100516 Counting the old way - Pilipino Express

100516 Counting the old way - Pilipino Express

100516 Counting the old way - Pilipino Express

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

DNA Directed Assembly ofNanoparticle and Nanowire Arraysfor Biosensing ApplicationsJanos VörösLaboratory of Biosensors and Bioelectronics,Institute for Biomedical Engineering,University and ETH Zurich, Switzerlandhttp://www.lbb.ethz.ch

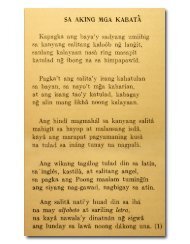

Paul Morrow • In O<strong>the</strong>r Words • The <strong>Pilipino</strong> <strong>Express</strong> • May 16 - 31, 20102simple matter to attach <strong>the</strong> basicnumerals (one to nine) to whatevermultiple of ten, hundred, thousand orwhatever large sum we need. So,when we add one to 20, we simplysay twenty-one in English, vingt et unin French, veintiuno in Spanish anddalawampu’t isa in Filipino.This seems like <strong>the</strong> obvious <strong>way</strong> tocount in any language but it is not –and it was not al<strong>way</strong>s like this in Tagalogei<strong>the</strong>r. Even though Tagalog hasits own words for numbers, <strong>the</strong> Spanishlanguage influenced <strong>the</strong> <strong>way</strong> wecount today in Filipino.In <strong>the</strong> <strong>old</strong> Tagalog counting system,<strong>the</strong> numerals from one to 20 were <strong>the</strong>same as <strong>the</strong>y are today and so waseach multiple of ten, hundred, thousandand million. That is to say, dalawampu= 20, tatlong daan = 300, apatna libo = 4000, etc.However, <strong>the</strong> numerals in between<strong>the</strong> zeros were very different. Thenumber 21, for example, was not dalawampu’tisa as we’d expect; it wasmaikatlong isa, meaning “one in <strong>the</strong>third set of ten.” The first set of tenbeing zero to nine, <strong>the</strong> second set 10to 19 and <strong>the</strong> third set 20 to 29.The prefix maika- al<strong>way</strong>s referred to<strong>the</strong> next highest set of ten, hundred,thousand, etc. For example, maikapatdalawa meant “two in <strong>the</strong> fourth [setof ten]” or 32. This pattern continueduntil maikaraan siyam, “nine in <strong>the</strong>100 set”, which meant 99.Labí [in excess] was used for <strong>the</strong>numbers between 10 and 20, just liketoday. When we say <strong>the</strong> number 11,labing isa, it means “one in excess often,” but we don’t say <strong>the</strong> word pu[ten] because it is understood. Thedifference in <strong>the</strong> <strong>old</strong> Tagalog methodwas that labí was also used consistentlyfor <strong>the</strong> first set of numbersabove one hundred, one thousand,one laksa (10,000), one yuta(100,000) and one million. (See <strong>the</strong>chart of <strong>old</strong> numbers.)New Tagalog numeralsApparently, some Filipinos in <strong>the</strong>early colonial period were eager tolearn Spanish. This is why TomásPinpin wrote his manual in 1610.Eventually <strong>the</strong>y borrowed not onlymany Spanish words and numerals,but <strong>the</strong>y also adapted <strong>the</strong> Spanishmethod of counting to <strong>the</strong> Tagalognumerals.It is possible that it was not so much<strong>the</strong> Spanish language that influencedTagalog counting as much as it was<strong>the</strong> digits that <strong>the</strong> Spaniards used.Pre-Hispanic people of <strong>the</strong> Philippinesdid not have digits like 1, 2, 3,etc., in <strong>the</strong>ir baybayin writing system.They just spelled out <strong>the</strong>ir numerals<strong>the</strong> same as words.Tomás Pinpin took great pains toexplain to his readers what we call <strong>the</strong>Arabic numerals (though <strong>the</strong>y actuallyoriginated in India). When he explainedthat <strong>the</strong> meaning of a digitdepends on its position in a string ofdigits, Pinpin illustrated his point wi<strong>the</strong>xamples of large numbers. In <strong>the</strong>senumbers he stated <strong>the</strong> value of eachdigit separately ra<strong>the</strong>r than just writingout <strong>the</strong> Tagalog phrase for <strong>the</strong> completenumber. This <strong>way</strong> of learning <strong>the</strong>Hindu-Arabic digits might have affected<strong>the</strong> <strong>way</strong> that Tagalogs countedall <strong>the</strong> numbers higher than twenty.Pinpin wrote:Datapoua’t con ang sulat ay 1234 samacatouid ay labi sa libo dalauangdaan, at maycapat apat, ay ano yaongna onang letra dili caya sang libo;yayamang 1 nga at may casonod pangtatlo at yaong icalaua, dili caya dalauangdaan; yayamang 2 nga at maycasonod pang dalaua, at yaong icatlo’ydili caya tatlong pouo: yayamang3 nga at may casonod pang isa, atyaong uacas ay dili caya apat na lamang;yayamang 4 nga at uala nangcasonod.[However, if 1234 is written, it is<strong>the</strong>refore one thousand, two hundredand thirty-four and what is that firstletter [meaning digit] but one thousandbecause it is a 1 and it is followedby three more [digits] and thatsecond [digit] is none o<strong>the</strong>r than twohundred because it is a 2 with twomore [digits] following it and thatthird [digit] is but thirty because it is a3 followed by one more [digit] andthat last one is only four because it is a4 and nothing more follows it.]The <strong>old</strong> <strong>way</strong> is forgottenIt is hard to imagine how <strong>the</strong> ancientTagalogs could do any calculations ortransactions with <strong>the</strong> <strong>old</strong> system ofnumerals, especially since <strong>the</strong>y didn’thave digits – but apparently, <strong>the</strong>ymanaged. Jean-Paul Potet wrote <strong>the</strong>following in his 1992 article:My interpretation is that computationand numerical expressions wereentirely separated. The former dependedon an abacus drawn with astick on <strong>the</strong> ground, which, for all itsThe Old Tagalog<strong>Counting</strong> SystemNumbers 1–20 are <strong>the</strong> same asmodern Filipino.1, 2, 3, etc…….…...... isa, dalawa, tatlo11, 12 ..…........ labing isa, labindalawa20 .........……....................... dalawampu21 ..........…........…......... maikatlong isa22 .............….......... maikatlong dalawa30 ..................…….................... tatlumpu31 ...............…....…............ maikapat isa80 ...................…….................. walumpu81 ...................……....... maikasiyam isa90 .............................….......... siyamnapu99 ............................. maikaraang siyam100 ........................................ isang daan101 ............................... labi sa raang isa111 ..…............ labi sa raang labing isa121 ......... labi sa raang maikatlong isa200 ................................. dalawang daan201 ..................... maikatlong daang isa300 ...................................... tatlong daan301 .................... maikapat na raang isa1000 ......................................... isang libo1001 ............................ labi sa libong isa2000 ................................. dalawang libo2001 ................... maikatlong libong isa9000 ................................... siyam na libo9001 ........................... maikalaksang isa10,000 ................................... isang laksa10,011 .......... labi sa laksang labing isa20,000 ........................... dalawang laksa22,000 maikatlong laksang dalawang libo90,000 ............................. siyam na laksa90,001 ......................... maikayutang isa100,000 ................................... isang yuta100,001 ...................... labi sa yutang isa200,000 .......................... dalawang yuta200,001 ..............maikatlong yutang isa1,000,000 ............. isang angaw-angawcrudeness, was in no <strong>way</strong> inferior toany figure drawn on a blackboardby a ma<strong>the</strong>matics teacher. The use ofsmall pebbles as tokens should notdeter us from concluding that thistechnique must have been fairlysophisticated; after all, didn’t calculus[reckoning] mean “small pebbles”in Latin? Once <strong>the</strong> result wasobtained in this silent (?) <strong>way</strong>, it wasread aloud and/or taken down in<strong>the</strong>ir syllabic script.Even so, it seems that <strong>the</strong> new Tagalognumerals, which we use today,were adopted quite early in <strong>the</strong> colonialera. The archive at <strong>the</strong> Universityof Santo Tomas has two <strong>old</strong> bills ofsale written in <strong>the</strong> baybayin script in1613 and 1625. The dates in <strong>the</strong>sedocuments were written using <strong>the</strong> newnumerical expressions. In <strong>the</strong> 1625

Paul Morrow • In O<strong>the</strong>r Words • The <strong>Pilipino</strong> <strong>Express</strong> • May 16 - 31, 20103document <strong>the</strong> date was a mixture of<strong>the</strong> <strong>old</strong> and new systems. The year1625 was written [isang] libo, animna raang taon, maikatlong limangtaon, but in strict ancient Tagalogcounting, this number would havebeen expressed, labi sa libong maikapitongraang maikatlong lima.(These two baybayin documents canbe seen on my web site, Sarisari etc.)Sources:Eventually <strong>the</strong> <strong>old</strong> <strong>way</strong> of countingwas forgotten. In 1745, one Spanishfriar, Sebastian Totanes, explained <strong>the</strong><strong>old</strong> Tagalog counting system in hisArte de la Lengua Tagala, after whichhe added <strong>the</strong> comment, “now, due tocommunication with Spaniards, manyof <strong>the</strong>m [<strong>the</strong> Tagalogs] count like us,and so <strong>the</strong>y say: ‘Dalawampu’t isa’,twenty-one. ‘Sangdaan at lima,’ onehundred five. ‘Limang daang dalawampu’tlima,’ five hundred andtwenty-five, and it is like that with <strong>the</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r numbers.”E-mail <strong>the</strong> author at:feedback@pilipino-express.com orvisit www.mts.net/~pmorrow formore Filipino history and language.Dáluz, Eusebio T. (1915) Filipino-English Vocabulary with practical examples of Filipino and English grammars.Laktaw, Pedro Serrano (1889) Diccionario Hispano-Tagalog.Laktaw, Pedro Serrano (1914) Diccionario Tagálog-Hispano.Noceda, Juan de & San Lucar, Pedro de (1754) Vocabulario de la lengua tagala. Manila 1860.Pinpin, Tomas (1610), Librong Pagaaralan nang manga Tagalog nang uicang Castilla. Manila 1910.Potet, Jean Paul (1992). Numerical <strong>Express</strong>ions in Tagalog. (Thanks to <strong>the</strong> author for kindly sharing excerpts fromhis revised, expanded and unpublished book based on his article.)Rafael, Vicente L. (1988) Contracting Colonialism - Translation and Christian Conversion in Tagalog Society underSpanish Rule.San Agustin, Gaspar de (1703) Compendio del Arte de la Lengua Tagala. Manila 1879.Totanes, Sebastian de (1745) Arte de la Lengua Tagala y Manual Tagalog. Binondo 1865.Woods, Damon L. (1992) Tomás Pinpin and <strong>the</strong> Literate Indio: Tagalog Writing in <strong>the</strong> Early Spanish Philippines.