Crop yield response to water - Cra

Crop yield response to water - Cra

Crop yield response to water - Cra

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

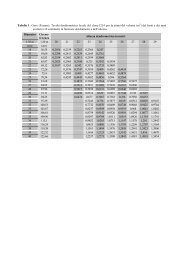

techniques; d) relations between <strong>yield</strong> and <strong>water</strong> use; and e) <strong>water</strong> management strategiessuggested under limited <strong>water</strong> supply.World trends in fruit tree and vine productionThe rapid rate of world economic development in recent decades has been accompanied bymany transformations; an important one is the change in human diet, such as the increase indemand for animal products in many emerging economies. In most countries, health-relatedconcerns have led <strong>to</strong> a renewed interest and increased consumption of fruit and vegetables.Strong consumer demand has resulted in the production of high-quality horticultural products;a very high priority of both public and private institutions worldwide. This increased demandfor fruit is expected <strong>to</strong> continue and presents an incentive for growers <strong>to</strong> develop efficienthorticultural industries, which in most areas will be dependent on irrigation.Current <strong>water</strong> demands by other sec<strong>to</strong>rs of society require that the agricultural sec<strong>to</strong>r reduces<strong>water</strong> use for irrigation; the world primary user of diverted (developed) <strong>water</strong>. Indeed, currentagricultural <strong>water</strong> use is considered by some competing interests simply another ‘source’ of <strong>water</strong>,since the development of additional <strong>water</strong> supplies has been limited, especially in developedcountries. In many parts of the world, one result of reduced <strong>water</strong> supply for agriculture hasbeen a shift in cropping patterns <strong>to</strong> economically more viable crops; from annual field crops <strong>to</strong>horticultural crops, such as fruit trees and vegetables. Figure 1 shows that the areas devoted <strong>to</strong>growing fruit and vines in a number of countries have increased significantly over the last 20years, indicating that this is a general trend in irrigated agriculture in most parts of the world.Recent improvement of irrigation and management methods have reduced irrigation-related<strong>water</strong> losses, thus decreasing the amount of applied <strong>water</strong> per unit of irrigated land. Both theshifts <strong>to</strong>wards high-value crops and <strong>to</strong>wards higher application efficiency suggest that more<strong>water</strong> should be available for irrigation of trees and vines. However, these improvements havecoincided with an expansion of irrigated land, <strong>to</strong> the extent that most of the <strong>water</strong> saved hasgenerally been used <strong>to</strong> irrigate additional land or crops that have higher <strong>water</strong> requirements.In many cases, the <strong>water</strong> requirements of tree crops exceed those of the major field crops thatwere previously grown in these areas. Therefore, the availability of <strong>water</strong> for tree and vineirrigation most likely will continue <strong>to</strong> decline. This will be more so in areas where the supplieshave been stretched <strong>to</strong> the limit and where environmental <strong>water</strong> needs are considered highpriority by society and are in direct competition with irrigation needs.Towards intensification in fruit and vine productionThe general trend in fruit-tree production over the last decades, as in other forms ofagriculture, has been <strong>to</strong>wards intensification. This trend is manifested as an increase intree or vine density, often coupled with the use of dwarfing roots<strong>to</strong>cks <strong>to</strong> reduce treevigour. There are many reasons for the success of these intensive plantations, relative <strong>to</strong>those that are traditional low density. Greater radiation interception results in increasedcarbon assimilation and productivity and lower vigour reduces pruning needs and oftenharvesting costs; both of which are significant expenses in orchard production. Since access<strong>to</strong> the orchard is improved because the drive rows (areas between the tree rows) are notusually wetted by microirrigation, pest control applications are easier and on time. In short,high-intensity orchards are more manageable. Their major limitation is the higher capitalYield Response <strong>to</strong> Water of Fruit Trees and Vines 247