Mamta Kalia - Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi Vishwavidyalaya

Mamta Kalia - Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi Vishwavidyalaya

Mamta Kalia - Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi Vishwavidyalaya

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

A Journal of<strong>Mahatma</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong><strong>Antarrashtriya</strong><strong>Hindi</strong> <strong>Vishwavidyalaya</strong>L A N G U A G EDISCOURSEW R I T I N GVolume 4January-March 2010Editor<strong>Mamta</strong> <strong>Kalia</strong>Kku 'kkafr eS=khPublished by<strong>Mahatma</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong> International <strong>Hindi</strong> University

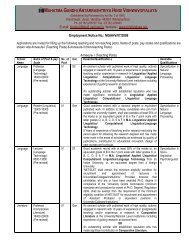

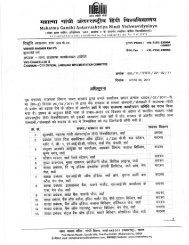

<strong>Hindi</strong> : Language, Discourse, WritingA Quarterly Journal of <strong>Mahatma</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong> <strong>Antarrashtriya</strong><strong>Hindi</strong> <strong>Vishwavidyalaya</strong>Volume 4 Number 5 January-March 2010R.N.I. No. DELENG 11726/29/1/99-Tc© <strong>Mahatma</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong> <strong>Antarrashtriya</strong> <strong>Hindi</strong> <strong>Vishwavidyalaya</strong>No Material from this journal should be reproduced elsewhere withoutthe permission of the publishers.The publishers or the editors need not necessarily agree with theviews expressed in the contributions to the journal.Editor : <strong>Mamta</strong> <strong>Kalia</strong>Editorial Assistant : Madhu SaxenaEditorial Office :Regional Extention Centre (Distance Education)E-47/7, Ist Floor Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-IINew Delhi-110 020Phone : 09212741322Sale & Distribution Office :Publication Department,<strong>Mahatma</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong> <strong>Antarrashtriya</strong><strong>Hindi</strong> <strong>Vishwavidyalaya</strong>Post Manas Mandir, <strong>Gandhi</strong> Hills, Wardha-442001 (Maharashtra) IndiaSubscription Rates :Single Issue : Rs. 100/-Annual - Individual : Rs. 400/- Institutions : Rs. 600/-Overseas : Seamail : Single Issue : $ 20 Annual : $ 60Airmail : Single Issue : $ 25 Annual : $ 75Published By :<strong>Mahatma</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong> <strong>Antarrashtriya</strong> <strong>Hindi</strong> <strong>Vishwavidyalaya</strong>, WardhaAll enquiries regarding subscription should be directed to the<strong>Mahatma</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong> <strong>Antarrashtriya</strong> <strong>Hindi</strong> <strong>Vishwavidyalaya</strong>, WardhaCover : Awadhesh MishraPrinted at :Ruchika Printers, 10295, Lane No. 1West Gorakh Park, Shahdara, Delhi-110 0322 :: January-March 2010

L A N G U A G EDISCOURSEW R I T I N GJanuary-March 2010ContentsHeritage<strong>Mamta</strong> Jaishankar Prasad 7Puraskar Jaishankar Prasad 11Jaishankar Prasad: A partisan view Rajendra Prasad Pandey 21FocusPriya Saini Markandeya 25Short StoryBagugoshe Swadesh Deepak 47PoetryFalling Naresh Saxena 59Moods of Love Upendra Kumar 67DiscoursePremchand as a short story writer: Gopichand Narang 81Using irony as a technical DeviceJanuary-March 2010 :: 3

The Theatre arising from Devendra Raj Ankur 100within the StoryDalit Literature : Some Critical Issues Subhash Sharma 108Observations on Dharamvir Bharati’s Avirup Ghosh 118‘Suraj Ka Satvan Ghoda’History In <strong>Hindi</strong> Literature : Hitendra Patel 1241864-1930Language<strong>Hindi</strong>’s Place in the Universe Yutta Austin 138<strong>Hindi</strong> And Indian Studies In Spain Vijayakumaran 147now on internet at www.hindivishwa.com4 :: January-March 2010

Editor's Note<strong>Hindi</strong> has its own treasure-chest of classic writers. They are read and re-read, researched andreviewed, remembered and forgotten only to come up yet again. Time, the old gypsy man, anointsthem with the rare salve of timelessness. We go to them repeatedly for that vintage voyage ofexploration and discovery. Very often we are stunned by their simplicity of expression and complexityof thought.Jai Shankar Prasad is one of such authors who offers us a variety of literary forms– short story,novel, poetry, drama and criticism. He worked tirelessly on all these forms and evolved a world ofhis own art and craft. Prasad and Premchand were contemporaries but no two writers could bemore different. Prasad often picked up his content from history and let his imagination colour itwith romantic idealism. Premchand’s source of inspiration was the common man pitted against adehumanised socio-economic system. They respected their differences and showed no bitternesstowards each other. Prasad passed away in 1937 whereas Premchand died in 1936. They wereprolific writers and had their own brand of patriotism at heart. Prasad was younger to Premchandby nine years. His contribution to <strong>Hindi</strong> literature was noteworthy in spite of his untimely demise.‘Chhayavad’ movement found in him its best spokesman.We carry Prasad’s short stories and articles on Prasad and Premchand in this issue. SincePremchand wrote in <strong>Hindi</strong> as well as Urdu, Prof. Gopichand Narang was our apt choice for thestudy. Prof. Narang excels as an exponent of Urdu and <strong>Hindi</strong> criticism.Markandeya has been a very significant author of the late fifties’ nai kahani movement. He surpassedthe movement by creating a new troika in <strong>Hindi</strong>– Markandeya, Amarkant and Shekhar Joshi. Thethree were as different as original. Markandeya not only wrote but influenced future writing, suchwas his spell in the sixties and the seventies. He is struggling for life in the emergency ward ofRajiv <strong>Gandhi</strong> Cancer hospital in Delhi while we carry his famous short story ‘Priya Saini’ in thisissue.Swadesh Deepak is another wayward genius whose short story ‘Bagugoshe’ was much landed in<strong>Hindi</strong> when it first appeared in the monthly ‘Vagarth’ edited by Ravindra <strong>Kalia</strong>. We hope its sensitivityis communicated to you, albeit in translation by Eishita Siddharth. He lives at an unknown addressthese days.January-March 2010 :: 5

Dalit writing has emerged as a force to reckon with. Subhash Sharma traces its development inhis candid study Dalit Literature : Some critical issues.Naresh Saxena and Upendra Kumar are senior poets who bring their own energy and is insight intowhatever they write. Naresh can infuse new life into any ordinary subject whereas Upendra Kumarexplores love in an otherwise loveless situation.<strong>Hindi</strong> language is lending attraction to all India-lovers. Our mythology and movies have contributedmuch to its popularity. The articles included endorse the contention.Some of the fellow writers whom we lost in the past months are– Dr. Kunwar Pal Singh, DilipChitre, Asha Rani Vohra, Rama Singh, Rajendra Awasthi, Kalyanmal Lodha and Dina Nath Rai.We condole their loss and extend our sympathy to the bereaved families.6 :: January-March 2010

HeritageMAMTAJaishankar PrasadTranslatedP.C. JoshibyFrom her apartment in the Rohtas fortress, young <strong>Mamta</strong> watchedthe sharp and majestic movement of the river Sone. She wasa widow. Her youth surged like the turbulent waters of Sone.With anguish in her heart, storms in her mind and unceasingshowers in her eyes, <strong>Mamta</strong> found in the very affluence of herhome a bed of thorns. She was the only daughter of Churamani,minister of the King of Rohtas. She had everything. But she wasa widow– and is not a Hindu widow the most condemned andhelpless being in the world– so where was the end of her sorrow?Churamani quietly entered her apartment. There she sat forgetfulof her being while the waves of Sone rolled on with a musicof their own. She remained unaware of her father’s presence. Churamaniwas pained beyond measure. What would he not crave to dofor his daughter brought up in such affection? He left as quietlyas he had come. Such feelings welled up within him very oftenbut today he was more agitated than ever. His feet shook ashe retraced his steps.After a short interval he returned again to her. He was followedby ten attendants carrying something in big silver trays. The soundof the footsteps disturbed the quiet of the sanctum and <strong>Mamta</strong>turned to look. Churamani motioned to the attendants to putthe trays down. The attendants withdrew thereafter.“What is this, father?” <strong>Mamta</strong> asked.“For you, my daughter! A present!”Churamani said and removed the covering from the trays. AndJanuary-March 2010 :: 7

lo amidst the golden evening there spreadthe radiance of the uncovered gold.<strong>Mamta</strong> was startled.“So much of gold? Where did it comefrom?”“Silence! my dear, it is for you!”whispered Churamani.“So you accepted the enemy’s bribe?It is criminal, father it is ominous. Returnit! We are Brahmins. What shall we dowith so much gold?”“This ancient and feudal dynasty seemsto be nearing its end. Little girl, anydayShershah can annex Rohtas and I shallbe a minister no more. It is for then,my darling!”“O God! For the rainy day! Suchcaution! Such daring against thecommands of the Almighty! Father, willthere be none to give us alms? Won’tthere be a Hindu alive under the sunto give a morsel of food to a Brahmin?It is impossible! Return it. I am frightened.Its glitter is blinding!”“Stupid!” exclaimed Churamani andwent away.Next day Churamani watched thepalanquins entering the palace with atrembling heart. At last he could notrestrain himself. He asked for the coversto be removed from the palanquins atthe gates of the fortress. The Pathansgrowled.“It is an insult to the honour of theladies of the royal family.”Hot words were exchanged. Swordswere unsheathed and the Brahmin waskilled on the very spot. The King andthe Queen and the treasury– all fell intothe hands of the treacherous Shershah.Only <strong>Mamta</strong> escaped. From inside thepalanquins appeared Pathan soldiersarmed to the teeth and they capturedthe fortress. But no trace of <strong>Mamta</strong> wasto be found.To the north of Kashi the dilapidatedDharma Chakra Vihar had survived asa remnant of the glory of the Mauryaand Gupta kings. Its steeples weredamaged; the walls were covered bygrasses and shrubs– and the onetimesplendour of the Indian architecture wasbeing soothed by the moonlight of thescorching summer.Under the dark shade of the sameStupa— now in ruins— where the fivedisciples of Buddha were the firstrecipients of the sacred message ofenlightenment– there, in a hut a womanwas chanting the holy scripture in thelight of the lamp.“Those who worship me with singlemindeddevotion.....”All of a sudden her reading wasinterrupted. A fierce and dejected figurestood before her in the faint glow ofthe lamp. The woman got up in frightand rushed to shut the door.But the stranger muttered.“Mother! I want shelter.”“Who are you?” asked the woman.“I am a Moghul. Defeated by Sher8 :: January-March 2010

Shah in the battle of Chausa I seekprotection. I can’t find my way onwardsin this dreary night.”“From Sher Shah!” The woman wasbiting her lips.“Yes, mother.”“But you are equally brutal– the sameferocious thirst for blood and the samesavage expression is on your face. Soldier!There is no place in my hut– go andfind a roof elsewhere!”“My throat is choking. I have losttrace of my companions. My horse hascollapsed. I am tired, dead tired!” Heuttered these words and dropped downon the earth and the whole world seemedto be turning round before his eyes.The woman was dumb for a whileat this fresh calamity! Then she gavehim water to drink and life returnedon the Moghul’s face.She was thinking– “No alien deservesany sympathy! The cold-bloodedexecutioner of my father!!” Hatred,burning hatred hardened her heart.The Moghul burst aloud– “Mother,shall I go away?”The woman again became thoughtful.“.....I am a Brahmin girl. Am I notdutybound to offer shelter to any guestat the door! .....No.....Not to all.....Mysympathy is not for aliens.....But it isnot sympathy.....It is the call of duty.Then?”The Moghul got up with the supportof his sword. <strong>Mamta</strong> said, “No wonderyou may also turn out to be a traitor!Wait!”“Traitor! Hm. Then let me go! Temur’sdescendant will betray a woman! I willhave to go. Strange are the ways ofdestiny!”<strong>Mamta</strong> was speaking to herself. Thisis no fortress. But only a hut. Let himgrab it if he likes. I must not fail inmy duty. She went out and told theMoghul, “Go inside, O famished and fearstrickensoldier! Whoever you be, I giveyou shelter. I am a Brahmin girl. Evenif the whole world fails in its duty, Imust not!The Moghul saw that majestic facein the faint light of the moon and bowedto her in silent reverence. <strong>Mamta</strong>disappeared behind the adjoining walls.And the tired Moghul entered the hutand breathed a sigh of relief.In the morning from a chasm in thewall, <strong>Mamta</strong> saw hundreds of mountedsoldiers roaming about in the compound.She cursed herself for her folly.The stranger came out of the hutand said! “Mirza! I am here!!”And the whole place resounded witha happy clamour of voices. <strong>Mamta</strong> becamefear-stricken. The stranger said– “Whereis that woman? Trace her out?” <strong>Mamta</strong>became more vigilant and vanished withinthe Mrig Dao and remained there thewhole day. In the evening soldiers werepreparing to leave and <strong>Mamta</strong> heardthe stranger mounting his horse andsaying!January-March 2010 :: 9

“Mirza! I could give nothing to thatwoman. I found shelter in her hut whilein distress. Remember this spot and builda house for her.”And then they left.Years have elapsed since the battleat Chausa between the Moghuls andPathans. <strong>Mamta</strong> is now an old womanof seventy. One day she was lying inher hut. It was a cold winter morning.Her skeleton-like frame was shaking withcough. Some village women were presentto nurse her for <strong>Mamta</strong> had shared theweal and woe of everyone all her life.<strong>Mamta</strong> asked for water to drink anda woman offered it to her in a conchshell.And then suddenly a mountedsoldier was seen at the door of her hut.He was muttering to himself: “This mustbe the spot to which Mirza has referred.That old woman must be dead by now.Who will now tell me in which hut oneday Emperor Humayun had taken shelter?Forty seven years have passed sincethen!”<strong>Mamta</strong> heard it with suspense. Sheasked the woman sitting by her side“Call him!”The mounted soldier came towardsher. She said in faltering tones, “I don’tknow whether he was the Emperor himselfor an ordinary Moghul. But he stayedfor one night in this very hut. I heardhe had ordered to build a house forme. I remained inside all these yearsin the fear that my hut will be destroyed.God responded to my prayer. I leaveit now for you to build a house or apalace whatever you like. I go to myeternal resting-place.”The mounted soldier stood bewilderedwhile the old woman breathed her last.A magnificent octagonal temple wascreated at that spot with the followinginscription:“Humayun, the Emperor of sevenlands stayed here for one night. His sonAkbar has constructed this toweringtemple in his memory.”But <strong>Mamta</strong>’s name was missing fromthat inscription.Jaishankar Prasad (1889-1937) was a great heralder of the romantic era inhindi literature. He wrote in almost every genre. ‘Kamayani’ is his most famousepic poem. His short stories were a blend of history and fiction. Prasad wrotenovels such as Kankal, Titli and Iravati. His plays Dhruvaswamini, Chandragupt,Skandgupt and Vishakh reflected his humanitarian and philosophical attitudeto life. He spent a major part of his life in Varanasi where he breathed his last.Dr Puranchandra Joshi, born 1928 in Almora, is an eminent sociologist andacademician. His areas of specilisation range from culture, literature, politicalideology to rural development, communication and economic growth. Some ofhis well known books are: Bhartiya Gram, Parivartan aur Vikas Ke SanskritikAyam, Azadi Ki Adhi Sadi, Avdharnaon Ka Sankat, <strong>Mahatma</strong> <strong>Gandhi</strong> Ki ArthikDrishti, Sanchar, Sanskriti Aur Vikas and Yadon Se Rachi Yatra. His memoirs inhindi quarterly ‘Tadbhav’ have been highly appreciated. He has received lifetime achievement award from Indian Social Science Council along with otherhonours elsewhere. He lives in New Delhi.10 :: January-March 2010

HeritagePURASKARJaishankar PrasadTranslatedP.C. JoshibyThe soliteary Ardra star! Dark and black clouds rolled and rumbledin the sky with the beat of celestial drums. The god of lightpeeped from a cloudless corner in the East as if to watch theroyal procession. A soft, fragrant odour rose from the earth inthe lap of the mountains. The gate of the town opened for theroyal elephant to appear towering among the crowds. The mightycongregation surged forward like an ocean of gaiety.The sky poured on the earth– tiny, sunlit drops like mallikaflowers. People hailed them as tokens of heavenly blessings.Chariots, elephants, mounted soldiers stood arrayed on theground. Visitors and spectators poured in. The royal elephantbent low and the King got down the stairs. Handsome virgins,and happy brides came to the fore carrying auspicious Kalashbedecked with fresh mango-buds, big trays of newly-plucked flowers,Kumkum and parched rice and sang melodious songs.A gentle smile played on the King’s face. The priest chantedhymns from the holy scriptures. Holding the golden handle ofthe plough, the King motioned to the lovely and robust pair ofbullocks to move.The blowing of trumpets and the showering of flowers by youngmaidens heralded the opening of this renowned festival of Kaushal.It was a unique event, the festival, when the King himselfacted the peasant for a day and worshipped Indra, Lord of cloudsand rains with pomp and grandeur. People of the town rejoicedJanuary-March 2010 :: 11

and young princes from other kingdomsjoined in this rejoicing.Arun, Prince of Magadh, watched thefestival from his chariot. His eyes werefixed on Madhulika while she helped theKing with seeds from the big tray thatshe carried in her hands. The plot ofland belonged to Madhulika and alsothe privilege of offering seeds for sowingwas hers. She was a virgin unexcelledin her charms in her lovely saffroncolouredattire. The wind sported withher and now she put her garments inorder and now her unruly locks. Womanlydignity and modesty gleamed in her smile.But despite her tenderness, she remainedunfaltering in her duty.People hailed the King as he ploughedthe field. But Prince Arun– he was standingunder the spell of the peasant girl. ‘Whatexquisite grace and innocent looks!’ hemurmured to himself in silent adoration.The main item of the festival wasover. The King presented Madhulika afew gold Mudras in a tray. It was thereward for her land and a token of King’sgenerosity. Madhulika touched the traywith her forehead in reverence andscattered them away thereafter in honourof the King. Her majestic looks left thespectators spell-bound.But the King was about to flare up,when Madhulika’s tender voice was heard:“Maharaj! I got this land from myforefathers. How can I sell it and accepta price in return?”Before the King could say anything,the old minister intervened:“Silly girl! What do you mean? Spurningthe royal present!” His tone wasindignant.“It’s worth four times your land. Andthen, don’t you know it is the customof Kaushal? From today you are underthe King’s protection. Thank your starsfor this good fortune, Madhulika!”“All subjects are under the King’sprotection”, Madhulika retorted in anexcited but firm voice. “Happily I offeredmy land to the King. But to sell it, no,it is not my right!”The king turned to the minister witha questioning look and the ministeranswered:“Maharaj! She is the only daughterof Singhmitra, the hero of the battleof Varanasi.” “Singhmitra!” the Kingexclaimed. “The saviour of Kaushal fromMagadh! And Madhulika is his daughter?”“Yes, Maharaj!” replied the minister.“What are the rules of this festival?”the King asked after a moment’sreflection.“The rules are simple, Maharaj”,replied the minister. “A good plot ofland is chosen for the festival and theowner is paid in the form of a gift bythe King. The owner himself takes careof the crop for a year and the landis known as King’s land.”The King could not come to a quickdecision. He kept quiet in perplexity.12 :: January-March 2010

The assembly dispersed meanwhile andthe King also returned to his mansion.But Madhulika was not to be seen inthe festival again. Absently she sat underthe shade of the tender green leavesof the towering Madhuk tree close tothe boundary of her land.The festival was over– the calm ofthe closing night reigned all around.Prince Arun had kept away from thecelebrations. He was restless in hissanctum. Sleep had vanished from hiseyes. A redness glowed in them likethat of the rosy dawn in the East. Notfar from his view was a dove standingon one foot in a cornice. Gently spreadingher wings, she yawned. Arun stood up.His horse was ready at the door andin a flash he galloped to the gates ofthe town. The sentries were in deep sleep.They started when the noise of hoofbeatsassailed their ears. But the youngprince shot forth like an arrow andvanished from sight. The robust stallionwas bubbling with vigour in the morningbreeze. Arun roamed hither and thitherand at last he reached the spot wherelay the troubled Madhulika asleep withher head resting on her palms!Like the tender Madhavi creeperdetached from the branches of a tree,she lay on the earth. Flowers were abloomand bees were tranquil and calm.Arun motioned to the horse to bequiet. And his eyes were steathily feastingupon the beauty of the sleeping youngdamsel. But the naughty cuckoo brokethe calm. It cried as if in reproof ofa strangers’ impertinence. Madhulikaopened her yes. She saw the figure ofan unknown young man before her.Hastily she gathered herself.“Young girl! You were in charge oflast day’s festival, isn’t it?” The strangerwas asking.“Festival? Yes, it was a festival”,Madhulika said and heaved a sigh.“Yesterday…..”“Why does the memory of yesterdayhaunt you, young man?” interruptedMadhulika. “Won’t you let me be in peace?”she added.“Since that day, Madhulika, I adoreyou. Your beauty has captured my heart.”“My beauty or the display of myplight that day?..... Ah, how cruel isman! Go your way, stranger and leaveme alone.”“Innocent girl! I am Prince of Magadh.I beseech your favour. My heart’s desiregushes out for you…..”“Young prince! You come from thepalaces and I am a peasant girl fromthe soil. Yesterday I lost even my land.I am unhappy. Does it behove you tolaugh at a girl’s plight?”“I will help you get back your landfrom the King of Kaushal.”“No. It is the custom of Kaushal.I don’t wish to break it whatever distressit may mean to me.”January-March 2010 :: 13

“What is the secret of your grief then?”“Ah, it is the secret of the humanheart. Young prince! Were the heartbound by laws, the prince of Magadhinstead of going to a princess wouldnot come to offend the dignity of apeasant girl!” Madhulika got up.The prince left with injured pride.His pearled crown gleamed in the tenderlight of the dawn. The horse gallopedaway with great speed. But hadn’tMadhulika hurt herself too? Her heartgnawed with sharp pain. With tearfuleyes she was watching the dust risingfrom the horse’s hoofs.Madhulika did not accept the King’soffer. Instead she chose a hard life–she would work in the fields of othersand after the days labour return to hersmall hut under the Madhuk tree. Shehad only coarse food to eat. Hard toilhad made her thin and weak but herdevotion imparted a radiance to hercountenance. Peasants held her in highesteem for to them she was an idealgirl. Days, weeks and years passed by.It was a cold winter night once andlightening flashed now and then in theovercast sky. The thatched roof ofMadhulika’s hut was leaking. She didn’thave enough covering to keep her warmand she was shivering in the biting cold.Her want today pained her more thanever. Man’s material needs are limited.But the sense of loss varies in intensityin tune with the stress of changingcircumstances. So was the case withMadhulika. She recalled the past– It wastwo, nay, three years back when onemorning under the same Madhuk treethe young prince had said…..”What? Yearning for those flatteringwords, she asked– what did he say? Thosewords were so very well imprinted inher storm-tossed mind. And yet in thatdreary night she dared not allow hisimage to appear in full bloom beforeher minds’ eye.She yearned to revive that preciousmoment. Her suffering had taxed herendurance to the breaking-point. Thepalaces of Magadh and their affluenceseemed to dance before her in the flashesof lightning in the sky. Like a child runningto and fro to catch the fire-fly on acloudy evening, Madhulika was, as itwere, chasing her dream! Cloudsthundered with a terrifying roar and afurious downpour began. Was it theprelude to a hail-storm? Madhulika wasstricken with fear for her hut. Suddenlythere was a noise outside.“Is there anyone to give shelter toa traveller?”Madhulika opened the door and inthe blaze of lightning she saw a manholding the reins of a horse. She wasstunned.“Prince Arun!” she exclaimed.“Madhulika!”There was a moment’s silence.Madhulika saw her dream come true.She was dumb.14 :: January-March 2010

“Oh, only if you had listened then…..”said Arun.Madhulika didn’t wish to give hima chance to comment on her sorry plight.She interrupted and asked:“And what brings you here in thiscondition?”“I rebelled and was expelled fromMagadh. I have come to Kaushal formy living.” Arun said with his head bentlow.Madhulika was laughing in the darkand remarked.“The rebel prince of Magadh! Guestof an unfortunate peasant girl! I welcomeyou, young prince, all the same to myhumble dwelling.”It was the grim silence and chill ofthe wintry night with the moon-lightfrost-stricken and the wind piercingthrough the bones and giving one creeps.Even then Arun and Madhulika talkedto each other sitting outside at the doorof a mountain-cave under the banyantree. There was unrestrained ardour inMadhulika’s voice while Arun wascautious and restrained in his speech.Madhulika asked:“Why do you keep your soldiers withyou when you yourself are so hardpressed?”“Madhulika! They are my companionswho will stand by me in life and death.How could I leave them?”“Why, we could toil and labour, youand I and earn our living. Now…..”Don’t be mistaken! I have faith inmy sinews. I will carve out a new Kingdom.Why should I lose heart?” Arun’s voicewas trembling as if he was afraid tosay freely what was in his mind.“A new Kingdom! What daring? Buthow? Tell me and let me also delightmy fancy with it”.“Not fancy, Madhulika! I will reallymake you the queen. Why do you worryover your lost land?”A moment passed and Madhulika’smind was running riot. Her deep-rootedyearning surged up in her heart. “YoungPrince,” she said. “I have pined andwaited for you all these years!”Arun could not check himself. Pressingher hands impertinently he asked:“Then was I mistaken? You reallyloved me then!”Madhulika was speechless. Her bosomswelled with rapture and excitement.Arun sensed what was passing throughher mind and like a quick-witted personhe burst out:“If you wish, I can risk my life andmake you the queen of Kaushal.Madhulika! I mean it. Would you seethe terror of my sword?”Madhulika trembled. She wished tosay ‘no’ but only exclaimed– “What!”“It is true, Madhulika. The King feelssorry for you since the festival and hewon’t have the heart to decline yourJanuary-March 2010 :: 15

equest. And I know for certain thatthe army-chief of Kaushal has gone faraway to crush the hordes of hilly bandits.”Madhulika was dazed by the proposaland a violent emotion seemed tooverpower her. “Why don’t you speak.”said Arun.“I will do whatever you say”,Madhulika said as if in a stupor.Half-asleep as if with half-open eyesthe King of Kaushal reclined on his goldenthrone. A woman attendant was swingingthe Chanwar over his head while anotherstood at some distance in obeisance withbetels and nuts in her hands.The sentry came and announced:“Maharaj! A woman has come with somerequest.”Opening his eyes, the King replied:A woman! Show her in.”The sentry led Madhulika to the King.She greeted him. The King fixed a steadygaze at her and said: “It looks I haveseen you somewhere.”“That was three year’s back, Maharaj,when my land was taken for the festival.”“Oh! All these years you passed inhardship and now you come for its price.Alright, you will be amply rewarded forit.”“No, Maharaj, I don’t want itspayment.”“Silly girl! Then what?”“About so much land from the barrenearth to the south of the fort– grantme that, Maharaj, and I will plough it.I have a partner now who will helpme with his men. The ground will haveto be levelled.”“Peasant girl!” replied the King. “Thatis waste-land. Moreover, it has strategicimportance because of its proximity tothe fort.”“Shall I return disappointed then,Maharaj?”“Singhmitra’s daughter! What can Ido? Your request…..”“Well, as you wish, Maharaj!”On second thought the King said–“Go and engage your labourers on thejob. I am directing the minister to issuea formal sanction.”Towards the south of the fort onthe bank of the rivulet, there was adense forest. Its habitual calm todaywas ruffled by the movements ofmultitudes of men. Roads were beingmade by clearing shrubs and bushesovergrown all over. The town was faraway and people hardly visited thisdeserted place. Even now no one botheredabout what was happening. For hadn’tthe King himself made a gift of the landto Madhulika?Standing in a thick bower Arun andMadhulika rapturously looked at eachother. Evening was drawing near andflocks of birds returning to their nestsnoticed a new stir and bustle in thatdreary forest and responded with a happyuproar.16 :: January-March 2010

Arun’s eyes glistened with exultation.The rays of the setting sun, softly playedon Madhulika’s flushed cheeks. Arun said:“Only a night more! In the morning youwill be crowned as the queen in Sravastiand though banished from Magadh, Iwill be the King of an independent state.”“Terrible! Arun, I am amazed at yourdaring. With a band of a hundred soldiersonly…..”“In the middle of the night will beginmy triumphant expedition.”“Then you are sure of your success.”“Yes, Madhulika! Spend your nightin the hut. From the morning the palacewill be your dwelling place.”Madhulika was happy. But she wasafraid for Arun. She would get excitedand scared like a child. Suddenly Arunsaid:“It is pitch dark now. You have togo a long way and I have to finaliseour plans. Adieu for the night,Madhulika!”Madhulika got up. Struggling her waythrough thorny bushes, she walkedtowards her hut in the dark.The road was dark and dismal, gloombegan pervading Madhulika’s heart too.Some unknown force seemed to besqueezing out her heart’s sweetness andher dear dream was vanishing in thegloom. A fear grew in her soul for Arun–“Well, if he fails in his venture, then?”All of a sudden she asked herself– “Whyshould he win? Why should the Srawastifort pass into the hands of a foreigner?Ah, his victory…..!..... But the King wasproud of her, – of Singhmitra’s daughter.Singhmitra, the saviour of Kaushal! Andhis daughter, a traitor? No. No.“Madhulika”, “Madhulika”, she heard herfather calling her in the dark. Shescreamed like a hysterical woman andlost her way.It was nearing midnight but Madhulikafailed to reach her hut. She was movingonwards aimlessly– she was in a turmoil.In her mind now the image of her fatherand now that of Prince Arun would flashalternately. A light was visible beforeher. She stood in the middle of the road.A hundred soldiers were marching withtorches in their hands at the head ofwhom walked a middle-aged, bravelookingsoldier! He held the reins ofthe horse in his left hand and in hisright a naked sword. The detachmentadvanced with firm steady steps. ButMadhulika barred their way. The chiefof the detachment came near. Even thenshe stood fixed to the ground like astatue. The soldier stopped his horseand said– “Who is there?” There wasno reply. The other mounted soldierthundered: “Who are you? Speak out!”He was the army chief of Kaushal. Thewoman shouted as if in a fit of insanity.“Arrest me! Kill me! My crime isso grave.”The army chief laughed: “Madwoman!”January-March 2010 :: 17

“Ah, If I were mad, I wouldn’t haveany agony. Arrest me and take me tothe King!”“What’s the matter? Speak out.”“The Sravasti-fort will be capturedby bandits within a few hours. Theywill launch their attack from the southernrivulet.”The army-chief was dumb-founded.“What do you say?”“What I say is true. Hurry up.”The army-chief ordered a hundredsoldiers to march towards the rivulet.And he moved toward the fort with twentysoldiers. Madhulika was tied to a mountedsoldier.The fort of Sravasti— the centre ofthe Kaushal kingdom— is plunged as itwere in the reminiscences of its gloriouspast. Several dynasties have usurped anumber of its provinces. It has onlya few villages now to call its own.Nevertheless, it carries the halo of itspast glory and that is what rouses thejealousy of others.The sentries of the fort were amazedto find the mounted soldiers coming.They recognized the army chief andopened the gate. The army-chief got downfrom the horse-back and asked– Agnisen!How many soldiers are there in the fort?”“Two hundred” was the reply.“Collect them without any noise.March with a hundred toward the south–let there be no stir and no light.”The army-chief turned towardsMadhulika. She was released and takento the King. The King was about to retirefor the night when he saw the armychiefand Madhulika and was restless.The army-chief said: “I had to comebecause of this woman!”The King paused for a moment andsaid:“Singhmitra’s daughter! What bringsyou here again? Any obstacle to yourplan? Senapati! I have granted her theland near the southern rivulet. Do youwant to say anything about that?”“Maharaj”, replied the army-chief,“Some secret enemy has planned to attackand capture the fort from that side.”The King looked at Madhulika. Shewas trembling and sinking in selfcontemptand shame. He asked: “Is thattrue, Madhulika?”“Yes” was the reply.The King told the army-chief “Collectthe soldiers and I will follow.”After the army-chief had departed,the King said: “Singhmitra’s daughter!You have saved Kaushal a second time.You deserve a reward again. Well, youwait here. Let me first take care of thebandits.”Arun was caught in his subversiveadventure and the fort was glowing inthe light of the torches. The crowdshouted in great ovation. Joy pervadedall around. The Sravasti fort had been18 :: January-March 2010

saved from bandits. There was joy andgaiety all over and the meeting groundechoed with the clamour of multitudesof people. Seeing the prisoner Arun, therewas a furious uproar from the crowd.“Death to the traitor”. The Kingordered in agreement– “Death to thetraitor!”Madhulika was called. She came andstood like a tattered woman. The Kingsaid: “Madhulika, you will get whateveryou desire.” She was quiet.The King said again: “I give you allof my personal land.”Madhulika threw a glance at thecaptive Arun, and said: “I want nothing”.Arun laughed.The King said: “No, you must havesomething. Come, tell me what you want?”“Ah, what is there for me now!” shemurmured to herself.After a moment’s pause she spoke aloud:“Then reward me also with death!” Andstood by the side of the captive Arun.January-March 2010 :: 19

HeritageJAISHANKAR PRASAD:A PARTISAN VIEWRajendra Prasad PandeyWe have had a very few writers and poets in <strong>Hindi</strong> literaturewho have made their significant contribution to mulitple areasof literature. Jaishankar Prasad is one of them, a poet, short storywriter, novelist, critic and playwright, all rolled into one. He isequally competent in writing novels and short stories. A multidimensional creator and artist in the true sense! We have a fewother such names like Bhartendu Harishchandra, Muktibodh andAgyey. Jaishankar Prasad has made a distinct mark in <strong>Hindi</strong> poetryby his amazing images, imagination and aestheticism with romanceand passion. His poetic-diction is unique in itself.Jaishankar Prasad has made his contribution in visualizing thesocial reality in the form of poetry; combining the real and theunreal, worldly and other worldly into a fabric of compassionand humanism. He has often been misread by many scholars asa poet of depression and escape. <strong>Hindi</strong> criticism has made a consciousattempt in marginalizing such poets and authors whose writingsare not very vocal and loud in articulating and propagating ideasand reality in a profound fashion.The poetry of Jaishankar Prasad also falls in this category.It is very unfortunate that Jaishankar Prasad and Suryakant TripathiNirala; Agyeya and Muktibodh are poised and presented in contrastand as opposed to each other. What we should have done wasto analyse and assert the contribution and works of the respectivepoets in their own sphere with their own distinctive features anduniqueness.20 :: January-March 2010

Here we will be discussing some ofthe unique features of the writings ofJaishankar Prasad. Prasad is creditedto have propounded the <strong>Hindi</strong> romanticpoetic movement called ‘Chhayavad’. Thecollection of poetry published in 1918‘Jharna’ by Jaishankar Prasad is rightlycredited as new poetry full of freshnessof language, and diction, voice of a changein perspective and presentation. Thishappened for the first-time in the historyof <strong>Hindi</strong> poetry that nature was so closeto man; moreover the treatment wasalso different. Nature was not treatedas a stimulating factor for love andpassion but in ‘Chhayavadi’ poetry naturewas presented in a live form; as a livingbeing. ‘Jharna’ is symbolic of expressionof revolt against social and poeticconventions. By crediting ‘Jharna’ asa pioneer of true romanic poeticmovement in <strong>Hindi</strong> poetry, called‘Chhayavad’; I am not underestimatingthe importance of poem ‘Uchchwas’ bySumitranandan Pant which was writtenin 1917. Of course, this poem came outwith a new and fresh poetic diction andidiom. There was reflection of ‘first-ray’–‘Pratham Rashmi’. This expression hasmany connotations of meaning at variouslevels in Indian and world perspective.In spite of this fact ‘Jharna’ is a morecohesive and concrete reflection ofromanticism in <strong>Hindi</strong>.Here we must remind ourselves that<strong>Hindi</strong> romantic poetry ‘Chhayavad’ hasmany components of modernity unlikeEnglish romantic poetry. We can veryeasily notice the contemporary freedomstruggle of India as an under currentin Chhayavadi <strong>Hindi</strong> poetry. <strong>Hindi</strong>Chhayavadi poetry is spread over twodecades broadly 1918-1936. Intrestinglythis may be traced from ‘Jharna’ to‘Kamayani’ (1936). Prasad may be saidto be the true representative ofChhayavadi poetry for many reasons,the Chhayavadi poetry with earnestnessand distinctive features is present inthe writings and collections of Prasad.The other prominent Chhayavadi poetsNirala, Pant and Mahadevi could surviveeven after Chhayavadi poetic movementwas over and they chose their differentpaths. Nirala was inclined towards morerealistic and socially committed poetrywhereas Pant embraced progressivemovement and thereafter adoptedAurobindo philosophy; Mahadevi alsocould not add anything new in poetrybeyond ‘Kamayani’ era.Ranging between Jharna andKamayani, there comes ‘Ansoo’, ‘Lahar’,‘Kanan Kusum’, ‘Karunalaya’ etc.Jaishankar Prasad is significant for hisnew images, fresh and innovative poeticdiction, wonderful imagination, lucidityof language and stylistic approach,aesthetic sense and so on at the levelof form but he is more significant forhis vision and understanding of humanrelations, treatment of love, probleematizingand analylizing humansufferings in a broader perspective.Prasad chose to relook into the pastand mythology of India and by visitingJanuary-March 2010 :: 21

and revisiting Indian history, he foundsome solutions to the problems ofcontemporary India; these solutions weremore visibly and prominently reflectedin his plays like ‘Dhruvaswamini’,Chandragupta snd Skandgupta. I willtake this aspect later on. Here I wouldlike to mention that ‘Kamayani’ is sucha great attempt made by JaishankarPrasad that it could become a classicalwork of all time and all places becauseof its holistic approach and understandingmankind in totality. The broad rangeof problematics gives ‘Kamayani’ a statusof great modern Indian epic. Startingfrom ‘Chinta’ and ending with ‘Anand’Prasad mentions different dimensions ofHuman psychology. Based onmythological elements of Manu andShraddha or Kamayani and the terrificdisaster of floods; this is infact the workof creation and evolution of modern manwith all his goodness and evil.‘Kamayani’ has invited great attentionof <strong>Hindi</strong> critics. Many readings andattempts of appropriation, denouncementhave been made. Kamayani could notreceive a sufficient amount ofappreciation of the great critic of thetime Ram Chandra Shukla. Though heappreciates the epicality andpresentation, language and diction ofKamayani, he was not convinced withthe focus on Ida, representing rationalityand wisdom, in comparison to Shraddha,representing heart i.e., feelings andemotions. Referring to the line ‘SIRCHADHI RAHI PAYA NA HRIDAY’ (Shewas carried away by mind and had noheart (emotions), it was referred to Idaas if Prasad was in favour of emotionor say Shradhha who has had emotionsand feelings embodied with her. Shuklaji suggests that it could have equallybeen said that (Shradha) ‘RAS PAGI RAHIPAYEENA BUDDHI’ (She was embodiedwith feelings and passions and had norationality). The fact lies in this perceptionthat ‘Chhayavadi’ poets have leaningstowards emotions and passions; they wereall carried away by RASATMIKA VRITTI(the emotive instinct).Of course, there, can be no denialof the fact that Chhayavadi poetry isexpression of feelings, emotions, passionand love in a form of lucid languageand refined diction. Prasad being arepresentative of Chhayavadi poetry (hemay be so, because of his poeticdistinction), has expressed so many thingsin his poetry which refer to these features.His musicality of language, fascinatingimages, sensuousness and passionateexpression in an amazing fashion makehis poetry lasting and unique. ‘Kamayani’is a great manifestation of modernity.Here is a man (Manu) who has lost allhis belongings, he is the only survivorof his generation and the entire SaraswatPradesh. He is sinking into worries oflife, lamenting upon loss of what he had;an immortal world! the world which wasassociated with all the wealth andpleasure, may be sad like ‘Eden Garden’.His encounter with Kamayani is a hopeof life and opens an area of creation22 :: January-March 2010

and love. Beginning from worry andending into ‘Anand’ (The absolutepleasure) is the horizon of the epic. Thisin fact is a process and search ofphilosophy of life. The world view ofthe poet is very clear– ‘SHAKTI KEVIDYUTKAN JO VYAST, VIKAL BIKHAREHON HO NIRUPAY, SAMANVAY UNKAKARE SAMAST VIJAYINI MANAWATABAN JAAY’ (By synthesizing the sparksof energy, wherever they are, all together,we can make the mankind victorious,that can win over all the evils andobstacles).This, indeed, is a great vision, a greatdesire for the betterment of human beings.This can never be a desire of a pessimistpoet (as he is often described). Of course,there are elements of pessimism inPrasad’s poetry, but a substantive amountis of faith, hope and love towards lifeand human values. One of the verysignificant studies of Jaishankar Prasadhas been made by eminent poetMuktibodh in his critical work‘KAMAYANI : EK PUNARVICHAR’.Muktibodh described his poetry as afailure in totality. A great fantasy. Awork which has been presented in emotiveform but has had reality within it(BHAVVADI SHILP MEINYATHARTHVADI RACHNA). The entirediscourse made by Muktibodh is basedon Marxist paradigm. To some extenthis evaluation can be accepted butKamayani is much more than a fantasyand failure of feudalism (Manu and hisempire, divinity). This cannot be simplyviewed in terms of stages of evolutionof human history as has been narratedby Muktibodh. Kamayani needs a relookto be given the parameters of its own.It is such a great work which deniesto be evaluated on the canons of eitherIndian or Western literary theories ofa particular kind, in fact a number ofcanons are required for evaluation of‘Kamayani’ in particular and JaishankarPrasad in general. Like his images andlanguage, the characteristics of his poetryare also very complex; having a numberof layers. His poetry is difficult, to reveal.The meanings can perhaps never beexplored. The statement of T.S. Eliot‘Meaning is a continuous process’ maybe applied in case of poetry of JaishankarPrasad.In contrast, Prasad is much moreopen and suggestive in his prose. Hisexpression and depiction of reality ismore visible in his novel ‘KANKAL’. Hisloudness can more easily be heard inhis plays ‘DHRUVASWAMINI’,CHANDRAGUPTA, VISHAKH,SKANDGUPTA and others. Thecontemporariety of Prasad can beunderstood by the views and problemsraised in these plays. The issues whichhe has raised are quite relevant eventoday. He was in true sense a greatvisionary, forward looking artist. Theproblem of women’s liberation, love andstruggle for independence (inChandragupta), tracing the testimony andevidences from myths and theUpnishadas, he proposes clear andJanuary-March 2010 :: 23

categorical solutions to the problems.His women characters are not very ‘overbearing’ but in spite of their lyricality,they express their opinions as well.On the whole Jaishankar Prasad isa great achiever of <strong>Hindi</strong> literature.His contributions were immense andlasting for times to come and forcenturies.Dr Rajendra Prasad Pandey is reader in school of translation, studiesand training at IGNOU, New Delhi. He has written on several <strong>Hindi</strong>authors in English.24 :: January-March 2010

FocusPRIYA SAINIMarkandeyaTranslatedJai RatanbyI have kept it to myself far too long and can’t bear it any longer.I must tell you about my woes, for it’s getting too much for me.Decrepit with age and undermined by disease, this body of mineis now incapable of carrying its burden. It’s a wonder that I havecarried on for so long; my body should have broken down muchearlier. Its sap of life was gone the very moment I deserted Priyawhile she was in the throes of childbirth. Since then I have beenfeeling as if someone has plunged a knife in my liver, leaving itflaring with pain. The pain does not subside even for a minute.Whenever I am confronted ‘With an unsavory situation I feel asif my life is going to burst at the seams. That’s why I keep peepinginto people’s sad and troubled eyes like a mad man. I have seenmy sense of duty and pride dying a lingering death and believeme, I have carried them over my shoulders like a corpse, Withoutany compunction, to be thrown into some blind gorge. To my chagrin,these seemed to have drawn a wedge between me and Priya, bringingus to the brink of disaster. Otherwise what was that something thatshook me to my very core? When boys and girls live and growup together they are bound to be drawn towards one another; there,is nothing unusual about it. It is only a question of opportunityand fate, which people are prone to magnify out of all proportions.But for these, there was not even a remote possibility of my andPriya’s coming together. We had not known each other before, norhad we any common contacts. We had stood there looking at eachother. After a minute’s awkward silence she must have realized theJanuary-March 2010 :: 25

absurdity of the situation, for she lookedsideways and said, “Are you looking forsomeone?”“No one in particular. Maybe you!”“Me?” She shot the question at meand laughed. I almost quaked under hergaze I had spoken to her ‘With a greatshow of bravado, hoping that my brazenreply would make her blush. But keepinga straight face, she just stepped aside inthe narrow passage, making way for meto come in. Her behavior was matterof-factas if I was no stranger to her.As I sat down in her room, I decidedto take a firm grip over the situation.“Do you live here with your father?”I asked.“Yes,” she said, sitting down in frontof me. “But why do you want to know;If you could state the purpose of yourvisit it may help.”“I’m a student of Psychology. I’m doingresearch on the manifestation of fear inchanging situations. I’ve drawn up aquestionnaire on the basis of which I’minterviewing young men and women.” Whiletalking with her, I threw guarded lookstowards the door, expecting that someonemay turn up and demand to know witha lurking suspicion as to what was goingon here.“Take it easy,” Priya said with an effusivesmile.” There’s no one here. You wouldn’thave found me here either but for thefact that my school is closed today. It’sjust a coincidence that we happen to meet.Since July I’m teaching dance in a girls’school. Mother died ten years ago. Fatheris working with the Akashvani as an artiston contract basis for the last thirty years.I’ve a younger brother studying in college.This room has been in our occupationfor the last two generations. My grandfatherran away from his village and tookup a darwan’s job with a seth who gaveus this room and a long mezzanine runningalong the whole length of this room andending up in the room in front, The sethhad the windows of the other room closedand improvised a kitchen and a bathroomfor us. This room though small is anywaybig enough for me to spread a cot init. After mother’s death I’ve been livingin this small room. During the rainy seasonand particularly in summer its windows...”Priya suddenly fell silent, showing signsof restlessness. “You know what I mean,”she continued. “I’m explaining the situationto you.”“You were going to tell me somethingabout the window,” I said as if touchingon her sore spot and intently watchedher face.Priya did not betray any signs of embarrassment.“The thing is that if I keepthe door of the mezzanine closed in summerit becomes like a box,” she said withoutfaltering. “Then I put out the lights andopen the window and get a feeling asif I’m sleeping in the open. Since we liveon the upper storey, it’s peaceful and quietover here. You can see how uncongenialthis locality looks. The railway line cutsacross the road which is swarming withtrucks, buses and cars day and night. And26 :: January-March 2010

then there are the thelwalas, coolies andfactory workers raising a din all the time.All sorts of people live here. Do you seethat big gate over there? It’s the millgate. There is trouble at the mill almostevery day- sometimes marked by violence,even police firing.”She paused for breath. I thought shewas doing this as a cover-up to her thoughts,especially about the window. The way shehad opened out to me seemed to signifyan inner contradiction, which did not accordwith the impression that I had formedabout her personality. In spite of the broadhints thrown to me I was cautious enoughnot to jump to any unwarranted conclusion,which would be like retracing yoursteps when you were almost within sightof your destination.“This is hardly the place for the pursuitof dance and music,” I said. “The noisysurroundings must be a great distraction.”“You’re right in a way,” she said. “Butwe cultivate these arts as professionals,in keeping with our tradition. Father isa man of saintly disposition. In other words,he considers art as the highest expressionof all that is noble in man. And man,according to him, is one who is poor,defeated and full of suffering.” Priyahesitated, fearing that I was not gettingat her real meaning, and decided to bemore explicit. “Noise and din, povertyand unhappiness— if you exclude thesethings what else is left in my poor country?This house is therefore no bar to the pursuitof our vocation. We don’t go after thatsort of art which culminates in divinemiracles. We live on a different plane,not divorced from our normal life. Fatherhas not taught me dancing as an infliction.He knows that I have a liking for it andhe has tried to put me on my feet.”Priya paused for an instant and I feltas if a dream had abruptly snapped midwaywhich on waking up whetted the appetiteall the more for it to have continued.I got up. It was clear that Priya wasfeeling apologetic. She feared that she hadbored me with her talk. “Forgive me, Iseem to have talked a lot of rot. I startedoff all right and then drifted into irrelevances.”“I’m not surprised. You’re an artiste,after all. Apart from basic human propensities,an artiste has another dimensionto his personality, based on an agglomerationof acquired talents which are thefirst to disintegrate under the stress andstrain of life.” I swayed my head, lookingvery thoughtful and sad.“Yes, the stress and strain of life...”she echoed my words and her face turnedred with embarrassment. We stood therewithout looking at each other. It lookedso odd, like something out of the blue.I could not lift my feet while Priya stoodbefore me wordless. Then the tap hissedand water started dripping from it.“It’s 3’o clock!” Priya suddenly said.“So the tap is on.”“We get water only in short spellsand store it in vessels for use.” She againfell silent as if she had said all that thereJanuary-March 2010 :: 27

was to be said. I felt as if I had foundmy feet. “I’ll go;’ I said looking grave.She had only a small gesture to make- an imperceptible nod of the head,signifying that I could go. But she stoodthere mute, as if the words that she wantedto utter were caught in a whirlpool. Herunsaid words, “How can I ask you togo,” rang in my ears. “I’ll come someother day,” I said and turned to go.“No, no, no,” pat came Priya’s reply.“You won’t find me here. I’m away mostof the day, teaching in the school. Pleaselet me have your address. I’ll send youword”Now we were both on firm ground.Taking my visiting card from my pocketI handed it to Priya. Without as muchas glancing at it she folded her handsin farewell. Coming to the edge of theroof she stood there watching me climbingdown the stairs.“I’ll wait for your message,” I saidfrom below.x x x x xA doubt assails my mind. You mustbe thinking that I’m doling out fiction.I would urge upon you not to take itas the fabrication of my imagination.Otherwise we would get involved in therigmarole of what is true and what isimaginary, what is real and what is tinsel.You may lay the charge against me thatthe whole thing sounds cinematic. Anunknown young student enters the houseof an unknown young girl without anyintroduction. And strangely enough, thatgirl starts talking to him without anyinhibition. She does not stop at that. Sheeven thinks of writing to him. To tell thetruth, I discern many false notes in thewhole episode and today when I look backon the whole thing I wonder how it allcame to pass. But at that time I wasobsessed with only one thought - to lookforward to Priya’s message. Would sheoblige? May be, maybe, not. No, no, Imust hear from her.In the next few days when I saw thepostman my mind was filled with a strangeexpectancy bordering on trepidation. Butwhen no letter came I felt utterly dejected.I had stopped going to the library andspent my time at home, organizing thematter that I had received in responseto my questionnaire. One day an invitationcard arrived in my mail and I openedthe envelope disinterestedly. It was apersonal invitation from the most prominentgirls’ school, situated only a shortdistance from my house. Why personal?I started studying the card. The star itemon the programme was a dance by PriyaSaini— ‘The Quest for Man’. Below it wasthe Principal’s name and in the cornerin very small letters was scribbled PriyaSaini’s name. There was also another smallcard - an invitation to dinner after theperformance. Everything became clear tome at the first glance and I eagerly startedlooking forward to that evening.x x x x xI vividly remember it. It was the 5thof February. The winter was on the way28 :: January-March 2010

out and the weather had become lively.I reached the main gate of the schoolpunctually at seven. Not that the placewas unfamiliar to me. I used to pass bythis side almost every day and saw theNepalese gate-keeper sitting on his highstool, dozing.It came as a bit of a disappointmentto me to not find a crowd there, noteven girls who are supposed to form thebulk of the audience, it being a girls’ school.The darwan told me that the main functionwas over in the afternoon. Now there wouldbe a dance by the dance teacher of theschool for the exclusive benefit of theelite of the town including the managementof the school. The students of the schoolhad been debarred from seeing the dancefor it was considered to be rather boldfor them. I was shown into the enclosuremeant for VIP’s. The lights started fadingand soon the auditorium was plunged indarkness.Misfortune overtook me at the veryfirst step. I had never thought that thepath of love was strewn with so manytroubles. On the one hand I was eagerto meet Priya after the performance andon the other I was feeling subdued andout of place in a girls’ school which hada proud tradition of conservatism. Howwould Priya react to the situation? Maybe,the right thing would be to slip awayafter the performance, instead of feelingput out in the midst of prying, inquisitiveeyes. My reverie broke with the tinklingof the second bell. I saw the curtain risingagainst the cyclorama comprising thedistant backdrop of street lamps silhouettedagainst a gray sky. The whole scenecreated an illusion of the stage extendingitself onto the audience except in the leftcorner where stood a house with a windowopen on the second storey and beyondit a chimney belching smoke. First I couldn’tmake out anything and remained engrossedin a tune emanating from a flute. ThenI saw a shadow-play of pedestrians andprocessions emerging on the road. Andlo, there was what looked like a nakedfigure framed in the window of the upperstorey, trying to adjust her clothes. Itwas only then that I realized the significanceof the whole setting. It was Priya’sown mezzanine window, Then came acommentary over the mike in an easy,flowing language, ‘The Quest for Man’ wasPriya’s own creation: a blend of manydance styles, which according to herinnovations broke loose from classical tradition.The purpose of dancing is notdetermined by pre-conceived regulatoryprinciples. The dancers often associatethemselves with the dance-form and beingmechanical in their actions and being devoidof feelings they are unable to interpretthe inherent cosmic significance of thedance. As it is, dance is an independentmedium of self-expression in which onecan delineate one’s feelings from the verydepth of one’s being,Here the meaning of ‘The Quest forMan’ was not a search for any particularindividual who had disappeared from thescene. The searcher may not even be awareof what she was in quest of. The objectJanuary-March 2010 :: 29

of search may be right in front of thedanseuse or even lodged in her heart andshe may be blissfully unaware of its identity.Soon a rosy light gently rippled acrossthe stage to the soft strains of the jaltarangand from behind that light emerged thescantily clad figure of Priya.For the next hour and a half, peoplewatched her dance with bated breath. Suchsharp but rhythmic movements, lyricalin their conception seemed to be beyondthe pale of imagination. People watchedher spell-bound and Priya would standstatuesque gazing at the audience infascination. In its totality of impressionthe performance was unique which wordscannot describe adequately. But I cannothelp saying that at the end of the perfomancemy mental condition had radically changed.Somewhere deep inside my attitude towardsPriya had hardened. When the lights cameon, I scrutinized the audience. That senseof excitement and hesitation had vanishedfrom my mind. I saw some women comingtowards me, among them a gray-hairedwoman, who was introduced to me asthe Principal of the school. A faint smilelurked round her lips. “Won’t you liketo go and congratulate Priya?” she said.But before I could guess what was at theback of her mind, two girls !ed me tothe back of the stage where I found Priyasurrounded by a large number of her femaleadmirers and friends. They went away asthey saw me approaching. Joining togetherher palms she smiled with the simplicityof a child. I knew she wouldn’t ask meanything about her dance, “It was amagnificent performance,” I said.“Don’t be so laudatory. People willlaugh. As you must have observed nomen had been invited except membersof the managing committee and theirfamilies. The Principal though strict is quitemodern in her outlook.” Priya turnedaround to accept someone’s greetings.“I think your Principal suspects there’smore to it than meets the eye,” I said.“She knows we are friends. What’s wrongabout it?” There was an edge to Priya’svoice though it did not lack warmth.We were talking freely as if we hadbeen friends for years. We moved to thedining table. Profuse in their praise, peoplegathered round Priya. But she did notneglect me. On one or two occasions, sheeven held my hand as if absent-mindedlyand then let go of it immediately.I found myself in a quandary. Notthat I was not enjoying myself. But thewhole atmosphere seemed to be againstmy grain. Everyone cast curious looksat me, thinking I was Priya’s lover.We were still at the dining table whenthe Principal swiftly came to us and placingher hand on Priya’s shoulder said, “Priya,you must look after your guest and yes,”she leaned over, “You may stay back andtake the staff car on the second trip. I’lltell the driver.”After the dinner was over, many gjrlsof Priya’s age gathered around me andstarred badgering me. Priya, I found haddiscreetly slipped away. Evidently, the girlsthought I was Priya’s would-be husband.30 :: January-March 2010

“You must be careful,” one of themsaid. “She’s no ordinary bird. There arescores of eyes set upon her.”“You must do some physical exercise,”another said. “Priya can make twentyfivespins on her heels without losing herbreath.”The gjrls cut all sorts of jokes withme which rattled me no end, especiallybecause the jokes were lacking in sophistication.The sound of a car horn cutshort our meeting. The girls scattered asthey saw Priya coming towards us, holdingbouquets of flowers. “Let’s walk up tothe road,” she said. “The car should behere any moment.” I walked by her sidein silence.“Why are you looking so glum?”’shesaid turning to me, “By the way, howare you getting on with your research?”From her easy manners I could guessthat she had extricated herself from thewhiripool in which she had found herselfa short while ago. But I was still havinga hard time of it. Priya’s talent and theample recognition of it at the hands ofthe elite of the town made me feel smallbefore her.“I seem to have come to a dead end,”I said in a listless voice. I had to saysomething just to keep the pretense ofgood manners. My ordeal was cut shortby the tooting of the car horn.The driver opened the door for us.I stood aside for Priya to get in and thenI sat down in the back seat, a little apartfrom her. What would have ordinarily lookedcommonplace suddenly assumed a newsignificance. I was overwhelmed by hersmell and the casual touch of her body.“I’ll see you home,” she said. “Tellthe driver the way to your house.”After the car had taken one turningI asked the driver to stop.“So soon?” Priya looked at me surprised.“That’s where I live. I can see thesouthern wall of your college from here.’’Priya got down and looked around.“My rooms are upstairs. On the secondfloor.”‘Who else. . ‘?”“I live alone.” I invited her to comeup.“Yes, I’ll come up for a minute. Justto have a look.”Walking ahead of me she climbed upthe stairs. I unlocked my house. She steppedin, cast a cursory glance at the courtyardand then entering my room sat down ina chair. Again a gulf seemed to yawnbetween us. I found myself in a predicament,not knowing how to set the ballrolling. I gingerly sat down in a chairin front of her, but I felt like pluckingmy hair and running down screaming. Igot up and her eyebrows went up. “Whereare you going? Do sit down.” I sat downagain. She looked up at me. She had notcompletely cleaned the make-up from herface and her eyes were looking like slicesof mango on her blotchy face. Her eyesafter rolling like the fathomless sea rico-January-March 2010 :: 31

cheted against the door and grazing pastthe window came to rest on the smalltable in front.“You live very close to our school.”I was silent.“I’ll drop in again sometime.” She raisedher head.I was still silent.“Don’t you like me to visit you?” Shelooked at me. There was pain writ largeon my face.“What’s happened to you?” She drewcloser to me. I shook my head, sayingthat there was nothing the matter withme and got up again. Wordlessly, we walkedup to the car, standing on the road. Iopened the door, helping her into thecar.“You want me to go alone?” she said.“At this hour of the night?”I looked at my watch. It was nearingeleven-thirty. I got in and sat down byher side and the car proceeded towardsher house. This time she looked very livelyand would not cease talking. Unknowingly,her hand would fall upon mine and shemade no effort to withdraw it. Once Iheld her hand and she let it remain inmy grip. Then she edged closer to meand I could feel that her body was tremblingwith excitement. It was an awkward momentfor me, the infant-like self-confidence thathad taken birth in me was throwing aboutits arms and legs, making its presencefelt. Priya had suddenly leaned forwardand her face had momentarily disappearedbehind her long hair. I put my left handround her waist and as I tried to drawher to me the car blew its horn and stopped.I tried to remove my hand. “Sit still,”she said and asked the driver to go andring the doorbell.As the driver got down from the carshe sat up straight and the next momentI found her between my arms. After aquick embrace and a kiss she hurriedlygot down from the car. All this had happenedswiftly, like a flash of lightning or likea spurt of pain across the heart, leavingme aghast.I still remember her passionatelyquivering voice, “Won’t you get down?”But as I leaned forward towards the doorshe seemed to have realized the delicacyof the situation and asked me to remainseated. She pressed my hand between herhands and swiftly climbed up the stairs.When the car started I saw her shadowyfigure leaning through the upstairs window.For a fleeting moment it reminded meof the setting of the ‘The Quest for Man’.Mywhole world was transformed where withthe passage of each moment I found myselfdrifting towards a close preserve of minewhere I lived with Priya. I was so muchtaken up with my own thoughts that Iwas not even conscious as to when Ireached home and entered my room. Fora fleeting moment my attention was rivetedto the chair in which Priya had sat ashort while ago. I changed and got intobed.To tell the truth, I had found these32 :: January-March 2010

events most bewildering for they had beenbeyond the periphery of my experience.Otherwise they could have opened newvistas of happiness for me. The glimpsethat I had got of Priya’s art and herpersonality were so exhilarating and themanner in which I had been introducedto that new world of hers so captivatingthat now after such a lapse of time ithas become difficult for me to believethat all this had really happened.Your expectations must have soaredhigh. But before your imagination runsriot, let me warn you that if you arehoping to witness kissing and embracingas a prelude to what would be comingnext, you are in for disappointment. Infact, as my experience shows, reality isgenerally divorced from rank imagination.Had I been a hedonist, a story of thistype would have had no novelty for me.Even if I had been a hedonist, the storywould have been cast in a different mold,making it difficult for you to recognizePriya as a protagonist of this story. Mypredicament however was of a differentnature. An intelligent and promisingstudent, born in an ordinary peasant familywho had worked his way through collegeon scholarships and was now associatedwith renowned scholars on a researchproject, could not break away from hispeasant background. I had kept myselfscrupulously away from girls and feltuncomfortable in their presence. Beingimbued with certain ideals and mores oflife, I had rigidly disciplined myself andclaimed to be all-knowing. So the excitementI had felt on meeting Priya for thefirst time at her house had now wornoff and I had again withdrawn into myshell. I was therefore reluctant to acceptat its face value what had transpired betweenus. Wasn’t all this make-believe an extensionof ‘The Quest for Man?’I kept tossing in bed the whole nightand got up late in the morning. The eagernessto meet Priya became overbearing.Certainly, she could have dropped in fora minute on her way to school. I kepthovering between hope and despair.Sometimes I felt angry at Priya and thensuddenly relented, realizing that she wasup against many difficulties herself. Inthe midst of this mental dilemma, I fellasleep. I had even overlooked to closethe door.At about three in the afternoon I felta hand over my forehead and I wokeup. It was Priya sitting in a chair bymy bed. “What’s the time?” I asked.“It’s going to be three-thirty,” she saidconsulting her watch. “Since when haveyou been sleeping?” she asked in a gravevoice.“I’ve been lying in bed since morning,”I said. “I didn’t sleep the whole night.In the morning while lying in bed I thoughtyou may drop in on your way to school.Then I fell asleep and slept on and on.I woke up just now when you came,”“You mean you didn’t even have yourbreakfast?” Priya gave me a concernedlook “Get up. We’ll have tea somewhere,”We went to a nearby restaurant whereJanuary-March 2010 :: 33

we sat for a long time, talking. Our previousmeeting, brief as it was, had kept us pinnedto one small point. But this meeting seemedto have thrown us in a welter of humanity.I had never imagined that a woman couldbe so simple and naive and yet hard asflint. Fear and irresoluteness seemed tobe foreign to her nature.As we were coming out of the restaurantshe said, “I’m suddenly confrontedwith a serious problem. I would like tohave your advice about it. I’ll talk it overwith you in detail tomorrow”At my insistence she said: “Today whenI was taking my high school class thePrincipal sent for me. You know the kindof institution I’m teaching in. Owing tothe patronage of the rich people of thetown the school enjoys all sorts of privilegesand we are paid well in keeping with theuniversity pay-scales. Well, when I enteredthe Principal’s office, I found the presidentof Manjari Trust sitting there along witha couple of other persons. On the tablelay photographs of my last night’s performance.The president was profuse inmy praise.Miss Mirdha, the Principal is very fondof me. She is a kind hearted woman andvery learned too. She was educated inLondon, you know. The fact is that ifshe had not been there I could not havegot this job. The president wanted to givethis position to a film artiste to whomhe was partial. But at the interview whenthe girl swayed her hips outrageously thePrincipal was so incensed that she closedher eyes with both her hands and refusedto take part in the proceedings.Anyway, today Miss Mirdha greetedme with a smile and introduced me tothose present in the room, including acine photographer, an actor, and a director,besides a dance specialist. As youknow, I lay no store by rich people andam averse to publicity. I refused scoresof offers to dance in films. Father waspleased. “My child,” he used to say, “Thereis no point in dancing before people whocan’t appreciate this art.”“As I looked at the people in the room,I suspected that something was brewingand my suspicion was confirmed whenthe photographer told Miss Mirdha thathe had made a film of my last night’sperformance which he would like to showfor the benefit of the visitors. I askedto be excused as I had to go back tomy class. Miss Mirdha hesitated for amoment and then said, “Please stay on.There’s no harm in seeing your handiworkin the film.”“I watched the film for some timebut by ears were attuned to those fourprofessionals who were explaining the finerpoints of the film, to Seth Ghinawan, thePresident of the school, in their own lightand putting forward interpretations to suittheir own ends.“It’s an eyeful, Sethji, isn’t it?”“And what suppleness and agility!”“There is only one thing missing.Eithershe should wear more diaphanous clothesor we should add a sequence of rain togive a drenching to her clothes.”34 :: January-March 2010

“The photographer kept babbling.“Sethji,” he said, “If I had known I wouldhave given such a swell to her contoursin this very film that people would havejumped in their scats. I would have madeit a first-class money spinner.”“I got up midway and went back tomy class. It was too much even for MissMirdha. “I fear Sethji may come up withsome outrageous suggestion,” she said tome later, looking worried. “I sensesomething fishy in the whole affair. Butyou need have no apprehension so faras I am concerned. I’ll stand by you.I’ve an inkling that they intend to arrangea special showing of this film on acommercial scale to all the rich peopleand collect a cool lakh or two. Sincc theschool supposedly had a hand in preparingthe film and it is being sponsored on behalfof the school, it will not be possible forme to oppose the scheme.”“Miss Mirdha, why are you exercisedover this matter? It’s no problem for me.Though I’m the daughter of a poor fatherI’ve my own pride. I’ll refuse to dancefor them.”“She seemed to have liked my remarkand affectionately caressed my head. “It’sjust the beginning, my child,” she said.“I fear there is more to it than meetsthe eye. But you need not worry. We’lltake things in our stride.” .We had gone far, talking and it wasgetting late. Priya asked me to see herhome. “Everything will crystallize in a dayor two,” she said. “We’ll wait till then.As for me, I know my mind very clearly.I won’t mind renouncing my job, if itcomes to that. Once I get embroiled inthis rigmarole, it will be difficult for meto extricate myself from it. I know whereit’s going to land me. Not that...” Shepaused to emphasize her point, ‘‘...l don’twant to dance or that I’m averse to dancingon the public stage. I am prepared todance by the roadside, in the fields, evenbefore factory workers and the peasants.My life and my art are dedicated to them.Sometimes I feel that; I’m an ignoramusso far as art is concerned. But I knowthe suffering which is the hard lot of millionsof my countrymen and also the glory andthe pride they feel in upholding the greattradition of their country. When I danceI become one with them. They are thesource of my inspiration and therefore,my dances in a way reflect their struggleand are dedicated to the new order theyare striving to establish.” As I listenedto Priya, her dance-drama, The Quest forMan’ came to have a new significancefor me.—You can bore through the heart ofthe most rugged mountains.—You can confine the most turbulentstorms within your arms.—You are the creation, the power,the movement, the very breath of mylife-my PriyaA curtain of darkness was whisked awayfrom before my eyes and every movementof Priya’s last night’s dance descendedinto the depth of my heart like a melody.The same invocation to the gods, the sameagony, the same thirst, the touch andJanuary-March 2010 :: 35

the embrace, the same pain of separationand the intense longing to be one withPriya: I had got lost in myself.Now that I am recapturing thosemoments after the lapse of such a longtime, I feel that I am wallowing in myown forgetfulness. I had decided to telleverything in a matter-of-fact way andnot be swept away by the torrential flowof my own feelings. Now when I thinkof it, I wonder what had made me watchPriya’s dance like one under some spell.Why didn’t I have a foreboding of whatwas in store for me? Now I can see thisin retrospect in a manner of speaking withmy hindsight. But that night after seeingthe dance, even though I had only a noddingacquaintance with Priya, I had found myselftransported to a new world where beauty,faith, devotion and simplicity were nolonger abstractions but embodied forms.After talking to Priya’s father I wasabout to leave when he called out to Priyaand wouldn’t let me go till I had partakenof some snacks. He came down to seeme off and asked me to visit them again.Past the stage of formalities Priya andI had now become friends. A bold girl,Priyalooked askance at social fads and suchlikeorthodoxies. I had also shaken offmy inhibitions and soon we became sofree with each other that my house becamea second home to her. I would daily escorther to her house. Kissing and embracinghad become the common expression ofour love but we never crossed the limitsof propriety. I have a feeling that Priyawould have resolutely set her face againstsuch indiscretion.Days passed. One day Priya returnedfrom the school much before the closingtime, looking tired and dejected. WhenI asked her, she said that what she fearedhad happened. “Today the seth came fullyarmed and put two proposals before me:a play for the benefit of the school anda short film which would be the first artproduction under the auspices of the school.The official stationery is ready, the contracthas been drawn up and all other formalitieshave been completed. Only my nameremains to be signed along the dottedlines. Since the film will be produced inthe name of the school, the school wouldhave the sale right over it; which in otherwords means that as the producer theSeth will be entitled to half the profitsaccruing from the film.”“And what will you get for your pains?”“Nothing. I’m only a commodity.Besides I’ve no entity apart from the school.By building up my image in other countriesthey want to enhance the glory ofwomankind. They also want to demonstratethe superiority of Indian dance over theother dance forms. Sethji will accompanyme to London and the States.” Priyasuddenly stiffened and started laughing.I had never seen her laugh so uproariously.“What’s wrong with you?” I asked, startled.“It has given me a terrible jolt,” shesaid. “Not that they have said anythingharsh to me but because they think peoplelike us to be so trite, insignificant andcontemptible. My father used to say thatthe rich, when they reach a certain stage,36 :: January-March 2010