- Page 3:

Crop yieldresponse to waterFAOIRRIG

- Page 16 and 17:

1. IntroductionFood production and

- Page 21:

Lead AuthorsMartin Smith(formerly F

- Page 31:

3. Yield response to waterof herbac

- Page 40 and 41:

The WP parameter introduced in Aqua

- Page 43 and 44:

figure 7 The root zone depicted as

- Page 47 and 48:

threshold and 1.0 at the lower thre

- Page 50 and 51:

also calculated by multiplying with

- Page 53:

FIGURE 14 Schematic representation

- Page 57 and 58:

figure 17ClimateInput data defining

- Page 59 and 60:

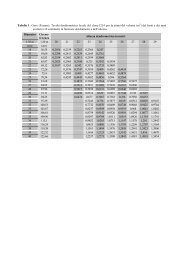

Table 1 Conservative crop parameter

- Page 62:

figure 18 The Main AquaCrop menu.di

- Page 67:

Applications to Irrigation Manageme

- Page 72:

Box 1 Simulating deficit irrigation

- Page 75 and 76:

for each planting date. If there ar

- Page 77:

ox 2 (CONTINUED)FIGURE 1 Difference

- Page 83 and 84:

Heng, L.K., Hsiao,T.C., Evett, S.,

- Page 88 and 89:

Table 2Additional information and d

- Page 90 and 91:

capacity (FC) and permanent wilting

- Page 95 and 96:

densities. This range is referred t

- Page 97 and 98:

Table 3Comparison of simulated with

- Page 99 and 100:

In Equation 3 C a is the mean air C

- Page 102:

REFERENCESAllen, R., Pereira, L., R

- Page 107 and 108:

Lead AuthorSenthold Asseng(formerly

- Page 109 and 110:

Figure 1 World wheat harvested area

- Page 113 and 114:

When nutrition is limiting, yield p

- Page 116:

wheat 101

- Page 120 and 121:

Figure 1 World rice harvested area

- Page 123:

Response to StressesBecause rice ev

- Page 129 and 130:

Lead AuthorTheodore C. Hsiao(Univer

- Page 132 and 133:

emergence to flowering is about 65

- Page 135 and 136:

ReferencesAyers, R.S. & Westcot, D.

- Page 140:

Figure 1 World soybean harvested ar

- Page 144 and 145:

A number of studies indicate that s

- Page 146:

ReferencesBhatia, V.S., Piara Singh

- Page 150 and 151:

Figure 1 World barley harvested are

- Page 152:

Barley development may be thought o

- Page 155 and 156:

The seasonal water requirements for

- Page 159 and 160:

Lead AuthorSuhas P. Wani(ICRISAT, A

- Page 161:

sowing usually starts in late Septe

- Page 164 and 165:

loss. If water stress is severe eno

- Page 166:

ReferencesFAO. 2011. FAOSTAT online

- Page 170:

Figure 1 World cotton harvested are

- Page 173:

Response to StressesCotton stands o

- Page 176:

FAO. 2011. FAOSTAT online database,

- Page 181 and 182:

spring. In double cropping, sowing

- Page 183 and 184:

size as affected by soil water defi

- Page 186:

sunflower 171

- Page 191 and 192:

to produce energy (electricity from

- Page 193 and 194:

Response to stressLow temperatureSu

- Page 196:

Sugarcane 181

- Page 200 and 201:

Figure 1 World potato harvested are

- Page 202 and 203:

initiation, vigorous canopy, profus

- Page 204:

ReferencesBradshaw, J.E. 2009. A ge

- Page 209 and 210:

Tomato requires soils with proper w

- Page 211 and 212:

and there is frequent wetting of ex

- Page 213 and 214:

is so excessive that fruit setting

- Page 217 and 218:

Lead AuthorsMichele Rinaldi(CRA, Ba

- Page 219 and 220:

North Africa and near East ranges f

- Page 221 and 222:

Water use & ProductivitySugar beets

- Page 223 and 224:

ReferencesAllen, R.G., Pereira, L.S

- Page 228 and 229:

Figure 1 Alfalfa harvested area (SA

- Page 231 and 232:

Water use & ProductivityAs a perenn

- Page 233 and 234:

SalinityAlfalfa is tolerant to rela

- Page 237 and 238:

Lead AuthorAsha Karunaratne(formerl

- Page 239 and 240:

Generally, the growing season begin

- Page 241 and 242:

FAO. 2011. FAOSTAT online database,

- Page 244 and 245:

*Flower and grain colour presented

- Page 246 and 247:

Figure 1 World quinoa harvested are

- Page 248 and 249:

with typical values around 10.5 g/m

- Page 250:

ReferencesAlvarez-Jubete, L., Arend

- Page 254 and 255:

Growth and developmentThe common me

- Page 256 and 257:

soils (EARO, 2002). Tef has some to

- Page 258:

tef 243

- Page 261 and 262:

Lead AuthorsElias Fereres(Universit

- Page 264:

equirements per unit land area for

- Page 268 and 269:

figure 6 The water balance of an or

- Page 270 and 271:

ox 2 Understanding the transpiratio

- Page 272:

Orchard transpirationTree Tr is det

- Page 276 and 277:

ox 4 Sample calculation of E dz , E

- Page 278 and 279:

ox 5 Computing olive tree transpira

- Page 280 and 281:

FIGURE 10 Crop coefficient (K c ) c

- Page 282 and 283:

For training systems on a vertical

- Page 284 and 285:

ox 7Consumptive and non-consumptive

- Page 286 and 287:

are seeking more precision in their

- Page 288 and 289:

ox 9 Examples of soil water monitor

- Page 290 and 291:

ox 10 (CONTINUED)The major limitati

- Page 292 and 293:

ox 12Definition of CWSI and an exam

- Page 294 and 295:

The water budget methodWith this me

- Page 296 and 297:

ox 15 Evolution of soil water under

- Page 298 and 299:

opening and photosynthesis relative

- Page 300 and 301:

that occur during the periods of fr

- Page 302 and 303:

The crop, where price can vary more

- Page 304:

Modify horticultural practicesPruni

- Page 307 and 308:

FIGURE 13Comparison of yield per un

- Page 309 and 310:

season. Thus the risks of salinity

- Page 312:

4.1 Fruit trees and vinesEditor:Eli

- Page 315 and 316:

Figure 1 Production trends for oliv

- Page 317 and 318:

Figure 2Occurrence and duration of

- Page 320 and 321:

The use of displacement sensors to

- Page 322 and 323:

Figure 4 Relationship between relat

- Page 324 and 325:

Table 3 Sample calculation of month

- Page 326 and 327:

clayey soils. If supply is very lim

- Page 329:

Lead AuthorDavid A. Goldhamer(forme

- Page 332 and 333:

Fruit growth during this stage is t

- Page 334 and 335:

Season-long stressSeveral studies h

- Page 336 and 337:

Table 1Published monthly crop coeff

- Page 339 and 340:

Four crop-water-production function

- Page 341 and 342:

size distribution toward more favou

- Page 344 and 345:

Lead AuthorSAmos Naor(GRI, Universi

- Page 346 and 347:

Apples tend to have a biennial bear

- Page 348 and 349:

water stress and thus highly respon

- Page 351 and 352:

indicate that deficit irrigation ad

- Page 353 and 354:

Figure 7Effect of midday light inte

- Page 355 and 356:

Figure 10Response of marketable fru

- Page 357:

Failla, O., Zocchi, Z., Treccani, C

- Page 360 and 361:

Figure 1 Production trends for plum

- Page 362 and 363:

soil water. In young orchards, post

- Page 364 and 365:

Figure 3 Relationships between rela

- Page 366:

ReferencesAllen, R.G., Pereira, L.S

- Page 369 and 370:

Figure 1 Production trends for almo

- Page 371 and 372:

FIGURE 2The three stages of almond

- Page 373 and 374:

Figure 3Differences in the cultivar

- Page 375 and 376:

Indicators of tree water statusTo p

- Page 377 and 378:

nuts are rapidly expanding and late

- Page 379 and 380:

ReferencesAyars, J.E., Johnson, R.

- Page 381 and 382:

Table 2 (Continued)Year TreatmentWa

- Page 383:

Table 3 (continued)Potential900 mmA

- Page 386 and 387:

Figure 1 Production trends for pear

- Page 388 and 389:

(Elkins et al., 2007). The appearan

- Page 390 and 391:

out in Spain under more common grow

- Page 392 and 393:

Figure 4Relationships between the p

- Page 394 and 395:

Data in Figure 5 suggest that there

- Page 396 and 397:

e saved, but this causes a reductio

- Page 398:

pear 389

- Page 401 and 402:

Figure 1 Production trends for peac

- Page 403 and 404:

Figure 2bEvolution of vegetative (s

- Page 405 and 406:

The postharvest period is important

- Page 407 and 408:

the midday stem-water potential in

- Page 409 and 410:

PHOTOPeach leaf appearance under th

- Page 411 and 412:

FIGURE 5Relation between the crop c

- Page 413 and 414:

In applying RDI strategies an impor

- Page 415:

peach 407

- Page 418 and 419:

Figure 1 Production trends of walnu

- Page 420: 1 100 mm, a team in California appl

- Page 423 and 424: Figure 1 Production trends for pist

- Page 425 and 426: There are two types of shoot growth

- Page 427 and 428: FIGURE 3Time course development of

- Page 429 and 430: Stage III was the most stress sensi

- Page 431: (see Chapter 4), as in other specie

- Page 434 and 435: Table 2 Suggested RDI strategies fo

- Page 437 and 438: Lead AuthorSCristos Xiloyannis(Univ

- Page 439 and 440: is completed within 20 days; therea

- Page 441 and 442: or peach. However, because fruit is

- Page 443 and 444: to a midday value varying between -

- Page 446 and 447: Lead AuthorRaúl Ferreyraand Gabrie

- Page 448 and 449: The most critical developmental per

- Page 450 and 451: Figure 4Effects of the level of app

- Page 453 and 454: Lead AuthorJordi Marsal(IRTA, Lleid

- Page 455 and 456: water stress should not be imposed

- Page 457 and 458: Under certain growing conditions, s

- Page 459 and 460: ReferencesAntunez A., Stockle, C. &

- Page 463 and 464: Lead AuthorSVictor O. Sadras(SARDI

- Page 465 and 466: Current season inflorescences becom

- Page 467 and 468: the actual timing of each critical

- Page 469: environments, rainfall pulses and l

- Page 473 and 474: Table 3Yield and yield components o

- Page 475 and 476: Figure 9Wine quality score as a fun

- Page 477 and 478: Figure 11Wine attributes of Tempran

- Page 479 and 480: (McCarthy and Coombe, 1999), but ev

- Page 481 and 482: Figure 15Relative yield as a functi

- Page 484: Shiraz, Grenache and Mourvèdre in

- Page 487 and 488: Girona, J., Mata, M., del Campo, J.

- Page 491 and 492: Lead AuthorSCristos Xiloyannis(Univ

- Page 493 and 494: Figure 2Seasonal pattern of the lea

- Page 495 and 496: Figure 5Fraction of the exposed and

- Page 497 and 498: FIGURE 9Soil volume explored by roo

- Page 499 and 500: Water Requirements and IrrigationMa

- Page 501 and 502: 5. EpilogueThis publication, Irriga

- Page 503 and 504: operating systems (e.g., Linux, Uni

- Page 505: Crop yield response to waterAbstrac