Download - CTA Publishing

Download - CTA Publishing

Download - CTA Publishing

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

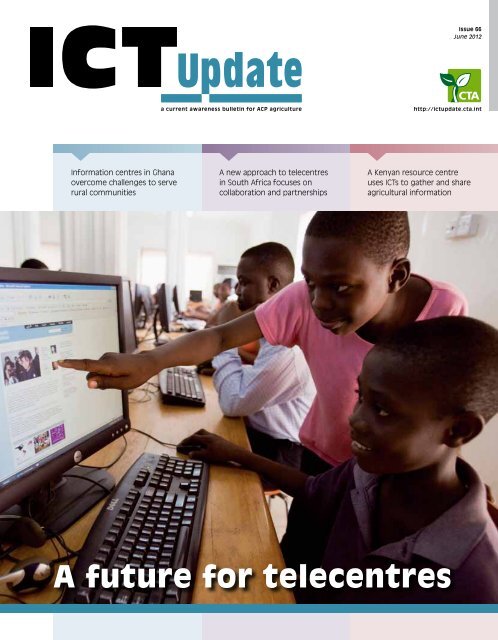

ContentsEditorial2 EditorialPast challenges provide newsolutionsA future for telecentresPast challenges providenew solutions3 PerspectivesThe essential essence of telecentresMiguel Raimilla4 Support at the centreStephen Agbenyo, Ken Kubuga andMartine Koopman7 A model of sustainabilityAhmed (Smiley) Ismael8 A service to the communityCharles O Ogada10 Diversify to surviveSimon Wandila11 BookmarkOffline browsing12 Resources13 Q&AAdapting to the situationMichael Gurstein14 Dispatches16 Tech TalkThe impact of ICTsAndrianjafy RasoanindrainyICT UpdateICT Update issue 66, June 2012.ICT Update is a bimonthly printed bulletin with an accompanyingweb magazine (http://ictupdate.cta.int) and e-mail newsletter.The next issue will be available in August 2012.Editors: Jim Dempsey, Evert-jan QuakEditorial coordination (<strong>CTA</strong>): Chris AddisonResearch: Cédric Jeanneret-GrosjeanLanguage editing: Mark Speer (English),Jacques Bodichon (French)Layout: Anita ToeboschTranslation: Patrice DeladrierCover photo: Olivier Asselin / AlamyCopyright: ©2012 <strong>CTA</strong>, Wageningen, the Netherlandshttp://ictupdate.cta.intThis license applies only to thetext portion of this publication.There are many models for bringingICTs to rural areas of ACP countries.Donor agencies and governments haveinvested in telecentres, small-scaleentrepreneurs have established villageinternet cafes, and NGOs and telecomcompanies have set up local cell phoneservices. Some initiatives are moreprosperous than others, but many havereceived a great deal of criticism in thepast. The intentions are usually the same;to provide remote communities with thecommunication and information facilitiesthey need for increased incomegeneration, and to offer access tofinancial, educational, health and otherservices that are more readily availablein urban areas. To deliver this kind ofaccess in the future, telecentres have toevolve quickly to ensure they can stillserve rural communities.The plan for the Ghanaiangovernment’s Community InformationCentre (CIC) initiative was to developtelecentres in 100 rural districts thatwould provide resources and access totechnology to communities bycharging businesses, organisations andindividuals for the use of the facilities.The for-profit services would cover thecosts of the community resourcecentre, but it was this combination thatcaused many of the centres to fail.While paying customers surfed the weband sent e-mails, the computers andother equipment were unavailable topeople from the community.As more CICs closed or failed to makea profit, external advisers were called into investigate the challenges facing thecentres, and suggest possible solutions.They discovered many reasons for thecentres’ poor performance, but onemajor finding was that few of the CICsprovided content that would beinteresting and relevant to the issuesfacing people in the community. Toincrease interest from people living inthe surrounding area, the centre staff –in co-operation with other relatedagencies and organisations – wouldhave to develop content locally, andmake that widely available to residents.ConnectionsThe Ugunja Community ResourceCentre (UCRC) in Kenya has been inexistence since 1988, and the staffthere quickly learned the importance ofproviding services relevant to thecommunity, most of whom are farmers.For example, UCRC provides a linkbetween national agricultural researchinstitutes and local producers.The organisation has a ‘farmer-leddocumentation’ programme, where theytrain farmers to use cameras and audiorecorders, and in report-writing skills togather data on agricultural practices andthe progress of newly applied techniques.They share the documentation with theresearchers and with other farmers usingprinted reports, presentations or evensongs and talks at community meetings.UCRC also provides a range of basicand advanced courses in technologyskills and computer literacy, and havebeen very successful in enrollingwomen in the courses. SiyafundaCommunity Technology Centres havemade training a priority too in thecommunities where they operate inSouth Africa. The organisation workswith major international technologycompanies to offer affordable ICT skillscourses to young people in areas ofhigh unemployment.Siyafunda has developed a broadnetwork of partners that supportvarious aspects of their centres’facilities. Local governmentmunicipalities make vacant premisesavailable and extend their ownbroadband internet for connectivity.Community organisations providesupport in developing services andinformation relevant to users andpromote the centres through their ownnetwork. All this is done in cooperationwith national governmentministries to make sure that there is noduplication of effort or unnecessaryextra investment in the samecommunity.A lot has been learned over the lastfew decades about how to set up andmaintain telecentre networks, and thereis clearly no single model that works inevery situation. Many organisations andentrepreneurs, however, are nowapplying those lessons and adaptingthem to provide ICT services, skillsdevelopment and support that is largelyabsent in many rural communities. ◀2 June 2012 ı ICT Update ı issue 66

PerspectivesMiguel Raimilla(mraimilla@telecentre.org) is executivedirector of Telecentre.org(www.telecentre.org)technological tools. Today, however,the role of telecentres has grownbeyond that. They now provide avariety of services to an even greaterand diverse clientele.Many governments invested heavilyin telecentres during the 1990s andearly 2000s. Similarly, multilateral andinternational aid organisations decidedto support the expansion anddeployment of computers to ruralareas. Most of these initiatives,however, lacked proper long-termevolved into a global community ofICT hubs, with a strong social missionand strong motivation to continuouslysearch for innovation and newopportunities.My own organisation, telecentre.org,started in November 2005 and until2009, provided grants, technicalassistance to organisations hostingtelecentre projects, and facilitated thecreation of telecentre networks in over40 countries. In March 2010, thetelecentre.org programme became aThe essential essence of telecentresA future fortelecentresTelecentres can serve awide range of functionsin the community,providing training,information services,and support for farmersand entrepreneurs.Franck Guiziou / HHThe beginning of telecentres can betraced to the mid-1980s, whenindividuals, and a handful of nonprofitorganisations, establishedtelecentres in several countries inEurope and the Americas. Since then,many ICT practitioners have preachedits extinction, pointing to theproliferation of more affordable andaccessible personal computers and,more recently, to the explosive growthof smartphones around the globe asevidence of the closing gap betweenthose with access to ICT and thosewithout.But, almost three decades later,telecentres are still here, present inalmost every country on Earth,providing critical services to more than1.5 billion people every day, and it isestimated that by the end of this decade,they could reach over 2 billion people.Initially, telecentres came about as away to bridge the digital divide andprovide access to information andtechnology to those who could notafford it or were geographicallydisconnected from accessingsustainability plans or properguidelines for service development.As a result, many of these firstprojects were cancelled and thetechnological infrastructure was oftenlost. Still, many of these modelsevolved. In some cases, the localorganisations in charge of these centresdeveloped alliances with non-profits,academia and other specialisedorganisations, which led to theemergence of a new model:Telecentre 2.0.DiversityThere are many examples of telecentresbecoming hubs for communitydevelopment and communityempowerment centres where thecommunity, as a whole, find and learnnew skills, and where the private sectorhas an opportunity to participate in thefuture delivery of products and servicesto a very diverse population.Telecentres today tend to be highlyspecialised, and yet continue to providebasic ICT literacy training. Even thoughpeople have increasingly sophisticatedand advanced needs and interestsregarding ICT, there is always a needfor basic training among sectors of thepopulation.We now see a wide range oftelecentres: from very humble trainingcentres in rural India, to state-of-theartinnovation centres in urbanBarcelona; telecentres that supportfarmers in rural Africa and Asia totelecentres specialising in women’sissues and children’s education;telecentres that have embraced theopportunities of entrepreneurialism inBrazil, to telecentres that provide achance for retirees to enter the digitalage in Europe. Telecentres haveformal and independent foundation,Telecentre.org Foundation (TCF),establishing its first office in Manila,Philippines.Long-term sustainability remains achallenge for many networks aroundthe globe, and one of TCF’s mainpriorities is to transform telecentrenetworks into channels for thedistribution of products and services.This allows the Foundation to engagein much broader alliances with theprivate sector and donors, developingstable business models for telecentres.As a result, more telecentres aredeveloping new expertise, becomingcritical providers for a variety ofcommunication and educationalservices, such as job placement,e-government services, agriculture andhealth-related training and services,the facilitation of access to newsources of funding and socialinvestment.Another fundamental factor in theresilience of telecentres is the humanfactor. Telecentre operators havebecome community leaders andfacilitators in many different areas ofdevelopment and community growth.The telecentre operator is often atrusted figure that facilitates access toinformation and opportunities thattransform communities, one person ata time.Despite all the latest technologiesand the undeniable massivepenetration of cell phones, therealways seems to be a need for a ‘bigscreen’ and a familiar face that helpsus navigate, learn and embrace thenew in this digital age. For this reason,telecentres will continue to play acritical role in the transformation ofour society. ◀http://ictupdate.cta.int3

A future fortelecentresThe Northern and Upper EastRegions of Ghana are dry anddusty for most of the year. Away fromthe main tar road between Tamale andBolgatanga the quality of other roadsis poor. Travelling from one town tothe next takes a lot of time. To drivethe 160 km from Bimbilla to Tamale,for example, takes around four hours.The towns in the region are connectedto grid electricity, but the supply issometimes erratic. The people who livethere are mainly subsistence and smallscalefarmers. ICT could play a role todevelop these rural areas.In 2005, the Ghanaian governmentlaunched their Community InformationCentre (CIC) initiative to introduce ICTsto 100 rural districts, in an effort toimprove connections and increase• serve as hub to access local andcentral government information• create awareness of ICT in ruralareas• disseminate information to ruralareas on health, agriculture, localgovernment and education• provide the opportunity for ICTtraining in rural communities• support rural business activities,such as access to marketinformation, extension services, etc.)From 2008, those centres based in theNorthern and Upper East Regions havereceived further support from theInternational Institute ofCommunication and Development(IICD), and coordinators from localorganisations, Savana Signatures andBold Steps Foundation. The advisorsCIC was yet to open after two faultystarts. Both had problems recruitingand retaining staff and management.Zebilla CIC was officially open to thepublic but bats in the ceiling of thebuilding gave a good indication of howfrequently it was used. Sandema centrewas just beginning with a newmanager and a supportive districtassembly. And Bolgatanga CIC wasexpected to bring in revenue, but itwas challenged with a poorrelationship between staff and themunicipal assembly.’By organising meetings and trainingsessions on subjects including businessdevelopment, open source awarenessand basic troubleshooting, CICmanagement and staff graduallygained their confidence, skills andSupport at the centreIn the years since they were first established, Ghana’s community information centreshave faced a wide range of challenges as they bring ICTs to rural communities. With thehelp of specialist advisers, many of those problems have been overcome.development in the communities. EachCIC is a combination of not-for-profitcommunity resource centre and forprofittelecentre. The first centres startedwith the physical building connected tothe electricity grid, a local area network(LAN) with at least five computerworkstations, one printer, one scannerand five uninterruptable power supplyunits. The idea was that the CICs shouldbecome sustainable after a couple ofyears under the ownership of therespective district assemblies.The CICs were established withseveral objectives, to:• offer rural communitiestechnological opportunities seen inurban areasStephen Agbenyo (ninsgh@yahoo.co.uk) is director of SavanaSignatures (http://savsign.org/), Ken Kubuga(kenkubuga@boldstepsghana.org) is director of BoldStepsFoundation (www.boldstepsghana.org) and Martine Koopman(mkoopman@iicd.org) is country manager Ghana at theInternational Institute of Communication and Development(www.iicd.org)provided technical advice to the districtassembly on how to make the centressustainable, and helped to develop theskills of CIC staff, and managers inparticular, by giving hands-on trainingand mentoring, sharing informationand organising meetings with relatedprofessionals and people in thedistricts.Apart from offering the ICT skillsand services to the community, thecentres were intended to generate andkeep relevant content that could beaccessed by the community. Thetraining courses, therefore, focused ondeveloping business skills (making abusiness plan and marketing thecentre), content development (videomaking, blog writing) and trainer oftrainer sessions to enable the staff totrain the community members in basicICT skills.MotivationThe five northern CICs faced a numberof challenges in the beginning,according to Ken Kubuga, adviser ofBold Step Foundation. ‘In 2008, theNavrongo centre closed, and the Bongoknowledge and slowly started to turnaround their centres.For example, the Bolgatanga CIC, theonly one of the five northern CICslocated in a town, continued to servean increasing number of visitors, andits focus was gradually shifted frombeing an internet café to being aninformation and training centre. Thetwo staff members were soon joined bysomeone on national service duties,who came at no extra cost to thecentre, and by a VSO volunteer whowas attached to the municipalassembly.Both volunteers championed thetraining sessions at the centre anddeveloped new initiatives, such as ayouth ICT camp during schoolholidays, but most of these never sawthe light of day due to inadequatefunds. Poor relationships with thedistrict assemblies and the inability tosustain interest even in a self-initiatedidea continued to stall theimplementation of newer plans. Despitethis, the CIC continues to be thepreferred place for NGO staff, localgovernment workers, civil servants and4 June 2012 ı ICT Update ı issue 66

jake lyell / ALAMYPupils admitted theywould never have hadthe opportunity to usethe technology at homeor in schoolpublic school students to go forsecretarial services and internet access.When the Bongo CIC finally openedit quickly became the centre of ICTsupportedservices in the district.Nearby basic schools began to havetheir ICT lessons at the centre, withmany pupils having their firstexperience with a computer there.The centre in Zebilla, meanwhile,became an important facility for 14basic schools, whose pupils came forweekly practical ICT lessons. Most ofthe pupils who attended admitted theywould never have had the opportunityto use the technology at home or inschool where there was no electricity.The centre increased its support role byorganising a district-wide ICT quiz forschools, and an open ICT forum similarto the monthly ICT4D discussion seriesfound the cities of Tamale and Accra.Participants of the two programmesexpressed hope that these events wouldbecome regular features.But it was the centre in Sandemathat became the star of the fivenorthern CICs, by showing financialsustainability. A few months after theskills training activities, the centre wasgenerating sufficient funds to pay staff,and was able to purchase equipment inorder to expand the scope of services.The centre continues to be an exampleof a successful CIC despite thechallenge of being located in arelatively remote area with low literacylevels.In 2010, the northern CICs received afurther boost after they were suppliedwith equipment, includingphotocopiers, LCD projectors, digitalcameras and binding machines. Whilethe extra equipment helped the centresto become more financially sustainable,the training on content developmentdid not result in locally developedcontent, as expected.AssessmentIn 2008 and in 2010, visitors to thecentres were asked to complete aquestionnaire to evaluate the perceivedimpact of the project. The mostinteresting results came in from theirviews on the perceived impact of thecentres. 65% of the participants becameCIC SalagaFinding the balancebetween serving thecommunity andproviding profit-makingservices can be achallenge for ruralinformation centres.Salaga, in rural Ghana, has a population of 27,000, servinga wide range of potential users, from students, teachers,farmers, health workers and business people. The maingroup that visits is students, often between 20 and 50 a day.Most schools in Salaga don’t have computers, but ICT is acompulsory subject. They can now use the CIC as a computerlab. But this interferes with the centre’s internet cafe servicessince it only has 13 computers. Other key services arewireless internet for those who can bring their own laptop,ICT training in the form of basic ICT skills, maintenance, andcontent development, such as blogging and video production.The centre also provides secretarial services and somecontent development, mainly video coverage of local events.The community did not choose the location of the centre,otherwise it would have been closer to the town centre.http://ictupdate.cta.int5

A model of sustainabilityAn organisation in South Africa has developed a network of local and internationalpartners to offer a broad range of technology services to underserved communities.A future fortelecentresClose collaborationmeans the partnerorganisations can sharecosts and resources,and reduce the chancesof duplication.The idea was to bring technology tounderserviced areas of SouthAfrica, places that had seen littleinvestment in the country’s history.Many of these places, known astownships, are densely populated andclose to large urban centres, but theystill do not have access to technology.Having technology nearby, however, isnot the only challenge to be overcome.It has to be affordable too.In 2006, Siyafunda CommunityTechnology Centres started to look atways to bring ICTs to communities inthe Ekurhuleni (East Rand) area ofSouth Africa. The organisation wasaware of previous attempts tointroduce specialised technologycentres to communities in the country,and was determined not to make thesame mistakes.The government had set up nearly200 telecentres in townships and ruralareas across the country in the late1990s. Unfortunately, as there was littleongoing support for the centres andtheir management systems afterwards,very few of them remained operational.Siyafunda wanted to introduce anew model for running communitytechnology centres, and worked todevelop the facilities with othercommunity-based organisations thatAhmed (Smiley) Ismael (smiley@siyafundactc.org.za) isdirector of Siyafunda Community Technology Centres(www.siyafundactc.org.za)G Rambaldi / <strong>CTA</strong>were already present in the area’stownships. There were no publiclyavailable broadband services in thearea, for example, but the offices ofthe Ekurhuleni Metro Municipalitywere connected. Siyafunda engagedwith the municipality to make theirnetwork available for a technologycentre’s internet connectivity, and alsoarranged to turn some of their vacantpremises into digital hubs.The organisation continued to developpartnerships with other governmentagencies, local community, social andeducational organisations, technologycompanies, including software developerSAP, and with entrepreneurs.These partnerships have helpedSiyafunda offer a wide range ofservices that are affordable and atrates that still ensure the centres havesufficient income to make themfinancially viable. The organisationalso provides regular training coursesfor the centre managers. The courseshelp managers develop services thatthe local communities want, and giveadvice on how to promote the centres.Siyafunda started with one centre inNovember 2006, with the intention ofrunning it for around 12 months to testtheir model of establishing sustainabletelecentres through affordable servicesand electronic learning opportunities.A local community organisationbecame interested in the work, andsoon after went into partnership withSiyafunda to open a second centre.This opened up a network of similarorganisations operating in othertownships and, as word spread, thenumber of centres rapidly expanded.There are now around 50 centresoperating around the country, all withlinks to existing communityorganisations or businesses thatrecognised the need for access to ICTs intheir area. These community technologycentres, therefore, arose from demandwithin the community and aresupported by established enterprises.Vital connectionsBy offering a wide range of services,the centres attract a variety of users,including schoolchildren withhomework projects, unemployed youthlooking to develop their technical,business and other skills or look forjobs, and NGOs and small businessesthat make use of the office services orequipment that would otherwise be tooexpensive for them to buy.The challenge of reachingcommunities beyond the urban centresand townships remains, however. Toexpand the technology services tothose areas, Siyafunda supportsinternet cafes already present in remotecommunities to adapt to their businessmodel and expand their services. Moreuniversities and municipalities in SouthAfrica are interested in the model, withSiyafunda set to develop around 30new centres in rural parts of theLimpopo and Mpumalanga provinces,and in the semi-arid areas of theNorthern Cape.Recent recognition as best telecentreinitiative of the year at the 2011 eIndiaawards has raised the profile of thecommunity technology centreprogramme and put Siyafunda in touchwith other related businesses. Theorganisation is investigating ways tomake use of these new connections todevelop the use of mobile networks andprovide cost-effective services to ruralareas. Wireless technology can extendan internet connection and remove theneed for cables, or even the need for aphysical bricks and mortar centre.Perhaps the greatest advantage ofworking with a carefully selected groupof partners in community accessschemes is that it avoids duplicationand re-invention of the wheel. Closecollaboration and clearly definedworking relationships betweengovernment agencies, educationalinstitutions, businesses and communityorganisations means that resources andcosts are shared, and the likelihood oftwo centres opening in the same smalltown are reduced. All this helps toensure that communities get theservices they need, at a price they canafford, and from a centre that is likelyto be around for the foreseeablefuture. ◀http://ictupdate.cta.int7

Jorgen Schytte / LineairA service to the communityA resource centre in the west of Kenya adapts its information services tothe needs of the community, with ICTs playing a major role in gatheringand sharing information.A future fortelecentresUgunja Community Resource Centre(UCRC) was founded in 1988, andregistered as an NGO in 2004. It servesthe Siaya, and neighbouring counties,of west Kenya. Poverty in these partsof the country has been increasing overthe years, especially in the low-lyingdistricts where rainfall levels are lowand soil quality is poor. UCRC isbasically a grassroots organisation,providing a community hub forinformation on agriculture,environmental conservation, humanrights and advocacy issues.Charles O Ogada (charles@ugunja.org) is programme manager,adaptive research and information technology, at the UgunjaCommunity Resource Centre (www.ugunja.org)The centre offers internet access topeople living in the neighbouringcommunities, via a 3G connection overthe cell phone network. The connectionis reliable, and provides enoughbandwidth for UCRC staff to carry outtheir work writing e-mails and forvisitors to browse the web.To help people in the communitybecome more familiar with technology,the centre organises computer literacycourses, based on Microsoft’s UnlimitedPotential curriculum. These are open toeveryone, but are mainly intended forwomen and young people living in thearea. UCRC also has a traditionallibrary, housing a variety ofcollections, but with a particular focuson publications related to agriculture.All of the centre’s activities andinformation services are initiated anddeveloped according to the needs ofthe people living in the area. Thegrowing popularity of cell phones inrecent years means UCRC staff nowassist people in making mobile moneytransfers, getting agricultural marketinformation via SMS, relaying newsstories, and connecting farmers withpotential partners in transport,processing and marketing.UCRC has already used FrontlineSMS– free software for sending multipleSMSes – in an education programmedelivering information to people livingwith HIV/Aids. Trainers at the centreare now formalising a similar processthat allows farmers to learnagricultural techniques via SMS.In the last few years, the region hasexperienced low and erratic rainfallthat has resulted in very poor crop8 June 2012 ı ICT Update ı issue 66

yields. The production of maize, whichis the main staple food for the farmers,has seriously declined. Currently,farmers can only produce enoughmaize to last three months. For theother nine months of the year, thecommunity has to rely on maizecoming from beyond the local area,bought from the main market centres.The lack of money to buy extra maizeresults in real hardship for manyfamilies for those nine months.Equally, the quality of soils in Siayahas been seriously depleted due tocontinuous tillage and poor farmingpractices over many years. Researchcarried out by the World AgroforestryCentre (ICRAF) in the district in 1998established that Siaya soils lacknitrogen and phosphorus, which areimportant nutrients required for plantgrowth and good crop yields.Many farmers do not have enoughmoney to buy the inorganic fertilisersrequired to improve the soil and cropproductivity. They also need moreinformation and skills to raise crop yieldsthrough organic farming techniques.RegenerateTo mitigate these challenges, UCRC hasbeen promoting farming technologiesand crops that can survive withcomparatively little moisture. Suchcrops include sorghum, sweet potatoesand cassava. The organisationencourages farmers to plant high-valuetrees and to experiment with indigenousvegetable gardening. For example,farmers are growing fruit plants,including banana, pineapple and mangoin income generation projects.These initiatives are part of thecentre’s sustainable agriculture project,which has been in existence since theestablishment of the organisation. Theactivities of the programme mainlywork towards building farmers’capability to help them cope withchanges in the climate.Although the centre is based in thetown of Ugunja, UCRC still has to be ableto provide information to the farmers inthe wider area. The organisation has,therefore, developed a number ofstrategies to ensure that farmers fromfarther afield can participate in itsprogrammes. UCRC provides supportiveextension services, where the fieldofficers visit farmers to give them advice.Another way is through establishedcommunity groups, where theorganisation delivers training courses asrequested by the farmers during theirscheduled meeting times. The othertraining courses and workshops providedare based on an assessment of thefarmers’ needs and available resources.The centre also organises on-farmdemonstrations and tries out newagricultural techniques. In theseinstances, UCRC works with researchinstitutions, including KenyaAgricultural Research Institute (KARI)and Kenya Forestry Research Institute(KEFRI), as a way to bridge theresearch information gap between thefarmers and the researchers.As part of this, the farmers are nowtrained in ‘farmer-led documentation’(FLD) techniques, where the farmersrecord their progress and localinnovations. This means that the farmershave been trained to use digitalcameras, audio recorders, videocameras, drawings and report writingskills to capture and store data. UCRCstaff work with the farmers and offertechnical support during regular visitsto the farms.DistributionDocumentation has been especiallyimportant for the testing of newtechniques to cope with the changingclimate. Agricultural researchers arehelping farmers to adopt and devisemethods to mitigate the effects ofincreasingly unpredictable weatherpatterns. FLD is one way of making theinformation gathered on newtechniques available to more people,and of facilitating data sharing in ashort period of time.The information gathered is alwaysshared in organised communitymeetings, where farmers can presenttheir findings by showing thephotographs, reading out reports, oreven through songs and participatoryeducational exercises. The membersthen discuss the information, and try tofind resolutions to problems andconsider methods to ensure the lessonslearned are taken up by the broaderfarming community.UCRC also uses community learningand resource centres. These are smallermeeting areas in the villages wheregroups of people can share informationon new farming methods. These centresusually do not have the same ICTequipment as the main centre, althoughthey do have libraries for printeddocuments and books. In the course oftheir regular visits, however, UCRCstaff take their laptops to show digitalpresentations or videos, many of whichRelated linksKenya Agricultural Research Institute➜ www.kari.orgKenya Forestry Research Institute➜ www.kefri.orgFrontlineSMS➜ www.frontlinesms.comICT Update article on FrontlineSMS➜ http://goo.gl/5UQzzcan also be viewed and copied to cellphones.Visitors to the community centres canask questions, which, if they cannot beanswered immediately, are noted onspecially developed forms andforwarded to UCRC or other agriculturalextension providers, for feedback. Theprocess is similar to how manyquestion-and-answer services operate.To ensure that the skills acquiredthrough the training courses and otheractivities will continue to be used andshared in the long term, UCRC hastrained ‘master farmers’, who can actas mentors and trainers in their localarea. Farmer groups also have trainingon organisational methods and avariety of management skills, includingsubjects such as group dynamics.The sustainable agricultureprogramme within UCRC has, over theyears, helped to introduce and promotenew farming technologies to counterperennial climatic challenges, andimprove food security in the areas. Theorganisation’s work goes beyond beingsimply a resource centre to provide vitalcapacity for sustaining the livelihoodsof people within the community. ◀As crops in the areaaround Ugunja sufferfrom unpredictableweather patterns,UCRC developsstrategies for deliveringclimate changemitigation informationto farmers.Shehzad Noorani / Lineairhttp://ictupdate.cta.int9

Diversify to surviveA study group from the Southern Africa Telecentre Network visited Botswana to see how public–privatepartnerships have changed the country’s telecentre development programme.A future fortelecentresTelecentres have toprovide locally relevantcontent to attractcustomers from thecommunity andincrease profitability.The picturesque village of Sikwaneis situated in the south-westerncorner of Botswana, around 50 kmfrom the capital, Gaborone, and closeto the border with South Africa. Thevillage has fewer than 2,000inhabitants, most of whom arelivestock farmers. And, it has atelecentre, developed as part of thecountry’s rural infrastructuredevelopment programme, Ntseletsa, theTswana word for ‘call me’.The government of Botswanafinanced the first phase of Nteletsa,with Botswana TelecommunicationsCorporation (BTC) charged withdeveloping the rural centres. For thelatest phase, Nteletsa II, thegovernment entered into public–privatepartnerships to establish around 200centres around the country.The Nteletsa II telecentres aremanaged by the local villagecommunity, through villagedevelopment committees (VDC). TheSikwane centre employs three people: asupervisor from the VDC, and twoyoung people who are paid on acommission basis. The centre is housedin a specially converted container, andhas three desktop computers, a faxmachine, a printer, a photocopyingSimon Wandila (simonwgreg@gmail.com) is programs managerat Youth Skills for Development (www.youthskills4dev.org), anda board member of the Zambia Telecentre NetworkRoel Burgler / HHmachine, a community payphone, andis connected to the internet via the cellphone network through a 3G router.The centre provides office services,including photocopying, faxing,laminating and document processing, aswell as telephone services, cell phonecharging, SIM card and cell phoneairtime sales, and internet access. BTCprovided the initial stock andequipment, continues to cover electricitycosts, and gives technical support, suchas equipment maintenance and repair.Like other Nteletsa II telecentresaround the country, the centre inSikwane faces a number of challengesthreatening its sustainability, mainlybecause few people make use of itsservices. The main economic activity inthe area is livestock farming, and themajority of the population is elderlysince many young people have migratedto the main urban centres for work.EngagingIn 2011, a study group from the ZambiaTelecentre Network and Southern AfricaTelecentre Network visited Sikwane toinvestigate the long-term viability ofthe centres and to consider possibleimprovements for sustainability. Thegroup spoke to the Nteletsa II centre’ssupervisor, who explained that revenuewas too low for the centre to cover itscosts, and that employees often had towork without pay.The supervisor was concerned thatpeople did not visit the centre becauseit did not offer sufficient services forcustomers. She suggested that thecentre could expand its services toprovide the sale of prepaid electricitytokens, stationery and other relatedgoods to attract more visitors andincrease revenue.The study group also found that localfarmers had a clear need for informationon subjects such as climate changeadaptation, weather services andagricultural training. In rural villages,like Sikwane, where the majority ofpeople depend on agriculture for theirlivelihood, and where land overgrazingand desertification are critical issues,provision of such information serviceswould enhance agricultural production,improve food security and increaseincome.To provide this kind of informationand, more importantly, to make itrelevant to local residents whether theyare in Sikwane or any of the 300 plusvillages covered by the Nteletsa IIcentres, the study group recommendedthat the content be produced locallywith consideration for the needs of thesurrounding population. This means therelevant information has to be gatheredand repackaged for each community.Developing local content cannot beleft solely to the staff of the individualtelecentre or ICT specialists. Instead, theproduction of information has to involvepeople from all involved sectors,including education, agriculture, health,meteorology, mining, with input fromsocial and economic experts. Agriculturalresearchers and extension officers needto work together with the villagedevelopment committees and othersupporting partners to develop contentand information services relevant to theeconomic activities of the villagers.With information available that isrelevant to their specific area andlivelihood, people living around thetelecentres will visit more often tomake use of the services. This, in turn,will increase the revenue for the centre,helping it to become sustainable andinvest further in improving servicesand products, and adapt to futuredevelopments as the needs of thecommunity change. And, the circle iscompleted as villagers benefit from asuitably resourced telecentre.As the telecentre model in Botswana,and many other countries, changes fromgovernment and donor-funded initiativesto closer collaborations involvingbusinesses and community organisations,village-based centres will be able toprovide more locally relevant content.The study group concluded that thepublic–private partnerships of theNteletsa II programme would certainlyhelp the centres increase ruralcommunities’ access to information in away that can be sustainable for survivaland adaptable to future developments. ◀10 June 2012 ı ICT Update ı issue 66

BookmarkOffline browsingA future fortelecentresFor telecentres with limited internetaccess, it can be useful to have a localcopy of some websites. Web browserslet you save individual pages, but notan entire site. For that, you needspecialised software. True offlinenavigation requires a mirror (copy) of aparticular website on a hard drive withthe content and link structure torecreate the original site’s structure.HTTrack is a free and open source websitecopier. It is multilingual and compatiblewith Windows (WinHTTrack), Linux andOSX (WebHTTrack). The program is easy toinstall and use, is fully customisable andactively supported by the developer. Thisfreeware will automatically download aHTTrack will automatically downloada website’s entire content, or even justa specific section of it, for future offlinereferenceWith copies of usefulwebsites on a localhard drive, telecentrescan still offercustomers access toinformation even whenthe internet connectionis downwebsite’s entire content, or even just aspecific section of it, for future offlinereference.Copy a siteVisit www.httrack.com, open thedownload page from the top menu andselect the appropriate version of theprogram, based on your operating system.Staff Photographer / ReutersThe first time you launch theapplication, you can select the preferredlanguage. Change the language anytimeon the ‘About WinHTTrack Website Copier’page in the Help menu.The program uses a wizard to guide youthrough the necessary steps for capturingand saving websites. On the first screen,you can type the name of a new project orselect an existing project to update orresume. It is best to create one project perwebsite or section of a website: name theproject after the site you plan todownload.You can also add categories which areoptional and useful to group or distinguishbetween the projects. Create or assign onecategory (the application will rememberthem) to each project you start to groupthem under their respective subjectmatter. Browse your computer’s hard driveto save the file in the folder of yourchoice, e.g. C:\My Web Sites.On the next screen, choose what actionto execute from the options: copy awebsite, resume a download or update amirror already on your hard drive. If youselected an existing project on the previousscreen, the program automatically choosesthe appropriate action.Get startedTo start a new project, add the URL of thewebsite you want to copy. Websitescontains a lot of content and files thatmay not be important to you. HTTrackdevelopers strongly recommend usingURLs for each project that refer only toa section of a website. To download thearchive of ICT Update’s past issues, forexample, add the following web address:http://ictupdate.cta.int/Issues.Below the text box showing the URL,the ‘Set options’ button opens a windowwith several tabs each letting you setdownload parameters and mirror options.Here, you can use filters to skip large datafiles, like pictures or PDFs, and setbandwidth capacity and maximum pagesize, among others.The filters are essential to keep the sizeof the download to a minimum. In the ‘Setoptions’ screen, select the ‘Scan rules’ tab.Here you can specify the types of files notto download. If downloading ICT Update’sarchive, for example, you can choose toexclude the pictures (with file extensionsjpg, gif, png) and the PDF files.The FAQ section on the HTTrack websiteexplains in detail how to set the differentRelated links➜ www.httrack.com/page/2/en/index.html➜ www.blogtechnika.com/copyentire-websites-for-offline-viewingwith-win-httrack-website-copier➜ http://betanews.com/2012/01/26/grab-entire-websites-with-httrack/parameters and filters correctly, to avoiddownloading the entire world wide web.The final screen lets you define aremote connection access if necessary andalso set a timer to postpone the actualdownload. In most cases this will not benecessary, and you can leave these optionsblank and click ‘Finish’ to start thedownload. <strong>Download</strong>ing a website willtake time and bandwidth. Thedownloading pane will show what filesare in the process of being captured: ifsome are too slow to get, press theassociated ‘Skip’ button to discard them.The hard drive will typically needbetween 500MB and 1GB of free memoryfor each site, or part of a site. And, sincedownloading so much data takes a longtime and uses a lot of bandwidth, itmight be a good idea to plan thedownloads at quieter times, or evenduring the night, to save the internetbandwidth for users.When the site has downloaded, openthe folder where the copy was saved onthe hard drive, and select the ‘index.html’file to start using the mirrored site.Important informationSome websites may block automatedwebsite copiers like HTTrack for legal ortechnical reasons, where the content isprotected by copyrighted content or toprevent overuse of the original server’sbandwidth capacity. Wikipedia andYouTube, for example, do not allowwebsite copiers. Content on Wikipedia canbe downloaded at the following address:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Database_download.The FAQ section on HTTrack.com givesfurther information on when to notify asite’s administrator before you copy awebsite. ◀http://ictupdate.cta.int11

ResourcesDocumentsWeb resourcesProjectsA future fortelecentresPublic access to ICTs: Sculpting theprofile of users – Working PaperBased on a survey of public access ICTusers in five countries, this workingpaper outlines some basic characteristicsof users: their demographics, history ofusing ICTs and reasons for using publicaccess ICTs. Most users’ first contactwith computers and the internet was in apublic access venue, and even those whohave access at home visit these venuesfor other reasons, such as betterequipment, faster connections, beingwith friends or having access to helpfrom venue staff.➜ http://goo.gl/JIZnXTelecentres in Uganda do not appeal torural womenAn evaluation of telecentres by the Acaciaprogramme in South Africa revealed thatwomen consistently make up less thanone-third of telecentre users, even whenfemale staff and materials that targetwomen are made available. The UgandabasedNGO, UgaBYTES, found that, beyondthe common obstacles to access liketechnical infrastructure, connection costsand computer literacy, women facenumerous additional barriers to accessingICTs.➜ http://goo.gl/B6D6cLighting up the Dark: TelecenterAdoption in a Caribbean AgriculturalCommunityThis study, published in the Journal ofCommunity Informatics, examines howresidents of El Limón de Ocoa, a remoteagricultural community in the DominicanRepublic, have integrated the use of ICTssince the establishment of a localtelecentre in 1997. As the longestcontinuous-running independenttelecentre in the Caribbean nation, thissite was useful for studying the impact ofcommunity-driven ICT adoption inunder-privileged rural areas.➜ http://goo.gl/gYkgUJohn Katz / El LimonSauti ya wakulimaFarmers in the Chambezi region of theBagamoyo District in Tanzania usesmartphones to gather audiovisualevidence of their practices, and publishimages and voice recordings on theinternet. Since March 2011, theparticipants of Sauti ya wakulima (voiceof the farmers), use the phones to makereports about their observations regardingchanges in climate and related issues, andto interview other farmers, thus expandingtheir network of social relationships.➜ http://sautiyawakulima.netKnowledge and Information for FoodSecurity in AfricaRural telecentres can serve as information‘depots’ that provide regional, national andinternational information to agriculturaldevelopment workers, includinginformation on markets, weather, crop andlivestock production, and natural resourceprotection. In Africa, agricultural colleges,rural schools, experiment stations,extension offices, NGOs and in some placesfarmer organisations, offer a ready-madeinstitutional and human network forelectronic connectivity.➜ http://goo.gl/tlyIBImproving livelihoods with ICTsThe gap in ICTs between North and Southis gradually shrinking. The developingworld accounts for two-thirds of totalmobile phone subscriptions, and Africahas the world’s fastest-growing mobilephone market. But to be sustainable,technologies need to factor in socialrealities. These include how people alreadyshare knowledge, and adapt to introducedtechnologies: mobile phones, for instance,confer status but can eat into muchneededincome. Many developmentagencies opt for technology-led solutionsthat fail to ‘take’. Approaches that keepdevelopment concerns at their core andpeople as their central focus are key.➜ http://goo.gl/1sw0lDavid Snyder / Zuma Press / HHArid Lands Information NetworkALIN employs field officers to run localtechnology access centres in Kenya, knownas Maarifa centres. The centre is a room or aconverted shipping container equipped withcomputers and internet. It is an informationhub where local knowledge is documentedby communities with the support of the fieldofficers and shared widely. The centres arealso information resource bases withpublications, newsletters, research reportsand electronically stored information thatinclude CD ROMs, audiovisual material andcompendiums.➜ www.alin.or.keThe Village Base StationThe Village Base Station (VBTS) provides aflexible independent telecommunicationsservice that can be powered by wind orsolar energy systems, which can besignificantly cheaper than similar systemsrunning on diesel generators. VBTS isessentially an outdoor PC with a radio toprovide a low-power low-capacity GSMbase station with long-distance WiFi takingthe signal to the carrier service. The basestation can be deployed in the middle ofthe village, on a nearby hill, or in any otherarea with line-of-sight coverage.➜ http://goo.gl/kayn1Agriculture Research and RuralInformation NetworkStarting in 2003, the ARRIN project hasbrought agricultural information to ruralcommunities in Uganda by combiningdance and dramatic plays with ICTs. Thetheatre company, Ndere Troupe, whichperforms all over Uganda and has its mainoffice in Kampala, is responsible forimplementing the project, which aims toempower rural populations andcommunities by promoting and supportingincome-generating capacity, as well asawareness of public policy and health andenvironment-related issues, through theeffective dissemination of information.➜ http://goo.gl/nZ8GiGates Foundation / flickr12 June 2012 ı ICT Update ı issue 66

Q&ADon HollanderHow can rural communities benefitfrom access to ICTs?➜ People living in rural communities, andelsewhere, benefit from access to ICTs, andthe internet, by being able to participate inthe full range of activities of contemporarysociety, including culture, economy andpolitics. Many, if not all, of these aspects oflife are totally intertwined, enabled,enriched and powered with ICTs. Nothaving access is in some respects a modernform of disability, and certainly a form andsource of considerable impoverishment.Do telecentres help to give communitiesaccess to information?➜ The situation has changed dramaticallysince the beginning of the telecentremovement. In the beginning, the primaryneed was to familiarise people with theopportunities that ICTs provide, and tomake access available in places, forpopulations, at prices that were affordableto people in rural areas. Now we havemobiles providing relatively low-cost accessin places where fixed lines are unavailable,so some of the initial access and most ofthe initial familiarisation issues have nowbeen resolved.But the reasons that people wantedaccess and used telecentres haven’tchanged all that much. People in ruralareas still need to have access to usefulinformation, to education, to healthcare, tofinancial services and so on. Some of thoseservices can be provided at a cost, and withcertain limitations, via mobiles but otherscannot. So while some of the initial reasonsfor establishing telecentres no longer exist,that doesn`t mean that telecentres noAdapting to the situationA future fortelecentresWhile some of theinitial reasons forestablishing telecentresno longer exist, thatdoesn`t mean thattelecentres no longerhave a function.Michael Gurstein (gurstein@gmail.com)is executive director at the Centre forCommunity Informatics Research,Development and Training (CCIRDT) inCanada (http://communityinformatics.net).He also has his own blog, Gurstein’sCommunity Informatics(http://gurstein.wordpress.com)Ayllon / Alamylonger have a function. It simply meansthat that function has (or should have)changed.What, to you, makes a successfultelecentre?➜ I don’t think telecentres should belooked at in isolation from: their broadersocial and economic environment; from theset of connections that they have withlocal businesses, organisations, markets;and from the network of telecentres andtelecentre support services, of which theyshould be a part. These connections andnetworks are necessary for a successfultelecentre operation. We should be usingthe network as the basic unit of analysis fortelecentres. Without the links to othertelecentres and the local business andsocial ecology, the individual telecentreisn’t able to accomplish a great deal.What other ways are there forimproving rural communities’ access totechnology?➜ Access to technology is in itself ofrelatively little value. What is valuable is theaccess to the opportunity to usetechnology in meaningful and useful ways,to learn, to conduct business, tocommunicate with loved ones and friends,to get health advice and medical servicesand so on. The technology is a simply ameans to these ends, and the particulartechnology required will depend on thoseservices. If the services are sufficientlyimportant, ways to access to thetechnology will be found.How can any initiative working to giverural communities access to ICT adaptto keep up with new technologicaldevelopments?➜ The challenge isn’t keeping up with newtechnological developments; rather thechallenge is to find appropriate servicesand functionalities of value to those incommunities. If those services andfunctionalities are found and implementedthen, whether the technology is the newestor not doesn`t really matter, the applicationwill determine the technology rather thanvice versa. Of course, newer technologiesmake additional services possible, so thereis a continuing evolution, but the evolutionis driven by the services and uses, not bythe technology.How do you see telecentres developingin the future? Will they still have a roleto play while more people have theirown cell phones with morefunctionality?➜ Cell phones have certain advantagesand certain limitations, as do telecentres. Inthe future, I see synergies between the two,where the advantages of both areintegrated to provide enhanced services inrural areas. Telecentres would evolve asplaces for people to gather and meetface-to-face, with the opportunities forsocial interaction and immediacy ofcommunication that is possible in thoseenvironments.Cell phones, meanwhile, provide theopportunity for extending thoseopportunities into places and activitieswhere they had not previously beenpossible, and for providing an immediacy ofresponse that may not be as available intelecentres. On the other hand, telecentresare able to provide much more complexinformation and support, facilitatinginformation search, supporting servicedelivery, integrating ICTs into communityand organisational processes in ways thatare difficult or awkward to design andimplement via mobiles. To my mind,development activity requires a mix ofboth. ◀Michael Gurstein’s blogthoughts on telecentresTelecentres are not ‘sustainable’ – getover it!➜ http://goo.gl/1lugvRe-thinking telecentres: acommunity informatics approach➜ http://goo.gl/P562zNext generation telecentres➜ http://goo.gl/xnbVPhttp://ictupdate.cta.int13

DispatchesResponding to climate changeICT is not the only technologyICT cannot exist in isolation, and African governments that consider their ICT policyto be a technology policy should think again, warns Ndubuisi Ekekwe, founder ofthe non-profit African Institution of Technology in an opinion piece on SciDev.Net.Ekekwe recognises that ICTs are essential for development, creating linkages betweenpublic and private institutions, and people and corporations. ICTs improve the speedand efficiency of many processes and make digital education and e-governmentinitiatives possible, but communications technology should not be a substitute fortechnological advancement in a broader sense.‘Problems like the lack of clean water or lighting cannot be solved by ICT,’ saysEkekwe. ‘For all the mobile software apps for farmers, Africa still needs seeds foragriculture. Policymakers are wrong to focus almost exclusively on ICT and neglectlong-standing development needs.’By concentrating heavily on ICTs, Ekekwe believes that governments are givingpeople, and children in particular, a narrow view of technological possibilitiesand risk limiting the diversity of solutions needed for economic growth. ‘There isnothing wrong with teaching ICT. The problem is that no other emerging technology— alternative energy, biotechnology, or nanotechnology — has received the sameattention. ICT,’ adds Ekekwe, ‘is not synonymous with technology.’➜ Read the full article on SciDev.Net: http://goo.gl/jP6eZImagesource / HHWhile agricultural communities havea crucial economic and cultural role indeveloping countries, they are the mostvulnerable to the effects of a changingclimate. However, a new paper from theCentre for Development Informatics atthe University of Manchester, in the UK,argues that ICTs help farmers respond tounpredictable weather patterns throughmitigation, monitoring, adaptation andimproved access to information.The strategy brief, entitled ICT-Enabled Responses to Climate Change inRural Agricultural Communities, notesthat farmers are adopting ‘climatesmart’agricultural practices, includingintegrated soil nutrient management,crop diversity and organic agriculture.‘Emerging experiences in rural agriculturalcommunities suggest that the use of ICTssuch as mobile phones, radio, TV and videocan facilitate the dissemination of climatechange messages among vulnerablepopulations,’ say authors, Angelica V.Ospina and Richard Heeks.➜ Read the full report: http://goo.gl/XQyMONeil Palmer / CIAT / flickrSearching in privateSearch engines remain popular—andusers are more satisfied than ever withthe quality of search results—but manypeople are anxious about the collectionof personal information by search enginesand other websites, and say they do notlike the idea of personalised search resultsor targeted advertising.These findings come from a February2012 Pew Internet Project survey, whichfinds that 91% of adults online use searchengines to find information on the web.‘Search engines are increasinglyimportant to people in their navigationof information spaces, but users aregenerally uncomfortable with the ideaof their search histories being used totarget information to them,’ said KristenPurcell, Pew Internet associate directorfor research and author of the report. ‘Aclear majority of searchers say that theyfeel that search engines keeping track ofsearch history is an invasion of privacy,and they also worry about their searchresults being limited to what’s deemedrelevant to them.’These findings arise as policy debatesabout privacy, collection of personalinformation online and targetedadvertising are heating up. In particular,Google’s new privacy policy allows forthe collection of information about anindividual’s online behaviour on anyof Google’s sites (including its searchengine, Google+ social networking site,YouTube video-sharing site, and Gmail)into a combined and cohesive user profile,alerting marketers to which products mayappeal to specific individuals.➜ Read the full report: http://goo.gl/iplqc14 June 2012 ı ICT Update ı issue 66

John Schinker / flickrThe benefits of broadbandBroadband can help transitionthe world towards a lowcarboneconomy and addressthe causes and effects ofclimate change, according toa new report just released bythe Broadband Commissionfor Digital Development.The report, The BroadbandBridge: Linking ICT withClimate Action, aims toraise awareness of thepivotal role ICTs, and particularly broadband networks, can playin helping creating a low-carbon economy. The report providespractical examples of how broadband can contribute to reducinggreenhouse gasses, mitigating and adapting to the effects ofclimate change, and promoting resource efficiency.The findings are based on interviews, case studies and supportingmaterial from more than 20 leaders and experts in the field.‘Broadband’s role in GDP growth, in enabling the MillenniumDevelopment Goals, and offsetting the effects of climate changeis just now starting to be understood, because finally thedeployment is there and the benefits can be realised,’ said HansVestberg, chair of the Broadband Commission.Expansions in investmentsThe Kenyan governmenthas secured US$55.1million to expand the useof ICTs in the country forcontent development,improved transparency andaccountability, and increasedeconomic growth.Kenya has the secondfastestbroadbandconnection on thecontinent (after Ghana),and has increased internet penetration from 3% to 37% ofthe population in the past decade. Meanwhile, around 90% ofKenyan adults have, or have the use of, a cell phone.‘The additional finance will enable Kenya to consolidate theinitiatives it has made in the ICT sector, including the open datainitiative,’ says Johannes Zutt, World Bank Country Director forKenya. ‘Information technology has on average contributed onepercentage point to Kenya’s growth since 2000, and opened a pathfor achieving remarkable improvements in transparency and also ingovernance.’ The government and the Bank will explore a public–private partnership business model for e-government applications.Developing connectivityDespite efforts over the past decade to develop ICTinfrastructure in developing economies, a new digital divide interms of ICT impacts persists, according to the latest rankingsof The Global Information Technology Report 2012 releasedrecently by the World Economic Forum.ICT readiness in sub-Saharan Africa remains low. Mostcountries show significant lags in connectivity due toinsufficient development of ICT infrastructure, which remainstoo costly, and display poor skill levels that do not allowfor an efficient use of the available technology. Even inthose countries where ICT infrastructure has been improved,ICT-driven impacts on competitiveness and well-being trailbehind, resulting in a new digital divide.With the subtitle, Living in a Hyperconnected World, thereport explores the causes and consequences of living in anenvironment where the internet is accessible and immediate;people and businesses can communicate instantly; andmachines are interconnected. The exponential growth ofmobile devices, big data and social media is a driver of thisprocess of hyperconnectivity and, consequently, fundamentaltransformations in all areas of society are being witnessed.This year’s report tracks how societies leverage ICT to deriveimportant competitive advantages and increase social wellbeing.The Networked Readiness Index featured in the report usesa combination of data from publicly available sources andthe results of the Executive Opinion Survey, a comprehensiveannual survey conducted by the Forum in collaboration withpartner institutes, a network of over 150 leading researchinstitutes and business organisations.The report containsdetailed countryprofiles for the 142economies featured inthe study, providinga snapshot of eacheconomy’s level of ICTuptake and economicand social impacts.Also included is anextensive section ofdata tables for the 53indicators used in thecomputation of theindex.➜ Read the fullreport:http://goo.gl/5NCby52.2%, the drop in fixedbroadbandprices indeveloping countriesover the last two years. It is the steepestdrop globallyhttp://goo.gl/79OJc14,000 16km, thelength ofMain CableOne, the sub-marine communications cablestretching from Portugal to South Africahttp://goo.gl/9IX2Gmillion, the cost in US dollarsof a new undersea internetbroadband cable to Haiti,replacing the one destroyed in the 2010earthquakehttp://goo.gl/C7Slahttp://ictupdate.cta.int15

Tech TalkThe impact of ICTsICTs can improve yourefficiency, effectivenessand the way you work,but we have toremember that theycan have a huge impact- good and bad - onour lives.Trygve Bolstad / LineairICTsI was a computer scientist, but thanks tothe web I became interested in ruraldevelopment. As an IT engineer by training,I started exploring cyberspace, scanning forrelevant information around me. Becauseof the availability of information, andconsidering it in the context of Madagascar,where more than 70% of population live inpoverty in rural areas, my interest and myconsciousness grew.What’s amazing about the web is thatyou can jump from one world / area /domain to another with a mouse click. I amstill reflecting on the pros and cons of theweb, but I know it is beneficial for me in somany areas of my life, even though itconsumes so much time and brain-energy.The tools available to help you manage,explore, improve ways of doing things arecountless. ICTs in general can improvetremendously your efficiency, effectivenessand the way you work.However, we must not forget that ICTsand the web can have a huge impact -good and bad - on human lives andbehaviour.WebsitesI started thinking seriously about farmingsome years ago after I visited the ruralparts of Madagascar and heard through themedia about the poverty, food insecurity,hunger, famine and malnutrition. I decidedto start my own experimental farm. I spentsome time typing a few key words into asearch engine. I found one very interestingsite, Infonet-Biovision, which has anabundance of practical information.When I get tired of reading, I just addthe word ‘video’ to my search. Type ‘video’and composting’, for example, and you’llfind many videos on compostingtechniques from different areas of theworld, some more scientific than others.With so much many informationavailable, I organise it for quick retrieval inthe future, using the bookmarking tool,Diigo. It’s powerful and easy to use. I canhave different libraries there on agricultureand farming, on ICT and ICT4D. I also usethe Mozilla Firefox bookmarking function,which is very easy.To stay informed of new posts, I use theFirefox RSS feed reader and Google Reader.For instance, I follow news on the Scienceand Development Network (http://rss.scidev.net/en/) with the Firefox reader.➜ Infonet-Biovisionwww.infonet-biovision.org➜ Diigowww.diigo.com➜ SciDevNethttp://rss.scidev.net/enSocial networkingI use social networking tools in myprofessional and personal life. LinkedInhelps me stay in touch with manycolleagues worldwide. For instance, wehave a LinkedIn group for our African Teamworking on promoting web-basedmonitoring and evaluation (M&E) tool. I amalso member of more than 30 LinkedIngroups, including YPARD, Web2forDev,e-Agriculture, ICT4D, ICT Update, IAALD andM&E group discussions.For family, friends and our non-profitorganisation, I use Facebook, which is morewidely known. There, we have a Facebookgroup for Farming and Technology forAfrica initiatives➜ PLIK MS monitoring and evaluationwww.plikms.com➜ Farming and Technology for Africafacebook pagewww.facebook.com/pages/FTA-Initiative/117861414949292Andrianjafy Rasoanindrainy(andrew.raso@gmail.com) is manager atFarming and Technology for Africa(http://123fta.com)DevicesWherever I go to and important event - aseminar, conference, training course, ormeeting - I take my laptop, my cell phone,memory stick and digital camera. For longdistance trips (more than 5 hours), I use mytablet PC because of its good battery lifeand the easy functionality. In some cases, Ialso take my digital camcorder and myexternal hard drive to save large amountsof important data and files.I would have many problems if I didn’thave my laptop. It has become my secondmemory, my way of working and of beingproductive. And if I’m not connected, manyof my colleagues and collaborators won’tbe able to reach me at all.For very rational reasons and fromprevious bad experiences, I always makebackups of my key data in (at least) 2different places. My archiving system is mysecond laptop (a netbook), and my set ofexternal hard drives where I have almost allmy work since 1994.FutureI dream of a device (a kind of veryadvanced notebook) that can capture orregenerate energy by itself. No need for anexternal power supply. It would be able toconnect to the web wherever I am -permanent connectivity - with unlimitedmemory to store all the web contentdynamically, if required. This sophisticateddevice would be very light, even lighterthan a cell phones, and at a price thateveryone on Earth could afford. I know I’mpushing a little here, but I did say it was adream. ◀▶ ICT Update is published by <strong>CTA</strong> Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (ACP-EU). <strong>CTA</strong> is an institution of the ACP Group of States and the EU, in the framework of the Cotonou Agreement and isfinanced by the EU. Postbus 380, 6700 AJ Wageningen, the Netherlands (www.cta.int). Editorial management and production: Contactivity bv, Stationsweg 28, 2312 AV Leiden, the Netherlands (www.contactivity.com).16 June 2012 ı ICT Update ı issue 66