tremor<br />

Sweating, fever<br />

Nausea or vomiting<br />

Malaise, fatigue<br />

Hyperactivity, restlessness<br />

Headache<br />

Insomnia<br />

Hallucinations<br />

Convulsions<br />

Delirium<br />

Irritability<br />

Anxiety<br />

Depression<br />

Difficulty concentrating<br />

Gastrointestinal disturbance<br />

Increased appetite<br />

Diarrhea<br />

<strong>Alcohol</strong><br />

drinking before intoxication. This behavior should be<br />

distinguished from situations in which the drinker’s<br />

‘‘control’’ over the onset or amount <strong>of</strong> drinking is<br />

regulated by social or cultural factors, such as during<br />

college beer parties or fiesta drinking occasions. One<br />

way to judge the degree <strong>of</strong> impaired control is to<br />

determine whether the drinker or drug user has made<br />

repeated attempts to limit the quantity <strong>of</strong> substance<br />

use by making rules or imposing limits on his or<br />

her access to alcohol or drugs. The more these<br />

attempts have failed, the more the impaired control is<br />

present.<br />

Tolerance. Tolerance isadecreaseinresponsetoa<br />

psychoactive substance that occurs with continued<br />

use. For example, increased doses <strong>of</strong> heroin are<br />

required to achieve effects originally produced by<br />

lower doses. Tolerance may be physical, behavioral,<br />

or psychological. Physical tolerance is a change in<br />

cellular functioning. The effects <strong>of</strong> a dependenceproducing<br />

substance are reduced, even though the<br />

cells normally affected by the substance are subjected<br />

to the same concentration. A clear example is the<br />

finding that alcoholics can drink amounts <strong>of</strong> alcohol<br />

(e.g., a quart <strong>of</strong> vodka) that would be sufficient to<br />

incapacitate or kill nontolerant drinkers.<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

Amphetamine<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

Caffeine<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

Cocaine<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

Opioids<br />

X<br />

Tolerance may also develop at the psychological<br />

and behavioral levels, independent <strong>of</strong> the biological<br />

adaptation that takes place. Psychological<br />

tolerance occurs when a marijuana smoker or heroin<br />

user no longer experiences a ‘‘high’’ after the<br />

initial dose <strong>of</strong> the substance. <strong>Behavior</strong>al tolerance is<br />

a change in the effect <strong>of</strong> a substance because the<br />

person has learned to compensate for the impairment<br />

caused by a substance. Some alcoholics, for<br />

example, can operate machinery at moderate doses<br />

<strong>of</strong> alcohol without impairment.<br />

Withdrawal Signs and Symptoms. A ‘‘withdrawal<br />

state’’ is a group <strong>of</strong> symptoms occurring<br />

after cessation <strong>of</strong> substance use. It usually occurs<br />

after repeated, and usually prolonged, drinking or<br />

drug use. Both the onset <strong>of</strong> and course <strong>of</strong> withdrawal<br />

symptoms are related to the type <strong>of</strong> substance<br />

and the dose being used immediately<br />

prior to abstinence. Table 3 lists some common<br />

withdrawal symptoms associated with different psychoactive<br />

substances. Some drugs, such as hallucinogens,<br />

do not typically produce a withdrawal syndrome<br />

after cessation <strong>of</strong> use. Although generally<br />

thought <strong>of</strong> as not being characterized by withdrawal<br />

symptoms, recent evidence supports the<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

Nicotine<br />

X<br />

Table 3. Withdrawal symptoms associated with different psychoactive substances. ILLUSTRATION BY GGS INFORMATION SERVICES. GALE,<br />

CENGAGE LEARNING<br />

12 ENCYCLOPEDIA OF DRUGS, ALCOHOL & ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR, 3RD EDITION<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X<br />

X

existence <strong>of</strong> a cannabis (marijuana) withdrawal syndrome<br />

(Agrawal et al., 2008).<br />

<strong>Alcohol</strong> withdrawal symptoms follow within<br />

hours <strong>of</strong> the cessation or reduction <strong>of</strong> prolonged<br />

heavy drinking. These symptoms include tremor,<br />

hyperactive reflexes, rapid heartbeat, hypertension,<br />

general malaise, nausea, and vomiting. Seizures and<br />

convulsions may occur, particularly in people with a<br />

preexisting seizure disorder. Patients may have hallucinations,<br />

illusions, or vivid nightmares, and sleep<br />

is usually disturbed. In addition to physical withdrawal<br />

symptoms, anxiety and depression are also<br />

common. Some chronic drinkers never have a long<br />

enough period <strong>of</strong> abstinence to permit withdrawal<br />

to occur.<br />

The use <strong>of</strong> a substance with the intention <strong>of</strong><br />

relieving withdrawal symptoms and with awareness<br />

that this strategy is effective are cardinal<br />

symptoms <strong>of</strong> dependence. Morning drinking to<br />

relieve nausea or the ‘‘shakes’’ is one <strong>of</strong> the most<br />

common manifestations <strong>of</strong> physical dependence in<br />

alcoholics.<br />

Other Features <strong>of</strong> Dependence. To be labeled<br />

dependence, symptoms must have persisted for at<br />

least one month or must have occurred repeatedly<br />

(two or more times) over a longer period <strong>of</strong> time.<br />

The patient does not need to be using the substance<br />

continually to have recurrent or persistent<br />

problems. Some symptoms (e.g., craving) may<br />

occur repeatedly whether the person is using the<br />

substance or not.<br />

Many patients with a history <strong>of</strong> dependence<br />

experience a rapid reinstatement <strong>of</strong> the syndrome<br />

following resumption <strong>of</strong> substance use after a<br />

period <strong>of</strong> abstinence. Rapid reinstatement is a<br />

powerful diagnostic indicator <strong>of</strong> dependence. It<br />

points to the impairment <strong>of</strong> control over substance<br />

use, the rapid development <strong>of</strong> tolerance, and frequently,<br />

physical withdrawal symptoms.<br />

Patients who receive opiates or other drugs for<br />

pain relief following surgery (or for a malignant<br />

disease such as cancer) sometimes show signs <strong>of</strong> a<br />

withdrawal state when the use <strong>of</strong> these drugs is<br />

terminated. The great majority <strong>of</strong> these individuals<br />

have no desire to continue taking such drugs, and<br />

they therefore do not fulfill the criteria for<br />

DIAGNOSIS OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS: DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA<br />

dependence. The presence <strong>of</strong> a physical withdrawal<br />

syndrome in these patients does not necessarily<br />

indicate dependence, but rather a state <strong>of</strong> neuroadaptation<br />

to the drug that was being administered.<br />

It is commonly assumed that severe dependence is<br />

not reversible, and this assumption is supported by<br />

the rapid reinstatement <strong>of</strong> dependence symptoms<br />

when drinking or drug use is resumed after a period<br />

<strong>of</strong> detoxification.<br />

CATEGORICAL VERSUS DIMENSIONAL<br />

APPROACHES TO DIAGNOSIS<br />

Clinical decision-making <strong>of</strong>ten requires the classification<br />

<strong>of</strong> a patient’s condition into discrete categories<br />

reflecting whether a disorder such as alcohol<br />

dependence is present or absent. This kind <strong>of</strong> categorical<br />

thinking is convenient for the diagnostician<br />

and consistent with the way in which physical diseases<br />

are diagnosed, but it may not fit the way in which<br />

substance use disorders are manifested in clinical<br />

practice. Typically, people with substance use disorders<br />

vary widely in the severity <strong>of</strong> their symptoms,<br />

with no clear demarcation between mild, moderate,<br />

and severe cases. This makes it difficult to diagnose<br />

patients whose problems with substance use are at<br />

the threshold between mild and moderate severity.<br />

For this reason, it has been proposed that the fifth<br />

revision <strong>of</strong> the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual<br />

(DSM-V) include the option <strong>of</strong> rating patients’ substance<br />

use disorders along a continuum that reflects<br />

the actual severity <strong>of</strong> their dependence or abuse<br />

(Helzer et al., 2006). The concept <strong>of</strong> a continuum<br />

<strong>of</strong> alcohol dependence with various levels <strong>of</strong> severity<br />

is consistent with the original formulation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

dependence syndrome (Edwards et al., 1981), and<br />

it has been supported empirically by psychometric<br />

studies (Hasin, Liu, et al., 2006).<br />

MAKING A DISTINCTION BETWEEN ABUSE<br />

AND DEPENDENCE<br />

Questions have been raised about whether two diagnoses<br />

are needed for substance use disorders, or<br />

whether one diagnosis that combines abuse and<br />

dependence criteria in some form could be more<br />

efficient while still being reliable and valid. A number<br />

<strong>of</strong> studies using factor analysis have shown that two<br />

factors are generally found to fit existing data better<br />

than a single factor, but that the two factors are very<br />

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF DRUGS, ALCOHOL & ADDICTIVE BEHAVIOR, 3RD EDITION 13

DIAGNOSIS OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS: DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA<br />

highly correlated (Hasin, Hatzenbuehler, et al.,<br />

2006). In the first decade <strong>of</strong> the twenty-first century,<br />

investigators have used Item Response Theory (IRT)<br />

analysis to examine alcohol abuse and dependence<br />

criteria in general population data (Saha et al.,<br />

2006). These investigators found that alcohol abuse<br />

and dependence criteria appear to combine well into<br />

a single continuum <strong>of</strong> severity, with some abuse criteria<br />

(e.g., interpersonal problems related to drinking,<br />

failure to perform in major roles) actually indicating<br />

more severe aspects <strong>of</strong> dependence than some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

currently used dependence criteria (e.g., drinking<br />

more or longer than intended). However, whether<br />

these findings will extend to other substances remains<br />

a question to be answered by further research.<br />